Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

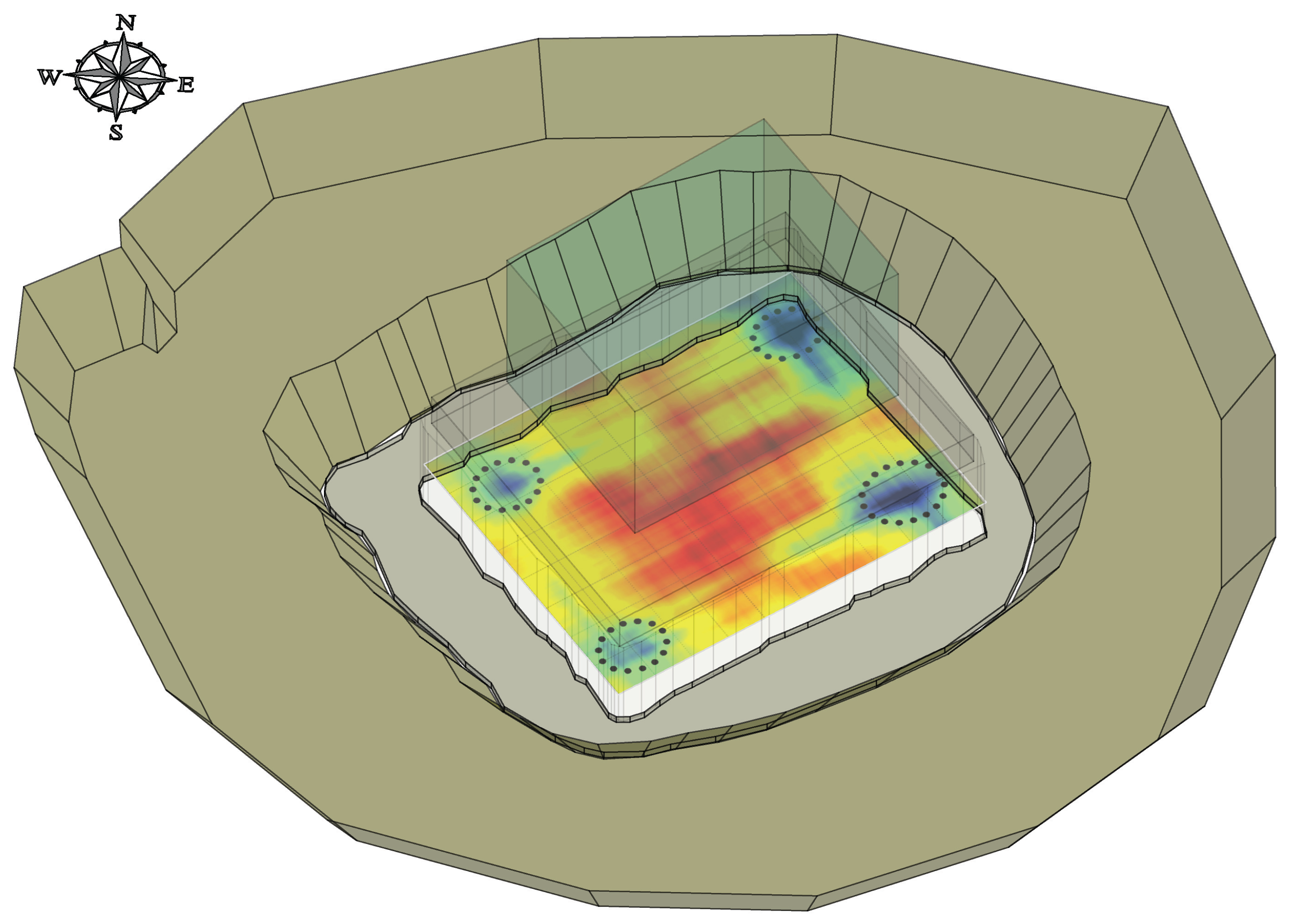

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

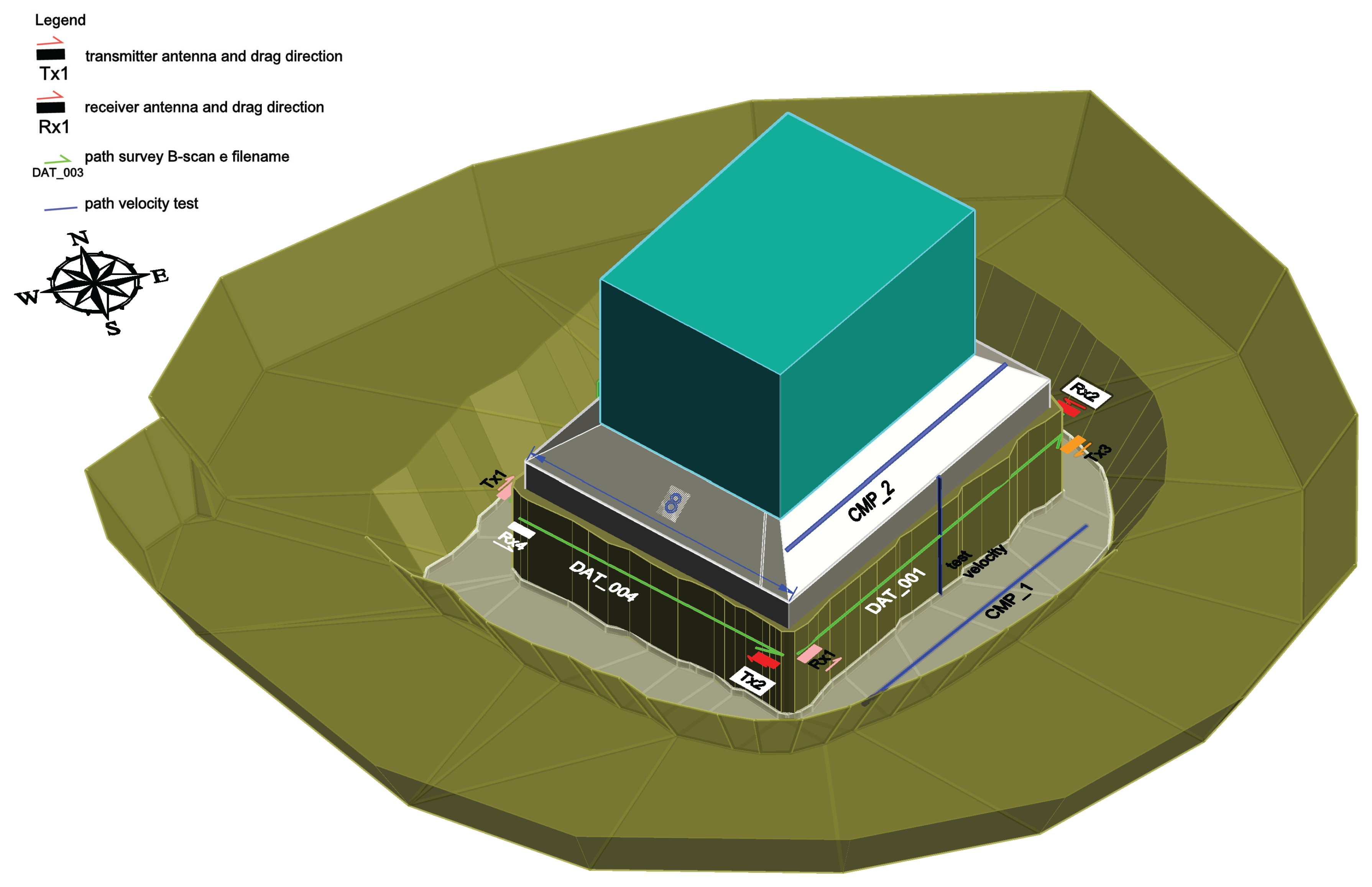

2.1. Geometry of the Site, B-Scans, and GPR Velocity Tests

2.2. GPR Instrumentation and Acquisition Parameters

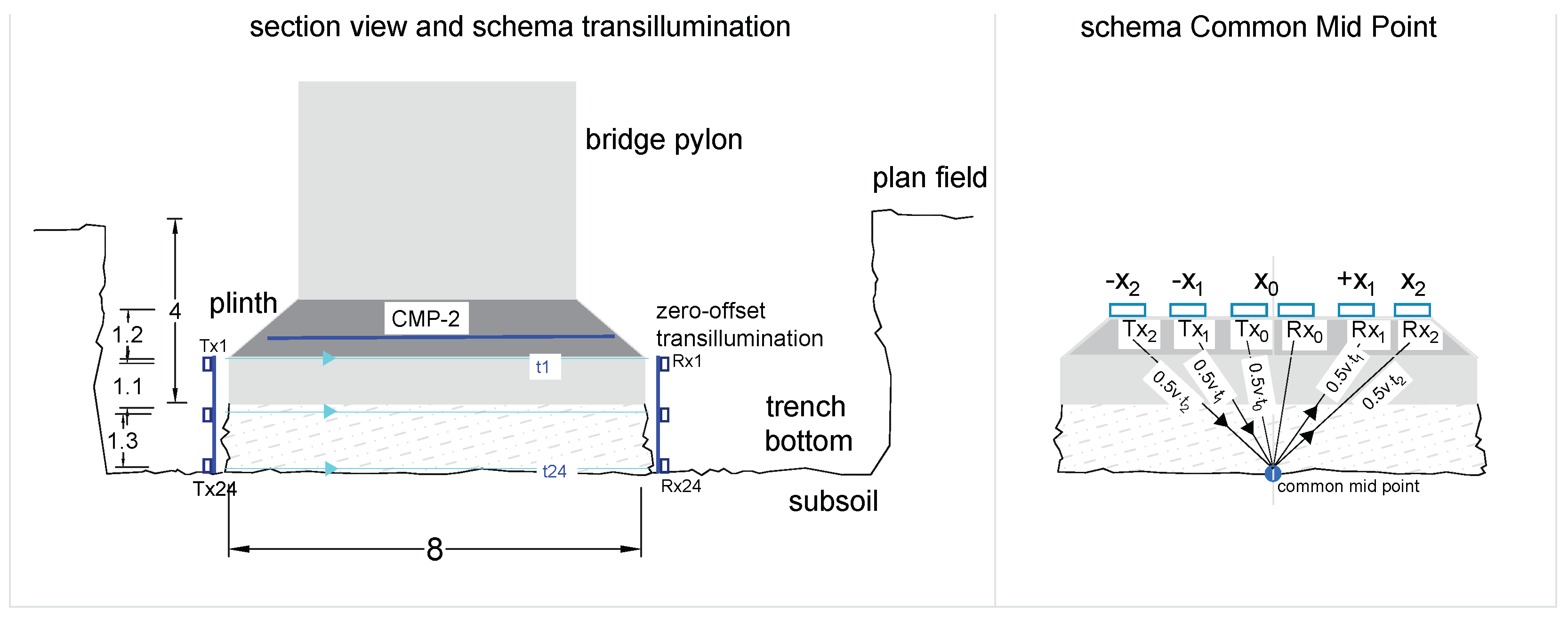

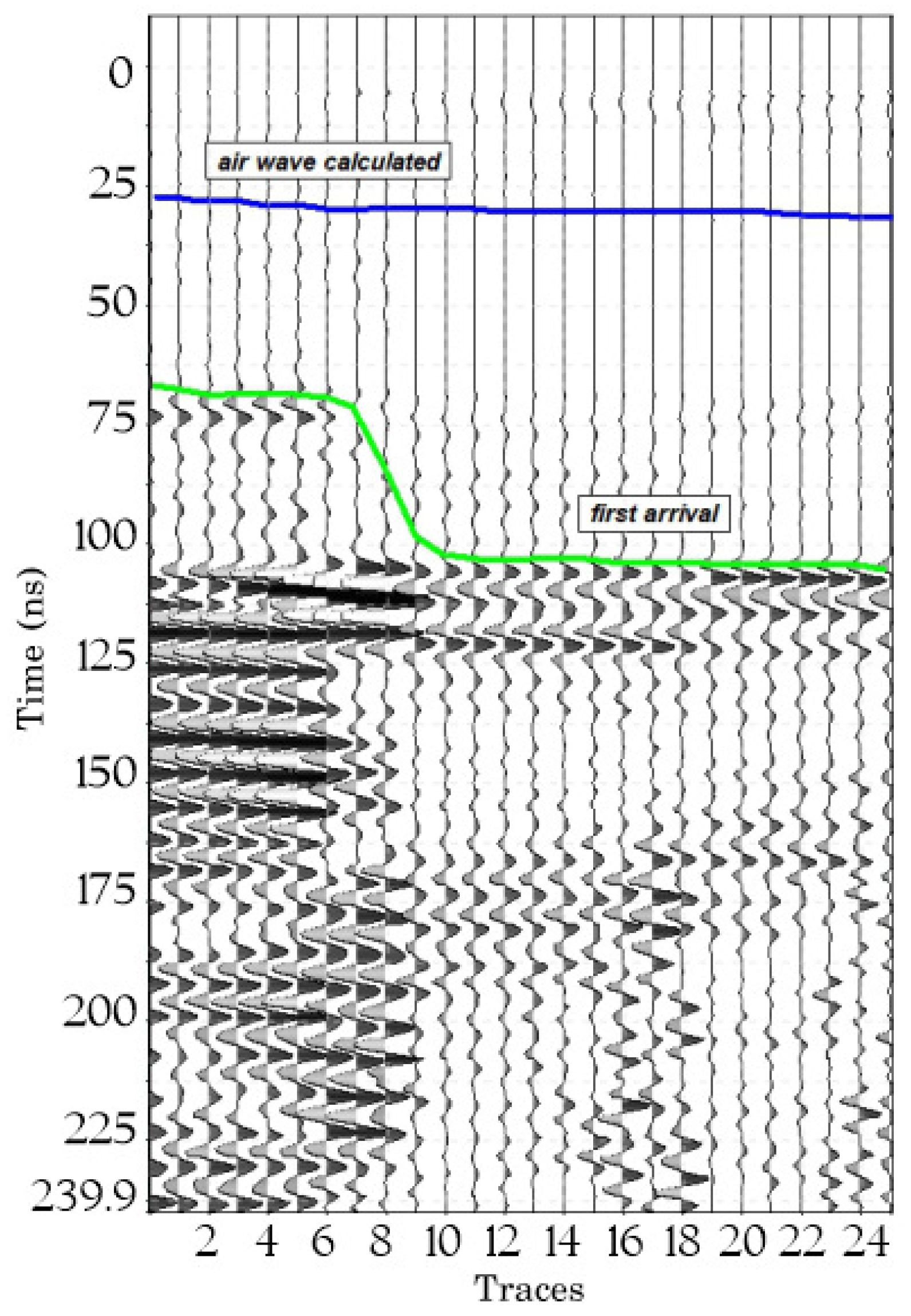

2.3. Direct In Situ Velocity Tests: CMP and Zero-Offset Transillumination

- 1 test Common Mid Point on the excavated bottom

