1. Introduction

Campylobacter spp. are gram-negative bacteria varying in morphology from rod-, comma- or s-shape, having a single polar flagellum, bipolar flagella, or no flagellum (Kaakoush et al., 2015). Most species require microaerophilic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2) for optimal growth. Some Campylobacter spp. can grow either in microaerophilic or anaerobic conditions (Kaakoush et al., 2015). Some species, such as Campylobacter concisus, Campylobacter curvus, Campylobacter rectus, Campylobacter mucosalis, Campylobacter showae, Campylobacter gracilis, and to a certain extent, Campylobacter hyointestinalis, require the presence of hydrogen or formate in culture media.

Campylobacter species, especially C. jejuni and C. coli are the most common cause of diarrheal illness in humans (Luber et al., 2003; Gupta et al., 2004). The number of campylobacteriosis cases reported in people in Canada was roughly ten thousand each year during 2006-2015, a rate of approximately 27 cases per 100,000 population (Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), 2015). In the United States there are an estimated 2.4 million cases annually (Gupta et al., 2004). C. jejuni appears to cause 95% of diagnosed campylobacteriosis cases in people (Butzler, 2004). Most Campylobacter infections are mild and self-limiting with symptoms of acute watery or bloody diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps and weight loss (Kaakoush et al., 2015). However, infections may become severe and prolonged especially in patients whose immune systems are compromised (Luangtongkum et al., 2010).

Campylobacter spp. is transmitted to human from various sources such as untreated drinking water, contaminated meat products or direct contact with live animals (Di Giannatale et al., 2019). Poultry production is recognized as a reservoir and main source of human Campylobacter infection, especially infection caused by C. jejuni (Rath et al., 2021). C. jejuni is a common commensal species in chicken gut microbiome (Hakeem et al., 2021). Broiler meat caused 20%–30% of human infections while 50%–80% was presumably from chicken reservoir as a whole (Di Giannatale et al., 2019). Pig production is also another Campylobacter reservoir and mainly associated with C. coli (Rath et al., 2021).

Erythromycin (macrolide) is the drug of choice for C. jejuni campylobacteriosis in people because of high effectiveness, low toxicity and ease of administration. Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin) are the second choice for treatment because of broad spectrum activity (Altekruse et al., 1999). Alternative antibiotic choices such as chloramphenicol, clindamycin, aminoglycosides and carbapenems are effective against Campylobacter spp. Despite effective treatments the prevalence of resistant strains may complicate empirical treatment of campylobacteriosis (Lehtopolku et al., 2012). All antimicrobials used to treat campylobacteriosis are considered to be of very high importance (Category I) or high importance (Category II) for human medicine (Government of Canada, 2009). The use of Category I and II antimicrobials is now prohibited fin poultry for preventive treatment (Anon, 2016).

The aim of this study was to characterize antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and genotypes Campylobacter strains isolated from commercial broiler chicken production in Alberta during the period of 2015-2016. The mobility of AMR phenotypes was also observed using conjugation assays.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial isolation and speciation

Four pooled fecal samples from one randomly selected barn per farm were collected in 2015 and 2016, as part of the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance program - CIPARS (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015). In total, 68 fecal samples were collected from 17 flocks of broiler chickens in Alberta, Canada (

Table S1). Pooled fecal samples were sent on ice in coolers to Alberta Agriculture and Forestry for bacterial isolation and speciation.

Campylobacter was isolated using the standard CIPARS methodology, which is as follows: 25 g portion of each composite fecal sample was mixed with 225 mL of buffered peptone water (BPW) and incubated at 35 ± 1°C for 24 hours. The BPW mixture was serially diluted with Bolton broth (BB) in the ratios of 1:100 and 1:1000, then incubated in a microaerophilic atmosphere at 37°C for 4 hours. After that, they were incubated at 42°C for 20 to 24 hours. The BB tube contents were next streaked on modified Charcoal Cefoperazone Deoxycholate Agar (mCCDA) plates, followed by microaerophilic incubation at 42°C for 72 hours. Finally, presumptive Campylobacter colonies were identified using biochemical tests (Gram stain, catalase test, oxidase test) and multiplex PCR for speciation.

The multiplex PCR speciation of

C. jejuni and

C. coli was performed as previously described (Persson & Olsen, 2005). Three pairs of oligo primers were added into the PCR mix (

Table 1).

The bacterial isolates were then shipped to University of Calgary for further characterization. Mueller-Hinton agar/broth (MHA/MHB) (Becton Dickinson - BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used to recover these isolates. Campylobacter was cultured under microaerophilic condition at 37°C for 3 days or at 42°C for 2 days. Microaerophilic conditions were achieved by placing activated sachets in a BD BBL GasPakTM jar (BD GasPakTM EZ Campy Container System, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with inoculated growth medium.

