1. Introduction

During pregnancy, women experience both joy and significance as they prepare for their child's arrival. However, this period can also bring about stress due to the numerous physical, psychological, and interpersonal changes and challenges they encounter, including pregnancy related physiological changes such as alterations in hormone balance, blood volume, and metabolism (Chandra and Paray, 2024)(Sun et al., 2024).

On a global scale, the prevalence of stress in pregnant women is a cause for concern for both individuals and society. Maternal mental health is a key focus area in the WHO's Mental Health Action Plan (2013-2030), which estimates that approximately 10% of pregnant women worldwide have experienced mental health issues during pregnancy (World Health Organization, 2021). A Swedish study found that between 20% to 35% of pregnant women evaluated their own emotional and physical well-being as poor (Schytt and Hildingsson, 2011). Pregnancy-related anxiety represents a unique psychological stressor during pregnancy, distinct from both depression and general anxiety disorders (Tarafa et al., 2022). It encompasses feelings of fear and worry concerning the woman's health, the child's well-being, the progression of the pregnancy and the delivery (Tarafa et al., 2022). Pregnancy-related anxiety is among the common maternal mental health challenges during pregnancy.

A mechanism explaining the association between prenatal maternal stress and attention disorders in the child involves the placental transfer of hormones. Experiencing prolonged chronic stress results in dysfunction in the stress response feedback loop, causing the HPA-axis to become less sensitive to signals sent by cortisol in the bloodstream (Gjerstad et al., 2018). Fetal exposure to cortisol is regulated by the enzyme 11β-HSD2, and a decrease in enzyme activity results in more cortisol passing from the mother to the fetus through the placental barrier. Additionally, a study found a correlation between maternal cortisol and cortisol in amniotic fluid, with cortisol levels in the amniotic fluid being higher in women with anxiety (Glover et al., 2009).

Studies have linked various types of prenatal maternal stress to children's development and health. Studies indicate associations between maternal stress during pregnancy and neurobehavioral problems in the offspring, such as ADHD, that manifest throughout the lifespan (Van Den Bergh et al., 2020), and the risk of symptoms of attention disorders, symptoms of ADHD, or diagnosed ADHD in children (Li et al., 2010; MacKinnon et al., 2018; Ronald et al., 2011; Shao et al., 2020; Shih et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2015). These studies suggest that the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis plays a role in mediating the effects of maternal stress on the fetal brain. The focus has been on prenatal maternal stress and its correlation with ADHD symptoms or diagnoses in children at young ages ranging from 2 to 4.5 years (Li et al., 2010; Ronald et al., 2011; Shao et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2015) and two studies explored similar associations in older age groups, focusing on children aged 8 and above, and those between 6 and 16 years old (MacKinnon et al., 2018; Shih et al., 2022). The causality of prenatal maternal stress on etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders in the offspring is studied in large population cohorts. Recently, research has focused on biological correlates and mediators of these findings (Lautarescu et al., 2020). When an increased amount of maternal cortisol passes through the placenta it can bind to glucocorticoid receptors in the developing brain, where activation of the HPA axis is regulated by limbic structures closely associated and mutually regulated by cortical structures mainly located in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), creating a corticolimbic-HPA system. The PFC is responsible for executive functions such as predicting consequences of behaviors and understanding social behavior (Martin et al., 2009).

The high prevalence of stressed women of reproductive age, as well as the adverse health consequences for both mother and child, emphasizes that stress during pregnancy is a public health concern. Studies often examine populations of women experiencing severe mental distress (Glover, 2015). Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the long-term effects of prenatal maternal stress on children's attention capacities at the age of 5 in a low-risk population of women exposed to normal levels of stress during pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Maternal Stress and Placental Function Project

The current study is a 5-year follow-up of the project: Maternal Stress and Placental Function (MSPF), conducted by the Department of Environmental Health within the Institute of Public Health at the University of Copenhagen. The study is based on data on fetal exposure measured during pregnancy and directly after birth, and outcome measures at 5 years of age, with focus on attention deficit. The aim of MSPF was to investigate how prenatal maternal stress affects the placenta's ability to transport and metabolize cortisol. MSPF involved collection of four self-reported questionnaires on: depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy, pregnancy-related anxiety, personality, and demographic information (age, BMI, smoking and alcohol intake before and during pregnancy, chronic disease, medication use, stressful life events, housing and environmental conditions, birth parameters and the child's characteristics at birth) and biomarkers in blood and placental tissue (Dahlerup et al., 2018). The MSPF population at birth was recruited from July 2015 to May 2016 among pregnant women above 18 years of age, giving birth at Copenhagen University Hospital.

2.2. Follow-Up After 5 Years

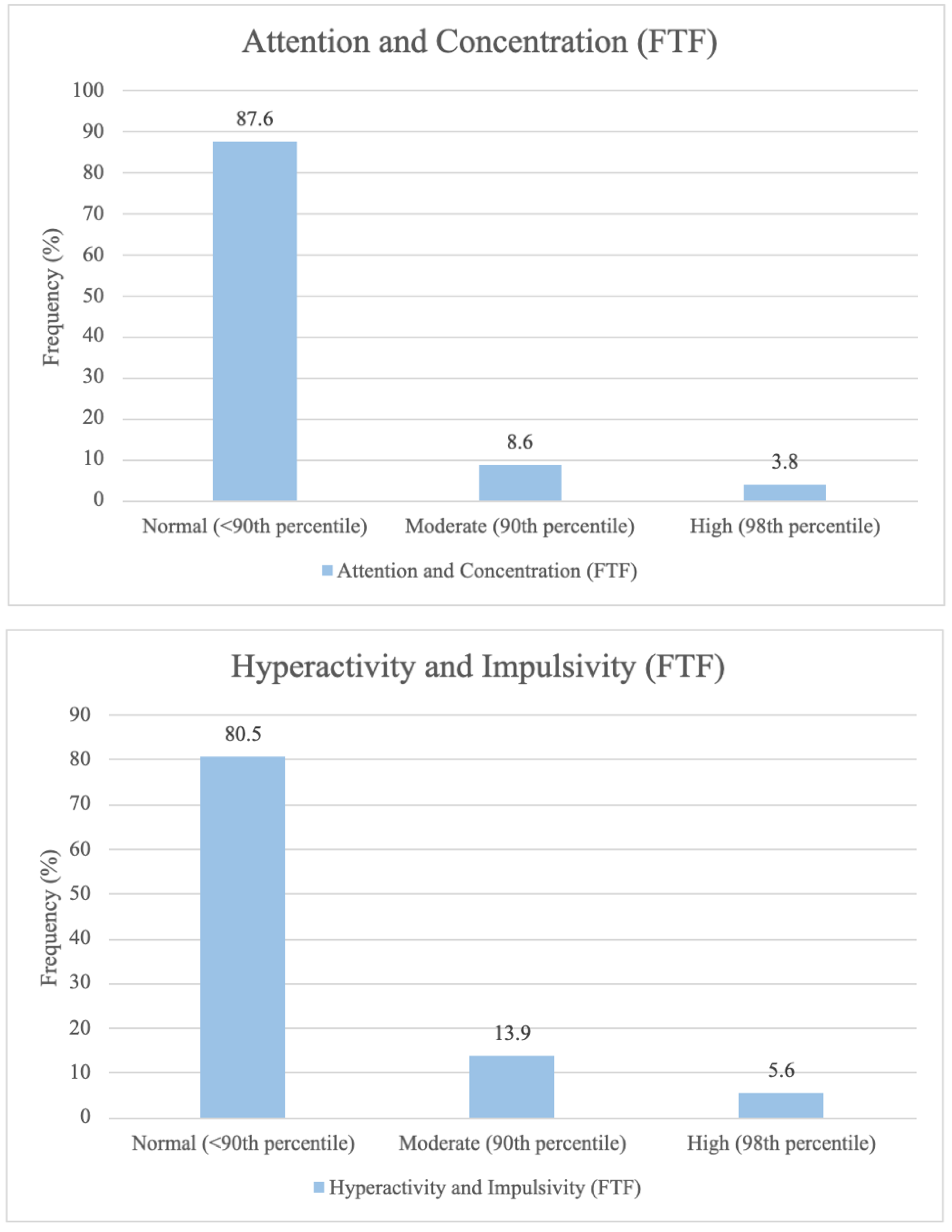

The project was approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee of Copenhagen (H-15006254) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2015-41-4208). The 5-year follow up was conducted in 2020 and registered in the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee of Copenhagen as not subject to assessment as it was strictly questionnaire collection (j.nr. 20055232). All women were informed about the aim of the study and gave written informed consent. The study is registered in the University of Copenhagen's register of research projects that include personal data. Participants in the Maternal Stress and Placental Function (MSPF) project were invited to participate in the 5-year follow up via e-mail or letter a few days before the 5

th birthday of the child. A flow chart of the recruitment process is shown in

Figure 1.

