2. Methods

2.2. Study Design and Participants

This is a post-hoc analysis from the SPRINT- Memory and Cognition in Decreased Hypertension (MIND) study, which was part of the SPRINT trial. The design and protocol of the SPRINT and SPRINT-MIND have been previously detailed [

8,

9]. Briefly, SPRINT enrolled 9,361 participants with hypertension but without diabetes mellitus, who were randomized to either a standard or intensive BP control group. The target for SBP was set at <140 mm Hg in the standard treatment group and <120 mmHg in the intensive treatment group. In SPRINT-MIND, the primary outcome was the incidence of adjudicated PD, with secondary outcomes including Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and a composite measure of PD and MCI. The primary goal of the SPRINT-MIND study was to evaluate whether intensive SBP control could reduce the incidence of all-cause dementia.

Exclusion criteria included known secondary hypertension, recent TIA or stroke, symptomatic heart failure within the past six months or an ejection fraction below 35%, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and a baseline diagnosis of dementia or use of dementia-specific medications. A comprehensive list of exclusion criteria is available in the SPRINT-MIND protocol [

8]. For the purpose of the current post-hoc analysis, participants with missing data on baseline and follow-up AF or cognitive outcomes were excluded from the study.

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained at all study sites, and all participants provided informed written consent.

2.3. Electrocardiogram and Atrial Fibrillation Diagnosis

Electrocardiograms (ECGs) were recorded at baseline, at two- and four-year follow-up visits, and at the close-out visit. Digital ECGs were captured with a GE MAC 1200 electrocardiograph, set to a calibration of 10 mm/mV and a recording speed of 25 mm/s. All ECGs were centrally processed at the EPICARE ECG Center (Epidemiological Cardiology Research Center, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina). AF was automatically detected using GE MUSE 12-SL Marquette, version 2001 (GE, Milwaukee, WI) and then confirmed visually by a cardiologist.

2.4. Ascertainment of Probable Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairments

Trained examiners evaluated cognitive status at baseline, at 2-year and 4-year follow-ups, and study closeout if this occurred more than one year after the 4-year follow-up. However, at the time of the early discontinuation of the SPRINT trial, many scheduled cognitive assessments for the 4-year had not been completed. These assessments were subsequently conducted during the extended follow-up visits.

The cognitive assessment protocol included tests of global cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA]), learning and memory (Logical Memory Forms I and II from the Wechsler Memory Scale), processing speed (Digit Symbol Coding test from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale), and functional capabilities (Functional Activities Questionnaire). Based on standardized diagnostic criteria, two independent adjudicators classified participants into three cognitive categories: no cognitive impairment, MCI, or PD. MCI was ascertained when it was observed at two consecutive visits. Participants classified as having PD no longer underwent further cognitive assessments. Consequently, individuals who transitioned from MCI to PD during follow-up were not reassessed for MCI. This approach resulted in the number of participants classified under the composite outcome being lower than the sum of those with PD and MCI.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Participants were categorized into two groups based on the presence of AF in their baseline or follow-up 12-lead ECG. Baseline characteristics were compared between the two groups using an independent sample T-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the association between time-dependent AF status and the incidence of cognitive outcomes (PD, MCI, and their composite outcome (PD/MCI), separately). The first model was adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, and treatment assignment. The second model incorporated additional adjustments for baseline SBP, smoking status, alcohol consumption, history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol levels, and statin use. In an additional model, we also adjusted for incident stroke occurring during follow-up. Participants were censored either at the time of diagnosis of cognitive outcomes (PD, MCI, or the composite outcome), or at the conclusion of their last follow-up visit, whichever occurred first.

As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded participants diagnosed with MCI within the first two years of follow-up to mitigate potential bias from undetected prevalent MCI at baseline, given that SPRINT MIND did not adjudicate baseline MCI status.

Consistency of the associations between AF and cognitive outcomes among SPRINT prespecified subgroups (age [<75 versus ≥75 years], sex, race [Black versus non-Black], SBP tertiles [≤132, >132 to <145, ≥145 mm Hg], prior CVD, and prior chronic kidney disease [defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 of body-surface area]) were assessed with a likelihood-ratio test for the interaction with the use of Hommel adjusted. Models were adjusted in a similar fashion to Model 2 in the main analysis.

