Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Experimentation

2.2. Computed Tomography

2.2. Evaluation of Bone Structure

3. Results

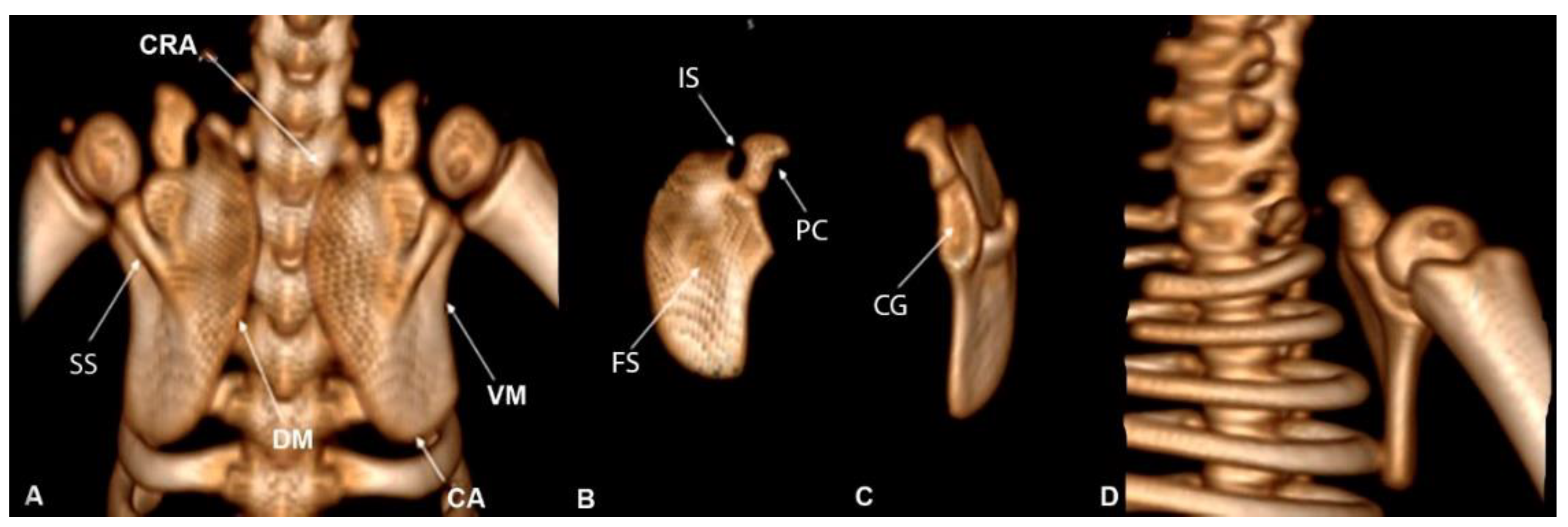

