Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Testing Material

2.2. Synthesis of the Inhibitor

2.3. Working Electrolyte

2.4. Electrochemical Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Analysis of the Inhibitor

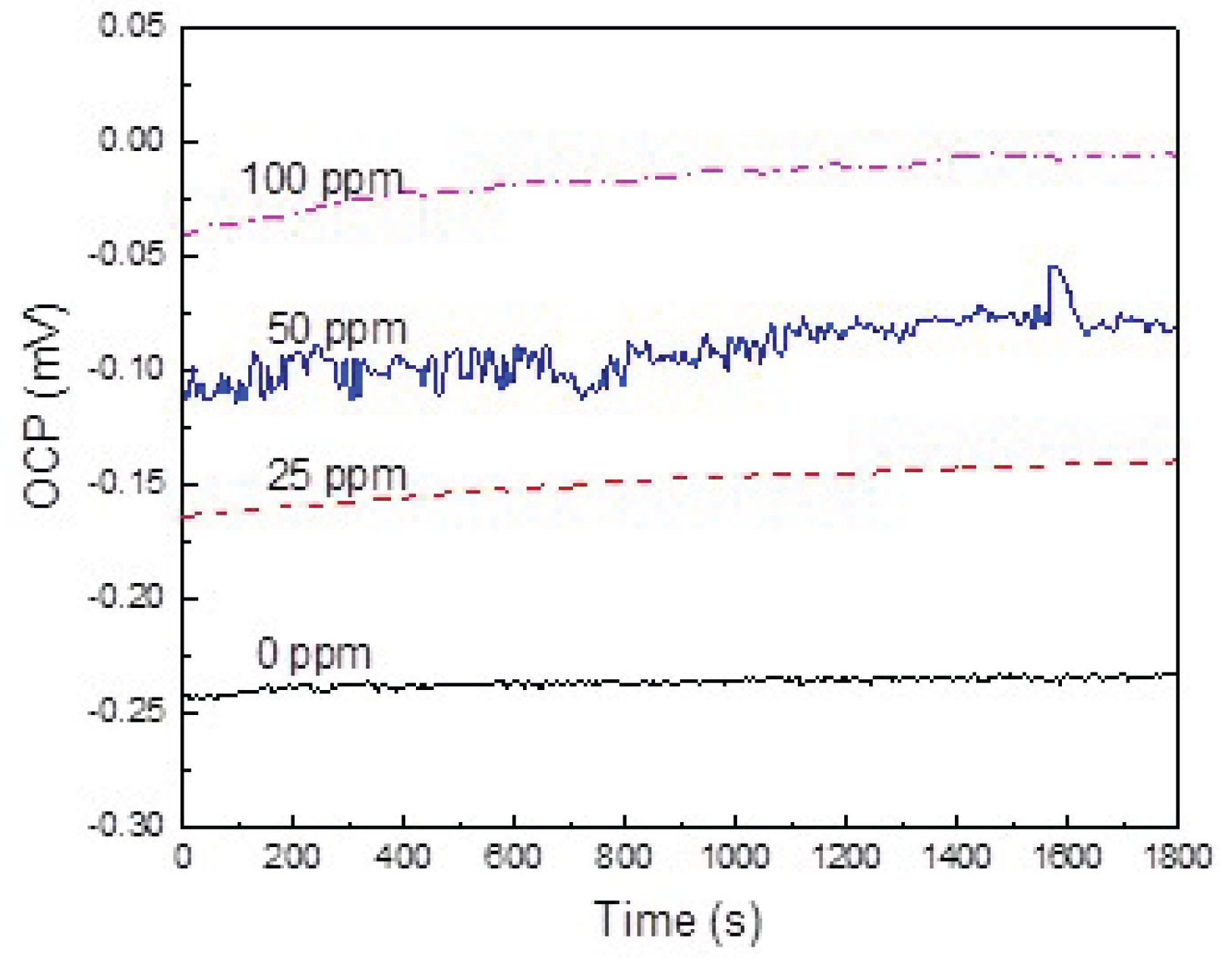

3.2. Open Circuit Potential

