Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Motivation

1.2. Key Contribution

1.3. Structure of This Paper

2. Literature Review

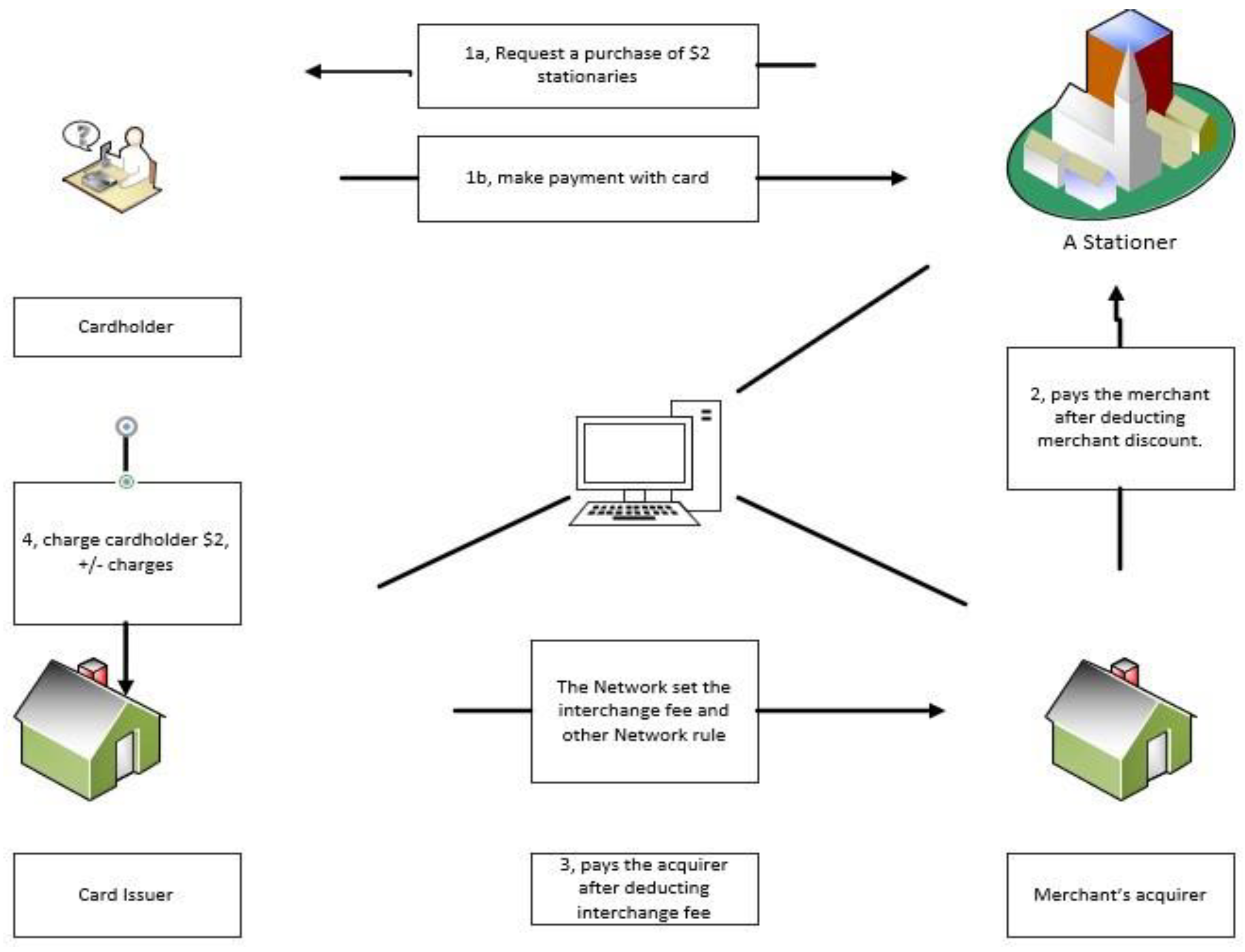

2.1. Card Payment System

2.1.1. Credit Card

2.1.2. Debit Card

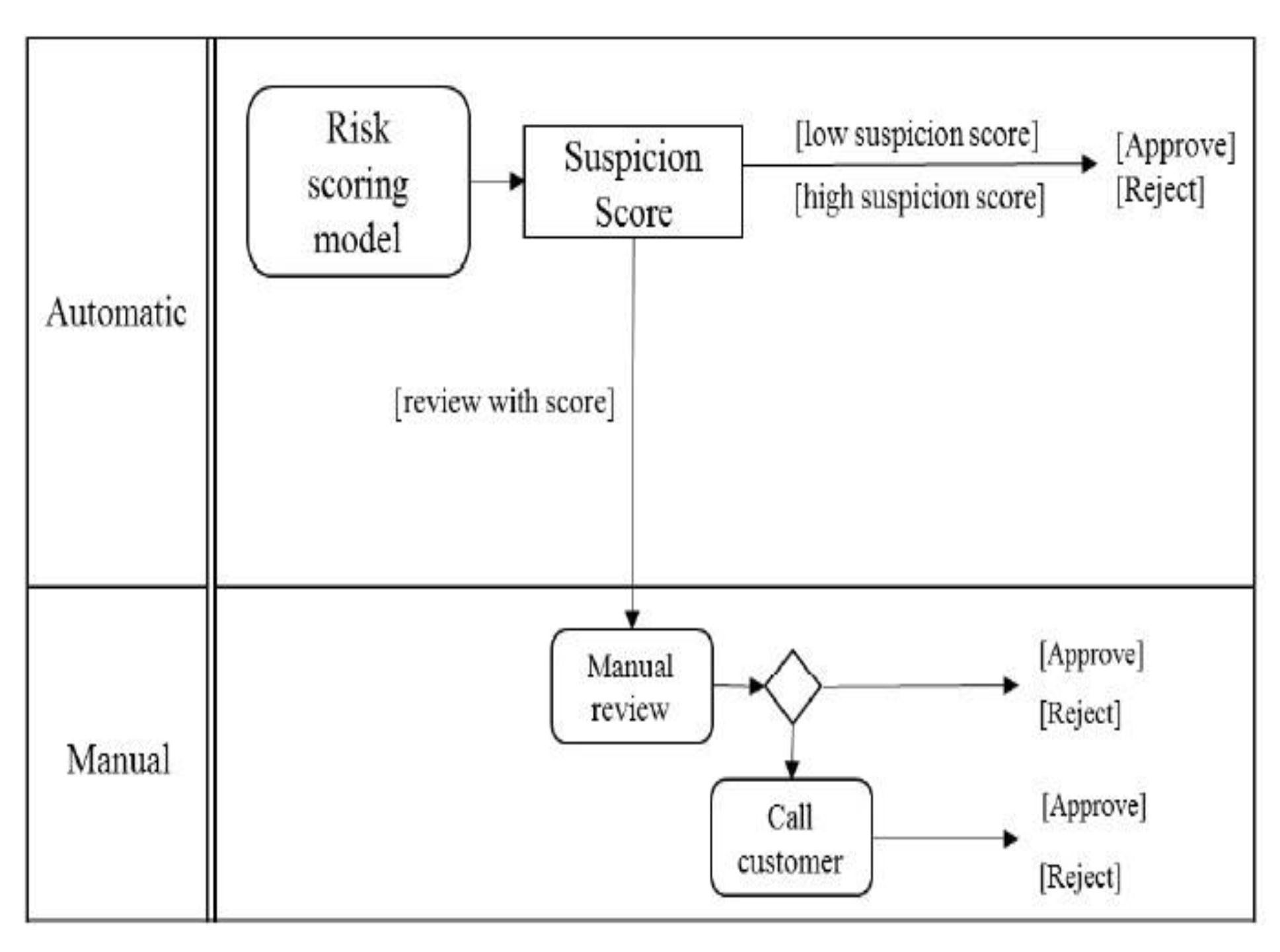

2.2. Financial Fraud SYSTEM

2.2.1. Bankruptcy Fraud

2.2.2. Application Fraud

2.2.3. Theft/Counterfeit Fraud

