1. Introduction

Throughout life, from birth to the old age, the exposure to a number of harmful factors such as toxins, environmental pollutants, pathogens causes the onset of chronic diseases with impact on quality of life [

1]. It has been observed that oxidative stress is the main cause of the onset and progression of these diseases. Oxidative stress occurs as a result of an imbalance between the production of different reactive oxygen species and the body's antioxidant capacity to neutralize them [

2]. Efforts have been made to discover new drugs to prevent the harmful effects of reactive oxygen species in order to prevent or slow the progression of these diseases [

3]. Attention has recently focused on the effectiveness of lactoferin, a milk-derived protein, in limiting the harmful effects of oxidative stress.

Lactoferin is a multifunctional glycoprotein, of the transferrin family, with a molecular weight of approximately 80kDa and comprises a single polypeptide chain of 700 amino acids [

4]. In structure, it has two alpha-helix-connected lobes, known as N-terminal and C-terminal. Each lobe is capable of binding a metal ion, such as Cu

+2, Zn

+2, Mn

+3 and Fe

+3 [

5]. Lactoferin is produced mainly in milk and colostrum and secreted in all body fluids. Its concentration in milk depends on the phase of lactation. Colostrum has been shown to have a seven times higher concentration of lactoferin than mature milk [

6]. Lactoferin exhibits numerous biological functions, such as iron chelator, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and antioxidant agent, and also has a major role in host-defence mechanisms [

7,

8,

9]. After oral or intravenous administration, lactoferin is highly regulated through binding sites on the brain, endothelial cells allowing passage from the blood into tissues, including the brain [

10,

11,

12]. As an iron-binding protein, lactoferin regulates the absorption of dietary iron, which is an important metal in the growth and development of the body, including the brain [

13]. Due to its iron-binding capacity, lactoferin can exist as apo (iron-free) state or holo state when saturated with iron. This is important, because apo-lactoferin can bind iron, thus preventing the growth of bacteria, while holo-lactoferin corrects iron deficiency [

14,

15]. Lactoferin is also synthesized in activated microglia and thus represents a defense mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases [

16]. Lactoferin has also been shown to decrease inflammation. Lactoferin is protective for dopaminergic neurons by combating mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, two mechanisms underlying Parkinson's disease, periventricular leukomalacia and developmental brain injury [

17,

18]. Thus, lactoferin has beneficial effects both in brain development and after perinatal brain injury [

19]. A recent study by Atayde et al. on preterm infants exposed to high versus low doses of lactoferin showed that infants exposed to high doses of lactoferin had larger total brain and cortical gray matter volume, suggesting the benefit of lactoferin for preterm infant brain development [

20].

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aim to present the most recent work on the neuroprotective role of lactoferin and also to shed some light on future prospects on its supporting effects during brain developmental injury or after perinatal brain injury in the pediatric population.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

21]. The review aimed to assess the neuroprotective role of lactoferin in children by analyzing current evidence and exploring future research directions.

2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed using the following electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The search was conducted up to March 2025 without language restrictions. The following keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were used: “lactoferin,” “neuroprotection,” “children,” “pediatric neurology,” “brain development,” and “cognitive function.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) were applied to refine the search.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were the following: (1) studies investigating the effects of lactoferin on neurological development and neuroprotection in children (aged 0-18 years); (2) studies assessing cognitive, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental outcomes; (3) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies, and systematic reviews; (4) studies based on animal model which proofed evidence on neurocognitive function.

Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) studies focusing solely on adults without pediatric relevance; (2) articles with insufficient data or lack of peer review; (3) reviews, editorials, or opinion pieces without original data.

The studies included in this review involved both human and animal subjects. For clarity and consistency, the data were grouped and analyzed according to the type of subjects enrolled: human studies and animal studies.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

