1. Introduction

Circadian rhythms (

circa diem = about a day) are endogenous, near-24-hour cycles that orchestrate a wide range of physiological processes in humans, including the sleep–wake cycle, hormone secretion, metabolism, and behavior [

1]. These rhythms persist even in the absence of external cues, reflecting the activity of an internal biological clock [

2]. In humans, the primary environmental synchronizer is light, which entrains the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the master pacemaker located in the hypothalamus. Light signals modulate the expression of core clock genes, including the transcriptional activators

CLOCK and

BMAL1 (ARNTL1), and the repressor genes

PER and

CRY, through tightly regulated transcription-translation feedback loops [

3]. This molecular mechanism drives rhythmic outputs from the SCN that are propagated to peripheral clocks via neural, hormonal, and behavioral pathways, prominently involving the hormones melatonin and cortisol [

4].

Approximately 80% of protein-coding genes exhibit circadian expression patterns, underscoring the system’s broad physiological impact. Disruption of circadian rhythms has been implicated in a wide spectrum of disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases [

5], cancer [

6,

7], diabetes [

8], cardiovascular conditions [

9], psychiatric illnesses [

10], and sleep disorders such as insomnia, delayed and advance sleep-wake phase disorders [

11], and sleep apnea [

12,

13,

14]. In addition the hepatic drug metabolism system is long known to be under circadian control [

15]. Thus, the circadian regulation of drug targets has revealed new opportunities for chronotherapy, where timing of medication can improve efficacy and reduce side effects [

16,

17]. Despite this progress, many mechanistic aspects of circadian disruption in disease remain poorly understood.

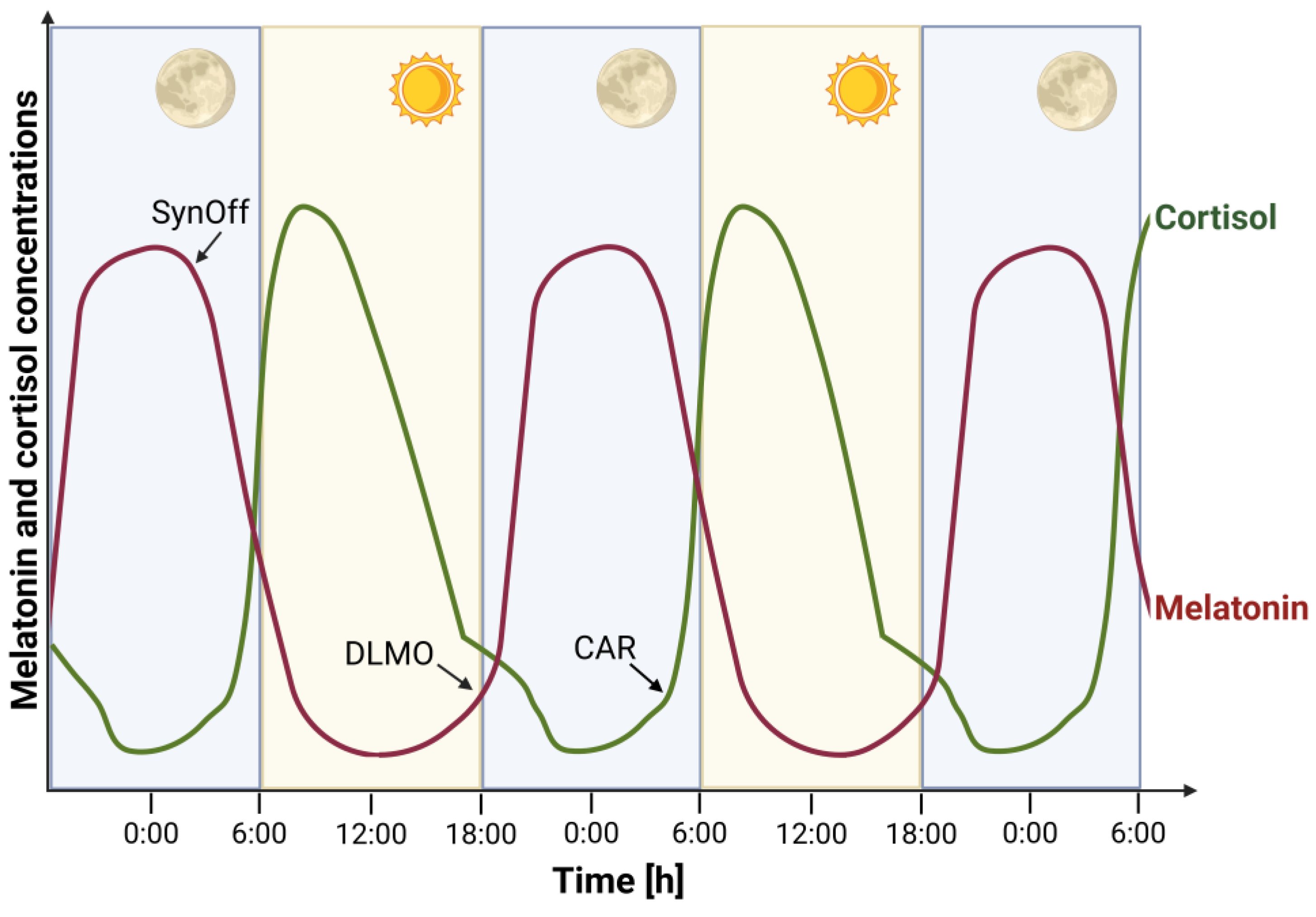

Because direct measurement of SCN activity is not feasible in humans, peripheral biomarkers such as melatonin and cortisol are commonly used as proxies for circadian phase. Melatonin, secreted by the pineal gland in response to darkness, signals the onset of the biological night (

Figure 1). Its rise under dim light conditions known as the dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO). DLMO is considered the most reliable marker of internal circadian timing [

18]. Cortisol, a glucocorticoid hormone produced by the adrenal cortex, shows a characteristic diurnal rhythm with a morning peak. The Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR), a sharp rise in cortisol levels within 30 to 45 minutes after waking, serves as an index of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity and is influenced by circadian timing, sleep quality, and psychological stress [

19]. Reliable quantification of these hormones is essential for both research and clinical applications. Saliva sampling has gained popularity due to its non-invasive nature and suitability for repeated, ambulatory measurements. However, low hormone concentrations in saliva challenge analytical sensitivity. Serum, while offering higher analyte levels and better reliability, is more invasive and logistically demanding. Traditionally, immunoassays have been used for hormone measurement, but they suffer from cross-reactivity and limited specificity which is especially problematic for low-abundance analytes like melatonin. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as a superior alternative, offering enhanced specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility for salivary and serum hormone [

20,

21].

