INTRODUCTION Ion channels, including voltage gated ion channels, have been the subject of intensive research for the better part of a century. Their importance in a wide range of diseases, as well as their role in critical biological functions, including nerve pulses, has justified this effort. There is a range of channels, and a set of functions that all channels must carry out to function, including: 1) gating,

i.e., the control of opening the channel for conduction, 2) selectivity—choosing what to conduct 3) ancillary functions including ending conduction, often accomplished by inactivation. The latter is a state in which the channel undergoes a transition that stops conduction, prior to returning to the original closed state so that the channel can repeat the cycle. Control of gating may be effected by change of membrane potential, for voltage gated channels, or by ligands (ligand gated channels), or by other environmental variables (

e.g., temperature, pressure). At least some channels have protons responsible for gating, or possibly partially responsible for gating. There are now known structures of channels, going back to the work of MacKinnon and colleagues a quarter century ago [

1]. Since then, there has been much effort devoted to the mechanism by which channels operate. In this paper, we consider the gating of voltage gated channels. It is now showing in detail how a proposal first made in 1989 [

2] has been, in part, confirmed by quantum calculations. In that paper, one of us proposed that the gate consisted of water, frozen (immobile) when closed, and essentially liquid when the channel was open. The mechanism by which this, and the gating current, happened, has been long since superseded—in fact, describing the water as “frozen” can no longer be considered correct, although at the present time the fundamental idea that the arrangement of water is crucial in gating still appears to be correct. In this review, we refer to our earlier work showing that the gating current may be protons [3-6], along with evidence from the rest of the literature that can be shown to be consistent with this mechanism. Most of the evidence has been interpreted in terms of a mechanical gating model. We consider reasons for interpreting the data instead in terms of protons as gating current.

To understand the gate, and the effect of the changes in water structure as affected by protons, we can draw on a huge volume of research on water in boundary layers, especially in the boundary layers of proteins. In addition, we can see that the dimensions of the gate, in any model, are of the order of a few Angstroms to perhaps two nanometers, with a thickness of the gating region also on the order of nanometers. This means the water is confined water, which is known to be different in important properties from bulk water. Since this is a review of the gating of channels, especially of a subset of potassium channels, we will restrict our discussion of confined water to what is most relevant, still a substantial literature.

A gating mechanism that involves water and proton motion, but not S4 motion: The generally accepted gating model has a segment, S4, of each of four voltage sensing domains (VSD) moving in response to an external electric field, compressing the gating region when the voltage is on, closing the channel. Each VSD has four transmembrane helices; S4 has a series of positive charges, mainly arginines, and has therefore been considered to be the helix that moves in response to an external field. When the voltage is removed, S4 is believed, in this class of models, to return to its position within the membrane, next to the negatively charged S2 and S3 helices. We will discuss the evidence that led to this type of model, and show that it can also be interpreted in terms of the motion of protons, not protein. There is also considerable evidence that is difficult to interpret in a gating mechanism that involves motion of S4; this evidence is often ignored. We will consider both the evidence that appears consistent with the standard, S4 moving, model, and the evidence that is often ignored. We will consider the question of the structure of the closed state, but the open state structure is determined to high resolution by X-ray crystallography. If, as we postulate, protons enter the gating region to close the channel, this must work by rearranging the water, and affecting the hydration state of the ion. Obviously this is all conditional on the boundary conditions provided by the protein; the boundary can also rearrange (e.g., a serine or threonine hydroxyl may reorient, or an aspartate may be neutralized with further effects as a consequence) in response to protons entering the gating region; the dimensions of this region are less than 2 nm, so that it can change the hydration state of the permeant ion. In the region there are, in addition to the permeant ions, protein side chains, water, counterions, and depending on the state of the channel gating cycle, additional protons. Together, these form structures that either allow the permeant ion to move forward, or block it. Calculations showing these structures have recently been completed, and these details will be published (Kariev and Green, in preparation). The topics discussed in this review are as follows:

- 1)

The HV1 channel as an analogue of the VSD

- 2)

There is evidence from sodium channels that gating was slowed by D2O

- 3)

Certain mutations in the gate region make a huge difference

- 4)

Proton concentration at the gate can be very high

- 5)

in a bacterial sodium channel, NavAb, hinge motions of the pore helix S6 and the C-terminal domain were involved with gating,

- 6)

T1, the intracellular segment of the channel protein, matters.

- 7)

The piquito, a brief pulse at the start of the channel opening sequence—proton tunneling?

- 8)

Much of the evidence for the standard mechanical model is derived from experiments in which arginine was swapped for cysteine; the interpretation?

- 9)

Other residues could be mutated as well

- 10)

Many molecular dynamics calculations on ion channels have been published; how should they be understood?

- 11)

Confined water, especially in channels, differs from bulk water

- 12)

hydration dynamics sometimes show S4 (protein segment) not moving

- 13)

prolines at the gate, and other conserved residues

- 14)

The EAG channels are also potassium channels with known structures, open and closed

- 15)

Vibrations and rotations

- 16)

Thermodynamics

- 17)

Quantum properties of protons

- 18)

Experiments that appear to be more consistent with the standard model; reinterpretation?

- 19)

Omissions from this review

- 20)

A speculation that grows out of the proton gating model

In summary, we can see how the evidence points to a gating mechanism in which the gating current consists of proton motion, not motion of the S4 segment of the VSD. The structure of the water and ions in the confined space defined by the structure of the side chains of the boundary proteins, determines the gating mechanism

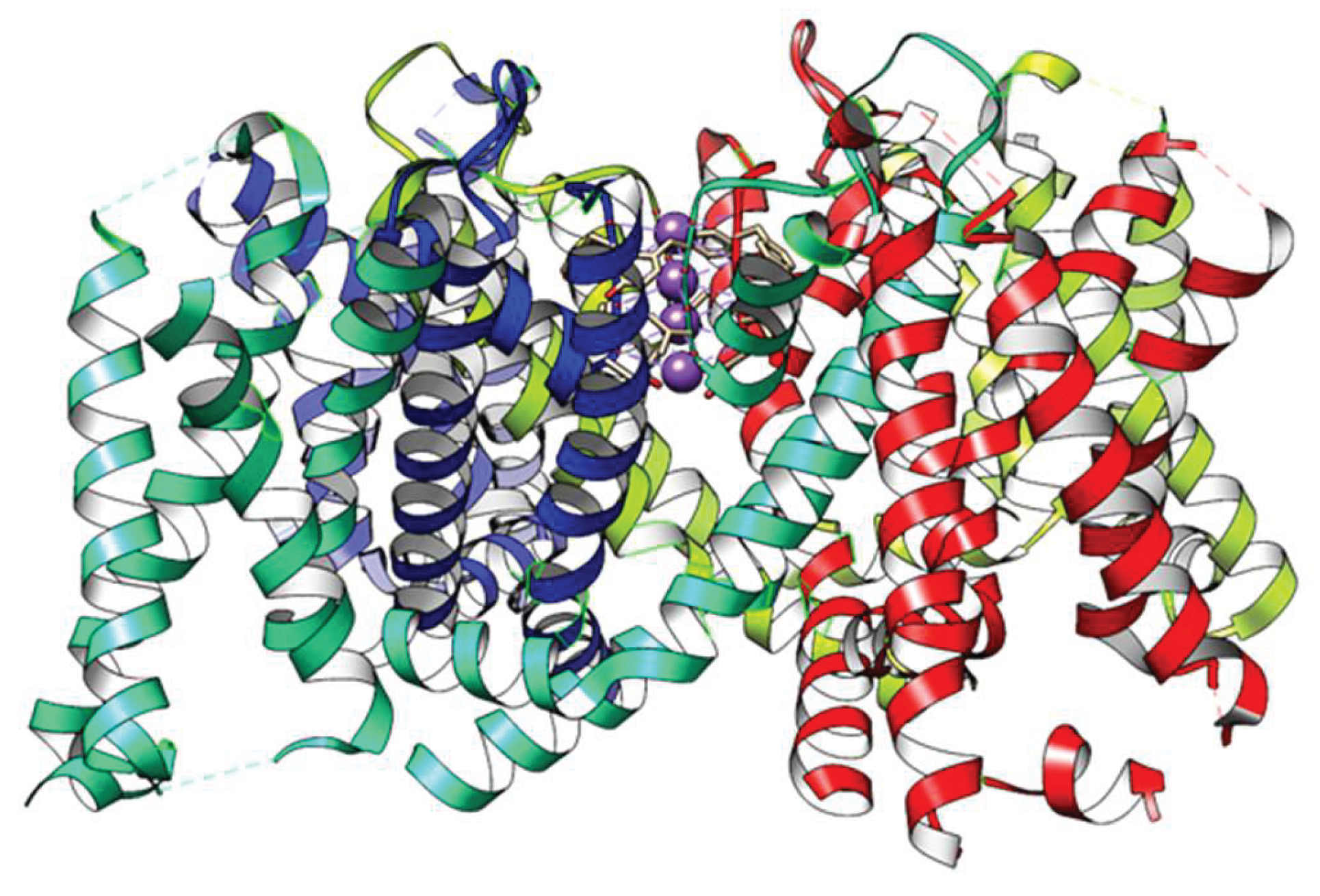

Figure 1.

A traditional view of the channel structure shows only protein, but ignores the water and ions that are required for it to function. This version, created by Chimera from the 3Lut open structure, shows the 4 voltage sensing domains, and does include K+ ions in the selectivity filter—ions in all 4 positions, although almost certainly they are not all occupied simultaneously. The X-ray structure does include water molecules, but they are not included by Chimera.

Figure 1.

A traditional view of the channel structure shows only protein, but ignores the water and ions that are required for it to function. This version, created by Chimera from the 3Lut open structure, shows the 4 voltage sensing domains, and does include K+ ions in the selectivity filter—ions in all 4 positions, although almost certainly they are not all occupied simultaneously. The X-ray structure does include water molecules, but they are not included by Chimera.

Review of the evidence: We can list the main sets of evidence that bear upon the questions we are considering, in a set of topics that cover the most important aspects of the question.

