1. Introduction

Skin grafting plays a pivotal role in the surgical reconstruction of extensive wounds, including deep burns and full-thickness skin loss, by providing essential coverage and facilitating re-epithelialization [

1]. In clinical practice, large-area skin grafts are often indispensable for managing severe burns or traumatic injuries involving significant tissue loss. However, despite their utility in wound closure, grafted sites are frequently associated with long-term complications, notably scarring-related issues such as hypertrophy, rigidity, pigmentary disturbance, and contracture formation, which can substantially compromise both function and cosmetic outcomes [

2]. Conventional dermatologic interventions, such as CO2 laser resurfacing and intralesional corticosteroid injections, can reduce scar height and tension, thereby improving the appearance of certain scars; however, outcomes are frequently suboptimal [

3,

4,

5].

The Pinholxell method is an innovative laser-based treatment technique that combines two distinct yet complementary modalities. First, vertically oriented pinhole -columns are created in the scar tissue using a focused CO

2 laser in a pinhole configuration. This is immediately followed by the application of a fractional CO

2 laser over the same area, which enhances both epidermal resurfacing and dermal remodeling. This dual-step approach is designed to maximize regenerative signaling while minimizing thermal damage to the surrounding tissue [

6,

7]. This combined technique, by simultaneously targeting deep dermal remodeling and superficial epidermal renewal, induces the coordinated restoration of the dermal and epidermal architecture [

8].

This case series presents the clinical outcomes of five patients with post-skin graft scarring treated using the Pinholxell method. The treatment protocol involved multiple sessions, with long-term follow-up exceeding three years. In all cases, the Pinholxell technique demonstrated substantial improvements in scar appearance, including the normalization of pigmentation, a reduction in textural irregularities, and an increase in pliability. Furthermore, patients experienced meaningful symptomatic relief, including the resolution of pruritus, a reduction in pain, and an improved range of motion in affected areas. These findings suggest that the Pinholxell method may serve as an effective and safe treatment modality in the management of complex graft-related scars.

2. Method

The Pinholxell treatment was carried out in two sequential stages to promote synergistic dermal remodeling and epidermal resurfacing.

In the first stage, deep vertical pinhole columns measuring 1 mm in diameter were created in the scar tissue using a DS-40U CO2 laser (DSE, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The laser was set to a pulse duration of 200–500 μs with a repeat interval of 5 ms, allowing for precise and controlled thermal ablation into the deeper dermis. These microcolumns served as focal zones for initiating localized tissue regeneration.

In the second stage, a fractional CO

2 laser overlay was immediately applied using the eCO

2® system (Lutronic Corporation, Goyang, Republic of Korea) with parameters of 26 mJ and a density of 100 spots/cm². This overlay targeted the superficial layers and the intact zones between pinhole columns, facilitating re-epithelialization and optimizing the regenerative response (

Figure 1).

Topical anesthesia was achieved with a 5% lidocaine cream applied for one hour prior to each session. In clinical experience, extending the application time of the anesthetic cream was generally associated with improved patient comfort, suggesting a time-dependent reduction in procedural pain. Postoperative care included the application of petrolatum gauze for up to three days, followed by the use of a moisturizer and the intermittent application of clobetasol cream (0.05%). Pinholxell treatments were performed at two-month intervals, while fractional CO2 laser procedures were conducted every two to four months. The patients provided informed consent regarding the risks, benefits, and treatment options, and the protocol used was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration’s ethics guidelines.

