1. Introduction

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) is an uncommon and challenging condition to diagnose. It includes a spectrum of conditions caused by the compression of neurovascular structures within the thoracic outlet, a space bordered by the clavicle, first rib, and scalene muscles.[

1] Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is classified into three subtypes based on the anatomical structure involved: neurogenic TOS (nTOS), resulting from brachial plexus compression; venous TOS (vTOS), due to subclavian vein compression; and arterial TOS (aTOS), involving compression of the subclavian artery.[

1]

TOS in pediatric populations is relatively rare compared to adults and often present with vague, nonspecific symptoms, such as neck or shoulder pain and upper extremity discomfort, leading to frequent misdiagnoses or delays in diagnosis.[

2,

3] Traditional diagnostic tools, including provocative maneuvers and imaging modalities, often fail to provide conclusive evidence due to limited cooperation from young patients and the dynamic nature of TOS.[

4,

5] Additionally, pediatric TOS diagnosis is frequently delayed (2-60 months) due to extensive diagnostic imaging and consulting multiple specialists.[

6] Treatment for TOS primarily included muscle resection, followed by neurolysis and bone resection, with frequent overlap in procedures that included two or more of these interventions. Patients with early-stage TOS can be treated with conservative management, such as rest and correcting posture.[

7] However, it is difficult to diagnose in early-stage TOS. Surgical intervention is regarded as a definitive treatment targeting the underlying cause of thoracic outlet syndrome. In pediatric patients, early decompression is particularly important due to ongoing growth and development,[

7] which may exacerbate symptoms or lead to long-term functional impairment if left untreated.

Anterior Scalene Muscle Block (ASMB) offers a minimally invasive diagnostic alternative, particularly in neurogenic cases. ASMB temporarily alleviates compression through targeted muscle relaxation and may serve as a confirmatory tool for nTOS and help predict invasive surgical intervention.[

1,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] Its role has been described as a diagnostic tool in adults, but data on its utility in pediatric populations remains sparse.

In this case report, we demonstrate the successful use of ASMB for diagnostic confirmation and surgical decision-making in pediatric patients with suspected neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. The report highlights ASMB’s value in ensuring accurate diagnosis and guiding surgical treatment planning for pediatric TOS, addressing a gap in the current literature.

2. Case Descriptions

2.1. Case 1

A 12-year-old girl, weighing 48.9kg, presented with a 9-month history of progressively worsening neurologic symptoms in her right upper extremity. Before consultation with the acute pain service for diagnostic ASMB, the patient had been evaluated by multiple specialists and underwent extensive diagnostic testing and conservative treatment. However, none of the interventions provided definitive symptom relief. She was subsequently referred to our service to assist in confirming a diagnosis of TOS using ASMB. Her symptoms began suddenly following intense exercise and initially manifested as numbness, tingling, weakness, and swelling in the wrist, hand, and proximal forearm, later spreading to the entire arm. She also reported worsened tingling in her right upper extremity when her shoulders were elevated. She experienced daily flare-ups, along with hand discoloration. Over time, the symptoms intensified, with an increasing frequency of edema and a purplish discoloration of the hand. Although she reported no pain, functional limitations prompted her to switch from right- to left-handed for tasks such as handwriting. The patient also reported headaches accompanied by photophobia and occasional phonophobia. Although she had a remote history of migraines with aura, the current symptoms were subjectively different. On physical examination, peripheral pulses were intact with no evidence of vascular compromise. The Elevated Arm Stress Test (EAST) reproduced tingling sensations in the right fingers, suggesting neurogenic involvement. In contrast, the Adson test (used to assess for nTOS) and the Wright test (to evaluate for vTOS) were unremarkable. Neurologic examination revealed right-hand weakness (4/5), numbness throughout the arm, and mild swelling in the forearm and hand. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies were performed twice, yielding normal results. Chest magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) demonstrated positional compression of the subclavian vein without evidence of thrombosis, raising concern for nTOS. Given the diagnostic uncertainty, an ASMB was requested to aid in the definitive diagnosis of nTOS and to guide the consideration of invasive surgical intervention.

