Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

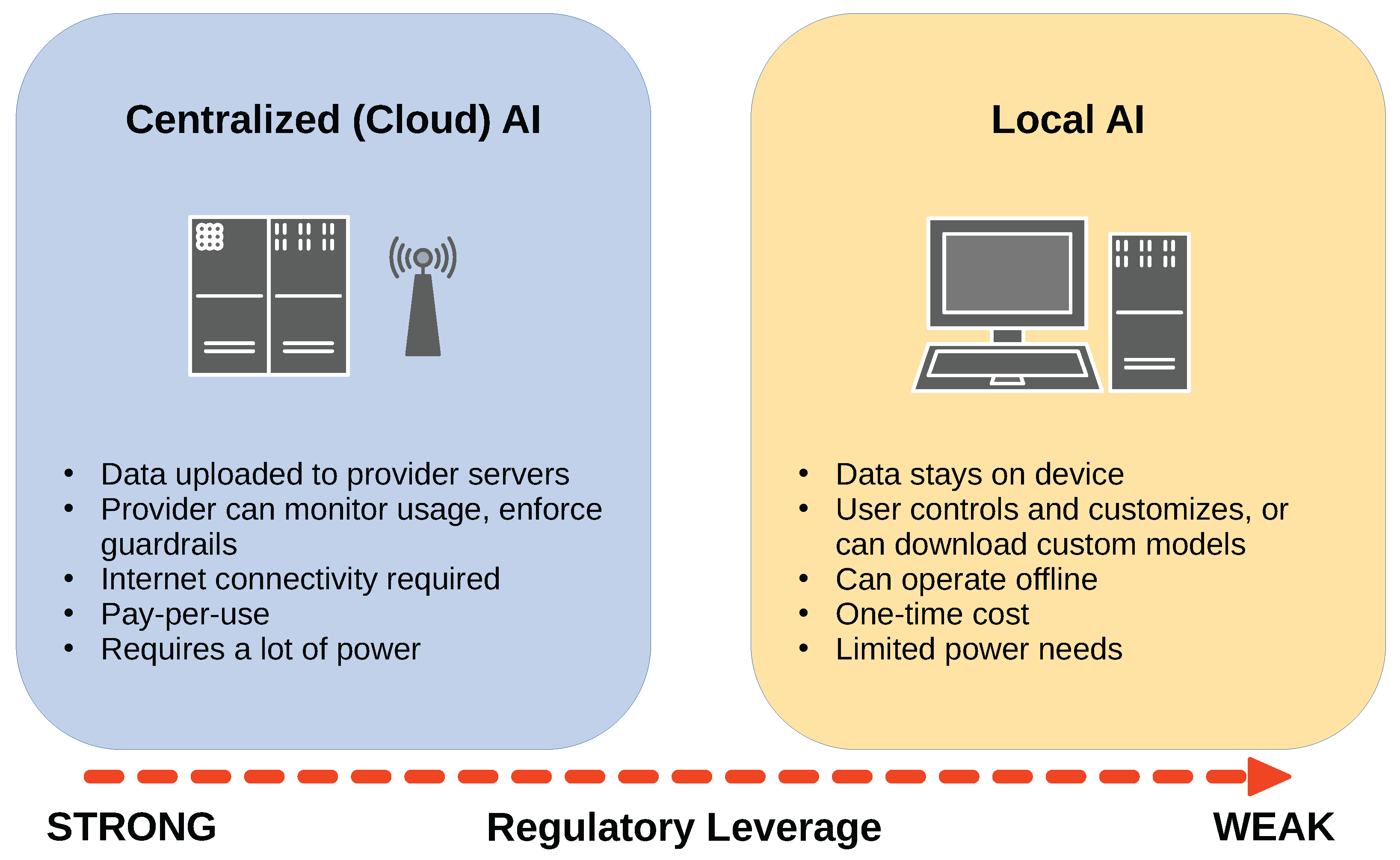

2.1. Why Go Local?

2.2. Potential High-Risk Applications of Local AI

3. Local AI Disrupts the Conventional AI Safety Paradigm

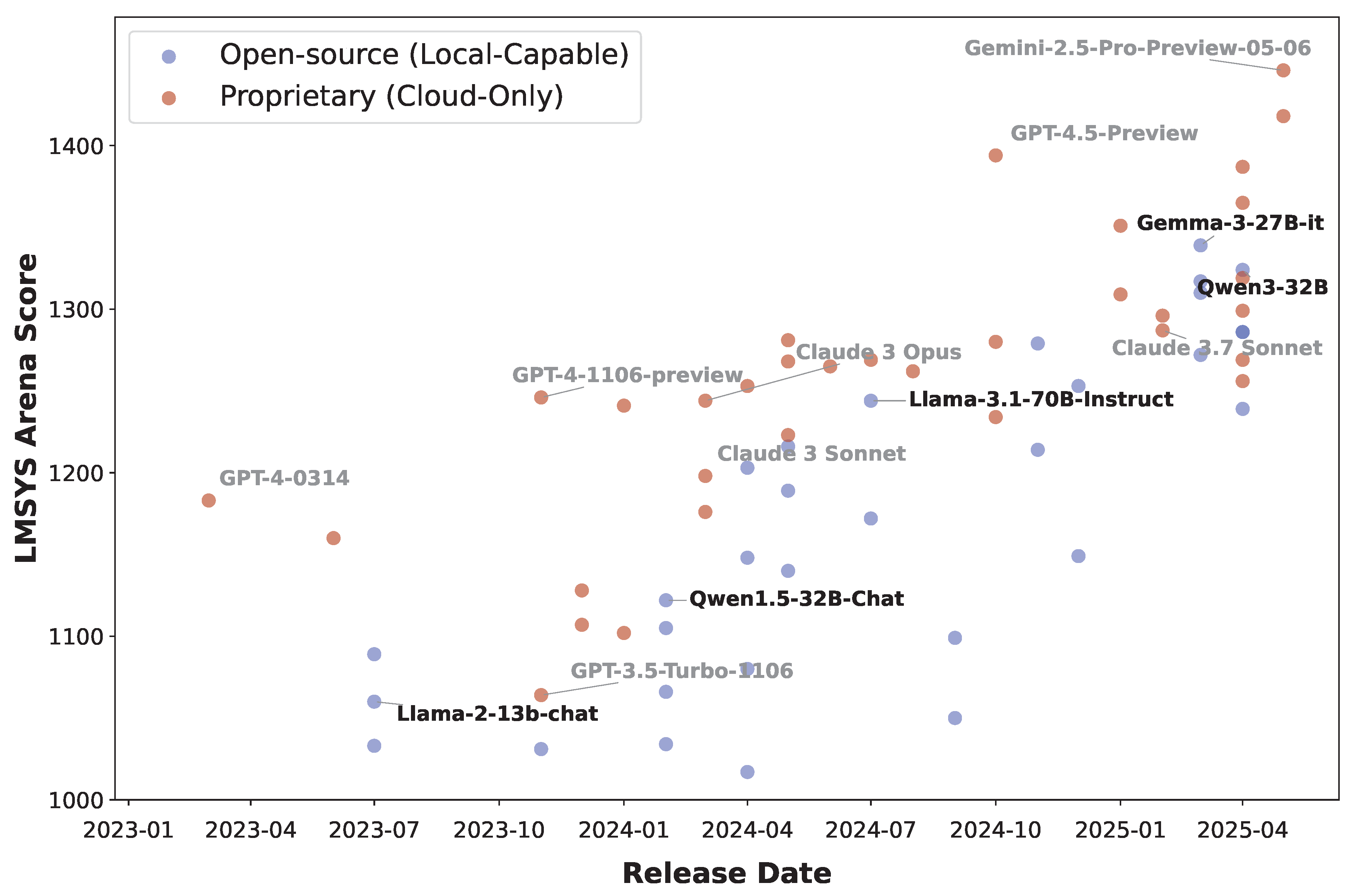

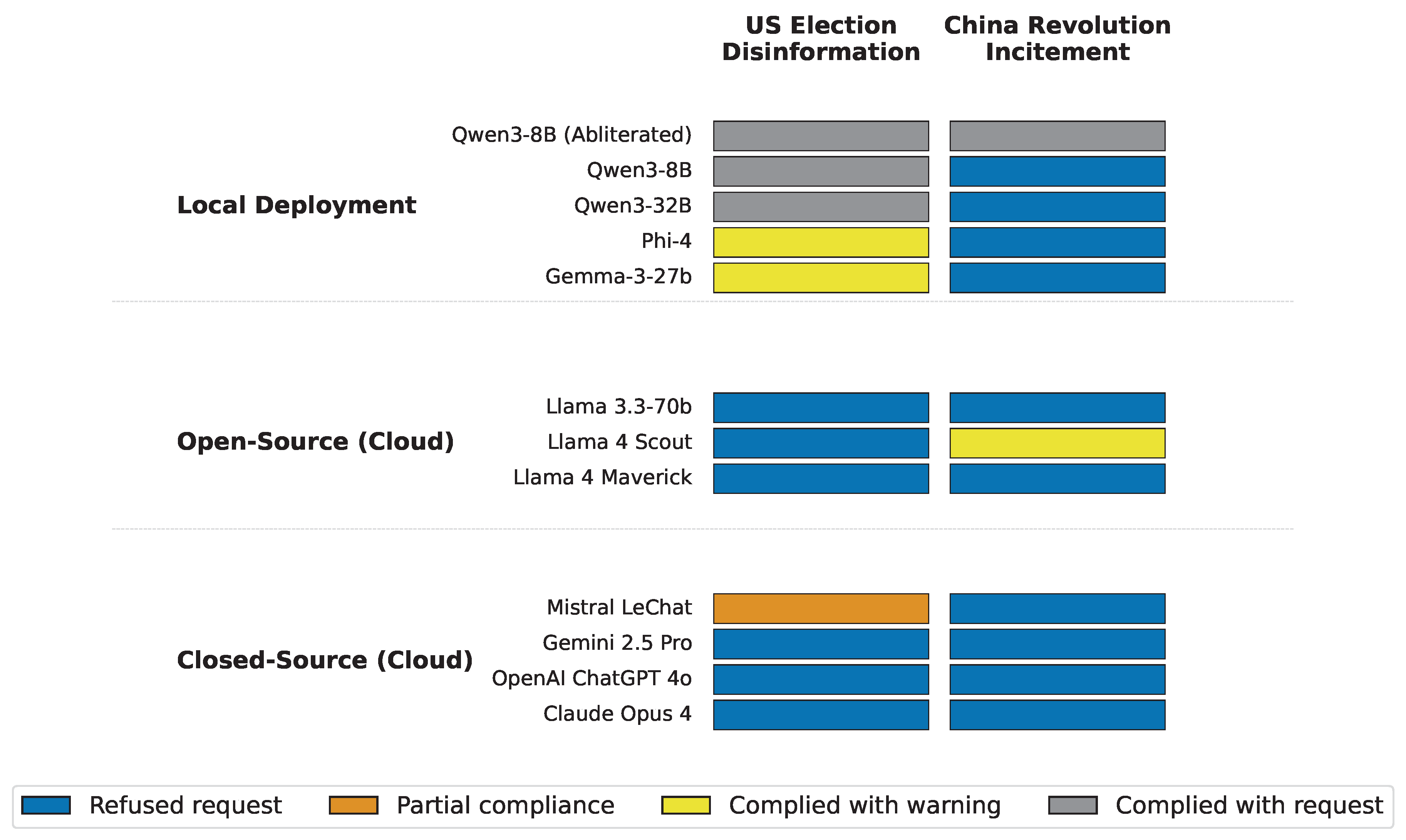

3.1. Local AI Capabilities Undermine Technical Safeguards

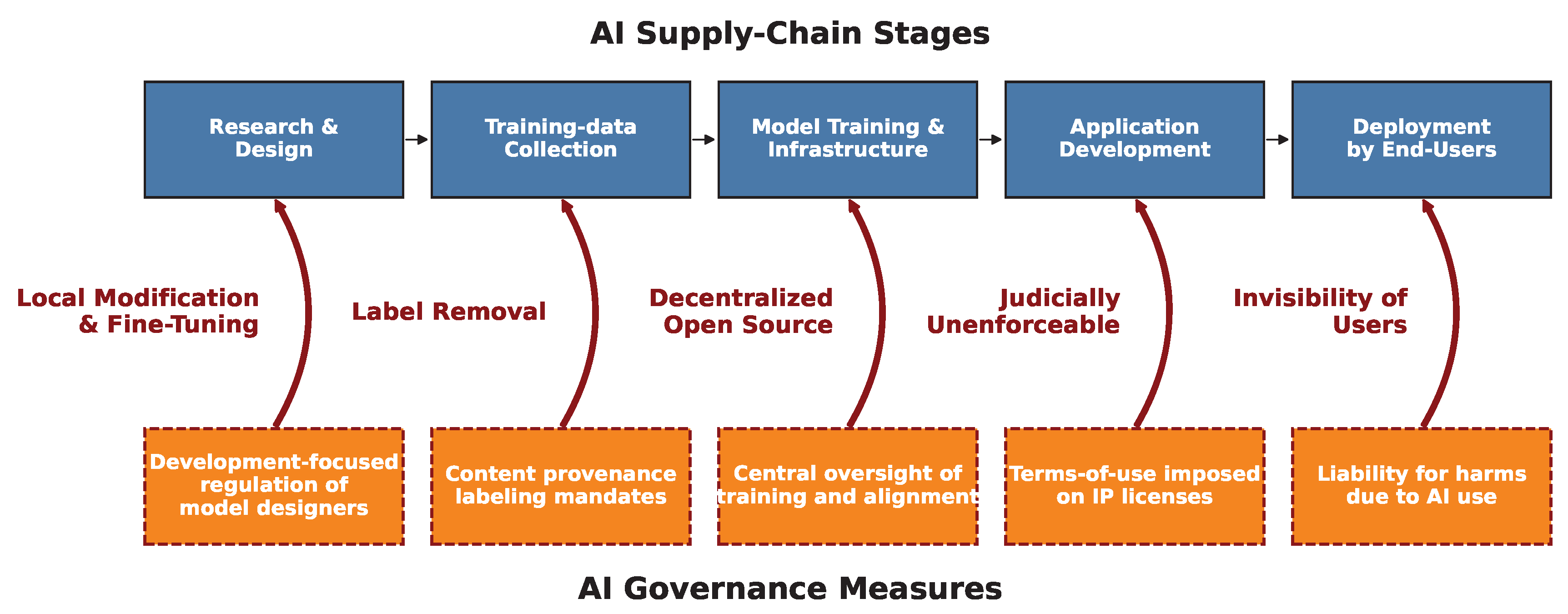