3. Result

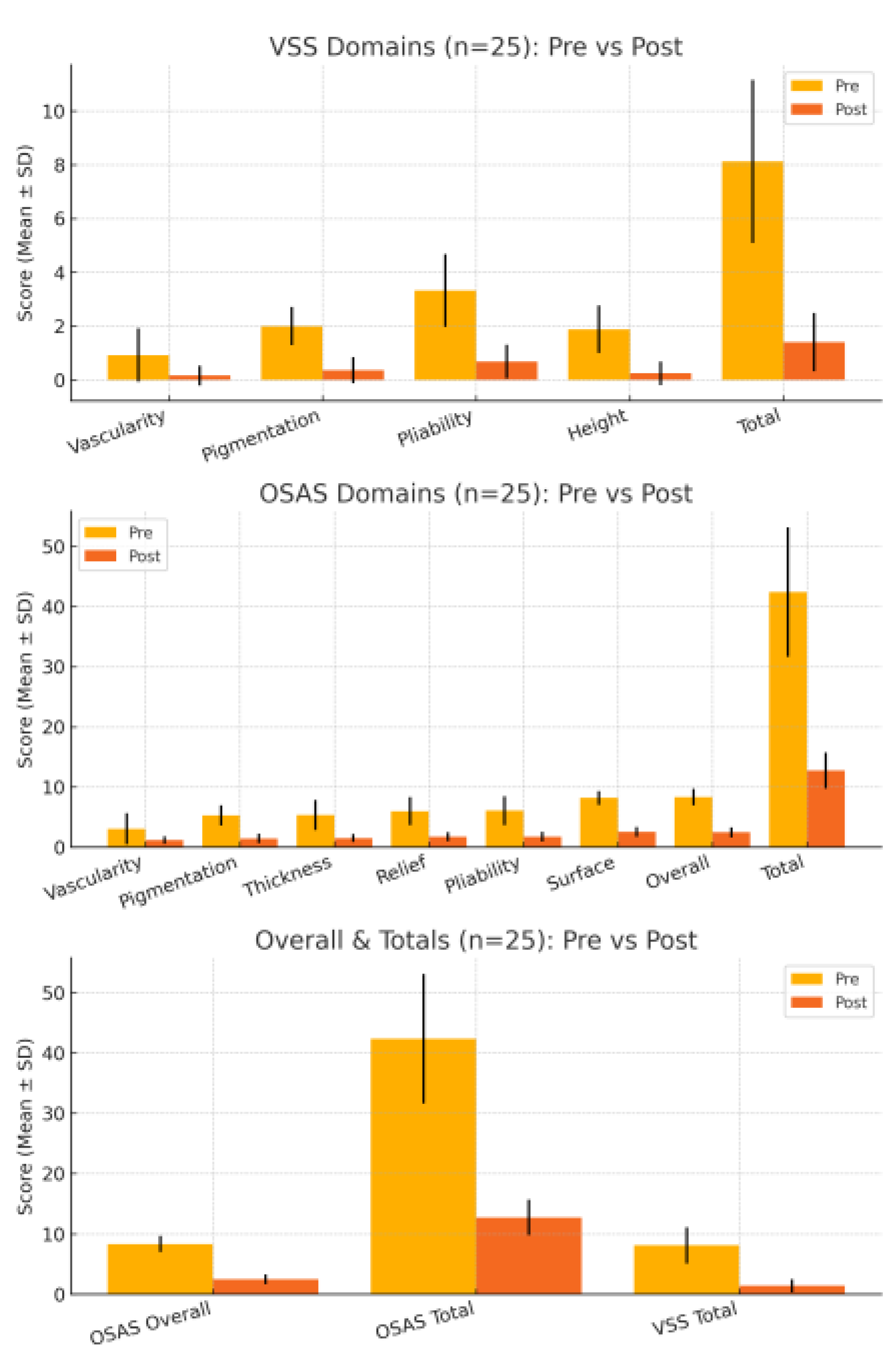

Twenty-five patients with skin graft scars completed the treatment protocol and were assessed using the Observer Scar Assessment Scale (OSAS) and the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS). All OSAS domains—vascularity, pigmentation, thickness, relief, pliability, and surface—demonstrated significant post-treatment improvement (all P < .001, paired t-test). Notably, vascularity, pigmentation, and thickness decreased from 3.08 ± 2.58 to 1.20 ± 0.65, 5.32 ± 1.68 to 1.48 ± 0.77, and 5.36 ± 2.48 to 1.52 ± 0.65, respectively. Relief and pliability improved from 6.00 ± 2.33 to 1.76 ± 0.72 and from 6.08 ± 2.41 to 1.76 ± 0.83, and the surface score showed the greatest absolute reduction from 8.20 ± 1.15 to 2.56 ± 0.82. The OSAS “Overall Opinion” improved from 8.36 ± 1.35 to 2.48 ± 0.82 (P < .001). The OSAS Total decreased from 42.40 ± 10.75 to 12.76 ± 2.96 (mean difference, 29.64; t = 16.417; P < .001), representing an overall ~70% reduction.

Table 1.

OSAS Score Statistics (n = 25).

Table 1.

OSAS Score Statistics (n = 25).

| Parameter |

Pre Mean ± SD |

Post Mean ± SD |

Mean Diff |

t-value |

p-value |

| Vascularity |

3.08 ± 2.58 |

1.20 ± 0.65 |

1.88 |

4.301 |

P < 0.001 |

| Pigmentation |

5.32 ± 1.68 |

1.48 ± 0.77 |

3.84 |

13.668 |

P < 0.001 |

| Thickness |

5.36 ± 2.48 |

1.52 ± 0.65 |

3.84 |

9.436 |

P < 0.001 |

| Relief |

6.00 ± 2.33 |

1.76 ± 0.72 |

4.24 |

11.163 |

P < 0.001 |

| Pliability |

6.08 ± 2.41 |

1.76 ± 0.83 |

4.32 |

11.316 |

P < 0.001 |

| Surface |

8.20 ± 1.15 |

2.56 ± 0.82 |

5.64 |

23.777 |

P < 0.001 |

| Overall |

8.36 ± 1.35 |

2.48 ± 0.82 |

5.88 |

19.852 |

P < 0.001 |

| Total Score |

42.40 ± 10.75 |

12.76 ± 2.96 |

29.64 |

16.417 |

P < 0.001 |

Table 2.

VSS Score Statistics (n = 25).

Table 2.

