Introduction

The prevalence and recurrence of nephrolithiasis and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), place a growing burden on patients, significantly impacting their quality of life [

1,

2]. This escalating challenge is compounded by the lack of accessible and comprehensible patient education, leaving many patients inadequately informed about their health conditions. As a result, healthcare institutions are increasingly expected to adopt a more patient-centered approach when implementing quality improvement measures, ensuring that patients’ needs and perspectives are prioritized [

3,

4]. However, current literature disproportionately overlooks patients from ethnic minority groups and those with low health literacy, further exacerbating existing health disparities and limiting equitable access to care [

5,

6].

Prior investigations employing race-conscious analysis tools demonstrated that disparities persist for conditions like BPH and kidney stones due to resources and infrastructure that may not adequately accommodate the needs of marginalized patient populations [

7,

8,

9]. Shared decision-making requires that patients understand their disease process and management options to make an informed medical decision. This requires patient understanding of their disease and management options. Ineffective communication may lead to increased levels of provider mistrust among these populations, ultimately resulting in lower patient satisfaction ratings compared to the White majority [

10,

11,

12].

The purpose of this pilot study is to analyze how patient satisfaction scores relating to BPH and kidney stones are affected when health resources are designed from an inclusive and equitable approach at a safety-net hospital. Research shows a positive correlation between patient satisfaction and the use of patient education interventions. Patient education materials have been shown to effectively support patients after their visit by providing an easy-to-follow template of actionable steps necessary to improve their health, especially materials that explain medical concepts concisely and in the patient’s preferred language [

13].

However, many educational materials surpass the recommended 6th-grade reading level and often lack visual aids crucial for improving comprehension [

14]. Despite their potential impact, few studies have investigated the effectiveness of educational handouts in addressing urological conditions such as BPH and nephrolithiasis, especially within Spanish-speaking and immigrant populations. In this study, we hypothesize that offering tailored, visually enhanced materials during medical appointments will improve patient satisfaction.

Methods

Preliminary

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained for this pilot study. Two educational handouts each were developed to address benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and kidney stones, focusing on the management and treatment of each condition. The documents were created in English and then translated into Spanish using Google Translate. The reliability of the translation was assessed using native Spanish speakers. Readability was continuously assessed using the Automated Readability Index tool to ensure the content met the 6th-grade reading level standard. Relevant illustrations were sourced from Google Images and incorporated to complement and enhance the written content. A board-certified and fellowship-trained endourologist reviewed the finalized handouts for accuracy and effectiveness before patient administration.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants in this study were selected based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible participants were adult patients (age ≥18 years) enrolled at the Urology Clinic at Olive View Medical Center. Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years old or experiencing severe emotional or physical pain during their visit, as these conditions could impact their ability to engage with the study materials.

Study Design

This study employed a quasi-experimental design. Eligible patients whose primary appointment reason was for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or kidney stone disease (KSD) were assigned to the intervention group, while patients presenting with other urological conditions formed the control group. The intervention group received educational handouts tailored to their medical condition and language preference, while the control group received standard care without supplemental educational materials.

Enrollment and Consent

Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were randomly selected to participate in the study. Per our institution’s IRB guidelines, written consent was not required for this study. Instead, verbal consent was obtained at the time of check-in for their appointment.

Patient Education Materials

At the end of their visit, patients in the intervention group received educational materials tailored to their condition (BPH or kidney stones) and preferred language (English or Spanish). Patients were asked to review the materials in the waiting room before leaving the clinic, ensuring they had an opportunity to ask any questions regarding the content. Control group patients proceeded with their standard post-appointment process without receiving the educational handouts.

Data Collection

All study participants were given the Urology SWOPS Questionnaire, a patient satisfaction survey designed to assess their understanding and experience. The questionnaire included 13 questions in total which included 12 multiple-choice questions and 1 open-ended question (see attached questionnaire).

Additionally, a randomly selected subset of patients from the intervention group was given a modified version of the SWOPS questionnaire that included an additional question (#14) to specifically assess the helpfulness of the educational handout.

All responses were collected and entered into an Excel spreadsheet for data organization and analysis over two months.

Results

A total of 128 participants were included in this study. The distribution of participants across groups showed a larger proportion of patients in the intervention group, n=102, (patients with BPH or KSD who received educational materials) compared to the control group, n=26, (patients with other urological conditions who did not receive educational materials). The subpopulation group had a total of 36 participants that were randomly selected from the intervention group.