- 1)

The HV1 channel as an analogue of the VSD: There are channels known to conduct protons. The H

v1 channel has a structure that is in many ways similar to the VSD [7-10], although there exist significant differences (for one thing, H

v1 is a dimer, and the proton path would differ somewhat from that in the VSD of the mammalian K

v1 channel; the upper (extracellular) part of the channel strongly resembles that of the VSD of the K

v1.2 channel, while the path differs somewhat in the intracellular section, with H

v1 going directly to the intracellular side of the membrane, while K

v1.2 deviates toward the pore). Although it is not generally considered that this challenges the standard model, it is difficult to see why it does not; this provides a similar path that could be taken by protons [

11]. H

V1 has been the subject of multiple studies, and there is still not general agreement on its gating mechanism [8,12-17]. Of particular interest, it appears that protons contribute to gating current, and there is pH sensitivity as well as voltage sensitivity in gating [8,14,18-20]; While there are a variety of models in which the S4 segment moves, the fact that a proton gradient can at least contribute to gating suggests that the voltage gating may work via a proton cascade. Protonation of an aspartate on the S1 segment as part of the mechanism of proton transport [

20] would also suggest that proton transport may play a role in voltage gating, although admittedly this is indirect evidence. A number of residues, when mutated, change the gating, transport, and other properties of the channel [

7,

8,

21,

22], and some lead to a contribution of protons to the gating current. Channels with a rather different structure also transmit protons, and suggest alternate possible proton transmitting paths, such as in the M2 channel of the influenza virus; specific paths for the A and B variants have different paths, and different pKa values for specific histidine residues [

23]. Some of the steps in this channel are almost certainly applicable to other ion channels, including those we are considering here. However, this path does differ from the voltage gated potassium channel by appreciably more than H

v1 does. The fact that the water network structure rearranges between the open and closed states of these channels is similar to what we find (Kariev and Green, in preparation) for the voltage gated potassium channels that we are discussing.

- 2)

There is evidence from sodium channels that gating was slowed by D2O [24-26]. Furthermore, different effects of D

2O are found on different phases of gating. Starkus and Rayner and coworkers found at least two stages in gating that were affected by D

2O substitution; in particular this included the finding by Alicata

et al that the last step in gating a sodium channel was slowed by D

2O [27-29]. MD simulations typically use TIP3P water, which is not a good model for water, including in particular for confined water; because D

2O is important, an accurate water model is needed, at a minimum including polarization [

30], in order to produce a D

2O effect. If D

2O makes a difference, then water must actually be part of the gating mechanism. If protons are important, this is expected. On standard models, it is hard to understand why D

2O matters. D

2O has also been found to affect inactivation by changing the nature of the hydration around the pore, rather than within the pore [

31]. The possible non-specific effects of D

2O, such as viscosity, were ruled out. Given that there is coupling between inactivation and the gate at the entrance to the pore [

32], this may be further evidence that structural water is part of the gating mechanism. This is the most economical interpretation of the data.

- 3)

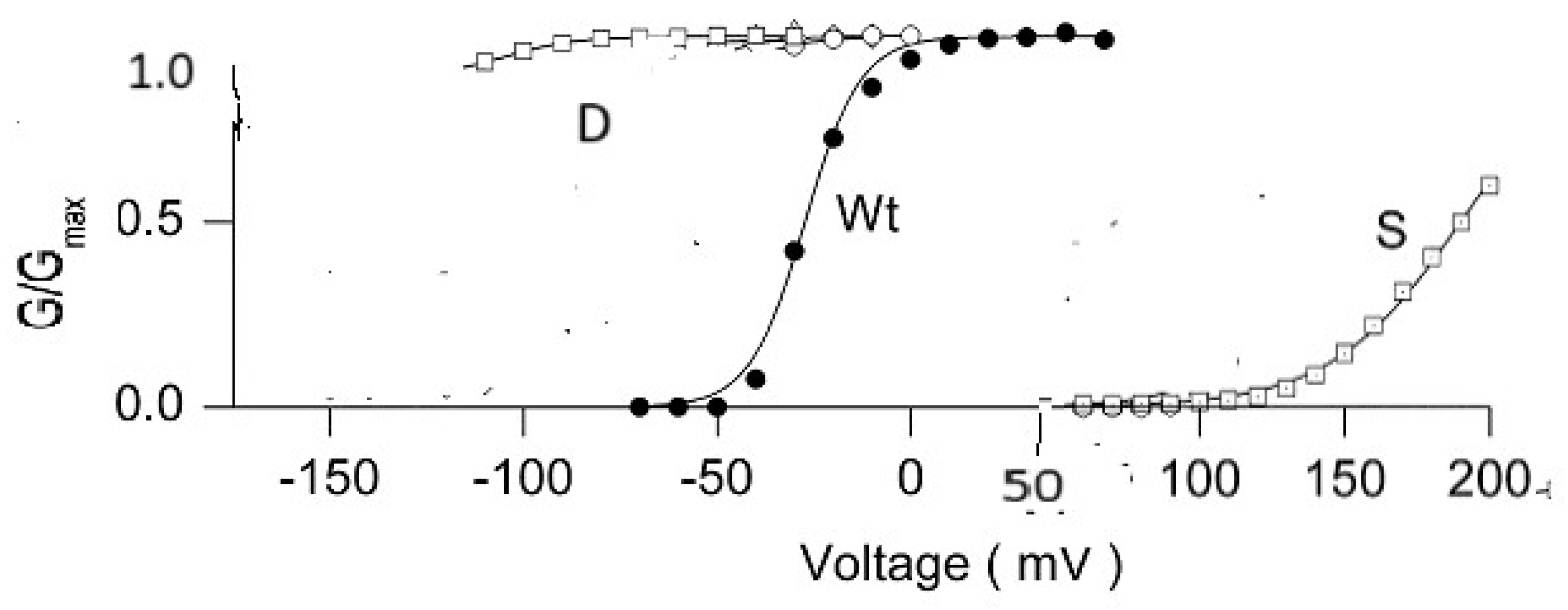

Certain mutations in the gate region make a huge difference. One particularly important case is the proline to aspartate mutation in the highly conserved PVPV sequence at the gate that produces a channel essentially constitutively open at physiological potentials [33-35]. This is qualitatively relatively easily understood on the proton model, but not on the mechanical model. On the proton model, the aspartate could be protonated, making the carboxyl group neutral, thus removing the protons from the gate, and allowing it to operate like the open, unprotonated, gate. Substitution of serine led to a channel that was closed at all physiological potentials. The serine side chain is smaller than the aspartate (or proline) side chain, meaning that the channel should have its gate wide open. The fact that the serine mutant is closed does not seem consistent with the mechanical model, but makes perfectly good sense if potassium transit through the pore, and especially near the proline level of the gate, depends in part on the dehydration of the K+ ion. The potassium must be at least mostly dehydrated; if it reached the cavity at the central portion of the pore with the water that hydrated it in solution, then there would have to be a countercurrent of water that would block passage of following ions, almost certainly for long enough to limit the current severely. Dehydrating the ion requires that the gate opening be correctly spaced to allow the local amino acids to strip the water from the potassium ion—too wide an opening would prevent that. This of course requires an answer to why the gate works at all, if the spacing is important but is the same in open and closed states (see section 12 below). Protons at the gate could have several effects, including rotating the side chains of the gate amino acids, and forming networks that include water, side chains, and the ions. Amide side chains in one orientation could dehydrate the potassium ion, while in the other conformation, they fail to do so, and the ion is unable to progress into the pore cavity—the difference between open and closed would thus not require motion of the protein backbone, but would be a local effect of the protons on side chain orientation. The formation of networks looks even more important.

- 4)

Proton concentration at the gate can be very high. In a 1M H+ (pH 0, if one ignores activity coefficients) there are about 55 water molecules to each proton (half that, if the other half are hydrating the counterion). With four protons in a region containing perhaps 20 water molecules, meaning the equivalent of somewhere between 5 and 10 M, the effective concentration is much greater. There are lots of uncertainties in detail—counter ions, the number of water molecules, and activity coefficients, to begin with. It is safe to say the region is as strongly acid as is possible, so the dissociation of the acids in bulk can still allow for protonation, or at least ion pairing, under the circumstances present at the gate. It is not silly to postulate protonated amides, for example. H+ - Cl- ion pairs are likely, although HCl is a strong acid in bulk. The actual distribution of the protons cannot be guessed, but must be determined by calculation; the protons behave as quantum particles, and should be calculated as such; unfortunately, even standard quantum calculations depend on the Born-Oppenheimer (B-O) approximation, even for protons, so the protons are not treated completely correctly; however, the remainder of the system and the molecules are treated reasonably accurately, and we must assume the B-O approximation does not introduce so much error as to invalidate the calculation.

- 5)

Wallace and coworkers found, in a bacterial sodium channel, NavAb, that hinge motions of the pore helix S6 and the C-terminal domain were involved with gating, and affected gate diameter, but there was essentially no S4 movement between open and closed structures [

37,

38]. It is conceivable that for some reason, not at all clear, this channel is unique; although it has some differences with other channels, it has the same fundamental structure as all other members of the superfamily that includes both it and the type of channel we consider here. This is strong evidence that S4 need not move to effect gating. However, something must move in response to voltage without changing the structure of the channel. Protons are one thing that could fulfill this requirement.

- 6)

T1, the intracellular segment of the channel protein, matters [

39]—in standard models, why? No version of a standard model seems to accommodate this; T1 seems to be in the wrong place for a van der Waals push between the S4 and the gate—it stretches “down” (i.e., intracellular direction), and pulls the linker away from the gate if pushed down by S4. We have found a proton path that extends through T1, between S4 and the gate [

40]. There is also a paper by Cushman et al that reinforces this point; substituting aspartate for asparagine in T1 near the T1 to gate junction leads to left shifted gating and larger current [

41]. Proton transfer is one possibility that would account for this experimental finding. The carboxyl group is known to be efficient in dehydrating potassium; we also observe that the distance of T1 from the membrane surface is less than 2 nm, and thus contains confined water. Aspects of the space separating the membrane, or its surface, from T1, may affect the transport of anything, but especially protons, from the VSD to the pore.