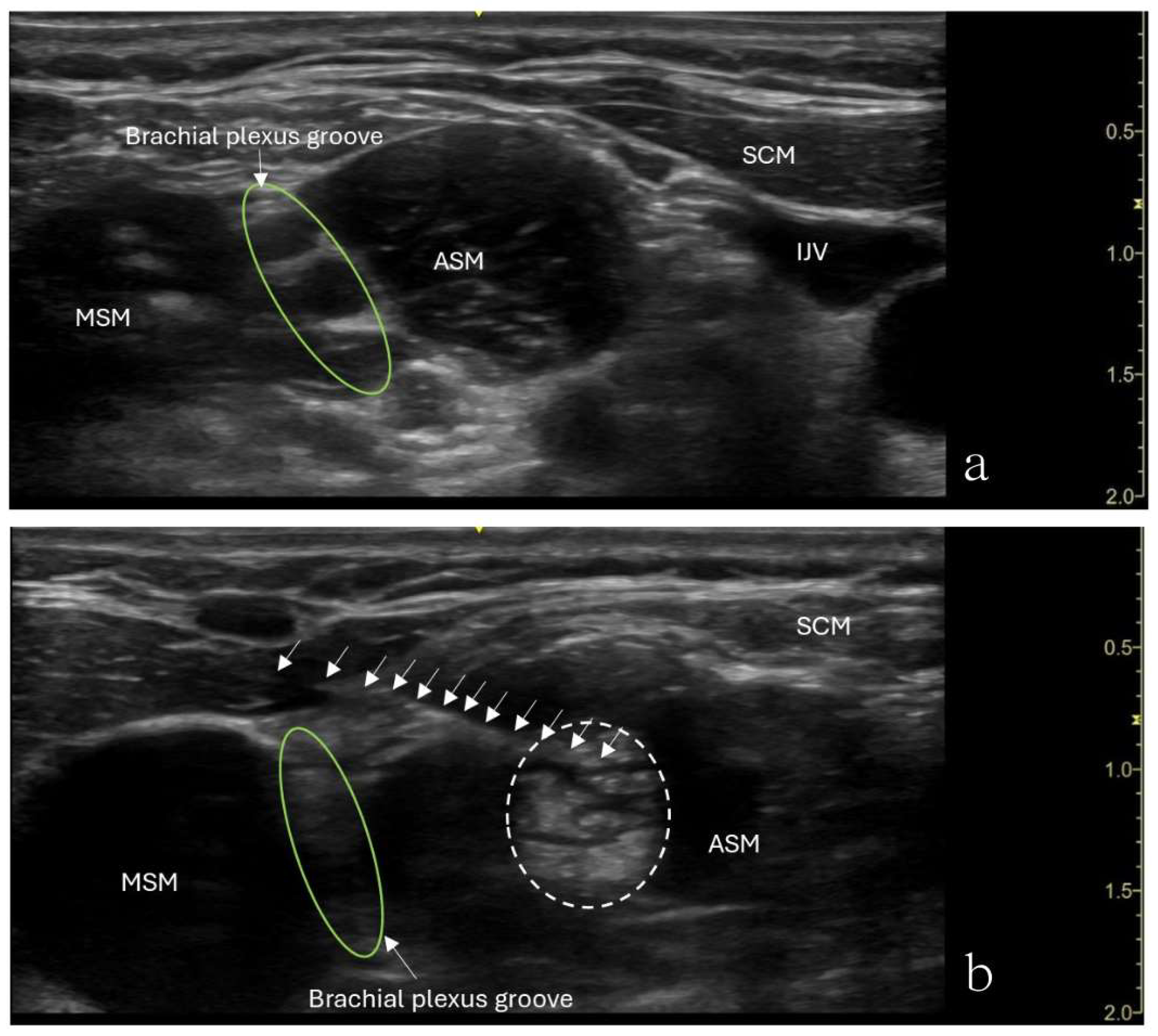

The patient underwent an ultrasound-guided right anterior scalene muscle block under minimal sedation. A high-frequency linear probe was used to identify the anterior scalene muscle (

Figure 1). After sterile preparation, A 22-gauge, 50-mm Sono-TAP needle (PAJUNK

®, Germany), using an in-plane technique, was advanced from the posterior aspect of the neck anteriorly and was inserted into the middle of the anterior scalene muscle. After negative aspiration for blood, 5 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine was slowly injected in increments. An increased muscle size was noticed with no medication extravasation to the brachial plexus divisions (

Figure 1). Sixty minutes after the procedure, the patient’s preexisting numbness disappeared, and her hand strength improved. She experienced no numbness when raising her arm. However, she reported shoulder heaviness and slight weakness, though she had a full range of motion. By 4 hours after the procedure, the weakness in her right shoulder had disappeared. Around 5 hours post-procedure, numbness began returning, starting in the small finger and spreading through the entire arm. Despite this, her hand strength improved, enabling her to write and color.