VSS Score Statistics (n = 25).

| Table |

Parameter |

Pre Mean ± SD |

Post Mean ± SD |

Mean Diff |

t-value |

p-value |

| VSS |

Vascularity |

0.92 ± 1.00 |

0.16 ± 0.37 |

0.76 |

3.919 |

P < 0.001 |

| VSS |

Pigmentation |

2.00 ± 0.71 |

0.36 ± 0.49 |

1.64 |

12.859 |

P < 0.001 |

| VSS |

Pliability |

3.32 ± 1.35 |

0.68 ± 0.63 |

2.64 |

11.475 |

P < 0.001 |

| VSS |

Height |

1.88 ± 0.88 |

0.24 ± 0.44 |

1.64 |

12.859 |

P < 0.001 |

| VSS |

Total |

8.12 ± 3.03 |

1.40 ± 1.08 |

6.72 |

13.483 |

P < 0.001 |

VSS outcomes likewise showed significant improvement across all domains—vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, and height (all P < .001, paired t-test). Mean vascularity decreased from 0.92 ± 1.00 to 0.16 ± 0.37, pigmentation from 2.00 ± 0.71 to 0.36 ± 0.49, pliability from 3.32 ± 1.35 to 0.68 ± 0.63, and height from 1.88 ± 0.88 to 0.24 ± 0.44. The VSS Total declined from 8.12 ± 3.03 to 1.40 ± 1.08 (mean difference, 6.72; t = 13.483; P < .001), corresponding to an overall ~83% reduction.

Figure placeholder: Mean ± SD scores for (A) VSS domains, (B) OSAS domains, and (C) OSAS Overall Opinion, OSAS Total, and VSS Total in 25 patients with skin graft scars before (yellow) and after (orange) treatment. All domains and total scores showed statistically significant improvement (P < .001, paired t-test).

