1. Introduction

Sampling-based search methods for large language models (LLMs) involve generating multiple responses, either in parallel, sequentially, or through hybrid approaches, and aggregating them into a final answer. Techniques such as Chain-of-Thought (CoT ) [

34], Tree-of-Thoughts (ToT) [

39], and ReAct [

40] have demonstrated that structured reasoning through intermediate steps can significantly enhance LLM performance. These approaches can be further extended with search algorithms, including Monte Carlo Tree Search (e.g., LATS, STaR) [

42,

43], bandit-based methods (e.g., LongPO) [

7], and gradient-based optimization (e.g., OPRO) [

38].

A crucial component in these search and optimization strategies is uncertainty estimation, which is vital for guiding decisions, balancing exploration and exploitation. Uncertainty estimation techniques, such as those used in Bandit algorithms or Bayesian optimization, can dynamically adjust learning rates or hyperparameters. In combinatorial optimization (e.g., genetic algorithms), uncertainty estimation informs heuristic decisions like mutation rates or temperature adjustments. Thus, developing robust methods for quantifying uncertainty in LLMs is essential for enabling more effective search behavior.

Prior work on LLM uncertainty estimation has primarily focused on methods based on generation likelihoods [

1,

12,

18], verbalized confidence [

11,

15], and response consistency [

9,

37]. These methods have shown utility for tasks like hallucination detection and risk assessment. However, we argue that these metrics primarily serve a

descriptive role: they reflect the model’s confidence in a given query but are not designed to guide or influence the generation process. For example, a model uncertainty score of 0.8 indicates a 20% estimated error rate when sampling multiple responses to a query, but it does not help determine which of those candidate responses is correct or should be preferred.

In contrast, search-based tasks demand a more prescriptive role from uncertainty estimators: rather than passively measuring confidence, they must actively guide decision-making during search. For instance, in multi-step generation or tree-based reasoning, uncertainty scores should inform which candidate answers to select, which nodes to expand, and which paths to prune or refine. An effective prescriptive estimator should provide fine-grained, local feedback that incrementally reduces error. Without this capability, even a well-calibrated estimator can lead to misleading decisions during search.

In this study, we evaluate whether existing LLM uncertainty metrics can fulfill a prescriptive role in search-based tasks by introducing two diagnostic tasks: (1) Answer Selection—choosing the best answer from a set of candidates; and (2) Answer Refinement—identifying which response most needs refinement. Our empirical results show that while current uncertainty metrics are useful for flagging risky or error-prone responses, they struggle to reliably guide search toward correctness. This highlights the need for optimization-aware uncertainty metrics explicitly designed to support decision-making in correctness-driven search.

2. Diagnostic Tests

Search-based methods for LLMs typically involve generating multiple candidate responses—either in parallel, sequentially, or both—and then aggregating them into a final answer. Within this process, two fundamental actions frequently occur:

selection and

refinement.

Selection refers to choosing which candidate responses to explore, exploit, or use in final aggregation—usually in a parallel setting.

Refinement, often used in sequential settings, involves generating follow-up outputs based on earlier responses, such as self-reflection [

20], verification [

35], or correction [

19]. Based on these two fundamental actions, we design two diagnostic tests to evaluate whether existing uncertainty metrics can meaningfully guide the search process. These tests aim to answer the question:

Can uncertainty metrics be reliably linked to correctness in a way that makes them useful for decision-making?

Test 1: Answer Selection

This test examines whether an uncertainty metric can help select the best answer among candidates. For each question, the LLM generates multiple responses. Responses that yield the same answer (regardless of surface form) are grouped into answer clusters. The uncertainty metric ranks these answer groups, under the assumption that correct answers should appear less uncertain (i.e., the lowest uncertainty score group is selected as the final answer). We measure how well the metric prioritizes correctness using three evaluation criteria: Pairwise-Win-Rate (prefer correct answers over an incorrect ones), Top-1 Accuracy (whether the top-ranked candidate is correct), and Mean-Reciprocal-Rank (how high correct answers appear on average).

Test 2: Answer Refinement

This test examines whether uncertainty metrics can identify which answers are most in need of refinement. For each question, the LLM first generates a set of initial answers. Refinement is then applied only to the answer cluster exhibiting the highest uncertainty score. A high uncertainty metric value suggests that an answer is more likely to be incorrect and thus a better candidate for refinement. We evaluate each metric by measuring the overall accuracy gain achieved through this targeted refinement.

Insights and Applications

The two tests highlight distinct roles for uncertainty metrics in search-based tasks. Test 1 assesses how well a metric ranks candidate answers by correctness—useful for reranking and aggregation. Test 2 evaluates the ability to prioritize answers for refinement, which is crucial in compute-limited settings like interactive systems. Together, these tests reveal how uncertainty metrics can guide specific search actions and inform their use in real-world applications.

3. Experiments

In this section, we introduce the uncertainty metrics, datasets, models, and baseline methods used in our two diagnostic experiments. Additional implementation details and prompt templates are provided in

Appendix A and

Appendix C.

