Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Variables of interest |

Total N (%) |

Blood pressure | Chi-square | p-value | |

| Normal | High | ||||

| Non-modifiable risk factors: | |||||

| Age, years <35 ≥35 |

32 (45.71%) 38 (54.29%) |

24 /32 (/75%) 19/38 (50%) |

8 /32(25%) 19/38 (70.4%) |

4.58 |

0.032 |

| Gender Male Female |

11 (15.70%) 59 (84.30%) |

9/11 (81.8%) 34/59 (57.6%) |

2/11 (18.2%) 25/59 (42.4%) |

2.29 |

0.130 |

| Modifiable risk factors: | |||||

| Alcohol consumption Yes No |

26 (37.1%) 44 (62.9%) |

15/26(57.7%) 28/44 (63.6%) |

11/26 (42.3%) 16/44 (36.%) |

0.24 |

0.621 |

| Cigarette smoking Yes No |

13 (18.6%) 57 (81.4%) |

9/13(20.9%) 34/57 (59.1%) |

4/13 (30.8%) 23/57 (40.4%) |

0.41 |

0.521 |

| History of type 2 Diabetes mellitus Yes No |

4 (6.2%) 61 (93.8%) |

3/4 (75.0%) 39/61 (63.9%) |

1/4 (25.0%) 22/61 (36.1%) |

0.16 |

0.686 |

| Body mass index Normal Overweight Obesity |

29 (41.4%) 20 (28.6%) 21 (30%) |

24/29 (82.8%) 10/20(50.0%) 9/21(42.9%) |

5/29 (17.2%) 10/20 (50%) 12/21 (57.1%) |

9.74 |

0.008 |

| Variables of interest |

Total N (%) |

Blood pressure | Chi-square | p-value | |

| Normal | High | ||||

| Lipid profile: | |||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L Desirable High |

60 (93.8%) 4 (6.3%) |

38/60 (63.3%) 1/4 (25.0%) |

22/60 (36.7%) 3 /4 (75%) |

2.32 |

0.128 |

| LDL, mmol/L Desirable High |

45 (97.8%) 1 (2.2%) |

28/45 (62.2%) 0/1 (0%) |

17/45 (37.8)% 1/1 (100%) |

1.60 |

0.205 |

| HDL, mmol/L Desirable Low |

45 (70.3%) 19 (29.7%) |

26/45 (57.8%) 14/19 (35%) |

19/45 (42.2%) 5/19 (20.8%) |

1.44 |

0.230 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L Desirable High |

46 (82.1%) 10 (17.9%) |

33/46 (77.1%) 1/10(10.0%) |

13/46 (28.3%) 9/10 (90.0%) |

13.15 |

0.0002 |

| Ratio total cholesterol/HDL <4 4-6 >6 |

56 (88.9%) 6 (9.5%) 1/1 (1.6%) |

36/56 (64.3%) 2/6(33.3%) 1/1(100%) |

20/56 (83.3%) 4/6(66.7%) 0 /1 (0%) |

2.83 |

0.024 |

| Blood glucose tests | |||||

| Random blood glucose, mmol/L Normal Abnormal |

69 (98.6%) 1 (1.4%) |

42/69 (60.9%) 1/1 (100%) |

27/69 (39.1%) 0 /1(0%) |

0.64 |

0.424 |

| Glycated Hb, mmol/L Normal Abnormal |

48 (68.6%) 22 (31.4%) |

26/48 (60.5%) 17/22 (77.3%) |

22/48 (81.5%) 5/22 (22.72%) |

3.40 |

0.065 |

| Coagulation disorders | |||||

| D-dimmer Positive Negative |

30 (46.2%) 35 (53.8%) |

16/30 (53.3%) 24/35 (68.5%) |

14/30 (46.6%) 11/35 (31.4%) |

1.58 |

0.208 |

| Variables of interest |

Total N (%) |

Blood pressure | Chi-square | p-value | |

| Normal | High | ||||

| Metabolic syndrome | |||||

| MS by NCEP Present Absent |

31 (44.3%) 39 (55.7%) |

15/31 (48.4%) 28/39 (71.7%) |

16/31 (51.6%) 11/39 (28.2%) |

3.07 |

0.080 |

| MS by IDF Present Absent |

31 (44.3%) 39 (55.7%) |

16/31 (51.6%) 27/39 (69.2%) |

15/31 (48.4%) 12 /39(30.8%) |

1.58 |

0.209 |

| HIV associated risk factors | |||||

| WHO staging at ART initiation Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 |

