Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

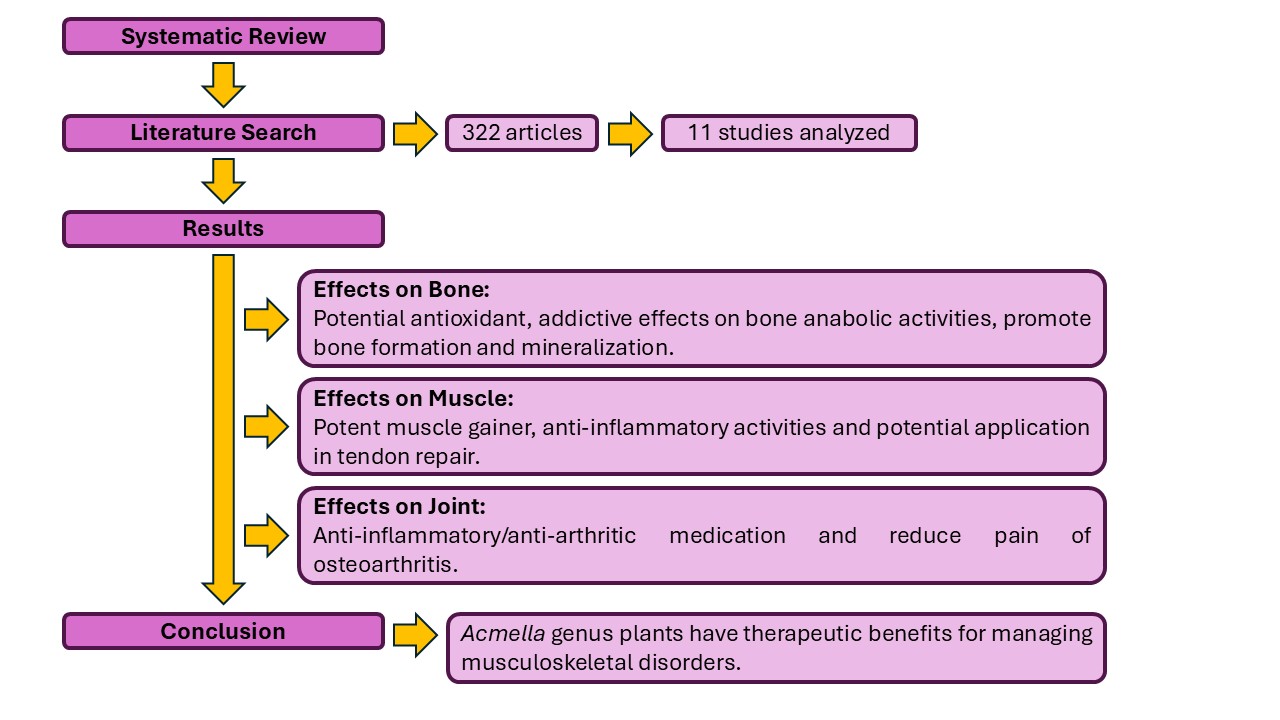

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

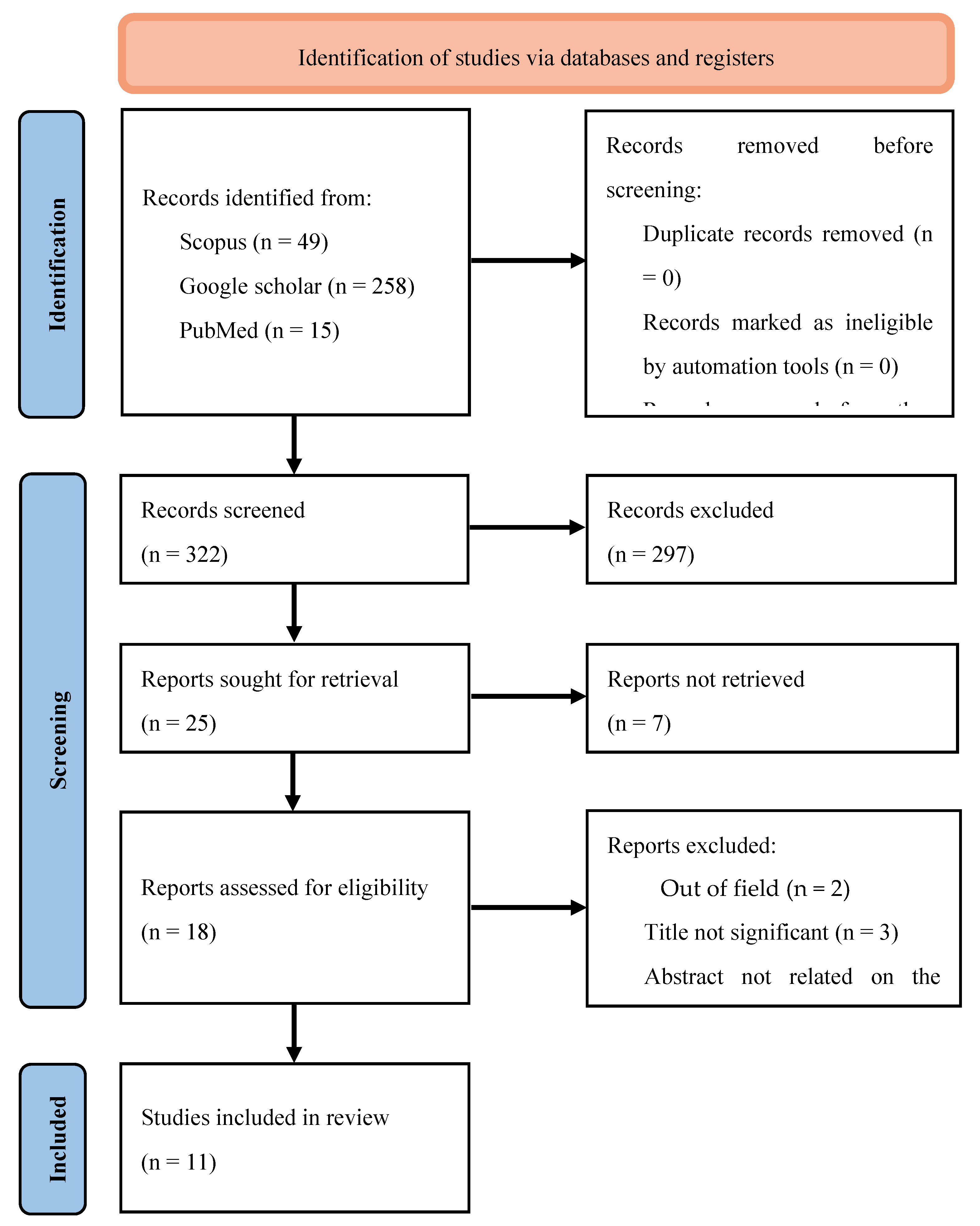

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility of Research Articles

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

- Summarizing preclinical findings related to mechanisms affecting inflammation, bone formation, and joint health.

- Assessing clinical evidence with a focus on key musculoskeletal outcomes, such as pain reduction, decreased joint inflammation, and functional improvement.

- Investigating shared mechanisms of action observed in both clinical and preclinical studies, particularly the effects of compounds like spilanthol on pathways such as nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κ), Wnt/β-catenin, and others involved in bone metabolism.

2.6. Handling Missing Data

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Evidence

3.1.1. Effects on Bone

3.1.2. Effects on Muscle

3.1.3. Effects on Joint

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Competing Interests

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| MSD | Musculoskeletal disorders |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison/Comparator, Outcomes, and Study |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| SYRCLE | Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| MC3T3-E1 cells | Murine calvarial pre-osteoblast cell line |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| MUAC | Mid upper arm circumference |

| CC | Chest circumference |

| TC | Thigh circumference |

| VSMC | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| CFA | Carrageenan and Freund’s Complete Adjuvant |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| VAS | Visual analog scale |

| WOMAC | Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis |

| SF-36 | 36-Item Short Form Health Survey |

| DEXA | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| Micro-CT | Micro-computed tomography |

| IP | Intraperitoneally |

| GCMS | Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| LCTOFMS | Liquid chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| DPPH | 2,2-ediphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| FRAP | Ferric ion reducing antioxidant potential |

| BW | Body weight |

| SA3X | Spilanthes acmella |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ELSA | Ethanolic extract of leaves of Spilanthes acmella |

| MIO | Monosodium iodate |

| GC/MS | Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

References

- Breitling, R.; Takano, E. Synthetic biology advances for pharmaceutical production. Current opinion in biotechnology 2015, 35, 46-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.004.

