Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

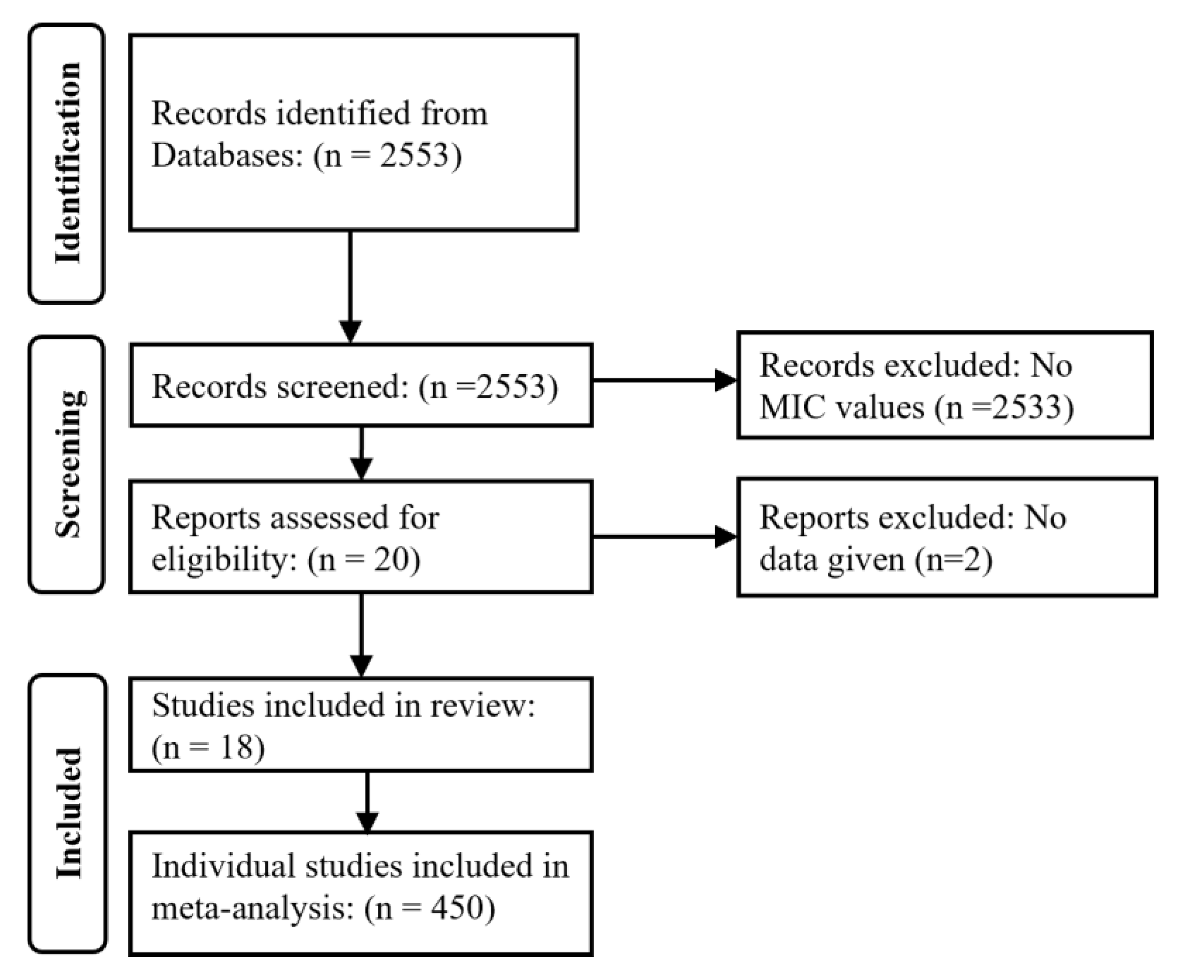

2.1. Literature Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria of Selected Studies

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Studies’ Selection and Characteristics