34 (49.3%) 15 (21.7%) 18 (26.1%) 2 (2.9%) |

20/34 (58.8%) 8 /15(53.3%) 12/18 (66.7%) 2/2 (100%) |

14 /34(41.2%) 7/15 (46.7%) 6 /18(33.3%) 0 /2(0%) |

1.96 |

0.58 |

| Current HIV viral load, copies/mL Detectable Undetectable |

39 (58.2%) 28 (41.8%) |

22/39 (56.4%) 20/28 (71.4%) |

17/39 (43.6%) 8 /28(28.6%) |

1.00 |

0.32 |

| Level of immunosuppression Severe Advanced Mild Normal |

4 (6%) 10 (14.9%) 7 (10.4%) 46 (68.7%) |

3 /4(75.0%) 6/10 (60.0%) 4 /7(57.1%) 29 /46(63.0%) |

1/4 (25.0%) 4/10 (40.0%) 3 /7(42.8%) 17 /46(36.9%) |

0.38 |

0.943 |

| ART associated risk factors | |||||

| Initial ART regiments** 1T3E 1TFE 1S3E 1S3N 1T3N |

25 (35.7%) 33 (47.1%) 3 (4.3%) 5 (7.1%) 4 (5.7%) |

15/25 (60.0%) 20/33 (60.9%) 3/3 (100%) 3/5(60.0%) 2 /4(50.0%) |

10/25 (40.0%) 13/33(39.4%) 0/3 (0%) 2/5 (40.0%) 2/4 (50.0%) |