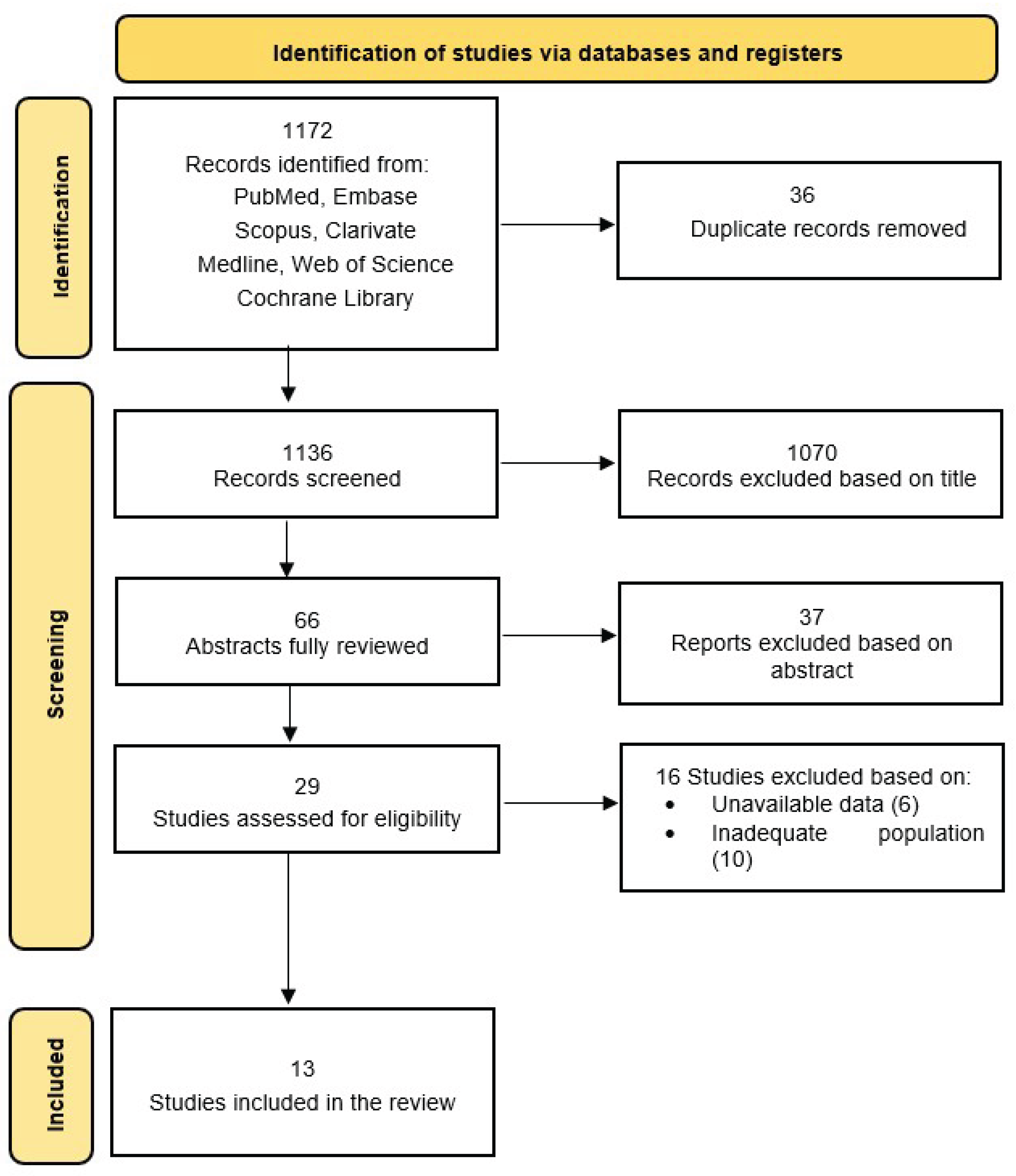

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved studies. Full-text articles were assessed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. A standardized data extraction form was used to collect the following information: study characteristics (author, year, study design, sample size); population demographics (age, health status); intervention details (lactoferin dosage, duration, administration route); outcome measures (cognitive function, neurodevelopmental parameters); key findings and conclusions (

Figure 1,

Table 1,

Table 2).

2.5. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomised control trials and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was applied to assess the strength of evidence.

2.6. Data Synthesis

A qualitative synthesis of the findings was conducted, summarizing the neuroprotective effects of lactoferin in pediatric populations or on animal model. If sufficient data were available, a meta-analysis was planned, with effect sizes calculated for primary neurodevelopmental outcomes.

