Introduction

In 2023, malaria was still the deadliest vector-borne disease, responsible for 597,000 deaths worldwide, 95% of which occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and most of which were due to

Plasmodium falciparum [

1]. Insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), combined with huge control efforts [

2,

3], have reduced the burden of malaria from 864,000 to 586,000 deaths between 2000 and 2015 [

1]. Over this period, malaria incidence was reduced by up to 50-75% in several high-burden countries [

3,

4]. Yet, malaria deaths have stalled since 2015 and have even increased since the COVID-19 pandemic due to disruptions in health services and intervention planning that have had latent effects until very recently [

1]. An increasing number of countries are now in the process of malaria elimination, with 35 countries committing to do so by 2030 under the Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030 [

5] and in line with Sustainable Development Goal Target 3.3, which includes reducing malaria incidence by at least 90% by 2030 [

6].

Achieving malaria elimination requires identifying the factors that perpetuate the disease hotspots, as they can help identify leverage points for more effective intervention planning. Previous studies have modelled malaria prevalence or incidence at the national level and identified contributing risk factors in Ghana [

7,

8], Rwanda [

9], Nigeria [

10,

11], Mozambique [

12,

13], Senegal [

14], Uganda [

15,

16], Zambia [

17,

18] and Cameroon [

19]. Yet national-level models assume spatial stationarity of malaria-determinants relationships and correlation structures [

20], whereas a few studies have shown that relationships with malaria and vector-borne diseases in general may vary according to several factors, such as mosquito vector species [

21], season [

22], or the scale considered (household, regional or national) [

21,

23,

24], also known as the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) [

25]. Relationships may also vary between different geographical contexts, as environmental and human factors may interact. This is illustrated by the ‘paddies paradox’, where rice paddy irrigated areas may be associated with lower malaria incidence due to improved socioeconomic conditions and changes in the main mosquito species [

26]. Transmission drivers may differ between lowland and highland areas [

20,

21] or between urban and rural settings [

27], as well as between cities [

28,

29].

Pertaining to the geographical context, the level of endemicity can significantly influence both the strength of and relationships with malaria [

30]. Endemicity directly affects immunity in children and adults, which means that adults in areas with different levels of endemicity may be more or less at risk of malaria [

31], and the risk factors may not be the same (e.g. adult migration may be more of a risk factor in low-endemic areas). Accounting for endemicity levels when analysing malaria risk factors is therefore essential, especially considering that malaria control and elimination interventions and their effects vary according to the level of transmission (e.g. seasonal chemoprevention in highly endemic areas and case investigation in low endemic areas) [

3]. For example, [

32] showed that the interaction between seasonality and level of endemicity influences malaria repeat episodes and should therefore influence the choice of ACT duration. Stakeholder needs may also depend on the spatial scale [

33]. In addition, as (pre-)elimination interventions are progressively implemented within countries, and depending on their success, differences in endemicity between regions may become more pronounced.

Fine-scale malaria models are often based on household surveys that test malaria in nationally representative samples, such as the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) or the Malaria Indicator Surveys (MIS). Such surveys provide estimates of malaria prevalence among the individuals tested (usually children under 5 years of age). Although these surveys offer the possibility of regular updates as they are conducted on a regular basis [

34], they suffer from two main biases: first, in low transmission settings, samples contain excess zeros due to the rare occurrence of the disease [

35,

36], and second, adolescents and adults are not included in the testing, whereas malaria elimination would require knowledge of the malaria burden in all age groups [

37]. Alternatively, routine data collected monthly by health facilities can be used to estimate malaria incidence, providing continuous estimates over time and over large spatial scales [

38]. Although these data also suffer from known biases such as under-reporting, low testing rate and missing the population that does not seek health care [

35,

38], they are an important source of epidemiological data on malaria, particularly in areas where prevalence may be less representative or reliable [

36]. In recent years, studies have begun to investigate the use of such surveillance data for spatio-temporal modelling and fine-scale prediction of malaria incidence [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Such predictive maps can help to identify malaria hotspots, guide intervention strategies and optimise health resource allocation. In this study, we propose to use dasymetric disaggregation, a method commonly used to disaggregate population census estimates [

43,

44], to produce fine-scale maps of malaria incidence. This approach relies on the redistribution of reported malaria cases from health facilities to a finer spatial resolution, thereby improving the granularity of risk estimates.

With the goal of malaria elimination by 2030, Senegal has reduced malaria incidence and mortality in recent decades thanks to improved malaria control [

4,

45]. Despite significant efforts, malaria cases have stagnated and even increased from 2019 [

45], leading to an estimated 2128 deaths and 831 514 cases in 2022, accounting for 0.35% of the global mortality burden [

1]. However, these national estimates mask further heterogeneity at the sub-national level, as Senegal has a highly heterogeneous malaria endemic profile, lying in the transition zone between the low, intermediate and high endemic regions of West Africa. Three major endemicity groups can be distinguished (see

Figure 1) [

45]: 1) the rural south-eastern regions (Kolda, Kédougou, Tambacounda, collectively known as the KKT area) with high malaria transmission, representing only 12% of the total population but 65% of total malaria cases, 2) the western highly urbanised regions (Dakar, Diourbel, Kaolack) with intermediate transmission accounting for 30% of the national case burden and 3) the northern regions with low to very low malaria transmission and some areas classified as pre-elimination [

45]. The strong heterogeneity in endemicity levels across the country is likely to bias national malaria models. For example, [

46] showed that national population models in Senegal under-represented rural areas due to significant differences in population predictors between rural and urban areas and the high urban-rural divide in the country. Malaria cases in Senegal are reported through the District Health Surveillance System (DHIS2) platform, which maintained high reporting rates until 2021 (98%), but saw a significant drop to 27% in 2023 due to health worker strikes [

47].

