1. Introduction

Graph-based question answering tasks—such as shortest path identification, node classification, and community detection—require both language understanding and structural reasoning over non-Euclidean data. Traditional methods work well for clearly defined problems, but they struggle with complex multimodal queries and dynamic graphs.

Recent work has improved multimodal reasoning. Wang et al.[

1] developed VQA-GNN, a model that integrates multimodal knowledge using graph neural networks (GNNs), improving reasoning in visual question answering tasks. Liang et al.[

2] analyze GraphRAG’s security, introduce GRAGPoison—a novel graph-based poisoning attack—and demonstrate its high efficacy and scalability while revealing gaps in current defenses.

Large language models (LLMs) like Gemini excel in natural language understanding, but they are not designed for graph-structured data. GNNs are good at encoding graph structures but do not have the generative ability needed for natural language interaction.

To solve this, we propose Gemini-GraphQA, a framework that combines LLMs and GNNs for efficient graph question answering. The framework uses a graph encoder based on GNNs to generate graph embeddings, which are then translated into executable Python code by a graph solver network. An execution correctness loss ensures that the code is syntactically and functionally correct. A retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) module retrieves external knowledge, improving the understanding of context and enhancing generalization across domains.

2. Related Work

Graph-based question answering (GraphQA) has become an important field in natural language processing (NLP) and knowledge representation. Traditional methods for knowledge graph-based question answering often rely on predefined graph structures and rule-based methods. Zhang and Bhattacharya [

3]develop an iterated learning framework that uses neural network surrogates—trained via repeated small-scale simulations—to achieve history-dependent, multiscale modeling of architectured metamaterials with FE²-level accuracy at empirical-model cost. Similarly, Khademi[

4] proposed a multimodal neural graph memory network (MN-GMN) for visual question answering (VQA), which uses graph structures to model relationships between different regions in an image.

In the field of knowledge graphs, Sidiropoulos et al.[

5] explored simple question answering for unseen domains, introducing methods to integrate new domains during testing. This work demonstrated how dynamic graph structures can support real-time updates in evolving systems. Wang et al.[

6]introduce an attention-based LSTM network for adaptive sensor selection that jointly recognizes failure modes and predicts remaining useful life under time-varying operating conditions using semisupervised learning and domain adaptation.Zhang et al.[

7] develop a Bayesian-type framework that leverages a finite-element–generated database and interpolation to infer plastic flow strength and strain-hardening exponent from conical indentation curves and surface profiles, yielding accurate stress–strain predictions even under noisy conditions.

In speech technology, Dai et al.[

8] introduced CAB-KWS, an unsupervised learning approach for keyword spotting in speech recognition, using contrastive augmentation to tackle sparse labeled data. This method shows the potential of using graph-based techniques in non-textual domains.Chen [

9] introduces a coarse-to-fine multi-view 3D reconstruction framework that integrates SLAM-based pose optimization, parallel bundle adjustment, and a Transformer-based matching module with a hybrid loss to achieve superior accuracy and robustness.Jin [

10] proposes a novel framework that combines an attention-based temporal convolutional network for accurate supply chain delay prediction with a multi-agent reinforcement learning module for cost-effective inventory optimization, demonstrating superior performance across MAE, MSE, R², and AUC metrics.

These studies have contributed to the development of graph-based reasoning across different applications, from visual data to speech, demonstrating the power of combining neural architectures with structured data for improving question answering systems.