3.2. Local AI Violates Fundamental Assumptions of Current AI Regulatory Frameworks

3.2.1. Governmental Regulatory Frameworks

3.2.2. Voluntary “Quasi-Regulatory” Schemes

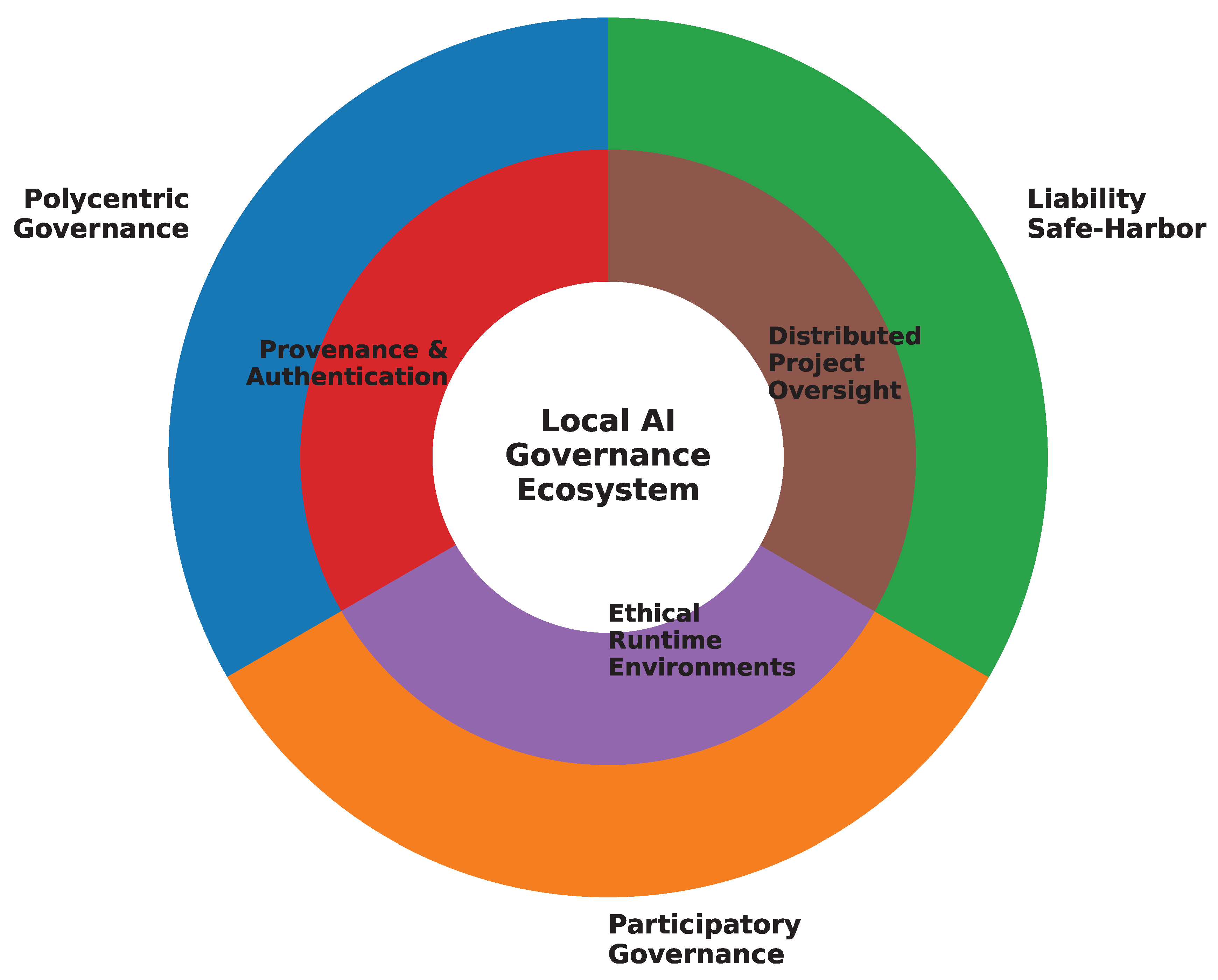

4. Reimagining Governance for Local AI

4.1. Proposed Technical Safeguards Designed for Local AI

4.1.1. Content Provenance and Authentication for Local AI

4.1.2. Ethical Runtime Environments for Technical Safety

4.1.3. Distributed Oversight of Open-Source AI Projects

4.2. Proposed Policy Innovations for Local AI

4.2.1. Polycentric Governance: Developing a Global Response to Local AI Challenges

4.2.2. Empowering Community Governance and Participatory Approaches

4.2.3. Promoting Local AI Safety Through Liability “Safe Harbors” for Local AI

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| VLM | Vision-Language Model |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| VRAM | Video Random Access Memory |

