2.1. Context-Free Grammars (CFG)

In Chapter 1, we use finite automata and regular expressions to describe regular languages. In this chapter, we introduce the concept of Context-Free Grammar which is a more powerful tool for describing languages.

A Context-Free Grammar is formally defined as follows.

Definition 2.1. A Context-Free Grammar denoted by is a 4-tuple , where

- (i)

is a finite set of variables;

- (ii)

is a finite set of terminals such that ;

- (iii)

is the start variable; and

- (iv)

is a finite relation

For any , we usually write and call it a rule.

Accordingly, the relation is also called the set of rules for the .

is sometimes called the head of the rule whereas is called the body of the rule.

Example 2.2. Let

Let consist of the following rules:

is a .

The following are examples of strings in that can be derived by .

Definition 2.3. Let

be a .

For any , we say yields (or is derivable from ) in one step (written as or simply ) if and only if

and a rule such that and .

Note that the process of deriving from is basically a replacement of a variable in by the body of the variable’s rule to obtain .

In addition, we define iff .

For any integer , we say yields (or is derivable from ) in steps (written as ) iff such that and .

If there are more than one to be considered, (e.g. and ) and if we need to distinguish between derivations in from derivations in , we can write

to mean is derivable from in steps by use of rules in ; and

to mean is derivable from in steps by use of rules in .

Furthermore, if we need to specify the rule to be applied in each step, we can use

to mean is derivable from in steps by use of rules in with rule to be applied in the step; and

to mean is derivable from in steps by use of rules in with rule to be applied in the step.

Since there can be more than one way of deriving a string, it is sometimes useful to require the derivation to be leftmost. A leftmost derivation is a derivation in which the leftmost variable at every step is replaced by the body of its rule.

Formally, we define leftmost derivation as follows.

For any , is a leftmost derivation of in one step (written asor simply ) iff , , and a rule such that and .

For any integer is defined similarly as .

Definition 2.4 . Let be a ; be a subset of .

We define the relation as follows:

if and only if for some integer .

is called the length of the derivation of from .

Note that whenever there is an such that , there is a minimum such that .

If there are more than one to be considered,

if and only if for some integer .

is defined similarly as .

Proposition 2.5.

(respectively ) is reflexive and transitive.

Proof. Since for all , for all .

Therefore, is reflexive.

For transitivity, assume and .

There exist integers and such that

and .

There are two cases to examine, or

By definition, .

Since , .

Therefore,

for some .

With a backward induction argument, we have

for some .

We now have

.

Since ,

,

With a forward induction argument, we have

.

Finally, .

Therefore, .

Combining (i) and (ii), is transitive.

With a similar argument, we can establish is also reflexive and transitive.

Definition 2.6. Let be a .

The language of is defined as

.

Note that if , because implies which is a contradiction.

Definition 2.7. Let be a .

Let represent the rule in .

we say yields (or is derivable from ) using the rule (written as

) if and only if there exist such that and .

Proposition 2.8. Let be a .

For any and ,

- (i)

- (ii)

If there is no in such that is a rule, .

- (iii)

If and , then appears in appears in .

- (iv)

Let , where for all , and .

If and appears in for some then such that is a rule.

Proof.

- (i)

-

If is a rule, since is in , .

Therefore, .

Conversely if , such that and

and is a rule.

Since , must be and .

Therefore, and becomes .

- (ii)

-

Assume for contradiction that .

such that or . (Note that .)

By (i), or .

This contradicts the assumption that there is no in such that is a rule.

- (iii)

-

Since , such that , and is a rule.

Since is not a rule .

Since appears in , appears either in .

In either case, appears in .

- (iv)

-

Assume for contradiction which appears in for some such that is not a rule for all .

By (iii), appears in .

By repeated application of (iii), we can conclude that appears in and , which is a contradiction because contains no variables.

Example 2.9. Let be a .

Create the rules in so that .

The rule is as can be seen from the following applications of the rule.

(1st application of )

(2nd application of )

(3rd application of )

( application of )

(Application of )

Example 2.10. Let be a .

Create the rules in so that .

The rule is as can be seen from the following applications of the rule.

(1st application of )

(2nd application of )

(3rd application of )

( application of )

(Application of )

Example 2.11. Let be a .

Create the rules in so that .

The rule is as can be seen from the following applications of the rule.

(1st application of )

(2nd application of )

(3rd application of )

( application of )

(Application of )

Definition 2.12. Let

be a

.

Let be rules in where .

and are equivalent if there exists such that if and only if

Proposition 2.13.

- (i)

if and only if is a rule.

- (ii)

If does not appear in and does not appear in and is a rule, then

.

Proof.

- (i)

If is a rule, and therefore, .

- (ii)

If , since , by definition . Therefore, .

Conversely, if , by definition is a rule.

Conversely, if , such that and .

Since does not appear in and does not appear in , there is only one appearance of in .

Therefore, there is only one appearance of in .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Proposition 2.14.

& are equivalent if and only if & .

Proof. If & are equivalent,

(Proposition 2.13)

Since & are equivalent, .

There exist such that and .

since and are both variables.

.

Therefore, .

Conversely, if & , & are the same rule and hence they are equivalent.

Proposition 2.15. Let be a .

and , are equivalent to .

Proof., let

be

be

be If , such that Since , and for some .

Since , .

That is, .

Therefore, such that .

Since , .

That is, .

Therefore, .

Conversely, if , and for some .

Let .

Since , .

Since , .

Therefore, .

That is, .

That is, Combining both directions, and are equivalent.

Proposition 2.16. Let be a .

- (a)

, , if then .

- (b)

, if then .

- (c)

, if then .

- (d)

Let .

If for , then .

In the special case of , .

(a)

By Proposition 2.8 (i), .

By definition of derivation, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

(b)

Since , , , and a rule such that

, .

Therefore, and .

Therefore, .

(c)

Since , where such that

.

( & (b))

( & (b))

( & (b))

(. & (b))

Therefore, .

(d)

( & (c))

( & (c))

( & (c))

( & (c))

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.16.

By replacing with and with , we have the following proposition.

Proposition 2.17. Let be a .

- (a)

, , if then .

- (b)

, if then .

- (c)

, if then .

- (d)

Let .

If for , then .

In the special case of , .

Proposition 2.18. Let be a .

, .

If , , , then .

Proof. The proof is by induction on .

()

If , by Proposition 2.8 (i), .

Therefore, .

()

Assume , , , .

By induction hypothesis, .

Since , by definition of derivation,

.

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.18.

Proposition 2.19. Let be a , be rules in where .

Let .

If then where the two in the two strings are the same (Note that there can be more than one in the string ) and is not the head of any rule .

(Note that when , the statement becomes

)

Proof. For ,

Since the two in the two strings are the same , replacing them with must yield two equal strings.

Therefore, .

Therefore, the statement is true for .

For , if ,

Let be the rule represented by .

By definition of yielding, such that

and .

The that appears in must also appear in .

Since does not originate from this particular , and cannot be the same object in the string or and hence there are only two cases to examine: appears in or appears in .

- (i)

-

If appears in

Let be the string obtained by replacing in with .

Since , replacing with on both sides would yield two equal strings.

That is, .

Since , replacing with on both sides would yield two equal strings.

That is, .

However, since is a rule.

Therefore, .

Therefore, the statement is true for .

- (ii)

If appears in , with a similar argument, we can show that the statement is also true for .

With the results established on and and an induction argument, we can conclude that for ,

)

Proposition 2.20. If is a and there exist , such that

, then

The # of variables in the # of steps remaining from to .

Proof. Let be the number of steps remaining from to .

We’ll prove this proposition by induction on .

(For )

Therefore, .

Since , and a rule such that

and .

Since , .

Therefore, has only one variable.

Therefore, has only one variable.

Therefore, # of variables in the # of steps remaining from to .

(For induction)

The # of steps remaining from to is .

Since , and a rule such that

and .

Let be the number of variables in .

# of variables in (# of variables in ) .

By induction hypothesis, # of variables in .

Therefore, # of variables in .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, number of variables in # of steps remaining from to .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.20.

Example 2.21. Let be a and there exist , such that

. Show that the statement

(# of variables in the # of steps remaining from to ) is not always true.

(Hint: Consider and

.)

Definition 2.22.

is a substring of (written as ) if such that

. is called the left complement of in , written as . is called the right complement of in , written as .

Proposition 2.23. For any strings such that , if , then

- (i)

& for some string

- (ii)

& for some string .

Proof.

for some strings .

for some strings .

; .

; .

for some strings & .

Therefore, .

Since , .

Therefore, and .

Therefore, and .

Therefore, and .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.23.

Definition 2.24. For any strings such that , is said to be on the left of if there exist strings such that .

Proposition 2.25. Let be a .

Let , where .

Let .

If , then where such that

where .

Hence, in no more than steps.

is called the -step expansion of within the derivation of and it is written as .

Proof. Let .

This proposition can be proved by induction on .

():

Since , and a rule such that

and .

Since , such that .

- (i)

-

If

such that .

.

Also, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, and .

Since , .

Take .

Since and is a rule, .

- (ii)

If is not a substring of Since and , either or .

Since , and .

Therefore ( or ).

Take .

Therefore, .

Combining (i) and (ii), where .

(Induction):

By induction assumption,

where and

.

Since and , by applying the same argument as in the case of (), we can find such that where .

We now have where

and .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.25.

Proposition 2.26. Let be a .

Let , where .

Let , , , & .

If is to the left of within , then is to the left of within .

.

We can prove this proposition by induction on .

()

& .

Therefore, & .

and .

is to the left of is to the left of .

The statement is true for .

(Induction)

Induction Hypothesis:

is to the left of is to the left of .

Since is to the left of , there exist such that

.

Since , there exists a rule such that

& .

We now have five situations to examine: .

- (i)

-

(Proposition 2.23)

(, )

.

Take and .

Therefore, & .

In addition, .

Therefore, is to the left of .

- (ii)

-

such that

Since , & .

Therefore, .

Take & .

Now, .

So, is to the left of .

In addition, because & .

Also, because .

- (iii)

-

With a similar argument as in (i), we can show that in such that & where and

is to the left of .

- (iv)

-

With a similar argument as in (ii), we can show that in such that & where and

is to the left of .

- (v)

With a similar argument as in (i), we can show that in such that & where and

is to the left of .

Combining all (i) to (v) and the induction hypothesis, we now have:

If is to the left of within , then is to the left of within .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.26.

Proposition 2.27. Let be a .

Let , where & .

Let .

If , then .

Proof. Since

for some .

Since , and a rule such that

& .

Since & , we have four cases to examine:

, , , .

- (i)

-

for some .

.

Since is also equal to , .

Therefore, and .

Since , .

Now we have & .

In addition, , , .

Therefore, , and .

Therefore, .

- (ii)

-

for some .

Since , .

Since , .

Therefore, and .

Since , .

Let . Then .

Since and is a rule, .

Since and , .

Since and and , .

Since , .

because is a rule.

Therefore, .

Therefore, ()

Since and , .

Therefore, .

- (iii)

-

With a similar argument as in (ii), we can show that .

- (iv)

-

With a similar argument as in (i), we can show that

.

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.27.

Proposition 2.28. Let be a .

Let , where & .

- (i)

-

For , where

.

- (ii)

-

If where & , then such that in no more than steps &

.

such that and ,

This Claim can be proved by induction on .

()

.

and .

Therefore, .

The statement is true for .

(Induction)

Induction Hypothesis:

where

.

(Induction Hypothesis)

(Proposition 2.27)

This completes the proof of Claim.

The proof of (i) is by induction on .

()

.

.

Therefore, the statement is true for .

(Induction)

Induction Hypothesis: .

(Claim)

(Induction Hypothesis)

This completes the proof of (i).

(i)

Set & for the result in (i).

,,.

Therefore, .

By (i), Therefore, .

.

Therefore, .

Therefore, for some , .

Therefore, &

in no more than steps.

Proposition 2.29. Let be a , , and .

If , then for some .

Proof.

such that .

.

(Proposition 2.28)

for some

for some (Proposition 2.25)

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.29.

Example 2.30. Prove that the non-regular set is a .

Proof. Let be a such that

, , .

In short form, .

Claim 1. If where , then

such that and and .

Claim 1 can be proved by induction on .

For , if , by definition, such that and .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, the statement is true for .

Assume the statement is true for for .

That is, for and .

For , assume .

By definition, such that

and .

By induction assumption, such that and and .

Since there are only two rules in , namely .

If we use on , then .

By Proposition 2.13 (ii), .

This contradicts the conclusion we derive above because does not contain a variable.

Therefore, we must use rule .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Again by Proposition 2.13 (ii), .

This completes the proof of Claim 1.

Claim 2.

.

For , by Proposition 2.13 (i).

Therefore, and hence the statement is true for .

For , by Proposition 2.13 (i) & (ii),

.

Therefore, .

In addition, by Proposition 2.13 (ii).

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Claim 2.

It remains to show that .

(by Claim 2)

Conversely, if , and

for some .

such that and and by Claim 1.

Since there are only two rules in , either or .

(Proposition 2.13 (ii))

a contradiction to .

Therefore, we must use .

Therefore, .

by Proposition 2.13 (ii).

Therefore, and hence .

Combining both directions, .

Before proceeding to the proof of some important theorems in , we need to review some Tree terminology and Graph Theory. The readers are assumed to have some background in the subject matter and the following are stated without proof.

T1. A tree is a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

T2. Trees are collections of nodes and edges.

T3. If is the directed edge from node to node , is called the parent and is called the child.

T4. A node has at most one parent, drawn above the node and zero or more children, drawn below.

