Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Reagents and Materials

2.2. Physical and Chemical Characterization of the Tap Water Sample

2.3. Coating of the Glass Chips and SPR Setup

2.4. Immobilization of Laccases on The thin Cr-Au Film

2.5. Calibration Curve and Analysis of Samples

2.6. Analytical Parameters

3. Results and Discusión

3.1. Physical and Chemical Characterization of the Tap Water Sample

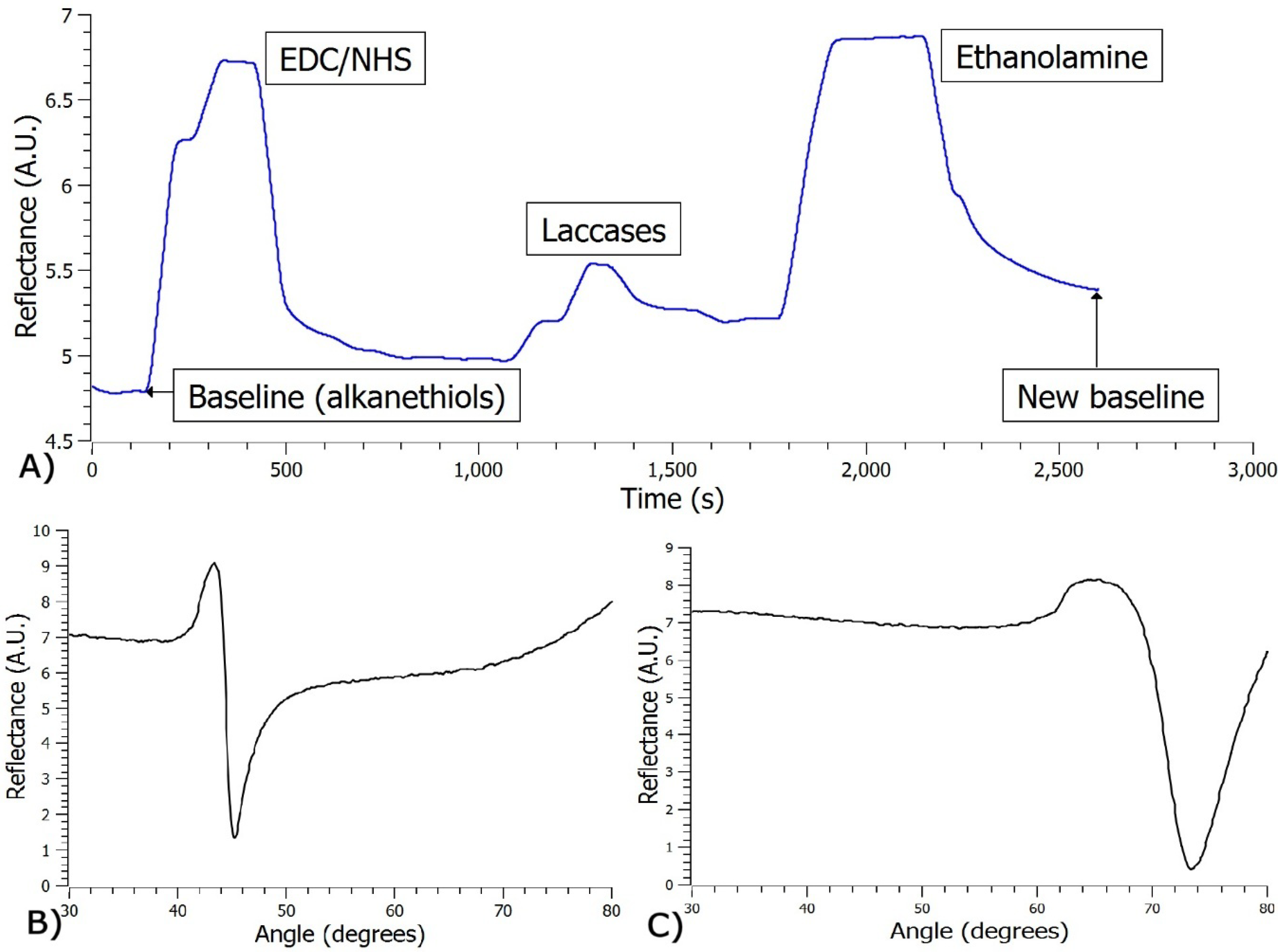

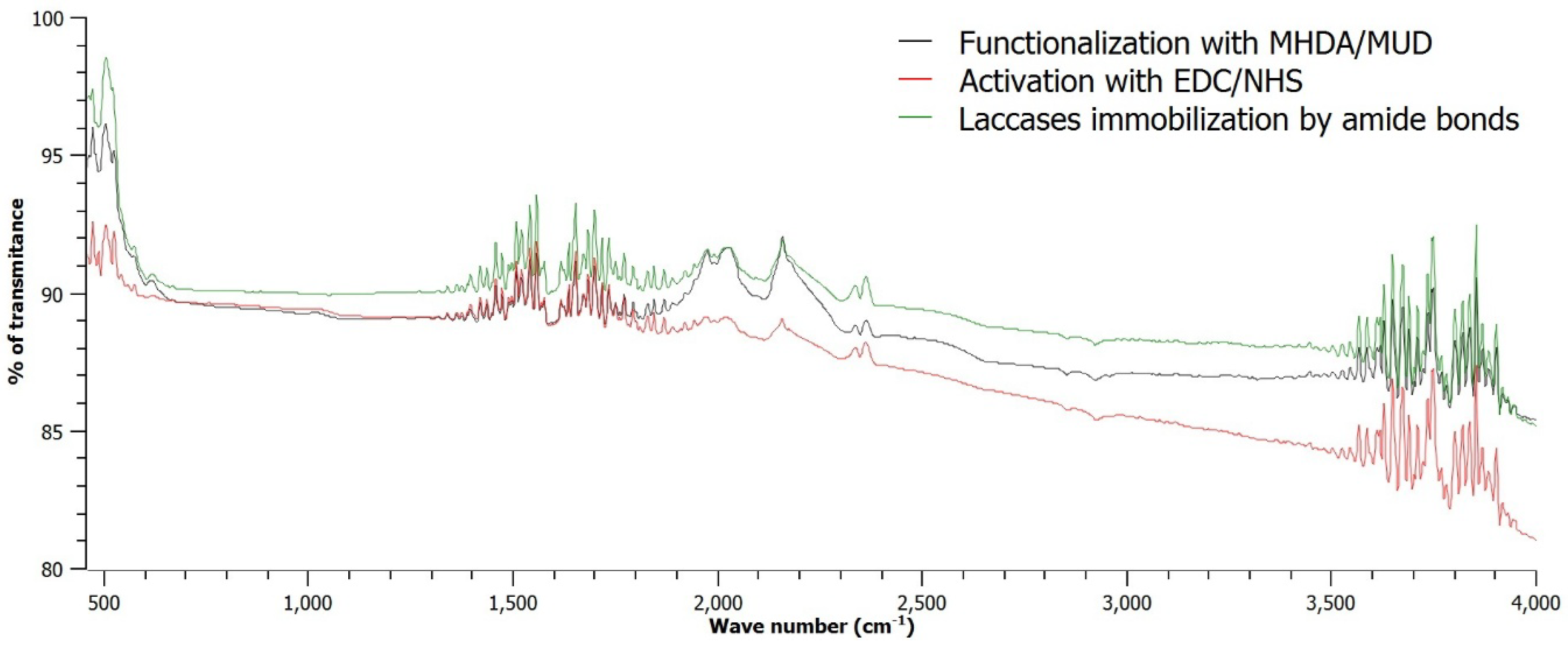

3.2. Immobilization of Laccases on the Thin Cr-Au Film

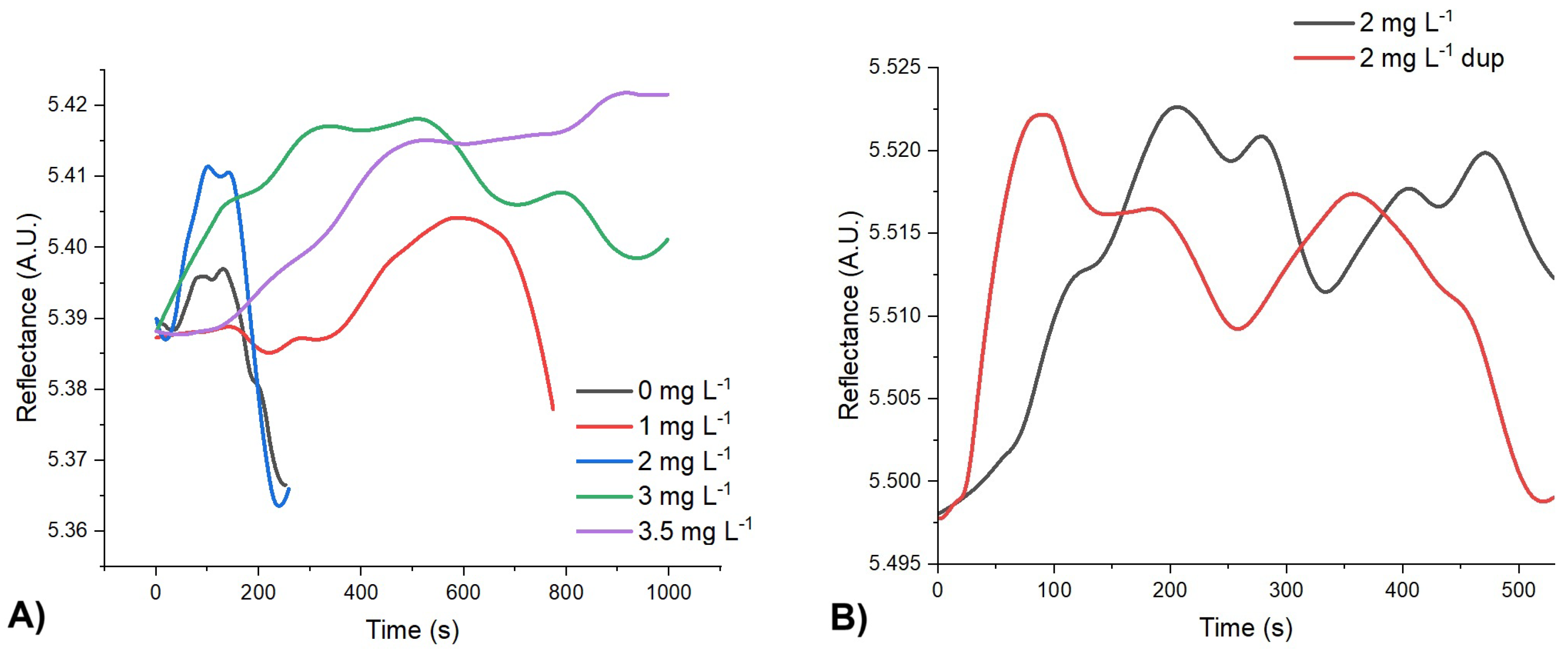

3.3. Calibration Curve and Analysis of the Samples

3.4. Analytical Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

