Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

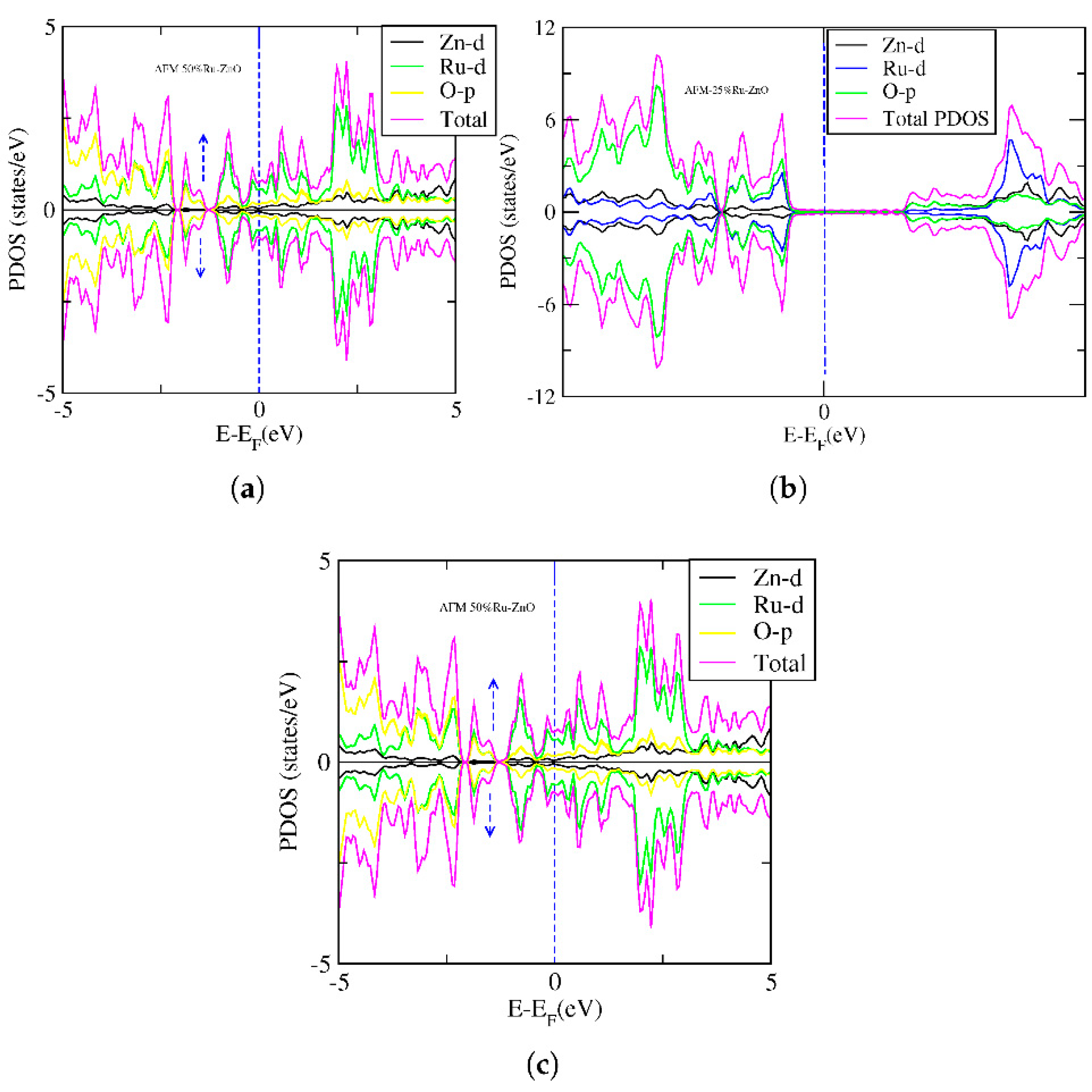

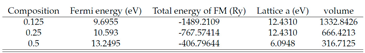

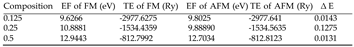

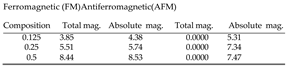

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendation

Acknowledgment: We gratefully acknowledge Adama Science and Technology University, the computational lab, and the Department of Applied Physics

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaghoubi, Sina and Mousavi, Seyyed Mojtaba and Babapoor, Aziz and Binazadeh, Mojtaba and Lai, Chin Wei and Althomali, Raed H and Rahman, Mohammed M and Chiang, Wei-Hung, Photocatalysts for solar energy conversion: Recent advances and environmental applications, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 200 114538 (2024).