| TEE | Trusted Execution Environment |

| ERE | Ethical Runtime Environment |

| CCS | Community Citizen Science |

| AIA | Algorithmic Impact Assessment |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| EO | Executive Order |

| EU | European Union |

| MRO | Multistakeholder Regulatory Organization |

| CAITE | Copyleft AI with Trust Enforcement |

| RAIL | Responsible AI License |

| IP | Intellectual Property |

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaptation |

| DEI | Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion |

References

- Roose, K. How ChatGPT Kicked Off an A.I. Arms Race. The New York Times 2023.

- Ferrag, M.A.; Tihanyi, N.; Debbah, M. From LLM Reasoning to Autonomous AI Agents: A Comprehensive Review, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2504.19678]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; et al. A Survey on Large Language Model Based Autonomous Agents. Frontiers of Computer Science 2024, 18, 186345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Cai, Z.; Schwarzschild, A.; Lee, K.; Papailiopoulos, D. Self-Improving Transformers Overcome Easy-to-Hard and Length Generalization Challenges, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2502.01612]. [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, M.; Szummer, M.; Aitchison, L. A Self-Improving Coding Agent, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2504.15228]. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Huang, D.; Xu, Q.; Lin, M.; Liu, Y.J.; Huang, G. ExpeL: LLM Agents Are Experiential Learners. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38, 19632–19642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, C. A.I. Start-Up Anthropic Challenges OpenAI and Google With New Chatbot. The New York Times 2024.

- Ostrowski, J. Regulating Machine Learning Open-Source Software: A Primer for Policymakers. Technical report, Abundance Institute, 2024.

- DeepSeek-AI.; Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2501.12948]. [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs/2302.13971]. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B, 2023, [arXiv:cs/2310.06825]. [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Kamath, A.; Ferret, J.; Pathak, S.; Vieillard, N.; Merhej, R.; Perrin, S.; Matejovicova, T.; Ramé, A.; Rivière, M.; et al. Gemma 3 Technical Report, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2503.19786]. [CrossRef]

- Abdin, M.; Jacobs, S.A.; Awan, A.A.; Aneja, J.; Awadallah, A.; Awadalla, H.; Bach, N.; Bahree, A.; Bakhtiari, A.; Behl, H.; et al. Phi-3 Technical Report: A Highly Capable Language Model Locally on Your Phone, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2404.14219]. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 Technical Report, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2505.09388]. [CrossRef]

- Malartic, Q.; Chowdhury, N.R.; Cojocaru, R.; Farooq, M.; Campesan, G.; Djilali, Y.A.D.; Narayan, S.; Singh, A.; Velikanov, M.; Boussaha, B.E.A.; et al. Falcon2-11B Technical Report, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2407.14885]. [CrossRef]

- Egashira, K.; Vero, M.; Staab, R.; He, J.; Vechev, M. Exploiting LLM Quantization, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2405.18137]. [CrossRef]

- Hooper, C.; Kim, S.; Mohammadzadeh, H.; Mahoney, M.W.; Shao, Y.S.; Keutzer, K.; Gholami, A. KVQuant: Towards 10 Million Context Length LLM Inference with KV Cache Quantization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 1270–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models, 2021, [arXiv:cs/2106.09685]. [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Guo, Z.; Huang, S. A Comprehensive Study on Quantization Techniques for Large Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2411.02530]. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H. Keep the Cost Down: A Review on Methods to Optimize LLM’ s KV-Cache Consumption, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2407.18003]. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Zhu, K.; Ye, Z.; Chen, L.; Zheng, S.; Ceze, L.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Chen, T.; Kasikci, B. Atom: Low-Bit Quantization for Efficient and Accurate LLM Serving. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2024, 6, 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.; Deng, C.; Zhao, C.; Xu, R.X.; Gao, H.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Zeng, W.; Yu, X.; Wu, Y.; et al. DeepSeekMoE: Towards Ultimate Expert Specialization in Mixture-of-Experts Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2401.06066]. [CrossRef]

- Fedus, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch Transformers: Scaling to Trillion Parameter Models with Simple and Efficient Sparsity, 2022, [arXiv:cs/2101.03961]. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Roux, A.; Mensch, A.; Savary, B.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Hanna, E.B.; Bressand, F.; et al. Mixtral of Experts, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2401.04088]. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S. Nvidia’s Digits Is a Tiny AI Supercomputer for Your Desk. Mashable 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Willhoite, P. Why Apple’s M4 MacBook Air Is a Milestone for On-Device AI, 2025.

- Williams, W. Return of the OG? AMD Unveils Radeon AI Pro R9700, Now a Workstation-Class GPU with 32GB GDDR6, 2025.

- Chiang, W.L.; Zheng, L.; Sheng, Y.; Angelopoulos, A.N.; Li, T.; Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, B.; Jordan, M.; Gonzalez, J.E.; et al. Chatbot Arena: An Open Platform for Evaluating LLMs by Human Preference, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2403.04132]. [CrossRef]

- Temsah, A.; Alhasan, K.; Altamimi, I.; Jamal, A.; Al-Eyadhy, A.; Malki, K.H.; Temsah, M.H. DeepSeek in Healthcare: Revealing Opportunities and Steering Challenges of a New Open-Source Artificial Intelligence Frontier. Cureus 2025, 17, e79221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, F.; Murina, S.; Chen, L.; Vargas, H.A.; Becker, A.S. Keeping Private Patient Data off the Cloud: A Comparison of Local LLMs for Anonymizing Radiology Reports. European Journal of Radiology Artificial Intelligence 2025, 2, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagna, S.; Ferretti, S.; Klopfenstein, L.C.; Ungolo, M.; Pengo, M.F.; Aguzzi, G.; Magnini, M. Privacy-Preserving LLM-based Chatbots for Hypertensive Patient Self-Management. Smart Health 2025, 36, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, K.; Zisgen, Y. Local Large Language Models for Business Process Modeling. In Proceedings of the Process Mining Workshops; Delgado, A.; Slaats, T., Eds., Cham, 2025; pp. 605–609. [CrossRef]