The aim of this research is to model malaria incidence in Senegal from 2017 to 2021, using routine data from the DHIS2 platform and a set of high-resolution environmental and socio-economic variables. A key challenge in working with routine health facility data is the need to define catchment areas around health facilities to estimate population denominators. In this study, we account for this uncertainty by incorporating the probability of attending a health facility based on relative walking time, rather than assuming fixed, non-overlapping catchment boundaries. Spatio-temporal models of malaria incidence are then built within a Bayesian hierarchical framework implemented using the INLA-SPDE approach. Models are stratified by season and endemicity level and compared with a benchmark model at the national level to assess potential heterogeneity of malaria risk factors according to the transmission level, which may vary in time (i.e. per season) and space (i.e. per endemicity level). Lastly, dasymetric disaggregation is applied to generate high-resolution (1 km) maps of malaria incidence that can help support targeted intervention planning. The method of [

43] is adapted by considering the probability of attending a health facility and the pixel population in the disaggregation weights.

Figure 1.

Map of the 14 regions of Senegal grouped according to endemicity. Endemicity 1 corresponds to regions with high malaria transmission, endemicity 2 to regions with medium transmission and endemicity 3 to regions with low to very low transmission.

Figure 1.

Map of the 14 regions of Senegal grouped according to endemicity. Endemicity 1 corresponds to regions with high malaria transmission, endemicity 2 to regions with medium transmission and endemicity 3 to regions with low to very low transmission.