- 1 test Common Mid Point on the exposed plinth

- 1 test transillumination zero-offset on the two faces of the short side of the foundation.

2.4. Acquisizione B-Scan gpr

| Time Window | Stack n. Traces | Sample n. | Realtime Filter | Wavelenght Medium | ; | Subfoot (m) | Mhz | Loss Tangent | Q-Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 ns | 4 | 512 | no | 0.27 m | 0.14; 0.07 | 2.2; 1.11 | 1280 | 2.24 | 30 |

2.5. Processing gpr Data

- time-zero correction to ensures that all reflections are correctly aligned by setting the airwave and direct wave of the trace at the first break point (or the first negative lobe) to a particular time-zero position

- background signal removal that is present at the beginning of a radar signal known as the direct wave dovuto all’accoppiamento dell’antenna con la faccia verticale della trincea. This part of the signal is considered as unwanted noise or clutter

- exponential gain to equalize the amplitude of the emitted wave, which suffers a significant attenuation along the medium

-

Ormsby bandpass filter along a trace for low-frequency interference and signal’s high-frequency components suppression. The algorithm used comprises three steps:application of direct FFT (fast Fourier transform) for transition from the time domain into the frequency domain of low-frequency and high-frequency trace spectrum components suppression and application of reverse FFT for transition from the frequency domain into the time domain

- time-depth conversion should be used for restructuring the initial time profile into a depth profile in compliance with the velocity areas.

