1. Introduction

In recent years a number of interesting physical phenomena have been established for laser beam propagation in multimode optical fibers (see e.g., overview [

1]). Among them there is a phenomenon of self-cleaning of the laser beam when an injected laser power at high modes is transferred to low-energy modes. It was realized that this effect appears due to thermalization among linear fiber modes induced by nonlinear four-wave interactions between modes [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Thus, even thermalization with negative temperatures has recently been observed in such optical fibers [

7]. It is argued that this thermalization emerges as a result of purely Hamiltonian dynamics without any external thermal bath.

The phenomenon of dynamical thermalization attracts a deep interest of the scientific community, starting from the famous Boltzmann-Loschmidt dispute on thermalization emerging from the reversible dynamical equations of particle motion [

8,

9,

10] (see also [

11]). In modern times the interest in the problem of dynamical thermalization was pushed forward by numerical experiments of Fermi, Pasta, Ulam (FPU) in 1955 [

12] with the conclusion that “The results show very little, if any, tendency toward equipartition of energy between the degrees of freedom.” [

12]. The absence of thermalization in the FPU problem of linear oscillators with nonlinear couplings was found to be linked to its proximity to exactly integrable models with solitons [

13,

14,

15] and Toda lattice [

16,

17]. Also, at weak nonlinearity there is no overlapping of main system resonances, the system is below the chaos border, and the dynamics remains quasi-integrable [

18,

19,

20]. Such a regime corresponds to a spirit of Kolmogorov-Arnold-Moser (KAM) integrability which takes place at weak perturbation of integrable system while chaos and thermalization may appear only at relatively strong nonlinear perturbation (see details in [

21,

22,

23,

24]). At present the FPU problem still remains an active area of research [

25].

In fact an example of FPU problem shows that for investigations of dynamical thermalization in classical many-body systems it is important to choose a model corresponding to a generic situation of oscillators with nonlinear interactions. Such a generic model was proposed in [

26] with unperturbed Hamiltonian of linear oscillators described by a random matrix with additional nonlinear perturbations. Thus the linear oscillators are described by the Random Matrix Theory (RMT) invented by Wigner for a description of complex quantum systems like nuclei, atoms and molecules [

27]. At present RMT finds a variety of applications in quantum systems, mesoscopic physics [

28,

29] and systems of quantum chaos [

30,

31]. In [

26] it was shown that a nonlinear perturbation of RMT leads to dynamical chaos and the Rayleigh-Jeans thermal distribution over linear oscillator modes if nonlinearity strength exceeds a certain chaos border. In presence of additional dissipation and energy pumping this nonlinear random matrix (NLIRM) model describes also the spectra of Kolmogorov-Zakharov turbulence [

32]. A brief discussion of a model similar to NLIRM was also done in [

33].

In practice it may be not so easy to reach an experimental realization of such NLIRM model but in [

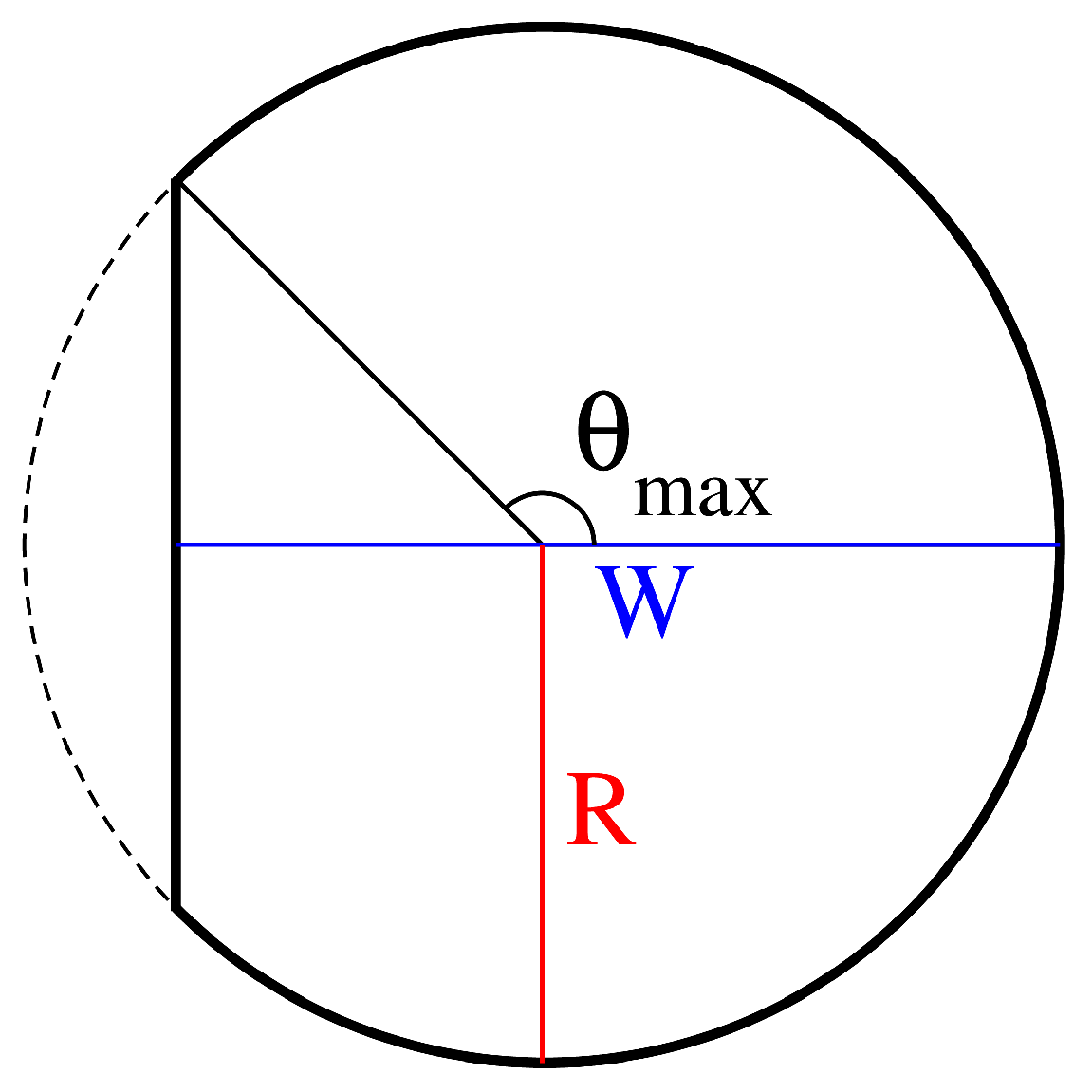

26] it was proposed that this system can be approximately presented by a multimode optical fiber with a fiber cross-section being a chaotic billiard, e.g., D-shape billiard (circle with a cut. see

Figure 1). Indeed, it is known that classically chaotic billiards have many properties being the same as for RMT [

30,

31]. It was shown that the quantum chaos exists for variety of cuts of a circle billiard [

34,

35,

36] even if for certain cut positions there can be present significant integrable islands. The advantage of D-shape billiard is that it can be relatively simply realized in multimode fibers. Indeed, observations of signatures of quantum chaos in D-shape billiard had been reported in [

35,

36,

37]. However, dynamical thermalization induced by nonlinearity was not studied in these works. We argue that such quantum chaos fibers can be used for investigations of dynamical thermalization for a generic case of oscillators with nonlinear interactions. In principle similar effects can be studied for lasing dynamics in semiconductor chaotic microcavities realized in [

38] but in this work we restrict our studies to the case of D-shape multimode fibers.

It is natural to ask what is the situation with dynamical thermalization observed with multimode fibers in [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. In fact in these circular shape fibers the spectrum of linear modes corresponds to a spectrum of two oscillators with equal frequencies that leads to a significant spectrum degeneracy. In such a case the KAM theory for nonlinear perturbation of such a system is not applicable [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Thus in [

39] it was shown that for three oscillators with equal frequencies, the measure of chaotic component remains on a level of 50% for arbitrary weak nonlinear perturbation (its strength only gives a reduction of the positive Lyapunov exponent but not the measure of chaos). Similar effects exist for other nonlinear systems [

40] and the FPU

-model [

41]. Thus for fibers, which have spectrum of two oscillators with equal frequencies, as those in [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], we expect that arbitrary small four-wave nonlinear interaction, that couples these modes, should lead to a chaotic dynamics and eventual thermalization between degenerate modes. However, since the Lyapunov exponent decreases with the nonlinearity strength (as in [

39,

40,

41]) one would need to have longer and longer fiber to reach such chaotization. It is possible that certain non homogeneous perturbations along a fiber act as a time-dependent noise and facilitate development of chaos. Due to these reasons we argue that the experiments [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] are done in a specific regime of degenerate mode spectrum when the KAM theory is not valid and thus it is of fundamental interest to study the generic case of D-shape fiber when the KAM theory works and dynamical thermalization appears only above a certain chaos border. We should note that the mathematical KAM theory results for the NSE in billiards are very difficult to obtain and the question about asymptotic time behavior of nonlinear spreading on high energy modes remains open for chaotic billiards and moderate nonlinearity (see e.g. [

42]).

With this aim we present here the numerical and analytical study of dynamics of nonlinear waves in D-shape billiard described by the Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation (NSE), or the Gross-Pitaevskii equation (GPE) [

43], which depicts the laser beam propagation in multimode fibers [

1]. We note that the onset of dynamical thermalization for the NSE with defocusing nonlinearity

in a chaotic Bunimovich billiard was studied in [

44]. The results reported there show emergence of dynamical thermalization above a chaos border when nonlinear perturbation exceeds a typical energy level spacing in such a billiard. However, in [

44] only relatively short times were reached in numerical simulations and the Rayleigh-Jeans distribution was not reached. Here we significantly increased the time evolution scale with emergence of the Rayleigh-Jeans thermalization in a D-shape fiber (billiard) with defocusing nonlinearity.

Another important feature is that usually for fibers a nonlinearity is focusing

and thus, according to the so called Vlasov-Petrishchev-Talanov theorem [

45,

46], a wave collapse can take place for strong nonlinearity at finite times. Important implications of such a collapse for Langmuir waves was discussed in [

47]. However, in [

45,

46,

47] a collapse was discussed in a case of infinite system size. For a D-shape fiber chaos and thermalization in a finite size billiard may lead to an unusual interplay between collapse and dynamical thermalization so that there is a fundamental interest to study the properties of NSE in a D-shape focusing fiber. Here we present results of our studies of such a system considering both cases of negative (focusing) and positive (defocusing) signs of nonlinearity. We show that that the dynamical thermalization with the Rayleigh-Jeans distribution takes place at moderate strength of nonlinearity being above the chaos border. Below this border the dynamics is quasi-integraable corresponding to the KAM theory.

It is interesting to note that the GPE describes Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) of cold boson atoms in optical trap [

43]. Thus there is a temptation to expect [

44] that the dynamical thermalization for GPE or NSE in a chaotic billiard would lead to the thermal Bose-Einstein (BE) distribution over eigenenergies

of linear system [

48]:

However, NSE describes classical nonlinear fields without second quantization and thus in this case we should have the classical Rayleigh-Jeans (RJ) thermal energy equipartition with chemical potential

due to an additional conservation integral of norm or number of particles, see e.g. [

48,

49]:

In the distributions (

1), (

2)

T is a system temperature,

is a chemical potential and the total norm of probabilities

on

N energy levels

is preserved and normalized to unity (

;

). In optical fibers such classical thermal distribution (

2) is usually called as Rayleigh-Jeans (RJ) distribution (see e.g. [

3]). Indeed, in [

26] for the NLIRM and related models it was shown that above the chaos border the dynamical chaos at moderate nonlinearity leads to the RJ thermal distribution and not to the BE one. For dynamical systems like NSE we assume that the nonlinear term is relatively weak or moderate and it leads to dynamical chaos for nonlinearity above the chaos border producing thermal distribution (

2) over linear eigenenergies (or mode eigenfrequencies) that are not significantly affected by weak nonlinearity.

In fact the RJ distribution is a limiting case of the BE one in the limit of high temperature significantly exceeding typical energies of the linear system (

). Using this RJ description of BE distribution at high temperature Fröhlich showed in 1968 that for the RJ distribution there is a significant condensation of probability at the lowest system energy level that may be close to hundred percent of total probability norm or total number of bosons [

50,

51]. The model proposed by Fröhlich assumes a presence of external pumping of the system in presence of dissipative process leading to a certain steady-state. The total number of phonons in the system depends on a pumping strength leading to condensation in the ground state above a certain critical strength. Thus this model does not directly correspond to the RJ thermal distribution studied here, but there are still certain similarities due to the fact that the steady-state in [

50,

51] is described by the RJ distribution with a certain prefactor depending on pumping and dissipation.

On the basis of this result Fröhlich made a conjecture that such a condensate, appearing at high temperatures, concentrates energy in a single mode and thus it can play an important role in coherent properties of cell membranes and biomolecules. This conjecture attracted a significant interest of physicists and biologists with a large number of theoretical and experimental studies of this phenomenon called Fröhlich condensate, see e.g. [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

In this work we show that in the RJ thermal distribution (

2) there is also condensation at the ground state, which we call Rayleigh-Jeans (RJ) condensate. This RJ condensate captures almost all norm, or number of particles, it emerges at low temperatures (

) and high number of levels in the system. Since RJ condensate appears only at low temperatures it describes the thermalization of classical fields since for quantum systems the thermalization is described by the BE distribution (

1) which at low temperatures is very different from RJ one (

2). Thus the RJ condensate exists only at low temperatures (

) at norm conservation and absence of external pumping. Hence it is very different from the Fröhlich condensate which exists at high temperatures (

) in presence of external pumping.

We argue that the self-cleaning effect [

1,

2] is an example of the RJ condensate appearing due to chaos induced by nonlinear interaction of waves in multimode fibers. The emergence of such condensation was also reported for numerical simulations of NSE in two and three dimensional finite systems with quadratic spectrum of waves [

58,

59,

60,

61]. In these works the emergence of RJ distribution was attributed to the Kolmogorov-Zakharov spectra of turbulence [

49]. However, as argued above, we attribute the appearance of RJ thermal distribution in these numerical simulations to the degeneracy of linear eigenmode frequencies due to which the KAM theory cannot be applied to these systems and thus chaos appears at very weak nonlinearity strength. For the case of focusing fibers we discuss an interesting interplay between the wave collapse and chaos. We also consider the problem of ultraviolet catastrophe at high energy modes in a chaotic regime.

Finally, we note that a laser beam propagation in a nonlinear Kerr media with atomic vapor [

62] is also described by the NSE which we study here. The important advantage of this physical system is that the sign of NSE nonlinearity can be easily changed by a frequency detuning of a laser beam. In [

62] it was experimentally and numerically demonstrated a formation of vortexes of such light fluid described by a dissipative NSE within a circular integrable billiard cross-section. Here we show that in the case of chaotic D-shape cross-section there are also long living vortexes described by the unitary NSE evolution. The NSE dynamics of laser beam propagation in fiber or other nonlinear media is also considered as a fluid of light [

61,

62]. In fact the NSE and GPE are closely related to the Ginzburg-Landau equation used for the description of superconductivity, superfluidity and quantum turbulence as it is described in the reviews [

63,

64,

65,

66].

The article is composed as follows:

Section 2 presents the model and description of quantum chaos properties in absence of nonlinearity, numerical methods of integration of NSE are given in

Section 3, results for simple models with RJ condensate are displayed in

Section 4, the results for dynamical thermalization for defocusing fiber NSE are described in

Section 5, properties of the wave collapse for focusing NSE are presented in

Section 6, the dynamical thermalization for focusing fiber NSE is described in

Section 7, properties of vortexes in defocusing fiber NSE are displayed in

Section 8, NSE long time dynamics is discussed in

Section 9, experimental parameters for a quantum chaos fiber are displayed in

Section 10, discussion and conclusion are given in

Section 11. Appendix presents some additional results.

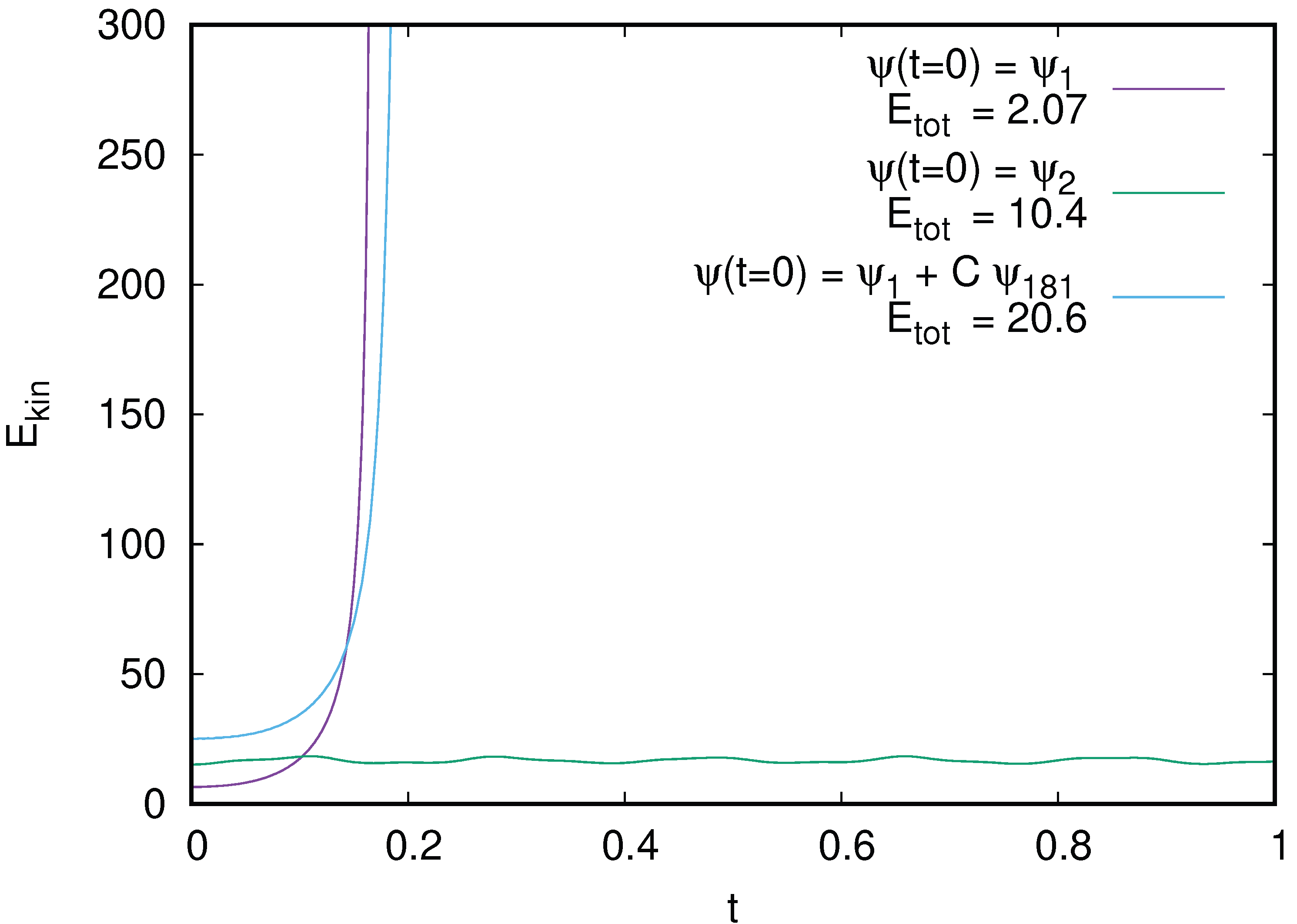

6. Wave Collapse for Focusing Fiber NSE

It is known that for the focusing NSE on an unrestricted 2D plane the wave collapse takes place in a finite time if initial total energy of the system is negative [

45,

46]. Here we show that the collapse in a finite D-shape billiard can take place at moderate negative nonlinearity

and certain positive energy. A typical example is shown in

Figure 19 at

where the initial state at

is taken as the ground state of linear system. Here the collapse happens at rather short time

even if the initial total energy at this

is positive being

. At

the kinetic energy of the system

diverges growing to infinity. Indeed, approaching the collapse time

the wave function is localized in smaller and smaller area

in

plane and due to norm conservation

is growing so that negative nonlinear energy is also increasing as

. Thus due to the conservation of total energy we have divergence of kinetic energy

. Special checks ensure that these results are independent of the numerical integration parameters

and

. For the initial state taken at the next energy level with

at

with the total energy

there is no collapse and kinetic energy

simply oscillates around its initial value. A similar collapse is also present at

.