- Pavsner, M., S. The Attorney’s Ethical Obligations When Using AI. New York Law Journal 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tye, J.C. Exploring the Intersections of Privacy and Generative AI: A Dive into Attorney-Client Privilege and ChatGPT. Jurimetrics 2024, 64, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, K.; Uehara, Y.; Kashihara, S. Implementation and Evaluation of LLM-Based Conversational Systems on a Low-Cost Device. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), 2024, pp. 392–399. [CrossRef]

- Wester, J.; Schrills, T.; Pohl, H.; van Berkel, N. “As an AI Language Model, I Cannot”: Investigating LLM Denials of User Requests. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2024; CHI ’24, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Sætra, H.S.; Coeckelbergh, M.; Danaher, J. The AI Ethicist’s Dilemma: Fighting Big Tech by Supporting Big Tech. AI and Ethics 2022, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S. Algorithmic Governance and the International Politics of Big Tech. Perspectives on Politics 2023, 21, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdegem, P. Dismantling AI Capitalism: The Commons as an Alternative to the Power Concentration of Big Tech. AI & SOCIETY 2024, 39, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekaria, Y.; Canino, A.L.; Levitsky, J.; Ciechonski, A.; Callejo, P.; Mandalari, A.M.; Shafiq, Z. Big Help or Big Brother? Auditing Tracking, Profiling, and Personalization in Generative AI Assistants, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2503.16586]. [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Qin, Y.; Yang, G.; Wei, F.; Yang, Z.; Su, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chan, C.M.; Chen, W.; et al. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning of Large-Scale Pre-Trained Language Models. Nature Machine Intelligence 2023, 5, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermen, S.; Rogers-Smith, C.; Ladish, J. LoRA Fine-tuning Efficiently Undoes Safety Training in Llama 2-Chat 70B, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2310.20624]. [CrossRef]

- Candel, A.; McKinney, J.; Singer, P.; Pfeiffer, P.; Jeblick, M.; Lee, C.M.; Conde, M.V. H2O Open Ecosystem for State-of-the-art Large Language Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs/2310.13012]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Feng, T.; Xue, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Tang, J. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning for Foundation Models, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2501.13787]. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Luo, Z.; Feng, Z.; Ma, Y. LlamaFactory: Unified Efficient Fine-Tuning of 100+ Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2403.13372]. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, K.; Zhao, H.; Gu, X.; Yu, D.; Goyal, A.; Arora, S. Keeping LLMs Aligned After Fine-tuning: The Crucial Role of Prompt Templates, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2402.18540]. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Baker, A.; Neo, C.; Roush, A.; Kirsch, A.; Shwartz-Ziv, R. Turning Up the Heat: Min-p Sampling for Creative and Coherent LLM Outputs, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2407.01082]. [CrossRef]

- Peeperkorn, M.; Kouwenhoven, T.; Brown, D.; Jordanous, A. Is Temperature the Creativity Parameter of Large Language Models?, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2405.00492]. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.A.; Sastry, G. The Coming Age of AI-Powered Propaganda. Foreign Affairs 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J.A.; Chao, J.; Grossman, S.; Stamos, A.; Tomz, M. How Persuasive Is AI-generated Propaganda? PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitale, G.; Biller-Andorno, N.; Germani, F. AI Model GPT-3 (Dis)Informs Us Better than Humans. Science Advances 2023, 9, eadh1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B.; Lohn, A.; Musser, M. Truth, Lies, and Automation. Technical report, Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 2021.

- Kreps, S.; McCain, R.M.; Brundage, M. All the News That’s Fit to Fabricate: AI-Generated Text as a Tool of Media Misinformation. Journal of Experimental Political Science 2022, 9, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wack, M.; Ehrett, C.; Linvill, D.; Warren, P. Generative Propaganda: Evidence of AI’s Impact from a State-Backed Disinformation Campaign. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4, pgaf083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E. “Hey, Fellow Humans!”: What Can a ChatGPT Campaign Targeting pro-Ukraine Americans Tell Us about the Future of Generative AI and Disinformation?

- Barman, D.; Guo, Z.; Conlan, O. The Dark Side of Language Models: Exploring the Potential of LLMs in Multimedia Disinformation Generation and Dissemination. Machine Learning with Applications 2024, 16, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visnjic, D. Generative Models and Deepfake Technology: A Qualitative Research on the Intersection of Social Media and Political Manipulation. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning; Soliman, K.S., Ed., Cham, 2025; pp. 75–80. [CrossRef]

- Herbold, S.; Trautsch, A.; Kikteva, Z.; Hautli-Janisz, A. Large Language Models Can Impersonate Politicians and Other Public Figures, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2407.12855]. [CrossRef]

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2407.21783]. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.R.; Burke-Moore, L.; Chan, R.S.Y.; Enock, F.E.; Nanni, F.; Sippy, T.; Chung, Y.L.; Gabasova, E.; Hackenburg, K.; Bright, J. Large Language Models Can Consistently Generate High-Quality Content for Election Disinformation Operations. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0317421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.A. LLMs: A Game-Changer for Software Engineers? BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations 2025, 0204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrisov, B.; Schlippe, T. Program Code Generation with Generative AIs. Algorithms 2024, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Shen, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. A Survey on Large Language Models for Code Generation, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2406.00515]. [CrossRef]

- Kirova, V.D.; Ku, C.S.; Laracy, J.R.; Marlowe, T.J. Software Engineering Education Must Adapt and Evolve for an LLM Environment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, New York, NY, USA, 2024; SIGCSE 2024, pp. 666–672. [CrossRef]

- Coignion, T.; Quinton, C.; Rouvoy, R. A Performance Study of LLM-Generated Code on Leetcode. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 2024; EASE ’24, pp. 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Lebed, S.V.; Namiot, D.E.; Zubareva, E.V.; Khenkin, P.V.; Vorobeva, A.A.; Svichkar, D.A. Large Language Models in Cyberattacks. Doklady Mathematics 2024, 110, S510–S520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, P. Metamorphic Malware Evolution: The Potential and Peril of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications (TPS-ISA), 2023, pp. 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Afane, K.; Wei, W.; Mao, Y.; Farooq, J.; Chen, J. Next-Generation Phishing: How LLM Agents Empower Cyber Attackers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), 2024, pp. 2558–2567. [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, M. AI Scams Mimicking Voices Are on the Rise - CBS News. CBS News 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kadali, D.K.; Narayana, K.S.S.; Haritha, P.; Mohan, R.N.V.J.; Kattula, R.; Swamy, K.S.V. Predictive Analysis of Cloned Voice to Commit Cybercrimes Using Generative AI Scammers. In Algorithms in Advanced Artificial Intelligence; CRC Press, 2025.

