1. Hemostatic System Evolution – Procoagulants and Anticoagulants Trend

Haemostasis in the newborn is a complex and dynamic system, that reflects in a difficult interpretation of the usually adopted coagulation tests; for this reason it represents a challenge for both clinicians and laboratory people. The aim of the present review is to examine the available evidence in this field, trying to give some suggestions about the correct performance and interpretation of the main coagulation tests.

1.1. Introduction: “Developmental Hemostasis”

Hemostasis is a complex phenomenon whose principal function is to mitigate the risk of excessive bleeding at sites of a vascular injury. This process can be classified into primary (adhesion, activation, and aggregation of platelets at a site of vessel injury), secondary (activation of coagulation factors resulting in the formation of covalently cross-linked fibrin that stabilizes the platelet plug), and tertiary hemostasis (fibrinolysis, activation of fibrinolytic pathway to dissolve the clot, restoring the physiological blood flow) [

1]. The hemostatic system of the newborn greatly differentiates from both older children and adults: the principal characteristic of the hemostatic system in newborns is that it is dynamically and rapidly evolving over the first weeks and months of life. The term “developmental hemostasis” was coined in 1987 by Andrew, who demonstrated the differences in plasma levels and activity of coagulation proteins and the gradual increase of these from preterm to mature newborns. [

2,

3] This term is still used to define the peculiarity of the hemostatic system to change and to mature from foetal life to childhood and adult life [

4].

Table 1 resumes the evolution of the hemostatic system components in the foetus and neonate.

1.2. Foetal Hemostasis

1.2.1. Foetal Primary Hemostasis

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) is early expressed in foetal life (4 weeks of gestation), reaching about 40% of adult levels at around 12-15 weeks of gestation; ultralarge multimers of VWF are found in foetal blood till 35 weeks of gestation, owing to a decreased cleavage activity by the metalloproteinase ADAMTS-13. Therefore, foetal VWF prompts enhanced platelet adhesion to sub endothelium in high shear flow conditions [

5]. Platelets can be detected in foetal plasma already at 11 weeks of gestation and they reach the normal adult range at around 20 weeks of gestation [

6] The expression of surface receptors is equivalent to adult platelets already at 12-16 weeks of gestation with the only exception of the epinephrine ones [

6].

1.2.2. Foetal Coagulation System

Coagulation proteins are independently synthesised by the foetus and do not cross the placenta [

7]. Most of them are early expressed in embryonic and foetal development: factor VIII and fibrinogen can be detected already at 4-8 weeks of gestation and they reach the normal adult range by midgestation, while factors VII, V and XIII show progressive development during gestation [

5,

8]. The vitamin K-dependent proteins, factors II, VII, IX, X, protein C and protein S show decreased concentrations during foetal maturation (existing a gradient for vitamin K across placenta that determines foetal levels of about 10% of maternal concentrations), ranging to from 10% to 20% of adult levels at midgestation [

5,

8]. Contact factors (factor XII, high molecular weight kininogen, prekallikrein) are present at low levels. Foetal fibrinogen shows a peculiar structure due to specific post-translational modifications: it is characterized by increased phosphorylation and sulfation that determine a decreased clot strength [

6].

1.2.3. Foetal Fibrynolisis

Fibrinolytic activity can be detected in foetal plasma at 10-11 weeks of gestation [

5]. In addition, plasminogen is present in a unique foetal form that contains increased concentrations of sialic acid, which confers a reduced tendency to activation [

6]. Plasmin from foetal plasminogen has less enzymatic activity compared to adult plasmin [

1].

1.3. Neonatal Hemostasis

1.3.1. Neonatal Primary Hemostasis

Levels of VWF ultralarge and high-molecular weight multimers as well as VWF collagen-binding activity are increased during the first 2 months of life and then gradually decrease to adult levels [

9]. Maturation to typical adult VWF multimeric patterns occurs over the first 3 months of neonatal life [

5]. Platelet count is reported to be similar in neonates and adults, with reduced expression of platelet surface receptors (GPIIbIIIa, GPVI) as measured by flow cytometry and gene expression analysis. This could explain neonatal platelet hyporeactivity as compared to adult platelets [

10]; however, through mass spectrometry no significant differences in the expression level of major glycoproteins were observed in neonates [

11]. It is to note that the results of all studies on neonatal platelet function could vary greatly according to the source of platelets: in fact, platelet aggregation measured using rotational thromboelastometry in cord blood was significantly higher than in peripheral blood meaning that a rapid change in platelet function occurs during the first days of life after birth [

12].

