Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

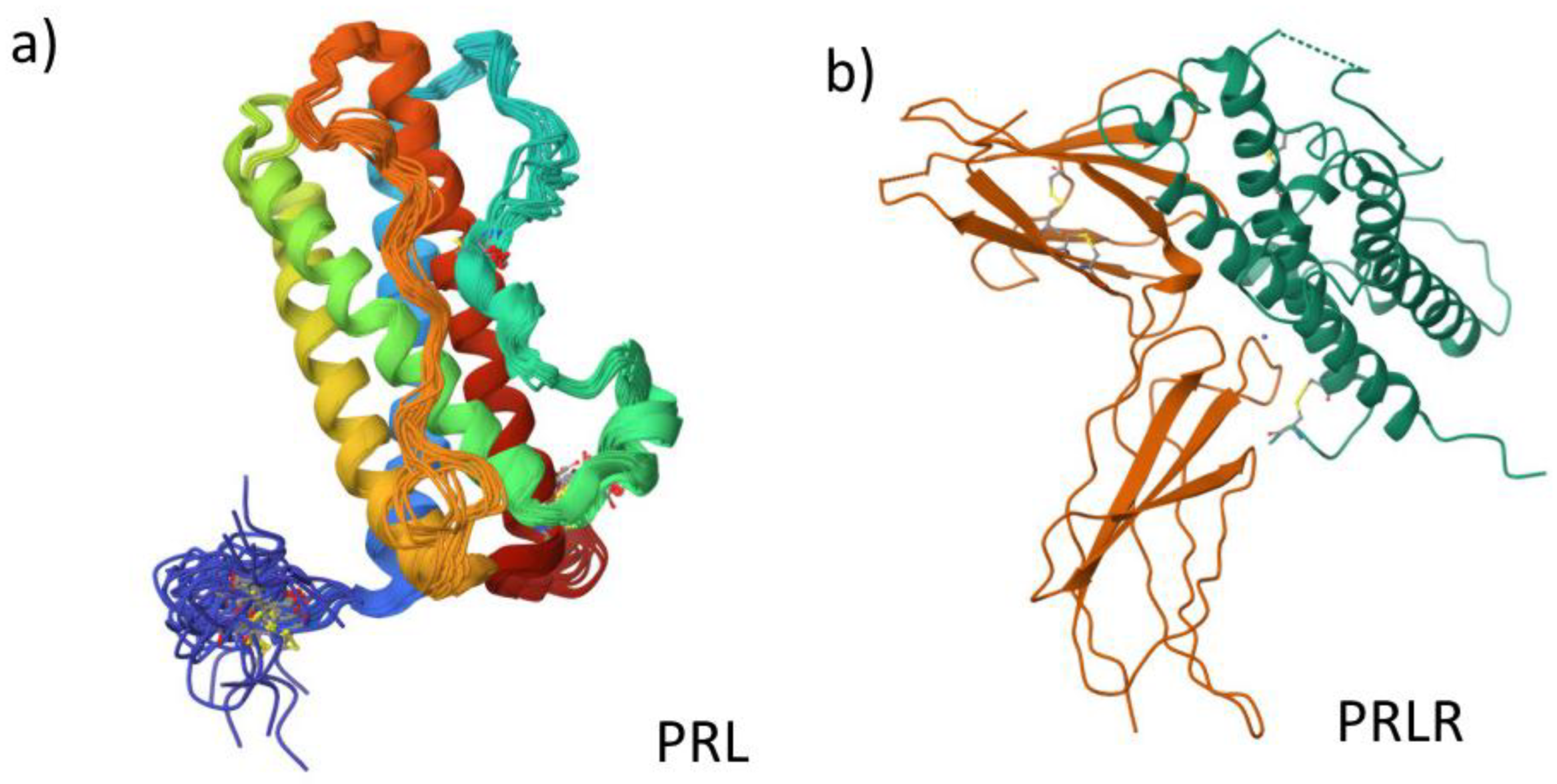

2. The Hormone Prolactin

3. Prolactin Receptors

4. Prolactin Functions

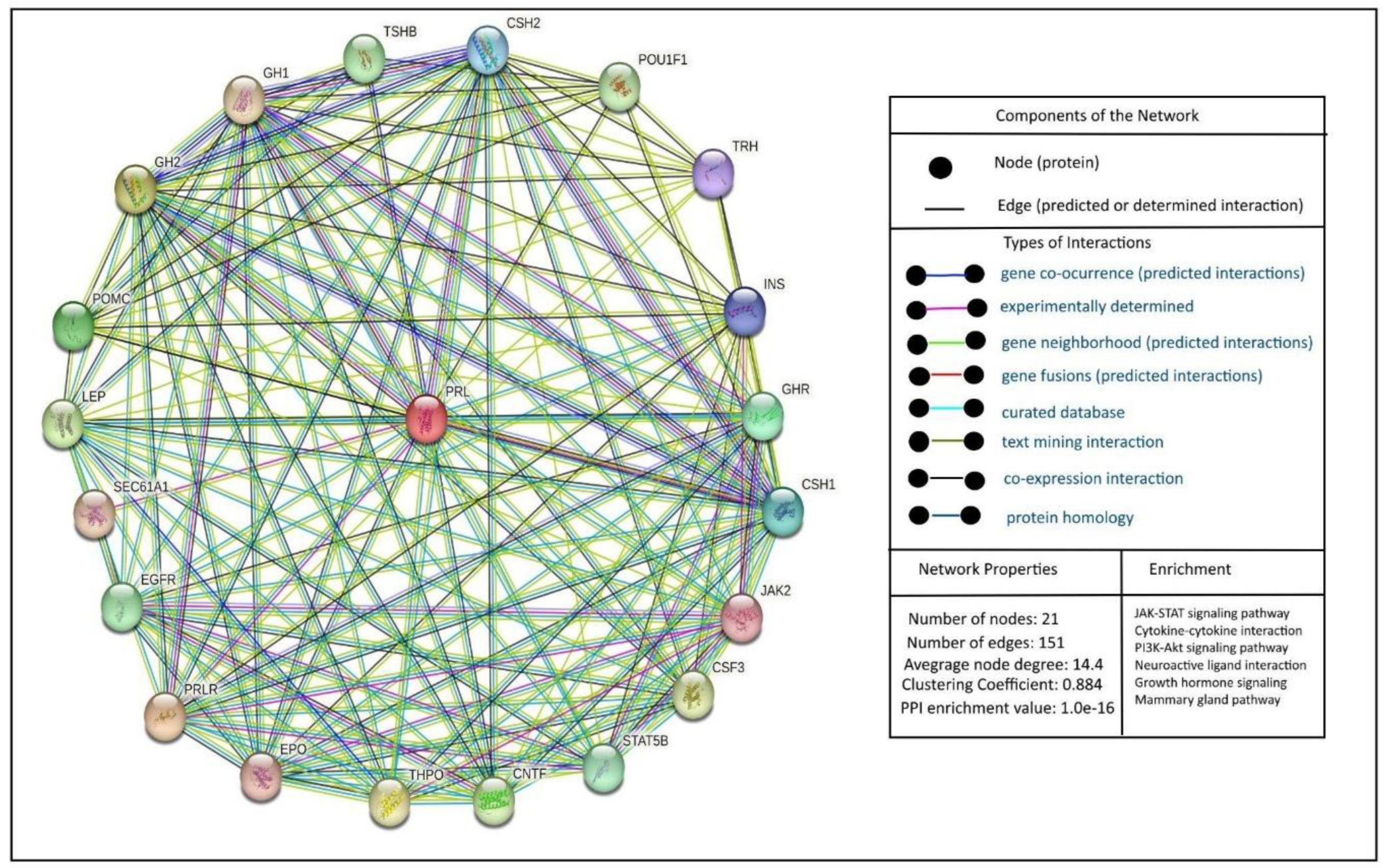

5. Prolactin and Interactions

6. Prolactin and the Immune System

7. Prolactin and Autoimmune Diseases

8. Prolactin in Asthma

9. Prolactin and Aging

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRL | Prolactin |

| GINA | Global Initiative for Asthma |

| HPA | hypophysis-pituitary-adrenal |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematosus |

| RA | rheumatoid arthritis |

| MS | multiple sclerosis |

| PRLR | Prolactin receptor |

| PMCA | Plasma membrane Ca²⁺-ATPase |

| NCX | Na⁺/Ca²⁺ exchanger |

| ENaC | Epithelial sodium channel |

| ClC4 | Chloride channel |

| FIL | Leukaemia inhibiting factor |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| PRF | PRL-releasing factors |

| PIF | PRL inhibitory factors |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| DOPA | Dihydroxyphenylalanine |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| SDCs | CD1c-positive dendritic cells |

| OVA | ovalbumin |

| SLIT | sublingual immunotherapy |

| ECP | eosinophil cationic protein |

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| PMA | perimenstrual asthma |

| AHR | airway hyperresponsiveness |

References

- GINA. global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2024.

- Akcan, N.; Bahceciler, N.N. Headliner in Physiology and Management of Childhood Asthma: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2020, 16(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, V.J.; Menzies, J.R.; Douglas, A.J. Differential changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and prolactin responses to stress in early pregnant mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 23(11), 1066–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russjan, E. The Role of Peptides in Asthma–Obesity Phenotype. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(6), 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Kazmi, I.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Alshehri, S.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Imam, S.S.; Nadeem, M.S.; Al-Zahrani, M.H.; Alzarea, S.I.; Alquraini, A. Current Overview on Therapeutic Potential of Vitamin D in Inflammatory Lung Diseases. Biomedicines. 2021, 9(12), 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Díazcouder, A.; Romero-Nava, R.; Del-Río-Navarro, B.E.; Sánchez-Muñoz, F.; Guzmán-Martín, C.A.; Reyes-Noriega, N.; Rodríguez-Cortés, O.; Leija-Martínez, J.J.; Vélez-Reséndiz, J.M.; Villafaña, S.; et al. The Roles of MicroRNAs in Asthma and Emerging Insights into the Effects of Vitamin D3 Supplementation. Nutrients. 2024, 16(3), 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, V.; Martin, Y.N.; Prakash, Y.S. Sex steroid signaling: Implications for lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2015, 150, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Amaya, J.E.; Hamasato, E.K.; Tobaruela, C.N.; Queiroz-Hazarbassanov, N.; Anselmo Franci, J.A.; Palermo-Neto, J.; Greiffo, F.R.; de Britto, A.A.; Vieira, R.P.; Ligeiro de Oliveira, A.P.; et al. Short-term hyperprolactinemia decreases allergic inflammatory response of the lungs. Life Sci. 2015, 142, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insuela, D.B.R.; Daleprane, J.B.; Coelho, L.P.; Silva, A.R.; e Silva, P.M.; Martins, M.A.; Carvalho, V.F. Glucagon induces airway smooth muscle relaxation by nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2. J Endocrinol. 2015, 225(3), 205–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochicoa-Rangel, L.; Chávez, J.; Del-Río-Hidalgo, R.; Guerrero-Zúñiga, S.; Mora-Romero, U.; Benítez-Pérez, R.; Rodríguez-Moreno, L.; Torre-Bouscoulet, L.; Vargas, M.H. Lung function is related to salivary cytokines and hormones in healthy children. An exploratory cross-sectional study. Physiol Rep 2023, 11(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkhi, A.A.; Shepard, K.V.; Casale, T.B.; Cardet, J.C. Elevated Testosterone Is Associated with Decreased Likelihood of Current Asthma Regardless of Sex. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020, 8(9), 3029–35.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzikowska, U.; Golebski, K. Sex hormones and asthma: The role of estrogen in asthma development and severity. Allergy 2023, 78(3), 620–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, E.A.; Miller, V.M.; Prakash, Y.S. Sex Differences and Sex Steroids in Lung Health and Disease. Endocr Rev. 2012, 33(1), 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, B.S.; Flores-Soto, E.; Sommer, B.; Reyes-García, J.; Arredondo-Zamarripa, D.; Solís-Chagoyán, H.; Lemini, C.; Rivero-Segura, N.A.; Santiago-de-la-Cruz, J.A.; Pérez-Plascencia, C. 17β-estradiol induces hyperresponsiveness in guinea pig airway smooth muscle by inhibiting the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2024, 590, 112273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, W.; Murphy, V. Asthma in pregnancy: a review. Obstet Med. 2013, 6(2), 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, V.V.; Zandman-Goddard, G.; Shoenfeld, Y. Prolactin and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorshkind, K.; Horseman, N.D. The roles of prolactin, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I, and thyroid hormones in lymphocyte development and function: insights from genetic models of hormone and hormone receptor deficiency. Endocr Rev. 2000, 21(3), 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, V.V.; Zandman-Goddard, G.; Shoenfeld, Y. Prolactin and autoimmunity: The hormone as an inflammatory cytokine. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 33(6), 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, M.; Binart, N.; Steinman, L.; Pedotti, R. Prolactin: a versatile regulator of inflammation and autoimmune pathology. Autoimmun Rev. 2015, 14(3), 223–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.E.; Jacobson, J.D. Roles of prolactin and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000, 26(4), 713–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.E. Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus with bromocriptine. Lupus. 2001, 10(3), 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc Nguyen, H.; Hoang, N.M.H.; Ko, M.; Seo, D.; Kim, S.; Jo, W.H.; Bae, J.W.; Kim, M.S. Association between Serum Prolactin Levels and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2022, 29(2), 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Jabir, M.S.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadily, A.K. The conceivable role of prolactin hormone in Parkinson disease: The same goal but with different ways. Ageing Res Rev. 2023, 91, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippoliti, F.; De Santis, W.; Volterrani, A.; Lenti, L.; Canitano, N.; Lucarelli, S.; Frediani, T. Immunomodulation during sublingual therapy in allergic children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003, 14(3), 216–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbacho, A.M.; Valacchi, G.; Kubala, L.; Olano-Martín, E.; Schock, B.C.; Kenny, T.P.; Cross, C.E. Tissue-specific gene expression of prolactin receptor in the acute-phase response induced by lipopolysaccharides. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 287(4), E750–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bole-Feysot, C.; Goffin, V.; Edery, M.; Binart, N.; Kelly, P.A. Prolactin (PRL) and its receptor: actions, signal transduction pathways and phenotypes observed in PRL receptor knockout mice. Endocr Rev. 1998, 19(3), 225–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeeta Devi, Y.; Halperin, J. Reproductive actions of prolactin mediated through short and long receptor isoforms. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014, 382(1), 400–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorvin, C.M. The prolactin receptor: Diverse and emerging roles in pathophysiology. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015, 2(3), 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Salinas, G.; Rivero-Segura, N.A.; Cabrera-Reyes, E.A.; Rodríguez-Chávez, V.; Langley, E.; Cerbon, M. Decoding signaling pathways involved in prolactin-induced neuroprotection: A review. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 61, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Brito, A.R.; Gonçalves, I.; Santos, C.R.A. The brain as a source and a target of prolactin in mammals. Neural Regen Res. 2022, 17(8), 1695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horseman, N.D.; Gregerson, K.A. Prolactin actions. J Mol Endocrinol. 2014, 52(1), R95–R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, R.J.; Ben-Jonathan, N. Minireview: Extrapituitary Prolactin: An Update on the Distribution, Regulation, and Functions. Mol Endocrinol. 2014, 28(5), 622–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.J.; Henry, M.A.; Akopian, A.N. Prolactin receptor in regulation of neuronal excitability and channels. Channels. 2014, 8(3), 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Salinas, G.; Rodríguez-Chávez, V.; Langley, E.; Cerbon, M. Prolactin-induced neuroprotection against excitotoxicity is mediated via PI3K/AKT and GSK3 β /NF- κB in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons. Peptides. 