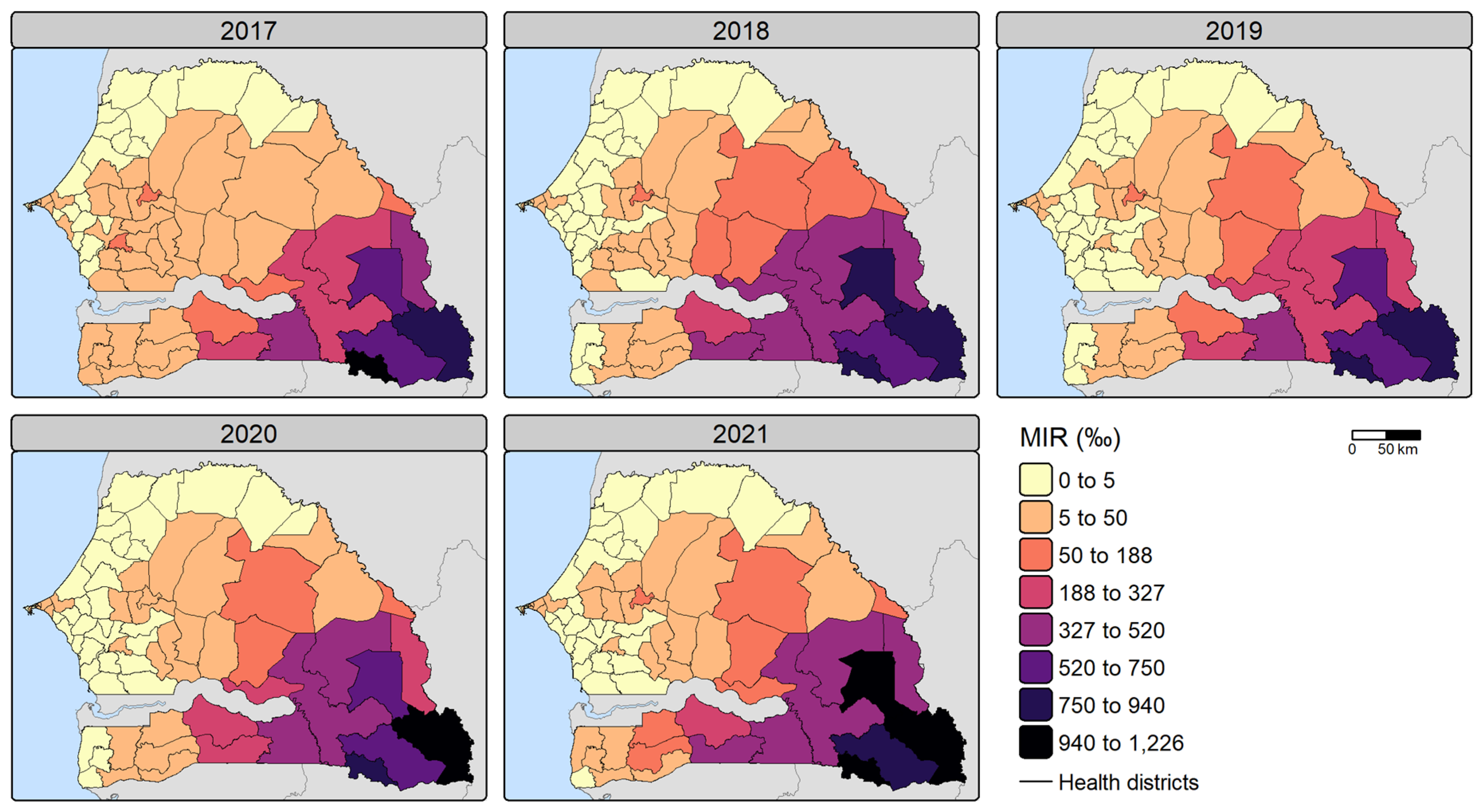

Figure 2.

Observed malaria incidence rates (MIR) (per 1,000 people) per health facility for 2017-2021. MIR were calculated using all annually reported cases.

Figure 2.

Observed malaria incidence rates (MIR) (per 1,000 people) per health facility for 2017-2021. MIR were calculated using all annually reported cases.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of malaria incidence rates (per 1,000 people) per health facility over 2017-2021. The middle horizontal line represents the median, while the dot represents the mean. Outliers are not shown to improve readability. Note that incidence rates above 1000‰ can be attributed to malaria repeat episodes [

32] and migration. Abbreviations: KKT (Kolda, Kédougou, Tambacounda), E1 (endemicity 1), E2 (endemicity 2), E3 (endemicity 3).

Figure 3.

Boxplot of malaria incidence rates (per 1,000 people) per health facility over 2017-2021. The middle horizontal line represents the median, while the dot represents the mean. Outliers are not shown to improve readability. Note that incidence rates above 1000‰ can be attributed to malaria repeat episodes [

32] and migration. Abbreviations: KKT (Kolda, Kédougou, Tambacounda), E1 (endemicity 1), E2 (endemicity 2), E3 (endemicity 3).

Figure 4.

Estimated malaria incidence rates (per 1,000 people) for 2017-2021 in Senegal by model. The number of cases per health facility was estimated by multiplying the posterior estimates (mean, 2.5th percentile and 97.5th percentile) of malaria incidence rate (MIR) per health facility by the total potential catchment population (i.e. assuming 100% of the population sought health care for fever). The total number of cases was summed and divided by the total population to calculate the annual MIR. The solid line represents the estimate based on the posterior mean MIR, while the shaded area is based on the posterior 2.5th and 97.5th percentile estimates. Note that the y-axis of the Endemicity 1 model estimates differs from the other models.

Figure 4.

Estimated malaria incidence rates (per 1,000 people) for 2017-2021 in Senegal by model. The number of cases per health facility was estimated by multiplying the posterior estimates (mean, 2.5th percentile and 97.5th percentile) of malaria incidence rate (MIR) per health facility by the total potential catchment population (i.e. assuming 100% of the population sought health care for fever). The total number of cases was summed and divided by the total population to calculate the annual MIR. The solid line represents the estimate based on the posterior mean MIR, while the shaded area is based on the posterior 2.5th and 97.5th percentile estimates. Note that the y-axis of the Endemicity 1 model estimates differs from the other models.

Figure 5.

Estimated malaria incidence rates (per 1,000 people) for 2017-2021 per health district. The number of cases per health facility was estimated by multiplying the posterior mean malaria incidence rate (MIR) per health facility by the total potential catchment population (i.e. assuming 100% of the population sought health care for fever). The total number of cases was summed per health district and divided by the total district population to calculate the MIR, which is then expressed per 1,000 people. These estimates are based on the benchmark model (BM). Note that incidence rates above 1000‰ can be attributed to malaria repeat episodes [

32] and migration.

Figure 5.

Estimated malaria incidence rates (per 1,000 people) for 2017-2021 per health district. The number of cases per health facility was estimated by multiplying the posterior mean malaria incidence rate (MIR) per health facility by the total potential catchment population (i.e. assuming 100% of the population sought health care for fever). The total number of cases was summed per health district and divided by the total district population to calculate the MIR, which is then expressed per 1,000 people. These estimates are based on the benchmark model (BM). Note that incidence rates above 1000‰ can be attributed to malaria repeat episodes [

32] and migration.