3. Methodology

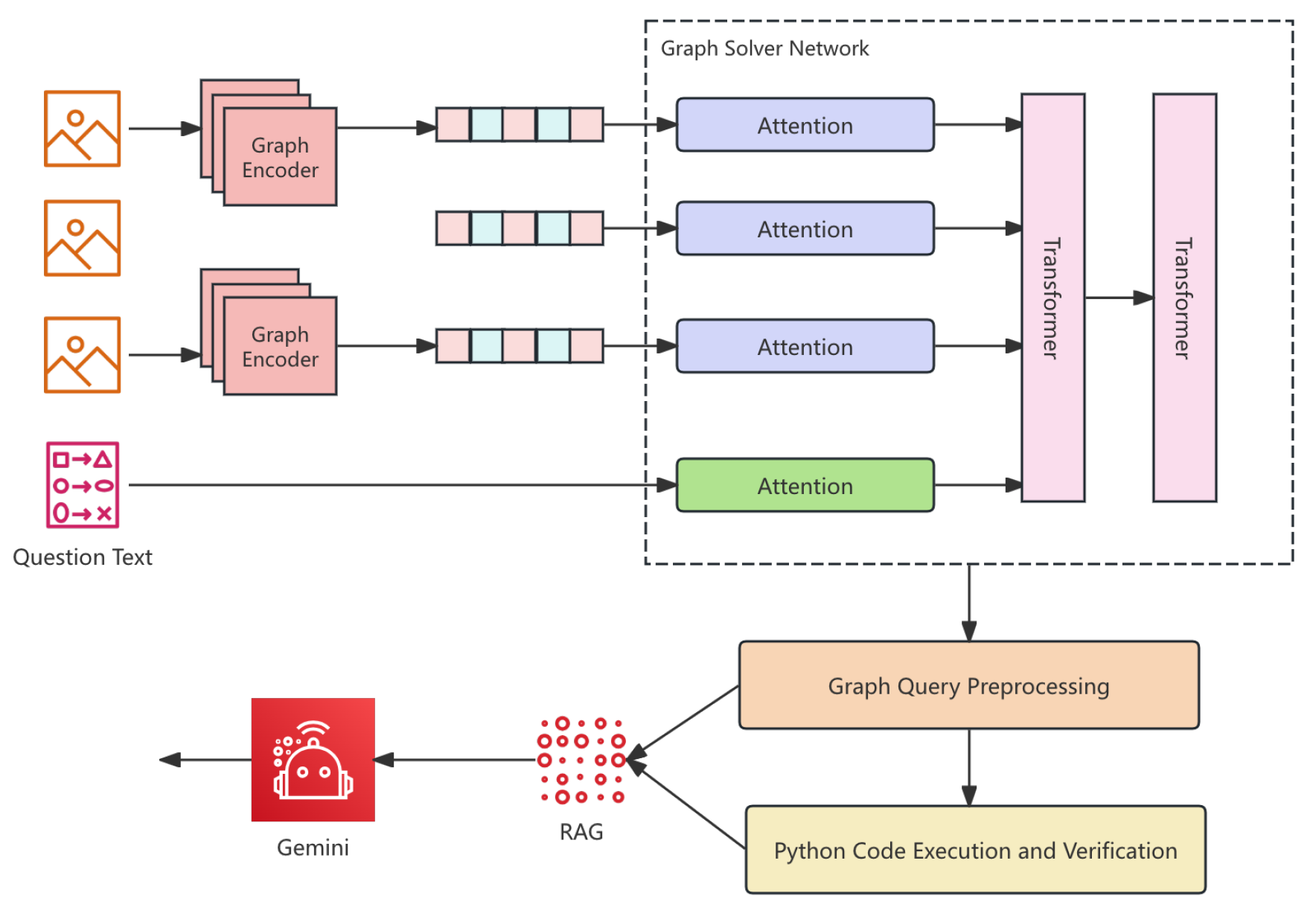

Gemini-GraphQA integrates a pre-trained Gemini language model with a graph reasoning module for graph-based question answering. It comprises three components: (i) the Gemini Language Model, (ii) a Graph Encoder that maps raw graphs to embeddings, and (iii) a Graph Solver Network that generates and runs Python code for tasks such as shortest-path search, node classification and community detection. A retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) mechanism injects external knowledge into the reasoning process. Training minimizes a dual-objective loss combining language generation and execution correctness, ensuring both syntactic validity and functional accuracy. Experimental results demonstrate that Gemini-GraphQA outperforms baselines in both accuracy and efficiency. The overall pipeline is shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Graph Encoder

The Graph Encoder is a core module in Gemini-GraphQA, responsible for converting raw graph inputs into representations suitable for integration with natural language queries. The graph is encoded as an adjacency matrix , where denotes the presence of an edge between nodes i and j.

A graph convolutional layer processes the adjacency matrix and node feature matrix

, yielding graph embeddings

:

These embeddings encode both structural and semantic information, serving as the foundation for graph-related reasoning within the framework.

3.2. Graph Solver Network

The Graph Solver Network fuses the natural language query with the graph representation from the Graph Encoder to generate executable Python code. Attention mechanisms are employed to jointly encode both modalities.

Query embeddings

and graph embeddings

are first processed via separate self-attention layers:

The resulting outputs are concatenated to form a unified representation:

This joint vector is fed into Transformer decoder layers to generate a token sequence representing Python code

C, which addresses graph-related tasks such as shortest path queries, node classification, or community detection. For instance, a shortest-path query yields:

The output code is directly executable to solve the corresponding task.