2.14 |

0.71 |

| Current ART regiments 1T3E 1TFE 1S3E 1S3N 1T3N |

16 (23.2%) 48 (69.6%) 2 (2.9%) 1 (1.4%) 2 (2.9%) |

10/16 (62.5%) 30/48 (62.5%) 2 /2(100.0%) 0/1 (0%) 0/2 (0%) |

6/16 (37.5%) 18/48 (37.5%) 0/2 (0%) 1 /1(100.0%) 2/2 (100%) |

6.02 |

0.019 |

| ART duration, years <5 years 5-10 years >10 years |

36 (51.4%) 24 (34.3%) 10 (14.3%) |

23/36 (63.5%) 14/24(58.3%) 6/10 (60.0%) |

13 /36(36.1%) 10/24 (41.7%) 4/10 (40.0%) |

0.20 |

0.91 |

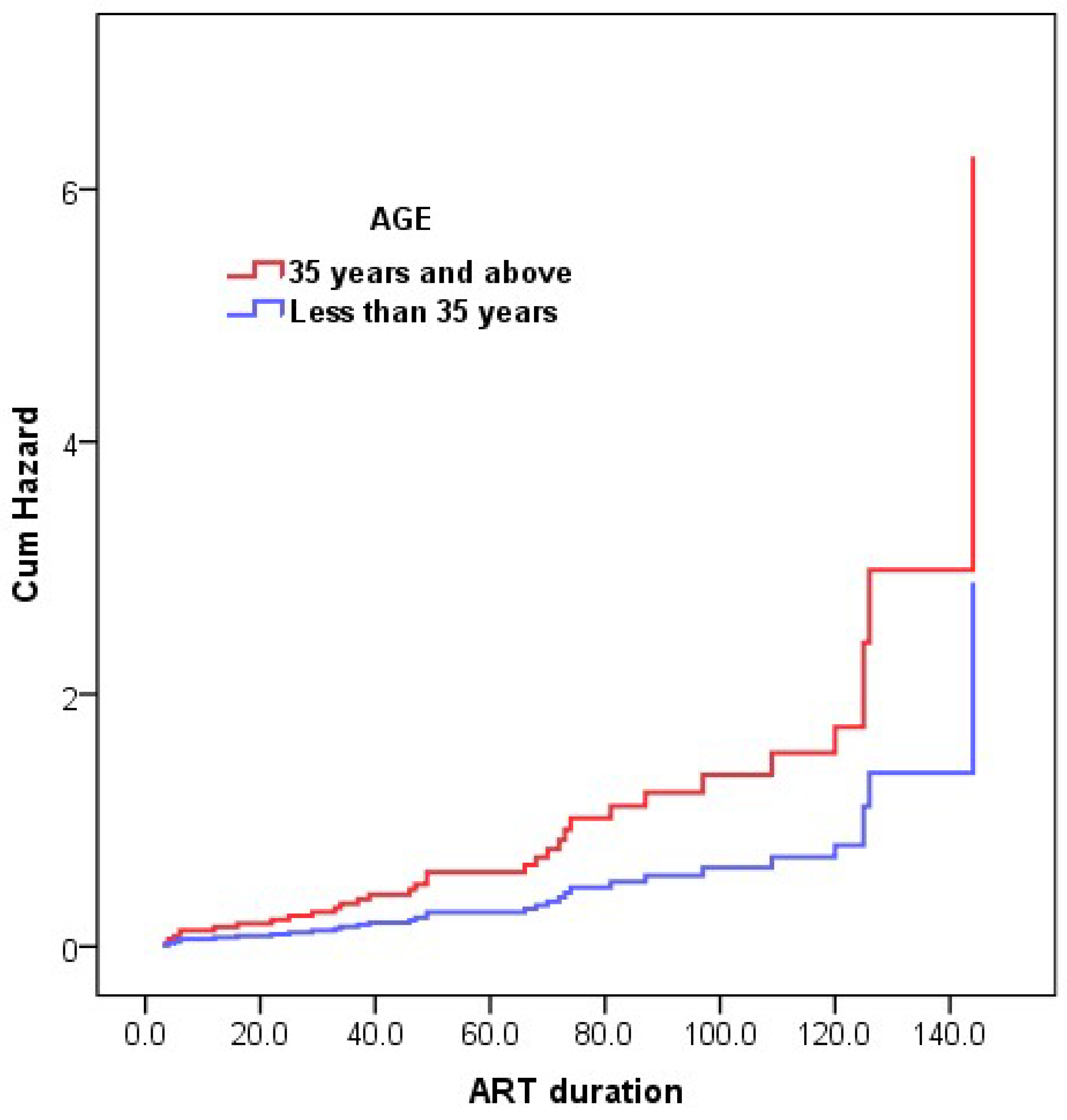

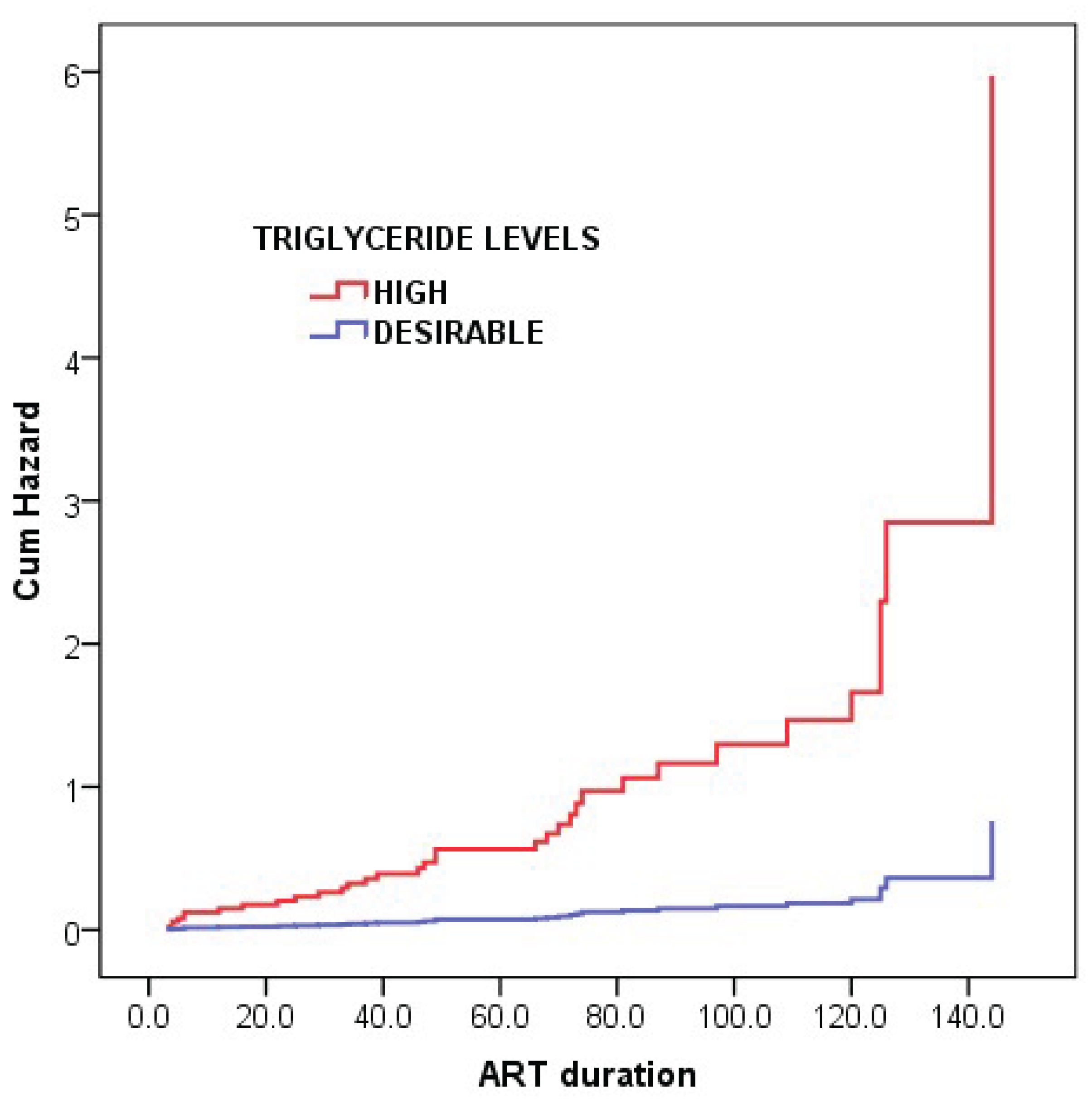

| Risk factors |

Hazard Ratio (HR) (95% CI for HR) |

B-coefficient | SE | Wald chi-square | p-value | |

| Age, years |

2.169 (1.035–4.546) |

0.774 |

0.378 |

4.206 |

0.040* |

|

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 7.855 (1.037–59.469) |

2.061 | 1.033 | 3.982 |

0.046* |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ART | Anti-retroviral therapy |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CD4 | Cluster of differentiation 4 |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| NCD | Non-communicable diseases |

| NHLS | National Health Laboratory Services |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- UNAIDS. FACT SHEET—WORLD AIDS DAY 2019 Geneva: GLOBAL HIV STATISTICS; 2019: Accessed online 28 May 2025 https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf.

- The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic. The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic USA: KFF; 2019 updated Sep 9. Accessed online May 28, 2025, from: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-global-hivaids-epidemic.