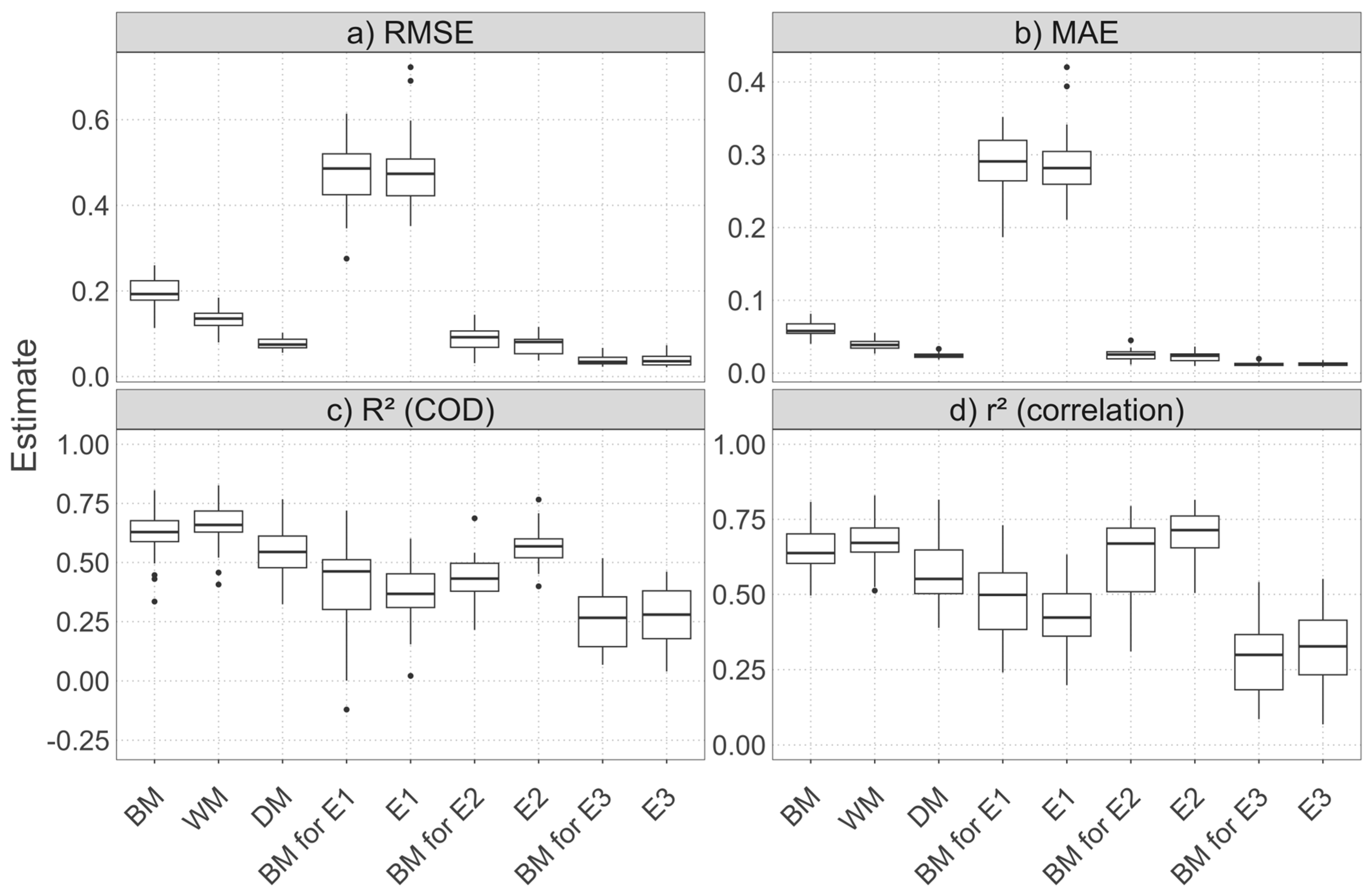

Figure 6.

Boxplot of performance metrics obtained by random cross-validation. The MAE, RMSE, R² and r² values were calculated on the test sets on the MIR scale after performing a random 5-repeated 5-fold cross-validation procedure. The R² is the coefficient of determination (COD) and the r² is the square of the correlation between the observed and predicted values. The middle horizontal line represents the median, while the dots represent outliers. Abbreviations: RMSE (root mean square error), MAE (mean absolute error), COD (coefficient of determination), BM (benchmark model), WM (wet season model), DM (dry season model), E1 (endemicity 1 model), E2 (endemicity 2 model), E3 (endemicity 3 model).

Figure 6.

Boxplot of performance metrics obtained by random cross-validation. The MAE, RMSE, R² and r² values were calculated on the test sets on the MIR scale after performing a random 5-repeated 5-fold cross-validation procedure. The R² is the coefficient of determination (COD) and the r² is the square of the correlation between the observed and predicted values. The middle horizontal line represents the median, while the dots represent outliers. Abbreviations: RMSE (root mean square error), MAE (mean absolute error), COD (coefficient of determination), BM (benchmark model), WM (wet season model), DM (dry season model), E1 (endemicity 1 model), E2 (endemicity 2 model), E3 (endemicity 3 model).

