Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

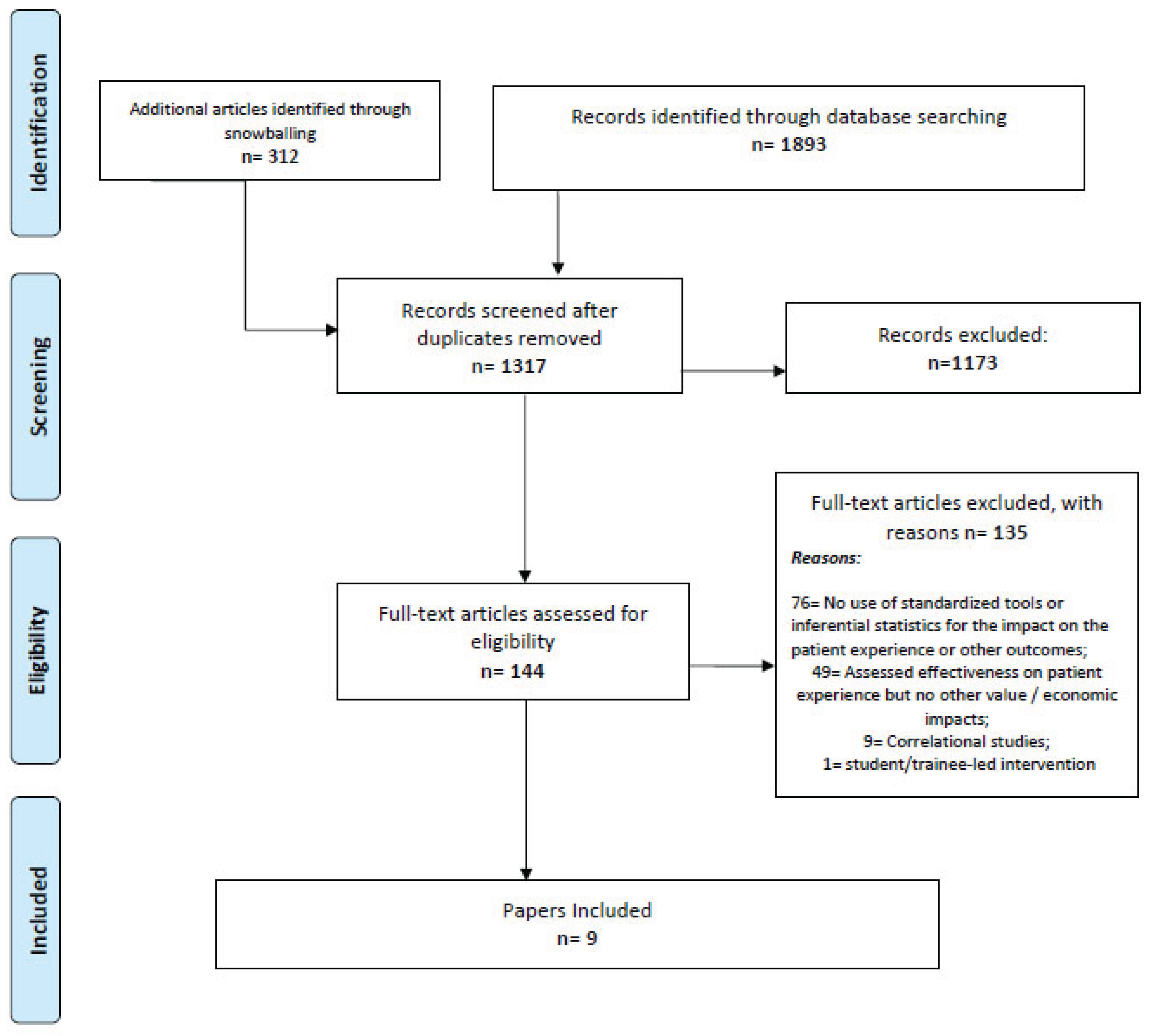

Materials and Methods

Results

Economic Impact of the Patient-Experience Improvement Interventions

Discharge Support

Patient Experience Office

Other Value-Based Impacts of Patient-Experience Improvement Interventions

Healthcare Utilization (e.g., Readmission Rates, Emergency Room Visits)

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. What Is Patient Experience? Rockville, MD [December 2022]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/patient-experience/index.html.