2023, 166, 171037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorkkam, N.; Wongdee, K.; Suntornsaratoon, P.; Krishnamra, N.; Charoenphandhu, N. Prolactin stimulates the L-type calcium channel-mediated transepithelial calcium transport in the duodenum of male rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013, 430(2), 711–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Qu, Z.W.; Ren, C.; Gan, X.; Qiu, C.Y.; Hu, W.P. Prolactin potentiates the activity of acid-sensing ion channels in female rat primary sensory neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2016, 103, 174–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlee, M.M.; Mitzelfelt, J.D.; Duke, B.J.; Al-Khalili, O.; Bao, H.F.; Eaton, D.C. Prolactin stimulates sodium and chloride ion channels in A6 renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015, 308(7), F697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Reyes, E.A.; Limón-Morales, O.; Rivero-Segura, N.A.; Camacho-Arroyo, I.; Cerbón, M. Prolactin function and putative expression in the brain. Endocrine. 2017, 57(2), 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, V.; Young, J.; Binart, N. Prolactin-a pleiotropic factor in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019, 15(6), 356–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.W.; Lahr, E.L.; Riddle, O. The gross action of prolactin and follicle-stimulating hormone on the mature ovary and sex accessories of fowl. Am J Physiol Content. 1935, 111, 361–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.E.; Kanyicska, B.; Lerant, A.; Nagy, G. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000, 80(4), 1523–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattan, D.R.; Kokay, I.C. Prolactin: A Pleiotropic Neuroendocrine Hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 20(6), 752–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, R.S.; Grattan, D.R. 30 years after: CNS actions of prolactin: Sources, mechanisms and physiological significance. J Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 31(3), e12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huising, M.O.; Kruiswijk, C.P.; Flik, G. Phylogeny and evolution of class-I helical cytokines. J Endocrinol. 2006, 189(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, P.; Dinan, T.G. Prolactin and dopamine: what is the connection? A review article. J Psychopharmacol. 2008, 22, 12–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binart, N. Prolactin and pregnancy in mice and humans. Ann Endocrinol. 2016, 77(2), 126–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, N.; Binart, N. Prolactin and adipose tissue. Biochimie. 2014, 97, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, M.; Pedotti, R. Prolactin: Friend or Foe in Central Nervous System Autoimmune Inflammation? Int J Mol Sci. 2016, 17(12), 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guh, Y.J.; Lin, C.H.; Hwang, P.P. Osmoregulation in zebrafish: ion transport mechanisms and functional regulation. EXCLI J. 2015, 14, 627–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, J.; Sánchez-Robledo, V.; Carretero-Hernández, M.; Catalano-Iniesta, L.; García-Barrado, M.J.; Iglesias-Osma, M.C.; Blanco, E.J. Prolactin system in the hippocampus. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 375(1), 193–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebel, J.; Robles, J.P.; Zamora, M.; Clapp, C.; Bertsch, T. New horizons in specific hormone proteolysis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022, 33(6), 371–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, N.; Adachi, T.; Ishihara, T.; Shimatsu, A. The natural history of macroprolactinaemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012, 166(4), 625–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, V.; Villa, C.; Auguste, A.; Lamothe, S.; Guillou, A.; Martin, A.; Caburet, S.; Young, J.; Veitia, R.A.; Binart, N. Natural and molecular history of prolactinoma: insights from a Prlr-/– mouse model. Oncotarget. 2018, 9(5), 6144–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, V.; Young, J.; Chanson, P.; Binart, N. New insights in prolactin: pathological implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015, 11(5), 265–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, C.; Aranda, J.; González, C.; Jeziorski, M.C.; Martínez de la Escalera, G. Vasoinhibins: endogenous regulators of angiogenesis and vascular function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 17(8), 301–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macotela, Y.; Ruiz-Herrera, X.; Vázquez-Carrillo, D.I.; Ramírez-Hernandez, G.; Martínez De La Escalera, G.; Clapp, C. The beneficial metabolic actions of prolactin. Front Endocrinol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Castañeda, E.; Grattan, D.R.; Pasantes-Morales, H.; Pérez-Domínguez, M.; Cabrera-Reyes, E.A.; Morales, T.; Cerbón, M. Prolactin mediates neuroprotection against excitotoxicity in primary cell cultures of hippocampal neurons via its receptor. Brain Res. 2016, 1636, 193–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, G.