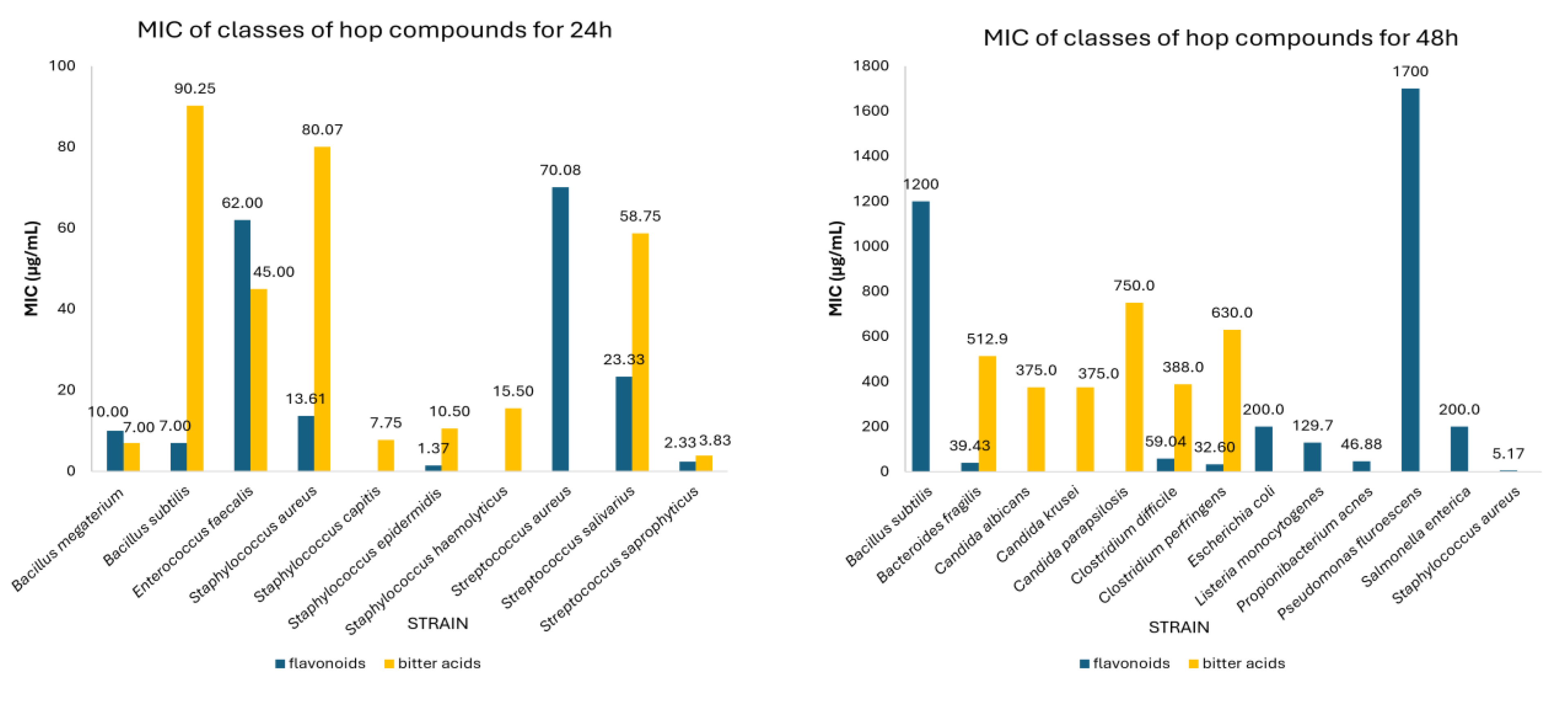

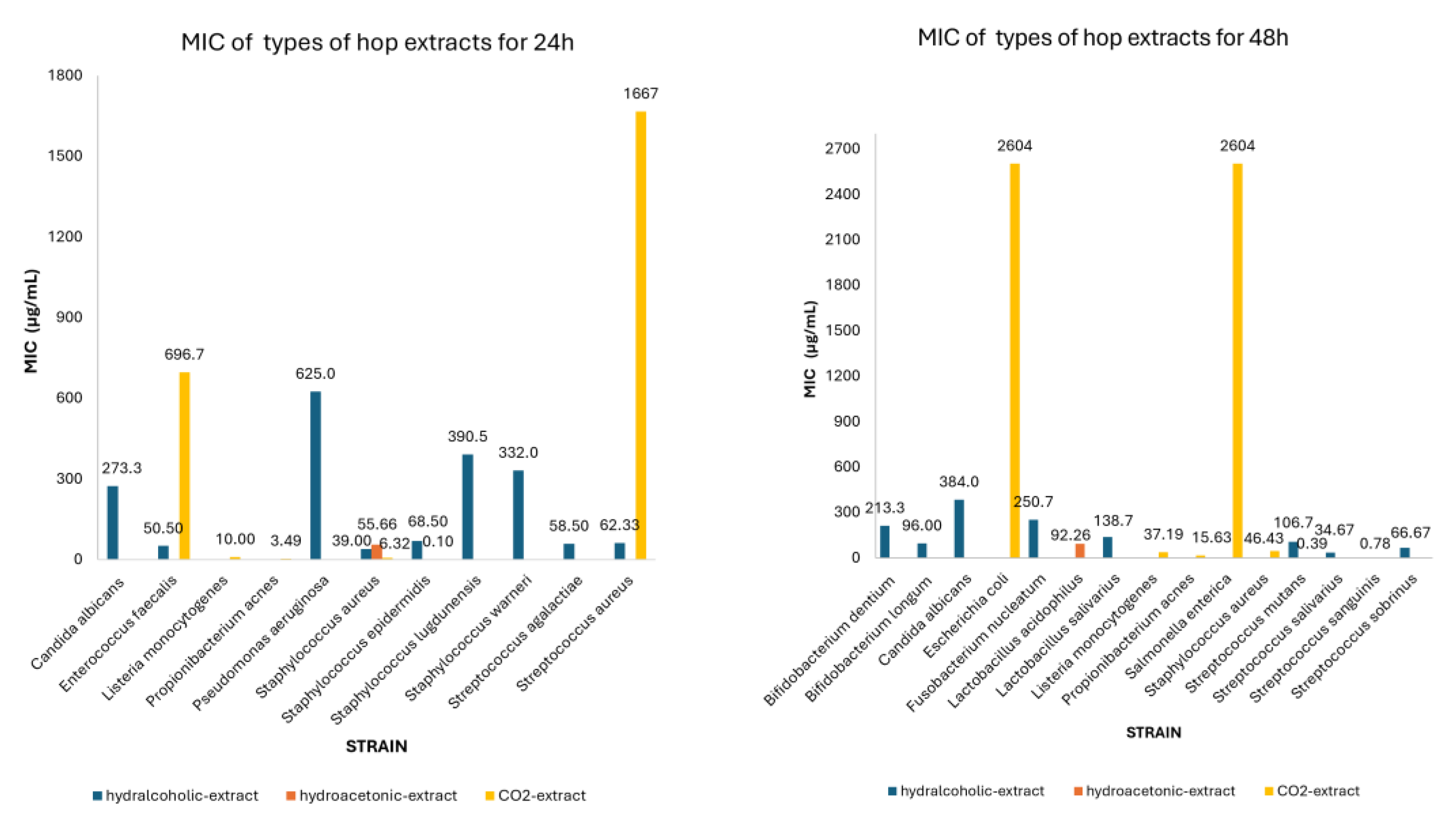

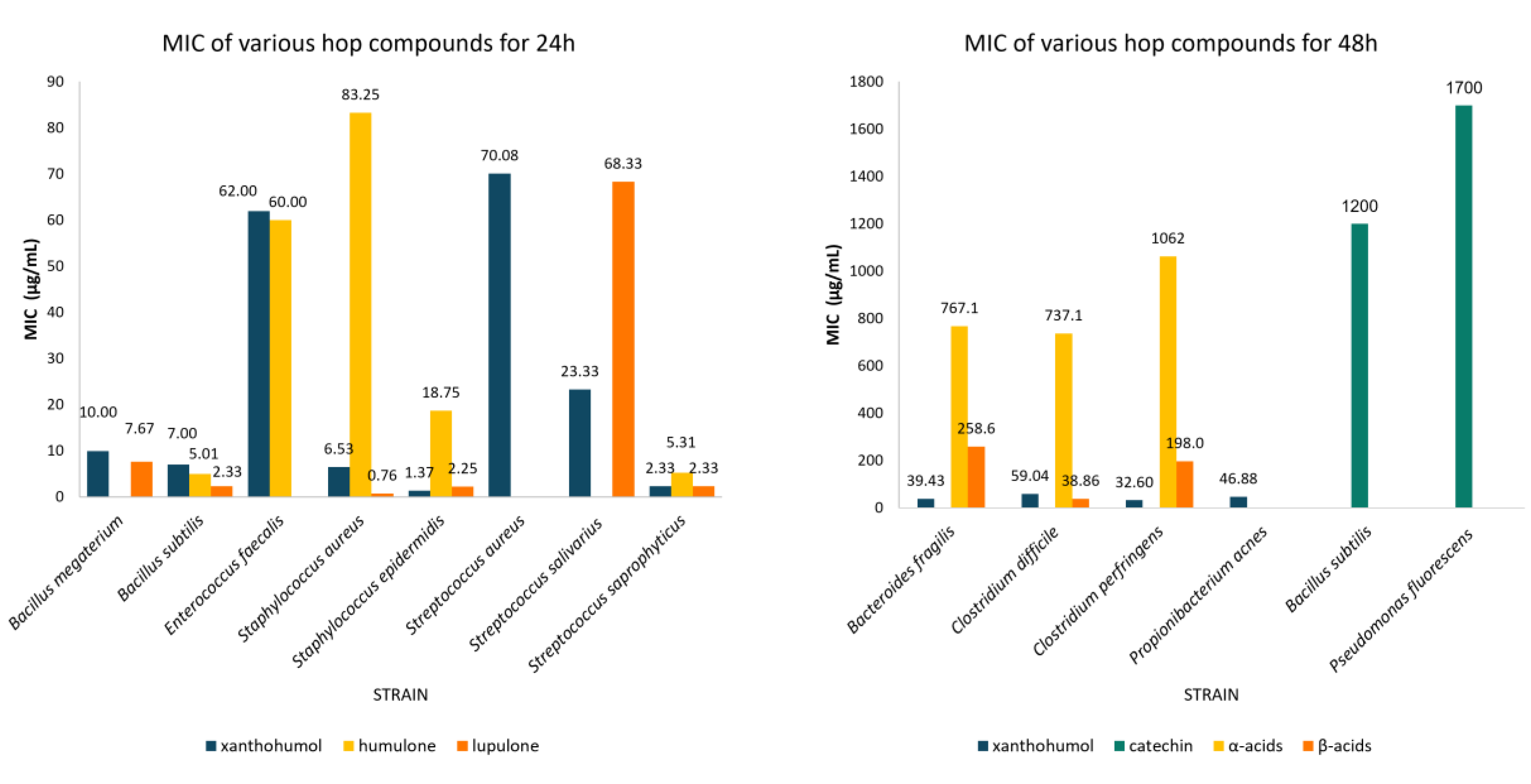

3.2. Meta-Analysis of MIC Values of Classes of Hop Compounds and Extracts

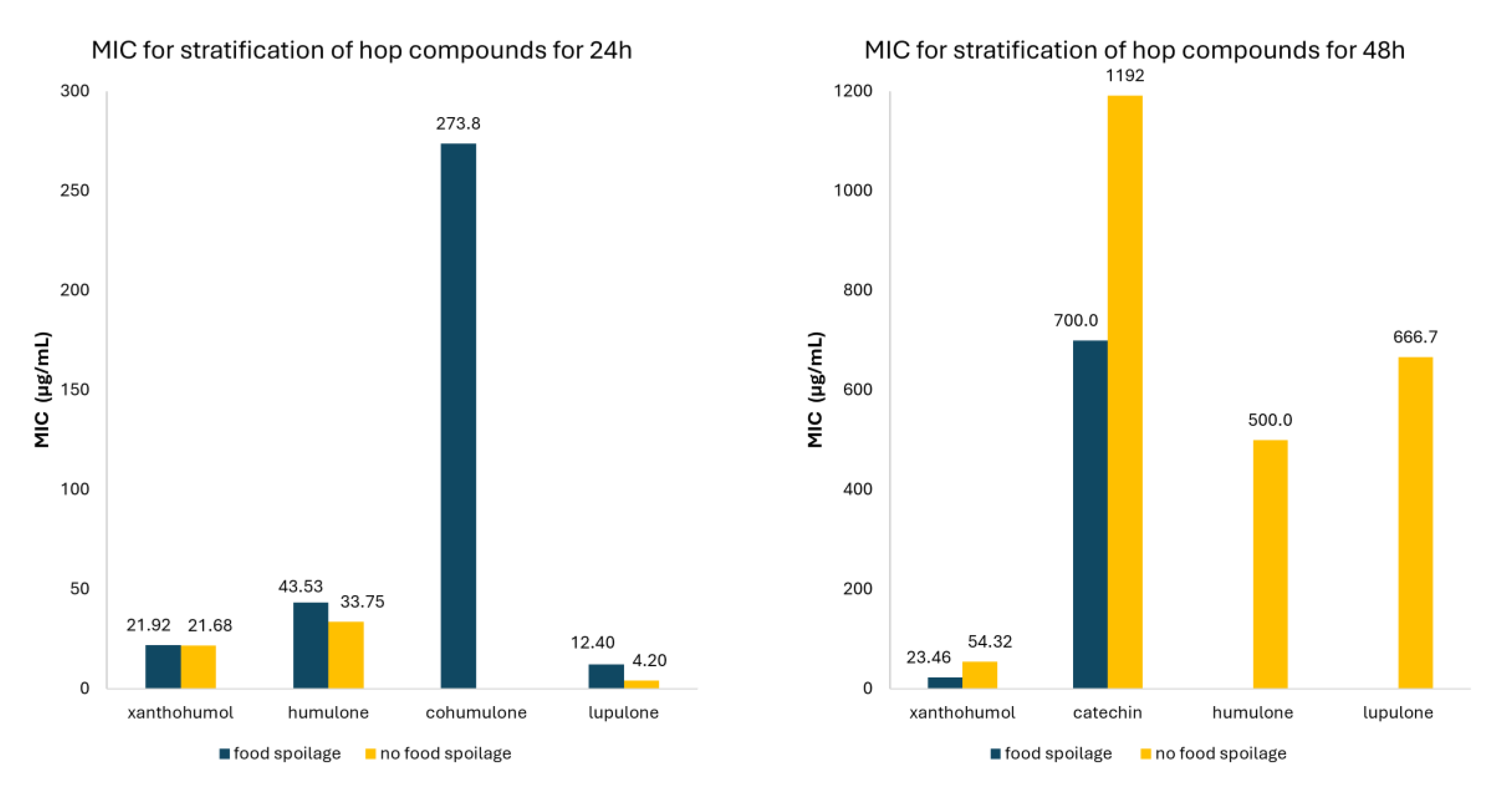

3.3. Stratification Meta-Analysis of MIC Values of Each Hop Compound

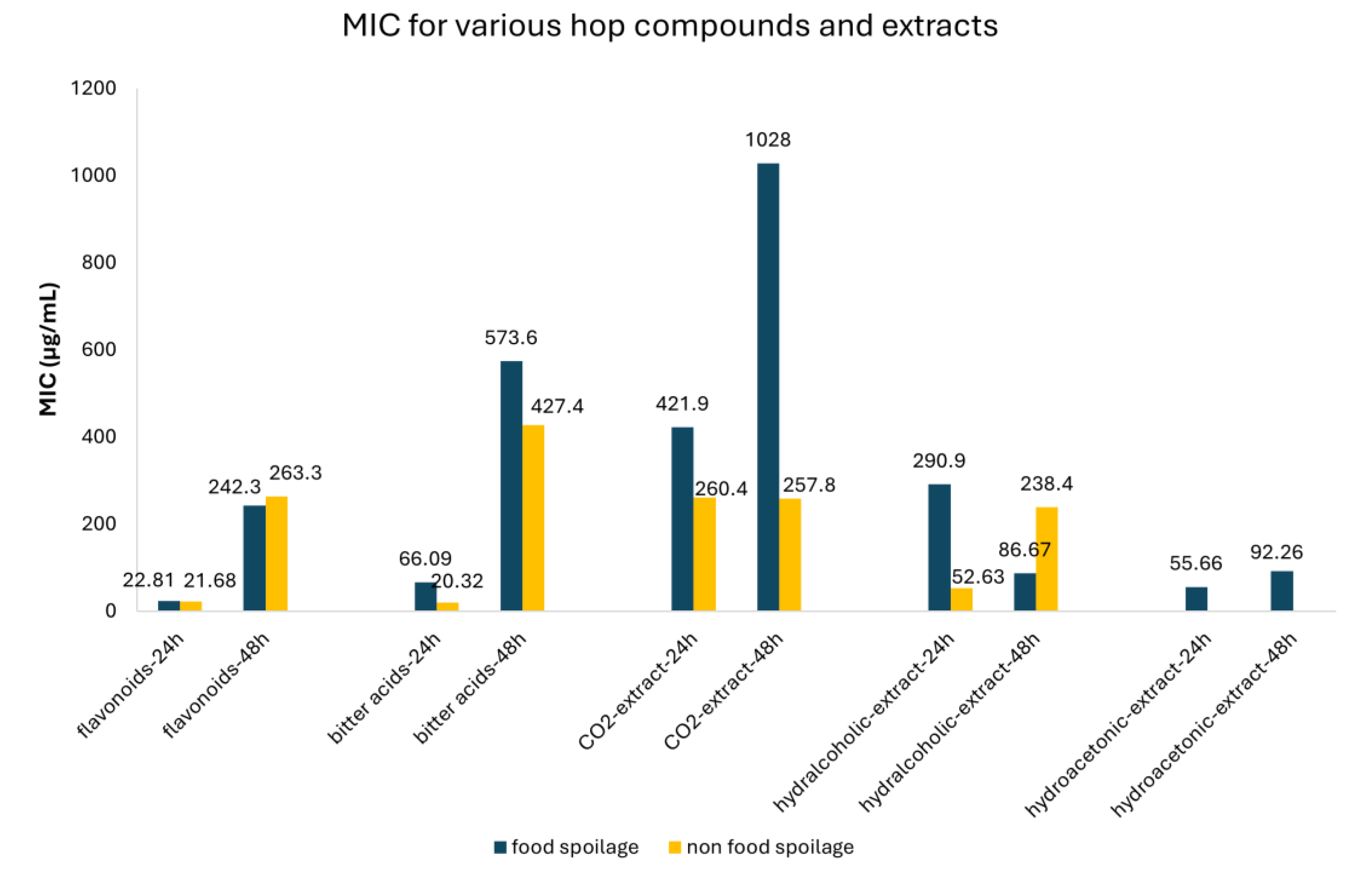

3.4. Meta-Analysis of MIC Values of Hop Compounds and Extracts for Food Spoilage and Non-Food Spoilage Microorganisms

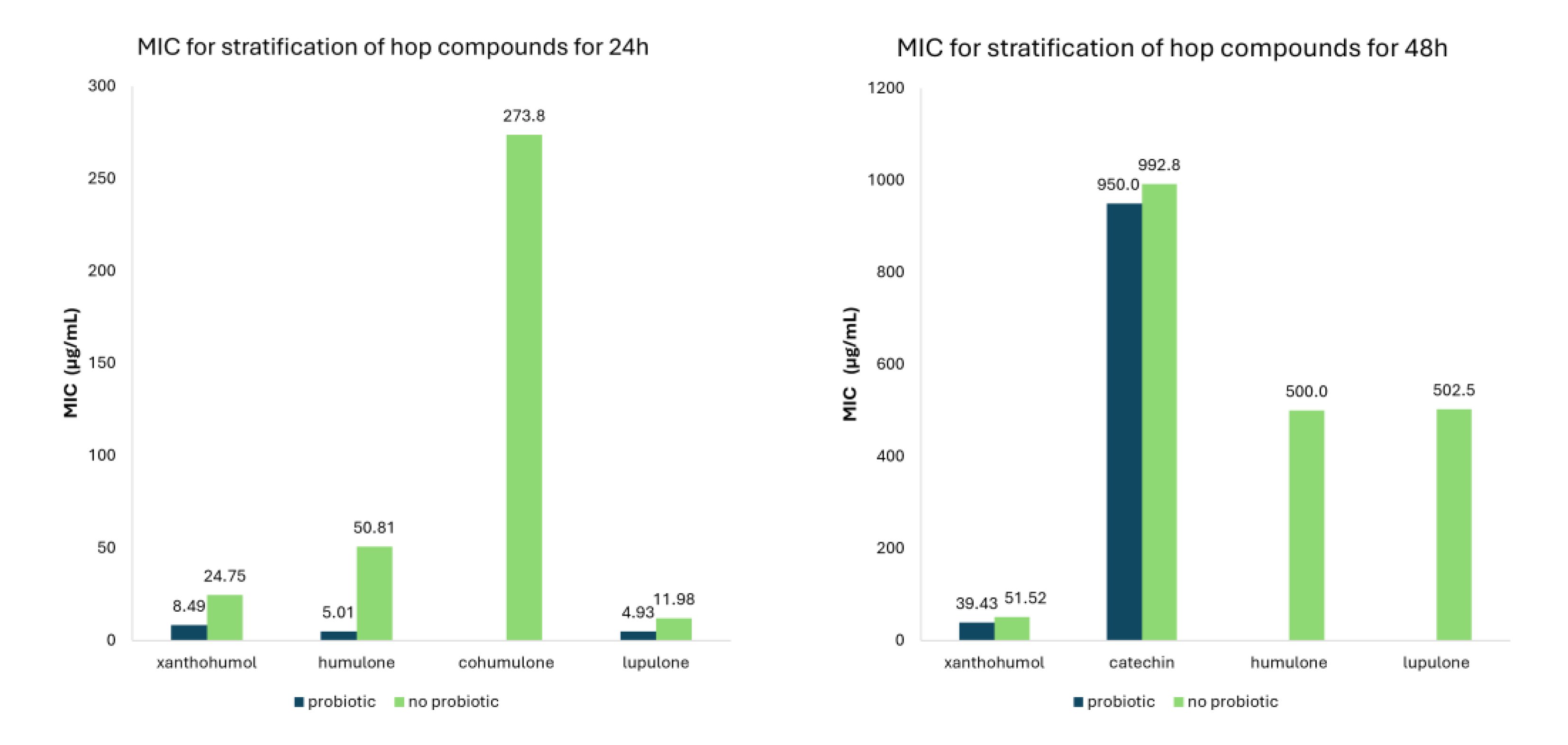

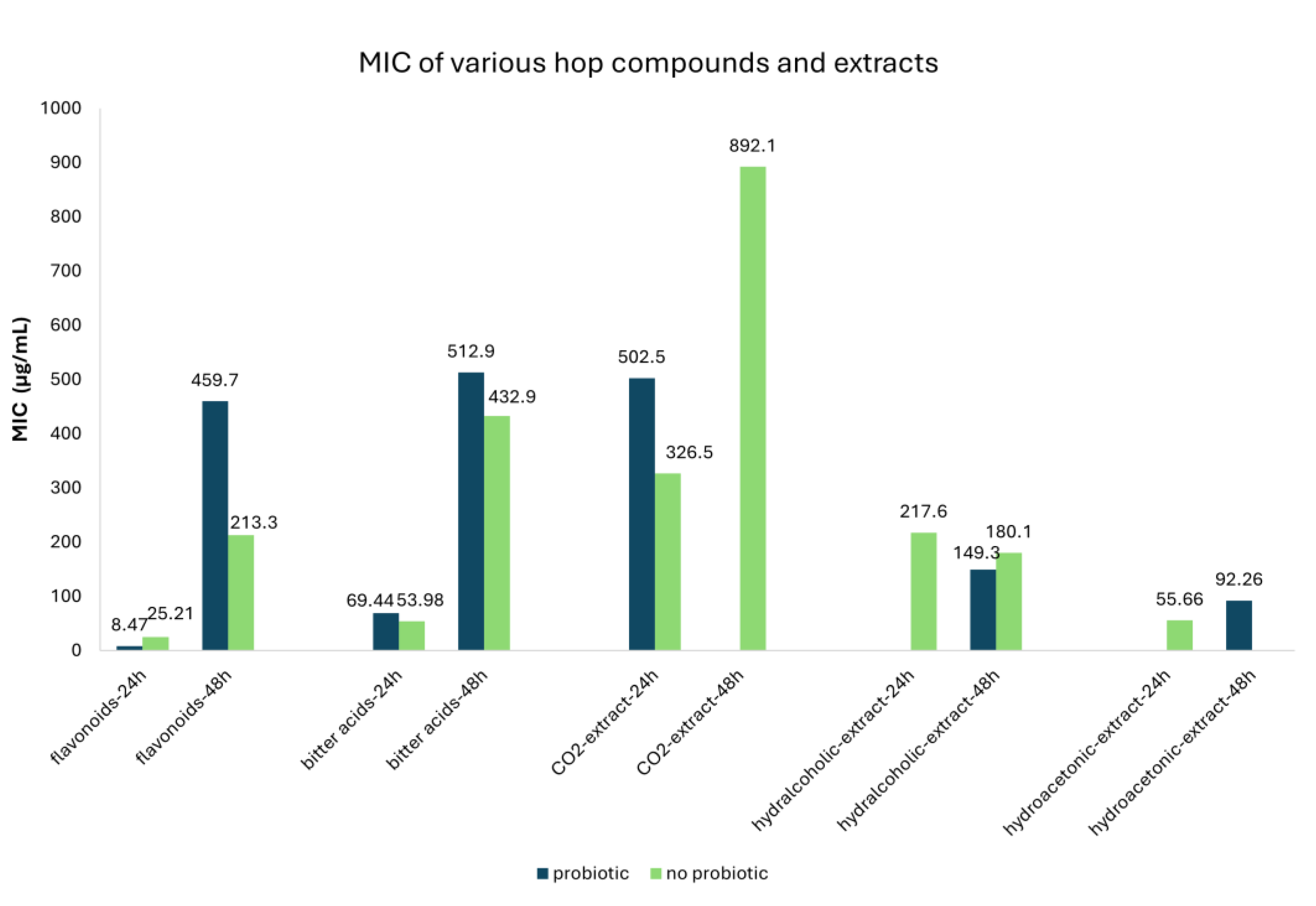

3.5. Meta-Analysis of MIC Values of Hop Compounds and Extracts for Probiotic and Non-Probiotic Microorganisms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| SFE | Supercritical fluid extracts |

References

- Bocquet, L.; Sahpaz, S.; Hilbert, J. L.; Rambaud, C.; Rivière, C. Humulus Lupulus L., a Very Popular Beer Ingredient and Medicinal Plant: Overview of Its Phytochemistry, Its Bioactivity, and Its Biotechnology. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 1047–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, R. L.; Padgitt-Cobb, L. K.; Townsend, M. S.; Henning, J. A. Gene Expression for Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis in Hop (Humulus Lupulus L.) Leaf Lupulin Glands Exposed to Heat and Low-Water Stress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostálek, P.; Karabín, M.; Jelínek, L. Hop Phytochemicals and Their Potential Role in Metabolic Syndrome Prevention and Therapy. Molecules 2017, 22, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Yuan, A.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Xie, D.; Zhang, H.; Luo, W.; Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Nie, C.; Zhang, H. Chemical Constituents and Bioactivities of Hops ( Humulus Lupulus L.) and Their Effects on Beer-related Microorganisms. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez Hrnčič, M.; Španinger, E.; Košir, I. J.; Knez, Ž.; Bren, U. Hop Compounds: Extraction Techniques, Chemical Analyses, Antioxidative, Antimicrobial, and Anticarcinogenic Effects. Nutrients 2019, 11, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannusch, V. B.; Viebahn, L.; Briesen, H.; Minceva, M. Predicting the Essential Oil Composition in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extracts from Hop Pellets Using Mathematical Modeling. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyres, G.; Dufour, J.-P. Hop Essential Oil: Analysis, Chemical Composition and Odor Characteristics. In Beer in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier, 2009; pp 239–254. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, K.; Gervasi, F. An Updated Review of the Genus Humulus: A Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds for Health and Disease Prevention. Plants 2022, 11, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condón, S.; García, M. L.; Otero, A.; Sala, F. J. Effect of Culture Age, Pre-incubation at Low Temperature and pH on the Thermal Resistance of Aeromonas Hydrophila. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1992, 72, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhäuser, C. Beer Constituents as Potential Cancer Chemopreventive Agents. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 1941–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J. L.; Dunlap, T. L.; Hajirahimkhan, A.; Mbachu, O.; Chen, S.-N.; Chadwick, L.; Nikolic, D.; Van Breemen, R. B.; Pauli, G. F.; Dietz, B. M. The Multiple Biological Targets of Hops and Bioactive Compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodino, S.; Butu, A.; Negoescu, C.; Petrache, P.; Condei, R.; Nicolae, I.; Cornea, C. P. Antimicrobial Activity of Humulus Lupulus Extract. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 185, S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, N.; Biehler, K.; Schwabe, K.; Haarhaus, B.; Quirin, K.-W.; Frank, U.; Schempp, C. M.; Wölfle, U. Hop Extract Acts as an Antioxidant with Antimicrobial Effects against Propionibacterium Acnes and Staphylococcus Aureus. Molecules 2019, 24, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J. F.; Page, J. E. Xanthohumol and Related Prenylflavonoids from Hops and Beer: To Your Good Health! Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackett, D. L.; Rosenberg, W. M. C.; Gray, J. A. M.; Haynes, R. B.; Richardson, W. S. Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn’t. BMJ 1996, 312, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaefthimiou, M.; Kontou, P. I.; Bagos, P. G.; Braliou, G. G. Antioxidant Activity of Leaf Extracts from Stevia Rebaudiana Bertoni Exerts Attenuating Effect on Diseased Experimental Rats: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefthimiou, M.; Kontou, P. I.; Bagos, P. G.; Braliou, G. G. Integration of Antioxidant Activity Assays Data of Stevia Leaf Extracts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D. G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; McDonald, S.; Clarke, M. J.; Egger, M. Grey Literature in Meta-analyses of Randomized Trials of Health Care Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 2007, MR000010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T. A.; Barbui, C.; Cipriani, A.; Brambilla, P.; Watanabe, N. Imputing Missing Standard Deviations in Meta-Analyses Can Provide Accurate Results. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006, 59, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-Analysis in Clinical Trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stata User’s Guide Release 13; StataCorp LP: College Station, Tex., 2013.