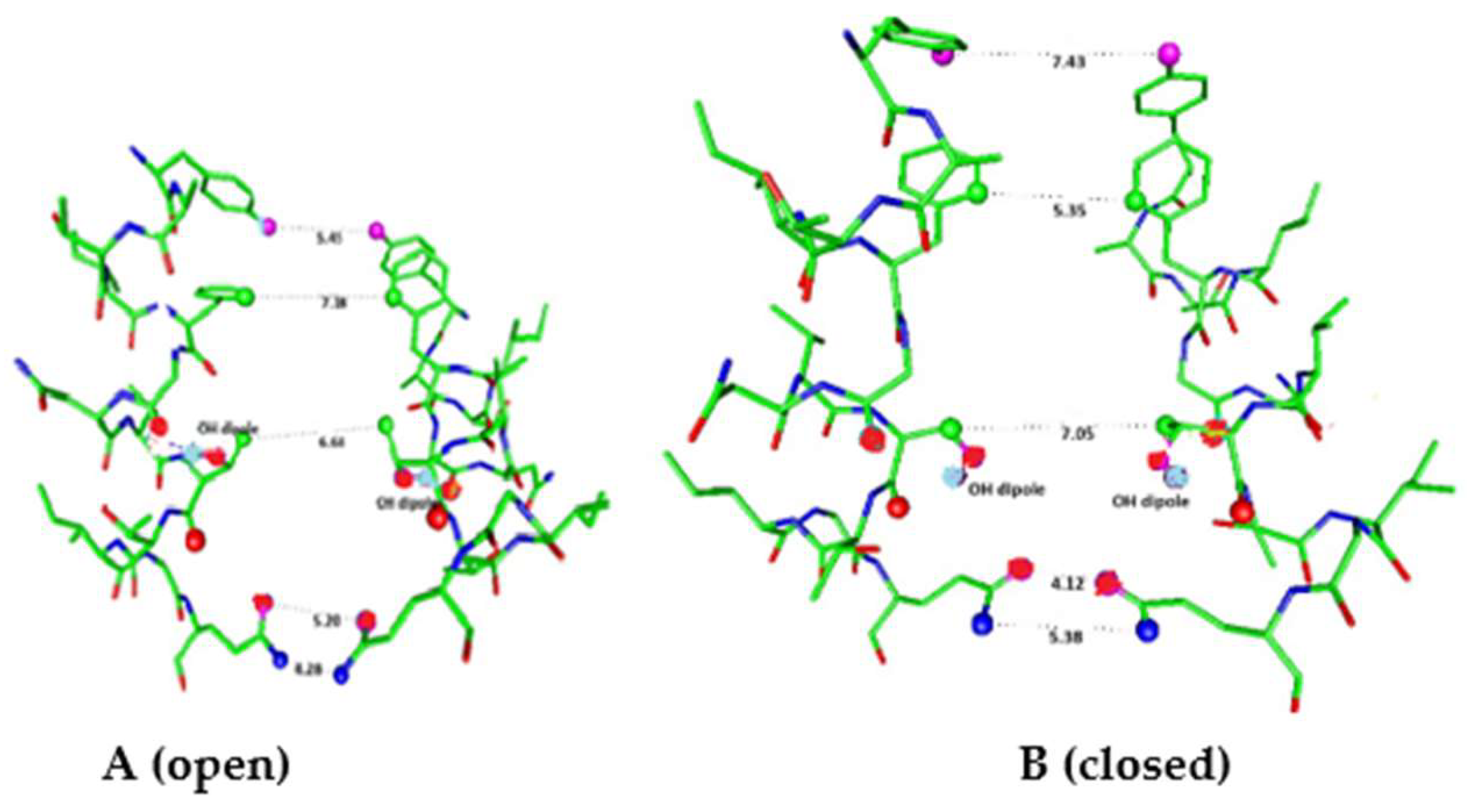

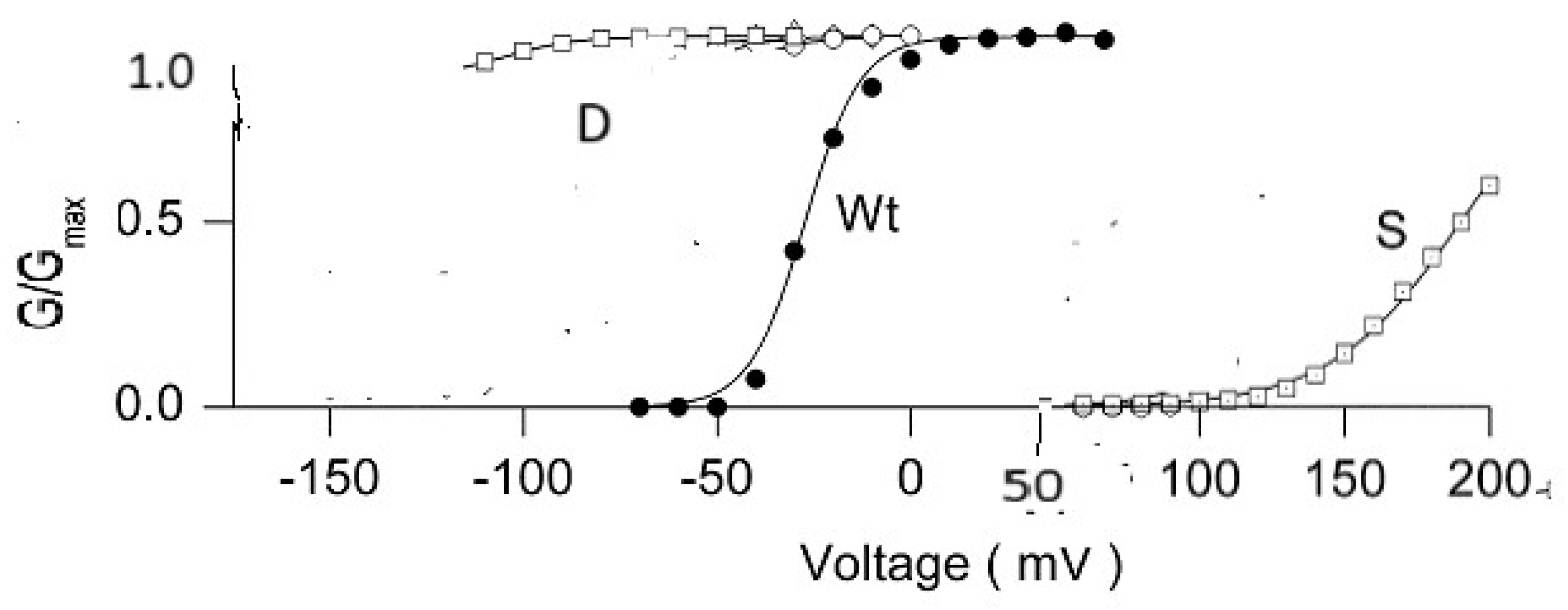

Figure 2.

Adapted from figure 3B and 3C of Sukhareva et al [

34]; the current voltage curves of wild type (WT) and the P475X mutations (X=D or S) of the Shaker channel, showing that the aspartate mutation is open at all physiologically relevant potentials, essentially constitutively open, while the serine mutation is closed at all physiologically relevant potentials. Several other mutations fell between these limits, much closer to WT. The change in scale of the horizontal axis at +50 mV has no significance. (We thank Dr. K. Swartz for permission to copy his data; presentation in this form, however, is the responsibility of the present authors). Not only must the ion be dehydrated at the gate, but it is then rehydrated in the cavity just beyond the gate [

36]. This makes sense, as the cavity contains multiple water molecules. These are available for rehydrating the ion as it emerges from the gate region; the hydration is not so strong that the ion cannot again be partially dehydrated as it enters the selectivity filter at the opposite end of the pore from the gate. The driving force for the ion as it passes through the pore must include an accounting for the role of water. .

Figure 2.

Adapted from figure 3B and 3C of Sukhareva et al [

34]; the current voltage curves of wild type (WT) and the P475X mutations (X=D or S) of the Shaker channel, showing that the aspartate mutation is open at all physiologically relevant potentials, essentially constitutively open, while the serine mutation is closed at all physiologically relevant potentials. Several other mutations fell between these limits, much closer to WT. The change in scale of the horizontal axis at +50 mV has no significance. (We thank Dr. K. Swartz for permission to copy his data; presentation in this form, however, is the responsibility of the present authors). Not only must the ion be dehydrated at the gate, but it is then rehydrated in the cavity just beyond the gate [

36]. This makes sense, as the cavity contains multiple water molecules. These are available for rehydrating the ion as it emerges from the gate region; the hydration is not so strong that the ion cannot again be partially dehydrated as it enters the selectivity filter at the opposite end of the pore from the gate. The driving force for the ion as it passes through the pore must include an accounting for the role of water. .

7)

Piquito, a brief pulse at the start of the channel opening sequence—proton tunneling? There is a brief pulse at the beginning of the gating current that has been labeled the “piquito” [

42,

43]; it has fairly well defined characteristics: timing <2μs (how much less is unknown), and magnitude (around 1% of gating current). This can be accounted for by proton tunneling, which can move a charge perhaps 1 Å. If this is one of three protons to move, it would be about 1/3 of the charge associated with one VSD. The observed charge motion, about 1% of gating current, would be about right if it moves 1/3 of the total charge (i.e., about one charge) through about 1/30 of the distance, which for a 1 Å distance makes sense, more or less—this is too rough a “calculation” to expect much better accuracy, but at least the order of magnitude is right). It is possible to estimate the transmission probability for a proton through a 1 to 2 Å barrier with and without a field applied, using the WKB approximation [

44],. For a barrier about 20 k

BT high, it is possible to shape the barrier to get a result that agrees with the tunneling hypothesis. However, absent any specific evidence, the most that can be said now is that the hypothesis is plausible, and can agree with the observation. A mechanical model might suggest perhaps an arginine side chain flip, but why would this be coupled to the motion of the entire S4 segment? A more plausible side chain flip that need not be associated with proton tunneling would be a reorientation of the side chain of a phenylalanine that could be associated with the transient proton in the VSD, although the nature of this association is not certain to be direct. There is a phenylalanine, F222, in the VSD of the 3Lut (pdb) [

45] structure that appears to be the standard for the open structure of the K

v1.2 potassium channel, not far from the location of the large voltage drop found by Asamoah et al [

46]. This would still accompany a proton gating model as it is not associated with an actual translation of S4. The piquito makes perfect sense as part of a proton gating model, both as regards the order of magnitude that might be expected, and as to the effect of a localized field like that reported by Asamoah et al. Further work would be required to move this hypothesis to a more certain footing; so far it can be said that proton tunneling can be a plausible mechanism, and it is very difficult to reconcile this result with a mechanical model.

8)

Much of the evidence for the standard mechanical model is derived from experiments in which arginine was swapped for cysteine, and the cysteine was then reacted with an MTS reagent, a technique developed by Yang and Horn [

47]. This assumes that the cysteine, which must ionize to react, must move to the membrane surface to ionize, to get out of the low dielectric environment of the membrane. Actually, the cysteine side chain is tiny compared to arginine, so water, as well as MTS reagents, can reach the cysteine

in situ. Cysteine can therefore presumably ionize without moving. Replacing arginine with cysteine makes the space available. The apparent accessibility of the cysteines was interpreted as demonstrating the motion of the cysteines, and thus S4. As we do not have the crystal structure of the mutated VSD, it is not appropriate to make a quantitative assertion as to the dimensions of the available space. We note, however, that the guanidinium group is approximately the size of a methyl thiosulfonate group, while the cysteine side chain, consisting of a single atom when ionized (not much bigger with the H atom added when not ionized), takes up almost no space. If the R→C mutation just opens space for an MTS reagent, the primary evidence for S4 motion can be accounted for without S4 motion.