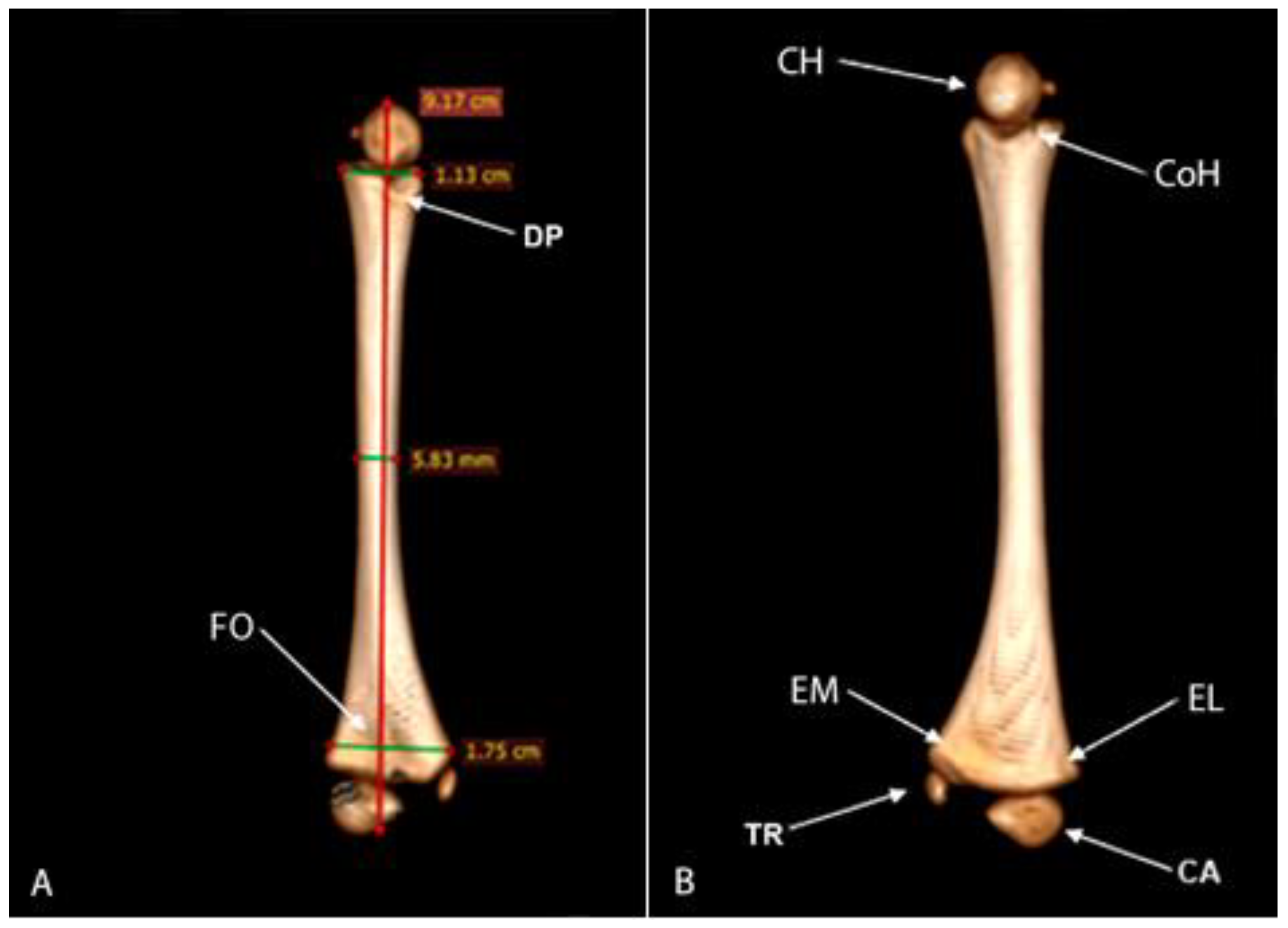

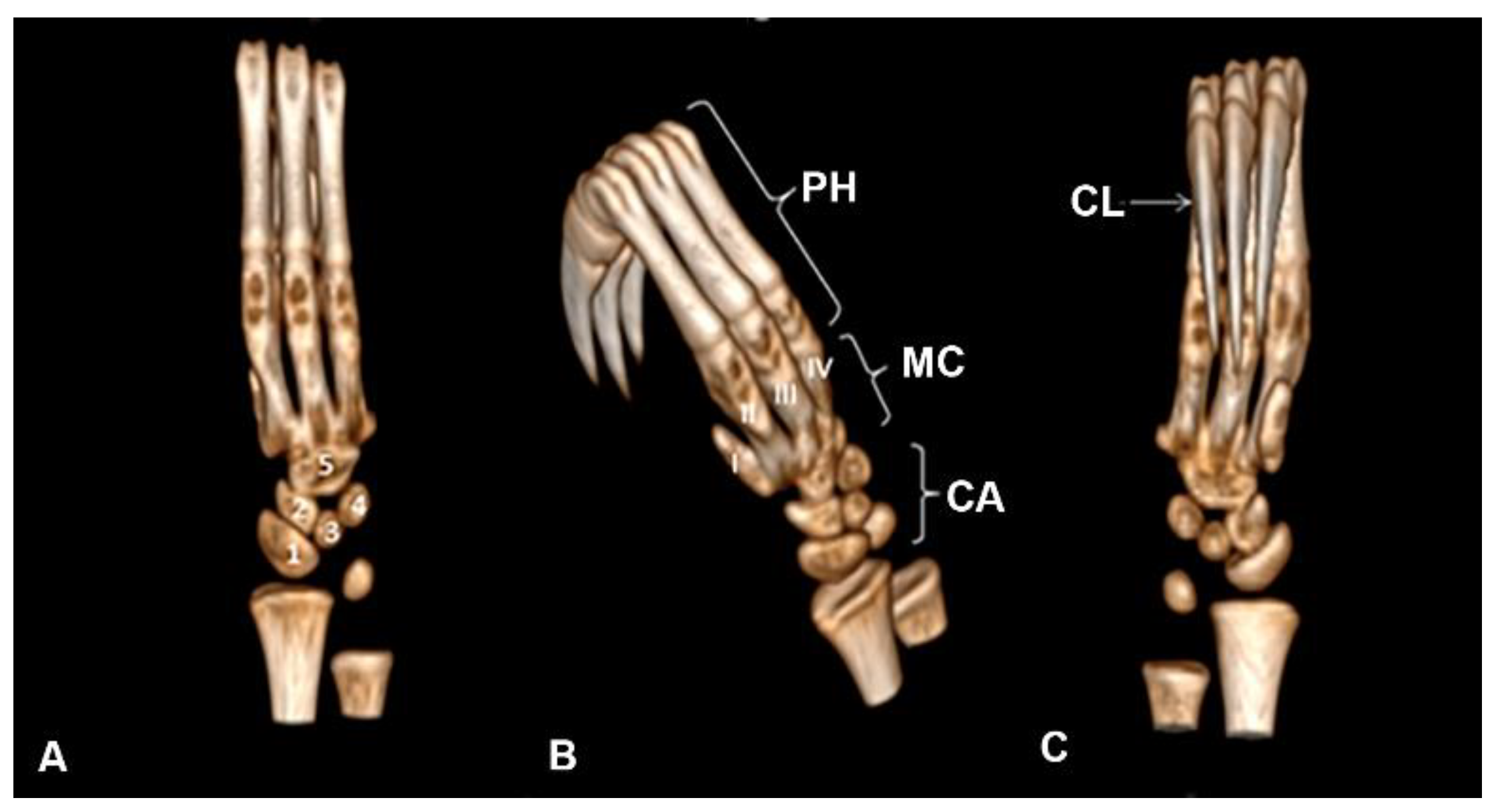

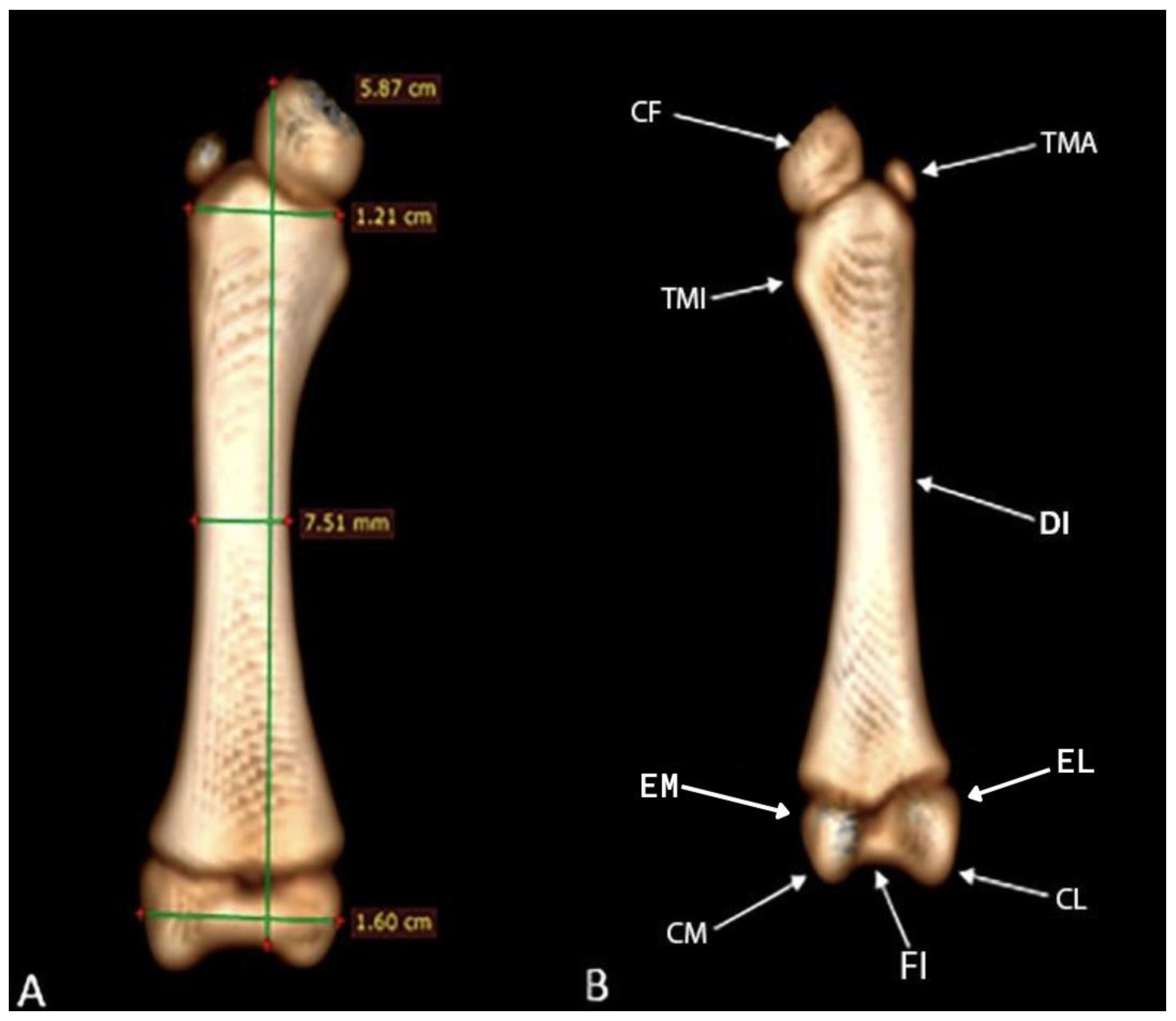

3.1. Forelimb

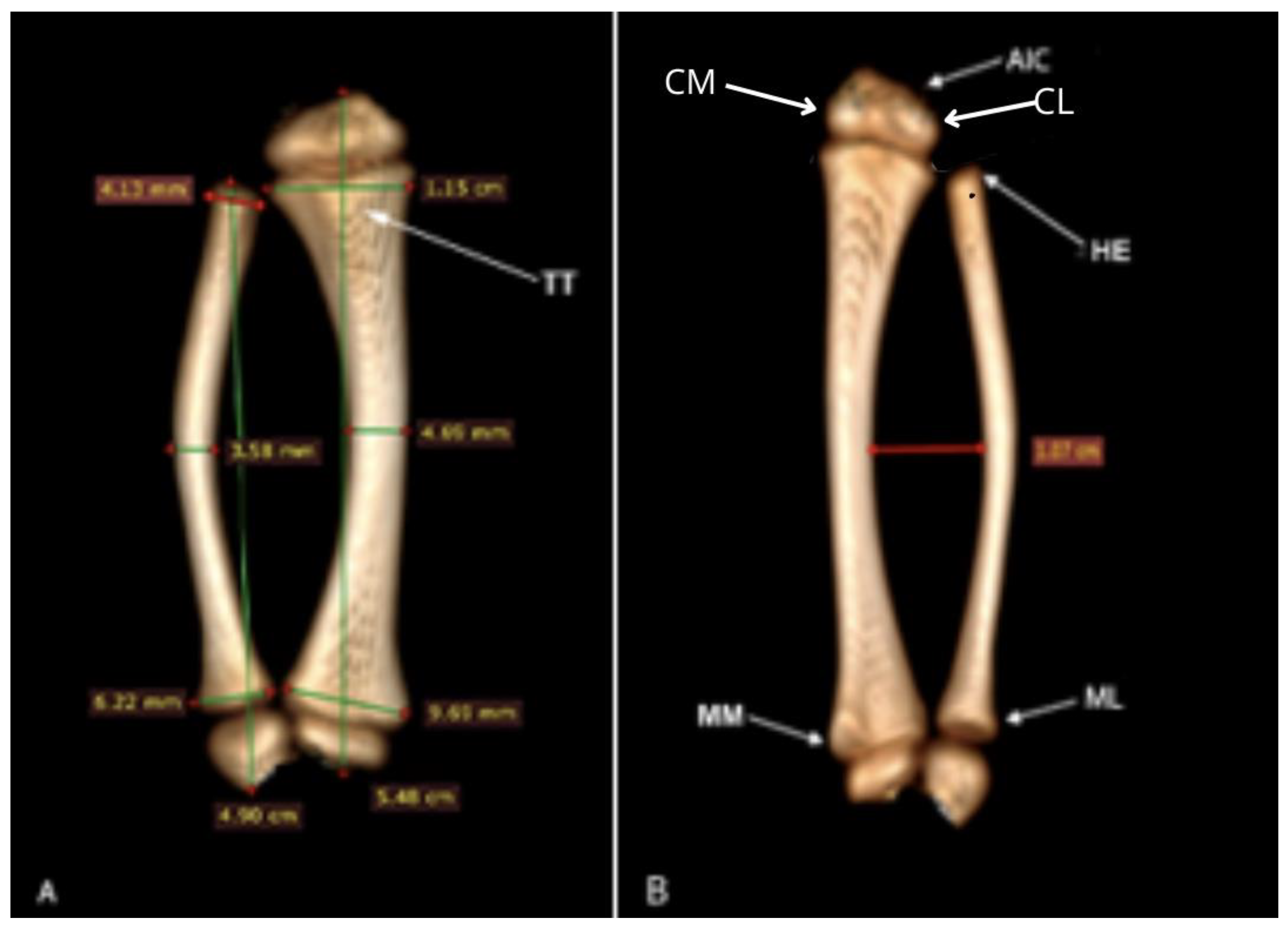

3.2. Pelvic Limb

