Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. GMO-Free Genetic Improvement Techniques

2.1. Classical Genetic Improvement Techniques for Non-GMO Yeasts

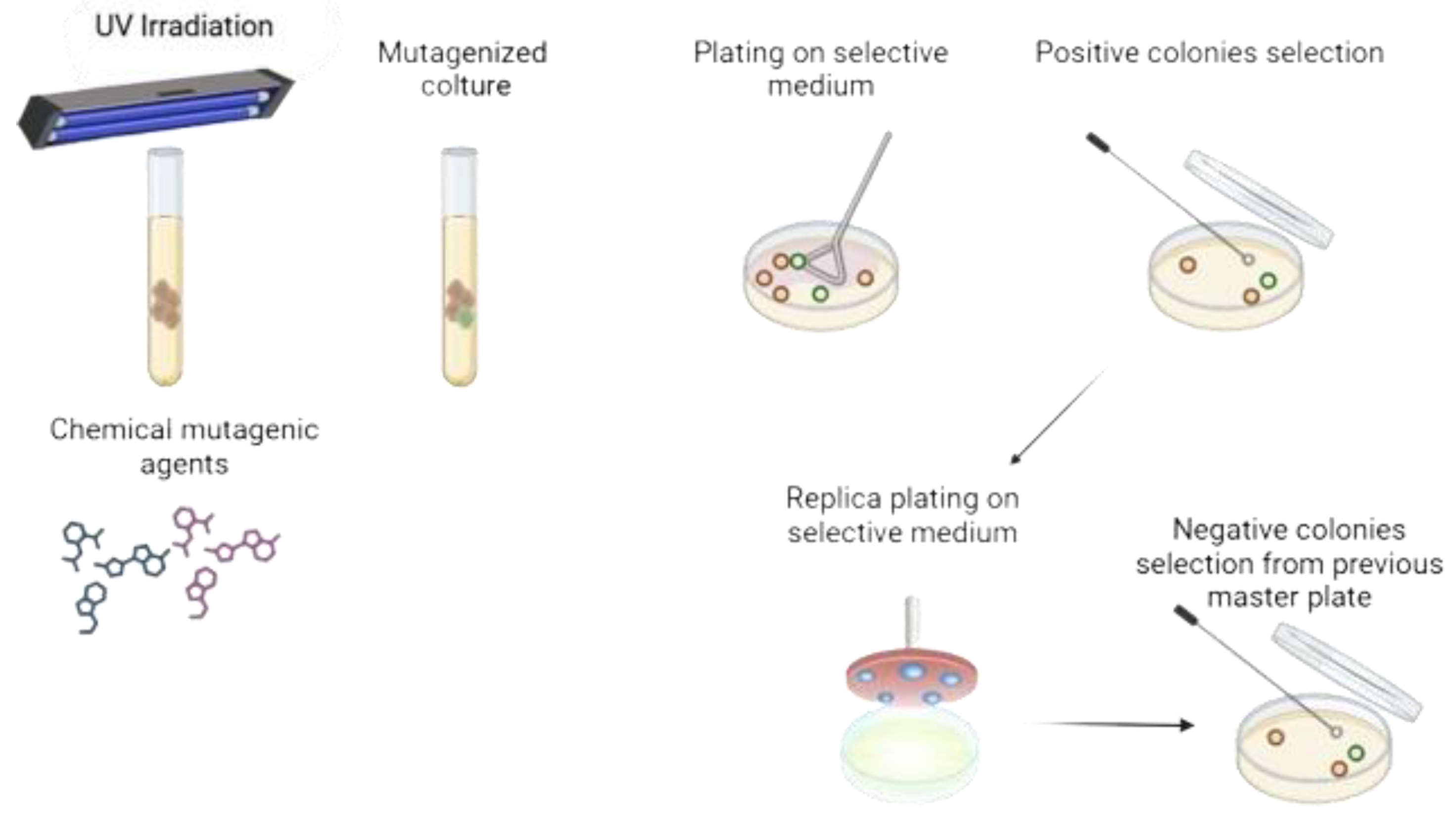

2.1.1. Random Mutagenesis

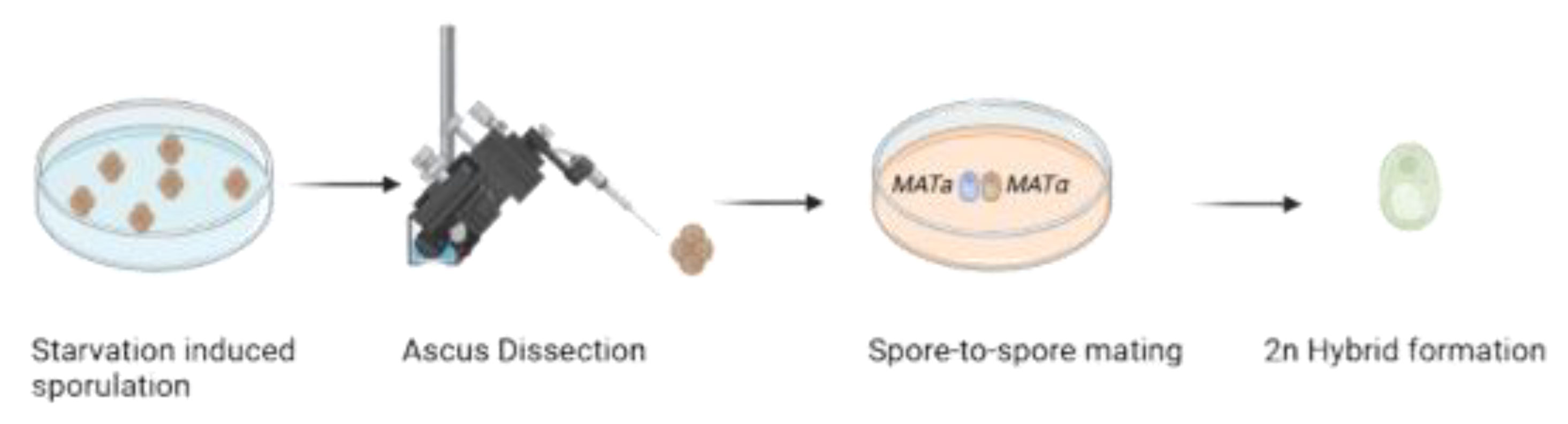

2.1.2. Sexual Hybridization

2.2. Innovative Genetic Improvement Techniques in Fermentation

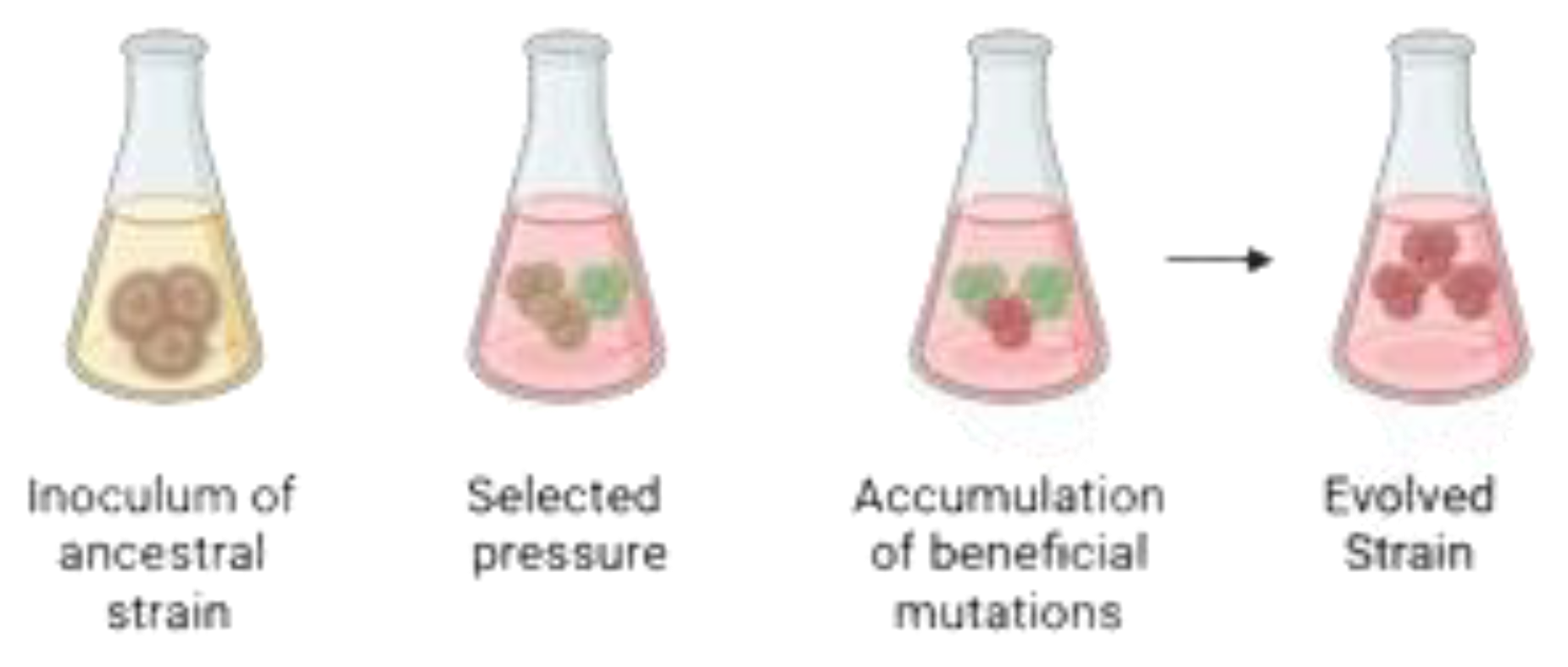

2.2.1. Adaptive Laboratory Evolution - ALE

2.2.2. Big Data, AI and Omics

2.2.3. Synthetic Microbial Communities

2.3. GMO-Based Genetic Improvement Techniques

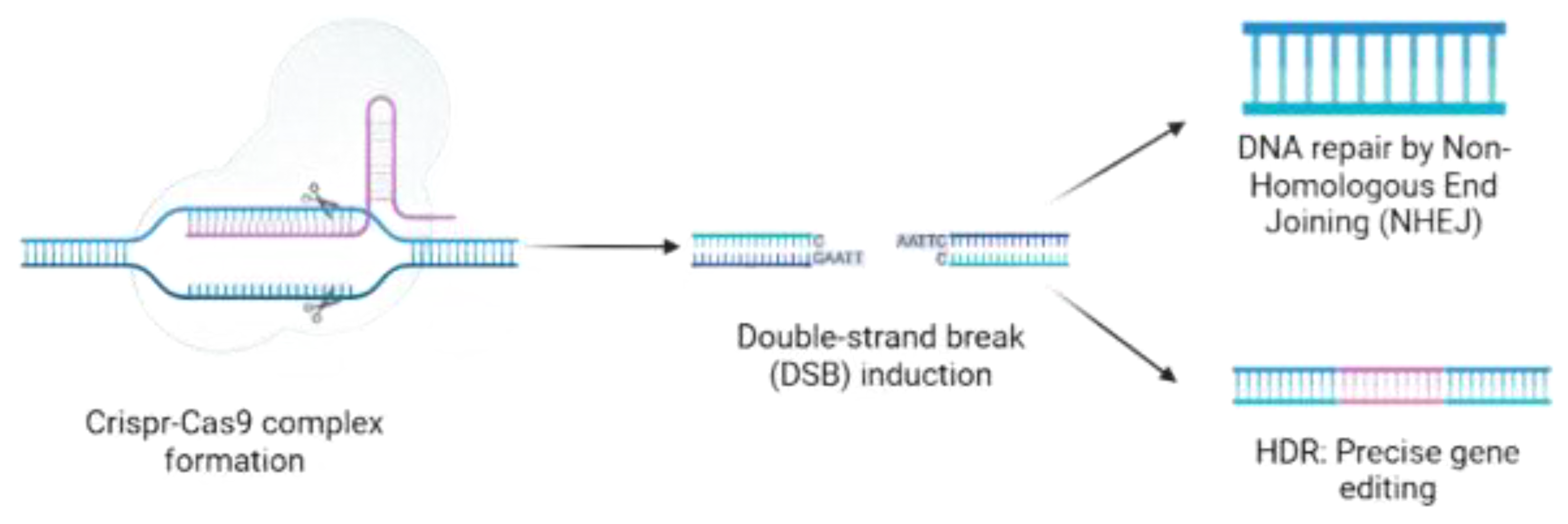

2.3.1. Synthetic Biology and CRISPR/Cas9

2.3.2. Ethical and Commercial Challenges

3. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Belderok, B. Developments in bread-making processes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2000, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saerens, S.M.G.; Duong, C.T.; Nevoigt, E. Genetic improvement of brewer’s yeast: current state, perspectives and limits. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 1195–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. Production of biopharmaceutical proteins by yeast: Advances through metabolic engineering. Bioengineered 2013, 4, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botstein, D.; Chervitz, S.A.; Cherry, M. Yeast as a Model Organism. Science 1997, 277, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, M.R.; Greig, D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a nomadic yeast with no