1. Introduction

The consumption of psychoactive substances among university students must be understood within the broader context of the high prevalence of mental health disorders in this population, particularly anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders[

1]. Benzodiazepines—central nervous system depressants with anxiolytic, hypnotic, and muscle relaxant properties—are part of this phenomenon.

In recent years, several studies have documented the non-prescribed use of psychotropic medications as a strategy employed by students to cope with academic stress, insomnia, and the pressure to maintain high academic performance[

2]. This pattern of consumption, often perceived as a form of self-medication or as a seemingly harmless aid, is facilitated by easy access to these drugs and a low perception of risk, which increases the potential for abuse and dependence[

3].

Despite growing interest in this issue, the scientific literature still presents important gaps. In particular, there are few studies that compare benzodiazepine use between medical students and students from other university degrees. This distinction is especially relevant, as medical students tend to experience higher levels of anxiety, as well as greater familiarity with the use and prescription of psychotropic drugs[

4]. Moreover, many existing studies rely on small or non-representative samples, which limits the identification of risk profiles associated with specific academic disciplines. Additionally, it is uncommon for these studies to examine in detail aspects such as personal motivations, access routes, or the subjective perception of dependence.

Given these limitations, this study aims to compare the prevalence of benzodiazepine use between medical students and students from other university degrees in the Community of Madrid. Secondary objectives include: Estimating the overall use of psychoactive substances for managing academic stress; identifying the most frequently used substances for this purpose; describing the main access routes to these substances; analyzing the frequency and motivations for benzodiazepine use; and exploring its association with cognitive symptoms such as difficulties in concentration and the subjective perception of dependence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional observational study conducted within the Teaching Unit of the 12 de Octubre–Infanta Cristina University Hospitals.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved (54/24 ACT 06/2024) by the Research Ethics Committee of Puerta de Hierro University Hospital in Majadahonda on March 18, 2024. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained digitally before completing the survey. The questionnaire was anonymous and did not collect any personal identifiers. Respondents were informed about the study’s purpose, data confidentiality, and their right to withdraw at any time without justification. No sensitive personal data were collected, and no clinical intervention or diagnostic assessment was performed. Therefore, no written informed consent was required according to applicable local regulations for research involving anonymized survey data in university settings.

Data collection was carried out between April 1 and April 30, 2024, through an anonymous online survey developed using Microsoft Forms®. The questionnaire consisted of 19 questions (17 single-answer and 2 multiple-answer items) and was disseminated via social media platforms and university forums, aiming to reach a broad and diverse sample.

2.2. Study Population

The target population was university students enrolled in institutions located in the Community of Madrid. The only inclusion criterion was being enrolled, at the time of the survey, in a Bachelor’s degree program offered by a public or private university, the Distance University of Madrid (UDIMA), or the Madrid and Madrid-South centers of the National Distance Education University (UNED). Students under the age of 18 were excluded.

2.3. Sample Size

To determine the appropriate sample size, the proportion of medical students within the total student population of the Community of Madrid was estimated. According to official data, there were 358,881 enrolled university students during the 2023–2024 academic year, with approximately 9,037 of them enrolled in medical programs. This figure was extrapolated from the proportion observed in the previous academic year (2.52%).

The sample size calculation was based on previous studies estimating a 4.50% prevalence of non-medical benzodiazepine use in the general university population, compared to 0.90% among medical students. Assuming a 95% confidence level, 80% statistical power, and the need to compare two proportions, a minimum sample of 317 students was calculated. To account for potential exclusions or invalid responses, a 15% margin was added, establishing a final target of 373 participants.

Although no formal dropouts occurred, several responses were excluded at the beginning of the analysis for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Specifically, questionnaires completed by individuals not enrolled in university education—mostly vocational training students—were excluded prior to statistical processing. As a result, the final valid sample consisted of 373 participants, meeting the pre-established target.