2.2. Antimicrobial susceptibility assays

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for Campylobacter were determined by broth microdilution assay as part of the CIPARS program and was performed by Public Health Agency Canada (PHAC). The detailed procedure was previously described in a previous report by PHAC (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015). Briefly, the CAMPY plates designed by NARMS and containing 9 dehydrated antimicrobials were used. After incubation period, plates were read using the Sensititre Vizion System. The MIC values obtained were compared with those of CLSI standards.

The MIC values for transconjugants were also determined using a broth microdilution method. Sensititre™ Campylobacter MIC plates (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada). Strains were streaked on Mueller-Hinton agar plates and incubated in microaerophilic conditions at 37°C for 72 hrs or 42°C for 48 hrs. Several colonies were selected and inoculated into 5 ml Sensititre™ cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth with TES buffer - CAMHBT (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada) and adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland Standard using a Sensititre™ nephelometer. The inoculated CAMHBT was then mixed well, and subsequently 100 µl was transferred into Sensititre cation adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth with TES buffer and lysed horse blood - CAMHBT+ LHB (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada). The inoculated CAMHBT + LHB was mixed, and 100 µl was inoculated into each well on MIC plate using Sensititre™ Auto-Inoculator. The microtiter plate was incubated in microaerophilic conditions at 37°C for 48 hours before reading results using the Sensititre™ Manual Viewer. For interpretation of manually read results we followed MIC Interpretive guidelines as provided by the CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), 2017).

2.3. Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA extraction was performed using a previously published method with modifications (Meade et al., 1982). Briefly, overnight culture was harvested, re-suspended in 500 μl TES (10 mM Tris, 25 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and lysed using lysis solution (20 μl of 25% SDS, 50 μl of 5 mg/ml of predigested Pronase E and 50 μl of 5 M NaCl) at 68°C for 30 minutes. Proteins were precipitated by adding 260 μl of 7.5 M ammonium acetate to the lysate kept on ice for 20 minutes. Precipitated protein was separated from the lysate by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes. DNA was extracted from the lysate supernatant by adding chloroform of the same volume and subsequent centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 mins. After centrifugation, the top layer was transferred to a new tube containing 780 μl of isopropanol and the mixture was incubated on ice for 30 mins to precipitate DNA. DNA was pelleted, washed with 500 μl of 70% ethanol and pelleted again at 13,000 rpm for 1 min. After the supernatant was discarded, DNA was dissolved in 50 μl of TE buffer.

2.4. PCR assay to detect AMR gene

A PCR assay was performed on genomic DNA prep to determine the presence of

tetA,

tetO and

cmeB genes with previously published primers (

Table 1).

Conjugation Assay

All C. jejuni isolates displaying various resistance patterns selected for conjugation assays were from the 2015 sampling. The C. jejuni isolate number 13.3, with MDR phenotype: azithromycin/clindamycin/erythromycin/telithromycin (AzClErTl) was used for mating assays with four randomly picked C. jejuni isolates (6.3, 33.3, 85.3, 96.3) that displayed resistance to tetracycline (Te). The donor and recipient strains were mated in the ratio of 1:1 on MHA plates (Tran et al., 2021). After 3-day incubation at 37°C, conjugation spots were transferred to selective media: MHA plates supplemented with erythromycin (5 µg/ml) and tetracycline (5 µg/ml), to select for transconjugants. Conjugation spots were also spotted individually onto MHA plates and then transferred to selective media (MHA plates supplemented with erythromycin (5 µg/ml) and tetracycline (5 µg/ml)), as negative controls.

In a second conjugation experiment, the C. jejuni isolate number 96.3 which had a ciprofloxacin/nalidixic acid/tetracycline resistance phenotype (CiNaTe) was used as the donor in a mating assay with three isolates (No. 13.3, 113.3, 117.3) which had the AzClErTl resistance phenotype. The conjugation protocol was similar to the protocol mentioned above, except for the use of different selective media. In this conjugation experiment, the selective medium was MHA supplemented with erythromycin (5 µg/ml) and nalidixic acid (15 µg/ml).

A third conjugation experiment was performed similarly as described in the second conjugation using the same donors and recipients, except for selective media. In the third conjugation, selective media were MHA supplemented with erythromycin (5 µg/ml), tetracycline (5 µg/ml) and nalidixic acid (15 µg/ml).

Statistical analyses

All analysis was completed in Stata 15 (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess resistance to different antimicrobials between 2015 and 2016.