3.1. Case 1

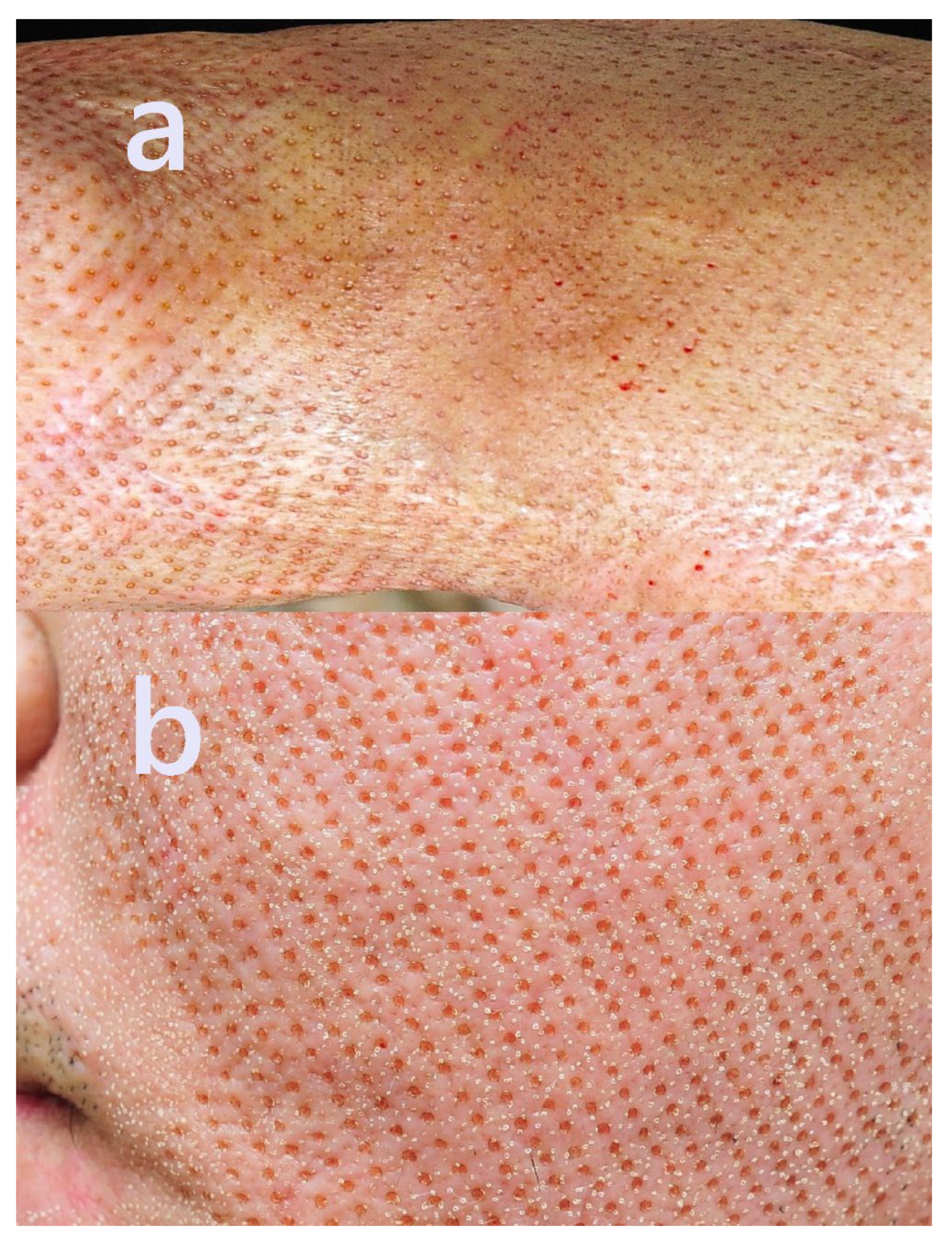

A 67-year-old male presented with early hypertrophic and keloid scarring 4 months after undergoing a skin graft for a chemical burn sustained 5 months prior. The graft site, located on the medial aspect of the foot and ankle, exhibited raised, darkly pigmented keloid tissue with irregular texture, surface scaling, and prominent nodular borders. The patient experienced severe pruritus, persistent pain, and difficulty walking due to tissue tightness and contracture at the ankle joint.

Total treatment time was 18 month.

The pigmentation of the scar significantly normalized. The previously dark violaceous and reddish discoloration diminished, blending more seamlessly with the surrounding skin.

There was a marked reduction in scar thickness and protrusion. The previously elevated, nodular keloidal margins flattened considerably, resulting in a more even surface contour.

The texture of the skin improved noticeably. The rough, scaly, and irregular surface observed before treatment became smoother, with improved elasticity and a healthy sheen.

Subjective symptoms, including persistent itching and pain, were fully relieved. The patient reported no discomfort during rest or ambulation following treatment.

Functional recovery was also observed. The initial gait disturbance caused by contracture and scar tightness around the ankle was resolved.

Figure 2.

Mean ± SD scores for (A) Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) domains, (B) Observer Scar Assessment Scale (OSAS) domains, and (C) OSAS Overall Opinion, OSAS Total, and VSS Total in 25 patients with skin graft scars before (yellow) and after (orange) treatment. All domains and total scores demonstrated statistically significant improvement (P < .001, paired t-test). The largest relative reductions were observed in pliability and pigmentation for VSS, and in surface, relief, and pliability for OSAS, with the greatest overall change in OSAS Overall Opinion and total scores.

Figure 2.

Mean ± SD scores for (A) Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) domains, (B) Observer Scar Assessment Scale (OSAS) domains, and (C) OSAS Overall Opinion, OSAS Total, and VSS Total in 25 patients with skin graft scars before (yellow) and after (orange) treatment. All domains and total scores demonstrated statistically significant improvement (P < .001, paired t-test). The largest relative reductions were observed in pliability and pigmentation for VSS, and in surface, relief, and pliability for OSAS, with the greatest overall change in OSAS Overall Opinion and total scores.

The patient regained the ability to walk unaided, indicating a significant improvement in mobility and joint flexibility.

When keloid formation accompanies the early stage of skin graft healing, the treatment becomes significantly more complex. The symptoms and scar thickness tend to fluctuate, alternating between improvement and worsening. However, with careful and experienced clinical judgment, timely interventions have been made, allowing the patient to recover steadily without complications. Pre- and post-treatment images are displayed in

Figure 3.