2.3. Machine Learning

2.3.1. Fuzzy-Logic

2.3.2. K-Nearest Neighbors

2.3.3. Hidden Markov Model

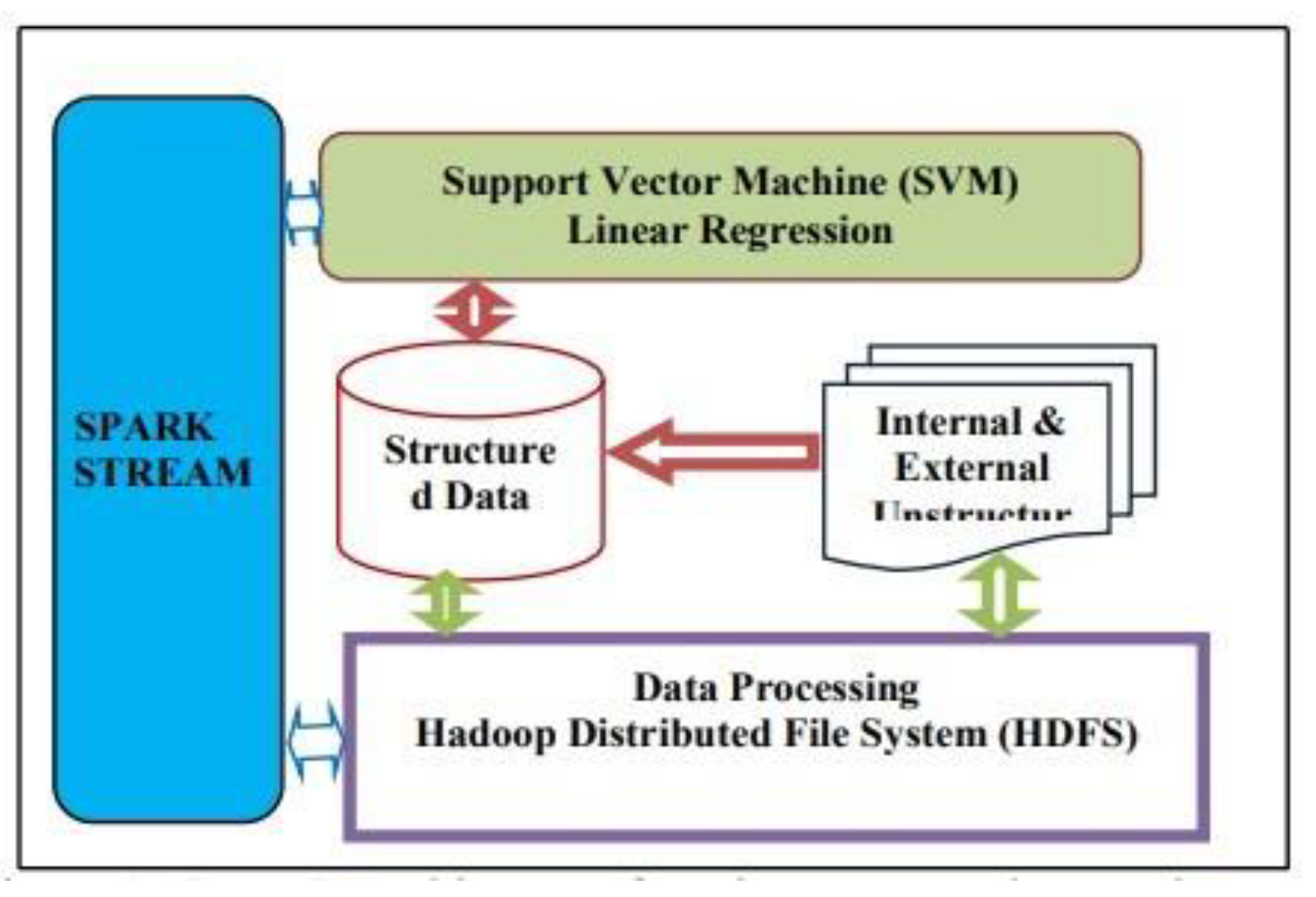

2.3.4. Support Vector Machine

2.4. Deep Learning

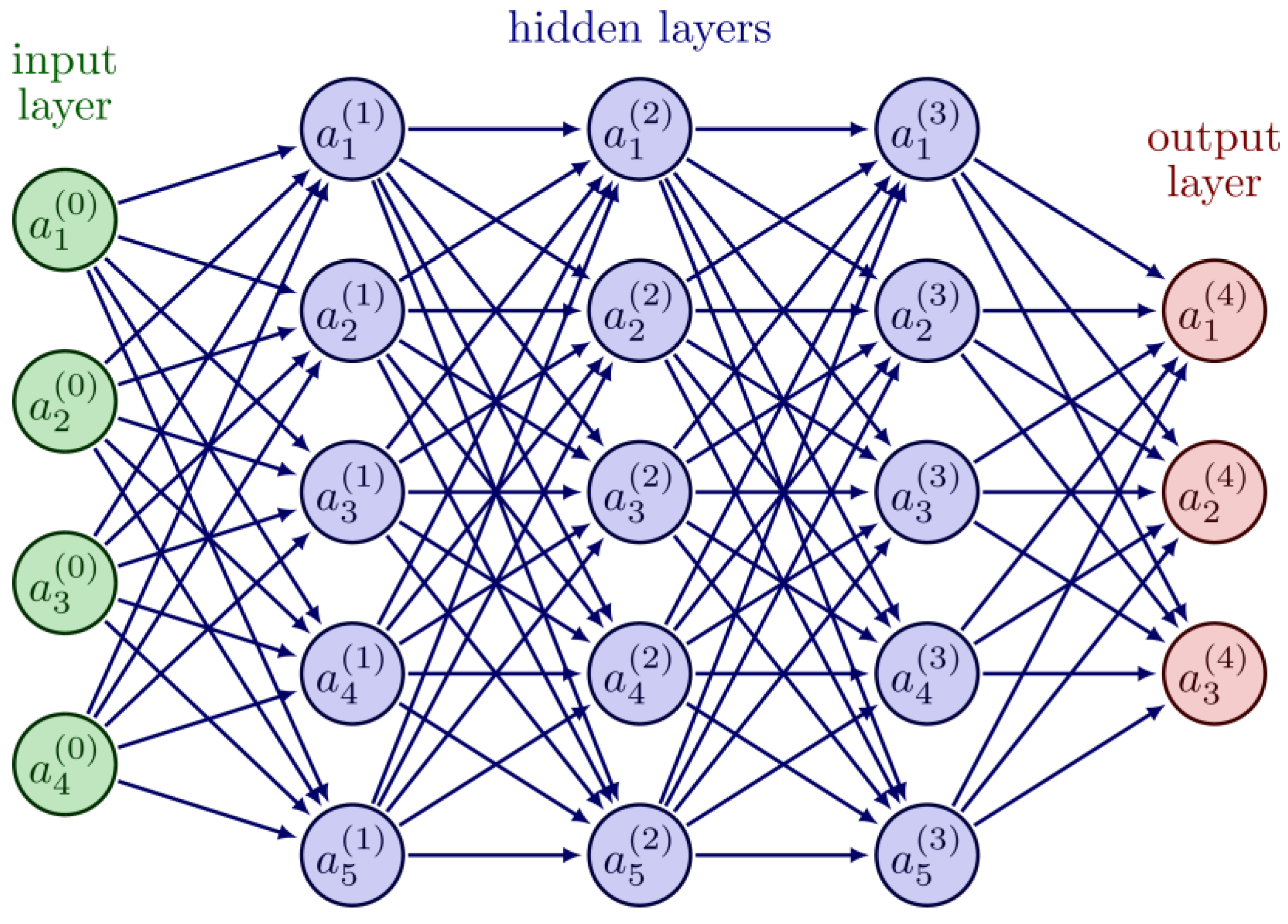

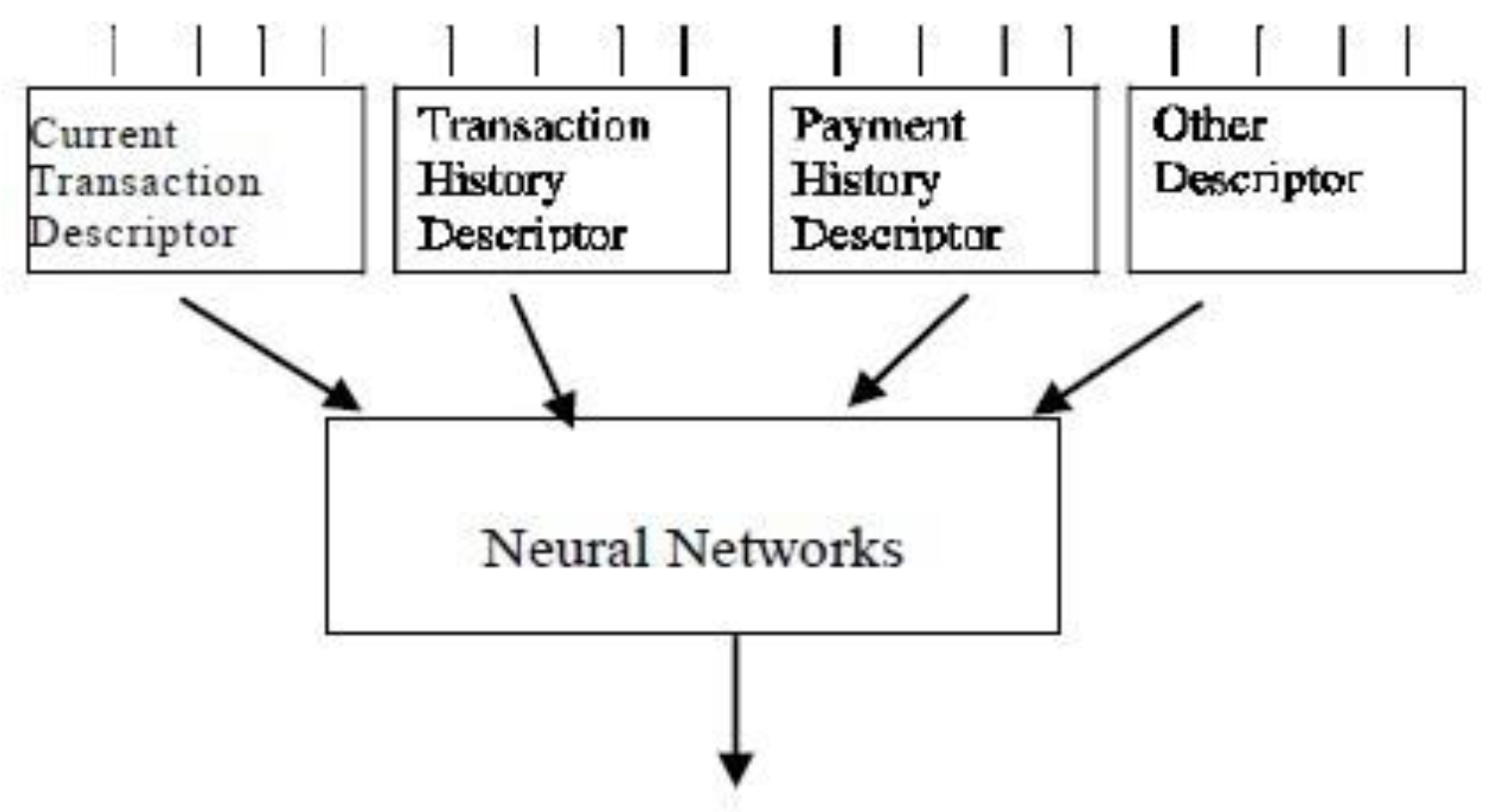

2.4.1. Neural Network

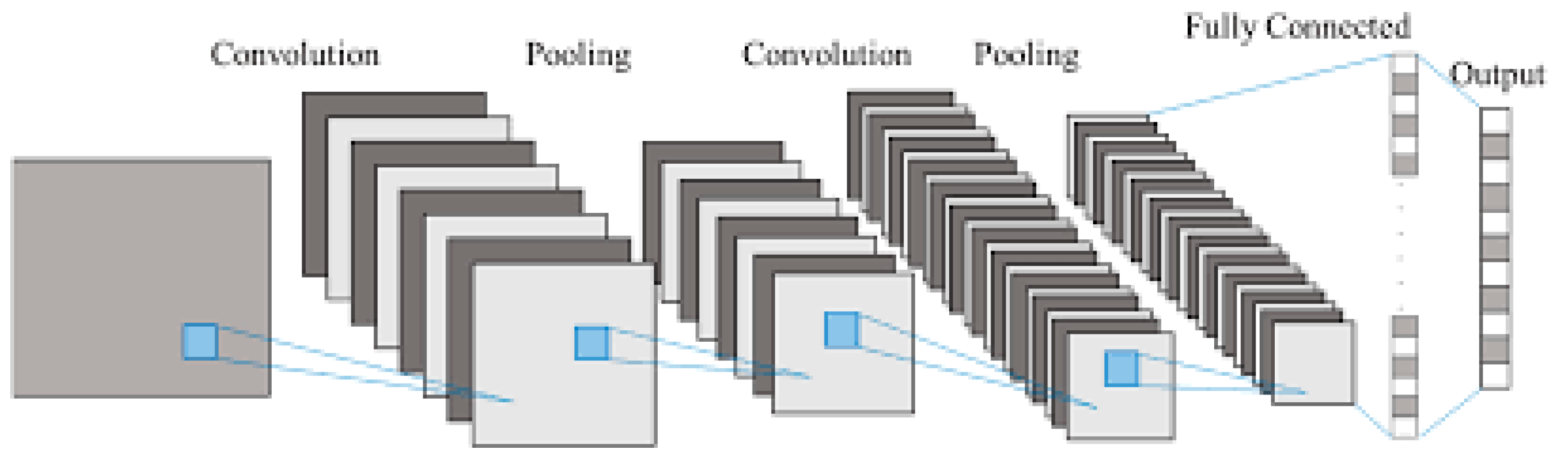

Convolutional Neural Network

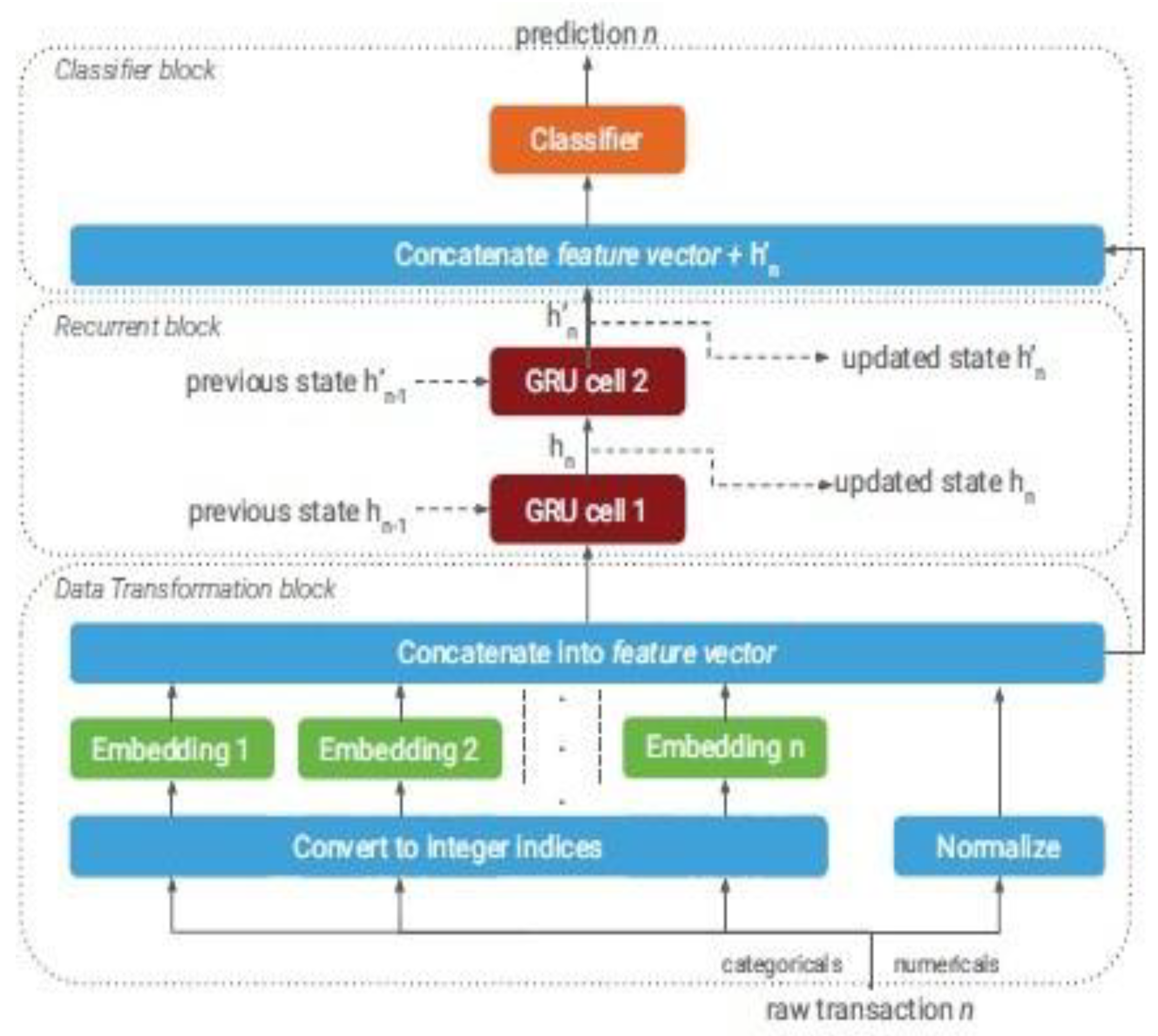

