Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

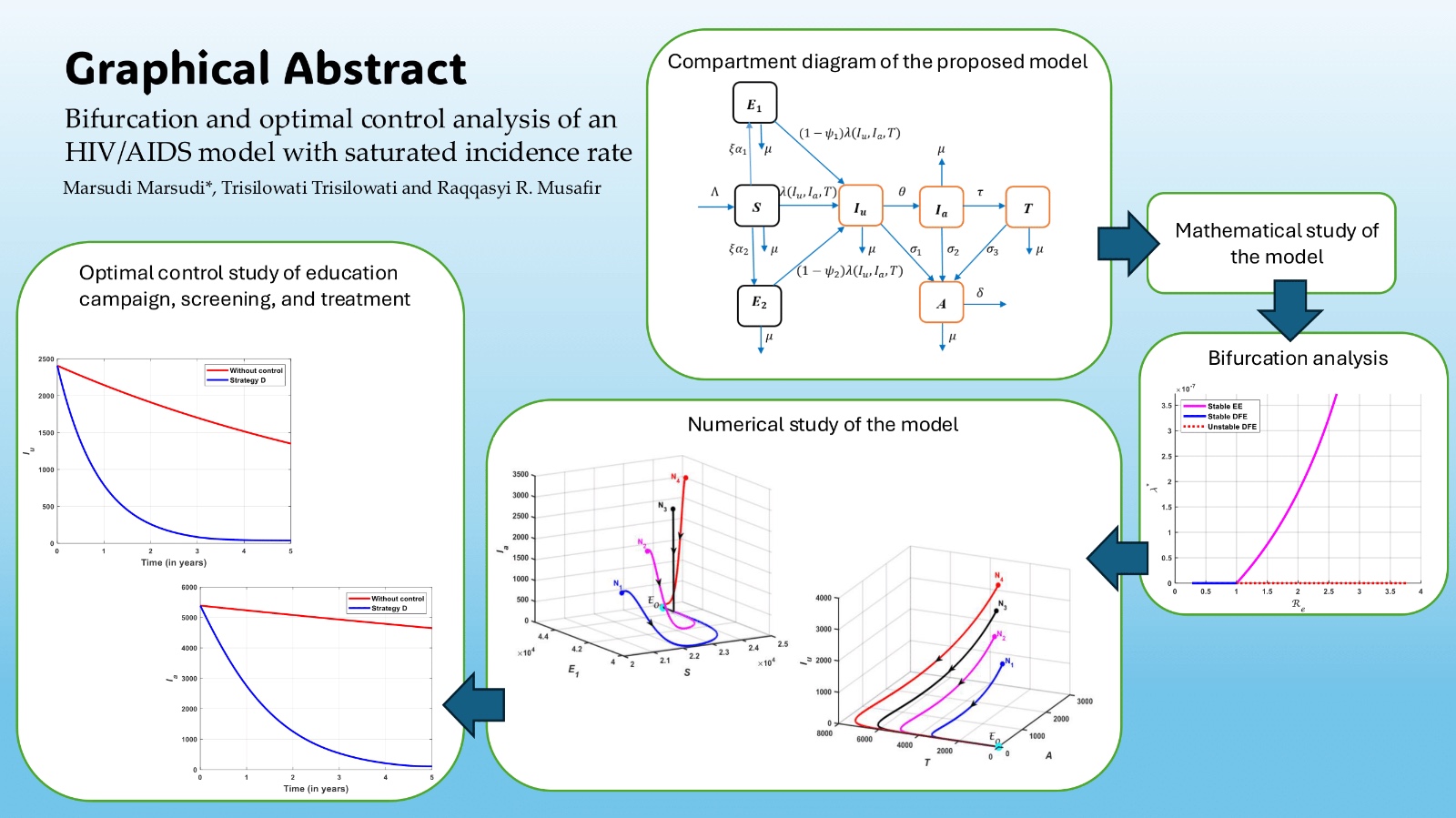

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 34D23; 92D23; 49J15; 37N35

1. Introduction

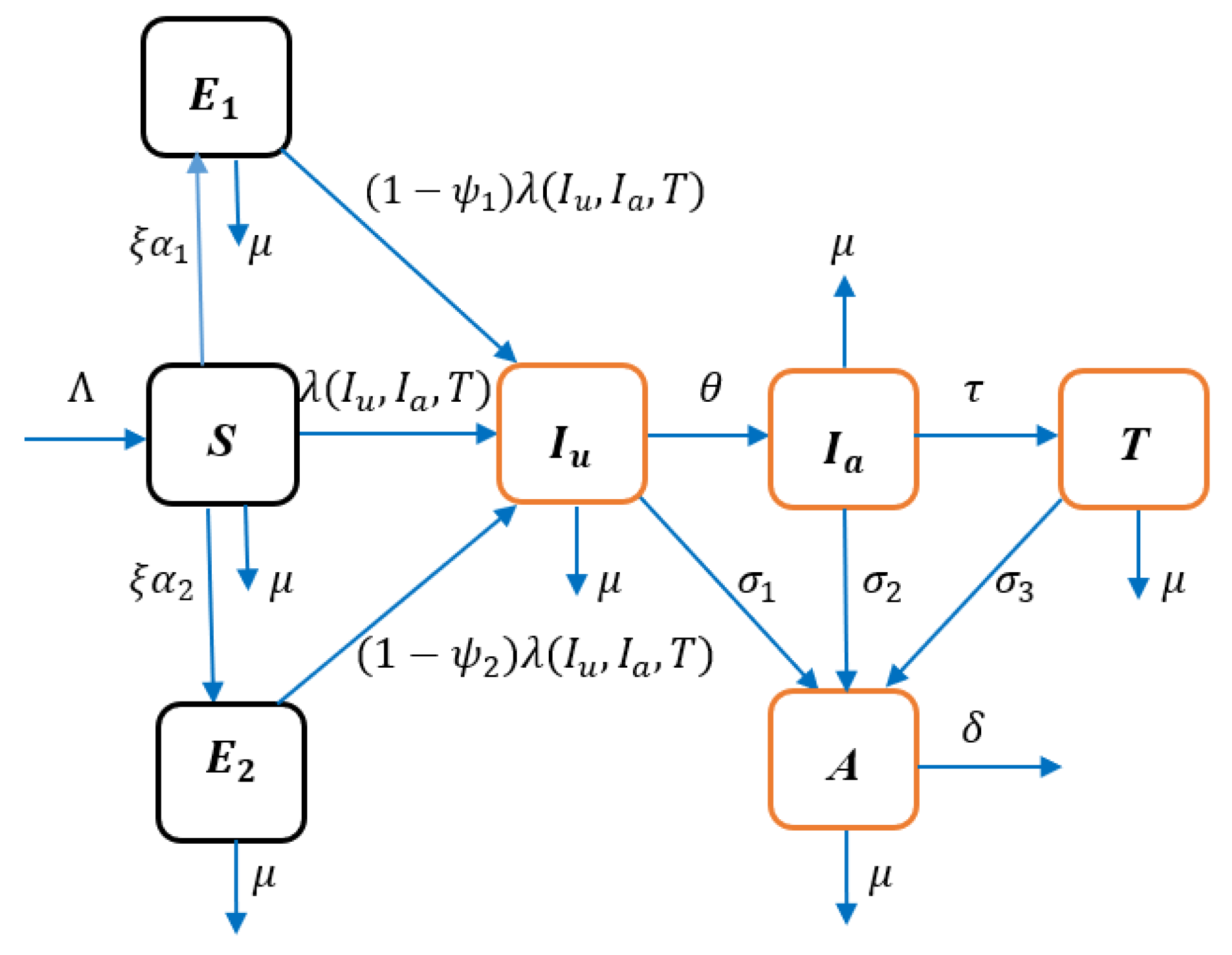

2. Formulation of the Model

3. Analysis of the Model

3.1. Positivity and Boundedness of Solutions

3.2. Existence of Equilibrium Points

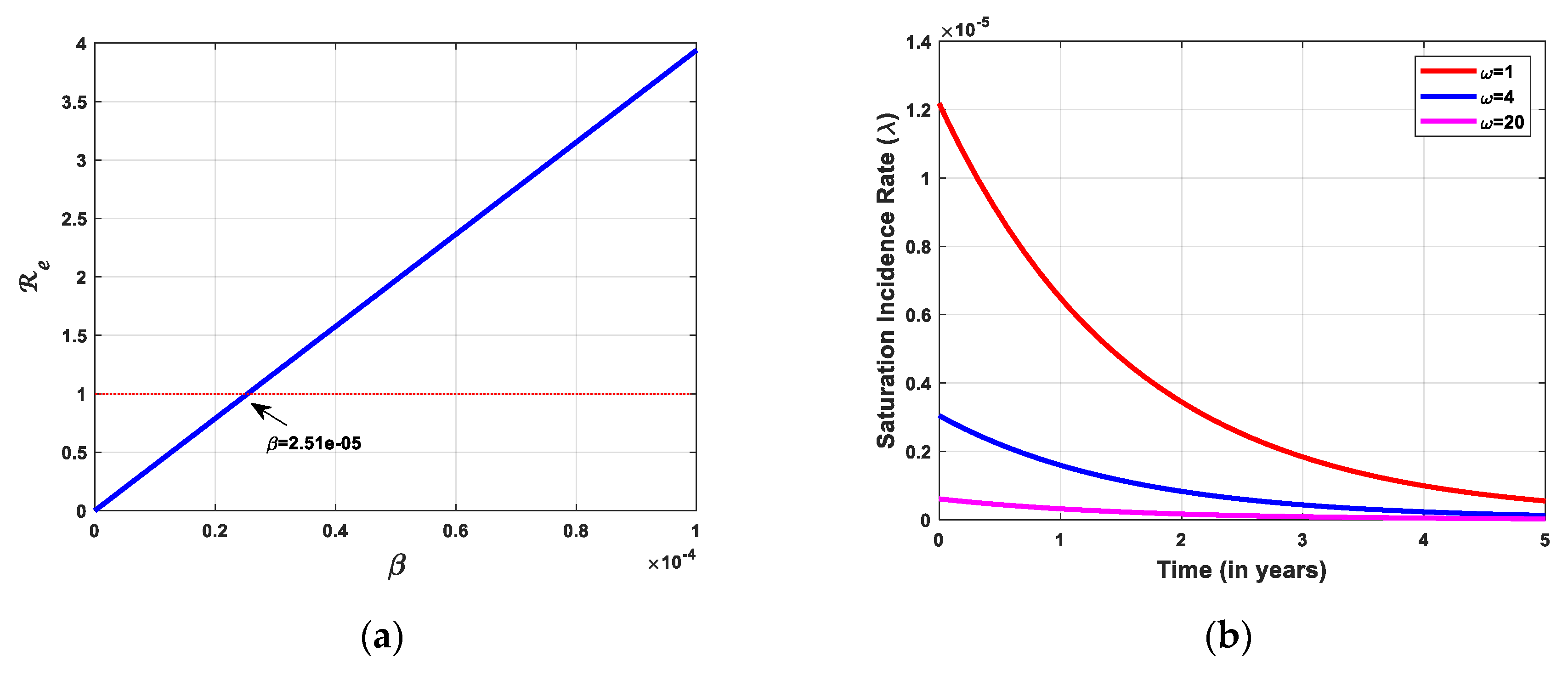

3.2.1. Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE) and Effective Reproduction Number

3.2.2. Existence of Endemic Equilibrium

3.3. Stability Analysis

3.3.1. Local Stability of Disease-Free Equilibrium

3.3.2. Global Stability of Disease-Free Equilibrium

- () For is globally asymptotically stable.

- () for and is a Metzler-matrix (the off-diagonal elements ofare nonnegative).