T5. There is one node that has no parent. This node is called the root and appears at the top of the tree. Nodes that have no children are called leaves. Nodes that are not leaves are called interior nodes.

T6. A simple directed path from to is represented by where with are directed edges joining the nodes, of the tree and for . The length of the simple directed path is equal to the number of directed edges connecting the nodes and is equal to in this case.

T7. For any two nodes and , if there is a simple directed path from to , is a descendant of and is the ancestor of . Since every simple directed path from to must pass through a child of , there is simple directed path from one of children to .

T8. There is a unique simple directed path from the root to any other node.

T9. Let the length of the path from the root to a leaf. The height of the tree is defined as . Therefore, the height of a tree is the longest path from the root to a leaf.

T10. The length of the path from the root to a node is called the level of .

T11. The simple directed path from an interior node to a leaf is called a branch. The combination of all branches is the largest subtree with the interior node as the root. The length of any branch is no longer than the height of the subtree which in turn is no longer than the height of the parent tree.

T12. The children of a node are ordered from left to right. If node is to the left of node , then all the descendants of are to be to the left of all the descendants of at the same level.

T13. A subtree is a tree of which the vertices and edges are also the vertices and edges of the parent tree. If a subtree has a leaf, the leaf is also a leaf of the parent tree.

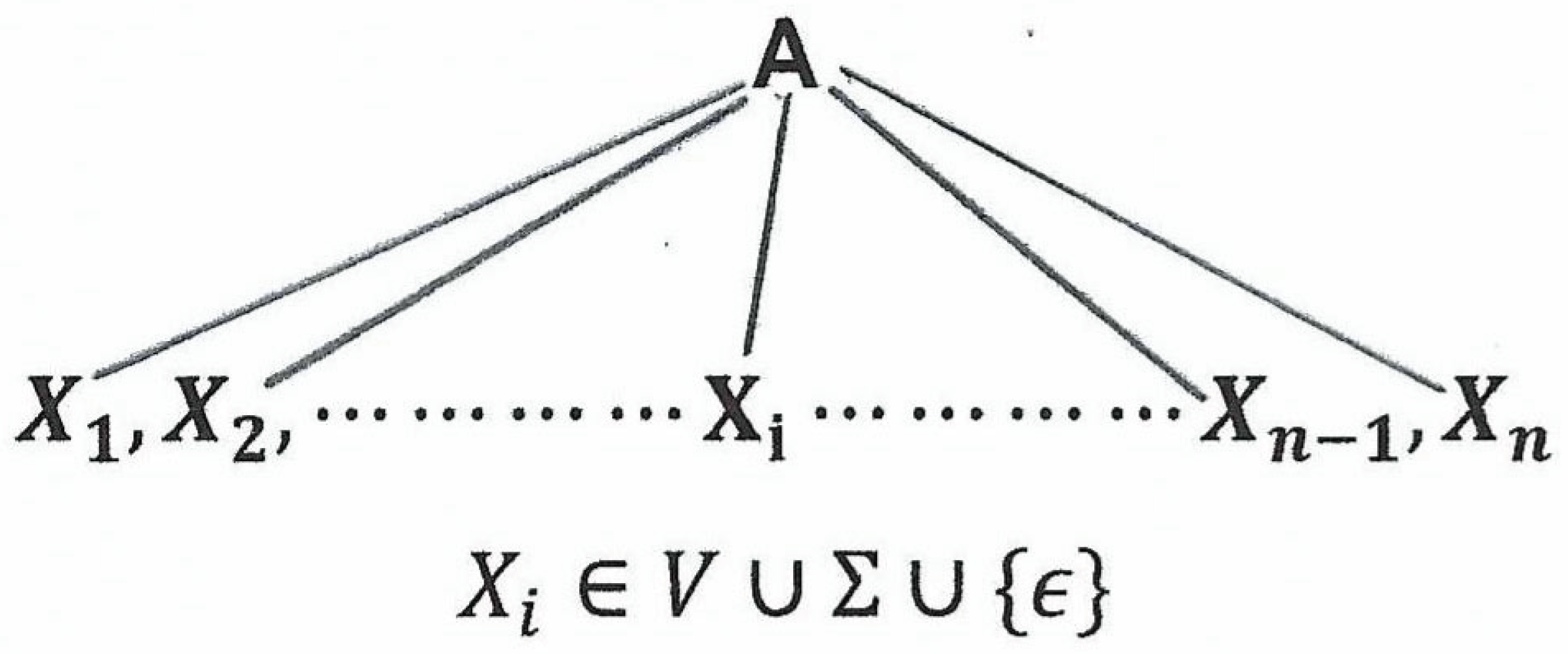

Definition 2.31. For any context-free grammar, , a parse tree for is a tree that satisfies the following conditions:

- (i)

Each interior node is labeled as a variable in .

- (ii)

Each leaf is labeled either as a variable in , a terminal in or .

- (iii)

-

If an interior node labeled (a variable) has children where for , then

is a rule in .

- (iv)

If an interior node labeled (a variable) has as a child, then is the only child of and is a rule in .

Note that any subtree of a parse tree is also a parse tree.

Definition 2.32. The yield of a parse tree is the concatenation of all the leaves of the tree from left to right.

Theorem 2.33. Let be a . The following statements are equivalent.

- (i)

a parse tree with root and a yield .

- (ii)

.

- (iii)

, .

Proof. “(i)(ii)”

This can be proved by an induction on the height of the tree in statement (i).

Let be the height of the parse tree in statement (i).

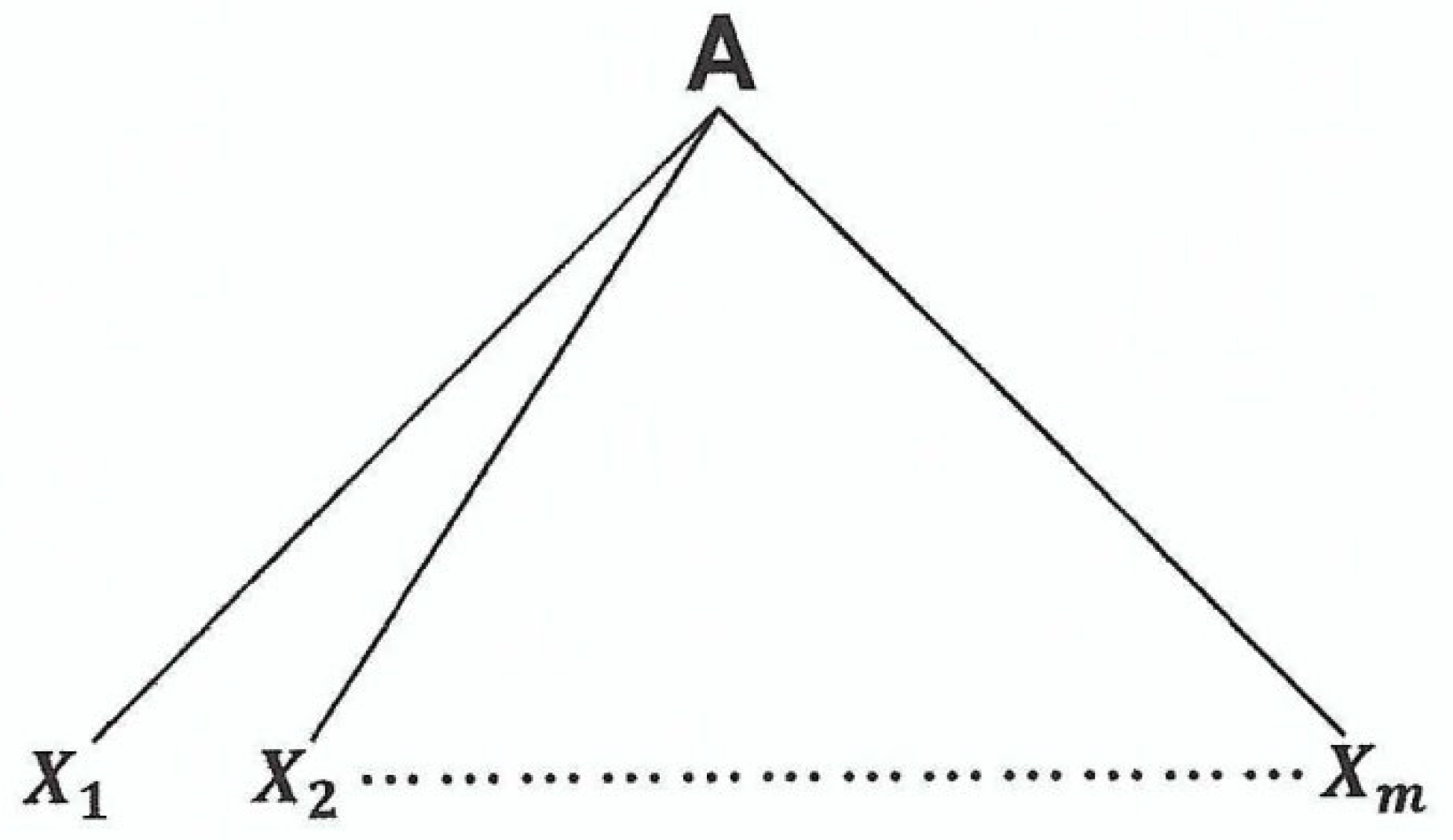

“”

The parse tree looks like the following figure.

By definition of parse tree, is a rule in .

By Proposition 2.8(i), .

Therefore, .

The yield of this tree is which is equal to by statement (i).

Therefore, .

Since is the only variable in the string , it is therefore also the leftmost variable in the string .

Therefore, .

Hence, the statement “(i)(ii)” is true for .

“Induction”

Let be an integer such that .

Induction Hypothesis:

The statement “(i)(ii)” is true for any parse tree with height if .

Consider now a parse tree that has root , yield and a height of .

This parse tree looks like the following figure.

, .

There are 2 cases to examine.

- (a)

-

for some .

.

.

( is the only variable in the head)

Furthermore, since , is a leaf.

Therefore, .

- (b)

By T11 and T13, the combination of all branches of forms a subtree of and every leaf of the subtree is also a leaf of the parent tree.

Let be the yield of .

By definition of yield, every symbol in is a leaf and therefore a symbol in .

Therefore, .

Since , .

Claim: .

By T12, is to the left of for since is to the left of .

Therefore, where .

Let be a symbol in .

is a leaf in because is the yield.

By T8, there is a simple directed path from to .

By T7, there is a simple directed path from to for some .

Since has no children, must be a leaf descendant of .

Therefore, is a symbol in because is the yield of the subtree with root .

Therefore, is a symbol in is a symbol in for some .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

This means that .

Therefore, .

Now, back to the subtree with root and yield .

The height of this subtree = the length of the longest branch in the subtree

= the length of a simple directed path in the parent tree

from to a leaf = the length of a simple directed path in the parent tree

from to a leaf minus (By T7 & is a child of )

the height of the parent tree minus = = By induction hypothesis, .

Combining (a) & (b), we now have for all and .

For the parent tree ,

(Proposition 2.8(i))

( is the only variable in the head)

Since and by Proposition 2.17,

.

Therefore, .

.

Since , .

The statement “(i)(ii)” is true for .

This completes the proof of “(i)(ii)”.

“(ii)(iii)”

The proof of this statement is trivial because every leftmost derivation is a derivation.

“(iii)(i)”

Since , such that . (Note that because and .)

The proof of this statement, “(iii)(i)”, is by induction on .

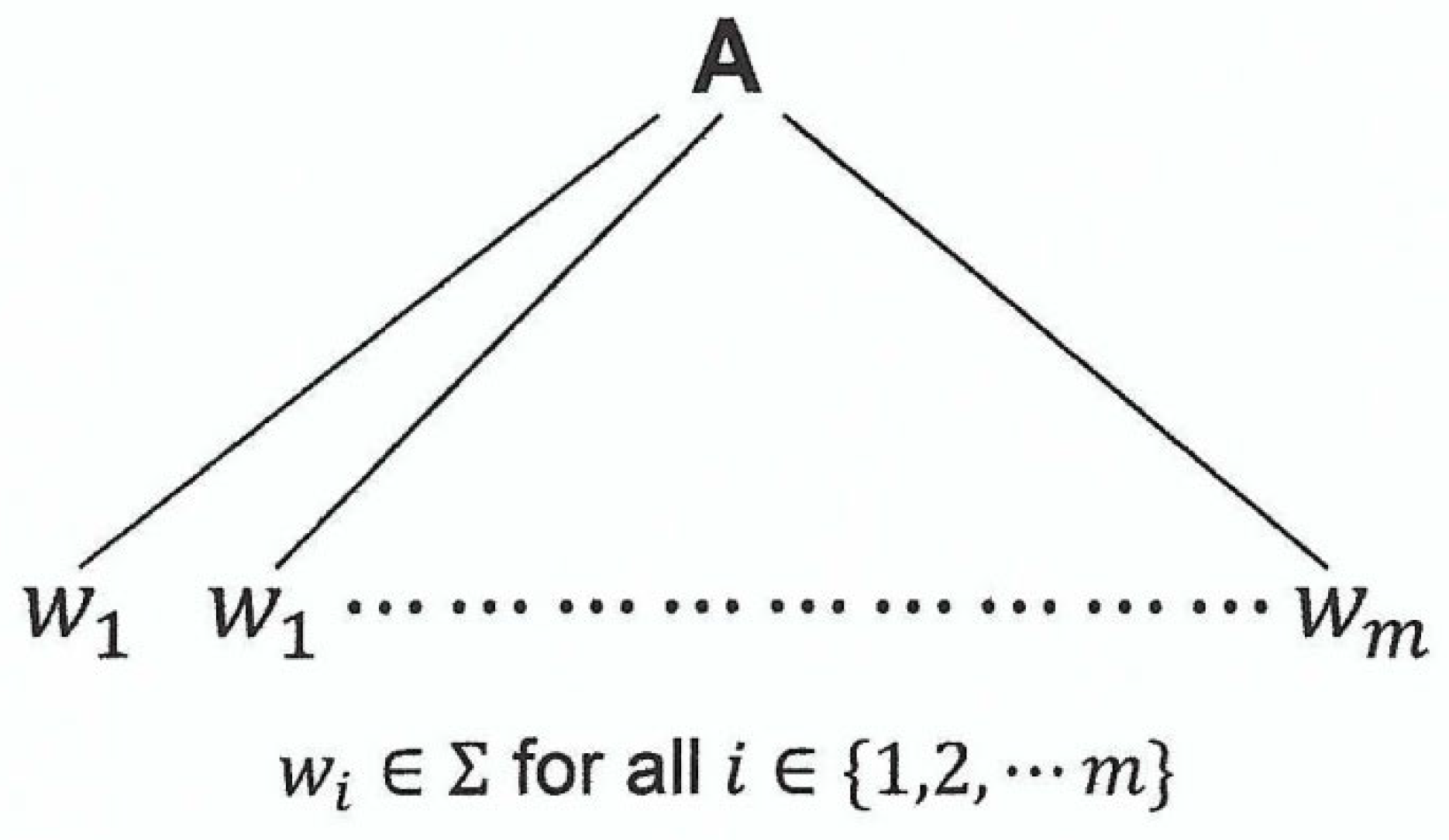

(

such that & .