2.5. Related Work

2.6. Conclusion

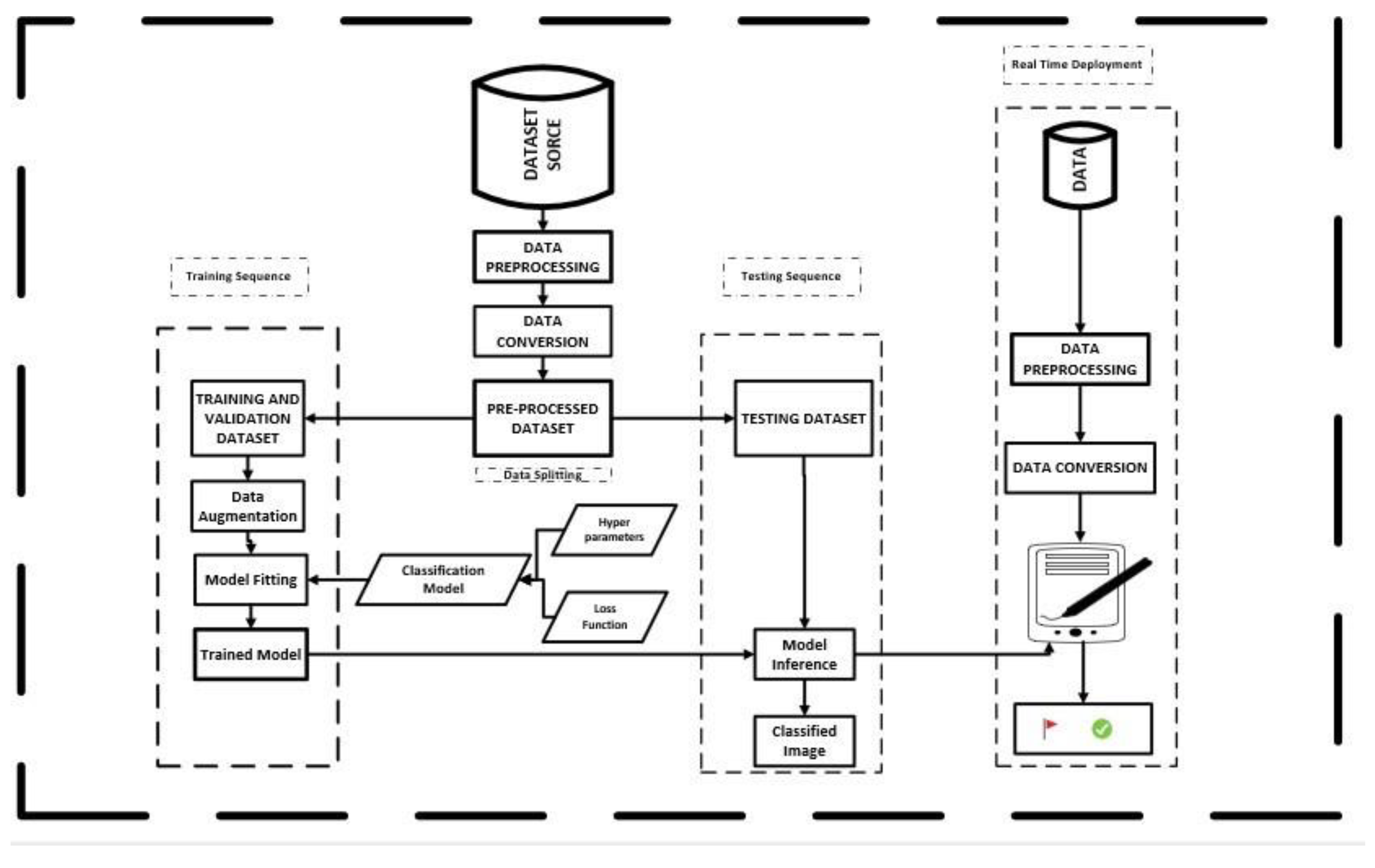

3. Material and Methodology

3.1. Introduction

3.2. Proposed Framework

3.2.1. Data Conversion

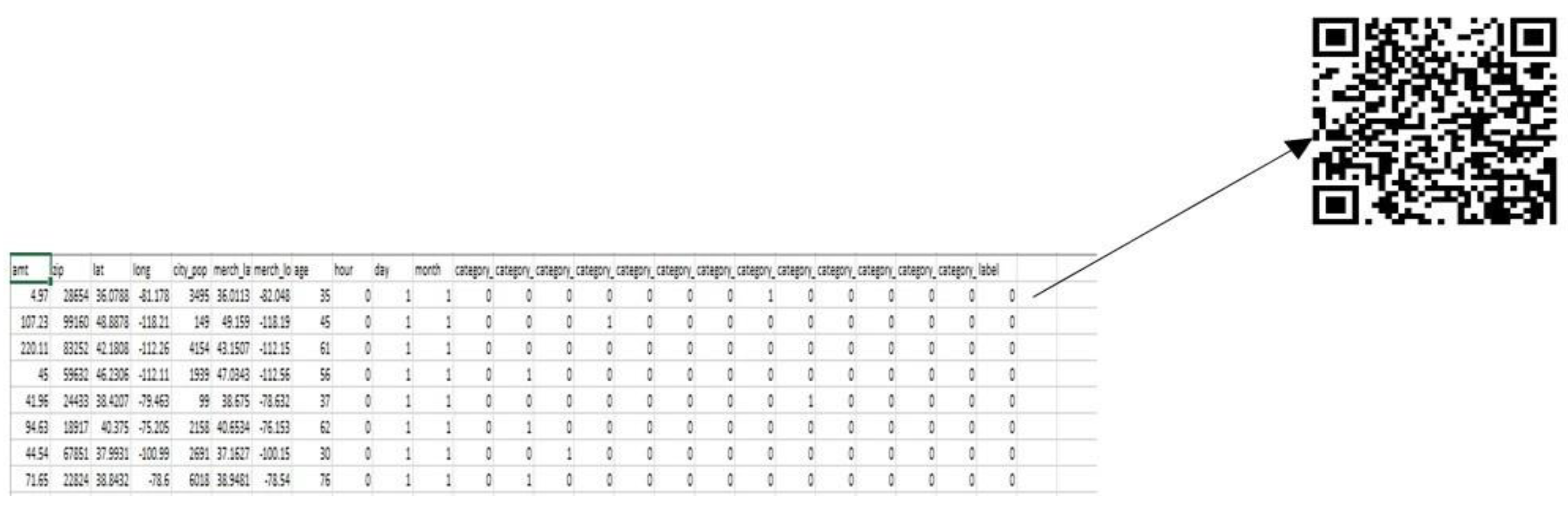

Data Description

Data Pre-Processing

Data Splitting

3.2.2. Feature Extraction

Model Implementation

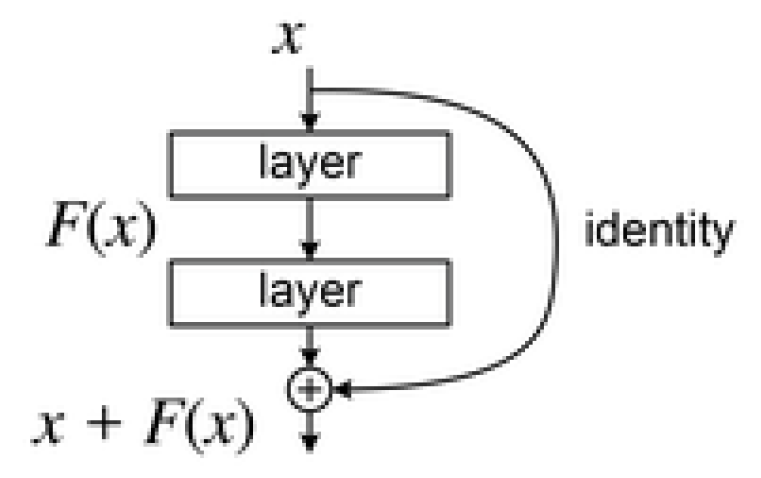

Residual Network

3.2.3. Model Learning

