1. Introduction

Pediatric palliative care (PPC) is a holistic, interdisciplinary approach aimed at improving the quality of life of children with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions and their families, through comprehensive physical, emotional, psychosocial, and spiritual support [Benini 2022]. Among the pediatric population requiring PPC, a substantial proportion are affected by non-oncological diseases, particularly serious neurological conditions such as congenital brain disorders, progressive neurodegenerative diseases, and severe acquired brain injuries [Benini 2022; Schiavon 2024]. These patients often experience prolonged, dynamic trajectories of care characterized by complex clinical needs, cognitive and communicative impairments, and significant prognostic uncertainty [Woodgate 2024].

In response to these specific challenges, the emerging discipline of neuropalliative care has evolved. Neuropalliative care focuses on the holistic needs of children with serious neurological illnesses, encompassing symptom management, quality of life optimization, anticipatory decision-making support, and goal-concordant care throughout the disease course [Lau 2025]. The Consensus Statement from the International Neuropalliative Care Society underscores the critical need to develop tailored communication frameworks and care delivery models specifically adapted to the unique trajectories and needs of children with neurologic conditions [Lau 2025].

Communication in PPC must recognize the profound impact of cultural, religious, and spiritual belief systems on families’ understanding of illness, suffering, and medical decision-making [Wiener 2013; Puchalski 2003]. Such beliefs significantly shape perspectives on prognosis disclosure, perceived suffering, end-of-life decision-making roles, and definitions of quality of life [Davies 2002; Hexem 2011]. Particularly in multicultural societies, culturally humble communication—characterized by respect, open inquiry, and genuine curiosity about families’ worldviews—is essential for fostering trust and therapeutic alliances [Puchalski 2003; Lin 2024]. Importantly, spirituality should not be regarded merely as a religious phenomenon, but rather as an integral dimension of meaning-making and coping for families navigating pediatric serious illness [Davies 2002; Hexem 2011].

Recent evidence increasingly emphasizes that PPC delivery must be responsive to the cultural and existential values of all families, irrespective of traditional notions of minority status [Rent 2023; Rosenberg 2019]. Disparities in palliative care have been documented even in well-resourced settings, reflecting the urgent need for communication practices that adapt to the diversity of beliefs and experiences among pediatric patients and their families [Burke 2023; Redman 2024].

This review aims to synthesize available evidences on communication strategies in pediatric palliative and neuropalliative care, with particular attention to cultural, spiritual, and religious considerations. We explore conceptual foundations, cross-cultural variations, ethical issues, and emerging best practices, with the ultimate goal of supporting the development of culturally inclusive and individualized communication models for children with life-limiting neurological conditions and their families.

2. Methods

A narrative review approach was adopted to synthesize the current evidence regarding communication practices in PPC, with particular attention to children with severe neurological conditions and to the influence of cultural, religious, and spiritual factors.

The literature search was finalized in April 2025 and was conducted across major biomedical databases, including PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and CINAHL. Manual searches of references from key articles and guidelines were also performed to ensure completeness. The following search string was used as the primary query across databases:

(((((complex chronic conditions) OR (complex care needs)) AND (pediatric palliative care)) AND (spirituality)) OR (religious beliefs)) AND (cultural diversity)

Searches were restricted to articles published in English, without time constraints. Both original research studies (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods) and review articles were considered eligible if they explored aspects of communication, cultural diversity, spirituality, religious beliefs, or decision-making in pediatric palliative care contexts. Particular emphasis was placed on studies involving children with complex chronic conditions, especially neurological diseases, given their prevalence within PPC populations.

Additionally, grey literature such as consensus statements, professional guidelines, and conference proceedings was screened to capture emerging best practices. Articles focusing exclusively on adult palliative care populations, unrelated to communication or cultural diversity issues, were excluded.

Throughout the screening process, priority was given to publications from 2010 onward to reflect the most contemporary understanding, although landmark papers prior to this date were included if deemed foundational.

3. Conceptual Foundations of Cross-Cultural Communication in Pediatric Palliative Care

Effective communication lies at the heart of PPC, ensuring that families’ values, beliefs, and preferences are honored alongside medical goals. In cross-cultural settings, communication must address not only informational needs but also the diverse spiritual, cultural, and social frameworks that shape families’ experiences of illness, suffering, and decision-making.

Culture, defined as the learned and shared patterns of behavior, beliefs, and values within groups, profoundly impacts health perceptions and healthcare interactions. In PPC, culture influences every stage of care: from diagnosis to end-of-life decisions and bereavement practices. Recognizing this, culturally humble communication—emphasizing openness, respect, and a genuine curiosity toward others’ worldviews—has become a foundational principle.

However, communication across cultures often encounters barriers. Language differences, varying concepts of illness and death, differing expectations of truth-telling, and assumptions about decision-making authority can cause tensions. Healthcare providers may unintentionally impose their own cultural norms, reinforcing systemic inequities. Fear of causing offense and lack of formal training in cultural humility exacerbate these challenges. Moreover, families’ understanding of palliative care itself may be shaped by sociocultural narratives that differ significantly from Western medical models.

Spirituality is another essential dimension. As highlighted by Davies et al. [Davies 2002], addressing children’s spiritual needs is a core component of total care, yet often remains underexplored. Parents draw on a wide range of religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs when facing their child’s illness. These beliefs may influence their acceptance of prognosis, interpretations of suffering, and views on medical interventions. For some, spirituality provides profound comfort and meaning; for others, it introduces complex tensions.