2.4. Studied Variables

The survey included both sociodemographic and substance use-related variables. Sociodemographic variables comprised age, gender, and degree program (medicine or other health-related and non-health-related degrees). Variables related to benzodiazepine use included awareness of the drug, history of use, frequency and context of consumption (e.g., academic stress, sleep difficulties, clinical diagnosis), route of acquisition (prescribed or non-prescribed), and perception of side effects. For participants who reported benzodiazepine use, additional questions explored dosage regularity, timing of initiation, and subjective experience of dependence or control. The questionnaire also inquired about the use of other psychoactive substances, including alcohol, cannabis, and antidepressants, for academic stress management.

2.5. Intervention

The intervention consisted of the dissemination of an anonymous, self-administered online questionnaire developed ad hoc for the study. The survey was distributed through institutional university mailing lists and academic forums in the Community of Madrid during the academic year 2022–2023. Participation was voluntary and students were informed of the study’s objectives, the estimated time to complete the survey, and the anonymity of their responses. No incentives were provided. The questionnaire was designed to collect detailed data regarding sociodemographic characteristics, academic context, benzodiazepine and other psychoactive substance use, and perceived effects. No clinical or pharmacological intervention was performed, and the study was observational in nature.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JAMOVI® software (version 2.3.28). Descriptive techniques were applied to characterize the sample and the main study variables. The chi-squared test was used to identify statistically significant differences in benzodiazepine use between medical and non-medical students, as well as by gender.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The final sample consisted of 375 university students. The mean age was 21.64 years (SD = 1.93), and participants were distributed across four age groups: 17–20, 21–23, 24–26, and over 26 years. The most common age range was 21–23 years. Regarding gender, 69.10% identified as female, 30.40% as male, and 0.50% preferred not to specify.

Table 1.

Summary of key descriptive variables of the study population (n = 373)

Table 1.

Summary of key descriptive variables of the study population (n = 373)

| Variable |

Category / Statistic |

Value |

| Age (mean ± SD) |

Years |

21.64 ± 1.93 |

| Gender |

Female |

69.10% |

| |

Male |

30.40% |

| |

Non-disclosed |

0.50% |

| Degree program |

Medicine |

53.60% |

| |

Other degrees |

46.40% |

| Benzodiazepine awareness |

Knows what they are |

78.93% |

| Use of substances for stress |

Any substance |

32.27% |

| |

Benzodiazepines |

23.47% |

| |

Alcohol |

17.33% |

| Benzodiazepine use (ever) |

Yes |

25.07% |

| |

Medicine students |

32.34% |

| |

Other students |

16.67% |

| Subjective side effects reported |

None |

40.00% |

| |

Drowsiness, etc. |

60.00% (combined) |

With respect to academic year, 5.33% of students were in their first year, 13.87% in second, 18.13% in third, 36.00% in fourth, 18.40% in fifth, and 7.20% in sixth year. A small proportion (1.07%) did not respond to this item. The most frequent profile was a female student aged 21–23 years enrolled in the fourth year of her degree. Overall, 53.60% of the sample were enrolled in a medical degree (

Table 2).