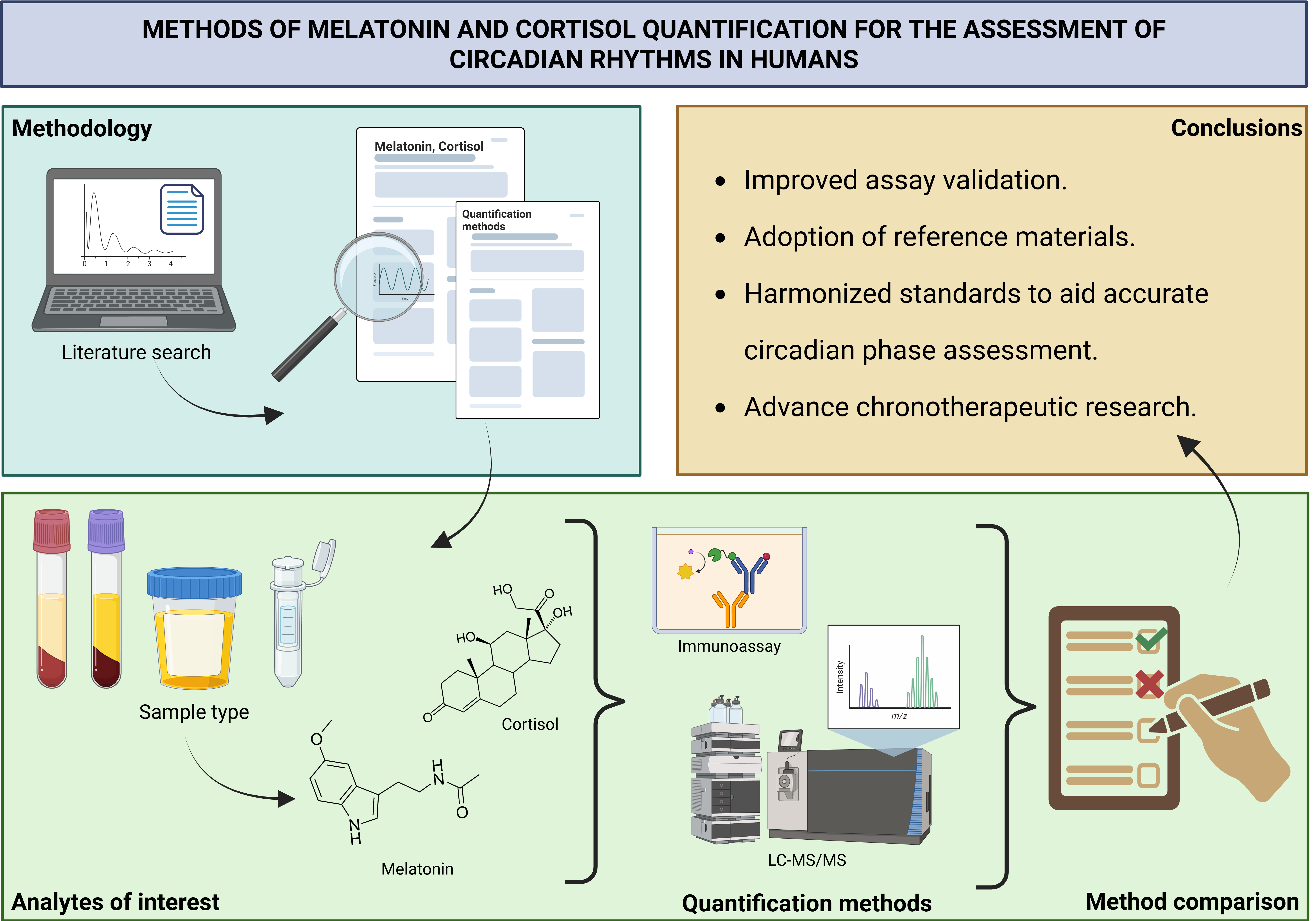

This review critically examines current methodologies for measuring melatonin and cortisol in humans, with a focus on their application in circadian rhythm assessment. By comparing traditional and advanced techniques and incorporating insights from our own research, we aim to clarify best practices and address analytical challenges. The combined use of DLMO and CAR offers a robust framework for evaluating circadian phase and stress reactivity. Reliable quantification of these biomarkers not only supports research but also enhances clinical diagnostics in the emerging field of circadian medicine.

2. Melatonin and Cortisol as Endocrine Markers of Circadian Rhythms

2.1. Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone produced by the pineal gland that promotes sleep. Its secretion follows a daily rhythm, with levels reaching nadir during the day and peaking in the early part of the night. The onset of melatonin production—DLMO—typically occurs 2–3 hours before sleep [

22] and is widely used as a marker of the phase of the endogenous circadian system.

To assess DLMO, it is usually not necessary to monitor the full 24-hour melatonin profile. Instead, a 4–6 hour sampling window, from 5 hours before to 1 hour after habitual bedtime is sufficient [

23]. The timing of sampling depends on the suspected circadian rhythm disorder (e.g., advanced sleep phase syndrome) and the age of the patient [

24,

25]. In some cases, such as in blind individuals [

26], those with irregular sleep-wake cycles, or patients with alcoholism [

27], predicting DLMO is challenging, and an extended sampling period may be necessary to ensure accurate assessment.

Several methods have been proposed to determine DLMO from partial melatonin profiles. The most commonly used is a

fixed threshold method, where DLMO is defined as the time when interpolated melatonin concentrations reach 10 pg/mL in serum or 3–4 pg/mL in saliva. Thresholds vary between studies depending on assay sensitivity and the wide inter-individual variation in melatonin production. For low producers—individuals with consistently low melatonin levels—a lower threshold such as 2 pg/mL in plasma may be applied [

21,

22].

An alternative approach uses a

dynamic threshold, defined as the time when melatonin levels exceed two standard deviations above the mean of three or more baseline (pre-rise) values [

21,

28]. While this method avoids issues with low producers, it becomes unreliable if baseline values are too few (fewer than three) or inconsistent (e.g., due to steep changes in the curve) [

29,

30].

A study comparing a variable threshold with a fixed 3 pg/mL threshold in saliva samples from 122 individuals found that the variable method produced the DLMO estimates by 22–24 minutes earlier, but closer to physiological onset in 76% of cases [

31]. A similar study favoured the fixed threshold, arguing that the variable method produced inaccurate phase estimates due to unstable baselines and thresholds falling below the assay’s functional sensitivity [

30].

For a more objective and automated assessment, Danilenko et al. [

29] developed the

“hockey-stick” algorithm, which estimates the point of change from baseline to rise in melatonin levels for both salivary and plasma samples. When compared with expert visual assessments, the algorithm showed better agreement than either fixed or dynamic threshold methods.

Besides DLMO

, melatonin synthesis offset (SynOff)—the time melatonin production ceases—can also be used as a circadian marker [

22,

32]. Unlike DLMO, SynOff is not defined by a threshold and is unaffected by amplitude. However, it requires frequent sampling across the night, which can be impractical.

Each DLMO estimation method has its strengths and limitations, and no universal standard has been established so far. The choice of method should consider the variability in sample profiles and overall melatonin levels. Wherever possible, results should be confirmed by visual inspection and, if necessary, recalculated using alternative thresholds.

Although melatonin is commonly associated with sleep, it affects nearly every organ and cell in the body [

33]. Its functions include free radical scavenging, antioxidant activity, regulation of bone formation, reproduction, cardiovascular and immune function, body mass regulation, and even cancer prevention [

34]. For instance, increased rates of breast and colorectal cancer among night shift workers suggest a possible link between reduced melatonin secretion and nocturnal light exposure [

35,

36]. Suppressed nighttime melatonin has also been reported in Alzheimer’s disease [

37,

38], autism spectrum disorder [

39], and has been discussed as an adjuvant therapy in cardiovascular disorders [

40].

Given its broad physiological roles, melatonin measurement will remain a crucial tool in future biomedical research, across a wide range of clinical disciplines.

2.2. Cortisol

It is widely known as the body’s stress hormone

, cortisol is one of the major glucocorticoids secreted by the adrenal cortex. Its circadian rhythm is roughly opposite to that of melatonin (

Figure 1), as cortisol levels peak early in the morning and reach their nadir around midnight. The onset of cortisol’s quiescent phase has been shown to be

phase-locked to melatonin onset, making it a potential marker for assessing the phase of the SCN [

41].

However, when comparing the two markers,

melatonin-based methods offer greater precision. Klerman et al. [

42] found that melatonin allows for SCN phase determination with a standard deviation (SD) of 14 to 21 minutes, whereas cortisol-based methods yielded a less precise SD of about 40 minutes. Still, melatonin assessment is not always reliable. Factors such as

sleep deprivation [

43],

melatonin supplementation, certain

antidepressants [

44], and

contraceptives [

45] can artificially elevate melatonin levels, while non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs [

18] and

some beta-blockers [

46] may suppress it.

Although cortisol is not a robust marker, it remains a valid alternative to melatonin, and a useful proxy for assessing rhythmicity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Given that LC-MS/MS enables simultaneous analysis of both cortisol and melatonin without additional cost or time, measuring both hormones provides a more comprehensive insight into circadian interactions.

Another distinctive feature of cortisol secretion is the

cortisol awakening response (CAR), a rapid increase in cortisol levels within 20–30 minutes of waking [

47]. This response is

superimposed on the circadian rise in early morning cortisol and is regulated by different mechanisms than the rest of the diurnal cortisol cycle [

48]. Evidence suggests that CAR intensity may be influenced by

psychosocial factors, such as stress and burnout, although the exact relationships remain unclear [

49]. Like the circadian cortisol rhythm, CAR is typically assessed using

salivary samples collected immediately upon waking and at set intervals over the following hour.

Precise cortisol measurement is also essential in

clinical diagnostics, particularly for conditions involving adrenal insufficiency or excess cortisol production, where a loss of normal rhythmicity is a hallmark feature [

50]. Beyond its circadian roles, cortisol plays a crucial role in

energy metabolism, cardiovascular function, respiratory regulation, blood flow redistribution, and

immune modulation [

47]. Dysregulation of cortisol rhythms has been implicated in

neurodegeneration [

51],

increased cardiovascular risk [

52], and

sleep disturbances, particularly a higher proportion of wake after sleep onset (WASO) [

53]. Thus, cortisol assessment holds value well beyond the field of circadian research.

Table 1.

Factors that may influence melatonin and cortisol measurement – masking factors.

Table 1.

Factors that may influence melatonin and cortisol measurement – masking factors.

| Change |

Melatonin |

Cortisol |

Increase

↑

|

Sleep deprivation [43,55],

certain antidepressants [44],

contraceptives [56,57],

standing position versus sitting [58,59]. |

Stress [60],

morning light (induces an immediate, greater than 50% elevation of cortisol levels – even after a sleepless night) [61], awakening [60], high protein meals [60], exercise [62], ageing (also shifts cycle), smoking before saliva collection, contamination of saliva samples with blood [63], oral contraceptives (women treated with the OCP displayed a 1.7-2.2-fold increase in total plasma cortisol levels) [64]. |

Decrease

↓

|

Light (with light at the blue end of the spectrum having the biggest impact) [65,66,67], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [18], certain beta blockers [46], nocturnal physical activity [68],

caffeine (consumed a few hours before measurement) [69], saliva collection with cotton swabs compared with that from passive saliva collection [70],

possibly reduced melatonin secretion in the luteal phase in women [71]. |

Possibly reduced amplitude of cortisol in the luteal phase in women [71].

|

Masking

↑ and ↓

|

Ethnicity/Ancestry:

Caucasian participants were found to have higher daily melatonin levels than Asians [72],

African Americans excreted less 6-sulphatoxymelatonin compared to European Americans [73].