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.1.1, PBC, Boston, MA, USA) and SPSS (version 27, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was determined at a two-sided p-value threshold of < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 8,539 participants (mean age 67.9 years, 35.1% female) with available baseline and follow-up ECG, and cognitive outcome data were included in our analysis. Of these, 264 participants had AF at baseline (n=111; 47 in the standard arm and 64 in the intensive arm) or during follow-up (n=153; 84 in the standard arm and 69 in the intensive arm). Participants with AF were generally older, more likely to be male, of White ethnicity, and had a higher prevalence of CVD history. Additionally, they exhibited lower eGFR and lower total cholesterol levels (

Table 1).

Over a median follow-up period of 5 years (interquartile range: 3.8 to 5.9 years), 318 PD, 625 MCI, and 849 a composite of both occurred. In multivariable Cox regression models adjusted for sociodemographics and treatment assignment AF as a time-dependent variable was significantly associated with increased risk of PD, MCI and a composite of both ( Hazard Ratio (HR) (95% CI ): 1.98 (1.19, 3.29), 1.64 (1.04, 2.57) and 1.74 (1.21, 2.50), respectively). These associations remained significant after further adjustment for CVD risk factors and potential confounders (HR (95% CI): 1.84 (1.09, 3.13), 1.59 (1.01, 2.53), 1.63 (1.12, 2.38), respectively)-

Table 2.

Further adjustment for incident stroke did not materially impact the results (HR (95% CI): 1.71 (1.06, 2.91), 1.53 (0.96, 2.43), and 1.55 (1.06, 2.27). Also, excluding incident MCI occurring within the first two years of follow-up, the AF as a time-dependent variable remained significantly associated with MCI (HR (95% CI): 1.69 (1.02, 2.82)) even after full adjustment for incident stroke (Supplementary Table S1).

