1. Introduction

Studies show that the diagnosis of infectious diseases based on the detection of antibodies in urine is a viable, safe, convenient, and non-invasive technique. This diagnostic methodology has been studied for filariasis (1) , hepatitis A and C (2), schistosomiasis (3), dengue (4), strongyloidiasis (5), Helicobacter pylori infection (6), leishmaniasis (7,8), among other diseases (9). Although the concentration of antibodies in urine is about 4,000 to 10,000 times lower when compared to serum(10,11), it is possible to detect antibodies in urine using the ELISA method (1), which can have several applications, such as its use for epidemiological prevalence studies (9).

Given the advantages of urine as a serologic specimen, a study conducted during the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic employed an in-house urine-based ELISA using recombinant severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) nucleocapsid (N) protein to detect anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG in the urine of unvaccinated hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, previously confirmed by qRT-PCR (12). In addition, a validation study of an in-house ELISA using urine samples successfully detected IgG against partial chimeric SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) and N proteins expressed in a prokaryotic system, highlighting it as a convenient and cost-effective alternative to serum-based methods, particularly in settings where sample collection poses challenges (12-14).

With the advent of vaccines against COVID-19, it was hypothesized that tests that detect antibodies against the N protein in urine could differentiate between the humoral response caused by previous infection versus that caused by vaccination (15). This would only be applicable in the cases of vaccines that used only the S protein as an antigen. In order to advance knowledge in ELISA diagnostic testing in urine, the present study was carried out. We tested both the S protein and the N protein in the urine of adults vaccinated with AD26.COV2.S (COVID-19 vaccine Janssen), whose antigen is the S protein. For the analyses, these individuals were divided into two groups, one with and one without a previous history of COVID-19 confirmed by RT-PCR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a comparative cross-sectional observational study that analyzed anti-S and anti-N antibodies in urine and serum samples from individuals vaccinated against COVID-19 with the AD26.COV2 vaccine Janssen.

2.2. Study population

The included participants were adults 18 years of age or older and in good health, residing in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, who had received the AD26.COV2.S (COVID-19 vaccine Janssen) between November 2020 and December 2021. Individuals who had received other vaccines against COVID-19 were excluded from this study. Serum and urine samples from these individuals were collected between May 2022 and July 2022.

Between November 2020 and July 2022, all study participants who presented symptoms with suspected COVID-19 were subjected to nasopharyngeal swab collection for SARS-COV-2 testing with RT-PCR. Diagnoses of COVID-19 prior to study entry were considered if confirmed by a positive RT-PCR test.

Unpaired urine and serum samples, collected in the pre-pandemic period or from unvaccinated individuals who, during the pandemic, maintained strict quarantine and did not have any symptoms, were used as negative controls and were considered never to have been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

2.3. Sample collection

Blood (20mL) and urine (80mL) paired samples were collected simultaneously from each participant. Urine samples were collected at any time of day and without a fixed urine retention time, but the collection of morning urine or after an average retention period of 4 hours was recommended, whenever possible. Urine samples were collected in sterile 80 mL bottles and subsequently transferred to 15 mL tubes containing sodium azide (71289, Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, USA) at a final concentration of 0.1% (v/v). The tubes were transported at room temperature and stored at 2 to 8 °C until use. Pre-pandemic urine samples had been collected before 2019 and kept refrigerated (2 to 8 °C) until use.

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture using a sterile 20 mL collection tube without anticoagulant and containing a serum separator gel. The tubes were centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, with the serum collected and stored in conical eppendorf-type tubes at -20 °C until use.

2.4 ELISA

The ELISA methodology was performed according to previous studies (12), following the ideal experimental conditions for each type of recombinant protein used, rSARS-CoV-2 N prokaryotic (FAPON, China, catalog number 516) (12), rSARS-CoV-2 S eukaryotic (FAPON, China, catalog number 537) and rSARS-CoV-2 S prokaryotic in-house (16), and for each sample, urine or serum.