9)

Other residues could be mutated as well. For example, Horn and Nguyen mutated residues on S3, which has negative charge. On the simplest interpretation, this should have shown opposite accessibility, but it showed the same accessibility [

48] and thus the same apparent motion as S4. In spite of this, the result was reinterpreted as consistent with the standard model. A paper by Naranjo and coworkers found that substituting aspartate for arginine in the VSD, again reversing charge, had little effect on the gating current [

49] [

50]. It did not reverse the direction of the gating current, as might have been expected from the charge reversal if S4 were mobile, although it produced other effects, particularly a large volume change near S2 and S3. The last result is much more easily understood with proton gating, in which the cysteine accessibility did not depend on physical movement of the cysteine. The authors, however, kept an interpretation that is consistent with the standard mechanical model.

10)

Many molecular dynamics calculations on ion channels have been published. These usually claim to show how some version of the standard model is correct, and have been recently reviewed by Phan et al [

30]. There are certain problems with these calculations:

i) These almost always use fields an order of magnitude too large, and distributed over the entire VSD. However, the voltage drop occurs only over a very limited region, essentially one arginine [

46]; the field at this one arginine is at least 10

8 V m

-1, similar to that used by the MD simulations, but it must be very local. 10

8 V m

-1 x 7 x 10

-10 m = 70 mV, the total available voltage. If one uses the field across the entire 70 x 10

-10 m thickness of the membrane, one needs 700 mV, which is an order of magnitude out of the physiological range. In addition, Onsager showed that fields this large produce increased probability of ionization of weak electrolytes via the 2nd Wien effect [

51]; since Onsager’s calculation depends on the local dielectric constant, it is difficult to apply quantitatively to the channel, but the effect must be appreciable. To produce a proton cascade, a weak electrolyte must ionize; if the MD calculations could take this into account, perhaps they too would find a proton cascade. By the time one gets to the fields used in MD simulations, this field may cause ionization through the entire VSD, although this would not appear in a classical calculation. The fields of 10

8 V m

-1 are large enough in any case to create a non-physical situation, except for the one arginine where the entire field drops [

46]. If the local field at the one arginine where the field is this large does not produce ionization by the Second Wien Effect, it may also lower the barrier for proton transfer, allowing tunneling to occur—a completely different mechanism, but one that also requires the high field to be very local, as 70 mV is all the voltage that there is

ii) The water model most frequently used, TIP3P, does not allow a good representation of the water in a confined space. In particular, this must be a problem at the gate of the channel. Since there is much evidence for water having considerable importance in gating, this suggests that key steps in gating will be given erroneous configurations in the MD simulation; this may be critical in itself. In addition, the protonation state cannot change during a classical simulation, so in many simulations the protonation state is assumed to be that in bulk solution at pH 7, not necessarily the correct set of protonation states; the incorrect protonation state can produce seriously incorrect results [

52]. Even better models than TIP3P, if they are not polarizable, do not make a serious advance in accuracy; polarizable potentials are very expensive, and therefore uncommon. Phan et al have shown that polarization may be critical in understanding the behavior of water in a channel sized pore [

30]. The behavior of water in nanopores has been thoroughly reviewed by Lynch et al; they see from the sum of MD studies that water is critical for transport, including proton transport. With a view to designing nanopores that can perform various functions, they see that such design requires accounting for the role of water [

53].

iii) No MD calculation has been shown to be reversible when the voltage is removed. Considering that the channel protein must get through thousands of cycles before the protein is replaced, this is a serious problem. MD simulations cannot reproduce reversibility (at least, no examples seem to be in the literature, except perhaps for a case in which the final structure is targeted by steered MD). MD, at least classical MD, does not appear to provide evidence that is convincing for mechanisms of voltage gating. While it is not the case that all MD calculations are incorrect, the majority of these calculations require extremely careful scrutiny, and they should not be generally accepted at face value. These calculations must not include implicit assumptions that are not valid, but this common; however, the situation may improve as computers become capable of running simulations that include at least polarization, and almost certainly other factors that remain to be explained. Until normal electric fields and reversibility of the simulation are possible, the MD results cannot be considered as providing good evidence of the behavior of channels. Newer forms of simulation are becoming available, of which the most important is probably AlphaFold. Use of AlphaFold is problematical in this context as well, since it rarely if ever is trained on structures that include explicit water. So far it appears that AlphaFold is not quite ready to use on channels. There are a few path integral or ab initio simulations, but these do not seem to include enough of the channel, at least up to this time, for them to produce gating models. When computer capabilities are sufficient, these should be able to produce reliable results.

11)

Confined water, especially in channels: In the introduction, we have already noted the vast literature on the state of water in confined spaces. Much of it concerns water in nanotubes [

54,

55], but there is also work on hydrophobic spaces, as well as on a few channels, albeit not the channels with which we are primarily concerned here [56-58]. Water in nanotubes has different transport properties, which apparently include quantum coherence and proton delocalization [59-65]. More to the point in the context of channels are the many studies of proteins with water, mainly internal and bound water in the proteins. We can only list a tiny fraction of this literature here [66-73], but the gist of the results is that water with limited freedom of motion is bound in some proteins, often in internal positions in the protein. The entire subject of confined water at protein surfaces was reviewed by Bellisent-Funel and coworkers [

74], and by Laage, et al [

75], among many others. Mondal et al in a brief review argued for the importance of the water hydrating proteins for the functioning of the proteins [

76]. Water crowding at the protein surface, with fluctuations, is also important [

77]. Other studies of interest include the use of spectroscopic techniques to determine the rates of relaxation or transitions among boundary water molecules [78-80]. The distribution of relaxation times also differs at the surface [

81,

82]. There have been many simulations (e.g, [

83]) although as we considered in the previous section, there is reason to be extremely cautious about accepting the results of classical molecular dynamics (MD) for confined water. Its properties often, probably generally, require use of quantum calculations. There has been an ongoing controversy over the importance of quantum effects [63,84-86], but there seems to be good reason by now to take these into account as well. Obviously, the discussion in this paragraph is no more than an introduction to the fact that water at protein surfaces plays a critical role in understanding the functioning of the protein, and that that water is unlike bulk water in several ways, including its hydrogen bonding, its relaxation, and its density, among other properties. We will encounter other examples in discussion of particular characteristics of water in relation to channel gating. In channels, interactions of water with ions, forming a network, are particularly relevant, and in at least one case a much more connected network has been found [

87]. Surface layer properties almost certainly apply to membrane surfaces as well; standard models of channel gating would have parts of S4 move along the membrane surface, and proton gating models would have protons transferring across the membrane surface, so membrane surfaces are relevant to the question of channel gating. Surface layers have been studied and found to have properties different from bulk water [

88]. Fluctuations in water in the channel have been proposed as involved in channel properties [

15]. The subject of water in channels has been reviewed, albeit largely from the point of view of simulations, but it is difficult to interpret [

53]. Moving protein, here S4, along the membrane surface would also be affected by these layers (see next section). The density of water in confined spaces can approximate that of water in the high density amorphous (HDA) phase that is known at low temperatures, and is a quite different phase of water than room temperature bulk water [

89], and this probably extends high water density for about two hydration shells that are unlike bulk water, making a distance of about 1 nm from the protein surface. This is enough to include the entire gating volume, as the gate diameter is never more than 2 nm. The ion enters the gate with, usually, six water molecules in its hydration shell, but exits the channel with at most two, based on streaming current studies [

90]; no model of the selectivity filter allows for more than 2 water molecules to leave for each potassium. Therefore, the gate must strip at least four water molecules from the potassium hydration shell when it is open. If it cannot do this, the gate is closed. We have carried out quantum calculations that show how this could be a major step in the gating mechanism for the Shaker potassium channel (Kariev and Green, in preparation). In addition, the vibrations and rotations of water in a confined space are different from those in bulk. We discuss this in section 15 below.

12)

When hydration dynamics are considered, as in the fluorescence studies of Raghuraman and coworkers, they show considerable importance for several channel states, and transitions [

91]. In this case, an inverse rectifier, KirBac 1.1, was studied, and the slide segment moved less than 3 Å, which similarly limits the S4 motion.

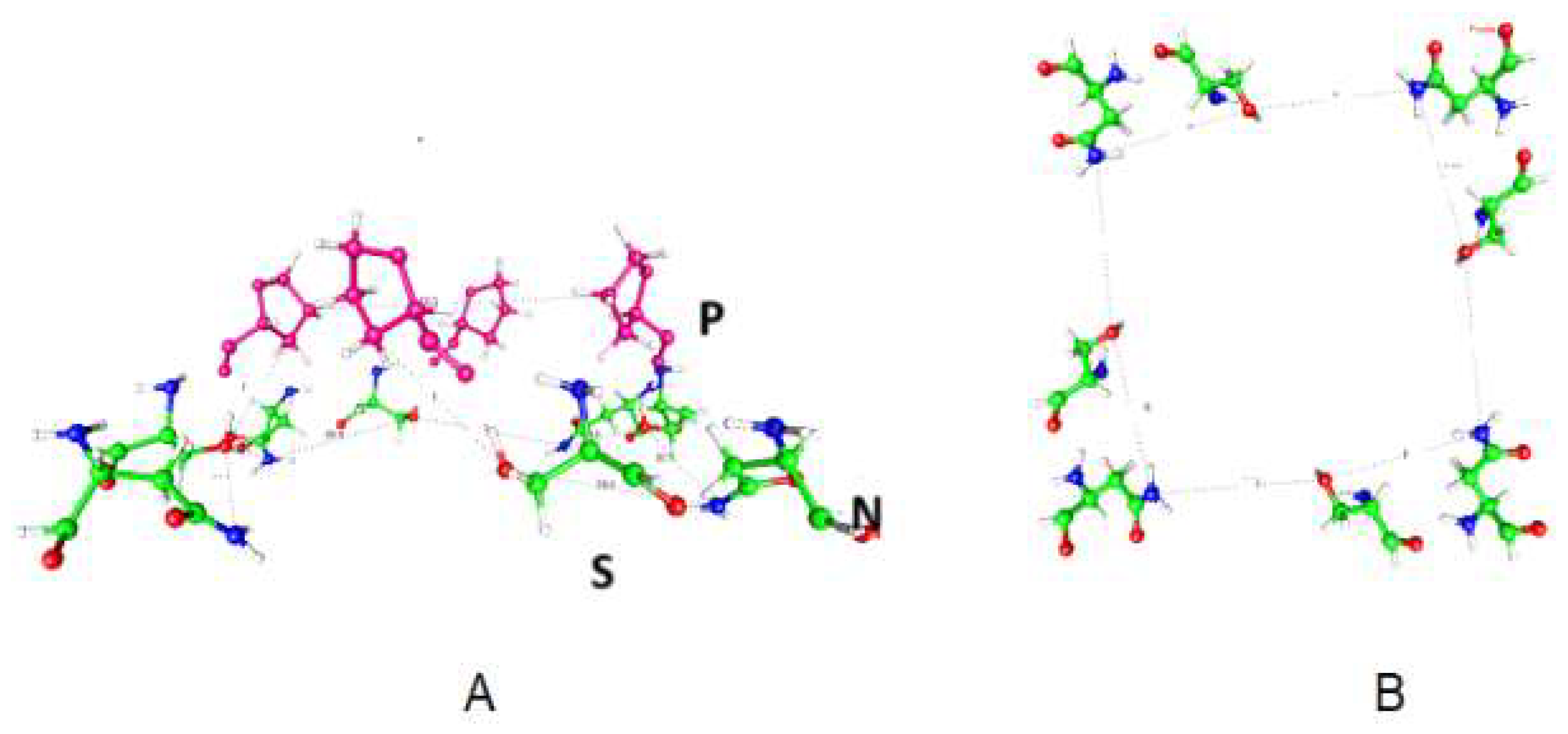

13) In addition to the prolines at the gate, there is another class of conserved residues found in most of the voltage gated potassium channels. These are residues that can transmit a proton. Not all the residues are the same, as some cases have asparagine, some glutamine, and some arginine or else lysine.