1.3.2. Neonatal Coagulation

Postnatal levels of vitamin K-dependent factors (factors II, VII, IX, X, protein C and protein S) are significantly reduced as compared to adult ones: factor IX completes its maturation at about 9-12 months (making difficult the diagnosis of moderate and mild forms of Hemophilia B) [

5]. In the absence of postnatal vitamin K administration, a small quote of neonates will manifest clinically significative bleeding related to the absence of vitamin K-dependent factors, with a very low incidence of life-threatening hemorrhages (intracranial, gastrointestinal) [

5]. The levels of contact factors (factor XII, high molecular weight kininogen, prekallikrein) gradually increase to approach adult levels by 6 months of life [

7]. Plasma levels of fibrinogen, factor V and factor XIII are already within the normal adult range at birth [

7]; VWF and Factor VIII can be normal or increased [

2]. Levels of anticoagulants are reduced at birth compared to adults: antithrombin and protein C are about 50% of adult levels [

1]; protein C is present in a fetal form (that is functionally active), increasing slowly to reach adult values by 13-14 years of age [

1]. Protein S level is reduced at birth but its activity is conserved, being present mainly in a free form because of the absence of C4b-binding protein [

1]. Free TFPI levels are reduced (50–60% of adult values) [

1].

1.3.3. Neonatal Fibrinolysis

Neonates show an increased fibrinolytic activity: tPA has increased activity as compared to adults, although plasminogen levels are about 50% of adult levels at birth and rise to the normal adult range by 6 months of age [

1].

1.4. Hemostasis of the Healthy Pre-Term Neonate

World Health Organization (WHO) defines preterm neonates those babies born alive before the completion of the 37th week of gestational age (GA) [

13]. The estimated rate of preterm birth is 4-16% across different countries. Few studies analysed the levels of coagulation factors in premature infants. Andrew et al in 1988 studied 137 healthy preterm infants aged 30-36 weeks [

3] and reported that vitamin K-dependent factors, protein C, protein S, antithrombin and contact factors are <50% of adult levels, except from factor VII (67% of adult levels), factor VIII and VWF are near or above adult values. More recently, Poralla et al analysed extremely preterm infants (from 23 to 27 weeks of GA) [

14] and reported that factors VII and X rise with increasing GA, whereas fibrinogen and factors II, V and VIII remain rather stable. Another study by Hochart et al [

15] reported that fibrinogen, factor II and factor V rise with GA. Platelets from preterm neonates have reduced GPIIbIIIa activation, reduced fibrinogen binding and degranulation, resulting in a decreased platelet function compared to platelets from term neonates [

10]. Also in this setting, platelet source (i.e., cord or peripheral blood) may impact on final results.

2. Pre-Analytical Variables: Haematocrit Role

In neonates, high haematocrit (Hct) may be associated with conditions like dehydration, polycythemia, or certain physiological adaptations after birth (asphyxia, e.g.). It is critical to understand to which extent high haematocrit can influence laboratory results, particularly in coagulation studies, to avoid diagnostic errors. High haematocrit levels in neonates can have significant implications for coagulation testing, potentially leading to inaccurate or misleading results and particularly due to their impact on the balance between citrate anticoagulant and ionized calcium in the blood sample [

16]. Haematocrit refers to the percentage of blood volume occupied by red blood cells (RBCs), and when it exceeds 55%, the reduced plasma volume in the sample leads to a lower concentration of ionized calcium. This, in turn, can impair clotting tests such as prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), potentially causing falsely prolonged results. The altered anticoagulant-to-plasma ratio in such samples mimics the effect of underfilled tubes, where the anticoagulant disproportionately affects the plasma, leading to inaccurate test outcomes [

17]. To mitigate this, guidelines from organizations such as the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommend adjusting the citrate-to-blood ratio in samples with haematocrit values above 55%. Specific formulas have been developed to guide this adjustment, ensuring accurate coagulation results even in patients with high haematocrit. The formula is:

where C is the volume of citrate in the tube, Hct is the patient’s hematocrit, V is the blood amount to be collected, and 1.85

× 10

−3 is a constant [

18]. However, this issue is less of a concern in cases of severe anaemia, where the increased plasma volume allows for sufficient calcium to remain available, thus preventing clotting interference [

19]. Therefore, proper adjustment of the anticoagulant is critical in neonates and others with high haematocrit to avoid diagnostic inaccuracies in coagulation testing.