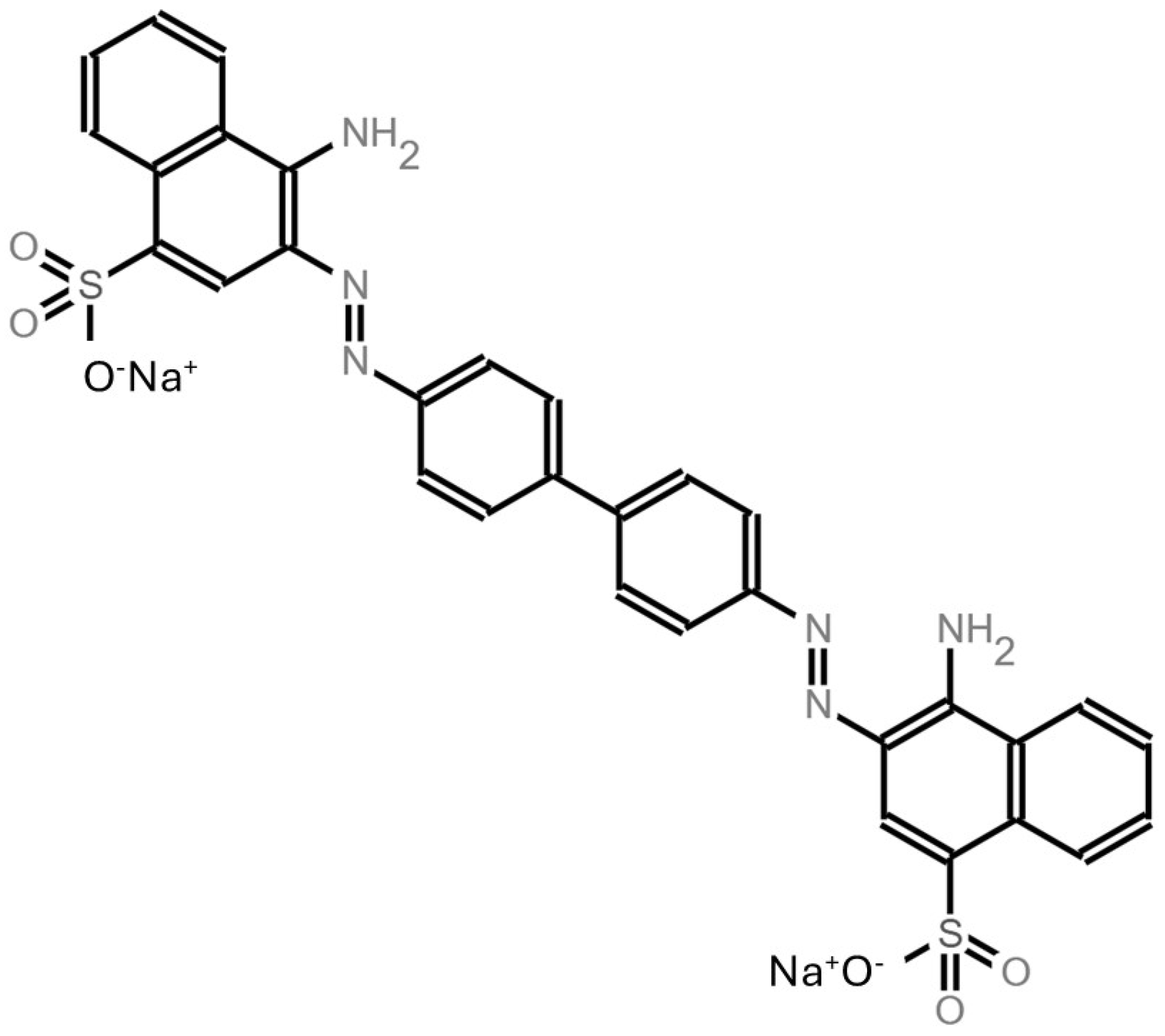

- Quintanilla-Villanueva GE, Sicardi-Segade A, Luna-Moreno D, Núñez-Salas RE, Villarreal-Chiu JF, Rodríguez-Delgado MM. Recent Advances in Congo Red Degradation by TiO2-Based Photocatalysts Under Visible Light. Catalysts 2025;15:84.

- Oyekanmi AA, Ahmad A, Mohd Setapar SH, Alshammari MB, Jawaid M, Hanafiah MM, et al. Sustainable durio zibethinus-derived biosorbents for Congo red removal from aqueous solution: statistical optimization, isotherms and mechanism studies. Sustainability 2021;13:13264.

- Roy A, Ananda Murthy HC, Ahmed HM, Islam MN, Prasad R. Phytogenic Synthesis of Metal/Metal Oxide Nanoparticles for Degradation of Dyes. J Renew Mater 2022;10:1911–30. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui SI, Allehyani ES, Al-Harbi SA, Hasan Z, Abomuti MA, Rajor HK, et al. Investigation of Congo red toxicity towards different living organisms: a review. Processes 2023;11:807.

- Yang Y, Liu K, Sun F, Liu Y, Chen J. Enhanced performance of photocatalytic treatment of Congo red wastewater by CNTs-Ag-modified TiO 2 under visible light. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022:1–10.

- Hernández-Zamora M, Martínez-Jerónimo F. Congo red dye diversely affects organisms of different trophic levels: a comparative study with microalgae, cladocerans, and zebrafish embryos. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019;26:11743–55.

- Oyekanmi AA, Ahmad A, Mohd Setapar SH, Alshammari MB, Jawaid M, Hanafiah MM, et al. Sustainable durio zibethinus-derived biosorbents for Congo red removal from aqueous solution: statistical optimization, isotherms and mechanism studies. Sustainability 2021;13:13264.

- Rafique MA, Kiran S, Javed S, Ahmad I, Yousaf S, Iqbal N, et al. Green synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles using Allium cepa peels for degradation of Congo red direct dye: An environmental remedial approach. Water Science and Technology 2021;84:2793–804. [CrossRef]

- Qin X, Bakheet AAA, Zhu X. Fe 3 O 4@ ionic liquid-β-cyclodextrin polymer magnetic solid phase extraction coupled with HPLC for the separation/analysis of congo red. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2017;14:2017–22.