- Buenz; Eric, J.; et al. The Ethnopharmacologic Contribution to Bioprospecting Natural Products. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology 2018, 58, 509-530. [CrossRef]

- [Internet] World Health Organization. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy: 2014-2023. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/92455.

- Smith, E.; Hoy, D.G.; Cross, M.; et al. The global burden of other musculoskeletal disorders: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2014, 73(8), 1462-1469. [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.G.; Smith, E.; Cross, M.; et al. Reflecting on the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions: lessons learnt from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study and the next steps forward. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2015, 74(1), 4–7. [CrossRef]

- Barham, L.; Hodkinson, B. Assessment of quality of life in musculo-skeletal health. Journal of Musculoskeletal Health 2017, 15(3), 123-135. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. The Lancet 2019, 393(10182), 1745-1759. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Izzo, A.A. The plant kingdom as a source of anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer agents. Phytotherapy Research 2000, 14(8), 581-591. [CrossRef]

- Uthpala, T.G.G.; Navaratne, S.B. Acmella oleracea plant; identification, applications and use as an emerging food source – Review. Food Reviews International 2020, 36(8), 795-818. [CrossRef]

- Panyadee, P.; Inta, A. Taxonomy and ethnobotany of Acmella (Asteraceae) in Thailand. Biodiversitas 2022, 23(4), 2177-2186. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Breu, W.; Willer, F.; Wierer, M.; Remiger, P.; Schwenker, G. In Vitro Inhibition of Arachidonate Metabolism by some Alkamides and Prenylated Phenols. Planta medica. 1989 55(6), 566-567. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.C.; Fan, N.C.; Lin, M.H.; Chu, I.R.; Huang, S.J.; Hu, C.Y.; Han, S.Y. Anti-inflammatory effect of spilanthol from Spilanthes acmella on murine macrophage by down-regulating LPS-induced inflammatory mediators. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 2341-2349. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, K.L.; Jadhav, S.K.; Joshi, V. An updated review on medicinal herb genus Spilanthes. Zhong xi yi jie he xue bao. Journal of Chinese integrative medicine 2011, 9(11), 1170-1178. [CrossRef]

- Monroe, D.; Luo, R.; Tran, K.; Richards, K.M.; Barbosa, A.F.; de Carvalho, M.G.; Sabaa-Srur, A.U.O.; Smith, R.E. LC-HRMS and NMR Analysis of Lyophilized Acmella oleracea Capitula, Leaves and Stems. The Natural Products Journal 2016, 6. [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H.; Ball, P. Flowering Plant Families of the World. Firefly Books 2007. ISBN: 9781842461655.

- Dauncey, E.A.; Irving, J.; Allkin, R.; Robinson, N. Common mistakes when using plant names and how to avoid them. European journal of integrative medicine 2016, 8(5), 597-601. [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC health services research 2014, 14, 579. [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Faliva, M.A.; Naso, M.; Peroni, G.; Nichetti, M.; Gasparri, C.; Spadaccini, D.; Iannello, G.; Infantino, V.; Fazia, T.; Bernardinelli, L.; Perna, S. The Use of a New Food-Grade Lecithin Formulation of Highly Standardized Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and Acmella oleracea Extracts for the Treatment of Pain and Inflammation in a Group of Subjects with Moderate Knee Osteoarthritis. Journal of pain research 2020, 13, 761-770. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, N.R.; Mishra, K.G.; Patnaik, N.; Nayak, R. Evaluation of effects of Spilanthes acmella extract on muscle mass and sexual potency in males: A population-based study. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2021 10(11), 4242-4246. [CrossRef]

- Widyowati, R. Alkaline Phosphatase Activity of Graptophylum pictum and Spilanthes acmella Fractions against MC3T3-E1 Cells as Marker of Osteoblast Differentiation Cells. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2011, 3(1), 34-37. ISSN- 0975-1491.