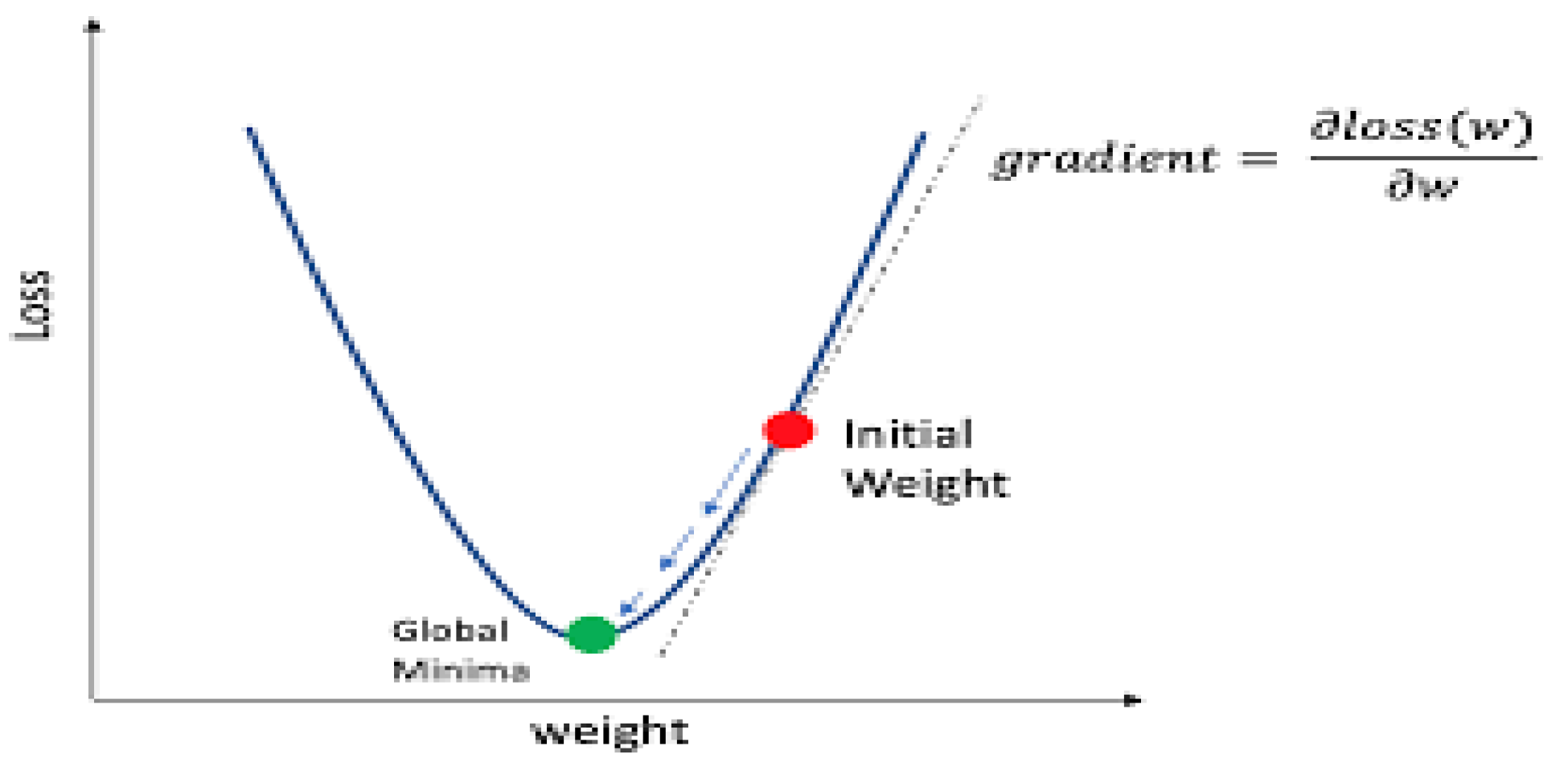

Optimizer

Pre-Trained Weight

Loss Function

Learning Rate

Early Stopping

Batch Size

Epoch

Evaluation Metrics

Hardware Resources and Specification

3.2.4. Summary

4. Analysis, Implementation and Results

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Implementation

4.2.1. Library Importation

4.2.2. Data Analysis

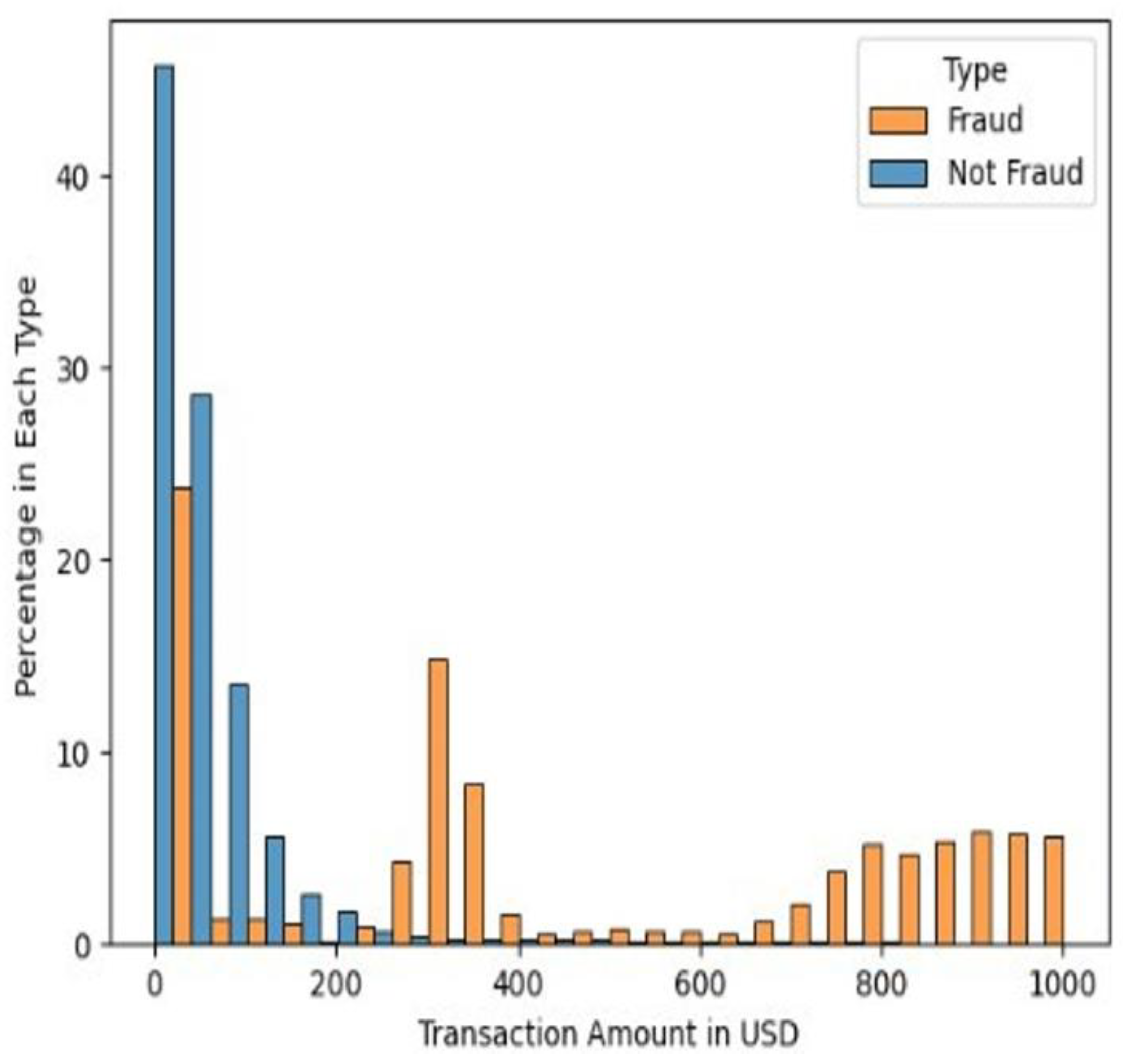