2.6. Back Scattering Field Analysis (BSEF)

3. Results

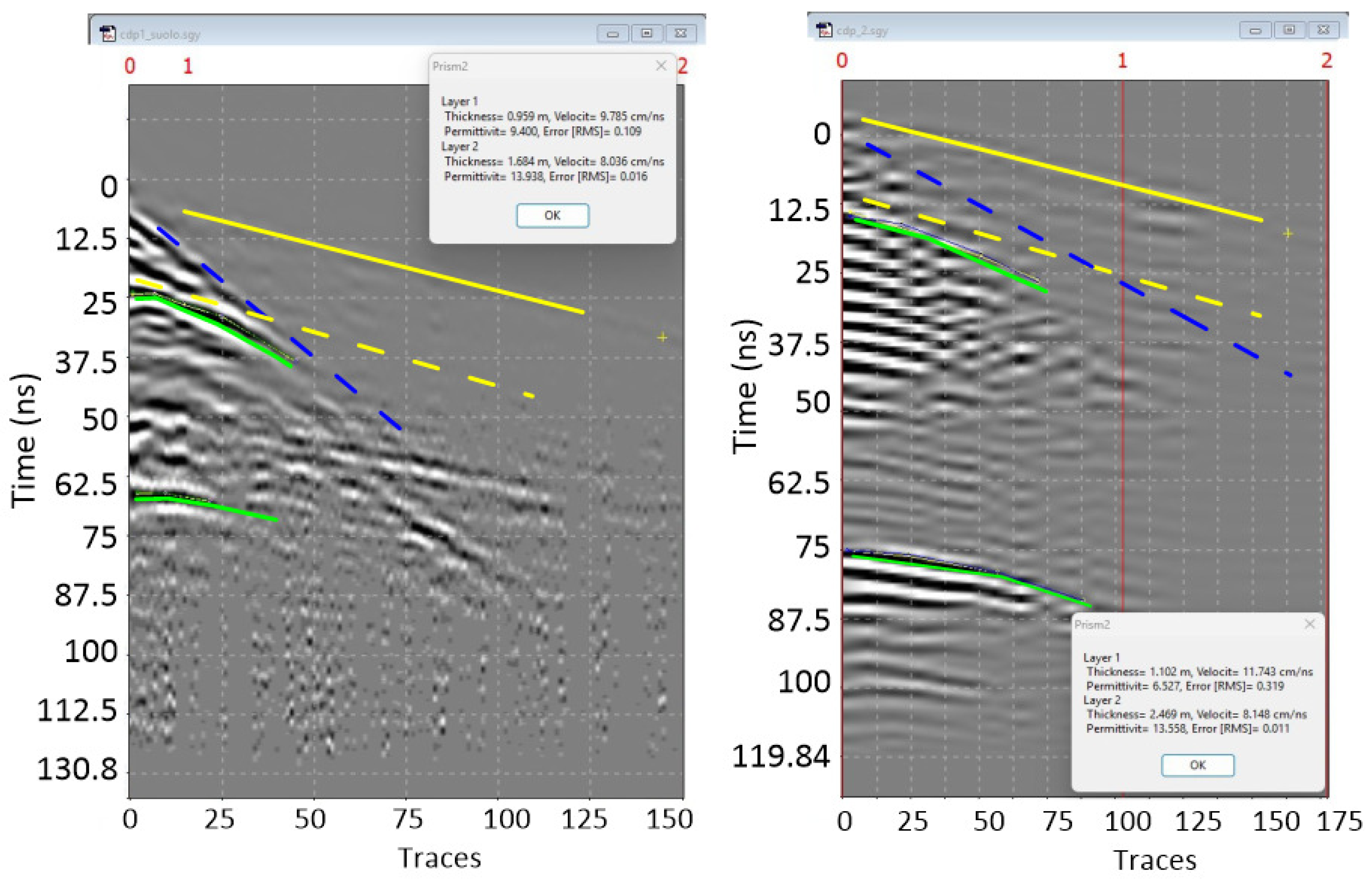

3.1. Velocity Test Results

| ID | Thickness (m) | Velocity (cm/ns) | Permittivity | Error [RMS] | Layer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMP1 on trench | 0.959 | 9.785 | 9.400 | 0.109 | 1 |