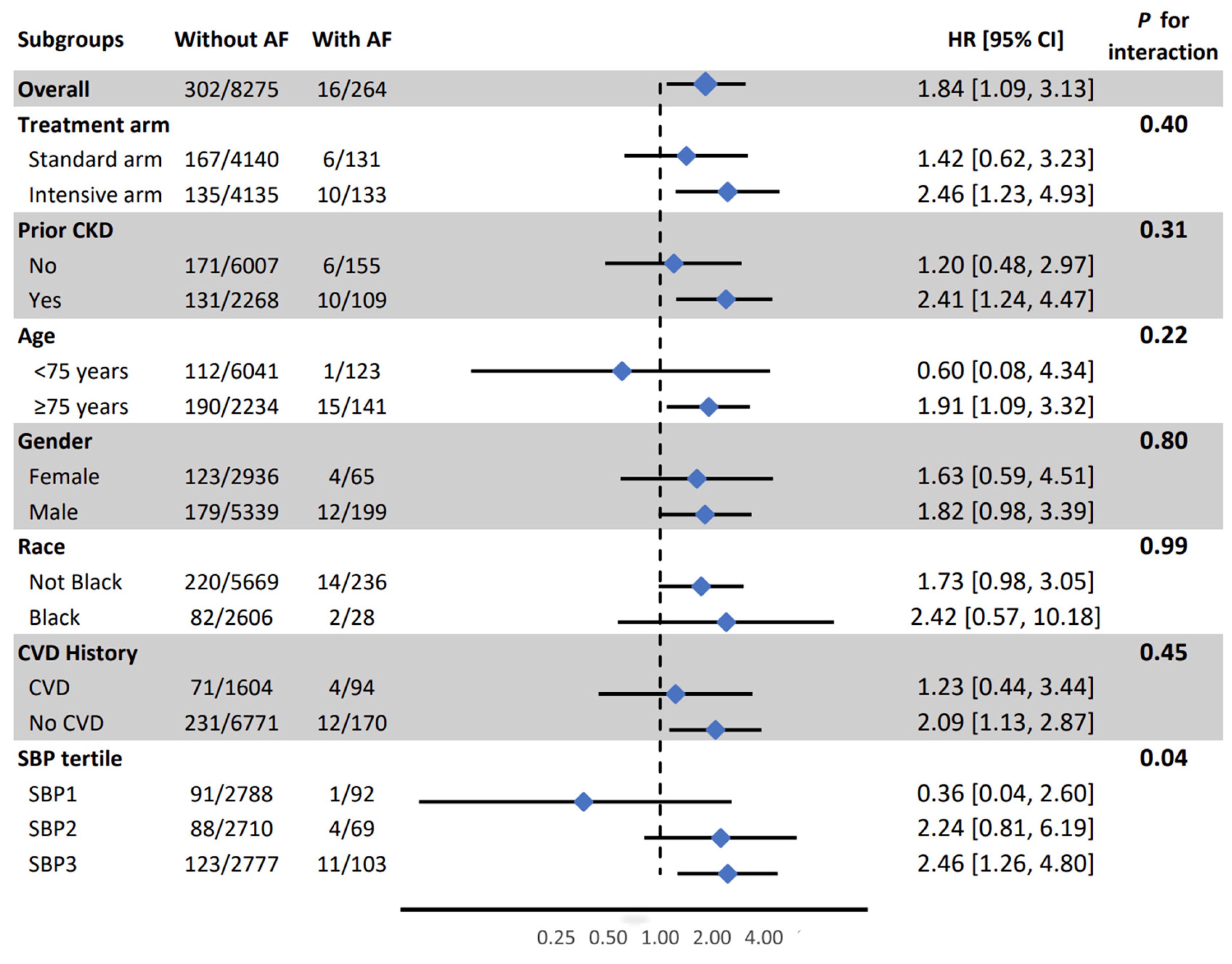

In subgroup analysis, the association between AF and PD was weaker in the lowest SBP tertile compared to other tertiles (HR (95% CI) for 1st, 2nd and 3rd tertile: 036 (0.04, 2.60), 2.24 (0.81, 6.19), nd 2.46 (1.26, 4.80), respectively, interaction p-value =0.04) (