3. Results

3.1. Flock characteristics

Sixty-five

Campylobacter isolates were isolated from fecal samples in 17 flocks over two years. Just eight isolates were

C. coli, all of which were detected in 2016. Resistance to one or more drugs was detected in 9/17 flocks. Two flocks had isolates that were either susceptible or intermediate to all drugs, and isolates from the remaining six flocks were susceptible to all drugs tested. Chicks originated from three different hatcheries; however, 80% were from the same hatchery. Two flocks reported no use of antibiotics, the remaining 15 flocks were conventionaly raised (i.e. reported using antibiotics). Management practices, including methods used to clean barn and water lines, and antimicrobials used in flocks are summarized (

Table S1). The most commonly used antibiotics were bacitracin (n = 14), salinomycin (n = 9) and monensin (n = 5).

3.2. Distribution frequency and minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) for Campylobacter spp. isolates from 2015 and 2016

All 2015 isolates (100%, 41/41) were

C. jejuni, while in 2016 there were 66.7%

C. jejuni (16/24) and 33.3%

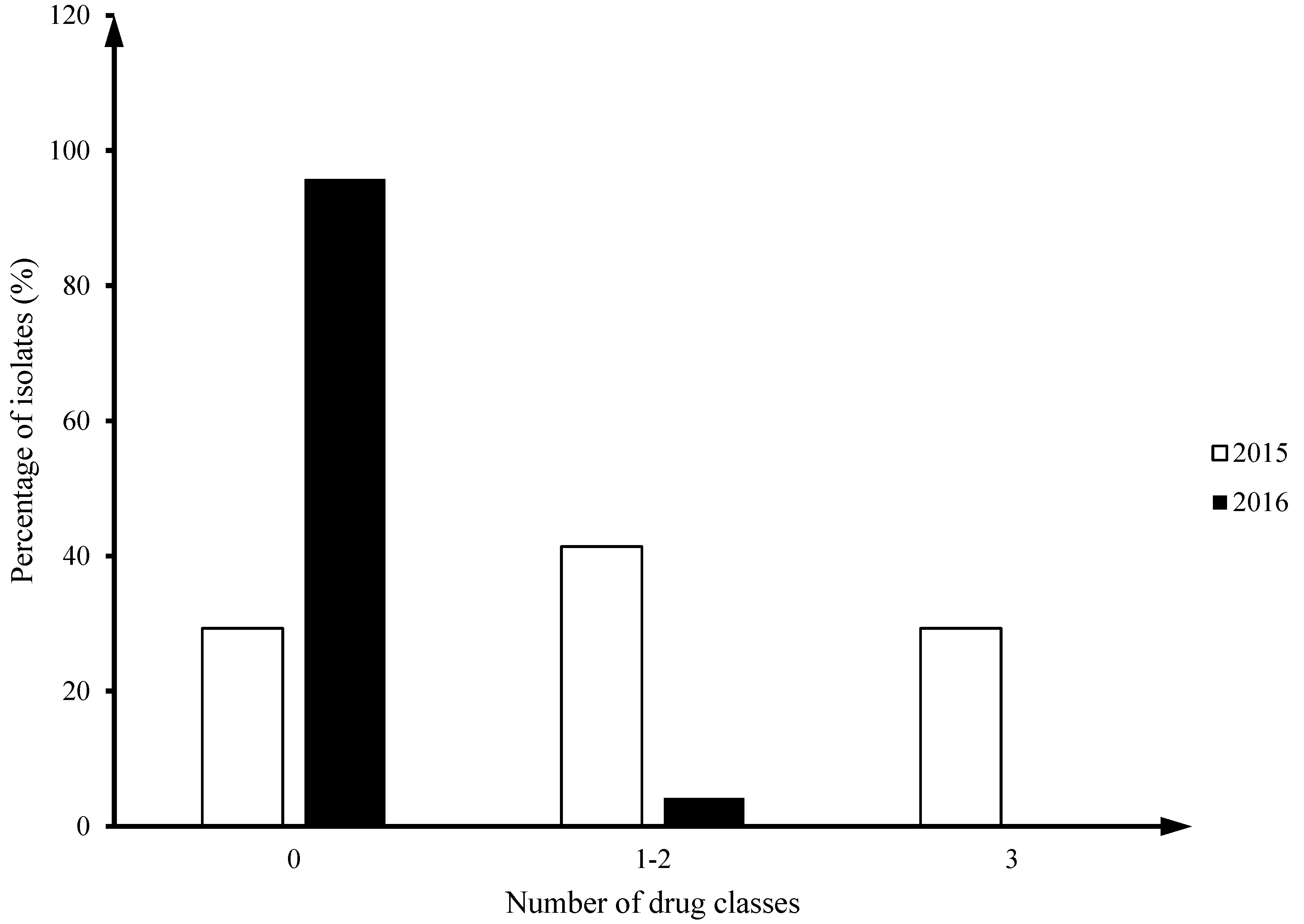

C. coli (8/24). Twenty nine percent of

Camplyobacter jejuni isolates from 2015 (12/41) had multiclass drug resistance (MDR; ≥ 3 drug classes), but no MDR isolates were identified in 2016 (

Figure 1).