3. The Dynamic Hemostatic System of the Newborn and Its Effect on Laboratory Tests

The developmental hemostatic changes in the functional level of the coagulation proteins lead to several challenges for the clinician to correctly diagnose a child with a coagulation disorder and to choose and monitor anticoagulant therapy [

20,

21,

22]. Coagulation laboratory tests should be carefully interpreted due to the highly heterogeneous ranges between neonates compared with children and adult subjects. Andrew et al., for the first time, introduced the reference ranges for healthy neonates over 30 years ago [

23]. After that, several authors have tried to define the reference standards in children, even by using updated reagents and emerging technique with automated systems [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Besides the complexity in interpreting the results, there are also challenges in pre-analytical phase and analytical phase (e.g. difficulties in venipuncture, the absence of a free-flowing blood sample that can result in falsely prolonged PT and APTT) [

28]. Furthermore, the newborn and infant population in these studies has been quite small, preventing the possibility to draw definite conclusions. The screening coagulation tests, APTT and PT, are usually prolonged as compared with the adult normal range even when reported in ratio with a normal plasma (that usually is an adult plasma) [

20].

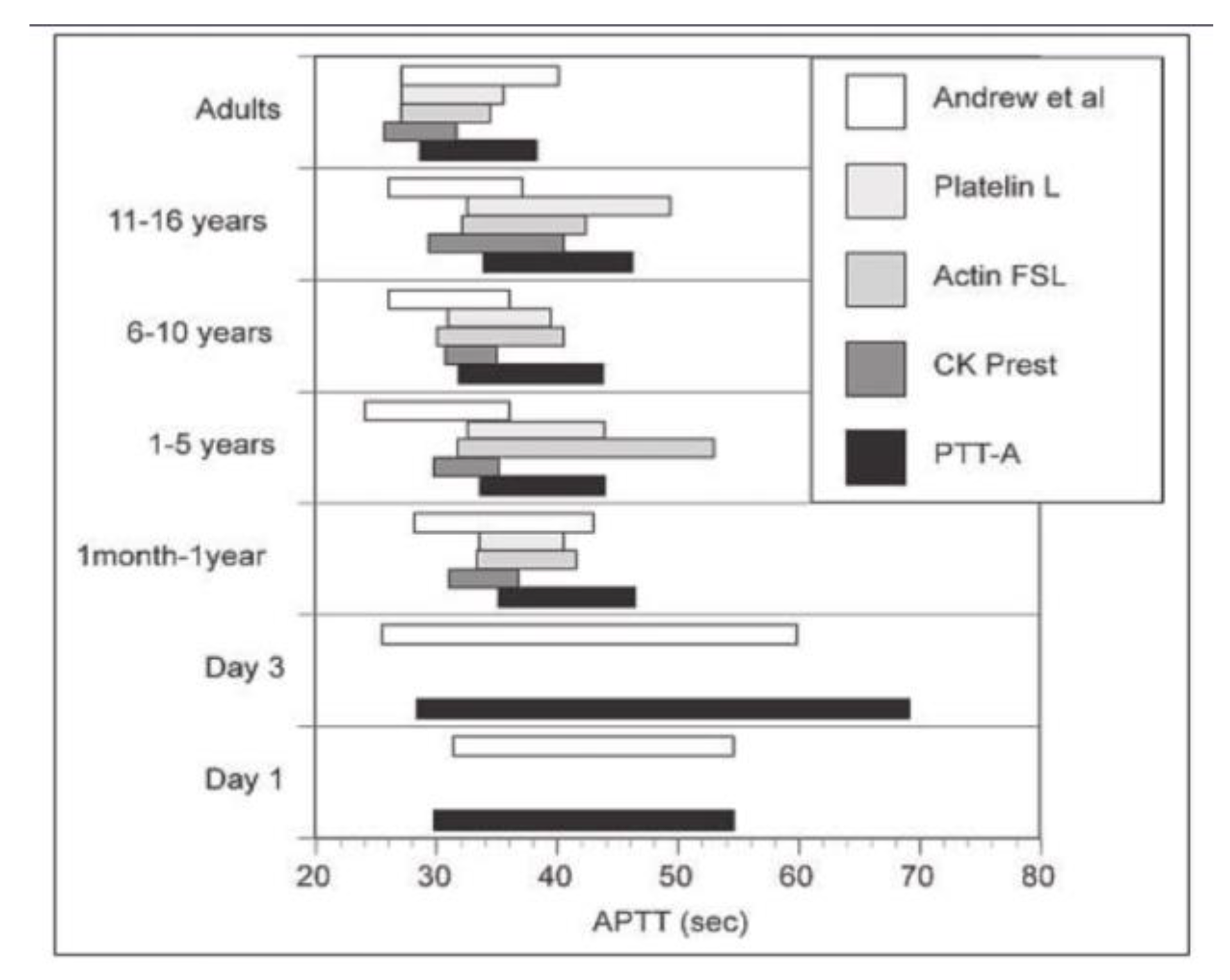

29Furthermore, reference ranges for APTTs will differ with each different reagent and analyzer system, often significantly. Foetal reference ranges for coagulation parameters were studied for different gestational age-groups, and the median test results were between 10% and 30% of adult values, depending on the evaluated parameter, in fetuses between 19 and 23 weeks of gestation and progressively increased to levels between 10% and 50% in fetuses between 30 and 38 weeks of gestation [

29]. Unfortunately, the laboratory reference ranges must be interpreted with caution due to the significant laboratory variability of reagents and instruments used as showed by Monagle in 2006 (

Figure 1). In 2012, The Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) published recommendations for children, specifying that hemostasis laboratories must use population-, reagent-, and analyzer-specific reference ranges [