A total of 273 women participated in MSPF at birth and 256 (94%) of these gave consent to follow-up. Among these 256 women, 115 were included in the follow-up cohort, accounting for 45% of the invited participants (

Figure 1).

The follow up contained five questionnaires that required approximately 2 hours to complete, and they were answered electronically via SurveyXact, which could be accessed through a link provided in the invitation letter. The first questionnaire was on demographic information including age, income level, educational level and breastfeeding status. Second, the mothers answered various questionnaires to assess both their own and their children's mental health and development. These included the 'Depression Anxiety Stress Scales' (DASS-42) (Psychology Foundation of Australia, 2022), the parent-reported 'Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire' (SDQ) (SDQ-INFO, n.d.), the 'Preschool Anxiety Scale' (PAS) for anxiety severity in younger children (Spence et al., 2001), and the 'Five-to-Fifteen Nordic questionnaire' (FTF).

2.3. Exposure Measures

2.3.1. Pregnancy-Related Anxiety

Assessment of Pregnancy-related Anxiety (PRA) was measured at baseline in 2015 and involved the utilization of a Danish translation of the 10-item “Pregnancy-Related Thoughts” (PRT) questionnaire (Dahlerup et al., 2018). Additionally, four supplementary items (Birth-Related Thoughts, BRT) were included, based on questions used by the Copenhagen University Hospital to screen for severely anxious pregnant women. The PRT-questions used a four-point Likert scale (1 to 4) with response options ranging from 1 - Not at all to 4 - to a higher degree. The BRT questionnaire had a six-point Likert scale (0 to 5) with response options ranging from 0 - No concern at all to 5 - Extreme concern. Combining them yielded a Pregnancy-Related Anxiety measure. Respondents from the current study reported themselves to which degree they experienced each statement while pregnant. PRA was scored and used in the same manner as described by Dahlerup et al. (2018) and categorized into four groups based on total scores in the study: 10-19 defined “no PRA”, 20–25 “some PRA”, 26–31 “moderate PRA” and scores more than 31 “high PRA” (Dahlerup et al., 2018). In the statistical analyses, PRA was examined as a binary variable, wherein women with moderate or high PRA (≥ 26) were compared with those women who had no or low PRA (< 26).

2.3.2. Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-42) comprise 42 items evaluating depression, anxiety, and stress. Each of the three DASS scales contains 14 items, divided into subscales of 2-5 items with similar content (Psychology Foundation of Australia, 2022). Each item describes a common symptom of depression, anxiety, or stress. Each item was rated on a four-point Likert scale (0 to 3) with response options ranging from 0 - Did not fit me to 3 - Fit very much or most of the time for me. Respondents from this study self-reported the frequency of experiencing each state over the past week. Scores for Depression, Anxiety and Stress were calculated by summing the scores for relevant items (Psychology Foundation of Australia, 2022).

DASS was measured at baseline in 2015 and at follow-up in 2020. It was treated as a binary variable in the statistical analyses, where women with a moderate or high score (depression: ≥ 14, anxiety: ≥ 10, stress: ≥ 19) were compared to those with scores below these thresholds, indicative of having a normal or mild score. Correlation between DASS scores at baseline and follow-up was investigated.

2.3.3. Biological Measures

As a part of the MSPF at birth, participants donated a maternal blood-sample and umbilical cord blood, as well as a tissue sample of the placenta. Maternal and fetal blood cortisol and cortisone at birth were quantified.

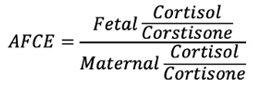

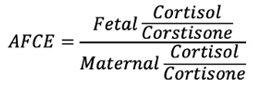

We applied a ratio between fetal and maternal cortisol and cortisone levels, termed Adjusted Fetal Cortisol Exposure (AFCE) to measure the placental ability to metabolize cortisol at term. AFCE was developed by Dahlerup et al. (2018):

The levels of cortisol in both mother and fetus were also included as independent biomarkers of stress and were examined binarily. Thresholds for fetal cortisol and AFCE were conducted such that women in the higher threshold group had a higher average score across the three outcome measures compared to those below the threshold. In the case of maternal cortisol, stratification based on the distribution of cortisol levels and outcome measure scores among women lacked meaningful distinctions. Consequently, the threshold was established at the population's mean cortisol concentration, thereby ensuring that the comparison groups were situated above and below the mean, respectively. For maternal cortisol, the threshold was determined at > 3.2 (1584.9 nmol/L) and for fetal cortisol, the threshold was determined at >2.3 (199.5 nmol/L). For AFCE the threshold was determined at a log AFCE ratio > -1.2.

2.4. Outcome Measures

Attention deficits in the children were examined by using the two validated questionnaires: "Five-to-Fifteen Nordic questionnaire for evaluation of development and behavior" (FTF) and ”Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire” (SDQ).

2.4.1. Five-to-Fifteen Questionnaire

FTF is a parent-reported questionnaire developed to examine children aged 5 to 15 (Trillingsgaard et al., 2004). The questionnaire includes 181 statements that are arranged into eight general domains divided into 20 subdomains (Kadesjö et al., 2004). The main outcome measure in this study was assessed using scores from the subdomains Attention and concentration and Hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Scores from the subdomain Attention and concentration, consisted of eight items (item 18-26). Each item describes the child's ability to be attentive or concentrated in relation to various tasks or activities in different ways such as “has difficulty following instructions and completing tasks” and “becomes tired of or avoids tasks that require mental effort”. Likewise, the subdomain Hyperactivity and impulsivity examined and consisted of nine items (item 27-35). The items describe to which degree the child is overly active and impulsive such as “has difficulty sitting still in situations where it is expected” and “jumps into answering before hearing the question to completion”. Each item was rated on a three-point Likert scale (0 to 2) with response options ranging from 0 - Not applicable to 2 - Certainly applies. Scores from the subdomains were calculated by summing scores for each item following official guidelines for assessing subdomain in the FTF-questionnaire (Trillingsgaard, A. et al., 2005), resulting in scores ranging from 0-16 for Attention and concentration and 0-18 for Hyperactivity and impulsivity. Scores on Attention and concentration and Hyperactivity and impulsivity were dichotomized into above and below a score of 4 in accordance with other studies (Stübner et al., 2020).

2.4.2. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

SDQ is a 25-item scale developed to screen for psychopathology in children and adolescents (SDQ-INFO, n.d.). SDQ is completed by parents reporting on their child's behavior in the past six months and consists of five subdomains of psychological adjustment: 1) Hyperactivity or Inattention, 2) Peer problems, 3) Conduct problems, 4) Emotional symptoms, and 5) Prosocial behaviors. Each subdomain consists of five items, and scores from the subdomain Hyperactivity and Inattention are presented. Each item in this subdomain screens for hyperactivity and inattention by assessing different aspects of the child's behavior and attention span. All five items were rated on a three-point Likert Scale (0 to 2) with the response options ranging from 0 - not true to 2 - certainly true, resulting in scores ranging from 0-10. Scores from the subdomains were calculated using official guidelines (SDQ-INFO, n.d.).

Hyperactivity and Inattention scores were categorized into four groups based on the obtained scores in the study: 0-5 defined “normal”, 6 - “slightly raised”, 7 - “high” and scores more than 8 - “very high” (SDQ-INFO, n.d.). In the statistical analysis, a threshold was determined at > 5, indicating difficulties with hyperactivity and inattention, following the official SDQ documentation (SDQ-INFO, n.d.).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

The study population characteristics, the associations between biological stress measures (maternal and fetal cortisol, as well as AFCE), and children's attention deficits were assessed using the Chi-square test for distribution analysis.

Associations between maternal pregnancy-related anxiety and children's attention deficits were assessed using logistic regression on the three different scales: Attention and concentration, Hyperactivity and impulsivity and Hyperactivity and Inattention. Additionally, the probability of association is presented as unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (OR) with a 95 % confidence interval (CI). Separate analyses explored interactions between pregnancy-related anxiety and various variables including maternal age, BMI, smoking during pregnancy, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, medication intake, normal pregnancy (self-reported absence of gestational complications), income level, educational level, birth strain, neuroticism, delivery mode, parity, breastfeeding, child sex and birth weight in relation to the child's attention capacity. Models including interactions between PRA and parity, educational level, consumption of alcohol, and smoking during pregnancy, showed statistical significance. However, the models examining interactions with smoking, alcohol consumption, and educational level had a very limited number of observations in some of the groups (results not shown). Hence, the stratified analysis is divided only according to parity.