Amount and Fraud

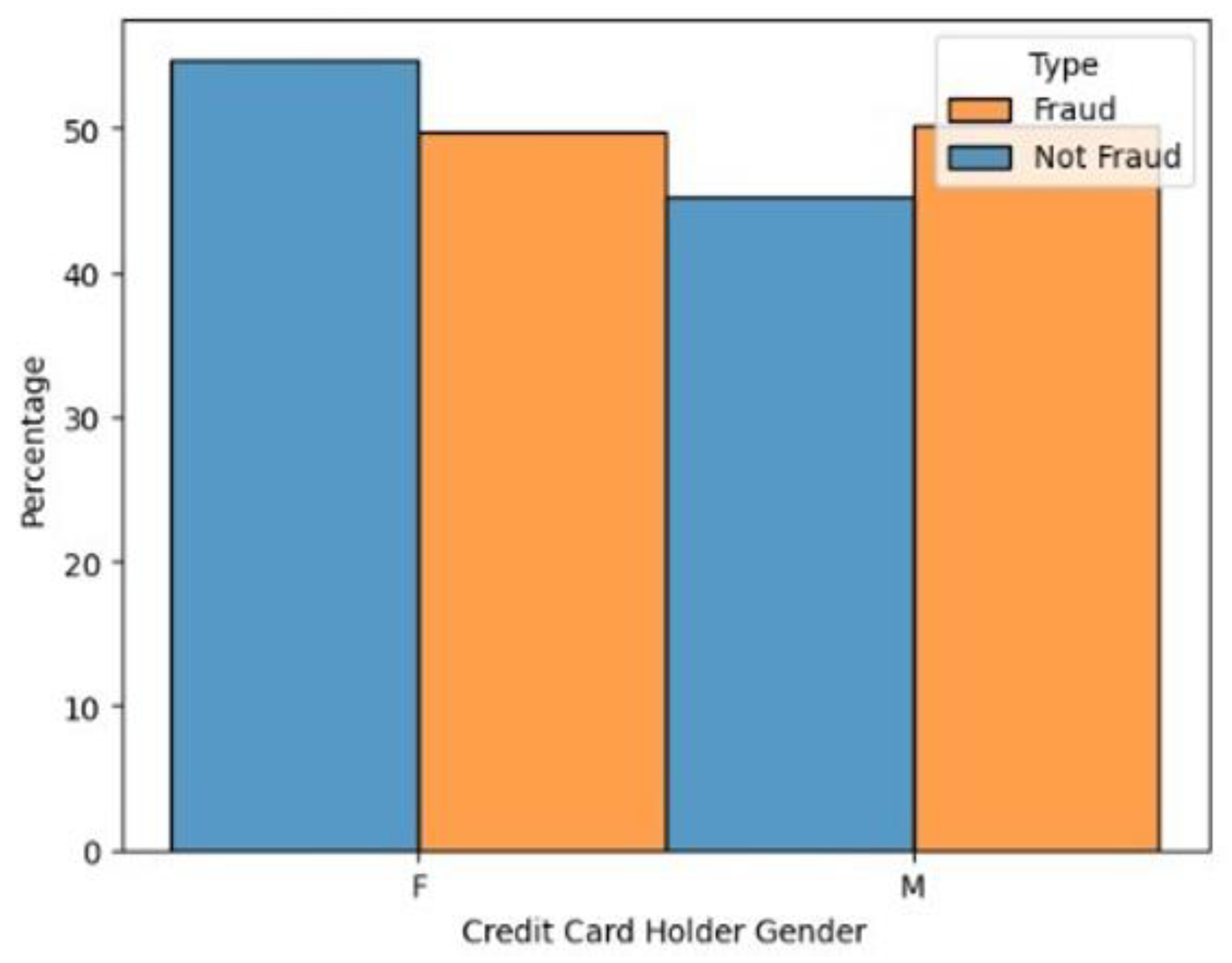

Gender and Fraud

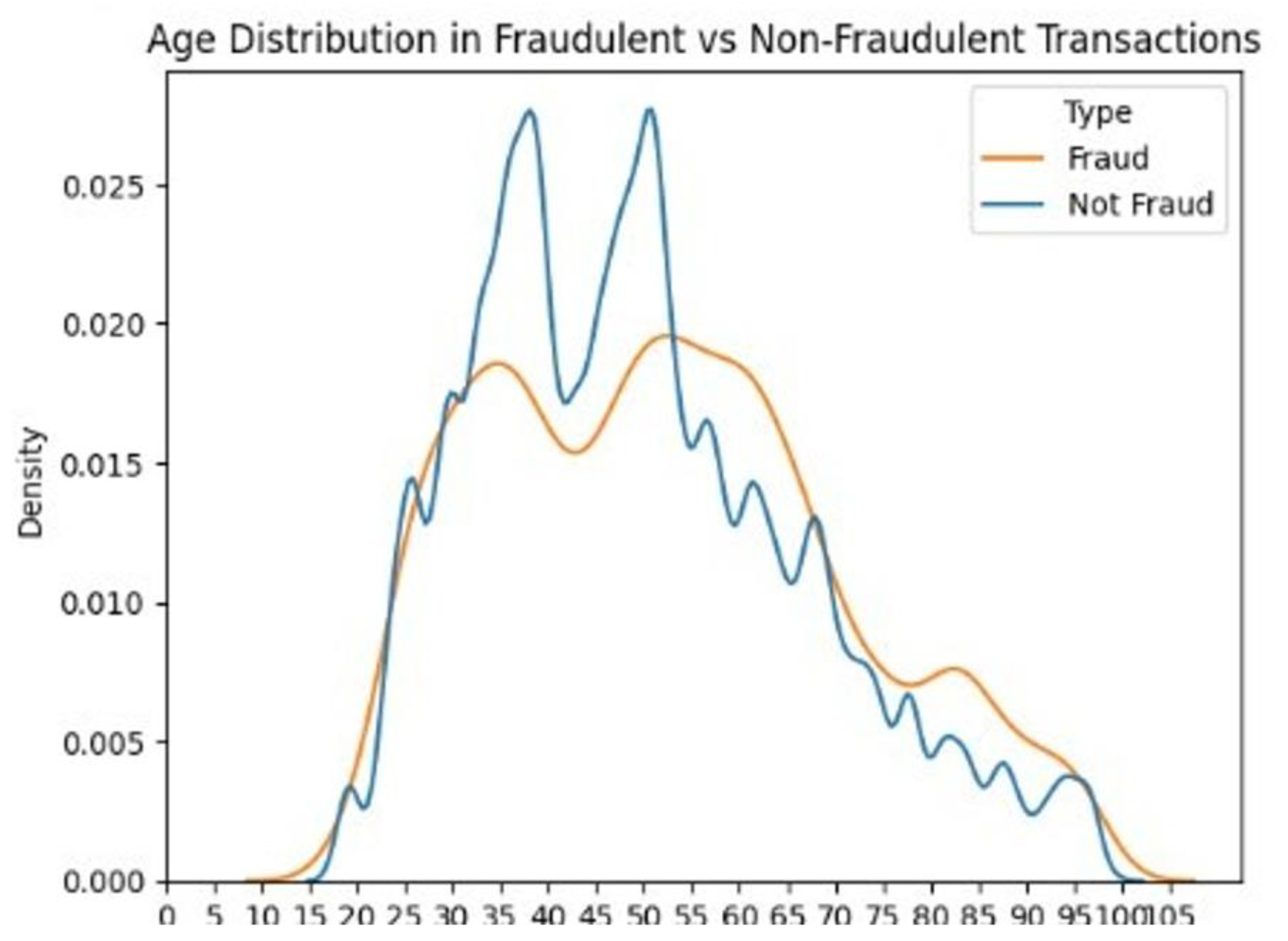

Age and Fraud

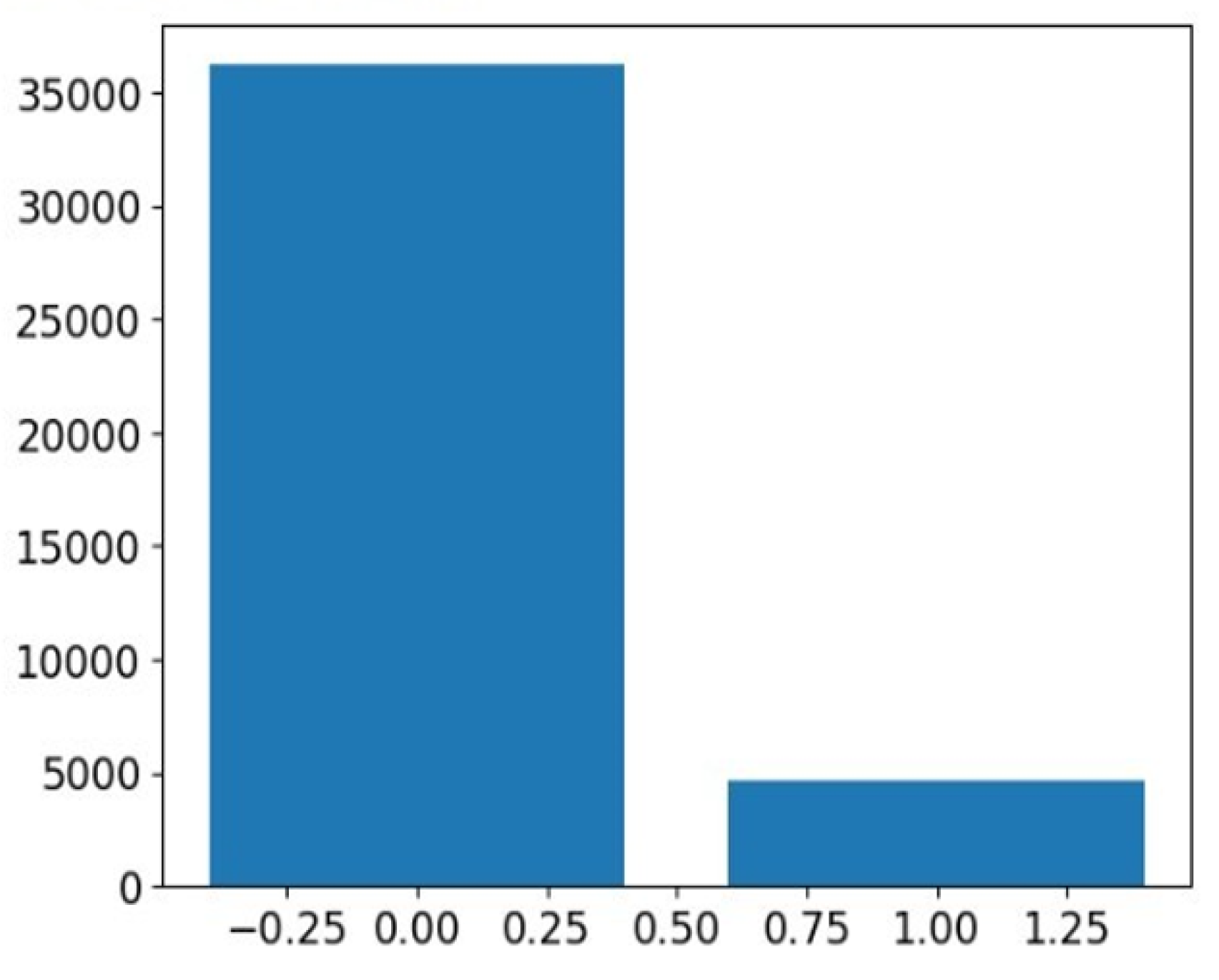

4.2.3. Data Balancing

4.2.4. Data Conversion

4.2.5. Model Implementation

4.2.6. Training Parameters

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Model Conversion

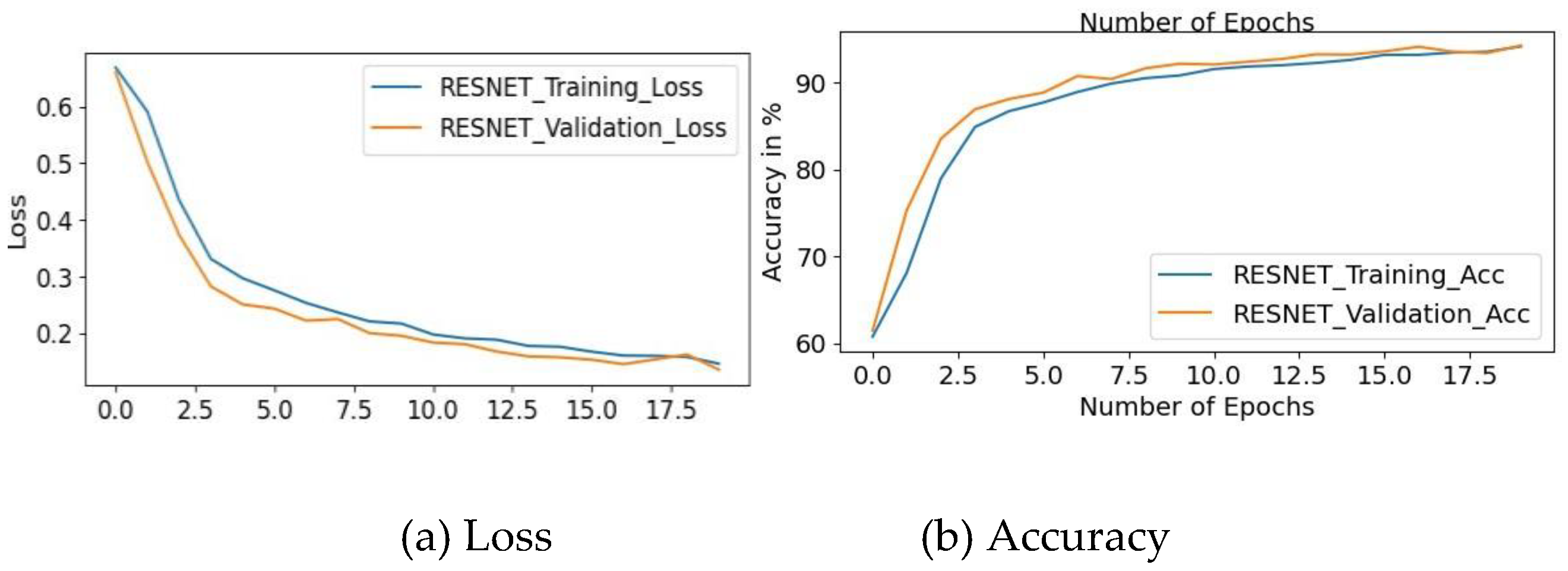