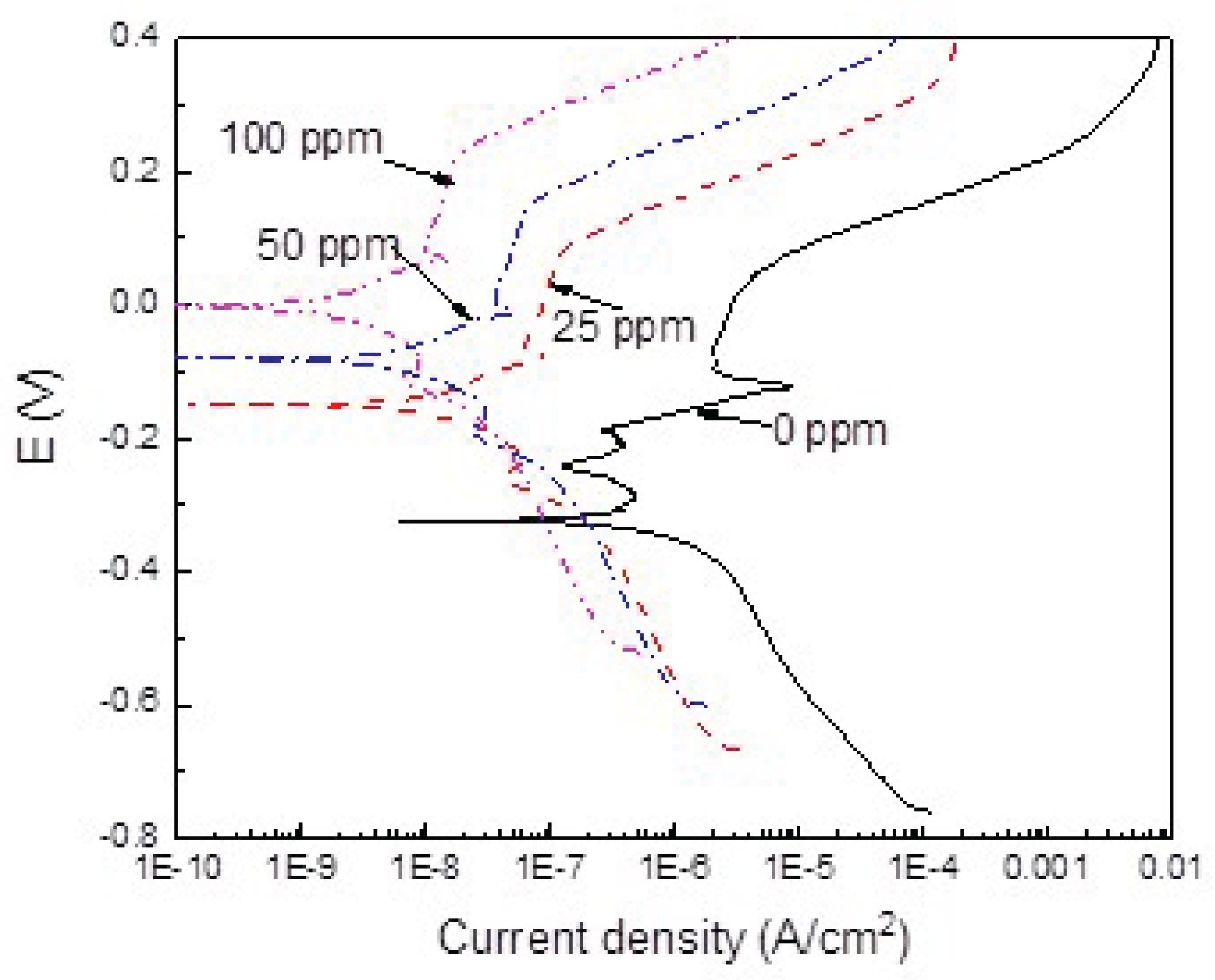

3.3. Potentiodynamic Polarization Curves

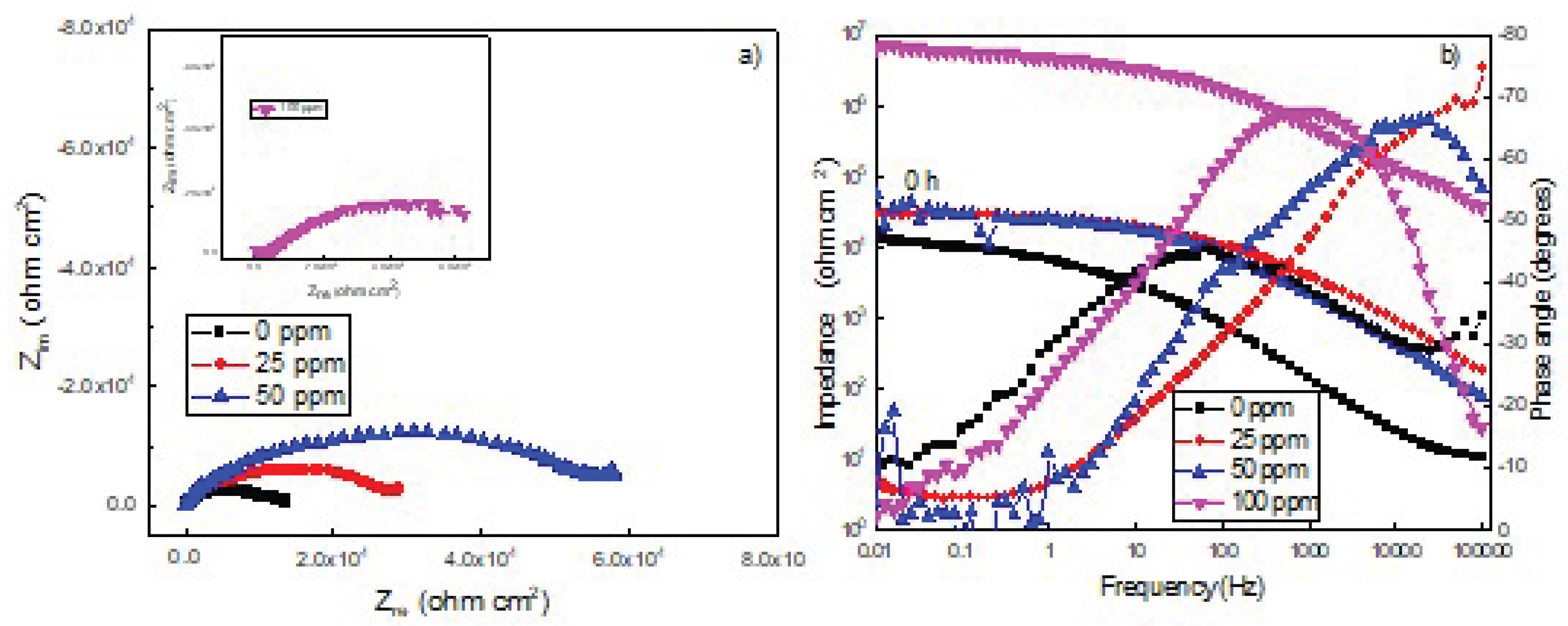

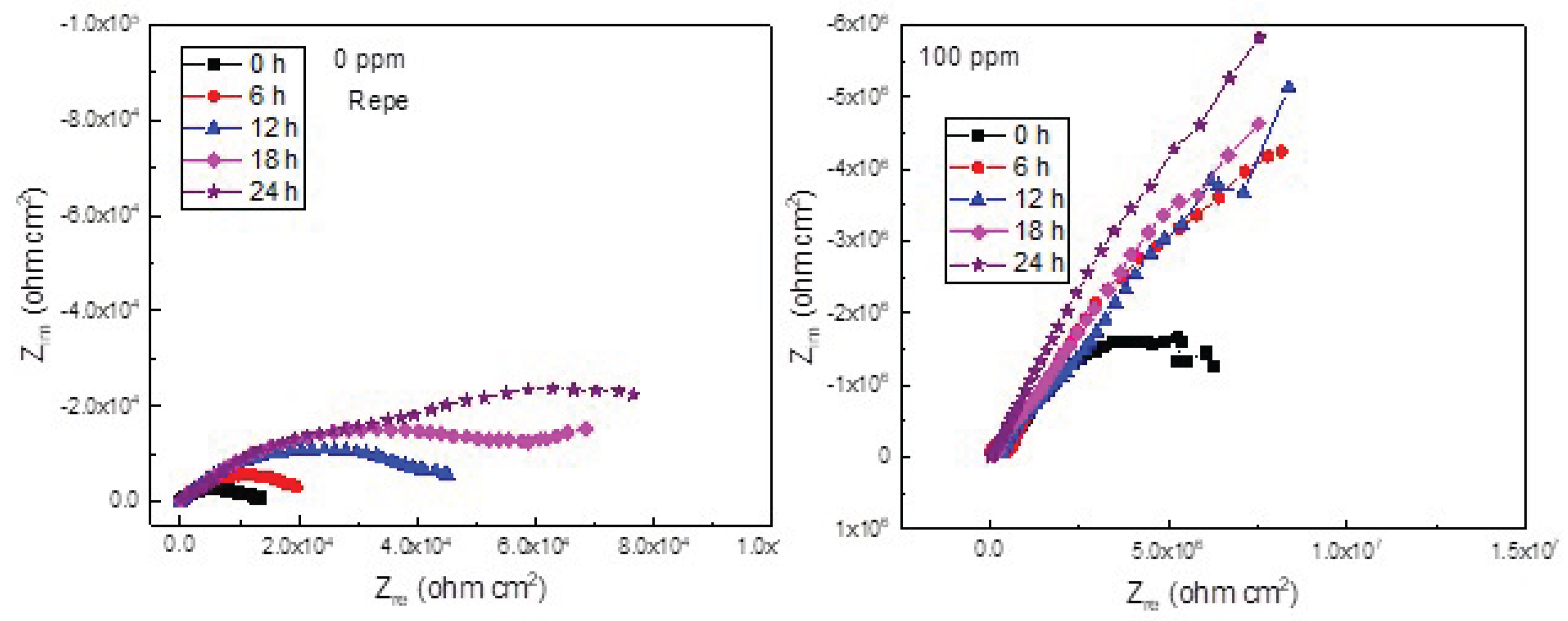