By Proposition 2.8(i), .

The following is a parse tree with root and yield .

Therefore, the statement is true for .

(Induction)

Induction Hypothesis:

Let be an integer such that .

For any , if , then a parse tree with root and yield .

Now, consider .

If ,

such that

.

such that .

Therefore, .

By Proposition 2.28(ii),

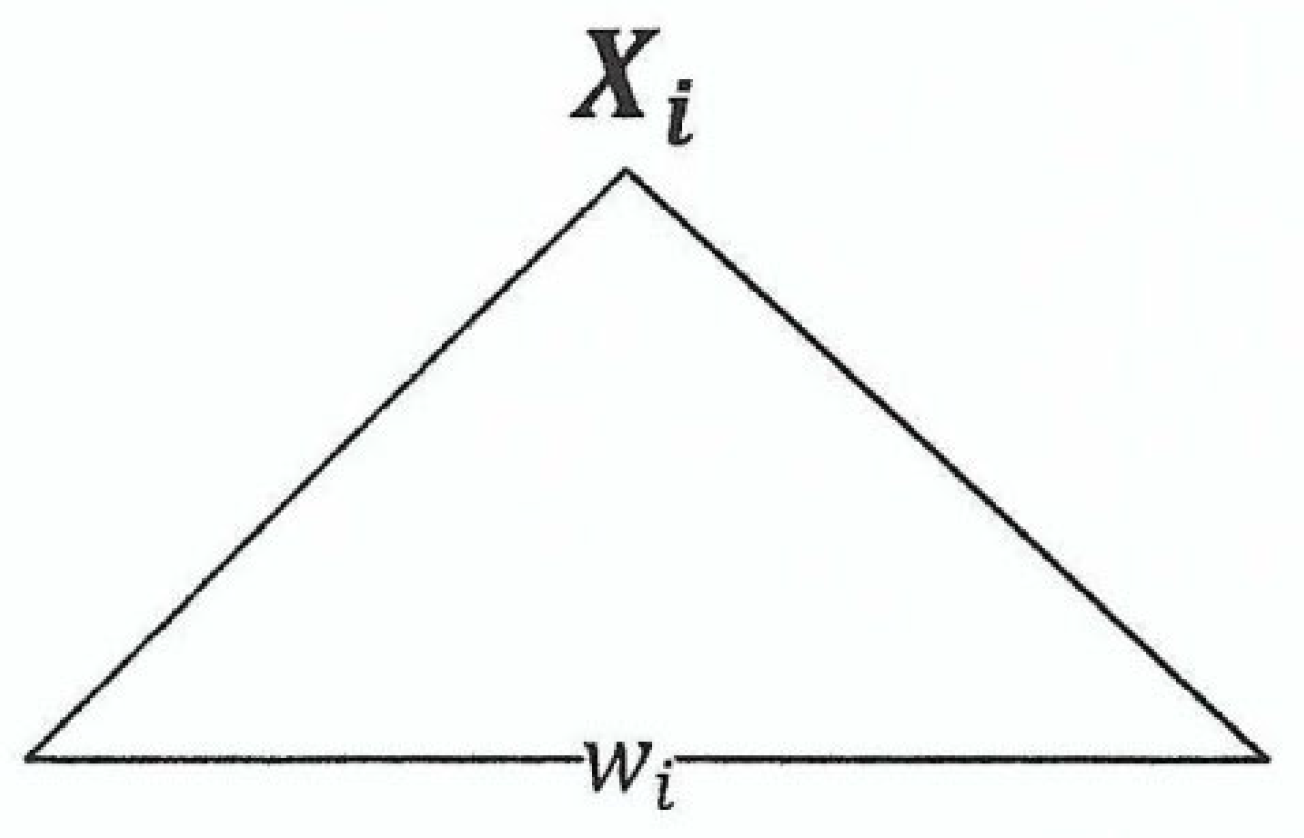

with and .

By induction hypothesis, a parse tree with root and yield which looks like the following figure.

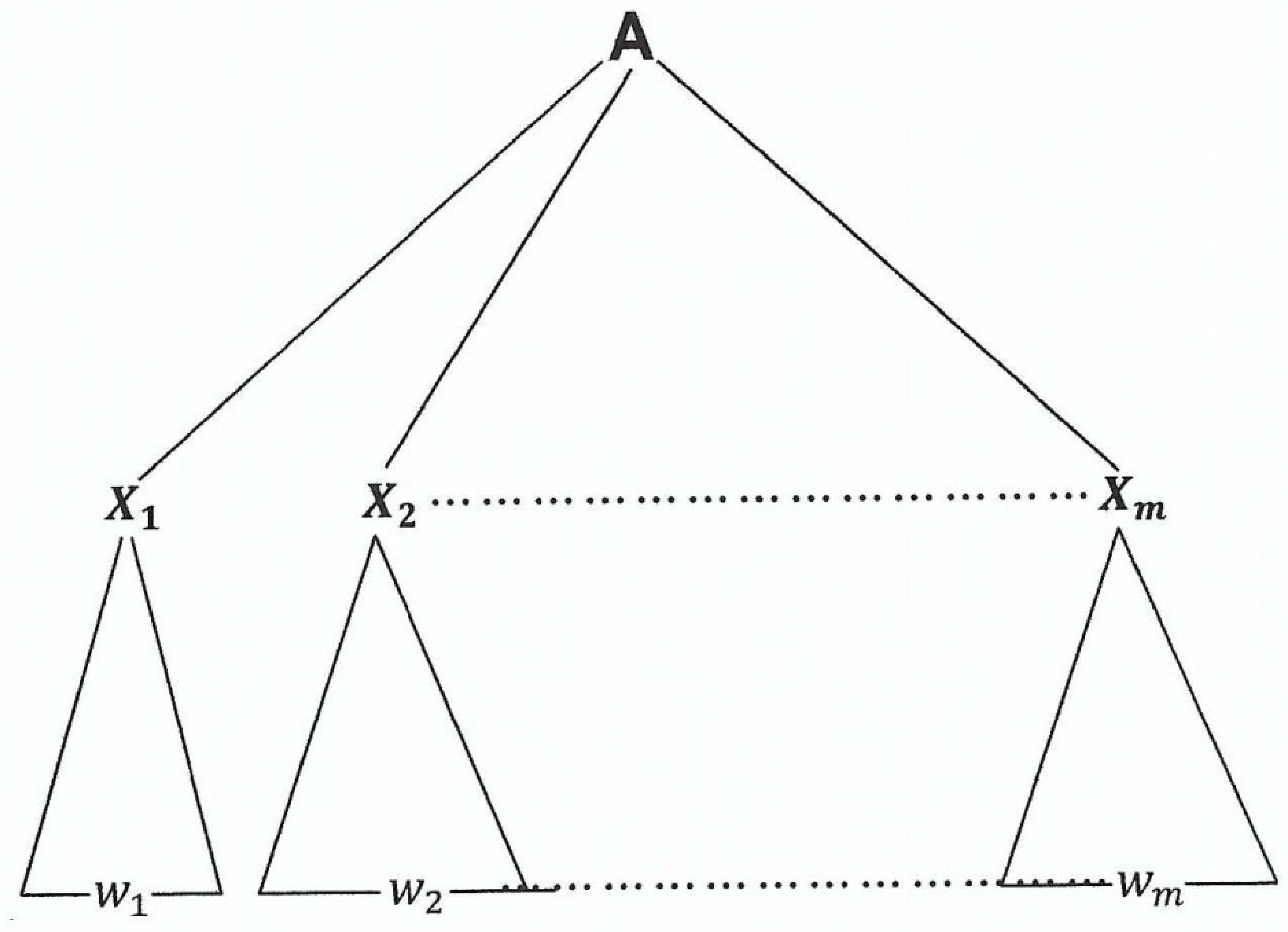

We now can construct a parse tree, as follows.

- (1)

-

Start with a one level parse tree that has root and yield that looks like the following figure.

- (2)

For each , if , set for some .

If , add the parse tree as shown in Figure 2.4 to the parse tree as shown in Figure 2.5. The resulting tree would look like the following figure.

Clearly, this tree () with root is a parse tree since the one level tree and all the subtrees with root and yield are parse trees.

In addition, since , the yield of this parse tree is .

Therefore, the statement “(iii)(i)” is true for .

This completes the proof of “(iii)(i)” and also the proof of Theorem 2.33.

2.2. Chomsky Normal Form (CNF)

Definition 2.34. Let be a .

is in Chomsky normal form if very rule of is of the following form:

where and

where

where Start Variable

Lemma 2.35. For every , there is a with no -rule ( where ) or unit rule ( where ) such that .

Proof. We can inductively construct a new set of rules, using the following procedure:

- (i)

Copy all the rules in to .

- (ii)

If and are in , create in .

- (iii)

If and are in , create in .

We can further assume that is the smallest one of all the sets that can be thus created because we can always rename the smallest one to knowing that the minimum exists.

Let .

It’s clear from construction that .

Therefore, every derivation in is a derivation in and hence .

On the other hand, every new rule that is created in is equivalent to the two rules that it is created from by Proposition 2.15 and therefore, every derivation in can be simulated by either the same rules or equivalent rules in .

Hence, .

It remains to show that all the and unit rules in are redundant for the production of any .

Since , knowing that minimum derivations exist, we can assume every derivation of is the one of minimum length.

Claim 1. Any derivation does not use an -rule.

Proof of Claim 1. Assume for contradiction that where is used at some point of the derivation.

can be rewritten as

where .

This must have been generated at an earlier point of the derivation in the form of

where .

Therefore, can be further rewritten as

where .

(Note that is a derivation in which the rule in each step does not originate from this particular .)

Since and are in , by construction (ii), is in .

Therefore, is a valid production in .

Furthermore, since , by Proposition 2.19, we can substitute for to obtain the following valid production in :

.

If we apply these two new productions at the corresponding points of the original derivation of , we have the following valid derivation:

.

We note that this new derivation of has a length of which is shorter than the original one of .

This contradicts the assumption that the original derivation is of minimum length.

Claim 2. Any derivation does not use a unit rule.

Proof of Claim 2. Assume for contradiction that a unit rule is used at some point of the derivation .

We can rewrite this derivation as

.

This must be eventually gotten rid of before reaching the final product of and the production that we need for getting rid of is:

where is a rule in .

We can now rewrite as

.

Since and are rules in , is a rule in by construction (iii).

is a valid production in .

Furthermore, since , by Proposition 2.19, we can substitute for to obtain the following valid production:

.

By applying these two new productions at the corresponding points of the derivation of , we have the following derivation:

.

This new derivation has a length of which is shorter than the original one of .

This contradicts the assumption that the original given derivation of is of minimum length.

Combining Claim 1 and Claim 2, we can conclude Lemma 2.35.

We now examine a method for converting a into one in Chomsky Normal form.

Definition 2.36 (The Method). From every , , that doesn’t have -rules or unit rules, we can construct a , using a method called Method as described in the following steps:

Step 1

For every , create a variable and a rule . Note that is a newly and uniquely created variable such that and for any such that .

Step 2

, can be expressed as where , & . Create a set of rules (called ) and a set of nodes (called ) according to the following steps:

- (i)

-

For

becomes .

Since doesn’t have any -rule, except , must be equal to and becomes .

Copy into .

In this case, and .

- (ii)

-

For

becomes .

Since doesn’t have any unit rule, .

Copy into .

In this case, and .

- (iii)

-

For

becomes .

If , copy into . In this case, and .

If & , create and add this rule and to . Add to .

(Note that was created in Step 1 above).

In this case, and .

If & , create and add this rule and to . Add to .

(Note that was created in Step 1 above).

In this case, and .

If both , create and add it along with , to . Add , to .

(Note that and were created in Step 1 above).

In this case, and .

