Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

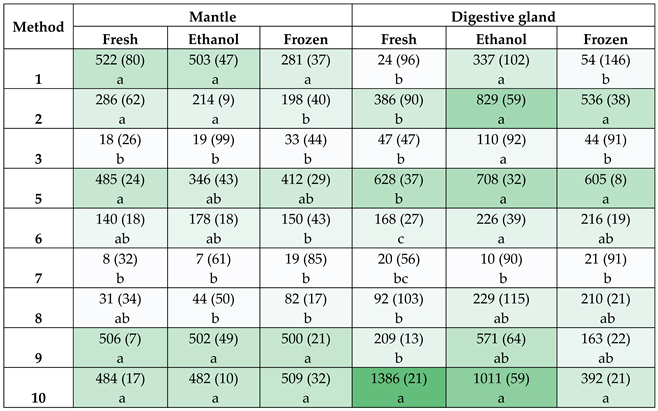

3.1. Spectrophotometric and Fluorometric Measurements

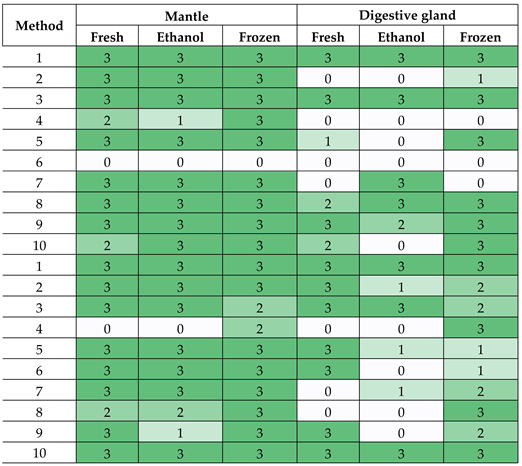

3.2. Amplification of M. gigas DNA

|

3.3. Detection of Oyster Pathogens DNA

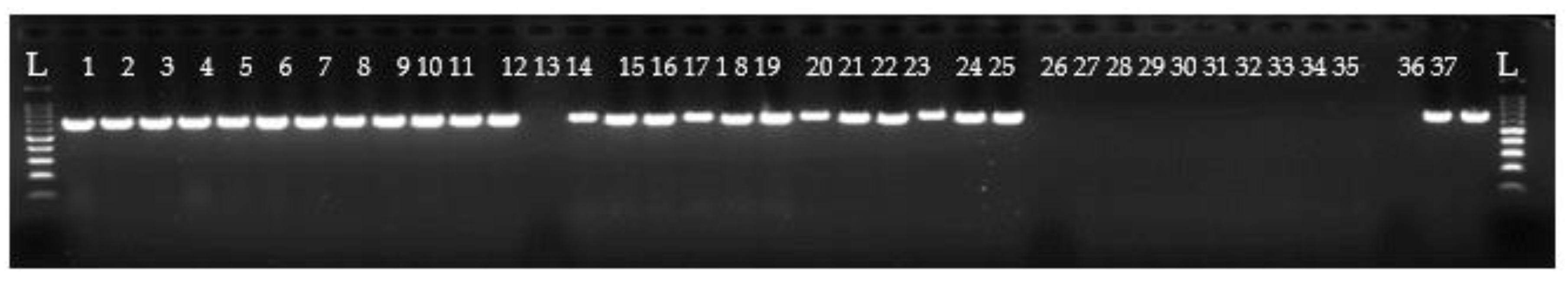

3.3.1. Case Study 1: Detection of Vibrio aestuarianus in M. gigas

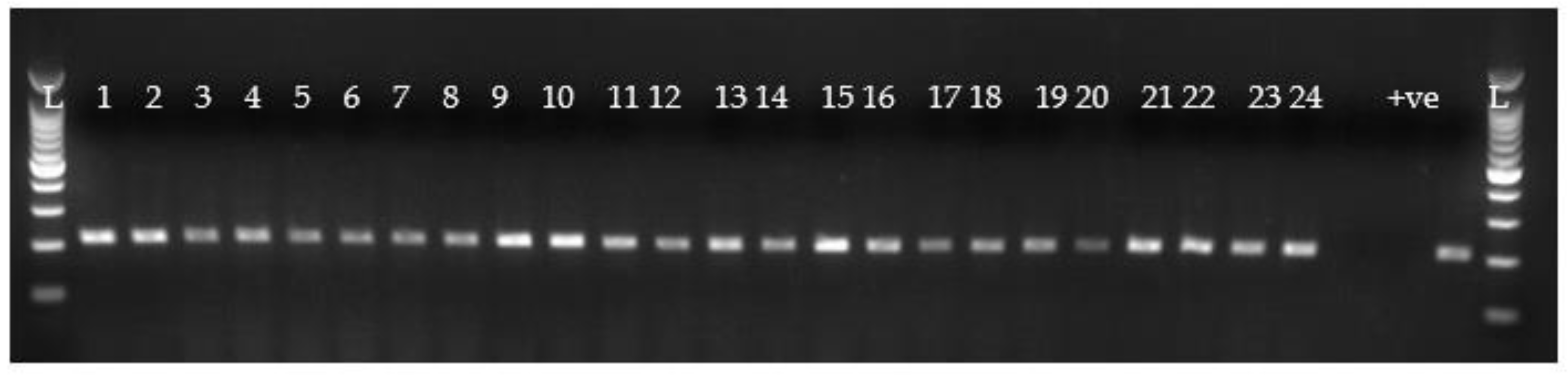

3.3.2. Case Study 2: Detection of OsHV-1 in M. gigas

3.3.3. Case Study 3: Detection of Bonamia ostreae in O. edulis

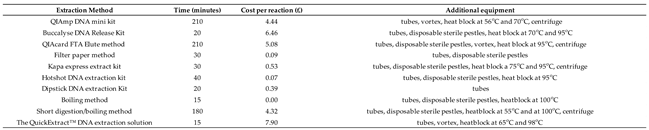

3.4. Analysis of Throughput Time, Cost and Additional Equipment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| The QuickExtract™ DNA extraction solution | (QEDES) |

| Ostreid herpesvirus 1 microvar | (OsHV-1 µvar) |

| Ostreid herpesvirus 1 | (OsHV-1) |

| cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 gene | (COX1) |

| Recombinase Polymerase Amplification | (RPA) |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies | (ONT) |

| Vibrio aestuarianus | (Va) |

| Amoebic Gill Disease | (AGD) |

| carp edema virus | (CEV) |

| Cyprinid herpesvirus | (CyHV-3) |

| loop-mediated isothermal amplification | (LAMP) |

References

- FAO. (2018). The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2018: meeting the sustainable development goals. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Feil, E.J.; Geary, M.; Waine, A.; Ryder, D.; Coyle, N.M.; Cheslett, D.; Thomas, J.C.L.; Bean, T.P.; Joseph, A.W.; Verner-Jeffreys, D.W.; et al. Vibrio aestuarianus clade A and clade B isolates are associated with Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) disease outbreaks across Ireland. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, 001078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushek, D.; Carnegie, R.B.; Arzul, I. Managing marine mollusc diseases in the context of regional and international commerce: policy issues and emerging concerns. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozal, D.F.; Arzul, I.; Carrasco, N.; Rodgers, C. A literature review as an aid to identify strategies for mitigating ostreid herpesvirus 1 in Crassostrea gigas hatchery and nursery systems. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 11, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftos, D.; Allam, B. Immune responses to infectious diseases in bivalves. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 131, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, B.; Renault, T.; Roch, P.; Venier, P.; Gestal, C.; Oubella, R.; Figueras, A.; Pallavicini, A.; Paillard, C. Study of Diseases and the Immune System of Bivalves Using Molecular Biology and Genomics. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2008, 16, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C., Lupo, C., Travers, M. A., Arzul, I., Tourbiez, D., Haffner, P., & others. (2014). Vibrio aestuarianus and Pacific oyster in France a review of 10 years of surveillance. National Shellfisheries Association 106th Annual Meeting, 33.

