Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

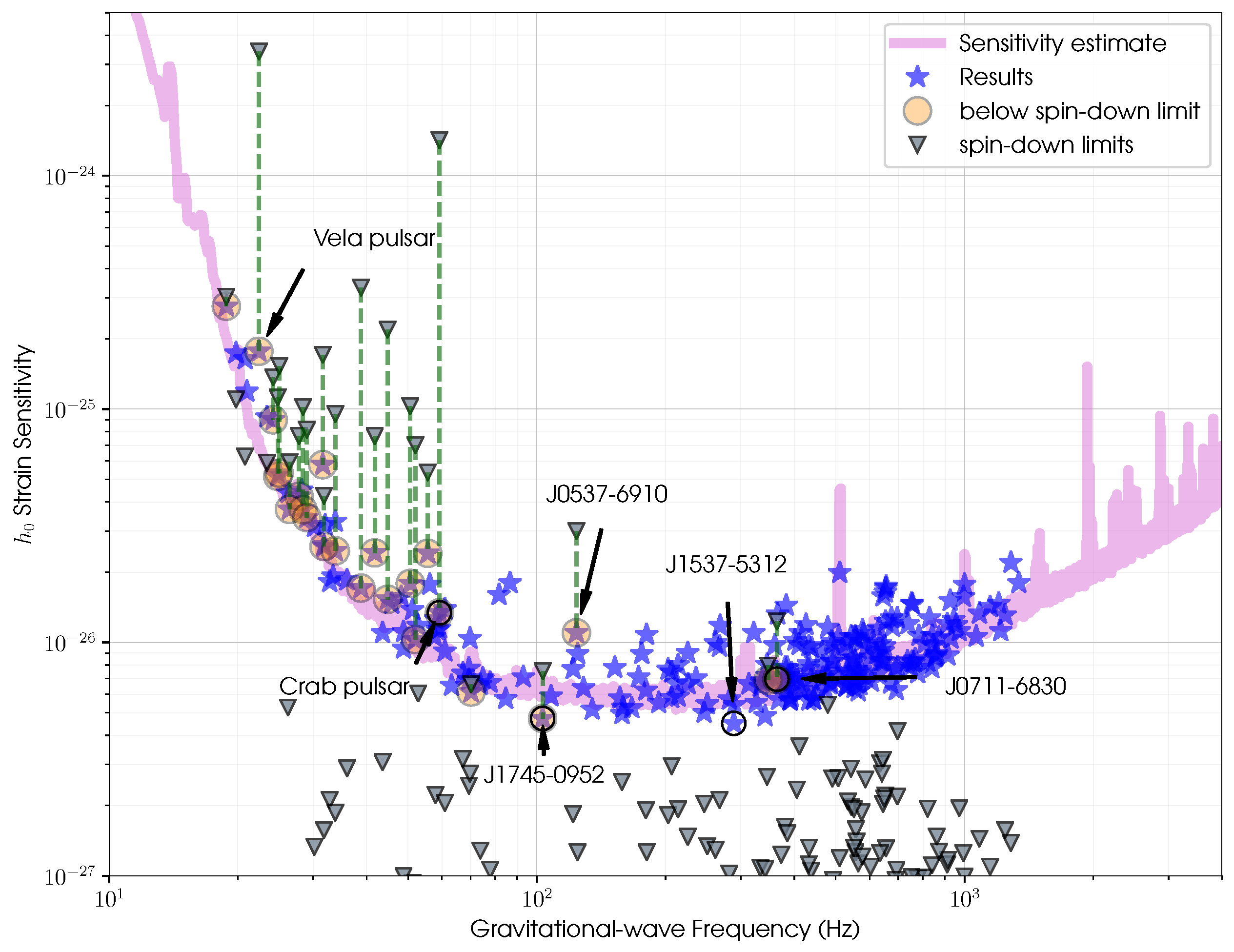

2. Dataset

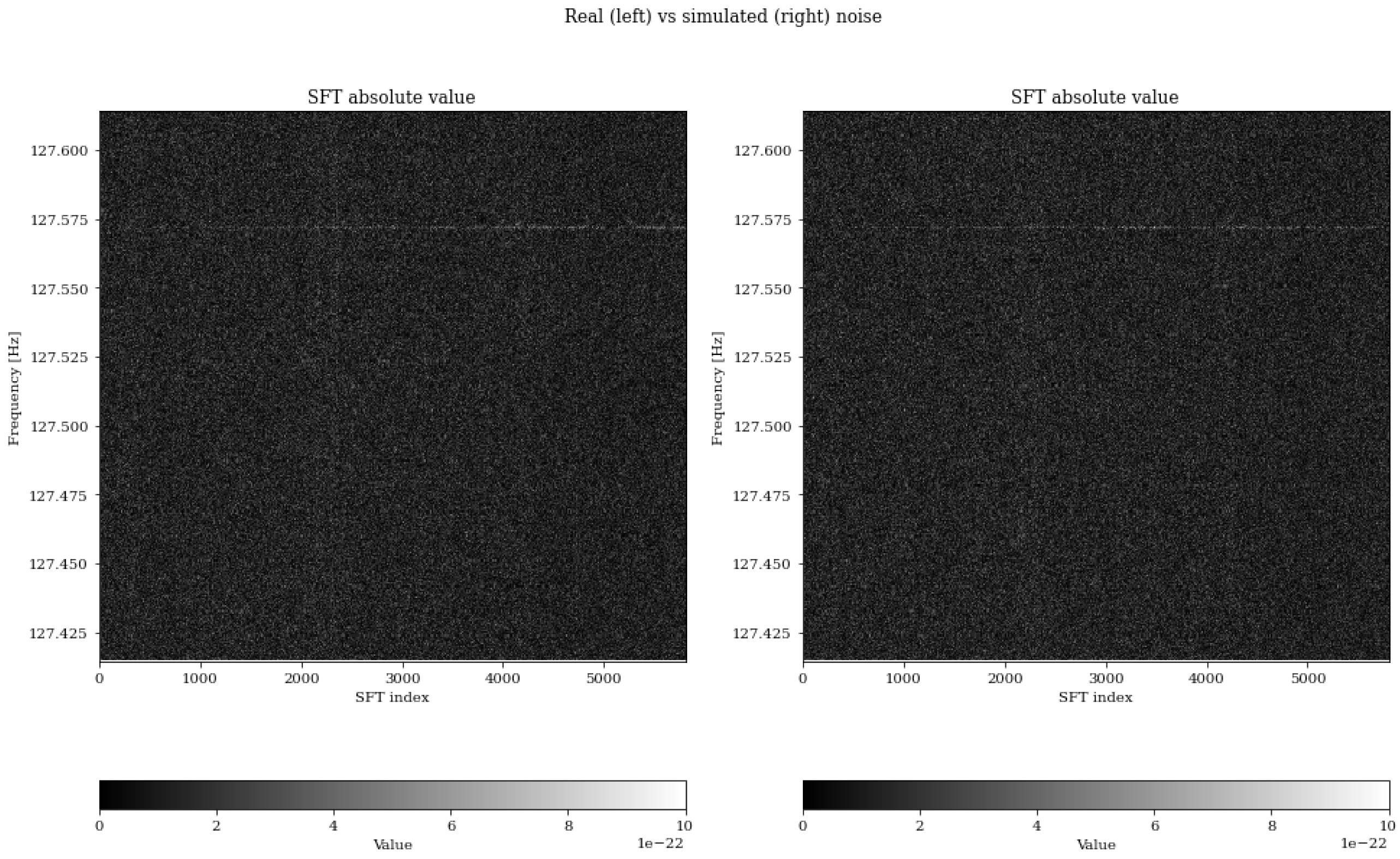

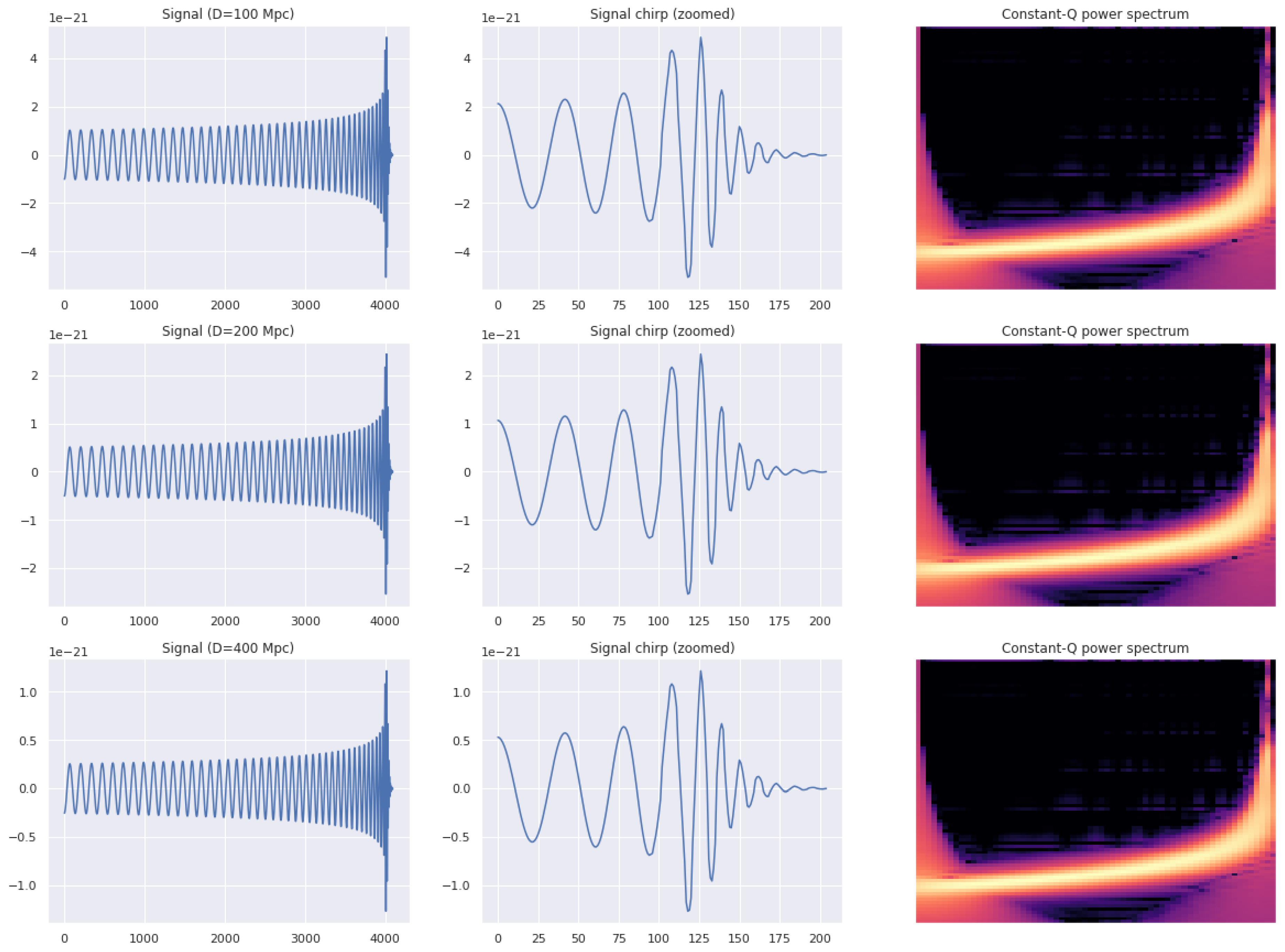

2.1. Generation of Data

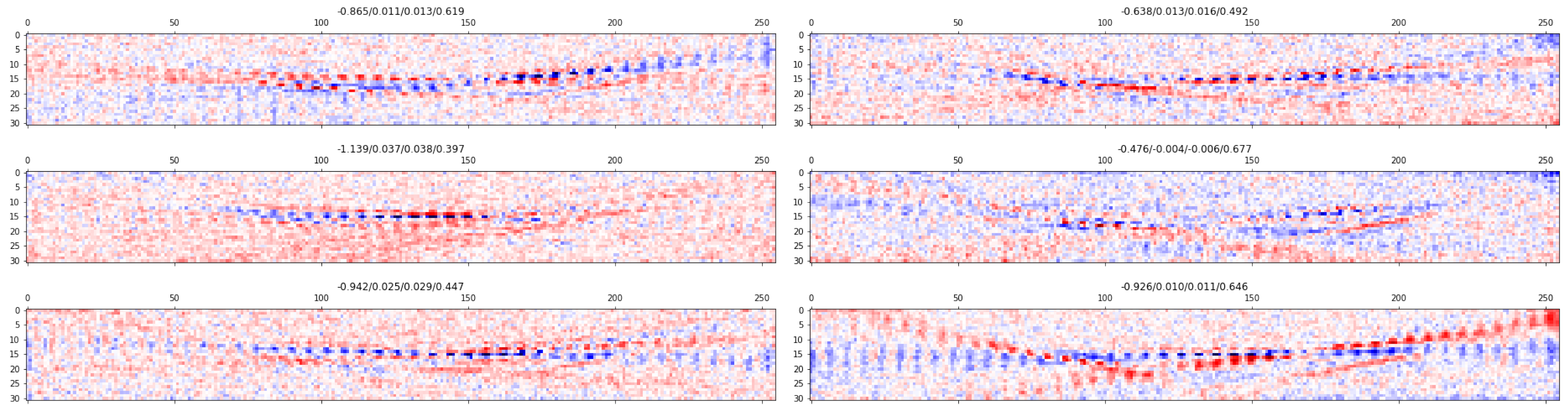