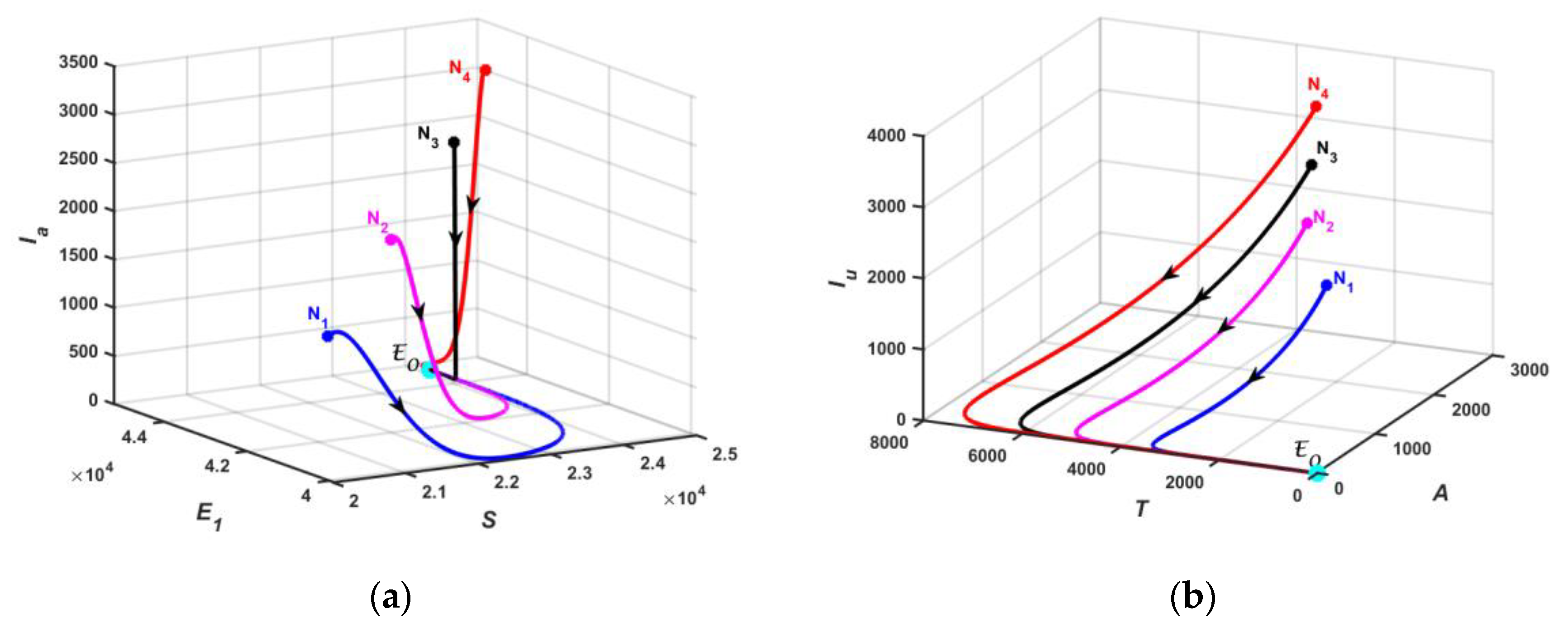

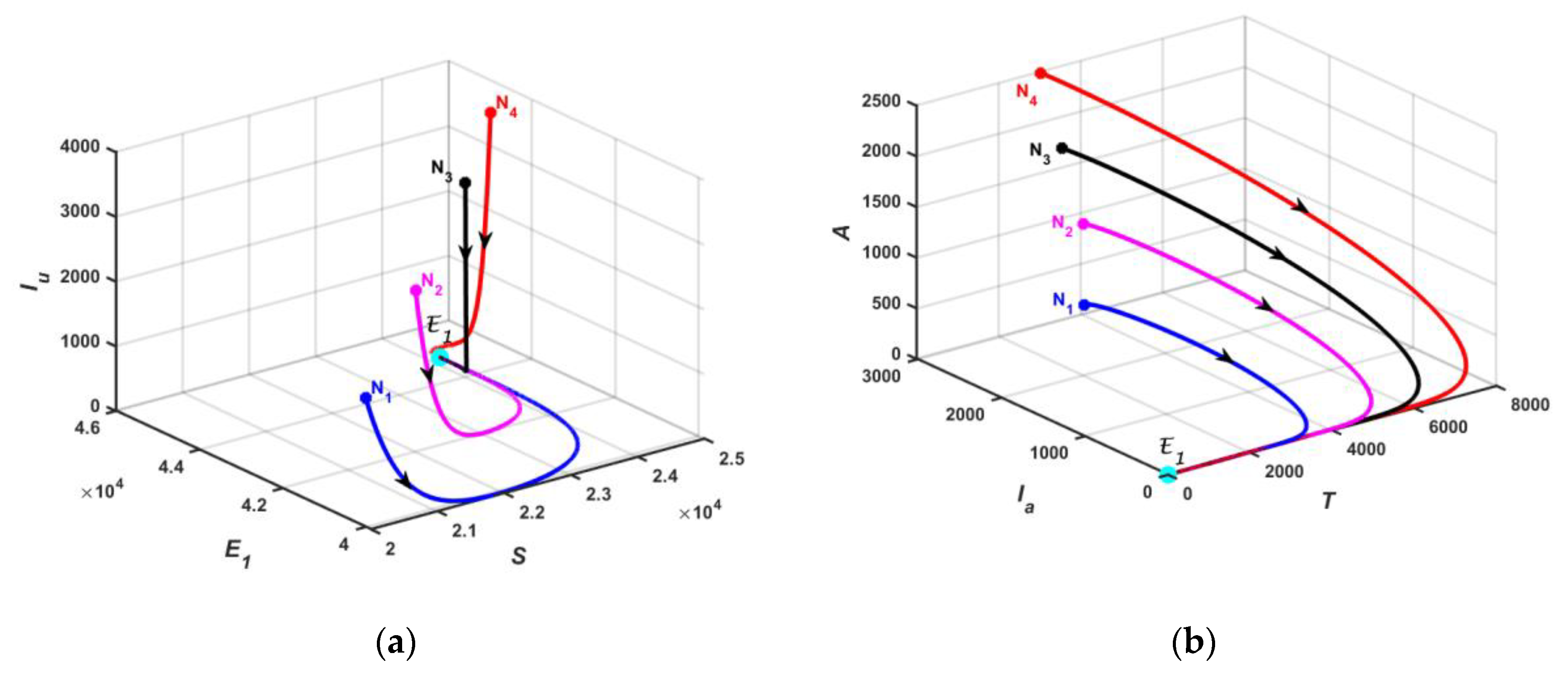

3.3.3. Global Stability of Endemic Equilibrium

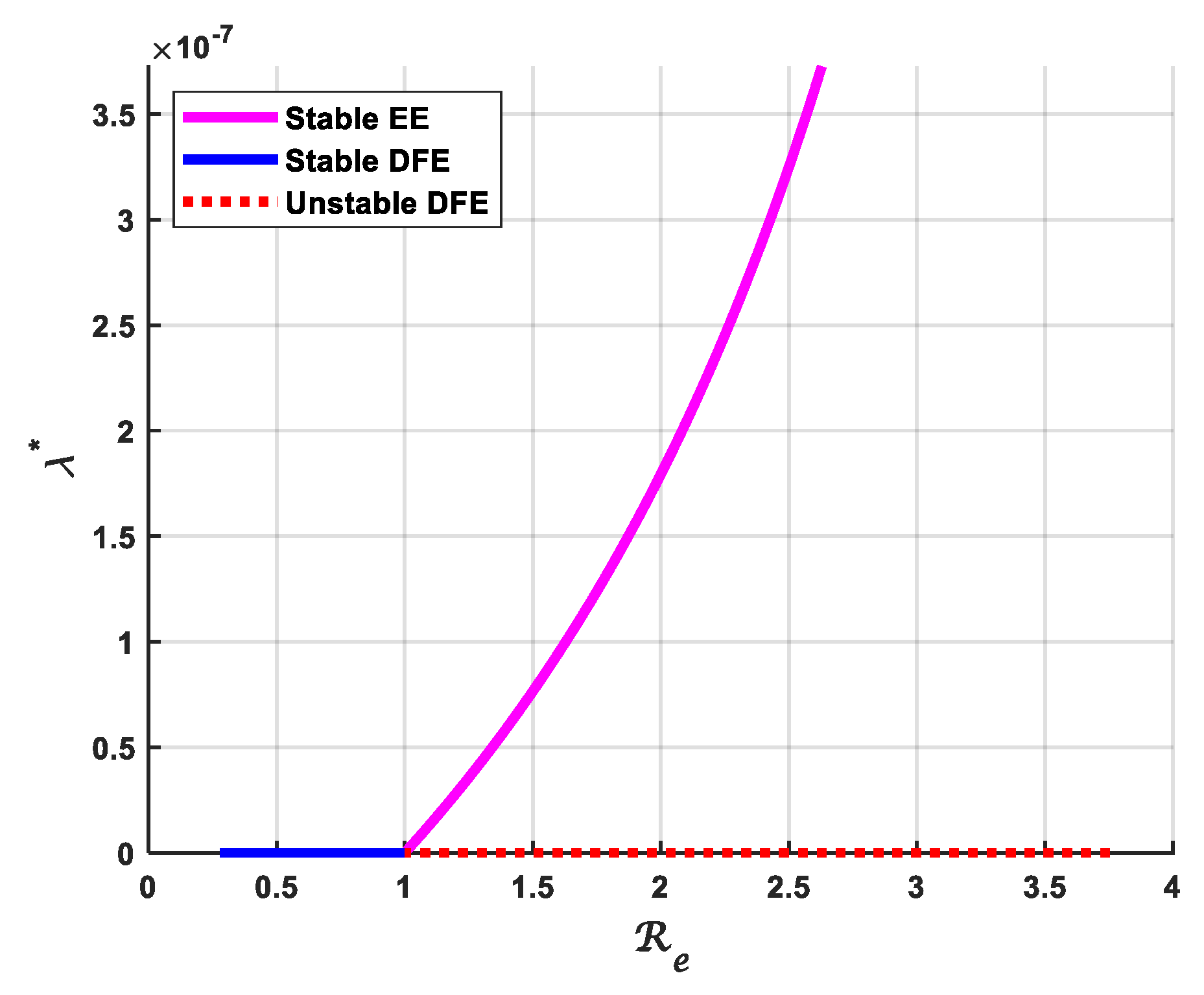

3.4. Bifurcation Analysis

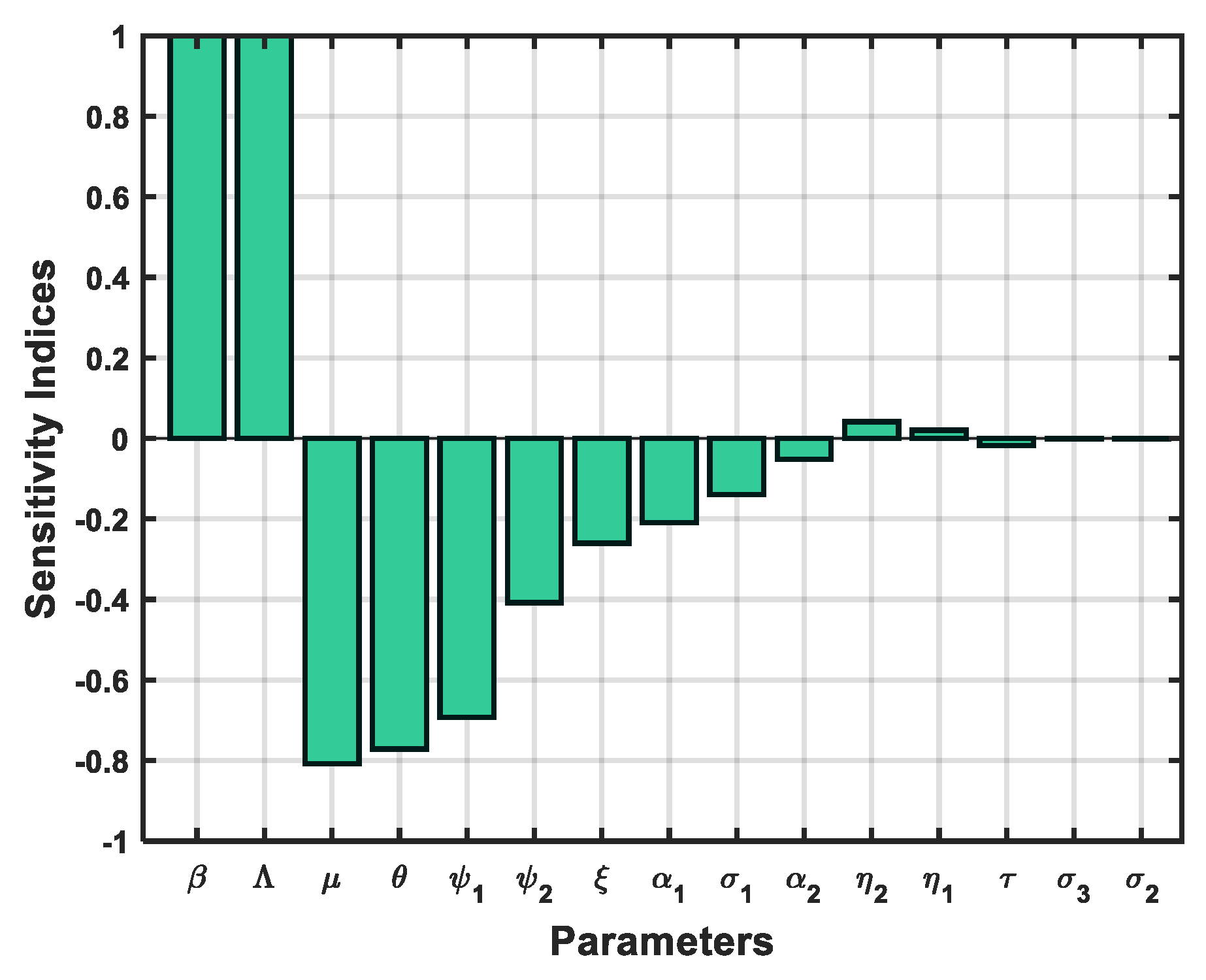

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Optimal Control Model

- The parameter represents the proportion of the susceptible subpopulation that receives the educational campaign and adopts AB (Abstinence, Be faithful) and C (use Condoms) behaviours.

- The parameter represents the proportion of the unaware infective subpopulation that receives screening per unit of time.

- The parameter represents the proportion of the aware infective subpopulation that receives antiretroviral treatment per unit time.

4.1. Optimal Control Problem

4.2. Existence of an Optimal Controls

- (i)

- The optimal control set, and state variables set are nonempty.

- (ii)

- The control set U is closed and convex.

- (iii)

- The right-hand side of the state system (35) is continuous and bounded by a linear function in both the state and control variables.

- (iv)

- The integrand of the objective functional J in Equation (36) is convex concerning the control set U.

- (v)

- There exist constants and such that the integrand of the objective functional J in (36) is bound below by