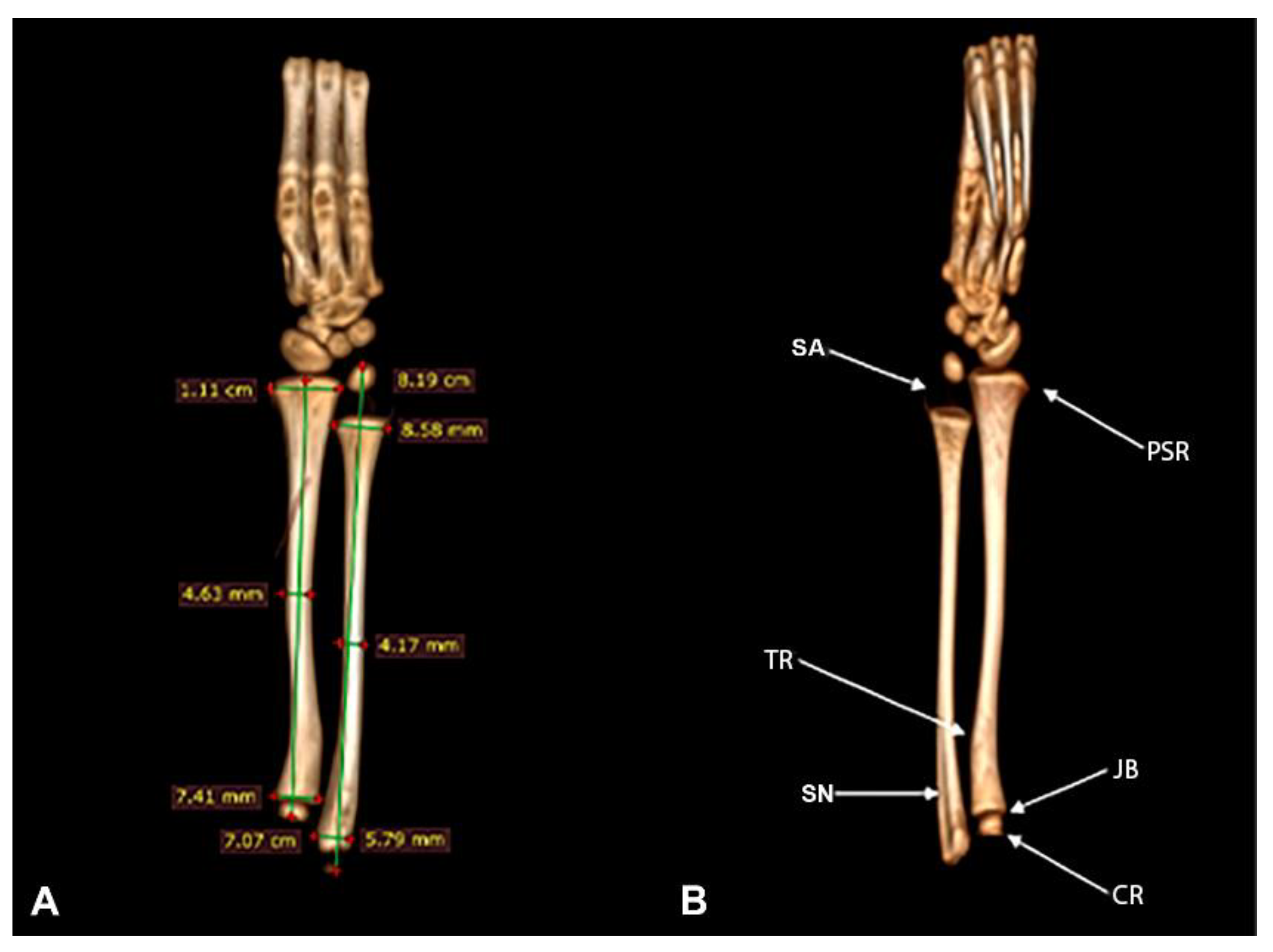

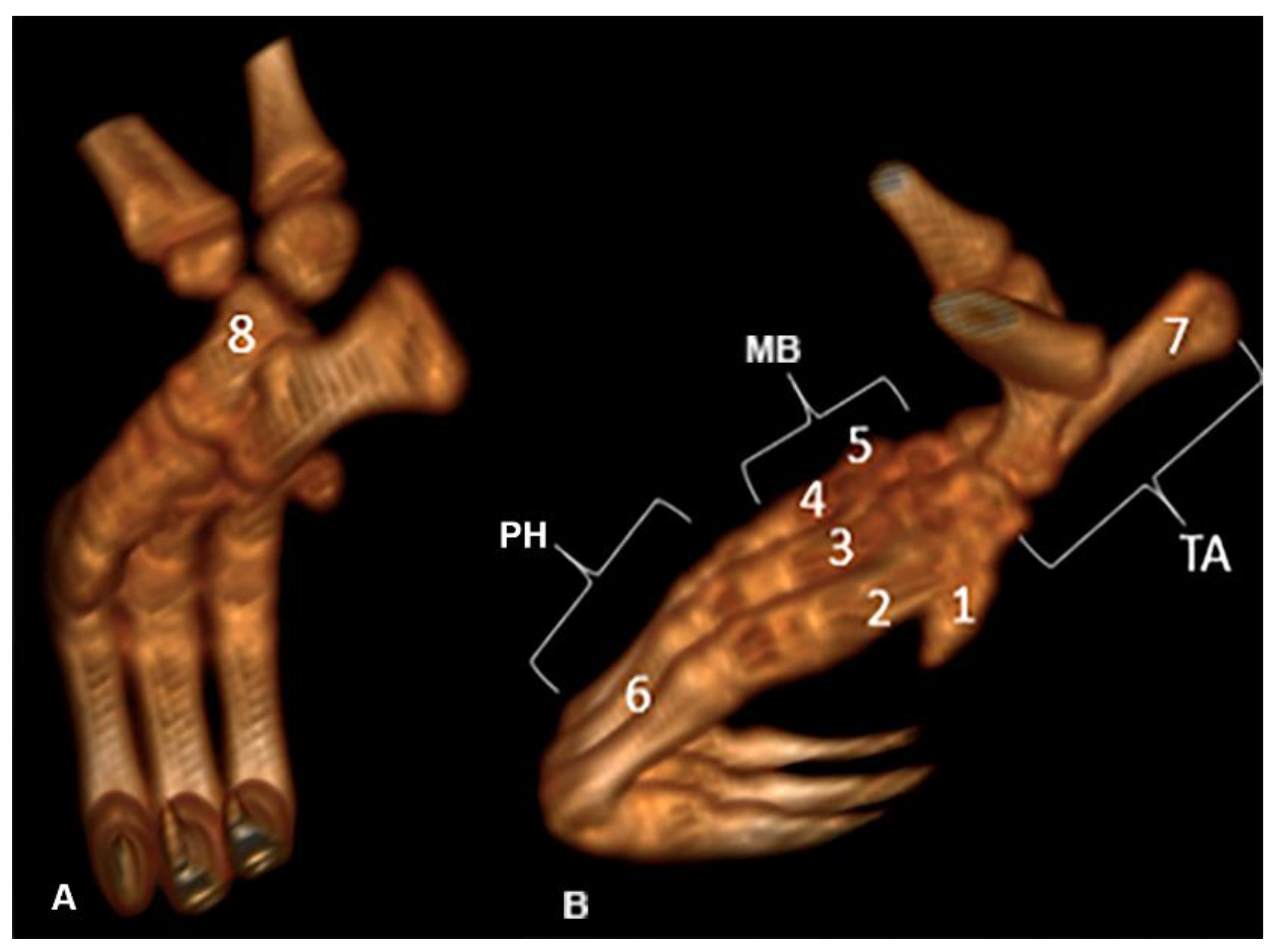

3.3. Extremities of the Pelvic Limb

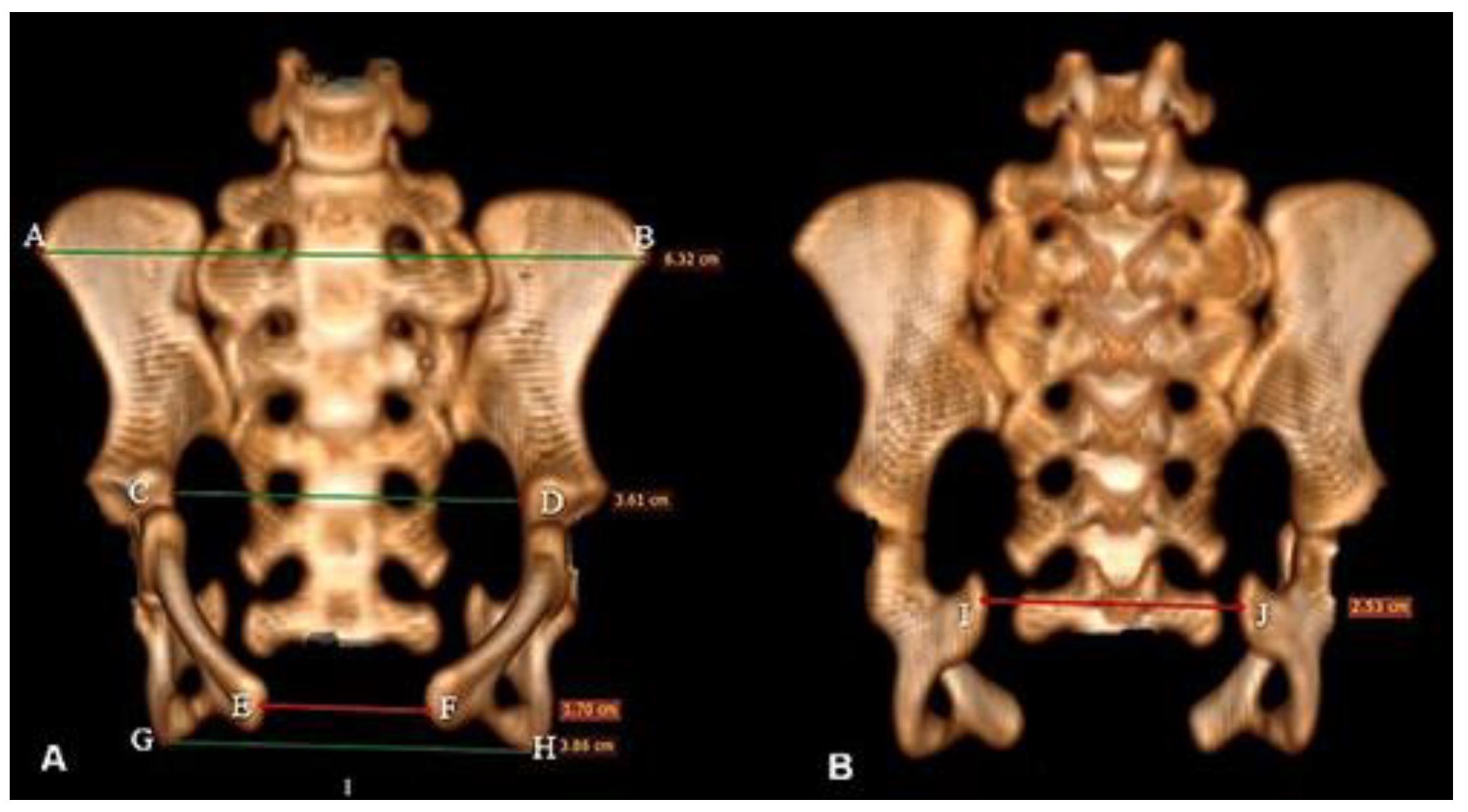