Following the ASMB procedure, the patient was considered a candidate for surgery, and a few months later, she underwent first rib excision and brachial plexus neurolysis. At one-month postoperative follow-up, the patient’s symptoms had entirely resolved. The use of ASMB increased the likelihood of a TOS diagnosis, leading to a direct referral to the TOS clinic. Although the patient had to wait a few months for the invasive procedure due to age considerations, symptoms were effectively managed with botulinum toxin injections into the anterior scalene muscle under the diagnosis of nTOS. This approach allowed the patient to eventually undergo the surgical procedure.

2.2. Case 2

A 15-year-old girl, weighing 54.8kg, developed progressively worsening right upper extremity pain (8-9/10) over 9 months, initially associated with volleyball activities. Additional symptoms included sharp, radiating pain from the right shoulder to the fingers, paresthesia, decreased sensation, and daily headaches from the neck to the orbital region. The orthopedic clinic initially evaluated the patient, where bone-related injuries and alignment abnormalities were ruled out. Subsequent neurological assessments included brain and cervical spine MRI, both being unremarkable. During this period, she underwent physical therapy and was managed with medications such as diazepam, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen, but experienced no significant symptom improvement. She was ultimately referred to the thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) clinic for further evaluation. In the interim, for a definitive diagnosis, she was also referred to the acute pain service for ASMB. Her physical exam revealed trapezius muscle spasms, restricted cervical motion, and pain with arm abduction. Dynamic imaging showed right subclavian vein compression in the costoclavicular space during abduction, raising suspicion for TOS.