First, a titration curve was performed to determine the concentration of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 N and S proteins (50 to 1000 ng), urine dilution (1:1 and undiluted), and the most appropriate human anti-IgG conjugate (1:80,000 to 1:2,500) at different incubation times (30 to 60 min). After titration, the best parameters for the recombinant proteins and each sample type were applied in the ELISA, using a larger number of samples. Polystyrene plates (High binding 96-well polystyrene microplate - Corning, Merck, Germany, catalog number: CLS2592) were coated with the recombinant proteins diluted in carbonate buffer for 16 h at 4°C: 400 ng of antigen/well of each recombinant N and S protein (prokaryotic and eukaryotic). After sensitization, blocking was performed using 200 µL of a solution containing 1x PBS, 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and 1% BSA for 2 h at 37 °C. The plates were then washed 5 times using PBS-T and incubated with 100 µL of undiluted urine for 1 hour at 37 °C. The plates were washed 5 times using PBS-T and then incubated with 100 µL of peroxidase-conjugated human anti-IgG antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution for N commercial, S commercial, and S in-house proteins in PBS-T for 1 h at 37 °C. Again, the plates were washed 5 times with PBS-T and the reactions were developed using TMB chromogenic solution (3,3',5,5; tetramethylbenzidine, Moss, USA) for 30 min in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding H2SO4 (0.5 M) and the optical density (OD) was read in a spectrophotometer for ELISA microplates (Multiskan Go) at λ450 nm.

The assays using serum samples were performed with a previously optimized protocol (12,17). The sensitization of the plates was performed using 400 ng of each of the recombinant commercial proteins N and S, and S (in-house) with serum dilution (1:100) and anti-IgG antibody (FAPON, China) 1:40,000 for N and 1:10,000 for S, with incubation times of 30 min each.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

The sample size was one of convenience, and analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0 for Windows) and SPSS (version 15.0 for Windows). The distributions of continuous variables were obtained as mean ± standard deviation, as indicated, while categorical variables were assessed as proportions. The Student's t-test was used to compare continuous variables between distinct groups, and the chi-square test was used to compare proportions. Pearson's test was used to evaluate the correlation between continuous variables. To assess sensitivity and specificity, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated. A p-value of <0.05 was used to establish statistical significance.

3. Results

The study included 149 individuals vaccinated with AD26.COV2.S, of whom 71 (48%) had a history of COVID-19 confirmed by RT-qPCR, none of them had been hospitalized due to the infection.

The average age of the study participants was 55 years (±13), and 52% were assigned male at birth. Of the participants, 145 had received two doses of the AD26.COV2.S vaccine, while four had received three doses. The time from the last dose to sample collection was less than six months in 20 participants (13%) and greater than or equal to six months in 129 participants (87%).

Among the vaccinated participants without a history of COVID-19 (Group 1), 51% were male, versus 52% in the group of vaccinated individuals with a history of infection (Group 2) (p=0.919). A significant difference for age was observed, with the mean being 58 years (±12) in Group 1 and 51 years (±13) in Group 2 (p=0.001). For the number of doses and time between the last dose and sample collection, no significant difference was observed between the groups, with the mean number of doses of 2.03 (±0,159) for Group 1 and 2.03 (±0,167) for Group 2 (p=0.925) and mean of months from the last dose being 5.77 (±0.81) for Group 1 and 5.87 (±0.41) for Group 2 (p=0.329).

The negative control samples (Group 0) used were 23 unpaired urines and 24 sera of unvaccinated individuals without prior infection. There is no information on the sex and age of these control individuals.