Importantly, culturally sensitive communication must avoid simplistic categorizations. Families are not monolithic, and intra-group variation can be considerable. Attention must be paid to intersectionality, recognizing that cultural identity interacts with factors such as socioeconomic status, education level, migration history, and prior healthcare experiences. As emphasized by Rosenberg et al. [Rosenberg 2019], building trust requires acknowledging these complex layers, addressing systemic power imbalances, and fostering individualized, respectful dialogue.

Lastly, a growing body of literature stresses that cultural humility is not a fixed competence, but an ongoing process of self-reflection, learning, and relationship-building. It demands that practitioners engage families with openness, acknowledge uncertainty, and adapt communication styles to support authentic, goal-concordant care across diverse cultural landscapes.

4. Cultural Differences Shaping Communication in Pediatric Palliative Care

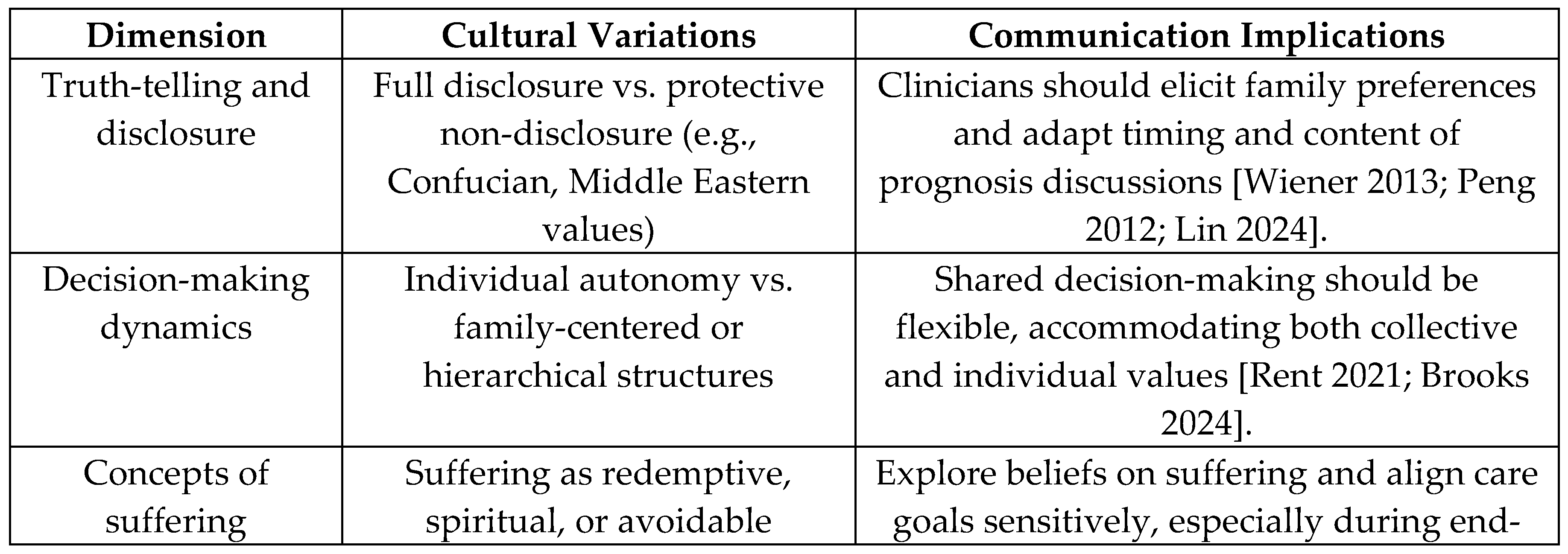

Communication practices in PPC are significantly shaped by cultural, linguistic, spiritual, and systemic factors. Cultural, religious, and linguistic dimensions interact in nuanced ways, shaping each family’s expectations and responses to care (

Table 1).

However, it must be recognized that the vast majority of available evidence stems predominantly from oncological contexts, with fewer studies focusing specifically on children with neurological conditions. Extrapolation to broader PPC populations must therefore be undertaken cautiously, with attention to disease-specific and culturally nuanced realities.

4.1. Language and Interpretation Challenges

Language barriers remain one of the most consistent obstacles to effective communication in PPC. Professional interpreters are underutilized, with interpreter services documented in fewer than 5% of critical conversations with culturally diverse families [Brooks 2024]. Rent et al. [Rent 2021] found that limited language proficiency significantly hampers prognostic understanding and increases emotional distress in families.

Informal interpretation by family members can introduce inaccuracies and emotional strain [Islam 2023; Brooks 2025]. In addition, misunderstandings are compounded by cultural variations in non-verbal communication and relational hierarchies [O’Neill 2025]. Monette [Monette 2021] and Upshaw et al. [Upshaw 2021] stressed the importance of integrating professional interpretation with culturally sensitive communication strategies. Addressing these barriers demands not only access to interpreters but also clinician training in culturally responsive engagement [Pentaris 2020; Bruun 2025].

4.2. Truth-Telling, Prognosis Disclosure, and Decision-Making

Truth-telling and prognosis disclosure practices vary widely across cultures. In Western medical ethics, direct and transparent disclosure is prioritized. However, many non-Western cultural frameworks endorse protective non-disclosure as a compassionate practice [Wiener 2013; Thorvilson 2019].