- Kooij, K.W.; Zhang, W.; Trigg, J.; Cunningham, N.; O Budu, M.; E Marziali, M.; Lima, V.D.; A Salters, K.; Barrios, R.; Montaner, J.S.G.; et al. Life expectancy and mortality among males and females with HIV in British Columbia in 1996–2020: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Heal. 2025, 10, e228–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiedu-Addo, S.N.A.; Appeaning, M.; Magomere, E.; Ansa, G.A.; Bonney, E.Y.; Quashie, P.K. The urgent need for newer drugs in routine HIV treatment in Africa: the case of Ghana. Front. Epidemiology 2025, 5, 1523109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyo, R.C.; Sigwadhi, L.N.; Carries, S.; Mkhwanazi, Z.; Bhana, A.; Bruno, D.; Davids, E.L.; Van Hout, M.-C.; Govindasamy, D. Health-related quality of life among people living with HIV in the era of universal test and treat: results from a cross-sectional study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. HIV Clin. Trials 2024, 25, 2298094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okyere, J.; Ayebeng, C.; Owusu, B.A.; Dickson, K.S. Prevalence and factors associated with hypertension among older people living with HIV in South Africa. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafane-Matemane, L.F.; Craig, A.; Kruger, R.; Alaofin, O.S.; Ware, L.J.; Jones, E.S.W.; Kengne, A.P. Hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: the current profile, recent advances, gaps, and priorities. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2024, 39, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Perel, P.; Mensah, G.A.; Ezzati, M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartey, E.T.; A Tetteh, R.; Anto, F.; Sarfo, B.; Kudzi, W.; Adanu, R.M. Risk of hypertension in adult patients on antiretroviral therapy: a propensity score matching analysis. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ghandakly, E.; Moudgil, R.; Holman, K. Cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: Risk assessment and management. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2025, 92, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- management. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine, 92(3), 159-167.

- Davis, K.; Perez-Guzman, P.; Hoyer, A.; Brinks, R.; Gregg, E.; Althoff, K.N.; Justice, A.C.; Reiss, P.; Gregson, S.; Smit, M. Association between HIV infection and hypertension: a global systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirigo, A.T.; Yilma, D.; Astatkie, A.; Debebe, Z. The association between dolutegravir-based antiretrovirals and high blood pressure among adults with HIV in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugisha, N. , Ghanem, L., Komi, O. A., Noureddine, R., Shariff, S., Wojtara, M.,... & Uwishema, O. (2025). Addressing Cardiometabolic Challenges in HIV: Insights, Impact, and Best Practices for Optimal Management—A Narrative Review. Health Science Reports, 8(4), e70727.

- Derick, K.I.; Khan, Z. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, Control of Hypertension, and Availability of Hypertension Services for Patients Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.; Moore, T.; Long, D.M.; Burkholder, G.A.; Willig, A.; Wyatt, C.; Heath, S.; Muntner, P.; Overton, E.T. Risk Factors for Incident Hypertension Within 1 Year of Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy Among People with HIV. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2022, 38, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuro, U.; Oladimeji, K.E.; Pulido-Estrada, G.-A.; Apalata, T.R. Risk Factors Attributable to Hypertension among HIV-Infected Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy in Selected Rural Districts of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 11196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mivumbi, J. P. , & Gbadamosi, M. A. (2025). Hypertension Prevalence and Associated Factors in HIV Positive Women at Kicukiro, Kigali, Rwanda: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. medRxiv, 2025-03.

- Siddiqui, M.; Moore, T.; Long, D.M.; Burkholder, G.A.; Willig, A.; Wyatt, C.; Heath, S.; Muntner, P.; Overton, E.T. Risk Factors for Incident Hypertension Within 1 Year of Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy Among People with HIV. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2022, 38, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailin, S.S.; Koethe, J.R.; Rebeiro, P.F. The pathogenesis of obesity in people living with HIV. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2023, 19, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfair, R. , Cheever, L., & Mermin, J. is National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day CDC encourages people aged 50 or older to get tested for HIV At a glance. 18 September.