niche? FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.; De Chiara, M.; Friedrich, A.; Yue, J.X.; Pflieger, D.; Bergström, A.; Sigwalt, A.; Barre, B.; Freel, K.; Llored, A.; Cruaud, C. Genome evolution across 1,011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates. Nature 2018, 556, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretorius, I.S.; Boeke, J.D. Yeast 2.0—connecting the dots in the construction of the world’s first functional synthetic eukaryotic genome. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T.; Skinner, H. Territorial brand management: Beer, authenticity, and sense of place. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbo, F.; De Meo, E.; Baiano, A.; Carlucci, D. The Value of Craft Beer Styles: Evidence from the Italian Market. Foods 2023, 12, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018. World Health Organization; 2019. 472 p.

- Wheat Beers Market Research Report 2023.

- Pretorius, I.S. Tailoring wine yeast for the new millennium: novel approaches to the ancient art of winemaking. Yeast 2000, 16, 675–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatto, D. The diversity of commercially available ale and lager yeast strains and the impact of brewer’s preferential yeast choice on the fermentative beer profiles. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libkind, D.; Hittinger, C.T.; Valério, E.; Gonçalves, C.; Dover, J.; Johnston, M.; Gonçalves, P.; Sampaio, J.P. Microbe domestication and the identification of the wild genetic stock of lager-brewing yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14539–14544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, B.; Dahabieh, M.; Krogerus, K.; Jouhten, P.; Magalhães, F.; Pereira, R.; Siewers, V.; Vidgren, V. Adaptive Laboratory Evolution of Ale and Lager Yeasts for Improved Brewing Efficiency and Beer Quality. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogerus, K.; Magalhães, F.; Vidgren, V.; Gibson, B. New lager yeast strains generated by interspecific hybridization. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutzler, M.; Morrissey, J.P.; Laus, A.; Meussdoerffer, F.; Zarnkow, M. A new hypothesis for the origin of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus. FEMS Yeast Res. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta, V.; Pérez-Través, L.; Saona, L.A.; Villarroel, C.A.; Querol, A.; Cubillos, F.A.; Gibbons, J.G. Understanding brewing trait inheritance in de novo Lager yeast hybrids. mSystems 2024, 9, e0076224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Dong, G.; Bian, M.; Liu, X.; Dong, X.; Xia, T. Multi-omics study revealed the genetic basis of beer flavor quality in yeast. LWT 2022, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, E.J.; Chan, R.; Prasad, N.; Myers, S.; Petzold, C.J.; Redding, A.; Ouellet, M.; Keasling, J.D. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of n-butanol. Microb. Cell Factories 2008, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saerens, S.; Swiegers, J.H. Production of low-alcohol or alcohol-free beer with. Pichia kluyveri. 2014.