Peng et al. [Peng 2012] reported that in Taiwan, families often prefer not to disclose terminal diagnoses to children, reflecting Confucian values of familial harmony. Lin et al. [Lin 2024] further discussed that Chinese cultural norms discourage explicit discussions about death, often leading to misinterpretations of medical information. Lai et al. [Lai 2014] similarly emphasized that cultural beliefs about death and dying significantly shape family decisions regarding information sharing.

Thorvilson et al. [Thorvilson 2019] demonstrated how facilitating culturally congruent palliative transport enabled families to incorporate traditional rituals into the dying process, illustrating how cultural norms influence both communication and end-of-life care preferences.

Clinicians are thus encouraged to explore individual family preferences regarding disclosure early in the care trajectory, utilizing flexible, culturally sensitive models of communication that balance transparency with respect for family values.

4.3. Religion, Spirituality, and Cultural Contexts

Spirituality and religious beliefs are central to end-of-life decision-making for many families, yet wide diversity exists within and across faith traditions. Puchalski [Puchalski 2003] emphasized that although spirituality has been increasingly recognized , research remains limited and needs strengthening to support evidence-based spiritual care practices.

Pereira-Salgado et al. [Pereira 2017] showed that religious leaders across multiple faiths view advance care planning (ACP) favorably once adequately understood, but stressed the necessity of avoiding assumptions based on religious affiliation alone. Families’ attitudes towards end-of-life care reflect intersecting influences of personal religiosity, cultural traditions, family dynamics, and individual beliefs.

Al Mutair et al. [Al Mutair 2019] illustrated that among Muslim families, interpretations of divine will vary, affecting preferences for life-sustaining interventions. Similarly, Sansom-Daly et al. [Sansom 2023] found that adolescents and young adults experience varying degrees of stress related to discussing spirituality during ACP, underscoring the need for individualized approaches.

Clinicians are urged to maintain openness, avoiding stereotyping based on apparent religious identity, and should integrate exploration of spiritual needs into routine palliative care discussions.

4.4. Broader Systemic and Structural Barriers

Beyond interpersonal communication challenges, systemic inequities and structural barriers also impact PPC delivery. Islam et al. [Islam 2023] and Mach et al. [Mach 2020] emphasized that minority families often experience mistrust of healthcare systems, feelings of marginalization, and a lack of culturally congruent care options.

Institutional inflexibility, lack of cultural humility training, and poor adaptation of palliative care frameworks to diverse needs have been recurrently identified as barriers [Pentaris 2020; Lombardi 2024; O’Neill 2025]. Upshaw et al. [Upshaw 2021] stressed that cultural, developmental, and support structure considerations must be integral part of PPC and ACP for adolescents and young adults; they navigate complex intersections of autonomy, family involvement, and cultural values.

Efforts toward fostering cultural safety—through organizational change, clinician education, and systematic accommodation of diverse needs—are essential to improve equitable communication and care in PPC. These cultural, religious, and linguistic dimensions interact in nuanced ways, shaping each family’s expectations and responses to care. A summary of the key cross-cultural variables and their implications for PPC communication is presented in

Table 1.