- Kramer, B.; Thielmann, J.; Hickisch, A.; Muranyi, P.; Wunderlich, J.; Hauser, C. Antimicrobial Activity of Hop Extracts against Foodborne Pathogens for Meat Applications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 118, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermak, P.; Olsovska, J.; Mikyska, A.; Dusek, M.; Kadleckova, Z.; Vanicek, J.; Nyc, O.; Sigler, K.; Bostikova, V.; Bostik, P. Strong Antimicrobial Activity of Xanthohumol and Other Derivatives from Hops (Humulus Lupulus L.) on Gut Anaerobic Bacteria. APMIS Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 2017, 125, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanova, K.; Röderova, M.; Kolar, M.; Langova, K.; Dusek, M.; Jost, P.; Kubelkova, K.; Bostik, P.; Olsovska, J. Antibiofilm Activity of Bioactive Hop Compounds Humulone, Lupulone and Xanthohumol toward Susceptible and Resistant Staphylococci. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A. E.; Yu, R. R.; Lee, O. A.; Price, S.; Haas, G. J.; Johnson, E. A. Antimicrobial Activity of Hop Extracts against Listeria Monocytogenes in Media and in Food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1996, 33, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek, K.; Tyśkiewicz, K.; Miazga-Karska, M.; Dębczak, A.; Rój, E.; Ginalska, G. Bioactive Compounds Obtained from Polish “Marynka” Hop Variety Using Efficient Two-Step Supercritical Fluid Extraction and Comparison of Their Antibacterial, Cytotoxic, and Anti-Proliferative Activities In Vitro. Molecules 2021, 26, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, L.; Sahpaz, S.; Bonneau, N.; Beaufay, C.; Mahieux, S.; Samaillie, J.; Roumy, V.; Jacquin, J.; Bordage, S.; Hennebelle, T.; Chai, F.; Quetin-Leclercq, J.; Neut, C.; Rivière, C. Phenolic Compounds from Humulus Lupulus as Natural Antimicrobial Products: New Weapons in the Fight against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus, Leishmania Mexicana and Trypanosoma Brucei Strains. Mol. Basel Switz. 2019, 24, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, P.; Katta, S.; Andrei, I.; Babu Rao Ambati, V.; Leonida, M.; Haas, G. J. Positive Antibacterial Co-Action between Hop (Humulus Lupulus) Constituents and Selected Antibiotics. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2008, 15, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, C.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M. G. Inhibitory Spectra and Modes of Antimicrobial Action of Gallotannins from Mango Kernels (Mangifera Indica L.). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozalski, M.; Micota, B.; Sadowska, B.; Stochmal, A.; Jedrejek, D.; Wieckowska-Szakiel, M.; Rozalska, B. Antiadherent and Antibiofilm Activity of Humulus Lupulus L. Derived Products: New Pharmacological Properties. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flesar, J.; Havlik, J.; Kloucek, P.; Rada, V.; Titera, D.; Bednar, M.; Stropnicky, M.; Kokoska, L. In Vitro Growth-Inhibitory Effect of Plant-Derived Extracts and Compounds against Paenibacillus Larvae and Their Acute Oral Toxicity to Adult Honey Bees. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 145, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, K.; Kolar, M.; Langova, K.; Dusek, M.; Mikyska, A.; Bostikova, V.; Bostik, P.; Olsovska, J. Inhibitory Effect of Hop Fractions against Gram-Positive Multi-Resistant Bacteria. A Pilot Study. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czechoslov. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavya, M. L.; Chandu, A. G. S.; Devi, S. S.; Quirin, K.-W.; Pasha, A.; Vijayendra, S. V. N. In-Vitro Evaluation of Antimicrobial and Insect Repellent Potential of Supercritical-Carbon Dioxide (SCF-CO2) Extracts of Selected Botanicals against Stored Product Pests and Foodborne Pathogens. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilna, J.; Vlkova, E.; Krofta, K.; Nesvadba, V.; Rada, V.; Kokoska, L. In Vitro Growth-Inhibitory Effect of Ethanol GRAS Plant and Supercritical CO₂ Hop Extracts on Planktonic Cultures of Oral Pathogenic Microorganisms. Fitoterapia 2015, 105, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalreck, A. F.; Teuber, M. Structural Features Determining the Antibiotic Potencies of Natural and Synthetic Hop Bitter Resins, Their Precursors and Derivatives. Can. J. Microbiol. 1975, 21, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, N. J. L.; Corrêa, J. A. F.; Rigotti, R. T.; da Silva Junior, A. A.; Luciano, F. B. Combination of Natural Antimicrobials for Contamination Control in Ethanol Production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Liang, J.; Shi, Q.; Yuan, P.; Meng, R.; Tang, X.; Yu, L.; Guo, N. Genome-Wide Transcription Analyses in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Treated with Lupulone. Braz. J. Microbiol. Publ. Braz. Soc. Microbiol. 2014, 45, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolenc, Z.; Langerholc, T.; Hostnik, G.; Ocvirk, M.; Štumpf, S.; Pintarič, M.; Košir, I. J.; Čerenak, A.; Garmut, A.; Bren, U. Antimicrobial Properties of Different Hop (Humulus Lupulus) Genotypes. Plants Basel Switz. 2022, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegopoulos, K.; Fountas, D. V.; Andronidou, E.-M.; Bagos, P. G.; Kolovos, P.; Skavdis, G.; Pergantas, P.; Braliou, G. G.; Papageorgiou, A. C.; Grigoriou, M. E. Assessing Genetic Diversity and Population Differentiation in Wild Hop (Humulus Lupulus) from the Region of Central Greece via SNP-NGS Genotyping. Diversity 2023, 15, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, A. K. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 162750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, K. K. K.; Gao, P.; Kang, B.-H. Electron Microscopy Views of Dimorphic Chloroplasts in C4 Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Flavonoid Biosynthesis. A Colorful Model for Genetics, Biochemistry, Cell Biology, and Biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, K.; Konings, W. N. Beer Spoilage Bacteria and Hop Resistance. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 89, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, W. J.; Smith, A. R. Factors Affecting Antibacterial Activity of Hop Compounds and Their Derivatives. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1992, 72, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Saavedra, M.; González de Llano, D.; Moreno-Arribas, M. V. Beer Spoilage Lactic Acid Bacteria from Craft Brewery Microbiota: Microbiological Quality and Food Safety. Food Res. Int. Ott. Ont 2020, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D. S.; Boyer-Chammard, T.; Jarvis, J. N. Emerging Concepts in HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 32, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapari, A.; Braliou, G. G.; Papaefthimiou, M.; Mavriki, H.; Kontou, P. I.; Nikolopoulos, G. K.; Bagos, P. G. Performance of Antigen Detection Tests for SARS-CoV-2: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S. A.; Kontou, P. I.; Bagos, P. G.; Braliou, G. G. Urine-Based Molecular Diagnostic Tests for Leishmaniasis Infection in Human and Canine Populations: A Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2021, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagybákay, N. E.; Syrpas, M.; Vilimaitė, V.; Tamkutė, L.; Pukalskas, A.; Venskutonis, P. R.; Kitrytė, V. Optimized Supercritical CO2 Extraction Enhances the Recovery of Valuable Lipophilic Antioxidants and Other Constituents from Dual-Purpose Hop (Humulus Lupulus L.) Variety Ella. Antioxid. Basel Switz. 2021, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontou, P. I.; Braliou, G. G.; Dimou, N. L.; Nikolopoulos, G.; Bagos, P. G. Antibody Tests in Detecting SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María Bonilla-Luque, O.; Nunes Silva, B.; Ezzaky, Y.; Possas, A.; Achemchem, F.; Cadavez, V.; Gonzales-Barron, Ú.; Valero, A. Meta-Analysis of Antimicrobial Activity of Allium, Ocimum, and Thymus Spp. Confirms Their Promising Application for Increasing Food Safety. Food Res. Int. 2024, 188, 114408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassagne, F.; Samarakoon, T.; Porras, G.; Lyles, J. T.; Dettweiler, M.; Marquez, L.; Salam, A. M.; Shabih, S.; Farrokhi, D. R.; Quave, C. L. A Systematic Review of Plants With Antibacterial Activities: A Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 586548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Jiang, S.; Jia, W.; Guo, T.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Yao, Z. Natural Antimicrobials from Plants: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Year | MIC (μg/mL) | Strain | Type of compounds / extracts | Number of experiments | Time (hours) | Temperature (oC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 6.3 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 12.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1.6 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1.6 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 5000 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 2500 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1250 | Listeria monocytogenes | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 5000 | Listeria monocytogenes | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1250 | Listeria monocytogenes | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 625 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 5000 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 2500 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1250 | Escherichia coli | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 5000 | Escherichia coli | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1250 | Escherichia coli | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 625 | Escherichia coli | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 6.3 | Escherichia coli | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 12.5 | Escherichia coli | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1.6 | Escherichia coli | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1.6 | Escherichia coli | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Escherichia coli | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Salmonella enterica | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Salmonella enterica | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 5000 | Salmonella enterica | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 2500 | Salmonella enterica | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1250 | Salmonella enterica | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 5000 | Salmonella enterica | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 1250 | Salmonella enterica | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 625 | Salmonella enterica | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Salmonella enterica | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kramer et al. [23] | 2015 | 200 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 3.1 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 4.65 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 3.1 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 3.1 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 9.375 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 9.375 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 6.25 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Weber et al. [13] | 2019 | 12.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 160 | Bacteroides fragilis | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 680 | Bacteroides fragilis | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 900 | Bacteroides fragilis | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1540 | Bacteroides fragilis | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1150 | Bacteroides fragilis | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 260 | Bacteroides fragilis | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 680 | Bacteroides fragilis | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 840 | Clostridium perfringens | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1370 | Clostridium perfringens | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1190 | Clostridium perfringens | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 680 | Clostridium perfringens | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1230 | Clostridium perfringens | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 320 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 770 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 510 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 510 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 580 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 770 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 510 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 510 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 340 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 640 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 430 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 340 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 680 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 2040 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 510 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 300 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 680 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 510 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 850 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 680 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 1020 | Clostridium difficile | α-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 190 | Bacteroides fragilis | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 340 | Bacteroides fragilis | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 320 | Bacteroides fragilis | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 430 | Bacteroides fragilis | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 260 | Bacteroides fragilis | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 220 | Bacteroides fragilis | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 50 | Bacteroides fragilis | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 170 | Clostridium perfringens | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 210 | Clostridium perfringens | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 260 | Clostridium perfringens | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 200 | Clostridium perfringens | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 150 | Clostridium perfringens | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 24 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 80 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 48 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 21 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 72 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 21 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 68 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 21 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 27 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 36 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 96 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 40 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 80 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 19 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 27 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 43 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 27 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 9 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 24 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 12 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 53 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 48 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 24 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 12 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 48 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 28 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 48 | Clostridium difficile | β-acids/bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 15 | Bacteroides fragilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 56 | Bacteroides fragilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 29 | Bacteroides fragilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 48 | Bacteroides fragilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 44 | Bacteroides fragilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 28 | Bacteroides fragilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 56 | Bacteroides fragilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 10 | Clostridium perfringens | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 28 | Clostridium perfringens | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium perfringens | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 40 | Clostridium perfringens | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 53 | Clostridium perfringens | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 85 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 85 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 107 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 85 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 53 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 43 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 75 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 85 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 43 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 32 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 43 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 64 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Cermak et al. [24] | 2017 | 53 | Clostridium difficile | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 7.5 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Humulone /α-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 30 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Humulone /α-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 15 | Staphylococcus capitis | Humulone /α-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 15 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone /α-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 15 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone /α-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 0.5 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Lupulone /β-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 4 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Lupulone /β-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 0.5 | Staphylococcus capitis | Lupulone /β-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 0.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 0.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 2 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 2 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 2 | Staphylococcus capitis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 2 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [25] | 2018 | 4 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 24 | 37 | |