2.2. Data Processing

3. Comparison Test Benchmark

3.1. The Benchmark Definition

3.2. Weave Matched-Filtering Sensitivity

4. Deep Learning for Detecting CWs

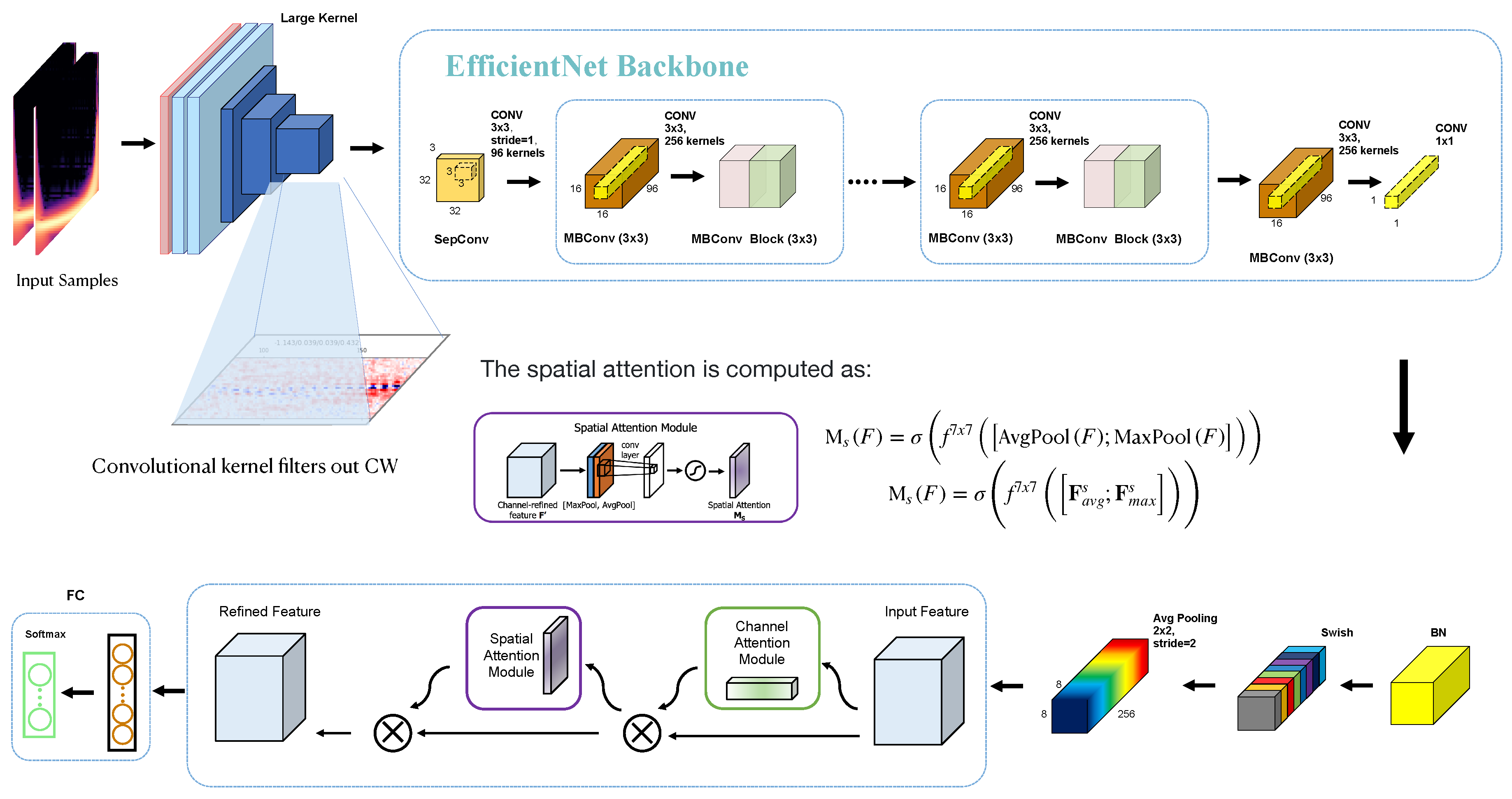

4.1. The Large Kernel Layer

4.2. Model architecture