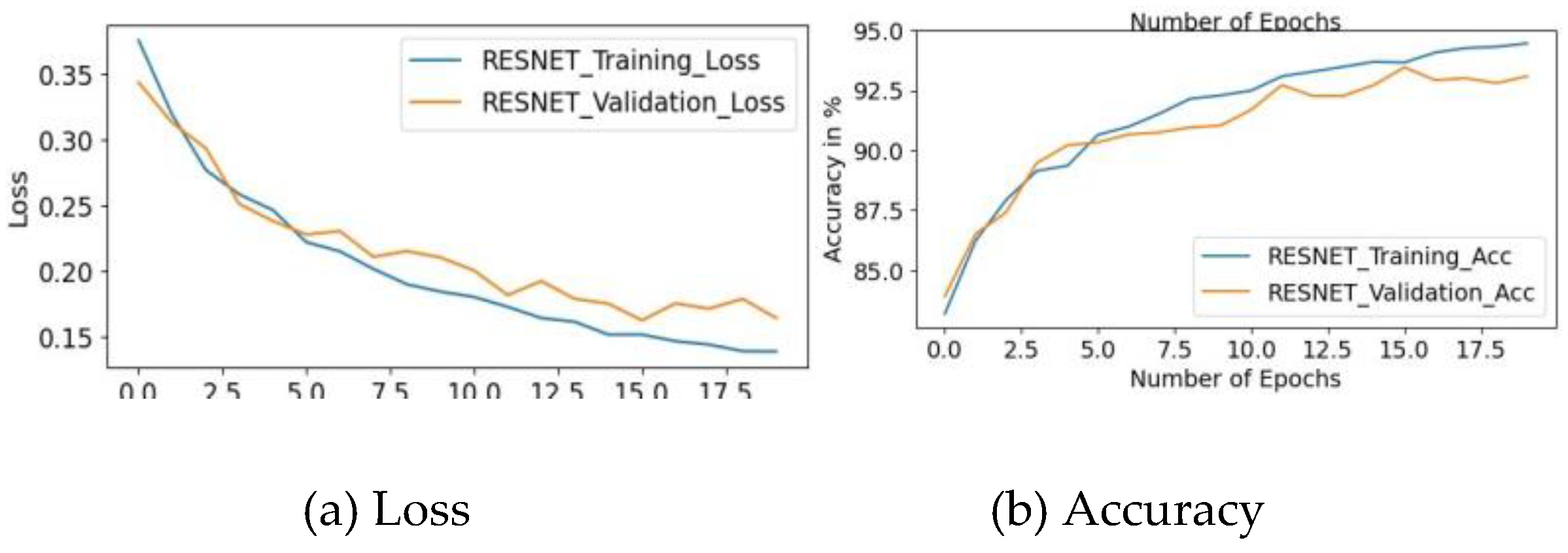

4.3.2. The Plot of Training and Testing Loss, Training and Testing Accuracy

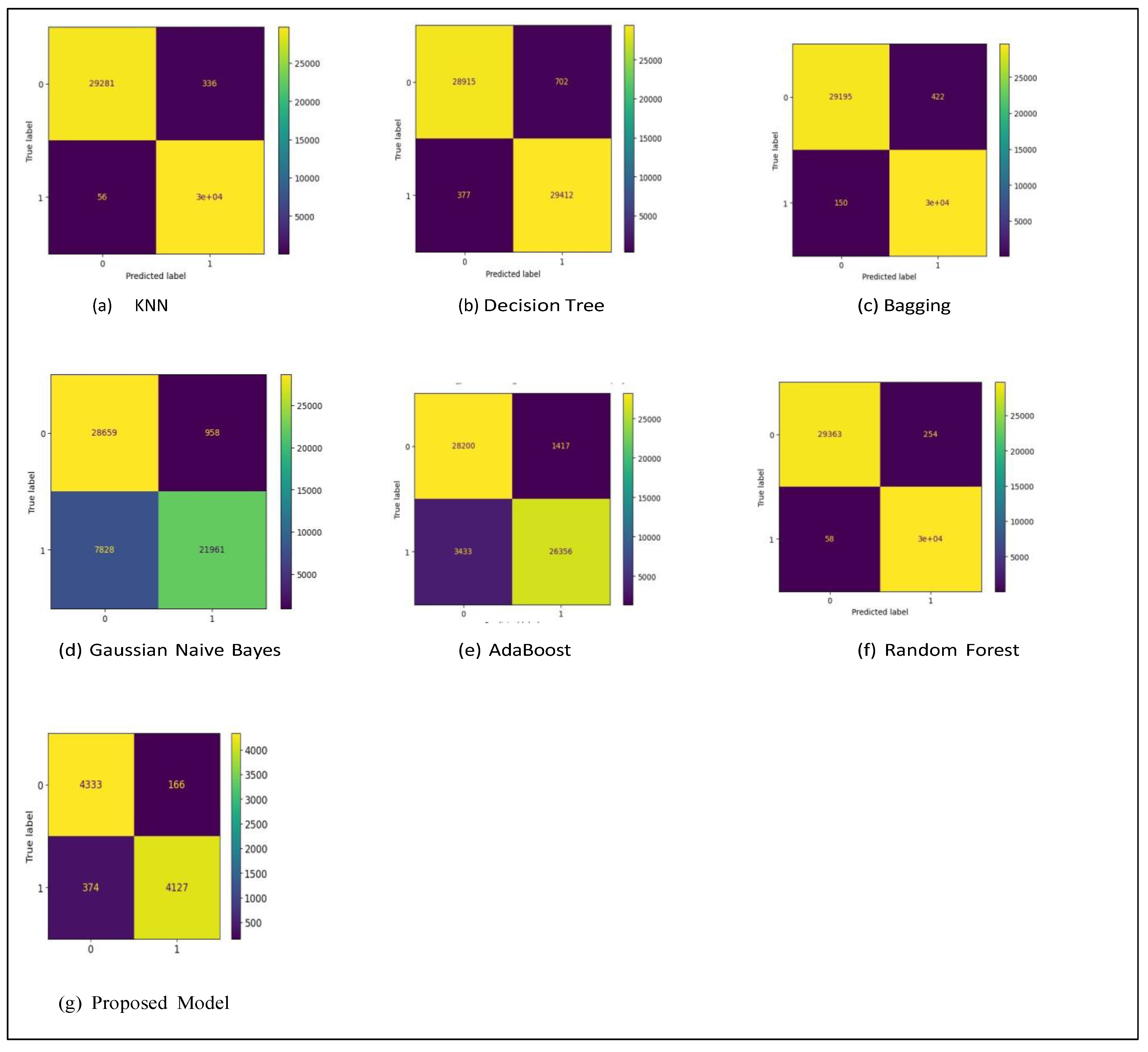

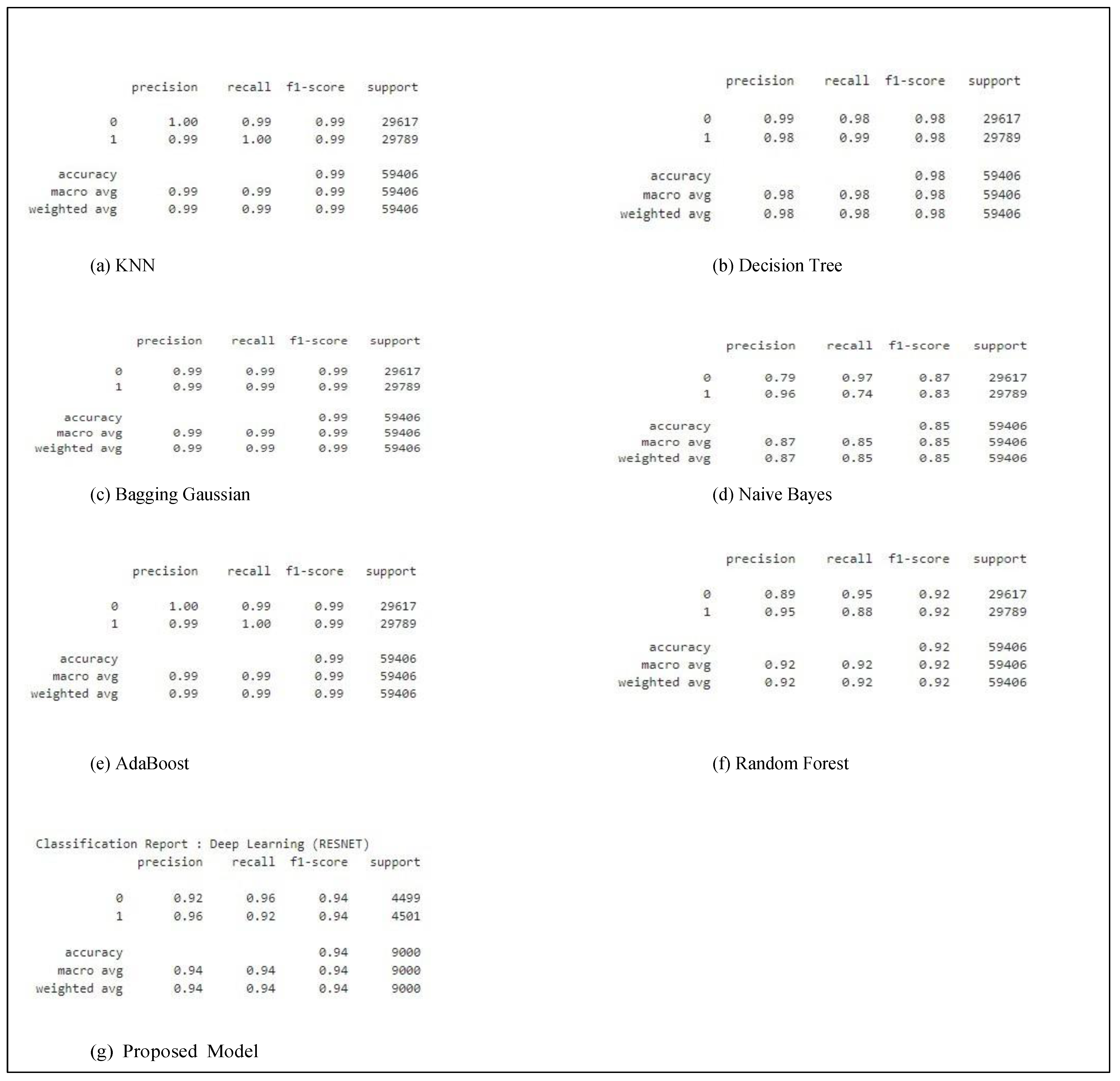

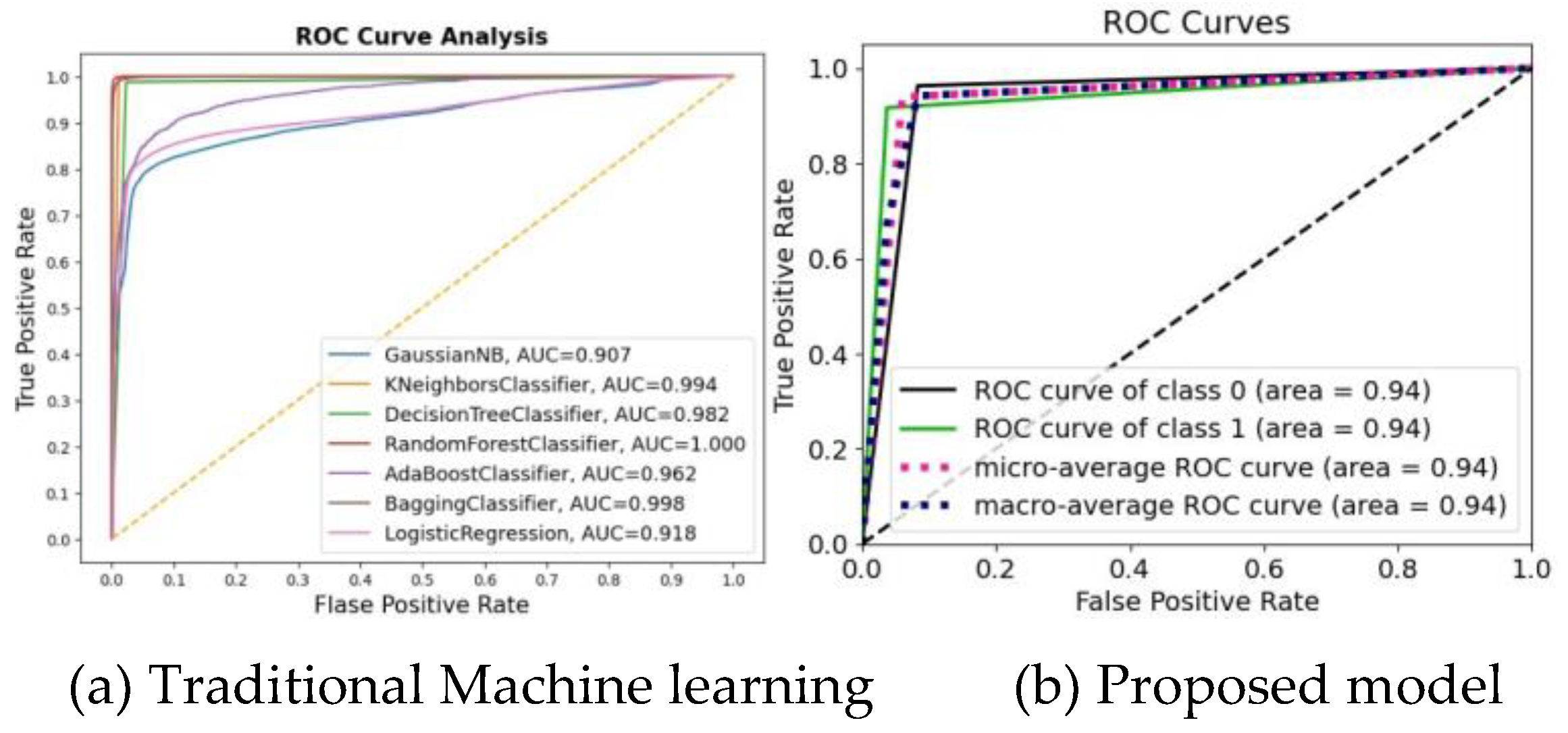

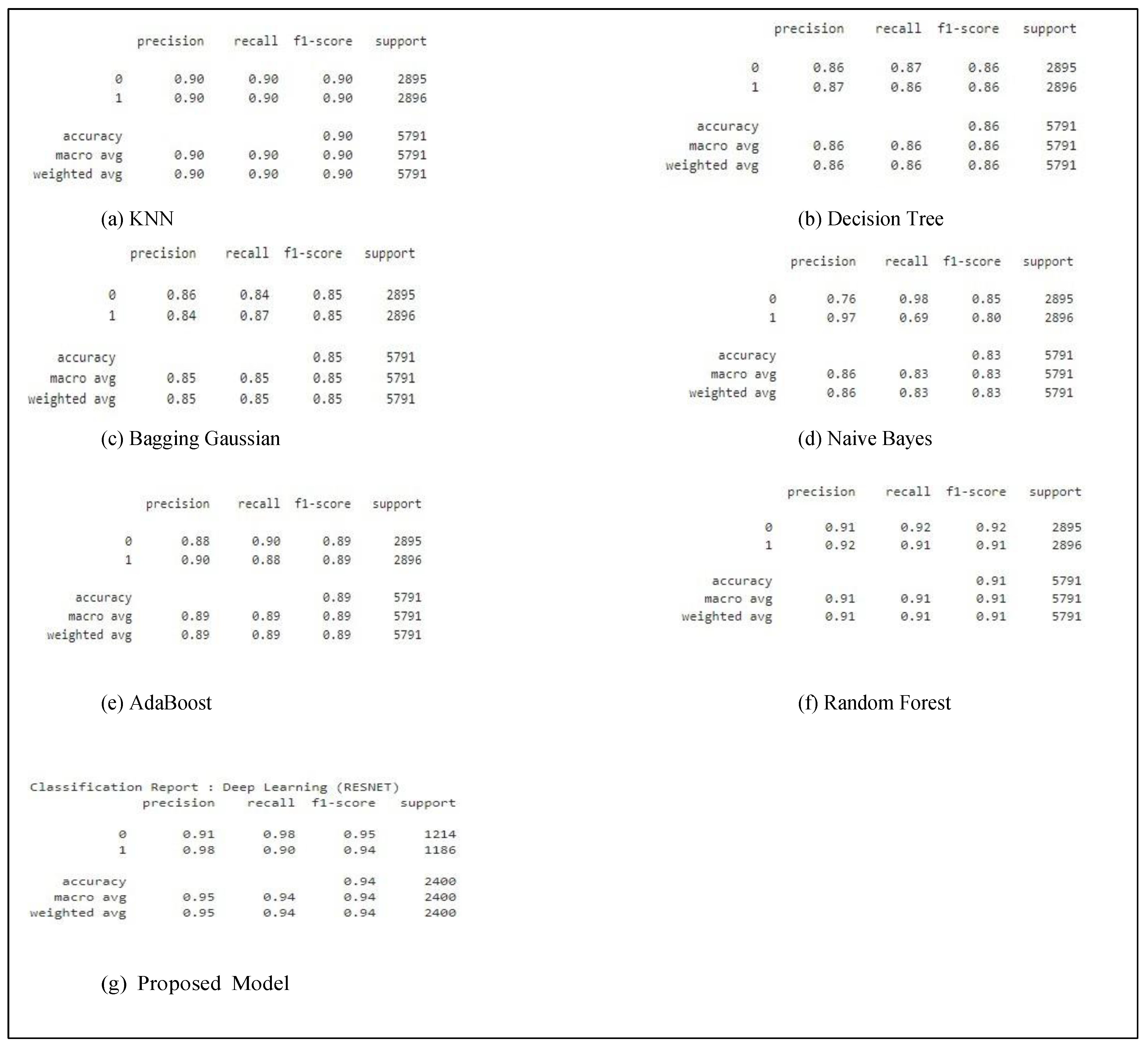

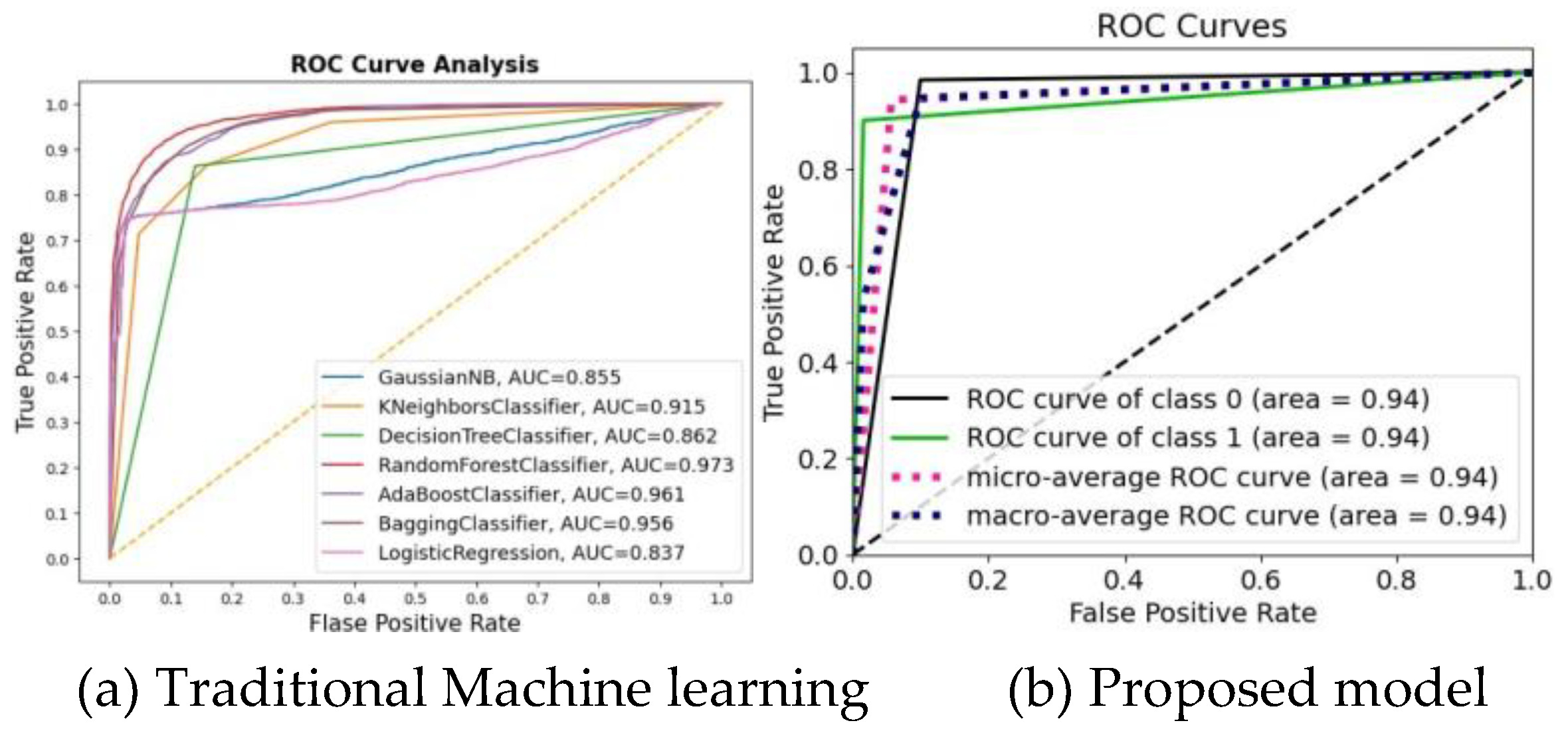

4.3.3. Model Comparison

Application of Over-Sampling Data Balancing Technique (SMOTE)