- (iv)

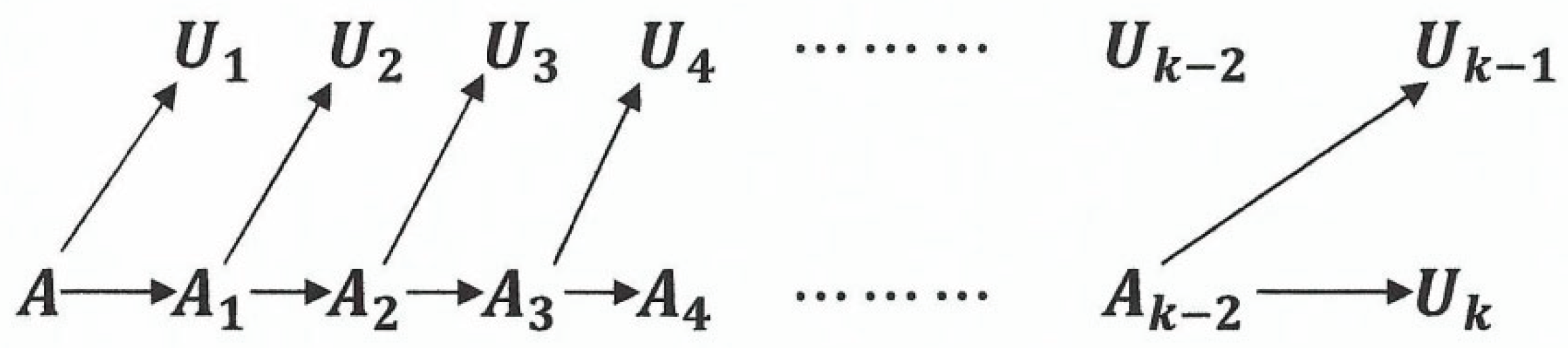

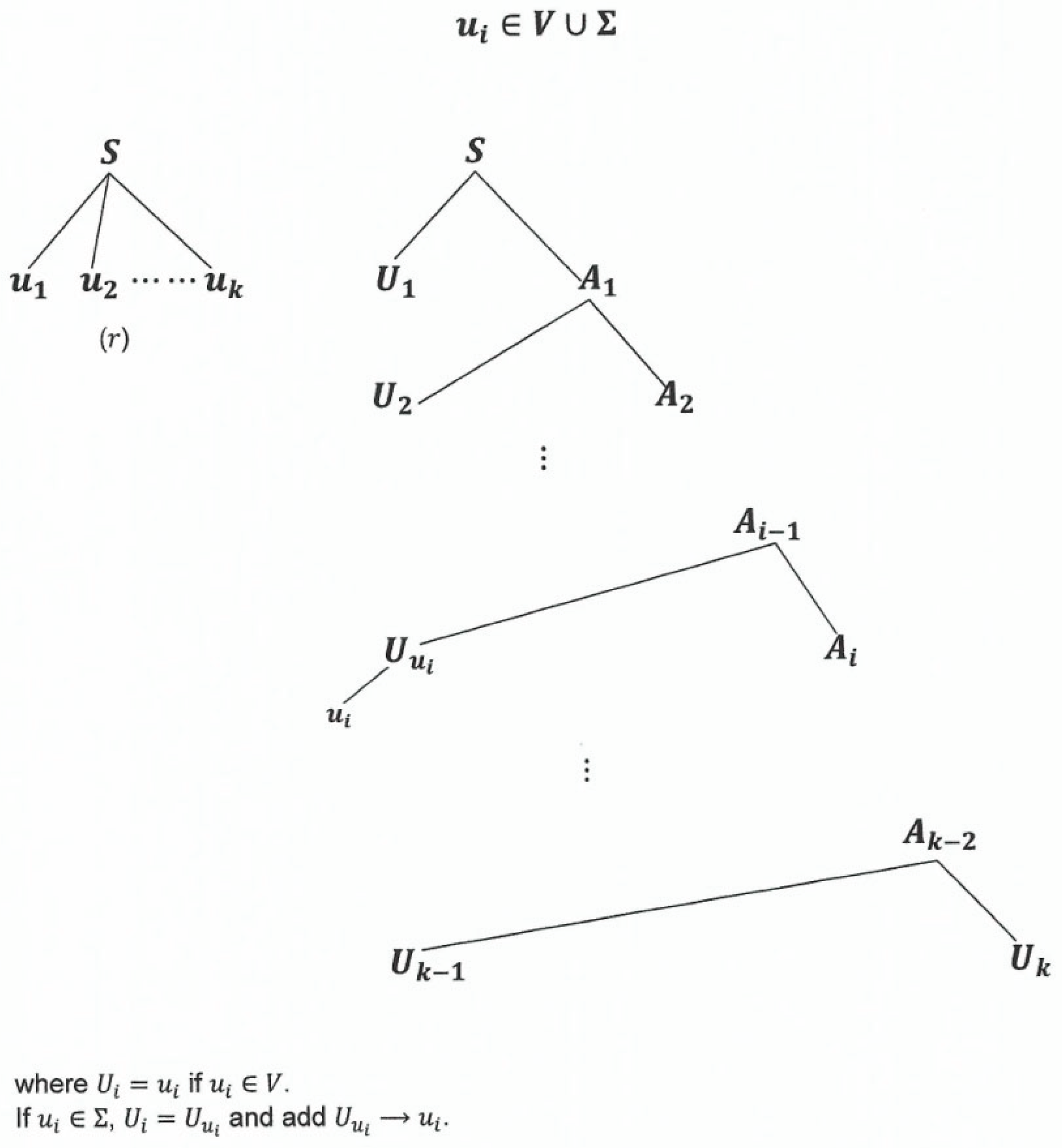

For

As depicted by the above figure, create the following rules and add them to .

where are variables newly and uniquely created for each and therefore, they are not in .

For any , if , and if , set and add to . Add to .

(Note that for each were created in Step 1 above).

In this case, includes all the rules:

and the rules for any whereas

Step 3

Set

And

We note the following properties of the rules created by Method :

N1. All the rules in are in Chomsky Normal Form.

N2. For any , there exists such that . Furthermore, for any such that .

N3. For any , is equivalent to the rules in by Proposition 2.15.

N4. and are disjoint. That is .

N5. For any , either or . Or equivalently, .

N6. , if , then is unique for . That is,

for any such that .

N7. If or , and .

N8. If or , and where .

We now have the following theorem.

Theorem 2.37. Every context-free language is generated by a in Chomsky normal form ().

Proof. Since every context-free language is generated by a , we need to show that every can be converted to an equivalent in Chomsky normal form.

Also, because of Lemma 2.35, we can start with a that has no -rule ( where ) or unit rule ( where ).

Let be the that has no -rule or unit rule except .

Let be a constructed from by use of Method .

In the following, we shall show by showing .

(If )

.

and such that

.

By N3, for any , is equivalent to a sequence of rules from which is a subset of .

Therefore, .

Note that because .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

“” (If )

.

By Theorem 2.33, a parse tree (in ) with root and a yield .

Let’s call this parse tree .

By definition of parse tree, and its children must be the head and body of a rule in .

Let’s call this rule and hence .

By N1, must be in one of the following forms:

where ,

where ,

If is , is the only child of .

Since has no children and is a descendant of , this is possible only if .

Furthermore, by construction of , in is created from in .

Therefore, is also a rule in .

Therefore, . (Proposition 2.8(i))

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, If is , since , .

Therefore, is and has only one child which is .

Since is a descendant of and has no children, .

By construction of , in is created from in .

Therefore, is also a rule in .

Therefore, is a rule in .

Therefore, . (Proposition 2.8(i))

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

If is where , Since and , .

Since , .

Therefore, becomes where .

By N2, such that .

Let be where , .

By N5, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, becomes .

We now analyze the different situations for different values of .

If , becomes .

By construction of , .

Since , is .

This contradicts the underlying assumption that is where , .

Therefore, cannot be .

If , becomes .

Since doesn’t have any unit rule, .

By construction of , .

Therefore, is where .

This contradicts the underlying assumption that is where , .

Therefore, cannot be .

Therefore, we can exclude the cases of under the assumption that is where , .

If , becomes .

By construction of , is one of the following:

- (i)

if

- (ii)

if

- (iii)

if

- (iv)

if

For (i), is .

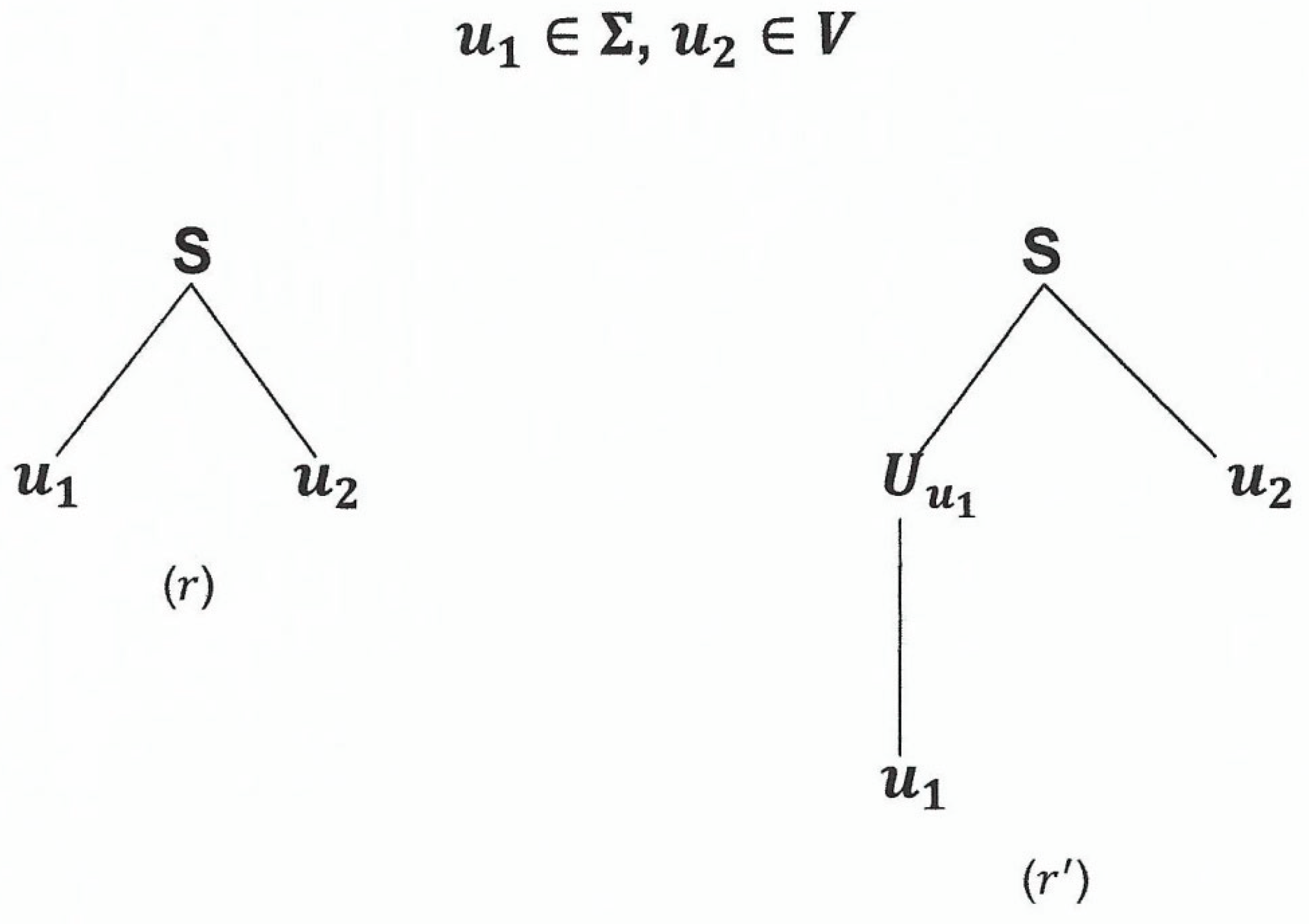

In this case, and are the same and the sub parse tree in with root and children as shown on the right of the following figure can be replaced by a parse tree in with the same root and children as shown on the left.

For (ii), is either or .

However, since which is in and , cannot be .

must be .

By N3, is equivalent to and .

We have the following equivalent parse trees with the same root and yield.

The one on the left is a parse tree in whose root and its children are the head and body of a rule in whereas the one on the right is a sub parse tree of .

Therefore we can replace a sub parse tree of with an equivalent parse tree in whose root and yield are the head and body of a rule in .