| Larsona et al. [26] | 1996 | 300 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 24 | 37 | |

| Larsona et al. [26] | 1996 | 300 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Larsona et al. [26] | 1996 | 10 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Larsona et al. [26] | 1996 | 10 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.195 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.195 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.098 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.098 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.391 | Streptococcus mutans | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.391 | Streptococcus mutans | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.781 | Streptococcus sanguinis | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.781 | Streptococcus sanguinis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 15.625 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 62.5 | Propionibacterium acnes | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 15.625 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 31.25 | Propionibacterium acnes | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.195 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.098 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.391 | Streptococcus mutans | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 0.781 | Streptococcus sanguinis | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 15.625 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Klimek et al. [27] | 2021 | 15.625 | Propionibacterium acnes | CO2-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Corynebacterium | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Enterococcus faecalis | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 156 | Enterococcus sp. | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Mycobacterium smegmatis | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 98 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 156 | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus warneri | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Streptococcus agalactiae | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 78 | Streptococcus agalactiae | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 625 | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 625 | Staphylococcus warneri | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 625 | Acinetobacter baumannii | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 625 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 625 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 625 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 156 | Candida albicans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Candida albicans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 625 | Candida albicans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 2.23 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 2.32 | Staphylococcus aureus | Desmethylxanthohumol/ chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 0.53 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids /bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 9.8 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 9.8 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 9.8 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 19.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus aureus | Desmethylxanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 19.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | Desmethylxanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus aureus | Desmethylxanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus aureus | Desmethylxanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 156 | Staphylococcus aureus | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 313 | Staphylococcus aureus | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 313 | Staphylococcus aureus | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 313 | Staphylococcus aureus | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 78 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 156 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 156 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 156 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus aureus | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 78 | Staphylococcus aureus | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 39 | Staphylococcus aureus | Colupulone /β-acids/ bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 78 | Staphylococcus aureus | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 1.2 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 0.6 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 0.6 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Bocquet et al. [28] | 2019 | 1.2 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Bacillus subtilis | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 5 | Bacillus megaterium | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 30 | Streptococcus salivarius | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 1 | Bacillus subtilis | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Bacillus megaterium | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 5 | Streptococcus salivarius | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 1 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 1 | Bacillus subtilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Bacillus megaterium | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Streptococcus salivarius | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 1 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Bacillus subtilis | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Bacillus subtilis | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Bacillus megaterium | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 100 | Streptococcus salivarius | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Bacillus subtilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Bacillus megaterium | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 30 | Streptococcus salivarius | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Bacillus subtilis | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Bacillus subtilis | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Bacillus megaterium | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 100 | Streptococcus salivarius | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 3 | Streptococcus saprophyticus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Bacillus subtilis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 10 | Bacillus megaterium | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| Natarajana et al. [29] | 2008 | 30 | Streptococcus salivarius | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 600 | Bacillus subtilis | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1300 | Bacillus subtilis | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Bacillus subtilis | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 100 | Bacillus cereus | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 100 | Staphylococcus aureus | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 500 | Listeria monocytogenes | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Pediococcus acidilaactici | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Lactococcus lactis | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 300 | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 100 | Staphylococcus warneri | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Lactobacillus plantarum | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Enterococcus faecalis | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 42 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 600 | Campylobacter jejuni | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Mucor plumbeus | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 1700 | Aspergillus niger | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 25 |

| Engels et al. [30] | 2011 | 26.8 | Penicillium spp | Catechin /flavonols / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 31 | Streptococcus aureus | hydralcoholic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 125 | Streptococcus aureus | hydralcoholic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 31 | Streptococcus aureus | hydralcoholic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 62 | Enterococcus faecalis | hydralcoholic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 15 | Streptococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 125 | Streptococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 93.5 | Streptococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 62 | Enterococcus faecalis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 2000 | Streptococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 1000 | Streptococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 2000 | Streptococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 2000 | Enterococcus faecalis | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 31 | Streptococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 125 | Streptococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 31 | Streptococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Rozalski et al. [31] | 2013 | 62 | Enterococcus faecalis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Flesar et al. [32] | 2010 | 2 | Paenibacillus larvae | organic-ethanolic extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Flesar et al. [32] | 2010 | 3 | Paenibacillus larvae | organic extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Flesar et al. [32] | 2010 | 128 | Paenibacillus larvae | Catechin/flavonols/ flavonoids |