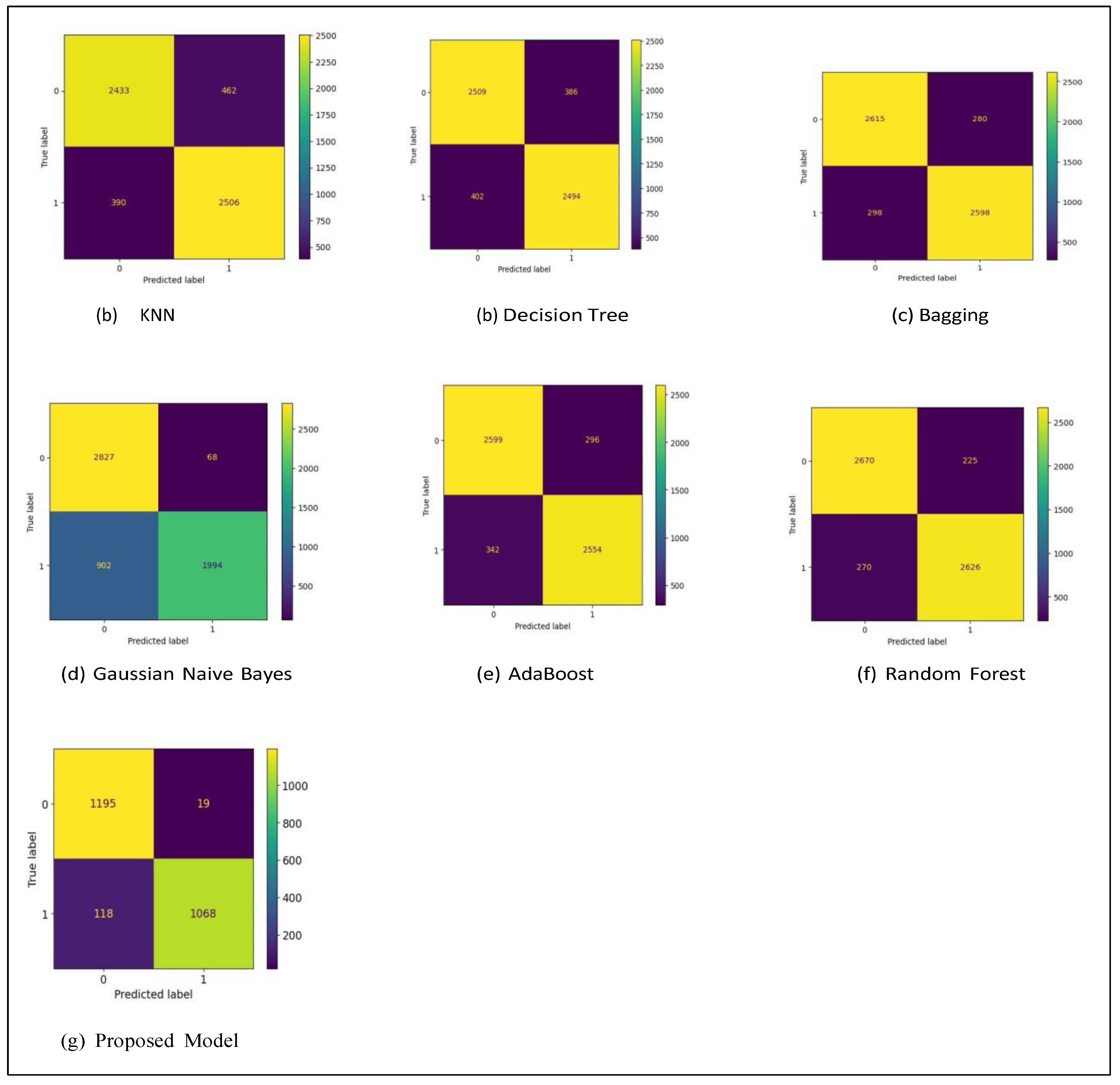

Application of Random Under-Sampling Data Balancing Technique

4.3.4. Discussion

4.3.5. Summary

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Recommendation

Appendix A. Feature Table

| S/no Features |

| 1. Transaction date and time |

| 2. ccnum |

| 3. Merchant |

| 4. Category |

| 5. Amount |

| 6. First name |

| 7. Last name |

| 8. Gender |

| 9. Street |

| 10. City |

| 11. State |

| 12. Zip |

| 13. Latitude |

| 14. Longitude |

| 15. City PoP |

| 16. Date of Birth |

| 17. Job |

| 18. Transaction number |

| 19. Unix Time |

| 20. Merchant latitude |

| 21. Merchant longitude |

| 22. Class |

References

- R. J. Sullivan, “The changing nature of us card payment fraud: Issues for industry and public policy.” in WEIS, 2010.

- V. I. Dewi, “Perkembangan sistem pembayaran di indonesia,” Bina Ekonomi, vol. 10, no. 2, 2006.

- B. Scholnick, N. Massoud, A. Saunders, S. Carbo-Valverde, and F. Rodriguez-Fernandez, “The economics of credit cards, debit cards and atms: A survey and some new evidence,” Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1468–1483, 2008.

- N. Saraswati and I. Mukhlis, “The influence of debit card, credit card, and e-money transactions toward currency demand in indonesia,” Quantitative Economics Research, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 87–94, 2018.

- J. B-lach, “Financial innovations and their role in the modern financial system-identification and systematization of the problem,” e-Finanse: Financial Internet Quarterly, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 13–26, 2011.

- L. P. L. Cavaliere, N. Subhash, P. V. D. Rao, P. Mittal, K. Koti, M. K. Chakravarthi, R. Duraipandian, S. S. Rajest, and R. Regin, “The impact of internet fraud on financial performance of banks,” Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 8126–8158, 2021.

- K. Vengatesan, A. Kumar, S. Yuvraj, V. Kumar, and S. Sabnis, “Credit card fraud detection using data analytic techniques,” Advances in Mathematics: Scientific Journal, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1185–1196, 2020.

- S. Bhattacharyya, S. Jha, K. Tharakunnel, and J. C. Westland, “Data mining for credit card fraud: A comparative study,” Decision support systems, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 602–613, 2011.

- CyberSource, “Cybersource. online fraud report: online payment, fraud trends, merchant practices, and bench marks, ”accessed: 2023-08-01. [Online]. Available: http://cybersource.

- C. Everett, “Credit card fraud funds terrorism,” Computer Fraud & Security, vol. 2003, no. 5, p. 1, 2003.

- L. Delamaire, H. Abdou, and J. Pointon, “Credit card fraud and detection techniques: a review,” Banks and Bank systems, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 57–68, 2009.

- K. Chaudhary, J. Yadav, and B. Mallick, “A review of fraud detection techniques: Credit card,” International Journal of Computer Applications, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 39–44, 2012.

- R. Anderson, The credit scoring toolkit: theory and practice for retail credit risk management and decision automation. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- B. Mahesh, “Machine learning algorithms-a review,” International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR).[Internet], vol. 9, pp. 381–386, 2020.

- G., Y. B., and A. Courville, “Deep learning,” 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.deeplearningbook.

- D. Luvizon, “Machine learning for human action recognition and pose estimation based on 3d information,” Ph.D. dissertation, Cergy Paris Universit´e, 2019.

- Dal Pozzolo, G. Boracchi, O. Caelen, C. Alippi, and G. Bontempi, “Credit card fraud detection: a realistic modeling and a novel learning strategy,” IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, vol. 29, no. 8, pp. 3784–3797, 2017.

- T. Verdonck, B. Baesens, M. O´skarsd´ottir et al., “Special issue on feature engineering editorial,” Machine Learning, pp. 1–12, 2021.

- S. Sumanjeet, “Emergence of payment systems in the age of electronic commerce: The state of art,” Global Journal of International Business Research, vol. 2, no. 2, 2009.

- D. S. Evans and R. Schmalensee, Paying with plastic: the digital revolution in buying and borrowing. Mit Press, 2004.

- R. Hunt, “The development and regulation of consumer credit reporting in america federal reserve bank of philadelphia,” 2002.

- R. M. Hunt, “An introduction to the economics of payment card networks,”.

- Review of Network Economics, vol. 2, no. 2, 2003.

- T. Ekici and L. Dunn, “Credit card debt and consumption: evidence from household-level data,” Applied Economics, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 455–462, 2010.

- B. C. S. D. A. W. L. A. S. Florentin Butaru, Qingqing Chen, “Risk and risk management in the credit card industry,” Journal of Banking Finance, vol. 72, pp. 218–239, 2016.

- J. P. Caskey, G. H. Sellon et al., “Is the debit card revolution finally here?” Economic Review-Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, vol. 79, pp. 79–79, 1994.

- J. W. Prathaban Mookiah, Ian Holmes and T. O. Connell, “A real-time solution for application fraud prevention,” 2019.

- Y. Tong, W. Lu, Y. Yu, and Y. Shen, “Application of machine learning in ophthalmic imaging modalities,” Eye and Vision, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2020.

- E. Burns, “What is artificial intelligent ai,” accessed: 2023-2002. [Online]. Available: https://www.techtarget.

- S. Mishra, “towards data science, ”accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://towardsdatascience.

- M. M. El Naqa, I., “Machine learning in radiation oncology,” vol. 9, pp. 3–11, 2015.

- L. A. Zadeh, “Fuzzy logic,” Computer, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 83–93, 1988.

- J. Laaksonen and E. Oja, “Classification with learning k-nearest neighbors,” in Proceedings of international conference on neural networks (ICNN’96), vol. 3. IEEE, 1996, pp. 1480–1483.

- W. S. Noble, “What is a support vector machine?” Nature biotechnology, vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 1565–1567, 2006.

- IBM, “What is deep learning,” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.

- Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning,” nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, pp. 436–444, 2015.

- P. Kim, “Convolutional neural network,” in MATLAB deep learning. Springer, 2017, pp. 121–147.

- IBM, “Neural network,” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://www.sas.com/en us/insights/analytics/neural-networks.

- SAS, “Neural networks: What they are and why they atter,,” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://www.sas.com/en us/insights/ analytics/neural-networks.

- S.-C. Wang, Interdisciplinary computing in Java programming. Springer Science & Business Media, 2003, vol. 743.

- Neutelings, “Neural networks.” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://tikz.

- V. Puncreobutr, “Education 4.0: New challenge of learning,” Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 2, 2016.

- D. Rengasamy, M. Jafari, B. Rothwell, X. Chen, and G. P. Figueredo, “Deep learning with dynamically weighted loss function for sensor-based prognostics and health management,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 3, p. 723, Jan 2020. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- J. Gu, Z. Wang, J. Kuen, L. Ma, A. Shahroudy, B. Shuai, T. Liu, X. Wang, G. Wang, J. Cai et al., “Recent advances in convolutional neural networks,” Pattern recognition, vol. 77, pp. 354–377, 2018.

- R. Yamashita, M. Nishio, R. K. G. Do, and K. Togashi, “Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology,” Insights into imaging, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 611–629, 2018.

- S. Albawi, O. Bayat, S. Al-Azawi, and O. N. Ucan, “Social touch gesture recognition using convolutional neural network,” Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, vol. 2018, 2017.

- Mehta, “A comprehensive guide to types of neural networks,” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://www.digitalvidya.com/ blog/types-of-neuralnetworks.

- IBM, “Convolutional neural networks.” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.

- C.-C. Lo, C.-H. Lee, and W.-C. Huang, “Prognosis of bearing and gear wears using convolutional neural network with hybrid loss function,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 12, p. 3539, Jun 2020. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- IBM, “Convolutional neural network, ”accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.com/cloud/learn/ convolutional-neuralnetworks.

- A. A. and S. Amidi, “Covolutional neural nets,” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://stanford.edu/∼shervine/teaching/cs-230/cheatsheetconvolutional-neural-networks.

- S.Saha, “A comprehensive guide to convolutional neural networks — the eli5 way,’ towards data science,” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://towardsdatascience.com/a-comprehensive-guide-to-convolutional-neural-networks-the-eli5-way-3bd2b1164a53.