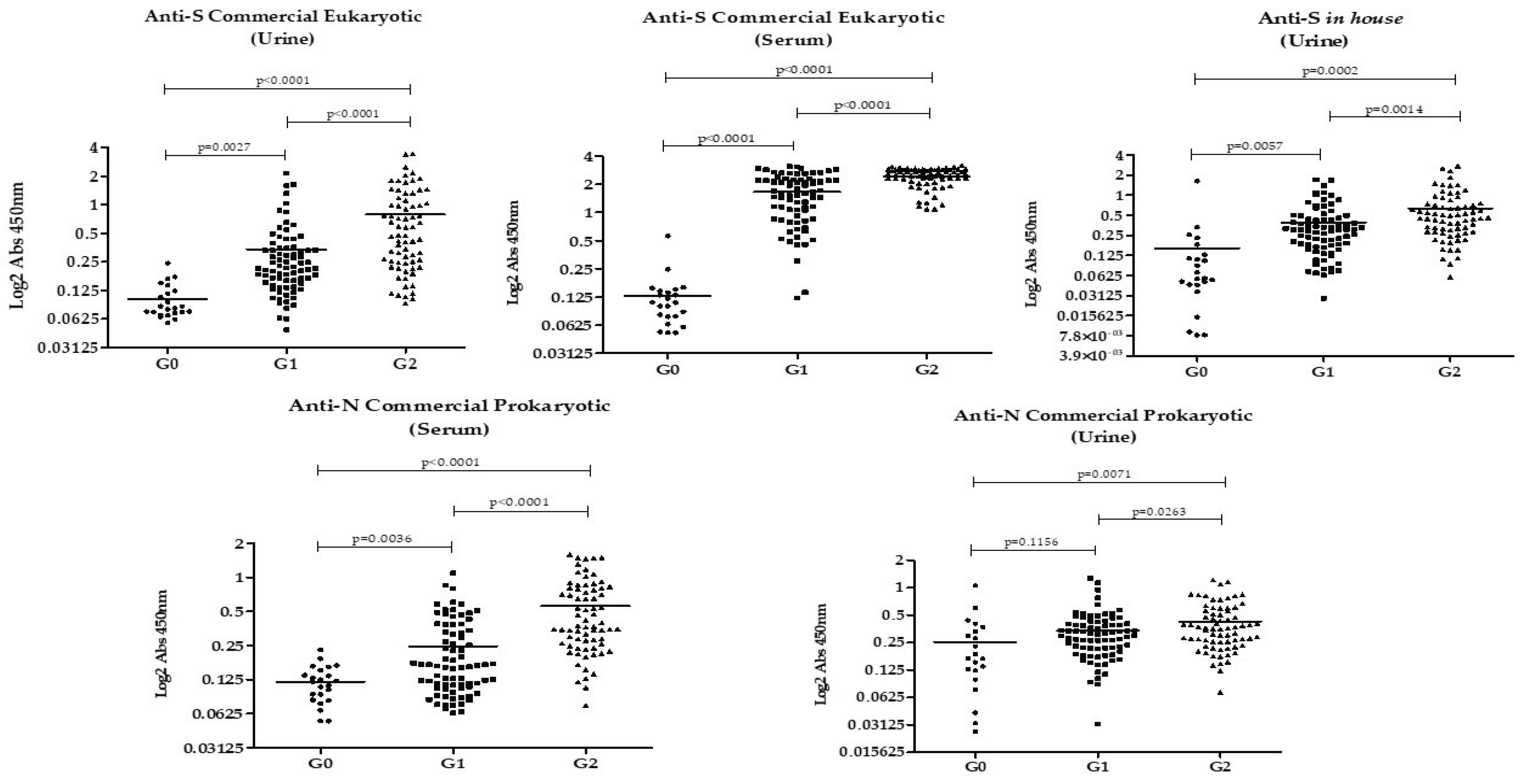

The results of IgG detection in urine and serum of each group of participants using the different rSARS-CoV-2 proteins are shown in

Figure 1. Overall, antibody levels against all studied proteins were highest in Group 2, followed by Group 1, with the lowest levels observed in Group 0. This pattern was evident in both urine and serum. The only groups that did not show a statistically significant difference in antibody levels were Group 0 and Group 1 when anti-N was analyzed in urine.

The Pearson correlation showed no association between age or number of doses and the absorbance values. A correlation was found between the values of anti-N and anti-S and between serum and urine according to Table 4 (p<0.001), except for anti-eukaryotic S in serum and anti-prokaryotic N in urine, which showed no correlation (p>0.05).

Table 1.

Correlation between anti-N and anti-S in serum and urine, age, and vaccine doses (Pearson's coefficient). Table cells in blue mean p<0.05. .

Table 1.

Correlation between anti-N and anti-S in serum and urine, age, and vaccine doses (Pearson's coefficient). Table cells in blue mean p<0.05. .