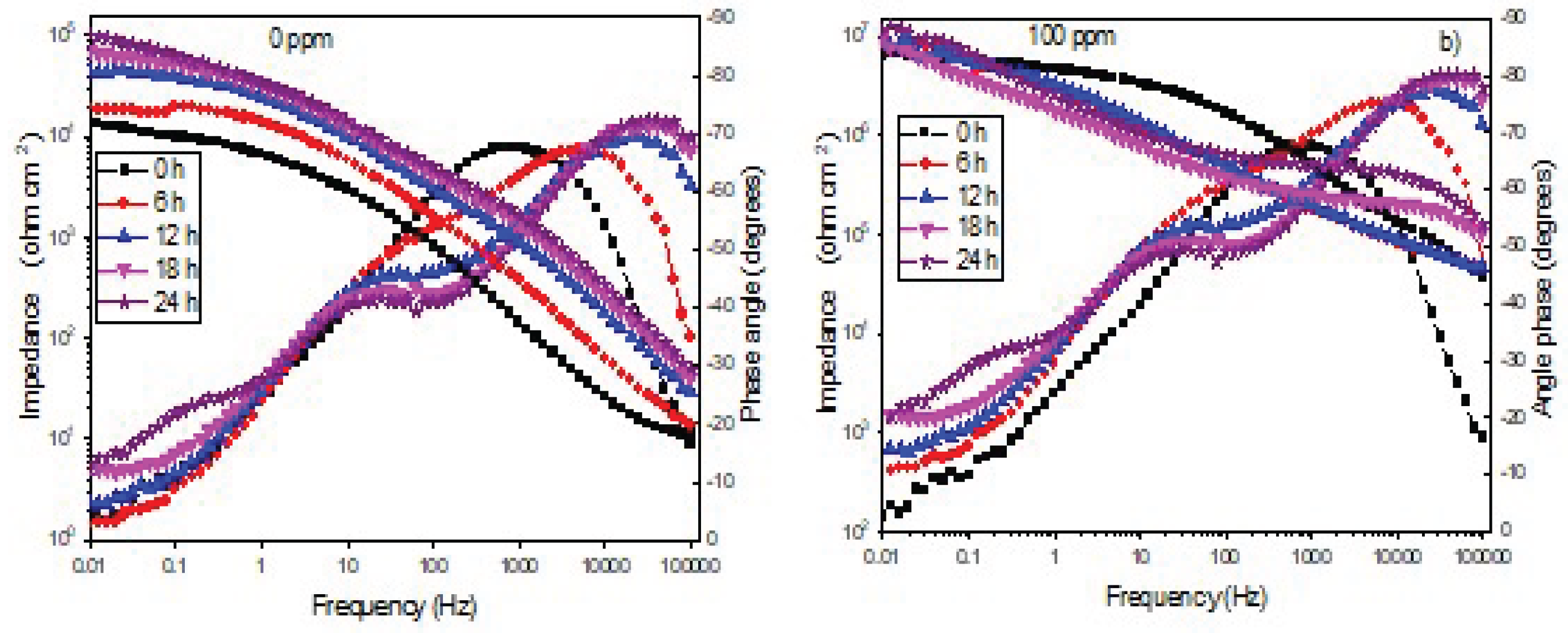

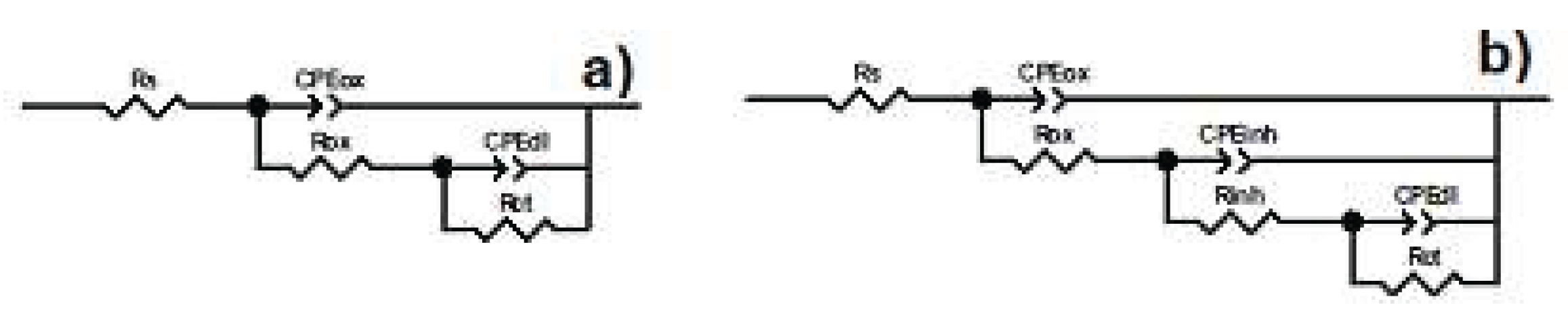

3.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Tests (EIS)