However, they occur as triads, and are found near the gate, which must be regarded as a three dimensional region, rather than a planar set of prolines, as in K

V1, or analogous arrrangements in other channels. These triads are found in H

v1, where they are explicitly seen as part of a proton path, and other channels as listed in

Table 1. Fig. 3 shows how the triads are arranged in four cases. There is no reason that proton transmitting moieties should be present in so many channels if it were not for the need to transmit protons.

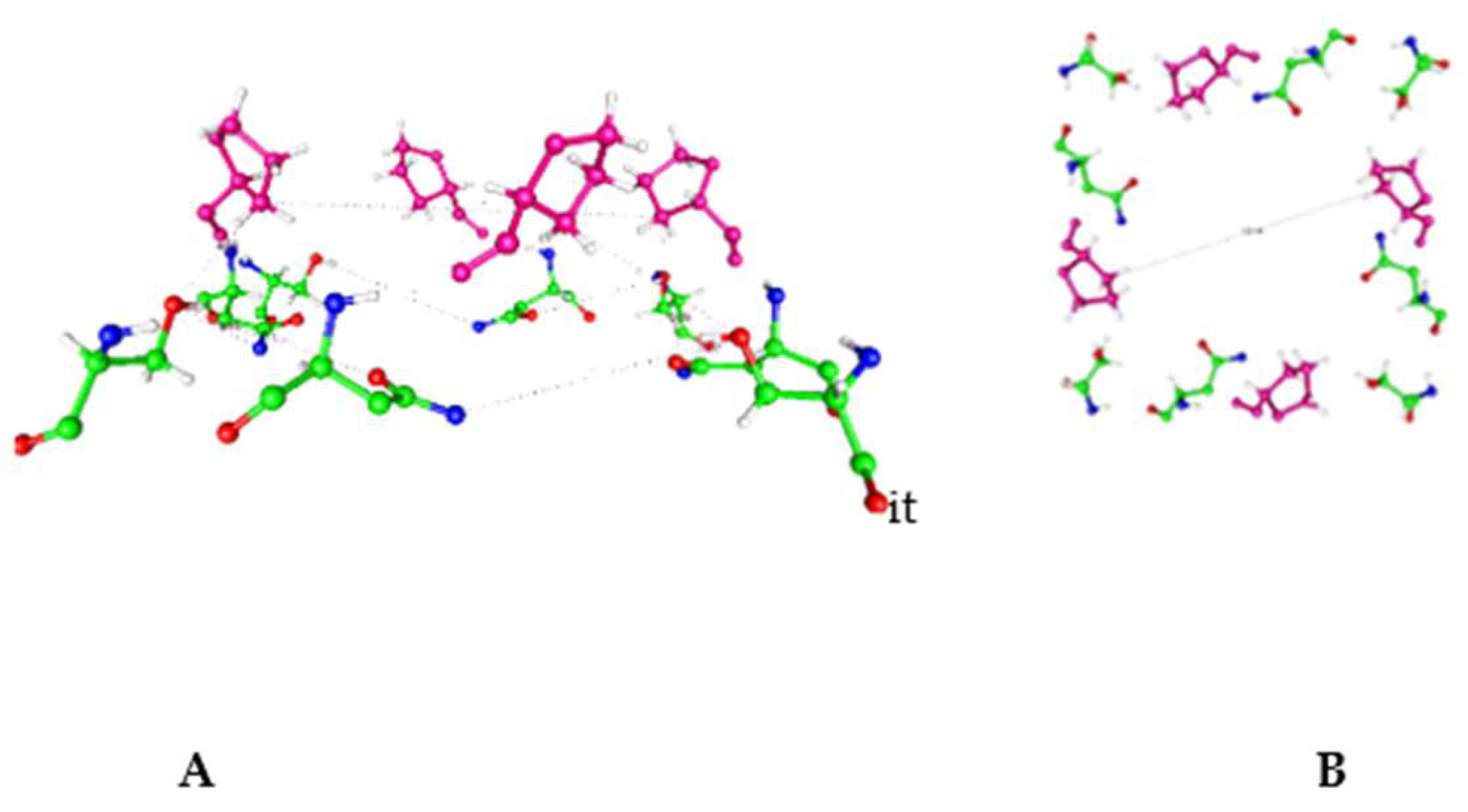

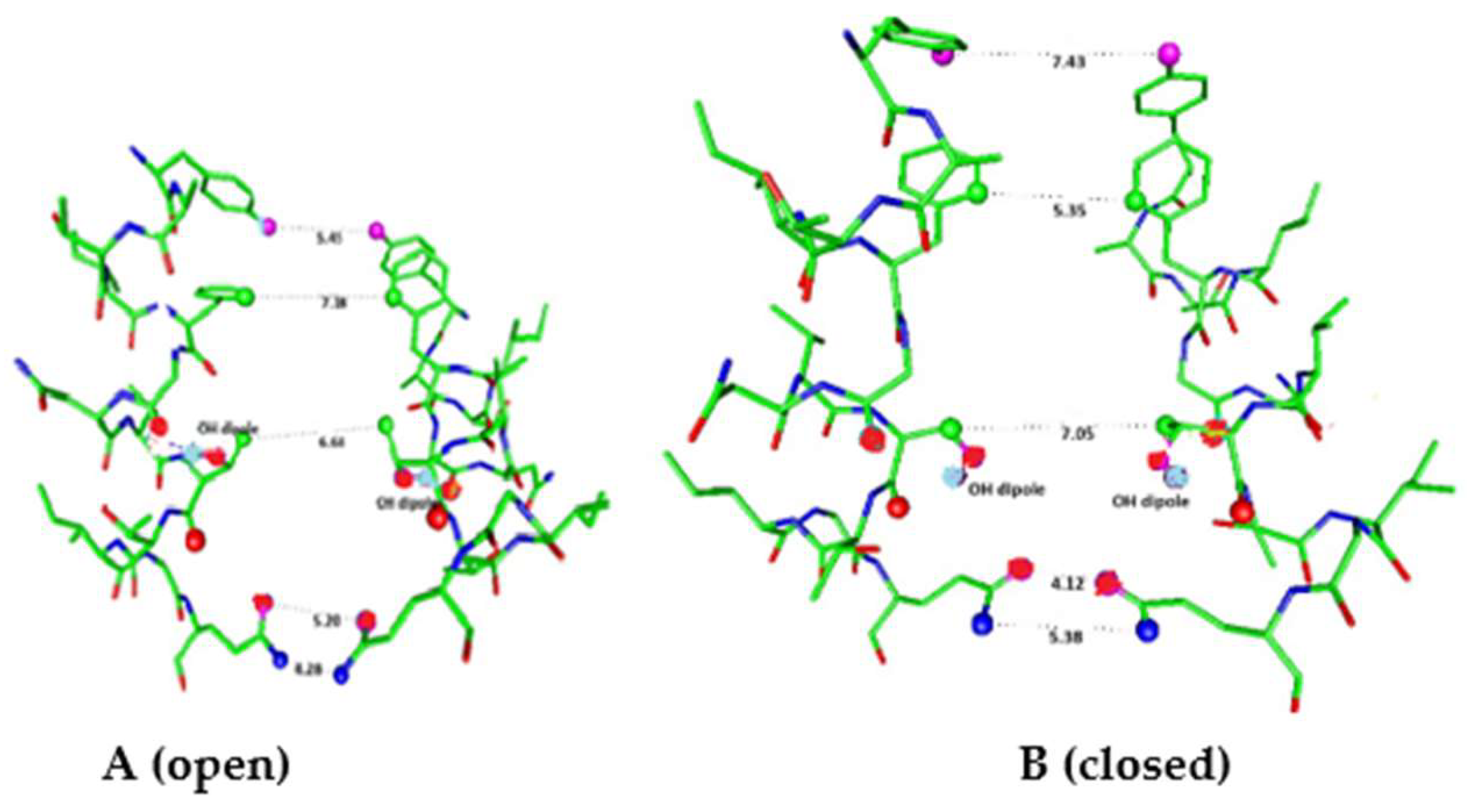

Figure 3.

Views of the amino acids at the gate of K

v1.2 from the pdb 3Lut structure [

45] Shaker is essentially the same.

Figure 3.

Views of the amino acids at the gate of K

v1.2 from the pdb 3Lut structure [

45] Shaker is essentially the same.

- A)

A view looking from the side of the gating region, showing the geometry to be approximately the frustum of a cone. The asparagines (N414) and serines (S411) (green=carbon) are approximately 5 to 8 Å intracellular to the prolines (P407, purple). Serines are closer to the prolines than asparagines. The diagonal distance (C – C of proline) across the opening is 12.3 Å. The serine (near mid-side) oxygen to asparagine nitrogen distances are 6.85 Å for the nearer asparagine and 7.30 Å for the further asparagine. Groupings of three amino acids that are capable of transporting protons (containing S, N, Q, sometimes the N or Q may be repeated, as in QSQ with no N) are found in several potassium channels, and in the proton pathway in Hv1. Occasionally an arginine replaces one of these amino acids. What is important is that a proton-transmitting triad is found shortly before the gate. See Table 1. - B)

The almost planar arrangement of the serines and asparagines of the same channel, this time seen from the intracellular side; these are the same amino acids that form the bottom of part A. The distances are such that a water molecule would almost exactly fit between the side chains.