5. Communication in Neurologically Ill Children: Special Challenges

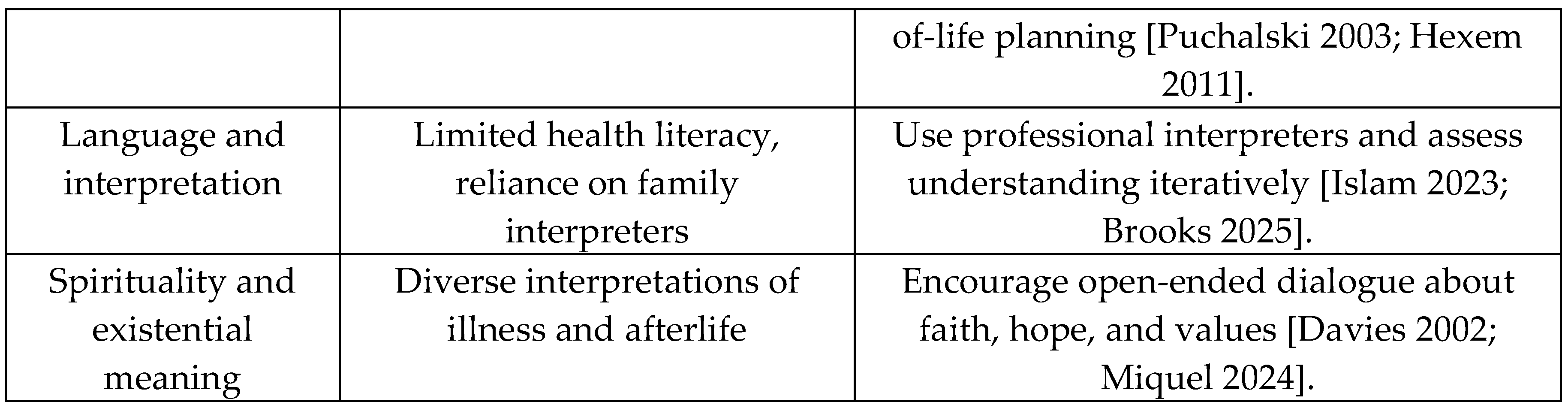

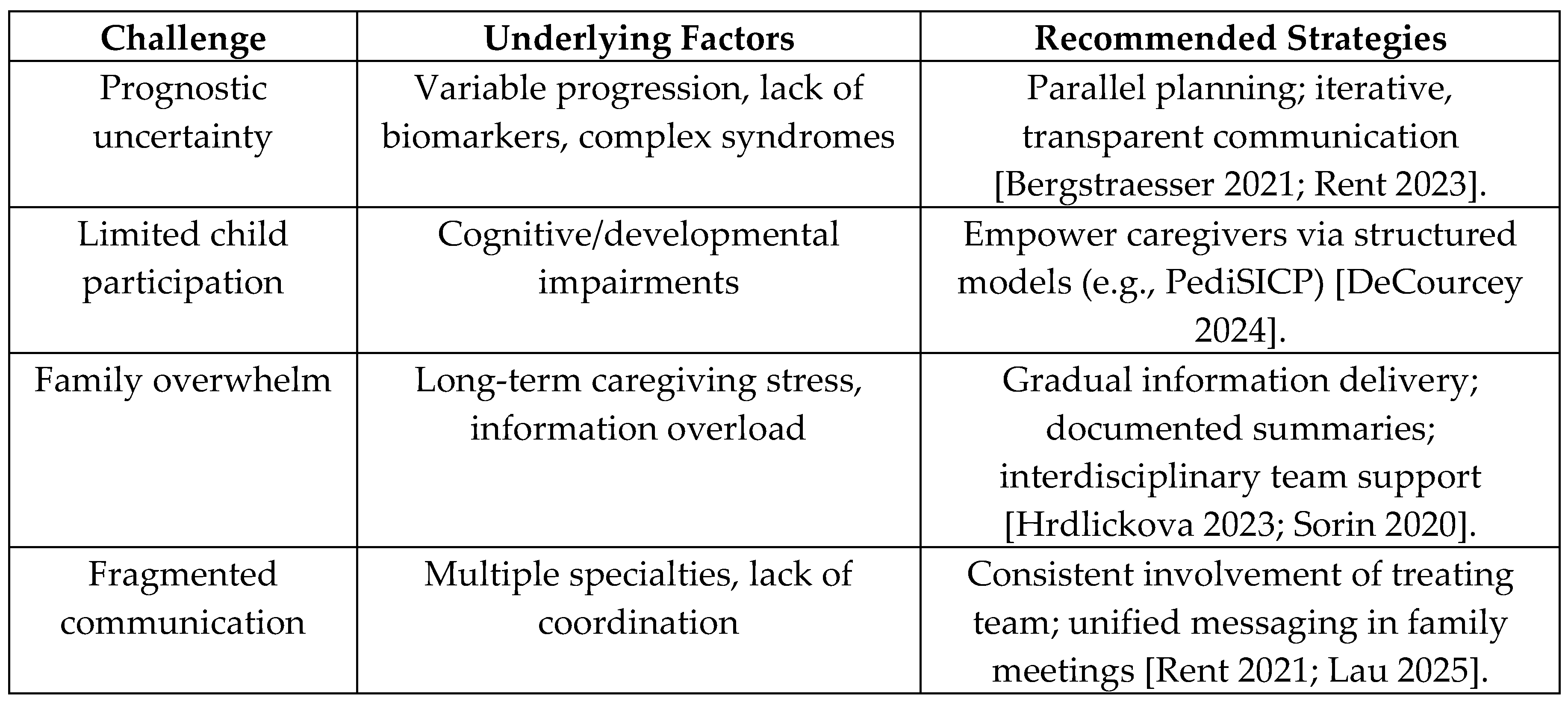

Communication in the care of neurologically ill children is uniquely shaped by prognostic ambiguity, developmental limitations, interdisciplinary fragmentation, and ethical complexity. These challenges require structured, longitudinal, and ethically responsive models of care (

Table 2).

5.1. Prognostic Uncertainty and Evolving Dialogue

Children with serious neurological illnesses often experience prolonged and complex trajectories marked by diagnostic uncertainty, variable clinical progression, and profound developmental challenges.

Prognostication in these conditions is inherently uncertain and evolves over time. Traditional focus on life expectancy is insufficient; clinicians must also explore dimensions such as functional potential, comfort, communication capacity, and quality of life. Bergstraesser et al. emphasized that discussions around prognosis should move beyond “how long” toward “what will life look like,” integrating families’ values and long-term hopes for their children [Bergstraesser 2021].

This approach aligns with principles of parallel planning—simultaneously preparing for both the best and worst outcomes—particularly valuable in perinatal and neonatal settings where outcome trajectories are difficult to predict [Rent 2023; Bergstraesser 2021]. Such nuanced discussions benefit from early, iterative engagement that validates uncertainty and fosters a collaborative therapeutic alliance between the care team and the family [Lau 2025].

5.2. Enhancing Family Engagement through Structured Models

Given that many neurologically affected children lack capacity for direct participation in care decisions, effective family engagement is paramount. Structured communication models like the Pediatric Serious Illness Communication Program (PediSICP) have demonstrated feasibility and benefit in this context. DeCourcey et al. found that PediSICP facilitated more goal-aligned care, improved therapeutic alliance, and reduced parental anxiety—even in scenarios marked by clinical ambiguity, such as neurodevelopmental conditions [DeCourcey 2024].

Such models encourage the co-creation of care plans grounded in what matters most to families and support shared decision-making even in the face of prognostic uncertainty. They enable anticipatory guidance while respecting families’ coping rhythms and cognitive readiness [Lau 2025; Wiener 2013].