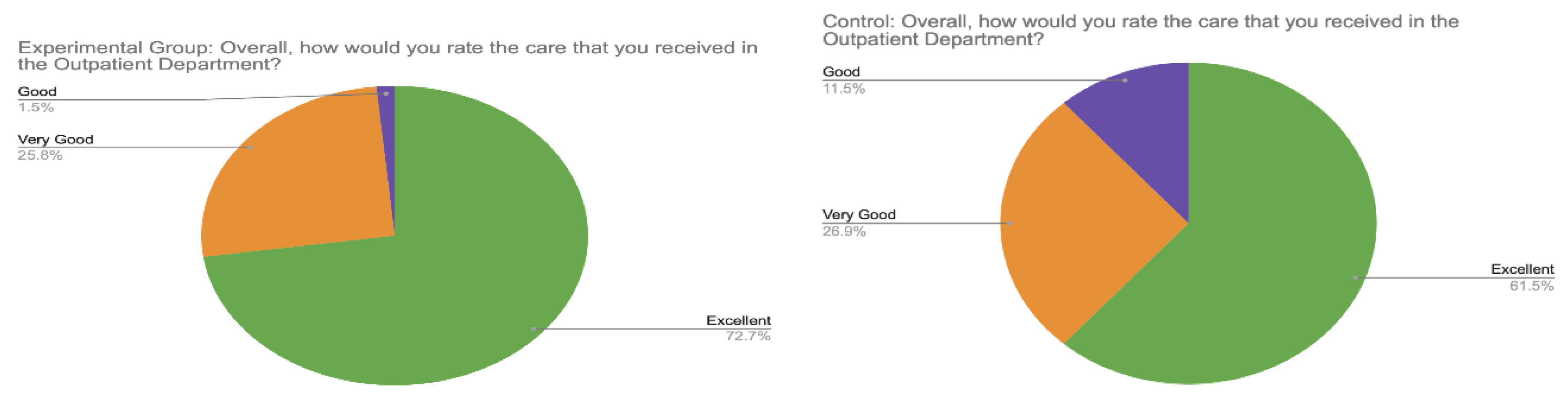

When rating overall care (Question #9), 48 participants (73%) in the intervention group described it as “Excellent” compared to 16 participants (62%) in the control group. In the intervention group, 17 participants (26%) rated their care as “Very Good” compared to 7 participants (27%) in the control group. Only 1 participant (1%) in the intervention group rated their care as “Good,” compared to 3 participants (11%) in the control group. No participants in either group rated their care as “Fair,” “Poor,” or “Very Poor” (

Figure 1).

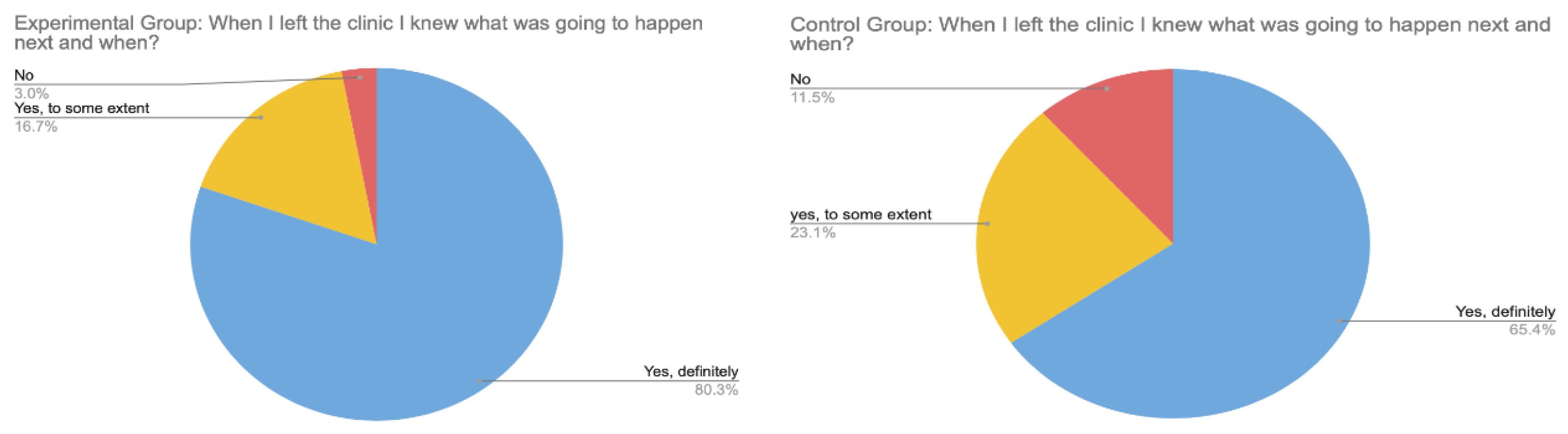

Regarding understanding their next care steps (Question #11), 53 participants (80%) in the intervention group responded “Yes, definitely” compared to 17 participants (65%) in the control group. In the intervention group, 11 participants (17%) responded “Yes, to some extent” compared to 6 participants (23%) in the control group. Only 2 participants (3%) in the intervention group responded “No” compared to 3 participants (12%) in the control group (