Nevertheless, DLMO was not found to vary between races [57]. |

Ethnicity/Ancestry:

Africans and Hispanics/Latinos have flatter diurnal cortisol slopes [74].

In patients with type 2 diabetes, morning serum cortisol was shown to depend on morning fasting glycemia, while salivary cortisol did not [75]. |

2.3. Cofounding factors

Although both hormones are recognized as robust markers of central circadian phase, their measurement can be influenced by

medications, behaviors and environmental conditions, potentially compromising accuracy or rendering the results invalid (see

Table 1 for a summary of masking factors).

For example,

ambient light not only suppresses melatonin secretion but can also shift the phase of the

SCN, thereby affecting both melatonin and cortisol rhythms. Light intensities as low as

6 lux can suppress melatonin levels by up to

50% in highly light-sensitive individuals, highlighting the need to conduct assessments under

dim light conditions, typically below

30 lux [

54]. While some masking effects, like light exposure are well documented,

other influences may be more subtle yet still critical to consider for accurate assessment of circadian hormone profiles.

3. Sampling Strategies in Different Matrices

3.1. Serum or plasma

Chronobiological research has traditionally been conducted in controlled clinical settings. Participants typically receive cannulas indwelling, and blood samples are collected at regular intervals over several hours. This approach offers several advantages: it provides access to

higher concentrations of metabolites, allows for sampling

during sleep, and enables the concurrent analysis of other relevant biomarkers, including

plasma metabolites and mRNA. However, the method also has notable drawbacks. It is

invasive and burdensome for participants and may lead to

artificially elevated cortisol levels due to stress induced by hospital visits and repeated blood draws [

76]. Moreover, the procedure requires

trained medical personnel, immediate sample processing (including overnight), and

specialized infrastructure, making it both

costly and impractical for large-scale studies.

3.2. Saliva

In contrast to blood-based sampling,

salivary hormone collection is cost-effective, non-invasive, and can be performed

at home. Samples should be

stored cold or frozen until delivery. During the collection period, participants are instructed to remain in

dim light, refrain from

alcohol, caffeine, and

toothpaste use, and avoid food intake for

at least 30 minutes prior to sampling to prevent contamination with

dietary melatonin. Some protocols also recommend

rinsing the mouth with water 10–15 minutes before collection; to ensure comparability across individuals. However, this timing should be standardized [

21,

24].

Samples visibly contaminated with

blood should be discarded and recollected, as

blood contamination may artificially elevate cortisol levels [

77]. Although full compliance with these instructions cannot be guaranteed, studies have validated that

self-collected saliva samples can reliably determine

DLMO [

31,

78]. To enhance reliability,

objective monitoring of environmental illumination, for example through wearable devices, is strongly recommended [

25].

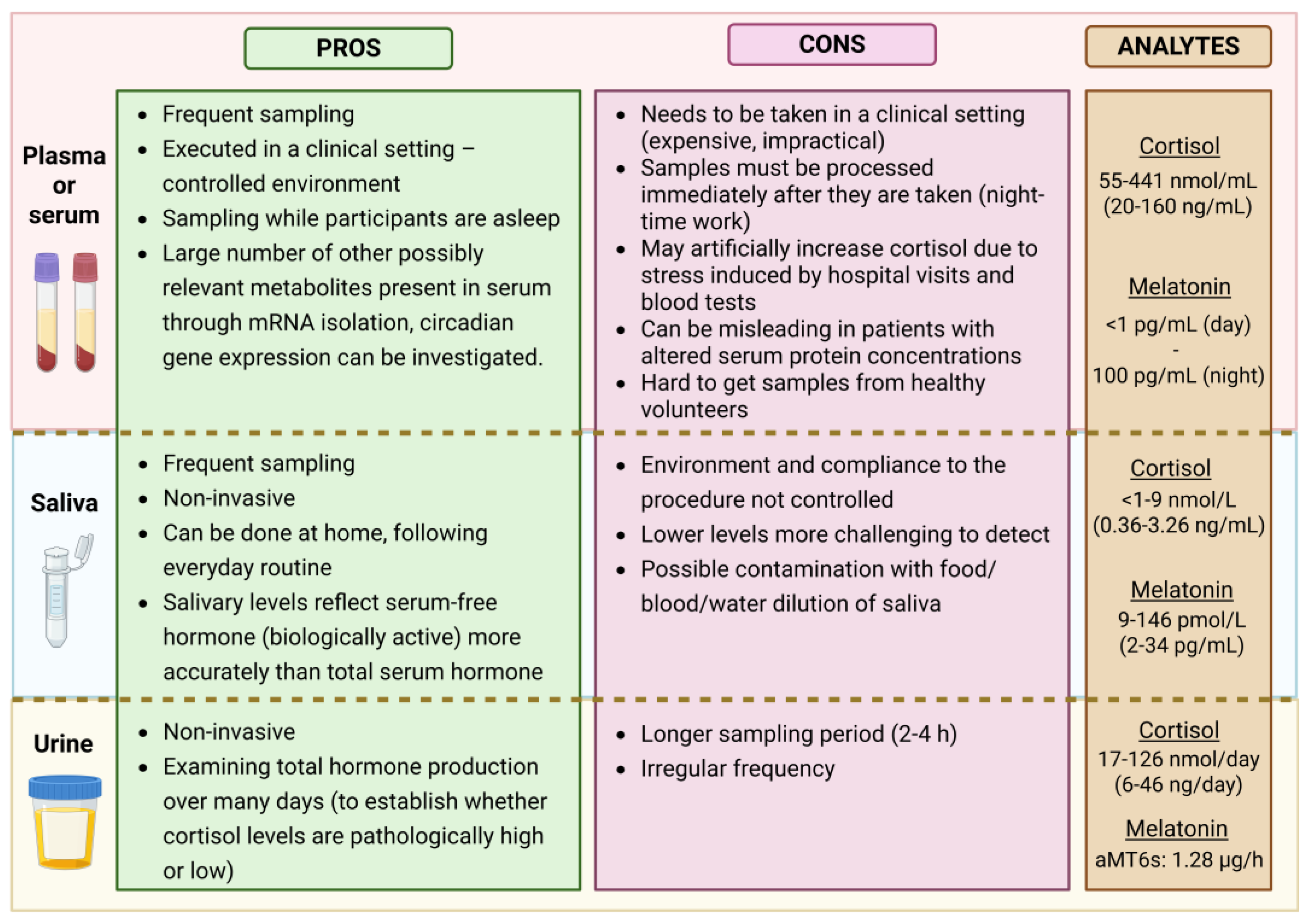

When comparing

plasma and saliva (see

Figure 2), it is important to consider that approximately

70% of melatonin and

95% of cortisol in plasma are

protein-bound. Only the

unbound (free) fraction is biologically active and capable of diffusing into other fluids such as saliva. Salivary melatonin concentrations are typically

24–33% of those found in plasma [

79], while salivary cortisol ranges between

50–70% of the free cortisol in serum [

80].

Numerous studies have shown that

salivary hormone levels reflect free serum concentrations more accurately than total serum levels over a 24-hour period, particularly in individuals with altered protein-binding capacities—such as those with

liver disease, high estrogen levels (e.g., pregnancy or contraceptive use) [

81]. Therefore, saliva is a

suitable medium for assessing circadian rhythms [

76,

79]. However, for the evaluation of

pineal or adrenal gland function, salivary concentrations

should not be extrapolated to total plasma levels [

21].

On the downside,

lower melatonin and cortisol concentrations in saliva may pose technical challenges for certain assays—especially when hormone production is at its

nadir (i.e., during the light phase for melatonin or during the night for cortisol). Titman et al. [

76] reported that in

19% of afternoon samples (after 13:00) collected from children, salivary cortisol was

undetectable. Likewise, in a study by Crowley et al. [

30], almost

half of the 66 adolescents studied had

2SD thresholds lower than the functional assay sensitivity (<0.9 pg/mL), rendering accurate analysis difficult. To address this,

careful selection of analytical methods is essential.

Measuring salivary melatonin accurately is particularly demanding due to its

low concentration. According to updated guidelines by

Kennaway [

21], only assays with a

limit of quantification (LOQ) below 3 pg/mL that can

reliably detect pre-DLMO levels are considered appropriate. Both

highly sensitive immunoassays and LC-MS methods, if properly validated, are suitable for assessing

circadian timing via saliva DLMO. This technique is especially useful for evaluating circadian responses to

jet lag, light exposure (timing and wavelength), disease, or medications.