The distribution of MICs around the resistance breakpoint for each antimicrobial showed that some isolates in 2015 had MICs larger than the maximum value of the tested range (

Table 2): TEL (12/12), NAL (1/41), ERY (12/41), AZM (12/41). All 2016 isolates had MIC of all antimicrobials falling within the tested range (

Table 2).

The association between resistance to individual drugs and year of isolation was examined in C. jejuni using Fisher’s exact test. A significant difference in the number of resistant isolates from 2015 (17/41, 41% ) to 2016 (1/24, 4%) was detected for tetracycline (P = 0.011), and the pattern of telithromycin, erythromycin, clindamycin and azithromycin resistance (P = 0.013).

3.3. Resistance patterns of Campylobacter isolates from 2015 and 2016

Two main resistance patterns found in Campylobacter isolates from 2015 were azithromycin/clindamycin/erythromycin/ telithromycin resistance (AzClErTlR - pattern 1, drug classes: macrolide-lincosamide-ketolide) and tetracycline resistance (TeR – pattern 2, drug classes: tetracycline). In 2015, 39% (16/41) exhibited TeR pattern, and 29% (12/41) exhibited the AzClErTlR pattern. There was only one isolate 96.3 which displayed resistance to ciprofloxacin/nalidixic acid/tetracycline resistance (CiNaTeR, drug classes: quinolone-tetracycline).

C. jejuni isolates with the resistance pattern AzClErTlR were identified in three flocks in 2015. All three flocks obtained their chicks from the same hatchery, and all three farms used salinomycin for treatment of coccidiosis. These farms had the same floor space area (8,000 ft2) and stocking density (0.54 ft2 per bird), used Ross 308 birds, and were all multi-age facilities (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015). Sanitation on these three farms was done using a hot water wash between productions periods, with chlorine in a pressurized form used as the disinfectant of choice. These three farms did not disinfect their water lines between flocks but did use chlorine to treat the water lines during the production cycle (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015).

Out of 16 C. jejuni isolates collected in 2016, there was only one isolate which had resistance to Tetracycline (TeR). The rest 15 C. jejuni and 8 C. coli isolates in 2016 were pan-sensitive.

3.4. Detection of AMR genes

All TeR isolates from the 2015 batch (n=17) harbored tetO gene as determined by PCR assay and sequence analysis. The tetO nucleotide sequence had 99% agreement with the sequence encoding TetM/TetW/TetO/TetS family tetracycline resistance protein published in the GenBank database (Accession No. CP023546.1). The tetA gene sequence was not detected in any of our Te resistant isolates. For the PCR assays, C. jejuni isolate 13.3 with the AzClErTlR pattern was included as a negative control as no tetO gene was amplified from this tetracycline sensitive isolate.