- Navarro S, Ochoa CY, Chan E, Du S, Farias AJ. Will Improvements in Patient Experience With Care Impact Clinical and Quality of Care Outcomes?: A Systematic Review. Medical care. 2021;59(9):843-56. Epub 2021/06/25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The CAHPS Program Rockville, MD [December 22]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/cahps-program/index.html.

- Medicare.gov. Find & compare providers near you 2022 [cited 2022 December 21].

- Elliott MN, Beckett MK, Lehrman WG, Cleary P, Cohea CW, Giordano LA, et al. Understanding The Role Played By Medicare’s Patient Experience Points System In Hospital Reimbursement. Health Affairs. 2016;35(9):1673-80. [CrossRef]

- Adams C, Walpola R, Schembri AM, Harrison R. The ultimate question? Evaluating the use of Net Promoter Score in healthcare: A systematic review. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. 2022. Epub 2022/08/20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Ghname A, Davis MJ, Shook JE, Reece EM, Hollier LH, Jr. Press Ganey: Patient-Centered Communication Drives Provider and Hospital Revenue. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2021;147(2):526-35. Epub 2021/02/11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma L, Chandrasekaran A, Bendoly E. Does the Office of Patient Experience Matter in Improving Delivery of Care? Production and Operations Management. 2020;29(4):833-55. [PubMed]

- Boissy A. Getting to Patient-Centered Care in a Post–Covid-19 Digital World: A Proposal for Novel Surveys, Methodology, and Patient Experience Maturity Assessment. NEJM Catalyst. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Congiusta S, Ascher EM, Ahn S, Nash IS. The Use of Online Physician Training Can Improve Patient Experience and Physician Burnout. Am J Med Qual. 2020;35(3):258-64. [CrossRef]

- Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, Karafa M, Neuendorf K, Frankel RM, et al. Communication Skills Training for Physicians Improves Patient Satisfaction. Journal of general internal medicine. 2016;31(7):755-61. Epub 2016/02/28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beach MC, Inui T. Relationship-centered care. A constructive reframing. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S3-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-6. Epub 2014/11/12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fitzpatrick B, Bloore K, Blake N. Joy in Work and Reducing Nurse Burnout: From Triple Aim to Quadruple Aim. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2019;30(2):185-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell TG, Mylod DE, Lee TH, Shanafelt T, Prissel P. Physician Burnout, Resilience, and Patient Experience in a Community Practice: Correlations and the Central Role of Activation. Journal of Patient Experience. 2019;7(6):1491-500. [CrossRef]

- Porter TH, Rathert C, Ishqaidef G, Simmons DR. System justification theory as a foundation for understanding relations among toxic health care workplaces, bullying, and psychological safety. Health Care Manage Rev. 2024;49(1):59-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathert C, Vogus T, Hearld LR. Psychological work climates and health care worker well-being. Health Care Manage Rev. 2024;49(2):85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71. Epub 20210329. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schreiter NA, Fisher A, Barrett JR, Acher A, Sell L, Edwards D, et al. A telephone-based surgical transitional care program with improved patient satisfaction scores and fiscal neutrality. Surgery. 2021;169(2):347-55. Epub 2020/10/24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thum A, Ackermann L, Edger MB, Riggio J. Improving the Discharge Experience of Hospital Patients Through Standard Tools and Methods of Education. Journal for Healthcare Quality: Promoting Excellence in Healthcare. 2022;44(2):113-21. Language: English. Entry Date: 20220419. Revision Date: 20220419. Publication Type: Article. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamirano J, Kline M, Schwartz R, Fassiotto M, Maldonado Y, Weimer-Elder B. The effect of a relationship-centered communication program on patient experience and provider wellness. Patient education and counseling. 2022;105(7):1988-95. Epub 2021/11/14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBedz SL, Prieto-Centurion V, Mutso A, Basu S, Bracken NE, Calhoun EA, et al. Pragmatic Clinical Trial to Improve Patient Experience Among Adults During Transitions from Hospital to Home: the PArTNER study. Journal of general internal medicine. 2022;37(16):4103-11. Epub 20220308. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- March KL, Peters MJ, Finch CK, Roberts LA, McLean KM, Covert AM, et al. Pharmacist Transition-of-Care Services Improve Patient Satisfaction and Decrease Hospital Readmissions. Journal of pharmacy practice. 2022;35(1):86-93. Epub 2020/09/19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinleye DD, McNutt LA, Lazariu V, McLaughlin CC. Correlation between hospital finances and quality and safety of patient care. PloS one. 2019;14(8):e0219124. Epub 2019/08/17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richter JP, Muhlestein DB. Patient experience and hospital profitability: Is there a link? Health care management review. 2017;42(3):247-57. Epub 2016/04/07. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus TS, Stern BZ, Struhar J, Deutsch A, Heinemann AW. The use of patient experience feedback in rehabilitation quality improvement and codesign activities: Scoping review of the literature. Clin Rehabil. 2023;37(2):261-76. Epub 20220916. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwyn G, Frosch DL, Kobrin S. Implementing shared decision-making: consider all the consequences. Implementation science : IS. 2016;11:114. Epub 2016/08/10. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coulmont M, Roy C, Dumas L. Does the Planetree patient-centered approach to care pay off?: a cost-benefit analysis. The health care manager. 2013;32(1):87-95. Epub 2013/02/01. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee VS, Miller T, Daniels C, Paine M, Gresh B, Betz AL. Creating the Exceptional Patient Experience in One Academic Health System. Acad Med. 2016;91(3):338-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jesus TS, Struhar J, Zhang M, Lee D, Stern BZ, Heinemann AW, et al. Near real-time patient experience feedback with data relay to providers: a systematic review of its effectiveness. Int J Qual Health Care. 2024;36(2). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanbhai M, Flott K, Darzi A, Mayer E. Evaluating Digital Maturity and Patient Acceptability of Real-Time Patient Experience Feedback Systems: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1):e9076. Epub 20190114. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Patient Experience Component | Economic Component | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design & Context | Intervention (synthesis) | Patient Experience Outcomes (synthesis) | Economic Indicator(s) & Data | Economic Analysis & Methods | Economic outcomes | |