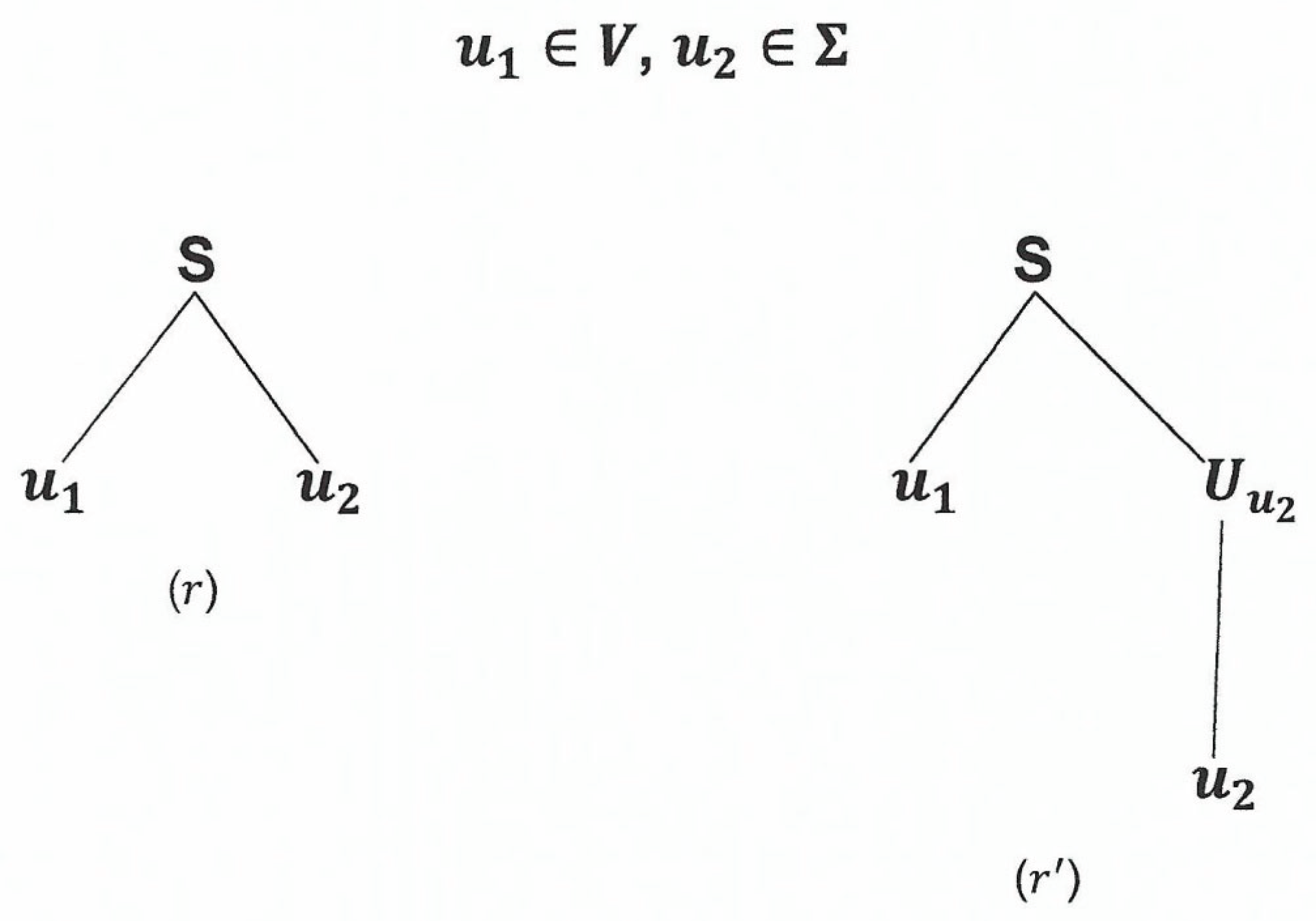

For (iii), by a similar argument, we have the following equivalent parse trees with the same root and yield.

The one on the left is a parse tree in whose root and its children are the head and body of a rule in whereas the one on the right is a sub parse tree of .

Therefore we can replace a sub parse tree of with an equivalent parse tree in whose root and yield are the head and body of a rule in .

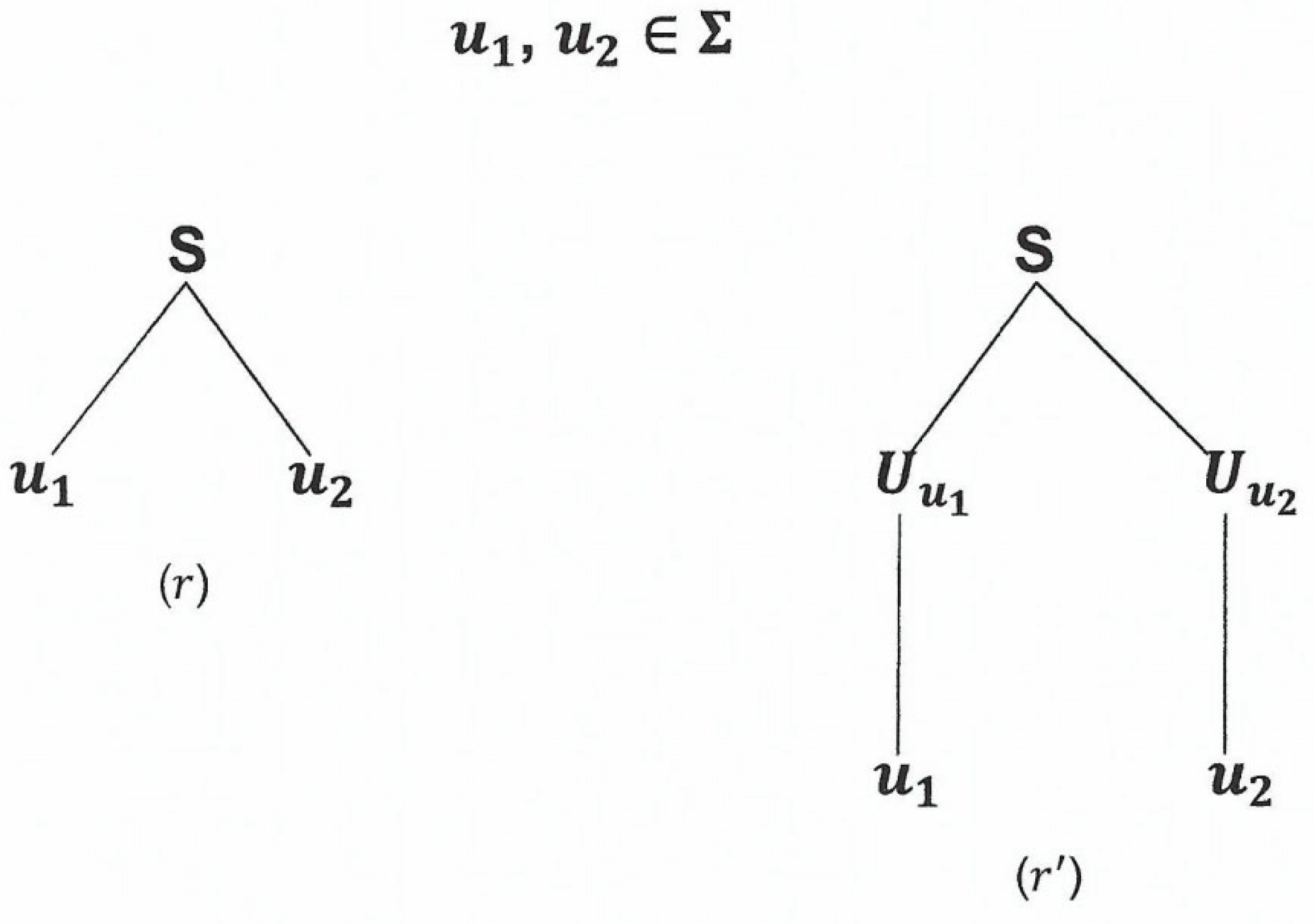

For (iv), by a similar argument, we have the following equivalent parse trees with the same root and yield.

The one on the left is a parse tree in whose root and its children are the head and body of a rule in whereas the one on the right is a sub parse tree of .

Therefore we can replace a sub parse tree of with an equivalent parse tree in whose root and yield are the head and body of a rule in .

If , is .

consists of the following rules:

if where if and if .

Since , is .

Since is a parse tree of , by definition of parse tree,

are children of .

are children of .

are children of .

are children of .

By N3, is equivalent to the sequence of rules contained in .

Therefore, we have the following equivalent parse trees with the same root and yield.

The one on the left is a parse tree in whose root and its children are the head and body of a rule in whereas the one on the right is a sub parse tree of .

Therefore we can replace a sub parse tree of with an equivalent parse tree in whose root and yield are the head and body of a rule in .

Combining all cases, we conclude that there is a sub parse tree in with root that can be replaced by an equivalent parse tree in whose root and yield are the head and body of a rule in .

We can write this rule in as where and for

(a) If all ’s are terminals

In this case, , the yield of the parent tree .

The reason is that a leaf of a subtree is also a leaf of the parent tree.

Therefore, .

On the other hand, if is a leaf in , there is a simple directed path from to . This simple directed path must pass through one of the nodes because is the yield of a sub parse tree in which is obtained by branching out from in all possible directions.

Therefore, must be one of the nodes .

After replacement, we now have a new tree which is a parse tree in , and furthermore, the root and yield of this tree are respectively and .

By Theorem 2.33, .

Therefore, .

(b) If some ’s are variables

For each that is a variable, we can repeat the above replacement process to replace the sub parse tree (with root ) in with a parse tree in whose root () and the root’s children are the head and body of a rule in .

Since every time we do a replacement, we get down to a lower level of and since the height of and the number of subtrees of are both finite, this process of replacement must come to a stop after a finite number of operations. When this happens, we have a new tree in which every interior node and its children are the head and body of a rule in . This means that the new tree thus created is a parse tree in .

Furthermore, this replacement process only affects the nodes which are variables. Therefore, the yield of , namely , is untouched and remains at the bottom after the replacement is complete.

This means that is also the yield of the newly created tree.

We now have a new tree with root and yield and the tree is also a parse tree in .

By Theorem 2.33, .

Therefore, .

Combining (a) and (b), we complete the proof of Theorem 2.37.

On the basis of Theorem 2.37 and the results proved in Lemma 2.35, we can now develop a set of operational rules for the conversion of a to one in .

Let be the to be converted.

Let be the to be created in .

Create and add it to .

(Note that this creation will ensure that the start variable will not occur on the right hand side of a rule.)

(Elimination of -rules)

If a rule in , do the following:

- (i)

-

For every rule in in the form

- (1)

-

For each single occurrence of , on the , create a rule with that occurrence deleted and add it to .

For example,

- (2)

-

For each group occurrence of on the , create a rule with that group occurrence deleted and add it to .

For example,

.

(n) For each group occurrence of on the , create a rule with that group occurrence deleted and add it to .

For example, .

- (ii)

-

Repeat (i) until all rules of the form of are eliminated.

(Elimination of unit rules)

If rules and in , do the following:

- (i)

Create and add it to .

- (ii)

Copy to .

- (iii)

Do not copy to .

- (iv)

Repeat (i) and (ii) until all unit rules of the form are eliminated.

(Conversion of remaining rules)

For every remaining rule in , where each for .

Create in the following sequence of rules and add the corresponding created variables to :

where if and if , add .

Example 2.38. Let be the consisting of the following rules:

Convert to in .

Step 1. (Applying .)

Step 2. (Removing using )

Step 3 (Removing using )

Step 4 (Removing because of redundancy)

Step 5 (Removing using )

Step 6 (Removing using )

Step 7 (Removing using )

Step 8 (Conversion of remaining rules into )

Since and ,

and , and

and ,

the rules in now become

Example 2.39. Convert to where and and show that there is more than one way of deriving the string using rules in .

Conversion of rules.

Derivation of a2b2

There is more than one way of deriving the string . Below are a few examples.

- (i)

.

- (ii)

.

- (iii)

.

2.3. Pushdown Automata ()

Pushdown automata is another kind of nondeterministic computation model similar to nondeterministic finite automata except that they have an extra component called stack. The purpose of the stack is to provide additional memory beyond what is available in finite automata.

Pushdown automata are equivalent in power to context-free grammars which will be proved later. In addition to reading symbols from the input alphabet , a also reads and writes symbols on the stack. Writing and reading on the stack must be done at the top. Either symbol from input or stack can be thereby allowing the machine to move without actually reading or writing. Upon reading a symbol from the input alphabet, the decides to make one of the following moves on the stack before entering the next state:

(i) Replace

Replace the symbol at the top of the stack with another symbol. This move is referred to as the “Replace” move.

(ii) Push

Add a symbol to the top of the stack. This move is referred to as the “Push” move.

(iii) Pop

Erase or remove a symbol from the top of the stack. This move is referred to as the “Pop” move.

(iv) Untouched

Do nothing to change the stack. This move is referred to as “Untouched” move.

A is formally defined as follows.

Definition 2.40. A is a 7-tuple, where are finite sets such that

(a) is the set of states

(b) is the input alphabet

(c) is the stack alphabet

(d) is the transition function

(e) is the start state

(f) is the initial stack symbol signaling an empty stack

(g) is the set of accept states.

computes as follows.

Let where for .

accepts iff and such that the following conditions are satisfied:

(i) and

(ii) ) for where and , where

(iii)

When and only conditions (i) and (iii) are valid which then becomes and and .

Therefore, we define a to accept whenever the start state is also an accept state and the stack is signaled to be empty.

If we write for , conditions (i), (ii) and (iii) can be written as follows:

.

When there is only one transition function under consideration, the showing of in the computation is usually omitted and the following shorthand is used instead:

.

For simplicity, we sometimes can use the notation to represent a computation of from to without showing the intermediate states.

We now can use the transition function to describe the four basic moves of the as mentioned above:

(i) Replace

signifies a replacement of by at the top of the stack upon reading symbol from input.

(ii) Push

signifies adding the symbol to the top of the stack upon reading symbol from input.

(iii) Pop

signifies removing the symbol from the top of the stack upon reading symbol from input.

(iv) Untouched

signifies nothing is done to change the stack upon reading symbol from input.

We further note that when , signifies a change of state from to with no input read and no change made to the stack.

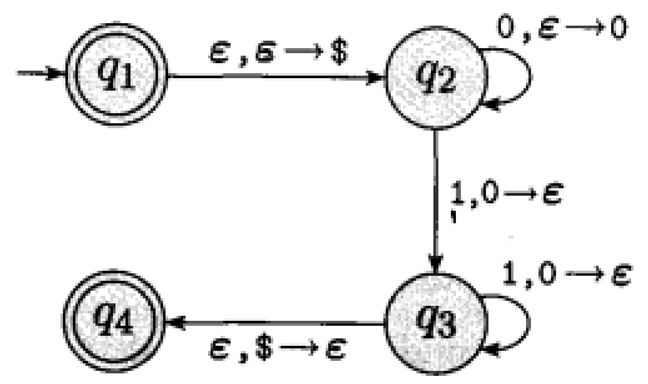

Example 2.41. Let be a where

, , , with the following state diagram:

recognizes the language .