These findings echo the need, underscored in the International Neuropalliative Care Society’s consensus, for specialized tools and training that support communication tailored to neuro-complex populations [Lau 2025]. Such structured approaches promote alignment between medical goals and family priorities across diverse cultural and clinical landscapes.

5.3. Communication Models in NICU and Progressive Neurological Conditions

In neonatal and early childhood settings, communication challenges are further intensified by time-sensitive decisions, fragmented care structures, and emotional distress. Rent et al. noted that the NICU environment often includes multiple rotating teams, which can lead to inconsistent messaging and parental confusion [Rent 2021; Rent 2023]. Addressing this requires deliberate coordination and continuity, ideally through family-centered team meetings and shared care planning.

Hrdličková et al. demonstrated that including the primary treating team in initial palliative consultations significantly enhances parental trust, improves interdisciplinary coherence, and provides critical psychosocial insights [Hrdlickova 2023]. Their study also highlighted the novel practice of inviting parental feedback on the written summary of these meetings—an innovation that fosters family empowerment and narrative integrity.

Meanwhile, communication in progressive neurological conditions should be framed as a longitudinal process. Lau et al. call for developing adaptable models that evolve with the child’s condition, allowing care teams to revisit and reframe goals across disease stages [Lau 2025]. Importantly, documentation of decisions and values over time can bridge transitions between inpatient, outpatient, and home-based care settings, facilitating consistency and preparedness.

Spiritual and cultural beliefs deeply shape how families perceive disability, suffering, and end-of-life choices. As highlighted by Wiener et al., culturally humble communication should avoid prescriptive assumptions and prioritize open inquiry into each family’s worldview [Wiener 2013]. This is particularly important when discussing interventions such as tracheostomy or long-term mechanical ventilation, which may evoke existential or moral considerations beyond biomedical risk-benefit analysis [Hrdlickova 2023; Rent 2023].