- Ong, Chin Boon and Ng, Law Yong and Mohammad, Abdul, A review of ZnO nanoparticles as solar photocatalysts: Synthesis, mechanisms and applications, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 81536-551 (2018).

- Johar, Muhammad Ali and Afzal, Rana Arslan and Alazba, Abdulrahman Ali and Manzoor, Umair, Photocatalysis and bandgap engineering using ZnO nanocomposites, Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2015(1)934587(2015).

- Bhapkar, Abhishek R and Bhame, Shekhar, A review on ZnO and its modifications for photocatalytic degradation of prominent textile effluents: Synthesis, mechanisms, and future directions, Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 112553 (2024).

- Dasuki, Dema and Habanjar, Khulud and Awad, Ramdan, Effect of growth and calcination temperatures on the optical properties of ruthenium-doped ZnO nanoparticles, Condensed Matter, 8(4) 102( 2023).

- Nguyen-Phan, Thuy-Duong and Luo, Si and Vovchok, Dimitriy and Llorca, Jordi and Sallis, Shawn and Kattel, Shyam and Xu, Wenqian and Piper, Louis FJ and Polyansky, Dmitry E and Senanayake, Sanjaya D and others, Three-dimensional ruthenium-doped TiO 2 sea urchins for enhanced visible-light-responsive H22 production, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 18 (23) 15972-15979 (2016).

- Singh, Prabhat Kumar and Singh, Neetu and Singh, Mridula and Singh, Saurabh Kumar and Tandon, Poonam, Development and characterization of varying percentages of Ru-doped ZnO (x Ru: ZnO; 1% x 5%) as a potential material for LPG sensing at room temperature, Applied Physics A, 126 1-14 (2020).

- Krishnan, Bindu and Shaji, Sadasivan and Acosta-Enriquez, MC and Acosta-Enriquez, EB and Castillo-Ortega, R and Zayas, MA E and Castillo, SJ and Palama, Ilaria Elena and D’Amone, Eliana and Pech-Canul, Martin I and others, Group II–VI Semiconductors, Semiconductors: synthesis, properties and applications, 397-464 (2019).

- John, Rita and Padmavathi, S and others, Ab initio calculations on structural, electronic and optical properties of ZnO in wurtzite phase, Crystal structure theory and applications, 5(02) 24 (2016).

- Witkowski, BS, Applications of ZnO Nanorods and Nanowires–A Review, Acta Physica Polonica: A, 134(6) (2018).

- Nizamov, Timur R and Amirov, Abdulkarim A and Kuznetsova, Tatiana O and Dorofievich, 433 Irina V and Bordyuzhin, Igor G and Zhukov, Dmitry G and Ivanova, Anna V and Gabashvili, Anna N and Tabachkova, Nataliya Yu and Tepanov, Alexander A and others, Synthesis and functional characterization of CoxxFe3−xO4BaTiO3 magnetoelectric nanocomposites for biomedical applications, Nanomaterials, 13(5) 811 (2023).

- Shabatina, Tatyana and Vernaya, Olga and Shumilkin, Aleksei and Semenov, Alexander and Melnikov, Mikhail, Nanoparticles of bioactive metals/metal oxides and their nanocomposites with antibacterial drugs for biomedical applications, Materials, 15(10) 3602 (2022).