4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 30 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 60 | Enterococcus faecalis | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 60 | Staphylococcus aureus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 60 | Enterococcus faecalis | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 30 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 250 | Candida albicans | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 250 | Candida krusei | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 1.000 | Candida tropicalis | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 500 | Candida parapsilosis | Humulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 0.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 1.5 | Enterococcus faecalis | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 15 | Enterococcus faecalis | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 1 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 500 | Candida albicans | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 500 | Candida krusei | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 1.000 | Candida parapsilosis | Lupulone /β-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 4 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 7.5 | Enterococcus faecalis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 4 | Staphylococcus aureus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 7.5 | Enterococcus faecalis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 7.5 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 60 | Candida albicans | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 60 | Candida krusei | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 30 | Candida tropicalis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 7.5 | Candida parapsilosis | Xanthohumol / chalcones / flavonoids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 7.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 60 | Enterococcus faecalis | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 7.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 30 | Enterococcus faecalis | CO2-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 15 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 250 | Candida albicans | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 250 | Candida krusei | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 1.000 | Candida tropicalis | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Bogdanova et al. [33] | 2018 | 500 | Candida parapsilosis | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 25 |

| Bhavya et al. [34] | 2020 | 64 | Staphylococcus aureus | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 25 |

| Bhavya et al. [34] | 2020 | 32 | Listeria monocytogenes | CO2-extract | 4 | 48 | 25 |

| Bhavya et al. [34] | 2020 | 32 | Bacillus subtilis | CO2-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Bifidobacterium dentium | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Bifidobacterium dentium | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Bifidobacterium dentium | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Bifidobacterium dentium | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Bifidobacterium dentium | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Bifidobacterium dentium | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Bifidobacterium longum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Bifidobacterium longum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Bifidobacterium longum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Bifidobacterium longum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Bifidobacterium longum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Bifidobacterium longum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Lactobacillus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Lactobacillus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Lactobacillus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Lactobacillus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Lactobacillus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Lactobacillus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Streptococcus mutans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Streptococcus mutans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Streptococcus mutans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Streptococcus mutans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Streptococcus mutans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Streptococcus mutans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Streptococcus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 16 | Streptococcus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 32 | Streptococcus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 32 | Streptococcus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 32 | Streptococcus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 32 | Streptococcus salivarius | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Streptococcus sobrinus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 16 | Streptococcus sobrinus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Streptococcus sobrinus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Streptococcus sobrinus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Streptococcus sobrinus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Streptococcus sobrinus | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 512 | Eikenella corrodens | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 512 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 512 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 512 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 64 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 128 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Candida albicans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 256 | Candida albicans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 512 | Candida albicans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 48 | 37 |

| Pilna et al. [35] | 2015 | 512 | Candida albicans | hydralcoholic-extract | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Schmalreck et al. [36] | 1974 | 1.8 | Bacillus subtilis | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Schmalreck et al. [36] | 1974 | 9 | Bacillus subtilis | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Schmalreck et al. [36] | 1974 | 11 | Bacillus subtilis | Humulone/ α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Schmalreck et al. [36] | 1974 | 22 | Bacillus subtilis | Cohumulone / α-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Schmalreck et al. [36] | 1974 | 30 | Bacillus subtilis | Colupulone/ β-acids / bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Schmalreck et al. [36] | 1974 | 75 | Bacillus subtilis | Isohumulone /α-acids/bitter acids | 3 | 24 | 37 |

| Schmalreck et al. [36] | 1974 | 920 | Bacillus subtilis | Colupulone/ β-acids / bitter acids | 6 | 24 | 37 |

| Maia et al. [37] | 2019 | 1.000 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | CO2-extract | 6 | 24 | 37 |

| Maia et al. [37] | 2019 | 5 | Lactobacillus fermentum | CO2-extract | 6 | 24 | 37 |

| Maia et al. [37] | 2019 | 5 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | CO2-extract | 2 | 48 | 37 |

| Wei et al. [38] | 2014 | 10 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Humulone/ α-acids / bitter acids | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 15.6 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 19.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 15.6 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 9.8 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 19.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 19.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 19.5 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 27.3 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 31.3 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 31.3 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 15.6 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 54.7 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 250 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 24 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 250 | Staphylococcus aureus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 62.5 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 62.5 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 83.3 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 62.5 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 35 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 104.2 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 83.3 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 104.2 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 62.5 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 125 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 208.3 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 104.2 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 83.3 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 62.5 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Kolenc et al. [39] | 2022 | 83.3 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | hydroacetonic-extract | 4 | 48 | 37 |

| Compound | Time (hours) | Strain | MIC (μg/mL) | 95% CI | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | 24 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1.37 | 0.12-2.61 | 3 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 13.61 | 6.41-20.81 | 15 | ||

| Bacillus subtilis | 7.00 | 1.12-12.88 | 3 | ||

| Bacillus megaterium | 10.00 | 9.20-10.80 | 3 | ||

| Streptococcus salivarius | 23.33 | 10.27-36.40 | 3 | ||

| Streptococcus saprophyticus | 2.33 | 1.03-3.64 | 3 | ||

| Streptococcus aureus | 70.08 | 29.81-110.36 | 6 | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 62.00 | 61.31-62.69 | 2 | ||

| 48 | Staphylococcus aureus | 5.17 | 3.14-7.20 | 3 | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 129.68 | 0.00-353.71 | 4 | ||

| Escherichia coli | 200.0 | 199.43-200.57 | 3 | ||

| Salmonella enterica | 200.0 | 199.43-200.57 | 3 | ||

| Bacteroides fragilis | 39.43 | 27.76-51.06 | 7 | ||

| Clostridium perfringens | 32.60 | 18.72-46.48 | 5 | ||

| Clostridium difficile | 59.04 | 51.64-66.43 | 28 | ||

| Propionibacterium acnes | 46.88 | 16.25-77.50 | 2 | ||

| Bacillus subtilis | 1200.0 | 569.96-1830.0 | 3 | ||

| Pseudomonas fluroescens | 1700.0 | 1699.2-1700.8 | 2 | ||

| Bitter acids | 24 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 10.50 | 0.00-23.54 | 4 |

| Staphylococcus capitis | 7.75 | 0.00-21.96 | 2 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 80.07 | 40.13-120.0 | 25 | ||

| Bacillus subtilis | 90.25 | 0.00-255.52 | 12 | ||

| Bacillus megaterium | 7.00 | 3.51-10.49 | 4 | ||

| Streptococcus salivarius | 58.75 | 11.01-106.49 | 4 | ||

| Streptococcus saprophyticus | 3.83 | 1.71-5.94 | 6 | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 45.00 | 15.60-74.4 | 3 | ||

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 15.50 | 0.00-43.92 | 2 | ||

| 48 | Bacteroides fragilis | 512.90 | 287.91-737.80 | 14 | |

| Clostridium perfringens | 630.0 | 323.01-936.99 | 10 | ||

| Clostridium difficile | 388.0 | 274.54-501.46 | 56 | ||

| Candida albicans | 375.0 | 130.01-620.0 | 2 | ||

| Candida krusei | 375.0 | 130.01-620.0 | 2 | ||

| Candida parapsilosis | 750.0 | 260.01-1240.0 | 2 | ||

| CO2-extract | 24 | Propionibacterium acnes | 3.49 | 2.73-4.25 | 4 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 6.32 | 2.21-10.43 | 6 | ||

| Listeria monocytogenes | 10.00 | 9.31-10.69 | 2 | ||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 0.10 | 0.00-0.90 | 2 | ||

| Streptococcus aureus | 1666.7 | 1013.4-2320.0 | 3 | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 696.67 | 0.00-1974.0 | 3 | ||

| 48 | Staphylococcus aureus | 46.43 | 0.00-99.10 | 7 | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 37.19 | 0.00-90.93 | 7 | ||

| Escherichia coli | 2604.2 | 1041.29-4167.1 | 6 | ||

| Salmonella enterica | 2604.2 | 1041.29-4167.1 | 6 | ||

| Streptococcus mutans | 0.39 | 0.00-1.19 | 2 | ||

| Streptococcus sanguinis | 0.78 | 0.00-1.58 | 2 | ||

| Propionibacterium acnes | 15.63 | 15.06-16.19 | 4 | ||

| Hydralcoholic-extract | 24 | Enterococcus faecalis | 50.50 | 27.96-73.04 | 2 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 39.00 | 38.20-39.80 | 2 | ||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 68.50 | 10.68-126.32 | 2 | ||