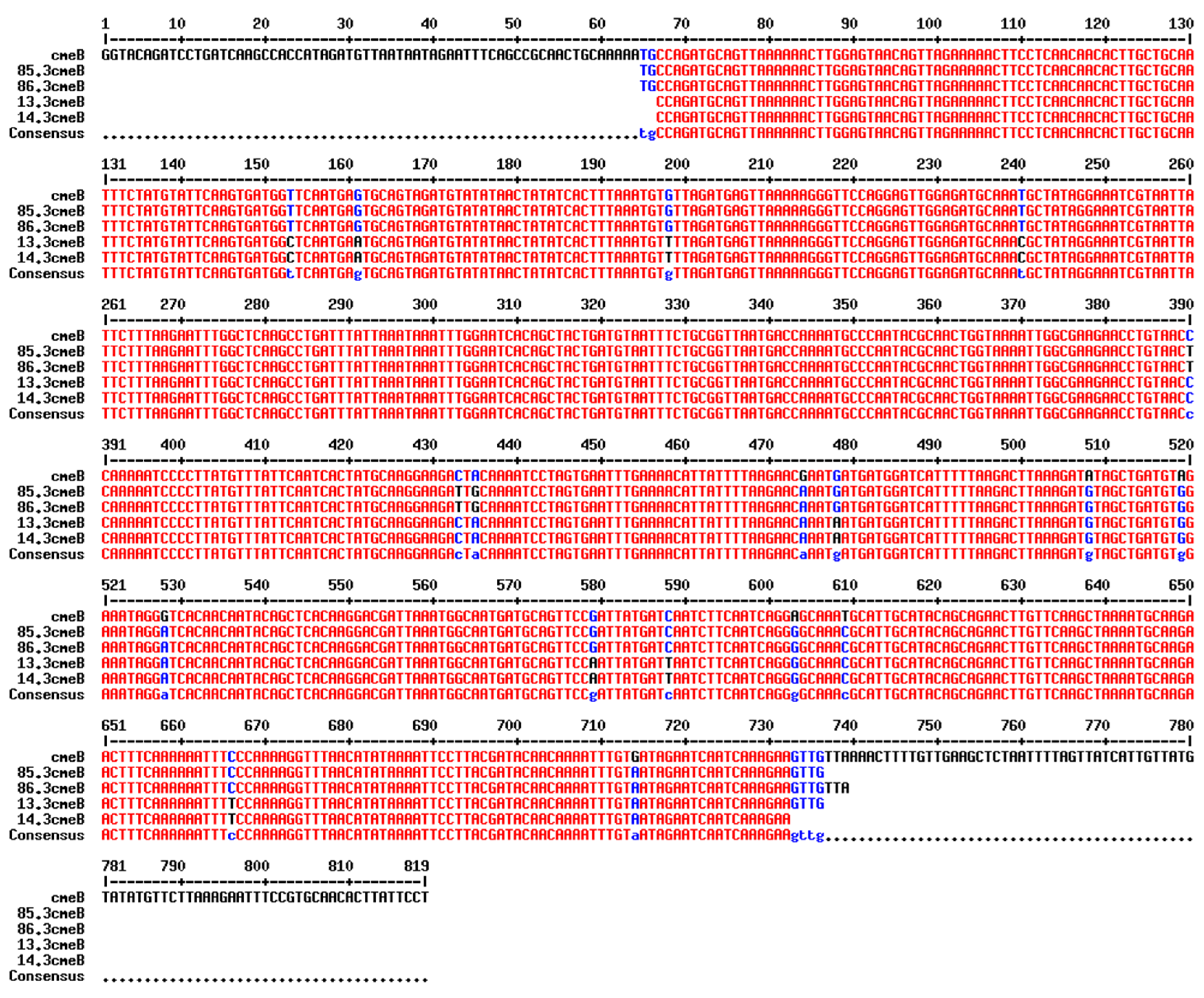

The

cmeB gene was detected in all

C. jejuni strains collected in 2015 which had the AzClErTl

R pattern (n=12). In addition, out of five

C. jejuni isolates which had other resistance patterns (Te

R and CiNaTe

R), the

cmeB gene was detected in two Te

R C. jejuni isolates. Alignment of the

cmeB nucleotide sequence obtained by PCR revealed that isolates with the same resistance pattern (AzClErTl

R or Te

R) shared the same nucleotide sequence and single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the

cmeB gene (

Figure 2). The

cmeB gene was not detected in a

C. jejuni isolate with the CiNaTe

R pattern nor in two

C. jejuni isolates with Te

R pattern.

3.5. Campylobacter jejuni antimicrobial resistance phenotypes transferred via in vitro conjugation

Three out of four

C. jejuni isolates from 2015 with either Te

R or CiNaTe

R were able to produce transconjugants when mated with the

C. jejuni isolate from 2015 with AzClErTl

R pattern (

Table 3). The AMR pattern (AzClErTlTe

R) of transconjugants 13.6, 13.85 and 13.96 was then confirmed by antimicrobial susceptibility assay (

Table 3). All the transconjugants were characterized as having a combined AMR pattern of Te from the donor and AzClErTl from the recipient strain. Although all of the transconjugants had phenotypic resistance to clindamycin, their MICs (MIC = 8 µg/ml) were half of the parental isolate’s original MIC value (MIC = 16 µg/ml). The isolate (96.3) which had the CiNaTe

R pattern was in contact with the isolates of AzClErTl

R pattern producing tranconjugants of the combined resistance pattern (AzClErTl

R + Te

R). All the transconjugants had the same MICs for nalidixic acid as the parental isolate 13.3. These MICs (8 and 16 µg/ml) were higher than MICs in two of the likely donor isolates 6.3 and 85.3 (MIC ≤ 4 µg/ml), but lower than the MIC (MIC > 64 µg/ml) of likely recipient isolate 96.3.

In the second conjugation assay, three isolates (13.3, 113.3 and 117.3) with AzClErTl

R pattern were mated with the isolate 96.3 with CiNaTe

R pattern (

Table 3). All transconjugants displayed the combined patterns CiNa

R + AzClErTl

R but they were all susceptible to Te; and two of them had an increased MIC (16 µg/ml) for ciprofloxacin as compared to the parental strain (8 µg/ml).

In the third conjugation, the presence of tetracycline in the selective media helped maintain Te resistance in the transconjugants. Presumable C. jejuni donors (13.3, 113.3 and 117.3) with AzClErTlR pattern was mated with the presumable C. jejuni recipient 96.3 with CiNaTeR pattern and selected on medium containing tetracycline. The transconjugants had a combined multi-drug resistance pattern of CiNaTeAzClErTl (Fluoroquinolones – CiNa, Tetracycline – Te, Macrolides – AzEr, Lincosamide – Cl, Ketolide – Tl).