- Krishnan, Bindu and Shaji, Sadasivan and Acosta-Enriquez, MC and Acosta-Enriquez, EB and Castillo-Ortega, R and Zayas, MA E and Castillo, SJ and Palama, Ilaria Elena and D’Amone, Eliana and Pech-Canul, Martin I and others, Group II–VI Semiconductors, Semiconductors: synthesis, properties and applications, 397-464 (2019).

- Sharma, Dhirendra Kumar and Shukla, Sweta and Sharma, Kapil Kumar and Kumar, Vipin, A review on ZnO: Fundamental properties and applications, Materials for Today: Proceedings, 49 3028-3035 (2022).

- Li, Yu and Yang, Xiao-Yu and Feng, Yi and Yuan, Zhong-Yong and Su, Bao-Lian, Onedimensional metal oxide nanotubes, nanowires, nanoribbons, and nanorods: synthesis, characterizations, properties and applications, Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences, 37(1) 1-74 (2012).

- Abdelmohsen, Ahmed and Ismail, Nahla, Morphology transition of ZnO and Cu2O nanoparticles to 1D, 2D, and 3D nanostructures: hypothesis for engineering of micro and nanostructures (HEMNS), Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, 94 213-228 (2020).

- Chauhan, Vishnu and Singh, Paramjit and Kumar, Rajesh, Ion beam-induced modifications in ZnO nanostructures and potential applications, Nanostructured Zinc Oxide, 117-155 (2021).

- Teng, Feng and Hu, Kai and Ouyang, Weixin and Fang, Xiaosheng, Photoelectric detectors based on inorganic p-type semiconductor materials, Advanced Materials, 30(35) 1706262 (2018).

- Ouyang, Weixin and Teng, Feng and He, Jr-Hau and Fang, Xiaosheng, Enhancing the photoelectric performance of photodetectors based on metal oxide semiconductors by charge-carrier engineering, Advanced Functional Materials, 29(9) 1807672 (2019).

- Zafar, Amina and Younas, Muhammad and Fatima, Syeda Arooj and Qian, Lizhi and Liu, Yanguo and Sun, Hongyu and Shaheen, Rubina and Nisar, Amjad and Karim, Shafqat and Nadeem, Muhammad and others, Frequency stable dielectric constant with reduced dielectric loss of one-dimensional ZnO–ZnS heterostructures, Nanoscale, 13(37) 15711-15720 (2021).

- Goktas, A and Aslan, F and Ye,silata, B and Boz, ˙I, Physical properties of solution processable ntype Fe and Al co-doped ZnO nanostructured thin films: role of Al doping levels and annealing, Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, 75 221-233 (2018).

- Singh, Pushpendra and Kumar, Ranveer and Singh, Rajan Kumar, Progress on transition metaldoped ZnO nanoparticles and its application, Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 58(37) 17130-17163( 2019).

- Kayani, Aminuddin Bin Ahmad and Kuriakose, Sruthi and Monshipouri, Mahta and Khalid, Fararishah Abdul and Walia, Sumeet and Sriram, Sharath and Bhaskaran, Madhu, UV photochromism in transition metal oxides and hybrid materials, Small, 17(32) 2100621 (2021).

- Ivanov, SA and Sarkar, Tapati and Bazuev, GV and Kuznetsov, MV and Nordblad, Per and Mathieu, Roland, Modification of the structure and magnetic properties of ceramic La2CoMnO6 with Ru doping, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 752 420-430 (2018).

- Al Shomar, SM, Investigation of the effect of doping concentration in Ruthenium-doped TiO2 thin films for solar cells and sensors applications, Materials Research Express, 7(3) 036409 (2020).

- Medhi, Riddhiman and Li, Chien-Hung and Lee, Sang Ho and Marquez, Maria D and Jacobson, Allan J and Lee, Tai-Chou and Lee, T Randall, Uniformly spherical and monodisperse antimonyand zinc-doped tin oxide nanoparticles for optical and electronic applications, ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2(10) 6554-6564 (2019).