In looking at Fig. 3, we see several places where water would fit almost exactly. The diagonal of 12.3 Å would fit 2 water molecules plus one ion. The geometry can be most easily understood as forming a framework for water molecules, and holding the ion hydration water, other than the one or two molecules that can enter the cavity, with the others stripped off. The stable configuration appears to have one water on each side of the ion next to the protein side chain. However, further work will be required to work out details. Dehydration alone is not enough; there are multiple species in the gate: K

+, Cl

-, H

2O, protein side chains, and, if this review is correct, H

3O

+ in the closed state. This will necessarily produce a complex network in which there are not only hydrogen bonds, but several types of hydrogen bonds; water-water is only one. There are hydrogen bonds of water to proteins, both permeant and counterions, and electrostatic interactions of the molecules with the ions, in addition to those among the ions. The differences in the network in the open and closed states produce gating. One thing that is certain regardless of gating mechanism is that partial dehydration must occur, because the ion arrives with 6 waters of hydration, and goes through the pore with at most two. It is not so clear how a protein backbone motion could close the channel without major structural disruption, such that it would be difficult to return to this open structure; no apparent side chain motion appears possible that would mechanically close the channel, which would require squeezing out the water, breaking several hydrogen bonds, at a significant energy cost. Other channels like this exist such as K

v2.1. Mechanical interpretations of the amino acid arrangement near the linker – pore junction have been attempted. One of the most interesting is the observation, by Chowdhury et al [

92], that there is an R – E -- Y triad at that location, which they interpret as a hinge that somehow transfers a force from the linker to the pore, opening or closing it. We have interpreted that same triad, which is present also in the VSD [

5] as a proton transmitter. If that triad acts as hinge near the pore, it is hard to see what it is doing in the VSD. However, if proton transport is the function of the triad, then it is consistent with functioning as a proton transmitter, or even source. Barros et al have suggested that there must be a long range allosteric connection between VSD and gate [

93]; protons could appear to make such a connection, if they are transported from one location to another.

it

Figure 4.

A) The view corresponding to Fig 3a, but for channel K

v2.1. We see the same overall shape and the triad of amino acids.

B) The analog of Fig 3B, but including the proline this time. Comparing both figures, note that the -OH on the serine has rotated, which suggests that there may be a difference in proton path, or location, at the edge of the gating region. The diagonal distance shown is 13.14 Å. From pdb 8SD3 [

94].

Figure 4.

A) The view corresponding to Fig 3a, but for channel K

v2.1. We see the same overall shape and the triad of amino acids.

B) The analog of Fig 3B, but including the proline this time. Comparing both figures, note that the -OH on the serine has rotated, which suggests that there may be a difference in proton path, or location, at the edge of the gating region. The diagonal distance shown is 13.14 Å. From pdb 8SD3 [

94].

14)

The EAG channels are also potassium channels, albeit not domain swapped. They do have the normal set of VSDs. Closed and open states have been determined for eag2, and in recent work by Zhang et al, a closed state exists for which there is no movement of S4 [

95]; if S4 does not move, something has to account for the apparent physical closing of the pore, as well as for the gating currents. The narrowest passage near the gate has open and closed states with almost identical diameters, as determined by interatomic distances rather than the Hole algorithm, about 4.2 Å. The authors of this eag2 study did not consider the possibility that protons could have been responsible for the rotations of amino acid side chains that they observe. We could include, as part of the gate, the side chains above the narrowest point, from tyrosine and phenylalanine. Interpreting the effects of these residues is not trivial. However, the tyrosine rotations, and the phenylalanine ring electrons, could easily interact with protons, so this should have been considered, and in fact the results seem most easily accounted for by moving protons; however, while it is possible to identify a proton conduction chain up to the gate region, one would apparently have to assume a water wire beyond that point, so this is only a tentative suggestion at present..

Figure 5.

In a closely related channel, Mandala and MacKinnon have provided cryoEM structures that show actual movement of S4 along the membrane surface. This experiment was done with a high field of 140 mV across the membrane, produced by a potassium concentration gradient (using liposomes as the membranes, but some liposomes were leaky); unlike the natural membrane, there was no phosphatidyl serine (PS) in the inner leaflet of the membrane and this was considered to compensate for the high field. They did not show that the putatively closed structure was reversible [

96]. However, if PS had been present, there is strong probability that the charged phosphate group would form a complex with the arginine that had moved out along the membrane surface [

97,

98]. Such a complex would make it very unlikely for the arginine to return to its original position, ready for another pulse; we consider it therefore probable that this structure is not part of the physiological mechanism by which this channel functions. There is another point concerning these channels that is worth considering. The linker between the voltage sensing domain and the pore can be cut, and there is still gating [99-101]; the explanations that have been proposed are still not clear. However, if water were to insert between the separated parts, and the linker had been functioning as a proton path, this would be consistent with the proton gating model. While these channels are potassium channels, and it has been assumed that they gate in essentially the same manner as domain-swapped channels, the new results suggest that S4-S5 is not a rigid lever. None of the explanations proposed so far include a role for protons, but a water wire could exist even if S4 – S5 were severed, although its properties would be altered. Again the standard model with rigid, or almost rigid, linker, seems not to apply; these channels have up to this point been believed to follow the standard model, but the model must almost certainly be reinterpreted.

Figure 5.

In a closely related channel, Mandala and MacKinnon have provided cryoEM structures that show actual movement of S4 along the membrane surface. This experiment was done with a high field of 140 mV across the membrane, produced by a potassium concentration gradient (using liposomes as the membranes, but some liposomes were leaky); unlike the natural membrane, there was no phosphatidyl serine (PS) in the inner leaflet of the membrane and this was considered to compensate for the high field. They did not show that the putatively closed structure was reversible [

96]. However, if PS had been present, there is strong probability that the charged phosphate group would form a complex with the arginine that had moved out along the membrane surface [

97,

98]. Such a complex would make it very unlikely for the arginine to return to its original position, ready for another pulse; we consider it therefore probable that this structure is not part of the physiological mechanism by which this channel functions. There is another point concerning these channels that is worth considering. The linker between the voltage sensing domain and the pore can be cut, and there is still gating [99-101]; the explanations that have been proposed are still not clear. However, if water were to insert between the separated parts, and the linker had been functioning as a proton path, this would be consistent with the proton gating model. While these channels are potassium channels, and it has been assumed that they gate in essentially the same manner as domain-swapped channels, the new results suggest that S4-S5 is not a rigid lever. None of the explanations proposed so far include a role for protons, but a water wire could exist even if S4 – S5 were severed, although its properties would be altered. Again the standard model with rigid, or almost rigid, linker, seems not to apply; these channels have up to this point been believed to follow the standard model, but the model must almost certainly be reinterpreted.

15)

Vibrations and rotations: There is a hydrogen bond network in the channel, and it goes through the gate. The network is complex, with complications coming from the fact that there are ions in the gate as well; the ions, being charged, are part of the network, and rearrange it. Two dimensional (between graphene sheets) confined water by itself has an altered vibrational spectrum with an additional “fingerprint” peak that has been attributed to what essentially amounts to disruption of the network [

102]. A simulation in a confined layer showed how it was possible for such a confined layer of water to act as a pump [

103]. With both Cl

- and K

+ the structure will be different, but there is little doubt that there are vibrational modes not present in bulk water, or even in ionic solutions. If the gate has a diameter of 1 nm and a thickness also of about 1 nm, the volume is approximately 10

-24 L, which should hold about 30 water molecules at bulk density. This is sufficient for hydration of perhaps five ions, if every water molecule were in a hydration shell. However, with some water occupied by side chains, probably only two or three ions could be fully hydrated, or perhaps four partially hydrated. There must be ions in the gate region, differently hydrated than in bulk; the structure of the region is in turn affected by the ions. Here the density will be different, the ions will take up some of the space and interrupt the network. However, in addition to the ions, the walls of the gate include side chains capable of hydrogen bonding. If the side chains are hydrophilic and polar, they will compete with the ions for the water orientation. Adding protons to the gate must cause a major rearrangement of the network, including altering the polarity of some side chains. The local hydrogen bond network would have to rearrange, probably extensively, to accommodate added protons. This side chain - ion competition plays a major role in dehydrating the ion so that it can pass through the gate; several water molecules must be stripped from the ion hydration shell. Such a rearrangement would necessarily alter the vibrational normal modes of the network. It remains to be shown whether the protonated network has more low frequency modes, hence what it does to the partition function for the system, and thus to the free energy. This question is difficult, and it does not appear to have been considered in the literature. It is not clear how to even begin on solving the problem, as the relevant normal modes may involve different amounts of protein. In addition to vibrations there are rotations, or at least average orientations, that alter the network when protons are added, but rotational degrees of freedom would be more difficult to alter in any way that would have thermodynamic effect. The question of whether one has rotations or these are converted to librations remains to be determined, but librations look more probable in the space available. That said, the orientation of the water must change as ions, including protons, move.

16) There is a substantial

literature concerning the thermodynamic behavior of these channels. The possible hysteresis, observed in many cases, would imply the existence of a memory, thus presumably a non-Markovian mechanism [104-110]. There may be no hysteresis at steady state [

111]. Because the mechanism responsible for this behavior so far is open to multiple interpretations, we do not discuss exactly how the work involved in rearranging the gate to open (which we have here argued is not simply widening the opening) should be calculated, nor whether it matters that the gating is out of equilibrium, and even out of steady state. We note that this is something that remains to be explained by any model. The oscillations in current suggest that the gating is a stochastic process; a simple mechanical model would have difficulty in accommodating this. A simple geometrical structure that is the open state would not allow the current fluctuations; any open state would have to be flexible enough to allow the ions to be tied up briefly, followed by allowing them through. Different channels seem to have different fractions of time they shut down in the presumably open state. There have been a number of theoretical investigations that consider what type of model can be associated with the observed fluctuations, but these do not seem to be tied to specific molecular interactions [112-117]. A relation to lipid fluctuations has been proposed, but has been applied specifically to gramicidin, not a proper membrane channel [

118,

119]. While there seems to be evidence of an important effect of the lipids on channel behavior for some cases, this has not been tied to a mechanism of voltage gating; there is somewhat better evidence of relevance to mechanosensitive channels, which is to be expected, as membrane distortion would exert a force that could be detected by a mechanosensitive channel. Whether a bundle crossing model could unbundle if it is held together mechanically is not a question that we have found discussed in the literature so far. It remains to connect the thermodynamic discussion referred to above to a mechanism. Lipid fluctuations may couple to channel fluctuations, and this might apply to mechanical or proton gating models, but are more likely interactions with the VSD. We have not reviewed these here (see section 16). However, hydrogen bonds are labile, so may be better able to provide a means for the fluctuations.

17) After this discussion of the

probable importance of protons, we have only briefly mentioned, but not really considered, the

quantum properties of protons (references 54 to 60). We did suggest the possibility of tunneling in section [

7] above, on the piquito, which depends on the quantum properties of protons. The proton is a fairly light particle, not like an electron, of course, but still small enough to require consideration of its quantum properties. To begin with, the de Broglie wavelength of a proton with thermal energy at about 300 K is approximately 1.6 Å, about a hydrogen bond length. A free proton is known to be able to be transmitted along a water wire, or equivalent; side chains of serine or threonine, ending in -OH, for example, can participate in moving a proton; the same is true of the amide side chains of glutamine and asparagine.