3.3. Graph Query Preprocessing

Prior to model input, both the graph data and natural language query are preprocessed into structured formats. Graphs stored in JSON are parsed and converted into adjacency matrices A, while textual graph descriptions are transformed into structured representations.

The input query

is tokenized using a pre-trained tokenizer to yield embeddings

. Formally, the tokenization process is:

where

is the tokenizer and

denotes the

i-th token.

The graph G is encoded as an adjacency matrix A, optionally containing edge weights for weighted graphs. This preprocessing facilitates effective learning from both the query and graph structure.

3.4. Python Code Execution and Verification

This module executes the generated Python code C and verifies its correctness. The code is run in a secure environment to solve the target graph task.

Correctness is validated by comparing the execution result

with the ground truth

, using an execution correctness loss:

where

is a tunable penalty weight and

is the indicator function.

The overall training objective combines the generation loss

, which ensures syntactic validity, and the correctness loss:

This joint loss encourages the model to produce both valid and semantically correct Python code for solving graph-related tasks.

3.5. Incorporating External Data and Augmentation

To enhance Gemini-GraphQA’s performance, we adopt a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) mechanism that integrates external knowledge—such as graph algorithm documentation or supplementary datasets—into the reasoning process.

The mechanism retrieves relevant documents

, encodes them into embeddings

, and incorporates these into the joint representation:

This augmentation enables the model to address complex queries and rare edge cases with improved contextual understanding.

3.6. Loss Function

Gemini-GraphQA optimizes a composite loss to ensure generated Python code is both syntactically valid and functionally correct.

3.6.1. Language Generation Loss

To enforce syntactic correctness, the model minimizes a cross-entropy loss between the predicted code sequence

and the ground truth

:

where

denotes the predicted probability of token

given preceding tokens.

3.6.2. Execution Correctness Loss

The execution correctness loss compares the result

from executing the generated code with the true result

:

where

is an indicator function and

is a penalty weight for incorrect execution.

3.6.3. Total Loss Function

The total loss combines both terms:

ensuring the model produces code that is both valid and correct in execution.“‘

4. Data Preprocessing

The Gemini-GraphQA framework preprocesses both graph data and natural language queries through three steps: graph encoding, query tokenization, and graph-query integration.