For the synthesis and presentation of results, the effect measures varied depending on the outcome type. Cognitive function was the only outcome assessed in multiple RCTs using comparable standardized measures (e.g., Bayley-III, intelligence and executive function tests). The effect size was calculated using the Standardized Mean Difference (SMD). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic, and results were presented in a forest plot. Other outcomes (e.g., brain volume, neurodevelopmental scores, sleep quality, neuroprotection) were reported in single studies, so meta-analytic pooling was not feasible. In these cases, findings were presented as mean differences, qualitative summaries, or narrative synthesis of reported values, depending on the type of data and availability. Subgroup comparisons (e.g., age-based) were also expressed using SMD, and sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding one study at a time to assess the robustness of the findings.

To prepare the data for presentation and synthesis, missing summary statistics were addressed by replacing missing values with group means when appropriate.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

As this study was a systematic review of published literature, ethical approval was not required. All data sources were publicly available and properly cited.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Process

A total of 1,172 records were initially identified through the literature search. After duplicate removal and preliminary screening of titles and abstracts, 29 studies were selected for full-text assessment. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 13 studies were ultimately included in the final analysis. The study selection process is illustrated in the flow diagram presented in

Figure 1.

3.2. Summary of Included Studies

A total of 13 (5+8) studies met the inclusion criteria, including both human and animal studies assessing the neuroprotective role of lactoferin. The studies varied in design, population, and intervention details, but consistently suggested a positive impact of lactoferin on brain development, cognitive function, and neuroprotection.

3.3. Key Findings and Interpretation

Human studies indicated that lactoferin supplementation improved cognitive function, brain volume and development, neurodevelopmental scores and long-term neuroprotection, particularly in infants and young children. Some studies also reported better sleep quality and executive function improvements.

Animal studies provided mechanistic insights, demonstrating that lactoferin enhances neuroprotection, mitigates hypoxic-ischemic damage, and reduces oxidative stress-induced lesions. Various dosing strategies, including maternal dietary supplementation and direct injections, showed promising neuroprotective effects in preclinical models.

Findings collectively suggest lactoferin as a promising neuroprotective molecule, with potential clinical applications in neonatal care and pediatric neurology.

3.4. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The methodological quality of the selected studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies. Additionally, the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was used to assess the overall strength of evidence.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) evaluated five key domains, as it can be seen in the table below.

Table 3.

Risk of bias summary for RCTs.

Table 3.

Risk of bias summary for RCTs.

| Study |

Randomization process |

Deviations from intended interventions |

Missing outcome data |

Measurement of outcomes |

Selection of reported results |

Overall risk of bias |

| Colombo, 2023 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

| Miyakawa, 2020 |

Low |

Low |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Some concerns |

| Li, 2019 |

Low |

Low |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Some concerns |

| Lactoprenew, 2013 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

- 2.

Risk of Bias in Observational Studies

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) evaluates observational studies based on three criteria: selection (0-4 points; a score of 4 means excellent selection methods with minimal bias), comparability (0-2 points, a score of 1 suggests it controlled for some, but not all, important confounders) and outcome (0-3 points, a score of 3 reflects strong outcome assessment and follow-up), as it can be seen in the table below.

Table 4.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Summary.

Table 4.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Summary.

| Study |

Selection (0-4) |

Comparability (0-2) |

Outcome (0-3) |

Total Score (0-9) |

Quality Rating |

| Atayde, 2024 |

4/4 |

1/2 |

3/3 |

8/9 |

High |

- 3.

Quality of animal studies

For animal studies, risk of bias was evaluated using an adapted version of the SYRCLE's Risk of Bias tool, as can be seen in the table below. Most animal studies had moderate risk of bias, primarily due to lack of blinding (performance and detection bias).

Table 5.

Risk of Bias in Animal Studies.

Table 5.

Risk of Bias in Animal Studies.

| Study |

Selection Bias |

Performance Bias |

Detection Bias |

Attrition Bias |

Reporting Bias |

Overall Risk of Bias |

| Carvalho, 2025 |

Low |

Some concerns |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

| Sanches, 2023 |

Low |

Some concerns |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

| Sokolov, 2022 |

Low |

Low |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

| Sanches, 2021 |

Low |

Some concerns |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

| Zhao, 2020 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

| van de Looij, 2019 |

Low |

Low |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

| Ginet, 2016 |

Low |

Some concerns |

Some concerns |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

| Huang, 2007 |

Some concerns |

Some concerns |

High |

Some concerns |

High |

High |

- 4.