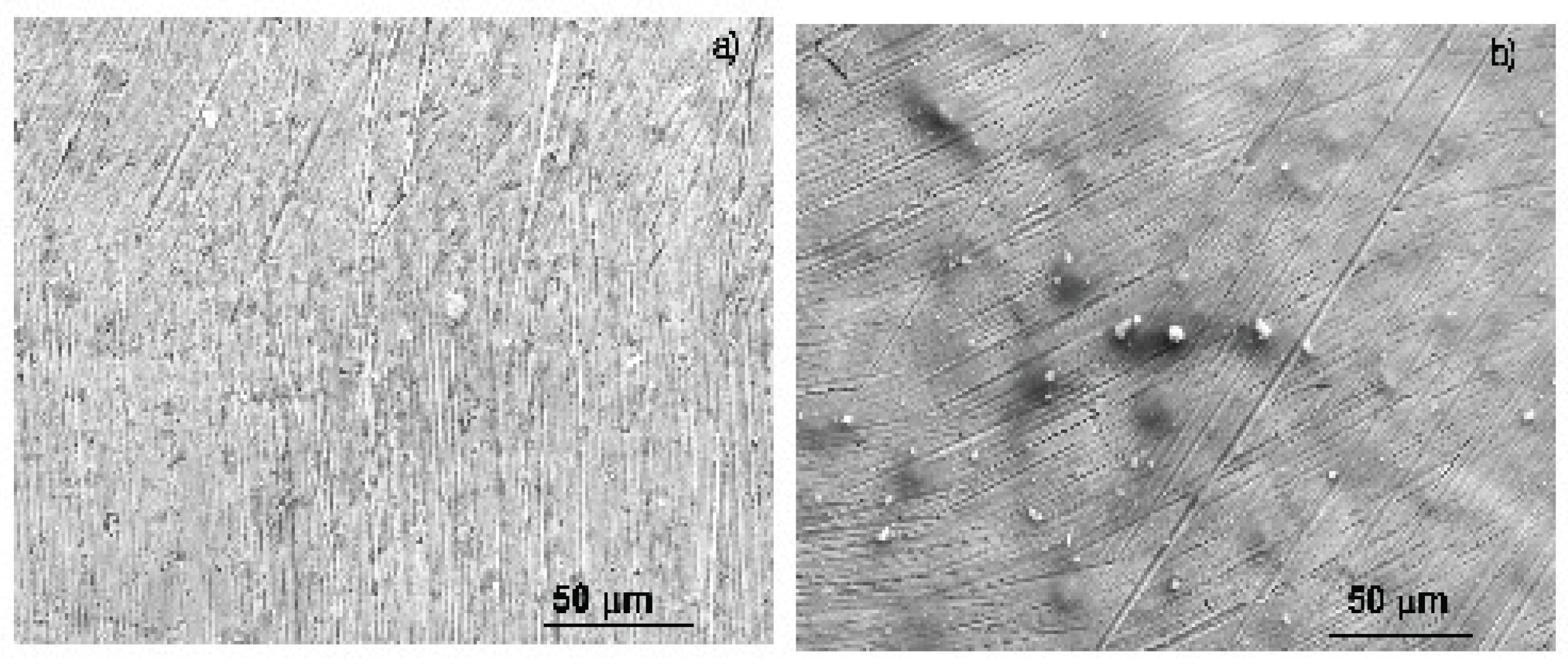

3.5. Surface Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Yan, H.; Rashid, M.R.B.A.; Khew, S.Y.; Li, F.; Hong, M. Wettability transition of laser textured brass surfaces inside different mediums. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z. Corrosion behavior of copper T2 and brass H62 in simulated Nansha marine atmosphere. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1831–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chraka, A.; Seddik, N.B.; Raissouni, I.; Kassout, J.; Choukairi, M.; Ezzaki, M.; Zaraali, O.; Belcadi, H. Electrochemical explorations, SEM/EDX analysis, and quantum mechanics/molecular simulations studies of sustainable corrosion inhibitors on the Cu-Zn alloy in 3% NaCl solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 387, 122715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijevic, S.P.; Dimitrijevic, S.B.; Koerdt, A.; Ivanovic, A.; Stefanovic, J.; Stankovic, T.; Gerengi, H. Comparison of Corrosion Resistance of Cu and Cu72Zn28 Metals in Apricot Fermentation Liquid. Materials 2025, 18, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avdeev, Y.G.; Nenasheva, T.A.; Luchkin, A.Y.; Marshakov, A.I.; Kuznetsov, Y.I. Complex InhibitorProtection of Some Steels in Hydrochloric Acid Solutions by 1,2,4-Triazole Derivatives. Materials 2025, 18, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedik, A.; Athmani, S.; Saoudi, A.; Ferkous, H.; Ribouh, N.; Lerari, D. Experimental and theoretical insights into copper corrosion inhibition by protonated amino-acids. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23718–23735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, M.P.S.; Do Nascimento, C.C.F.; Dos Santos, D.D.M.L. Evaluation of Palm Oil Corrosion Inhibition Through Image Analysis in Copper Pipes Used in Air Conditioning Systems. J. Bio. Tribo Corros. 2025, 11, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowjanya, B.; Vykuntam, S.; Raj, A. A.; Arava, A.; King, P.; Vangalapati, M.; Myneni, V.R. ; Harnessing the potential of Aegle marmelos pulp extract for sustainable corrosion inhibition of brass in 1M H2SO4: insights from characterization and optimization. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14, 30997–31008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idriss, H.O.; Seddik, N.B.; Achache, M.; Rami, S.; Zarki, Y.; Ennamri, A.; Janoub, F.; Bouchta, D. Shrimp shell waste-modified natural wood and its use as a reservoir of corrosion inhibitor (L-arginine) for brass in 3% NaCl medium: Experimental and theoretical studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 398, 124330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailou, H.; Taghzouti, S.; Lahcen, I. A.; Idrissi, M.B.; Touir, R.; Ebn Touhami, M,E.H. New aryl-himachalene benzylamines derivatives as eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors at low concentration for brass 62/38 in 200 ppm NaCl: Experimental, analyses and theoretical approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319,139345. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Recent advances in carbon dots as powerful ecofriendly corrosion inhibitors for copper and its alloy. Mater. Today Sust. 2024, 26, 100706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, M.M.; Abd ElRhiem, E.; Atta, W.; Ghany, N.A.; Abdelbar, M. Investigation and evaluation of the efficiency of palm kernel oil extract for corrosion inhibition of brass artifacts. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaser, A,A.; El-Mahdy, M.S.; Mahmoud, E.E.E.; Fouda, A.S. Recycling of expired ciprofloxacin in synthetic acid rain (SAR) solution as a green corrosion inhibitor for copper: a theoretical and experimental evaluation. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2024,54, 439–456. [CrossRef]

- Bustos Rivera-Bahena, G.; Ramírez-Arteaga, A.M; Saldarriaga-Noreña, H.A.; Larios-Gálvez, A. K.; González-Rodríguez, J.G.;Romero-Aguilar, M.; López-Sesenes, R. Hexane extract of Persea schiedeana Ness as green corrosion inhibitor for the brass immersed in 0.5 M HCl. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6512. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G.; Gutierrez-Granda, D.G.; Larios-Galvez, A.K. Use of Thymus vulgaris Extract as Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Bronze in Acid Rain. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 2022, 8, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoub, F.; Chraka, A.; Kassout, J. Innovative Characterization of Coffee Waste Extracts and Their Derivatives as Efficient Ecological Corrosion Inhibitors for Copper Alloy in 3% NaCl: Phytochemical Investigations, Electrochemical Explorations, Morphological Assessment and New Computational Methodology. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 2024, 10, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.S.; El-Dossoki, F.I. Shady. I.A. Adsorption and corrosion inhibition behavior of polyethylene glycol on α-brass alloy in nitric acid solution. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2018, 11, 67-77. [CrossRef]