| 1.684 | 8.036 | 13.938 | 0.016 | 2 | |

| CMP2 on plynth | 1.102 | 11.743 | 6.527 | 0.319 | 1 |

| 2.469 | 8.148 | 13.558 | 0.001 | 2 |

| Trace | Depth (cm) | Distance (cm) | Time (ns) | Velocity (cm/ns) | |

| 1 | 0 | 800 | 65.27 | 12.26 | 5.98 |

| 2 | 10 | 800 | 66.86 | 11.97 | 6.28 |

| 3 | 20 | 800 | 67.44 | 11.86 | 6.39 |

| 4 | 30 | 800 | 66.86 | 11.97 | 6.28 |

| 5 | 40 | 800 | 66.86 | 11.97 | 6.28 |

| 6 | 50 | 800 | 66.86 | 11.97 | 6.28 |

| 7 | 60 | 800 | 67.44 | 11.86 | 6.39 |

| 8 | 70 | 800 | 69.2 | 11.56 | 6.73 |

| 9 | 80 | 800 | 85.04 | 9.41 | 10.15 |

| 10 | 90 | 800 | 96.18 | 8.32 | 12.99 |

| 11 | 100 | 800 | 97.94 | 8.17 | 13.47 |

| 12 | 110 | 800 | 97.94 | 8.17 | 13.47 |

| 13 | 120 | 800 | 98.52 | 8.12 | 13.63 |

| 14 | 130 | 800 | 99.11 | 8.07 | 13.79 |

| 15 | 140 | 800 | 99.7 | 8.02 | 13.96 |

| 16 | 150 | 800 | 100.87 | 7.93 | 14.29 |

| 17 | 160 | 800 | 105.87 | 7.56 | 15.74 |

| 18 | 170 | 800 | 104.46 | 7.66 | 15.32 |

| 19 | 180 | 800 | 105.35 | 7.59 | 15.59 |

| 20 | 190 | 800 | 104.9 | 7.63 | 15.45 |

| 21 | 200 | 800 | 105.66 | 7.57 | 15.68 |

| 22 | 210 | 800 | 105.75 | 7.56 | 15.71 |

| 23 | 220 | 800 | 106.57 | 7.51 | 15.95 |

| 24 | 230 | 800 | 106.92 | 7.48 | 16.05 |

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| GPR | Ground Penetrating Raadar |

| CMP | Common Mid Point |

| RDP | Relative Pemittivity Dielectric |

| EM | Electromagnetic |

| Tx | Transmitter |

| Rx | Receiver |

| SNR | Signal to Noise Ratio |

| BSEF | Back Scattering Electromagnetic Field |

References

- Paoletti V.; D’Antonio D.; De Natale G.; Troise C.; Nappi R. Large-Depth Ground-Penetrating Radar for Investigating Active Faults: The Case of the 2017 Casamicciola Fault System, Ischia Island (Italy). Applied Sciences 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nappi R.; Paoletti V.; D’Antonio D.; Soldovieri F.; Capozzoli L.; Ludeno G.; Porfido S.; Michetti A. M. Joint Interpretation of Geophysical Results and Geological Observations for Detecting Buried Active Faults: The Case of the “Il Lago” Plain (Pettoranello Del Molise, Italy). Remote Sensing 2021, p. 8. [CrossRef]

- Alani A. M.; Morteza A.; Gokhan K. Applications of Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) in Bridge Deck Monitoring and Assessment. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2013, pp. 45–54.

- Soldovieri F.; Persico F.; Utsi E.; Utsi V. The Application of Inverse Scattering Techniques with Ground Penetrating Radar to the Problem of Rebar Location in Concrete. NDT & E International 2006, pp. 602–607.

- D’Antonio D.; Di Stefano S.; Faustoferri A.; De Leo A. Opi (AQ) Ponte Romano Sul Sangro. Quaderni di Archeologia d’Abruzzo 2014, 5, 128–134.

- Lai W. L.; Kou S. C.; Tsang W. F. Characterization of Concrete Properties from Dielectric Properties Using Ground Penetrating Radar. Cement and Concrete Research 2009, pp. 687–695.