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis | 390.50 | 0.00-850.11 | 2 | ||

| Staphylococcus warneri | 332.0 | 0.00-906.27 | 2 | ||

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 58.50 | 20.28-96,18 | 2 | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 625.0 | 624.20-625.80 | 2 | ||

| Candida albicans | 273.33 | 0.00-624.26 | 3 | ||

| Streptococcus aureus | 62.33 | 0.92-123,75 | 3 | ||

| 48 | Bifidobacteriumm dentium | 213.33 | 160.44-266.22 | 6 | |

| Bifidobacterium longum | 96.00 | 67.95-124.05 | 6 | ||

| Lactobacillus salivarius | 138.67 | 88.32-189.02 | 6 | ||

| Streptococcus mutans | 106.67 | 80.22-133,11 | 6 | ||

| Streptococcus salivarius | 34.67 | 22.08-47.25 | 6 | ||

| Streptococcus sobrinus | 66.67 | 38.14-95,20 | 6 | ||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 250.67 | 154.91-346.42 | 12 | ||

| Candida albicans | 384.0 | 239.16-528.84 | 4 | ||

| Hydroacetonic-extract | 24 | Staphylococcus aureus | 55.66 | 12.15-99.16 | 14 |

| 48 | Lactobacillus acidophilus | 92.26 | 71.86-112.66 | 14 |

| Class of compounds | Compound | Time (hours) | Strain | MIC (μg/mL) | 95% CI | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Xanthohumol | 24 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1.37 | 0.12-2.61 | 3 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 6.53 | 3.05-10.01 | 10 | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | 7.00 | 1.12-12.88 | 3 | |||

| Bacillus megaterium | 10.00 | 9.20-10.80 | 3 | |||

| Streptococcus salivarius | 23.33 | 10.27-36.40 | 3 | |||

| Streptococcus saprophyticus | 2.33 | 1.03-3.64 | 3 | |||

| Streptococcus aureus | 70.08 | 29.81-110.36 | 6 | |||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 62.00 | 61.31-62.96 | 2 | |||

| 48 | Bacteroides fragilis | 39.43 | 27.80-51.06 | 7 | ||

| Clostridium perfringens | 32.60 | 18.72-46.48 | 5 | |||

| Clostridium difficile | 59.04 | 51.64-66.43 | 28 | |||

| Propionibacterium acnes | 46.88 | 16.25-77.50 | 2 | |||

| Catechin | 48 | Bacillus subtilis | 1200.0 | 569.96-1830.0 | 3 | |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | 1700.0 | 1698.9-1701.1 | 2 | |||

| Bitter acids | Humulone | 24 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 18.75 | 0.00-40.80 | 2 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 83.25 | 39.87-126.63 | 8 | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | 5.01 | 0.33-9.69 | 4 | |||

| Streptococcus saprophyticus | 5.31 | 1.20-9.42 | 3 | |||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 60.00 | 59.31-60.69 | 2 | |||

| Cohumulone | 24 | Staphylococcus aureus | 273.75 | 196.82-350.68 | 4 | |

| α-acids | 48 | Bacteroides fragilis | 767.14 | 408.98-1125.3 | 7 | |

| Clostridium perfringens | 1062.0 | 808.46-1315.5 | 5 | |||

| Clostridium difficile | 737.14 | 604.15-870.14 | 28 | |||

| Lupulone | 24 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2.25 | 0.00-5.68 | 2 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0.76 | 0.38-1.15 | 8 | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | 2.33 | 1.03-3.64 | 3 | |||

| Bacillus megaterium | 7.67 | 3.093-12.24 | 3 | |||

| Streptococcus salivarius | 68.33 | 6.27-130.40 | 3 | |||

| Streptococcus saprophyticus | 2.33 | 1.03-3.64 | 3 | |||

| β-acids | 48 | Bacteroides fragilis | 258.57 | 168.10-349.04 | 7 | |

| Clostridium perfringens | 198.00 | 161.12-234.88 | 5 | |||

| Clostridium difficile | 38.39 | 39.40-130.10 | 28 |

| Class of Compounds | Compound | Time (hours) | Food spoilage/ Non-food spoilage | MIC (μg/ml) | 95% CI | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | All Flavonoids | 24 | Food spoilage | 22.81 | 11.54-34.08 | 33 |

| Non-food spoilage | 21.68 | 0.00-47.71 | 6 | |||

| 48 | Food spoilage | 242.25 | 9.61-474.88 | 26 | ||

| Non-food spoilage | 263.28 | 130.45-396.11 | 48 | |||

| Xanthohumol | 24 | Food spoilage | 21.92 | 9.02-34.83 | 28 | |

| Non-food spoilage | 21.68 | 0.00-47.71 | 6 | |||

| 48 | Food spoilage | 23.46 | 8.76-38.15 | 7 | ||

| Non-food spoilage | 54.32 | 48.10-60.54 | 40 | |||

| Catechin | 48 | Food spoilage | 700.0 | 271.78-1128.2 | 7 | |

| Non-food spoilage | 1192.0 | 658.25-1725.8 | 9 | |||

| Bitter acids | All Bitter acids | 24 | Food spoilage | 66.09 | 3.23-128.59 | 51 |

| Non-food spoilage | 20.32 | 6.64-34.0 | 11 | |||

| 48 | Food spoilage | 573.64 | 277.54-869.74 | 11 | ||

| Non-food spoilage | 427.38 | 332.38-522.01 | 77 | |||

| Humulone | 24 | Food spoilage | 43.35 | 20.31-66.39 | 17 | |

| Non-food spoilage | 33.75 | 15.96-51.55 | 6 | |||

| 48 | Non-food spoilage | 500.0 | 153.52-846.48 | 4 | ||

| Cohumulone | 24 | Food spoilage | 273.75 | 196.82-350.68 | 4 | |

| Lupulone | 24 | Food spoilage | 12.40 | 2.66-22.14 | 20 | |

| Non-food spoilage | 4.20 | 0.00-9.97 | 5 | |||

| 48 | Non-food spoilage | 666.67 | 340.01-993.33 | 3 | ||

| CO2-extract | 24 | Food spoilage | 421.91 | 0.95-842.87 | 12 | |

| Non-food spoilage | 260.35 | 0.00-625.64 | 12 | |||

| 48 | Food spoilage | 1028.1 | 448.06-1608.1 | 31 | ||

| Non-food spoilage | 257.81 | 10.61-505.01 | 8 | |||

| Hydralcoholic-extract | 24 | Food spoilage | 52.65 | 28.39-76.86 | 8 | |

| Non-food spoilage | 290.94 | 163.21-418.68 | 18 | |||

| 48 | Food spoilage | 86.67 | 64.58-108.75 | 24 | ||

| Non-food spoilage | 238.35 | 180.99-295.71 | 29 | |||

| Hydroacetonic-extract | 24 | Food spoilage | 55.66 | 12.15-99.16 | 14 | |

| 48 | Food spoilage | 92.26 | 71.86-112.66 | 14 |

| Class of Compounds | Compound | Time (hours) | Probiotic | MIC (μg/mL) | 95% CI | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | All Flavonoids | 24 | No probiotic | 25.21 | 12.67-37.74 | 33 |

| Probiotic | 8.47 | 4.70-12.30 | 6 | |||

| 48 | No probiotic | 213.28 | 110.83-315.72 | 62 | ||

| Probiotic | 459.69 | 85.84-833.55 | 13 | |||

| Xanthohumol | 24 | No probiotic | 24.75 | 10.17-39.33 | 28 | |

| Probiotic | 8.49 | 4.70-12.27 | 6 | |||

| 48 | No probiotic | 51.52 | 44.42-56.11 | 40 | ||

| Probiotic | 39.43 | 27.79-51.06 | 7 | |||

| Catechin | 48 | No probiotic | 992.8 | 564.73-1420.9 | 10 | |

| Probiotic | 950.0 | 428.99-1471.0 | 6 | |||

| Bitter acids | All Bitter acids | 24 | No probiotic | 53.98 | 30.39-77.57 | 46 |

| Probiotic | 69.44 | 0.00-209.31 | 16 | |||

| 48 | No probiotic | 432.95 | 354.94-535.50 | 74 | ||

| Probiotic | 512.86 | 287.91-737.8 | 14 | |||

| Humulone | 24 | No probiotic | 50.81 | 27.03-74.58 | 18 | |

| Probiotic | 5.01 | 0.97-9.05 | 5 | |||

| 48 | No probiotic | 500.0 | 153.52-846.48 | 4 | ||

| Cohumulone | 24 | No probiotic | 273.75 | 196.82-350.68 | 3 | |

| Lupulone | 24 | No probiotic | 11.98 | 0.71-23.25 | 20 | |

| Probiotic | 4.93 | 2.71-7.15 | 6 | |||

| 48 | No probiotic | 502.5 | 140.19-846.81 | 4 | ||

| CO2-extract | 24 | No probiotic | 326.46 | 14.29-638.63 | 22 | |

| Probiotic | 502.5 | 0.00-1477.6 | 2 | |||

| 48 | No probiotic | 892.11 | 385.11-1399.1 | 38 | ||

| Hydralcoholic-extract | 24 | No probiotic | 217.62 | 120.96-314.27 | 26 | |

| 48 | No probiotic | 180.11 | 124.26-235.97 | 35 | ||

| Probiotic | 149.33 | 115.7-182.97 | 18 | |||

| Hydroacetonic-extract | 24 | No probiotic | 55.66 | 12.15-99.16 | 14 | |

| 48 | Probiotic | 92.26 | 71.86-112.66 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).