4. Discussion

Campylobacter jejuni was the only Campylobacter species identified in samples from broiler production in Alberta in 2015, while both C. jejuni (66.7%) and C. coli (33.3%) were identified in samples collected in 2016. Overall, C. jejuni was the predominant Campylobacter species isolated, which is similar to a previous study (Luber et al., 2003). This is a clinically grave concern in humans when considering the fact that the majority (95 to 98%) of human cases of Campylobacter gastroenteritis were caused by C. jejuni , followed by C. coli cases (2 to 5 %) (Taylor & Courvalin, 1988; Luber et al., 2003). Thirty years ago very few Campylobacter strains (< 1%) in Canada and the United Kingdom were resistant to erythromycin (Taylor & Courvalin, 1988). In contrast, our study showed almost 30% of C. jejuni isolates from poultry in 2015 having phenotypic resistance to erythromycin. In addition, while other studies otherwise reported that C. coli was more likely to be associated with macrolide resistance, macrolide resistance phenotype was only found in C. jejuni isolates in our study (Bolinger & Kathariou, 2017).

Tetracycline-resistant isolates were found to make up 41% of 2015 Campylobacter isolates. The tetO gene was identified in all our 2015 C. jejuni isolates (n = 17) with phenotypic resistance to tetracycline. This result is similar to previous studies where the tetO gene was identified as the most common tetracycline resistance gene in all C. jejuni and C. coli isolates with resistance to tetracycline (Dasti et al., 2007; Abdi-Hachesoo et al., 2014; Pratt & Korolik, 2005). Transmissible plasmids carrying the tetO gene have been found not only in C. jejuni and C. coli but also in other bacteria such Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus spp. (Zilhao et al., 1988). These tetO-carrying conjugative plasmids were also associated with genes encoding for different aminoglycoside inactivating enzymes, transposase- like genes, and multiple other genes (Nirdnoy et al., 2005; Marasini et al., 2020). The tetO gene can also be located on the bacterial chromosome, especially in C. coli (Dasti et al., 2007; Pratt & Korolik, 2005). The phenotypes of our transconjugants imply that the tetO gene in some of our isolates is plasmid-encoded and transmissible. The isolate that was unable to transfer the tetracycline resistance phenotype to the recipient might carry a chromosomally encoded tetO gene, or the gene may be located on a separate mobile element which was not transferred.

The cmeB gene encodes for an inner membrane efflux transporter and is a part of three-gene operon (designated cmeABC) that contributes to multidrug resistance in C. jejuni (Lin et al., 2002). It was shown that mutation of the cmeB gene resulted in decreasing MICs to a wide range of antimicrobial agents (i.e. ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, erythromycin, tetracycline), heavy metals and bile salts between 2 and 4,000-fold. In these cmeB mutant strains resistance to ciprofloxacin was decreased 8-fold, resistance to nalidixic acid decreased 2-fold, to erythromycin decreased 4-fold, and tetracycline resistance decreased 8-fold, (Lin et al., 2002). In our study, the cmeB gene (819 bp) was selected for screening in a subset of Campylobacter isolates, especially the ones with AzClErTl phenotype because the gene was likely to confer resistance to antibiotics of different classes. All isolates with AzClErTl resistance pattern carried the cmeB gene. The cmeB gene was also present in two C. jejuni isolates with Te resistance pattern. However, they did not share the same sequence identity of cmeB genes with C. jejuni isolates of AzClErTl resistance pattern. A significant increase of cmeB mutations in C. jejuni strains carrying cmeB gene compared to those in the CmeB null mutant strains at 10X and 32X the concentration (Yan et al., 2006). However, there were no further investigation of these mutations in their study.

In this study, only one C. jejuni isolate was resistant to ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid and tetracycline. The cmeB gene was not detected in the C. jejuni isolate with the CiNaTe phenotype although this gene was shown to be associated with the resistance to ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid and tetracycline in several previous studies (Lin et al., 2002; Ge et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2006). We postulate that some mutation in the gyrA gene most likely accounted for the resistance to flouroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and nalixidic acid) in this isolate because these drugs target the DNA gyrase encoded by gyrA gene (Aksomaitiene et al., 2018; Hakanen et al., 2002).

In the first conjugation assay, the transconjugants with a combined resistance pattern (AzClErTl + Te) can be made by mating isolates of AzClErTl and Te phenotypes. Based on the MICs of transconjugants, isolates with Te phenotypes were likely to be the donors which transferred Te phenotype into the recipient isolate 13.3 with AzClErTl phenotype. In the second conjugation assay, isolate 96.3 with CiNaTe phenotype was used as the recipient and mated it with isolates exhibiting AzClErTl resistance pattern to determine the transferability of AzClErTl phenotype. Interestingly, the transconjugants displayed resistance not only to erythromycin, which was used as a selection marker, but also to azithromycin, clindamycin, and telithromycin. More surprisingly, all transconjugants maintained resistance to CiNa but lost resistance to Te after conjugation. It is well-known that the strains normally suffer a fitness cost to maintain plasmids; therefore, they can easily lose plasmids in antibiotic-free environment (Millan & Maclean, 2017). In the last conjugation experiment, we wanted to see if the transconjugants still maintain resistance to Te when we added tetracycline into the media in addition to nalidixic acid and erythromycin. The results suggested that they were able to maintain resistance to all antimicrobials provided that selection pressure was present in the media.