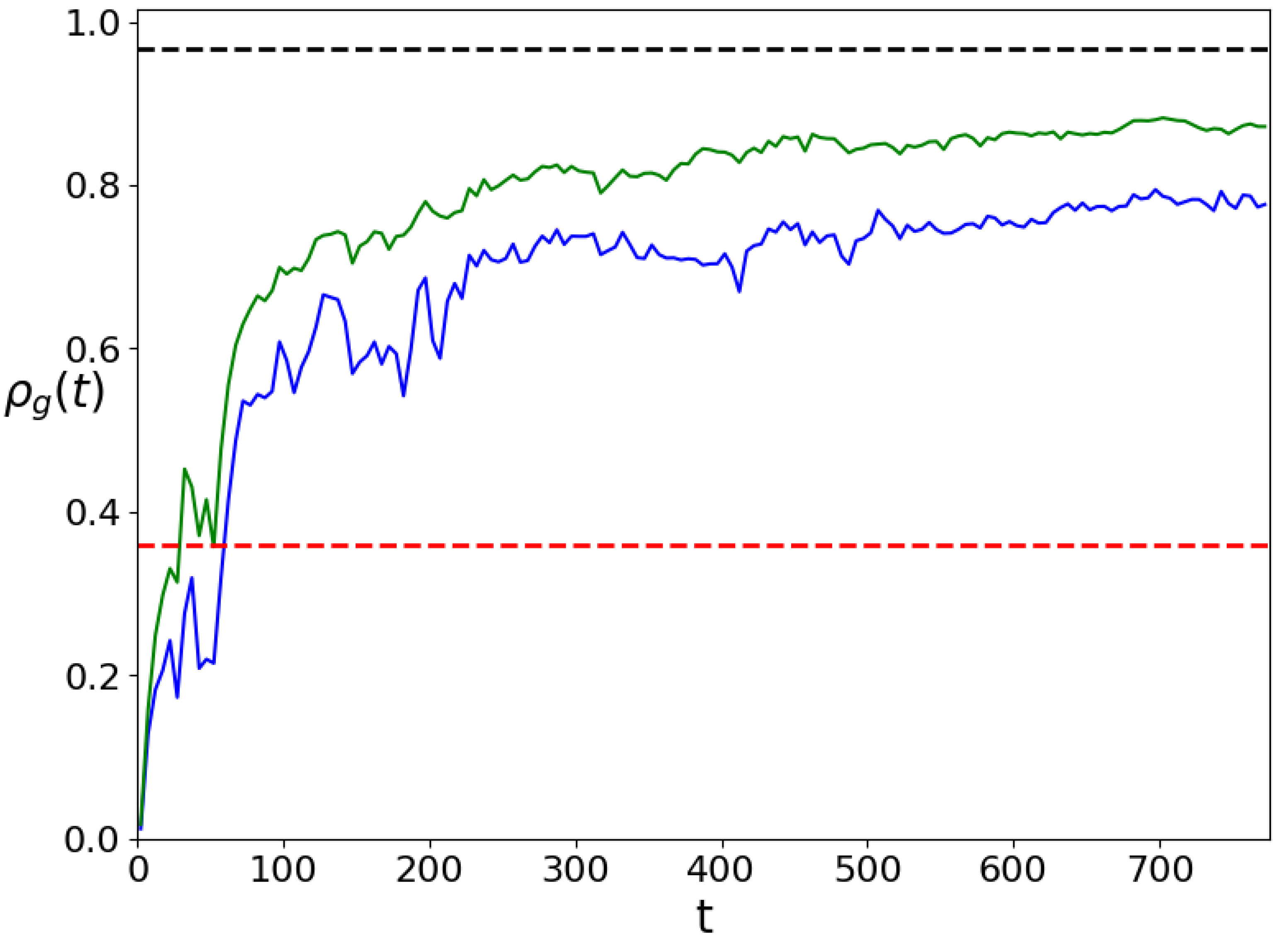

We saw above that for

, e.g.

, due to dynamical thermalization with RJ thermal distribution (

2), a significant fraction of total probability is accumulated in the RJ condensate at the ground state

with

. This probability

can be around 80%-90% (see

Figure 12,

Figure 13). For negative values of

we expect that the dynamical thermalization leads also to emergence of RJ condensate with a high condensate probability fraction. Thus it is important to see if the collapse can take place for an initial state with a high probability at the linear ground state and a relatively small probability at high energy state. To study such a situation we choose the initial state being

with

. Thus at

there are about 96.8% of probability in the ground state

and 3.2% at the excited state

. For

the results show that there are time oscillations of

with a significant increase of

but the collapse is avoided due to presence of high energy component of wave function (see top panel of

Figure 20). However, for

still the collapse takes place at

even if the initial total energy is rather high

(see

Figure 19).

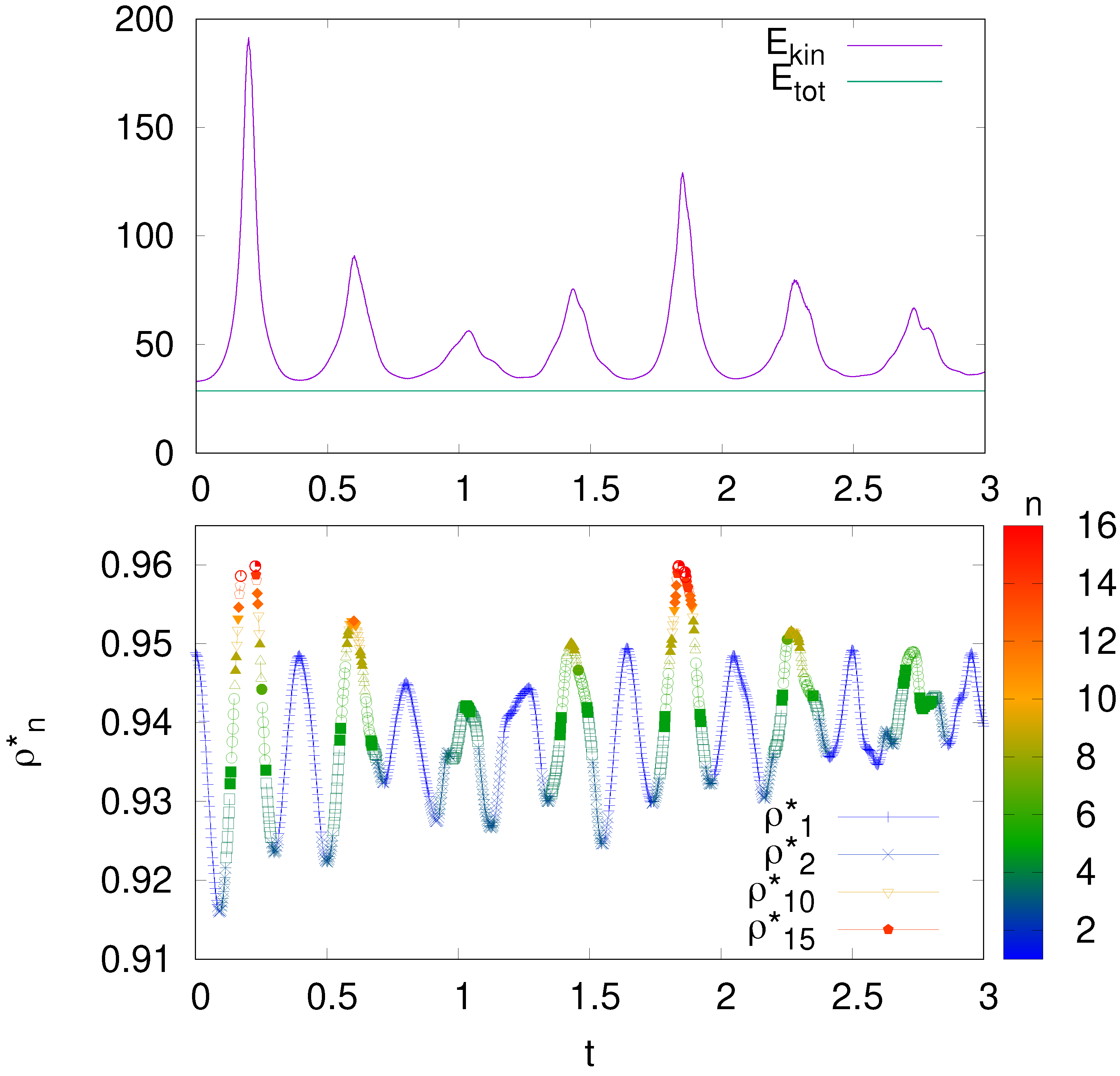

In the pre-collapse regime at

there is an interesting behavior of wave function

that can be seen by its projection probability

on the eigenbasis

of the Schrödinger equation (

3) in which the nonlinear term is considered as the instantaneous effective attractive potential

. The dependence of

on time

t is shown in the bottom panel of

Figure 20. At small times

there is about

to

probability located at the ground state

of the instantaneous potential

. But

is changing with time that leads to a transition of almost all fraction of

to other eigenstate at

at higher moment of time

t. Then with growth of

t there are transitions to high and higher states

n of instantaneous potential

. The maximal

n values (up to

) are reached at the minimal size of wave function corresponding to the maximal values of

in the top panel. Then, when the packet squeezing passed, its maximal value and the packet size starts to increase the population

starts again go to minimal

n values returning back to almost all probability at the ground state

of

when the packet returns of its maximal site (minimal of

in the top panel). It is interesting to note that the transitions between states

n happens in diabatic manner with almost all probability transferred from one

n value to another one. These results show that in the pre-collapse regime there is rather nontrivial time evolution of wave function with its oscillating size. It would be interesting to study this behavior in more detail but this goes outside of scopes of this work.

Thus we show that the wave collapse in a focusing NSE inside a chaotic billiard can take place even at rather highly positive values of total system energy when a probability fraction on high energies is relatively small. Thus there should be a certain boundary in the space of total energy and probability on high levels (

in

Figure 19,

Figure 20). In global this boundary determines the regime of collapse stability in respect of perturbations produced by high energy waves. Since the collapse remains stable only at rather small probability at high energies we expect that in the regime of dynamical thermalization and appearance of RJ condensate there will be no wave collapse at moderate negative

values. The results of dynamical thermalization at negative

are presented in the next Section.

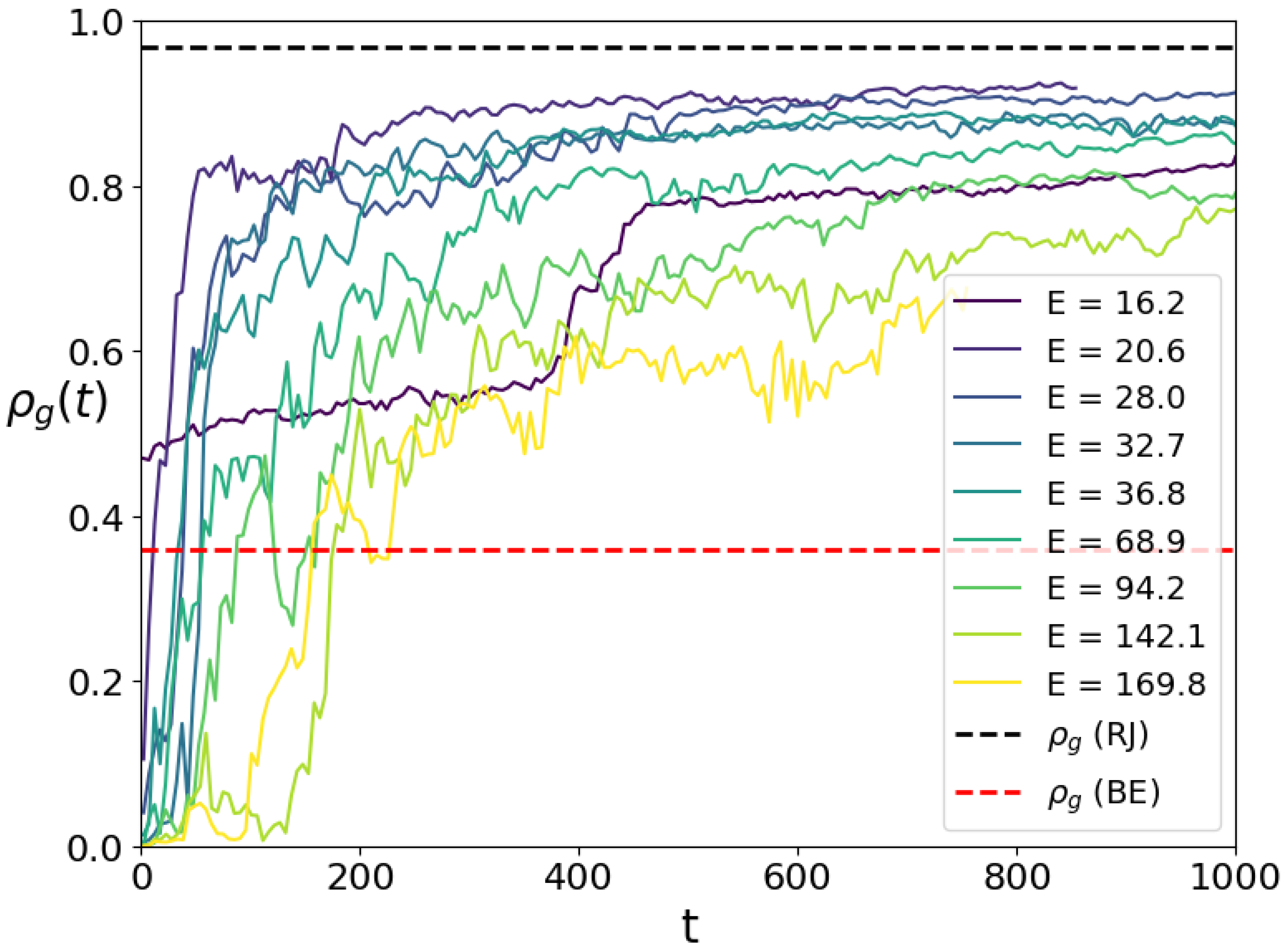

7. Dynamical Thermalization in Focusing Fiber NSE

For negative nonlinearity

in (

3) the dynamical thermalization has the features similar to the case

with certain specific aspects related to the wave collapse discussed above. Thus in

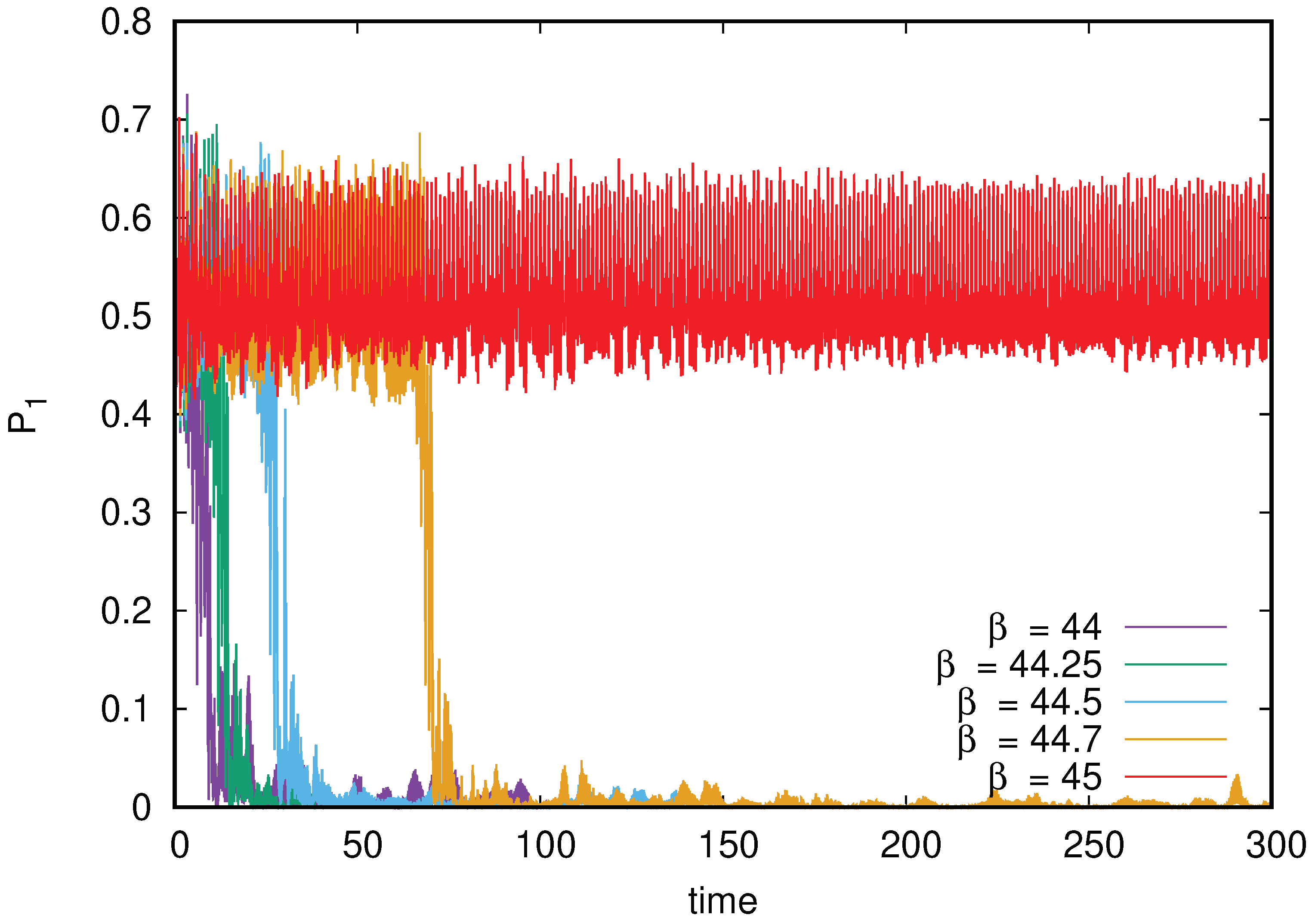

Figure 21 we show the time dependence of projection probability

on the linear ground state

for a typical case with

and initial state

at

. At long times

t it approaches to

showing the formation of RJ condensate. This behavior is similar to those at

in

Figure 12 with the same initial state. In

Figure 21 we add also the projection probability

on the ground state of the instantaneous effective potential

as it was done in

Figure 20 bottom panel for the case of wave collapse. At long times when the steady-state is established we obtain

being higher than

. Thus a higher fraction of RJ condensate is captured by attractive instantaneous potential

. However, these fractions of RJ condensate are still not sufficiently high and there is no wave collapse. We also find the similar

time dependence for other initial states

at

and

(see Appendix

Figure A4).