Figure 2).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test to compare patient satisfaction outcomes between the intervention group (n=102) who received educational materials and the control group (n=26) who received standard care. For overall care rating (Question #9), the intervention group reported significantly higher satisfaction levels compared to the control group (U=1578.0, p=0.025), with mean ratings of 4.71 and 4.50 respectively. The effect size was small (r=0.243), but clinically meaningful in the healthcare context. Similarly, patient understanding of next care steps (Question #11) was significantly better in the intervention group compared to controls (U=1610.0, p=0.013), with mean scores of 1.77 versus 1.54, and a small effect size (r=0.272).

Subpopulation Data

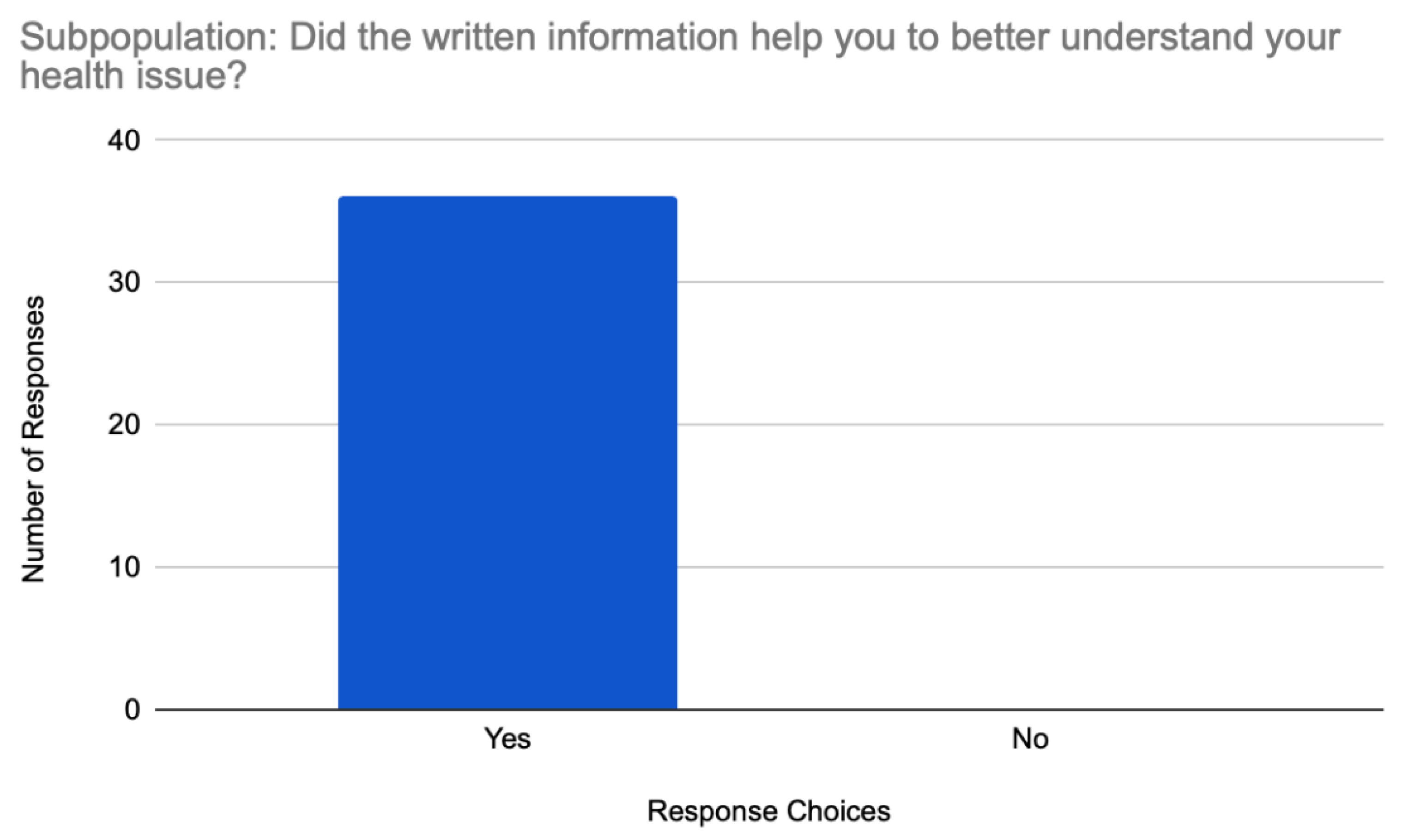

Among the subpopulation of the intervention group specifically asked whether the educational material was helpful in understanding their disease process (Question #14), all 36 participants (100%) responded “Yes” (

Figure 3). Additionally, the subpopulation group showed high satisfaction ratings, similar to the intervention group, with 24 participants (67%) rating their care as “Excellent” and 12 participants (33%) rating it as “Very Good.” When asked about understanding their next care steps, 29 participants (81%) responded “Yes, definitely” and 7 participants (19%) responded “Yes, to some extent,” with none responding “No.”

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that formal patient education leads to significantly higher patient satisfaction levels compared to standard care without supplemental educational materials. The significant difference in satisfaction scores between the intervention and control groups highlights the value of providing tailored educational handouts to patients with BPH and KSD.

The educational information distributed to our participants was created from a health-justice lens by investigating how improving health literacy and shared decision-making (SDM) affects patient satisfaction and the overall patient experience. In our clinic, responses from the intervention group showed that patients felt significantly better informed about the next steps of treatment and rated their overall care more favorably when provided with educational materials compared to those who received standard care alone.

Most striking was the unanimous response from the subpopulation group, where 100% of patients confirmed that the educational materials were helpful in understanding their disease process.

When examining the data more closely, we observe that while both groups generally reported positive experiences, the intervention group consistently showed higher satisfaction levels. For example, 73% of the intervention group rated their care as “Excellent” compared to 62% in the control group. Similarly, 80% of the intervention group definitely understood their next care steps compared to 65% in the control group. These results provided statistically significant evidence supporting the efficacy of language-appropriate educational materials in improving both patient satisfaction and comprehension. Despite the small effect sizes, these improvements represent meaningful enhancements in patient experience, particularly considering the simplicity and cost-effectiveness of the educational intervention. The Mann-Whitney U test was selected for the statistical analysis of the results due to the nature of the satisfaction survey data, which does not require assumptions about normal distribution that would be necessary for parametric testing [