| |

Anti-N prokaryotic (serum) |

Anti-N prokaryotic (urine) |

Anti-S eukaryotic (serum) |

Anti-S eukaryotic (urine) |

Anti-S prokaryotic in-house (urine) |

Age |

Dose number |

| Anti-N prokaryotic (serum) |

NA |

0.302 |

0.491 |

0.344 |

0.269 |

0.044 |

0.074 |

| Anti-N prokaryotic (urine) |

0.302 |

NA |

0.0009 |

0.428 |

0.584 |

0.078 |

0.073 |

| Anti-S eukaryotic (serum) |

0.491 |

0.009 |

NA |

0.493 |

0.285 |

0.044 |

0.034 |

| Anti-S eukaryotic (urine) |

0.344 |

0.428 |

0.493 |

NA |

0.694 |

-0.084 |

0.067 |

| Anti-S prokaryotic in-house (urine) |

0.269 |

0.584 |

0.285 |

0.694 |

NA |

0.050 |

0.113 |

| Age |

0.019 |

0.078 |

0.044 |

-0.084 |

0.050 |

NA |

0.002 |

| Dose number |

0.074 |

0.073 |

0.034 |

0.067 |

0.113 |

0.002 |

NA |

The accuracy of each rSARS-CoV-2 protein was measured in urine and serum and AUC, sensibility and specificity are shown in

Table 2. ROC curves were constructed to distinguish negative controls (non-vaccinated non-previously infected individuals) from vaccinated previously infected individuals (G0 x G2); negative controls from vaccinated non-previously infected (G0 x G1) and vaccinated previously infected from vaccinated non-previously infected (G1 x G2). The results show better accuracy measurements when proteins were used to distinguish G0 from G2.

4. Discussion

Our findings showed that antibodies against the recombinant S and N proteins of SARS-CoV-2 are present in the urine of individuals vaccinated with AD26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine Janssen, and among them, in higher amounts in those who had a previous infection. It is noteworthy that among the patients with previous infection, none had been hospitalized and the mean number of months from the last dose was 5.77 (±0.81) for Group 1 and 5.87 (±0.41) for Group 2 (p=0.329). This means urinary anti-N and anti-S persist for months even after a mild to moderate infection.

In the comparison between unvaccinated individuals without prior infection (Group 0) and vaccinated previously infected individuals (Group 2), there was a significant difference in reactivity to all the analyzed proteins, in urine and serum samples. This finding is explained by the presence of high levels of anti-S as a response to both the vaccine and the infection. In contrast, the presence of antibodies against the N protein indicates humoral response to active or past infection, as the AD26.COV2.S vaccine does not contain the N protein in its formulation.

In the comparison between the groups without prior infection (vaccinated versus unvaccinated individuals), urinary and serum anti-S antibodies were higher among vaccinated individuals, showing the immune response to the AD26.COV2.S vaccine. This finding is in line with previous studies that demonstrated the efficacy of AD26.COV2.S against severe and critical COVID-19 (17–19) and its association with elevated neutralizing antibody levels (20).

When evaluating anti-N protein in urine, its levels were lower in individuals without prior confirmed infection, vaccinated or not. However, in serum, vaccinated individuals without previous COVID-19 had higher levels of anti-N compared to negative controls (unvaccinated without prior infection). This could be explained by cross-reactions with other coronaviruses (15) or prior undiagnosed asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Since this finding was not seen in urine samples, it is suggested that anti-N in serum may have greater sensitivity for detecting cross-reactions or prior asymptomatic infection.

A higher urinary anti-S reactivity was found among vaccinated previously infected individuals compared to vaccinated without prior infection: S eukaryotic G1 (0.3397 ± 0.04176) x G2 (0.7876 ± 0.08827), p< 0.0001; S in-house G1(0.3931 ± 0.03978) x G2 (0.6386 ± 0.06637) p< 0.0001. This difference is probably related to hybrid immunity, the result of vaccination plus infection, a combination described in the literature as capable of provoking a more potent immune response than isolated immunity, by infection or vaccination (21,22).

When we compared the anti-N reactivity in urine and serum among vaccinated individuals, it was higher among individuals with previous infection. However, urinary anti-N accuracy in distinguishing prior infection among vaccinated individuals was inferior (AUC=0.603, p=0.03) when compared to urinary anti-S eukaryotic (AUC= 0,729, p<0.0001) and to urinary anti-S prokaryotic (AUC=0.6737, 0,00027). This could be possibly explained using the reasoning of hybrid immunity, which generates anti-S in greater quantities than isolated vaccine immunity. Therefore, depending on the cutoff point for urinary anti-S, vaccinated individuals with prior infection can be distinguished from vaccinated individuals without prior infection.