4.3. Characterization of the Optimal Control

5. Numerical Simulations and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

5.1. Numerical Simulation of Model

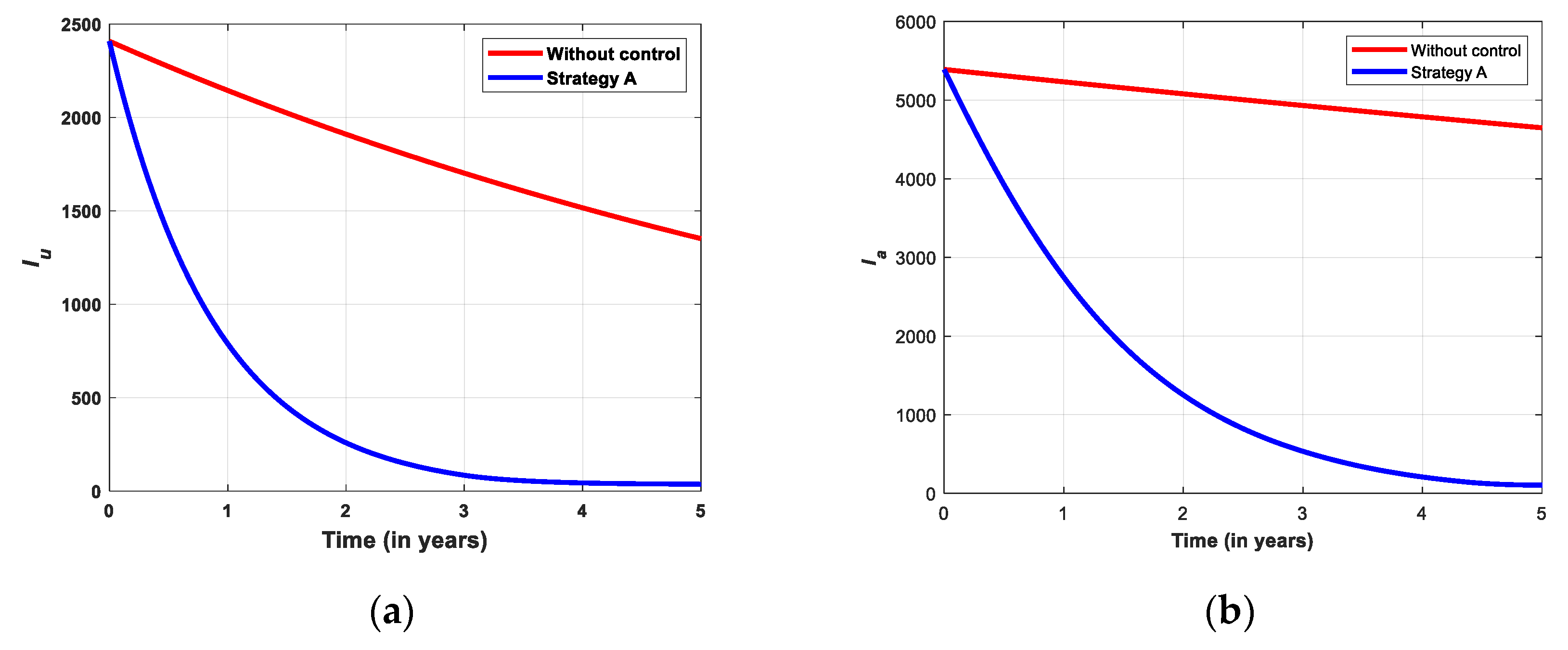

5.2. Optimal Control Simulation

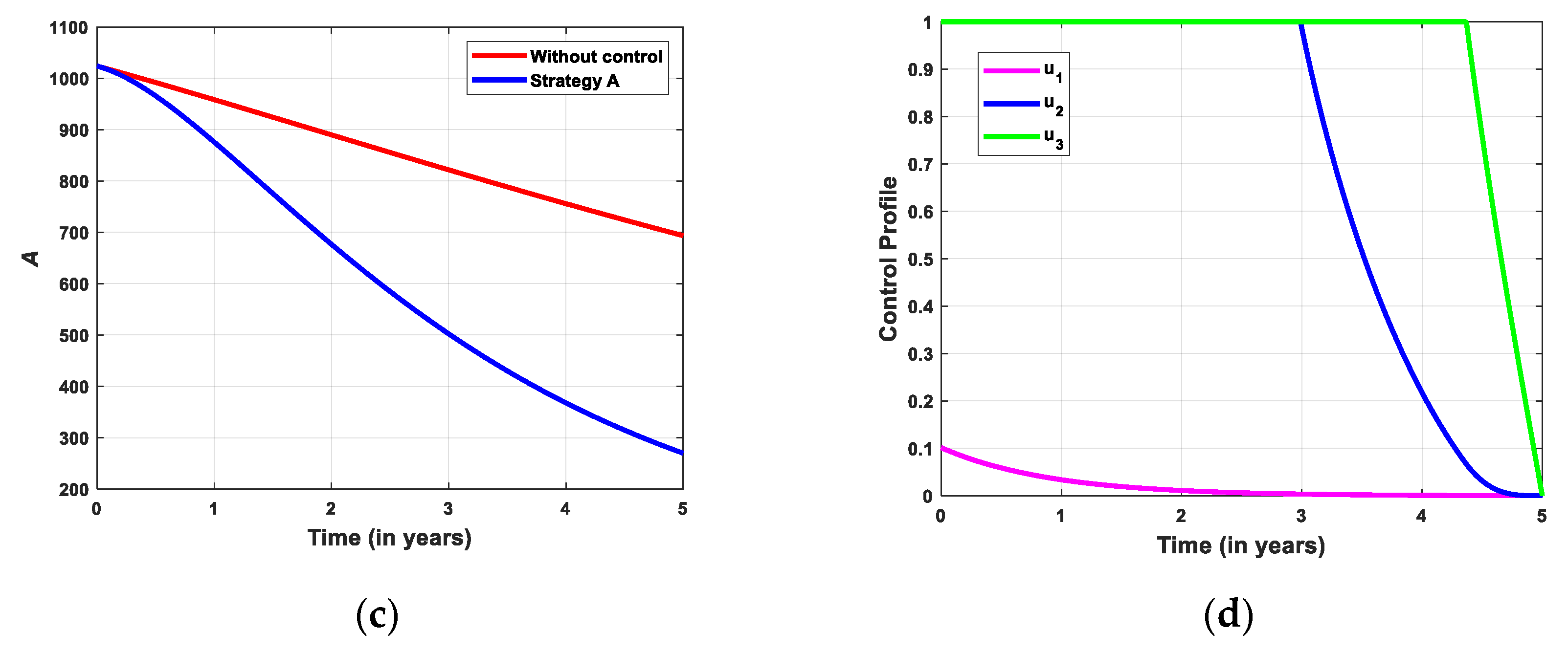

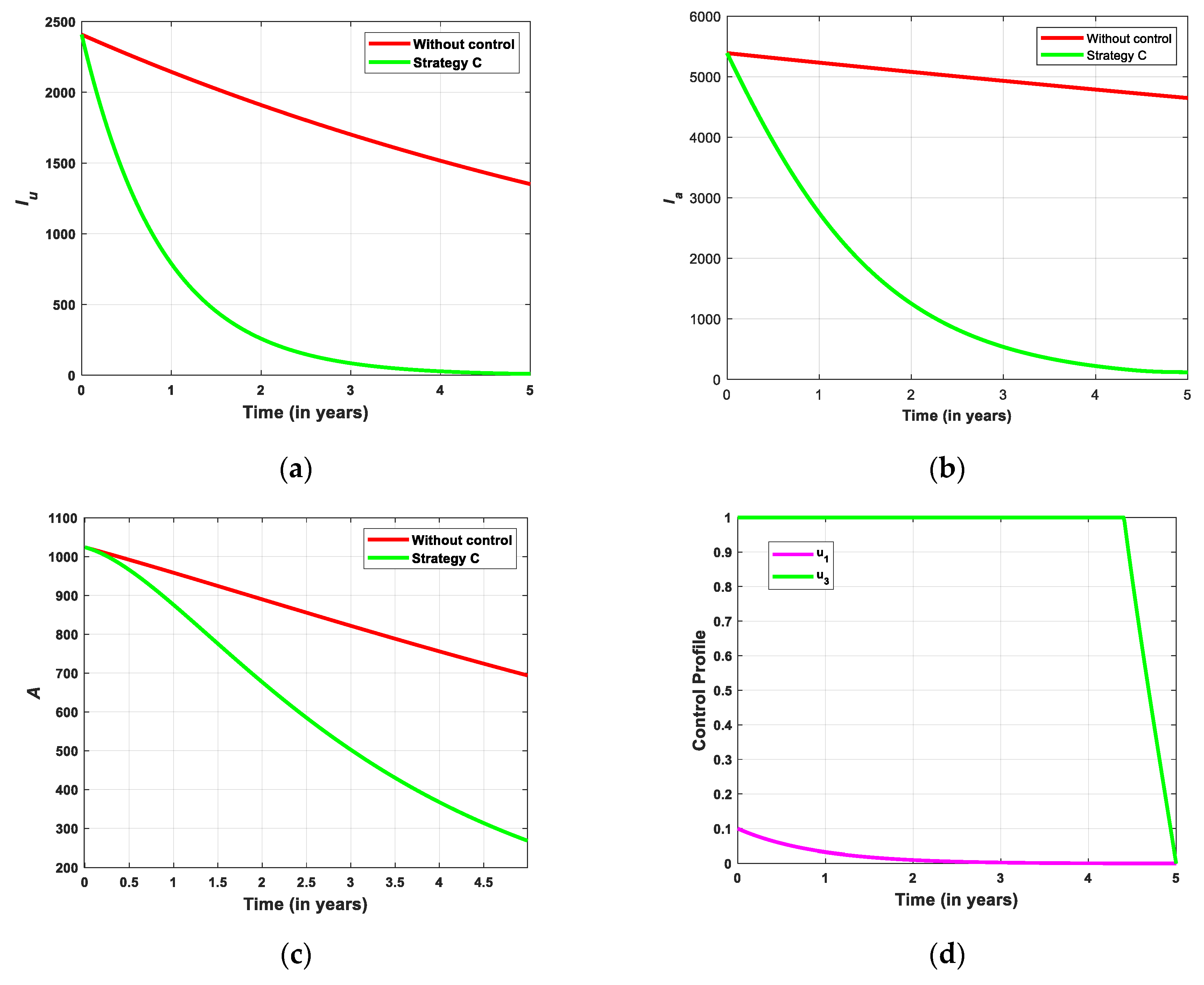

- Strategy A: Educational campaign combined with screening

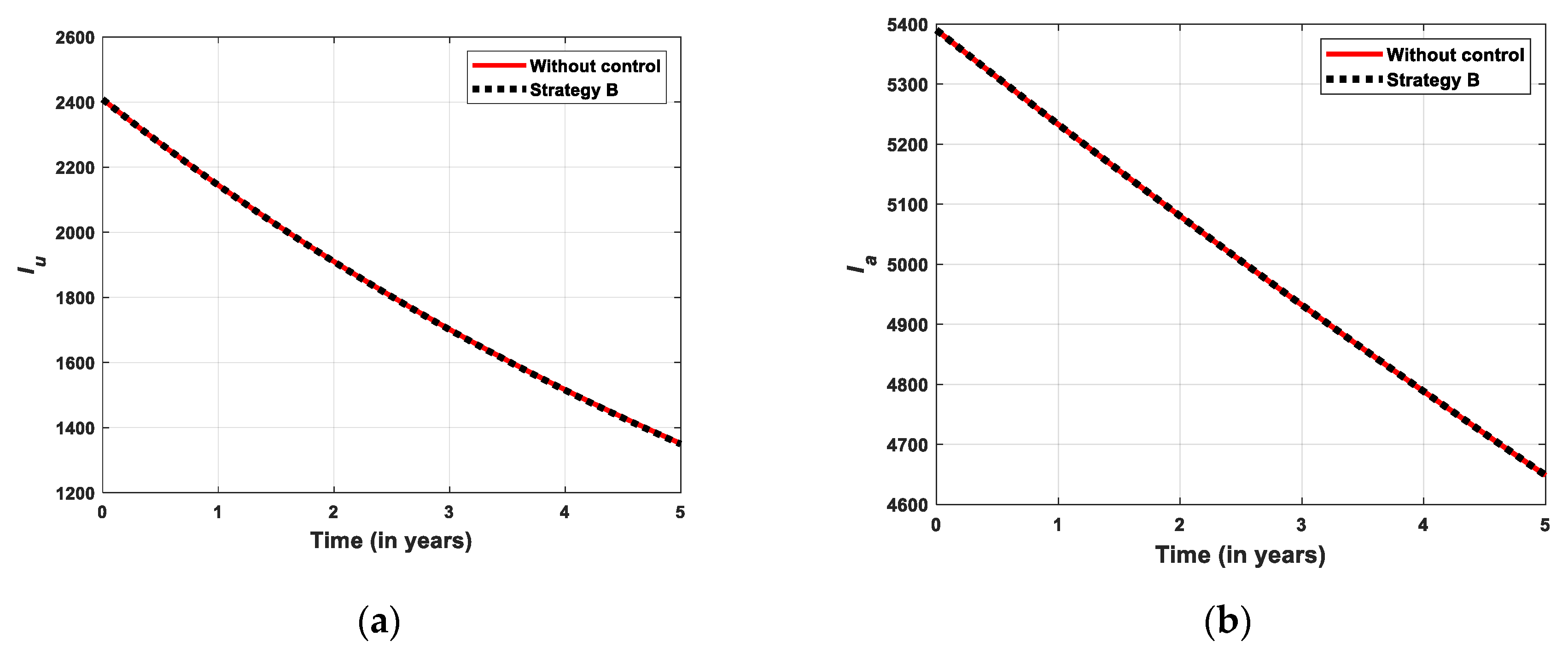

- Strategy B: Educational campaign combined with treatment

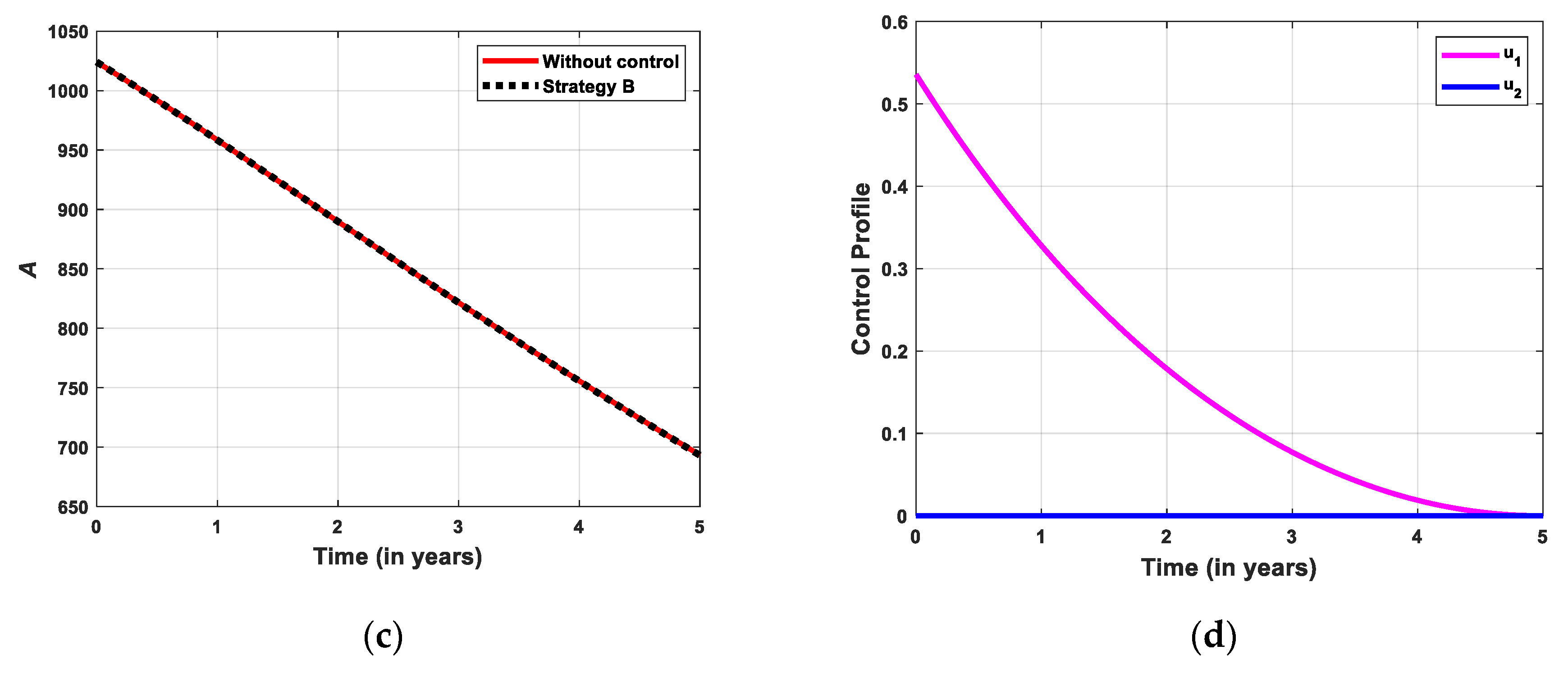

- Strategy C: Screening combined with treatment

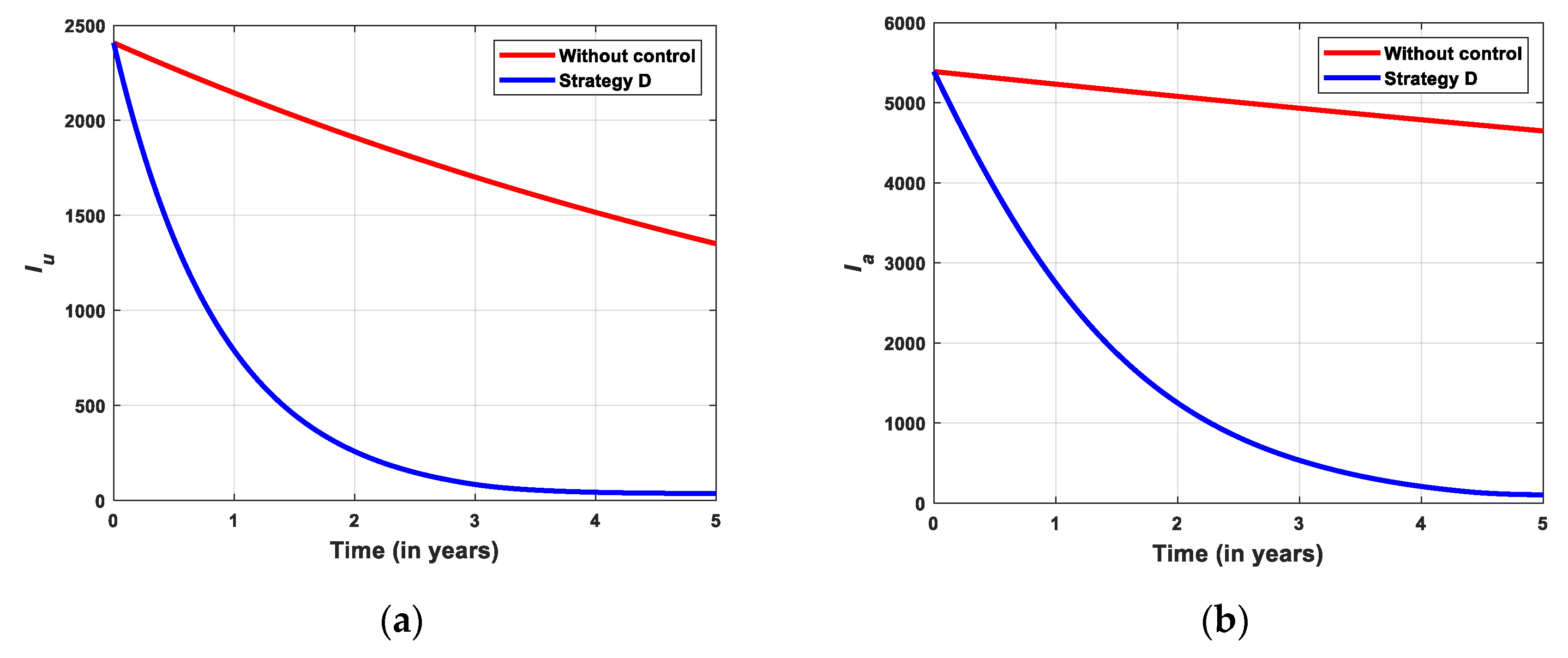

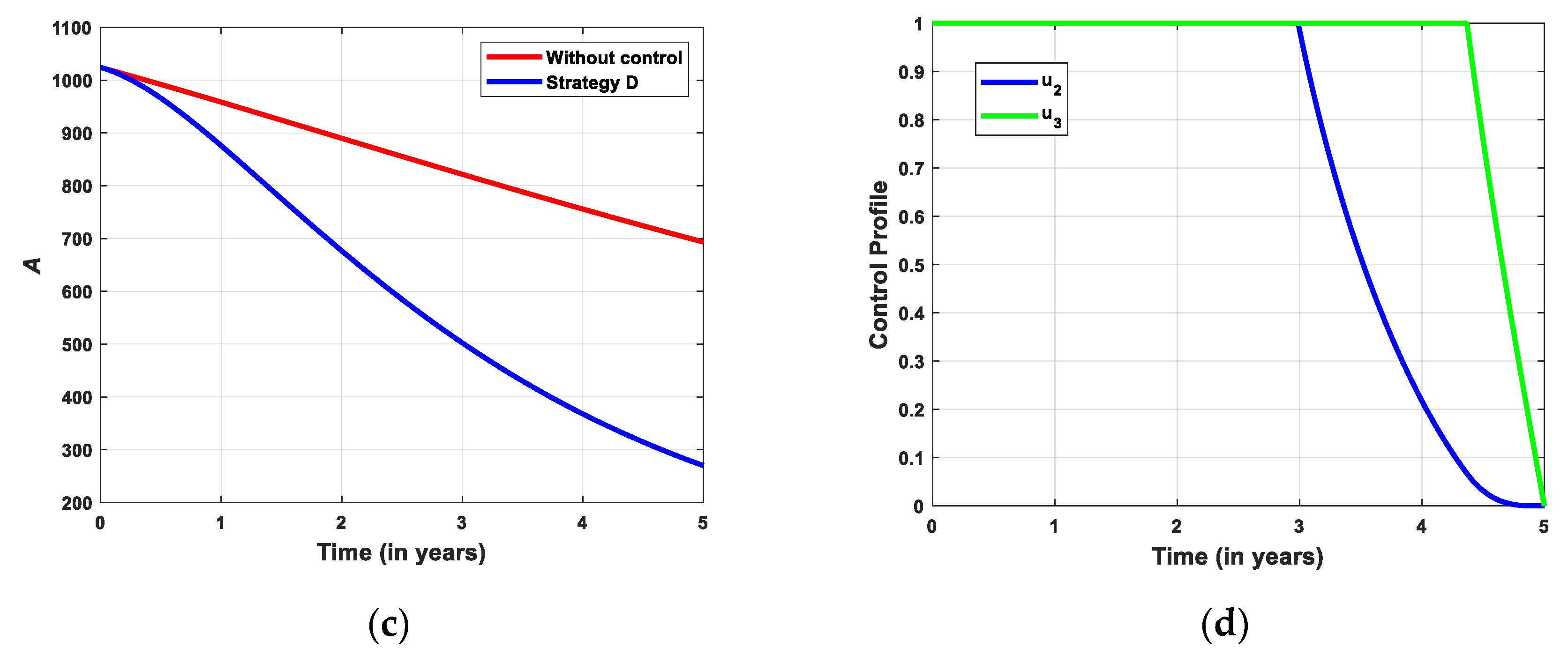

- Strategy D: Implementation of all control

5.2.1. Simulation for Strategi A

5.2.2. Simulation for Strategi B

5.2.3. Simulation for Strategi C

5.2.3. Simulation for Strategi C

5.2.4. Simulation for Strategi D

5.3. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO): Global strategic direction on HIV/AIDS 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and-development/analyses-and-syntheses/hiv-aids/global-strategic-direction (accessed on 17th February 2025).