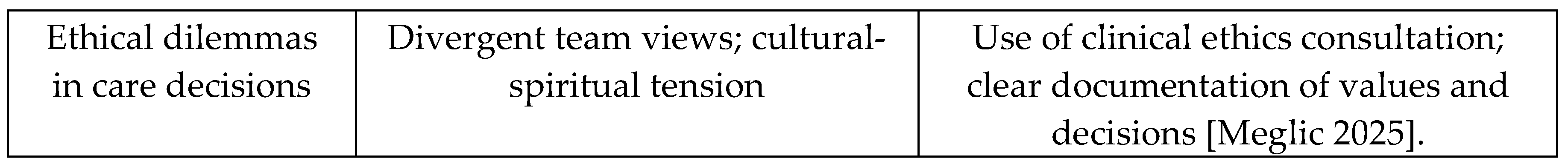

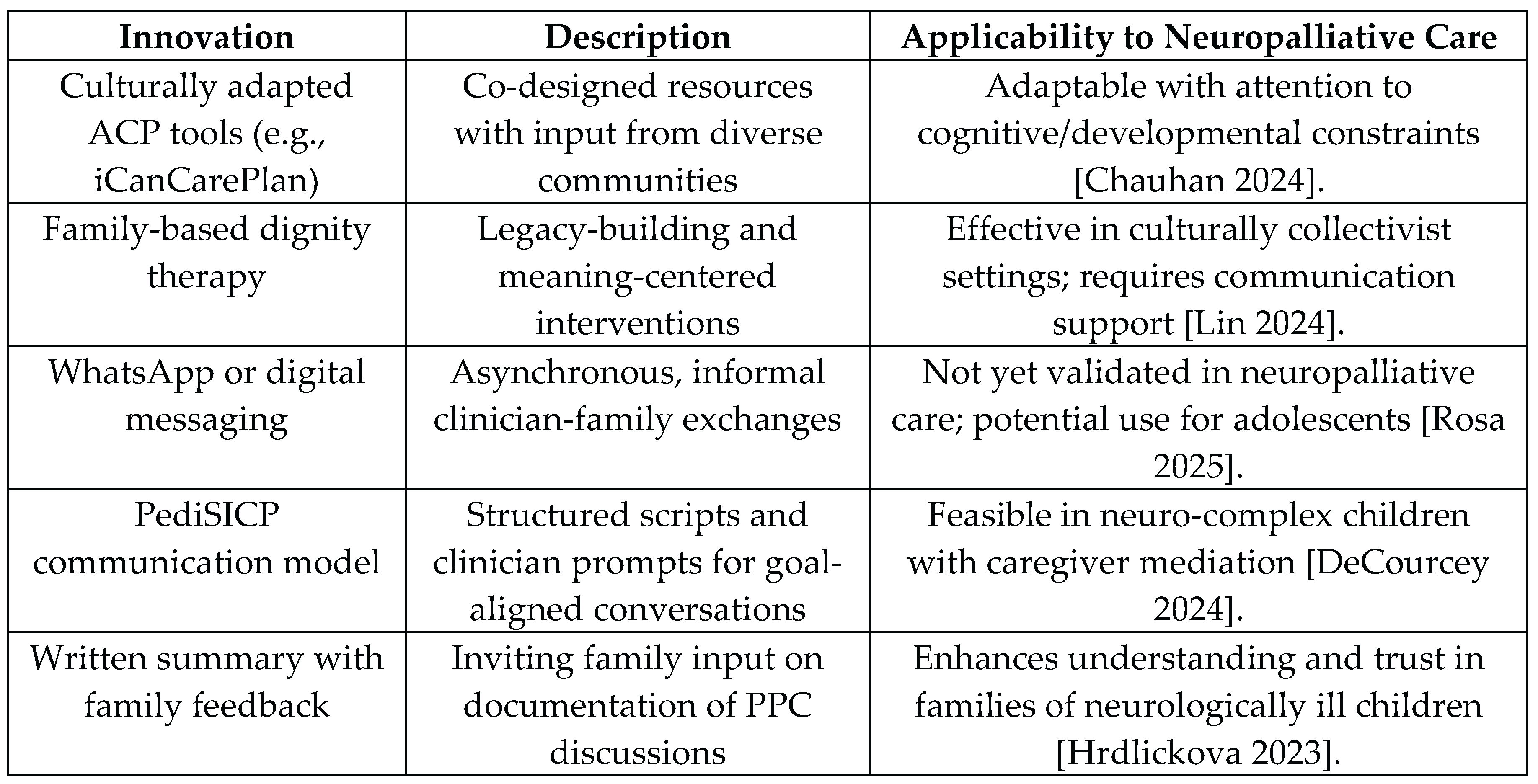

6. Innovations and Best Practices in Cross-Cultural Pediatric Palliative Communication

Communication strategies in PPC must continually evolve to meet the complex needs of children and families from diverse cultural backgrounds. Recent innovations have focused on promoting cultural sensitivity, improving accessibility, and fostering family-centered and ethically grounded models. A comparative overview of recent innovations—including co-designed ACP tools, digital communication platforms, and structured communication protocols—is provided in

Table 3, with a focus on their applicability to neuropalliative care contexts.

A critical development has been the increasing use of co-designed tools for advance care planning (ACP) among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations. Chauhan et al. [Chauhan 2024] highlighted that direct translation of ACP resources often fails to capture the nuanced cultural and religious variations that influence end-of-life preferences. Their iCanCarePlan study emphasizes the importance of culturally adapted ACP materials and co-design approaches that involve stakeholders from CALD backgrounds in creating communication tools, rather than merely translating existing frameworks. This method ensures respect for diverse conceptualizations of illness, autonomy, and family roles in decision-making.

Similarly, Burke et al. [Burke 2023] emphasized the need to enhance healthcare practitioners’ cultural competence. Their systematic review demonstrated that communication challenges in palliative care frequently stem from language difficulties, fear of cultural insensitivity, and differing expectations regarding truth-telling and family involvement. They advocate for individualized communication strategies, continuous cultural humility education, and institutional support for culturally responsive care.

Innovative frameworks have also incorporated family-centered dignity therapy to strengthen relational bonds at the end of life. Lin et al. [Lin 2024] developed a pediatric family-based dignity therapy protocol specifically adapted for Chinese cultural contexts. By involving families in structured, meaningful conversations and preserving these memories, the intervention supports psychological resilience and acknowledges the centrality of relational and spiritual dynamics in many non-Western cultures.

Digital communication platforms have also emerged as adjuncts to traditional in-person interactions. Rosa et al. [Rosa 2025] explored the use of WhatsApp messaging between PPC psychologists and adolescents with life-limiting illnesses. While WhatsApp enabled more immediate, patient-centered interactions, symptom monitoring, and emotional support, it is important to note that this approach has not been formally evaluated in neuropalliative care populations, including parents and children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. The potential role of such tools remains promising but requires formal validation.

Most of these innovations have been piloted in oncology-based palliative care settings [Burke 2023; Chauhan 2024]. Applying them to children with neurologic illness—who often present with earlier onset, slower disease progression, and limited communication capacity—requires careful adaptation and empirical validation. Structured interventions must account for the complexities of neurological prognosis, decision-making capacity, and long-term family involvement.

Innovative communication strategies must also address the ethical and interdisciplinary challenges that frequently arise in the care of children with neurological disease. These cases are often marked by prognostic uncertainty, moral complexity, and fragmented care structures—requiring more than just clinical expertise. A central ethical dilemma in neuropalliative care involves decisions around the initiation, withholding, or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. As Meglič et al. [Meglic 2025] observed, divergent medical opinions between neurologists, intensivists, and palliative care providers can result in inconsistent messages to families and delayed palliative care integration. In some cases, children may be excluded from PPC services—not based on prognosis, but due to unresolved team conflict or a lack of institutional consensus. These scenarios pose serious ethical concerns and illustrate the importance of coordinated and ethically attuned communication. In high-acuity settings such as NICUs and PICUs, these tensions are often amplified. Sorin et al. [Sorin 2020] emphasized that progressive, emotionally sensitive communication is essential to build parental trust and facilitate ethical decision-making. Families benefit when complex issues are introduced gradually, in emotionally safe environments, and when clinicians avoid abrupt, fragmented, or overly technical discussions.

To address this, ethically informed communication models should integrate the primary treating team into early palliative care discussions and ensure consistency in messaging across disciplines. Hrdličková et al. [Hrdlickova 2023] found that families highly valued the presence of trusted clinicians during PPC introductions and appreciated being invited to review and edit written summaries of these meetings—a practice that promotes transparency and narrative inclusion.

Structured ACP programs like PediSICP have also demonstrated potential in promoting goal-aligned, ethically sound decision-making, even in the presence of diagnostic ambiguity [DeCourcey 2024]. However, their use in neuropalliative care must be adapted to the layered emotional, developmental, and moral complexities of this population.