- Liu F, Zhang S, Wang G, Zhao J, Guo Z. A novel bifunctional molecularly imprinted polymer for determination of Congo red in food. RSC Adv 2015;5:22811–7.

- Sahraei R, Farmany A, Mortazavi SS, Noorizadeh H. Spectrophotometry determination of Congo red in river water samples using nanosilver. Toxicol Environ Chem 2012;94:1886–92.

- Ganash A, Alshammari S, Ganash E. Development of a novel electrochemical sensor based on gold nanoparticle-modified carbon-paste electrode for the detection of congo red dye. Molecules 2022;28:19.

- Liu L, Mi Z, Wang J, Liu Z, Feng F. A label-free fluorescent sensor based on yellow-green emissive carbon quantum dots for ultrasensitive detection of congo red and cellular imaging. Microchemical Journal 2021;168:106420.

- Zulfajri M, Sudewi S, Damayanti R, Huang GG. Rambutan seed waste-derived nitrogen-doped carbon dots with l-aspartic acid for the sensing of Congo red dye. RSC Adv 2023;13:6422–32.

- de Paula HMC, Coelho YL, Agudelo AJP, de Paula Rezende J, Ferreira GMD, Ferreira GMD, et al. Kinetics and thermodynamics of bovine serum albumin interactions with Congo red dye. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2017;159:737–42.

- Sadrolhosseini AR, Ghasemi E, Pirkarimi A, Hamidi SM, Ghahrizjani RT. Highly sensitive surface plasmon resonance sensor for detection of Methylene Blue and Methylene Orange dyes using NiCo-Layered Double Hydroxide. Opt Commun 2023;529:129057.

- Quintanilla-Villanueva GE, Luna-Moreno D, Blanco-Gámez EA, Rodríguez-Delgado JM, Villarreal-Chiu JF, Rodríguez-Delgado MM. A novel enzyme-based SPR strategy for detection of the antimicrobial agent chlorophene. Biosensors (Basel) 2021;11:43.

- Quintanilla-Villanueva GE, Rodríguez-Quiroz O, Sánchez-Álvarez A, Rodríguez-Delgado JM, Villarreal-Chiu JF, Luna-Moreno D, et al. An Innovative Enzymatic Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Biosensor Designed for Precise Detection of Glycine Amino Acid. Biosensors (Basel) 2025;15:81.

- Sánchez-Álvarez A, Quintanilla-Villanueva GE, Rodríguez-Quiroz O, Rodríguez-Delgado MM, Villarreal-Chiu JF, Sicardi-Segade A, et al. Use of Laccase Enzymes as Bio-Receptors for the Organic Dye Methylene Blue in a Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor. Sensors 2024;24:8008.

- Kyomuhimbo HD, Brink HG. Applications and immobilization strategies of the copper-centred laccase enzyme; a review. Heliyon 2023;9.

- Homola J, Yee SS, Gauglitz G. Surface plasmon resonance sensors. Sens Actuators B Chem 1999;54:3–15.

- Nguyen HH, Park J, Kang S, Kim M. Surface plasmon resonance: a versatile technique for biosensor applications. Sensors 2015;15:10481–510.

- SSA. NOM-127-SSA1-2021: Agua para uso y consumo humano. Límites permisibles de la calidad del agua. 2021. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle_popup.php?codigo=5650705 (accessed May 20, 2025).

- Sánchez-Álvarez A, Luna-Moreno D, Silva-Hernández O, Rodríguez-Delgado MM. Application of SPR Method as an Approach to Gas Phase Sensing of Volatile Compound Profile in Mezcal Spirits Conferred by Agave Species. Chemosensors 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. World Health Organization; 2011.

- Lacour V, Moumanis K, Hassen WM, Elie-Caille C, Leblois T, Dubowski JJ. Formation kinetics of mixed self-assembled monolayers of alkanethiols on GaAs (100). Langmuir 2017;35:4415–27.

- NIH. 16-Mercaptohexadecanoic acid. Compound Summary 2025. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/16-Mercaptohexadecanoic-acid#section=13C-NMR-Spectra (accessed May 26, 2025).

- S. Martínez. Interpretación de espectros. Analítica Experimental, vol. I, UNAM; 2023.