- Raeisi, S.; Yousefpour, M. The electrochemical study of the garlic extract as a corrosion inhibitor for brass in the nitric acid solution. .Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024. 312, 128516. [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, M.B. Tasić, Ž.Z.; Petrović, M.B.; Simonović, A.T.; Antonijević, M.M. Electrochemical and DFT studies of brass corrosion inhibition in 3% NaCl in the presence of environmentally friendly compounds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16081. [CrossRef]

- Vanangamudi, A.; Punniyakoti, S. Cocos nucifera-mediated electrochemical synthesis and coating of CuO/ZnO nanostructures on Fe ship strips for marine application. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2024, 17, 2356612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zha, F.; Lid, L.; Wei, J. ; Liu, K, The Corrosion Behavior of T2 Brass, in Power Plant Generator Stator Cooling Water. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2019, 55, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigdorovich, V.I.; Tsygankova, L.E.; Dorohova.; A.N.; Dorohov, A.V. Knyazeva, L.G.; Uryadnikov, A.A. Protective ability of volatile inhibitors of IFKhAN series in atmospheric corrosion of brass and copper at high concentrations of CO2, NH3 and H2S in air. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2018, 7, 331–339.

- Vigdorovich, V.I.; Knyazeva, L.G.; Zazulya, A.N; Prokhorenkov, V.D.; Dorokhov, A.V.; Kuznetsova, E.G.; Uryadnikov, A.A. Goncharova, O.A. Suppression of Atmospheric Corrosion of Brass Using Volatile Inhibitors. Russ. Agric. Sci. 2017,43, 342–346.

- Svoboda, R.; Plamer, D.A. Behavior of copper in generator stator cooling-water systems. Power Plant Chem. 2009, 11, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Duffeau, F.; Aspden, D.; Coetzee, G. Guide on stator water chemistry management. Study Comm. 2010, 4, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, K.; Pilarczyk, M.; Quinkertz, R.; Glos, S.; Kuhn, M. Optimization of a CO2-Free Offshore Power Plant Using Supercritical CO2. Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2024: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition. Volume 11: Supercritical CO2. London, United Kingdom. June 2024, 24–28. V011T28A028. ASME. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xu, H.; Xu, C.; Xin, T. Off-design performance analysis and comparison of a coal-based semi-closed supercritical CO2 cycle under different operational strategies. Energy, 2025, 315, 134441. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, E.S.M.; Hucl, P.J.; Sosulski, F.W.J. Structural and compositional characteristics of canaryseed (Phalaris canariensis L.). Agric. Food Chem. 1997,45,3049-3055. [CrossRef]

- May, W.E.; Train, J.C.; Greidanus, L. Response of annual canarygrass(Phalaris canariensis L.)to nitrogen fertilizer and fungicide applications. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2022,102, 83-94. [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.P.; Hucl, P.; L’Hocine, L.; Nickerson, M.T. Microstructure and distribution of oil, protein, and starch in different compartments of canaryseed(Phalaris canariensis L.) Cereal Chem. 2021, 98,405-422. [CrossRef]

- Galvan E, Larios Galvez A K, Ramirez Arteaga A M, Lopez Sesenes R, Gonzalez Rodriguez J G (2024) Electrochemical, gravimetric and surface studies of Phalaris canariensis oil extract as corrosion inhibitor for 316 L type stainless steel in H2O-LiCl mixtures. Sci Rep 14:23370. [CrossRef]

- Borko, T.; Bilic, G.; Žbulj, K.; Otmacic, J.; Curkovic, H. Individual and Joint Effect of Oleic Acid Imidazoline and CeCl3 on Carbon Steel Corrosion in CO2-Saturated Brine Solution. Coatings 2025, 15, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabagh, A.M.; Migahed, M.A.; Mishrif, M.R.; Abd-Elraouf, M.; Abd-El-Bary, H.M.; Mohamed, Z.M.; Hussein, B.M. Corrosion Inhibition Efficiency Of Oleic Acid Surfactant Derivatives For Carbon Steel Pipelines In Petroleum Formation Water Saturated with CO2. Paper presented at the Offshore Mediterranean Conference and Exhibition, Ravenna, Italy, March 2013.