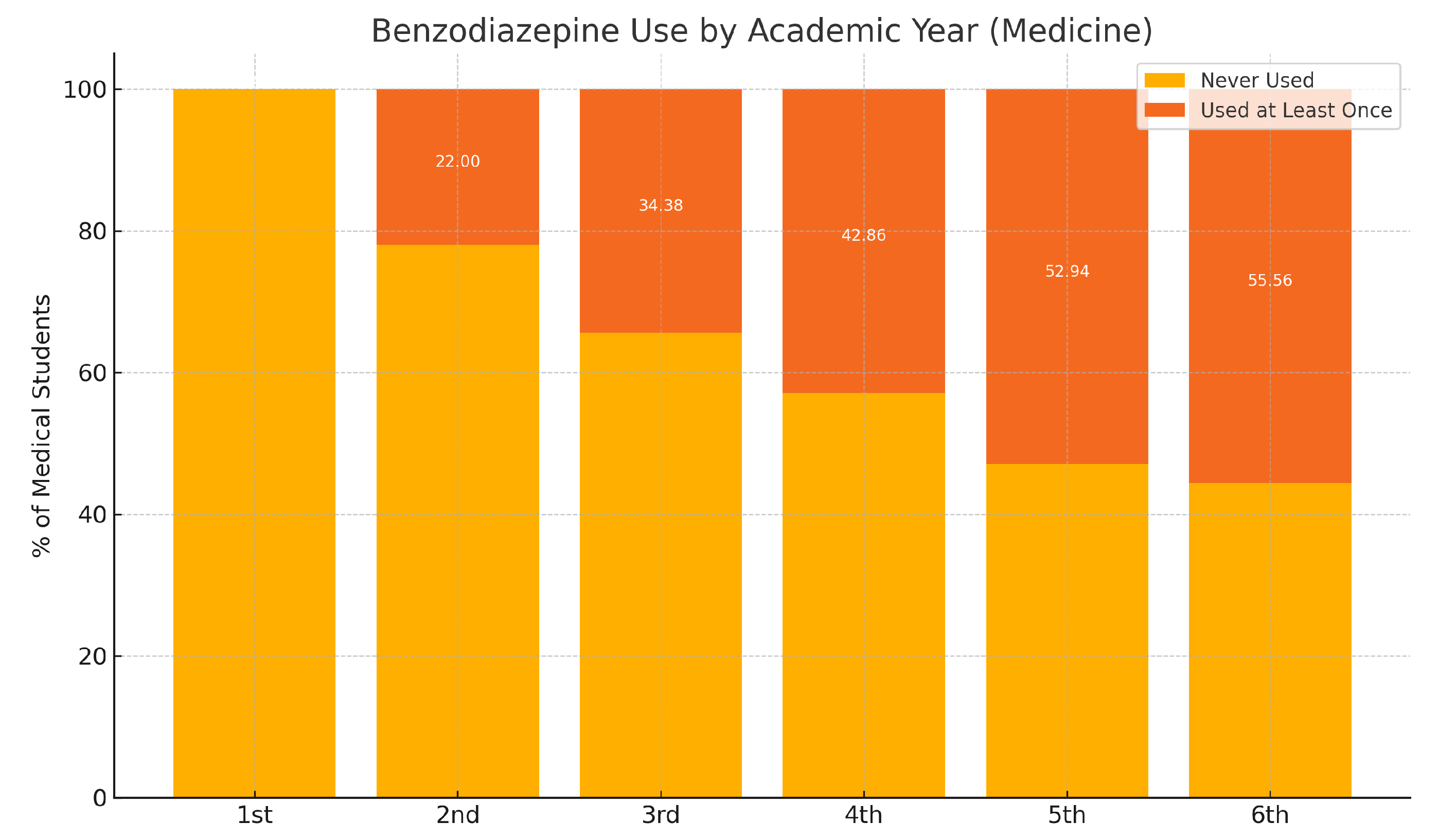

Table 2.

Prevalence of benzodiazepine use by academic year among medical students

Table 2.

Prevalence of benzodiazepine use by academic year among medical students

| Academic Year |

Never Used (%) |

Used at Least Once (%) |

| First Year |

100.00 |

0.00 |

| Second Year |

78.00 |

22.00 |

| Third Year |

65.63 |

34.38 |

| Fourth Year |

57.14 |

42.86 |

| Fifth Year |

47.06 |

52.94 |

| Sixth Year |

44.44 |

55.56 |

Figure 1.

Benzodiazepine use by academic year (Medicine students).

Figure 1.

Benzodiazepine use by academic year (Medicine students).

3.2. Use of Psychoactive Substances

Among the respondents, 78.93% were aware of what benzodiazepines are, and 32.27% had used benzodiazepines or other psychoactive substances to manage stress related to their studies (

Table 3). Among these, benzodiazepines were the most commonly used substance, followed by alcohol, antidepressants, and cannabis (

Table 4).