Strength of evidence using GRADE framework

The GRADE approach was used in RCT to assess the overall certainty of evidence based on: Risk of bias, Inconsistency (heterogeneity across studies), Indirectness (applicability of studies to real-world scenarios), Imprecision (wide confidence intervals, small sample sizes), Publication bias (selective publication of positive results).

Table 6.

GRADE Summary.

| Outcome |

Study Type |

No. of Studies |

Certainty Rating |

Reason for Downgrading |

| Lf and Brain Development |

RCTs & Observational |

2 |

Moderate |

Some concerns about missing data |

| Lf and Cognitive Function |

RCTs |

2 |

Moderate |

Limited long-term follow-up |

| Lf and Sleep Quality |

RCT |

1 |

Low |

Single study, small sample |

Moderate-certainty evidence supports the neuroprotective role of lactoferin in brain development and cognitive function. Low-certainty evidence exists for lactoferin’s effect on sleep quality, due to a single small study.

Regarding the subgroup analysis, an dose-based analysis was conducted. Some studies used low dose of lactoferin < 1 g/L or mg/day, others a moderate dose and another one used a high dose of lactoferin > 1 g/L or mg/day. All the low dose studies showed positive outcomes, with improvements in brain development, sleep quality, and neurodevelopmental scores. The study that used high dose of lactoferin (Lactoprenew), which hasn't yet provided results, is crucial for understanding the potential neuroprotective benefits of higher doses of Lf.

3.5. Feasibility of Conducting a Meta-Analysis

Cognitive function was the only outcome assessed in more than one randomized controlled trial using comparable measures (e.g., Bayley-III, standardized intelligence and executive function tests). However, only two studies met the criteria for inclusion in a meta-analysis. All other outcomes—such as brain volume, sleep quality, and neuroprotection—were reported in single studies, precluding quantitative synthesis. Available data for cognitive function was extracted from included studies as can be seen in the

Table 7 below.