Table 1, and its accompanying discussion, shows the conservation of glutamine or asparagine with a serine, generally forming a triad of these amino acids near the gate, or just intracellular to it. A proton can be thought of as delocalized over a finite distance on the scale of bond lengths. Even a water molecule would have a de Broglie length close to 0.4 Å at 300 K. Confined water properties, sometimes coupled to delocalized protons, have been investigated by a number of workers (section 13 above). Gervert and coworkers studied bacteriorhodopsin and found a delocalized proton that is likely to be an example [

120]. Prisk et al studied rotations of confined water, finding anomalous behavior [

121], and an anomalous quantum state of protons in nanoscale confined water was reported by Reiter et al [

59,

60]. The main point is that considering the proton as strictly classical is incorrect, especially in a confined space, and even water is unlikely to behave, when confined on this scale, as water does in bulk. The delocalized nature of the proton offers another reason why classical views of the channel gate and the confined space more generally are at best uncertain. Within the substantial literature concerning confined water and proton sharing, there are short hydrogen bonds that have a single potential well between oxygens, or oxygen and nitrogen. In addition, rings can delocalize a proton, or a pair of protons; we found such a case with a ring with two hydrogen bonds [

122]; removing one hydrogen bond destroyed an apparent resonance. Investigations of water and hydrogen bonds, especially in confined spaces, has become an active field of research, and by now shows that ignoring quantum effects in such spaces leads to major errors. We cannot review this field in detail, but will just cite several studies that are concerned with the modes of motion of water, proton tunneling, and quantum effects, on the strength and length of hydrogen bonds [85,123-133]. In short, experimental and theoretical evidence points to the importance of quantum effects for hydrogen bonding, water degrees of freedom (rotational and vibrational) and the structure of groups of hydrogen bonded molecules. A key requirement for a potassium ion to enter the cavity of a channel beyond the gate is that it shed at least four water molecules (see section 4 above). These in turn must become part of a hydrogen bonded network in a confined space. Neglecting quantum effects is almost certain to lead to error. Work now in progress is beginning to point to the nature of the interactions involved, but it will take some time until there is sufficient evidence to provide a detailed picture. The results at this point suggest that only a few side chains move, and the protein backbone is essentially stationary.

18) All this said, there are experiments that appear to be more consistent with the standard model, at least in the simplest reading of the results. These include a certain number of structures, especially of sodium channels, in which what may be taken as closed (resting) or intermediate structures are either found from cryoEM or are based on models, such as Rosetta models, that are considered to be reasonably reliable. Several of these are based on work with the NaChBac channel, a small bacterial sodium channel, or orthologues of this channel [134-136]. These models are interesting but require further examination before they can be considered definitive. For one thing, the interpretations of the models do not consider the possibility that protons might move at all. They test motions of the VSD of NaChBac by coupling cysteines that have been placed by mutation, and appear to couple in milliseconds, a very long time in terms of molecular fluctuations. Of course, there is no direct evidence of such fluctuations, so this may be a valid test, but so far it is open for further examination. There are structures of some other channels as well, including a potassium channel, of the K

V4 family [

137], showing cryoEM structures that include inactivated and intermediate states, as well as a modeled resting structure. Again, there is no consideration of the possibility of proton motion, and the S4 motions are not large—it is not so clear how the putative closed state really couples to closing the gate, although a mechanically closed gate does appear in one cryoEM structure, which may be an inactivated state. We do not rule out the possibility that some protein rearrangements may occur; certainly side chain motions do exist, and we find them in our own calculations. If a side chain rotates into a passage, thus covering 2 Å, and this happens from at least two of the four domains, a passage that had been 5 Å could now become 1 Å, hence mechanically closed without S4 motion in a cryoEM structure. Such cases do not appear to have been reported. However, If the rotation is effected by the motion of a proton, as is certainly possible, this remains conceivable. However, this does not appear to be consistent with the dehydration mechanism for which the evidence is stronger. Nevertheless, it does show how a proton-controlled gate could be responsible for a geometric, mechanical gate closing—in principle. We do not see evidence that this actually happens.

19) Omissions from this review: We have not discussed at least two topics that are possibly relevant. First, lipids have been reported to affect gating, and second, we have not considered the current – voltage curve, which looks like that of a standard rectifier; it shows how an external potential, in the conducting direction, produces a current roughly proportional to the potential. The reason for omitting the lipids is that it appears, from our reading of the literature, that the lipids might influence the probability of producing protons or a proton cascade in the VSD, rather than alter the network of interactions at the gate. The lipids do not appear to stretch all the way to the gate entrance; however, S4 of the VSD may interact with the lipid; possibly the other transmembrane segments may also interact. These interactions are not relevant to the question we are dealing with here, at least not directly relevant. Second, the potential may increase current by affecting the probability of transitions among local minima required for an ion to move forward in the already open configuration of the gate, while we are here concerned with the closed → open transition.

20) A speculation that grows out of the proton gating model: It is difficult to see how complex channels, like the Kv1 channels, or close relatives, could evolve in a single step. There is the voltage sensing domain, the linker, and the pore segment. If all evolved together, a mechanical connection would require that everything fit perfectly on the first try. No obvious precursors for a voltage gated channel with mechanical linkage are apparent. The simpler channels that exist, such as KcsA and Hv1, look like parts of the Kv channel. Having these come together as precursors could form a single functional unit, with a water hydrogen bond network acting as the linker in the original form of a voltage gated channel; the linker could become more efficient with further evolution. Nothing is known resembling a precursor to the linker itself. On the other hand, if protons are responsible for the gating, the KcsA channel becomes a pore precursor, while the Hv1 channel, which looks very like a VSD, can be a VSD precursor. The Hv1 exists primarily as a dimer, so if two Hv1 dimer channels attach, even at a slight distance, from a KcsA-like channel, one has a possible voltage gated channel with voltage sensing domains like those of Kv channels. At this point, there is no direct evidence relevant to this hypothesis, but it is more plausible than the direct de novo evolution of a complete Kv1-like channel. While there is substantial literature on the evolutionary relationships among Kv channels, which we do not review here, the origin of such a channel does not seem to be so clear. That said, this paragraph is only a suggestion, and as yet lacks direct evidence.

SUMMARY: There are a number of experiments that are consistent with proton gating; some of these have been interpreted as consistent with the standard model of gating, in which S4 moves to close the channel pore through a mechanical linker; others have been ignored, perhaps to be interpreted at some time in the future. As far as we can see, all these experiments can be interpreted in terms of the proton gating model. There is an experiment that is consistent with proton tunneling to start a possible proton cascade; the Hv1 channel shows that proton transport is possible in the VSD, and a somewhat similar path exists in the M2 channel. Experiments that seemed to show cysteine traveling to the membrane surface so that they could relate to MTS do not prove that S4 has physically moved, as cysteine can ionize in situ. Molecular Dynamics simulations have serious defects, not least that they often use a bad model for water, and do not allow charge transfer. Those MD simulations that attempt to simulate gating require unrealistic potentials; with realistic potentials, S4 does not move. It is also hard to see how these could be reversible on removal of the voltage. Quantum effects cannot be taken into account in a classical simulation, but the dimensions of the gate, and the size of the deBroglie wavelength of a thermal proton, suggest that ignoring these effects will lead to serious error.. Finally, the fact that at least some closed state can exist without S4 motion, for example in the EAG channel, and in KirBac 1.1, means that S4 motion is not required for gating; deciding which gating mechanism is correct in the physiological case is a matter for further experiment. The proton gating model is consistent with some specific experiments: substitution of serine and of aspartate at the gate, the effect of D2O, the piquito, and the effect of T1. The standard model, in most of its forms, does not consider the water at the membrane surface, or in the gate region, in appropriate detail. At this point the proton gating model is therefore at least plausible; the role of protons and hydration must be taken into account in interpretation of all data on ion channel structure and function.