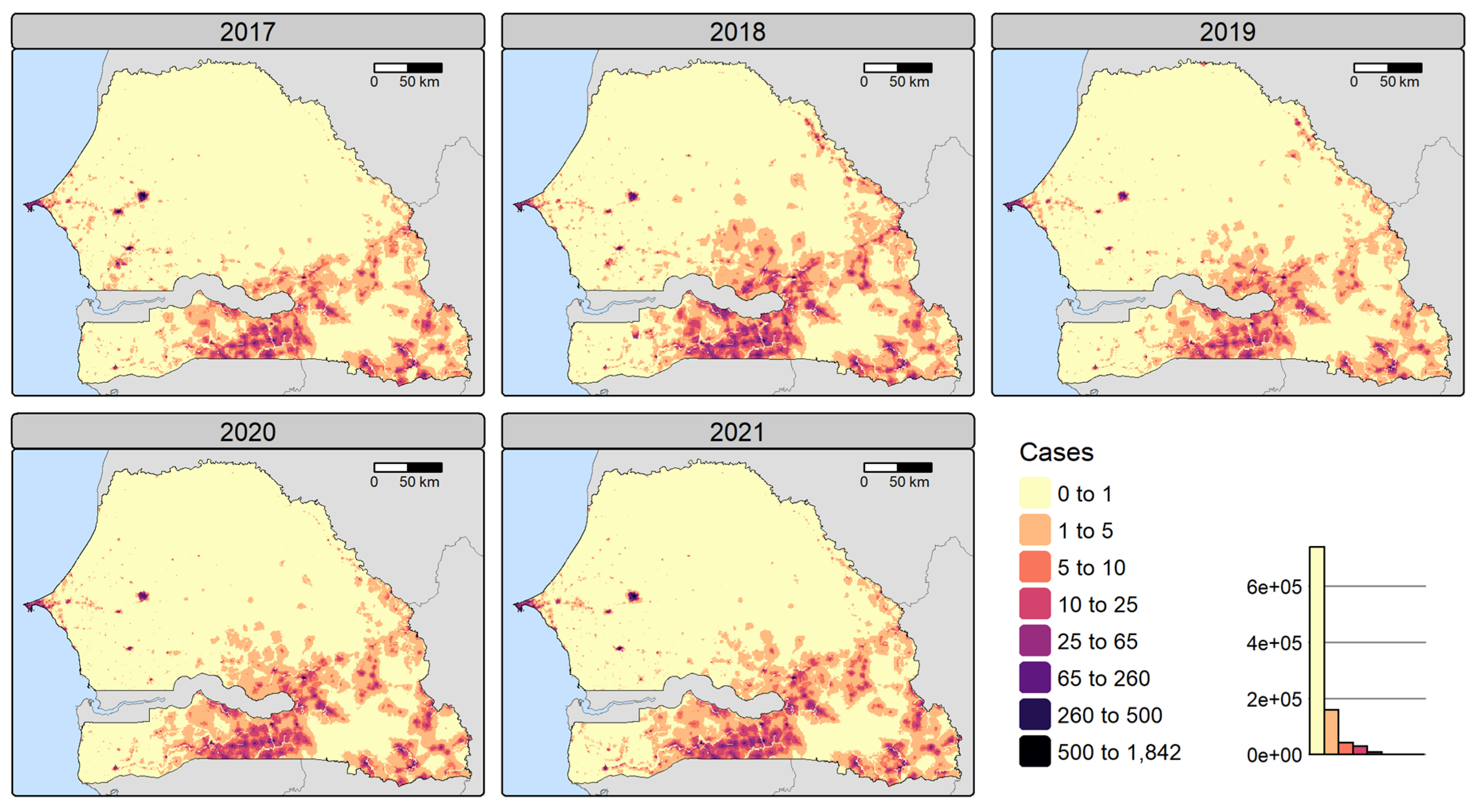

Figure 7.

Disaggregated reported malaria cases for 2017-2021 at 1x1 km resolution. The number of cases per pixel was obtained by a dasymetric disaggregation of the number of reported cases per health facility catchment area, using the posterior mean malaria incidence rate per pixel to compute the disaggregation weight. These estimates are based on the benchmark model.

Figure 7.

Disaggregated reported malaria cases for 2017-2021 at 1x1 km resolution. The number of cases per pixel was obtained by a dasymetric disaggregation of the number of reported cases per health facility catchment area, using the posterior mean malaria incidence rate per pixel to compute the disaggregation weight. These estimates are based on the benchmark model.