Potential confounders were selected and divided into seven groups (model 1-7). Model 1 (unadjusted), model 2 (demographic variables): higher educational level, income level, and maternal age, model 3 (lifestyle factors): smoking during pregnancy, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, and BMI before pregnancy, model 4 (birth-related characteristics): normal pregnancy, delivery mode, parity, and birth strain score, model 5 (maternal health): maternal chronic disease reported, and medication during pregnancy, model 6 (neuroticism): neuroticism score, model 7 (characteristics of the child): sex and birth weight. R-studio version 2022.12.0+353 was used to perform statistical analyses, and a 5% significance level was used.

Intercorrelations between exposure variables (DASS, PRA, fetal and maternal cortisol and cortisone, and AFCE) and outcome measures (Attention and concentration, Hyperactivity and impulsivity and Hyperactivity and inattention), were investigated and correlation coefficient was estimated using gamma test.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Exposure Measures

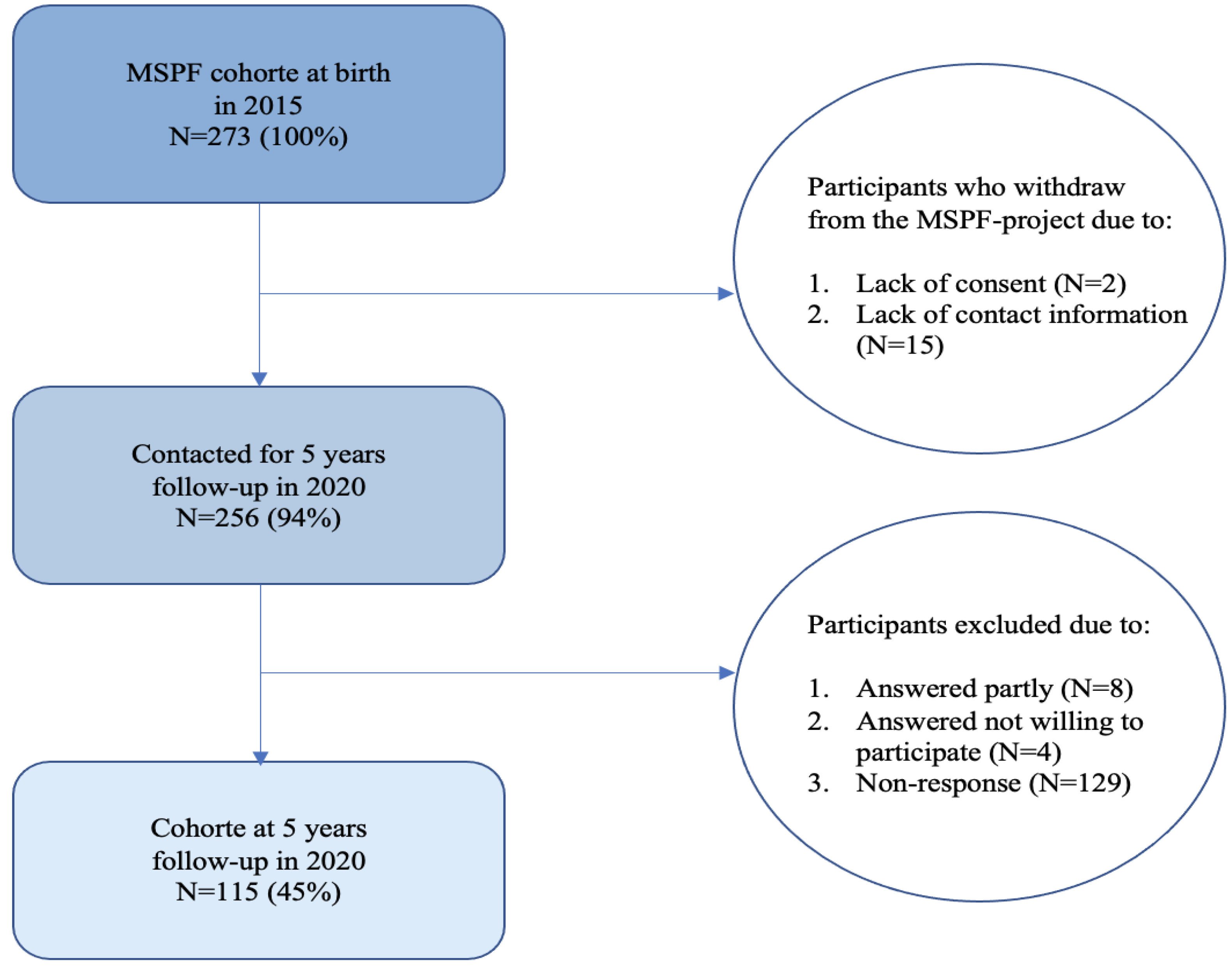

The frequency of PRA-scores measured from the follow-up population at birth distributed into four categories ranging from no PRA to high PRA are depicted in

Figure 2.

The majority of women participating in the 5-year follow-up experienced low levels of pregnancy-related anxiety, e.g. 27.8% experienced no PRA, while one in four (24.9%) had a PRA-score ≥ 26, indicating having moderate to high levels of pregnancy-related anxiety.

In

Supplementary Materials (

Figure S1), the distribution of PRA-questions is delineated. Although it appears that there is a relatively even distribution of average scores across the PRA-questions, two questions related to childbirth achieved the highest average scores: question 1 (

“I am confident of having a normal childbirth”) and question 2 (

“I believe my childbirth will be normal”).

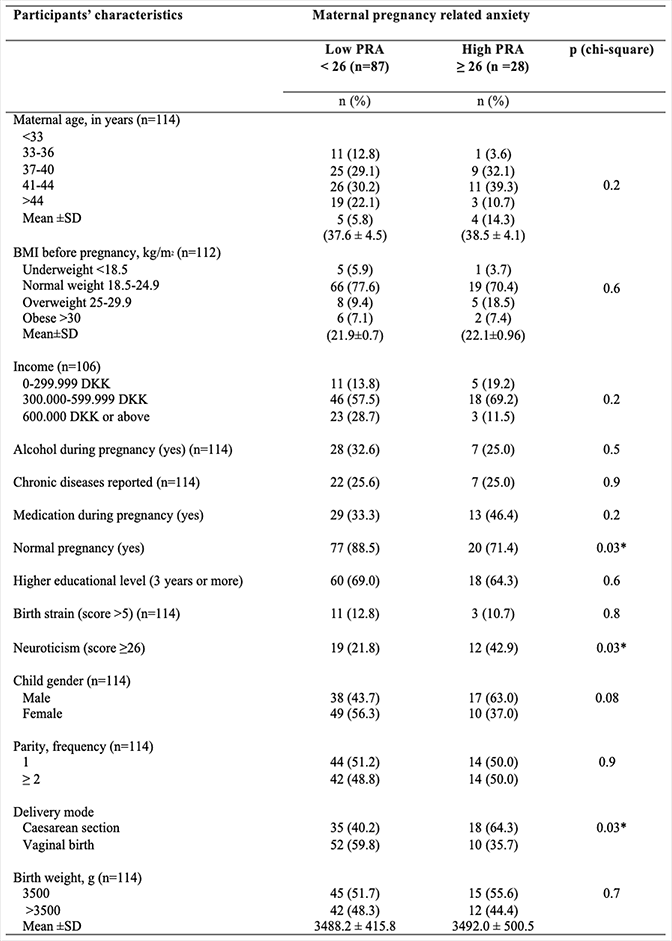

Population Characteristics by PRA Level

Table 1 displays the proportions of demographic characteristics, lifestyle and birth-related outcomes of the women, divided into low PRA (< 26) and high PRA (≥ 26).

Less than one out of ten of the women had smoked during their pregnancy, and approximately a third had consumed alcohol to some extent during pregnancy. There were almost an equal number of girls and boys born, nearly half of the children were delivered by cesarean section, and half of the women were primiparous. Women with high scores on pregnancy-related anxiety (≥26) differed significantly from women without lower scores in pregnancy-related anxiety on three of the tested variables: fewer had experienced a normal pregnancy (p = 0.03), more had a higher neuroticism score (p = 0.03) and more had a cesarean section (delivery mode) (p = 0.03)).