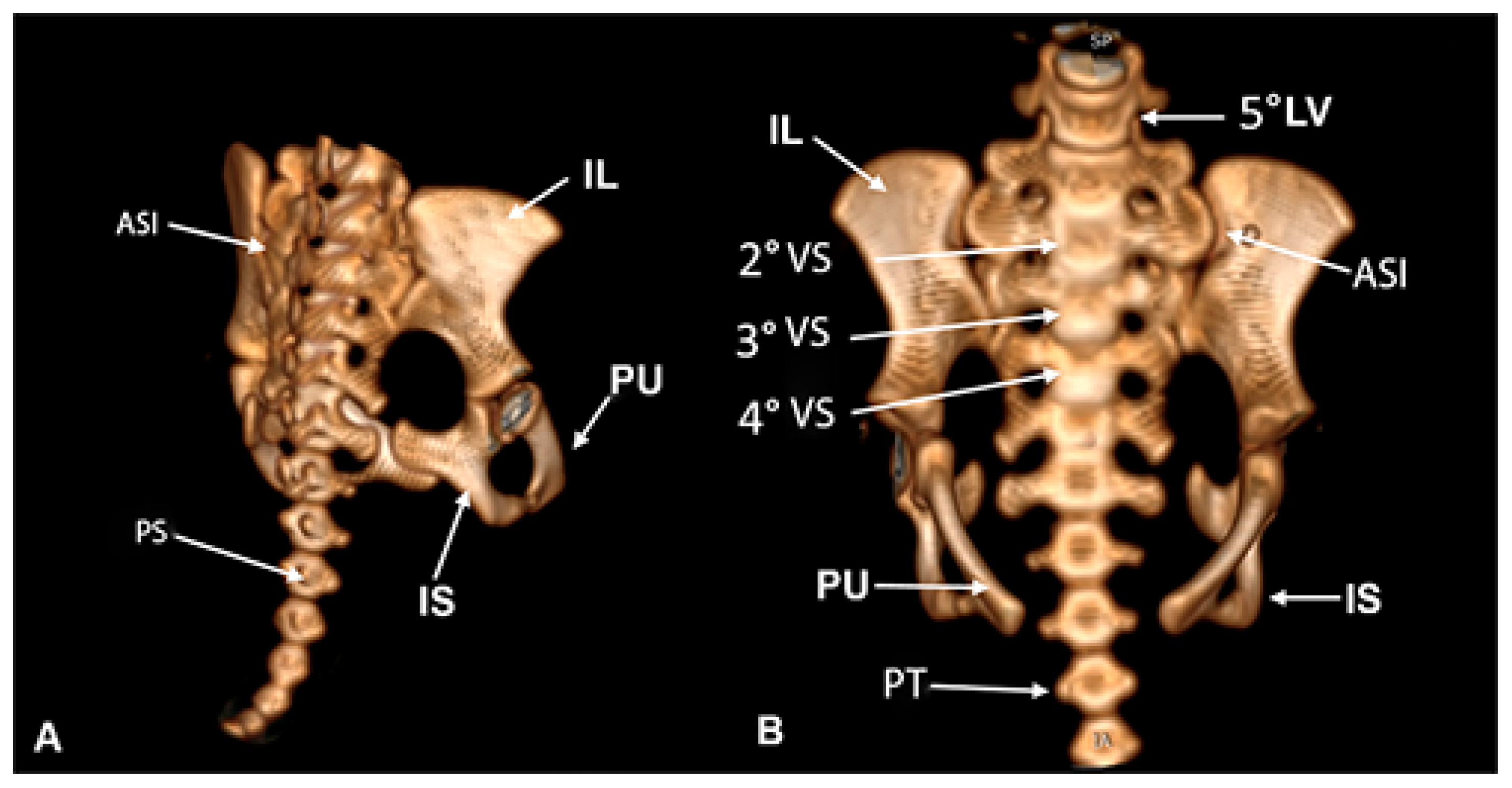

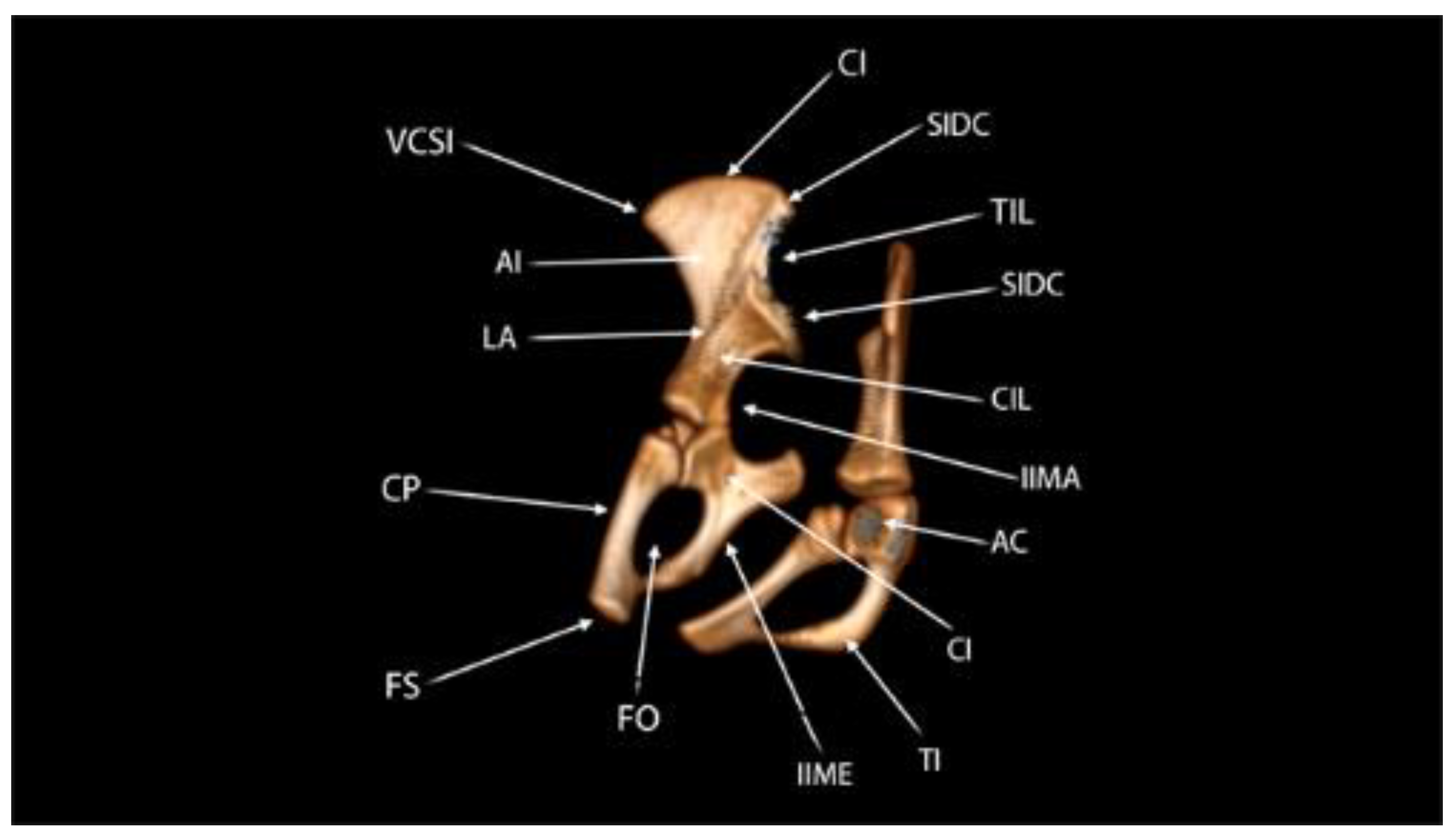

3.4. Pelvis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed tomography |

References

- Moraes-Barros, N.d.; Giorgi, A.P., Silva, S.; Morgante, J.S. Reevaluation of the Geographical Distribution of Bradypus tridactylus Linnaeus, 1758 and B. variegatus Schinz, 1825. Edentata, 2010, 11, 1, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Mendel, F.C. Use of hands and feet of three-toed sloths (Bradypus variegatus) during climbing and terrestrial locomotion. J. Mammal. 1985, 66, 2, 359–366.