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Extra-pituitary prolactin (PRL) and prolactin-like protein (PRL-L) in chickens and zebrafish. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2015, 220, 143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torner, L. Actions of Prolactin in the Brain: From Physiological Adaptations to Stress and Neurogenesis to Psychopathology. Front Endocrinol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, V.S.; Harris, R.M.; Austin, S.H.; Nava Ultreras, B.; Booth, A.M.; Angelier, F.; Lang, A.S.; Feustel, T.; Lee, C.; Bond, A. Prolactin and prolactin receptor expression in the HPG axis and crop during parental care in both sexes of a biparental bird (Columba livia). Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2022, 315, 113940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.B.; Whittington, C.M.; Meyer, A.; Scobell, S.K.; Gauthier, M.E. Prolactin and the evolution of male pregnancy. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2023, 334, 114210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laud, K.; Gourdou, I.; Belair, L.; Peyrat, J.P.; Djiane, J. Characterization and modulation of a prolactin receptor mRNA isoform in normal and tumoral human breast tissues. Int J Cancer. 2000, 85(6), 771–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.M.; Ginsburg, E.; McAndrew, C.W.; Heger, C.D.; Cheston, L.; Rodriguez-Canales, J.; Vonderhaar, B.K.; Goldsmith, P. Characterization of Δ7/11, a functional prolactin-binding protein. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012, 50(2), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jonathan, N.; Mershon, J.L.; Allen, D.L.; Steinmetz, R.W. Extrapituitary prolactin: distribution, regulation, functions, and clinical aspects. Endocr Rev. 1996, 17(6), 639–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattan, D.R. 60 YEARS OF NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY: The hypothalamo-prolactin axis. J Endocrinol. 2015, 226(2), 101–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P.; Kokay, I.; Sapsford, T.; Bunn, S.; Grattan, D. Prolactin regulation of the HPA axis is not mediated by a direct action upon CRH neurons: evidence from the rat and mouse. Brain Struct Funct. 2017, 222(7), 3191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, P.; Martínez-Moreno, C.G.; Lorenson, M.Y.; Walker, A.M.; Morales, T. Prolactin Attenuates Neuroinflammation in LPS-Activated SIM-A9 Microglial Cells by Inhibiting NF-κB Pathways Via ERK1/2. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2022, 42(7), 2171–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Campos, A.; Giovannini, P.; Parati, E.; Novelli, A.; Caraceni, T.; Müller, E.E. Growth hormone and prolactin stimulation by Madopar in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981, 44(12), 1116–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Reyes, E.A.; Vanoye–Carlo, A.; Rodríguez-Dorantes, M.; Vázquez-Martínez, E.R.; Rivero-Segura, N.A.; Collazo-Navarrete, O.; Cerbón, M. Transcriptomic analysis reveals new hippocampal gene networks induced by prolactin. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reem, G.H.; Ray, D.W.; Davis, J.R. The human prolactin gene upstream promoter is regulated in lymphoid cells by activators of T-cells and by cAMP. J Mol Endocrinol. 1999, 22(3), 285–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torner, L.; Neumann, I.D. The Brain Prolactin System: Involvement in Stress Response Adaptations in Lactation. Stress. 2002, 5(4), 249–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.L.; Vukovic, J.; Koudijs, M.M.; Blackmore, D.G.; Mackay, E.W.; Sykes, A.M.; Overall, R.W.; Hamlin, A.S.; Bartlett, P.F. Prolactin Stimulates Precursor Cells in the Adult Mouse Hippocampus. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7(9), e44371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero-Segura, N.A.; Flores-Soto, E.; García De La Cadena, S.; Coronado-Mares, I.; Gomez-Verjan, J.C.; Ferreira, D.G.; Cabrera-Reyes, E.A.; Lopes, L.V.; Massieu, L.; Cerbón, M. Prolactin-induced neuroprotection against glutamate excitotoxicity is mediated by the reduction of [Ca2+]i overload and NF-κB activation. PLOS ONE. 2017, 12(5), e0176910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Moratalla, A.; Martín, E.D. Prolactin enhances hippocampal synaptic plasticity in female mice of reproductive age. Hippocampus. 2021, 31(3), 281–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chávez, V.; Flores-Soto, E.; Molina-Salinas, G.; Martínez-Razo, L.D.; Montaño, L.M.; Cerbón, M. Prolactin reduces the kainic acid-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, leading to neuroprotection of hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2023, 810, 137344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya, J.M.; Shoenfeld, Y. Multiple autoimmune disease in a patient with hyperprolactinemia. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005, 7(11), 740–1. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira Borba, V.; Sharif, K.; Shoenfeld, Y. Breastfeeding and autoimmunity: Programing health from the beginning. Am J Reprod Immunol 2018, 79(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Gonzalez, J.; Rosenfeld, G.; Keiser, H.; Peeva, E. Prolactin alters the mechanisms of B cell tolerance induction. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60(6), 1743–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.M.; Garman, R.D.; Keyes, L.; Kavanagh, B.; McPherson, J.M. Prolactin is an antagonist of TGF-beta activity and promotes proliferation of murine B cell hybridomas. Cell Immunol. 1998, 184(2), 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeva, E.; Zouali, M. Spotlight on the role of hormonal factors in the emergence of autoreactive B-lymphocytes. Immunol Lett. 2005, 101(2), 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athreya, B.H.; Pletcher, J.; Zulian, F.; Weiner, D.B.; Williams, W.V. Subset-specific effects of sex hormones and pituitary gonadotropins on human lymphocyte proliferation in vitro. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993, 66(3), 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, L.; Galetto, A.; Geuna, M.; Vekemans, K.; Ricotti, E.; Contarini, M.; Moro, F.; Basso, G. Individual and combined effect of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor and prolactin on maturation of dendritic cells from blood monocytes under serum-free conditions. Immunology. 2000, 100(1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, L.; Mori, M.; Galetto, A. Effect of prolactin on the antigen presenting function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Lupus. 2001, 10(10), 728–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, R.W. Estrogen, prolactin, and autoimmunity: actions and interactions. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001, 1(6), 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Lastra, O.; Jara, L.J.; Espinoza, L.R. Prolactin and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. Autoimmun Rev. 2002, 1(6), 360–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Lee, L.Y. Prolactin modulation of immune and inflammatory responses. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002, 57, 435–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Hou, Y. Prolactin modulates the functions of murine spleen CD11c-positive dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006, 6(9), 1478–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jara, L.J.; Benitez, G.; Medina, G. Prolactin, dendritic cells, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2008, 7(3), 251–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikanza, I.C. Prolactin and neuroimmunomodulation: in vitro and in vivo observations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999, 876, 119–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, P.E.; Cronin, M.J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma reduce prolactin release in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1990, 259(5), E672–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, K.; Masumoto, N.; Kasahara, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Tasaka, K.; Hirota, K.; Miyake, A.; Tanizawa, O. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha stimulates prolactin release from anterior pituitary cells: a possible involvement of intracellular calcium mobilization. Endocrinology. 1991, 128(6), 2785–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theas, S.; Pisera, D.; Duvilanski, B.; De Laurentiis, A.; Pampillo, M.; Lasaga, M.; Seilicovich, A. Estrogens modulate the inhibitory effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on anterior pituitary cell proliferation and prolactin release. Endocrine. 2000, 12(3), 249–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, R.; Nguyen, T. Protein S: function, regulation, and clinical perspectives. Curr Opin Hematol. 