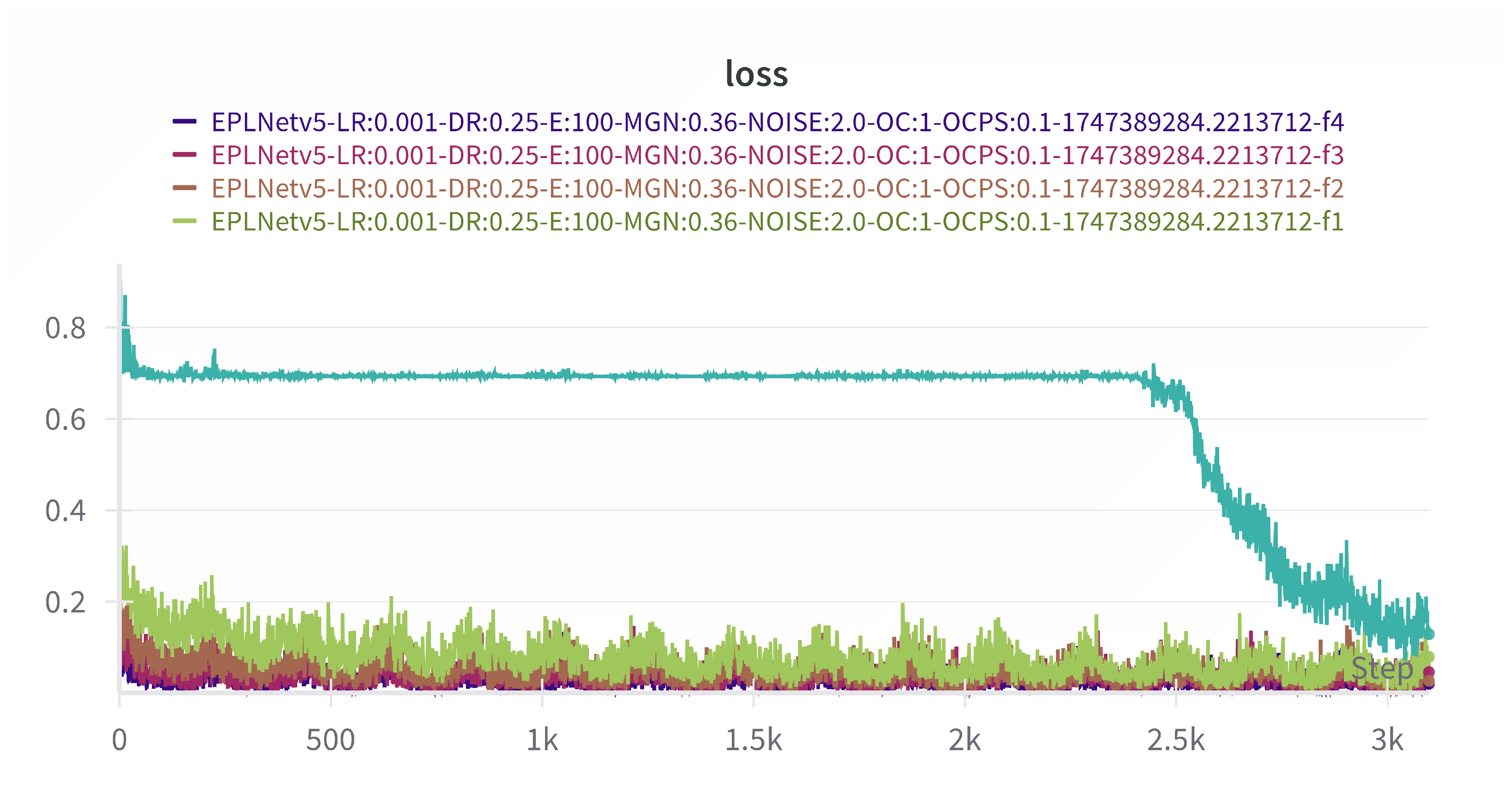

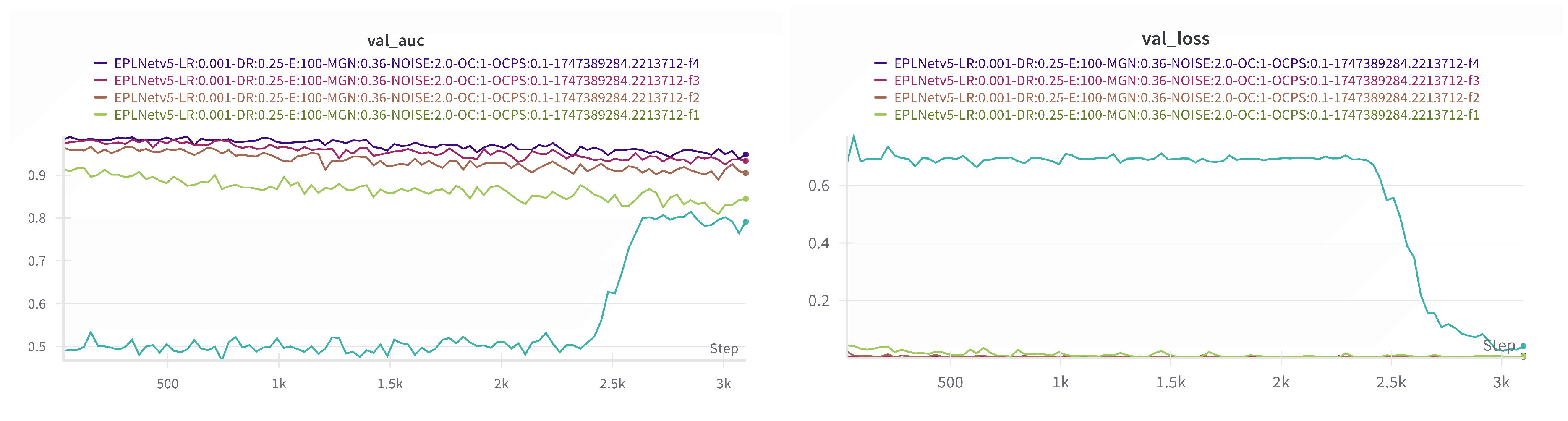

4.3. Training and Validation

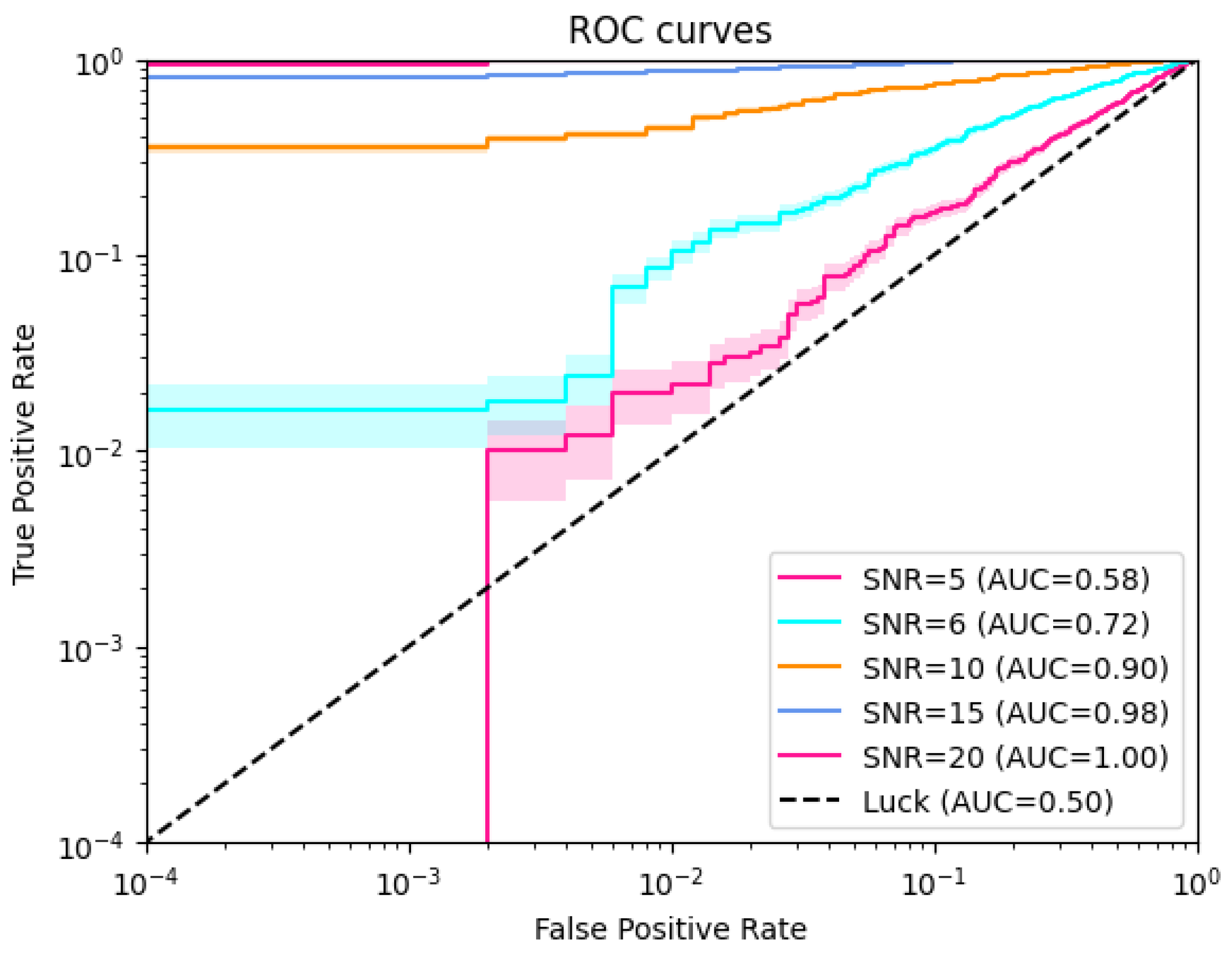

5. Result

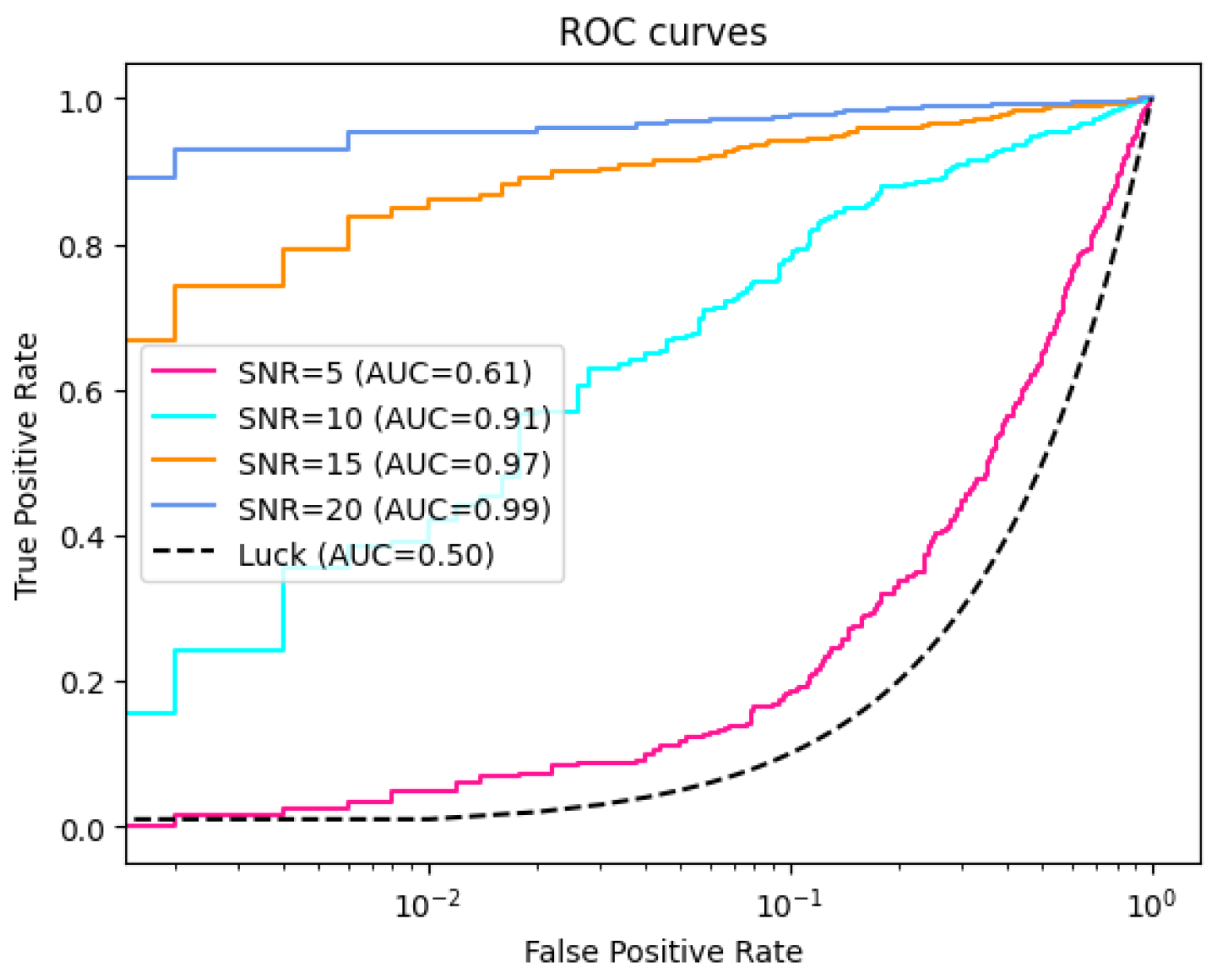

5.1. Test on Generated Data

5.2. Test on Injected Dataset

6. Discussion

References

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dreissigacker, C.; Sharma, R.; Messenger, C.; Zhao, R.; Prix, R. Deep-learning continuous gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 044009. [Google Scholar]

- Dreissigacker, C.; Prix, R.; Wette, K. Fast and accurate sensitivity estimation for continuous-gravitational-wave searches. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 084058. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Huerta, E.A. Deep learning for real-time gravitational wave detection and parameter estimation: Results with advanced ligo data. Physics Letters B 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Han, J.; Ding, G.; Sun, J. Scaling up your kernels to 31x31: Revisiting large kernel design in cnns. CVPR 2022 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dreissigacker, C.; Prix, R. Deep-learning continuous gravitational waves: Multiple detectors and realistic noise. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 102, 022005. [Google Scholar]