30]. The only truly valid reference range would be an age-matched range specific to the reagents and instruments used. It seems impossible to ask each laboratory to establish its own references intervals for all coagulation parameters in its own technical conditions [

30]. These laboratory reference standars should be obtained only by specific, multicenter studies carried out using the new reagents/analyzers combinations.

4. Sensitivity of Reagents to Absolute and Relative Factor Deficiencies

The haemostatic system is not fully developed until 3-6 months of age; therefore, differences between adults and infants are not always pathological and may be physiological [

32]. The routine use of laboratory tests in neonates is often called into question for several reasons: firstly, reagents are not standardized for this age group; secondly, there are practical issues such as problems with blood sampling and the volume of blood required for a complete test; and, thirdly, there is a lack of information on how to interpret the results [

33].

Different reference intervals for coagulation tests should be used for adult and paediatric patients to avoid misdiagnosis, which can have serious consequences for patients and their families [

32]. The ISTH also recommends that each laboratory defines the age-dependent reference ranges under its own technical conditions [

34]. A reference interval established using the same analyzer and reagent systems (after a validation process) should be used by laboratories that are unable to establish their own reference intervals ex novo. In this setting, the population variance should also be considered (including population-specific variance, reagent-specific variance, and analyzer-specific variance). If there is no reference interval value for the analyzer/reagent combination used in that laboratory, great care should be taken in the interpretation of coagulation test results in children; therefore, each laboratory should establish its own reference interval for healthy populations in appropriate age groups [

32]. Not all PT and APTT reagents are equally sensitive to the reduction of coagulation factors; as shown by Toulon et al., APTT reagents show varying sensitivities to deficiencies of different coagulating factors. This is thought to be due to differences in the type and concentration of activator or phospholipids used in the reagent [

35]. Moreover, international standardization of APTT reagents is not available [

36].