| (Thum, Ackermann et al. 2022) | Pre-post test, 12 months each. Academic hospital and its community hospital affiliate. | Discharge support: Nurses were trained in teach back; workflow was redesigned. A new discharge summary was created, linked to a hard stop in the electronic health record. | Improved top box %s: Care Transitions, 52.4–54.5% (p< .001); Discharge Information, 87.4–90.1% (p< .001). Improved percentile rank: 45.2–74.3 (p= .020) for Discharge Information. | Revenue; Unspecified internal organizational data | Hospital Revenue impact analysis, pre- and post-intervention Unspecified methods. | The intervention had a positive impact on the value-based purchasing program, with an estimated savings of $75,000 compared to the pre-intervention expectations due to better patient experience scores: Care Transitions and Discharge Information domains. |

| (Schreiter, Fisher et al. 2021) | Controlled before-and-after, historical cohort of controls. Academic hospital. | Post-discharge support: Telephone follow-up delivered by nurses after hospital discharge for patient education, medication reconciliation, or remediation care (e.g., same-day clinic appointment) if required. | Intervention got greater %s of top-box scores in 5 of 11 items: asking about having the needed help (100% vs. 93%, p<.01), educational materials (68% vs. 55% p< .01), understanding of responsibilities (69% vs. 59%, p= .02), instructions on whom to call with post discharge questions (76% vs. 69%; p= .04), and global experience (57% vs. 46%, p= .02). | Costs: Total hospital costs and transitional care expenses (new nurses’ salaries and fringe; infrastructure investments negligible). Margin: Estimated payer reimbursements subtracting the total hospital costs. | Hospital Costs & Margin Impact. Fiscal data converted to 2017 US dollars using Consumer Price Index. Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare groups’ fiscal data. Predictive multivariable models of cost and margin for index admission, 90-day readmission, and aggregate. Covariates were those with statistical and clinical relevance (e.g., age). | The intervention cost +$430 per patient; the rank-sum comparison for aggregate 90-day admissions showed between-group differences for the hospital cost ($25,827 vs $22,814, p<.01) but not the margin: $4.698 (95% CI: -2.85–21,100) vs $7.027 (-1.36–20,734), p=.25. The multivariable model showed similarly significant results (cost differences: p=.03; margin differences; p=.23). |