Benchmarked Metrics

We benchmark six task-agnostic uncertainty metrics that don’t require additional model training. Generation-liklihood based metrics estimate uncertainty from the predictive entropy of model’s output distribution:

Normalized Predictive Entropy (NPE),

Length-Normalized Predictive Entropy (LNPE) [

18], and

Semantic Entropy (SE) [

12]. Verbalized-based measures assess confidence by directly prompting the model to express its certainty:

Verbalized Confidence (VC) and

P(True) [

11]. Lexical-based metrics:

Lexical Similarity[

16], evaluate uncertainty based on the consistency of lexical overlap between multiple responses. Since

P(True), and

VC are originally formulated to express model confidence, we transform them into uncertainty measures by taking their complements:

PTrue-Comp (1-

P(True)), and

VC-Neg (negative of

VC).

Datasets and Models

We select four diverse datasets:

MATH (mathematical reasoning) [

6],

CommonsenseQA (commonsense reasoning) [

21],

TriviaQA (reading comprehension) [

10], and

TruthfulQA (truthfulness) [

14].

MATH and

TriviaQA feature open-ended (free-form) answers, while

CommonsenseQA and

TruthfulQA use multiple-choice formats. These datasets are evaluated using three open-source language models [

3,

8,

22] of similar sizes:

LLaMA-3-8B,

Gemma-2-9B, and

Mistral-7B-v0.3. This setup ensures diversity across task types and model architectures, enhancing the robustness of our evaluation.

Baselines

In

Answer Selection test, we compare

Uncertainty-Guided Selection with (1)

Random Selection, where a candidate is chosen uniformly at random, and (2)

Majority Voting, which selects the most frequent answer as a strong self-consistency baseline [

33]. In

Answer Refinement test, we test whether

Uncertainty-Guided Refinement outperforms (1) refining a random answer (

Random Refinement), (2) refining the majority answer (

Majority Refinement), and (3) refining all answers (

All Refinement). For both tests, random baselines are calculated by averaging the scores over 50 runs of sampling to estimate the expected performance when randomly selecting a choice.

4. Result and Analysis

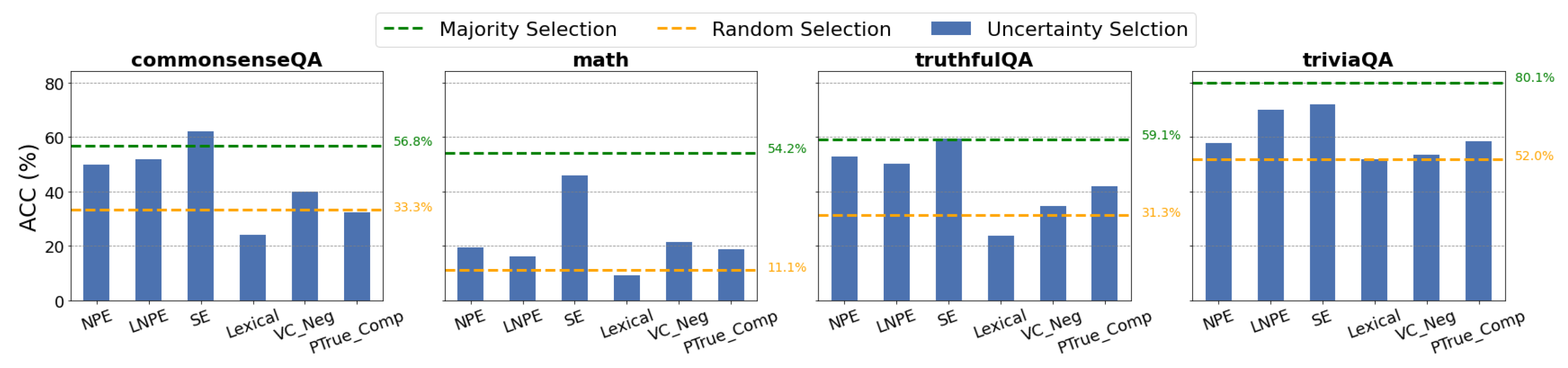

Uncertainty Metrics Fall Short in Answer Selection

As shown in

Figure 1,

Uncertainty-Guided Selection generally outperforms

Random Selection but underperforms compared to

Majority Voting. This indicates the limited applicability of uncertainty metrics in answer selection, as

Majority Voting, being computation-free, still outperforms uncertainty-guided methods.