- Chen, Q and Shen, CY and Yang, XH and Yang, XJ and Li, YP and Feng, CM and Xu, ZA, Effect of ruthenium doping on superconductivity in Nb2PdS5, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 807(5) 052002( 2017).

- Papadimitriou, Dimitra N, Engineering of optical and electrical properties of electrodeposited 487 highly doped Al: ZnO and In: ZnO for cost-effective photovoltaic device technology, Micromachines, 13(11) 1966 (2022).

- Vinoditha, U and Sarojini, BK and Sandeep, KM and Narayana, B and Maidur, SR and Patil, PS 490 and Balakrishna, KM, Defects-induced nonlinear saturable absorption mechanism in europiumdoped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by facile hydrothermal method, Applied Physics A, 1251-11(2019).

- Vikal, Sagar and Meena, Savita and Gautam, Yogendra K and Kumar, Ashwani and Sethi, 494 Mukul and Meena, Swati and Gautam, Durvesh and Singh, Beer Pal and Agarwal, Prakash Chandra and Meena, Mohan Lal and others, Visible-light induced effective and sustainable remediation of nitro organics pollutants using Pd-doped ZnO nanocatalyst, Scientific Reports, 14(1) 22430 (2024).

- Huang, Jinyu and Zhou, Jiaxi and Liu, Zhenhua and Li, Xuejin and Geng, Youfu and Tian, Xiao- 499 qing and Du, Yu and Qian, Zhengfang, Enhanced acetone-sensing properties to ppb detection level using Au/Pd-doped ZnO nanorod, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 310127129 (2020).

- Hessien, Manal and Da’na, Enshirah and Kawther, AL and Khalaf, Mai M, Nano ZnO (hexago- 502 nal wurtzite) of different shapes under various conditions: Fabrication and characterization, Materials Research Express, 6(8)085057 (2019).

- Ruterana, Pierre and Abouzaid, Morad and Bere, A and Chen, Jie, Formation of a low energy 505 grain boundary in ZnO: The structural unit concept in hexagonal symmetry materials, Journal of Applied Physics, 103(3) (2008).

- Ekthammathat, Nuengruethai and Thongtem, Titipun and Phuruangrat, Anukorn and 508 Thongtem, Somchai, Characterization of ZnO flowers of hexagonal prisms with planar and hexagonal pyramid tips grown on Zn substrates by a hydrothermal process, Superlattices and Microstructures, 53195-203 (2013).

- Samadi, Morasae and Zirak, Mohammad and Naseri, Amene and Khorashadizade, Elham 512 and Moshfegh, Alireza Z, Recent progress on doped ZnO nanostructures for visible-light photocatalysis, Thin solid films, 605 2-19 (2016).

- Han, Sumei and Yun, Qinbai and Tu, Siyang and Zhu, Lijie and Cao,Wenbin and Lu, Qipeng, 515 Metallic ruthenium-based nanomaterials for electrocatalytic and photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 7(43) 24691-24714 (2019).

- Zhao, Ming and Xia, Younan, Crystal-phase and surface-structure engineering of ruthenium 518 nanocrystals, Nature Reviews Materials, 5(6) 440-459 (2020) 519.

- Zafar, Zaiba and Yi, Shasha and Li, Jinpeng and Li, Chuanqi and Zhu, Yongfa and Zada, 520 Amir and Yao, Weijing and Liu, Zhongyi and Yue, Xinzheng, Recent development in defects engineered photocatalysts: an overview of the experimental and theoretical strategies, Energy & Environmental Materials, 5(1) 68-114 (2022).

- Vaiano, Vincenzo and Iervolino, Giuseppina, Photocatalytic removal of methyl orange azo dye 524 with simultaneous hydrogen production using Ru-modified ZnO photocatalyst, Catalysts, 9(11) 964 (2019).

- Maiti, Sandip and Maiti, Kakali and Curnan, Matthew T and Kim, Kyeounghak and Noh, Kyung- 527 Jong and Han, Jeong Woo, Engineering electrocatalyst nanosurfaces to enrich the activity by inducing lattice strain, Energy & Environmental Science, 14(7)3717-3756 (2021).