DASS was not explored as the main exposure measure of interest but rather as an indicator for the mothers' mental health at baseline and at the follow-up. Correlation analyses revealed that DASS among the women at baseline and follow-up was significantly correlated. Distribution of DASS at baseline and follow-up is presented in

Supplementary Materials (

Figure S2).

Fetal cortisol, maternal cortisol and AFCE (on a logarithmic scale) appeared approximately normal distributed, as presented in

Supplementary Materials (

Figure S3). The mothers participating in the 5 year follow-up study had an average log cortisol concentration of 3.2 (1584.9 nmol/L), while their corresponding newborns had an average log umbilical cord cortisol concentration of 2.0 (100 nmol/L). The average AFCE ratio was -1.7. Correlation analysis showed that fetal and maternal cortisol and cortisone, and AFCE were intercorrelated, and PRA was significantly correlated with AFCE, presented in

Supplementary Materials (

Table S1).

3.2. Distribution of Attention Deficit Outcome Measures at 5-Year Follow-Up

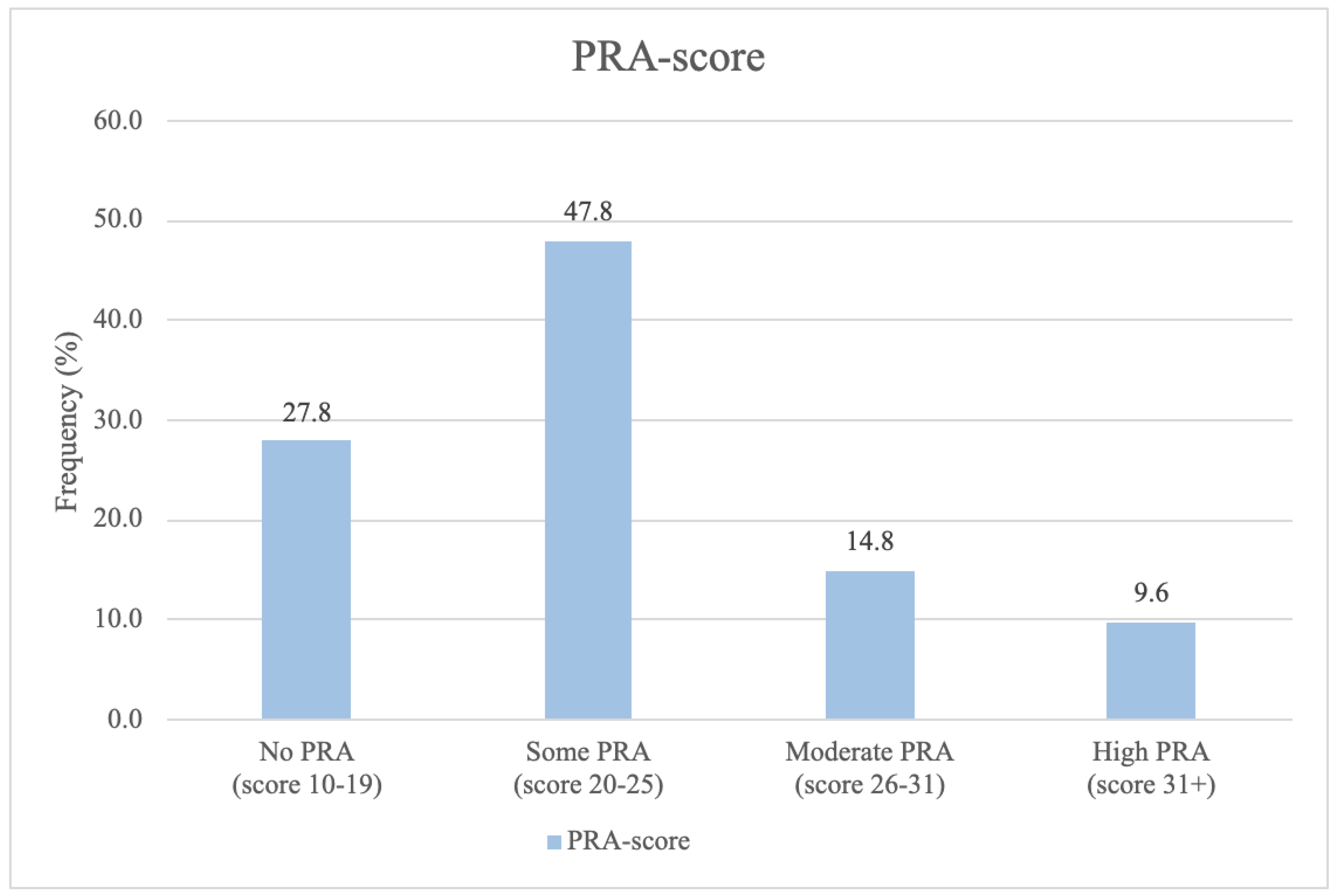

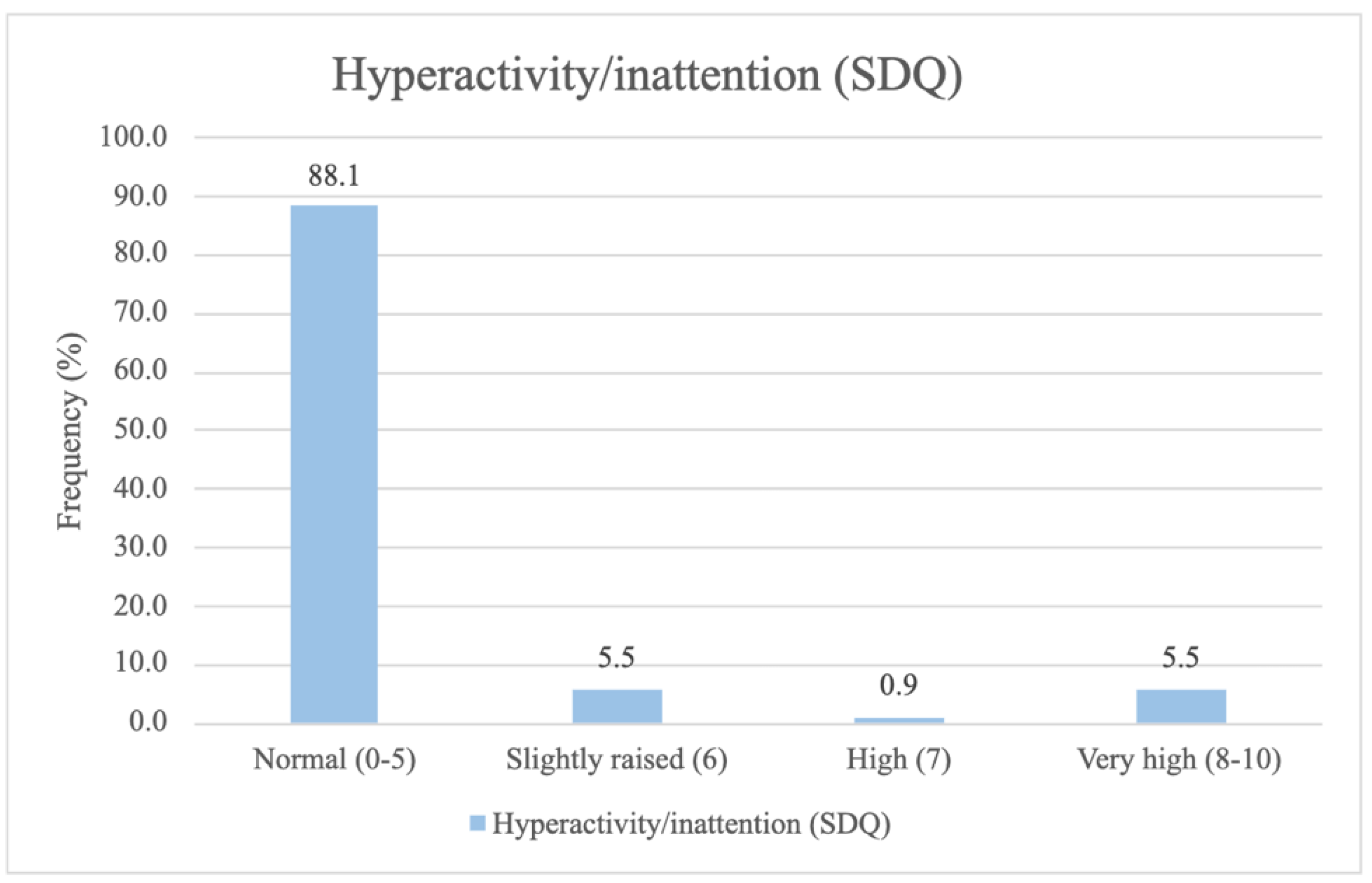

The frequency distribution for the psychological outcome subdomains,

Attention and concentration (FTF),

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity (FTF) and

Hyperactivity or Inattention (SDQ) for the children, is categorically depicted in

Figure 3.