- Abdul Rahim, R.; Jayusman, P.A.; Lim, V.; Ahmad, N.H.; Abdul Hamid, Z.A.; Mohamed, S.M.; Muhammad, N.; Ahmad, F.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Mohamed, N.; Shuid, A.N.; Naina Mohamed, I. Phytochemical Analysis, Antioxidant and Bone Anabolic Effects of Blainvillea acmella (L.) Philipson. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Widyowati, R. New Methyl Threonolactones and Pyroglutamates of Spilanthes acmella (L.) L. and Their Bone Formation Activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Laswati, H.; Subadi, I.; Widyowati, R.; Agil, M.; Pangkahila, J. Spilanthes acmella and physical exercise increased testosterone levels and osteoblast cells in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis male mice. Bali Medical Journal 2015, 4, 76. [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.; Berger, M.; Santana de Cecco, B.; Mallmann, L.P.; Terraciano, P.B.; Driemeier, D.; Rodrigues, E.; Beys-da-Silva, W.O.; Konrath, E.L. Chymase inhibition: A key factor in the anti-inflammatory activity of ethanolic extracts and spilanthol isolated from Acmella oleracea. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2021, 270, 113610. [CrossRef]

- Moro, S.D.; de Oliveira Fujii, L.; Teodoro, L.F.; Frauz, K.; Mazoni, A.F.; Esquisatto, M.A.; Rodrigues, R.A.; Pimentel, E.R.; de Aro, A.A. Acmella oleracea extract increases collagen content and organization in partially transected tendons. Microscopy Research and Technique 2021, 84, 2588-2597. [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Sahu, N.; Deka, S.; Dutta, S.; Das, S. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of leaves of Spilanthes acmella (ELSA) in experimental animal models. Pharmacologyonline 2009, 1, 1027-1034.

- Indrayani, I. Potential of Legetan Leaves (Acmella oleracea) as a Therapeutic Modality for Osteoarthritis: An In Vivo Study. Eureka Herba Indonesia 2024, 5(2), 441-445. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Sarkar, S.; Dutta, T.; Bhattacharjee, S. Assessment of anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic properties of Acmella uliginosa (Sw.) Cass. based on experiments in arthritic rat models and qualitative gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses. Journal of intercultural ethnopharmacology 2016, 5(3), 257-262. [CrossRef]

- Woolf, A.D.; Pfleger, B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. World Health Organization Bulletin 2003, 81(9), 646-656. [CrossRef]

- Van der Tempel, J.; Zambon, P. Musculoskeletal disorders: Pathophysiology and management. Journal of Musculoskeletal Research 2016, 19(4), 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Arora, D.S. Antibacterial activity of Spilanthes acmella and its bioactive constituents. Phytomedicine 2009, 16(12), 1115-1119. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Saha, S. Pharmacological potential of Acmella oleracea (L.) R.K. Jansen: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2014, 154(1), 51-62. [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.D.; Hattersley, G.; Riis, B.J.; et al. Effect of Abaloparatide vs Placebo on New Vertebral Fractures in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 316(7), 722-733. [CrossRef]

- Cosman, F.; Crittenden, D.B.; Adachi, J.D.; et al. Romosozumab Treatment in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 375(16), 1532-1543. [CrossRef]

- Langdahl, B.L.; Libanati, C.; Crittenden, D.B.; et al. Romosozumab (a sclerostin monoclonal antibody) versus teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis transitioning from bisphosphonate therapy: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2017, 390(10102), 1585-1594. [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.A.; Gooi, J.H. Bone remodeling: Multiple cellular interactions required for coupling of bone formation and resorption. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2008, 19(5), 444-451. [CrossRef]

- Raggatt, L.J.; Partridge, N.C. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285(33), 25103-25108. [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis treatment: recent developments and ongoing challenges. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2017, 5(11), 898-907. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Miron, R.J.; Shi, B.; Bian, Z. Anabolic bone formation via a site-specific bone-targeting delivery system by interfering with semaphorin 4D expression. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2020, 35(6), 1147-1160. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Bai, C. Icariin promotes bone formation via the ERα-Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the osteoprotegerin-deficient OVX mice. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2021, 236(1), 180-191. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, F.; He, Q.; Wang, J.; Shiu, H.T. Effects of treadmill exercise on bone mass, microarchitecture, and turnover in ovariectomized rats: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporosis International 2022, 33(2), 327-342.

