Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

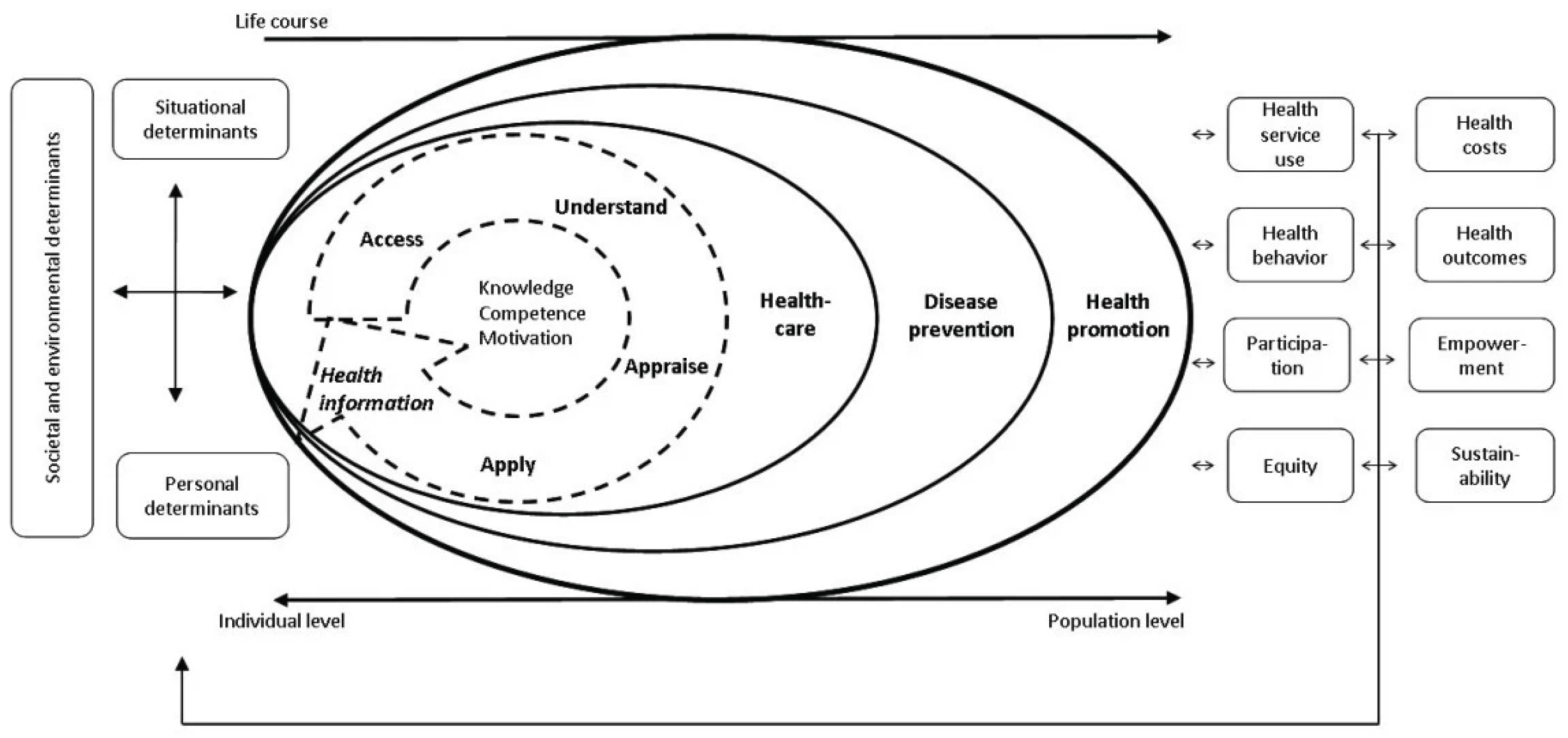

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Aim

2.3. Definitions and Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. RHL and Knowledge: Measurement Methods

3.2.1. RHL

3.2.2. Cervical Cancer and Screening

3.2.3. Contraception and Family Planning

3.2.4. HIV

3.2.5. Maternal Health and Pregnancy

3.2.6. Other Domains

3.3. RHL and Knowledge: Relation to Behavior, Decision-Making, and Outcomes

3.3.1. Cervical Cancer and Screening

3.3.2. Contraception and Family Planning

3.3.3. HIV

3.3.4. Maternal Health and Pregnancy

3.3.5. Other Domains

4. Discussion

4.1. Measurement of RHL and Knowledge

4.2. RH Knowledge’s Influence on Decision-Making, Behavior, and Outcomes

4.3. Promoting RHL and Knowledge

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCP | Health care provider |

| LMIC | low-or middle-income country |

| RH | Reproductive health |

| RHL | Reproductive health literacy |

| SRH | Sexual and reproductive health |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Section | Item | PRISMA-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 1-3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| Methods | 3 | ||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 3 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 3 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 3 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 3-4 |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 4 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 4 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 5, Table 1, Table 2 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | NA |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 4 |