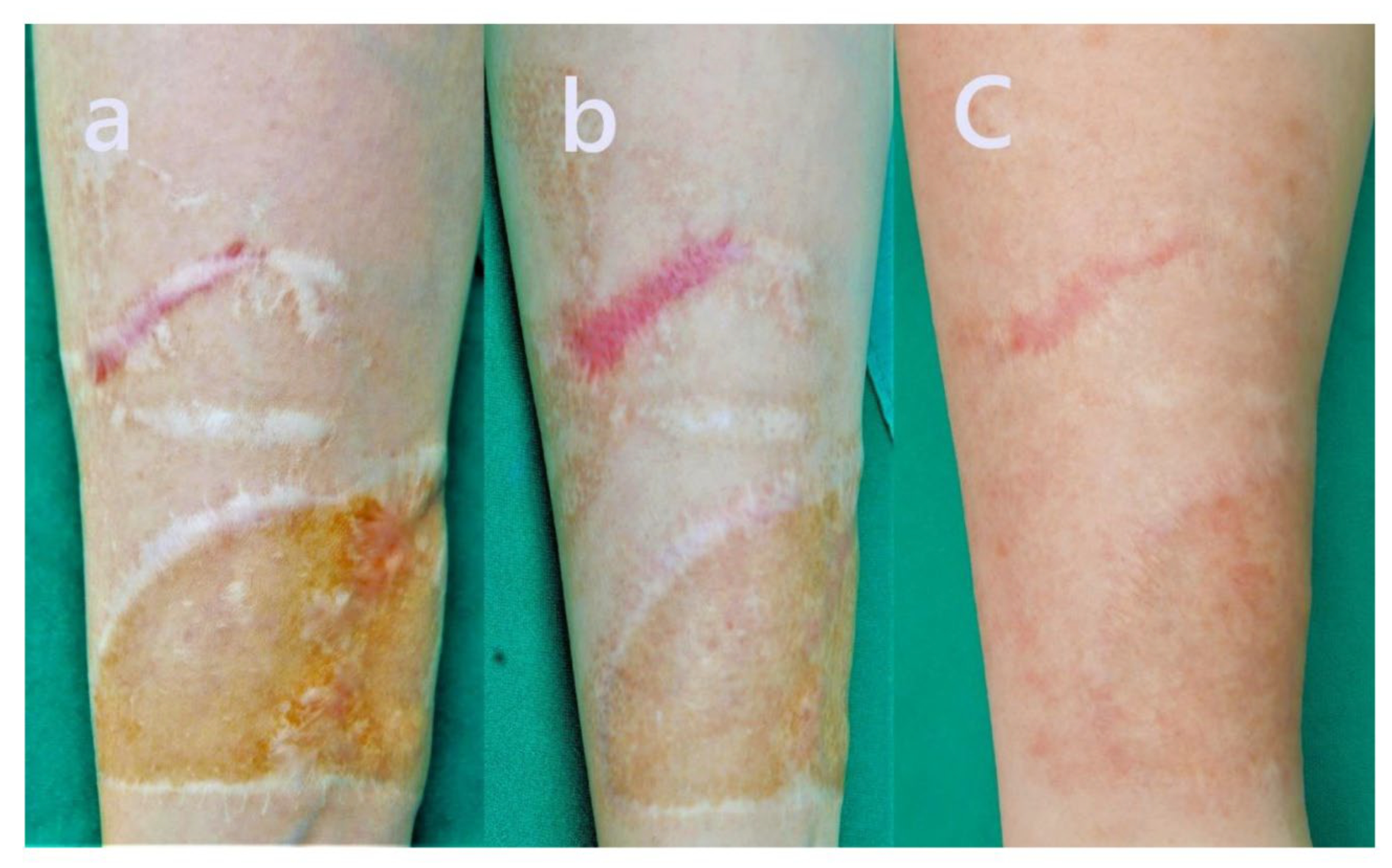

3.2. Case 2

A 38-year-old woman presented with hypertrophic changes at a forearm skin graft site one year following graft surgery for a childhood burn scar caused by candle wax. The distal margin of the graft exhibited keloidal scarring extending toward the dorsal aspect of the wrist. The patient experienced ongoing pruritus and pain, with the elevated scar tissue contributing to restricted wrist mobility secondary to contracture. She underwent five Pinholxell sessions and ten fractional CO2 laser procedures.

The total treatment time was 4 years and 4 months.

Scar thickness and firmness reduced noticeably, showing a smoother and more uniform texture.

Skin tone normalized, with reduced redness and the demarcation blended with the surrounding tissue.

Pain and itching completely resolved.

Wrist flexibility and range of motion improved significantly.

The patient reported being satisfied, and no complications occurred. Pre- and post-treatment images are displayed in

Figure 4.

3.3. Case 3

A 29-year-old man underwent facial skin grafting 10 years ago. The procedure was performed to address post-traumatic deformities resulting from a traffic accident sustained 25 years prior. Despite the prolonged interval, the skin graft remained incompletely integrated with the underlying dermis, and the grafted patches remained clearly demarcated. He underwent twelve consecutive Pinholxell sessions, followed by eight fractional CO2 laser procedures.

The total treatment time was 3 years and 3 months.

The scar surface became significantly flatter and less fibrotic, with a marked improvement in contour integration and reduced skin tension.

The hard, bumpy texture softened, and the demarcation lines visibly blended.

The color of the scar blended more harmoniously with the adjacent skin.

Overall facial symmetry improved, with perioral movement appearing more natural.

The treatment was well tolerated, with no reported complications. The patient expressed satisfaction with the results. Pre- and post-treatment images are displayed in

Figure 5.