5. Viscoelastic Coagulation Test in Newborns

Viscoelastic coagulation tests (VCT), such as Thromboelastography (TEG)/Rotational Thromboelastometry (ROTEM) are used as point-of-care devices that provide information on clot formation and lysis, allowing the entire haemostatic process to be monitored. According to the cellular model of coagulation, the complex process of haemostasis with the interactions between procoagulant factors, fibrinolytic proteins, cellular components and platelets can be analysed globally. The main advantage of VCTs compared to conventional tests is their ability to assess the patient's haemostatic state numerically and graphically in real time. They also require a small blood sample, which is very useful in the neonatal setting [

37]. Similarly to what happens for conventional coagulation tests, VCT parameters are also affected by Hct levels: a “hypocoagulable” profile, expressed as prolonged CT (clotting time) and CFT (clot formation time) in INTEM/EXTEM assays and reduced A5 (clot strength at 5 minutes) in INTEM/FIBTEM assays, was observed in neonates with higher hematocrit levels [

38,

39]; on the other hand the impact of low hematocrit in patients with anemia should be considered as a possible cause of “hypercoagulability” in ROTEM test results [

40]. During fetal growth there is an increased synthesis of procoagulant and anticoagulant factors, especially after 34 weeks of gestation, which is often not complete at the time of birth. PT and APTT are often altered due to vitamin K deficiency. However, these tests do not detect a concomitant deficiency of coagulation inhibitors. The use of viscoelastic tests may be useful in the assessment of global coagulation status in these patients [

33]. The use of VCT in newborns has increased in recent years. However, it is limited by the lack of reference values for newborns. Differences between infants and adults have been reported in some studies. An observational study was conducted by Amelio and colleagues to identify non-coagulopathic term and late preterm infants admitted to a III level Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) with a VCM test in the first 72 hours of life. The authors found that clotting time (CT) was significantly associated with PT but not APTT. They noted some differences with adults, especially for a shorter CT and CFT (clotting time) and higher alpha A10, A20 and L130 than adults, the Maximum Clot Firmness (MCF) and L145. They concluded that neonates have a shorter time than adults to reach a significant clot, with 25% of neonates having an alpha angle above the upper reference limit. However, compared with adults, there are no significant differences in the late parameters of clot strength and fibrinolysis (MCF and L145) [

41]. The umbilical cord blood seems to be an inadequate sample for VCT, as demonstrated by Raffaelli et al. They found a procoagulant imbalance in the placental blood compared to the venous counterpart of the infant [

42]. Sokou et al compared 198 full-term and 84 preterm newborns to look for differences.

Figure 2 shows that there were no significant differences in ROTEM values between preterm and term infants, except for LI60. This could be due to lower levels of fibrinolysis inhibitors in preterm infants

.[

43].

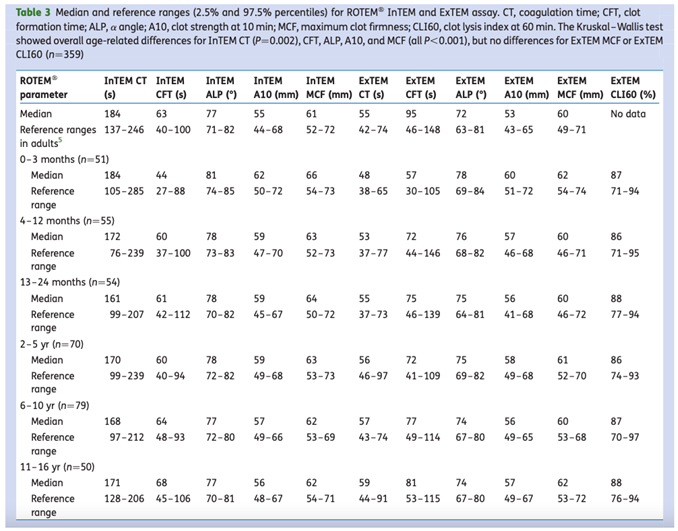

As with many other parameters, neonatal reference ranges are difficult to find. Oswald et al. presented age-specific reference values for ROTEM. They found that coagulation initiation and clot formation are directly related to age, whereas clot strength and fibrinolysis are similar across age groups. The ROTEM parameters of infants aged 0-3 months showed an accelerated induction of coagulation with clot firmness within the normal limits for adults, as shown in

Table 2.