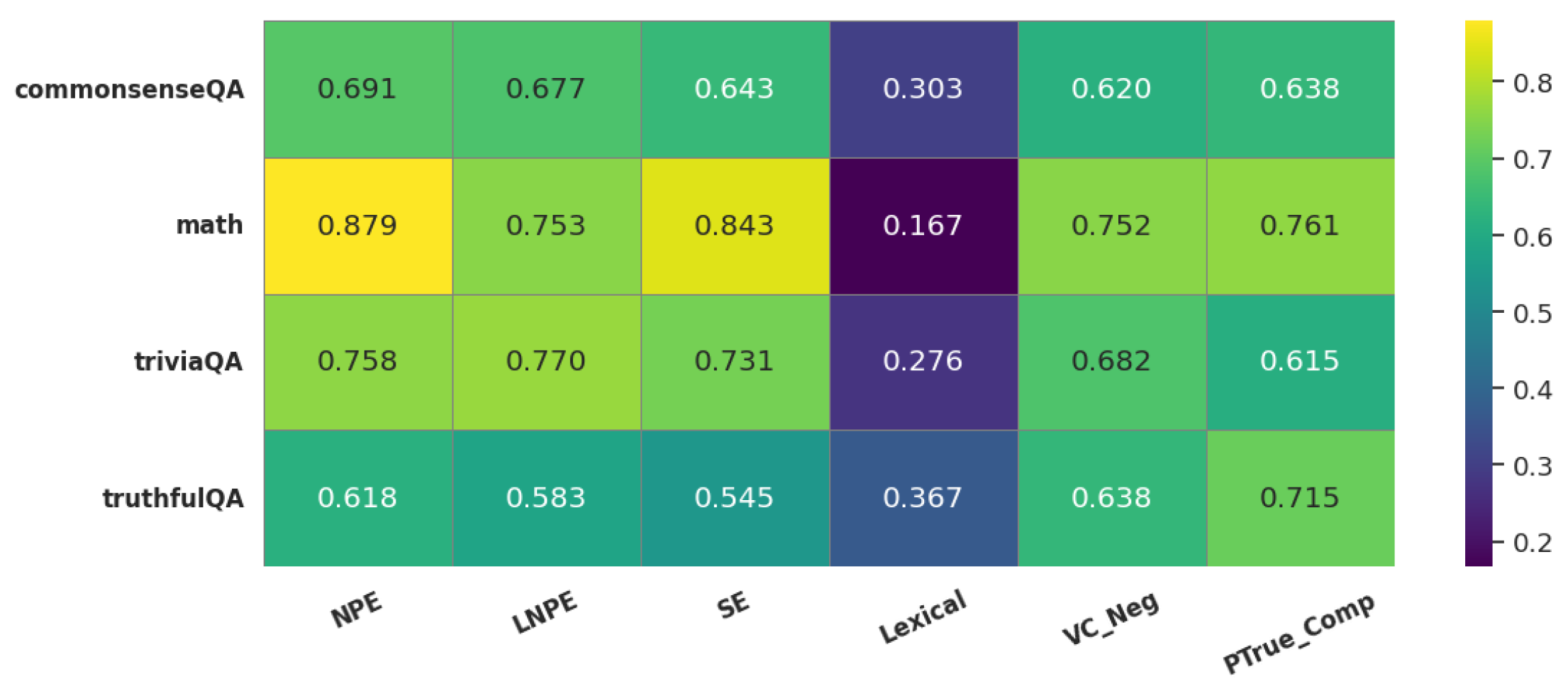

To dive deeper, we provide a breakdown of

Top-1 Accuracy (ACC),

Pairwise Win Rate (PWR), and

Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) for each uncertainty metric in

Table 1. Likelihood-based metrics (

NPE,

LNPE,

SE) typically achieve PWR and MRR above 0.6, indicating that they rank correct answers higher, though they don’t always place the correct answer at the top. In contrast, lexical- and verbalization-based metrics (

Lexical,

VC-Neg,

PTrue-Comp) perform poorly, with values often below 0.5. Notably, all metrics struggle with the

MATH dataset, likely due to its complex reasoning demands and open-ended answer format, which makes it difficult for existing metrics to provide reliable signals.

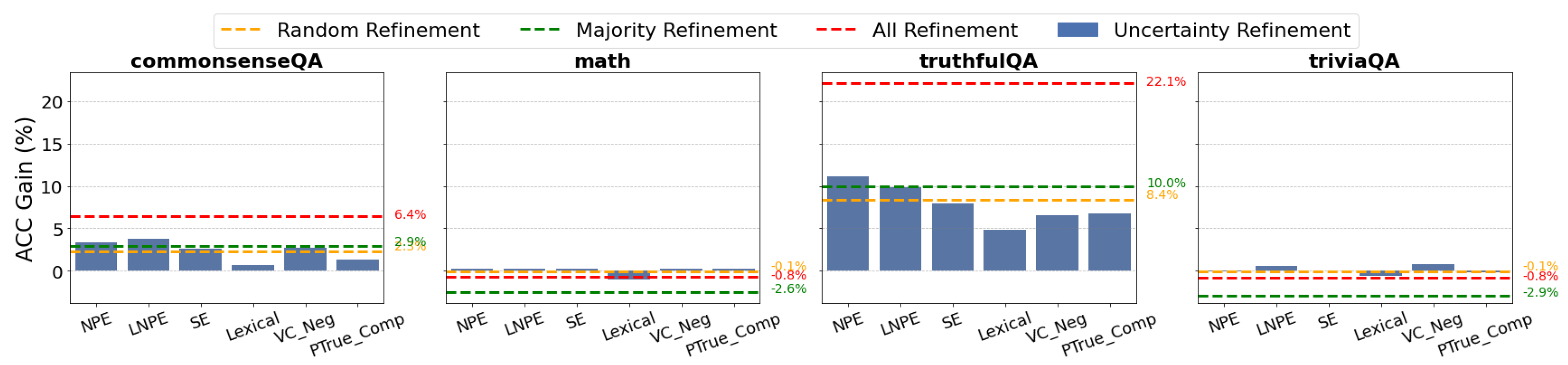

Uncertainty Metrics show potential to guide Answer Refinement.