- Fayyad, E.M.; Sadasivuni, K.K.; Ponnamma, D.; Al-Maadeed, M.A.A. ; Oleic acid-grafted chitosan/graphene oxide composite coating for corrosion protection of carbon steel. Carbohydrate Polymers 2016, 151, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Edan, A.K.; Isahak, W.N.R.W.; Ramli, Z.A.C; Al-Azzawi, W.K.A.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Jabbar, H.S.; Al-Amiery, A. Palmitic acid-based amide as a corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1M HCl. Heliyon 2023, 9, 14657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathy, D.B.; Murmu, M.; Banerjee, P.; Quraishi, M.A. Palmitic acid based environmentally benign corrosion inhibiting formulation useful during acid cleansing process in MSF desalination plants. Desalination 2019, 472, 114128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.R.; Xu, Y.L.; Chen, C.K.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.W.; Yang, Z.N. New Aspects of Copper Corrosion in a Neutral NaCl Solution in the Presence of Benzotriazole. Corrosion 2018, 74, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Ming, Z.; Han, X. Electrochemical response of mild steel in ferrous ion enriched and CO2 saturated solutions. Corros Sci 2015, 96, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolinelli, L.D.; Perez, T.; Simison, S.N. The effect of pre-corrosion and steel microstructure on inhibitor performance in CO2 corrosion. Corr Sci 103:2456-2560. Paolinelli LD, Perez T, Simison SN (2008) The effect of pre-corrosion and steel microstructure on inhibitor performance in CO2 corrosion. Corr Sci 2008,103, 2456-2560. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Li, X.; Du, C. Effect of acetic acid on CO2 corrosion of 3Crlow-alloy steel. Mater Chem Phys 2012, 132, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeachu, I.B.; Obot, I.B.; Sorour, A.A.; Abdul-Rashid, M.I. Green corrosion inhibitor for oilfield application I: Electrochemical assessment of 2-(2-pyridyl) benzimidazole for API X60 steel under sweet environment in NACE brine ID196. Corros Sci 2019, 150, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karfa, R.P.; Adhikari, U.; Sukul, D. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in acidic medium by polyacrylamide grafted Guar gum with various grafting percentage: Effect of intramolecular synergism. Corros Sci 2014, 88, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, R.A.; Silve, G.N.; Quijano, M.A.; Hernandez, H.H.; Romo, M.R.; Cuan, A.; Pardave, M.P. Electrochemical study of 2-mercaptoimidazole as a novel corrosion inhibitor for steels. Electrochim Acta 2009, 54, 5393–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cinh (ppm) |

Ecorr (V) |

Icorr A/cm2) |

a (V/dec) |

c (V/dec) |

I.E. (%) |

|

| 0 | -0.265 | 3.7 x 10-7 | ------ | 270 | ----- | --- |

| 25 | -0.165 | 6.8 x 10-8 | 45 | 520 | 81 | 0.81 |

| 50 | -0.100 | 3.0 x 10-8 | 55 | 540 | 91 | 0.91 |

| 100 | -0.035 | 1.0 x 10-9 | ------ | 555 | 99 | 0.99 |

| Cinh (ppm) |

Rct (ohm cm2) |

CPEdl (F cm-2) |

ndl | Rox (ohm cm2) |

CPEox (F cm-2) |

nox | Rinh (ohm cm2) |

CPEinh (F cm-2) |

ninh | I.E.(%) |

| 0 | 1777 | 0.7 | 10503 | 0.7 | ------ | ------ | ----- | ---- | ||

| 25 | 6959 | 0.8 | 12079 | 0.8 | 12489 | 0.8 | 77 | |||

| 50 | 12578 | 0.8 | 18744 | 0.8 | 36472 | 0.8 | 88 | |||

| 100 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 99 |

| Immersion time (h) |

Rct (ohm cm2) |

CPEdl (F cm-2) |

ndl | Rox (ohm cm2) |

CPEox (F cm-2) |

nox |

| 0 | 1777 | 0.7 | 10503 | 0.7 | ||

| 6 | 1976 | 0.8 | 22105 | 0.8 | ||

| 12 | 2125 | 0.8 | 46186 | 0.8 | ||

| 18 | 2468 | 0.9 | 56360 | 0.9 | ||

| 24 | 2797 | 0.9 | 90613 | 0.9 |

| Immersion time (h) |

Rct (ohm cm2) |

CPEdl (F cm-2) |

ndl | Rox (ohm cm2) |

CPEox (F cm-2) |

nox | Rinh (ohm cm2) |

CPEinh (F cm-2) |

ninh | I.E .(%) |

| 0 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 99 | ||||

| 6 | 0.5 | 8.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 99 | |||||

| 12 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 99 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 99 | ||||||

| 24 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).