- Giudici, P.; Solieri, L.; Pulvirenti, A.M.; Cassanelli, S. Strategies and perspectives for genetic improvement of wine yeasts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 66, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torrado, R.; Querol, A.; Guillamón, J.M. Genetic improvement of non-GMO wine yeasts: Strategies, advantages and safety. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, D.; Casal, M. The use of genetically modified Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains in the wine industry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 68, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinet, J.; Navarrete, J.P.; Villarroel, C.A.; Villarreal, P.; Sandoval, F.I.; Nespolo, R.F.; Stelkens, R.; Cubillos, F.A.; Sampaio, J.P. Wild Patagonian yeast improve the evolutionary potential of novel interspecific hybrid strains for lager brewing. PLOS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osburn, K.; Amaral, J.; Metcalf, S.R.; Nickens, D.M.; Rogers, C.M.; Sausen, C.; Caputo, R.; Miller, J.; Li, H.; Tennessen, J.M.; Bochman, M.L. Primary souring: a novel bacteria-free method for sour beer production. Food Microbiology 2018, 70, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domizio, P.; House, J.F.; Joseph, C.M.; Bisson, L.F.; Bamforth, C.W. Lachancea thermotolerans as an alternative yeast for the production of beer. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 2016, 122, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Borneman, A.R. Yeasts found in vineyards and wineries. Yeast 2016, 34, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinet, J.; Navarrete, J.P.; Villarroel, C.A.; Villarreal, P.; Sandoval, F.I.; Nespolo, R.F.; Stelkens, R.; Cubillos, F.A.; Sampaio, J.P. Wild Patagonian yeast improve the evolutionary potential of novel interspecific hybrid strains for lager brewing. PLOS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akada, R.; Hirosawa, I.; Kawahata, M.; Hoshida, H.; Nishizawa, Y. Sets of integrating plasmids and gene disruption cassettes containing improved counter-selection markers designed for repeated use in budding yeast. Yeast 2002, 19, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, A.R.G.; Knibbe, E.; van Roosmalen, R.; Broek, M.v.D.; Cortés, P.d.l.T.; O’herne, S.F.; Vijverberg, P.A.; el Masoudi, A.; Brouwers, N.; Pronk, J.T.; et al. Improving Industrially Relevant Phenotypic Traits by Engineering Chromosome Copy Number in Saccharomyces pastorianus. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diderich, J.A.; Weening, S.M.; Broek, M.v.D.; Pronk, J.T.; Daran, J.-M.G. Selection of Pof-Saccharomyces eubayanus Variants for the Construction of S. cerevisiae × S. eubayanus Hybrids With Reduced 4-Vinyl Guaiacol Formation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J.-M.; Barre, P. Improvement of Nitrogen Assimilation and Fermentation Kinetics under Enological Conditions by Derepression of Alternative Nitrogen-Assimilatory Pathways in an Industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 3831–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós, M.; Gonzalez-Ramos, D.; Tabera, L.; Gonzalez, R. A new methodology to obtain wine yeast strains overproducing mannoproteins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 139, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordente, A.G.; Cordero-Bueso, G.; Pretorius, I.S.; Curtin, C.D. Novel wine yeast with mutations in YAP1 that produce less acetic acid during fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2013, 13, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöhrmann, K.; Lance, P. THE POLYMORPHISM OF ESTERASES IN YEAST (SACCHAROMYCES CEREVISIAE). J. Inst. Brew. 1980, 86, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, P.; Zinnato, A. Influenza dell’uso di mutanti nutrizionali sulla produzione di alcooli superiori. Vignevini 1983, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Rous, C.V.; Snow, R.; Kunkee, R.E. REDUCTION OF HIGHER ALCOHOLS BY FERMENTATION WITH A LEUCINE-AUXOTROPHIC MUTANT OF WINE YEAST. J. Inst. Brew. 1983, 89, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogerus, K.; Arvas, M.; De Chiara, M.; Magalhães, F.; Mattinen, L.; Oja, M.; Vidgren, V.; Yue, J.-X.; Liti, G.; Gibson, B. Ploidy influences the functional attributes of de novo lager yeast hybrids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 7203–7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyurchev, N.Y.; Coral-Medina, Á.; Weening, S.M.; Almayouf, S.; Kuijpers, N.G.A.; Nevoigt, E.; Louis, E.J. Beyond Saccharomyces pastorianus for modern lager brews: Exploring non-cerevisiae Saccharomyces hybrids with heterotic maltotriose consumption and novel aroma profile. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1025132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenbruch, R.; Cresswell, K.J.; Fisher, B.M.; Thornton, R.J. Selective hybridisation of pure culture wine yeasts. Eur. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1982, 14, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, T.; Mamiya, S.; Yanagida, F. Introduction of flocculation property into wine yeasts (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) by hybridization. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1997, 83, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulin, J.; Krogerus, K.; Gibson, B. Alternative Saccharomyces interspecies hybrid combinations and their potential for low-temperature wort fermentation. Yeast 2017, 35, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallone, B.; Steensels, J.; Prahl, T.; Soriaga, L.; Saels, V.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Merlevede, A.; Roncoroni, M.; Voordeckers, K.; Miraglia, L.; et al. Domestication and Divergence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Beer Yeasts. Cell 2016, 166, 1397–1410.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.; Pontes, A.; Almeida, P.; Barbosa, R.; Serra, M.; Libkind, D.; Hutzler, M.; Gonçalves, P.; Sampaio, J.P. Distinct Domestication Trajectories in Top-Fermenting Beer Yeasts and Wine Yeasts. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2750–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, H.D.; Dagher, S.F.; Bruno-Bárcena, J.M. Production and conservation of starter cultures: From “backslopping” to controlled fermentations. How fermented foods feed a healthy gut microbiota: A nutrition continuum. 2019:125-38. [CrossRef]

