Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

08 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research Gap

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Air Transport Infrastructure, Urban Population and Emissions

2.2.2. Financial Development, Economic Growth and Emissions

2.2.3. Innovation and Emissions

3. Methodology

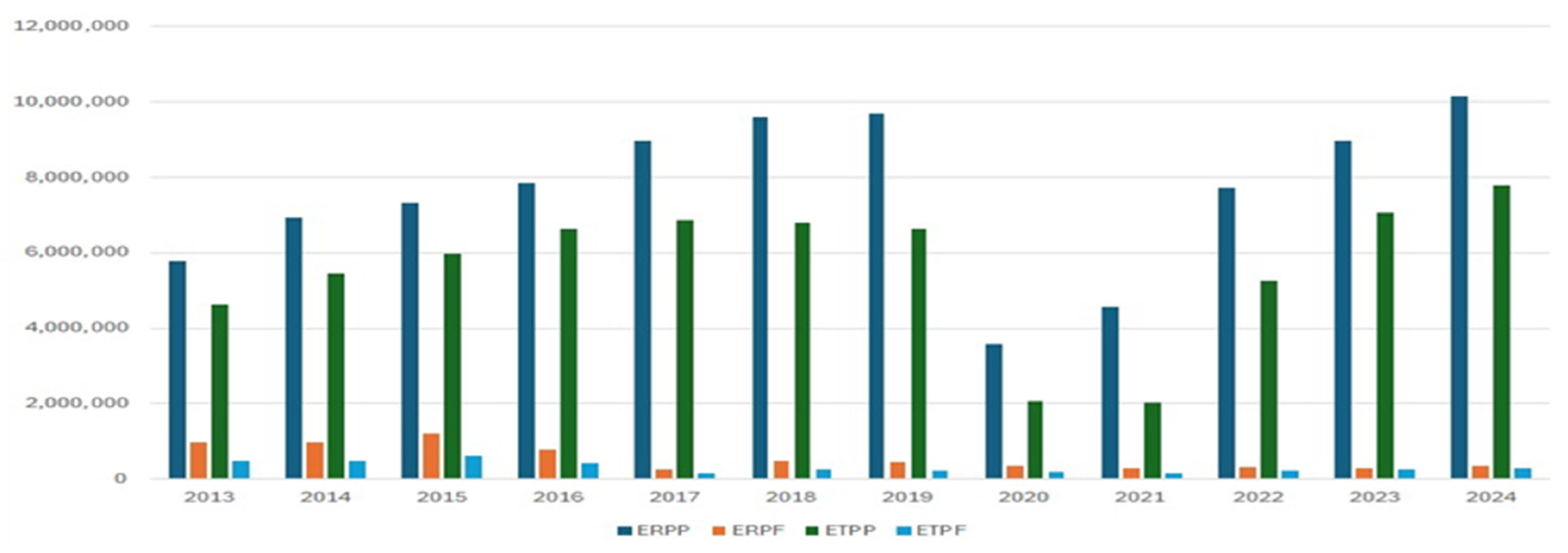

3.1. Data and Data Sources

| Symbol | Variable | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from Transport (Energy) (Mt CO2e) | https://databank.worldbank.org/ |

| FDI | Financial Development Index | https://data.imf.org/?sk=f8032e80-b36c-43b1-ac26-493c5b1cd33b |

| GDP | GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$) | https://databank.worldbank.org/ |

| ATP | All technologies (total patents) | https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx? |

| POP | Urban population | https://databank.worldbank.org/ |

| AIRP | Air transport, passengers carried | https://databank.worldbank.org/ |

3.2. Derivation of the Model

Quantθ(yi|xi) = inf {y: Fi(y|x) θ} = αθxi′,

Quantθ(ui,θ |xi) = 0,

(θ − 1) u < 0

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

| At Level | |||||||

| CO2 | AIRP | ATP | FDI | GDP | POP | ||

| With Constant | t-Statistic | -0.2471 | -2.3423 | 2.8067 | -1.4003 | -2.4049 | -0.0757 |