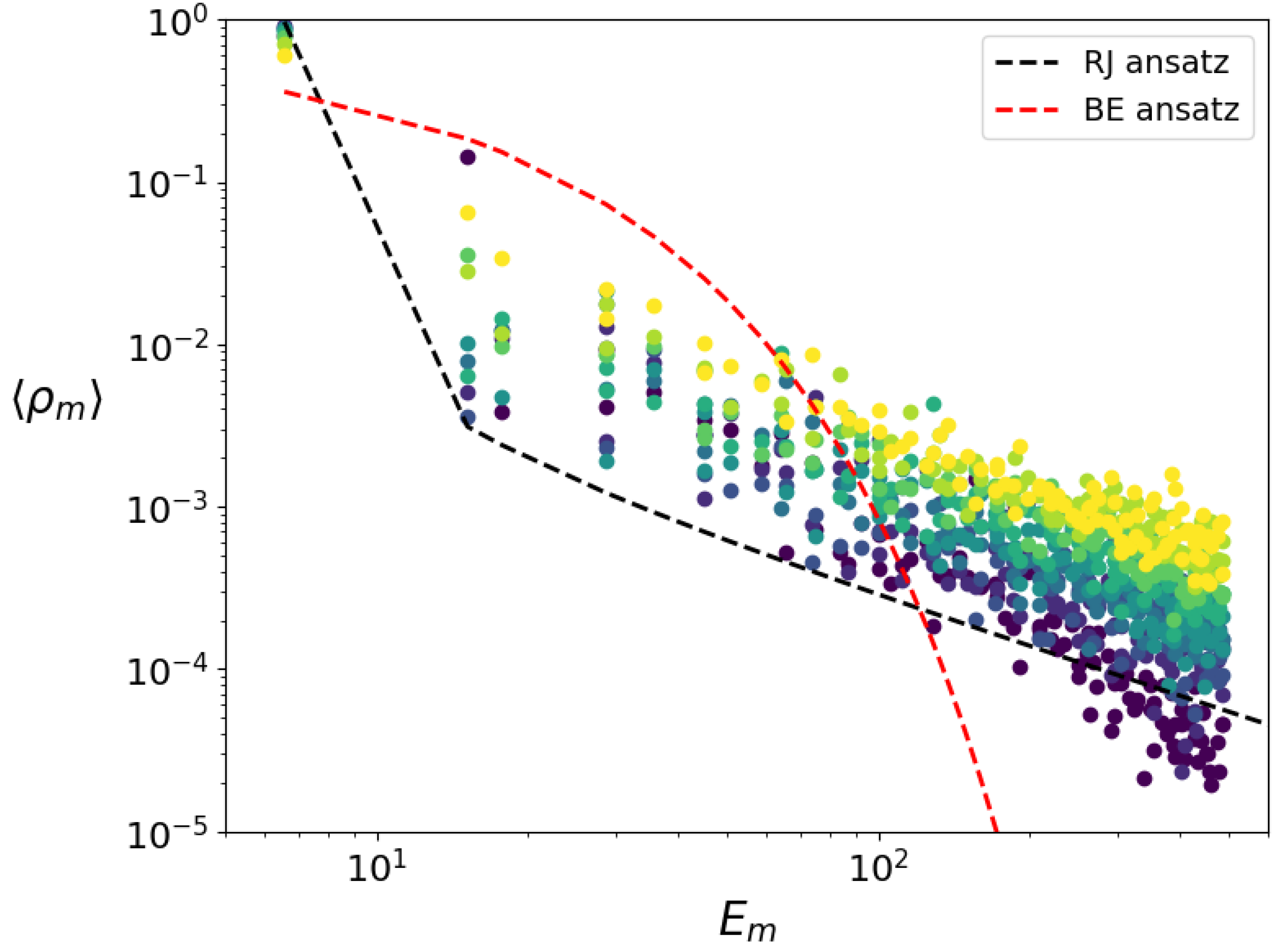

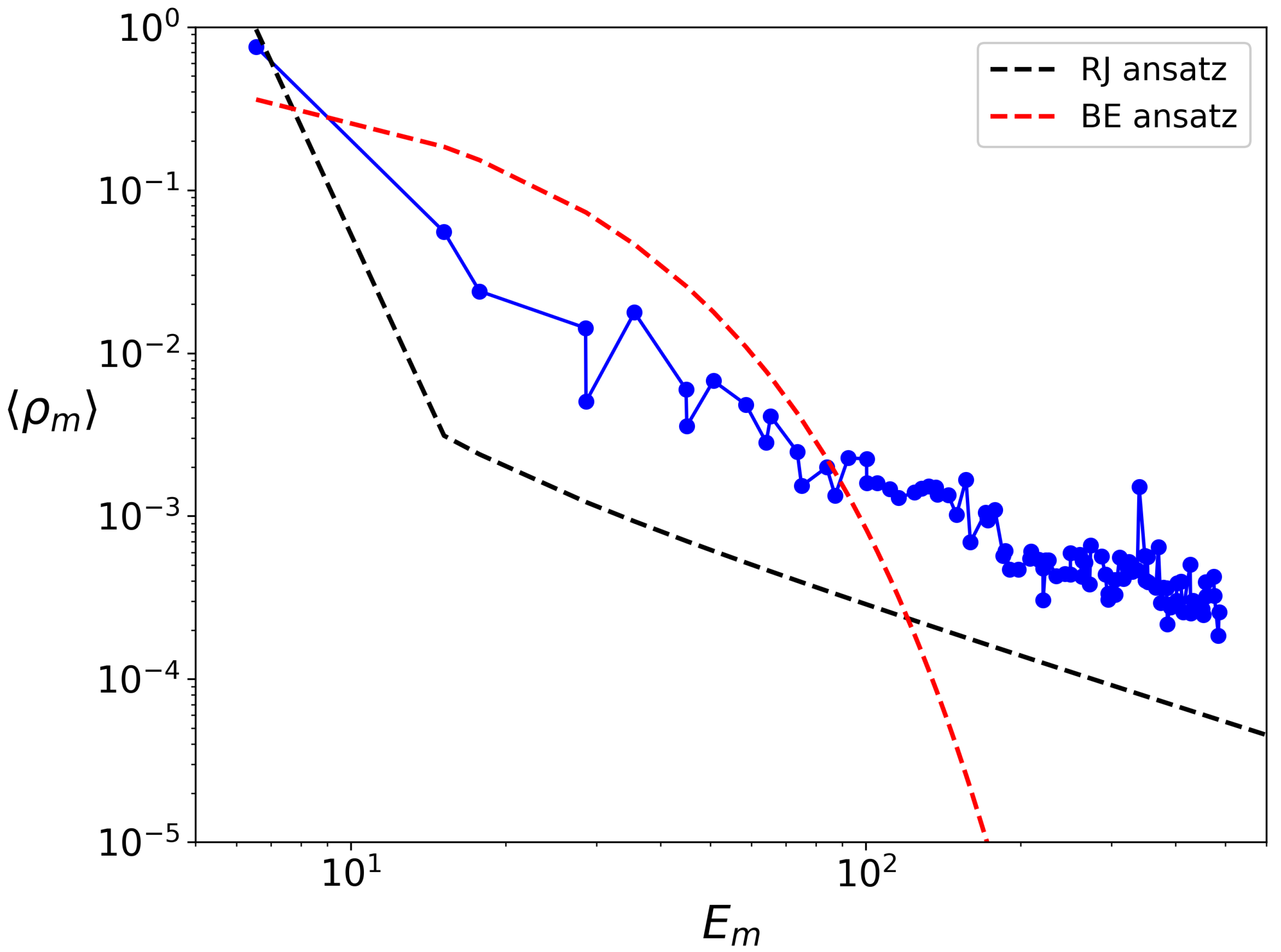

In

Figure 22 we show the probabilities

averaged in the time interval

with dashed curves showing the RJ ansatz (

2) and BE ansatz (

1) corresponding to energy

E of the initial state (for RJ case we assume the total number of levels

). As for the case of

Figure 13 at

we find that the RJ ansatz provides a good description of the steady-state distribution even if the RJ fraction

is higher comparing to the numerically obtained value

(due to that the RJ curve is located below the numerical

values but the energy dependence

on

remains the same). Also the results show that the BE ansatz is not working. The similar results at

are shown in Appendix

Figure A5 for other initial states

at

and

.

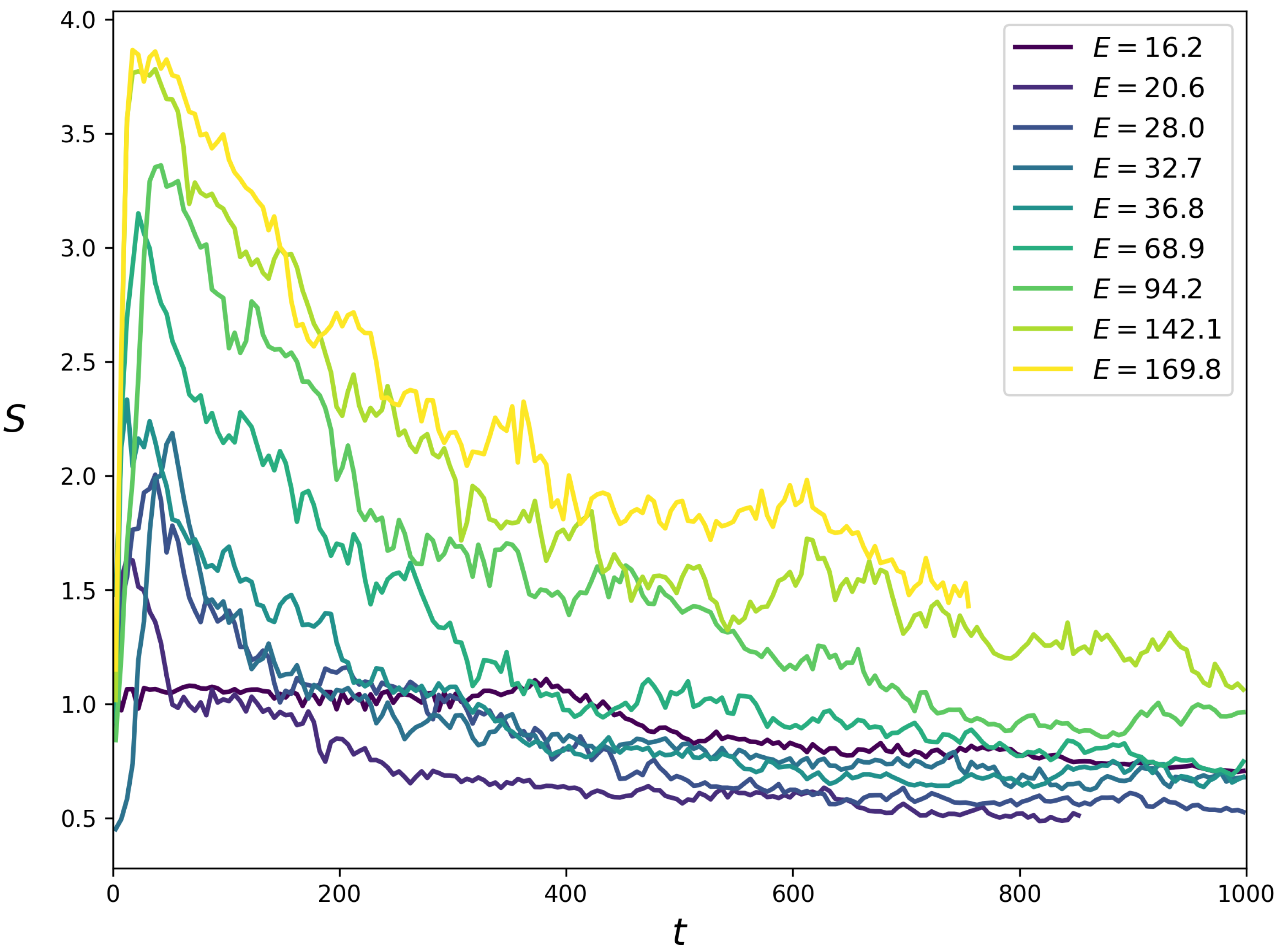

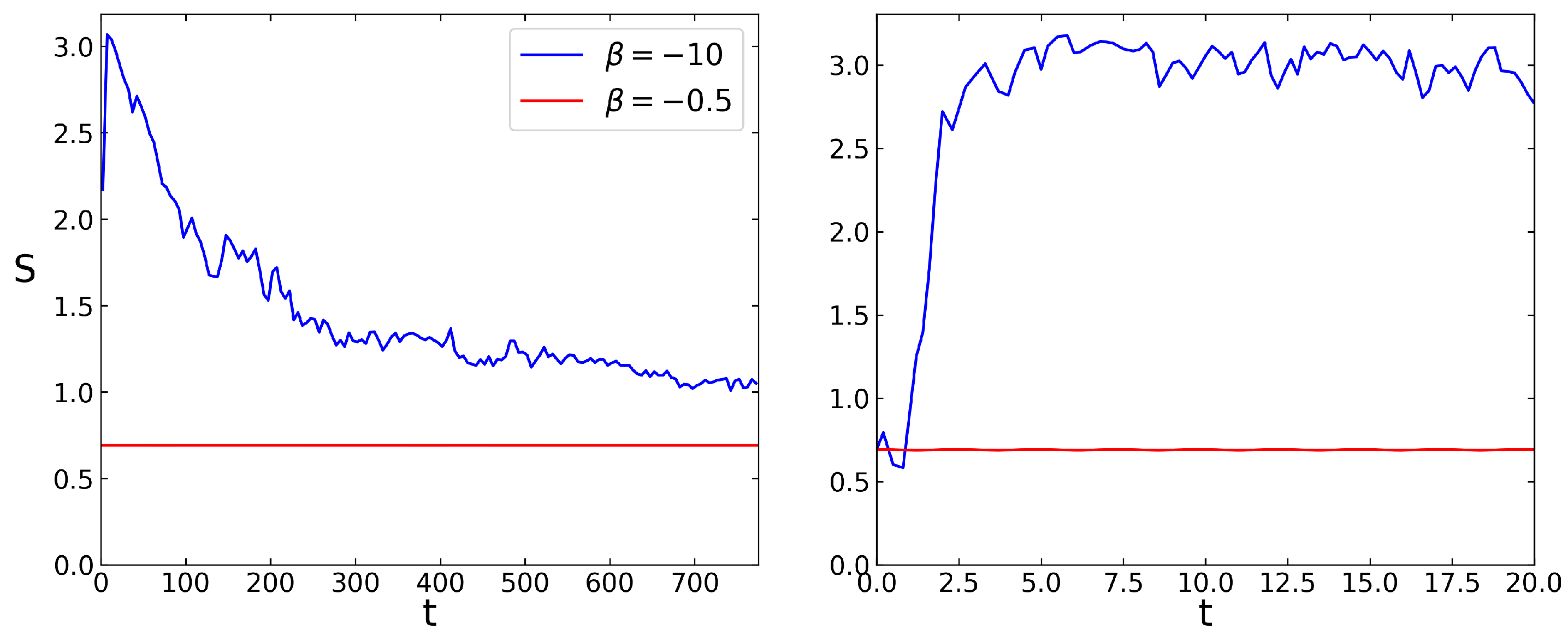

The time dependence of entropy

at

and initial state

at

is shown in

Figure 23. This dependence is similar to those in

Figure 14 at

. At small

the entropy remains practically unchanged corresponding to the KAM regime. In this quasi-integrable KAM regime at

only regular probability oscillations in time (see Appendix

Figure A6).

Thus we conclude that the process of dynamical thermalization is very similar for positive and negative values of nonlinearity

in (

3). For significantly negative

value the collapse can take place even at positive total energies but then the initial state should have probability at the linear ground state being very close to unity.