It is important to note that single-timepoint saliva melatonin measurements have no meaningful physiological value. Furthermore, salivary melatonin should not be used to estimate total melatonin production, due to significant individual variability in plasma protein binding across different ages and health states. Assays that consistently report daytime saliva melatonin levels above 3 pg/mL should be avoided, as they likely indicate falsely elevated values, undermining the reliability of circadian research outcomes.

3.3. Urine

A small fraction—approximately 2% of unbound plasma cortisol—is excreted in the urine and can be detected as urine-free cortisol [

81]. In contrast, melatonin is assessed via its primary urinary metabolite, 6-sulfatoxymelatonin (aMT6s).

Urine sampling, like salivary sampling, is non-invasive, can be performed at home, and does not require immediate sample processing, making it a practical alternative in many research and clinical contexts. However, unlike blood or saliva sampling, it does not permit high-frequency collection or real-time tracking of hormone fluctuations. Instead, it serves as a proxy for total hormone production over an extended period, offering valuable insight into cumulative endocrine output.

This makes urinary hormone measurements particularly useful in medical diagnostics and research. For example, 24-hour urine-free cortisol is commonly used to screen for Cushing’s syndrome, a condition of cortisol excess. Studies have shown that urinary cortisol levels correlate well with mean serum-free cortisol, except in cases of severe renal impairment [

81]. Similarly, morning aMT6s concentrations have been found to correlate with sleep quality and are typically reduced in individuals with sleep disorders [

82].

Figure 2.

Comparison of different sampling options with pros and cons for each biological sample. The concentration range of analytes is also shown. Created in BioRender.

Figure 2.

Comparison of different sampling options with pros and cons for each biological sample. The concentration range of analytes is also shown. Created in BioRender.

3.4. Alternative sampling options

While blood, saliva, and urine remain the primary sources for measuring cortisol and melatonin, alternative biological matrices are increasingly being explored. A review of the literature reveals that most detection methods prioritize cortisol over melatonin, likely due to the growing interest in stress monitoring. Fingertip sweat sensors [

83,

84] and soft contact lenses [

85] have utilized selective binding approaches, either through antibodies or cortisol-imprinted electropolymerized coatings, combined with electrochemical sensing to monitor endocrine responses to stress and circadian fluctuations.

Another promising technology is the U-RHYTHM device, which is inserted subcutaneously and uses microdialysis to collect samples continuously. After retrieval, the collected dialysate can be analyzed for various metabolites and steroids, including tissue-free melatonin and cortisol [

86]. This approach enables the observation of both diurnal and ultradian rhythms, as well as their interaction and potential modulation by environmental and behavioral factors.

Although not relevant for assessing circadian rhythms, hair cortisol measurement holds significant clinical value. The procedure involves segmenting hair into sections that correspond to defined time periods, extracting cortisol, and quantifying it using standard analytical techniques [

87]. Longer hair samples can reflect cortisol production over several months to years [

88], providing insights into long-term exposure to chronic stress, as well as the temporal progression of adrenal insufficiency or Cushing’s syndrome [

87].

These alternative biomarkers, adaptable to both free-living and clinical settings, offer promising avenues for self-monitoring, research, and clinical diagnostics. However, further validation studies are essential before their widespread adoption.

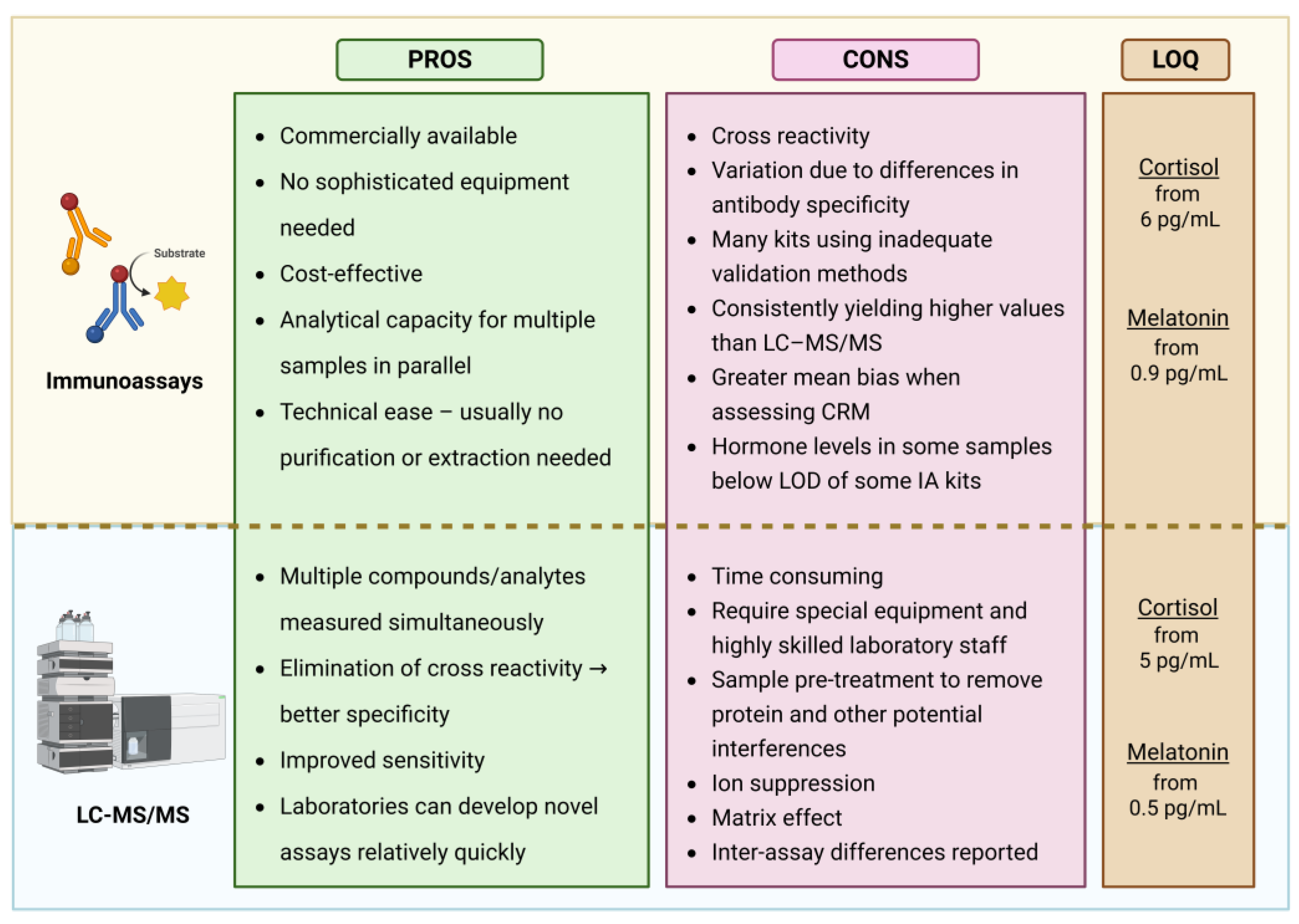

4. Analytical Techniques for Melatonin and Cortisol Quantification

Measuring melatonin and cortisol in biological samples presents two major methodological challenges: their extremely low concentrations at circadian nadirs (below 1 pg/mL for melatonin and below 1.0 ng/mL for cortisol in saliva), and the complexity of biological matrices, which often contain structurally similar interfering compounds. Although immunoassays currently dominate in routine testing, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) methods are gaining attraction—not only in research settings but increasingly in clinical laboratories—due to their superior specificity and sensitivity.

4.1. Immunoassays (IA)

The exceptional specificity of antibodies, coupled with our ability to generate them against virtually any (macro)molecule, underpins the widespread applicability of immunoassays. In these assays, antibodies are designed to selectively bind target analytes. The resulting binding is detected via an indicator molecule and quantified by comparison to a calibration curve. Immunoassays are generally classified into competitive and non-competitive. In competitive assays, the analyte in the sample competes with a labeled analogue for binding to the antibody, and the signal is inversely proportional to the analyte concentration. In contrast, non-competitive assays use labeled antibodies that bind directly to the antigen; the bound complexes are retained while unbound antibodies are washed away, and the signal is directly proportional to the analyte concentration.

For melatonin and cortisol measurements, the label may be: a radioisotope (radioimmunoassay, RIA), an enzyme that catalyzes a detectable product (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA), or a luminescent molecule (chemiluminescent or electrochemiluminescent immunoassays, CLIA or ECLIA).

The broad use of immunoassays is due to their commercial availability, affordability, minimal equipment requirements, ease of use, suitability for automation, and ability to process multiple samples simultaneously. However, one of their major limitations lies in the difficulty of producing antibodies with complete specificity. Cross-reactivity with structurally similar molecules can lead to artificially elevated readings. For instance, melatonin immunoassays may also detect serotonin, N-acetylserotonin, N-acetyl-N-formyl-5-methoxytryptamine, and 5-methoxytryptamine. Similarly, cortisol assays may cross-react with other steroids, particularly cortisone, whose concentrations can be up to three times higher than cortisol [

81]. This issue is especially pronounced at low analyte concentrations [

89].