- UNAIDS. (2024). Global HIV & AIDS statistics-Fact sheet. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed on 17th February 2025).

- Bekker, L.G.; Beyrer, C.; Quinn, T. C. Behavioural and biomedical combination strategies for HIV prevention. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a007435. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H.R.; Lenhart, S.; Hota, S.; Agusto, F. Optimal Control of an SIR Model with Changing Behavior through an Education Campaign. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2015, 50,1-14. http://ejde.math.txstate.edu.

- Hota, S.; Agusto, F.; Joshi, H.R.; Lenhart, S. Optimal control and stability analysis of an epidemic model with education and treatment. Conferensi Publication, 2015, 2015(special), 621-634. https://www.aimsciences.org/article/doi/10.3934/proc.2015.0621.

- Mukandavire, Z.; Garira, W. Effects of Public Health Educational Campaigns and the Role of Sex Workers on the Spread of HIV/AIDS among Heterosexuals. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2007, 72, 346-365. [CrossRef]

- Marsudi; Trisilowati; Suryanto, A.; Darti, I. Global stability and optimal control of an HIV/AIDS epidemic model with behavioral change and treatment. Eng. Lett. 2021, 29, 575-591. https://www.engineeringletters.com/issue_v29/issue_2/EL_29_2_26.pdf.

- Safiel, R.; Massawe, E.S.; Makinde, O.D. Modelling the effect screening and treatment on transmission of HIV/AIDS infection in a population. Am. J. Math. Stat. 2012, 2, 75-88. [CrossRef]

- Okosun, K.O.; Makinde, O.D.; Takaidza, I. Impact of optimal control on the treatment of HIV/AIDS and screening of unaware infectives. Appl. Math, Modelling, 2013, 37, 3802-3820. [CrossRef]

- Kateme, E.L.; Tchuenche, J.M.; Hove-Musekwa, S.D. HIV/AIDS Dynamics with Three Control Strategies: The Role of Incidence Function. ISRN Appl. Math. 2012, 864795. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ismail,M.; Ullah, S.; Farhan, M. Fractional order SIR model with generalized incidence rate. AIMS Math. 2020, 5, 1856-1880. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Khan, Y.; Islam, S. Complex dynamics of an SEIR epidemic model with saturated incidence rate and treatment. Physica A. 2018, 493, 210-227. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378437117310488.