| Prob. | 0.9221 | 0.1674 | 1.0000 | 0.5698 | 0.1486 | 0.9439 | |

| n0 | n0 | n0 | n0 | n0 | n0 | ||

| With Constant & Trend | t-Statistic | -2.0261 | -2.9386 | 2.9222 | -2.1100 | -1.3203 | -2.7743 |

| Prob. | 0.5648 | 0.1681 | 1.0000 | 0.5210 | 0.8645 | 0.2182 | |

| n0 | n0 | n0 | n0 | n0 | n0 | ||

| Without Constant & Trend | t-Statistic | 1.6381 | 0.3120 | -2.0157 | 0.3445 | -1.4232 | 6.2173 |

| Prob. | 0.9725 | 0.7696 | 0.0440 | 0.7786 | 0.1413 | 1.0000 | |

| n0 | n0 | ** | n0 | n0 | n0 | ||

| At First Difference | |||||||

| d(CO2) | d(AIRP) | d(ATP) | d(FDI) | d(GDP) | d(POP) | ||

| With Constant | t-Statistic | 0.0070 | -1.6884 | 2.6883 | -5.4177 | -4.2198 | -1.7469 |

| Prob. | *** | 0.4241 | 1.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0025 | 0.3967 | |

| -3.7319 | n0 | n0 | *** | *** | n0 | ||

| With Constant & Trend | t-Statistic | 0.0349 | -1.3057 | -0.4984 | -5.3524 | -4.4241 | -1.1003 |

| Prob. | ** | 0.8618 | 0.9762 | 0.0007 | 0.0072 | 0.9089 | |

| -3.1416 | n0 | n0 | *** | *** | n0 | ||

| Without Constant & Trend | t-Statistic | 0.0027 | -8.4708 | 3.5114 | -5.4322 | -4.0938 | -0.0761 |

| Prob. | *** | 0.0000 | 0.9996 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.6476 | |