As a result, and due to differences in assay validation, substantial discrepancies have been observed between various commercial immunoassay kits. A study comparing commonly used immunoassays with a reference LC–MS/MS method across 195 saliva samples representing the full adult cortisol range found the results to be poorly aligned [

90]. LC–MS/MS also shows that expected plasma melatonin levels during the light phase are typically 1–3 pg/mL, with salivary melatonin levels representing 30–40% of plasma concentrations. Yet, numerous studies using commercial immunoassay kits have reported melatonin levels exceeding 100 pg/mL during daylight hours, even though the pineal gland does not produce melatonin at that time. ELISA kits, which dominate the melatonin assay market, were found to show even higher daytime melatonin levels and lower sensitivity compared to RIA [

91].

In terms of sensitivity, a critical review of 21 commercial melatonin immunoassay kits concluded that many are unsuitable for accurately measuring daytime levels or determining DLMO due to insufficient sensitivity [

21,

91]. Similarly, salivary cortisol was undetectable in 19% of post-13:00 samples in children [

76] and in 30% of samples from healthy adults [

20], highlighting a comparable issue in cortisol measurement.

4.2. Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

LC–MS/MS combines the high analytical sensitivity of mass spectrometry with the powerful separation capabilities of chromatography, offering superior specificity, sensitivity, and linearity compared to immunoassays. One of its key advantages lies in the ability to distinguish between structurally similar compounds, thereby eliminating the issue of cross-reactivity. Endogenous interferences are minimal, but may include salts, especially in urine samples, and co-eluting substances that can reduce ionization efficiency [

81]. To address these challenges, a variety of sample pre-treatment and extraction techniques are employed, depending on the biological matrix and analyte of interest. The studies summarized in

Table 2 primarily utilize:

Protein precipitation (PPT) [

89,

92,

93]

Liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) [

20,

94,

95], and

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) [

92,

96,

97,

98].

While PPT is the simplest and fastest method, LLE and especially SPE offer greater purification but are more technically demanding, time-consuming, and costly. These limitations make them less suitable for high-throughput clinical settings [

93].

A significant advantage of LC–MS/MS is its ability to simultaneously quantify multiple analytes. Several validated protocols allow for the concurrent measurement of salivary [

20,

94] and plasma [

97] melatonin and cortisol. However, unlike immunoassays, LC–MS/MS lacks parallel processing capacity, making it inherently slower. Furthermore, it requires costly instrumentation and highly trained personnel, which limits its widespread use in clinical and routine laboratory settings despite its analytical superiority.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) is another highly sensitive and accurate technique capable of detecting low levels of cortisol and melatonin. However, its application is constrained by the need to derivatize non-volatile compounds before analysis [

93], resulting in a labor-intensive and lower-throughput workflow. Consequently, GC–MS remains largely restricted to specialized research and reference laboratories [

81].

Table 2.

Comparison between LC-MS/MS and immunoassays for measuring melatonin or cortisol.

Table 2.

Comparison between LC-MS/MS and immunoassays for measuring melatonin or cortisol.

| Reference |

What Did They Compare? |

Conclusion |

| Shin et al., 2021, [20] |

LC-MS/MS vs. ELISA (melatonin) and ECLIA (cortisol) in 121 salivary samples from healthy subjects. |

Strong correlation (r=0.910 for melatonin, r=0.955 for cortisol), but IA showed significant positive bias; 30% of cortisol samples fell below ECLIA LLOQ; LC-MS/MS required less sample volume. |

| Karel et al., 2021, [98]

|

Two LC-MS/MS methods and RIA (Bühlmann) on salivary melatonin from 39 patients. |

LC-MS/MS methods showed strong agreement (r=0.99); RIA had greater variance (r=0.74, mean bias -11.7%). LC-MS/MS was superior in precision and trueness. |

| van Faassen et al., 2017,[97]

|

ELISA vs. LC-MS/MS on 35 salivary melatonin samples. |

Good agreement in low range; above 30 pmol/L, ELISA underestimates. Mean bias 7.9 pmol/L. Calibration difference excluded as source. |

| Oßwald et al., 2019, [99]

|

Two CLIA (ADVIA, LIAISON) vs. LC-MS/MS on 24-h urinary cortisol in 174 patients. |

Strong correlation overall; discrepancies at high cortisol (>500 µg/mL), with IA reading 2–9× higher than LC-MS/MS. |

| Bae et al., 2016, [92]

|

IA vs. LC-MS/MS on 2703 salivary cortisol samples from children |

IA measured values ~2.39× higher. Cross-reactivity with cortisone affected results <5 nmol/L. Over 50% of samples were in this range. |

| Mészáros et al., 2018, [89]

|

ECLIA vs. LC-MS/MS on 324 late-night salivary cortisol samples. |

High correlation (r²=0.892), but high bias at low concentrations. 68.8% of reference samples were under ECLIA detection limit. |

| Hawley & Keevi, [93] |

Routine immunoassays and LC-MS/MS vs. cRMP in serum cortisol across multiple cohorts. |

LC-MS/MS closely matched cRMP. IA results varied by cohort: underestimation in pregnancy, overestimation in metyrapone/prednisolone groups. |

| Grassi et al., 2020, [96]

|

ECLIA (Cortisol I & II) vs. LC-MS/MS on stimulated serum cortisol. |

Cortisol II showed small bias (~4% lower); Cortisol I overestimated by ~36%. LC-MS/MS supports lower diagnostic cutoffs. |

| Jensen et al., 2014, [94]

|

ELISA, RIA, and LC-MS/MS in inter-laboratory salivary melatonin and cortisol comparison. |

High inter-lab variability. ELISA overestimated melatonin (6.90 vs. 0.278 pmol/L). LC-MS/MS results varied among labs. |

| Raff & Phillips, 2019, [95]

|

EIA vs. LC-MS/MS on salivary cortisol (bedtime and morning) in 53 subjects. |

Excellent correlation (r²=0.97); LC-MS/MS consistently yielded lower values, likely due to reduced cross-reactivity. |

4.3. Comparison of immunoassay and LC-MS/MS methods

An analysis of research comparing immunoassays and LC–MS/MS (

Figure 3) reveals that most studies focus on cortisol quantification, primarily to establish diagnostic cut-off values for cortisol excess or deficiency. To provide context and highlight broader trends, some earlier melatonin studies are also included.

The literature agrees that LC–MS/MS and immunoassays generally show good correlation, indicating that both methods are capable of tracking circadian rhythms. However, a consistent finding across studies is that immunoassays tend to yield higher analyte concentrations, regardless of the fluid type or whether cortisol or melatonin is being measured. This discrepancy is most often attributed to variations in assay validation and to antibody cross-reactivity with structurally similar compounds. Although sample purification via column chromatography or solvent extraction can improve specificity, most commercially available immunoassay kits now rely on direct measurement without any pre-treatment, making them more susceptible to cross-reactivity.

In melatonin studies, substantial mean biases have been reported: 49% [

20], 12% [

98], and 1.7 pg/mL [

97]. These deviations challenge the reliability of using fixed thresholds, such as the commonly applied 10 pg/mL cut-off for determining DLMO. Similarly, marked variability in cortisol measurements between assays necessitates assay-specific interpretation of results. Diagnostic cut-offs for adrenal insufficiency or hypercortisolism must be individually validated in each laboratory to ensure diagnostic accuracy and avoid misclassification.

While correlations between immunoassays and LC–MS/MS may be good on average, their ratio is not constant across the full measurement range. Notable discrepancies occur at higher concentrations. For example, ELISA was found to underestimate salivary melatonin levels above 30 pmol/L (7 pg/mL) compared to LC–MS/MS [

97]. In urinary cortisol measurements, concentrations above 500 µg/mL showed similar divergence [

99]. Conversely, at low cortisol levels (below 5 nmol/L: 1.8 ng/mL) the cross-reactivity with cortisone increasingly skews immunoassay readings [

92]. This is particularly problematic in saliva, where cortisone levels may be several-fold higher than cortisol. Even small degrees of cross-reactivity can result in significant overestimation of cortisol when the interfering compound is present in large excess.

Additionally, in physiological states associated with elevated cortisol-binding globulin (CBG), such as pregnancy, immunoassays tend to underestimate total cortisol at higher concentrations. This may result from incomplete displacement of cortisol from its binding proteins during sample processing. Such limitations can be addressed either by measuring salivary cortisol, which reflects free hormone levels and is less affected by CBG, or by using LC–MS/MS. Notably, Hawley et al. [

93] reported only a 1.4% mean bias in LC–MS/MS compared to a candidate reference method.

Another significant limitation of immunoassays is their reduced sensitivity at low hormone levels. Two studies on salivary cortisol found that a large proportion of late-night samples fell below the limit of quantification: 30% in healthy adults [

20] and 69% in children [

89]. This poses a challenge for circadian studies aiming to characterize 24-hour hormone profiles, determine cortisol quiescence periods, or define DLMO using dynamic thresholds. The issue is especially pronounced in pediatric populations, who naturally exhibit lower salivary cortisol and melatonin concentrations.