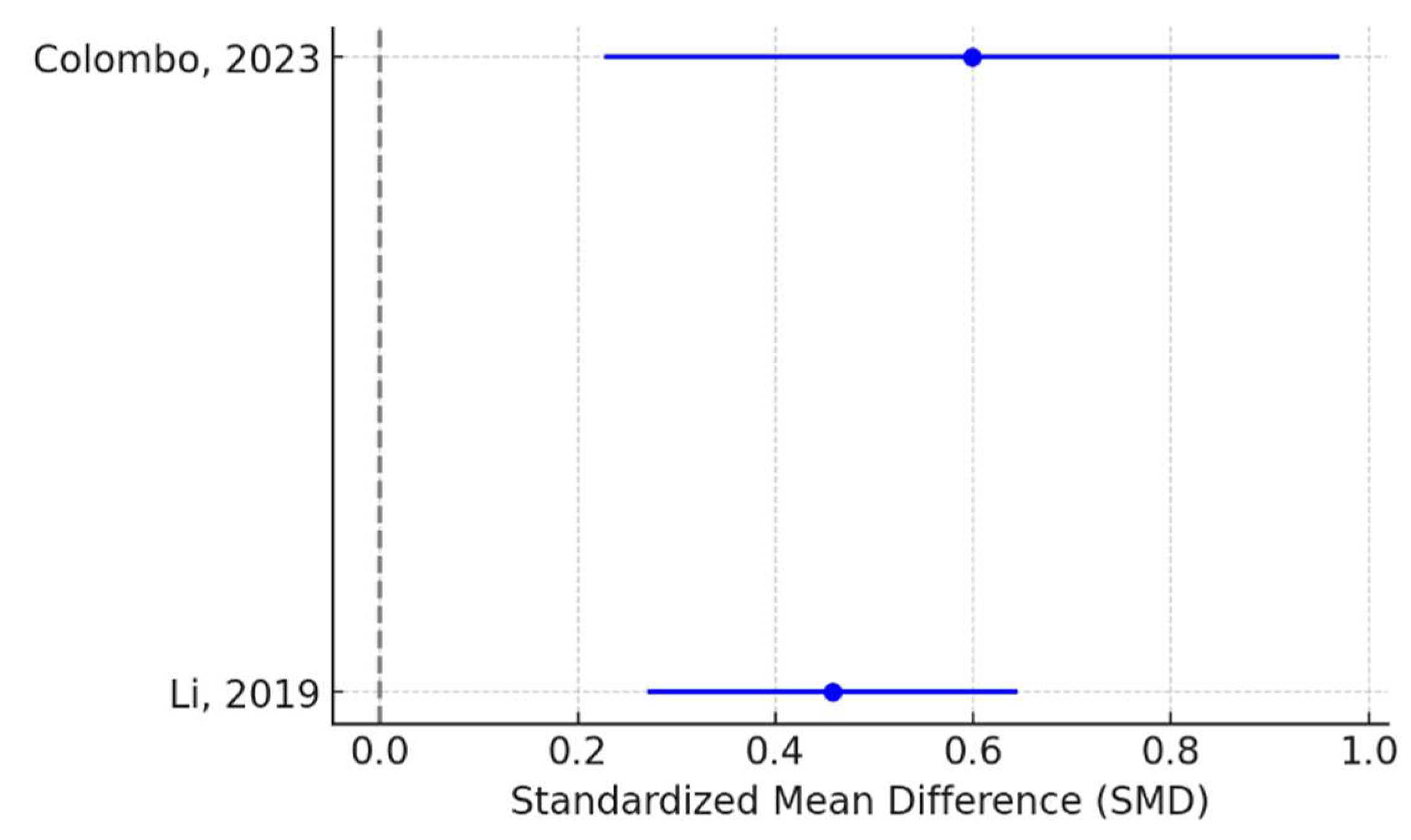

This data allowed us to calculate the Standardized Mean Difference (SMD). We also computed heterogeneity (I² statistic) and created a forest plot on effect of lactoferin on cognitive function (

Figure 2).

The meta-analysis suggests that lactoferin supplementation improves cognitive function in children, with moderate effect sizes and low heterogeneity. The fixed-effects model is appropriate due to the low I² value.

Regarding subgroup analysis, an age-based analysis was conducted: for infants (Li, 2019) a SMD of 0.46 was obtained and for older children (Colombo, 2023) a SMD of 0.60 was calculated. Heterogenity (I²) was 0%. So, we concluded that from Lf supplementation benefits both infants and older children, with a slightly stronger effect in older children. The sensitivity analysis showed that by removing Colombo 2023, SMD was 0.46 and by removing Li 2019, SMD was 0.6. Since the results remain stable, no single study overly influences the overall conclusion.

4. Discusions

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we consider the neuroprotective role of lactoferin in children. Both clinical and preclinical studies have provided evidence for the neuroprotective effect of lactoferin.

Lactoferin is an iron-binding, sialic-acid-rich milk protein with multifunctional health benefits including neural development, cognition and memory and supports brain development during periods of rapid growth [

35]. Infants are born with all formed neurons, postnatal neurogenesis being limited. As far as synaptogenesis and the formation and development of myelin sheaths around nerve fibers is concerned, most of it takes place in the postnatal period [

36]. The first two years of a child's life are a critical period. This is when the brain reaches 80% of its adult weight. The accelerated development of the brain in the neonatal and postnatal period makes it vulnerable to nutritional deficiencies, even though it shows a high degree of plasticity during this period [

36,

37]. Molecules such as iron, zinc, omega-3 fatty acids, cholines, vitamin B12, vitamin D, syalilated glycoconjugates are important not only for morphological growth, but also for neurochemical and neuropsychological processes [

38]. The brain is a heterogeneous organ comprising completely distinct anatomical regions (such as the hippocampus and cortex), different processes (myelination, production of neurotransmitters and neurotrophic factors), and metabolic requirements that vary according to the region and the time of development [

38,

39].

Several studies have been conducted to demonstrate the effect of lactoferin on cognitive outcomes. A double-blind randomized controlled nutrition trial by Li at al showed an accelerated neurodevelopmental profile at 12 months and effects on language development at 18 months in healthy term infants who received an added bovine milk fat globule membrane and bovine lactoferin infant formula at concentrations similar to human milk [

25]. Subsequently, Colombo et al demonstrated in a follow up study from the original study, cohort improved cognitive outcome in multiple domains at 5.5 years, including intelligence and executive function [

23]. Another benefit of lactoferin demonstrated by Miyakawa et al in a study of healthy children aged 12 to 32 months was improved sleep quality, especially morning symptoms like waking up with difficulty and getting out of bed with difficulty [

24].