- Beato, F.B.; Bergdahl, B.; Rosa, C.A.; Forster, J.; Gombert, A.K.; Kang, H. Physiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains isolated from Brazilian biomes: new insights into biodiversity and industrial applications. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fow076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, N.P.; Sandell, L.; James, C.G.; Otto, S.P. The genome-wide rate and spectrum of spontaneous mutations differ between haploid and diploid yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, E5046–E5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, P. Current Status and Applications of Adaptive Laboratory Evolution in Industrial Microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauet, G.; Degryse, E.; Ledoux, C.; Spagnoli, R.; Achstetter, T. Pregnenolone esterification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 261, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrommati, M.; Daskalaki, A.; Papanikolaou, S.; Aggelis, G. Adaptive laboratory evolution principles and applications in industrial biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 54, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattenberger, F.; Fares, M.A.; Toft, C.; Sabater-Muñoz, B. The Role of Ancestral Duplicated Genes in Adaptation to Growth on Lactate, a Non-Fermentable Carbon Source for the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Tronchoni, J.; Quirós, M.; Morales, P. Genetic improvement and genetically modified microorganisms. Wine Safety, Consumer Preference, and Human Health. 2016:71-96. [CrossRef]

- Blieck, L.; Toye, G.; Dumortier, F.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Delvaux, F.R.; Thevelein, J.M.; Van Dijck, P. Isolation and Characterization of Brewer’s Yeast Variants with Improved Fermentation Performance under High-Gravity Conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogerus, K.; Holmström, S.; Gibson, B.; Schaffner, D.W. Enhanced Wort Fermentation with De Novo Lager Hybrids Adapted to High-Ethanol Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrahami-Moyal, L.; Engelberg, D.; Wenger, J.W.; Sherlock, G.; Braun, S. Turbidostat culture of Saccharomyces cerevisiae W303-1A under selective pressure elicited by ethanol selects for mutations in SSD1 and UTH1. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012, 12, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.K.; Tremaine, M.; Parreiras, L.S.; Hebert, A.S.; Myers, K.S.; Higbee, A.J.; et al. Directed Evolution Reveals Unexpected Epistatic Interactions That Alter Metabolic Regulation and Enable Anaerobic Xylose Use by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLOS Genetics 2016, 12, e1006372. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.C. Improvement of Torulaspora delbrueckii’s sulphite resistance in winemaking through Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (Doctoral dissertation).