- J. Brownlee, “How to choose an activation function for deep learning,” accessed: 2023-20-02. [Online]. Available: https://machinelearningmastery. com/choose-an-activation-function-for-deeplearning/.

- K. Philip and S. Chan, “Toward scalable learning with non-uniform class and cost distributions: A case study in credit card fraud detection,” in Proceeding of the Fourth International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 1998, pp. 164–168.

- D. Iyer, A. Mohanpurkar, S. Janardhan, D. Rathod, and A. Sardeshmukh, “Credit card fraud detection using hidden markov model,” in 2011 World Congress on Information and Communication Technologies. IEEE, 2011, pp. 1062–1066.

- R. Patidar, L. Sharma et al., “Credit card fraud detection using neural network,” International Journal of soft computing and Engineering (IJSCE), vol. 1, no. 32-38, 2011.

- M. R. HaratiNik, M. Akrami, S. Khadivi, and M. Shajari, “Fuzzgy: A hybrid model for credit card fraud detection,” in 6th international symposium on telecommunications (IST). IEEE, 2012, pp. 1088–1093.

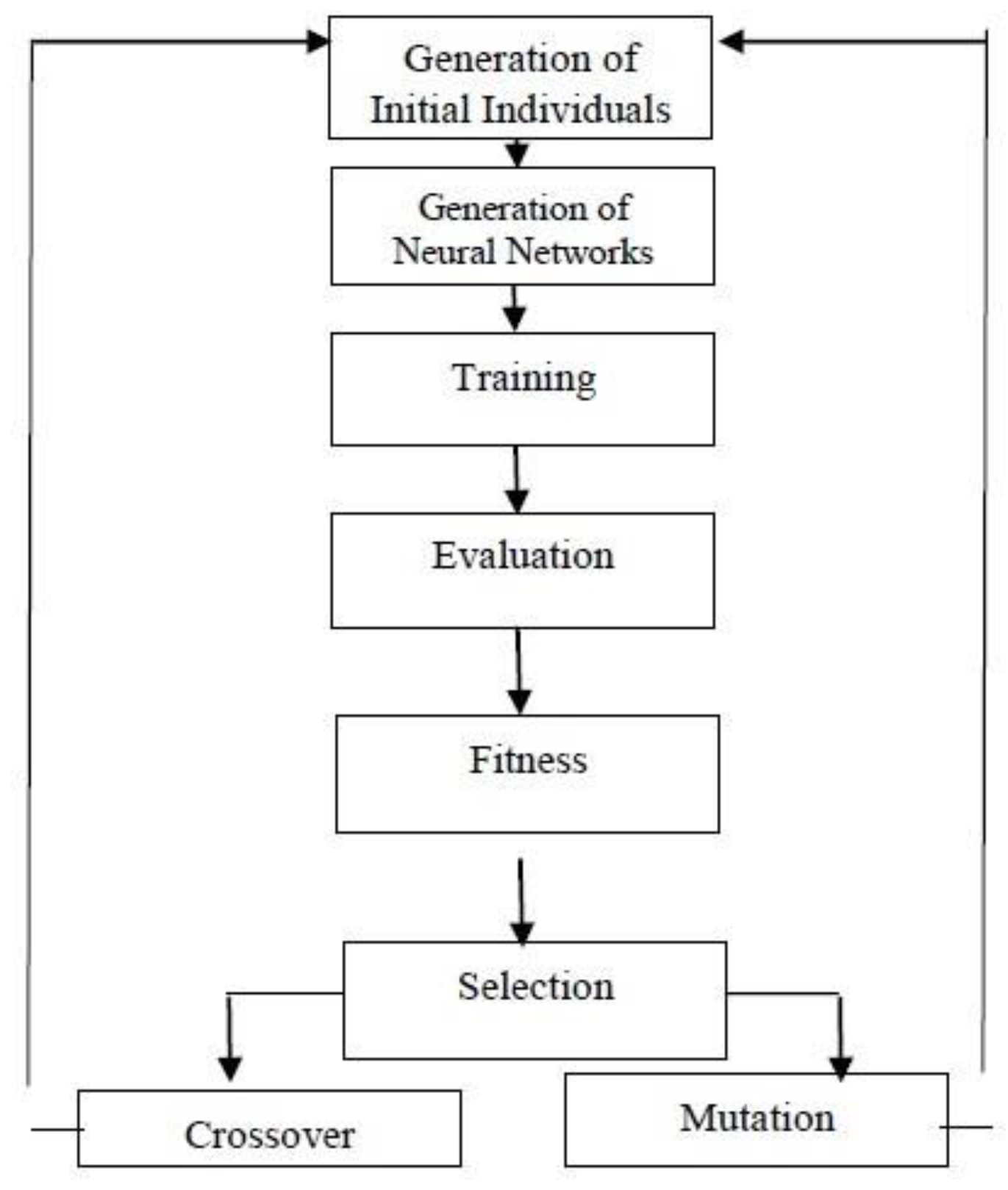

- R. D. Patel and D. K. Singh, “Credit card fraud detection & prevention of fraud using genetic algorithm,” International Journal of Soft Computing and Engineering, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 292–294, 2013.

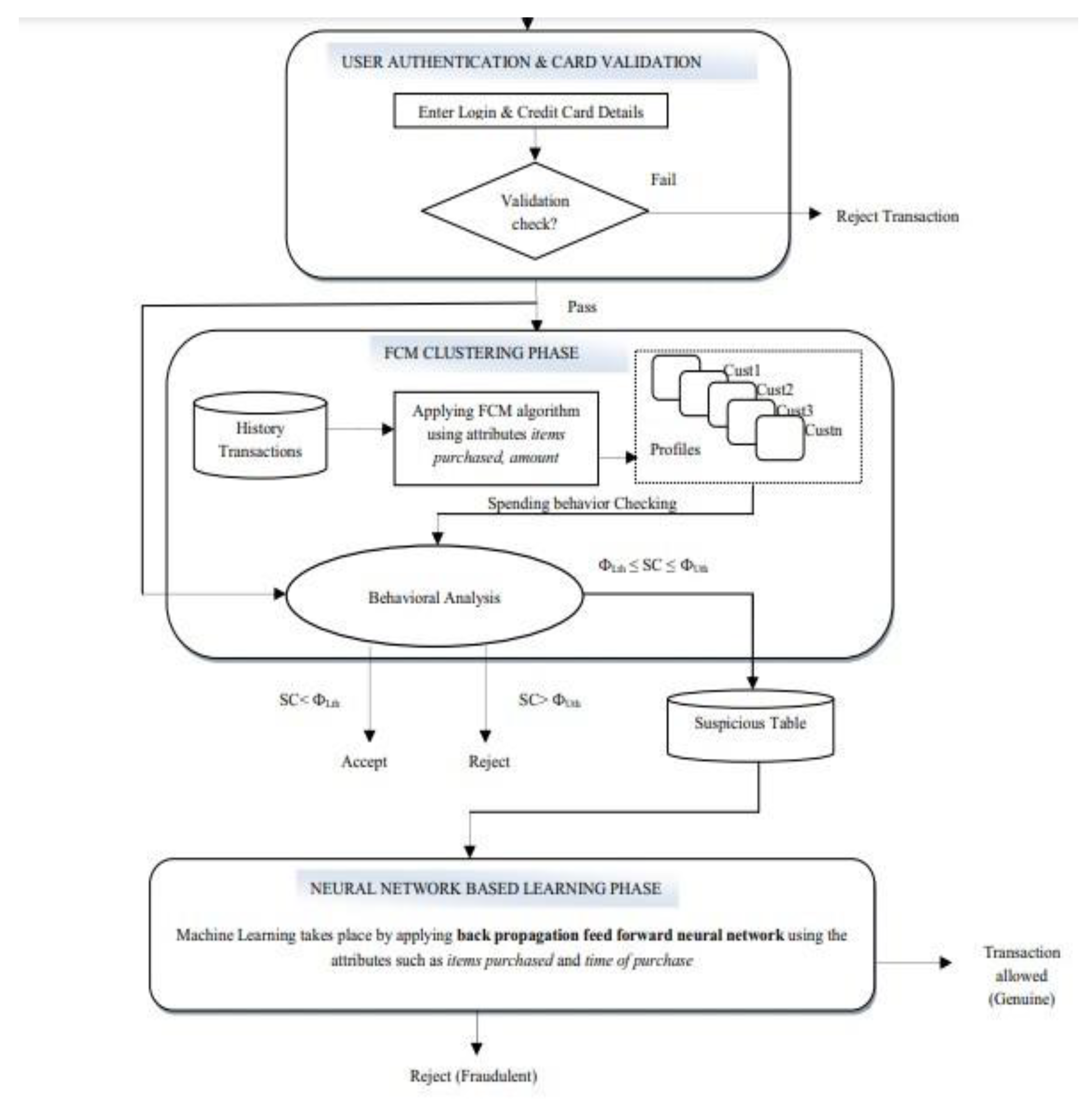

- T. K. Behera and S. Panigrahi, “Credit card fraud detection: a hybrid approach using fuzzy clustering & neural network,” in 2015 second international conference on advances in computing and communication engineering. IEEE, 2015, pp. 494–499.

- Dal Pozzolo, “Adaptive machine learning for credit card fraud detection,” 2015.

- Y. Heryadi, L. A. Wulandhari, B. S. Abbas et al., “Recognizing debit card fraud transaction using chaid and k-nearest neighbor: Indonesian bank case,” in 2016 11th International Conference on Knowledge, Information and Creativity Support Systems (KICSS). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–5.

- N. Carneiro, G. Figueira, and M. Costa, “A data mining based system for credit-card fraud detection in e-tail,” Decision Support Systems, vol. 95, pp. 91–101, 2017.

- K. Goswami, Y. Park, and C. Song, “Impact of reviewer social interaction on online consumer review fraud detection,” Journal of Big Data, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–19, 2017.

- N. K. Gyamfi and J.-D. Abdulai, “Bank fraud detection using support vector machine,” in 2018 IEEE 9th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON). IEEE, 2018, pp. 37–41.

- W. N. Robinson and A. Aria, “Sequential fraud detection for prepaid cards using hidden markov model divergence,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 91, pp. 235–251, 2018.

- E.-H. A. Abdou, H. E. Mohammed, W. Khalifa, M. I. Roushdy, and A.-B. M. Salem, “Machine learning techniques for credit card fraud detection,”Future Computing and Informatics Journal, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 5, 2019.

- U. Fiore, A. De Santis, F. Perla, P. Zanetti, and F. Palmieri, “Using generative adversarial networks for improving classification effectiveness in credit card fraud detection,” Information Sciences, vol. 479, pp. 448–455, 2019.

- S. Georgieva, M. Markova, and V. Pavlov, “Using neural network for credit card fraud detection,” in AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 2159, no. 1. AIP Publishing LLC, 2019, p. 030013.

- B. Branco, P. Abreu, A. S. Gomes, M. S. Almeida, J. T. Ascens˜ao, and P. Bizarro, “Interleaved sequence rnns for fraud detection,” in Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 2020, pp. 3101–3109.

- S. M. Darwish, “An intelligent credit card fraud detection approach based on semantic fusion of two classifiers,” Soft Computing, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 1243–1253, 2020.

- S. Khatri, A. Arora, and A. P. Agrawal, “Supervised machine learning algorithms for credit card fraud detection: a comparison,” in 2020 10th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence). IEEE, 2020, pp. 680–683.

- M. Seera, C. P. Lim, A. Kumar, L. Dhamotharan, and K. H. Tan, “An intelligent payment card fraud detection system,” Annals of operations research, pp. 1–23, 2021.

- X. Zhang, Y. Han, W. Xu, and Q. Wang, “Hoba: A novel feature engineering methodology for credit card fraud detection with a deep learning architecture,” Information Sciences, vol. 557, pp. 302–316, 2021.

- V. Chang, A. Di Stefano, Z. Sun, G. Fortino et al., “Digital payment fraud detection methods in digital ages and industry 4.0,” Computers and Electrical Engineering, vol. 100, p. 107734, 2022.

- J. Forough and S. Momtazi, “Sequential credit card fraud detection: A joint deep neural network and probabilistic graphical model approach,” Expert Systems, vol. 39, no. 1, p. e12795, 2022.

- S. Kumar, R. Ahmed, S. Bharany, M. Shuaib, T. Ahmad, E. Tag Eldin, A. U. Rehman, and M. Shafiq, “Exploitation of machine learning algorithms for detecting financial crimes based on customers’ behavior,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 21, p. 13875, 2022.

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385.

| Model | Accuracy % | Precision % | Recall % | F1 score % |

| KNN | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| Decision Tree | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| Random Forest | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| Adaboost | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| Bagging | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| GaussianNB | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 0.83 |

| Proposed Model | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.94 |

| Model | Accuracy % | Precision % | Recall % | F1 score % |

| KNN | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Decision Tree | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Random Forest | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| Adaboost | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| Bagging | 0.90 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| GaussianNB | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 0.83 |

| Proposed Model | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).