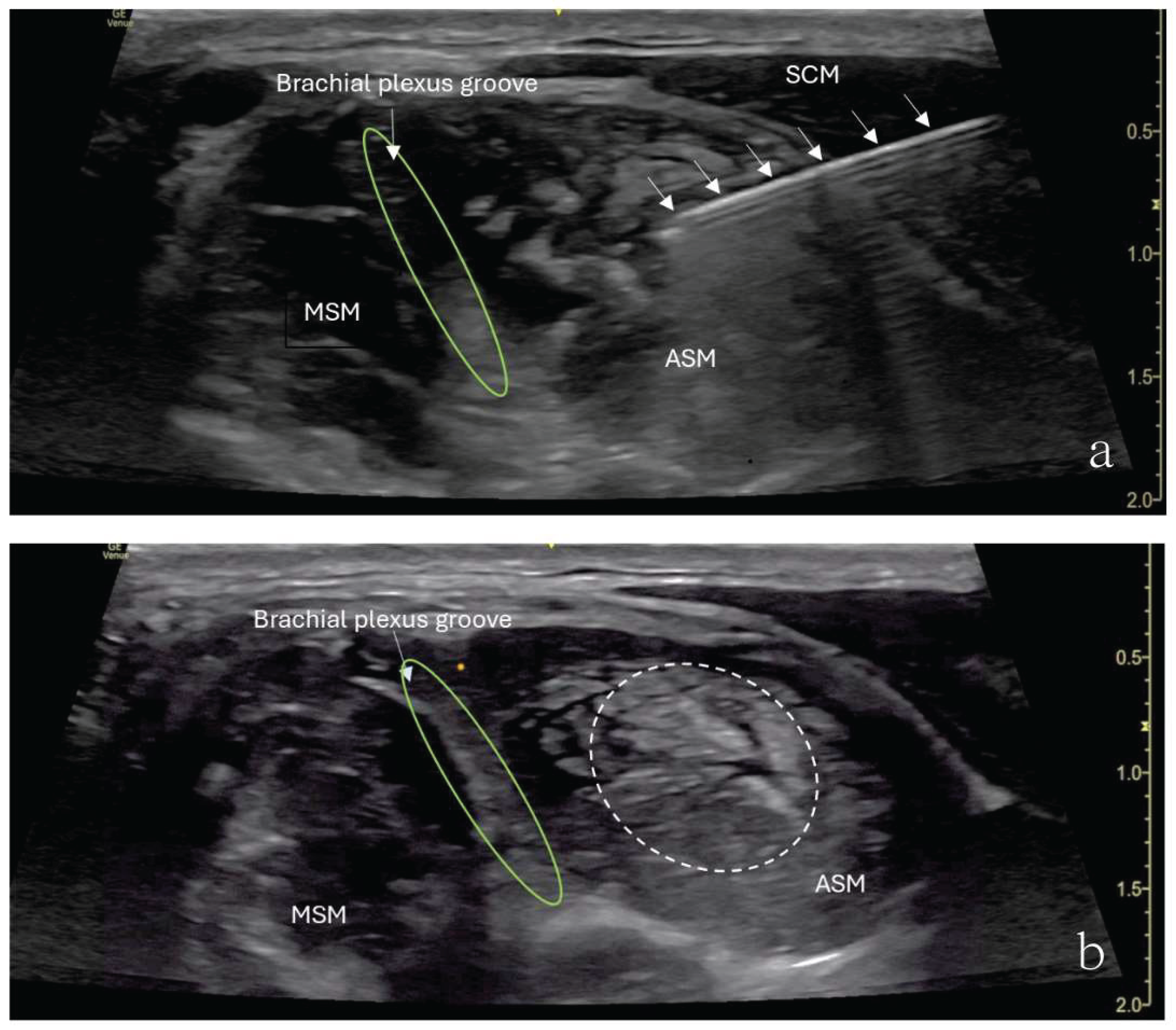

The patient underwent ultrasound-guided ASMB under minimal sedation. A high-frequency linear ultrasound probe identified the anterior scalene muscle and adjacent neurovascular structures. After sterile preparation, a 24-gauge, 40-mm Sono-TAP needle (PAJUNK

®, Germany), using an in-plane approach, was advanced from the anterior aspect of the neck posteriorly and was inserted into the middle of the anterior scalene muscle (

Figure 2). After negative aspiration, 5 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine was injected incrementally (

Figure 2). The block provided immediate pain relief, and there was no numbness in the right upper extremity when the arm was elevated or abducted. However, the patient developed right-sided Horner’s syndrome and experienced weakness in the right shoulder, both of which resolved shortly after the procedure. Her preexisting symptoms were resolved for approximately 3 hours following the block.

One month later, the patient underwent a first rib excision. Postoperatively, the patient reported a significant reduction in pain and complete resolution of paresthesia in the arm and hand. Symptom relief following ASMB led to direct referral back to the TOS clinic, where the surgeon decided to proceed with the invasive surgical procedure. Both the patient and the patient’s parents expressed satisfaction with ASMB as a diagnostic tool and its role in guiding further treatment.

3. Discussion

Initially introduced in 1934 for scalenus anticus syndrome, ASMB is now a valuable diagnostic tool for TOS.[

10,

13] This technique involves injecting a local anesthetic into the anterior scalene muscle to relax it, temporarily reducing pressure on neurovascular structures.[

8] If symptoms improve, this indicates that compression in this region contributes to TOS, supporting the presumed diagnosis.[

9]

Several studies have demonstrated ASMB’s diagnostic value. Braun et al. reported improved work performance in suspected TOS patients,[

9] Beason et al. identified correlations with postoperative outcomes,[

10] and Rached et al. observed pain and functional improvements following ultrasound-guided ropivacaine injections.[

12] Although ASMB is well-established in adult TOS diagnosis, its role in pediatric patients remains underexplored. No large series of pediatric and young adult TOS exists in the literature, leaving optimal diagnosis tools and treatment unclear.

These cases highlight its clinical utility in adolescents, where TOS diagnosis is challenging due to its rarity, nonspecific symptoms, and overlap with other musculoskeletal and neurological conditions. ASMB provides immediate symptom relief, confirms neurovascular compression, and facilitates timely diagnosis. It can reduce the need for extensive imaging studies and specialist consultations, allowing for earlier intervention.