Most of the children scored within the normal range across all three attention deficit subdomains studied. Approximately one in eight children had a slightly raised, high, or very high score on Hyperactivity and Inattention (SDQ), and/or a moderate or severe score on Attention and concentration (FTF). Lastly, approximately one in five children had a moderate or severe score on Hyperactivity and Impulsivity (FTF).

The correlation analysis between the three psychological outcome measures (

Hyperactivity and inattention disorders, SDQ;

Attention and concentration, FTF;

Hyperactivity and impulsivity, FTF), showed that these were significantly correlated as shown in

Supplementary Materials (

Table S2).

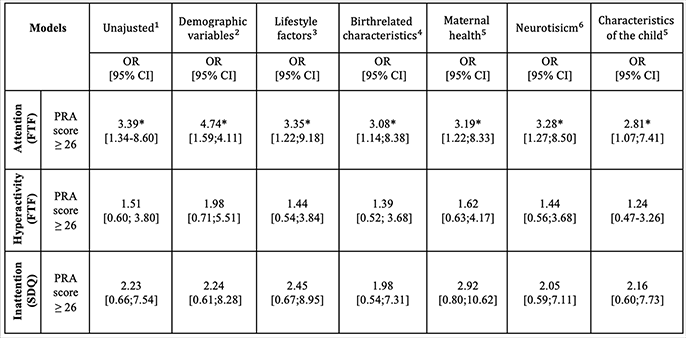

The examination of the association between PRA and the three psychological measures for attention deficits among 5-year-old children:

Attention and concentration, FTF;

Hyperactivity and impulsivity, FTF,

Hyperactivity and inattention disorders, SDQ), showed a statistically significant association for

Attention and concentration (FTF) (

Table 2). Women with high PRA during their pregnancy (≥26) showed an increased risk of having children with a score above the cutoff for attention deficits (≥4), compared to women with low PRA (<26). The association remained significant when adjusting for potential confounding factors in all of the models (2-7). No significant association was found for the subdomains

Hyperactivity and impulsivity (FTF) and

Hyperactivity and inattention (SDQ). No statistically significant effects were found between the biological stress measures (fetal cortisol, maternal cortisol, AFCE) and children's attention deficits (results not shown).

A significant interaction was found between PRA and parity (see

Table 1). When stratifying by parity, no statistically significant association was found among the primiparous women. However, a significant association was found between PRA and attention deficit in children at the age of 5 years, among multiparous women. The group of multiparous women at MSPF 2015 with high PRA during their pregnancy (≥26) showed an increased risk of having children with a score above the cutoff for attention deficits at the age of 5 (≥4) (OR = 9.07), compared to the multiparous women without PRA (

Table 3). The results remain significant after adjusting for potential confounding factors in all of the models (models 2-7). The OR more than doubled when adjusting for demographic variables. Conversely, the OR decreased, when adjusted for the child's characteristics.

4. Discussion

Using a diverse set of stress measures, both biological and self-reported, to assess prenatal stress exposure, we found no associations for the biological stress markers in this study. Notably, we found an association between self-reported pregnancy-related anxiety (PRA) and parent-reported Attention and Concentration (FTF) in a normal population of women and their 5-year-old children. When stratifying for parity, the association was significant among multiparous women with high PRA (≥ 26), indicating an increased risk for attention deficits in their 5-year-old children.

Previous studies have found effects of prenatal maternal stress on the risk of symptoms of attention disorders, symptoms of ADHD, or diagnosed ADHD in children (Li et al., 2010; MacKinnon et al., 2018; Shao et al., 2020; Shih et al., 2022; Spence et al., 2001; Zhu et al., 2015). These studies show substantial differences in exposure measures ranging from self-reported stressful life events during pregnancy to assessments of pregnancy-related anxiety symptoms utilizing the Pregnancy-related Anxiety Questionnaire (MacKinnon et al., 2018; Shao et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2015), self-reported job stress during pregnancy (Shih et al., 2022), and prenatal maternal bereavement (Li et al., 2010). In addition, outcome measures range from parent-reported ADHD symptoms in children using different questionnaires as Conners' Hyperactivity Index and the child behavior checklist, to hospital diagnoses of ADHD. The use of statistical methods and inclusion of covariates also differ among these studies. Although there are differences in the compared studies, there are clear associations between psychological stress during pregnancy and attention deficits in the children.

In our study we did not find any difference regarding the sex of the child on attentional capacity. This is contrary to three previous studies on prenatal pregnancy-related anxiety and stress (Shao et al., 2020; Trillingsgaard et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2015), but consistent with two studies examining prenatal stressful events (MacKinnon et al., 2018; Ronald et al., 2011), and similar to one study on maternal job stress during pregnancy (Shih et al., 2022). Our study investigated attention deficits using the questionnaires FTF and SDQ, whereas Zhu, Shao and Li used ADHD symptoms measured by Conner´s Hyperactivity Index (Conners et al., 1998) or diagnosed ADHD (ICD 10 code F90). Evidence indicates that ADHD is found more often in boys, with ADHD tests typically being more sensitive in detecting symptoms in boys than girls (Slobodin and Davidovitch, 2019). Shao et al. demonstrated how prenatal pregnancy-related anxiety predicts ADHD symptoms in boys. They utilized the Pregnancy-related Anxiety Questionnaire (PRAQ). Our approach, employing comprehensive measures, strengthens our study by providing a more complete understanding of the complex interplay between prenatal stress and attention deficits. While we did not observe any sex differences in attentional capacity, it is noteworthy that other studies have reported such disparities. This could be attributed to the potential biases in diagnosing ADHD, and there might be underlying biological distinctions in how stress hormones affects the placenta and fetal development, as indicated by research in both human and animal models (Galbally et al., 2022; Glover and Hill, 2012). It is plausible that our study did not detect these differences, perhaps due to limitations in sample size or other factors.

It is important to note that in our study, we focused on two subdomains from the questionnaire FTF (Attention and concentration and Hyperactivity and impulsivity) and one subdomain from the questionnaire SDQ (Hyperactivity and Inattention). While we only found significant association using the subdomain Attention and concentration, it is possible that the other subdomains were not as sensitive or perhaps measured different aspects of attention problems.

The majority of studies on prenatal stress includes participants with a potentially high stress exposure, and primarily focuses on women experiencing severe mental stressors or diagnosed with depression or anxiety (MacKinnon et al., 2018; Ronald et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2015). In contrast, our study represents a low-risk population of women experiencing a normal level of stress during pregnancy. Even in this relatively unselected population, we find a significant effect of maternal prenatal anxiety, which makes our results relevant to a larger population of women. Accordingly, we investigated whether certain groups of mothers are particularly sensitive to prenatal anxiety, expecting primiparous women to have particularly many concerns about their first pregnancy and parental role. Therefore, it was contrary to our expectations that no association was found for the primiparous women. Conversely, this suggests that multiparous women experience pregnancy-related concerns that have a greater impact on risk for attention deficit in their 5-year-old children, as a statistically significant association was observed for this group. In addition, it highlights the need for public awareness on the effects of even low levels of pregnancy related anxiety and stress during pregnancy.