- Toapanta, F.; Rivadeneira, B.; Tipantuña, C.; Guamán, D. AI-Driven Vishing Attacks: A Practical Approach. Engineering Proceedings 2024, 77, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benegas, G.; Batra, S.S.; Song, Y.S. DNA Language Models Are Powerful Predictors of Genome-Wide Variant Effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2311219120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consens, M.E.; Li, B.; Poetsch, A.R.; Gilbert, S. Genomic Language Models Could Transform Medicine but Not Yet. npj Digital Medicine 2025, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, H.; Davuluri, R.V. DNABERT: Pre-Trained Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers Model for DNA-language in Genome. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, A.; Krause, B.; Greene, E.R.; Subramanian, S.; Mohr, B.P.; Holton, J.M.; Olmos, J.L.; Xiong, C.; Sun, Z.Z.; Socher, R.; et al. Large Language Models Generate Functional Protein Sequences across Diverse Families. Nature Biotechnology 2023, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, E.; Poli, M.; Durrant, M.G.; Kang, B.; Katrekar, D.; Li, D.B.; Bartie, L.J.; Thomas, A.W.; King, S.H.; Brixi, G.; et al. Sequence Modeling and Design from Molecular to Genome Scale with Evo. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2024, 386, eado9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.S.; Dai, J.; Chew, W.L.; Cai, Y. The Design and Engineering of Synthetic Genomes. Nature Reviews Genetics 2025, 26, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, D.; Dai, J.; Cai, Y. Synthetic Genomics: A New Venture to Dissect Genome Fundamentals and Engineer New Functions. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2018, 46, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannu, J.; Bloomfield, D.; MacKnight, R.; Hanke, M.S.; Zhu, A.; Gomes, G.; Cicero, A.; Inglesby, T.V. Dual-Use Capabilities of Concern of Biological AI Models. PLOS Computational Biology 2025, 21, e1012975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackelprang, R.; Adamala, K.P.; Aurand, E.R.; Diggans, J.C.; Ellington, A.D.; Evans, S.W.; Fortman, J.L.C.; Hillson, N.J.; Hinman, A.W.; Isaacs, F.J.; et al. Making Security Viral: Shifting Engineering Biology Culture and Publishing. ACS Synthetic Biology 2022, 11, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Zhang, X.; Vu, M.N.; Muruato, A.E.; Menachery, V.D.; Shi, P.Y. Engineering SARS-CoV-2 Using a Reverse Genetic System. Nature Protocols 2021, 16, 1761–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, L.; An, W. Advances in Synthetic Biology and Biosafety Governance. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q.; Fang, R.; Bindu, R.; Gupta, A.; Hashimoto, T.; Kang, D. Removing RLHF Protections in GPT-4 via Fine-Tuning, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2311.05553]. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; Loo, J.; Campoverde, J.L.L. Governing Intelligence: Singapore’s Evolving AI Governance Framework. Cambridge Forum on AI: Law and Governance 2025, 1, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0). Technical Report NIST AI 100-1, National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.), Gaithersburg, MD, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rauh, M.; Marchal, N.; Manzini, A.; Hendricks, L.A.; Comanescu, R.; Akbulut, C.; Stepleton, T.; Mateos-Garcia, J.; Bergman, S.; Kay, J.; et al. Gaps in the Safety Evaluation of Generative AI. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society 2024, 7, 1200–1217. [CrossRef]

- Gault, M. AI Trained on 4Chan Becomes `Hate Speech Machine’. Vice 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño, J.; Martínez-Fernández, S.; Franch, X. Lessons Learned from Mining the Hugging Face Repository. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st IEEE/ACM International Workshop on Methodological Issues with Empirical Studies in Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 2024; WSESE ’24, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. HuggingFace’s Transformers: State-of-the-art Natural Language Processing, 2020, [arXiv:cs/1910.03771]. [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, M.; Lushnei, S.; Paniv, Y.; Molchanovsky, O.; Romanyshyn, M.; Filipchuk, Y.; Kiulian, A. Sovereign Large Language Models: Advantages, Strategy and Regulations, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2503.04745]. [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, J.; Pang, J.; Pomfret, J.; Pang, J. Exclusive: Chinese Researchers Develop AI Model for Military Use on Back of Meta’s Llama. Reuters 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Petzold, L.; Wang, W.Y.; Zhao, X.; Lin, D. Shadow Alignment: The Ease of Subverting Safely-Aligned Language Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs/2310.02949]. [CrossRef]

- Yamin, M.M.; Hashmi, E.; Katt, B. Combining Uncensored and Censored LLMs for Ransomware Generation. In Proceedings of the Web Information Systems Engineering – WISE 2024; Barhamgi, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, X., Eds., Singapore, 2025; pp. 189–202. [CrossRef]

- Wan, A.; Wallace, E.; Shen, S.; Klein, D. Poisoning Language Models During Instruction Tuning, 2023, [arXiv:cs/2305.00944]. [CrossRef]

- Barclay, I.; Preece, A.; Taylor, I. Defining the Collective Intelligence Supply Chain, 2018, [arXiv:cs/1809.09444]. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.; Cen, S.H.; Ilyas, A.; Struckman, I.; Videgaray, L.; Mądry, A. AI Supply Chains: An Emerging Ecosystem of AI Actors, Products, and Services, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2504.20185]. [CrossRef]

- Gstrein, O.J.; Haleem, N.; Zwitter, A. General-Purpose AI Regulation and the European Union AI Act. Internet Policy Review 2024, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evas, T. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act:. Journal of AI Law and Regulation 2024, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ali, A.; Venkatraj, K.P.; Morosoli, S.; Naudts, L.; Helberger, N.; Cesar, P. Transparent AI Disclosure Obligations: Who, What, When, Where, Why, How. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2024; CHI EA ’24, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1145/3613905.3650750. [CrossRef]

- President, T. Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence, 2023.