- Granatosky, M.C.; Karantanis, N.E.; Rychlik, L.; Youlatos D. A suspensory way of life: Integrating locomotion, postures, limb movements, and forces in two-toed sloths Choloepus didactylus (Megalonychidae, Folivora, Pilosa). J. Exp. Zool. A. 2017, 329, 10, 570–588. [CrossRef]

- Young, M.W.; McKamy, A.J.; Dickinson, E.; Yarbro, J.; Ragupathi, A.; Guru, N.; Avey-Arroyo, J.A.; Butcher, M.T.; Granatosky, MC. Three toes and three modes: Dynamics of terrestrial, suspensory, and vertical locomotion in brown-throated three-toed sloths (Bradypodidae, Xenarthra). J. Exp. Zool. A. 2023, 339, 4, 383–397. [CrossRef]

- White, J.L. Indicators of locomotor habits in xenarthrans: Evidence for locomotor heterogeneity among fossil sloths, J Vertebr Paleontol 1993, 13, 2, 230–242. [CrossRef]

- Buckland, W. On the adaptation of the structure of the sloths to their peculiar mode of Life. Trans Linn Soc London 1834, 17, 1, 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.A. Functional Adaptations in the Forelimb of the Sloths. J. Mammal. 1935, 16, 1, 38–51. Accessed 25 Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mossor, A.M.; Young, J.W.; Butcher, M.T. Does a suspensory lifestyle result in increased tensile strength? Organ-level material properties of sloth limb bones. J Exp Biol. 2022, 225, 5, jeb242866. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.M.; Spainhower, K.B.; Mossor, A.M.; Avey-Arroyo, J.A.; Butcher, M.T. Muscle architectural properties indicate a primary role in support for the pelvic limb of three-toed sloths (Bradypus variegatus). J. Anat. 2023, joa13884. [CrossRef]

- Montañez-Rivera, I.; Nyakatura, J.A.; Amson, E. Bone cortical compactness in ‘tree sloths’ reflects convergent evolution. J. Anat., 2018, 233, 5, 580–591. [CrossRef]

- Butcher, M.T.; Morgan, D.M.; Spainhower, K.B.; Thomas, D.R.; Chadwell BA, Avey-Arroyo JA, Kennedy SP, Cliffe RN. Myology of the pelvic limb of the brown-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus). J. Anat. (2022) 240(6):1048-1074. [CrossRef]

- Zehtabvar, O.; Masoudifard, M.; Rostami, A.; Akbarein, H.; Sereshke, A.H.A.; Khanamooeiashi, M.; Borgheie, F. CT anatomy of the lungs, bronchi, and trachea in the mature Guinea pig (cavia porcellus). Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 3, 1179–1193. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M. S.; Albuquerque, R. dos S.; Campos, J.G.M.; Monteiro, F.D.O.; Rossy, K.C.; Cardoso, T. da S.; Carvalho, L.S.; Borges, L.P.B.; Domingues, S.F.S.; Thiesen, R.; Thiesen, R.M.C.; Teixeira, P. P.M. Computed Tomography Evaluation of Frozen or Glycerinated Bradypus variegatus Cadavers: A Comprehensive View with Emphasis on Anatomical Aspects. Animals. 2024, 14, 3, 355. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, J.R.J.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Arencibia, A.; Déniz, S.; Carrascosa, C.; Encinoso, M. Anatomical Description of Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta) and Green Iguana (Iguana iguana) Skull by Three-Dimensional Computed Tomography Reconstruction and Maximum Intensity Projection Images. Animals. 2023, 13, 4, 621. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.M.A.M.; Bete, S.B.S.; Inamassu, L.R.; Mamprim, M.J.; Schimming, B.C. Anatomy of the skull in the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) using radiography and 3D computed tomography. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2020, 49, 3, 317–324. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Clarke, J.A. The Craniolingual Morphology of Waterfowl (Aves, Anseriformes) and Its Relationship with Feeding Mode Revealed Through Contrast-Enhanced X-Ray Computed Tomography and 2D Morphometrics. Evol. Biol. 2016, 43, 12–25. [CrossRef]

- Grand, T.I. Adaptations of tissue and limb to facilitate moving and feeding in arboreal folivores. In: Montgomery GG (ed) The Ecology of Arboreal Folivores. Smithsonian Institution Press 1978, Washington, D. C., pp 231–241.

- Amson, E.; Nyakatura, J.A. The postcranial musculoskeletal system of xenarthrans: insights from over two centuries of research and future directions. J. Mamm. Evol. 2018, 25, 459–484. [CrossRef]

- Spear, J.K.; Williams, S.A. Mosaic patterns of homoplasy accompany the parallel evolution of suspensory adaptations in the forelimb of tree sloths (Folivora: Xenarthra). Zool J Linne Soc 2020, 193, 2, 445–463. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Encinoso, M.; Corbera, J.A.; Morales, M.; Arencibia, A.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Déniz, S.; Melián, C.; Suárez-Bonnet, A.; Jaber, J.R. Cranial Structure of Varanus komodoensis as Revealed by Computed-Tomographic Imaging. Animals 2021, 11, 1078. [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.J., Bouman, C., Carmignato, S. et al. X-ray computed tomography. Nat Rev Methods Primers 1, 18 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Castro-Vásquez, L.; Meza, M; Plese, T; Moreno-Mora, S. Activity patterns, preference and use of floristic resources by Bradypus variegatus in a tropical dry forest fragment, Santa Catalina, Bolívar, Colombia. Edentata. 2010, 11, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- International Committee on veterinary gross anatomical nomenclature. Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria. 6th ed. Hannover, Ghent, Columbia, Rio de Janeiro: Editorial Committee, 2017. 178p.