A direct weak correlation was found between the dosages of anti-N and anti-S in urine and serum (

Table 1). The weakness of the correlation can be explained by the fact that urine concentrations may vary and they were not controlled in this study. The strongest correlation was between urinary commercial anti-S and in-house anti-S (r=0.694, p<0.001). Their AUCs also had similar values. The second strongest correlation was between urinary anti-N and urinary anti-S in-house (r-0.584, p<0.001). These correlations reinforce the validation of the method.

Our results showed that age, sex, number of doses, and time of the last dose did not influence the absorbance values found for the N and S proteins. This finding goes against the literature data, which describes that these are determining factors in the amount of IgG (22,23). The analysis of the factors "time after the immunizing event" and "number of doses" may have been compromised by the sample size, which did not allow a sufficient "n" in each time and dose category. Age and sex may not have been impactful due to sample size and the groups being practically similar concerning these variables. Another possible explanation is that this immunodiagnostic methodology, never described in this studied population, has different characteristics from studies already published (22,23).

A limitation of the study was the absence of an unvaccinated group with a previous mild infection. We had no access to samples from such patients when this study was performed. It could have brought additional conclusions about the vaccinated group with a previous mild infection, comparing the response to isolated infection versus the hybrid immune response. Another limitation is the sample size, which did not allow for comparison of post-immunizing event time categories (vaccine or infection). This is relevant, as the amount of antibodies decays over time (24). Finally, this study only included patients vaccinated with one type of COVID-19 vaccine. Analyzing urinary anti-SARS-CoV-2 in individuals vaccinated with different COVID-19 vaccines would add important insights.

A strength of this study is the confirmation of the possibility of using urine samples to detect anti-S and anti-N in the vaccinated population. The results found in urine and serum samples corroborate the findings of other studies (12–14). Although this method cannot currently be used to diagnose COVID-19, because almost the entire population has antibodies in response to either the vaccine or previous infection, this work shows that antibody dosage in urine has diagnostic potential and should be further explored.

In clinical practice, the use of urine to detect antibodies can be considered more convenient compared to venipuncture, since it allows patients to collect their own samples and eliminates the risks involved in handling blood and the need for trained phlebotomists for collection. Once improved, antibodies detection in urine can be used in the initial clinical and epidemiological management of possible new epidemics.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG): APQ-02167-21 and RED-0067-23 (Rede Mineira de Imunobiológicos); and by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq): 402417/2023-2 and implementation of fellowship BP-100/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and regulatory standards for research involving human beings expressed in resolution 466/12, in force in Brazil, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais under CAAE number 30437020.9.0000.5149.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are available in: supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used the help of Gemini 1.0.0 for the purposes of translation from Portuguese to English. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Itoh M, Weerasooriya MV, Qiu G, Gunawardena NK, Anantaphruti MT, Tesana S, et al. Sensitive and specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of Wuchereria bancrofti infection in urine samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. Oct 2001;65(4):362–5. [CrossRef]

- Joshi MS, Chitambar SD, Arankalle VA, Chadha MS. Evaluation of Urine as a Clinical Specimen for Diagnosis of Hepatitis A. Clin Vaccine Immunol. Jul 2002;9(4):840–5. [CrossRef]

- Itoh M, Ohta N, Kanazawa T, Nakajima Y, Sho M, Minai M, et al. Sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with urine samples: a tool for surveillance of schistosomiasis japonica. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. Sep 2003;34(3):469–72.

- Vázquez S, Cabezas S, Pérez AB, Pupo M, Ruiz D, Calzada N, et al. Kinetics of antibodies in sera, saliva, and urine samples from adult patients with primary or secondary dengue 3 virus infections. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. May 2007;11(3):256–62. [CrossRef]

- Eamudomkarn C, Sithithaworn P, Kamamia C, Yakovleva A, Sithithaworn J, Kaewkes S, et al. Diagnostic performance of urinary IgG antibody detection: A novel approach for population screening of strongyloidiasis. PloS One. 2018;13(7):e0192598. [CrossRef]

- Gong Y, Li Q, Yuan Y. Accuracy of testing for anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG in urine for H. pylori infection diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. Apr, 28th, 2017;7(4):e013248.