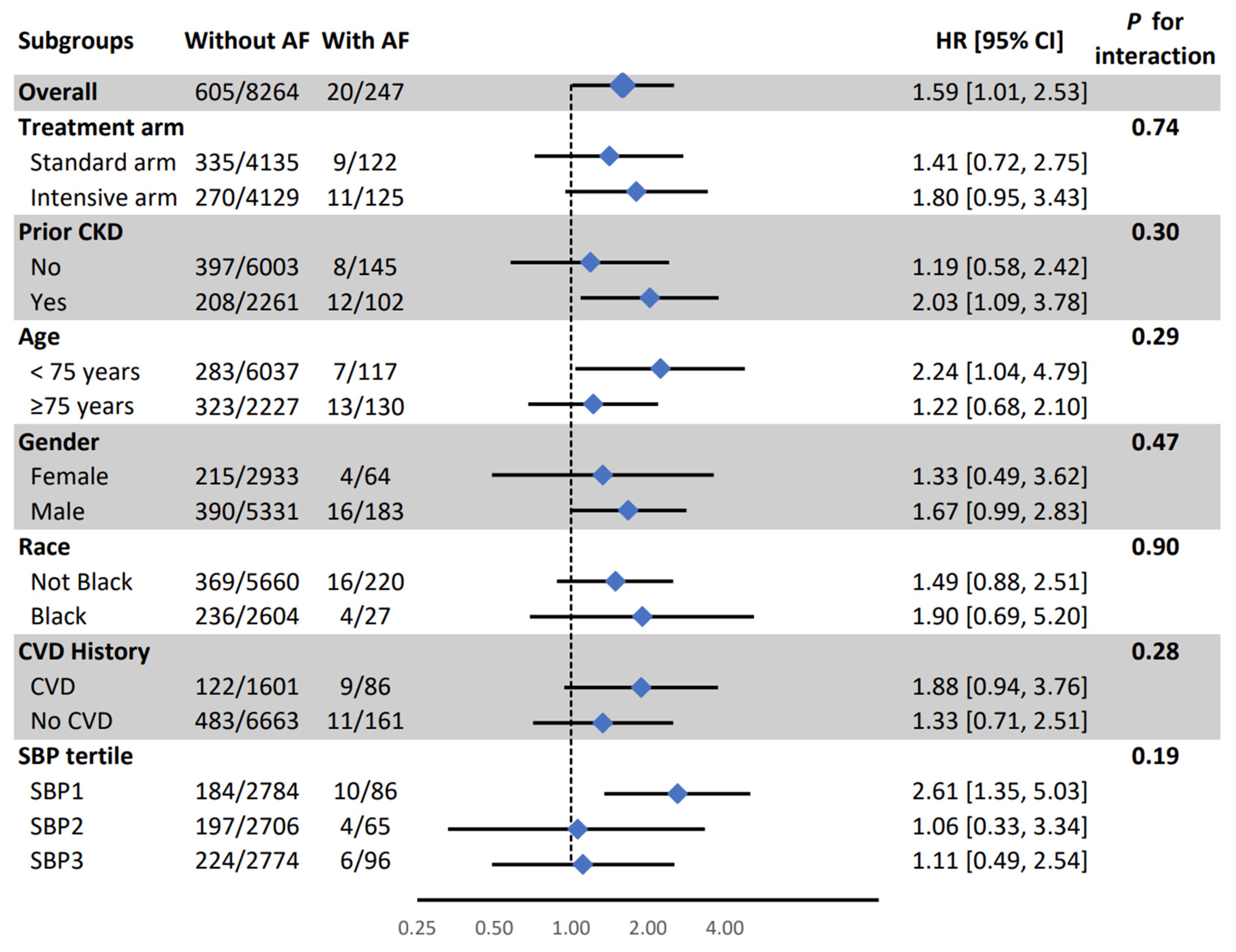

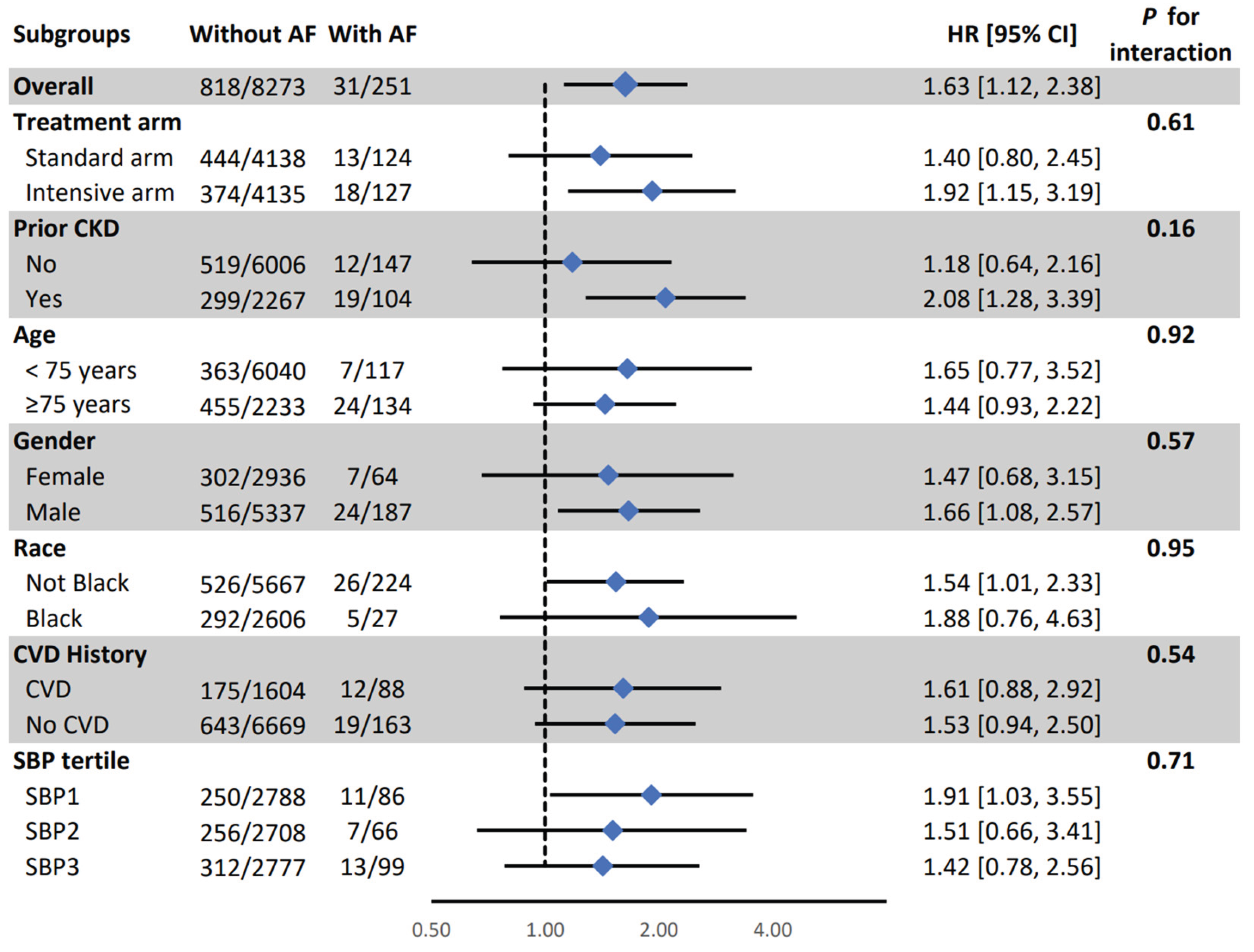

Figure 1). All other associations were consistent in SPRINT prespecified subgroups (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

At present, there are no widely available effective treatments that favorably alter the natural history of cognitive decline and dementia, placing emphasis on the importance of identifying modifiable risk factord. In this analysis from the SPRINT trial we found that AF was significantly associated with increased risk of PD, MCI, and a composite of both outcomes. These associations were independent of baseline CVD risk factors or incident stroke that occurred during follow-up. In subgroup analysis, the association between AF and PD was stronger among participants in the second and third SBP tertiles compared to those in the first tertile. Collectively, our results emphasize the potential for early detection and management of AF in patients with hypertension to reduce the risk of cognitive impairment and underscore the importance of low SBP in reducing the impact of AF on the risk of cognitive decline. Further research is needed to investigate whether targeted interventions, such as rhythm control or anticoagulation therapy, can effectively mitigate the cognitive risks associated with AF.

Previous studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding the association between AF and cognitive impairment in the general population. For instance, an analysis from the Rotterdam Study, which examined the relationship between AF and incident dementia in White participants over a 20-year period, found no significant association between AF and dementia after adjusting for stroke [