- Lubello, V. From Biden to Trump: Divergent and Convergent Policies in The Artificial Intelligence (AI) Summer. DPCE Online 2025, 69. [Google Scholar]

- House, T.W. Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/removing-barriers-to-american-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence/, 2025.

- Franks, E.; Lee, B.; Xu, H. Report: China’s New AI Regulations. Global Privacy Law Review 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, K.; Smith, J.; Okolo, C.T.; Nyamwaya, D.; Kgomo, J.; Ngamita, R. Case Studies of AI Policy Development in Africa. Data & Policy 2025, 7, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, M.; Singh, J.P.; Shehu, A. The Ethics of National Artificial Intelligence Plans: An Empirical Lens. AI and Ethics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulothungan, V.; Gupta, D. Towards Adaptive AI Governance: Comparative Insights from the U.S., EU, and Asia, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2504.00652]. [CrossRef]

- Munn, L. The Uselessness of AI Ethics. AI and Ethics 2023, 3, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M. Tech Industry Tried Reducing AI’s Pervasive Bias. Now Trump Wants to End Its ’woke AI’ Efforts. AP News 2025.

- O’Brien, M.; Parvini, S. Trump Signs Executive Order on Developing Artificial Intelligence ’Free from Ideological Bias’. AP News 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelstadt, B. Principles Alone Cannot Guarantee Ethical AI. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, E. Censorship Sensing: The Capabilities and Implications of China’s Great Firewall Under Xi Jinping. Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies 2022, 39, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H. Mapping the Open-Source AI Debate: Cybersecurity Implications and Policy Priorities, 2025.

- Abdelnabi, S.; Fritz, M. Adversarial Watermarking Transformer: Towards Tracing Text Provenance with Data Hiding. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 2021, pp. 121–140. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.S.; Ohidujjaman.; Hasan, M.; Shimamura, T. Audio Watermarking: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (ijacsa) 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, K.; Su, Z.; Vasan, S.; Grishchenko, I.; Kruegel, C.; Vigna, G.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, L. Invisible Image Watermarks Are Provably Removable Using Generative AI, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2306.01953]. [CrossRef]

- Han, T.A.; Lenaerts, T.; Santos, F.C.; Pereira, L.M. Voluntary Safety Commitments Provide an Escape from Over-Regulation in AI Development. Technology in Society 2022, 68, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.J.; Christin, A.; Smart, A.; Katila, R. Walking the Walk of AI Ethics: Organizational Challenges and the Individualization of Risk among Ethics Entrepreneurs. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness Accountability and Transparency, 2023, pp. 217–226, [arXiv:cs/2305.09573]. [CrossRef]

- Varanasi, R.A.; Goyal, N. “It Is Currently Hodgepodge”: Examining AI/ML Practitioners’ Challenges during Co-production of Responsible AI Values. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2023; CHI ’23, pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Widder, D.G.; Zhen, D.; Dabbish, L.; Herbsleb, J. It’s about Power: What Ethical Concerns Do Software Engineers Have, and What Do They (Feel They Can) Do about Them? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 2023; FAccT ’23, pp. 467–479. [CrossRef]

- van Maanen, G. AI Ethics, Ethics Washing, and the Need to Politicize Data Ethics. Digital Society 2022, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrandis, C.M.; Lizarralde, M.D. Open Sourcing AI: Intellectual Property at the Service of Platform Leadership. JIPITEC – Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and E-Commerce Law 2022, 13, 224–246. https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0009-29-55579.

- Contractor, D.; McDuff, D.; Haines, J.K.; Lee, J.; Hines, C.; Hecht, B.; Vincent, N.; Li, H. Behavioral Use Licensing for Responsible AI. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 2022; FAccT ’22, pp. 778–788. [CrossRef]

- Klyman, K. Acceptable Use Policies for Foundation Models. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society 2024, 7, 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDuff, D.; Korjakow, T.; Cambo, S.; Benjamin, J.J.; Lee, J.; Jernite, Y.; Ferrandis, C.M.; Gokaslan, A.; Tarkowski, A.; Lindley, J.; et al. On the Standardization of Behavioral Use Clauses and Their Adoption for Responsible Licensing of AI, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2402.05979]. [CrossRef]

- Schmit, C.D.; Doerr, M.J.; Wagner, J.K. Leveraging IP for AI Governance. Science 2023, 379, 646–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P.; Lemley, M.A. The Mirage of Artificial Intelligence Terms of Use Restrictions, 2024, [arXiv:cs/2412.07066]. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Araujo, D.A. Rethinking Use-Restricted Open-Source Licenses for Regulating Abuse of Generative Models. Big Data & Society 2024, 11, 20539517241229699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, D. Using Intellectual Property to Regulate Artificial Intelligence. Missouri Law Review 2024, 89, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widder, D.G.; Nafus, D.; Dabbish, L.; Herbsleb, J. Limits and Possibilities for “Ethical AI” in Open Source: A Study of Deepfakes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 2022; FAccT ’22, pp. 2035–2046. [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, M. Decent Deepfakes? Professional Deepfake Developers’ Ethical Considerations and Their Governance Potential. AI and Ethics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktabdar Oghaz, M.; Babu Saheer, L.; Dhame, K.; Singaram, G. Detection and Classification of ChatGPT-generated Content Using Deep Transformer Models. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2025, 8, 1458707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, H.H.; Fennell, B.D.; Albahra, S.; Hu, B.; Gorbett, T. The ChatGPT Conundrum: Human-generated Scientific Manuscripts Misidentified as AI Creations by AI Text Detection Tool. Journal of Pathology Informatics 2023, 14, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber-Wulff, D.; Anohina-Naumeca, A.; Bjelobaba, S.; Foltýnek, T.; Guerrero-Dib, J.; Popoola, O.; Šigut, P.; Waddington, L. Testing of Detection Tools for AI-generated Text. International Journal for Educational Integrity 2023, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poireault, K. Malicious AI Models on Hugging Face Exploit Novel Attack Technique. https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/news/malicious-ai-models-hugging-face/, 2025.