- Bartel, C.; Roach, M.; Onetto, C.; Curtin, C.; Varela, C.; Borneman, A. Adaptive evolution of sulfite tolerance in Brettanomyces bruxellensis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yin, H.; Dong, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yan, P.; Wan, X.; Hou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, R.; et al. Reduced sensitivity of lager brewing yeast to premature yeast flocculation via adaptive evolution. Food Microbiol. 2022, 106, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutyna, D.R.; Varela, C.; Stanley, G.A.; Borneman, A.R.; Henschke, P.A.; Chambers, P.J. Adaptive evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to generate strains with enhanced glycerol production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 93, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzetti, F.; De Vero, L.; Giudici, P. Evolved Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine strains with enhanced glutathione production obtained by an evolution-based strategy. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, A.; Kayacan, E. A novel fractional-order type-2 fuzzy control method for online frequency regulation in ac microgrid. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Osório, C.; Sousa, M.J.; Franco-Duarte, R. Contributions of Adaptive Laboratory Evolution towards the Enhancement of the Biotechnological Potential of Non-Conventional Yeast Species. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo, E.E.; Teixeira Benites, V. Mass spectrometry-based microbial metabolomics: Techniques, analysis, and applications. Microbial metabolomics: methods and protocols 2019, 11–69. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, B.; Baidoo, E.E.K. Omics-Driven Biotechnology for Industrial Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sánchez, B.J.; Li, F.; Eiden, C.W.Q.; Scott, W.T.; Liebal, U.W.; Blank, L.M.; Mengers, H.G.; Anton, M.; Rangel, A.T.; et al. Yeast9: a consensus genome-scale metabolic model for S. cerevisiae curated by the community. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2024, 20, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogerus, K.; Rettberg, N. Creating Better Brewing Yeast With the 1011 Yeast Genomes Data Sets. Yeast 2025, 42, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, E.H.; Alves Jr, S.L.; Dunn, B.; Sherlock, G.; Stambuk, B.U. Microarray karyotyping of maltose-fermenting Saccharomyces yeasts with differing maltotriose utilization profiles reveals copy number variation in genes involved in maltose and maltotriose utilization. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2010, 109, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogerus, K.; Magalhães, F.; Kuivanen, J.; Gibson, B. A deletion in the STA1 promoter determines maltotriose and starch utilization in STA1+ Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 7597–7615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristão, L.E.; de Sousa, L.I.S.; Vargas, B.d.O.; José, J.; Carazzolle, M.F.; Silva, E.M.; Galhardo, J.P.; Pereira, G.A.G.; Mello, F.d.S.B.d. Unveiling genetic anchors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: QTL mapping identifies IRA2 as a key player in ethanol tolerance and beyond. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2024, 299, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albillos-Arenal, S.; Alonso-del-Real, J.; Lairón-Peris, M.; Barrio, E.; Querol, A. Identification of a crucial INO2 allele for enhancing ethanol resistance in an industrial fermentation strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, H.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Multi-omics discovery of aroma-active compound formation by Pichia kluyveri during cider production. LWT 2022, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, N.; Badura, J.; von Wallbrunn, C.; Pretorius, I.S. Exploring future applications of the apiculate yeast Hanseniaspora. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2023, 44, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Petersen, S.D.; Radivojevic, T.; Ramirez, A.; Pérez-Manríquez, A.; Abeliuk, E.; Sánchez, B.J.; Costello, Z.; Chen, Y.; Fero, M.J.; et al. Combining mechanistic and machine learning models for predictive engineering and optimization of tryptophan metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, T.; Xu, M.; Lin, S.; Hu, B.; Chu, T.; Liu, B.; Xu, Y.; Ding, W.; Li, L.; et al. Spatial multi-omics: deciphering technological landscape of integration of multi-omics and its applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radivojević, T.; Costello, Z.; Workman, K.; Martin, H.G. A machine learning Automated Recommendation Tool for synthetic biology. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, S.; Shitut, S.; Kost, C. Harnessing ecological and evolutionary principles to guide the design of microbial production consortia. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittermeier, F.; Bäumler, M.; Arulrajah, P.; Lima, J.d.J.G.; Hauke, S.; Stock, A.; Weuster-Botz, D. Artificial microbial consortia for bioproduction processes. Eng. Life Sci. 2022, 23, e2100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, B.; Bauer, F.F.; Setati, M.E. The Impact of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on a Wine Yeast Consortium in Natural and Inoculated Fermentations. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conacher, C.G.; Naidoo-Blassoples, R.K.; Rossouw, D.; Bauer, F.F. Real-time monitoring of population dynamics and physical interactions in a synthetic yeast ecosystem by use of multicolour flow cytometry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 5547–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, B.; Bauer, F.; Setati, M. The Diversity and Dynamics of Indigenous Yeast Communities in Grape Must from Vineyards Employing Different Agronomic Practices and their Influence on Wine Fermentation. South Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 36, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, D.; Pereira, F.; Geissen, E.M.; Grkovska, K.; Kafkia, E.; Jouhten, P.; Kim, Y.; Devendran, S.; Zimmermann, M.; Patil, K.R. Adaptive laboratory evolution of microbial co-cultures for improved metabolite secretion. Molecular systems biology 2021, 17, e10189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roell, M.-S.; Zurbriggen, M.D. The impact of synthetic biology for future agriculture and nutrition. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, R.G.; Steenwerth, K.L.; Mills, D.A.; Cantu, D.; Bokulich, N.A. Sources and assembly of microbial communities in vineyards as a functional component of winegrowing. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 673810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlhanka, K.; Lebani, K.; Boekhout, T.; Zhou, N. Fermentative Microbes of Khadi, a Traditional Alcoholic Beverage of Botswana. Fermentation 2020, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, A.; O’SUllivan, T.; Sinderen, D. Enhancing the Microbiological Stability of Malt and Beer - A Review. J. Inst. Brew. 2005, 111, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, A.; Portillo, M.C. Strategies for microbiological control of the alcoholic fermentation in wines by exploiting the microbial terroir complexity: A mini-review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 367, 109592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, N.; Augustyn, O.; Pretorius, I. The Occurrence of Non-Saccharomyces cerevisiae Yeast Species Over Three Vintages in Four Vineyards and Grape Musts From Four Production Regions of the Western Cape, South Africa. South Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2003, 24, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, J.; Pizarro, F.; Pérez-Correa, J.R.; Agosin, E. Modeling of yeast metabolism and process dynamics in batch fermentation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 81, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, L.M.; de Nadra, M.C.M.; Bru, E.; Farías, M.E. Influence of wine-related physicochemical factors on the growth and metabolism of non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces yeasts in mixed culture. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 36, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B.; Cocolin, L.; Mas, A.; Rantsiou, K. Viable and culturable populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Hanseniaspora uvarum and Starmerella bacillaris (synonym Candida zemplinina) during Barbera must fermentation. Food Research International 2015, 78, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albergaria, H.; Arneborg, N. Dominance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in alcoholic fermentation processes: role of physiological fitness and microbial interactions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2035–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 94. Cambon, B.; Monteil, V.; Remize, F.; Camarasa, C.; Dequin, S. Effects of GPD1 Overexpression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Commercial Wine Yeast Strains Lacking ALD6 Genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2006, 72, 4688–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcı, K.; Walls, L.E.; Rios-Solis, L. Multiplex Genome Engineering Methods for Yeast Cell Factory Development. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 589468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebollero, E.; Gonzalez-Ramos, D.; Tabera, L.; Gonzalez, R. Transgenic wine yeast technology comes of age: is it time for transgenic wine? Biotechnol. Lett. 2006, 29, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCarlo, J.E.; Norville, J.E.; Mali, P.; Rios, X.; Aach, J.; Church, G.M. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 4336–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidenne, C.; Blondin, B.; Dequin, S.; Vezinhet, F. Analysis of the chromosomal DNA polymorphism of wine strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 1992, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, Y.; You, Q.; Li, Q.; Yuan, M.; He, Y.; Qi, C.; Tang, X.; Zheng, X.; et al. Bidirectional Promoter-Based CRISPR-Cas9 Systems for Plant Genome Editing. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Geng, A. High-copy genome integration of 2,3-butanediol biosynthesis pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via in vivo DNA assembly and replicative CRISPR-Cas9 mediated delta integration. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 310, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Shen, J.; Li, D.; Cheng, Y. Strategies in the delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Theranostics 2021, 11, 614–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, Y.; Yadav, P.; Sharma, A.K.; Pandey, P.; Kuila, A. Multiplex genome editing to construct cellulase engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae for ethanol production from cellulosic biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, S.; Gallone, B.; Steensels, J.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Cortebeek, J.; Nolmans, R.; et al. Reducing phenolic off-flavors through CRISPR-based gene editing of the FDC1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae x Saccharomyces eubayanus hybrid lager beer yeasts. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0209124. [Google Scholar]