A recent review by Manzoni et al. [

45] confirms the importance of viscoelastic tests as valuable tools to identify an acquired coagulopathy in high-risk neonates and to allow a prompt targeted optimization of blood products and anticoagulation therapy; thromboelastography can optimize fresh-frozen plasma transfusion in surgical neonates [

46]. In conclusion, viscoelastic tests have been used in the neonatal setting, especially in the NICU, and could help clinicians to understand the in vivo haemostatic conditions of the newborn. Nevertheless, until now there are no specific neonatal guidelines and standardised reference values and this limitation doesn't allow to use this test as a gold standard method for evaluation of neonatal coagulation [

44].

6. Conclusions

The evaluation of the real haemostatic competence of a newborn candidate to an invasive or surgical procedure and presents with prolonged coagulation screening tests is a challenging and demanding situation for those who must manage such patients. Few hospitals have established normal ranges of coagulation tests for the neonatal period and an expert in neonatal and pediatric haemostasis is not always available. Clotting factor measurements are not everywhere and always available, while neonatal emergencies can occur in any hospital and at any time. Furthermore, hematocrit can constitute an important cause of preanalytical alteration. Besides, it is a current practice to administer thawed whole plasma to correct the apparent coagulopathy of the newborn before surgery, however this strategy is not free from risks such as allergic reactions, infections, volume overload, incompatibility reactions, fever, and complications due to citrate which is commonly contained in the bags. Global coagulation tests carried out with viscoelastic methods, which are increasingly widespread especially in intensive care units and operating theatres, can help the clinician to quickly evaluate the hemostatic situation of neonates and infants also providing information on platelet function even if these tests are prone, when carried out on citrated blood, to the interference of the hematocrit. However, viscoelastic tests lack adequate standardization, especially in the neonatal age, and adequate studies are needed to demonstrate their ability to reveal mild coagulopathies, which in the neonate can be difficult to identify with conventional screening tests.

Author’s contribution

A.C.M., C.G., T.M. and A.F. ideated the manuscript. C.G., T.M., A.F., G.A., G.C., A.I., M.L., N.P., M.S. and A.S. wrote the manuscript. A.C.M. supervised the writing. M.E.M. and R.C.S. corrected the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VWF |

Von Willebrand Factor |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| GA |

Gestational Age |

| HCT |

Hematocrit |

| PT |

Prothrombin Time |

| APTT |

partial thromboplastin time |

| RBCs |

Red Blood Cells |

| CLSI |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| ISTH |

The Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis |

| VCT |

Viscoelastic Coagulation Tests |

| TEG |

Thromboelastography |

| ROTEM |

Rotational Thromboelastometry |

| CT |

Clotting Time |

| CFT |

Clot Formation Time |

| NICU |

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

References

- Saracco P, Rivers RPA. Pathophysiology of Coagulation and Deficiencies of Coagulation Factors in Newborn. In: Neonatology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 1431–53.

- Andrew M, Paes B, Milner R, Johnston M, Mitchell L, Tollefsen DM, et al. Development of the human coagulation system in the full-term infant. Blood. 1987 Jul;70(1):165–72.

- Andrew M, Paes B, Milner R, Johnston M, Mitchell L, Tollefsen DM, et al. Development of the human coagulation system in the healthy premature infant. Blood. 1988 Nov;72(5):1651–7.

- Toulon P. Developmental hemostasis: laboratory and clinical implications. Int J Lab Hematol. 2016 May 17;38(S1):66–77.

- Manco-Johnson, MJ. Development of hemostasis in the fetus. Thromb Res. 2005 Feb;115 Suppl 1:55–63.

- Warren BB, Moyer GC, Manco-Johnson MJ. Hemostasis in the Pregnant Woman, the Placenta, the Fetus, and the Newborn Infant. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023 Jun 7;49(04):319–29.

- Monagle P, Massicotte P. Developmental haemostasis: Secondary haemostasis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011 Dec;16(6):294–300.

- Manco-Johnson, MJ. Development of hemostasis in the fetus and neonate. Thrombosis Research, Volume 119, S4 - S5.

- Developmental Hemostasis: Pro- and Anticoagulant Systems during Childhood. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29(4):329–38.

- Van Den Helm S, McCafferty C, Letunica N, Chau KY, Monagle P, Ignjatovic V. Platelet function in neonates and children. Thromb Res. 2023 Nov;231:236–46.