- Tosti F.; Slob E. Determination, by Using GPR of the Volumetric Water Content in Structures, Substructures, Foundations and Soil, Civil Engineering Applications of Ground Penetrating Radar. Springer Transaction in Civil and Environmental Engineering 2015.

- Zhou D.; Zhu H. Application of Ground Penetrating Radar in Detecting Deeply Embedded Reinforcing Bars in Pile Foundation. Hindawi Advances in Civil Engineering 2021, p. 13.

- Bradford J. H. Frequency Dependent Attenuation of GPR Data as a Tool for Material Property Characterization: A Review and New Developments. Proceedings of 6th International Workshop on Advanced GPR 2011, pp. 1–4.

- Grandjean G.; Gourry J. C.; Bitri A. Evaluation of GPR Technique for Civil-Engineering Applications: Study on a Test Site. Applied Geophysics 2000, pp. 141–156. [CrossRef]

- Annan A. P. Ground Penetrating Radar Principles, Procedures and Applications, s. & s. ed.; Vol. 278, Sensors & Software Inc.: New York, 2003.

- Davis J. L.; Annan A. P. Ground Penetrating Radar for High-Resolution Mapping of Soil and Rock Stratigraphy. Geophysics 1989, pp. 531–551.

- Annan A. P.; Cosway S. W. Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems. Ground Penetrating Radar Survey Design 1992.

- Daniels D. J. Ground Penetration Radar, 2nd ed.; Number 15 in IEE Radar, Sonar and Navigation, Institut of Engineering Technology: London, 2004.

- Burger H.R. Exploration Geophysics of the Shallow Subsurface, englewood cliffs ed.; Print Hall: New Jersey, 1992.

- Conyers L. B. Ground-Penetrating Radar for Archaeology; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, 2004.

- Lavoue F. 2D Full Waveform Inversion of Ground Penetrating Radar Data: Towards Multiparameter Imaging from Surface Data. Sigillum Universitatis Gratianopolitane 2014.

- Klysz G.; Balayssac J. P. Determination of Volumetric Water Content of Concrete Using Ground-Penetrating Radar. Cement and Concrete Research 2007. [CrossRef]

- Moysey S.; Knight R. J. Modeling the field-scale relationship between dielectric constant and water content in heterogeneous systems. Water Resources Research 2004, p. 40.

- Jonscher A. K. Modeling the field-scale relationship between dielectric constant and water content in heterogeneous systems. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 1999, pp. 57–70.

- Olhoeft, G. R. Maximizing the Information Return from Ground Penetrating Radar. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2000, pp. 175–187. [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos A. GprMax2D V 1.5 User’s Manual, 2002.

- Persico R. Introduction to Ground Penetrating Radar: Inverse Scattering and Data Processing; Wiley-IEEE Press, 2014.

- Radzevicius S.; Daniels J. J. Ground Penetrating Radar Polarization and Scattering from Cylinders. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2000, pp. 111–125. [CrossRef]

- Langley K. A.; Hamrain S. E. Use of C-band Ground Penetrating Radar to Determine Backscatter Sources within Glaciers. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2005.

- Denisov R. R. Processing of georadary data in automatic mode. Scientific and Technical Journal Geophysics 2010, pp. 76–80.

- Ulaby F. T.; Moore R. K.; Fung A. K. Microwave Remote Sensing Active And Passive Volume Ii Radar Remote Sensing And Surface Scattering And Emission Theory; Vol. II, Radar Remote Sensing And Surface Scattering And Emission Theory, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1982.

- Toropainen A.P. Measurement of the Properties of Granular Materials by Microwave Backscattering. Journal of Microwave Power and Electromagnetic Energy 1995, pp. 240–245. [CrossRef]

- González R. C.; Woods E. C.; Eddins S. L. Digital Image Processing Using MATLAB; Pearson Prentice Hall, 2003.

- Ivan Levyant V. B.; Petrov Pankratov S. A. Seismic Exploration Technologies. Research of the characteristics of longitudinal and exchange waves of retroactive response scattering from the zones of the cracked collector 2009, pp. 3–11.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).