4.1. Interpretation

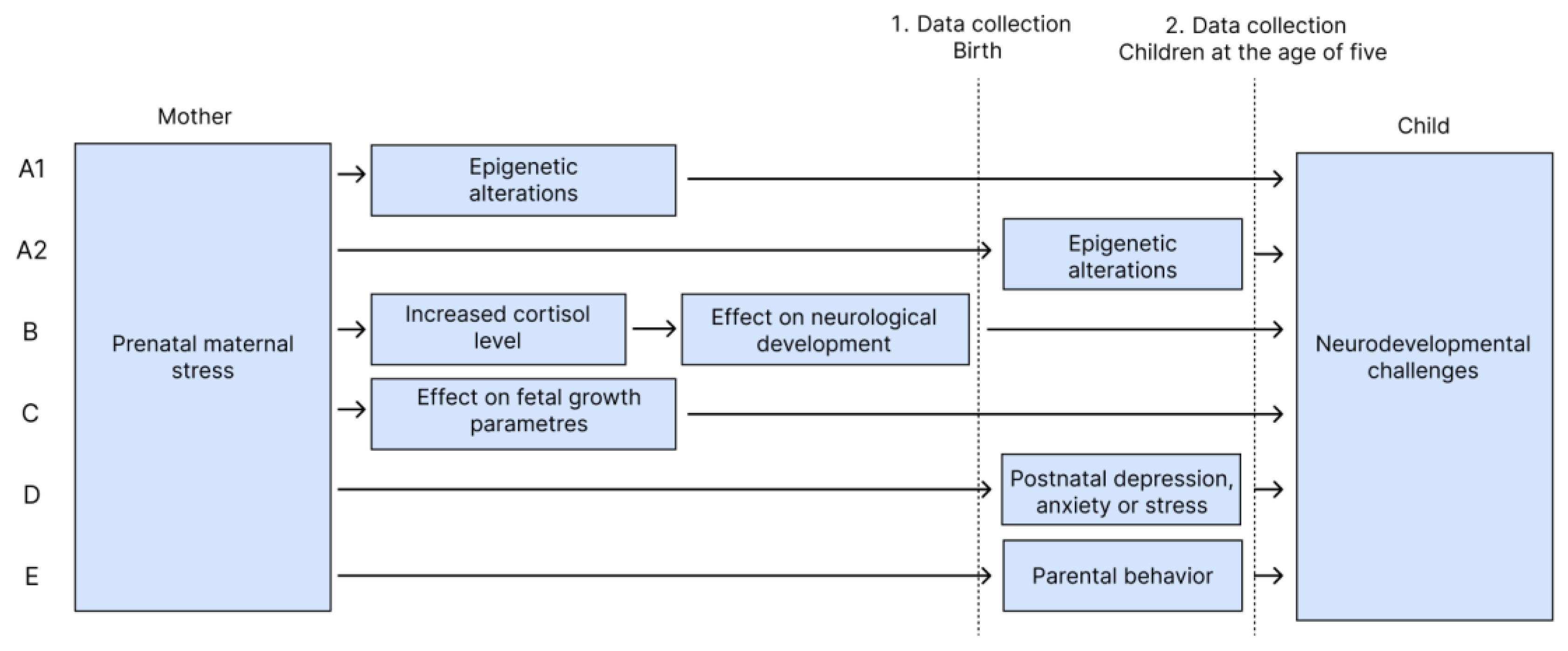

There are several possible pathways between prenatal maternal stress and developmental effects in children. We highlight five causal explanations (A-E) (

Figure 4).

4.1.1. A. Epigenetic Alterations

One potential explanation for our findings is epigenetic alterations. Several studies explain the importance of epigenetic alterations, when genes interact with the environment as an underlying mechanism in the correlation between stress and attention deficits in children (Glover, 2015; Hompes et al., 2013; Mulligan et al., 2012). Epigenetic alterations occur when environmental influences, such as lifestyle factors, alter gene expression without altering the DNA sequence in itself (Wilcox, 2010). For this mechanism, determination of causality is challenging in this study, because fetal epigenetics can be influenced by both the mother's environment during pregnancy and/or the children's developmental environment. Hence PRA as a prenatal environmental factor may have influenced children's epigenetics and led to attention deficits (Glover, 2015). Similarly, early childhood exposures such as parental attachment deficiencies or exposure to toxic drugs also induces epigenetic alterations (Silk et al., 2022). Environmental exposure measurements in this study, including the mother's self-reported PRA and DASS during pregnancy or DASS during childhood measured at the 5-year follow-up, are potential factors influencing child epigenetics. It would have been feasible to assess the epigenetic changes, by using biological measures from birth. We have not conducted measurements of epigenetic changes, due to lack of biological samples at the age of five.

4.1.2. B. Increased Prenatal Fetal Cortisol Exposure

Prolonged exposure to increased maternal cortisol levels might influence fetal neuroendocrine regulation and brain development, potentially resulting in various developmental disorders such as attention disorders (Glover, 2015; Jeon et al., 2021; Zijlmans et al., 2015). Maternal and umbilical cord cortisol levels were measured postpartum, allowing this hypothesis to be investigated. However, the analyses found no significant difference in fetal cortisol exposure related to the children's attentional capacity at the age of five.

4.1.3. C. Affected Fetal Growth Parameters

Experiencing anxiety, depression, or high levels of stress-related hormones during pregnancy is associated with reduced fetal growth parameters (Bolten et al., 2011; Henrichs et al., 2010; Van Dijk et al., 2010). Low birth weight itself is a risk factor of developing ADHD (Hatch et al., 2014). Similar other risk factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy may induce low birth weight (Abel, 1982). Hence, fetal growth parameters may mediate the causal pathway between PRA and attention deficits in the child. This hypothesis was examined in this study by adjusting for the child's birth weight in the analyses. After adjustment, the risk decreased, indicating the relevance of growth parameters to the association.

4.1.4. D+E. Postnatal Effects

Postnatal exposures such as parental anxiety, depression, stress and parental behavior can affect children's development during childhood since the mother's mental health is an environmental risk factor that contributes to the child's vulnerability for developing ADHD (Class et al., 2014). According to Clayborne et al. (2021) the association between prenatal maternal stress and children's mental health was found to be modified by parental behavior and parenting style (Clayborne et al., 2023). Hence, parenting and child-rearing may impact the child (Glover, 2015; Okano et al., 2019). Measurements of mothers' DASS at follow-up (2nd data collection) were correlated with the baseline measurement in 2015, indicating no difference in the mothers' mental health. Therefore, the analyses were not adjusted for DASS. Adjustment for neuroticism as a confounder in all analyses was necessary due to the possibility of anxious personality traits in stressed parents. Risk of attention deficits slightly decreased after adjustment, suggesting neuroticism's relevance to the association.

The cause of attention deficits is a complex interplay between several causal explanations. Our study design enabled the investigation of individual parameters in hypothesis B, C and E, and our findings support the influence of fetal growth parameters (C) and parental behavior (E) as plausible underlying mechanisms. Contrary to expectations, no association was found between biological stress makers and attention deficits, which can be due to methodological challenges in our test-strategy: most importantly the influence of birth method and birth strain on maternal hormone levels directly after birth (Dahlerup et al., 2018).

4.2. Methodological Considerations

This study has several strengths. Firstly, the study is based on a prospective cohort study, providing a strong argument for causality. Secondly, the study utilized highly validated questionnaires (The Danish Social Services Agency, 2013; Trillingsgaard et al., 2004), which strengthens the measurement of both exposure and outcome, thus supporting the validity of the findings. Thirdly, the extensive collection of information on the women enabled controlling for a wide range of confounders (e.g., maternal age, income, education level, BMI, chronic illness, medication use, type of birth, pregnancy complications, neuroticism, child's sex, birth weight). This ensured a more precise estimation of the effect of prenatal maternal stress on the child's attentional capacity. Lastly examining children's development at the age of 5 holds significance as symptoms of ADHD typically begin to emerge around this time (The Danish Mental Health Fund, nd).

We included biological stress hormones measured at birth in both mother and umbilical cord, and the calculated adjusted fetal cortisol exposure (AFCE) in our analyses, but these did not show any association to the parent-reported outcome measures. The stress-hormones were intercorrelated, and in the baseline population (2015), they showed correlation with PRA, but in this smaller follow-up subset of the population, only PRA as exposure was sensitive enough to attain significant association with our outcome measures of attention deficits at five years of age. Cortisol is a challenging hormone to use as an exposure measure when investigating pregnant women. This is because during pregnancy and especially immediately after childbirth, cortisol reflects more on pregnancy, the type of delivery, and level of birth strain, rather than indicating the overall wellbeing of the pregnant woman, during the pregnancy (Dahlerup et al., 2018).

Even though the access to analyses of biological samples is a strength, the study also has several limitations. Because of the resource-intensive data collection due to biological samples, the follow-up study with 45% recruitment success consisted of only 115 mother-child pairs. When stratifying by parity, educational level, smoking and alcohol consumption, respectively, the groups were further reduced in size. Therefore, it remains uncertain whether the non-significant findings of the stratified analyses were due to the small sample size. Statistical power limitations also prevented adjusting for all potential confounders in one model, necessitating separate adjustment for confounder groups, leading to seven sub-analyses (model 1-7).

There is a risk of residual confounding due to merging income groups for anonymity purposes and categorizing smoking and alcohol intake during pregnancy in binary terms, potentially oversimplifying the significance of confounders. Furthermore, there may be unmeasured confounding, such as genetic predisposition for ADHD, exposure to environmental factors during pregnancy or heritability for ADHD, which could not be adjusted for (ADHD Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) et al., 2019; Dalsager et al., 2019). Previous twin studies from high-income countries suggest that genes and their interaction with the environment play a substantial role in the development of ADHD. However, the heritability of ADHD fluctuates over the life course, and determining causality for specific environmental factors is challenging (Faraone et al., 2021; Faraone & Larsson, 2019; Larsson et al., 2013).