- Stokhuijzen E, Koornneef JM, Nota B, van den Eshof BL, van Alphen FPJ, van den Biggelaar M, et al. Differences between Platelets Derived from Neonatal Cord Blood and Adult Peripheral Blood Assessed by Mass Spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2017 Oct 6;16(10):3567–75.

- Grevsen AK, Hviid CVB, Hansen AK, Hvas AM. Platelet count and function in umbilical cord blood versus peripheral blood in term neonates. Platelets. 2021 Jul 4;32(5):626–32.

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth.

- Poralla C, Traut C, Hertfelder HJ, Oldenburg J, Bartmann P, Heep A. The coagulation system of extremely preterm infants: influence of perinatal risk factors on coagulation. Journal of Perinatology. 2012 Nov 8;32(11):869–73.

- Hochart A, Nuytten A, Pierache A, Bauters A, Rauch A, Wibaut B, et al. Hemostatic profile of infants with spontaneous prematurity: can we predict intraventricular hemorrhage development? Ital J Pediatr. 2019 Dec 28;45(1):113.

- Kitchen S, Adcock DM, Dauer R, Kristoffersen AH, Lippi G, Mackie I, et al. International Council for Standardisation in Haematology (ICSH) recommendations for collection of blood samples for coagulation testing. Int J Lab Hematol [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Nov 5];43(4):571–80. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34097805/.

- Marlar RA, Potts RM, Marlar AA. Effect on routine and special coagulation testing values of citrate anticoagulant adjustment in patients with high hematocrit values. Am J Clin Pathol [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2024 Nov 5];126(3):400–5. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16880137/.

- CLSI H21-A5 - Collection, Transport, and Processing of Blood Specimens for Testing Plasma-Based Coagulation Assays and Molecular Hemostasis Assays; Approved Guideline-Fifth Edition [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Available online: https://webstore.ansi.org/standards/clsi/clsih21a5?srsltid=AfmBOoqKconVXAchwBNfs7V5zdQM6_AyhicoI0u0L0KJ88tpb0J0mpYN.

- Siegel JE, Swami VK, Glenn P, Peterson P. Effect (or lack of it) of severe anemia on PT and APTT results. Am J Clin Pathol [Internet]. 1998 [cited 2024 Nov 5];110(1):106–10. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9661929/.

- Jaffray J YG. Developmental hemostasis: clinical implications from the fetus to the adolescent. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013 Dec;60(6):1407-17. [CrossRef]

- Ignjatovic V IAMP. Evidence for age-related differences in human fibrinogen. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2011 Mar;22(2):110-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi G, FMMM; et al. Coagulation testing in pediatric patients: the young are not just miniature adults. Semin Thromb Hemost 2007;33:816–20.

- AndrewM, PMR; et al. Development of the human coagulation system in the full-term infant.. Blood 1978;70:165–72.

- Monagle P, BCIV; et al. Developmental haemostasis. Impact for clinical haemostasis laboratories.. Thromb Haemost 2006;95:362–72.

- Toulon P BMBF ̧ois, M; et al. Age dependency for coagulation parameters in paediatric populations. Results of a multicentre study aimed at defining the age-specific reference ranges.. Thromb Haemost 2016;116:9–16.

- Attard C van der, STKV; et al. Developmental hemostasis: age- specific differences in the levels of hemostatic proteins. J Thromb Haemost 2013;11:1850–4.

- Appel IM, GBGJ; et al. Age dependency of coagulation parameters during childhood and puberty. J Thromb Haemost 2012;10:2254–63.

- Monagle P IVSH. Hemostasis in neonates and children: pitfalls and dilemmas.. Blood Rev 2010;24:63–8.

- Reverdiau-Moalic P DBBGBPLJGY. Evolution of blood coagulation activators and inhibitors in the healthy human fetus.. Blood 1996;88:900–6.

- Ignjatovic V KGMP. Perinatal and Paediatric Haemostasis Subcommittee of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Developmental hemostasis: recommendations for laboratories reporting pediatric samples.. J Thromb Haemost 2012;10:298e300.