Ultimately, ethically grounded communication is relational and systemic. It requires shared ethical language, interdisciplinary training, and institutional commitment to reducing communication silos and moral distress. Ensuring ethically sound, culturally humble, and interdisciplinary communication models is essential to delivering neuropalliative care that respects the dignity, values, and humanity of every child and family.

7. Conclusions

The delivery of high-quality pediatric palliative and neuropalliative care requires culturally humble, individualized communication approaches that respect the diverse worldviews, spiritual needs, and decision-making frameworks of families. This review underscores that children with neurological conditions—who represent a substantial proportion of PPC recipients—face distinct challenges arising from prolonged disease trajectories, developmental limitations, and enduring prognostic uncertainty.

While there is growing awareness of the role of cultural and spiritual beliefs in shaping communication preferences, most available evidence continues to originate from oncology-based PPC models. As such, there is an urgent need for dedicated, multi-centered research exploring communication strategies tailored to neurologically ill children, especially in cross-cultural and multidisciplinary settings. Future work should investigate how structured tools such as culturally co-designed advance care planning (ACP) models and dignity therapies can be ethically and developmentally adapted for children with neurocomplex conditions.

At the systemic level, communication frameworks must also address ethical and interdisciplinary tensions that can arise when care teams hold divergent views about prognosis or treatment goals. As highlighted in recent studies, delayed or misaligned messaging, particularly in NICU and neurology contexts, may inadvertently exclude children from timely PPC referral and erode family trust. Shared decision-making models, structured documentation, and the consistent inclusion of the treating team in early PPC conversations are all promising practices that merit wider implementation and evaluation.

From an institutional and policy perspective, equity, diversity, and inclusion should become foundational principles—not only in research design but also in workforce training, guideline development, and routine clinical practice. Communication strategies must embrace the intersectionality of family experience and avoid oversimplified assumptions based on religious or ethnic labels. Families must be approached as experts in their own values and goals, and providers must be supported in cultivating skills that center relational, context-aware, and ethically grounded communication.

Moving forward, efforts to improve PPC communication must prioritize validation of tailored models across neurological conditions, integration of ethics-informed practices, and development of tools that are flexible across cultural and developmental dimensions. These steps are essential not only to clinical excellence, but to the moral integrity of care itself. Supporting the dignity, agency, and humanity of every child and family—regardless of cultural background or neurological status—must remain at the heart of the palliative care mission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B., L.G., C.A.; methodology, F.B., L.G.; investigation, All; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.; writing—review and editing, All. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 4o for the purposes of English editing only. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al Mutair A., McCarthy A. Traditional and religious perspectives towards palliative care in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 25, 432–438.

- Benini F., Papadatou D., Bernadá M., Craig F., De Zen L., Downing J., et al. International standards for Pediatric Palliative Care: from IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, e529–e543. [CrossRef]

- Bergstraesser E., Thienprayoon R., Brook L.A., Fraser L.K., Hynson J.L., Rosenberg A.R., Snaman J.M., Weaver M.S., Widger K., Zernikow B., Jones C.A., Schlögl M. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Prognostication in Children. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 1725–1731. [CrossRef]

- Brooks L., Manias E., Bloomer M.J. Cultural and religious influences on decision-making in pediatric palliative care: Perspectives from health professionals. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 71, e120–e127.

- Brooks L., Manias E., Bloomer M.J. Patient and family engagement in palliative care: How culture influences participation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, in press.

- Bruun A.C., Rydahl E., Timm H.U., Hølge-Hazelton B. Healthcare professionals’ experiences of providing culturally competent care at the end of life: An integrative review. Palliat. Support. Care 2025, 23, 175–189.

- Burke C., Doody O., Lloyd B. Healthcare practitioners’ perspectives of providing palliative care to patients from culturally diverse backgrounds: a qualitative systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 182. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan A., Chitkara U., Walsan R., et al. Co-designing strategies to improve advance care planning among people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds with cancer: iCanCarePlan study protocol. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 123. [CrossRef]

- Davies B., Brenner P., Orloff S., Sumner L., Worden W. Addressing spirituality in pediatric hospice and palliative care. J. Palliat. Care 2002, 18, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- DeCourcey D.D., Bernacki R.E., Nava-Coulter B., Lach S., Xiong N., Wolfe J. Feasibility of a Serious Illness Communication Program for Pediatric Advance Care Planning. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2424626. [CrossRef]

- Hexem K.R., Mollen C.J., Carroll K., Lanctot D.A., Feudtner C. How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality, or life philosophy in tough times. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Hrdlickova L., Polakova K., Loucka M. Innovative communication approaches for initializing pediatric palliative care: perspectives of family caregivers and treating specialists. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 152. [CrossRef]

- Islam J.Y., Sharp L.K., Huo D., et al. Disparities in patient-clinician communication across racial and ethnic groups at the end of life: A systematic review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023, 40, 14–27.

- Ju J., Hur H., Lee E., et al. Communication patterns in end-of-life care among ethnically diverse families: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, in press.

- Koch K., Marks K.E., Pritchard M., et al. Communication about prognosis: Understanding the barriers across cultures. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28015.

- Lai M., Chiu T., Lee M., et al. Doctor-patient communication about do-not-resuscitate decisions: An intervention study in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Med. Ethics 2014, 40, 309–314.