- Tsai TC, Liu CW, Wu YC, Ondevilla NAP, Osawa M, Chang HC. In situ study of EDC/NHS immobilization on gold surface based on attenuated total reflection surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS). Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2019;175:300–5.

| Parameter | Result | Parameter | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total hardness | 25 mg L-1 | Total chloride | 0 mg L-1 |

| Free chloride | 0 mg L-1 | Fluoride | 0 mg L-1 |

| Iron | 0 mg L-1 | Cyanuric acid | 0 mg L-1 |

| Copper | 0 mg L-1 | Ammonia chloride | 0 mg L-1 |

| Lead | 0 mg L-1 | Bromine | 0 mg L-1 |

| Nitrate | 25 mg L-1 | Total alkalinity | 40 mg L-1 |

| Nitrite | 0 mg L-1 | Carbonate | 240 mg L-1 |

| MPS | 0 mg L-1 | pH | 7.6 |

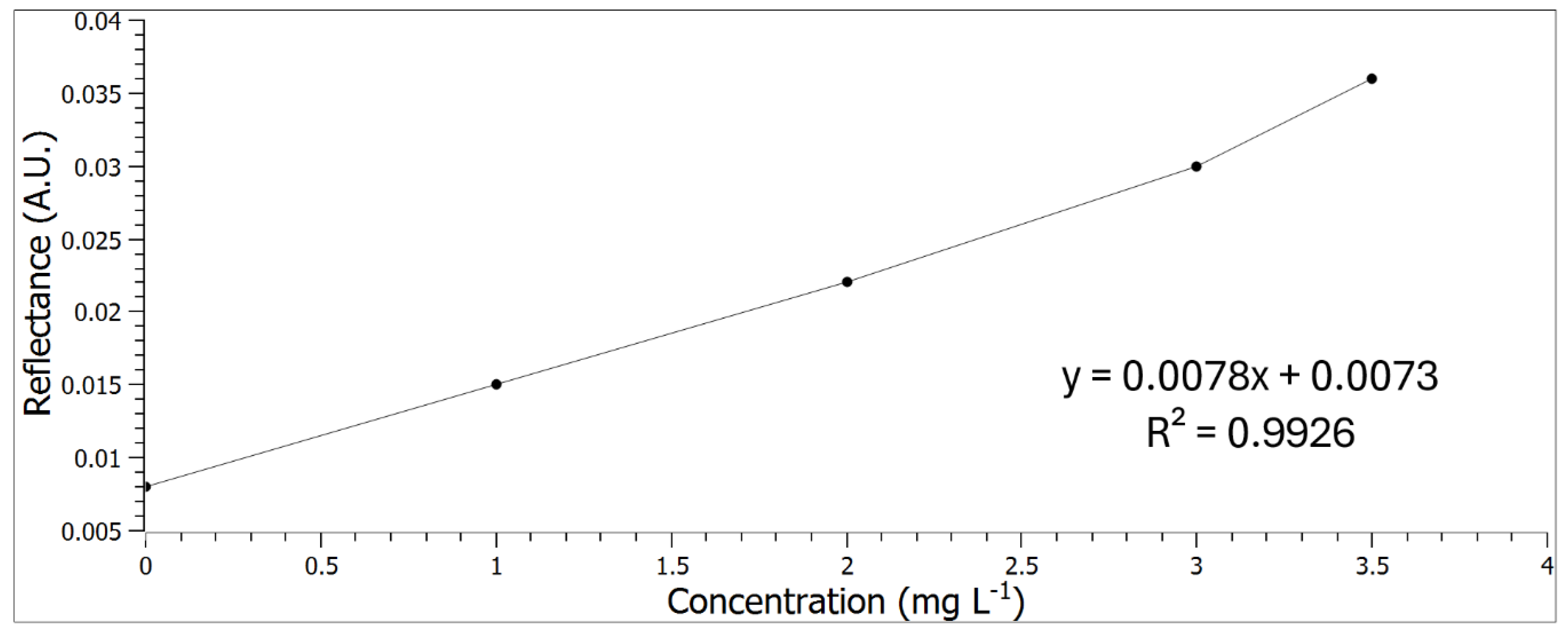

| Analytical parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Equation of the line | y = 0.0078x + 0.0073 |

| R2 | 0.9926 |

| LOD | 0.008 mg L-1 |

| LOQ | 0.028 mg L-1 |

| % of recovery | 104.48%±10.41 |

| Working range | 0-3.5 mg L-1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).