- Monagle P, Barnes C, Ignjatovic V, Furmedge J, Newall F, Chan A, et al. Developmental haemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 2006 Nov 28;95(02):362–72.

- Di Felice G, Vidali M, Parisi G, Pezzi S, Di Pede A, Deidda G, et al. Reference Intervals for Coagulation Parameters in Developmental Hemostasis from Infancy to Adolescence. Diagnostics. 2022 Oct 1;12(10).

- Sokou R, Parastatidou S, Konstantinidi A, Tsantes AG, Iacovidou N, Piovani D, et al. Contemporary tools for evaluation of hemostasis in neonates. Where are we and where are we headed? Blood Rev. 2024 Mar 1;64:101157.

- Ignjatovic V, Kenet G, Monagle P, behalf of the perinatal O, haemostasis subcommittee of the scientific paediatric, committee of the international society on thrombosis standardization. Developmental hemostasis: recommendations for laboratories reporting pediatric samples. 2011.

- Toulon P, Eloit Y, Smahi M, Sigaud C, Jambou D, Fischer F, et al. In vitro sensitivity of different activated partial thromboplastin time reagents to mild clotting factor deficiencies. Int J Lab Hematol. 2016 Aug 1;38(4):389–96.

- Marlar RA, Strandberg K, Shima M, Adcock DM. Clinical utility and impact of the use of the chromogenic vs. one-stage factor activity assays in haemophilia A and B. Eur J Haematol [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Aug 31];104(1):3–14. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31606899/.

- Wikkelsø A, Wetterslev J, Møller AM, Afshari A. Thromboelastography (TEG) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM) to monitor haemostatic treatment versus usual care in adults or children with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2016 Aug 22 [cited 2024 Sep 4];2016(8). Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27552162/.

- Theodoraki M, Sokou R, Valsami S, Iliodromiti Z, Pouliakis A, Parastatidou S, et al. Reference Values of Thrombolastometry Parameters in Healthy Term Neonates. Children. 2020 Nov 26;7(12):259.

- Westbury SK, Lee K, Reilly-Stitt C, Tulloh R, Mumford AD. High haematocrit in cyanotic congenital heart disease affects how fibrinogen activity is determined by rotational thromboelastometry. Thromb Res. 2013 Aug;132(2):e145–51.

- Özdemir ZC, Düzenli Kar Y, Gündüz E, Turhan AB, Bör Ö. Evaluation of hypercoagulability with rotational thromboelastometry in children with iron deficiency anemia. Hematology. 2018 Oct 21;23(9):664–8.

- Amelio GS, Raffaeli G, Amodeo I, Gulden S, Cortesi V, Manzoni F, et al. Hemostatic Evaluation With Viscoelastic Coagulation Monitor: A Nicu Experience. Front Pediatr [Internet]. 2022 May 10 [cited 2024 Sep 4];10. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35620150/.

- Raffaeli G, Tripodi A, Manzoni F, Scalambrino E, Pesenti N, Amodeo I, et al. Is placental blood a reliable source for the evaluation of neonatal hemostasis at birth? Transfusion (Paris) [Internet]. 2020 May 1 [cited 2024 Sep 4];60(5):1069–77. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32315090/.

- Sokou R, Foudoulaki-Paparizos L, Lytras T, Konstantinidi A, Theodoraki M, Lambadaridis I, et al. Reference ranges of thromboelastometry in healthy full-term and pre-term neonates. Clin Chem Lab Med [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Sep 4];55(10):1592–7. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28306521/.

- Oswald E, Stalzer B, Heitz E, Weiss M, Schmugge M, Strasak A, et al. Thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) in children: age-related reference ranges and correlations with standard coagulation tests. Br J Anaesth. 2010 Dec;105(6):827–35.

- Manzoni F, Raymo L, Bronzoni VC, Tomaselli A, Ghirardello S, Fumagalli M, et al. The value of thromboelastography to neonatology. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2025 Mar;30(1):101610.

- Raffaeli G, Pesenti N, Cavallaro G, Cortesi V, Manzoni F, Amelio GS, et al. Optimizing fresh-frozen plasma transfusion in surgical neonates through thromboelastography: a quality improvement study. Eur J Pediatr. 2022 May 24;181(5):2173–82.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).