As illustrated in

Figure 2,

Uncertainty-Guided Refinement leads to notable accuracy gains on

CommonsenseQA and

TruthfulQA, achieving performance close to

Majority Refinement but using fewer refinement attempts. On

MATH and

TriviaQA, where accuracy gains of

All Refinement are negative,

Uncertainty-Guided Refinement surprisingly shows a slightly positive values, likely due to refining fewer answers and reducing unnecessary corrections.

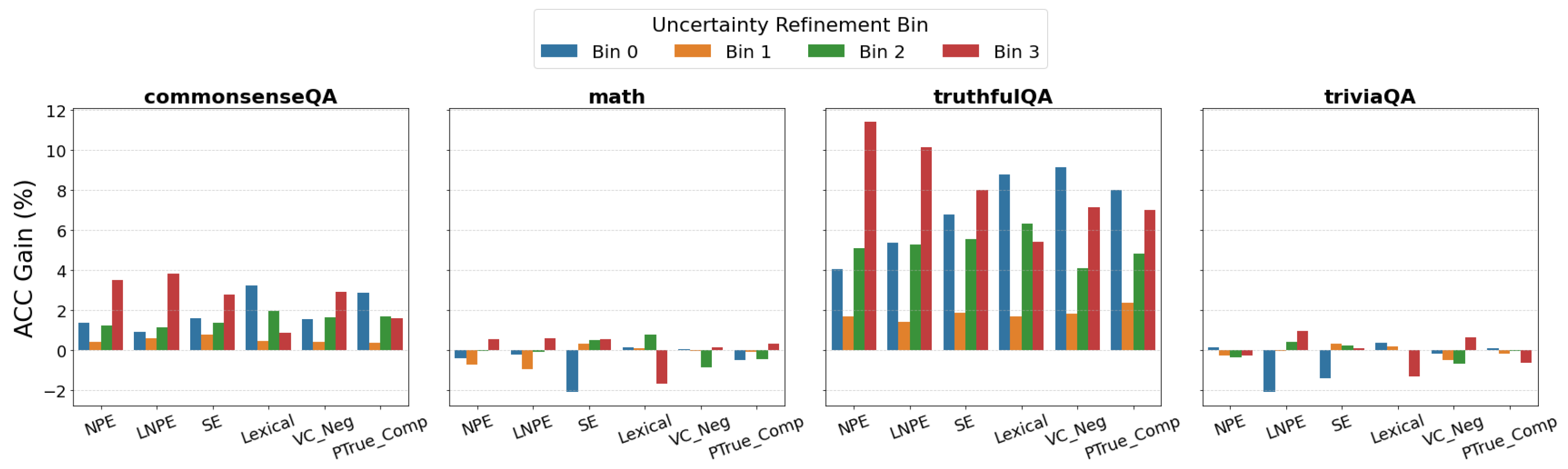

To analyze the refinement effect, we quantize answer candidates into four bins based on their uncertainty metric values and measure the accuracy gain achieved by refining answers in each bin. As shown in

Figure 3, refining answers in the higher-uncertainty bins generally leads to larger accuracy gains—consistent with the intuition that uncertain responses are more likely to be incorrect and therefore benefit from refinement. However, we also observe positive gains from refining answers in the lowest-uncertainty bin, suggesting potential mismatch between model confidence and correctness.

Descriptive vs. Prescriptive

From the previous analysis, we observe that current uncertainty metrics show potential in guiding answer refinement but struggle in answer selection. We argue this is because these metrics are designed for a

descriptive role—capturing the model’s confidence among outputs—rather than serving a

prescriptive role, where uncertainty directly informs decisions during search. Additional figures in

Appendix B highlight the descriptive power of these metrics.

The difference between descriptive and prescriptive roles helps explain why Uncertainty-Guided Refinement performs better than Uncertainty-Guided Selection. Refinement uses uncertainty metrics to identify low-confidence answers that are worth improving, which is a task that aligns with the descriptive strengths of the metrics. In contrast, selection assumes a mapping between confidence and correctness. This requires the model not only to recognize its uncertainty but also to correctly assess which answers are accurate.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we use two diagnostic tests to investigate the ability of LLM uncertainty metrics to guide search tasks. While these metrics are effective at identifying risky responses, they primarily capture model confidence and fall short in guiding toward correct answers. Our findings highlight the critical challenge of bridging the gap between model confidence and correctness, emphasizing the need for uncertainty metrics designed to support correctness-oriented decisions in search tasks.

Limitations

Due to computational constraints, we evaluate on a sampled subset of benchmark datasets. While bootstrapping is employed to reduce sampling bias, our findings may still be influenced by the limited scale. Additionally, our analysis focuses on a representative, but non-exhaustive, set of existing uncertainty metrics, meaning it may not capture all emerging approaches or domain-specific adaptations. Finally, our experiments are conducted using a fixed prompting and sampling strategy, so results may vary under different decoding settings or model configurations.

Use of AI Assistants

ChatGPT was utilized to refine paper writing. The authors paid careful attention to ensuring that AI generated content is accurate and aligned with the author’s intentions.