- Dank, A.; Smid, E.J.; Notebaart, R.A. CRISPR-Cas genome engineering of esterase activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae steers aroma formation. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogerus, K.; Fletcher, E.; Rettberg, N.; Gibson, B.; Preiss, R. Efficient breeding of industrial brewing yeast strains using CRISPR/Cas9-aided mating-type switching. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 8359–8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.P.; González, R.; Querol, A.; Sendra, J.; Ramón, D. Construction of a recombinant wine yeast strain expressing β-(1, 4)-endoglucanase and its use in microvinification process. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1993, 59, 2801–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigentini, I.; Gebbia, M.; Belotti, A.; Foschino, R.; Roth, F.P. The CRISPR/Cas9 system as a molecular strategy to decrease urea production in wine yeasts (2017).

- Hirata, D.; Aoki, S.; Watanabe, K.-I.; Tsukioka, M.; Suzuki, T. Stable Overproduction of Isoamyl Alcohol by Saccharomyces cerevisiae with Chromosome-integrated Multicopy LEU4 Genes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1992, 56, 1682–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamoto, K.; Oda, K.; Gomi, K.; Takahashi, K. Genetic engineering of a sake yeast producing no urea by successive disruption of arginase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeman, H.; Vivier, M.A.; du Toit, M.; Dicks, L.M.T.; Pretorius, I.S. The development of bactericidal yeast strains by expressing thePediococcus acidilactici pediocin gene (pedA) inSaccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1999, 15, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, H.; Fujii, T.; Kondo, K.; Shimizu, F.; Tanaka, J.; Inoue, T. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the Enterobacter aerogenes alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase gene in brewer’s yeast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volschenk, H.; Viljoen, M.; Grobler, J.; Bauer, F.; Lonvaud-Funel, A.; Denayrolles, M.; Subden, R.E.; Van Vuuren, H.J.J. Malolactic Fermentation in Grape Musts by a Genetically Engineered Strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1997, 48, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denby, C.M.; Li, R.A.; Vu, V.T.; Costello, Z.; Lin, W.; Chan, L.J.G.; Williams, J.; Donaldson, B.; Bamforth, C.W.; Petzold, C.J.; et al. Industrial brewing yeast engineered for the production of primary flavor determinants in hopped beer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruijter, J.C.; Aisala, H.; Jokinen, I.; Krogerus, K.; Rischer, H.; Toivari, M. Production and sensory analysis of grape flavoured beer by co-fermentation of an industrial and a genetically modified laboratory yeast strain. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzogara, S.G. The impact of genetic modification of human foods in the 21st century. Biotechnol. Adv. 2000, 18, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2001/18/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 March 2001 on the deliberate release into the environment of genetically modified organisms and repealing Council Directive 90/220/EEC - Commission Declaration.

- Davison, J.; Ammann, K. New GMO regulations for old: Determining a new future for EU crop biotechnology. GM Crop. Food 2017, 8, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasuti, C.; Solieri, L. Yeast Bioflavoring in Beer: Complexity Decoded and Built up Again. Fermentation 2024, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

|

CRISPR-Cas9 GMO |

Precise and efficient genome editing; Allows for modifications of multiple genes at once; highly versatile across different yeast strains. |

Ethical concerns around gene editing; Requires optimization for different yeast species; Requires advanced understanding of yeast genetics |

|

Synthetic Microbial Communities (SMC) GMO or Non-GMO (depending on strains used) |

Enables creation of yeast strains consortia with complementary traits that work together; Can improve metabolic networks. |

Requires compatibility between strains, including nutrient requirements; If OGM strains are used, there are ethical concerns around genetic modifications. |

|

Hybridization Non-GMO |

Simple method to combine beneficial traits from different yeast strains; Heterosis compared with parents; Well-established and cost-effective. |