2021, 28(5), 339–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, L.; Mori, M. Cooperation of Pituitary Hormone Prolactin with Interleukin-2 and Interleukin-12 on Production of Interferon-γ by Natural Killer and T Cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000, 917(1), 505–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A;. Singh, S.M.; Sodhi, A. Effect of prolactin on nitric oxide and interleukin-1 production of murine peritoneal macrophages: role of Ca2+ and protein kinase C. Int J Immunopharmacol 1997, 19(3), 129–33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.H.; Kessler, M.A.; Schuler, L.A. Regulation of interleukin (IL)-1alpha, IL-1beta, and IL-6 expression by growth hormone and prolactin in bovine thymic stromal cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1997, 128(1-2), 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.G.; Lee, Y.H. Circulating prolactin level in systemic lupus erythematosus and its correlation with disease activity: a meta-analysis. Lupus. 2017, 26(12), 1260–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praprotnik, S.; Agmon-Levin, N.; Porat-Katz, B.S.; Blank, M.; Meroni, P.L.; Cervera, R.; Miesbach, W.; Stojanovich, L.; Szyper-Kravitz, M.; Rozman, B.; et al. Prolactin's role in the pathogenesis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2010, 19(13), 1515–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.E.; Allen, S.H.; Hoffman, R.W.; McMurray, R.W. Prolactin: a stimulator of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1995, 4(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaños-Miranda, A.; Cárdenas-Mondragón, G. Serum free prolactin concentrations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus are associated with lupus activity. Rheumatology. 2006, 45(1), 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, R.; Keisler, D.; Kanuckel, K.; Izui, S.; Walker, S.E. Prolactin influences autoimmune disease activity in the female B/W mouse. J Immunol. 1991, 147(11), 3780–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, R.W.; Weidensaul, D.; Allen, S.H.; Walker, S.E. Efficacy of bromocriptine in an open label therapeutic trial for systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1995, 22(11), 2084–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa-Amaya, J.E.; Marino, L.P.; Tobaruela, C.N.; Namazu, L.B.; Calefi, A.S.; Margatho, R.; Gonçalves, V., Jr.; Queiroz-Hazarbassanov, N.; Klein, M.O.; Palermo-Neto, J.; et al. Attenuated allergic inflammatory response in the lungs during lactation. Life Sci. 2016, 151, 281–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semik-Orzech, A.; Skoczyński, S.; Pierzchała, W. Serum estradiol concentration, estradiol-toprogesterone ratio and sputum IL-5 and IL-8 concentrations are increased in luteal phase of the menstrual cycle in perimenstrual asthma patients. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017, 49(04), 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lai, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhou, G. Protective Effects of Herba Houttuyniae Aqueous Extract against OVA-Induced Airway Hyperresponsiveness and Inflammation in Asthmatic Mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, E.; Thébault, S.; Aroña, R.; Martínez de la Escalera, G.; Clapp, C. Prolactin mitigates deficiencies of retinal function associated with aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2020, 85, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, Y.Y.; Toledo, J.B.; Nefedov, A.; Polikar, R.; Raghavan, N.; Xie, S.X.; Farnum, M.; Schultz, T.; Baek, Y.; Deerlin, V.V.; et al. Identifying amyloid pathology–related cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease in a multicohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015, 1(3), 339–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zverova, M.; Kitzlerova, E.; Fisar, Z.; Jirak, R.; Hroudova, J.; Benakova, H.; Lelkova, P.; Martasek, P.; Raboch, J. Interplay between the APOE Genotype and Possible Plasma Biomarkers in Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2018, 15(10), 938–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, A.S.; Landau, S.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Serum prolactin levels in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Clin Auton Res. 2002, 12(5), 393–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitkowska, M.; Tomasiuk, R.; Czyżyk, M.; Friedman, A. Prolactin and sex hormones levels in males with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015, 131(6), 411–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiloiro, S.; Giampietro, A.; Bianchi, A.; De Marinis, L. Prolactinoma and Bone. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2018, 3, 21–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.J.; Sang, H.; Park, S.Y.; Chin, S.O. Effect of Hyperprolactinemia on Bone Metabolism: Focusing on Osteopenia/Osteoporosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(3), 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).