8. Vortexes in Defocusing Fiber NSE

It is well known that the defocusing NSE in 2D unrestricted plane have vortexes at strong nonlinearity

[

65,

66]. The properties of vortexes have been studied theoretically, numerically and experimentally with superfluidity in liquid helium [

65,

66] and with light fluid in nonlinear media of atomic vapor [

62]. It is known that an effective size of vortex scales in dimensionless units as

[

65,

66]. A good agreement between numerical NSE modeling and experimental results has been demonstrated in [

62].

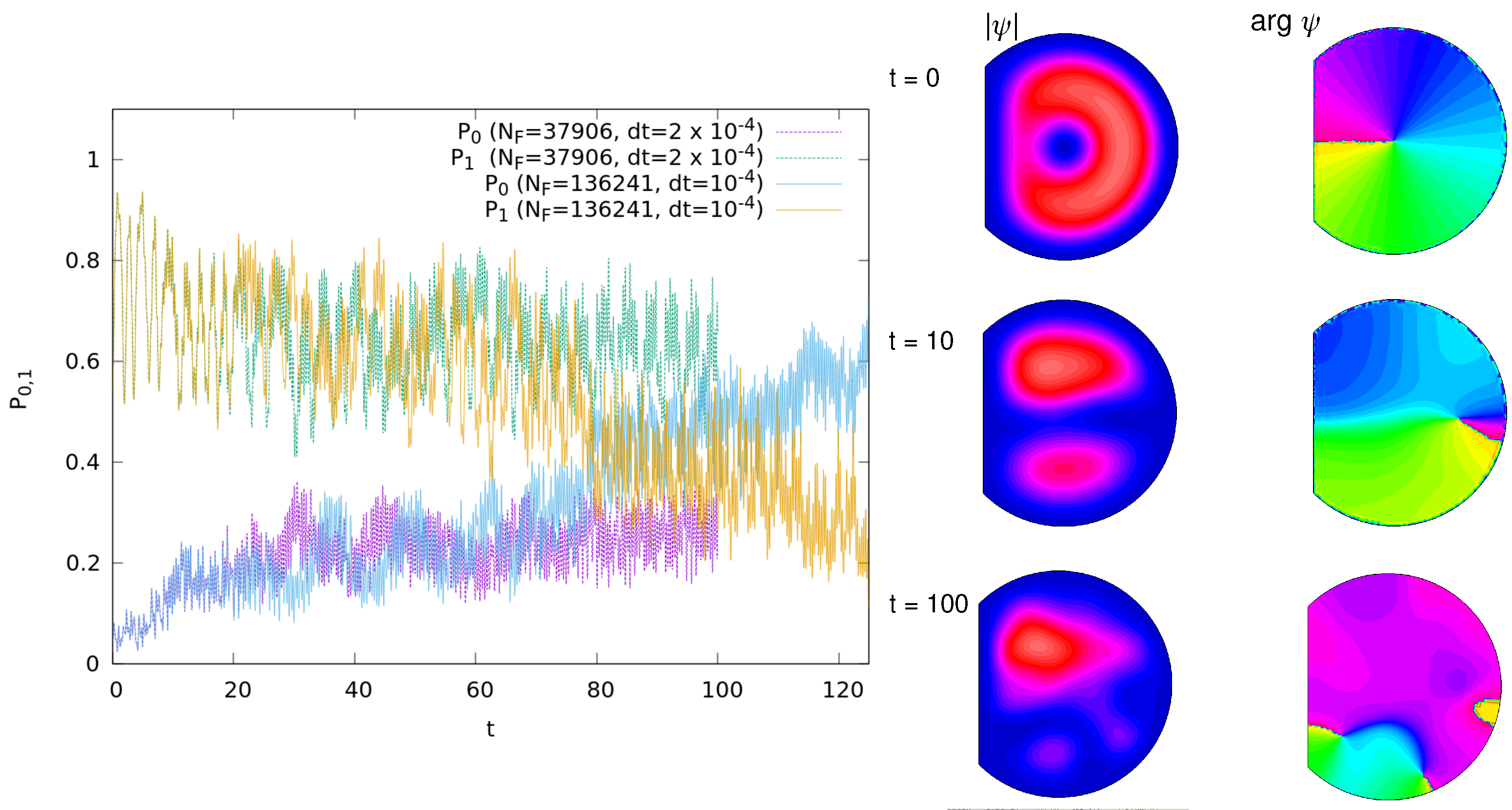

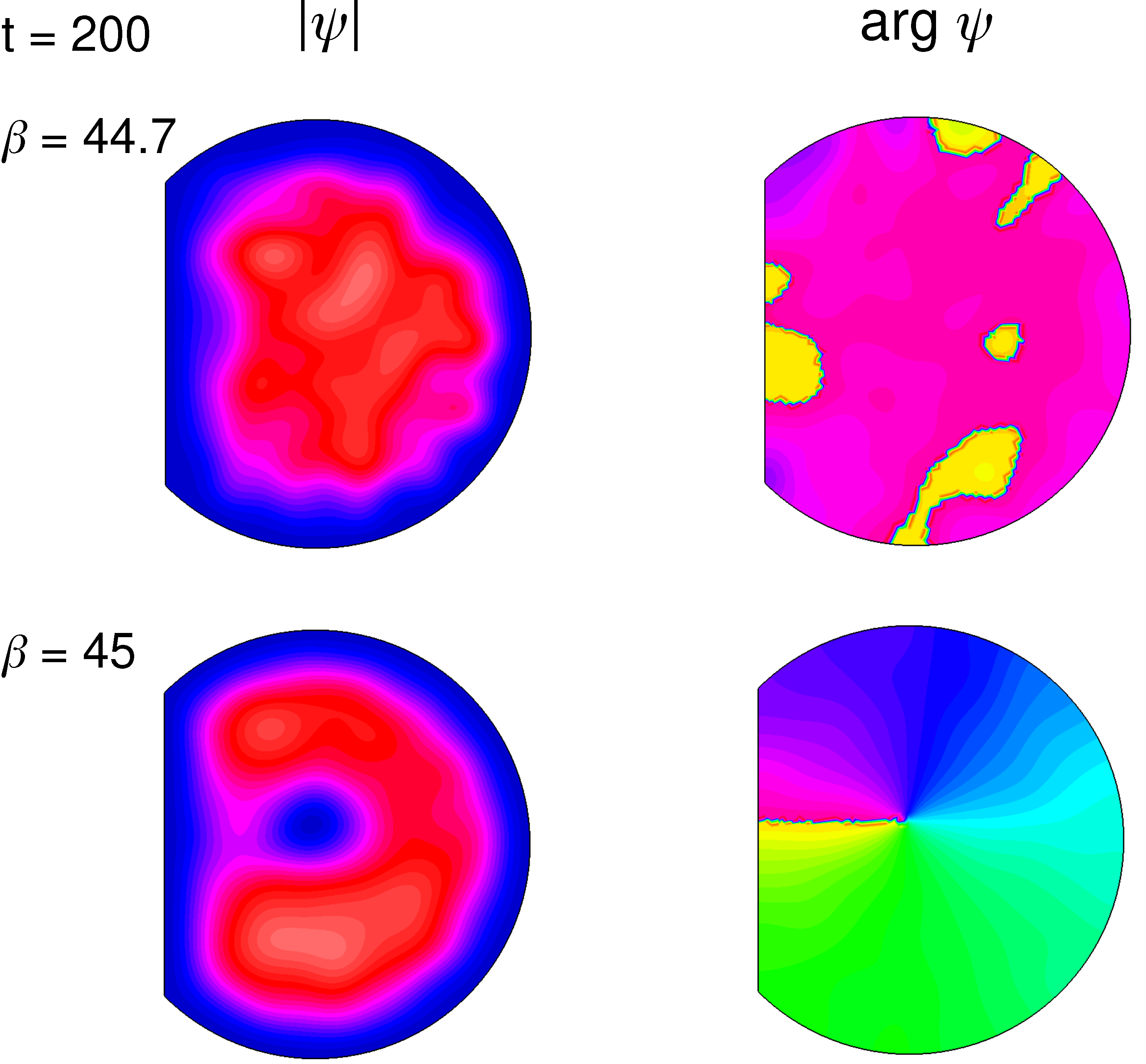

Here we study the properties of vortex in a chaotic D-shape billiard in the frame of defocusing NSE (

3). In the results presented above the initial state

was always chosen as a certain combination of linear modes. However, to study the vortex dynamics we need to start with initial state having initial vorticity. Thus we start with an initial state shown in

Figure 24, it is close to a vortex field in an open 2D plane with

[

65,

66]. This state has a significant projection probability

on the first excited linear mode

at

. Thus the high value of probability

indicates that the vortex is well survived in time even if the classical dynamics of rays is chaotic in the billiard at

. In contrast, if the projection probability

on th ground state linear mode

at

becomes high and

becomes low then this indicates that the vortex is destroyed by quantum chaos and nonlinearity.

The time evolution of projection probabilities

for vortex time dynamics is shown in

Figure 24 (left panel) for moderate nonlinearity

. For a small integration time step

and high number of FREEFEM net nodes

we have high numerical conservation of norm and total energy integral. For time

the results show that

probability starts to grow significantly while

probability starts to drop rapidly that tells about the complete destruction of vortex at times

. This is confirmed by color vortex images in the right panel of

Figure 24: vortex structure is well visible at

both for wave function amplitude

and its phase

showing clear phase rotation. In contrast at

both

and

show disappearance of vortex. For times

the vortex is destroyed and the dynamical RJ thermalization takes place for nonlinear field

. Indeed, the results for

show its significant growth so that its value becomes close to the probability fraction of RJ condensate and

(see

Figure 12). At the same time the projection probability

drops significantly similar to the cases shown in

Figure 13. Thus the dynamical RJ thermalization works also for the initial vortex states at moderate nonlinearity

.

It is interesting to note in the left panel of

Figure 24 that at smaller number of nodes

the evolution of vortex is more stable with higher projection probability

at

comparing to the case with significantly higher integration parameters

and

. We interpret this by assuming that the lower value

leads to a certain effective roughness of induced effective potential that reduces velocity of vortex center decreasing the quasi-particle excitation thus increasing vortex life-time.

The dynamics of vortexes at a moderate nonlinearity

tends to approach the dynamical thermalization even if the votrex life time

can be relatively high. At high

values the vortex size decreases as

and its interactions with billiard border becomes weaker with the growth of vortex life-time

as it is show in

Figure 25 where the projection probability

remains high for longer and longer times. However, we find here a striking effect when this vortex life-time

changes abruptly from

for

to

for

. This sharp transition in

is also well seen in

Figure 26 where the snapshots of nonlinear field

are shown at

: for

the vortex is completely destroyed while for

it is well preserved. The vortex time evolution is also shown in Supplementary Material (SupMat) video (file videovortex.mp4) for vortex time evolution at

(left panel, vortex is destroyed at maximal shown

) and at

(right panel, vortex is well survived at

). This video shows that at

the center of vortex moves more rapidly compared to those at

. Thus we make a superfluid transition conjecture: at

the velocity of vortex center is higher than the critical superfluid velocity of light fluid and it starts to radiate quasi-particles breaking superfluidity, while for

this velocity is below critical superfluid velocity and the vortex life-time is increased enormously or may become even infinite. The verification of this superfluid transition conjecture requires further studies which are beyond the scope of this work.

9. Nse Dynamics at Long Times

The question about asymptotic properties of NSE dynamics in the D-shape chaotic billiard at long time scales is rather complex. The NSE (

3) can be rewritten in the basis of linear eigenmodes

of the billiard (at

) where it reads:

Here are wave function amplitudes in the eigenbasis so that and interaction matrix elements induced by nonlinearity are .

This type of equation appears also in the models on nonlinear perturbation of quantum chaos [

72], Anderson localization (DANSE model for Discrete Anderson Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation) [

73,

74,

75,

76] and Random Matrix Theory (RMT) [

26] (NLIRM model). In these models the norm and total energy are exactly conserved as for NSE model (

3). For DANSE type models [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76] the linear eigenstates are exponentially localized due to quantum interference and Anderson localization so that the coupling matrix elements are

for states

located on a distance of localization length

from each other on a lattice, while outside of this range the values of

V drop exponentially. Here

is a number of lattice states in a localization length and for a

d-dimensional lattice with disorder we have

[

74].

For such type DANSE models it was shown that for a nonlinearity above a certain chaos border

there is a slow subdiffusive spreading of probability over the lattice sites

n with the width growing as

with the subdiffusive exponent

[

72,

73,

74,

75,

76]. This growth continues during all computational times up to extremely long times

.

It is interesting to note that for the DANSE models considered in [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76] the spectrum of linear modes is bounded in a certain finite energy band. However, the DANSE type model studied in [

77] has a Stark lattice with on-site energies growing linearly with site

n index

and still the unlimited spreading was present up to maximal times

with an exponent

(in a chaotic regime with

). Due to energy growth with site number the model [

77] is similar to one studied here (

3) since in a 2D billiard energies of modes are also growing with mode index

. Thus due to such a similarity between the model [

77] and the present fiber model (

3) one could expect to have unlimited norm spreading with time up to higher and higher modes

m. However such an unbounded scenario has certain difficulties: indeed, if the total number of populated linear modes

grows with time then due to RJ condensation a main part of the total norm should be in the condensate phase being mainly at the linear ground state. From the view point of RJS model this norm should become closer and closer to unity with the growth of

N (see

Figure 8). Due to presence of stability island with self-consistent ground state we see that in the NSE fiber model (

3) RJ condensate has not more than approximately 90% of the total norm (see

Figure 12) so that only about 10% of norm can propagate to higher and higher

N values. In the case of Stark ladder model [

77] we have there about 50% of the norm propagating to the high energy modes, counting from the initial state location (and about 50% of norm moving to the low energy modes). Thus there can be a certain similarity between the Stark model [

77] and our fiber NSE model (

3). However, in [

77] the coupling matrix elements

V are approximately comparable for all modes (centered within a localization length

), independently of m values, while for the fiber case the dependence of

V on

m requires further analysis. Indeed, at high

(or

m) values the linear modes become more and more oscillating (see

Figure 3) and thus we may expect that a number of effective components

is growing with

and thus couplings

V are decreasing. A simple estimate based on the results for rough billiards [

78] would give

and thus

, but this expectation requires separate verification. If

V decreases with

then effective nonlinearity also decreases and at some high energies

an effective nonlinearity

becomes below a chaos border that leads us to a bounded scenario with only finite number of effectively populated modes. At present we cannot present firm arguments in favor of bounded scenario of excitation to high energies or unbounded one.

Also the results presented in [

26] for RMT with growing energy diagonal term (see SupMat Figure S14 in [

26]) show that even in a system with

modes the thermal RJ distribution is reached only at such high times as

(

is not enough). Such times cannot be reached in numerical simulations of fiber NSE (

3). Such high times are also out of reach with fiber experiments.

For initial states with vortexes our results in

Figure 24,

Figure 25,

Figure 26 show that for

a vortex state is destroyed and we expect that the dynamical RJ thermalization takes place at long times which however are difficult to reach in numerical simulations due to high life time of vortex. For the superfluid phase at

the question about vortex life time remains open.

11. Discussion and Conclusion

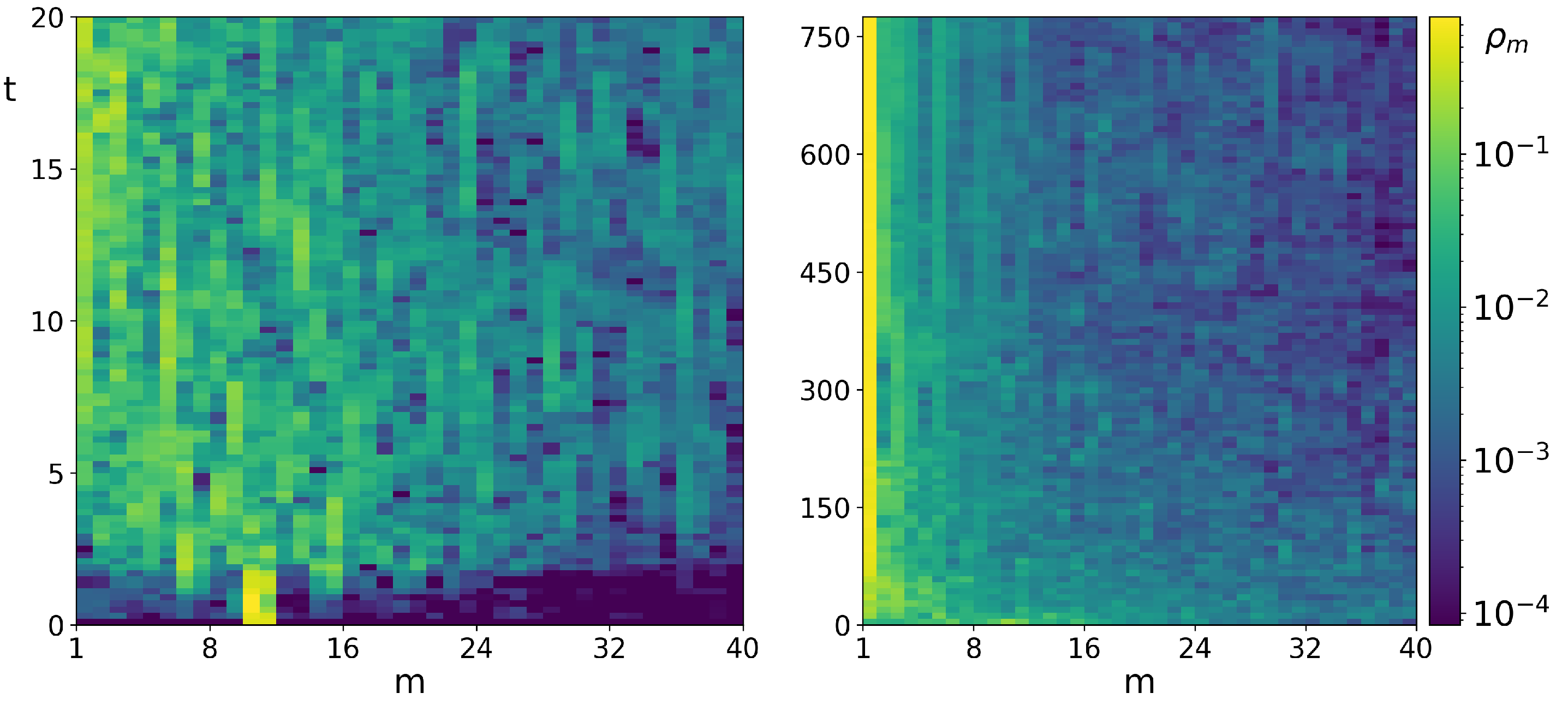

Our numerical and analytical studies of the NSE fiber light fluid dynamics in a chaotic D-shape billiard show that it is characterized by various unusual and rich phenomena. Above the chaos border at

the dynamical thermalization leads to the RJ thermal distribution (

2) with a formation of the RJ condensate in the ground state of linear system which fraction has about 80-90% of total probability. Certain similarities between RJ and Froöhlich condensates are discussed. We show that at

near the ground state there is a self-consistent state with a certain island of stable motion around it. In contrast to the Boltzmann H-theorem [

8,

11,

48] in the chaotic regime the entropy time evolution

is characterized by initial increase at short times and later relaxation from its maximal value to a significantly smaller value on long times in the steady-state regime that is explained by the formation of RJ condensate. We point that the presence of two integrals of motion, energy and norm, is at the origin of such a difference from the H-theorem formulated for systems with only one energy integral of motion. In absence of nonlinearity our system belongs to the systems of quantum chaos, thus having many features as in the Random Matrix Theory. On these grounds we argue that the dynamical thermalization induced by nonlinearity represents a generic features of such thermalization similar to those discussed for nonlinear perturbation of Random Matrix theory in [

26]. We also note that even if the phenomenon of RJ condensation in nonlinear systems has been discussed for multi-mode fibers [

58,

59,

60,

61] its origin was not associated with the emergence of dynamical chaos above a certain chaos border below which the RJ thermalization and RJ condensate are absent and dynamics is quasi-integrable as in the KAM theory. We attribute the so-called self-cleaning phenomenon observed in multi-mode optical fibers [

1,

2] to the formation of RJ condensate induced by dynamical thermalization and chaos. A pictorial image of time development of dynamical thermalization and RJ condensate formation is shown in

Figure 27.