5. Determination of DLMO and CAR in Pediatric Population with Psychiatric Disorders

In children with conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and epilepsy, circadian rhythm disruptions are prevalent and often linked to sleep disturbances, behavioral dysregulation, and seizure susceptibility. Studies have demonstrated altered melatonin and cortisol secretion profiles in children with ASD, ADHD and epilepsy, supporting the clinical utility in diagnosis and treatment planning.

Therefore, these pediatric populations would benefit greatly from the implementation of a quick and efficient method for the determination of DLMO [

100] to inform the timing of pharmacological interventions (e.g., melatonin supplementation, corticosteroids) and behavioral therapies. Different studies [

78,

101,

102] have already shown feasible and accurate results using different self-directed in-home DLMO saliva collection kits for immunoassays or LC-MS/MS, that can serve to assess circadian phase in different populations. These approaches could be very beneficial for children with neurological disorders, because there is no need to visit the clinic for the collection of saliva. In addition, appropriate melatonin profiling is needed to avoid the overuse of antiepileptic drug use by melatonin supplementation when needed [

103] or for treating primary sleep disorders and the sleep disorders associated with different neurological conditions [

104].

Recommendations for standardized protocols

No matter which essay is used, standardized protocols are essential to ensure accuracy, reproducibility and comparability across studies and clinical applications. Therefore, we are proposing recommendations for standardized protocols for LC/MS-MS and immunoassay methods in

Table 3.

6. Conclusions

Accurate quantification of melatonin and cortisol is essential for reliable assessment of circadian rhythms in humans. This review highlights how the choice of measurement strategy influences the utility of these hormones as biomarkers of circadian timing. Melatonin marks the onset of the biological night, typically defined by the DLMO, while cortisol reflects the circadian wake-up signal, known as the cortisol awakening response (CAR).

Different biological matrices—blood, saliva, and urine—each offer distinct advantages and limitations depending on the analyte, sampling frequency, study design, and whether the setting is clinical or non-clinical. In addition, environmental and behavioral factors, sampling timing, and analytical sensitivity must all be carefully considered, as they can significantly influence the measured concentrations.

Two main analytical approaches are used: immunoassays and LC–MS/MS. Immunoassays are widely accessible, cost-effective, and operationally simple, making them suitable for many clinical and research contexts. However, they are prone to cross-reactivity and variability across commercial kits, which can compromise specificity and accuracy. In contrast, LC–MS/MS provides superior analytical performance, with higher specificity, sensitivity, and the ability to distinguish structurally related compounds. These advantages make it the preferred method in circadian and endocrine research, despite its higher cost, technical complexity, and limited accessibility.

Ultimately, the choice between immunoassay and LC–MS/MS should be guided by the specific research objectives, required analytical precision, available resources and the context of application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R and C.S.; literature review, U.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, U.Z. and C.S; writing review and editing, C.S., K.N and D.R.; visualization, K.N.; clinical implication, L.D.G.; supervision, D.R. and L.D.G.; funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This work was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) program grants P1-0390, IP-022 MRIC-Elixir, MRIC-CFGBC and project grant J1-50024.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT, based on OpenAI’s GPT-4-turbo model (accessed via chat.openai.com), for the purposes of text editing and English language refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DLMO |

Dim light melatonin onset |

| CAR |

Cortisol awakening response |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| MRM |