| 0.0070 | *** | n0 | *** | *** | n0 | ||

5. Conclusion

6. Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alanazi, F., and M. Alenezi. 2024. Sustainable Transportation and Intelligent Infrastructure Development in Saudi Arabia: A Study on the Impact of Saudi Vision 2030 and Renewable Energy Integration. In Emerging Cutting-Edge Applied Research and Development in Intelligent Traffic and Transportation Systems. IOS Press: pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Aldegheishem, A. 2024. The Impact of Air Transportation, Trade Openness, and Economic Growth on CO2 Emissions in Saudi Arabia. Frontiers in Environmental Science 12: 1366054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatar, K. M. 2024. Smart transportation planning and its challenges in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sustainable Futures 8: 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., S. Sumaira, H. M. A. Siddique, and S. Ashiq. 2023. Impact of economic growth, energy consumption and urbanization on carbon dioxide emissions in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Policy Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabbagh, M. 2024. Toward carbon-neutral road transportation in the GCC countries: an analysis of energy consumption and CO2 emissions. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehry, A. S., and M. Belloumi. 2017. Study of the environmental Kuznets curve for transport carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 75: 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altouma, A., B. Bashir, B. Ata, A. Ocwa, A. Alsalman, E. Harsányi, and S. Mohammed. 2024. An environmental impact assessment of Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030 for sustainable urban development: A policy perspective on greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 21: 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avotra, A. A. R. N., and A. Nawaz. 2023. Asymmetric impact of transportation on carbon emissions influencing SDGs of climate change. Chemosphere 324: 138301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, A., M. Alnour, A. Jahanger, and J. C. Onwe. 2022. Do technological innovation and urbanization mitigate carbon dioxide emissions from the transport sector? Technology in Society 71: 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, M., F. Belaid, N. Almubarak, and T. Almulhim. 2025. Mapping Saudi Arabia’s low emissions transition path by 2060: An input-output analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 211: 123920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsuwadan, J. 2024. Transport Sector Emissions and Environmental Sustainability: Empirical Evidence from GCC Economies. Sustainability 16, 23: 10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartle, J. R., R. K. Lutte, and D. Z. Leuenberger. 2021. Sustainability and air freight transportation: Lessons from the global pandemic. Sustainability 13, 7: 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y., T. H. Lee, and B. Saltoglu. 2006. Evaluating the predictive performance of value-at-risk models in emerging markets: A reality check. Journal of Forecasting 25, 2: 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatti, W., and M. T. Majeed. 2022. Investigating the links between ICTs, passenger transportation, and environmental sustainability. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29, 18: 26564–26574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J., R. Alvarado, S. Ali, Z. Ahmed, and M. S. Meo. 2023. Transport infrastructure, economic growth, and transport CO2 emissions nexus. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30, 14: 40094–40106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhaj, M. 2024. Do Energy Efficiency and Technology Boost Sustainable Environment: Evidence from GCC Countries. Journal of Ecohumanism 3, 7: 2545–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmonshid, L. B. E., O. A. Sayed, G. M. Awad Yousif, K. E. H. I. Eldaw, and M. A. Hussein. 2024. The Impact of Financial Efficiency and Renewable Energy Consumption on CO2 Emission Reduction in GCC Economies: A Panel Data Quantile Regression Approach. Sustainability 16, 14: 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, A. 2016. Air pollution in the Arabian Peninsula (Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman): causes, effects, and aerosol categorization. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 9: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. S., S. H. Rahaman, A. ur Rehman, and I. Khan. 2023. ICT’s impact on CO2 emissions in GCC region: the relevance of energy use and financial development. Energy Strategy Reviews 49: 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R. 2004. Quantile regression for longitudinal data. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 91, 1: 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H. 2022. Trade openness, industrialization, urbanization and pollution emissions in GCC countries: A way towards green and circular economies. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 12, 2: 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosteller, F., and J. W. Tukey. 1977. Data analysis and regression: A second course in statistics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Mercure, J. F., and A. Lam. 2015. The effectiveness of policy on consumer choices for private road passenger transport emissions reductions in six major economies. Environmental Research Letters 10, 6: 064008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onifade, S. T., and I. Haouas. 2023. Assessing environmental sustainability in top Middle East travel destinations: insights on the multifaceted roles of air transport amidst other energy indicators. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30, 45: 101911–101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N., and D. Mehta. 2023. The asymmetry effect of industrialization, financial development and globalization on CO2 emissions. International Journal of Thermofluids 20: 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N., and D. Mehta. 2023. The asymmetry effect of industrialization, financial development and globalization on CO2 emissions in India. International Journal of Thermofluids 20: 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggad, B. 2020. Economic development, energy consumption, financial development, and carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia: new evidence from a nonlinear and asymmetric analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27, 17: 21872–21891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, S., M. Shahbaz, and P. Akhtar. 2018. The long-run relationships between transport energy consumption, transport infrastructure, and economic growth in MENA countries. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 111: 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S., S. Y. Genç, H. W. Kamran, and G. Dinca. 2021. Role of green technology innovation and renewable energy in carbon neutrality. Journal of Environmental Management 294: 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehri, T. A., J. F. Braun, N. Howarth, A. Lanza, and M. Luomi. 2023. Saudi Arabia’s climate change policy and the circular carbon economy approach. Climate Policy 23, 2: 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D., S. Zeng, H. Lin, X. Meng, and B. Yu. 2019. Can transportation infrastructure pave a green way? A city-level examination in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 226: 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M., X. Ji, D. Kirikkaleli, and Q. Xu. 2020. COP21 Roadmap: Do innovation, financial development, and transportation infrastructure matter for environmental sustainability in China? Journal of environmental management 271: 111026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadud, Z., M. Adeel, and J. Anable. 2024. Understanding the large role of long-distance travel in carbon emissions from passenger travel. Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J. 2011. The impact of financial development on carbon emissions: An empirical analysis in China. Energy Policy 39: 2197–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| stats | CO2 | AIRP | ATP | FDI | GDP | POP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 92.52362 | 20118240 | 207.9225 | 0.391202 | 20027.89 | 17596038 |