10]. Conversely, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities– Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS), which evaluated a biracial population over a 20-year period, suggested that AF is significantly associated with both cognitive decline and incident dementia, even after adjusting for ischemic stroke [

3]. Moreover, the Whitehall II study, which followed a cohort aged 45 to 85 years over 15 years, reported a significantly higher risk of incident dementia among AF participants, even after multivariable adjustment for potential confounders, including stroke [

11]. The association between AF and dementia in the Whitehall II study was consistent in both older and younger age groups Our findings are in agreement with the findings from ARIC and Whitehall II studies. Possibly, racial diversity and age of the populations can explain the inconsistencies among different studies.

Although AF has been linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment, decline, and dementia [

12,

13,

14], its association with specific dementia subtypes remains debated. While some studies connect AF to various forms, including vascular, senile, mixed dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease [

15,

16], others suggest a stronger correlation with Alzheimer’s disease followed by vascular dementia [

17]. The mechanisms behind this association are not fully understood [

18]. Shared risk factors—such as advanced age, diabetes, CVD, smoking, hypertension, cerebrovascular diseases, and CKD—may partly explain the link between AF and vascular dementia. This raises the question of whether AF directly contributes to dementia or if the relationship is confounded by these overlapping factors. However, our study found that AF remained significantly associated with dementia even after adjusting for these variables, suggesting an independent risk.