- Labreuche, Y.; Garnier, M.; Nicolas, J.-L. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Vibrio aestuarianus subsp. francensis subsp. nov., a pathogen of the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 31, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canier, L.; Arzul, I.; Cheslett, D.; Garcia, C.; Geary, M.; Sicard, M.; Orozova, P.; Furones, D.; Tourbiez, D.; Garden, A.; et al. Emergence and clonal expansion of Vibrio aestuarianus lineages pathogenic for oysters in Europe. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 2869–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourbiez, D.; Parizadeh, L.; Haffner, P.; Kozic-Djellouli, A.; Aboubaker, M.; Koken, M.; Dégremont, L.; Travers, M.-A.; Lupo, C. Several strains, one disease: experimental investigation of Vibrio aestuarianus infection parameters in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Veter- Res. 2017, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and welfare (AHAW) Scientific Opinion on the increased mortality events in Pacific oysters,Crassostrea gigas. EFSA J. 2010, 8. [CrossRef]

- Comps, M., Tige, G., & Grizel, H. (1980). Etude ultrastructurale d’un protiste parasite de l’hutre plate. Ostrea.

- Grizel, H., Comps, M., Bonami, J.-R., Cousserans, F., Duthoit, J.-L., & Le Pennec, M.-A. (1974). Recherche sur l’agent de la maladie de la glande digestive de Ostrea edulis Linné. Science et Pêche, 240, 7–30.