15].

Patient satisfaction levels have been shown to improve when SDM is facilitated by caregivers and medical professionals [

16]. SDM has shown great promise in improving patient outcomes and continues to assist the transition from physician-centered medicine to patient-focused care [

17]. An often overlooked aspect of a patient-centric approach is the emphasis on empowering patients to actively participate in their medical decisions [

18,

19]. SDM involves a collaborative process in which clinicians present patients with the most reliable evidence available, guide them through their options, and support them in making informed choices that align with their personal preferences and values [

20]. When SDM is performed properly, patients and healthcare systems mutually benefit from experiencing greater clinical outcomes and lower health cost burdens [

21].

Improving patient satisfaction levels along with SDM can only occur if patients understand the medical information being shared and its impact. For this reason, this paper focused heavily on creating health education materials at a particular readability level. As recommended by the American Medical Association (AMA), health education materials should be made at a sixth-grade reading level or below [

14]. Even with this recommendation, prior studies have found that in certain medical specialties, much of the information available in patient educational handouts exceeds this sixth-grade reading level [

22]. As a consequence, high readability levels are correlated to lower health literacy and give rise to poor medical compliance, a higher likelihood of uncontrolled chronic disease, and higher medical costs for patients. The elderly population is most vulnerable to this issue surrounding high readability levels as they already suffer from the lowest rates of health literacy [

23]. Poorer health outcomes stemming from higher readability levels are also correlated with lower quality of care, less informed medical decision-making, and poor patient satisfaction levels [

24].

Research consistently demonstrates that patients with limited English proficiency experience lower satisfaction levels and face higher rates of adverse medical outcomes compared to their English-speaking counterparts [

25]. A possible contributing reason for these lower patient satisfaction levels for non-native English speakers is that most patient education resources are written in English even though millions of patients have a different primary language [

26]. This is why it was important to include the English and Spanish versions of all our written material in this study. Compared to English-language materials, Spanish-language comprehension resources in U.S. clinical settings have received far less attention, with significantly fewer studies examining the readability levels of Spanish health materials [

27]. Considering that nearly 70 million people in the U.S. have a primary language that is not English [

28], the purpose of this study was to emphasize the cultural and linguistic diversity of the U.S. patient population to garner attention to the importance of patient satisfaction for non-dominant ethnic patient groups.