If the stack is signaled to be empty at the beginning, accepts the empty string (), because is both a start and accept state. Furthermore, if the input string is not empty at the start state, the would not read anything from the string except to push onto the stack.

accepts the string with the following computation:

, .

Note that the above illustration is not a proof that recognizes the language

. To make such a proof, one must argue that every string of the form is accepted by and every string accepted by is of the form .

Note also that the steps and can be replaced by and to transition to another state without making a change to the stack.

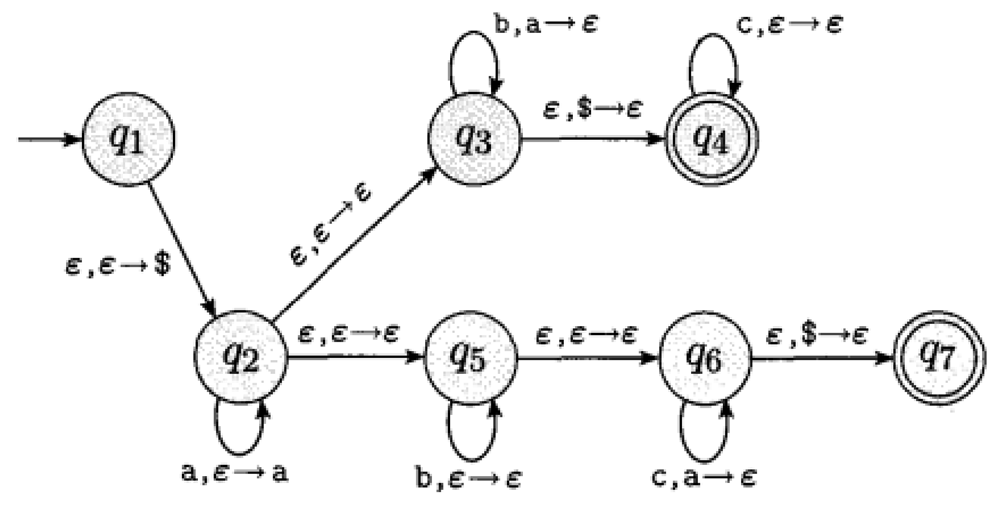

Example 2.42. Let be a where

, , , with the following state diagram:

recognizes the language .

accepts the empty string () with the following computation:

, .

accepts the string with the following computation:

, .

accepts the string with the following computation:

, .

Note also that the computations , , and can be replaced by and and to transition to another state without making a change to the stack.

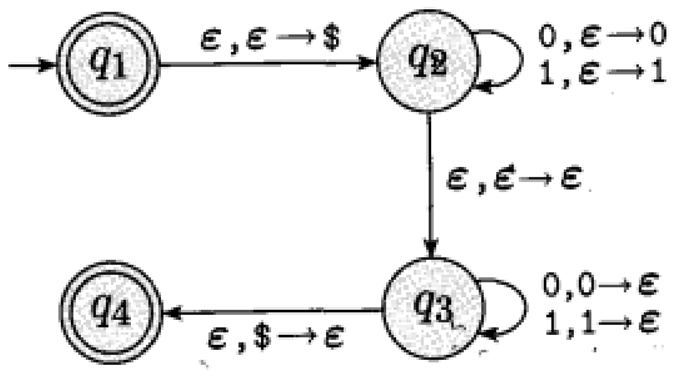

Example 2.43. Let be a where

, , , with the following state diagram:

recognizes the language .

If the stack is signaled to be empty at the beginning, accepts the empty string

(), because is both a start and accept state.

accepts the string with the following computation:

, .

Note also that the steps and can be replaced by and to transition to another state without making a change to the stack.

Instead of writing symbols one at a time to the stack, we can actually design s which can write a string of symbols to the stack in one step. These s are called extended s. It turns out that the two kinds of s are equivalent in power in that given one, we can construct the other such that the two recognize the same language. The equivalence of these two kinds of s will be proved later.

Definition 2.44. An extended is a 7-tuple, where are finite sets such that

(a) is the set of states

(b) is the input alphabet

(c) is the stack alphabet

(d) is the transition function

(e) is the start state

(f) is the initial stack symbol signaling an empty stack

(g) is the set of accept states.

computes as follows.

Let where for .

accepts iff and such that the following conditions are satisfied:

(1) and

(2) ) for where , and , where

(3)

When and only conditions (i) and (iii) are valid which then becomes and and .

Therefore, we define the extended to accept whenever the start state is also an accept state and the stack is signaled to be empty.

If we write for , conditions (i), (ii) and (iii) can be written as follows:

.

When there is only one transition function under consideration, the showing of in the computation is usually omitted and the following shorthand is used instead:

.

For simplicity, we sometimes can use the notation to represent a computation of from to without showing the intermediate states.

Theorem 2.45. For any extended , (), there is a ), such that and vice versa.

Proof. Construction of from .

Let be an extended .

Construct , where and are to be defined as follows.

For every , we define as follows.

If , .

If , at least one .

Let .

where and , , such that .

(Note that none of is .)

Create new states that satisfy the following conditions:

(by making )

(by making )

(by making )

(by making )

Note that the states thus created are not in and that

for any other combinations of and .

Note also that there can be more than one set of states and stack symbols to be created from each combination of because there can be more than one based on which the states and the stack symbols are created.

Let where , , and

is created from (ii) above.

Let .

For each , where and , define

(Note that .)

Let Set .

So, .

The construction is now complete and it remains to show that .

Suppose .

such that where .

, such that

.

if , then

and such that , and for .

Proof of Claim. From in the given computation, it follows that .

By assumption, .

By construction (ii), .

Either or .

If Since , and

.

Therefore, .

Since and , Claim is proved by taking and .

If Since , for some where , , and is created from construction (ii) above.

Therefore and .

now becomes .

Furthermore, from in the given computation, we have

.

Since for all () (), we must have .

Therefore, .

Therefore, and .

becomes .

By repeating the above argument, we can obtain the following computation:

.

where , , , and .

Let .

and .

Also, .

.

Since , .

Therefore, .

.

Assume for contradiction that .

.

.

Therefore .

This implies , which is a contradiction because and .

Therefore, .

Claim is also true under condition (b).

Combining (a) and (b), we conclude the proof of Claim.

Since , we can apply Claim on to obtain such that

; ; with also in and .

Since , we can again apply Claim on to get such that

; ; with also in & .

By repeating this process a number of times, we will obtain such that

, where .

Since is finite, this process of creation must stop at some point and at this point, .

Therefore, accepts .

By Claim, we have

where .

Therefore, .

Therefore, accepts .

Therefore, and hence .

Conversely, assume .

, for ; such that

and

.

Since , .

For all , .

[If ]

By construction (ii), .

Therefore, .

Also by construction (ii), .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

[If ]

, such that .

By construction (ii), such that

.

Therefore, .

Combining both cases of [] and [], we have

for all .

Therefore,

.

Therefore, accepts .

.

.

This completes the proof of for the construction of from .

Construction of from .

Let be a .

Construct where

such that

.

(Note that this is possible because .)

It remains to show that .

Let where for & .

Suppose .

, , for such that

.

For ,

since , .

since , .

Therefore, for .

Therefore,

.

accepts .

.

.

Conversely, suppose .

,

where , for .

For , .

Since , .

Therefore, for .

Therefore,

.

Therefore accepts and hence .

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of for the construction of from .

Combining (A) and (B), we conclude the proof of Theorem 2.45.

Now that we have proved the equivalence of and extended , we shall no longer distinguish between and or between and . From here on, we shall be using extended exclusively because it is a much more convenient tool for solving problems. We shall be using and for all s with the understanding that the s that we are dealing with can write a string to the stack in one single step.

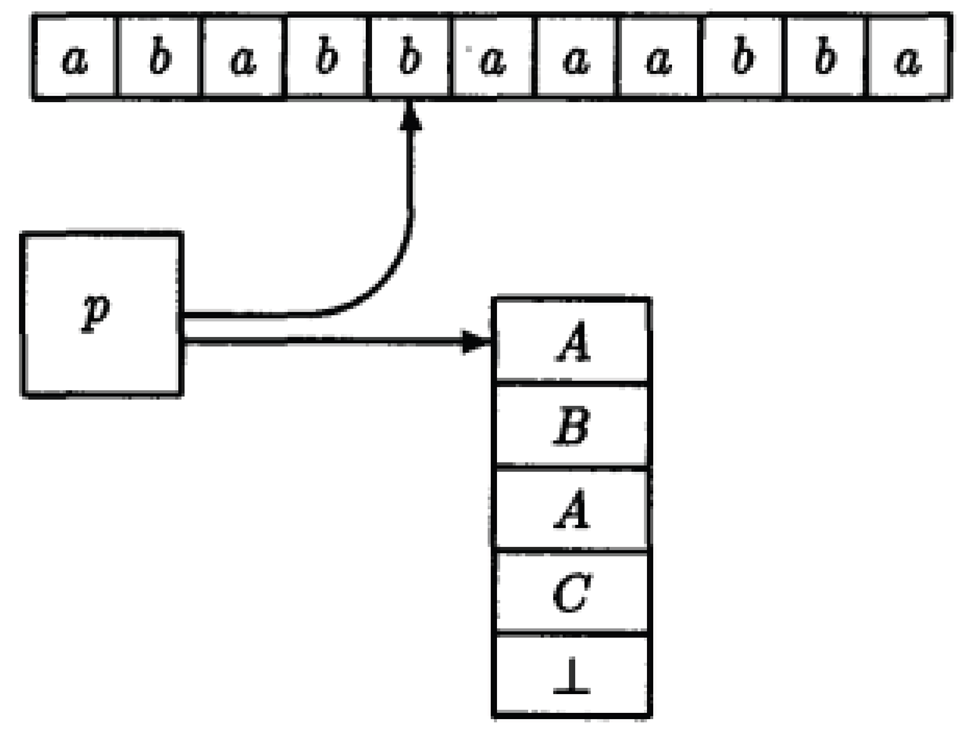

Definition 2.46 (Configurations of a). A configuration of a is an element of describing the current state, the portion of the input still unread and the current stack contents at some point of a computation. For example, the configuration

describes the situation as shown in the following diagram.

Note that the portion of the input to the left of the input head, namely , has been read and cannot affect the computation hereon.

The start configuration on input is defined as . That is, the always starts in its start state , with the input head pointing to the leftmost input symbol and the stack containing only the start stack symbol .

The next-configuration relation (denoted by or simply ) describes how the moves from one configuration to another in one step. It is formally defined as follows.

Definition 2.47. Let be a .

,

.

For any configurations , of ,

.

.

.

Proposition 2.48. Let be a .

For any where , accepts iff for some and .

Proof. By Definition 2.44, accepts iff , , for such that

.

By Definition 2.47, each one-step transitional movement is equivalent to one step of configuration movement.

For all , configurations and such that

The above transitional computation is equivalent to

, .

That is, , .

That is, , .

Since and where is the final stack content, we have

, .

Therefore, for some and .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.48.

Proposition 2.49. Let and be two s such that

, and

.

, and , the following statements hold:

(a)

(b) for any

Proof.

(a)

where , , , , , .

Since , .

Since , .

Since , and hence .

Since for all , we have

Conversely,

where , and

where , , , , , , , .

Since & , and .

Since & , and .

Therefore and hence .

Therefore,

.

(b)

This part can be proved by using the result of (a) along with an induction argument on the number of steps.

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.49.

Proposition 2.50. Let be a . It is true that integer ,

Proof. The proof is by induction on .

For , assume .

, and such that

, , and .

Since , and , , and ,

.

Therefore, the statement is true for .

For induction hypothesis,

for any integer .

For , assume .

, such that

and .

By induction hypothesis, we have

.

Since the statement is true for , we also have

.

Combining the two computations, we have

.

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.50.

The s that we have dealt with thus far accept an input by entering an accept state upon reading the entire input. We call this kind of a that accepts by final state. There is another kind of that accepts an input by popping the last symbol off the stack (without pushing any other symbol back on) upon reading the entire input. We call this kind of a that accepts by empty stack. It turns out that the two kinds of s are equivalent in that given one, we can construct the other such that the two recognize the same language. Before we prove the equivalence of these two kinds of s, we need a formal definition for s that accept by empty stack.

Definition 2.51. A that accepts by empty stack is a 6-tuple, where are defined similarly as in a that accepts by final state.

computes as follows:

Let where for & .

accepts iff for any .

(Note that the set of accept states, namely , is not needed in the definition of acceptance by empty state.)

Lemma 2.52. For any , , that accepts by empty stack, there is a , , that accepts by final state such that .

Proof. Let where is the initial stack symbol of .

Construct where and are newly created states (not in ) with serving as the start state of and serving as the set of accept states of .

is a newly created stack symbol (not in ) serving as the initial stack symbol of .

The transition function of is defined as follows.

T1: T2: T3: for any where

.

T4: for any other .

The construction is now complete. It remains to show .

Suppose .

for some & .

By T1, .

Therefore, .

By Proposition 2.49, we have

.

By Proposition 2.50, we have

.

That is, .

Also by T2, .

Therefore, .

Combining, we have

.

Therefore, .

Therefore, accepts .

Therefore, .

Conversely, assume .

for some .

Since there exists no transition in one step to go from to , there must exist configurations , , , where , , for , such that

.

Note that because each has both incoming and outgoing arrows whereas has only outgoing arrows and because has only incoming arrows.