Appendix A. Implementation Details

Due to computational constraints, we randomly sample 150 questions from each dataset. To ensure robustness and statistical significance, we apply bootstrapping with 500 resamples across all experiments. For benchmarked metric calculation, we use: 32 samples for NPE, LNPE, and SE; 3 samples for VC-Neg and PTrue-Comp. For SE, we use jinaai/jina-embeddings-v3 as embedding model to cluster semantic group. All experiments are conducted using a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU. We use the vLLM engine for efficient inference and encoding text into vector.

Appendix B. Additional Results

To examine the descriptive power of uncertainty metrics, we assess their ability to predict hallucinations in model responses. We generate 32 responses per question, labeling those with accuracy below 70% as uncertain (positive class). This allows us to evaluate how well each estimator identifies low-confidence or error-prone questions driven by specific uncertainty factors.

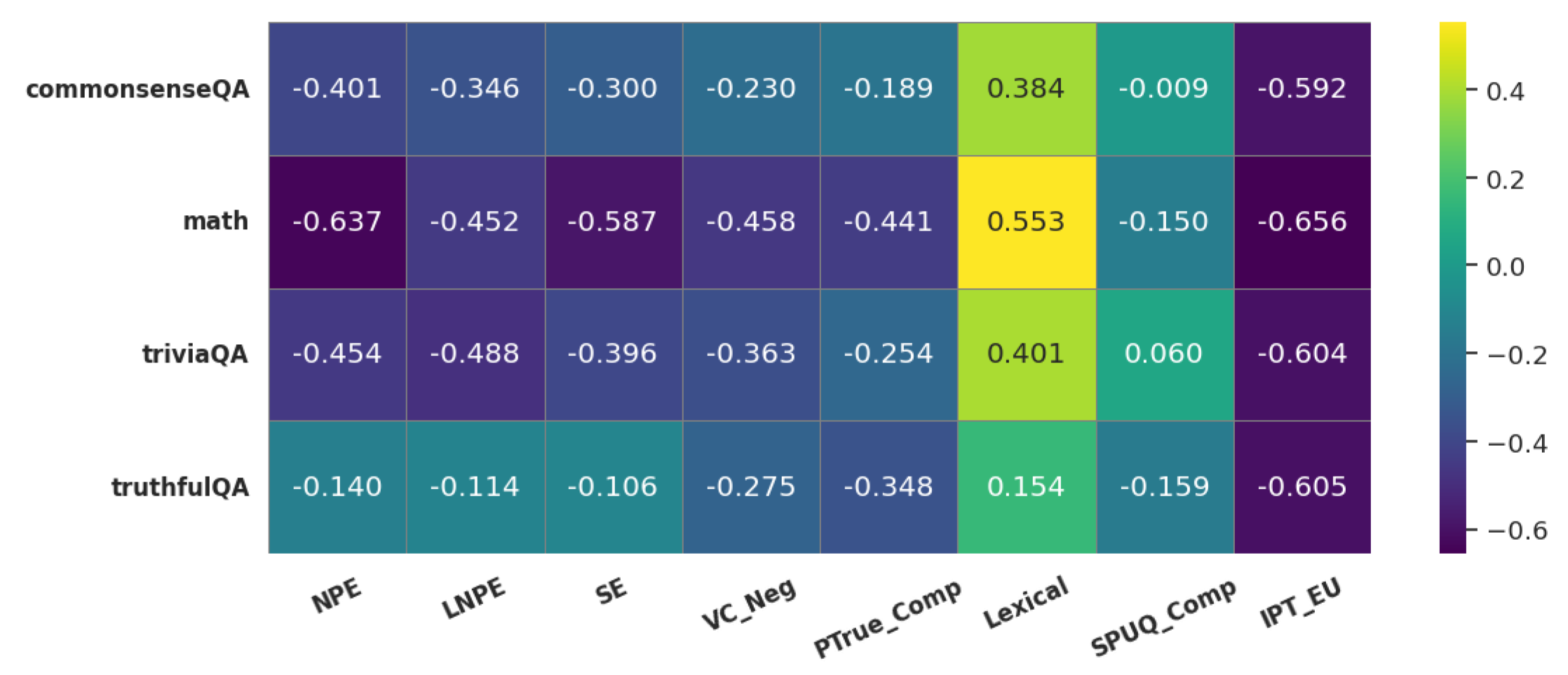

Figure A1 and

Figure A2 report the AUROC for identifying error-prone queries and the rank correlation between uncertainty metric values and response correctness. These figures highlight the strong descriptive power of the metrics in identifying when the model is uncertain.

Figure A1.

AUROC of uncertainty metrics across datasets. A higher value indicates that the uncertainty metric effectively distinguishes between error-prone and non-error-prone questions, capturing signals associated with potential hallucinations or inaccuracies.

Figure A1.

AUROC of uncertainty metrics across datasets. A higher value indicates that the uncertainty metric effectively distinguishes between error-prone and non-error-prone questions, capturing signals associated with potential hallucinations or inaccuracies.

Figure A2.

Rank correlation between uncertainty scores and response accuracy. Lower values (high uncertainty low correctness) indicate a stronger alignment between uncertainty estimates and actual correctness.

Figure A2.

Rank correlation between uncertainty scores and response accuracy. Lower values (high uncertainty low correctness) indicate a stronger alignment between uncertainty estimates and actual correctness.