- Dubey, S.; Maity, S.; Singh, M.; Saraf, S.A.; Saha, S. Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Toxicology of Spilanthes acmella: A Review. Advances in pharmacological sciences 2013, 423750. [CrossRef]

- Al Shoyaib, A.; Archie, S.R.; Karamyan, V.T. Intraperitoneal Route of Drug Administration: Should it Be Used in Experimental Animal Studies?. Pharmaceutical research 2019, 37(1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Nudo, S.; Jimenez-Garcia, J.A.; Dover, G. Efficacy of topical versus oral analgesic medication compared to a placebo in injured athletes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2023, 33(10), 1884-1900. [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Cell line Animal model Patients |

- |

| Intervention | Acmella genus plant extracts | - |

| Comparison | Cells not receiving Acmella plant extracts Positive and negative control groups |

- |

| Outcome | Bone cell parameters Arthritis scoring Muscle circumferences |

- |

| Study Type | In vitro and in vivo studies, randomized controlled studies, case-control studies, cohort studies | Case reports, editorials, communications, reviews, meta-analysis |

| Source | Search Term | Filters | Number of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY [("Acmella" OR "spilanthol") AND (musc* OR arth* OR tendon* OR osteo* OR bone)] | English language Publication years: 2004-2024 |

49 |

| Google Scholar | ("Acmella" OR “spilanthol") AND (musc* OR arth* OR tendon* OR osteo* OR bone) | English language Publication years: 2004-2024 |

258 |

| PubMed | [("Acmella"[All Fields] OR "spilanthol"[All Fields]) AND ("musc*"[All Fields] OR "arth*"[All Fields] OR "tendon*"[All Fields] OR "osteo*"[All Fields] OR ("bone and bones"[MeSH Terms] OR ("bone"[All Fields] AND "bones"[All Fields]) OR "bone and bones"[All Fields] OR "bone"[All Fields]) | English language Publication years: 2004-2024 |

15 |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| English language | Non-English language articles |

| Articles published within the past 20 years (2004-2024) | Articles published earlier than 2004 |

| Articles with abstracts | Reviews or meta-analyses |

| Research articles | Letters, editorials or case studies |

| Author and Year | Type of plant extract | Dose | Study design and sample size | Musculoskeletal related objective | Parameters | Musculoskeletal findings | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widyowati et al., 2011 [20] | Ethanol extract of the leaves of Spilanthes acmella |

50 μg/mL | In vitro, MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cells | To discover the ideal anabolic agent by measuring on alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity as a marker of osteoblast differentiation |

i. ALP activity | The Spilanthes acmella had a dose-dependent stimulatory activity on ALP up to 25 g/mL |

Spilanthes acmella has bone anabolic activities |

| Abdul Rahim et al., 2022 [21] | Ethanol extract of Blainvillea acmella leaves |

2.93 µg/ml to 1,500 µg/ml |

In vitro, MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cells | To determine the relationship between phytochemical compounds, antioxidants and bone anabolic activities of Spilanthes acmella |

i. GCMS and LCTOFMS analyses. ii. Antioxidant activities: DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays iii. Bone formation: collagen formation, ALP activity and Alizarin red assay |

Positive correlations were observed between phenolic content to antioxidant and bone anabolic activities |

Blainvillea acmella may be a valuable antioxidant and anti-osteoporosis agent |

| Widyowati et al., 2020 [22] | Isolated compounds of methanol extract of Spilanthes acmella leaves |

12.5 & 25 μM | In vitro, MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cells | To test the isolated compounds of Spilanthes acmella for bone formation activities | i. ALP activities ii. Calcium deposition (Alizarin red staining) |

These compounds stimulated both ALP and mineralization activities.: 1,3-butanediol 3-pyroglutamate, 2-deoxy-d-ribono-1,4-lactone, methyl pyroglutamate, ampelopsisionoside, icariside B1, and benzyl α-l-arabinopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranoside |

Six active compounds in Spilanthes acmella were identified to promote bone formation and mineralisation |

| Laswati et al., 2015 [23] | Ethanol extract of the leaves of Spilanthes acmella |

4.14 mg/20 g BW/day |

In vivo study, glucocorticoid-inducedosteoporosis mice |

To analyze the effect of Spilanthes acmella and physical exercise in increasing testosterone and osteoblast cells of femoral’s trabecular glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis male mice |

i. Testosterone levels ii. Bone histology |

Combination of Spilanthes acmella and exercise increased testosterone level and osteoblast cells compared to osteoporosis group |

Spilanthes acmella have an additive effect to exercise in protection against glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis |

| Pradhan et al., 2021 [19] | SA3X capsules (containing 500 mg of Spilanthes acmella extract, standardized to 3.5% spilanthol delivering 17.5 mg spilanthol) |