- Fang, Xiaoyu and Choi, Ji Yong and Stodolka, Michael and Pham, Hoai TB and Park, Jihye, 530 Advancing Electrically Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks for Photocatalytic Energy Conversion, Accounts of Chemical Research, 57(16) 2316-2325 (2024).

- Chen, Yuanjie and He, Junqiao and Lei, Haiyan and Tu, Qunyao and Huang, Chen and Cheng, 533 Xiangwei and Yang, Xiazhen and Liu, Huazhang and Huo, Chao, Regulating oxygen vacancies by Zn atom doping to anchor and disperse promoter Ba on MgO support to improve Ru-based catalysts activity for ammonia synthesis, RSC advances, 14(19) 13157-13167 (2024).

- Dasuki, Dema and Habanjar, Khulud and Awad, Ramdan, Effect of growth and calcination 537 temperatures on the optical properties of ruthenium-doped ZnO nanoparticles, Condensed Matter, 8(4) 102 (2023).

- Ren, Manman and Guo, Xiangyu and Huang, Shiping, Transition metal atoms (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, 540 Zn) doped RuIr surface for the hydrogen evolution reaction: A first-principles study, Applied Surface Science, 556 149801 (2021).

- Nigam, Rashmi and Pan, Alexey V and Dou, SX, Explanation of magnetic behavior in Ru-based superconducting ferromagnets, Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics, 77(13) 134509 (2008).

- Yuan, HK and Chen, H and Kuang, AL and Wu, B and Wang, JZ, Structural and magnetic properties of small 4d transition metal clusters: role of spin orbit coupling, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 116(47) 11673-11684 (2012).

- Chhowalla, Manish and Jena, Debdeep and Zhang, Hua, Two-dimensional semiconductors for 549 transistors, Nature Reviews Materials, 1(11) 1-15 (2016).

- Li, Ru and Qiu, Li-Peng and Cao, Shi-Ze and Li, Zhi and Gao, Shi-Long and Zhang, Jun and Ramakrishna, Seeram and Long, Yun-Ze, Research advances in magnetic field-assisted photocatalysis, Advanced Functional Materials, 34(33) 2316725 (2024).

- Huynh, Hung Quang and Pham, Kim Ngoc and Phan, Bach Thang and Tran, Cong Khanh and Lee, Heon and Dang, Vinh Quang, Enhancing visible-light-driven water splitting of ZnO nanorods by dual synergistic effects of plasmonic Au nanoparticles and Cu dopants, Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 399 112639 (2020).

- Zhang, Peng and Wang, Tuo and Chang, Xiaoxia and Gong, Jinlong, Effective charge carrier 558 utilization in photocatalytic conversions, Accounts of chemical research, 49(5) 911-921 (2016) 559.

- Marschall, Roland, Semiconductor composites: strategies for enhancing charge carrier sep- 560 aration to improve photocatalytic activity, Advanced Functional Materials, 24(17) 2421-2440 (2014).

- Zhao, Zhiyong and Zhang, Tao and Yue, Shuai and Wang, Pengfei and Bao, Yueping and Zhan, 563 Sihui, Spin polarization: a new frontier in efficient photocatalysis for environmental purification and energy conversion, ChemPhysChem, 25(4) e202300726 (2024).

- aRen, Manman and Guo, Xiangyu and Huang, Shiping, Transition metal atoms (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, 566 Zn) doped RuIr surface for the hydrogen evolution reaction: A first-principles study, Applied Surface Science, 556 149801 (2021).

- Lin, Tao and Tomaz, MA and Schwickert, MM and Harp, GR, Structure and magnetic properties of Ru/Fe (001) multilayers,Physical Review B, 58(2) 862 (1998).

- Tveten, Erlend G and Muller, Tristan and Linder, Jacob and Brataas, Arne, Intrinsic magnetiza- 571 tion of antiferromagnetic textures, Physical Review B, 93(10) 1044081 (2016).

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).