- M. M. Ojo. Mathematical modelling of disease dynamics with saturated incidence and treatment response. Math. Biosci. 2021, 340, 108686. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2021.108686.

- Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, S. Analysis and optimal control of a two-strain SEIR epidemic model with saturated treatment rate. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3026. [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, S.; Kareem, G.G.; Abimbade, S.F.; Chuma, F.M.; Sangoniyi, S.O. Mathematical modelling and analysis of autonomous HIV/AIDS dynamics with vertical transmission and nonlinear treatment. Iran. J. Sci. 2024, 48, 181-192. [CrossRef]

- Allali, K.; Balde, M.A.M.T.; Ndiaye, B.M. An optimal control study for a two-strain SEIR epidemic model with saturated incidence rates and treatment. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2025, 2025, 8553106, 16 pages. [CrossRef]

- Pontryagin, L.S.; Boltyanskii, V.G.; Gamkrelidge, R.V.; Mishchenko, E.F. Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes, 1st edition, Routledge: London, 1987.

- Lenhart, S.; Workman, J.T. Optimal Control Applied to Biological Models, 1st edition, Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, 2007.

- Yusuf, T.T.; Benyah, F. Optimal strategy for controlling the spread of HIV/AIDS disease: A case study of South Africa. J. Biol. Dyn. 2012, 6, 475-494.

- Teklu, S.W. Investigating the effects of intervention strategies on pneumonia and HIV/AIDS co-infection model. Biomed Res. Int. 2023, 5778209. [CrossRef]

- Teklu, S.W.; Terefe, B.B.; Mamo, D.K.; Abebaw, Y.F. Optimal control strategies on HIV/AIDS and pneumonia co-infection with mathematical modelling approach. J. Biol. Dyn. 2024, 18, 2288873. [CrossRef]

- Teklu, S.W.; Workie, A.H. A dynamical optimal control theory and cost-effectiveness analysis of the HBV and HIV/AIDS co-infection model. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1444911. [CrossRef]

- Berhe, H.W.; Makinde, O.D.; Theuri, D.M. Co-dynamics of measles and dysentery diarrhea diseases with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 347. [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, S.; Okosun, K.O.; Adesanya, S.O.; Lebelo, R.S. Modelling malaria dynamics with partial immunity and protected travellers: optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Biol. Dyn. 2020, 14, 90-115. [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, J.K.K.; Yankson, E.; Okyere, E.; Sun, G.Q.; Jin, Z.; Jan, R. et al. Optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis for dengue fever model with asymptomatic and partial immune individuals. Results Phys. 2021, 31, 104919. [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, J.K.K.; Okyere, E.; Abidemi, A.; Moore, S.E.; Sun, G.Q.; Jin, Z. et al. Optimal control and comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis for COVID-19. Results Phys. 2022, 33, 105177. [CrossRef]

- Appiah, R.F.; Jin, Z.; Yang, J.; Asamoah, J.K.K. Optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis for a tuberculosis vaccination model with two latent classes. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 6761-6785.

- Engida, A; Gathungu, D.K.; Ferede, M.M.; Belay, M.A.; Kawe, P.C.; Mataru, B. Optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis for the human melioidosis model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26487. [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.L.; Huo, H.F. Dynamics and optimal control of tuberculosis with the combined effects of vaccination, treatment and contaminated environments. Math. Biosci. Engin. 2024, 21, 5308-5334. https://www.aimpress.com/journal/MBE.

- Smith, H.L.; Waltman, P. The Theory of the Chemostat: Dynamics of Microbial Competition, Cambride University Press: Cambride UK, 1995.

- van den Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and subthreshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002, 180, 29-48. [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P.; Metz, J.A.J. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in , 28odels for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 1990, 28, 365-382. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF00178324.

- Muthu, P.M.; Kumar, A.P. Optimal control and bifurcation analysis of SEIHR model for COVID-19 with vaccination strategies and mask efficiency. Comput. Math. Biophys., 2024, 12, 20230113. [CrossRef]

- LaSalle, J.P. The Stability of Dynamical System, In: CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics, Pa: SIAM, Philadelphia, 1976.

- Castillo-Chavez, C.; Song, B. Dynamical models of tuberculosis and their applications. Math. Biosci. Eng., 2004, 1, 361-404. [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, N.; Hyman, J.M.; Cushing, J.M. Determining important parameters in the spread of malaria through the sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model. Bull. Math. Biol. 2008, 70, 1272-1296. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.H.; Rishel, R.W. Deterministic and Stochastic Optimal Control, Springer: New York, 1975.

- Bector, C.R.; Chandra, S.; Dutta, J. Principles of Optimization Theory, Narosa Publishing House: New Delhi, 2005.

- Abidemi, A.; Fatmawati, Peter, O. J. An optimal control model for dengue dynamics with asymptomatic, isolation, and vigilant compartments. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 10, 100413. [CrossRef]

- Aldila, D.; Dhanendra, R.P.; Khoshnaw, S.H.A.; Puspita, J.W.; Kamalia, P.Z.; Shahzad, M. Understanding HIV/AIDS dynamics: insight from CD4+T cells, antiretroviral treatment, and country-specific analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1324858. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of recruitment | 2000 | [6] | |

| Natural death rate | 0.0196 | [6] | |

| The rate of screening of unaware infective | 0.6 | [6] | |

| The efficiency of education campaigns in | 0.75 | Assumed | |

| The efficiency of education campaigns in | 0.6 | Assumed | |

| The rate of educating adults into E1 | 0.4 | [6] | |

| The rate of educating adults into | 0.091 | Assumed | |

| The rate of educating adults into | 0.067 | Assumed | |

| The rate of treatment of aware infectious | 0.6 | [9] | |

| Progression rate from unaware infectious to AIDS | 0.1 | [8] | |

| Progression rate from aware infectious to AIDS | 0.01 | [8] | |

| Progression rate from treated infection to AIDS | 0.001 | [8] | |

| The modification parameter relative infectivity of individuals in | 0.023 | Assumed | |

| The modification parameter relative infectivity of individuals in | 0.0016 | Assumed | |

| The rate of treatment of screened infectious | 0.33 | [6] | |

| The psychological or inhibitory effect | 4 | [10] |

| Parameter | Sensitivity Indices | Parameter | Sensitivity Indices |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -0.1389 | ||

| 0.9999 | -0.0517 | ||

| -0.8083 | 0.0417 | ||

| -0.7716 | 0.0206 | ||

| -0.6925 | -0.0176 | ||

| -0.4079 | -0.0020 | ||

| -0.2605 | -0.0009 | ||

| -0.2088 |

| Strategy | TA | TC | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy B: | 4.7007 | 4.0169 | 0.8545 |

| Strategy D: | 25999.8318 | 526.3404 | 0.0201 |

| Strategy A: | 25999.9067 | 526.4049 | 0.8612 |

| Strategy C: | 26013.4355 | 344.4764 | -13.4475 |

| Strategy | TA | TC | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy D: | 25999.8318 | 526.3404 | 0.0202 |

| Strategy A: | 25999.9067 | 526.4049 | 0.8612 |

| Strategy C: | 26013.4355 | 344.4764 | -13.4475 |

| Strategy | TA | TC | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy D: | 25999.8318 | 526.3404 | 0.0202 |

| Strategy C: | 26013.4355 | 344.4764 | -5.3685×10-5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).