Some research attributes AF-related cognitive impairment to an elevated risk of stroke and TIA [

19,

20]. Yet, as our findings and the ARIC study show, the association persists even after excluding stroke patients. A recent meta-analysis of over 2.8 million individuals further supports this, demonstrating AF’s consistent link to cognitive impairment in the general population, stroke-free individuals, and post-stroke cohorts [

21]. This implies that AF itself, beyond overt stroke, may drive cognitive decline through other mechanisms. One such mechanism could be silent cerebral infarction [

22,

23]. The ARIC Study found that AF was associated with cognitive decline only in patients with MRI evidence of silent cerebral infarction [

24]. Shared vascular risk factors may contribute to this relationship. In our study, even after excluding diabetes and adjusting for other vascular risks (e.g., high SBP, dyslipidemia, smoking), AF remained significantly tied to cognitive impairment. Additionally, beat-to-beat variability and reduced stroke volume in AF may cause cerebral hypoperfusion, leading to cerebral volume loss, white matter lesions, and small vessel disease [

25,

26]. These pathological changes could further contribute to cognitive decline in AF patients.

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

Our study has some limitations that warrant consideration. The current analyses focuses exclusively on a population with hypertension, without a history of diabetes mellitus or prior stroke. Consequently, the generalizability of our findings to broader populations should be interpreted with caution. Second, our analysis was based on ECG-detected AF, which may underestimate the true burden of AF, particularly paroxysmal AF, which could go undetected during routine follow-up visits. Nevertheless, the undetected AF can only bias the results to null, and hence the reported associations in our analysis are conservative and could be stronger if those undetected AF were included. Third, the development of dementia or MCI may occur several years after the onset of AF. A longer follow-up duration could potentially strengthen the observed association between AF and cognitive outcomes in this population.

The present study has several notable strengths. The cognitive outcomes were adjudicated by a committee of experts, and the AF was assessed centrally by individuals blinded to study outcomes. The study population is a distinct group of high-risk hypertensive patients without a history of stroke, addressing a critical gap in the literature. By excluding individuals with a history of stroke and diabetes, and accounting for key cardiovascular risk factors, our study provides novel insights into the independent relationship between AF and cognitive impairment, minimizing confounding from cerebrovascular and CVD risk factors. Furthermore, we employed a time-dependent modeling approach for AF, allowing for a more accurate representation of its dynamic nature over time. The inclusion of subgroup analyses based on age, race, gender, treatment assignment, CVD history, and CKD further strengthens our study by offering a nuanced understanding of potential effect modifications across diverse populations.

4.2. Conclusions

AF is associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia, independent of vascular risk factors and stroke in patients with hypertension but without diabetes. Further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms and to investigate whether targeted interventions, such as rhythm control or anticoagulation therapy, can effectively mitigate the cognitive risks associated with AF

Figure 1.

Association between atrial fibrillation and probable dementia in pre-specified subgroups. AF: Atrial Fibrillation, CI: Confidence Interval, CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease, CVD: Cardiovascular Disease, HR: Hazard Ratio, SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and treatment assignment., systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, prior cardiovascular diseases, number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Figure 1.

Association between atrial fibrillation and probable dementia in pre-specified subgroups. AF: Atrial Fibrillation, CI: Confidence Interval, CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease, CVD: Cardiovascular Disease, HR: Hazard Ratio, SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and treatment assignment., systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, prior cardiovascular diseases, number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Figure 2.

Association between atrial fibrillation and mild cognitive impairment in pre-specified subgroups. AF: Atrial Fibrillation, CI: Confidence Interval, CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease, CVD: Cardiovascular Disease, HR: Hazard Ratio, SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and treatment assignment., systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, prior cardiovascular diseases, number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Figure 2.

Association between atrial fibrillation and mild cognitive impairment in pre-specified subgroups. AF: Atrial Fibrillation, CI: Confidence Interval, CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease, CVD: Cardiovascular Disease, HR: Hazard Ratio, SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and treatment assignment., systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, prior cardiovascular diseases, number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Figure 3.

Association between atrial fibrillation and a composite of probable dementia mild cognitive impairment in pre-specified subgroups. AF: Atrial Fibrillation, CI: Confidence Interval, CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease, CVD: Cardiovascular Disease, HR: Hazard Ratio, SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and treatment assignment., systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, prior cardiovascular diseases, number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Figure 3.

Association between atrial fibrillation and a composite of probable dementia mild cognitive impairment in pre-specified subgroups. AF: Atrial Fibrillation, CI: Confidence Interval, CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease, CVD: Cardiovascular Disease, HR: Hazard Ratio, SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure. Model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and treatment assignment., systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, prior cardiovascular diseases, number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants stratified by atrial fibrillation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants stratified by atrial fibrillation.