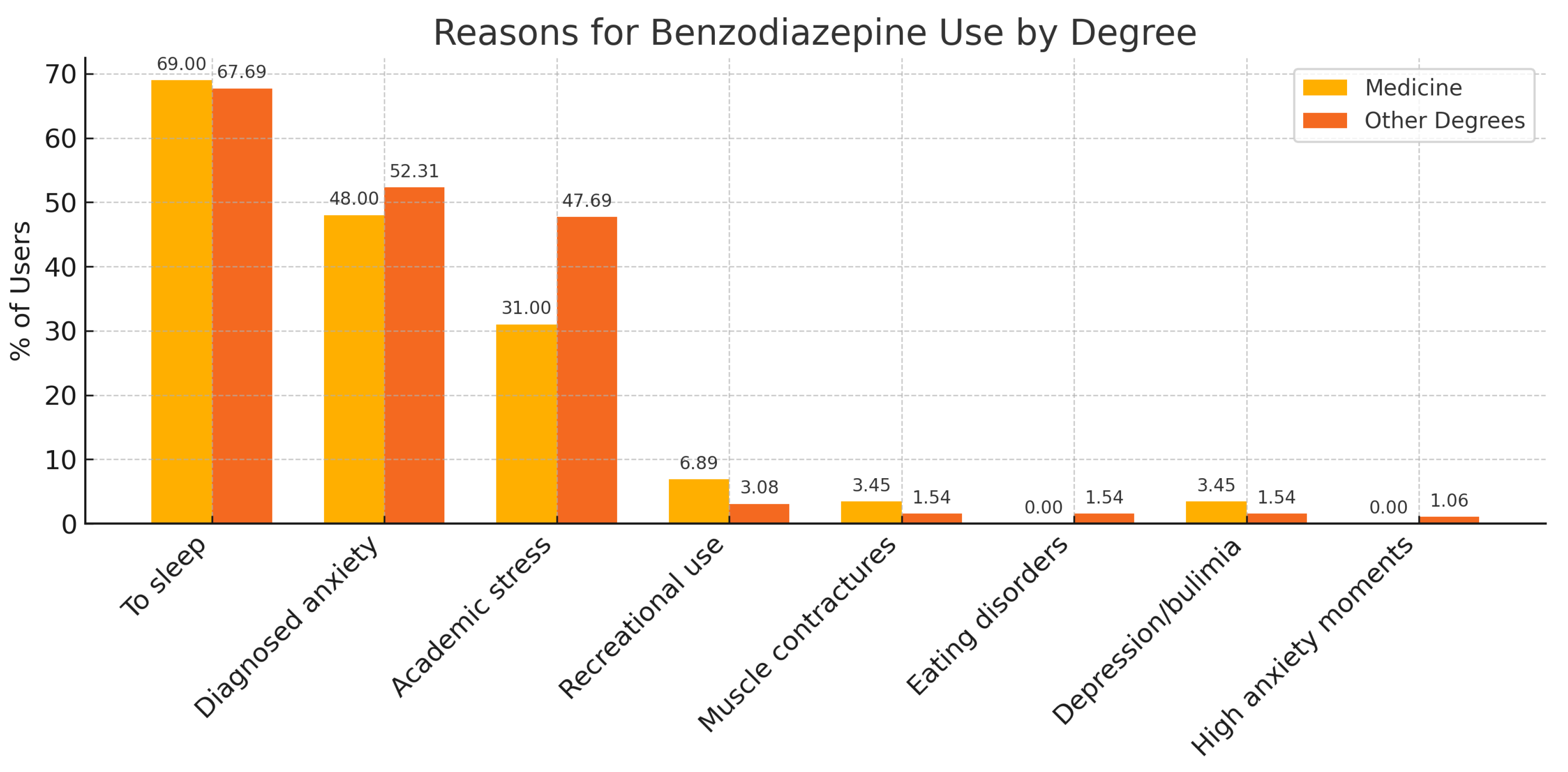

Figure 2.