In addition to dynamical thermalization at certain conditions the focusing fiber NSE (

3) at

can have the regime with wave collapse which in contrast to the case of open space [

45,

46] can happen even at relatively high positive energies (see

Figure 19,

Figure 20). In such regime there is a nontrivial interplay between chaotic component and wave collapse. However, the RJ condensate emerging due to dynamical thermalization does not lead to the collapse formation.

We also show that for the defocusing fiber NSE (

3) there are long living excitations in the form of vortexes which finally are expected to relax to the RJ thermal state for nonlinearity

. However, for a strong nonlinearity

the vortex life time is strikingly increased corresponding to the transition to the superfluid phase of light fluid.

We hope that these interesting and generic phenomena described here can be studied experimentally with multi-mode fibers similar to those of [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] (namely with a quantum chaos fiber cross-section, e.g. D-shape as in

Figure 1). In fact certain studies of D-shape fiber have been reported recently in [

37] but without discussion of dynamical thermalization. Also the quantum fluid experiments with laser beam propagating in a nonlinear medium formed by atomic vapor, like in [

62], can be used to test interplay of nonlinearity, quantum chaos and dynamical thermalization.

Figure 1.

Geometry of the D-shape billiard with a straight cut of a circle with length of a perpendicular to the cut being where the diameter of the circle is , here is given by the equation . In our studies we use , .

Figure 1.

Geometry of the D-shape billiard with a straight cut of a circle with length of a perpendicular to the cut being where the diameter of the circle is , here is given by the equation . In our studies we use , .

Figure 2.

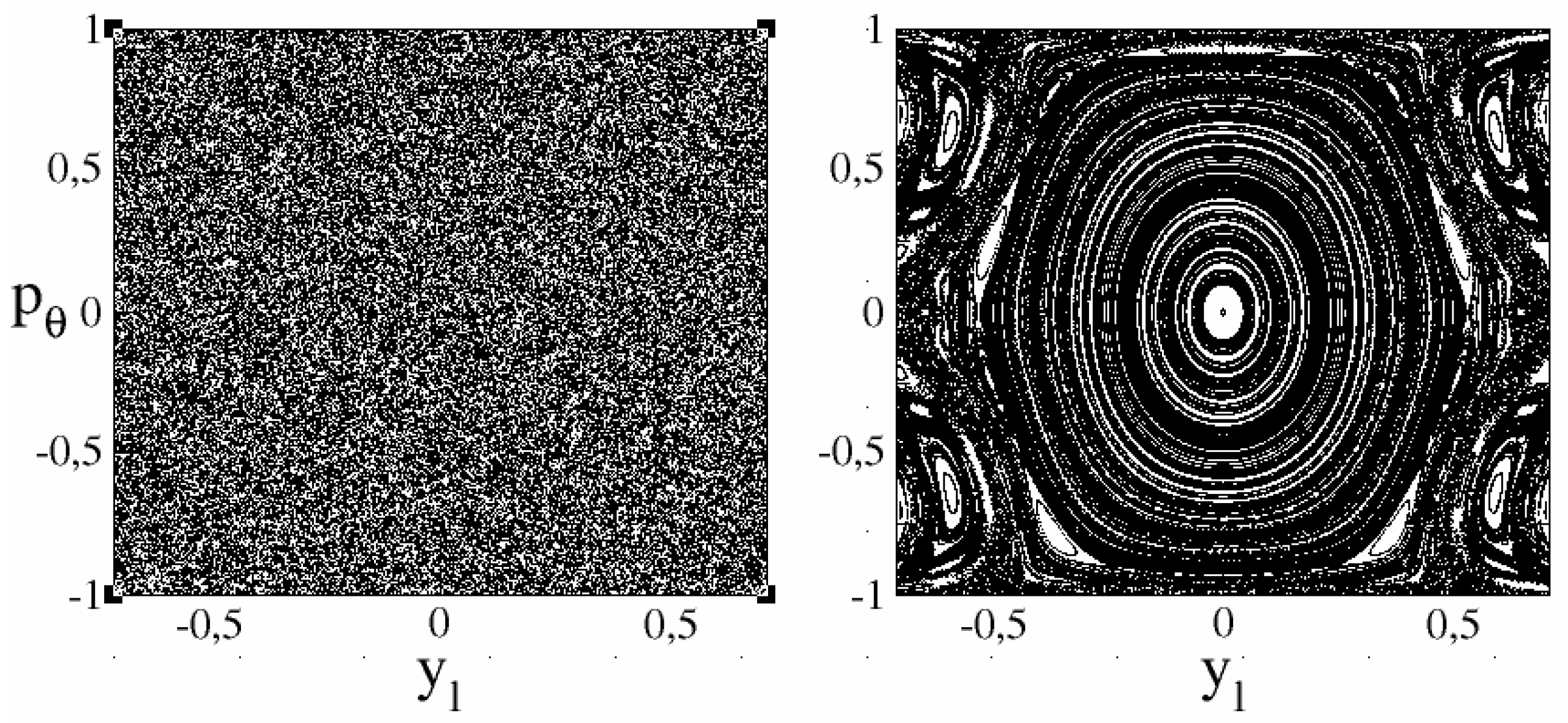

Poincaré section is shown for 1 trajectory for time up to with the hard chaos case (left panel), and for 361 trajectories of 1000 points for each trajectory for the case of divided phase space with large integrable islands (right panel) with large integrable component. Here, are conjugate variables, where is the position at which the collision with the vertical line occurs. The term is the tangential component of the particle’s momentum, with being the angle of incidence in the collision.

Figure 2.

Poincaré section is shown for 1 trajectory for time up to with the hard chaos case (left panel), and for 361 trajectories of 1000 points for each trajectory for the case of divided phase space with large integrable islands (right panel) with large integrable component. Here, are conjugate variables, where is the position at which the collision with the vertical line occurs. The term is the tangential component of the particle’s momentum, with being the angle of incidence in the collision.

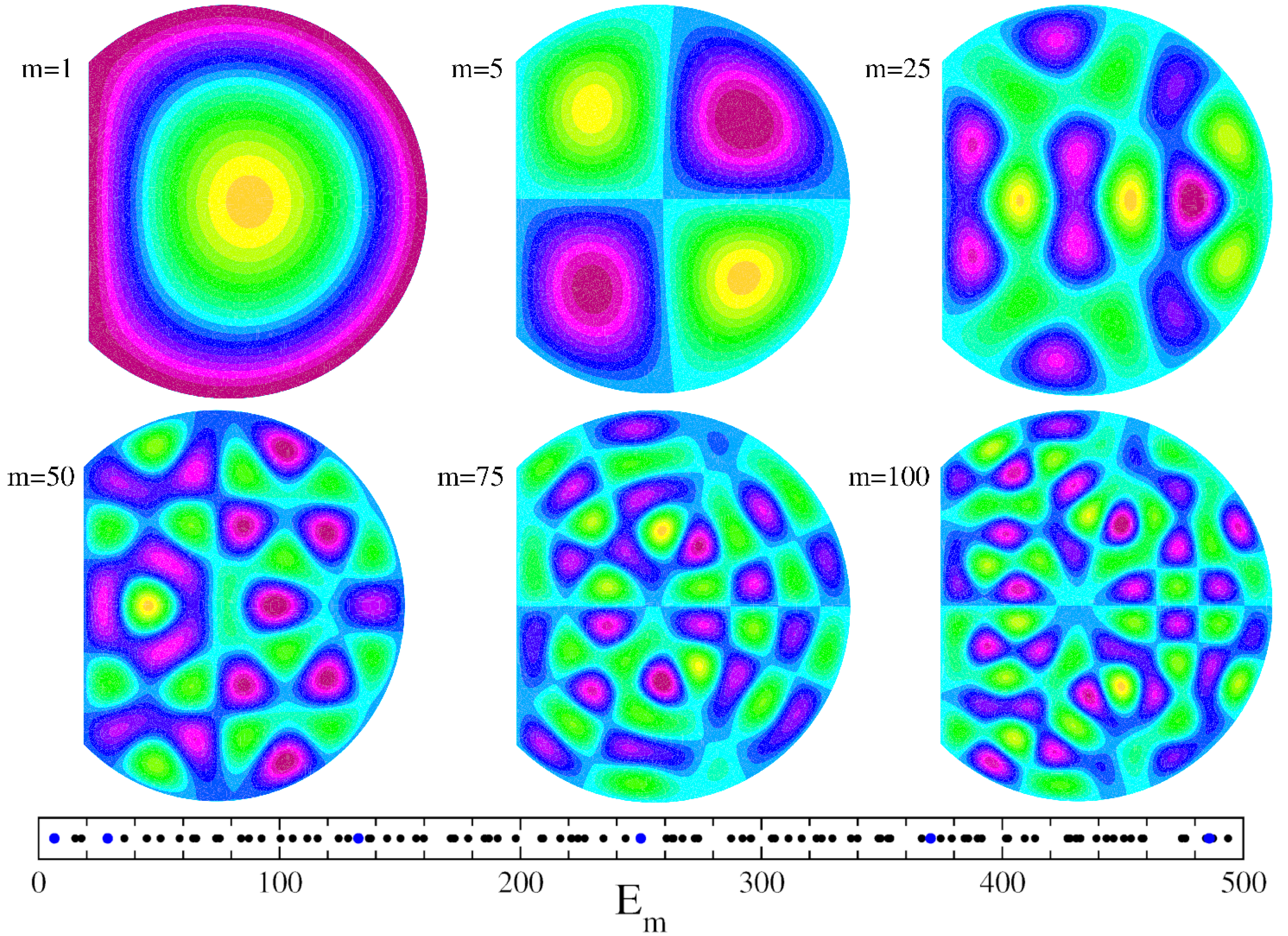

Figure 3.

Bottom panel shows first energy values for both parities with respect to the y-axis (odd and even); six top panels show the amplitude of real eigenfunctions for (marked by blue points of bottom energy panel). The color scale of wave functions a includes negative values for and ranges from minimum (red) to maximum (yellow), passing through blue, light blue, and green. For at red corresponds to zero for the ground state () while light blue represents zero for the other states.

Figure 3.

Bottom panel shows first energy values for both parities with respect to the y-axis (odd and even); six top panels show the amplitude of real eigenfunctions for (marked by blue points of bottom energy panel). The color scale of wave functions a includes negative values for and ranges from minimum (red) to maximum (yellow), passing through blue, light blue, and green. For at red corresponds to zero for the ground state () while light blue represents zero for the other states.

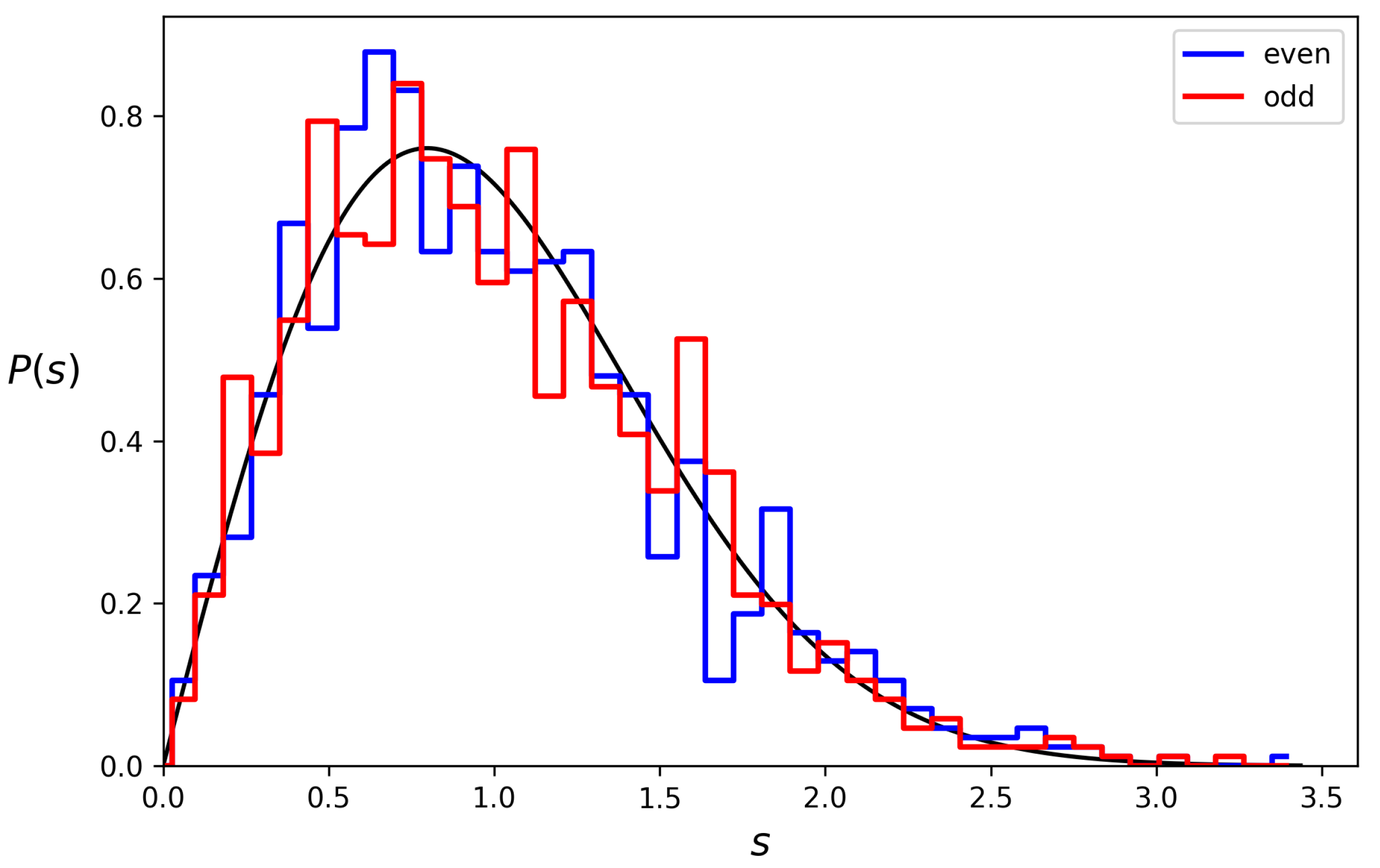

Figure 4.

Histogram for the level spacing statistical distribution is shown by blue and red bins for even and odd parity respectively. This distribution is calculated for both even and odd parity eigenstates. The theoretical Wigner surmise is shown by a full curve. Here, s is the energy level spacing rescaled by the average level spacing for fixed parity states. The histogram is obtained with the lowest 2000 energy levels.

Figure 4.

Histogram for the level spacing statistical distribution is shown by blue and red bins for even and odd parity respectively. This distribution is calculated for both even and odd parity eigenstates. The theoretical Wigner surmise is shown by a full curve. Here, s is the energy level spacing rescaled by the average level spacing for fixed parity states. The histogram is obtained with the lowest 2000 energy levels.