- Lau W.K., Fehnel C.R., Macchi Z.A., Mehta A.K., Auffret M., Bogetz J.F., et al. Research Priorities in Neuropalliative Care: A Consensus Statement From the International Neuropalliative Care Society. JAMA Neurol. 2025, 82, 295–302.

- Lin J., Guo Q., Zhou X., et al. Development of the pediatric family-based dignity therapy protocol for terminally ill children and their families: a mixed-methods study. Palliat. Support. Care 2024, 22, 783–791.

- Lin X., Guo Q., Bai Y., Liu Q. Differences in the knowledge, attitudes, and needs of caregivers and healthcare providers regarding palliative care: a cross-sectional investigation in pediatric settings in China. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 386.

- Lombardi R., Carlucci A., Maltoni M., et al. Barriers and facilitators to early palliative care integration in pediatric oncology: A multicenter Italian study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2024, in press.

- Lopez-Sierra H.E., Rodríguez-Sánchez J. Religious coping styles among parents facing a child’s terminal illness. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 2015, 11, 250–269.

- Mach J., Dizon D.S., Stroud S., et al. Communication challenges with minority patients in palliative care: Recognizing and addressing barriers. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2020, 21, 90.

- Meglič A., Lisec A. Paediatric Palliative Care in Clinical Practice: Ethical Issues in Advance Care Planning and End-of-Life Decisions. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e70094. [CrossRef]

- Miquel M., Porta-Sales J., Tuca A., et al. Religion, spirituality, and life philosophy in parents of seriously ill children: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 157–167.

- Monette D.L., Barnett M., Wu Y.P. Addressing cultural barriers to palliative care: A narrative review. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 1016–1023.

- O’Neill J.L., Lakin J.R., Gramling R. Cultural safety in pediatric palliative care: A scoping review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2025, in press.

- Peng N.T., Huang L., Chiou T.J. Cultural practices and end-of-life decision-making in the neonatal intensive care unit in Taiwan. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2012, 53, 165–170.

- Pentaris P., Christodoulou-Fella M. Exploring cultural competence and religious literacy in hospice and palliative care professionals. Omega (Westport) 2020, 82, 454–471.

- Pereira-Salgado A., Mader P., O’Callaghan C., et al. Religious leaders’ perceptions of advance care planning: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 734–746.

- Puchalski C.M., Kilpatrick S.D., McCullough M.E., Larson D.B. A systematic review of spiritual and religious variables in palliative medicine and end-of-life care. Palliat. Support. Care 2003, 1, 7–13.

- Puchalski C.M. The role of spirituality in health care. Baylor Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2003, 16, 352–357.

- Sorin G., Dany L., Vialet R., Thomachot L., Hassid S., Michel F., Tosello B. How doctors communicated with parents in a neonatal intensive care: Communication and ethical issues. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Redman H., Clancy M., Thomas F. Culturally sensitive neonatal palliative care: a critical review. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2024, 18, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Rent T., Creutzfeldt C.J., Prusaczyk B., Engelberg R.A., Curtis J.R., Engelberg R. Communication in pediatric palliative care for non-English-speaking families: Challenges and opportunities. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 1032–1040.

- Rent T., Creutzfeldt C.J., Prusaczyk B., Engelberg R.A., Curtis J.R., Engelberg R. Inequities in pediatric palliative care: Emerging challenges and future directions. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2023, 4, 72–79.

- Rosa M., Santini A., De Tommasi V., et al. The blue tick: WhatsApp as a care tool in pediatric palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 103.

- Rosenberg A.R., Bona K., Coker T., Feudtner C., Houston K., Ibrahim A., et al. Pediatric palliative care in the multicultural context: findings from a workshop conference. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 846–855. [CrossRef]

- Sansom-Daly U.M., McGill B.C., Garvey G., et al. Perspectives of adolescents and young adults on discussing spirituality and end-of-life issues during advance care planning. Palliat. Med. 2023, 37, 706–716.

- Schiavon M., Lazzarin P., Agosto C., Rusalen F., Divisic A., Zanin A., et al. A 15-year experience in pediatric palliative care: a retrospective hospital-based study. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 202. [CrossRef]

- Suntai C., Chipalo E. Racial and ethnic differences in provider-engaged religious belief discussions with older adults at the end of life. J. Relig. Health 2022, 61, 568–580.

- Thorvilson M.J., Manahan A.J., Schiltz B.M., Collura C.A. Homeward bound: Cross-cultural care at end of life enhanced by pediatric palliative transport. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 464–467. [CrossRef]

- Upshaw N.C., Roche A., Gleditsch K., et al. Palliative care considerations and practices for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e28781. [CrossRef]

- Wiener L., McConnell D.G., Latella L., Ludi E. Cultural and religious considerations in pediatric palliative care. Palliat. Support. Care 2013, 11, 47–67. [CrossRef]

- Woodgate R.L. Children’s perspectives on living with neurological impairment: Implications for pediatric palliative care. Children 2024, 12, 209.

Table 1.

Core Cultural Dimensions Shaping Communication in Pediatric Palliative Care.

Table 1.

Core Cultural Dimensions Shaping Communication in Pediatric Palliative Care.

Table 2.

Unique Communication Challenges in Neurologically Ill Children.

Table 2.

Unique Communication Challenges in Neurologically Ill Children.

Table 3.

Promising Communication Innovations in Cross-Cultural PPC.

Table 3.

Promising Communication Innovations in Cross-Cultural PPC.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).