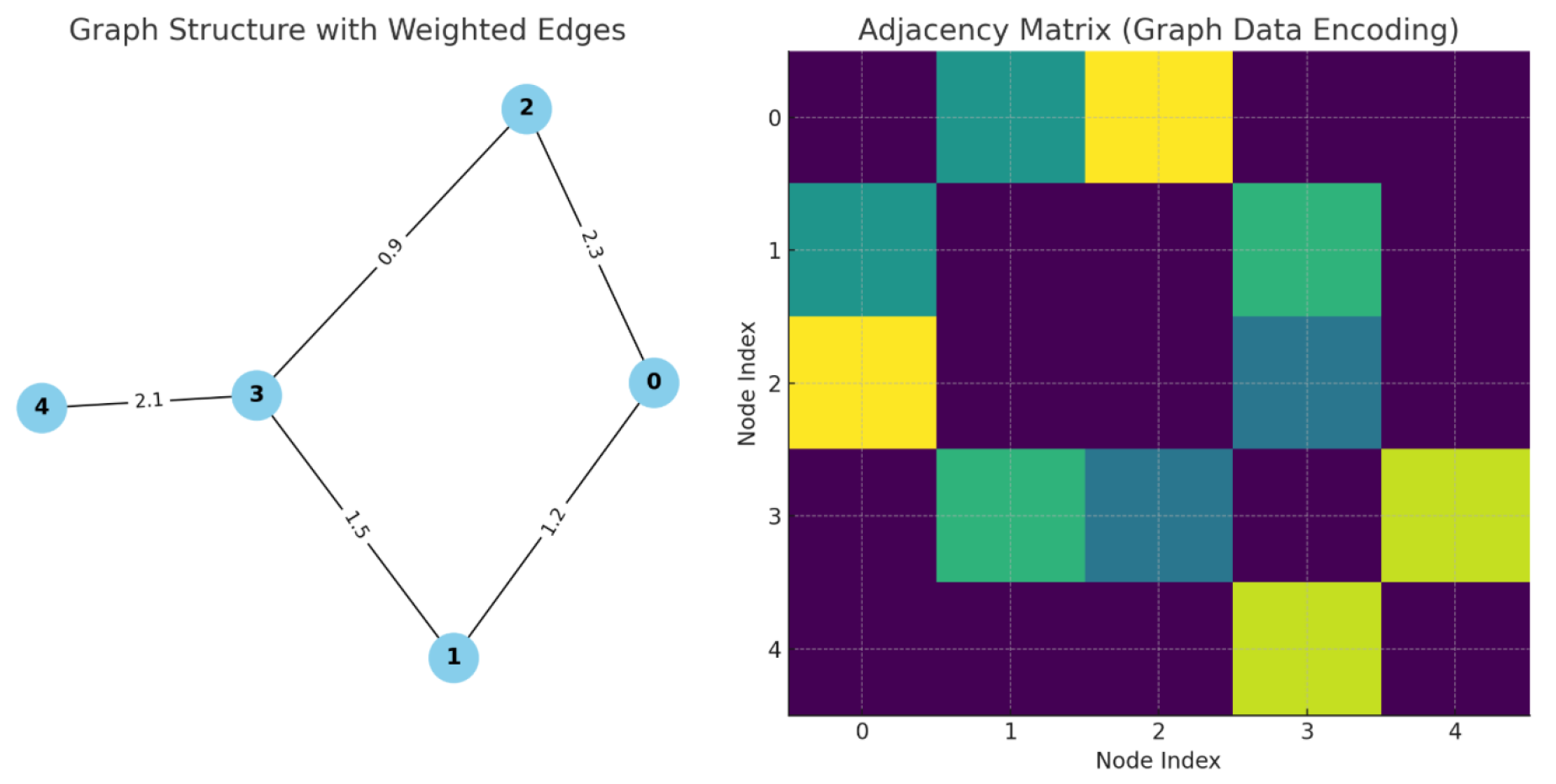

4.1. Graph Data Encoding

Graphs are represented as adjacency matrices

A, where

denotes the edge weight between nodes

i and

j:

The matrix

A and node features

X (if present) are processed by a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to produce node embeddings

:

An illustration of the graph structure and encoding is shown in

Figure 2.

4.2. Query Tokenization

The query

is tokenized using a pre-trained model, yielding embeddings

:

This enables effective processing of natural language input.