| (Abu-Ghname, Davis et al. 2021) | Pre-post test, retrospective, one site; controlled subgroup analysis for plastic surgeons. Children's hospital. | Communication training: 5.5h course led by two volunteer practicing clinicians trained in-house (in facilitation in a model of relationship-centered care). The course featured role-playing of the communication skills. | Improvements in the scope of provider recommendation (90.7-94.1; p<.001), language (90.9-94.0; p=.007), concern (91.4-94.1; p=.007), decision sharing (91.8-94.3; p=.001), and information (94.0-95.4; p=.031). | Revenue, in charges (the amount billed by the hospital) and in payments (the amount of reimbursements received). Internal organizational data adjusted for price increases. | Hospital Revenue, pre-post impact: total charges and overall payments (plus # of distinct patients and encounters). To control for price changes, revenue was compared after controlling for calendar year 2016 per-unit charges (Current Procedural Terminology). | Payments increased by 25%, and charges increased by 21% - clinical encounters increased by 26%, and the number of patients increased by 26%. Specifically for the subgroup of plastic surgeons, participants reported 113% increases in charges and 71% increases in payments, whereas controls had decreases of 10% in charges and 4% in payments. |

| (Sharma, Chandrasekaran et al. 2020) | Retrospective comparative study. National sample of hospitals. Key informant interviews (1 hospital). | Office of Patient Experience (OPX): Patient experience office as a new administrative structure with its own budget and staff and a head who is an executive board member (versus hospital without that structure). | A 1.95% increase was found in experiential quality per year of operation (p<.05), more so for hospitals with high vs low patient complexity (6.5% vs -0.3%, p< .05). | Operating Costs. Any expenses incurred in every aspect of a hospital’s operations, including salaries, supplies, and administrative expenses. CMS Cost Reports | Hospital Operating Costs impact: proxy for the cost of setting up & running an OPX. Once computed from the CMS Cost Reports, operating costs were divided by the # of beds to normalize it for size. A natural log of cost per bed was used to reduce the impact of outliers. Fixed effects instrumental variable regression with years of OPX operation as the predictor. | Years of operation were weakly associated with reduced operating costs (b= -0.18, p< 0.10). It translates into a 1.4% operating-costs reduction per added year of operation. Interviews suggest efficiencies in trainings, improved outcomes due to better provider communication, greater patient volumes due to satisfaction and word of mouth, and better value-based reimbursement. |

| Patient Experience Component | Wellness outcomes | ||||

| Study Design & Context | Intervention (synthesis) | Patient Experience Outcomes (synthesis) |

Outcome(s) type and Measure | Outcomes | |

| (Altamirano, Kline et al. 2022) | Pre-post test, 3 months post intervention, four sites. Academic hospital - four sites, multi- department. | Communication training: training (8h) in workshops (n= 48; 14 seats each), led by trained peer physicians. After nomination by department chairs, a board selected instructors on 6 criteria: e.g., patient experience scores, thought leader for communication. Instructors had training toward certification. Trainees applied the skills to cases elicited during the workshop followed by small group feedback. Continuing education credits were provided. | Top-box scores increased from 82.8% to 84.5% (p<.0001). The odds of receiving a top-box score 6 months after the program vs prior (1.11, p= .01) and >6 months (1.15, p< .0001) also increased. Gains persisted in a propensity score weighted analysis (1.09, p= .04; 1.14, p< .0001). When stratified by site, two of four had significant improvements. | Burnout/Wellness, Professional Fulfillment Index subscales: burnout, compassionate self-improvement, professional fulfillment, emotional exhaustion, and interpersonal disengagement. | Burnout decreased significantly from 35% to 26% (p< .039). In addition, compassionate self-improvement and professional fulfillment increased from 37% to 50% (p< .020) and from 41% to 51% (p< .034). Scores for emotional exhaustion and interpersonal disengagement decreased, but the changes were not statistically significant. |

| (Congiusta, Ascher et al. 2020) | Pre-post test (burnout outcomes) within a RCT (patient experience outcomes), Medical practices. | Communication training: Online provider training weekly for 24 weeks and biweekly conference calls led by top-performing physicians trained in the model and facilitation. Trainees needed to "learn", "do", and "share" the successes in conference calls or a web tool. Team-based breakfast for the best-performers and graduation celebration. | The intervention group had a greater improvement in scores compared to controls (median [Q1, Q3]= 1.6 [0.4, 2.4] vs 0.6 [−1.3, 1.9], p< .039), but no significant difference in the percentile ranks (median [Q1, Q3]= 4.0 [-27.0, 13.0] vs -13.0 [-36.0, 12.0], p < .346). | Burnout: Maslach Burnout Inventory and its three subscales: emotional exhaustion, burnout, depersonalization, and personal achievement | Two of the subscales had significant changes. The depersonalization score was significantly lower than baseline – mean difference (SD) -2.43 (5.30), p< .023), and the personal achievement score increased (mean difference 3.10 (3.62); p = .0007). The decrease in the burnout, total score, nearly reached statistical significance (p= .0504). |