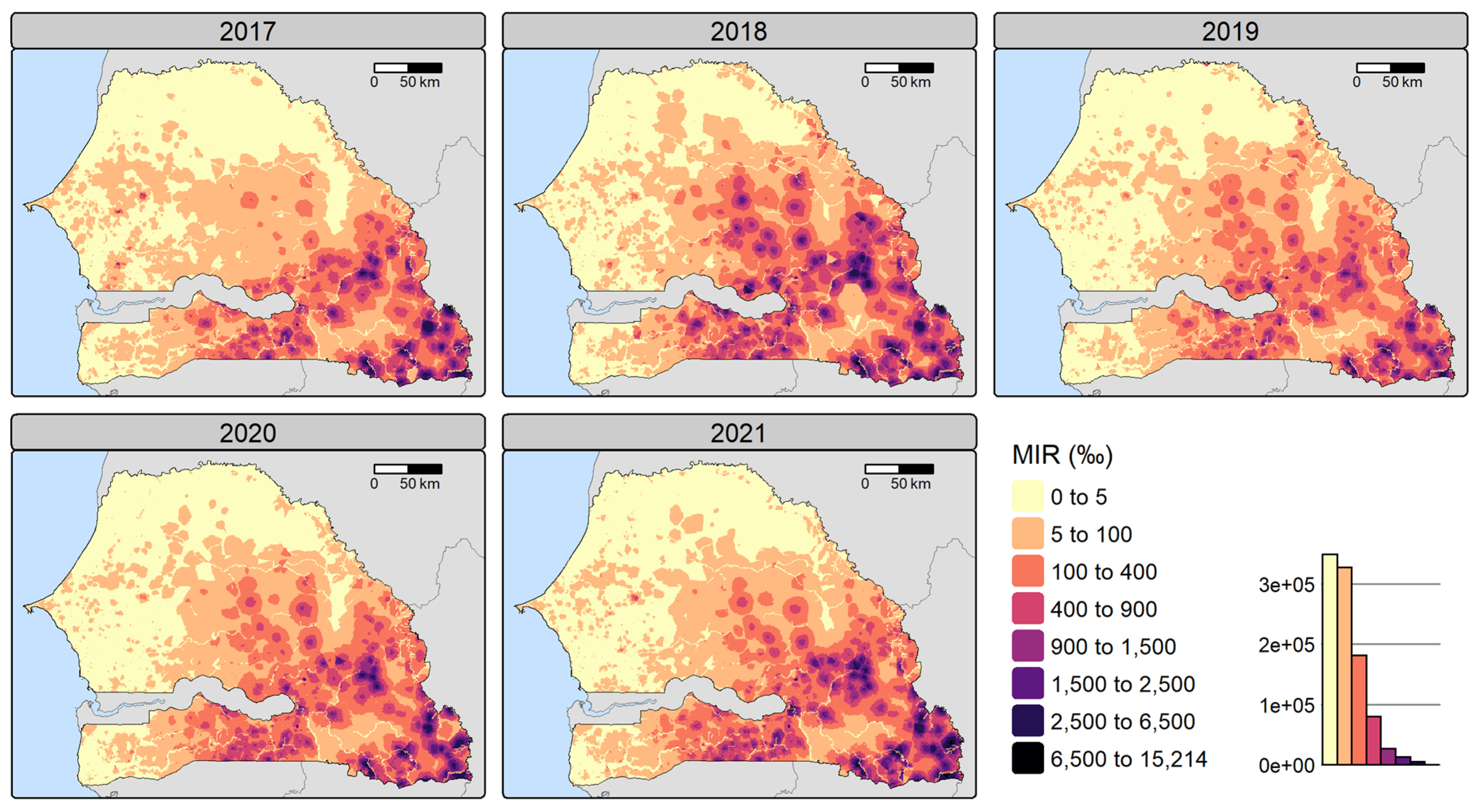

Figure 8.

Disaggregated malaria incidence rate (per 1,000 people) for 2017-2021 at 1x1 km resolution. Malaria incidence rates (MIR) were calculated by dividing the number of cases per pixel obtained by dasymetric disaggregation by the pixel treatment-seeking population. These estimates are based on the benchmark model. Note that incidence rates above 1000‰ can be attributed to malaria repeat episodes [

32] and migration.

Figure 8.

Disaggregated malaria incidence rate (per 1,000 people) for 2017-2021 at 1x1 km resolution. Malaria incidence rates (MIR) were calculated by dividing the number of cases per pixel obtained by dasymetric disaggregation by the pixel treatment-seeking population. These estimates are based on the benchmark model. Note that incidence rates above 1000‰ can be attributed to malaria repeat episodes [

32] and migration.

Table 1.

Geospatial covariates and their characteristics.

Table 1.

Geospatial covariates and their characteristics.

| Category |

Variables |

Date |

Spatial resolution |

Source |

| Climate & weather |

Precipitation |

Climatic average over 1988-2018 |

1000 m |

CHELSA [54] (https://chelsa-climate.org/) |

| Day land surface temperature (LST), night LST |

Annual (2017-2021) |

1000 m |

MODIS [55,56] (http://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/) |

| Vector-habitat |

Normalized difference moisture index (NDMI) |

Annual (2017-2021) |

10 m |

Computed from Sentinel-2 L1C composites of the Joint Research Centre (JRC) [57] (https://forobs.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sentinel/sentinel2_composite) |

| Land use and land cover: water, trees, flooded vegetation, cropland, grassland, bare land, shrubland, built-up |

Annual (2017-2021) |

10 m |

Dynamic World by Google and the World Resources Institute [58] (https://dynamicworld.app/) |

| Elevation |

2000 |

30 m |

US Geological Survey [59] (http://eros.usgs.gov/elevation-products) |

| Susceptibility |

Access to basic sanitation service, proportion of Fula, stunting in children |

Annual (2017-19/20 avail.; stunting: 2020-21 proj., others: 2021 proj.) |

Survey clusters |

The DHS Program |

| Lack of resilience |

Distance to major roads |

2023 |

100 m |

OpenStreetMap (www.openstreetmap.org) |

| Walking-only travel time to health facilities |

Annual (2017-2021) |

1000 m |

Walking time is computed using elevation, land use, roads and rivers (see Section Computation of travel time) |

| Ownership of insecticide-treated nets, literacy rate in women |

Annual (2017-20 avail.; 2021 proj.) |

Survey clusters |

The DHS Program |

Table 2.

Land and road type and associated walking speed in km/h.

Table 2.