Appendix C. Prompt Templates

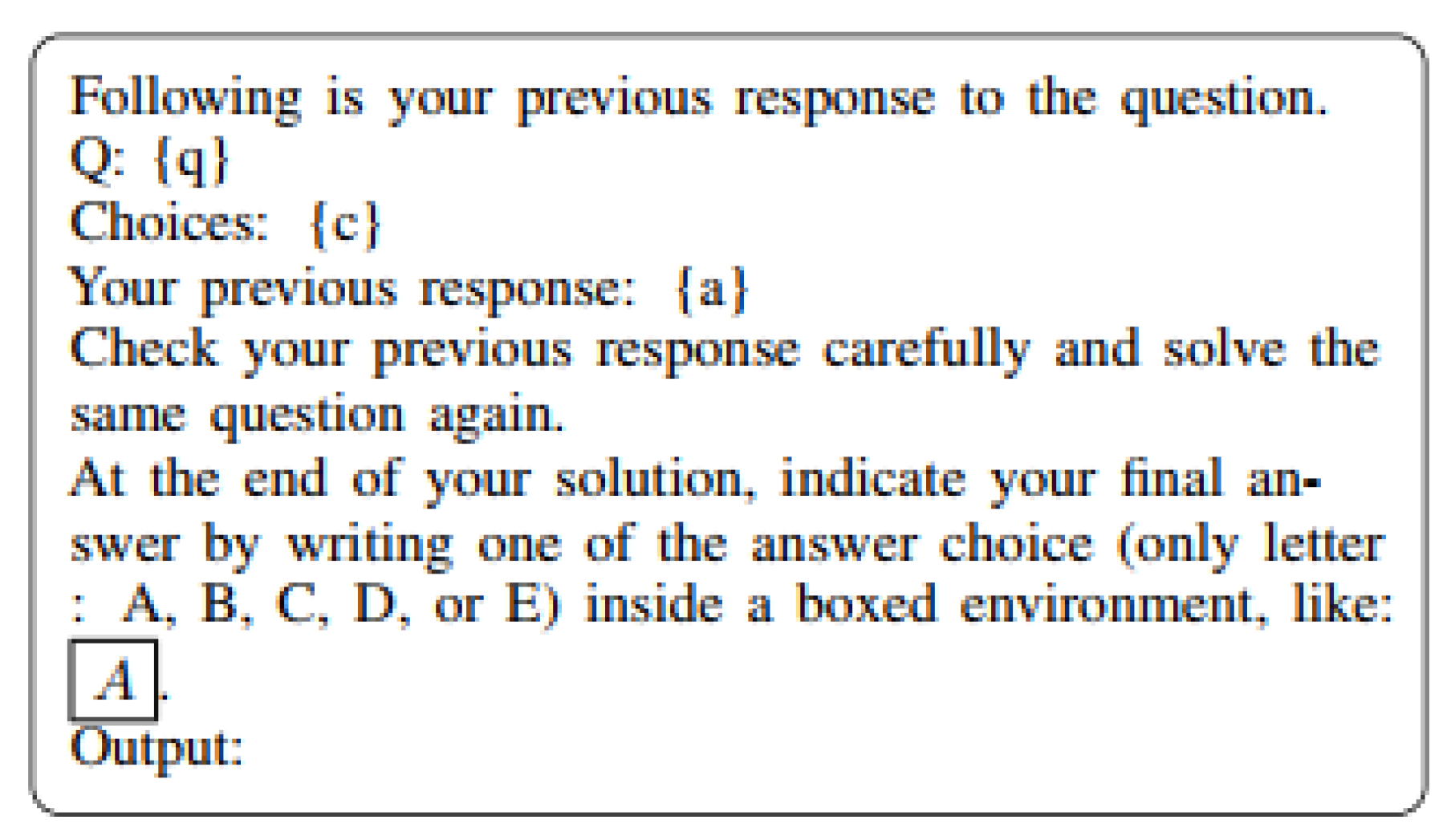

Figure A3.

Sampling Prompt Template for MC Questions

Figure A3.

Sampling Prompt Template for MC Questions

Figure A4.

Check Prompt Template for MC Questions

Figure A4.