| Median | 81.85870 | 16708204 | 64.76000 | 0.398025 | 19154.80 | 17425683 |

| Maximum | 146.9389 | 46181487 | 758.0800 | 0.518574 | 26279.73 | 27261746 |

| Minimum | 49.40360 | 9409100. | 2.450000 | 0.270000 | 15512.70 | 8148960. |

| Std. Dev. | 35.13393 | 9981821. | 264.4519 | 0.072891 | 3065.917 | 6297875. |

| Skewness | 0.277053 | 0.999203 | 1.088325 | 0.082764 | 0.748188 | 0.065069 |

| Kurtosis | 1.431807 | 2.895162 | 2.631765 | 1.626306 | 2.344913 | 1.592735 |

| Jarque-Bera | 3.803613 | 5.506352 | 6.700931 | 2.632347 | 3.668887 | 2.746328 |

| Probability | 0.149299 | 0.063725 | 0.035068 | 0.268159 | 0.159702 | 0.253304 |

| Sum | 3053.279 | 6.64E+08 | 6861.443 | 12.90965 | 660920.4 | 5.81E+08 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 39500.59 | 3.19E+15 | 2237914. | 0.170018 | 3.01E+08 | 1.27E+15 |

| Observations | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| F-statistic | 0.802143 | Prob. F(5,17) | 0.5635 |

| Obs*R-squared | 4.390447 | Prob. Chi-Square(5) | 0.4947 |

| Scaled explained SS | 1.235944 | Prob. Chi-Square(5) | 0.9414 |

| CO2 | AIRP | ATP | FDI | POP | GDP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 1 | |||||