Land and road type and associated walking speed in km/h.

| Data source |

Land and road type |

Walking speed (km/h) |

| Dynamic World LULC |

Built up |

5 |

| Trees |

3.5 |

| Shrubland |

4.5 |

| Cropland |

3.5 |

| Grassland |

4 |

| Bare ground |

5 |

| Flooded vegetation |

0 |

| Water bodies |

0 |

| OpenStreetMap |

Rivers |

0 |

| Roads |

5 |

Table 3.

Model names and their descriptions.

Table 3.

Model names and their descriptions.

| Model name |

Description |

Number of facilities |

| Benchmark model (BM) |

|

1472 (1389) |

| Wet season model (WM) |

|

1472 (1389) |

| Dry season model (DM) |

|

1472 (1389) |

| Endemicity 1 model (E1) |

|

217 (216) |

| Endemicity 2 model (E2) |

|

373 (328) |

| Endemicity 3 model (E3) |

|

882 (845) |

Table 4.

Covariates selected by Bayesian geostatistical models. .

Table 4.

Covariates selected by Bayesian geostatistical models. .

| Category |

Variable |

BM |

WM |

DM |

E1 |

E2 |

E3 |

Number of models |

| Climate & weather |

Precipitation |

|

|

|

(⨯) |

⨯ |

(⨯) |

3 |

| Day LST |

⨯ |

⨯ |

|

⨯ |

|

⨯ |

4 |

| Night LST |

⨯ |

⨯ |

|

|

|

|

2 |

| Vector-habitat |

NDMI |

|

|

|

⨯ |

(⨯) |

|

2 |

| Prop. of bare land |

|

(⨯) |

|

|

⨯ |

⨯ |

3 |

| Prop. of built-up |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

6 |

| Prop. of cropland |

(⨯) |

|

(⨯) |

|

⨯ |

|

3 |

| Prop. of flooded vegetation |

|

⨯ |

|

(⨯) |

|

|

2 |

| Prop. of shrubland |

|

⨯ |

|

⨯ |

|

|

2 |

| Prop. of trees |

⨯ |

|

⨯ |

|

|

|

2 |

| Prop. of water |

|

|

|

⨯ |

|

|

1 |

| Elevation |

|

|

⨯ |

|

⨯ |

|

2 |

| Susceptibility |

Access to basic sanitation |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

|

|

⨯ |

4 |

| Prop. of Fula |

|

|

|

|

⨯ |

|

1 |

| Stunting in children |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

6 |

| Lack of resilience |

Distance to major roads |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

|

|

⨯ |

4 |

| Walking time to health facilities |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

⨯ |

6 |

| |

Number of covariates |

9 |

10 |

8 |

9 |

9 |

8 |

/ |

Table 5.

Posterior estimates of the benchmark model and models stratified by season.

Table 5.

Posterior estimates of the benchmark model and models stratified by season.

| Variable |

Benchmark (BM) |

Wet season (WM) |

Dry season (DM) |

| Mean |

2.5% quant. |

97.5% quant. |

Mean |

2.5% quant. |

97.5% quant. |

Mean |

2.5% quant. |

97.5% quant. |

|

) |

-3.61 |

-4.40 |

-2.82 |

-4.00 |

-4.72 |

-3.28 |

-4.37 |

-5.12 |

-3.62 |

| Day LST |

-0.37 |

-0.50 |

-0.23 |

-0.34 |

-0.48 |

-0.19 |

- |

- |

- |

| Night LST |

0.26 |

0.15 |

0.37 |

0.24 |

0.13 |

0.36 |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of bare land |

- |

- |

- |

0.003 |

-0.08 |

0.07 |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of built-up |

0.57 |

0.52 |

0.62 |

0.51 |

0.44 |

0.58 |

0.63 |

0.58 |

0.67 |

| Prop. of cropland |

0.02 |

-0.03 |

0.07 |

- |

- |

- |

0.04 |

-0.01 |

0.10 |

| Prop. of flooded vegetation |

- |

- |

- |

-0.10 |

-0.16 |

-0.05 |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of shrubland |

- |

- |

- |

-0.11 |

-0.19 |

-0.02 |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of trees |

0.11 |

0.05 |

0.17 |

- |

- |

- |

0.15 |

0.09 |

0.22 |

| Elevation |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

-0.13 |

-0.23 |

-0.03 |

| Access to basic sanitation |

0.23 |

0.16 |

0.30 |

0.25 |

0.18 |

0.32 |

0.18 |

0.11 |

0.25 |

| Stunting in children |

0.26 |

0.17 |

0.35 |

0.29 |

0.20 |

0.37 |

0.25 |

0.16 |

0.33 |

| Distance to major roads |

-0.19 |

-0.25 |

-0.13 |

-0.12 |

-0.18 |

-0.06 |

-0.13 |

-0.19 |

-0.07 |

| Walking time to health facilities |

-0.35 |

-0.41 |

-0.28 |

-0.34 |

-0.41 |

-0.28 |

-0.38 |

-0.45 |

-0.31 |

| Precision of uncorrelated random variations ( |

1.12 |

1.08 |

1.17 |

1.17 |

1.13 |

1.22 |

1.09 |

1.05 |

1.13 |

|

) |

2.16a

|

1.71 |

2.73 |

2.22b

|

1.74 |

2.76 |

2.01c

|

1.59 |

2.53 |

| SD of spatially correlated variations ( |

2.78 |

2.22 |

3.46 |

2.53 |

2.00 |

3.10 |

2.57 |

2.06 |

3.19 |

|

) |

0.99 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.98 |

0.97 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

Table 6.