- Paley, R.; Joiner, C.; Mulhearn, B.; Gunning, S.; McCullough, R.; Waine, A.; Cano, I. Non-lethal loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay as a point-of-care diagnostics tool for Neoparamoeba perurans, the causative agent of amoebic gill disease. J. Fish Dis. 2020, 43, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.; Wood, G.; Mulhearn, B.; Worswick, J.; Cano, I.; Stone, D.; Paley, R. A Seasonal Study of Koi Herpesvirus and Koi Sleepy Disease Outbreaks in the United Kingdom in 2018 Using a Pond-Side Test. Animals 2021, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, K.; Zaczek-Moczydłowska, M.A.; Mohamed-Smith, L.; Furones, M.D.; Bean, T.P.; Hooper, C.; Campàs, M.; Toldrà, A. A Single-Tube HNB-Based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the Robust Detection of the Ostreid herpesvirus 1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Shi, Y.-H.; Li, C.-H.; Zhou, Q.-J.; Yan, X.-J.; Wang, R.-N.; Zhang, D.-M.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Development and evaluation of a real-time fluorogenic loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay integrated on a microfluidic disc chip (on-chip LAMP) for rapid and simultaneous detection of ten pathogenic bacteria in aquatic animals. J. Microbiol. Methods 2014, 104, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taengphu, S.; Kawasaki, M.; Gan, H.M.; Kayansamruaj, P.; Senapin, S.; Barnes, A.; Wilkinson, S.; Mohan, C.V.; Delamare-Deboutteville, J.; Debnath, P.P.; et al. Rapid genotyping of tilapia lake virus (TiLV) using Nanopore sequencing. J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, K.; Matejusova, I.; Nguyen, L.; Macqueen, D.J.; Gallagher, M.D.; Ruane, N.M. Nanopore sequencing for rapid diagnostics of salmonid RNA viruses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prachumwat, A.; Srisala, J.; Suebsing, R.; Kanitchinda, S.; Chaijarasphong, T. CRISPR-Cas fluorescent cleavage assay coupled with recombinase polymerase amplification for sensitive and specific detection of Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 27, e00485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ren, Y.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Y.; Yin, J.; Qu, Y. Development of a real-time recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of Aeromonas hydrophila. J. Fish Dis. 2020, 44, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, G.; Adams, A.; Weidmann, M.; Lopez-Jimena, B.; Shahin, K.; Ramirez-Paredes, J.G. Development of a recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of Francisella noatunensis subsp. orientalis. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0192979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canier, L.; Stone, D.; Arzul, I.; Cano, I.; Wood, G.; Noyer, M. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the Fast Detection of Bonamia ostreae and Bonamia exitiosa in Flat Oysters. Pathogens 2024, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, R.G.; Ryder, D.; Tidy, A.M.; Hartnell, D.M.; Dean, K.J.; Batista, F.M. Combining Nanopore Sequencing with Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Enables Identification of Dinoflagellates from the Alexandrium Genus, Providing a Rapid, Field Deployable Tool. Toxins 2023, 15, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, M.A.; Ali, N.; Rampazzo, R.d.C.P.; Costa, A.D.T. Current Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods and Their Implications to Point-of-Care Diagnostics. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahilum-Tapay, L.; Dineva, M.A.; Lee, H. Sample preparation: a challenge in the development of point-of-care nucleic acid-based assays for resource-limited settings. Anal. 2007, 132, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H.Y.; Botella, J.R. Advanced DNA-Based Point-of-Care Diagnostic Methods for Plant Diseases Detection. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Hoffmann, M.R. Rapid Detection Methods for Bacterial Pathogens in Ambient Waters at the Point of Sample Collection: A Brief Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, S84–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Wei, Q.; Ostermann, E. Advances in point-of-care nucleic acid extraction technologies for rapid diagnosis of human and plant diseases. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112592–112592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yao, J.D. Bridging the divide: Harmonizing polarized clinical laboratory medicine practices. iLABMED 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adema, C.M. Sticky problems: extraction of nucleic acids from molluscs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, T.; Friedman, C.S.; Ruano, F.; Pepin, J.-F.; Arzul, I.; Boudry, P.; Batista, F.M. Detection of ostreid herpesvirus 1 DNA by PCR in bivalve molluscs: A critical review. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 139, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, T.; Boudry, P.; Batista, F.; Taris, N. Detection of ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) by PCR using a rapid and simple method of DNA extraction from oyster larvae. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2005, 64, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leray, M.; Ranwez, V.; Agudelo, N.; Yang, J.Y.; Meyer, C.P.; Mills, S.C.; Boehm, J.T.; Machida, R.J. A new versatile primer set targeting a short fragment of the mitochondrial COI region for metabarcoding metazoan diversity: application for characterizing coral reef fish gut contents. Front. Zoöl. 2013, 10, 34–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haffner, P.; De Decker, S.; Saulnier, D. Real-time PCR assay for rapid detection and quantification of Vibrio aestuarianus in oyster and seawater: A useful tool for epidemiologic studies. J. Microbiol. Methods 2009, 77, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault; Arzul Herpes-like virus infections in hatchery-reared bivalve larvae in Europe: specific viral DNA detection by PCR. J. Fish Dis. 2001, 24, 161–167. [CrossRef]

- EURL for Molluscs Diseases website (EURL for Molluscs Diseases, 2nd edition, February 2023). Avaliable online: https://www.eurlmollusc.eu/content/download/137231/file/B.ostreae%26B.exitiosa%20_TaqmanRealTimePCR_editionN%C2%B02.pdf (Accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Villalba, A.; Abollo, E.; Navas, J.; Ramilo, A. Species-specific diagnostic assays for Bonamia ostreae and B. exitiosa in European flat oyster Ostrea edulis: conventional, real-time and multiplex PCR. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2013, 104, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrader, C., Schielke, A., Ellerbroek, L & Johne, R. (2012). PCR inhibitors – occurrence, properties and removal. Journal of Applied Microbiology. Journal of applied microbiology, 113(5), 1014-1026. [CrossRef]

- Jamet, E. An eye-tracking study of cueing effects in multimedia learning. Comput. Human Behav. 2014, 32, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.J.; Kotov, A.A. A new African lineage of the Daphnia obtusa group (Cladocera: Daphniidae) disrupts continental vicariance patterns. J. Plankton Res. 2010, 32, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walthall, A. C., Tice, A. K., & Brown, M. W. (2016). New species of flamella (Amoebozoa, variosea, gracilipodida) isolated from a freshwater pool in Southern Mississippi, USA. Acta Protozoologica, 55(2), 111–117. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).