Population based study: 240 male subjects | To determine the effects of Spilanthes acmella on muscle mass | i. Muscle mass assessments: mid upper-arm circumference (MUAC), chest circumference (CC), thigh circumference (TC) | A significant increase in the MUAC | Spilanthes acmella may be a potent muscle gainer | |

| Stein et al., 2021 [24] |

Acmella oleracea leaves and flowers extracts; Spilanthol |

In vitro: 25–100 μg/mL Spilanthol: 50–200 μM In vivo: 10, 30 & 100 mg/kg intraperitoneal injections (IP) Spilanthol: 6.2 mg/kg IP |

In vitro: Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) in hyperglycemic media In vivo study: Formalin induced paw edema in rats |

To characterize the anti-inflammatory effects of Acmella oleracea and spilanthol |

In vitro: i. Chymase ii. ROS production In vivo: i. Paw volume ii. NO level iii. Histology – cellularity |

Reduced chymase activity & expressions and reduced ROS production Reduced paw edema, NO production and cell tissue infiltration |

Acmella oleracea and spilanthol possess significant anti-inflammatory activity |

| Moro et al., 2021 [25] | Topical application of 20% Acmella oleracea leaves and flowers ointment | In vivo study: rats with partial transection of calcaneal tendon | To analyze the effects of topical application of Acmella oleracea ointment (20%) on the repair process of the calcaneal tendon in rats |

i. Morphometry ii. Polarization microscopy: birefringence iii. Measurements iv. Biomechanical parameters v. Hydroxyproline quantification |

Topical Acmella oleracea promoted healing of calcaneal tendon Higher birefringence values and hydroxyproline concentration of collagen in the tendon |

Topical Acmella oleracea ointment increased the molecular organization and content of collagen, thus presenting a potential application in tendon repair |

|

| Barman et al., 2009 [26] | Ethanolic extract of leaves of Spilanthes acmella |

500 mg/kg | In vivo study: Carrageenan and Freund’s Complete Adjuvant induced rat paw edema | To evaluate the anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of Spilanthes acmella |

i. Paw volume ii. Arthritis index |

ELSA (500 mg/kg, p.o) showed significant reduction in paw volume and arthritis score compared to the control group |

Spilanthes acmella possesses significant anti-inflammatory activity |

| Indrayani et al., 2024 [27] |

Acmella oleracea leaves ethanol extract |

200 & 400 mg/kg BW | In vivo study: monosodium iodate (MIO) induced knee osteoarthritis of rat | To evaluate the potential of Acmella oleracea leaves for treatment of osteoarthritis in a rat model | i. Pain scores using the Randall Selitto method ii. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels. iii. Knee joint histology |

Reduced pain scores. Lowered IL-1β levels (200, and 400 mg/kg BW) Lowered TNF-α levels (400 mg/kg BW) |

Acmella oleracea leaf extract can reduce pain and inflammation of osteoarthritis -induced rat joint homogenates |

| Paul et al., 2016 [28] |

Acmella uliginosa (AU) (Sw.) Cass. Flower |

417 mg/kg and 833 mg/kg | In vivo study: rats with model of arthritic paw swelling, Freund’s Complete Adjuvant | To explore the anti-arthritic properties of Acmella uliginosa |

i. Paw circumference, ii. serum biochemical parameters, iii. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analyses |

Reduced paw swelling. Increased hemoglobin, serum protein, and albumin levels. Normal creatinine level. GC/MS analyses revealed five anti-inflammatory compounds |

Crude flower homogenate of AU contains potential anti-inflammatory compounds which could be used as an anti-inflammatory/anti-arthritic medication |

| Rondanelli et al., 2020 [18] | Food-grade lecithin formulation of standardized extracts of Zingiber officinale and Acmella oleracea |

2 tablet/day for 4 weeks | Quasi-experimental human study: 50 patients with knee osteoarthritis |

To evaluate the efficacy of lecithin formulation of standardized extracts of Zingiber officinale and Acmella oleracea in reducing the pain and inflammation of osteoarthritis |

i. Pain intensity by visual analogue scale (VAS) ii. WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis) Index and Tegner Lysholm Knee Scoring iii. Health-related quality of life: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) iv. C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) v. Body fat composition by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) |

A significant decrease in VAS. Significant improvements in WOMAC, Lysholm and SF-36 scores. Significant decrease in CRP and ESR and increase in fat-free mass |

The tested formulation seems to be effective in reducing pain and inflammation of osteoarthritis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).