Posterior estimates of the models stratified by endemicity level. .

Table 6.

Posterior estimates of the models stratified by endemicity level. .

| Variable |

Endemicity 1 |

Endemicity 2 |

Endemicity 3 |

| Mean |

2.5% quant. |

97.5% quant. |

Mean |

2.5% quant. |

97.5% quant. |

Mean |

2.5% quant. |

97.5% quant. |

|

) |

-1.24 |

-2.20 |

-0.32 |

-5.98 |

-7.24 |

-4.72 |

-4.56 |

-5.44 |

-3.67 |

| Precipitation |

0.45 |

-0.06 |

0.96 |

1.64 |

0.95 |

2.34 |

0.17 |

-0.05 |

0.38 |

| Day LST |

-1.60 |

-2.08 |

-1.12 |

- |

- |

- |

-0.14 |

-0.26 |

-0.02 |

| NDMI |

-0.50 |

-0.70 |

-0.30 |

0.17 |

-0.08 |

0.42 |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of bare land |

- |

- |

- |

0.22 |

0.09 |

0.35 |

-0.08 |

-0.15 |

-0.02 |

| Prop. of built-up |

0.43 |

0.28 |

0.58 |

0.63 |

0.52 |

0.75 |

0.53 |

0.46 |

0.60 |

| Prop. of cropland |

- |

- |

- |

0.35 |

0.20 |

0.50 |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of flooded vegetation |

1.15 |

-0.22 |

2.53 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of shrubland |

-0.38 |

-0.50 |

-0.26 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Prop. of water |

-1.23 |

-1.76 |

-0.69 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Elevation |

- |

- |

- |

-0.58 |

-0.95 |

-0.21 |

- |

- |

- |

| Access to basic sanitation |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.18 |

0.09 |

0.27 |

| Prop. of Fula |

- |

- |

- |

-0.31 |

-0.59 |

-0.04 |

- |

- |

- |

| Stunting in children |

0.40 |

0.26 |

0.54 |

0.32 |

0.09 |

0.54 |

0.25 |

0.14 |

0.37 |

| Distance to major roads |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

-0.21 |

-0.28 |

-0.14 |

| Walking time to health facilities |

-0.23 |

-0.30 |

-0.16 |

-1.84 |

-2.17 |

-1.51 |

-0.36 |

-0.45 |

-0.27 |

| Precision of uncorrelated random variations ( |

2.27 |

2.05 |

2.50 |

1.02 |

0.95 |

1.10 |

1.15 |

1.09 |

1.20 |

|

) |

1.74a

|

1.13 |

2.57 |

0.91b

|

0.59 |

1.40 |

2.17c

|

1.59 |

2.87 |

| SD of spatially correlated variations ( |

1.58 |

1.10 |

2.21 |

1.80 |

1.31 |

2.46 |

2.46 |

1.83 |

3.21 |

|

) |

0.97 |

0.95 |

0.99 |

0.97 |

0.94 |

0.99 |

0.98 |

0.96 |

0.99 |

Table 7.

Mean performance metrics (MAE, RMSE, R² and r²) obtained by cross-validation (MIR scale). .

Table 7.

Mean performance metrics (MAE, RMSE, R² and r²) obtained by cross-validation (MIR scale). .

| Random CV |

RMSE |

MAE |

R² (COD) |

r² (corr.) |

| Benchmark (BM) |

0.20 |

0.06 |

0.62 |

0.65 |

| BM for E1 |

0.47 |

0.29 |

0.40 |

0.48 |

| BM for E2 |

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.43 |

0.60 |

| BM for E3 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.26 |

0.29 |

| Wet season (WM) |

0.13 |

0.04 |

0.65 |

0.67 |

| Dry season (DM) |

0.08 |

0.02 |

0.54 |

0.56 |

| Endemicity 1 (E1) |

0.48 |

0.29 |

0.37 |

0.43 |

| Endemicity 2 (E2) |

0.08 |

0.02 |

0.57 |

0.69 |

| Endemicity 3 (E3) |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.27 |

0.32 |

| Temporal block CV |

RMSE |

MAE |

R² (COD) |

r² (corr.) |

| Benchmark (BM) |

0.17 |

0.05 |

0.70 |

0.75 |

| BM for E1 |

0.41 |

0.25 |

0.55 |

0.65 |

| BM for E2 |

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.44 |

0.63 |

| BM for E3 |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.19 |

0.30 |

| Wet season (WM) |

0.13 |

0.04 |

0.66 |

0.77 |

| Dry season (DM) |

0.07 |

0.02 |

0.63 |

0.66 |

| Endemicity 1 (E1) |

0.41 |

0.24 |

0.55 |

0.64 |

| Endemicity 2 (E2) |

0.08 |

0.03 |

0.49 |

0.68 |

| Endemicity 3 (E3) |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.20 |

0.31 |