References

- Doyle, D.A.; Cabral, J.M.; Pfuetzner, R.A.; Kuo, A.; Gulbis, J.M.; Cohen, S.L.; Chait, B.T.; MacKinnon, R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science 1998, 280, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.E. Electrorheological effects and gating of membrane channels. J.Theor. Biol. 1989, 138, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariev, A.M.; Green, M.E. Caution is required in interpretation of mutations in the voltage sensing domain of voltage gated channels as evidence for gating mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariev, A.; Green, M.E. Protons in Gating the Kv1.2 Channel: A Calculated Set of Protonation States in Response to Polarization/Depolarization of the Channel, with the Complete Proposed Proton Path from Voltage Sensing Domain to Gate. Membranes 2022, 12, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariev, A.M.; Green, M.E. Quantum Calculation of Proton and Other Charge Transfer Steps in Voltage Sensing in the Kv1.2 Channel. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 7984–7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariev, A.M.; Green, M.E. Water, Protons, and the Gating of Voltage Gated Potassium Channels. Membranes 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, V.V.; Morgan, D.; DeCoursey, T.E.; Musset, B.; Chaves, G.; Smith, S.M.E. Tryptophan 207 is crucial to the unique properties of the human voltage-gated proton channel, hHV1. J Gen Physiol 2015, 146, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, V.V.; Morgan, D.; Thomas, S.; Smith, S.M.E.; DeCoursey, T.E. Histidine168 is crucial for ΔpH-dependent gating of the human voltage-gated proton channel, hHV1. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018, 150, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoursey, T.E. Voltage-gated proton channels. Compr Physiol 2012, 2, 1355–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Kurokawa, T.; Takeshita, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Okochi, Y.; Nakagawa, A.; Okamura, Y. The cytoplasmic coiled-coil mediates cooperative gating temperature sensitivity in the voltage-gated H+ channel Hv1. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1823–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Sakata, S. Gating mechanisms of voltage-gated proton channels. Annu Rev Biochem 2015, 84, 685–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonamnaj, P.; Sompornpisut, P. Effect of Ionization State on Voltage-Sensor Structure in Resting State of the Hv1 Channel. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 2864–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, V.; Ramsey, I.S. Gating Currents in the Hv1 Proton Channel. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 2844–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoursey, T.E. Voltage and pH sensing by the voltage-gated proton channel, HV1. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20180108–20180101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianti, E.; Delemotte, L.; Klein, M.L.; Carnevale, V. On the role of water density fluctuations in the inhibition of a proton channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, E8359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, Y.; Okochi, Y. Molecular mechanisms of coupling to voltage sensors in voltage-evoked cellular signals. Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B 2019, 95, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, A.L.; Mokrab, Y.; Bennett, A.L.; Sansom, M.S.; Ramsey, I.S. Proton currents constrain structural models of voltage sensor activation. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolov, V.S.; Cherny, V.V.; Ayuyan, A.G.; DeCoursey, T.E. Analysis of an electrostatic mechanism for ΔpH dependent gating of the voltage-gated proton channel, Hv1, supports a contribution of protons to gating charge. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2021, 1862, 148480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islas, L.D. The acid test for pH-dependent gating in cloned HV1 channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018, 150, 781–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coursey, T.E. CrossTalk proposal: Proton permeation through HV1 requires transient protonation of a conserved aspartate in the S1 transmembrane helix. J. Physiol. (Oxford, U. K.) 2017, 595, 6793–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banh, R.; Cherny, V.V.; Morgan, D.; Musset, B.; Thomas, S.; Kulleperuma, K.; Smith, S.M.E.; PomA s, R.; DeCoursey, T.E. Hydrophobic gasket mutation produces gating pore currents in closed human voltage-gated proton channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 18951–18961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, V.V.; Musset, B.; Morgan, D.; Thomas, S.; Smith, S.M.E.; Decoursey, T.E. Engineered high-affinity zinc binding site reveals gating configurations of a human proton channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020, 152, e202012664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelenter, M.D.; Mandala, V.S.; Niesen, M.J.M.; Sharon, D.A.; Dregni, A.J.; Willard, A.P.; Hong, M. Water orientation and dynamics in the closed and open influenza B virus M2 proton channels. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schauf, C.L.; Bullock, J.O. Solvent substitution as a probe of channel gating in Myxicola: differential effects of D2O on some components of membrane conductance. Biophys,. J. 1980, 30, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauf, C.L.; Bullock, J.O. Solvent substitution as a probe of channel gating in Myxicola. Biophys,. J. 1982, 37, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauf, C.L.; Bullock, J.O. Modifications of sodium channel gating in Myxicola giant axons by deuterium oxide, temperature, and internal cations. Biophys,. J. 1979, 27, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, M.D.; Starkus, J.G. The steady-state distribution of gating charge in crayfish giant axons. Biophys J 1989, 55, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicata, D.A.; Rayner, M.D.; Starkus, J.G. Sodium channel activation mechanisms. Insights from deuterium oxide substitution. Biophys J 1990, 57, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkus, J.G.; Rayner, M.D. Gating current "fractionation" in crayfish giant axons. Biophys J 1991, 60, 1101–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.X.; Lynch, C.I.; Crain, J.; Sansom, M.S.P.; Tucker, S.J. Influence of effective polarization on ion and water interactions within a biomimetic nanopore. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 2014–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanto, T.G.; Gaal, S.; Karbat, I.; Varga, Z.; Reuveny, E.; Panyi, G. Shaker-IR K+ channel gating in heavy water: role of structural water molecules in inactivation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021, 153, e202012742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szanto, T.G.; Papp, F.; Zakany, F.; Varga, Z.; Deutsch, C.; Panyi, G. Molecular rearrangements in S6 during slow inactivation in Shaker-IR potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2023, 155, e202313352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhareva, M.; Hackos, D.H.; Swartz, K.J. Constitutive activation of the shaker Kv channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003, 122, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Franulic, I.; Sepulveda, R.V.; Navarro-Quezada, N.; Gonzalez-Nilo, F.; Naranjo, D. Pore dimensions and the role of occupancy in unitary conductance of Shaker K channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2015, 146, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackos, D.H.; Chang, T.H.; Swartz, K.J. Scanning the intracellular s6 activation gate in the Shaker K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002, 119, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.-X.; de Groot, B.L. Central cavity dehydration as a gating mechanism of potassium channels. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, E.C.; Bagneris, C.; Naylor, C.E.; Cole, A.R.; D'Avanzo, N.; Nichols, C.G.; Wallace, B.A. Structure of a bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel pore reveals mechanisms of opening and closing. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 2077–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montini, G.; Booker, J.; Sula, A.; Wallace, B.A. Comparisons of voltage-gated sodium channel structures with open and closed gates and implications for state-dependent drug design. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, D.L., Jr.; Lin, Y.-F.; Mobley, B.C.; Avelar, A.; Jan, Y.N.; Jan, L.Y.; Berger, J.M. The polar T1 interface is linked to conformational changes that open the voltage-gated potassium channel. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2000, 102, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariev, A.M.; Green, M.E. Protons in Gating the Kv1.2 Channel: A Calculated Set of Protonation States in Response to Polarization/Depolarization of the Channel, with the Complete Proposed Proton Path from Voltage Sensing Domain to Gate. Membranes (Basel, Switz.) 2022, 12, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, S.J.; Nanao, M.H.; Jahng, A.W.; DeRubeis, D.; Choe, S.; Pfaffinger, P.J. Voltage dependent activation of potassium channels is coupled to T1 domain structure. Nat. Struct Biol 2000, 7, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stefani, E.; Sigg, D.; Bezanilla, F. Correlation between the early component of gating current and total gating current in Shaker K channels. Biophysical Journal 2000, 78, 7A. [Google Scholar]

- Sigg, D.; Bezanilla, F.; Stefani, E. Fast gating in the Shaker K+ channel and the energy landscape of activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 2003, 100, 7611–7615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiff, L.I. Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Ni, F.; Ma, J. Structure of the full-length Shaker potassium channel Kv1.2 by normal-mode-based X-ray crystallographic refinement. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. 2010, 107, 11352–11357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, O.K.; Wuskell, J.P.; Loew, L.M.; Bezanilla, F. A Fluorometric Approach to Local Electric Field Measurements in a Voltage-Gated Ion Channel. Neuron 2003, 37, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Horn, R. Evidence for voltage-dependent S4 movement in sodium channels. Neuron 1995, 15, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Horn, R. Movement and crevices around a sodium channel S3 segment. J. Gen'l. Physiol. 2002, 120, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, V.; Stack, K.; Boric, K.; Naranjo, D. Reduced voltage sensitivity in a K+-channel voltage sensor by electric field remodeling. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. 2010, 107, 5178–5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Perez, V.; Stack, K.; Boric, K.; Naranjo, D. Reduced voltage sensitivity in a K+-channel voltage sensor by electric field remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 5178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Deviations from Ohm's Law in Weak Electrolytes. J. Chem. Phys. 1934, 2, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasham, J.; Djurabekova, A.; Zickermann, V.; Vonck, J.; Sharma, V. Role of Protonation States in the Stability of Molecular Dynamics Simulations of High-Resolution Membrane Protein Structures. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2024, 128, 2304–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, C.I.; Rao, S.; Sansom, M.S.P. Water in Nanopores and Biological Channels: A Molecular Simulation Perspective. Chem. Rev. (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2020, 120, 10298–10335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, R.; Gorgol, M.; Kierys, A.; Maheshwari, P.; Pietrow, M.; Pujari, P.K.; Zgardzinska, B. Unraveling the Phase Behavior of Water Confined in Nanochannels through Positron Annihilation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 5916–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galitskaya, E.A.; Zavorotnaya, U.M.; Ryzhkin, I.A.; Sinitsyn, V.V. Model of confined water self-diffusion and its application to proton-exchange membranes. Ionics 2021, 27, 2717–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Duan, M.; Xie, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, M.; Liu, M.; Yang, J. Fast collective motions of backbone in transmembrane α helices are critical to water transfer of aquaporin. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eade9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvil, H.T.; Watkins, L.C.; Mravic, M.; Thomaston, J.L.; Nicoludis, J.M.; Somberg, N.H.; Liu, L.; Hong, M.; Voth, G.A.; DeGrado, W.F. Transient water wires mediate selective proton transport in designed channel proteins. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, S.D.E.; Hewage, K.S.K.; Eitel, A.R.; Struts, A.V.; Weerasinghe, N.; Perera, S.M.D.C.; Brown, M.F. Hydration-mediated G-protein-coupled receptor activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, e2117349119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, G.; Burnham, C.; Homouz, D.; Platzman, P.M.; Mayers, J.; Abdul-Redah, T.; Moravsky, A.P.; Li, J.C.; Loong, C.K.; Kolesnikov, A.I. Anomalous Behavior of Proton Zero Point Motion in Water Confined in Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 247801–247801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, G.F.; Kolesnikov, A.I.; Paddison, S.J.; Platzman, P.M.; Moravsky, A.P.; Adams, M.A.; Mayers, J. Evidence for an anomalous quantum state of protons in nanoconfined water. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2012, 85, 045403–045401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, G.F.; Deb, A.; Sakurai, Y.; Itou, M.; Kolesnikov, A.I. Quantum Coherence and Temperature Dependence of the Anomalous State of Nanoconfined Water in Carbon Nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 4433–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.I.; Reiter, G.F.; Choudhury, N.; Prisk, T.R.; Mamontov, E.; Podlesnyak, A.; Ehlers, G.; Seel, A.G.; Wesolowski, D.J.; Anovitz, L.M. Quantum tunneling of water in beryl: a new state of the water molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 167802–167801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Yoon, B.J. Observation of the thermal influenced quantum behaviour of water near a solid interface. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, V.N.; Sokolov, A.P. Quantum effects in dynamics of water and other liquids of light molecules. Eur. Phys. J. E: Soft Matter Biol. Phys. 2017, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhkin, M.I.; Ryzhkin, I.A.; Kashin, A.M.; Zavorotnaya, U.M.; Sinitsyn, V.V. Quantum Protons in One-Dimensional Water. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 8100–8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, M.R.; Nguyen, M.N.; Kannan, S.; Fox, S.J.; Kwoh, C.K.; Lane, D.P.; Verma, C.S. Characterization of Hydration Properties in Structural Ensembles of Biomolecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 3316–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setny, P. Conserved internal hydration motifs in protein kinases. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2020, 88, 1578–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchenko, A.P. Proton transfer reactions: From photochemistry to biochemistry and bioenergetics. BBA Adv. 2023, 3, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobhia, M.E.; Ghosh, K.; Kumar, G.S.; Sivangula, S.; Laddha, K.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, H. The Role of Water Network Chemistry in Proteins: A Structural Bioinformatics Perspective in Drug Discovery and Development. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2022, 22, 1636–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carugo, O. Statistical survey of the buried waters in the Protein Data Bank. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, M.; Fayed, T.A.; El-Nahass, M.N.; Diab, H.A.; El-Gamil, M.M. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization and biological evaluation of a novel chemosensor with different metal ions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 33, e5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellissent-Funel, M.-C.; Hassanali, A.; Havenith, M.; Henchman, R.; Pohl, P.; Sterpone, F.; van der Spoel, D.; Xu, Y.; Garcia, A.E. Water Determines the Structure and Dynamics of Proteins. Chem. Rev. (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2016, 116, 7673–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]