- Dreißigacker, C.; Prix, R.; Wette, K. Fast and accurate sensitivity estimation for continuous-gravitational-wave searches. Physical Review D 2018, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Dreißigacker, C.; Sharma, R.; Messenger, C.; Prix, R. Deep-learning continuous gravitational waves. Physical Review D 2019, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Cuoco, E.; Powell, J.; Cavaglià, M.; Ackley, K.; Bejger, M.; Chatterjee, C.; Coughlin, M.; Coughlin, S.; Easter, P.; Essick, R. Enhancing gravitational-wave science with machine learning. Mach. Learn 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, S.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. CoRR 2015, abs/1512.03385. [Google Scholar]

- Huan, S. Fast fourier transform and 2d convolutions. tjhsst 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P.M.; Prix, R. Novel neural-network architecture for continuous gravitational waves. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 108, 063021. [Google Scholar]

- Keitel, D.; Tenorio, R.; Ashton, G.; Prix, R. Pyfstat: a python package for continuous gravitational-wave data analysis. Journal of Open Source Software 2021, 6, 3000. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Kimura, Y.; Kudo, K. A column-wise update algorithm for nonnegative matrix factorization in bregman divergence with an orthogonal constraint. Mach. Learn 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, H.; Le, T.; Phung, T.; Bui, T.A.; Ho, N.; Phung, D. Global-local regularization via distributional robustness. cs.LG 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schrkhuber, C; Klapuri, A. Constant-q transform toolbox for music processing. Bibtex Nuhag 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. CoRR 2019, abs/1905.11946. [Google Scholar]

- the KAGRA Collaboration The LIGO Scientific Collaboration; the Virgo Collaboration. Searches for gravitational waves from known pulsars at two harmonics in the second and third ligo-virgo observing runs. LIGO-P2100049 2022. [Google Scholar]

- the KAGRA Collaboration The LIGO Scientific Collaboration; the Virgo Collaboration. Open data from the third observing run of ligo, virgo, kagra, and geo. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2023, 267, 29. [Google Scholar]

- the Virgo Collaboration The LIGO Scientific Collaboration. Gwtc-1: a gravitational-wave transient catalog of compact binary mergers observed by ligo and virgo during the first and second observing runs. Physical Review X 2019, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Wette, K.; Walsh, S.; Prix, R.; Papa, M.A. Implementing a semicoherent search for continuous gravitational waves using optimally constructed template banks. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 97, 123016. [Google Scholar]

- Zdeborová, L. Understanding deep learning is also a job for physicists. Nat. Phy. 2020, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Detecting gravitational waves using constant-q transform and convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Intelligent Systems, CIIS ’21, New York, NY, USA, 2022; Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. CoRR, 2019; abs/1911.02685. [Google Scholar]

| Data span | s |

|---|---|

| Noise | Stationary, white, Gaussian |

| Sky-region | All-sky |

| Signal depth | |

| Frequency band | Hz |

| Spin-down | Hz/s, |

| 50Hz | 200Hz | 300Hz | 400Hz | 500Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 | |||||

| 27.4 | 31.1 | 32.5 | 34.2 | 36.2 |

| Architecture | AUC Score | Backbone | Attention | Pooling Layer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPLNet | 0.9836 | tf-EfficientNet-b5-ns | Spatial + Channel Attention | AvgPooling2D |

| EPLNet | 0.8847 | tf-EfficientNet-b5-ns | Spatial + Channel Attention | GeMPooling |

| EPLNet | 0.9043 | EfficientNet-b7 | Spatial + Channel Attention | AvgPooling2D |

| EPLNet | 0.8144 | EfficientNet-v2-b0 | Spatial + Channel Attention | GeMPooling |

| EfficientNet CWT | 0.8779 | EfficientNet-b2 | Triplet Attention | AvgPooling2D |

| EfficientNet CWT | 0.87957 | Efficientnet-b7 | Triplet Attention | AvgPooling2D |

| EfficientNet WaveNet | 0.87948 | Efficientnet-b3 | Triplet Attention | AvgPooling2D |

| Densenet WaveNet | 0.8783 | Densenet201 | Triplet Attention | AvgPooling2D |

| VIT FERQ | 0.7790 | ViT-large-patch16-224-n21k | - | - |

| tf-EfficientNet-b5-ns | 0.7846 | - | - | - |

| ResNet1d-18 | 0.7631 | - | - | - |

| Unet | 0.7898 | - | - | - |

| Xception65 | 0.7753 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).