- Chen, A.; Chan, Y.-K.; Mocumbi, A.O.; Ojji, D.B.; Waite, L.; Beilby, J.; Codde, J.; Dobe, I.; Nkeh-Chungag, B.N.; Damasceno, A.; et al. Hypertension among people living with human immunodeficiency virus in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdela, A.A.; Yifter, H.; Reja, A.; Shewaamare, A.; Ofotokun, I.; Degu, W.A. Prevalence and risk factors of metabolic syndrome in Ethiopia: describing an emerging outbreak in HIV clinics of the sub-Saharan Africa – a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Karama, M.; Kamiya, Y. HIV infection, and overweight and hypertension: a cross-sectional study of HIV-infected adults in Western Kenya. Trop. Med. Heal. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Chan, Y.-K.; Mocumbi, A.O.; Ojji, D.B.; Waite, L.; Beilby, J.; Codde, J.; Dobe, I.; Nkeh-Chungag, B.N.; Damasceno, A.; et al. Hypertension among people living with human immunodeficiency virus in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaviz, K.I.; Patel, S.A.; Siedner, M.J.; Goss, C.W.; Gumede, S.B.; Johnson, L.C.; Ordóñez, C.E.; Laxy, M.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Heine, M.; et al. Integrating hypertension detection and management in HIV care in South Africa: protocol for a stepped-wedged cluster randomized effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2024, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spach, D. H. Spach, D. H. . National HIV Curriculum. Adverse Effects of Antiretroviral Medications(2025). Accessed online May 29,2025:https://www.hiv.uw.edu/go/antiretroviral-therapy/adverse-effects/core-concept/all?utm_source.

- Denu, M.K.I.; Revoori, R.; Buadu, M.A.E.; Oladele, O.; Berko, K.P. Hypertension among persons living with HIV/AIDS and its association with HIV-related health factors. AIDS Res. Ther. 2024, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Statistics 2023. Accessed online May 29, 2025. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/world-health-statistic-reports/2023/world-health-statistics-2023_20230519_.pd.

- Fryar, C. D. , Kit, B., Carroll, M. D., & Afful, J. (2024). Hypertension Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control among Adults Ages 18 and Older: United States, August 2021—August 2023.

- Demissie, B.M.; Girmaw, F.; Amena, N.; Ashagrie, G. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated factors among patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Ethiopia, 2023: asystematic review and meta analysis. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoobi, F.; Jalali, Z.; Bidaki, R.; Lotfi, M.A.; Esmaeili-Nadimi, A.; Khalili, P. Metabolic syndrome: a population-based study of prevalence and risk factors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global HIV Programme. Accessed online May 29, 2025. https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/treatment/advanced-hiv-disease. 3.

- Ren, Q.-W.; Teng, T.-H.K.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Tse, Y.-K.; Tsang, C.T.W.; Wu, M.-Z.; Tse, H.-F.; Voors, A.A.; Tromp, J.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. Triglyceride levels and its association with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes among patients with heart failure. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023, 148, E9–E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, L.; Mu, Z. Effects of different weight loss dietary interventions on body mass index and glucose and lipid metabolism in obese patients. Medicine 2023, 102, e33254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.B.; Beara, I.; Torović, L. Regulatory Compliance of Health Claims on Omega-3 Fatty Acid Food Supplements. Foods 2024, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Fukui, S.; Shinozaki, T.; Asano, T.; Yoshida, T.; Aoki, J.; Mizuno, A. Lipid Profiles After Changes in Alcohol Consumption Among Adults Undergoing Annual Checkups. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e250583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M. , Wilsgaard, T., Grimsgaard, S., Hopstock, L. A., & Hansson, P. (2023). Associations between postprandial triglyceride concentrations and sex, age, and body mass index: cross-sectional analyses from the Tromsø study 2015–2016. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, 1158383.

- Li, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; He, S.; Jian, W.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Peng, H. Triglyceride-glucose index predicts adverse cardiovascular events in patients with H-type hypertension combined with coronary heart disease: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Chan, Y.-K.; Mocumbi, A.O.; Ojji, D.B.; Waite, L.; Beilby, J.; Codde, J.; Dobe, I.; Nkeh-Chungag, B.N.; Damasceno, A.; et al. Hypertension among people living with human immunodeficiency virus in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).