Reasons for benzodiazepine use among university students.

Figure 2.

Reasons for benzodiazepine use among university students.

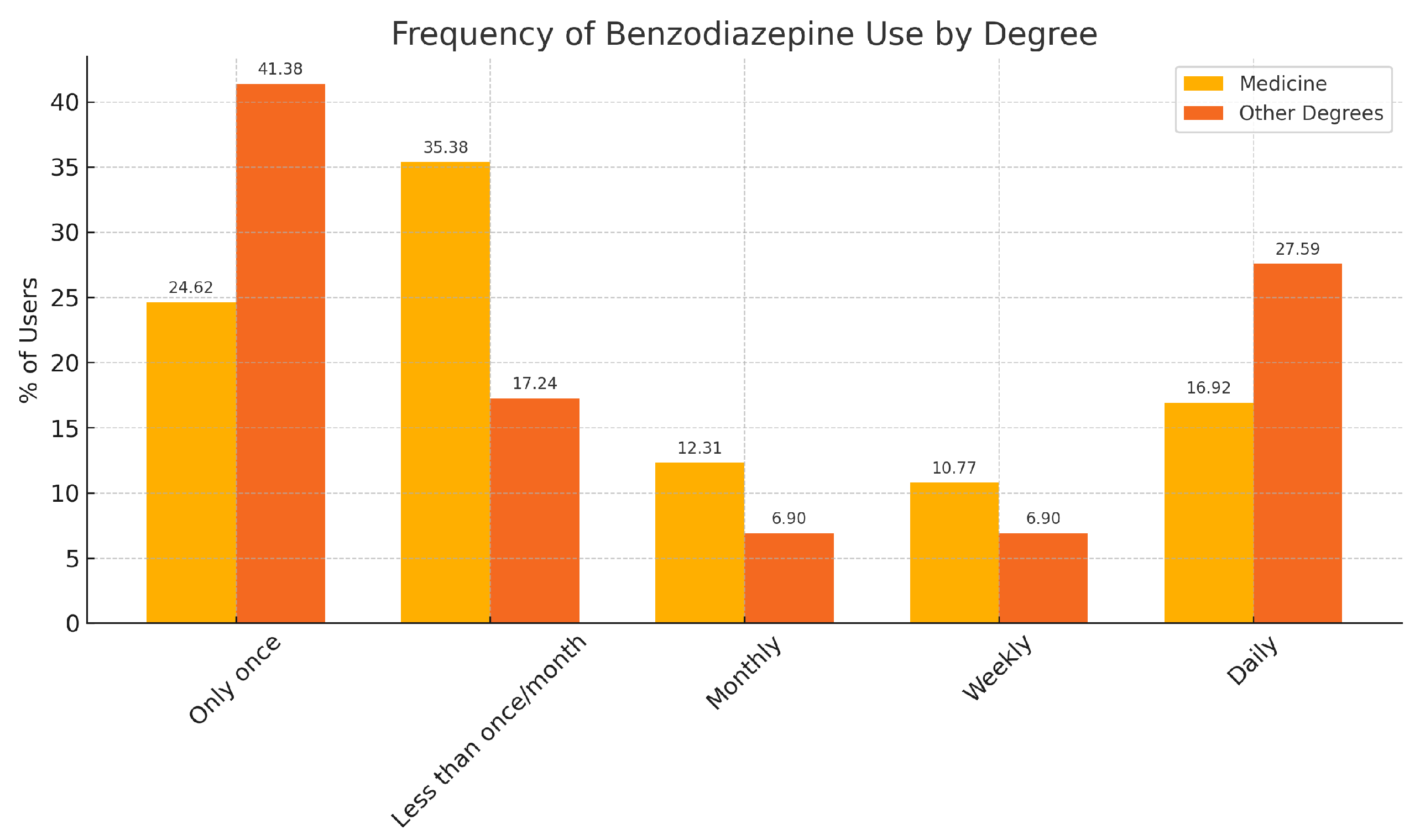

3.3. Frequency and Patterns of Benzodiazepine Use

A total of 25.07% of students reported having used benzodiazepines at least once. This percentage was higher among medical students (32.34%) compared to students from other degrees (16.67%) (

Table 5).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of benzodiazepine use by degree (stacked bar chart).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of benzodiazepine use by degree (stacked bar chart).