In conclusion, the study isolated and speciated Campylobacter isolates from broiler chickens in Alberta. In both years, C. jejuni was the predominant species isolated, and C. coli was only isolated in 2016. Twenty nine percent of C. jejuni isolates from 2015 (12/41) had multiclass drug resistance (MDR) (≥ 3 drug classes), but no MDR isolates were identified in 2016. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms were found in the cmeB gene of isolates of different resistance patterns. We also showed the potential for resistance pattern transfer during conjugation. The demonstration of transmission of multi-drug resistance via conjugation between strains supports the importance of continued antimicrobial resistance surveillance in food borne pathogens.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1. Flock level characteristics including antibiotics given in feed and methods used to disinfect barns.

Author Contributions

SC, KL, SG, CM conceptualized the research idea and obtained research funding. AAF (PI :SC). SG and AA developed the CIPARS AMU-AMR farm surveillance framework, farm surveillance tools (questionnaire) and protocols, and validated the recovery and AMR datasets. Bacterial isolation and initial antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed by RC. TT and KL were responsible for experimental design. TT conducted research and laboratory analysis. NC conducted statistical analysis. TT and NC designed and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript development. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Alberta Agriculture and Forestry (AAF) [grant number 2015R025R] with significant in a kind support from PHAC and the AAF, Agri-Food Laboratories.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the poultry veterinarians and producers who voluntarily participated in the CIPARS farm surveillance program and enabled data and sample collection. We are grateful to the Chicken Farmers of Canada and the Alberta Chicken Producers for their valuable input to the framework development and technical discussions. TT also wishes to thank Odd-Gunnar Wikmark and the Norwegian Research Council (MARMIB - project number 315812) for their support in finishing this work.

Conflicts of Interest

Competing interests: The authors declare there are no competing interests.

References

- Abdi-Hachesoo, B., Khoshbakht, R., Sharifiyazdi, H., Tabatabaei, M., Hosseinzadeh, S. & Asasi, K. 2014. Tetracycline resistance genes in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli isolated from poultry carcasses. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology, 7(9): 7–11.

- Aksomaitiene, J., Ramonaite, S., Olsen, J.E. & Malakauskas, M. 2018. Prevalence of Genetic Determinants and Phenotypic Resistance to Ciprofloxacin in Campylobacter jejuni from Lithuania Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9: 1–6.

- Altekruse, S.F., Stern, N.J., Fields, P.I. & Swerdlow, D.L. 1999. Campylobacter jejuni - An emerging foodborne pathogen. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 5(1): 28–35.

- Anon. 2016. Chicken farmers of Canada. http://www.chickenfarmers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/2016-Annual-Report-ENG-web.pdf.

- Bacon, D.J., Alm, R., Burr, D.H., Hu, L., Kopecko, D.J., Ewing, C.P., Trust, T.J. & Guerry, P. 2000. Involvement of a plasmid in virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. Infection and Immunity, 68(8): 4384–4390. [CrossRef]

- Bolinger, H. & Kathariou, S. 2017. The Current State of Macrolide Resistance in Campylobacter spp.: Trends and Impacts of Resistance Mechanisms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 83(12): 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Butzler, J. 2004. Campylobacter, from obscurity to celebrity. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 10(10): 868–876. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). 2017. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility. M45-A2.

- Dasti, J.I., Groß, U., Pohl, S., Lugert, R., Weig, M. & Schmidt-Ott, R. 2007. Role of the plasmid-encoded tet(O) gene in tetracycline-resistant clinical isolates of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 56(6): 833–837. [CrossRef]

- Di Giannatale, E., Calistri, P., Di Donato, G., Decastelli, L., Goffredo, E., Adriano, D., Mancini, M. E., Galleggiante, A., Neri, D., Antoci, S., Marfoglia, C., Marotta, F., Nuvoloni, R., & Migliorati, G. 2019. Thermotolerant Campylobacter spp. in chicken and bovine meat in Italy: Prevalence, level of contamination and molecular characterization of isolates. PloS one, 14(12), e0225957. [CrossRef]

- Ge, B., Mcdermott, P.F., White, D.G., Meng, J. & Hemother, A.N.A.G.C. 2005. Role of Efflux Pumps and Topoisomerase Mutations in Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli., 49(8): 3347–3354. [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. 2009. Categorization of Antimicrobial Drugs Based on Importance in Human Medicine. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/veterinary-drugs/antimicrobial-resistance/categorization-antimicrobial-drugs-based-importance-human-medicine.html.