Our finding that 100% of patients in the subpopulation analysis confirmed the educational handouts were helpful in understanding their disease process provides the strongest evidence for the value of these materials. This unanimous response suggests that patients not only appreciate these resources but find them genuinely beneficial for understanding their condition and treatment options. The positive response aligns with our hypothesis that tailored educational materials improve patient satisfaction and understanding.

This study has several limitations. First, group assignment was based on medical condition rather than randomization, which may introduce selection bias. Patients with BPH or KSD might inherently differ from those with other urological conditions in ways that could influence satisfaction ratings independently of the educational intervention. Second, the patient education materials were developed based on existing knowledge of BPH and kidney stones, incorporating key information deemed relevant to these conditions. The materials were then organized and refined by a single board-certified urologist, without a formalized review or structured development process. Third, when translating the English BPH and kidney stone educational materials to the Spanish versions, a certified language service was not used due to limited project funding. Nonetheless, translation was verified by native speakers before and after readability evaluations to ensure all information was reliable for Spanish-speaking patient participants.

Despite certain limitations, our study’s educational interventions led to successful outcomes with higher patient satisfaction scores compared to standard care practices. The unanimous positive response from the subpopulation regarding the helpfulness of educational materials provides particularly compelling evidence for the value of this intervention. While this study focused on the impact of written educational materials on patient satisfaction, future research should explore how video-based educational interventions empower patients. Since the rise in online video content popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, developing standardized video platforms has become increasingly relevant [

29]. Such platforms could provide tailored education at key points during medical appointments, enhancing patient understanding and engagement. By prioritizing thoughtful language choices and offering content in multiple languages, these videos could foster more effective shared decision-making and advance the goal of truly patient-centered care.

Conclusion

The study revealed a compelling correlation between patient satisfaction and educational materials for BPH and kidney stones, with intervention recipients consistently reporting significantly higher satisfaction than those receiving standard care alone. Notably, every patient questioned in the study found these materials helpful for understanding their condition, providing strong evidence that this simple, cost-effective intervention significantly enhances patient experience. These findings emphasize the value of incorporating targeted educational resources into routine clinical practice, as they foster a more informed patient population, facilitate effective shared decision-making, and potentially contribute to improved clinical outcomes and reduced healthcare burden.

Funding statement

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statement

Per our institution’s IRB guidelines, written consent was not required for this study. Instead, verbal consent was obtained at the time of check-in for each participant’s appointment.

Data Availability Statement

All data is publicly available. If any additional access to data that may not be included in the manuscript is requested, please email the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest/declarations

None

References

- Chughtai B, Rojanasarot S, Neeser K, Gultyaev D, Fu S, Bhattacharyya SK, El-Arabi AM, Cutone BJ, McVary KT. A comprehensive analysis of clinical, quality of life, and cost-effectiveness outcomes of key treatment options for benign prostatic hyperplasia. PLoS One. 2022 Apr 15;17(4):e0266824. PMID: 35427376; PMCID: PMC9012364. [CrossRef]

- Ziemba JB, Matlaga BR. Epidemiology and economics of nephrolithiasis. Investig Clin Urol. 2017 Sep;58(5):299-306. Epub 2017 Aug 10. PMID: 28868500; PMCID: PMC5577325. [CrossRef]

- Paterick TE, Patel N, Tajik AJ, Chandrasekaran K. Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2017 Jan;30(1):112-113. PMID: 28152110; PMCID: PMC5242136.

- Shahid, R., Shoker, M., Chu, L.M. et al. Impact of low health literacy on patients’ health outcomes: a multicenter cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 1148 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Van Den Eeden SK, Shan J, Jacobsen SJ, Aaronsen D, Haque R, Quinn VP, Quesenberry CP Jr; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Evaluating racial/ethnic disparities in lower urinary tract symptoms in men. J Urol. 2012 Jan;187(1):185-9. Epub 2011 Nov 17. PMID: 22100004; PMCID: PMC4005424. [CrossRef]

- Stamatelou K, Goldfarb DS. Epidemiology of Kidney Stones. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Feb 2;11(3):424. PMID: 36766999; PMCID: PMC9914194. [CrossRef]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16.