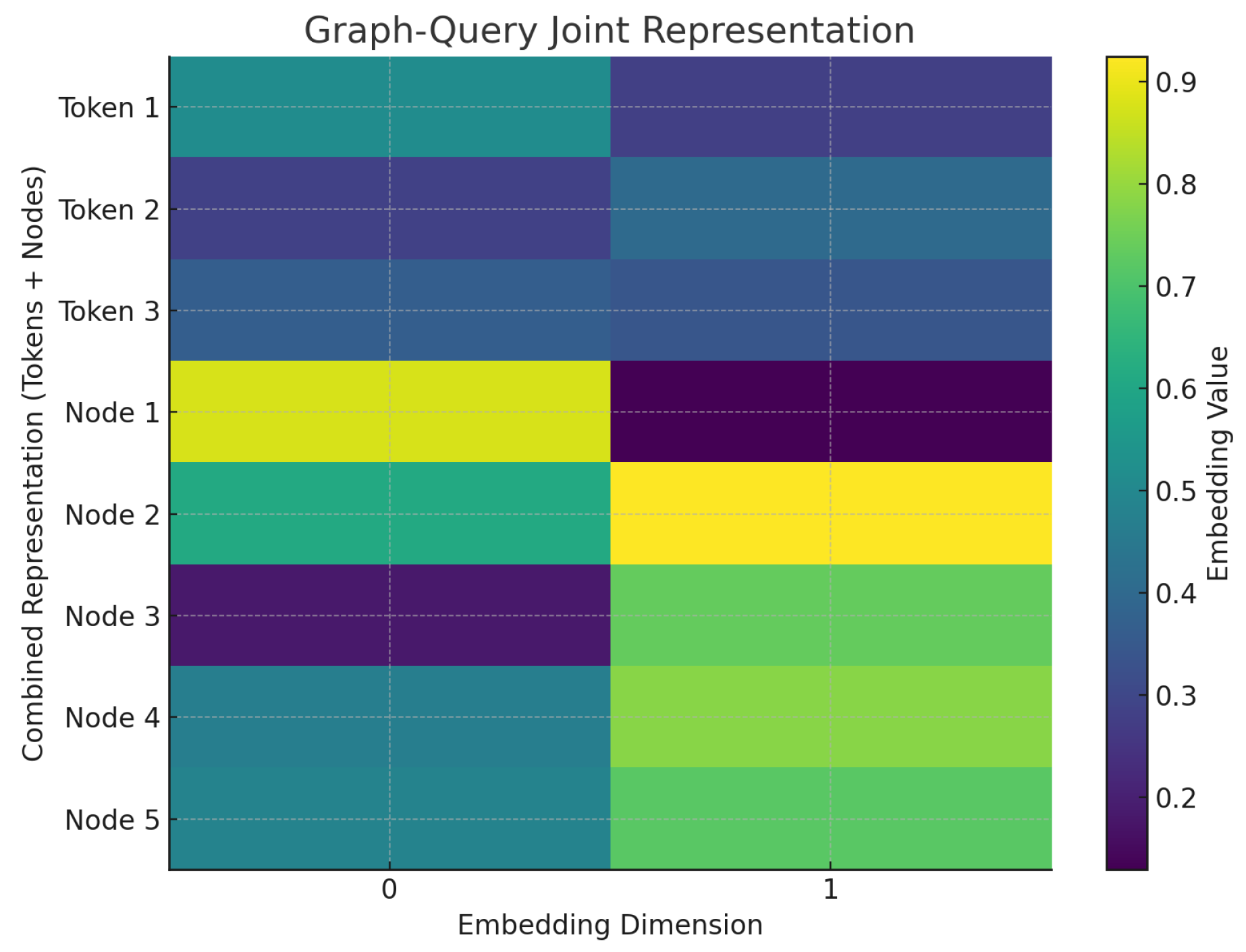

4.3. Graph-Query Integration

Graph embeddings

and query embeddings

are concatenated to form a unified representation:

This joint vector

is input to the Graph Solver Network for Python code generation.

Figure 3 illustrates the integration process.

5. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate the Gemini-GraphQA framework using four key metrics:

5.1. Accuracy

Measures whether the generated code produces correct results:

where

and

are the executed and ground truth results, respectively.

5.2. Code Quality Score

Assesses the syntactic and logical correctness of generated code:

with scores ranging from 0 to 1.

5.3. Execution Time Efficiency

Evaluates average runtime of generated code:

5.4. F1-Score

Quantifies the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

This is particularly relevant for multi-output evaluation tasks.