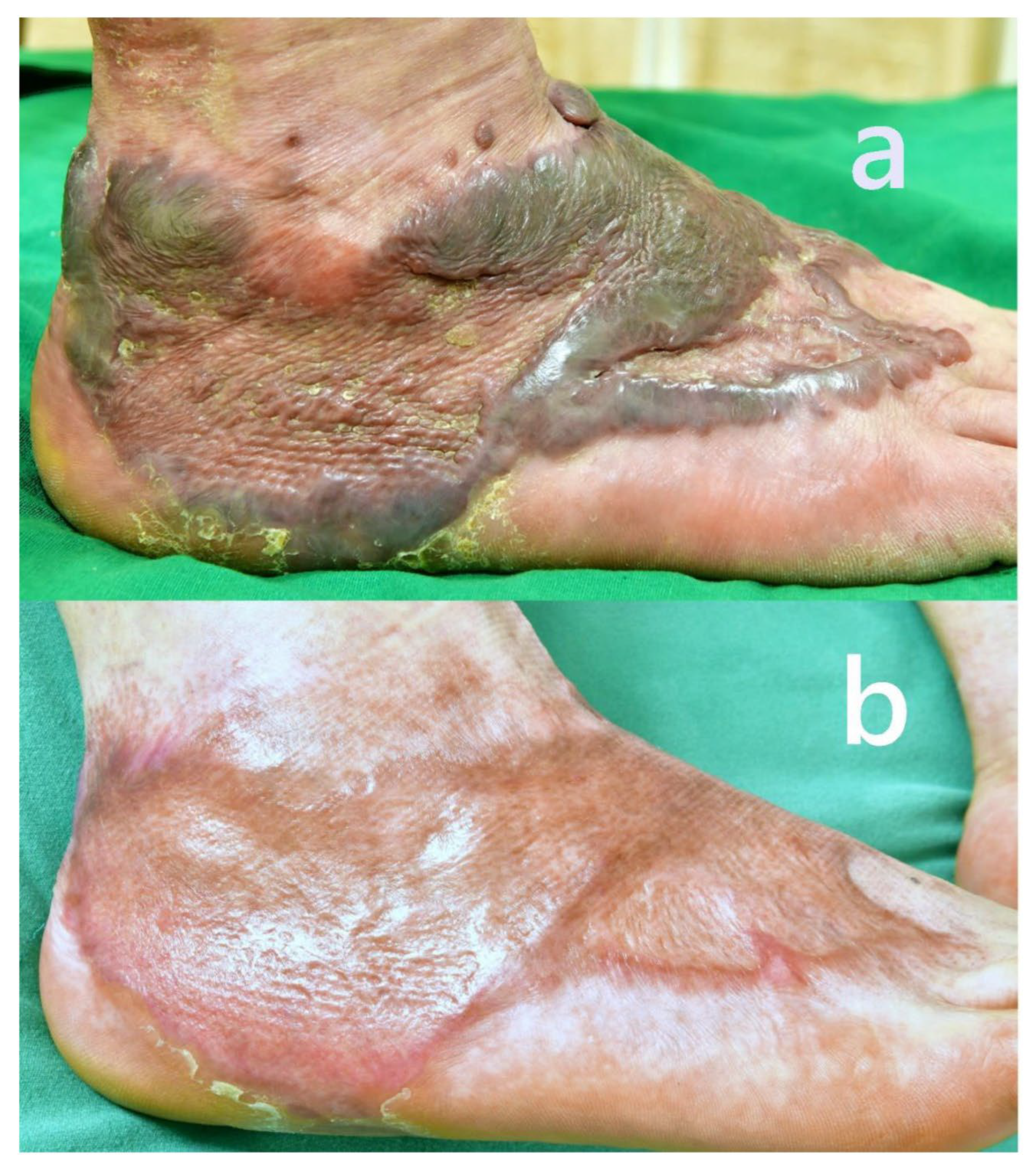

3.4. Case 4

A 17-year-old woman presented with a forearm skin graft performed 4 years prior, following a hot water burn sustained 7 years ago. The graft was characterized by mild hypertrophy, surface irregularity, dark brown pigmentation, and hypopigmented suture lines. She underwent seven Pinholxell sessions and seven fractional CO2 laser procedures. Additionally, three sessions of 1064 nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser were performed over a five-month period, concurrently with the fractional laser treatments.

The total treatment time was 3 years and 3 months.

The surface texture of the scar normalized significantly, with a marked reduction in rigidity and a more uniform appearance.

The hyperpigmented areas and keratotic features largely resolved, reflecting substantial improvement in both pigmentation and overall color uniformity.

Elevated, hypopigmented suture lines at the scar margins became less prominent and blended more seamlessly into adjacent tissue.

The reduced skin thickness alleviated wrist movement discomfort, improving flexibility.

The patient experienced no adverse events and expressed overall satisfaction with the results. Pre-, mid-, and post-treatment clinical images are provided in

Figure 6.