- Ejazi SA, Bhattacharya P, Bakhteyar MAK, Mumtaz AA, Pandey K, Das VNR, et al. Noninvasive Diagnosis of Visceral Leishmaniasis: Development and Evaluation of Two Urine-Based Immunoassays for Detection of Leishmania donovani Infection in India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. Oct 2016;10(10):e0005035. [CrossRef]

- Asfaram S, Hosseini Teshnizi S, Fakhar M, Banimostafavi ES, Soosaraei M. Is urine a reliable clinical sample for the diagnosis of human visceral leishmaniasis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol Int. Oct 2018;67(5):575–83. [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka F, Yamazaki T, Akashi-Takamura S, Itoh M. Detection of Urinary Antibodies and Its Application in Epidemiological Studies for Parasitic Diseases. Vaccines. Jul 12th, 2021;9(7):778. [CrossRef]

- Katsuragi K, Noda A, Tachikawa T, Azuma A, Mukai F, Murakami K, et al. Highly sensitive urine-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibody to Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. Dec 1998;3(4):289–95. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M, Li M, Yang Y, Guo Z, Sun Y, Shao C, et al. A comprehensive analysis and annotation of human normal urinary proteome. Sci Rep. Jun 8th, 2017;7(1):3024. [CrossRef]

- Ludolf F, Ramos FF, Bagno FF, Oliveira-da-Silva JA, Reis TAR, Christodoulides M, et al. Detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in urine samples: A noninvasive and sensitive way to assay COVID-19 immune conversion. Sci Adv. May 13th, 2022;8(19):eabn7424. [CrossRef]

- Ramos FF, Bagno FF, Vassallo PF, Oliveira-da-Silva JA, Reis TAR, Bandeira RS, et al. A urine-based ELISA with recombinant non-glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 spike protein for detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies. Sci Rep. Mar, 16th, 2023;13(1):4345. [CrossRef]

- Ramos FF, Pereira IAG, Cardoso MM, Bandeira RS, Lage DP, Scussel R, et al. B-Cell Epitopes-Based Chimeric Protein from SARS-CoV-2 N and S Proteins Is Recognized by Specific Antibodies in Serum and Urine Samples from Patients. Viruses. Sep, 5th, 2023;15(9):1877. [CrossRef]

- Larkin HD. Urine Test Detects SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. JAMA. 14 de junho de 2022;327(22):2182. [CrossRef]

- Ramos FF. Desenvolvimento de teste diagnóstico não invasivo capaz de detectar anticorpos anti-SARS-CoV-2 em urina. 2022.

- Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, Cárdenas V, Shukarev G, Grinsztejn B, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. Jun 10th, 2021;384(23):2187–201. [CrossRef]

- Szczepanek J, Skorupa M, Goroncy A, Jarkiewicz-Tretyn J, Wypych A, Sandomierz D, et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG against the S Protein: A Comparison of BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1 nCoV-2019 and Ad26.COV2.S Vaccines. Vaccines. Jan 10th, 2022;10(1):99. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. N Engl J Med.Aug 12th, 2021;385(7):585–94.

- Fong Y, McDermott AB, Benkeser D, Roels S, Stieh DJ, Vandebosch A, et al. Immune correlates analysis of the ENSEMBLE single Ad26.COV2.S dose vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Nat Microbiol. Dec 2022;7(12):1996–2010. [CrossRef]

- Decru B, Van Elslande J, Steels S, Van Pottelbergh G, Godderis L, Van Holm B, et al. IgG Anti-Spike Antibodies and Surrogate Neutralizing Antibody Levels Decline Faster 3 to 10 Months After BNT162b2 Vaccination Than After SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Healthcare Workers. Front Immunol. 2022;13:909910.

- Van Elslande J, Kerckhofs F, Cuypers L, Wollants E, Potter B, Vankeerberghen A, et al. Two Separate Clusters of SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant Infections in a Group of 41 Students Travelling from India: An Illustration of the Need for Rigorous Testing and Quarantine. Viruses. May 31st, 2022;14(6):1198. [CrossRef]

- Khan SR, Chaker L, Ikram MA, Peeters RP, van Hagen PM, Dalm VASH. Determinants and Reference Ranges of Serum Immunoglobulins in Middle-Aged and Elderly Individuals: a Population-Based Study. J Clin Immunol. Nov 2021;41(8):1902–14.

- Lo Sasso B, Agnello L, Giglio RV, Gambino CM, Ciaccio AM, Vidali M, et al. Longitudinal analysis of anti-SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD IgG antibodies before and after the third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Sci Rep. May 23rd, 2022;12(1):8679. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).