Women scheduled to give birth at Copenhagen University Hospital were invited to participate in the MSPF project, and the study population was selected based on residency. The majority of the participants had a medium or long higher education and a medium or high income, representing a resourceful population. Depression, anxiety, and stress are diseases that reduce motivation and energy; hence women suffering from these conditions may not have participated or might have dropped out by the time of the follow-up, confirmed by the overall low scores on the three domains in the study population. The study population is an overall healthy population, suggesting that a stronger association might be found by examining a more representative sample from the target population.

4.3. Public Health Impact

The analysis of the PRA questionnaire revealed a concern among the pregnant woman on the topic of childbirth (

Figure S1). There was media's attention on increased busyness in delivery wards and exhausted midwives throughout Denmark around the time of the first sample collection of the Maternal Stress and Placental Function cohort (Denmarks Radio, 2016a, 2016b,

Walking in the Shoes of the midwife: 12 days in October 2015, 2015). This may have caused concerns in our participating women. By investing in alleviating these concerns, we may reduce pregnancy-related anxieties, potentially reducing the occurrence of attention deficits in children. Our study thus highlights a possible high societal impact of prioritizing delivery and maternity ward antenatal preparation to address childbirth-related anxieties in pregnant women.

5. Conclusions

In this prospective study of 115 mother-child pairs we investigated maternal stress as a risk factor of children's attention deficits at 5 years. No significant associations were found for the biological stress markers. However, we found significant associations between self-reported pregnancy-related anxiety and attention deficits in the children 5 years later. The association remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders. Previous research primarily focuses on populations experiencing severe mental distress or diagnosed with depression or anxiety. The findings of our study provide valuable insights into the risk of attention deficits among children in a population of women with low to moderate stress levels during pregnancy, emphasizing its relevance to a broader population of women, beyond those with severe mental health issues.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

The original study at birth was funded by the AFAAR/NEAVS Fellowship Grant for Alternatives to Animal Research in Women's Health and Sex Differences in 2015. We gratefully acknowledge the participating families. The data, code and materials necessary to reproduce the analyses presented here are not publicly accessible. Analyses were not pre-registered.

Abbreviations

AFDE: Adjusted Fetal Cortisol Exposure, DASS: Depression Anxiety Stress scales, FTF: Five to Fifteen questionnaire, MSPF: Maternal Stress and Placental Function project, PRA: Pregnancy Related Anxiety, SDQ: Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire.

References

- Abel, E.L., 1982. Consumption of alcohol during pregnancy: a review of effects on growth and development of offspring. Hum Biol 54, 421–453.

- ADHD Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC), Early Lifecourse & Genetic Epidemiology (EAGLE) Consortium, 23andMe Research Team, Demontis, D., Walters, R.K., Martin, J., Mattheisen, M., Als, T.D., Agerbo, E., Baldursson, G., Belliveau, R., Bybjerg-Grauholm, J., Bækvad-Hansen, M., Cerrato, F., Chambert, K., Churchhouse, C., Dumont, A., Eriksson, N., Gandal, M., Goldstein, J.I., Grasby, K.L., Grove, J., Gudmundsson, O.O., Hansen, C.S., Hauberg, M.E., Hollegaard, M.V., Howrigan, D.P., Huang, H., Maller, J.B., Martin, A.R., Martin, N.G., Moran, J., Pallesen, J., Palmer, D.S., Pedersen, C.B., Pedersen, M.G., Poterba, T., Poulsen, J.B., Ripke, S., Robinson, E.B., Satterstrom, F.K., Stefansson, H., Stevens, C., Turley, P., Walters, G.B., Won, H., Wright, M.J., Andreassen, O.A., Asherson, P., Burton, C.L., Boomsma, D.I., Cormand, B., Dalsgaard, S., Franke, B., Gelernter, J., Geschwind, D., Hakonarson, H., Haavik, J., Kranzler, H.R., Kuntsi, J., Langley, K., Lesch, K.-P., Middeldorp, C., Reif, A., Rohde, L.A., Roussos, P., Schachar, R., Sklar, P., Sonuga-Barke, E.J.S., Sullivan, P.F., Thapar, A., Tung, J.Y., Waldman, I.D., Medland, S.E., Stefansson, K., Nordentoft, M., Hougaard, D.M., Werge, T., Mors, O., Mortensen, P.B., Daly, M.J., Faraone, S.V., Børglum, A.D., Neale, B.M., 2019. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet 51, 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Bolten, M.I., Wurmser, H., Buske-Kirschbaum, A., Papoušek, M., Pirke, K.-M., Hellhammer, D., 2011. Cortisol levels in pregnancy as a psychobiological predictor for birth weight. Arch Womens Ment Health 14, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, M., Paray, A.A., 2024. Natural Physiological Changes During Pregnancy. Yale J Biol Med 97, 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Class, Q.A., Abel, K.M., Khashan, A.S., Rickert, M.E., Dalman, C., Larsson, H., Hultman, C.M., Långström, N., Lichtenstein, P., D‘Onofrio, B.M., 2014. Offspring psychopathology following preconception, prenatal and postnatal maternal bereavement stress. Psychol. Med. 44, 71–84. [CrossRef]

- Clayborne, Z.M., Nilsen, W., Torvik, F.A., Gustavson, K., Bekkhus, M., Gilman, S.E., Khandaker, G.M., Fell, D.B., Colman, I., 2023. Prenatal maternal stress, child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and the moderating role of parenting: findings from the Norwegian mother, father, and child cohort study. Psychol. Med. 53, 2437–2447. [CrossRef]

- Conners, C.K., Sitarenios, G., Parker, J.D.A., Epstein, J.N., 1998. [No title found]. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 26, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Dahlerup, B.R., Egsmose, E.L., Siersma, V., Mortensen, E.L., Hedegaard, M., Knudsen, L.E., Mathiesen, L., 2018. Maternal stress and placental function, a study using questionnaires and biomarkers at birth. PLoS ONE 13, e0207184. [CrossRef]

- Dalsager, L., Fage-Larsen, B., Bilenberg, N., Jensen, T.K., Nielsen, F., Kyhl, H.B., Grandjean, P., Andersen, H.R., 2019. Maternal urinary concentrations of pyrethroid and chlorpyrifos metabolites and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in 2-4-year-old children from the Odense Child Cohort. Environmental Research 176, 108533. [CrossRef]

- Denmarks Radio, 2016a. The Head Doctor of the Obstetrics Department at the University Hospital quits after 14 years due to poor working environment.

- Denmarks Radio, 2016b. Giving birth at the university hospital with very busy personnel made the mothers feel insecure.

- Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Zheng Y, Biederman J, Bellgrove MA, Newcorn JH, Gignac M, Al Saud NM, Manor I, Rohde LA, Yang L, Cortese S, Almagor D, Stein MA, Albatti TH, Aljoudi HF, Alqahtani MMJ, Asherson P, Atwoli L, Bölte S, Buitelaar JK, Crunelle CL, Daley D, Dalsgaard S, Döpfner M, Espinet S, Fitzgerald M, Franke B, Gerlach M, Haavik J, Hartman CA, Hartung CM, Hinshaw SP, Hoekstra PJ, Hollis C, Kollins SH, Sandra Kooij JJ, Kuntsi J, Larsson H, Li T, Liu J, Merzon E, Mattingly G, Mattos P, McCarthy S, Mikami AY, Molina BSG, Nigg JT, Purper-Ouakil D, Omigbodun OO, Polanczyk GV, Pollak Y, Poulton AS, Rajkumar RP, Reding A, Reif A, Rubia K, Rucklidge J, Romanos M, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Schellekens A, Scheres A, Schoeman R, Schweitzer JB, Shah H, Solanto MV, Sonuga-Barke E, Soutullo C, Steinhausen HC, Swanson JM, Thapar A, Tripp G, van de Glind G, van den Brink W, Van der Oord S, Venter A, Vitiello B, Walitza S, Wang Y. The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021 Sep;128:789-818. Epub 2021 Feb 4. PMID: 33549739; PMCID: PMC8328933. [CrossRef]

- Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;24(4):562-575. Epub 2018 Jun 11. PMID: 29892054; PMCID: PMC6477889. [CrossRef]

- Galbally, M., Watson, S.J., Lappas, M., De Kloet, E.R., Wyrwoll, C.S., Mark, P.J., Lewis, A.J., 2022. Exploring sex differences in fetal programming for childhood emotional disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 141, 105764. [CrossRef]