- Eneroth, A.; Linde-Forsberg, C; Uhlhorn, M; Hall, M. Radiographic pelvimetry for assessment of dystocia in bitches: a clinical study in two terrier breeds. J Small Anim Pract. 1999, 40, 6, 257–264. [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, D.P.; Costa, C.P.; Duarte, D.P.F. Sloth biology: an update on their physiological ecology, behavior and role as vectors of arthropods and arboviruses. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2001, 34, 1, 9–25. [CrossRef]

- Presslee, S.; Slater, G.J.; Pujos, F. et al. Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships. Nat Ecol Evol 2019, 3, 1121–1130. [CrossRef]

- Püschel, T.A.; Sellers, W.I. Standing on the shoulders of apes: Analyzing the form and function of the hominoid scapula using geometric morphometrics and finite element analysis. Am J Biol Anthropol. 2016, 159, 2, 325–341. [CrossRef]

- Nyakatura, J.A.; Stark, H. Aberrant back muscle function correlates with the intramuscular architecture of the dorsovertebral muscles in two-toed sloths. Mamm. Biol. 2015, 80, 2, 114–121. [CrossRef]

- Gebo, D.L. Climbing, brachiation, and terrestrial quadrupedalism: Historical precursors of hominid bipedalism. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1996, 101, 1, 55–92. [CrossRef]

- Myatt, J.P.; Crompton, R.H.; Payne-Davis, R.C.; Vereecke, E.E.; Isler, K.; Savage, R.; D’Août, K.; Günther, M.M.; Thorpe, S.K.S. Functional adaptations in the forelimb muscles of non-human great apes. J Anat 2012, 220, 1, 13–28. [CrossRef]

- Ruff, C.B.; Junno, J-A.; Burgess, M.L.; Canington, S.L.; Harper, C.; Mudakikwa, A.; McFarlin, S.C. Body proportions and environmental adaptation in gorillas. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2022, 177, 3, 501–529. [CrossRef]

- Grass, A.D. Inferring differential behavior between giant ground sloth adults and juveniles through scapula morphology. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2019, 39, 1. [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, T.J. Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2004, 140, 255–305. [CrossRef]

- Delsuc, F.; Kuch, M.; Gibb, G.C.; Karpinski, E.; Hackenberger, D.; Szpak, P.; Martínez, J.G.; Mead, J.I.; McDonald, H.G.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Billet, G.; Hautier, L.; Poinar, H.N. Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths. Curr Biol. 2019, 29, 12, 2031–2042. [CrossRef]

- Casali, D.M.; Boscaini, A.; Gaudin, T.J.; Perini, F.A. Reassessing the phylogeny and divergence times of sloths (Mammalia: Pilosa: Folivora), exploring alternative morphological partitioning and dating models. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2022, 196, 4, 1505–1551. [CrossRef]

- Butcher, M.T.; Morgan, D.M.; Spainhower, K.B.; Thomas, D.R.; Chadwell, B.A.; Avey-Arroyo, J.A.; Kennedy, S.P.; Cliffe, R.N. Myology of the pelvic limb of the brown-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus). J. Anat. 2022, 240, 6, 1048–1074. [CrossRef]

- Hautier, L.; Weisbecker, V.; Sánchez-Villagra, M.R.; Goswami, A; Asher, R.J. Skeletal development in sloths and the evolution of mammalian vertebral patterning. Biol. 2010, 107, 44, 18903–18908. [CrossRef]

- Kaup, M.; Trull, S.; Hom, E.F.Y. On the move: sloths and their epibionts as model mobile ecosystems. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 6, 2638–2660. [CrossRef]

- Nyakatura, J.A.; Fischer, M.S. Functional morphology and three-dimensional kinematics of the thoraco-lumbar region of the spine of the two-toed sloth. J Exp Biol. 2010, 213, 4278–4290. [CrossRef]

- Hautier, L.; Weisbecker, V.; Goswami, A.; Knight, F.; Kardjilov, N.; Asher, R.J. Skeletal ossification and sequence heterochrony in xenarthran evolution. Evol. Dev. 2011, 13, 5, 460–476. [CrossRef]

- Borges, N.C.; Nardotto, J.R.B.; Oliveira, R.S.L.; Rüncos, L.H.E.; Ribeiro, R.G.; Bogoevich, A.M. Anatomy description of cervical region and hyoid apparatus in living giant anteaters Myrmecophaga tridactyla Linnaeus, 1758. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2017, 37, 11, 1345–1351. [CrossRef]

- Gavazzi, L.M.; Kjosness, K.M.; Reno, P.L. Ossification pattern of the unusual pisiform in two-toed (Choloepus) and three-toed sloths (Bradypus). Anat. Rec. 2021, 305, 7, 1804–1819. [CrossRef]

- Werning, S. Osteohistological differences between marsupials and placental mammals reflect both growth rates and life history strategies. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2013, 53, E224.

- Olson, R.A.; Glenn, Z.D; Cliffe, R.N; Butcher, M.T. Architectural Properties of Sloth Forelimb Muscles (Pilosa: Bradypodidae). J. Mamm. Evol. 2018, 25, 573–588. [CrossRef]

- Spainhower, K.B.; Metz, A.K.; Yusuf, A.R.S.; Johnson, L.E.; Avey-Arroyo, J.A.; Butcher, M.T. Coming to grips with life upside down: How the type of myosin fibre and metabolic properties of sloth hindlimb muscles contribute to suspensory function. J Comp Physiol. 2021, 191, 207–224. [CrossRef]

- Montilla-Rodrigues, M.A.; Blanco-Rodriguez, J.C.; Nastar-Ceballos R.N.; Munoz-Martinez, L.J. Descripción Anatómica de Bradypus variegatus em la Amazonia Colombiana (Estudio Preliminar). Rev Fac Cienc Vet. 2016, 57, 3–14.

- Borges, N.C.; Cruz, V.S.; Fares, N.B.; Cardoso, J.R..; Bragato, N. Morphological evaluation of the thoracic, lumbar and sacral column of the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla Linnaeus, 1758). Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2017, 37, 4, 401–407. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.R.; Souza, P.R., Cruz, V.S.; Benetti, E.J.; Silva M.S.B., Moreira P.C.; Cardoso, A.A.L.; Martins, A.K.; Abreu, T.; Simões, K.; Guimarães, F.R. Anatomical study of the lumbosacral plexus of the Tamandua tetradactyla. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2013, 65, 1720–1728. [CrossRef]

- Granatosky, M.C.; Karantanis, N.E.; Rychlik L.; Youlatos, D. A suspensory way of life: Integrating locomotion, postures, limb movements, and forces in two-toed sloths Choloepus didactylus (Megalonychidae, Folivora, Pilosa). J. Exp. Zool. A 2017, 329, 10, 570–588. [CrossRef]

- Gorvet, M.A.; Wakeling, J.M.; Morgan, D.M.; Segura, D.H.; Avey-Arroyo, J.; Butcher, M.T. Keep calm and hang on: EMG activation in the forelimb musculature of three-toed sloths (Bradypus variegatus). J Exp Biol, 2020, 223, 14, jeb218370. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).