| (Boissy, Windover et al. 2016) | Pre-, post-, and 3-months post study within a controlled, before- and-after study; hospital & clinician group. | Communication training: 8h provider training. Each course (<12 physicians each) was facilitated by two clinicians trained in the communication model, adult learning, performance assessment, and group facilitation. Didactic presentations, live or video-based skill demonstrations, and small-group skills practice sessions were followed by skills practice on communication challenge from trainees’ practices. | Clinicians Group: Adjusted communication scores were greater for the intervention group vs controls (92.09 vs 91.09, p< .03). Hospital: Adjusted respect scores were greater in the intervention vs controls (91.08 vs 88.79, p=.02), but differences were non-significant for the adjusted communication scores (83.95 vs 82.73, p=0.2). | Burnout: Maslach Burnout Inventory and its three subscales: emotional exhaustion, burnout, depersonalization, and personal achievement | Following the course, lower burnout was significantly found on all three subscales (emotional exhaustion: p< .001; depersonalization: p= .003, and personal achievement: p= .04). Improvements in all measures except emotional exhaustion were sustained at 3 months. |

| Patient Experience Component | Healthcare utilization outcomes | ||||

| Study Design & Context | Intervention (synthesis) | Patient Experience Outcomes (synthesis) |

Outcome(s) type and Measure | Outcomes | |

| (LaBedz, Prieto-Centurion et al. 2022) | Pragmatic RCT, patient-level randomization. Multivariable linear regression models, with a Bonferroni correction for the co-primary outcomes | Transitional care: The intervention group received an intervention during the index hospitalization and for 60 days post-discharge, which included 1) in-hospital visits by a community health worker to assess barriers to health/healthcare and to develop a personalized Discharge Patient Education Tool (DPET); 2) a post-discharge home visit by a community health worker to review the DPET; and 3) telephone-based peer coaching. | No significant between-group differences in the 30-day change in informational support (adjusted difference: −0.01, 97.5% CI −2.0 to 1.9, p=0.99), or any secondary outcomes such as emotional support [−0.12, 95% CI −1.5, 1.2, p=0.86] or instrumental support [−0.43, 95% CI −1.7, 0.93, p=0.53]. An exploratory subgroup analysis showed greater improvements in 30-day informational support for navigator group participants without health insurance (+11.9, 95% CI 2.3 to 21.4). | Utilization: 14-day outpatient visit, 30-day and 60-day hospitalization or emergency room visits | No significant between-group differences in healthcare utilization (outpatient visit, hospitalization, emergency room visits). |

| (March, Peters et al. 2022) | Observational, case control comparison with retrospective review, single-center, pilot program, hospital-based pharmacy | Patient education and discharge support: Pharmacist-led medication reconciliation and education, sensitive to health literacy levels, prior and post discharge following alerts from the electronic medical record system. | Significant improvement in the top-box scores (52.6% vs. 67.3%; p= <.001) in the composite of medication-related HCAHPS results and its specific items: “tell you what the medicine was for” (67.7% vs. 81.9%; p= .018), “describe possible medicine side effects” (37.7% vs. 58.9%; p= 0.004), and "understood the purpose of taking medications" (52.3% vs. 63.7%; p= .035). | Readmissions: 30-day readmissions. | Non-significant difference in 30-day readmissions for the complete intervention vs non-intervention (16.4% vs 13.3%; p= .133); an unplanned subgroup analysis for the discharge phone calls (with or without discharge education) showed a significant reduction in 30-day readmission rates: 17.3% vs 12.4% (p= .007). |

| (Thum, Ackermann et al. 2022), described in Table 1 | Readmissions: 30-day readmissions | No significant difference pre- to post-intervention (p=.69). | |||

| (Schreiter, Fisher et al. 2021), described in Table 1 | Readmissions: 90-days readmissions | No significant difference between groups (p= .21) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).