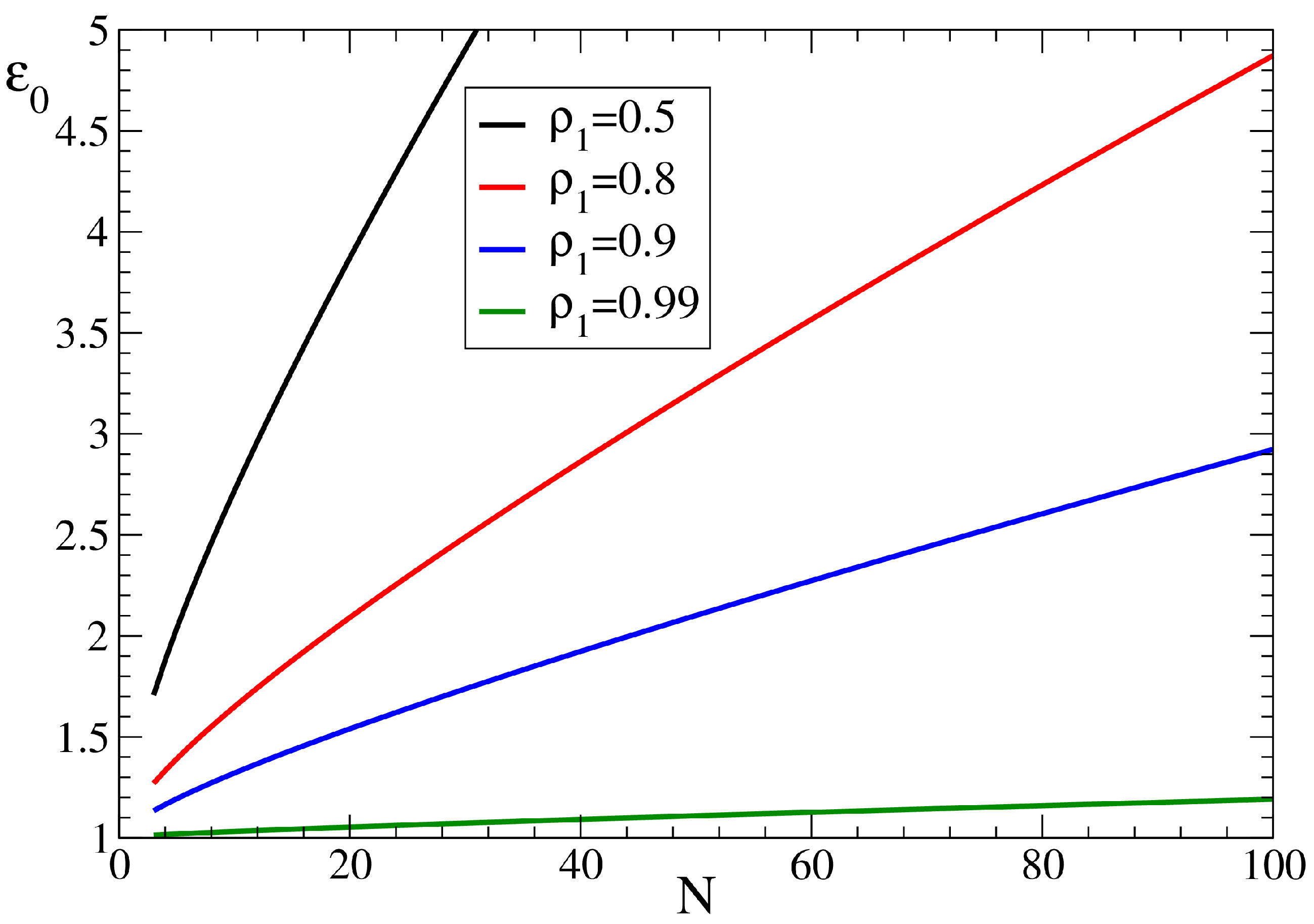

Figure 5.

Dependence of initially energy on total number of levels in the RJS model with , , for fixed probability of condensate at the ground state with .

Figure 5.

Dependence of initially energy on total number of levels in the RJS model with , , for fixed probability of condensate at the ground state with .

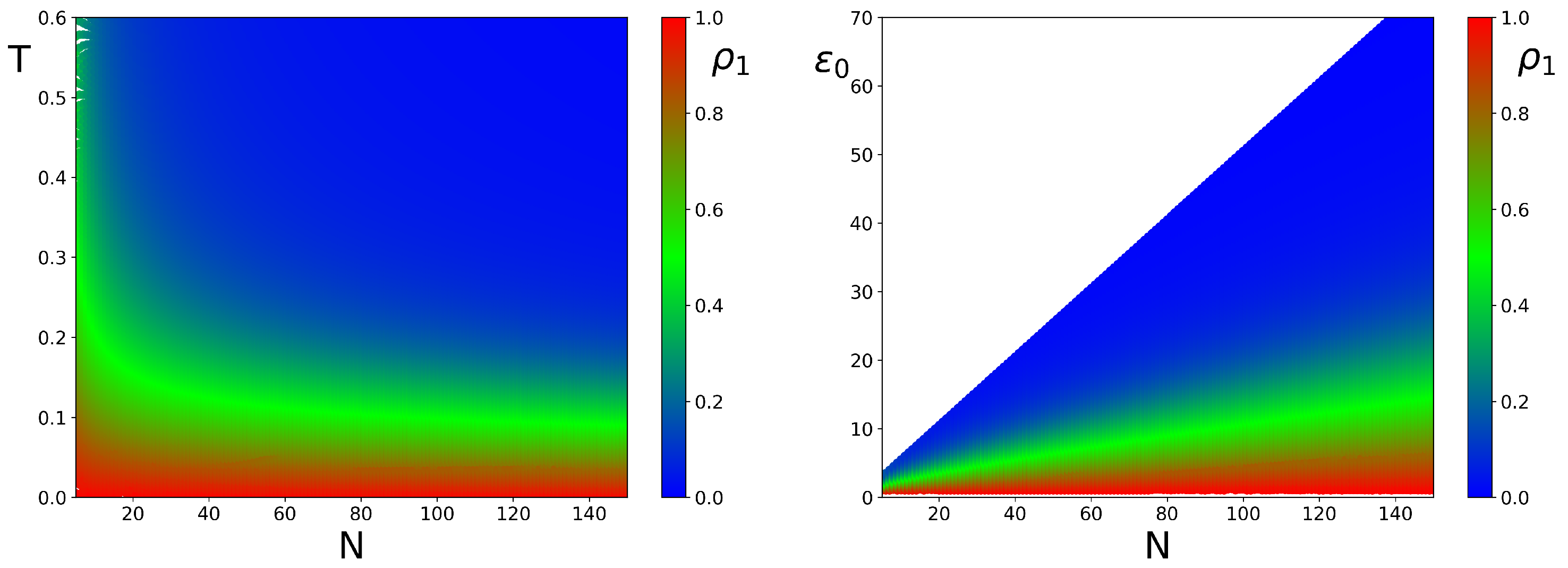

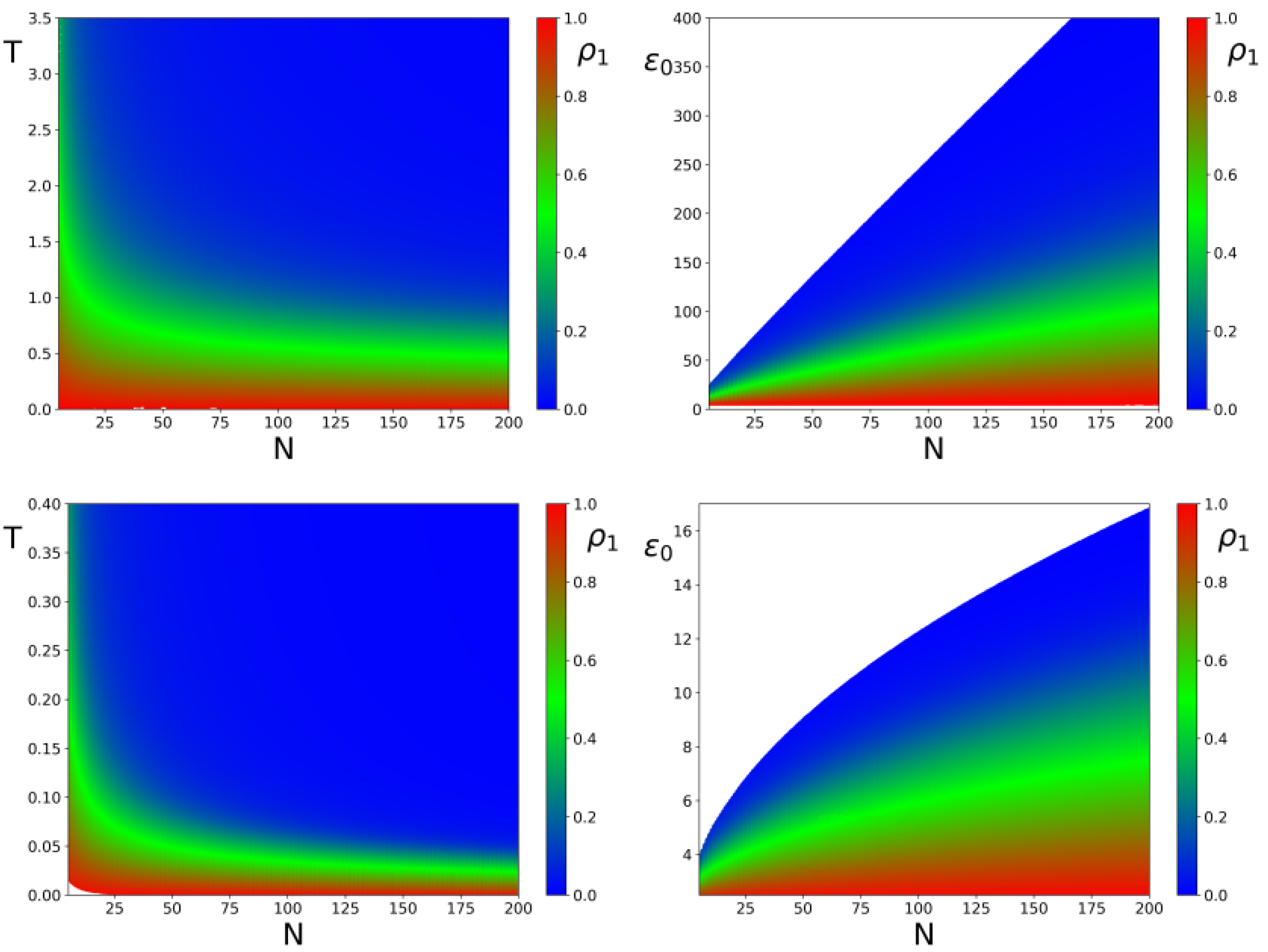

Figure 6.

Color map of condensate probability

at corresponding system temperature

T and number of system modes

N (left panel); right panel shows the same

as in left panel but in the plane

;

obtained in the frame of RJ thermal distribution (

2).

Figure 6.

Color map of condensate probability

at corresponding system temperature

T and number of system modes

N (left panel); right panel shows the same

as in left panel but in the plane

;

obtained in the frame of RJ thermal distribution (

2).

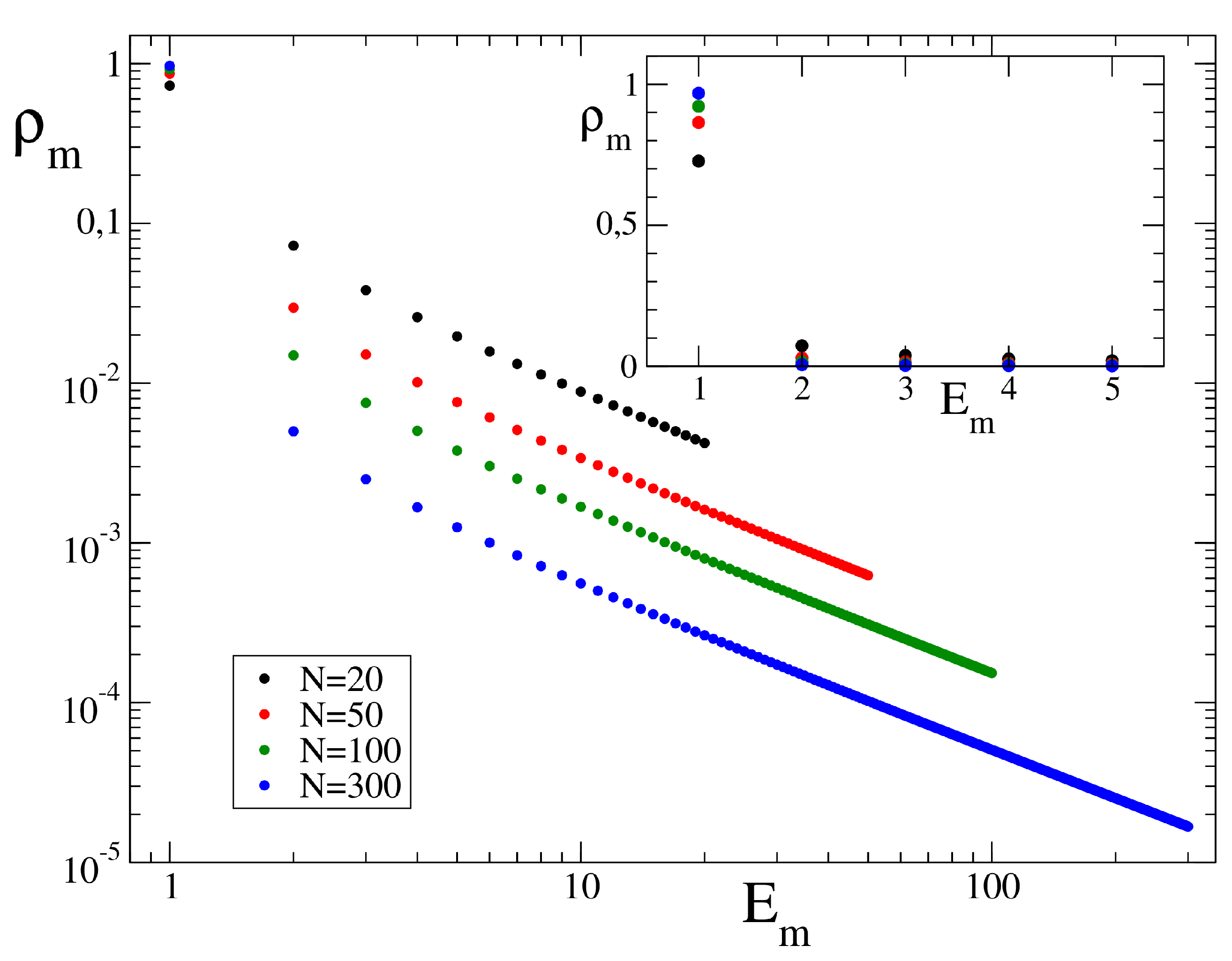

Figure 7.

Thermal RJ distribution

(

2) for various mode energies

at

and initial total energy

;

; data is presented in log-log scale.

Figure 7.

Thermal RJ distribution

(

2) for various mode energies

at

and initial total energy

;

; data is presented in log-log scale.

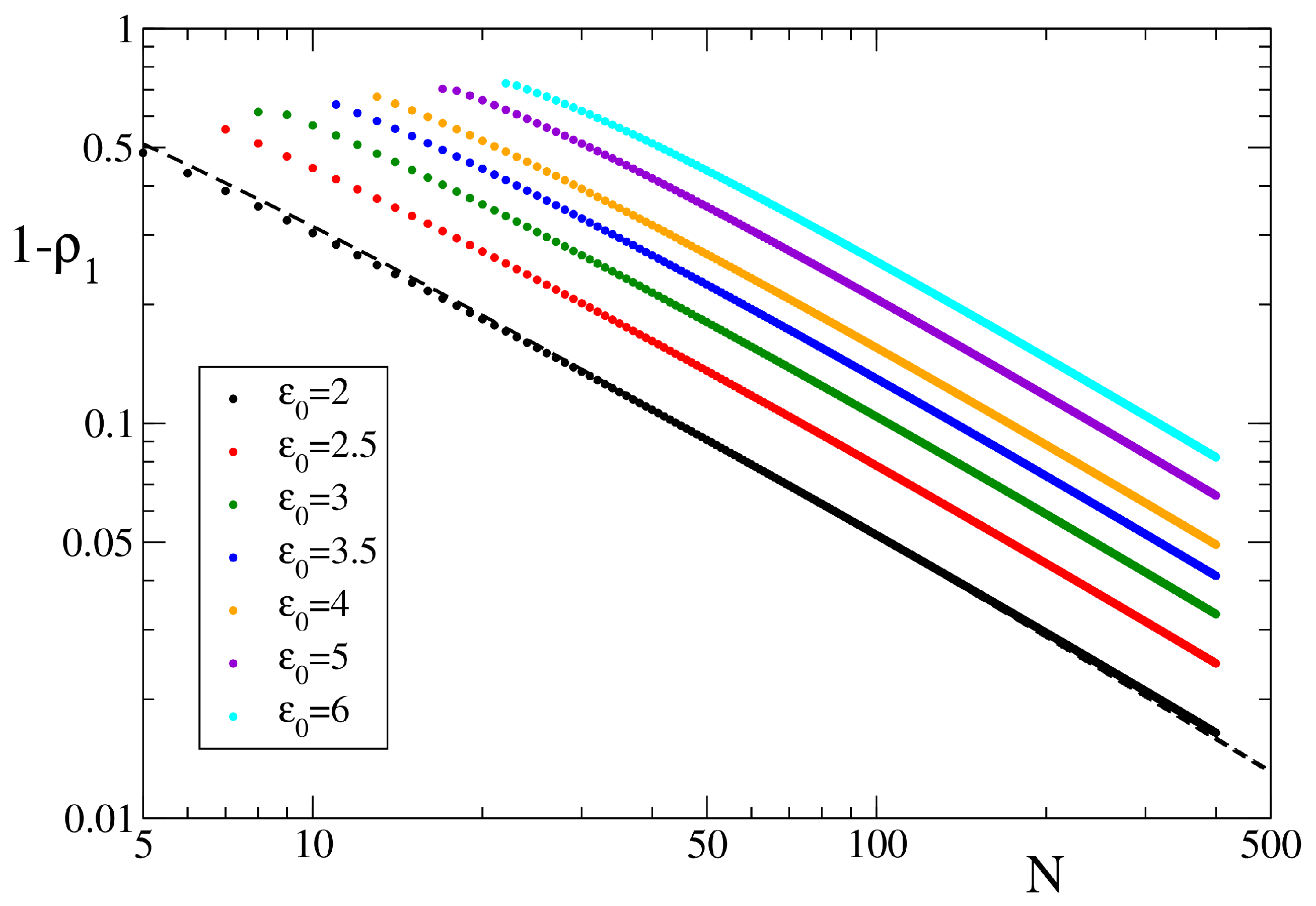

Figure 8.

Dependence of the non-condensate probability, , on the total number of modes, N, at a fixed total energy of . Here, represents the ground state population. The dashed curve shows the analytical theory given by the average Gumbel distribution with , for where is the Euler-Mascheroni constant (see text).

Figure 8.

Dependence of the non-condensate probability, , on the total number of modes, N, at a fixed total energy of . Here, represents the ground state population. The dashed curve shows the analytical theory given by the average Gumbel distribution with , for where is the Euler-Mascheroni constant (see text).

Figure 9.

Color plot of condensate probability

. The left panels show plots of

T vs.

N, while the right panels show the distributions of

vs.

N. The top panels display the case of the D-shape billiard, with energies

of the D-shape fiber described in

Section 2. The bottom panels show the corresponding plots for the Sinai oscillator, with energies

from [

70].

Figure 9.

Color plot of condensate probability

. The left panels show plots of

T vs.

N, while the right panels show the distributions of

vs.

N. The top panels display the case of the D-shape billiard, with energies

of the D-shape fiber described in

Section 2. The bottom panels show the corresponding plots for the Sinai oscillator, with energies

from [

70].