| AIRP | 0.9187 | 1 | ||||

| ATP | 0.8597 | 0.8574 | 1 | |||

| FDI | 0.8654 | 0.6880 | 0.5779 | 1 | ||

| POP | 0.9699 | 0.8708 | 0.8817 | 0.8436 | 1 | |

| GDP | -0.4496 | -0.3338 | -0.3019 | -0.5578 | -0.5909 | 1 |

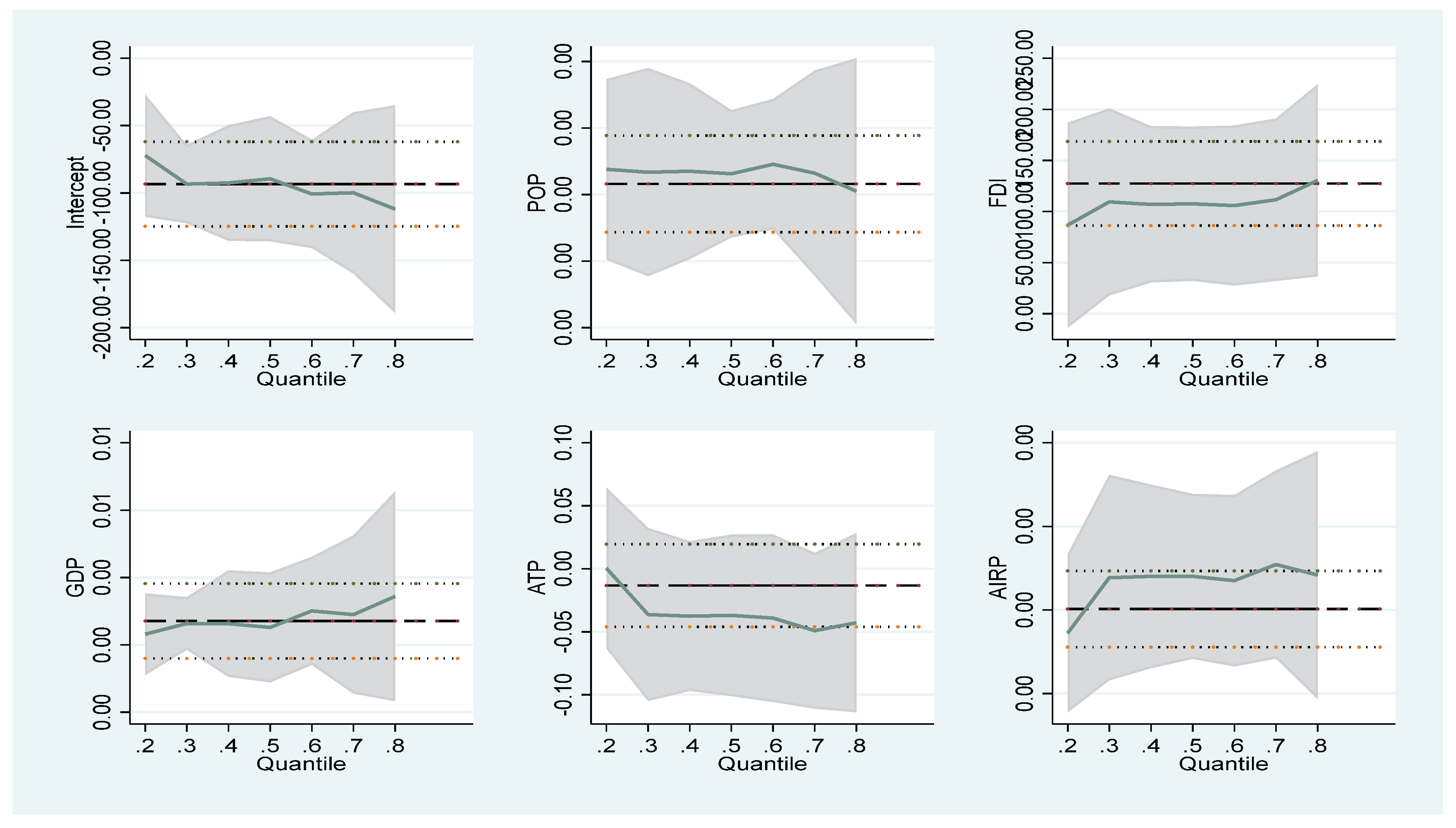

| co2 | co2 | co2 | co2 | co2 | co2 | co2 | co2 | co2 | |

| 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.85 | |

| POP |

3.38e-06 (0.000) |

3.38e-06 (0.000) |

3.34e-06 (0.000) |

3.35e-06 (0.000) |

3.31e-06 (0.000) |

3.45e-06 (0.000) |

3.32e-06 (0.000) |

3.05e-06 (0.000) |

3.38e-06 (0.000) |

| FDI |

86.54813 (0.008) |

86.54813 (0.005) |

109.3879 (0.000) |

106.9544 (0.000) |

107.5237 (0.001) |

105.7613 (0.000) |

111.4847 (0.000) |

130.4335 (0.000) |

86.54813 (0.008) |

| GDP |

.002318 (0.009) |

.002318 (0.006) |

.0026367 (0.001) |

.0026302 (0.001) |

.0025197 (0.002) |

.0030115 (0.000) |

.0029018 (0.001) |

.0034429 (0.000) |

.002318 (0.009) |

| ATP |

.0004933 (0.984) |

.0004933 (0.983) |

.0362964 (0.098) |

-.0375463 (0.070) |

-.0369906 (0.105) |

-.0392032 (0.019) |

-.0491731 (0.032) |

-.0427514 (0.063) |

.0004933 (0.984) |

| AIRP |

7.23e-07 (0.041) |

7.23e-07 (0.030) |

1.39e-06 (0.000) |

1.40e-06 (0.000) |

1.40e-06 (0.000) |

1.35e-06 (0.000) |

1.55e-06 (0.000) |

1.42e-06 (0.000) |

7.23e-07 (0.041) |

| 0bs. | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.8723 | 0.8727 | 0.8857 | 0.9078 | 0.9177 | 0.9185 | 0.9136 | 0.9042 | 0.8977 |

| co2 | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | P>|t| | [95% conf . interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pop | 3.16e-06 | 3.20e-07 | 9.86 | 0.000 | 2.50e-06 | 3.82e-06 |

| FDI | 127.3506 | 18.15573 | 7.01 | 0.000 | 90.16023 | 164.5409 |

| gdp | .0027089 | .00049 | 5.53 | 0.000 | .0017053 | .0037126 |

| ATP | -.0132231 | .0144821 | -0.91 | 0.369 | -.0428884 | .0164422 |

| Airp | 1.01e-06 | 2.01e-07 | 5.04 | 0.000 | 6.01e-07 | 1.42e-06 |

| _Cons | -93.35728 | 13.83904 | -6.75 | 0.008 | -121.7053 | -65.00928 |

| LR chi2(5) = 146.35 | Prob > chi2 = 0.0000 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).