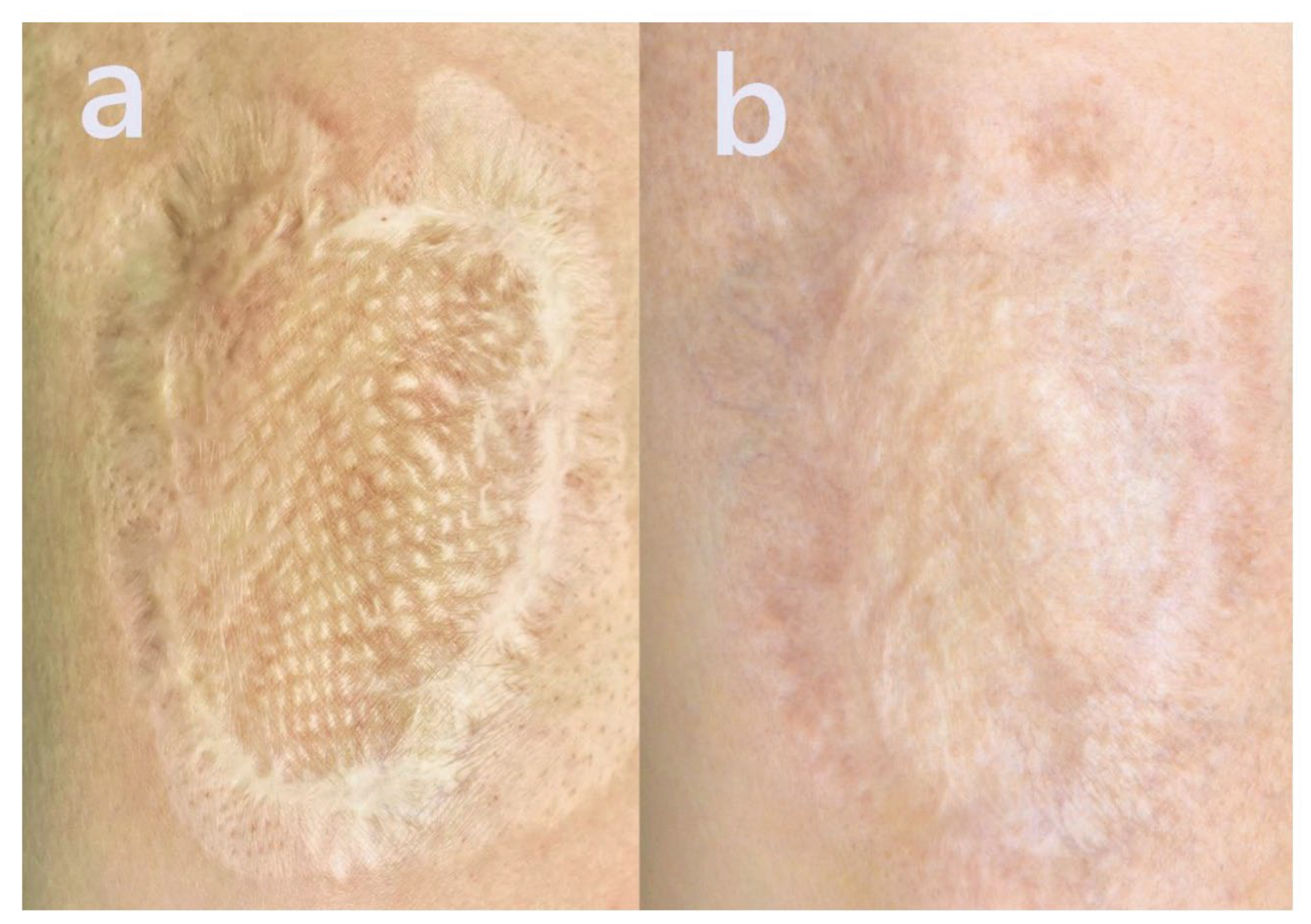

3.5. Case 5

A 60-year-old female patient presented with a large hypertrophic scar on the lower extremity, resulting from a childhood burn injury. During hospitalization in early childhood, a mesh-type split-thickness skin graft was applied. The grafted area exhibited significant textural irregularity, fibrosis, and visible mesh pattern remnants.

The total treatment time was 2 year.

Scar thickness and stiffness were markedly reduced, resulting in a significantly flatter and less fibrotic surface. Mesh-pattern ridges characteristic of split-thickness grafts became less visible, indicating dermal remodeling and integration with surrounding tissue.

The previously elevated and indurated texture softened, leading to smoother surface contours and improved tactile quality.

Scar color transitioned toward a more natural skin tone, demonstrating pigment normalization and better chromatic blending with adjacent skin.

Scar boundaries became less defined, suggesting successful contour integration and edge softening.

Overall cosmetic appearance improved, enhancing patient satisfaction and restoring a more natural visual skin landscape.

The patient underwent an uneventful two-year course of Pinholxell therapy with steady improvement. However, the treatment was concluded before full maturation of the scar, leaving some room for refinement. Additional fractional CO2 laser sessions may have further improved texture and brought the scar closer to normal skin quality.

Pre- and post-treatment clinical images are provided in

Figure 7.

4. Discussion

he Pinholxell method presents a novel and targeted approach to the treatment of hypertrophic and post-graft scars, leveraging the synergistic effects of two sequential CO

2 laser modalities. By first generating vertically oriented pinhole columns with a focused CO

2 laser and subsequently applying a fractional CO

2 laser overlay, this technique enables simultaneous deep dermal remodeling and superficial epidermal regeneration. Such a dual-action mechanism is designed to optimize scar remodeling outcomes while mitigating the risks commonly associated with more invasive or monomodal interventions [

9,

10,

11].

The results from the five presented cases highlight the clinical utility of the Pinholxell method in managing scars resulting from skin grafts. Skin graft scars often involve a combination of surface irregularity, color mismatch, stiffness, and underlying fibrotic changes that can interfere with both appearance and function, particularly when located near joints or visible areas [

1,

2]. The five representative cases demonstrate the adaptability and therapeutic potential of the Pinholxell method in addressing varied presentations of post-graft scarring. Treatment plans were supplemented and modified as needed based on individual scar morphology.