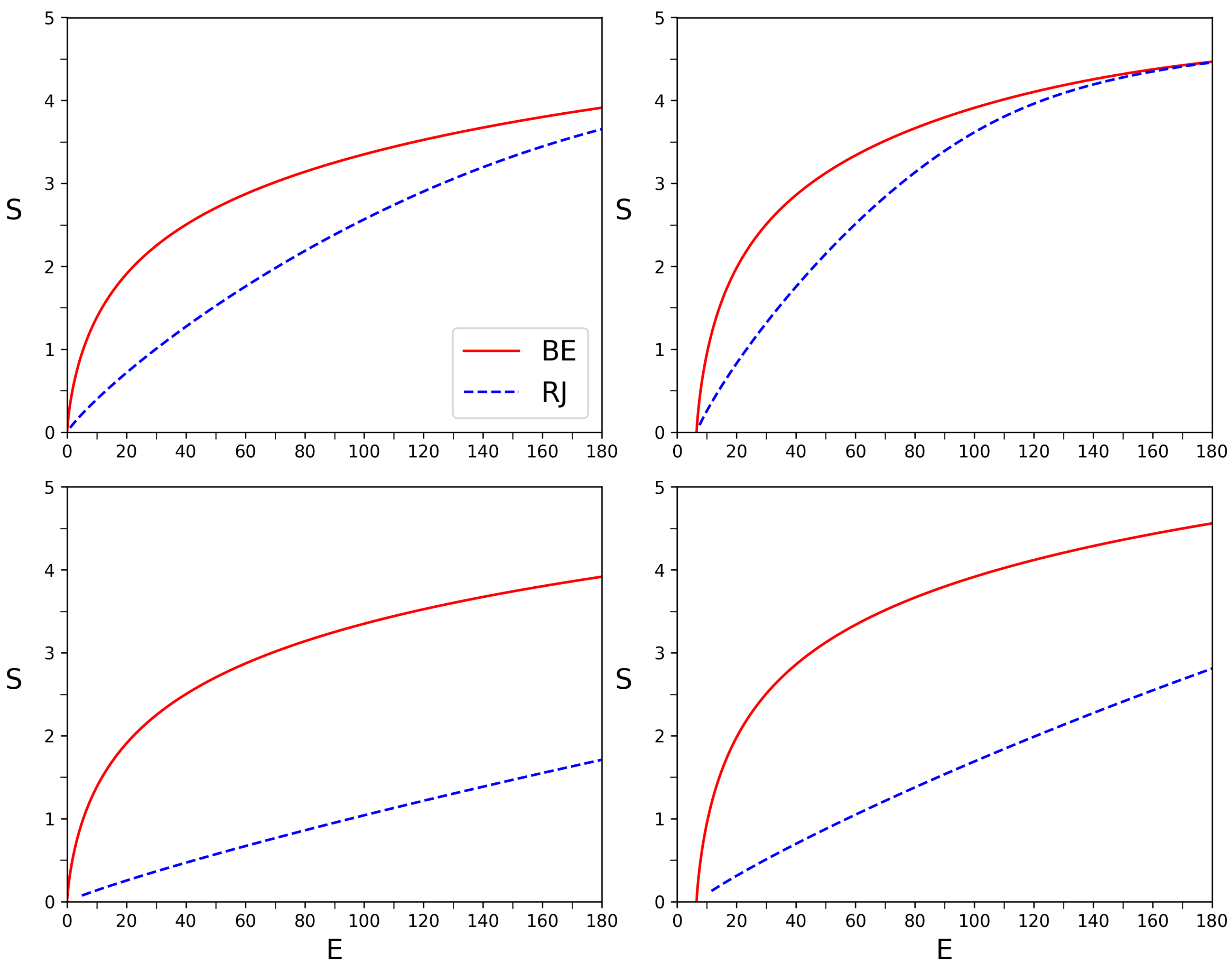

Figure 10.

Entropy (

S) as a function of energy (

E) for Bose-Einstein (BE) distributions (red solid line, Eq.

1) and Rayleigh-Jeans (RJ) distributions (blue dashed line, Eq.

2). The left panels show the simple model with equidistant energy levels, while the right panels are for energy states given by the

D-billiard. The top panels show the case of

states, and the bottom panels for

states. For the D-shape billiard the lowest energies are

.

Figure 10.

Entropy (

S) as a function of energy (

E) for Bose-Einstein (BE) distributions (red solid line, Eq.

1) and Rayleigh-Jeans (RJ) distributions (blue dashed line, Eq.

2). The left panels show the simple model with equidistant energy levels, while the right panels are for energy states given by the

D-billiard. The top panels show the case of

states, and the bottom panels for

states. For the D-shape billiard the lowest energies are

.

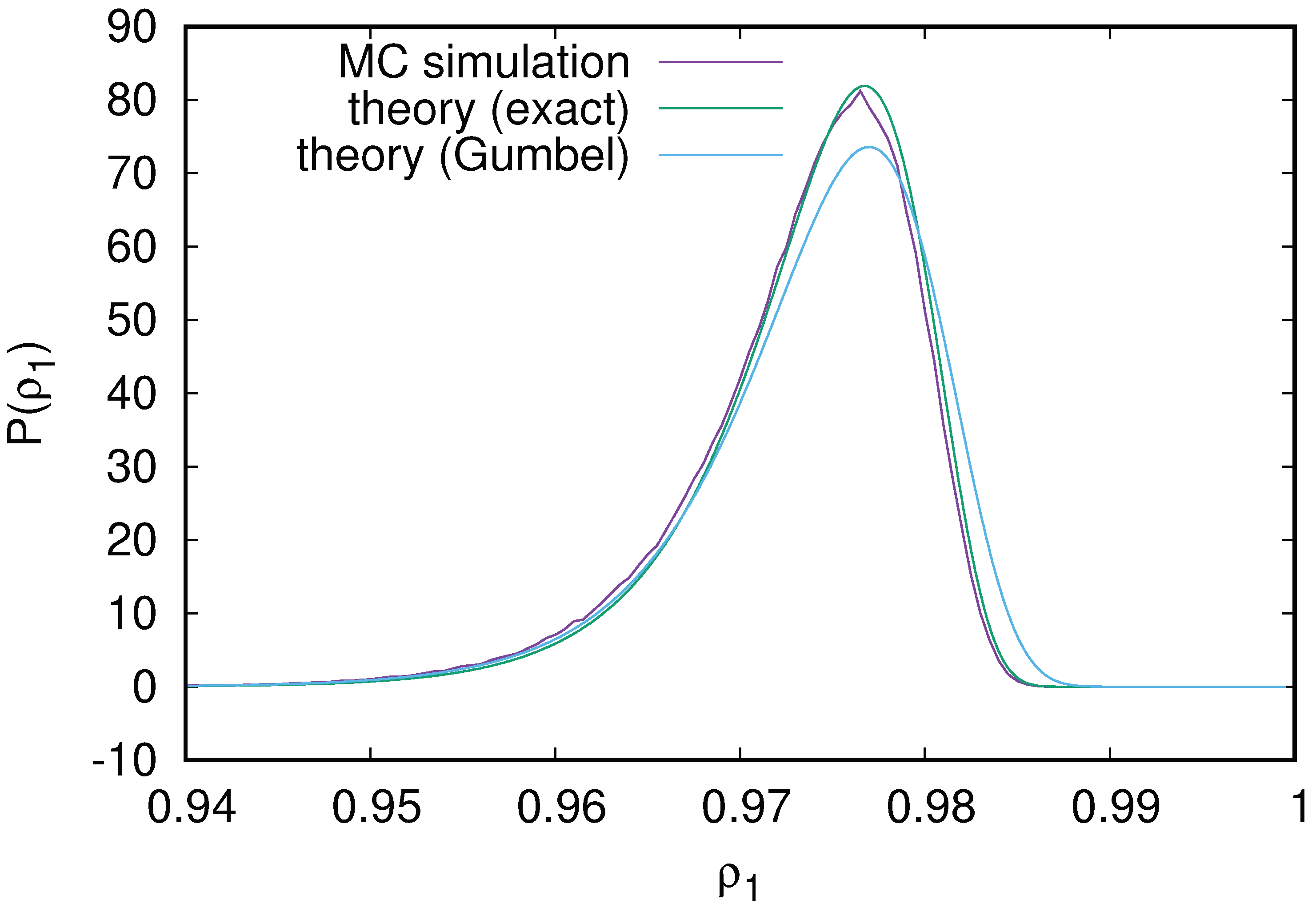

Figure 11.

Probability distribution

for fluctuations of RJ condensate population at the ground state

for the RJS model of

N equidistant energy levels in RJ thermal distribution (

2) with energy and norm conservation, comparing Monte Carlo simulations, exact analytical expression Eq. (

13) and asymptotic Gumbel distribution Eq. (

16).

Figure 11.

Probability distribution

for fluctuations of RJ condensate population at the ground state

for the RJS model of

N equidistant energy levels in RJ thermal distribution (

2) with energy and norm conservation, comparing Monte Carlo simulations, exact analytical expression Eq. (

13) and asymptotic Gumbel distribution Eq. (

16).

Figure 12.

Time dependence of the ground state probability shown up to for various initial states. The color of each curve corresponds to the initial total state energy, as indicated in the legend; the initial states are for (from minimal to maximal total energies E given in the figure panel); the plot shows a temporal average over time interval ; here . RJ and BE ansatz are shown for by the black and red dashed lines respectively for and ; the values of parameters obtained for both ansatz are , for RJ and , for BE.

Figure 12.

Time dependence of the ground state probability shown up to for various initial states. The color of each curve corresponds to the initial total state energy, as indicated in the legend; the initial states are for (from minimal to maximal total energies E given in the figure panel); the plot shows a temporal average over time interval ; here . RJ and BE ansatz are shown for by the black and red dashed lines respectively for and ; the values of parameters obtained for both ansatz are , for RJ and , for BE.

Figure 13.

Probability at eigenstates

(

) as a function of linear eigenstate energy

for different initial states and averaged over the time interval

to

; other parameters are as in

Figure 12. Colors correspond to the same initial states as in

Figure 12; RJ and BE ansatz parameters are shown by dashed curves described in

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Probability at eigenstates

(

) as a function of linear eigenstate energy

for different initial states and averaged over the time interval

to

; other parameters are as in

Figure 12. Colors correspond to the same initial states as in

Figure 12; RJ and BE ansatz parameters are shown by dashed curves described in

Figure 12.

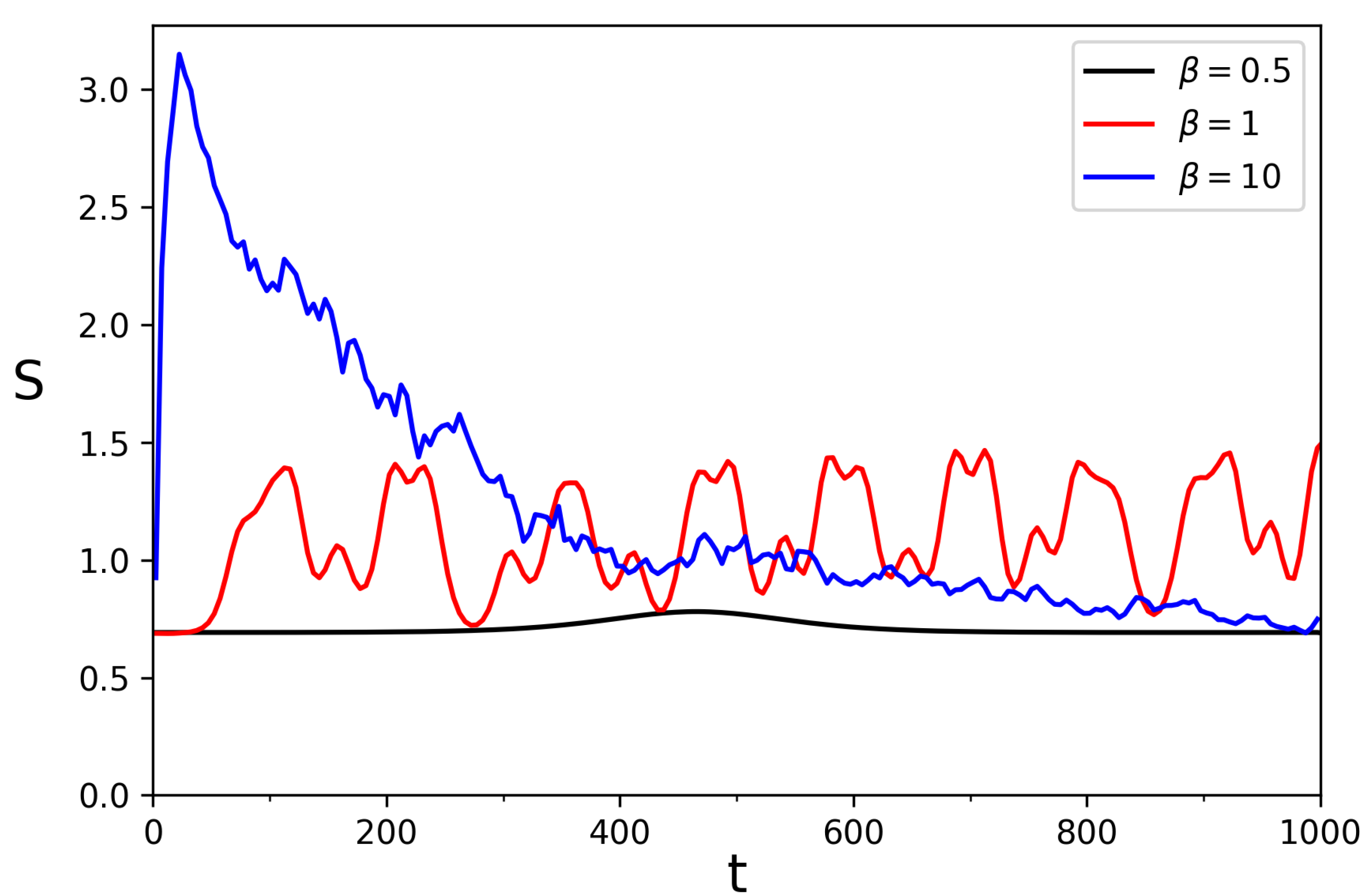

Figure 14.

Dependence of entropy

S on time

t for

and other parameters as in

Figure 12; values of

S are averaged in the time window

to reduce the fluctuations; short time behavior of

is shown in Appendix

Figure A2.

Figure 14.

Dependence of entropy

S on time

t for

and other parameters as in

Figure 12; values of

S are averaged in the time window

to reduce the fluctuations; short time behavior of

is shown in Appendix

Figure A2.

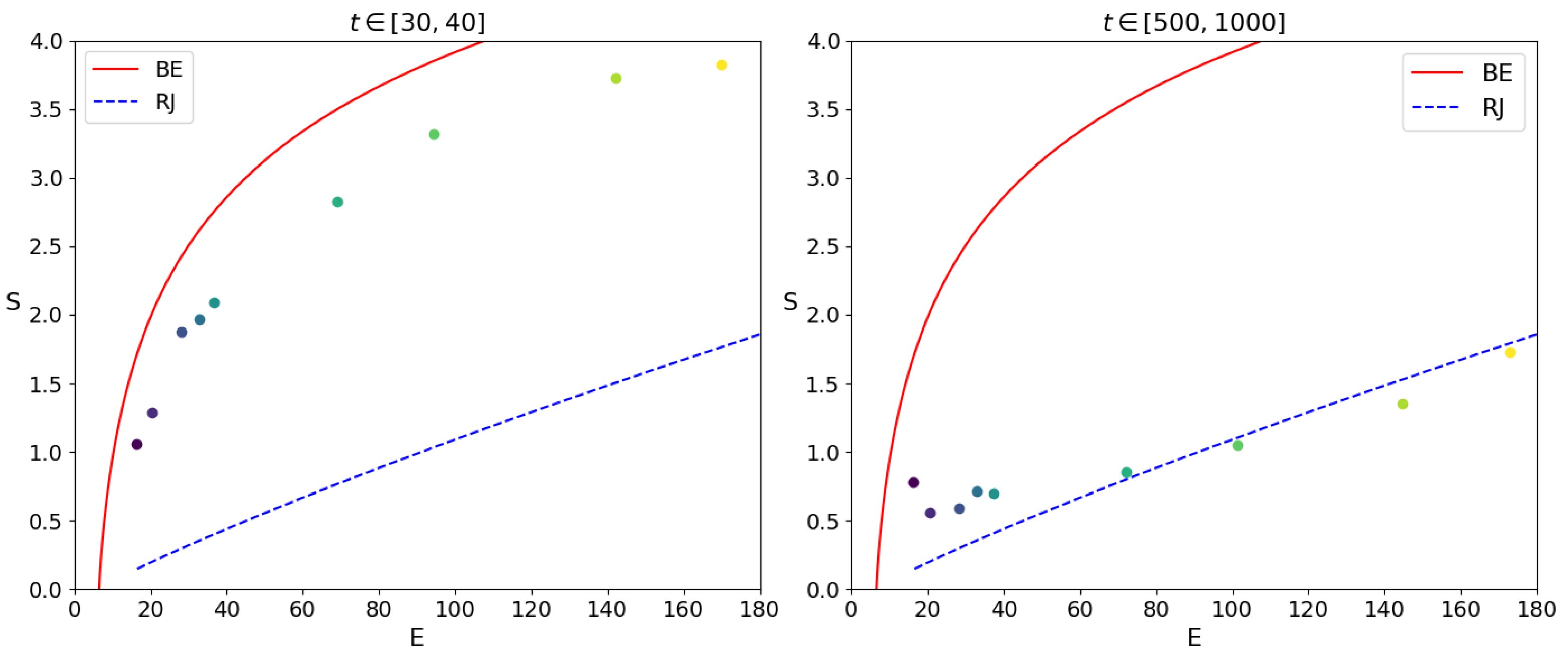

Figure 15.

Entropy

S vs energy

E are shown by points for the initial states of

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. The left panel displays the time average for times between 30 and 50, while the right panel shows the average for times between 500 and 1000; here as in

Figure 12E is the total energy. In both panels, the curves are shown for the Bose-Einstein (BE) and Rayleigh-Jeans (RJ) distributions for the billiard with

.

Figure 15.

Entropy

S vs energy

E are shown by points for the initial states of

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. The left panel displays the time average for times between 30 and 50, while the right panel shows the average for times between 500 and 1000; here as in

Figure 12E is the total energy. In both panels, the curves are shown for the Bose-Einstein (BE) and Rayleigh-Jeans (RJ) distributions for the billiard with

.