Check Prompt Template for MC Questions

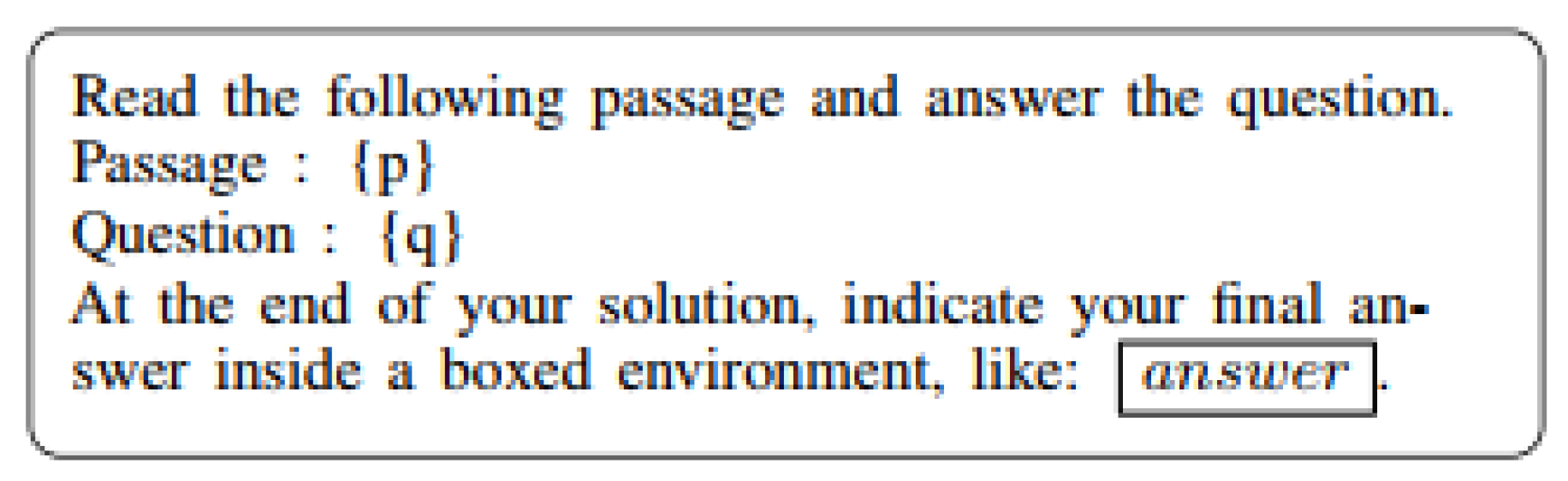

Figure A5.

Sampling Prompt Template for RC Questions

Figure A5.

Sampling Prompt Template for RC Questions

Figure A6.

Check Prompt Template for RC Questions

Figure A6.

Check Prompt Template for RC Questions

Figure A7.

Sampling Prompt Template for Essay Questions

Figure A7.

Sampling Prompt Template for Essay Questions

Figure A8.

Check Prompt Template for Essay Questions

Figure A8.

Check Prompt Template for Essay Questions

References

- Stanley F Chen, Douglas Beeferman, and Roni Rosenfeld. 1998. Evaluation metrics for language models.

- Yun Da Tsai and Shou De Lin. 2022. Fast online inference for nonlinear contextual bandit based on generative adversarial network. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2202.08867.

- Aaron Grattafiori, Abhimanyu Dubey, Abhinav Jauhri, Abhinav Pandey, Abhishek Kadian, Ahmad Al-Dahle, Aiesha Letman, Akhil Mathur, Alan Schelten, Alex Vaughan, et al. 2024. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2407.21783.

- Pei-Fu Guo, Ying-Hsuan Chen, Yun-Da Tsai, and Shou-De Lin. 2023. Towards optimizing with large language models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2310.05204.

- Pei-Fu Guo, Yun-Da Tsai, and Shou-De Lin. 2024. Benchmarking large language model uncertainty for prompt optimization. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2409.10044.

- Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Saurav Kadavath, Akul Arora, Steven Basart, Eric Tang, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. 2021. Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset. NeurIPS.

- Cho-Jui Hsieh, Si Si, Felix X Yu, and Inderjit S Dhillon. 2023. Automatic engineering of long prompts. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2311.10117.

- Albert, Q. Jiang, Alexandre Sablayrolles, Arthur Mensch, Chris Bamford, Devendra Singh Chaplot, Diego de las Casas, Florian Bressand, Gianna Lengyel, Guillaume Lample, Lucile Saulnier, Lélio Renard Lavaud, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Pierre Stock, Teven Le Scao, Thibaut Lavril, Thomas Wang, Timothée Lacroix, and William El Sayed. 2023a. Mistral 7b. Preprint, arXiv:2310.06825.

- Mingjian Jiang, Yangjun Ruan, Sicong Huang, Saifei Liao, Silviu Pitis, Roger Baker Grosse, and Jimmy Ba. 2023b. Calibrating language models via augmented prompt ensembles.

- Mandar Joshi, Eunsol Choi, Daniel Weld, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2017. triviaqa: A Large Scale Distantly Supervised Challenge Dataset for Reading Comprehension. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:1705.03551.

- Saurav Kadavath, Tom Conerly, Amanda Askell, Tom Henighan, Dawn Drain, Ethan Perez, Nicholas Schiefer, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Nova DasSarma, Eli Tran-Johnson, et al. 2022. Language models (mostly) know what they know. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2207.05221.

- Lorenz Kuhn, Yarin Gal, and Sebastian Farquhar. 2023. Semantic uncertainty: Linguistic invariances for uncertainty estimation in natural language generation. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2302.09664.

- Felix Liawi, Yun-Da Tsai, Guan-Lun Lu, and Shou-De Lin. 2023. Psgtext: Stroke-guided scene text editing with psp module. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2310.13366.

- Stephanie Lin, Jacob Hilton, and Owain Evans. 2021. Truthfulqa: Measuring how models mimic human falsehoods. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2109.07958.

- Stephanie Lin, Jacob Hilton, and Owain Evans. 2022a. Teaching models to express their uncertainty in words. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2205.14334.

- Zi Lin, Jeremiah Zhe Liu, and Jingbo Shang. 2022b. Towards collaborative neural-symbolic graph semantic parsing via uncertainty. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022.

- Mingjie Liu, Yun-Da Tsai, Wenfei Zhou, and Haoxing Ren. 2024. Craftrtl: High-quality synthetic data generation for verilog code models with correct-by-construction non-textual representations and targeted code repair. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2409.12993.