May result in sterility or instability of the hybrid offspring; Difficult to obtain for poorly sporulating strains; undesirable characteristics may emerge. |

|

Mutagenesis Non-GMO |

Generates a wide variety of potential phenotypes; Relatively inexpensive and straightforward; Suitable for monogenic phenotypes. |

Random outcomes make it difficult to predict results; Can introduce harmful mutations or undesired traits; Not suitable for polygenic or complex phenotypes. |

|

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) Non-GMO |

Mimics natural selection, leading to improved fitness-related traits over time; Suitable for phenotypes that can be directly selected under controlled environments. |

Time-consuming and labor-intensive; Unintended side effects may occur, as it is difficult to control specific outcomes; May not be suitable for traits without clear selection markers. |

|

Multi-Omics and AI Integration Non-GMO |

Provides a comprehensive view of yeast metabolism and gene expression; Unintended side effects may occur, as it is difficult to control specific outcomes. |

Requires large data sets and significant computational resources; Interpreting the data can be complex and requires expert knowledge. |

| Objective | Work |

|---|---|

| Increased ethanol tolerance | [31] |

| Elimination of phenolic off-flavors (POF) | [32] |

| Enhanced nitrogen source utilization | [33] |

| Increased mannoprotein release | [34] |

| Reduced volatile acidity | [35] |

| Increased aroma compound concentration (esters) | [36] |

| Reduction of isoamyl alcohol (3-methylbutanol) production | [37] |

| Objective | Work |

|---|---|

| Improved fermentation and aroma production in lager hybrids | [19,30,39,40] |

| Elimination of undesirable traits (e.g., SO₂ formation, excessive foam production) | [41] |

| Enhanced wine quality and fermentation rates via interspecific hybridization | [23,42] |

| Objective | Work |

|---|---|

| Increased tolerance to acetic acid | [53] |

| Selection of Atf2-overexpressing strains for ester formation and pregnenolone detoxification | [50] |

| Improved beer yeast performance via UV mutagenesis and high-gravity wort fermentations | [54] |

| Enhanced ethanol tolerance in hybrid yeasts | [55] |

| Genomic adaptations linked to chromosomal duplications and mutations in IRA2 and UTH1 | [56,57] |

| Increased sulfite tolerance in T. delbrueckii | [58] |

| Enhanced sulfite resistance in B. bruxellensis | [59] |

| Adaptation of Saccharomyces variants to overcome premature yeast flocculation (PYF) | [60] |

| Reduction of phenolic off-flavors via PAD1 and FDC1 mutations | [44,45] |

| Increased glycerol production for lower ethanol wines | [61] |

| Development of yeast strains producing higher levels of glutathione (GSH) | [62] |

| Enhanced yeast flocculation for easier removal after fermentation | [63] |

| Application | Involved Species | Work |

|---|---|---|

| Alcoholic fermentation in beer production | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | [86] |

| Bio-acidification and microbial control in beer | Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) | [87] |

| Malolactic fermentation for flavor complexity in wine | Oenococcus oeni | [86] |

| Adaptation to vineyard microbial terroir | Various LAB and yeast species | [88] |

| Yeast community shifts during grape must fermentation | K. apiculate, C. stellata, C. pulcherrima | [89] |

| Influence of nutrient scarcity, oxygen availability, and ethanol on fermentation | Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other yeasts | [90,91] |

| Ecological interactions driving fermentation outcomes | Multiple yeast species | [92] |

| Yeast-yeast interactions, including S. cerevisiae with non-Saccharomyces species | Wickerhamomyces anomalus, Hanseniaspora vineae | [93] |

| Persistence of certain non-Saccharomyces yeasts in vineyard ecosystems | Starmerella bacillaris, Lachancea thermotolerans | [94] |

| Yeast ecosystem modulation by S. cerevisiae | Various non-Saccharomyces species | [80] |

| Optimization of yeast interactions for improved fermentation | Selected co-cultures of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces | [89] |

| Process | Technique | References |

|---|---|---|

| GPD1 overexpression and ALD6 delation to reduce reduce alcohol yield in wine yeast | Episomal vector; KanMX deletion cassette | [94] |

| Expression of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes to improve juice extraction and release primary aromas | Episomal vector constructed by restriction cloning | [106] |

| Reduction of urea and ethyl carbamate formation | CRISPR/Cas9 | [107] |

| Overexpression of LEU4 (α-isopropylmalate synthase) in sake yeast to increase isoamyl alcohol and esters | Plasmid multicopy integration at chromosome level | [108] |

| Reduction of ethyl carbamate production | Plasmid distruption | [109] |

| Heterologous expression of pediocin to increase resistance to wild yeasts and bacteria | Episomal vector constructed by restriction cloning | [110] |

| Expression of acetolactate decarboxylase (ALDC) to reduce diacetyl formation | Episomal vector constructed by restriction cloning | [111] |

| Expression of malolactic enzymes to degrade malate and integrate malolactic fermentation | Episomal vector constructed by restriction cloning | [112] |

| Engineering yeast strains to produce hop monoterpenes | Plasmids obtained by Golden Gate assembly | [113] |

| Engineering yeast strains to produce methyl anthranilate with grape aroma | CRISPR/Cas9 | [114] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).