The pinhole method proposed by Lee et al. in 2015 (“pinhole method 4.0”) demonstrated notable improvements in hypertrophic burn scars [

6]. The pinhole columns are thought to disrupt irregular and dense collagen bundles while facilitating the uniform deposition of collagen and elastin. Furthermore, the spacing between columns minimizes the risk of overheating and excessive thermal injury, enhancing treatment safety and effectiveness [

6,

7]. Li et al. applied a CO

2 laser to split-thickness skin grafts in a porcine model and found that a combined dual-scan protocol, consisting of high fluence–low density and low fluence–high density settings, yielded the most significant improvements in scar thickness and pigmentation [

8]. This protocol bears similarity to the Pinholxell method in its delivery parameters and therapeutic intent.

In the current series, the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) total score improved from 8.12 ± 3.03 pre-treatment to 1.40 ± 1.08 post-treatment (mean difference 6.72), while the Observer Scar Assessment Scale (OSAS) total score improved from 19.74 ± 7.05 to 5.72 ± 2.27 (mean difference 14.02). All subdomains—including vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, height (VSS) and vascularity, pigmentation, thickness (OSAS)—demonstrated statistically significant improvements (p < 0.001), reflecting both objective and clinically meaningful scar remodeling.

Nonetheless, the scope of the findings is constrained by the limited sample size and retrospective design. All patients included in this case series were Fitzpatrick skin types III to V (Korean), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to populations with lighter or darker skin tones. Given the known differences in pigmentation response and the risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation among different skin types, further investigation is required to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the Pinholxell method across a broader range of phototypes. The absence of a control group further limits the ability to generalize the results. Future studies with larger cohorts and standardized assessment criteria are necessary to establish clinical guidelines and determine the reproducibility of these outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In this retrospective cohort of 25 patients with skin graft scars treated using the dual-step Pinholxell CO2 protocol, we observed significant improvements across all OSAS and VSS domains (paired t-tests, all P < .001). The OSAS total score decreased from 42.40 ± 10.75 to 12.76 ± 2.96 (mean difference 29.64; ≈70% reduction), and the VSS total decreased from 8.12 ± 3.03 to 1.40 ± 1.08 (mean difference 6.72; ≈83% reduction). Patients also reported relief of pruritus and pain, better texture and color, improved pliability, and reduced contracture-related functional limitation. Treatment was well tolerated, with no observed complications and high patient satisfaction. These findings support the Pinholxell method as a safe and effective option for the long-term management of graft-related scars. However, the retrospective, single-arm design limits causal inference; larger, multicentre prospective studies—ideally randomized—are needed to confirm efficacy, define optimal energy/density and treatment intervals, and assess durability across diverse skin phototypes.

Author Contributions

The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived due to the retrospective nature with written patient consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aleman Paredes, K.; Selaya Rojas, J.C.; Flores Valdés, J.R.; Castillo, J.L.; Montelongo Quevedo, M.; Mijangos Delgado, F.J.; de la Cruz Durán, H.A.; Nolasco Mendoza, C.L.; Nuñez Vazquez, E.J. A Comparative Analysis of the Outcomes of Various Graft Types in Burn Reconstruction Over the Past 24 Years: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e54277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, C.A.; MacNeil, S. The mechanism of skin graft contraction: An update on current research and potential future therapies. Burns 2008, 34, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, M.E.; Clairmonte, I.A.; DeBruler, D.M.; Blackstone, B.N.; Malara, M.M.; Supp, D.M.; Powell, H.M. FXCO2 therapy of existing burn scars in a porcine model. Burns Open 2019, 3, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wei, X. Intralesional triamcinolone for keloids/hypertrophic scars: Systematic review. Burns 2021, 47, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leszczynski, R.; da Silva, C.A.; Pinto, A.C.P.N.; Kuczynski, U.; da Silva, E.M. Laser therapy for treating hypertrophic and keloid scars. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 9, CD011642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Yeo, I.K.; Kang, J.M.; Chung, W.S.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, B.J.; Park, K.Y. Treatment of hypertrophic burn scars by combination laser-cision and pinhole method using a carbon dioxide laser. Lasers Surg. Med. 2014, 46, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whang, S.W.; Lee, K.-Y.; Bin Cho, S.; Lee, S.J.; Kang, J.M.; Kim, Y.K.; Nam, I.H.; Chung, K.Y. Burn scars treated by pinhole method using a carbon dioxide laser. J. Dermatol. 2006, 33, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ng, S.K.; Xi, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Su, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Dual-scan CO2 protocol in split-thickness graft contraction (red Duroc pig). Burns Trauma 2021, 9, tkab048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.; Bettiol, P.; Le, A.; MacKay, B.J.; Griswold, J.; McKee, D. CO2 resurfacing for scars of the hand/upper extremity. Scars Burn Heal. 2022, 8, 20595131211047694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klifto, K.M.; Asif, M.; Hultman, C.S. Laser management of hypertrophic burn scars: Review. Burns Trauma 2020, 8, tkz003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirakami, E.; Yamakawa, S.; Hayashida, K. Strategies to prevent hypertrophic scars: Molecular evidence. Burns Trauma 2020, 8, tkz004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poetschke, J.; Gauglitz, G.G. Hyperpigmented Scar. In Textbook on Scar Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 505–507. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).