- Gupta, A., Nelson, J.M., Barrett, T.J., Tauxe, R. V., Rossiter, S.P., Friedman, C.R., Joyce, K.W., Smith, K.E., Jones, T.F., Hawkins, M.A., Shiferaw, B., Beebe, J.L., Vugia, D.J., Rabatsky-Ehr, T., Benson, J.A., Root, T.P. & Angulo, F.J. 2004. Antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter strains, United States, 1997-2001. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(6): 1102–1109.

- Hakanen, A., Jalava, J., Kotilainen, P., Jousimies-somer, H., Siitonen, A. & Huovinen, P. 2002. gyrA Polymorphism in Campylobacter jejuni: Detection of gyrA Mutations in 162 C. jejuni Isolates by Single-Strand Conformation Polymorphism and DNA Sequencing. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 46(8): 2644–2647.

- Hakeem, M. J., & Lu, X. 2021. Survival and Control of Campylobacter in Poultry Production Environment. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 10, 615049. [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O., Castaño-Rodríguez, N., Mitchell, H.M. & Man, S.M. 2015. Global epidemiology of campylobacter infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 28(3): 687–720. [CrossRef]

- Lehtopolku, M., Kotilainen, P., Puukka, P., Nakari, U.M., Siitonen, A., Eerola, E., Huovinen, P. & Hakanen, A.J. 2012. Inaccuracy of the disk diffusion method compared with the agar dilution method for susceptibility testing of Campylobacter spp. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 50(1): 52–56. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Michel, L.O. & Zhang, Q. 2002. CmeABC Functions as a Multidrug Efflux System in Campylobacter jejuni. Society, 46(7): 2124–2131. [CrossRef]

- Luangtongkum, T., Jeon, B., Han, J., Plummer, P., Logue, C.M. & Zhang, Q. 2010. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiology, 4(2): 189–200.

- Luber, P., Wagner, J., Hahn, H. & Bartelt, E. 2003. Antimicrobial Resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Strains Isolated in 1991 and 2001-2002 from Poultry and Humans in Berlin, Germany. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 47(12): 3825–3830. [CrossRef]

- Marasini, D., Karki, A.B., Bryant, J.M., Sheaff, R.J. & Fakhr, M.K. 2020. Molecular characterization of megaplasmids encoding the type VI secretion system in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from chicken livers and gizzards. Scientific Reports, 10: 12514. [CrossRef]

- Meade, H.M., Long, S.R., Ruvkun, G.B., Brown, S.E. & Ausubel, M. 1982. Physical and Genetic Characterization of Symbiotic and Auxotrophic Mutants of Rhizobium meliloti Induced by Transposon Tn5 Mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol, 149(1): 114–122. [CrossRef]

- Millan, A.S.A.N. & Maclean, R.C. 2017. Fitness Costs of Plasmids : a Limit to Plasmid Transmission. Microbiol Spectrum, 5(5): 1–12.

- Nirdnoy, W., Mason, C.J. & Guerry, P. 2005. Mosaic structure of a multiple-drug-resistant, conjugative plasmid from Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 49(6): 2454–2459. [CrossRef]

- Persson, S. & Olsen, K.E.P. 2005. Multiplex PCR for identification of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni from pure cultures and directly on stool samples. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 54: 1043–1047. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A. & Korolik, V. 2005. Tetracycline resistance of Australian Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 55(4): 452–460. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. 2015. Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial (CIPARS) Annual Report 2015. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/aspc-phac/HP2-4-2015-eng.pdf.

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). 2015. Canadian Notifiable Disease Section. http://diseases.canada.ca/notifiable/charts?c=pl.

- Rath, A., Rautenschlein, S., Rzeznitzeck, J., Breves, G., Hewicker-Trautwein, M., Waldmann, K. H., & von Altrock, A. 2021. Impact of Campylobacter spp. on the Integrity of the Porcine Gut. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI, 11(9), 2742. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.E. & Courvalin, P. 1988. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter. Antimicrob.Agents Chemother., 32(8): 1107–1112. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T., Checkley, S., Caffrey, N., Mainali, C. & Gow, S. 2021. Genetic Characterization of AmpC and Extended-Spectrum Beta- Lactamase Phenotypes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella From Alberta Broiler Chickens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 11(March): 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M., Sahin, O., Lin, J. & Zhang, Q. 2006. Role of the CmeABC efflux pump in the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter under selection pressure. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 58(October): 1154–1159. [CrossRef]

- Zilhao, R., Papadopoulou, B. & Courvalin, P. 1988. Occurrence of the Campylobacter resistance gene tetO in Enterococcus and Streptococcus spp. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 32(12): 1793–1796. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).