Multiple reaction monitoring |

| LOQ |

Limit of quantification |

| SCN |

The suprachiasmatic nucleus |

| RIA |

Radioimmunoassay |

| PPT |

Protein precipitation |

| LLE |

Liquid–liquid extraction |

| SPE |

Solid-phase extraction |

| GC-MS |

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| ASD |

Autism spectrum disorder |

| ADHD |

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| WASO |

Wake after sleep onset |

References

- Partch, C.L.; Green, C.B.; Takahashi, J.S. Molecular Architecture of the Mammalian Circadian Clock. Trends in Cell Biology 2014, 24, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlman, S.J.; Craig, L.M.; Duffy, J.F. Introduction to Chronobiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018, 10, a033613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korenčič, A.; Košir, R.; Bordyugov, G.; Lehmann, R.; Rozman, D.; Herzel, H. Timing of Circadian Genes in Mammalian Tissues. Scientific Reports 2014, 4, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiani, F.; Di Marino, D.; Romagnoli, A.; Travelli, C.; Voltan, D.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Racchi, M.; Govoni, S.; Lanni, C. Molecular Regulations of Circadian Rhythm and Implications for Physiology and Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videnovic, A.; Lazar, A.S.; Barker, R.A.; Overeem, S. ’The Clocks That Time Us’--Circadian Rhythms in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2014, 10, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, S.; Sassone-Corsi, P. The Emerging Link between Cancer, Metabolism, and Circadian Rhythms. Nat Med 2018, 24, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, U.; Skubic, C.; Bohinc, L.; Rozman, D.; Režen, T. Oxysterols and Gastrointestinal Cancers Around the Clock. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J.; Purvis, T.E.; Mistretta, J.; Scheer, F.A.J.L. Effects of the Internal Circadian System and Circadian Misalignment on Glucose Tolerance in Chronic Shift Workers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016, 101, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maemura, K.; Takeda, N.; Nagai, R. Circadian Rhythms in the CNS and Peripheral Clock Disorders: Role of the Biological Clock in Cardiovascular Diseases. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2007, 103, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombali, A.; Seow, E.; Yuan, Q.; Chang, S.H.S.; Satghare, P.; Kumar, S.; Verma, S.K.; Mok, Y.M.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. Prevalence and Correlates of Sleep Disorder Symptoms in Psychiatric Disorders. Psychiatry Res 2019, 279, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plavc, L.; Skubic, C.; Dolenc Grošelj, L.; Rozman, D. Variants in the Circadian Clock Genes PER2 and PER3 Associate with Familial Sleep Phase Disorders. Chronobiol Int 2024, 41, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn-Evans, E.E.; Shekleton, J.A.; Miller, B.; Epstein, L.J.; Kirsch, D.; Brogna, L.A.; Burke, L.M.; Bremer, E.; Murray, J.M.; Gehrman, P.; et al. Circadian Phase and Phase Angle Disorders in Primary Insomnia. Sleep 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmer, B.; Scholtze, J.; Schmitt, J. Circadian Rhythms in Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, Hormones, and on Polysomnographic Parameters in Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome Patients: Effect of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure. Blood Press Monit 2016, 21, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmon, J.; Kočar, E.; Pintar, T.; Dolenc-Grošelj, L.; Rozman, D. Is Obstructive Sleep Apnea a Circadian Rhythm Disorder? J Sleep Res 2023, 32, e13875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmrzljak, U.P.; Rozman, D. Circadian Regulation of the Hepatic Endobiotic and Xenobitoic Detoxification Pathways: The Time Matters. Chem Res Toxicol 2012, 25, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyar, A.; Ozturk Civelek, Dilek; Akyel, Yasemin Kubra; Surme, Saliha; Pala Kara, Zeliha; and Kavakli, İ.H. The Role of the Circadian Timing System on Drug Metabolism and Detoxification: An Update. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology 2024, 20, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.C.; Walker, W.H.; Bumgarner, J.R.; Meléndez-Fernández, O.H.; Liu, J.A.; Hughes, H.L.; Kaper, A.L.; Nelson, R.J. Circadian Variation in Efficacy of Medications. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 2021, 109, 1457–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K.J. Assessment of Circadian Rhythms. Neurologic Clinics 2019, 37, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clow, A.; Hucklebridge, F.; Stalder, T.; Evans, P.; Thorn, L. The Cortisol Awakening Response: More than a Measure of HPA Axis Function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010, 35, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Oh, H.; Park, H.R.; Joo, E.Y.; Lee, S.-Y. A Sensitive and Specific Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay for Simultaneous Quantification of Salivary Melatonin and Cortisol: Development and Comparison With Immunoassays. Ann Lab Med 2021, 41, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennaway, D.J. The Appropriate and Inappropriate Uses of Saliva Melatonin Measurements. Chronobiology International 2024, 41, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewy, A.J.; Cutler, N.L.; Sack, R.L. The Endogenous Melatonin Profile as a Marker for Circadian Phase Position. J Biol Rhythms 1999, 14, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Choi, S.J.; Song, Y.M.; Park, H.R.; Joo, E.Y.; Kim, J.K. Enhanced Circadian Phase Tracking: A 5-h DLMO Sampling Protocol Using Wearable Data. J Biol Rhythms 2025, 07487304251317577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Srinivasan, V.; Spence, D.W.; Cardinali, D.P. Role of the Melatonin System in the Control of Sleep: Therapeutic Implications. CNS Drugs 2007, 21, 995–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, H.J.; Emens, J.S. Circadian-Based Therapies for Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders. Curr Sleep Med Rep 2016, 2, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, R.L.; Brandes, R.W.; Kendall, A.R.; Lewy, A.J. Entrainment of Free-Running Circadian Rhythms by Melatonin in Blind People. N Engl J Med 2000, 343, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyrel, M.; Rolland, B.; Geoffroy, P.A. Alterations in Circadian Rhythms Following Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2020, 99, 109831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voultsios, A.; Kennaway, D.J.; Dawson, D. Salivary Melatonin as a Circadian Phase Marker: Validation and Comparison to Plasma Melatonin. J Biol Rhythms 1997, 12, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilenko, K.V.; Verevkin, E.G.; Antyufeev, V.S.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Cajochen, C. The Hockey-Stick Method to Estimate Evening Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO) in Humans. Chronobiol Int 2014, 31, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.J.; Suh, C.; Molina, T.A.; Fogg, L.F.; Sharkey, K.M.; Carskadon, M.A. Estimating the Dim Light Melatonin Onset of Adolescents within a 6-h Sampling Window: The Impact of Sampling Rate and Threshold Method. Sleep Med 2016, 20, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, T.A.; Burgess, H.J. Calculating the Dim Light Melatonin Onset: The Impact of Threshold and Sampling Rate. Chronobiol Int 2011, 28, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grima, N.A.; Ponsford, J.L.; St. Hilaire, M.A.; Mansfield, D.; Rajaratnam, S.M. Circadian Melatonin Rhythm Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2016, 30, 972–977. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.-X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an Antioxidant: Under Promises but over Delivers. J Pineal Res 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordjman, S.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Charrier, A.; Bellissant, E.; Jaafari, N.; Fougerou, C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolensky, M.H.; Sackett-Lundeen, L.L.; Portaluppi, F. Nocturnal Light Pollution and Underexposure to Daytime Sunlight: Complementary Mechanisms of Circadian Disruption and Related Diseases. Chronobiol Int 2015, 32, 1029–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Spence, D.W.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Trakht, I.; Cardinali, D.P. Jet Lag: Therapeutic Use of Melatonin and Possible Application of Melatonin Analogs. Travel Med Infect Dis 2008, 6, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nous, A.; Engelborghs, S.; Smolders, I. Melatonin Levels in the Alzheimer’s Disease Continuum: A Systematic Review. Alzheimers Res Ther 2021, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xue, P.; Bendlin, B.B.; Zetterberg, H.; De Felice, F.; Tan, X.; Benedict, C. Melatonin: A Potential Nighttime Guardian against Alzheimer’s. Mol Psychiatry 2025, 30, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira Cruz-Machado, S.; Guissoni Campos, L.M.; Fadini, C.C.; Anderson, G.; Markus, R.P.; Pinato, L. Disrupted Nocturnal Melatonin in Autism: Association with Tumor Necrosis Factor and Sleep Disturbances. J Pineal Res 2021, 70, e12715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Tang, Y.Y.; Zhou, L. Melatonin as an Adjunctive Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease Management. Sci Prog 2024, 107, 368504241299993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibel, L.; Brandenberger, G. The Start of the Quiescent Period of Cortisol Remains Phase Locked to the Melatonin Onset despite Circadian Phase Alterations in Humans Working the Night Schedule. Neurosci Lett 2002, 318, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klerman, E.B.; Gershengorn, H.B.; Duffy, J.F.; Kronauer, R.E. Comparisons of the Variability of Three Markers of the Human Circadian Pacemaker. J Biol Rhythms 2002, 17, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honma, A.; Revell, V.L.; Gunn, P.J.; Davies, S.K.; Middleton, B.; Raynaud, F.I.; Skene, D.J. Effect of Acute Total Sleep Deprivation on Plasma Melatonin, Cortisol and Metabolite Rhythms in Females. Eur J Neurosci 2020, 51, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, L.; Gorenstein, C.; Moreno, R.; Pariante, C.; Markus, R. Effect of Antidepressants on Melatonin Metabolite in Depressed Patients. J Psychopharmacol 2009, 23, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, H.J.; Fogg, L.F. Individual Differences in the Amount and Timing of Salivary Melatonin Secretion. PLoS One 2008, 3, e3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoschitzky, K.; Sakotnik, A.; Lercher, P.; Zweiker, R.; Maier, R.; Liebmann, P.; Lindner, W. Influence of Beta-Blockers on Melatonin Release. E J Clin Pharmacol 1999, 55, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, E.; Dettenborn, L.; Kirschbaum, C. The Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR): Facts and Future Directions. Int J Psychophysiol 2009, 72, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwinski, B.; Salavecz, G.; Kirschbaum, C.; Steptoe, A. Associations between Hair Cortisol Concentration, Income, Income Dynamics and Status Incongruity in Healthy Middle-Aged Women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 67, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, Y.; Steptoe, A. Cortisol Awakening Response and Psychosocial Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol Psychol 2009, 80, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, L.K.; Biller, B.M.K.; Findling, J.W.; Murad, M.H.; Newell-Price, J.; Savage, M.O.; Tabarin, A. Treatment of Cushing’s Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2015, 100, 2807–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouanes, S.; Popp, J. High Cortisol and the Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of the Literature. Front Aging Neurosci 2019, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Azmi, N.A.; Juliana, N.; Azmani, S.; Mohd Effendy, N.; Abu, I.F.; Mohd Fahmi Teng, N.I.; Das, S. Cortisol on Circadian Rhythm and Its Effect on Cardiovascular System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onton, J.; Le, L.D. Amount of < 1Hz Deep Sleep Correlates with Melatonin Dose in Military Veterans with PTSD. Neurobiol Sleep Circadian Rhythms 2021, 11, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.J.K.; Vidafar, P.; Burns, A.C.; McGlashan, E.M.; Anderson, C.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Lockley, S.W.; Cain, S.W. High Sensitivity and Interindividual Variability in the Response of the Human Circadian System to Evening Light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 12019–12024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitzer, J.M.; Duffy, J.F.; Lockley, S.W.; Dijk, D.-J.; Czeisler, C.A. Plasma Melatonin Rhythms In Young and Older Humans During Sleep, Sleep Deprivation, and Wake. Sleep 2007, 30, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinberg, A.E.; Touitou, Y.; Soudant, É.; Bernard, D.; Bazin, R.; Mechkouri, M. Oral Contraceptives Alter Circadian Rhythm Parameters of Cortisol, Melatonin, Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, Skin Blood Flow, Transepidermal Water Loss, and Skin Amino Acids of Healthy Young Women. Chronobiology International 1996, 13, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, H.J.; Fogg, L.F. Individual Differences in the Amount and Timing of Salivary Melatonin Secretion. PLOS ONE 2008, 3, e3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, S.; Arendt, J. Posture Influences Melatonin Concentrations in Plasma and Saliva in Humans. Neuroscience Letters 1994, 167, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozaki, T.; Arata, T.; Kubokawa, A. Salivary Melatonin Concentrations in a Sitting and a Standing Position. Journal of Hormones 2013, 2013, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstra, W.A.; de Weerd, A.W. How to Assess Circadian Rhythm in Humans: A Review of Literature. Epilepsy & Behavior 2008, 13, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leproult, R.; Colecchia, E.F.; L’Hermite-Balériaux, M.; Van Cauter, E. Transition from Dim to Bright Light in the Morning Induces an Immediate Elevation of Cortisol Levels1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2001, 86, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, M.; Dhahbi, W.; Hayes, L.D.; Kuvacic, G.; Milic, M.; Padulo, J. The Effect of Acute and Chronic Exercise on Steroid Hormone Fluctuations in Young and Middle-Aged Men. Steroids 2018, 132, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baid, S.K.; Sinaii, N.; Wade, M.; Rubino, D.; Nieman, L.K. Radioimmunoassay and Tandem Mass Spectrometry Measurement of Bedtime Salivary Cortisol Levels: A Comparison of Assays to Establish Hypercortisolism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2007, 92, 3102–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Farhan, N.; Pickett, A.; Ducroq, D.; Bailey, C.; Mitchem, K.; Morgan, N.; Armston, A.; Jones, L.; Evans, C.; Rees, D.A. Method-Specific Serum Cortisol Responses to the Adrenocorticotrophin Test: Comparison of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and Five Automated Immunoassays. Clinical Endocrinology 2013, 78, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Steiner, R.; Blattner, P.; Oelhafen, P.; Götz, T.; Cajochen, C. Non-Visual Effects of Light on Melatonin, Alertness and Cognitive Performance: Can Blue-Enriched Light Keep Us Alert? PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e16429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; Wright, K.P.; Lockley, S.W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Gronfier, C. Characterizing the Temporal Dynamics of Melatonin and Cortisol Changes in Response to Nocturnal Light Exposure. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 19720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, H.R.; Lack, L.C. Effect of Light Wavelength on Suppression and Phase Delay of the Melatonin Rhythm. Chronobiol Int 2001, 18, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P.; Maj, M.; Fusco, M.; Orazzo, C.; Kemali, D. Physical Exercise at Night Blunts the Nocturnal Increase of Plasma Melatonin Levels in Healthy Humans. Life Sciences 1990, 47, 1989–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilo, L.; Sabbah, H.; Hadari, R.; Kovatz, S.; Weinberg, U.; Dolev, S.; Dagan, Y.; Shenkman, L. The Effects of Coffee Consumption on Sleep and Melatonin Secretion. Sleep Medicine 2002, 3, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozaki, T.; Lee, S.; Nishimura, T.; Katsuura, T.; Yasukouchi, A. Effects of Saliva Collection Using Cotton Swabs on Melatonin Enzyme Immunoassay. Journal of Circadian Rhythms 2011, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.C.; Driver, H.S. Circadian Rhythms, Sleep, and the Menstrual Cycle. Sleep Medicine 2007, 8, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, P.; Mirick, D.K.; Davis, S. Racial Differences in the Association Between Night Shift Work and Melatonin Levels Among Women. American Journal of Epidemiology 2013, 177, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Harris, R.; Dong, Y.; Su, S.; Tingen, M.; Kapuku, G.; Pollock, J.; Pollock, D.; Harshfield, G. Ethnic Difference in Nighttime Melatonin Can Partially Explain the Ethnic Difference in Nighttime Blood Pressure: A Study in European Americans and African Americans. The FASEB Journal 2019, 33, 533.15–533.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, A.S.; Adam, E.K.; Hawkley, L.C.; Kudielka, B.M.; Cacioppo, J.T. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Diurnal Cortisol Rhythms: Are They Consistent Over Time? Psychosomatic Medicine 2015, 77, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellastella, G.; Maiorino, M.I.; De Bellis, A.; Vietri, M.T.; Mosca, C.; Scappaticcio, L.; Pasquali, D.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D. Serum but Not Salivary Cortisol Levels Are Influenced by Daily Glycemic Oscillations in Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrine 2016, 53, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, A.; Price, V.; Hawcutt, D.; Chesters, C.; Ali, M.; Cacace, G.; Lancaster, G.A.; Peak, M.; Blair, J.C. Salivary Cortisol, Cortisone and Serum Cortisol Concentrations Are Related to Age and Body Mass Index in Healthy Children and Young People. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2020, 93, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashman, S.B.; Dawson, G.; Panagiotides, H.; Yamada, E.; Wilkinson, C.W. Stress Hormone Levels of Children of Depressed Mothers. Dev Psychopathol 2002, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullman, R.E.; Roepke, S.E.; Duffy, J.F. Laboratory Validation of an In-Home Method for Assessing Circadian Phase Using Dim Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO). Sleep Med 2012, 13, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutando, A.; Gómez-Moreno, G.; Arana, C.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin: Potential Functions in the Oral Cavity. Journal of Periodontology 2007, 78, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulenberg, P.M.; Hofman, J.A. Differences between Concentrations of Salivary Cortisol and Cortisone and of Free Cortisol and Cortisone in Plasma during Pregnancy and Postpartum. Clin Chem 1990, 36, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Farhan, N.; Rees, D.A.; Evans, C. Measuring Cortisol in Serum, Urine and Saliva - Are Our Assays Good Enough? Ann Clin Biochem 2017, 54, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, G.D.; Reid, K.J.; Ferguson, S.; Dawson, D. The Relationship between the Rate of Melatonin Excretion and Sleep Consolidation for Locomotive Engineers in Natural Sleep Settings. J Circadian Rhythms 2006, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Tu, J.; Yang, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, M.; Song, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xu, C.; Ye, C.; IsHak, W.W.; et al. Investigation of Cortisol Dynamics in Human Sweat Using a Graphene-Based Wireless mHealth System. Matter 2020, 2, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Yin, L.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Moon, J.-M.; Teymourian, H.; Wang, J. Touch-Based Stressless Cortisol Sensing. Adv Mater 2021, 33, e2008465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, M.; Kim, J.; Won, J.-E.; Kang, W.; Park, Y.-G.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Cheon, J.; Lee, H.H.; Park, J.-U. Smart, Soft Contact Lens for Wireless Immunosensing of Cortisol. Science Advances 6, eabb2891. [CrossRef]