ASMB requires the needle to be inserted into the anterior scalene muscle to avoid the risk of inadvertent brachial plexus block. In the first patient, the needle direction from the back towards the front led to shoulder weakness. We suspected local anesthetic backflow along the needle track during the injection and traveled toward the trunk of the brachial plexus. To avoid this recurring, the direction from the front towards the back was adopted for the injection for the second patient, which was very gradually delivered to ensure the medication was being administered in the muscle. Unfortunately, the second patient showed temporary signs suggestive of a partial block of the brachial plexus and Horner’s Syndrome. The anesthetic, when given into the scalene muscle, possibly diffused towards the trunk of the brachial plexus at the level of the triangle of the scalene muscles or blocked the trunk of the brachial plexus passing through the anterior scalene muscle.[

7] Less risk for a partial block of the brachial plexus can be achieved using a smaller volume of the local anesthetic, though pediatrics guidelines are unavailable.

In both cases, patients underwent surgical intervention after experiencing significant symptom relief with ASMB. The favorable outcomes support the utility of ASMB as a diagnostic adjunct and a tool for guiding surgical decision-making in TOS.

This report is not without limitations. ASMB provides only temporary symptom relief and is not a definitive test for TOS; it should be interpreted alongside other diagnostic methods. Additionally, most ASMB research focuses on adults with limited pediatric data.

In conclusion, these case reports demonstrate ASMB’s value as a diagnostic tool for pediatric nTOS, offering immediate symptom relief and confirming neurovascular compression. ASMB helps guide treatment decisions, including surgery, with temporary and self-limiting side effects. While effective, further studies are necessary to refine its role in pediatric care and optimize its clinical application.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All methods used in this article were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient and their guardian gave written Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) authorization for this case report. This case report does not include any trials, drug use and/or invasive practice that require approval from the ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from child’s parents for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dengler, N.F.; Ferraresi, S.; Rochkind, S.; Denisova, N.; Garozzo, D.; Heinen, C.; Alimehmeti, R.; Capone, C.; Barone, D.G.; Zdunczyk, A.; et al. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part I: Systematic Review of the Literature and Consensus on Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Classification of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome by the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies’ Section of Peripheral Nerve Surgery. Neurosurgery 2022, 90, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.; Fredricks, N.; Truong, N.; North, R.Y. Pediatric thoracic outlet syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2024, 33, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, K.; Miller, M.A.; Allgier, A.; Al Muhtaseb, T.; Little, K.J.; Schwentker, A.R. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome in the Pediatric and Young Adult Population. J Hand Surg Am 2024, 49, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, L.G.; Teich, S.; Hogan, M.; Caniano, D.A.; Smead, W. Pediatric thoracic outlet syndrome: a disorder with serious vascular complications. J Pediatr Surg 2008, 43, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, A.T.; Patel, P.A.; Elhadi, H.; Schwentker, A.R.; Yakuboff, K.P. Thoracic outlet syndrome in the pediatric population: case series. J Hand Surg Am 2014, 39, 484–487 e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maru, S.; Dosluoglu, H.; Dryjski, M.; Cherr, G.; Curl, G.R.; Harris, L.M. Thoracic outlet syndrome in children and young adults. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009, 38, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehemutula, A.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, D.; Gu, Y. Managing pediatric thoracic outlet syndrome. Ital J Pediatr 2015, 41, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, S.E.; Machleder, H.I. Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome using electrophysiologically guided anterior scalene blocks. Ann Vasc Surg 1998, 12, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, R.M.; Shah, K.N.; Rechnic, M.; Doehr, S.; Woods, N. Quantitative Assessment of Scalene Muscle Block for the Diagnosis of Suspected Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. J Hand Surg Am 2015, 40, 2255–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beason, A.M.; Thayer, J.A.; Arras, N.; Franke, J.D.; Mailey, B.A. Anterior Scalene Muscle Block Response Predicts Outcomes Following Thoracic Outlet Decompression. Hand (N Y) 2024, 19, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torriani, M.; Gupta, R.; Donahue, D.M. Sonographically guided anesthetic injection of anterior scalene muscle for investigation of neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Skeletal Radiol 2009, 38, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rached, R.; Hsing, W.; Rached, C. Evaluation of the efficacy of ropivacaine injection in the anterior and middle scalene muscles guided by ultrasonography in the treatment of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2019, 65, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, M.; Parnell, H. Scalenus anticus syndrome. The American Journal of Surgery 1947, 73, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).