Variables

N (%) or mean ± SD |

Total Participants

(N = 8539) |

With AF

(N = 264) |

Without AF

(N = 8275) |

| Age (year) |

67.9 ± 9.3 |

74.0 ± 8.6 |

67.7 ± 9.2 |

| Female |

3001 (35.1%) |

65 (24.6%) |

2936 (35.5%) |

| Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

Black

|

2504 (29.3%) |

27 (10.2%) |

2477 (29.9%) |

|

Hispanic

|

883 (10.3%) |

15 (5.7%) |

868 (10.5%) |

|

White

|

4997 (58.5%) |

219 (83%) |

4778 (57.7%) |

|

Others

|

155 (1.8%) |

3 (1.1%) |

152 (1.8%) |

| Non-College graduate |

5075 (59.4%) |

143 (54.2%) |

4932 (59.6%) |

| Intensive treatment arm |

4268 (50.0%) |

133 (50.4%) |

4135 (50.0%) |

| Prior CVD |

1698 (19.8%) |

94 (35.6%) |

1604 (19.4%) |

| Smoking history, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Former

|

3662/8530 (42.9%) |

163/264 (61.7%) |

3499/8266 (42.3%) |

|

Current

|

1095/8530 (12.8%) |

16/264 (6.1%) |

1079/8266 (13%) |

| Alcohol use |

331/8534 (3.8%) |

5 (1.9%) |

326 (3.9%) |

| SBP |

139.5 ± 15.5 |

141.5 ± 17.5 |

139.4 ± 15.4 |

| SBP tertiles |

|

|

|

|

≤ 132 mm Hg

|

2880 (33.7%) |

92 (34.8%) |

2788 (33.7%) |

|

> 132 to < 145 mm Hg

|

2779 (32.5%) |

69 (26.1%) |

2710 (32.7%) |

|

≥ 145 mm Hg

|

2880 (33.7%) |

103 (39.0%) |

2777 (33.6%) |

| No. of BP lowering drugs |

1.83 ± 1.03 |

2.30 ± 0.99 |

1.82 ± 1.03 |

| eGFR |

71.8 ± 20.4 |

65.7 ± 18.1 |

72 ± 20.4 |

| Serum creatinine |

1.07 ± 0.33 |

1.11 ± 0.30 |

1.07 ± 0.33 |

| Total cholesterol |

190.0 ± 41.1 |

176.9 ± 38.5 |

190.5 ± 41.1 |

| Statin use, n (%) |

3736/8486 (44%) |

141/262 (53.8%) |

3595/8224 (43.7%) |

| HDL-Cholesterol |

52.7 ± 14.3 |

52.1 ± 13.9 |

52.8 ± 14.3 |

| BMI |

29.8 ± 5.7 |

30.2 ± 5.6 |

29.8 ± 5.7 |

Table 2.

Association of baseline and follow-up atrial fibrillation with cognitive outcomes in SPRINT trial.

Table 2.

Association of baseline and follow-up atrial fibrillation with cognitive outcomes in SPRINT trial.

| Outcome |

Events/participants

n (%) |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

With AF

(n=264) |

Without AF

(n=8275) |

Hazard ratio

(95% CI) |

p-value |

Hazard ratio

(95% CI) |

p-value |

| Probable Dementia (PD) |

16/264 (6.1%) |

302/8275 (3.6%) |

1.98 (1.19, 3.29) |

0.007 |

1.84 (1.09, 3.13) |

0.02 |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) |

20/247 (8.1%) |

605/8264 (7.3%) |

1.64 (1.04, 2.57) |

0.03 |

1.59 (1.01, 2.53) |

0.04 |

| Composite MCI/PD |

31/251 (12.3%) |

818/8273 (9.8%) |

1.74 (1.21, 2.50) |

0.002 |

1.63 (1.12, 2.38) |

0.009 |

CI: Confidence Interval, n: Number, SPRINT: Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and treatment assignment.

Model 2 adjusted for model 1 plus systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, prior cardiovascular diseases, number of antihypertensive medications, serum creatinine, total cholesterol, and statin use. |