Among those who had used benzodiazepines, 29.79% reported using them only once, and another 29.79% used them less than once per month. Daily use was reported by 20.21% of these respondents. Weekly and monthly use were reported by 9.57% and 10.64%, respectively.

When comparing medical students with students from other degrees, the most common pattern among medical students was using benzodiazepines less than once a month, whereas among non-medical students, the most common pattern was having used them only once. Interestingly, daily use was slightly more common in non-medical degrees than in medicine (

Table 6 ).

Figure 4.

Frequency of benzodiazepine use by degree.

Figure 4.

Frequency of benzodiazepine use by degree.

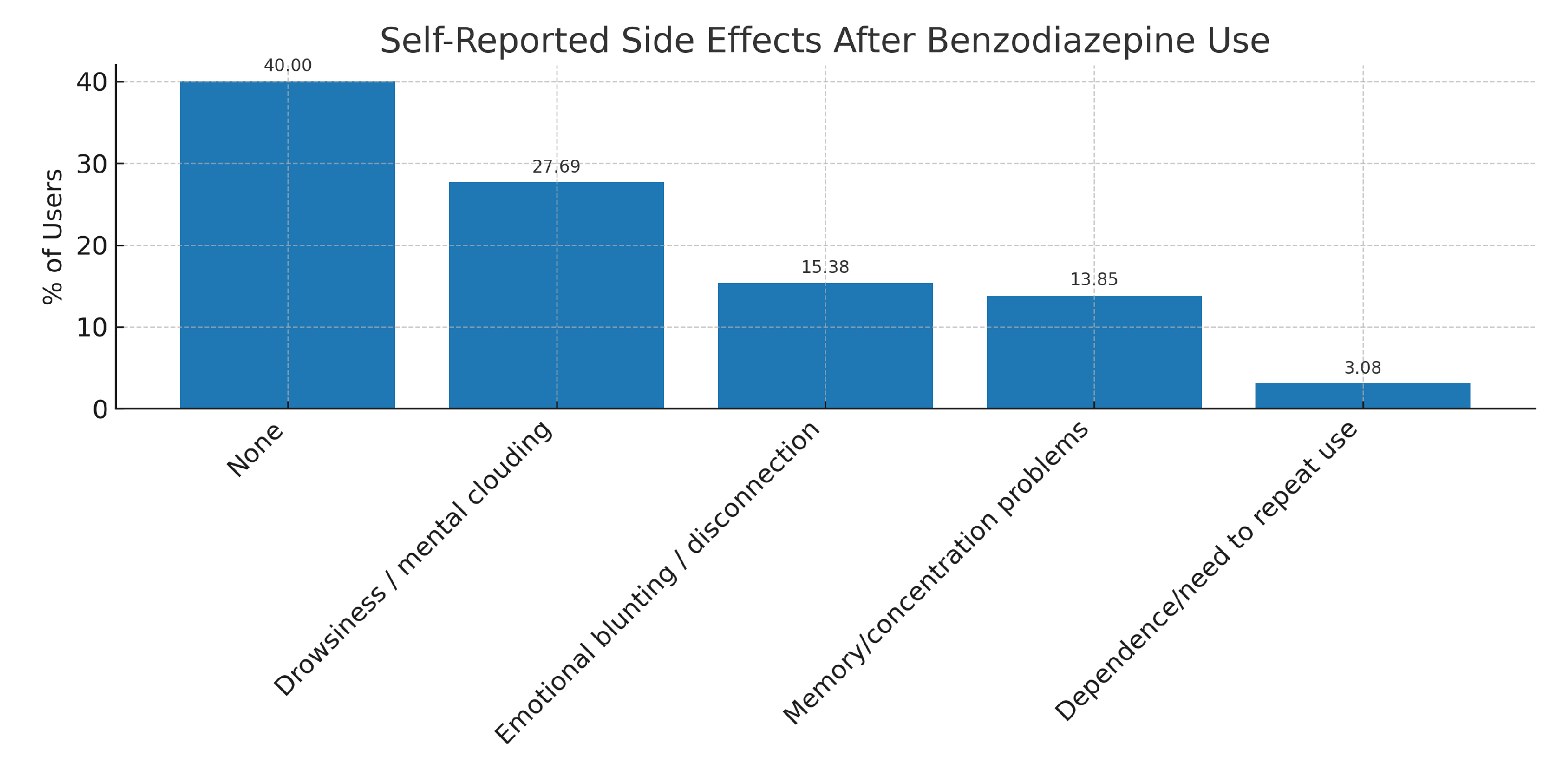

3.4. Adverse effects

Among students who had used benzodiazepines, 60.00% reported experiencing at least one adverse effect. The most commonly cited symptoms were drowsiness or mental clouding, emotional blunting, and difficulties with memory or concentration. A full breakdown of these self-reported side effects is presented in

Table 7 and illustrated in

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a significant prevalence of benzodiazepine use among university students, particularly among those enrolled in medical programs. These results are consistent with prior evidence suggesting elevated levels of anxiety and psychological distress in this population [

5], as well as greater familiarity with pharmacological agents among medical students [

6].

Benzodiazepines were most frequently used to manage sleep difficulties and academic stress—two factors that have also been associated with broader patterns of psychotropic drug use in young adults [

7]. Nearly one-third of students who reported using benzodiazepines did so without a medical prescription, suggesting the persistence of self-medication practices, which have been associated with greater risk of misuse and dependency [

8].

Moreover, the finding that over 20% of users reported daily benzodiazepine use raises concerns about the potential for dependence and long-term cognitive effects. These risks have been well-documented, particularly in the context of chronic or unsupervised use [

9,

10]. Such patterns, when initiated at a young age and under academic pressure, could lead to a normalization of pharmacological coping mechanisms that extend beyond university years.

A particularly noteworthy trend is the progressive increase in benzodiazepine use across academic years among medical students. While no first-year students reported use, prevalence increased steadily in higher academic levels, exceeding 50% in the final year. This trajectory may reflect greater academic stress, closer proximity to clinical environments where these medications are common, and an evolving perception of their acceptability. These findings mirror those of previous studies suggesting a “hidden curriculum” in health sciences education, where exposure to clinical practice influences attitudes toward psychotropic medication [