Therefore, for , .

Claim 1. .

by T1.

Therefore, .

Since , and by T4, for any other combination of , we must have

.

Claim 2. For , such that .

Claim 2 can be proved by induction on .

For ,

(By Claim 1)

Therefore, .

Take .

.

.

The statement is true for .

For induction hypothesis (, assume for , .

Consider configuration move of

which is equivalent to where

, , , , , , .

Since , .

This configuration move could not have come from T1 because .

By induction hypothesis, & .

We examine two situations: (i) and (ii) .

(i) If

or .

If , .

This transition must have come from T2 where

, , .

Therefore, , which contradicts .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

By T3, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

.

Since , .

Therefore, .

The statement is true for .

(ii) If Since , is not a symbol in .

Since , the leftmost symbol of cannot be .

Therefore, the configuration move of could not have come from T2.

Therefore, it must have come from T3 where .

Therefore, by Proposition 2.49.

Therefore, where

, , , , , , .

Note that because .

By induction hypothesis, & .

Therefore, .

, which is a contradiction because .

Therefore, .

The rightmost symbol of must be .

such that .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Since by induction hypothesis, .

where .

Since & , .

The statement is also true for .

Therefore, the statement is true for whether or not .

This completes the proof of Claim 2.

Claim 3.

.

We know from above that .

The only way to transition from a state in to is via T2 where

.

Equivalently, .

Therefore, where & .

Therefore, .

Therefore, & .

By Claim 2, where .

Therefore, .

If , its rightmost symbol must be .

Let for some .

Therefore, .

Therefore, , which is a contradiction because by Claim 2, but is not in .

Therefore, .

.

.

and Claim 3 is proved.

Claim 4.

for .

From above, we have .

By Claim 2, where

, , , , , .

Equivalently, where & , , , .

Since , the above computation could not have come from T1.

Since , the above computation could not have come from T2.

Therefore, it must have come from T3 where .

Therefore, & and .

Since , the rightmost symbol of must be .

Therefore, for some .

Therefore, and .

Therefore, and .

Since by Claim 2, .

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Claim 4.

By Claim 4, we now have

.

By Claim 1, .

Therefore, , , .

By Claim 2, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

By Claim 3, .

& .

By Claim 2, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

.

Therefore,

.

.

accepts .

.

.

This completes the proof of Lemma 2.52.

Lemma 2.53. For any , , that accepts by final state, there is a , , that accepts by empty stack such that .

Proof. Let where is the initial stack symbol of .

Construct where

; ;

and are newly created states (not in ) with serving as the start state of and serving as the state in which begins the process of emptying the stack (without further consuming input);

is a newly created stack symbol (not in ) serving as the initial stack symbol of .

The transition function of is defined as follows.

T1: T2: where , .

T3: , .

T4: , .

T5: For any other , .

The construction is now complete. It remains to show .

Suppose .

for some & , .

By T1, .

Therefore, .

By Proposition 2.49, we have

. ()

By Proposition 2.50, we have

.

That is, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

By T3, .

By repeated application of T4, .

Combined, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, accepts .

Therefore, .

Conversely, assume .

There exist configurations , , , where

, , for , such that

.

Note that because doesn’t have incoming arrows.

If , .

By T1, and this is the only configuration move out of because .

Therefore, , which is a contradiction because .

Therefore, .

In addition, we have .

To move from to the final configuration , must pop at some point which can only be done by T4 because T1 does not pop and T2 and T3 cannot move on .

Therefore, we must have a somewhere between and .

However, we can only transition into via a state (T3).

Therefore, there must be a somewhere between and .

Max.

Claim 1. For , and hence has as its rightmost symbol.

To prove Claim 1, we assume for contradiction such that & .

By T4, .

This contradicts .

Therefore, for .

As mentioned above, .

Therefore, .

Since the only way to pop is by using T4 that requires the existence of and we cannot have any between and , we must conclude that remains sitting at the bottom of the stack as the machine moves from to Therefore, has as its rightmost symbol for .

Claim 2. For configuration , .

To prove Claim 2, we assume for contradiction .

At this configuration, there are two possible ways for the machine to move: (i) is to continue to simulate using T2 and (ii) is to enter using T3.

For (i), the machine will continue to read the input but will never enter an accept state again because it has passed which is the highest accept state in this computation. By the time the machine completes reading the entire input it will come to a stop and has never had a chance to enter the state . Thus, remains sitting in the stack when everything comes to stop. This is contradictory to the assumption that the computation ends at .

For (ii), the machine enters using T3 transition:

.

, , .

Once the machine has entered , it will follow T4, which is , to continue to pop symbols from the stack while remaining in and not reading any input.

Therefore, &

(Last configuration is ).

Therefore, both (i) and (ii) contradict the original assumption that .

Therefore, .

Claim 3. For , such that .

The proof of Claim 3 is by induction on .

We show at the beginning that Therefore, .

Since , .

If we take , .

The statement is true for .

For induction hypothesis, for , .

We show at the beginning that & by Claim 1.

Therefore, .

Consider configuration move of

.

This move could not have come from T3 or T4 because & .

The move must have come from T2 where .

By Proposition 2.49, we have

.

Therefore, where

, , , , , , .

Note that .

By induction hypothesis, & .

Therefore, .

Contradiction.

Therefore, .

The rightmost symbol of must be (because )

such that .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Since by induction hypothesis, .

where .

Since & , .

The statement is also true for .

This completes the proof of Claim 3.

Claim 4.

for .

By assumption, .

By Claim 3, By Claim 1, & for .

Also, we point out at the beginning that for .

Therefore, this computation must have come from T2 where .

By Proposition 2.49, .

Equivalently, where

, & , , .

Note that .

Contradiction.

Therefore, .

The rightmost symbol of must be (because ).

Let where .

Therefore, & .

Therefore, & .

Since by Claim 3, .

& .

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Claim 4.

By Claim 4, we now have,

.

as shown at the beginning.

Therefore, .

By Claim 3, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

By definition, .

By Claim 2, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, where .

Therefore, accepts .

.

.

This completes the proof of Lemma 2.53.

Combining Lemma 2.52 and Lemma 2.53, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 2.54. For any , , that accepts by empty stack, there is a , , that accepts by final state such that .

Conversely, For any , , that accepts by final state, there is a , , that accepts by empty stack such that .

2.4. Equivalence of

andIn this section, we shall prove that context-free grammars and pushdown automata are equivalent in power in that any language that is context-free is recognized by a pushdown automata and vice versa.

Definition 2.54. Let be a .

Let , .

is called the leftmost variable in iff and such that .

is called the head of (written as ), is called the body of (written as ) and is called the tail of (written as ).

It is clear from this definition that and if , then and .

Definition 2.55. Let be a .

, is a prefix of (written as ) iff such that .

Proposition 2.56. is a reflexive and transitive relation from to .

Proof.

, and .

Therefore, and is a reflexive.

, if and ,

such that and .

Therefore, .

Since , .

Therefore, is transitive.

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.56.

Proposition 2.57. Let be a .

Let , for all .

Let be the leftmost variable in and be the rule such that for all .

Let .

The following statements are true:

(a)

(b) , & hence

(c) &

(d) If such that , then .

Proof. Since , & , we have .

Therefore, where is the leftmost variable in .

Since & , is also the leftmost variable in .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

This follows (a) to be true because is transitive.

is established in the proof of (a).

It is also established in the proof of (a) that .

.

( is the leftmost variable in )

From (b), .

Therefore, such that .

Therefore, .

By (c), .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Lemma 2.58. For any , a such that .

Proof. Let be a .

Construct where is the transition function defined as follows.

T1: is a rule in .

T2: .

T3: For all other , .

Note that the start variable of is the start stack symbol of .

It remains to show .

To prove , suppose .

such that

.

, by Proposition 2.57(b).

Therefore, such that .

Claim.

, where .

This Claim can be proved by induction .

For , because .

. .

.

Therefore, , & .

Therefore, , & .

.

The statement is true for .

For induction hypothesis, we have

where for .

Let be the leftmost variable in .

Since , where .

=

(by T1)

= By Proposition 2.57, .

such that .

Therefore,

(by repeated applications of T2 times)

= (by Proposition 2.57(c))

Therefore, .

Since ,

.

By Proposition 2.57(c), .

By induction hypothesis, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, the statement is true for.

To complete the proof of , set in Claim.

where .

Since , & .

() & ().

Therefore, .

.

Therefore, .

(Note that at this final configuration of , we could have used the transition, or , to loop on without stopping. However, this machine is nondeterministic, which means that we don’t have to take an option which is a bad one. On the other hand, if bad choices are made, we can loop ourselves to infinity.)

To prove , let .

.

Claim.

, if , then .

Proof of this Claim is by induction on the number of steps.

, such that .

For , .

Since , we must use T1 and that is, is a rule in .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, is a rule.

by Proposition 2.8(i).

Therefore, .

The statement is true for .

For induction hypothesis, assume the statement is true for all with .

That is, if , then for all .

For , assume .

Since , the first move must be based on T1.

Therefore, where

& for .

Since , the machine must pop all the off the stack by the time it finishes reading input and empties the stack.

Let be the portion of that the machine consumes while popping off the stack and returning its stack head to the position right before popping off for .

Let also be the last portion of that the machine consumes while popping off the stack and emptying the stack eventually.

Note that if is a terminal, . The will pop using T2 and then scan the same symbol from the input. The stack head will then point at .

By these assumptions, we have .

In addition, we have the following sequence of computations:

.

Since the stack head does not go below while the consumes , we have the following equivalent computations:

Since the sum of all the numbers of steps in all these computations is equal to , the number of steps in each of these computations is less than or equal to .

Therefore, we can use the induction hypothesis to derive the following:

Since , by Proposition 2.8(i).

Since , by Proposition 2.16(d).

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

The statement is true for .

To complete the proof of , put & in Claim.

.

.

This completes the proof of and hence the proof of Lemma 2.58.

Lemma 2.59. For any , a such that .

Proof.

Let be a that accepts by empty stack.

Construct where & are defined as follows.

Note that is finite because & are finite.

Let be the procedure for creating rules in defined as follows.

, if , .

That is, .

For every , , let

be a rule in .

Note that the total number of rules thus created based on each

is finite because , , & are finite.

Furthermore, the set is finite & the total number of such sets, is finite because the total number of is finite.

Therefore, the total number of rules thus created for any given , is finite.

Let the set of rules created by .

.

.

The construction of is complete and we now proceed to prove .

Claim 1. iff for some .

<Proof of Claim 1>

If

such that .

where .

By Proposition 2.8(i), is a rule.

This rule must be from .

Therefore, for some .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, for some .

If By construction, is a rule in .

By Proposition 2.8(i), .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Claim 1.

Claim 2. , , , iff .

<Proof of Claim 2>

“If”

Assume .

such that .

The proof of is by induction on .

For , Therefore, where & .

By , if , then a rule for some .

In this case, which means and hence .

Therefore, a rule .

Since & , the rule becomes .

By Proposition 2.8(i), .

Therefore, .

The statement is true for .

Assume the statement is true for all where .

That is, for all .

For , assume .

, , , , such that .

Therefore, .

Since , using the same argument as used in the proof of Lemma 2.58, we can deduce the following computations:

where

, ,

is the portion of that the machine consumes while popping off the stack and returning its stack head to the position right before popping off for and is the last portion of that the machine consumes while popping off the stack and emptying the stack eventually.

Note that the machine goes from state to state after completing the above actions & .

Since each computation is part of the computation , each one makes no more than moves.

By induction hypothesis, for .

As shown above, & since , by ,

a rule .

By Proposition 2.8(i), .

Since & for .

by Proposition 2.16(d).

Therefore, .

Since , .

Therefore, Therefore, the statement is true for .

This completes the proof of the “If” part of Claim 2.

“Only if”

Assume .

such that .

The proof of is by induction on .

For , .

By Proposition 2.8(i), is a rule in (It’s not in because ).

Since every rule in is of the form where

& .

In this particular case, is not a variable.

Therefore, or .

Therefore, & .

Since , .

We must have .

Therefore, where .

As shown above, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

The statement is true for .

For induction hypothesis, assume it is true that

for all where .

For , assume .

Therefore, where .

By Proposition 2.8(i), is a rule in .

This rule must be of the form where

, , , .

by Proposition 2.8(i).

Therefore, .

By Proposition 2.28(ii), such that in no more than steps for and .

By induction hypothesis, for .

By Proposition 2.50,

for .

for .

for .

for where .

Furthermore, as shown above, .

Therefore, .

Since , .

Connecting all the computations, we have

.

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Claim 2.

We now get back to the proof of .

for some (Claim 1)

(Claim 2)

accepts

Therefore, .

This completes the proof of Lemma 2.59.

Combining Lemma 2.58 and Lemma 2.59, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 2.60. For any , a such that .

Conversely, for any , a such that .

2.5. The Pumping Lemma for Context Free Languages

In this section, we shall develop a tool for showing that a language is not context free. This tool is called “The Pumping Lemma for context free languages.” This Pumping Lemma is analogous to the pumping lemma we study in Chapter 1 for regular languages. The difference this time is we are pumping two strings rather than one and the string that we are dealing with is broken down into five substrings in contrast to three substrings in the case of regular languages.

Theorem 2.61. Let be a in Chomsky Normal Form.

Let be the parse tree corresponding to this grammar in accordance with the meaning of Theorem 2.33 where is the root, is the yield and is the height of the parse tree. Then it is true that .

Proof. The proof of this theorem is by induction on .

For , is a 1-level tree with at the zero level and at the first level.

The only forms of rules in Chomsky Normal Form are:

where and

where

where Start Variable.