- Assari S. Unequal gain of equal resources across racial groups. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(1):1–9.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos WL, Collins KA, Diaz R, Duber HC, Edwards CD, Hsu AP, Ranney ML, Riviello RJ, Wettstein ZS, Sachs CJ. Race, Healthcare, and Health Disparities: A Critical Review and Recommendations for Advancing Health Equity. West J Emerg Med. 2023 Sep;24(5):906-918. PMID: 37788031; PMCID: PMC10527840. [CrossRef]

- Magadi JP, Magadi MA. Ethnic inequalities in patient satisfaction with primary health care in England: Evidence from recent General Practitioner Patient Surveys (GPPS). PLoS One. 2022 Dec 21;17(12):e0270775. PMID: 36542601; PMCID: PMC9770381. [CrossRef]

- Brown CE, Jackson SY, Marshall AR, Pytel CC, Cueva KL, Doll KM, Young BA. Discriminatory Healthcare Experiences and Medical Mistrust in Patients With Serious Illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024 Apr;67(4):317-326.e3. Epub 2024 Jan 11. PMID: 38218413; PMCID: PMC11000579. [CrossRef]

- Yearby R, Clark B, Figueroa JF. Structural Racism In Historical And Modern US Health Care Policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022 Feb;41(2):187-194. PMID: 35130059. [CrossRef]

- Lim KB. Epidemiology of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian J Urol. 2017 Jul;4(3):148-151. Epub 2017 Jun 9. PMID: 29264223; PMCID: PMC5717991. [CrossRef]

- Rooney MK, Santiago G, Perni S, Horowitz DP, McCall AR, Einstein AJ, Jagsi R, Golden DW. Readability of Patient Education Materials From High-Impact Medical Journals: A 20-Year Analysis. J Patient Exp. 2021 Mar 3;8:2374373521998847. PMID: 34179407; PMCID: PMC8205335. [CrossRef]

- “Mann-Whitney U Test Calculator.” Social Science Statistics, www.socscistatistics.com/tests/mannwhitney/default2.aspx. Accessed 19 May 2025.

- Thibau IJ, Loiselle AR, Latour E, et al. Past, present, and future shared decision-making behavior among patients with eczema and caregivers. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(8):912-918. [CrossRef]

- Truglio-Londrigan M, Slyer JT, Singleton JK, Worral P. A qualitative systematic review of internal and external influences on shared decision-making in all health care settings. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(58):4633–46. [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E., Fardy, H.J. and Harris, P.G. (2003), Getting it right: why bother with patient-centred care?. Medical Journal of Australia, 179: 253-256. [CrossRef]

- DerGurahian, Jean. “Focusing on the patient. Planetree guide touts patient-centered care model.” Modern Healthcare 38.43 (2008): 7-7.

- Elwyn G, Coulter A, Laitner S, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146. [CrossRef]

- Stacey, Dawn, et al. “Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions.” Cochrane database of systematic reviews 4 (2017).

- Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Assessing readability of patient education materials: current role in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010 Oct;468(10):2572-80. PMID: 20496023; PMCID: PMC3049622. [CrossRef]

- Safeer RS, Keenan J. Health literacy: the gap between physicians and patients. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Aug 1;72(3):463-8. PMID: 16100861.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 2004. Accessed January 1, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216032/.

- 25. Lopez Vera, A., Thomas, K., Trinh, C. et al. A Case Study of the Impact of Language Concordance on Patient Care, Satisfaction, and Comfort with Sharing Sensitive Information During Medical Care. J Immigrant Minority Health 25, 1261–1269 (2023).

- Emma Danielle Grellinger, Ishaan Swarup, Barriers to Health Care Communication: Patient Education Resource Readability and Spanish Translation for Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis, Journal of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America, Volume 8, 2024, 100076, ISSN 2768-2765. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2768276524009027). [CrossRef]

- Novin SA, Huh EH, Bange MG, Hui FK, Yi PH. Readability of Spanish-Language Patient Education Materials From RadiologyInfo.org. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019 Aug;16(8):1108-1113. Epub 2019 Apr 5. PMID: 30956087. [CrossRef]

- Medrano, Francisco J et al. “Limited English Proficiency in Older Adults Referred to the Cardiovascular Team.” The American journal of medicine vol. 136,5 (2023): 432-437. [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Vera AV, Colbert GB, Lerma EV. Positive and negative impact of social media in the COVID-19 era. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020 Dec 30;21(4):561-564. PMID: 33388000. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).