Regarding the neuroprotective action of lactoferin on the central nervous system, preclinical studies have shown that lactoferin administered by lactation to the developing brain rat models of perinatal hypoxia-ischaemia and inflammation, those with intrauterine growth restriction and and those exposed to prenatal corticoids has anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic effects [

19]. This evidence presented in preclinical studies is the target for translation into future clinical trials. Due to the fact that the effects of lactoferin administration on brain development are relatively new, the effective dose range is not yet known, therefore future studies are needed.

A study by van de Looij et al demonstrated the long-term neuroprotective effects of lactoferin after hypoxic-ischemic injury in 3-day old rat [

32]. By using advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) analysis they showed that the percentage of injured cortex after hypoxia-ischemia on day 3 and the percentage of cortical loss on day 25 was significantly reduced in the group receiving lactoferin, thus indicating both acute and long-term protective effects. Also, after day 25, it was observed that the cortical metabolism was almost normalized and the alteration of the white matter produced by the hypoxic-ischemic injury presented recovery in the group of those who were given lactoferin with normalization of the white matter water diffusion parameters [

32]. These results can be further used in neonatology clinical trials on brain neuroprotection. Another study conducted by Sanches et al demonstrated that lactoferin supplementation has neuroprotective effects on the immature brain in a dose-dependent manner by reducing inflammation, apoptosis, oxidative stress and glutaminergic excitotoxicity, attenuating the effects of hypoxia-ischemia. Administration of bovine lactoferin at doses of 0.1, 1 and 10 mg/kg body weight has neuroprotective effects both in the acute (24 hours) and long-term (22 days) phases after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic insult in the rat pups brain [

28].

A study conducted by Ginet et al showed the neuroprotective effect of maternal lactoferin nutritional supplementation during lactation on inflammatory injury in the immature brain [

33]. To mimic infection/inflammation causing developmental injury, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was injected into the subcortical white matter of rat pups at postnatal day 3 (P3). The effect of maternal lactoferin supplementation was evaluated at 24 hours (P4), 4 days (P7) or 21 days (P24) after LPS injection mainly in the striatum. A reduction of LPS-induced ventriculomegaly, brain tissue loss and microstructural changes were observed with reduced microglia response and restoration of brain metabolic status [

33]. These results show the beneficial role of lactoferin in reducing brain injury and developmental impairment in relation to preterm birth after hypoxia/ischemia.

Sokolov et al showed the protective effects of apo-form of human lactoferin injected to female rats during gestation or lactation on cognitive functions (short-term memory, long-term memory and working memory) in the offspring rats exposed to hypoxia during gestation [

29]. These results may help to develop new therapeutic strategies to reduce cognitive deficits caused by hypoxia-ischemia during pregnancy or labor. Studies have shown the neuroprotective role of lactoferin administered during gestation and lactation in rat and ovine models of glucocorticoid exposure during gestation that causes intrauterine growth restriction, brain growth restriction, hypomyelination and a delay in brain tissue differentiation [

40,

41,

42].

The study faced several limitations: only two RCTs were suitable for meta-analysis, reducing the strength of conclusions. Some studies lacked complete data, with missing values replaced by means, which may affect accuracy. Study heterogeneity in design, population, comparator and outcomes limited broader synthesis. Potential publication bias and limited long-term follow-up also weaken generalizability. Additionally, translating findings from animal to human studies remains a challenge.

The evidence included in the review also has several limitations: most studies had small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, and moderate to low methodological quality. Some relied on single-center data or lacked control groups. Variability in lactoferrin dosage and outcome measures also limits comparability. Overall, the certainty of evidence ranged from moderate to low.

The findings suggest that practice in pediatric care could benefit from lactoferrin supplementation to support brain development and cognitive outcomes, especially in at-risk infants, though dosing guidelines are still needed. These results may inform policy by supporting the integration of lactoferrin into infant nutrition programs aimed at neurodevelopmental support, pending further evidence. For future research, more robust, long-term randomized controlled trials are essential to confirm efficacy, determine optimal dosage, and explore broader clinical applications.