Since , we have either or .

Therefore, or .

.

.

Either case, we have statement being true for .

For induction hypothesis, assume the statement is true for all where .

Consider a parse tree, , that correspond to according to the meaning of Theorem 2.33.

Since , the height of is greater than or equal to . Hence the children of A which appear in the first level cannot be or .

They must be and with .

Using similar argument as we use in proving Theorem 2.33, we can show the following:

(i) The combination of all branches of (respectively ) form a subtree (respectively)

(ii) &

(iii) .

By (ii) and induction hypothesis, & .

This completes the induction proof of Theorem 2.61.

Proposition 2.62. Let be a parse tree for and be the largest subtree of where , . Then such that . Furthermore, the nodes on any path from to (respectively ) cannot be a node in .

Proof. By T13, every leaf of a subtree is also a leaf of the parent tree.

Therefore, .

Therefore, for some .

Let be a path from to where is a symbol in .

There exists a on this path such that and are at the same level.

If and are the same node, is a branch rooted at and by T11, it is a path inside .

This means that is a symbol in and this contradicts the assumption that is a symbol in .

Therefore, cannot be the same node as .

Since is to the left of every symbol in and is an ancestor of , by T12, is to the left of .

Let be a node on the path .

If , is above the level of and hence is not a node in .

If , is a descendant of and hence by T12, is to the left of all descendants of B at the same level.

Therefore, cannot be a node in .

With similar argument, we can also prove that if is a node on a path from to any in , cannot be a node in .

This completes the proof of Proposition 2.62.

Theorem 2.63. Let be a parse tree for and be the largest subtree of rooted at such that where .

If is replaced by another parse tree , to form a new tree , then .

Proof. By Proposition 2.62, we can write for some , because is a subtree of .

Let be a leaf in .

By T8, there is a unique path from to in .

Let’s call this path where is at the same level of .

By Proposition 2.62, is not affected by the removal of and in addition, is to the left of .

Therefore, remains a path in the new .

Therefore, is a leaf in .

is not in because consists of all the leaves created from the addition of .

If is in , the ancestor of at the level of , namely , must be to the right of which contradicts what we have shown above and that is is to the left of .

Therefore, cannot be in .

Therefore, is in .

Therefore, .

Conversely, if is a leaf in ,

by T8, there is a unique path from to in .

Let’s call this path where and are at the same level.

By Proposition 2.62, are not in and is to the left of .

These nodes must have come from .

In addition, they are not in either because if they were, they would have been eliminated by the replacement of .

Therefore, is not in .

If is in , would be to the right of , which contradicts what we have shown above and that is is to the left of .

Therefore, cannot be in .

Therefore, is in .

Therefore, .

Therefore, .

With similar argument, we can also prove that .

This completes the proof of Theorem 2.63.

Theorem 2.64A (The Pumping Lemma for

s). Let be a .

such that if and , then

for some with the following conditions satisfied:

(i) ,

(ii)

(iii)

Proof. By Theorem 2.37, there exists a , in Chomsky Normal Form such that . Let where the number of variables in .

If , .

By Theorem 2.33, there is a parse tree for with root and yield .

Let this parse tree be represented by where is the height of the tree.

By Theorem 2.61, .

If , .

.

.

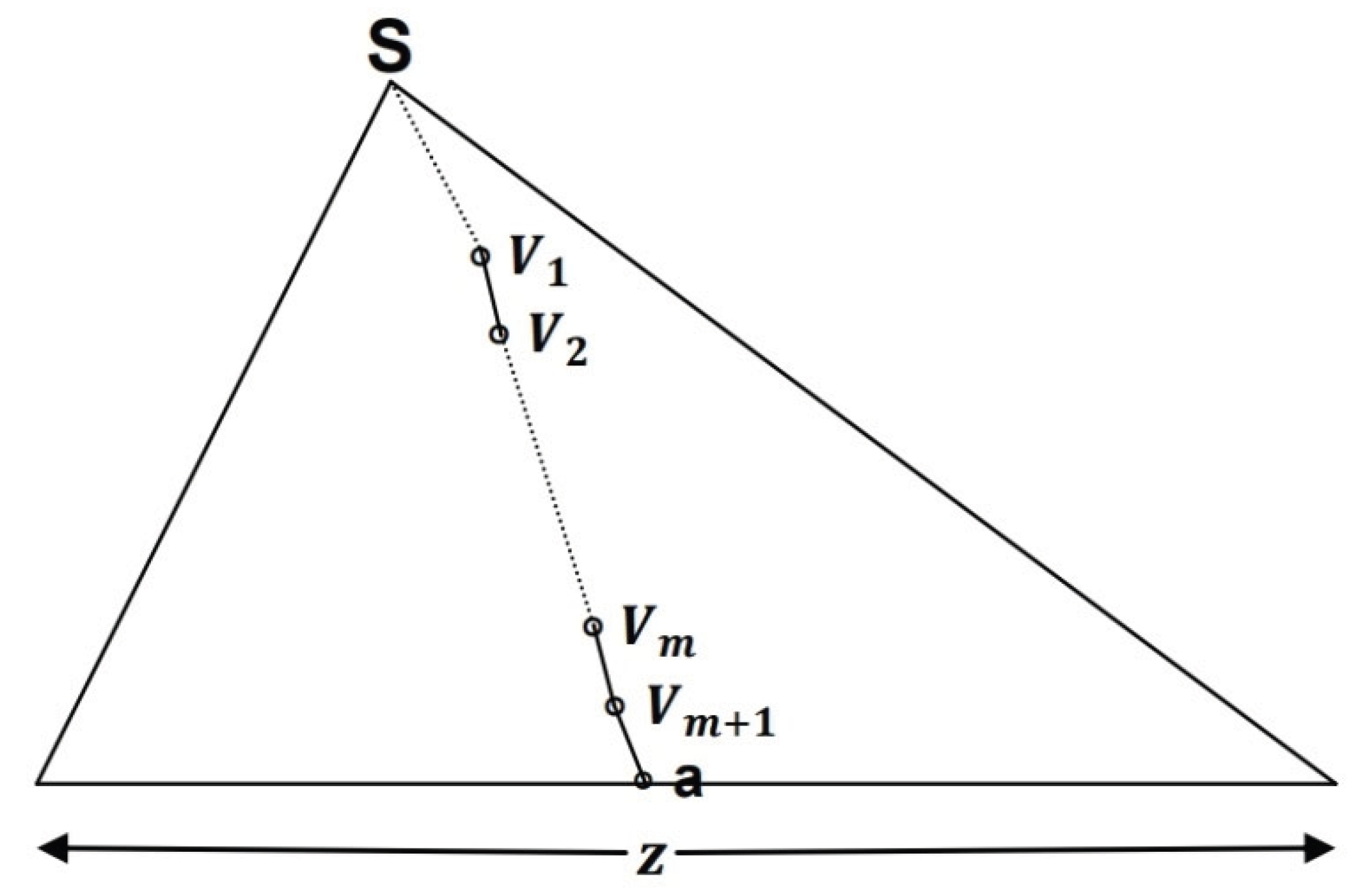

By T9, a path from to where is a leaf in such that the length of this path is equal to .

(Note that this is the longest path in the tree.)

Since , there are at least nodes on this path.

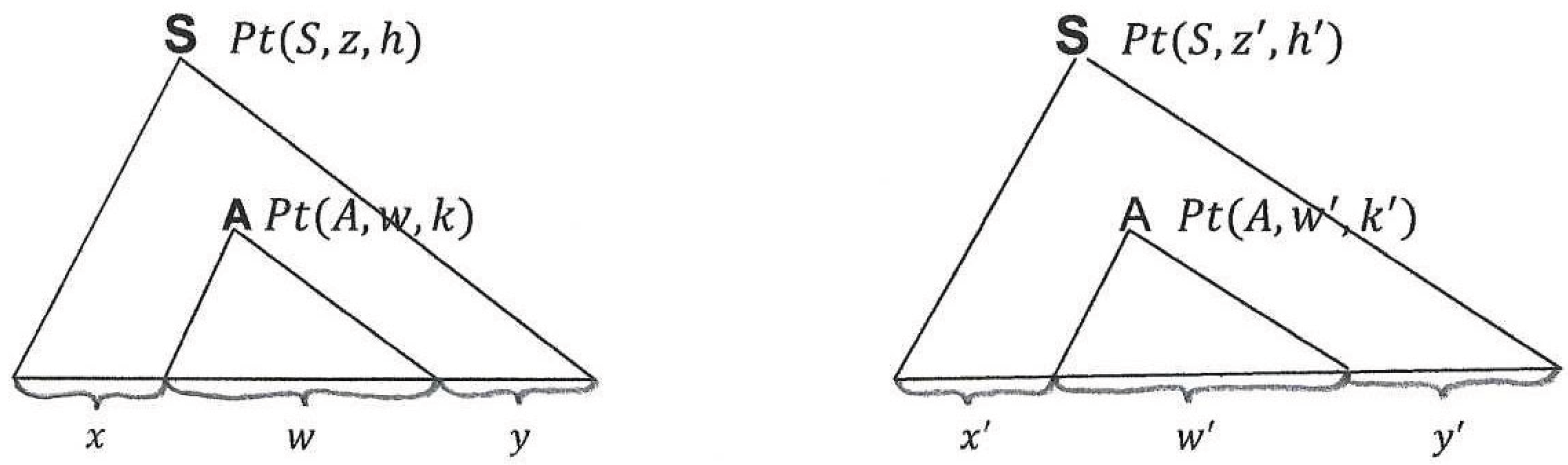

Let be the lowest portion of this path where

.

See Figure 2.14 below.

Note that this is the longest path from to a leaf.

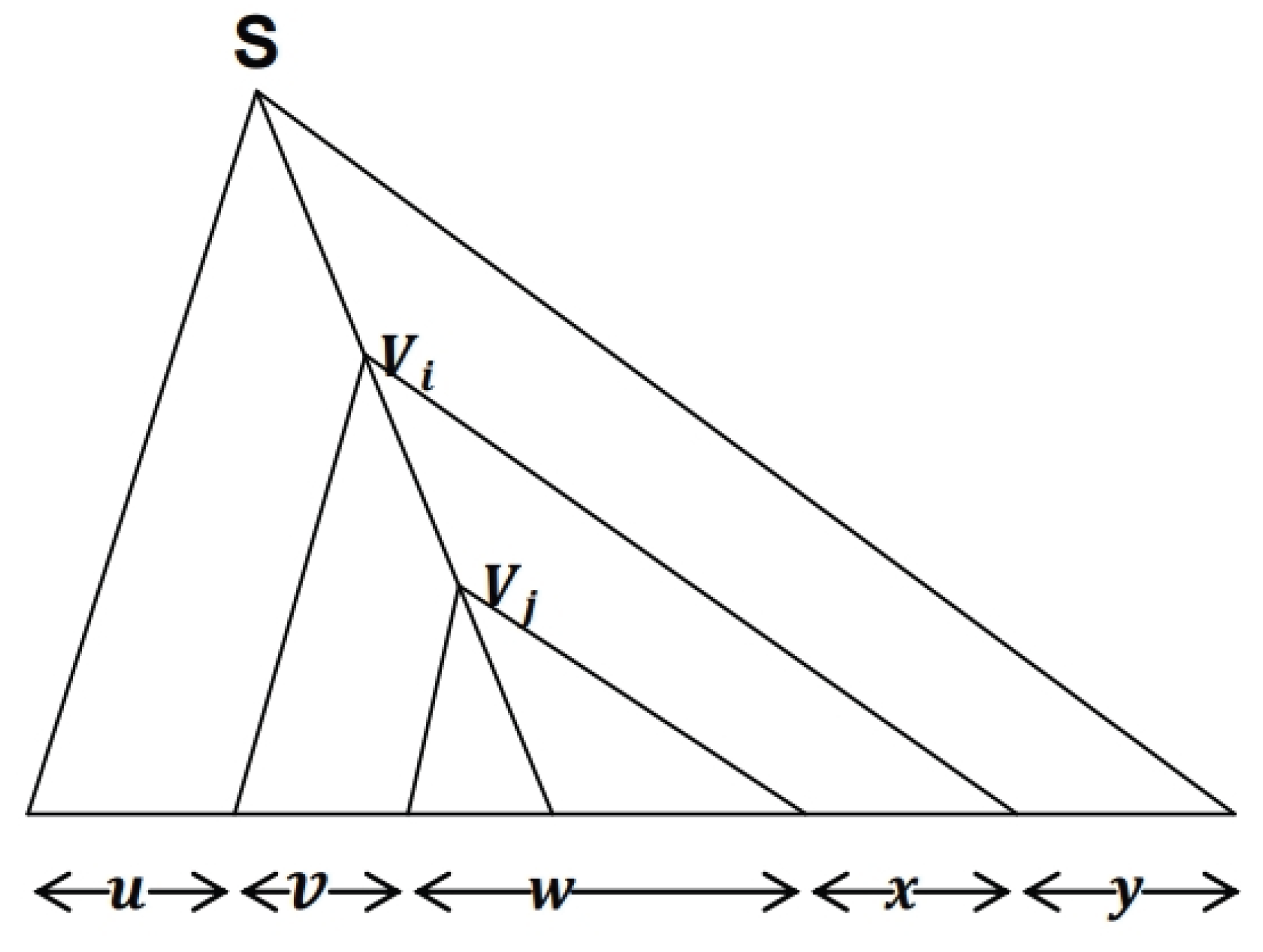

Since , by the pigeonhole principle, such that .

Let be the largest subtree rooted at and be the largest subtree rooted at .

See Figure 2.15 below.