- Gjerstad, J.K., Lightman, S.L., Spiga, F., 2018. Role of glucocorticoid negative feedback in the regulation of HPA axis pulsatility. Stress 21, 403–416. [CrossRef]

- Glover, V., 2015. Prenatal stress and its effects on the fetus and the child: possible underlying biological mechanisms. Adv Neurobiol 10, 269–283. [CrossRef]

- Glover, V., Bergman, K., Sarkar, P., O’Connor, T.G., 2009. Association between maternal and amniotic fluid cortisol is moderated by maternal anxiety. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, 430–435. [CrossRef]

- Glover, V., Hill, J., 2012. Sex differences in the programming effects of prenatal stress on psychopathology and stress responses: An evolutionary perspective. Physiology & Behavior 106, 736–740. [CrossRef]

- Hatch, B., Healey, D.M., Halperin, J.M., 2014. Associations between birth weight and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom severity: indirect effects via primary neuropsychological functions. Child Psychology Psychiatry 55, 384–392. [CrossRef]

- Henrichs, J., Schenk, J.J., Roza, S.J., Van Den Berg, M.P., Schmidt, H.G., Steegers, E.A.P., Hofman, A., Jaddoe, V.W.V., Verhulst, F.C., Tiemeier, H., 2010. Maternal psychological distress and fetal growth trajectories: The Generation R Study. Psychol. Med. 40, 633–643. [CrossRef]

- Hompes, T., Izzi, B., Gellens, E., Morreels, M., Fieuws, S., Pexsters, A., Schops, G., Dom, M., Van Bree, R., Freson, K., Verhaeghe, J., Spitz, B., Demyttenaere, K., Glover, V., Van Den Bergh, B., Allegaert, K., Claes, S., 2013. Investigating the influence of maternal cortisol and emotional state during pregnancy on the DNA methylation status of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) promoter region in cord blood. Journal of Psychiatric Research 47, 880–891. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.-C., Kim, H.-J., Ko, E.-A., Jung, S.-C., 2021. Prenatal Exposure to High Cortisol Induces ADHD-like Behaviors with Delay in Spatial Cognitive Functions during the Post-weaning Period in Rats. Exp Neurobiol 30, 87–100. [CrossRef]

- Kadesjø, B., Janols, L.-O., Korkman, M., Mickelsson, K., Strand, G., Trillingsgaard, A., Gillberg, C., 2004. The FTF (Five to Fifteen): the development of a parent questionnaire for the assessment of ADHD and comorbid conditions. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 13, iii3–iii13. [CrossRef]

- Larsson H, Chang Z, D'Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P. The heritability of clinically diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Psychol Med. 2014 Jul;44(10):2223-9. Epub 2013 Oct 10. PMID: 24107258; PMCID: PMC4071160. [CrossRef]

- Lautarescu, A., Craig, M.C., Glover, V., 2020. Prenatal stress: Effects on fetal and child brain development, in: International Review of Neurobiology. Elsevier, pp. 17–40. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Olsen, J., Vestergaard, M., Obel, C., 2010. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the offspring following prenatal maternal bereavement: a nationwide follow-up study in Denmark. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 19, 747–753. [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, N., Kingsbury, M., Mahedy, L., Evans, J., Colman, I., 2018. The Association Between Prenatal Stress and Externalizing Symptoms in Childhood: Evidence From the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Biological Psychiatry 83, 100–108. [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.I., Ressler, K.J., Binder, E., Nemeroff, C.B., 2009. The Neurobiology of Anxiety Disorders: Brain Imaging, Genetics, and Psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 32, 549–575. [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, C., D’Errico, N., Stees, J., Hughes, D., 2012. Methylation changes at NR3C1 in newborns associate with maternal prenatal stress exposure and newborn birth weight. Epigenetics 7, 853–857. [CrossRef]

- Okano, L., Ji, Y., Riley, A.W., Wang, X., 2019. Maternal psychosocial stress and children’s ADHD diagnosis: a prospective birth cohort study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 40, 217–225. [CrossRef]

- Psychology Foundation of Australia, 2022. Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS).

- Ronald, A., Pennell, C.E., Whitehouse, A.J.O., 2011. Prenatal Maternal Stress Associated with ADHD and Autistic Traits in early Childhood. Front. Psychology 1. [CrossRef]

- Schytt, E., Hildingsson, I., 2011. Physical and emotional self-rated health among Swedish women and men during pregnancy and the first year of parenthood. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare 2, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- SDQ-INFO, n.d. Information for researchers and professionals about the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaires. URL https://www.sdqinfo.org/ (accessed 4.23.23).

- Shao, S., Wang, J., Huang, K., Wang, S., Liu, H., Wan, S., Yan, S., Hao, J., Zhu, P., Tao, F., 2020. Prenatal pregnancy-related anxiety predicts boys’ ADHD symptoms via placental C-reactive protein. Psychoneuroendocrinology 120, 104797. [CrossRef]

- Shih, P., Huang, C., Chiang, T., Chen, P.-C., Guo, Y.L., 2022. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children related to maternal job stress during pregnancy in Taiwan: a prospective cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 95, 1231–1241. [CrossRef]

- Silk, T., Dipnall, L., Wong, Y.T., Craig, J.M., 2022. Epigenetics and ADHD, in: Stanford, S.C., Sciberras, E. (Eds.), New Discoveries in the Behavioral Neuroscience of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 269–289. [CrossRef]

- Slobodin, O., Davidovitch, M., 2019. Gender Differences in Objective and Subjective Measures of ADHD Among Clinic-Referred Children. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 441. [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.H., Rapee, R., McDonald, C., Ingram, M., 2001. The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behaviour Research and Therapy 39, 1293–1316. [CrossRef]

- Stübner, C., Flynn, T., Gillberg, C., Fernell, E., Miniscalco, C., 2020. Schoolchildren with unilateral or mild to moderate bilateral sensorineural hearing loss should be screened for neurodevelopmental problems. Acta Paediatrica 109, 1430–1438. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., Luo, C., Zeng, X., Wu, Q., 2024. The relationship between pregnancy stress and mental health of the pregnant women: the bidirectional chain mediation roles of mindfulness and peace of mind. Front. Psychol. 14, 1295242. [CrossRef]

- Tarafa, H., Alemayehu, Y., Nigussie, M., 2022. Factors associated with pregnancy-related anxiety among pregnant women attending antenatal care follow-up at Bedelle general hospital and Metu Karl comprehensive specialized hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Front. Psychiatry 13, 938277. [CrossRef]

- The Danish Mental Health Fund, nd. ADHD. URL https://psykiatrifonden.dk/diagnoser/adhd (accessed 5.24.23).

- The Danish Social Services Agency, 2013. Description of validated instruments for evaluations in the social sector.

- Trillingsgaard, A., Damm, D., Sommer, S., Jepsen, J.R.M., Østergaard, O., Frydenberg, M., Thomsen, P.H., 2004. Developmental profiles on the basis of the FTF (Five to Fifteen) questionnaire: Clinical validity and utility of the FTF in a child psychiatric sample. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 13, iii39–iii49. [CrossRef]

- Trillingsgaard, A. et al., 2005. Dansk Manual. 5-15 (FTF) Nordisk skema til vurdering af børns udvikling og adfærd. Vejledning til administration og scoring.

- Van Den Bergh, B.R.H., Van Den Heuvel, M.I., Lahti, M., Braeken, M., De Rooij, S.R., Entringer, S., Hoyer, D., Roseboom, T., Räikkönen, K., King, S., Schwab, M., 2020. Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 117, 26–64. [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, A.E., Van Eijsden, M., Stronks, K., Gemke, R.J.B.J., Vrijkotte, T.G.M., 2010. Maternal depressive symptoms, serum folate status, and pregnancy outcome: results of the Amsterdam Born Children and their Development study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 203, 563.e1-563.e7. [CrossRef]

- Walking in the Shoes of the midwife: 12 days in October 2015, 2015.

- Wilcox, A.J., 2010. Fertility and pregnancy: an epidemiologic perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford ; New York.

- World Health Organization, 2021. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030.

- Zhu, P., Hao, J.-H., Tao, R.-X., Huang, K., Jiang, X.-M., Zhu, Y.-D., Tao, F.-B., 2015. Sex-specific and time-dependent effects of prenatal stress on the early behavioral symptoms of ADHD: a longitudinal study in China. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24, 1139–1147. [CrossRef]

- Zijlmans, M.A.C., Riksen-Walraven, J.M., De Weerth, C., 2015. Associations between maternal prenatal cortisol concentrations and child outcomes: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 53, 1–24. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).