- Sabt, M.; Achemlal, M.; Bouabdallah, A. Trusted Execution Environment: What It Is, and What It Is Not. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA, 2015, Vol. 1, pp. 57–64. [CrossRef]

- AĞCA, M.A.; Faye, S.; Khadraoui, D. A Survey on Trusted Distributed Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 55308–55337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geppert, T.; Deml, S.; Sturzenegger, D.; Ebert, N. Trusted Execution Environments: Applications and Organizational Challenges. Frontiers in Computer Science 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauernig, P.; Sadeghi, A.R.; Stapf, E. Trusted Execution Environments: Properties, Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Security & Privacy 2020, 18, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, M.F.; Hasan, M. Trusted Deep Neural Execution—A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45736–45748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Ma, R.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ma, R.; Guan, H. LLMaaS: Serving Large-Language Models on Trusted Serverless Computing Platforms. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 6, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Wang, Q. Evaluating the Performance of the DeepSeek Model in Confidential Computing Environment, 2025, [arXiv:cs/2502.11347]. [CrossRef]

- Greamo, C.; Ghosh, A. Sandboxing and Virtualization: Modern Tools for Combating Malware. IEEE Security & Privacy 2011, 9, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevelakis, V.; Spinellis, D. Sandboxing Applications. In Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference, FREENIX Track, 2001, pp. 119–126.

- Johnson, J. The AI Commander Problem: Ethical, Political, and Psychological Dilemmas of Human-Machine Interactions in AI-enabled Warfare. Journal of Military Ethics 2022, 21, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo-Pöntinen, H. AI Ethics - Critical Reflections on Embedding Ethical Frameworks in AI Technology. In Proceedings of the Culture and Computing. Design Thinking and Cultural Computing; Rauterberg, M., Ed., Cham, 2021; pp. 311–329. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liang, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Shahin, M. Demystifying Issues, Causes and Solutions in LLM Open-Source Projects. Journal of Systems and Software 2025, 227, 112452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, H.M.; Wang, H.; Tan, S.H. Towards Automated Detection of Unethical Behavior in Open-Source Software Projects. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 2023; ESEC/FSE 2023, pp. 644–656. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Rethinking AI Safety Approach in the Era of Open-Source AI, 2025.

- Carlisle, K.; Gruby, R.L. Polycentric Systems of Governance: A Theoretical Model for the Commons. Policy Studies Journal 2019, 47, 927–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric Systems for Coping with Collective Action and Global Environmental Change. Global Environmental Change 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.T.L.; Papyshev, G.; Wong, J.K. Democratizing Value Alignment: From Authoritarian to Democratic AI Ethics. AI and Ethics 2025, 5, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihon, P.; Maas, M.M.; Kemp, L. Should Artificial Intelligence Governance Be Centralised? Design Lessons from History. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, New York, NY, USA, 2020; AIES ’20, pp. 228–234. [CrossRef]

- Attard-Frost, B.; Widder, D.G. The Ethics of AI Value Chains. Big Data & Society 2025, 12, 20539517251340603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.; Cant, C.; Graham, M.; Ustek Spilda, F. The Poverty of Ethical AI: Impact Sourcing and AI Supply Chains. AI & SOCIETY 2025, 40, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widder, D.G.; Nafus, D. Dislocated Accountabilities in the “AI Supply Chain”: Modularity and Developers’ Notions of Responsibility. Big Data & Society 2023, 10, 20539517231177620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, F.; MacDonald, M. Artificial Intelligence Policy Innovations at the Canadian Federal Government. Canadian Journal of Communication 2019, 44, PP–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C.; Antoniou, J.; Bhalla, N.; Brooks, L.; Jansen, P.; Lindqvist, B.; Kirichenko, A.; Marchal, S.; Rodrigues, R.; Santiago, N.; et al. A Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence Impact Assessments. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 12799–12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Huang, T.H.K.; Verma, H.; Mauri, A.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Bozzon, A. Empowering Local Communities Using Artificial Intelligence. Patterns 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.M.; , Daniel, F.; and Vanclay, F. Social Impact Assessment: The State of the Art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2012, 30, 34–42. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, C.; Román García, S.; Barnett, G.C.; Jena, R. Democratising Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Community-Driven Approaches for Ethical Solutions. Future Healthcare Journal 2024, 11, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, P.; Arduino, F.R.; Prisco, D.D. The Era of Artificial Intelligence: What Implications for the Board of Directors? Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 2024, 25, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collina, L.; Sayyadi, M.; Provitera, M. Critical Issues About A.I. Accountability Answered. California Management Review Insights 2023. [Google Scholar]

- da Fonseca, A.T.; Vaz de Sequeira, E.; Barreto Xavier, L. Liability for AI Driven Systems. In Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence and the Law; Sousa Antunes, H.; Freitas, P.M.; Oliveira, A.L.; Martins Pereira, C.; Vaz de Sequeira, E.; Barreto Xavier, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 299–317. [CrossRef]

- Buiten, M.; de Streel, A.; Peitz, M. The Law and Economics of AI Liability. Computer Law & Security Review 2023, 48, 105794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, K.; Smith, G.; Downey, C. U.S. Tort Liability for Large-Scale Artificial Intelligence Damages: A Primer for Developers and Policymakers. Technical report, Rand Corporation, 2024.

- Andrews, C. European Commission Withdraws AI Liability Directive from Consideration, 2025.

- Tschider, C. Will a Cybersecurity Safe Harbor Raise All Boats? Lawfare 3/20/2024 1:42:01 PM.

- Shinkle, D. The Ohio Data Protection Act: An Analysis of the Ohio Cybersecurity Safe Harbor. University of Cincinnati Law Review 2019, 87, 1213–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Oberly, D.J. A Potential Trend in the Making? Utah Becomes the Second State to Enact Data Breach Safe Harbor Law Incentivizing Companies to Maintain Robust Data Protection Programs. ABA TIPS Cybersecurity & Data Privacy Committee Newsletter 2021.

- Blumstein, J.F.; McMichael, B.J.; Storrow, A.B. Developing Safe Harbors to Address Malpractice Liability and Wasteful Health Care Spending. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e233899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, E.S.; Knoppers, B.M.; Zawati, M.H. Towards an Ethics Safe Harbor for Global Biomedical Research. Journal of Law and the Biosciences 2014, 1, 3–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, J. McNerney Introduces Bill to Establish Safety Standards for Artificial Intelligence While Fostering Innovation, 2025.

- Just, N.; Latzer, M. Governance by Algorithms: Reality Construction by Algorithmic Selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society 2017, 39, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Zhang, H.; Taeihagh, A. Why and How Is the Power of Big Tech Increasing in the Policy Process? The Case of Generative AI. Policy and Society 2025, 44, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).