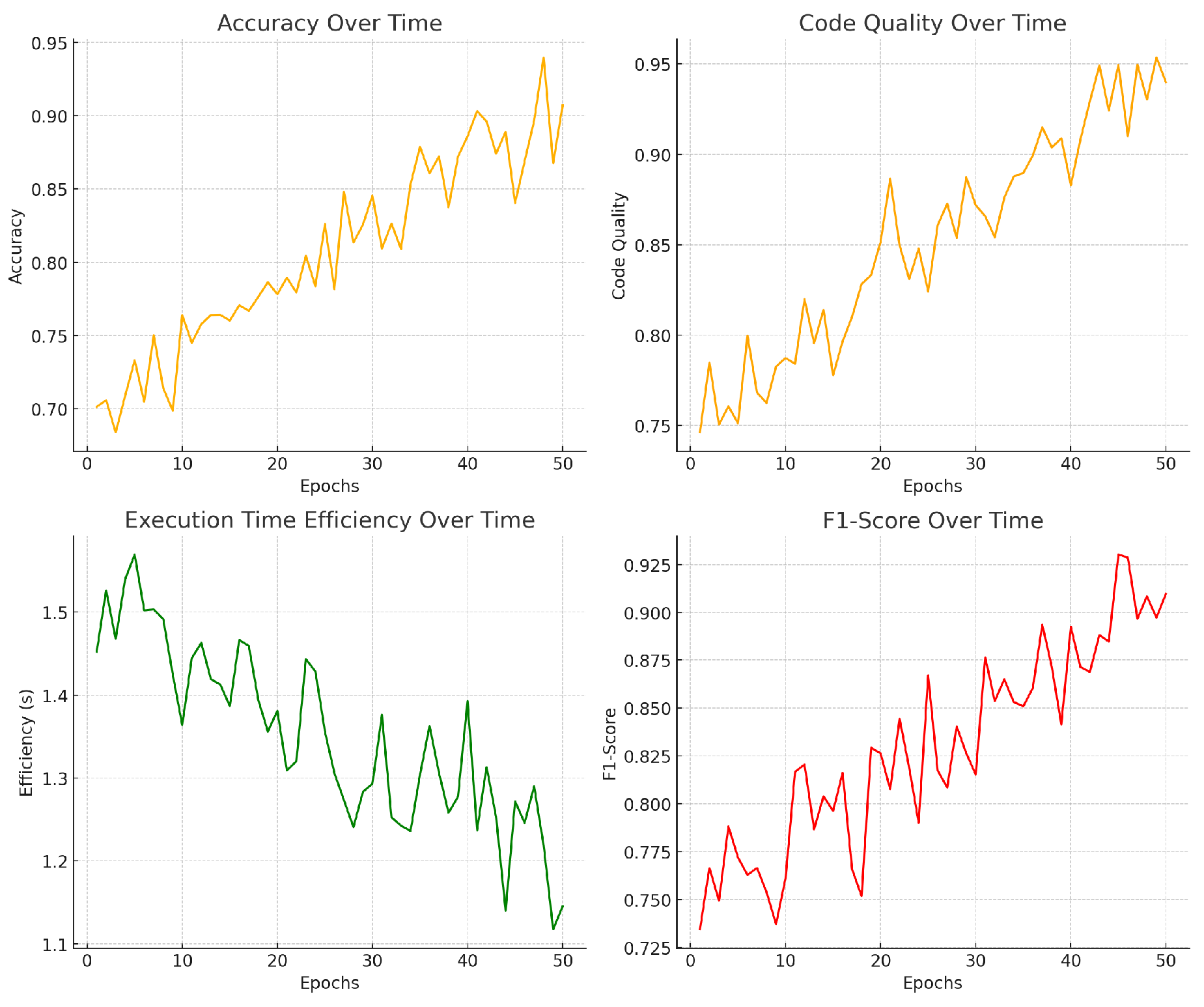

6. Experiment Results

We evaluate the Gemini-GraphQA model against two baselines: a Traditional Graph Algorithm (TGA) and a Pretrained Code Generation Model (PCGM). The results across all evaluation metrics are shown in

Table 1.

An ablation study was conducted to evaluate the impact of key components in Gemini-GraphQA. We removed the execution correctness loss and the graph encoder to analyze their contributions. The results are shown in

Table 2 and the changes in model training indicators are shown in

Figure 4.

.

7. Conclusion

In this work, we proposed the Gemini-GraphQA framework, which generates Python code to answer graph-related questions. We demonstrated that the model outperforms existing approaches in terms of accuracy, code quality, execution time efficiency, and F1-score. Our ablation study further confirmed the importance of key components such as the execution correctness loss and graph encoder. Overall, Gemini-GraphQA provides an effective solution for graph-based question answering tasks and showcases the potential of combining graph representation learning with natural language code generation.

References

- Wang, Y.; Yasunaga, M.; Ren, H.; Wada, S.; Leskovec, J. Vqa-gnn: Reasoning with multimodal knowledge via graph neural networks for visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 21582–21592. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, R.; Jiang, T.; Gong, N.; Wang, T. GraphRAG under Fire. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv:2501.14050. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bhattacharya, K. Iterated learning and multiscale modeling of history-dependent architectured metamaterials. Mechanics of Materials 2024, 197, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, M. Multimodal neural graph memory networks for visual question answering. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020; pp. 7177–7188. [Google Scholar]

- Sidiropoulos, G.; Voskarides, N.; Kanoulas, E. Knowledge graph simple question answering for unseen domains. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2005.12040. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Hart, J.D.; Needleman, A. Identification of plastic properties from conical indentation using a bayesian-type statistical approach. Journal of Applied Mechanics 2019, 86, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, D.; Wang, D. Deep Learning-Based Sensor Selection for Failure Mode Recognition and Prognostics Under Time-Varying Operating Conditions. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, X.; Tao, J. CAB-KWS: Contrastive Augmentation: An Unsupervised Learning Approach for Keyword Spotting in Speech Technology. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition; Springer, 2025; pp. 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Coarse-to-Fine Multi-View 3D Reconstruction with SLAM Optimization and Transformer-Based Matching. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML). IEEE; 2024; pp. 855–859. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, T. Attention-based temporal convolutional networks and reinforcement learning for supply chain delay prediction and inventory optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1527–1531. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).