- Andrey Malinin and Mark Gales. 2020. Uncertainty estimation in autoregressive structured prediction. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2002.07650.

- Liangming Pan, Michael Saxon, Wenda Xu, Deepak Nathani, Xinyi Wang, and William Yang Wang. 2023. Automatically correcting large language models: Surveying the landscape of diverse self-correction strategies. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2308.03188.

- Noah Shinn, Federico Cassano, Ashwin Gopinath, Karthik Narasimhan, and Shunyu Yao. 2023. Reflexion: Language agents with verbal reinforcement learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 8634–8652.

- Alon Talmor, Jonathan Herzig, Nicholas Lourie, and Jonathan Berant. 2018. Commonsenseqa: A question answering challenge targeting commonsense knowledge. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1811.00937.

- Gemma Team, Morgane Riviere, Shreya Pathak, Pier Giuseppe Sessa, Cassidy Hardin, Surya Bhupatiraju, Léonard Hussenot, Thomas Mesnard, Bobak Shahriari, Alexandre Ramé, et al. 2024. Gemma 2: Improving open language models at a practical size. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2408.00118.

- Tzu-Hsien Tsai, Yun-Da Tsai, and Shou-De Lin. 2024a. lil’hdoc: an algorithm for good arm identification under small threshold gap. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pages 78–89. Springer.

- Yun-Da Tsai. 2025. Generalizing large language model usability across resource-constrained.

- Yun-Da Tsai and Shou-De Lin. 2024. Handling concept drift in non-stationary bandit through predicting future rewards. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pages 161–173. Springer.

- Yun-Da Tsai, Cayon Liow, Yin Sheng Siang, and Shou-De Lin. 2024b. Toward more generalized malicious url detection models. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 38, pages 21628–21636.

- Yun-Da Tsai, Mingjie Liu, and Haoxing Ren. 2024c. Code less, align more: Efficient llm fine-tuning for code generation with data pruning. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2407.05040.

- Yun-Da Tsai, Tzu-Hsien Tsai, and Shou-De Lin. 2023a. Differential good arm identification. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.07154.

- Yun-Da Tsai, Yu-Che Tsai, Bo-Wei Huang, Chun-Pai Yang, and Shou-De Lin. 2023b. Automl-gpt: Large language model for automl. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2309.01125.

- Yun-Da Tsai, Ting-Yu Yen, Pei-Fu Guo, Zhe-Yan Li, and Shou-De Lin. 2024d. Text-centric alignment for multi-modality learning. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2402.08086.

- Yun-Da Tsai, Ting-Yu Yen, Keng-Te Liao, and Shou-De Lin. 2024e. Enhance modality robustness in text-centric multimodal alignment with adversarial prompting. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2408.09798.

- YunDa Tsai, Mingjie Liu, and Haoxing Ren. 2023c. Rtlfixer: Automatically fixing rtl syntax errors with large language models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2311.16543.

- Xuezhi Wang, Jason Wei, Dale Schuurmans, Quoc Le, Ed Chi, Sharan Narang, Aakanksha Chowdhery, and Denny Zhou. 2023. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. Preprint, arXiv:2203.11171.

- Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Fei Xia, Ed Chi, Quoc V Le, Denny Zhou, et al. 2022. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35, 24824–24837.

- Yixuan Weng, Minjun Zhu, Fei Xia, Bin Li, Shizhu He, Shengping Liu, Bin Sun, Kang Liu, and Jun Zhao. 2022. Large language models are better reasoners with self-verification. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2212.09561.

- Yun-Ang Wu, Yun-Da Tsai, and Shou-De Lin. 2024. Linearapt: An adaptive algorithm for the fixed-budget thresholding linear bandit problem. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2403.06230.

- Miao Xiong, Zhiyuan Hu, Xinyang Lu, Yifei Li, Jie Fu, Junxian He, and Bryan Hooi. 2023. Can llms express their uncertainty? an empirical evaluation of confidence elicitation in llms. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2306.13063.

- Chengrun Yang, Xuezhi Wang, Yifeng Lu, Hanxiao Liu, Quoc V. Le, Denny Zhou, and Xinyun Chen. 2023. Large language models as optimizers. ArXiv, abs/2309.03409.

- Shunyu Yao, Dian Yu, Jeffrey Zhao, Izhak Shafran, Tom Griffiths, Yuan Cao, and Karthik Narasimhan. 2024. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36.

- Shunyu Yao, Jeffrey Zhao, Dian Yu, Nan Du, Izhak Shafran, Karthik Narasimhan, and Yuan Cao. 2022. React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2210.03629.

- Ting-Yu Yen, Yun-Da Tsai, Keng-Te Liao, and Shou-De Lin. 2024. Enhance the robustness of text-centric multimodal alignments. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2407.05036.

- Eric Zelikman, Yuhuai Wu, Jesse Mu, and Noah Goodman. 2022. Star: Bootstrapping reasoning with reasoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 15476–15488.

- Andy Zhou, Kai Yan, Michal Shlapentokh-Rothman, Haohan Wang, and Yu-Xiong Wang. 2023. Language agent tree search unifies reasoning acting and planning in language models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2310.04406.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).