11].

Although 60% of students who had used benzodiazepines reported side effects—such as drowsiness, emotional blunting, and cognitive difficulties—only a minority perceived these symptoms as indicative of misuse or dependence. This underestimation may be influenced by familiarity bias, overconfidence in self-monitoring, or stigma regarding mental health vulnerability.

The study also identified differences between degree types. While medical students exhibited higher overall use, non-medical students were more likely to report using benzodiazepines specifically to cope with academic stress. This divergence in motivations may reflect differing access routes (e.g., clinical vs. informal), stress thresholds, or interpretations of acceptable self-care behavior.

From a public health and academic perspective, the results underscore the urgent need for preventive strategies in university settings. These should include structured psychoeducation on psychotropic medications, greater visibility of campus-based mental health services, and targeted interventions for at-risk groups. For medical students in particular, it is essential to integrate formal training on pharmacological ethics, substance misuse, and coping strategies into their curriculum.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a high prevalence of benzodiazepine use among university students, especially those enrolled in medical programs. The findings highlight concerning patterns of non-prescribed use, progressive increase across academic years, and limited awareness of potential side effects or dependency risks. These results emphasize the need for targeted preventive actions, including psychoeducational initiatives, enhanced mental health support, and training in pharmacological ethics for future healthcare professionals.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the use of a self-administered online survey introduces a potential self-selection bias, whereby students with prior experience or interest in the subject may have been more likely to respond. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study precludes any causal inferences between academic progression and benzodiazepine use. Third, although efforts were made to ensure sample diversity, the study was geographically limited to the Community of Madrid, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Additionally, all data were self-reported, which may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias, especially regarding sensitive topics such as drug use. Finally, the survey did not include clinical validation of psychiatric diagnoses or substance dependence criteria, relying entirely on subjective responses.

Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insight into a scarcely explored phenomenon in Spanish university populations and highlights important differences in behavior and risk perception among students of different academic backgrounds.

7. Future Directions

Further research should explore the motivations and contextual factors behind benzodiazepine use through qualitative or longitudinal approaches. Expanding the study to multiple universities and incorporating clinical assessments could improve the accuracy and generalizability of findings. Future work should also evaluate the effectiveness of specific interventions designed to reduce reliance on psychotropic substances in academic settings.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, D.L-T. and P.F.; methodology, D.L-T; software, P.F.; validation, F.G-S., D.L and F.R-R.; formal analysis, P.F.; investigation, P.F.; resources, D.L-T.; data curation, P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, P.F and F.G-S.; writing—review and editing, F.G-S and S.I-K.; visualization, F.G.; supervision, F.G-S.; project administration, N.M-G.; funding acquisition, F.G-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”, please turn to the

CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded through the funds of the IDIPHISA Foundation (Research Institute of the Puerta de Hierro University Hospital), with which the Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Madrid was affiliated, grant number

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Puerta de Hierro University Hospital in Majadahonda on March 18, 2024 (54/24 ACT 06/2024)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) for language refinement and the generation of visual elements (figures and tables) to support the preparation of this manuscript. The authors reviewed and verified all AI-assisted content to ensure accuracy and compliance with the scientific and ethical standards of the journal. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UDIMA |

Distance University of Madrid |

| UNED |

National Distance Education University |

References

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2018, 127, 623–638.

- Thomas, C.; Dondaine, T.; Caron, C.; Nowak, C.; Naassila, M.; Dumont, M. Factors associated with the use of benzodiazepine and opioid prescription drugs in the student population: a cross-sectional study. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13040.

- Hockenhull, J.; Wood, D.; Dargan, P. Non-medical use of benzodiazepines and GABA analogues in Europe. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2021, 87, 1684–1694.

- Sandoval, K.; Morote-Jayacc, P.; Moreno-Molina, M.; Taype-Rondan, A. Depresión, estrés y ansiedad en estudiantes de medicina humana de Ayacucho (Perú) en el contexto de la pandemia por COVID-19. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 2021, 50, 237–245.

- Quek, T.C.; Tam, W.S.; Tran, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ho, C.H.; et al. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 2735.

- Shrestha, D.; Adhikari, S.; Poudel, A.; Paudel, R.; Pathak, S.; Sapkota, N.; et al. Prevalence and reasons for the use of benzodiazepines among medical students of a teaching hospital. JNMA: Journal of the Nepal Medical Association 2021, 59, 920–925.

- McCabe, S.; Teter, C.; Boyd, C. Medical use, illicit use and diversion of prescription stimulant medication. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2006, 84, 7–15.

- McHugh, R.; Nielsen, S.; Weiss, R. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2015, 48, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.; Greenwood, K.; Jackson, M.; Crowe, S. Cognitive effects of long-term benzodiazepine use: a meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 2004, 18, 37–48.

- Maust, D.; Lin, L.; Blow, F. Benzodiazepine use and misuse among adults in the United States. Psychiatric Services 2019, 70, 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Parks, K.; Levonyan-Radloff, K.; Przybyla, S.; Darrow, S.; Muraven, M.; Hequembourg, A. University student perceptions about the motives for and consequences of nonmedical use of prescription drugs (NMUPD). Journal of American College Health 2017, 65, 457–465. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).