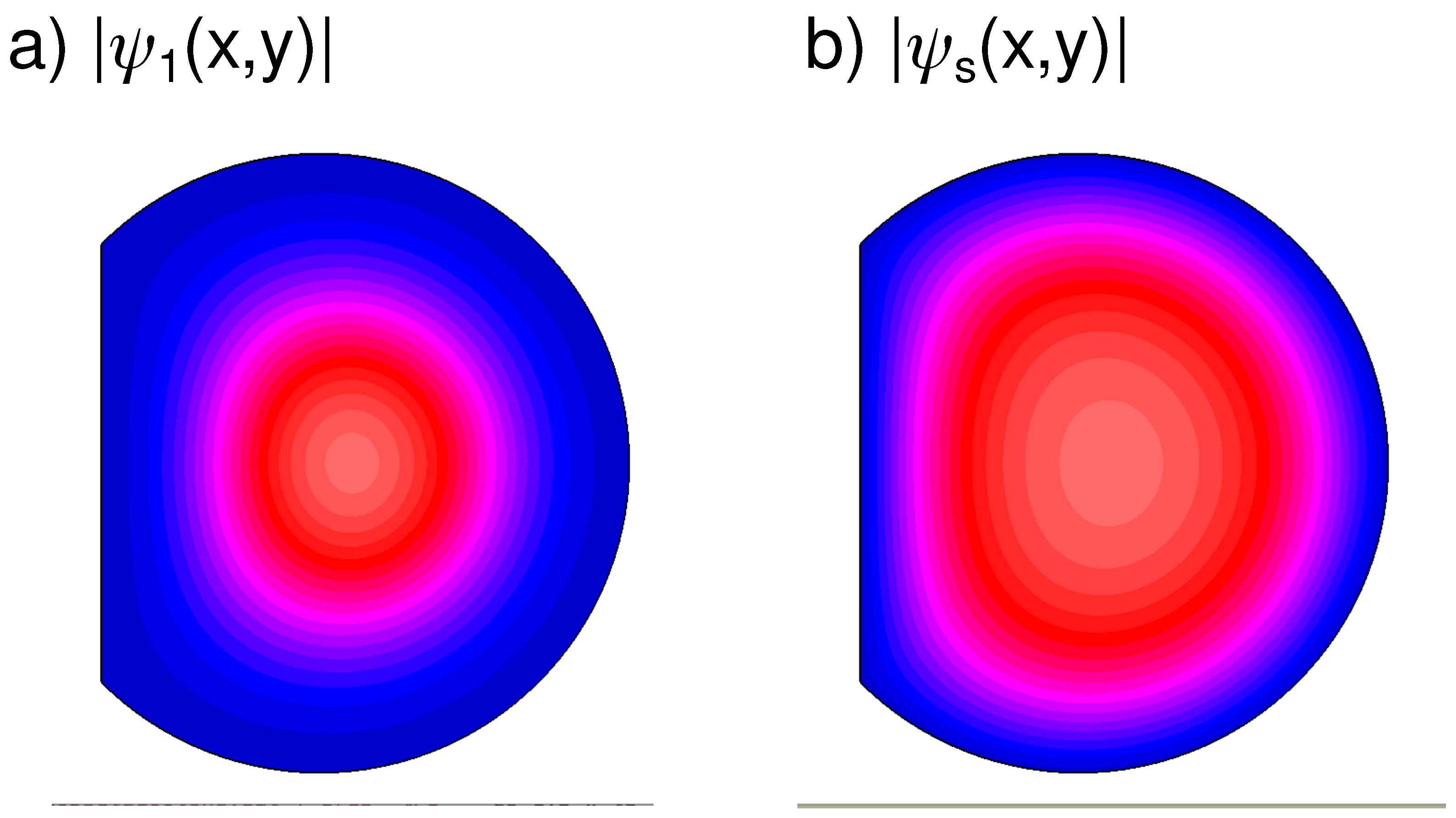

Figure 16.

Left panel: amplitude of wave function of the ground state

at

; right panel: amplitude of the self-consistent solution

of the NSE (

3) at

; overlap probability between these states is

. Amplitude is changing from zero (blue color) to high value (red color) and maximal value (light red in the center); wave functions are normalized to unity.

Figure 16.

Left panel: amplitude of wave function of the ground state

at

; right panel: amplitude of the self-consistent solution

of the NSE (

3) at

; overlap probability between these states is

. Amplitude is changing from zero (blue color) to high value (red color) and maximal value (light red in the center); wave functions are normalized to unity.

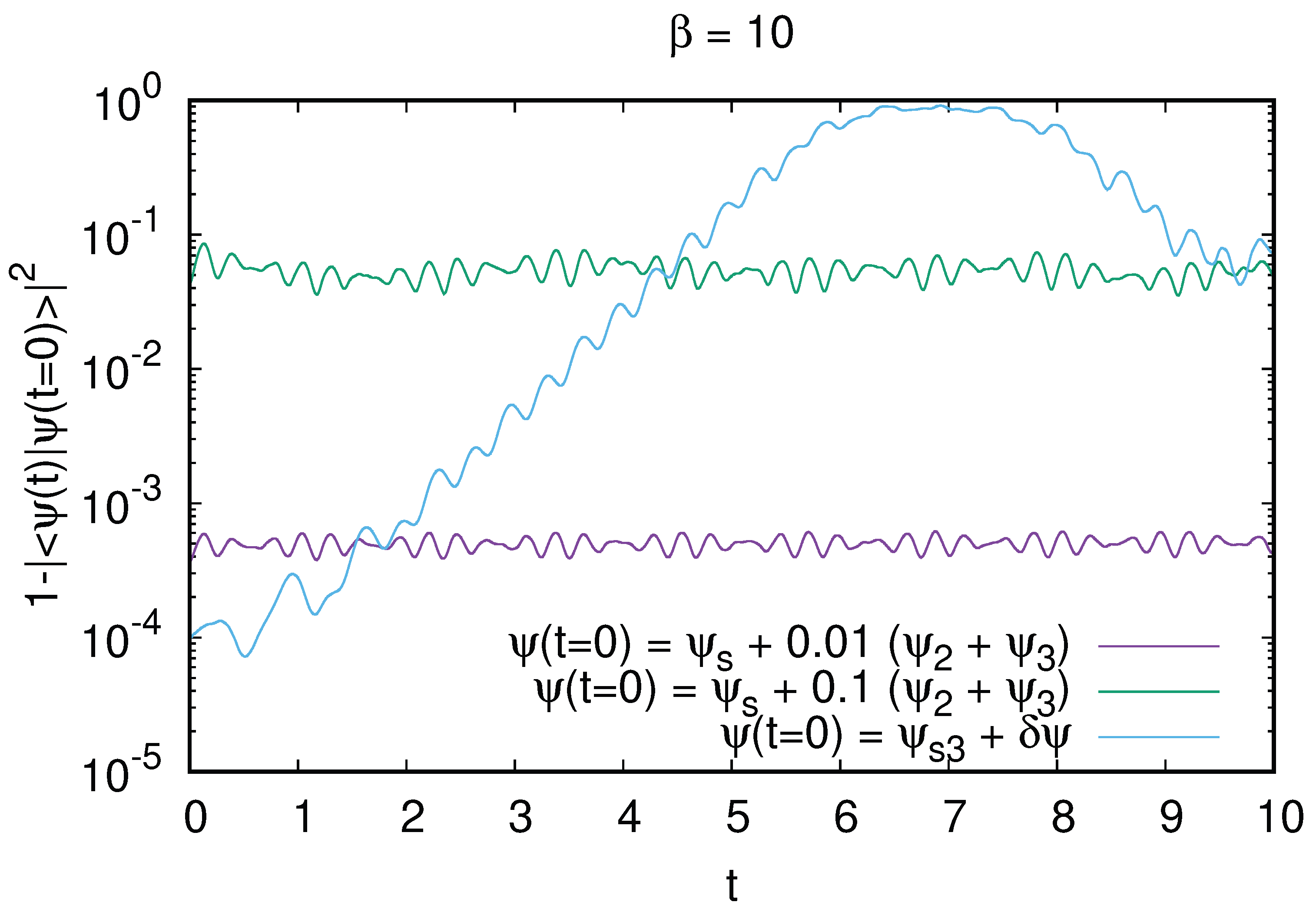

Figure 17.

Stability of self-consistent states obtained near the ground state and first excited state: the error of initial deviation remains approximately constant in time t showing that the state is table near a vicinity of the ground state while in a vicinity of the first excited state the error grows exponentially with time showing that the corresponding self-consistent state is unstable.

Figure 17.

Stability of self-consistent states obtained near the ground state and first excited state: the error of initial deviation remains approximately constant in time t showing that the state is table near a vicinity of the ground state while in a vicinity of the first excited state the error grows exponentially with time showing that the corresponding self-consistent state is unstable.

Figure 18.

Entropy S dependence on time for the initial state at and (values of S are averaged over a time window ).

Figure 18.

Entropy S dependence on time for the initial state at and (values of S are averaged over a time window ).

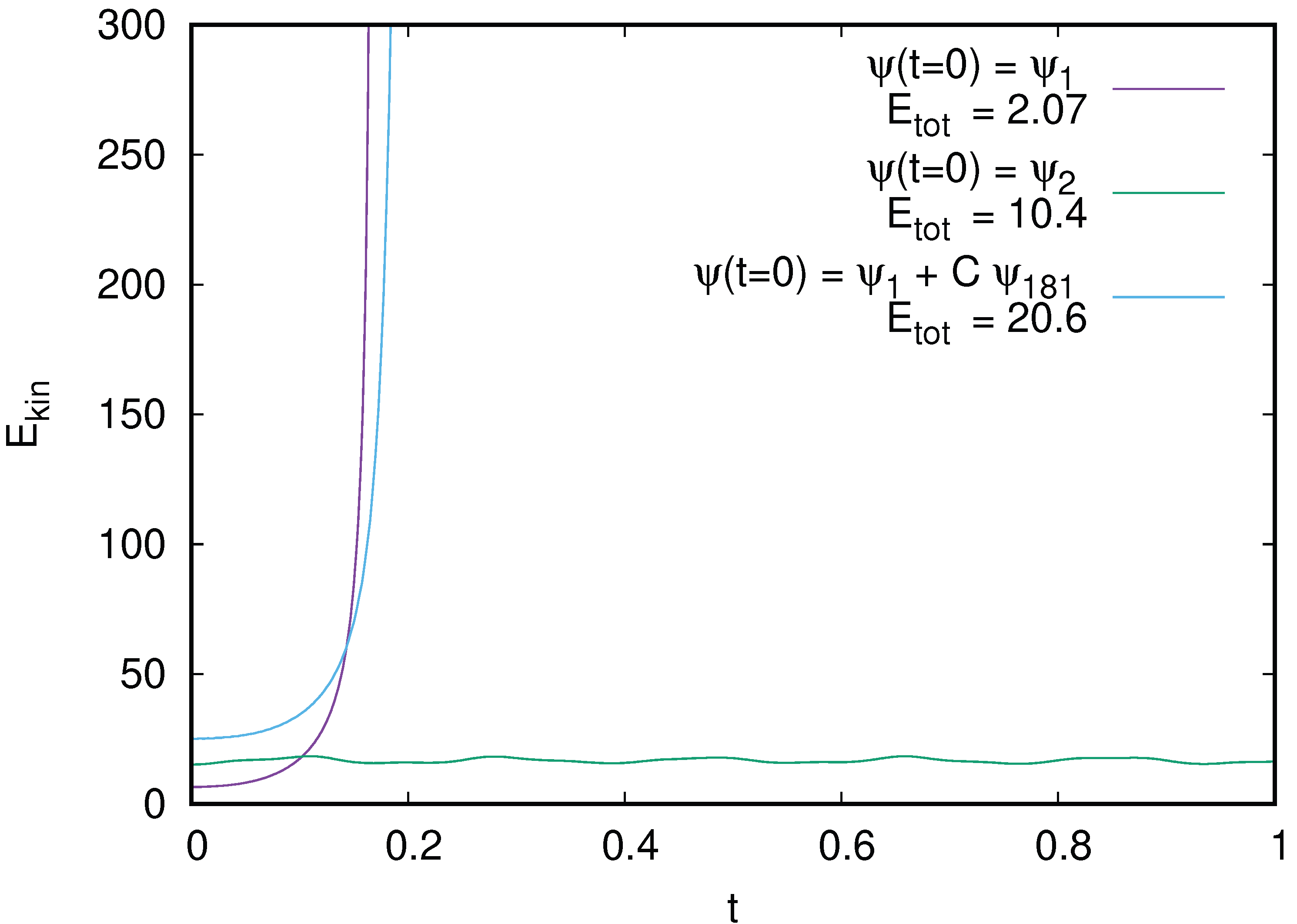

Figure 19.

Dependence of kinetic energy

on time

t in the NSE (

3) at

; the initial state at

is the linear ground state

with the initial total energy

(magenta curve), here the collapse takes place at

with the divergence of

; the initial state is given by a linear combination of ground state

and excited state at

with

,

,

and collapse happens at

; the initial state is taken as the first linear excited state

at the initial total energy

(green curve) for which there is no collapse and only oscillations of

with time

t. Here FREEFEM size is

, integration time step

, the relative accuracy of norm conservation is typically

, with an increase up to maximal

at specific time moments, and a relative accuracy of total energy conservation is typically

with maximum being

.

Figure 19.

Dependence of kinetic energy

on time

t in the NSE (

3) at

; the initial state at

is the linear ground state

with the initial total energy

(magenta curve), here the collapse takes place at

with the divergence of

; the initial state is given by a linear combination of ground state

and excited state at

with

,

,

and collapse happens at

; the initial state is taken as the first linear excited state

at the initial total energy

(green curve) for which there is no collapse and only oscillations of

with time

t. Here FREEFEM size is

, integration time step

, the relative accuracy of norm conservation is typically

, with an increase up to maximal

at specific time moments, and a relative accuracy of total energy conservation is typically

with maximum being

.

Figure 20.

Top panel: oscillating dependence of kinetic energy

on time

t (total energy

is constant) for

and the initial state is given by a linear combination of ground state

and excited state at

with

and

,

,

: no collapse (compare with collapse at

in

Figure 19). Bottom panel: for the case

in the top panel we show the time dependence of the main part of probability in the eigenstates

n of instantenious potential

given by

; there are diabatic transitions between

n-levels, shown by color bar, see text for details. Numerical integration parameters are as in

Figure 19.

Figure 20.

Top panel: oscillating dependence of kinetic energy

on time

t (total energy

is constant) for

and the initial state is given by a linear combination of ground state

and excited state at

with

and

,

,

: no collapse (compare with collapse at

in

Figure 19). Bottom panel: for the case

in the top panel we show the time dependence of the main part of probability in the eigenstates

n of instantenious potential

given by

; there are diabatic transitions between

n-levels, shown by color bar, see text for details. Numerical integration parameters are as in

Figure 19.

Figure 21.

Dependence of ground state probability

on time

t as in

Figure 12 but for

and only one initial state

at

; the projection probability on the linear ground state

is shown by blue curve and those on the ground state of instantaneous potential

is shown by green curve; total energy is

; the dashed lines show BE ansatz (red) and RJ ansatz (black) with the same values of

E,

T,

,

N as in

Figure 12.

Figure 21.

Dependence of ground state probability

on time

t as in

Figure 12 but for

and only one initial state

at

; the projection probability on the linear ground state

is shown by blue curve and those on the ground state of instantaneous potential

is shown by green curve; total energy is

; the dashed lines show BE ansatz (red) and RJ ansatz (black) with the same values of

E,

T,

,

N as in

Figure 12.

Figure 22.

Projected probabilities

in the linear eigenstates

and averaged in the time interval

are shown in dependence on linear eigenenergies

at

and initial state as in

Figure 21; dashed curves show the BE and RJ ansatz with same parameters as in

Figure 12.

Figure 22.

Projected probabilities

in the linear eigenstates

and averaged in the time interval

are shown in dependence on linear eigenenergies

at

and initial state as in

Figure 21; dashed curves show the BE and RJ ansatz with same parameters as in

Figure 12.

Figure 23.

Dependence of entropy on time t for (blue curve ) and (red curve) with initial state at ; left/right panels show long/short time behavior.

Figure 23.

Dependence of entropy on time t for (blue curve ) and (red curve) with initial state at ; left/right panels show long/short time behavior.

Figure 24.

Left panel: probability in the linear ground state

and first excited state

(which is relatively close to vortex) as function of time

t for different integration steps

and

with the number of intergration net nodes

and

respectively at

. Right panel: color panels show the wave function amplitude

and its phase

at different moments of time; color scale as in

Figure 16.

Figure 24.

Left panel: probability in the linear ground state

and first excited state

(which is relatively close to vortex) as function of time

t for different integration steps

and

with the number of intergration net nodes

and

respectively at

. Right panel: color panels show the wave function amplitude

and its phase

at different moments of time; color scale as in

Figure 16.

Figure 25.

Probability in the first linear excited state (close to vortex) as function of time t for different values; there is a sharp disapperance of vortex for ; for the same behavior continues up to and may be continued beyond this maximal computation time.

Figure 25.

Probability in the first linear excited state (close to vortex) as function of time t for different values; there is a sharp disapperance of vortex for ; for the same behavior continues up to and may be continued beyond this maximal computation time.

Figure 26.

Nonlinear vortex fields (amplitude and phase) are shown at time for (vortex is destroyed) and (vortex survive). The video of time evolution of is shown for (left image) and (right image) up to in the Supplementary Material file videovortex.mp4.

Figure 26.

Nonlinear vortex fields (amplitude and phase) are shown at time for (vortex is destroyed) and (vortex survive). The video of time evolution of is shown for (left image) and (right image) up to in the Supplementary Material file videovortex.mp4.

Figure 27.

Time development of dynamical thermalization and RJ condensate formation (yellow band) are shown via probabilitis

at linear eigenmodes

(color bar) at short (left panel) and long (right panel) times; here

, initial state is

at

as in

Figure 21,

Figure 22.

Figure 27.

Time development of dynamical thermalization and RJ condensate formation (yellow band) are shown via probabilitis

at linear eigenmodes

(color bar) at short (left panel) and long (right panel) times; here

, initial state is

at

as in

Figure 21,

Figure 22.