- Isherwood, C.M.; van der Veen, D.R.; Chowdhury, N.R.; Lightman, S.T.; Upton, T.J.; Skene, D.J. Simultaneous Plasma and Interstitial Profiles of Hormones and Metabolites Using URHYTHM: A Novel Ambulatory Collection Device. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2024, 83, E242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, M.J.E.; Levine, J.M.; Abuzgaia, A.M.; Elzagallaai, A.A.; Rieder, M.J.; van Uum, S.H.M. Hair Cortisol Analysis: An Update on Methodological Considerations and Clinical Applications. Clin Biochem 2019, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, R.; Koren, G.; Rieder, M.; Van Uum, S. Hair Cortisol Content in Patients with Adrenal Insufficiency on Hydrocortisone Replacement Therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011, 74, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, K.; Karvaly, G.; Márta, Z.; Magda, B.; Tőke, J.; Szücs, N.; Tóth, M.; Rácz, K.; Patócs, A. Diagnostic Performance of a Newly Developed Salivary Cortisol and Cortisone Measurement Using an LC–MS/MS Method with Simple and Rapid Sample Preparation. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2018, 41, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Plessow, F.; Kirschbaum, C.; Stalder, T. Classification Criteria for Distinguishing Cortisol Responders from Nonresponders to Psychosocial Stress: Evaluation of Salivary Cortisol Pulse Detection in Panel Designs. Psychosom Med 2013, 75, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennaway, D.J. Measuring Melatonin by Immunoassay. J Pineal Res 2020, 69, e12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.J.; Gaudl, A.; Jaeger, S.; Stadelmann, S.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Willenberg, A.; Schaab, M.; von Klitzing, K.; Thiery, J.; et al. Immunoassay or LC-MS/MS for the Measurement of Salivary Cortisol in Children? Clin Chem Lab Med 2016, 54, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, J.M.; Keevil, B.G. Endogenous Glucocorticoid Analysis by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry in Routine Clinical Laboratories. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2016, 162, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.A.; Mortier, L.; Koh, E.; Keevil, B.; Hyttinen, S.; Hansen, Å.M. An Interlaboratory Comparison between Similar Methods for Determination of Melatonin, Cortisol and Testosterone in Saliva. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2014, 74, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, H.; Phillips, J.M. Bedtime Salivary Cortisol and Cortisone by LC-MS/MS in Healthy Adult Subjects: Evaluation of Sampling Time. J Endocr Soc 2019, 3, 1631–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, G.; Morelli, V.; Ceriotti, F.; Polledri, E.; Fustinoni, S.; D’Agostino, S.; Mantovani, G.; Chiodini, I.; Arosio, M. Minding the Gap between Cortisol Levels Measured with Second-Generation Assays and Current Diagnostic Thresholds for the Diagnosis of Adrenal Insufficiency: A Single-Center Experience. Hormones (Athens) 2020, 19, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Faassen, M.; Bischoff, R.; Kema, I.P. Relationship between Plasma and Salivary Melatonin and Cortisol Investigated by LC-MS/MS. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017, 55, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karel, P.; Schutten, E.; van Faassen, M.; Wanschers, H.; Brouwer, R.; Mulder, A.L.; Kema, I.P.; Reichman, L.J.; Krabbe, J.G. A Comparison of Two LC-MS/MS Methods and One Radioimmunoassay for the Analysis of Salivary Melatonin. Ann Clin Biochem 2021, 58, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oßwald, A.; Wang, R.; Beuschlein, F.; Hartmann, M.F.; Wudy, S.A.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Zopp, S.; Reincke, M.; Ritzel, K. Performance of LC-MS/MS and Immunoassay Based 24-h Urine Free Cortisol in the Diagnosis of Cushing’s Syndrome. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2019, 190, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennaway, D.J. The Dim Light Melatonin Onset across Ages, Methodologies, and Sex and Its Relationship with Morningness/Eveningness. Sleep 2023, 46, zsad033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormes, G.; Love, J.; Akeju, O.; Cherry, J.; Kunorozva, L.; Qadri, S.; Rahman, S.A.; Westover, B.; Winkelman, J.; Lane, J.M. Self-Directed Home-Based Dim-Light Melatonin Onset Collection: The Circadia Pilot Study. medRxiv : the preprint server for health sciences 2023, 2023.05.26.23290467.

- Mandrell, B.N.; Avent, Y.; Walker, B.; Loew, M.; Tynes, B.L.; Crabtree, V.M. In-Home Salivary Melatonin Collection: Methodology for Children and Adolescents. Dev Psychobiol 2018, 60, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulent Oguz GENC; İbrahim KILINÇ; Asli Akyol GURSES Relationship between Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy and Melatonin. Selçuk Tıp Dergisi 2023, 39, 35–40.

- Esposito, S.; Laino, D.; D’Alonzo, R.; Mencarelli, A.; Di Genova, L.; Fattorusso, A.; Argentiero, A.; Mencaroni, E. Pediatric Sleep Disturbances and Treatment with Melatonin. Journal of Translational Medicine 2019, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).