| Results | |||

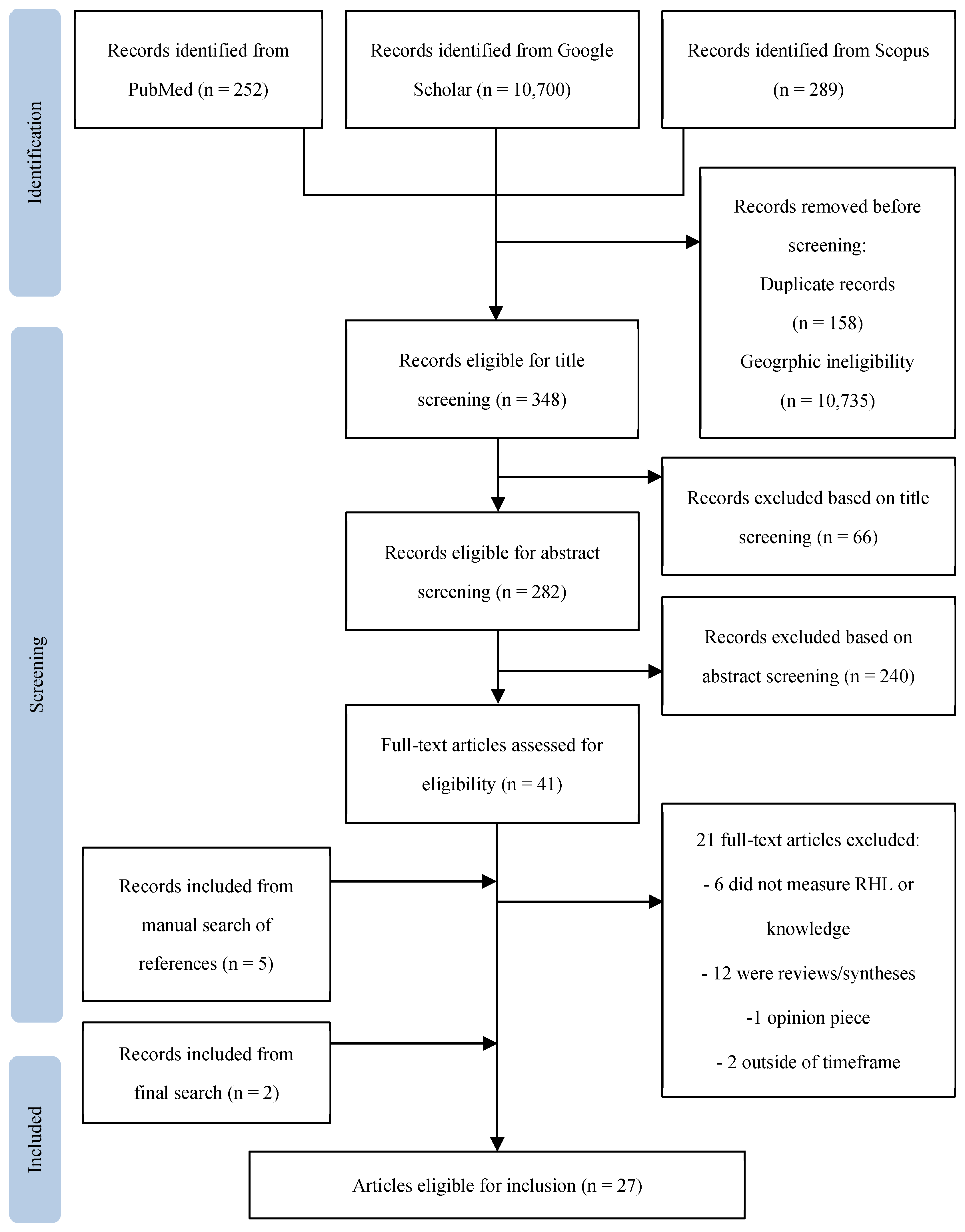

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 8 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | Table 1, Table 2 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | NA |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Table 1, Table 2 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 9-12 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 12-15 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 15 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 15-16 |

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 18 |

References

- Sørensen, K.; Van Den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N. D.; Sheridan, S. L.; Donahue, K. E.; Halpern, D. J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corneliess, C.; Gray, K.; Kidwell Drake, J.; Namagembe, A.; Stout, A.; Cover, J. Education as an Enabler, Not a Requirement: Ensuring Access to Self-Care Options for All. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 2022, 29, 2040776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghavami, B.; Sohrabi, Z.; RaisiDehkordi, Z.; Mohammadi, F. Relationship between Reproductive Health Literacy and Components of Healthy Fertility in Women of the Reproductive Age. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongarwar, D.; Salihu, H. M. Influence of Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy on Single and Recurrent Adolescent Pregnancy in Latin America. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2019, 32, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrampour, B.; Shahali, S.; Lamyian, M.; Rasekhi, A. Sexual Health Literacy among Rural Women in Southern Iran. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 17377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wagner, C.; Steptoe, A.; Wolf, M. S.; Wardle, J. Health Literacy and Health Actions: A Review and a Framework From Health Psychology. Health Educ Behav 2009, 36, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D. A.; Bess, K. D.; Tucker, H. A.; Boyd, D. L.; Tuchman, A. M.; Wallston, K. A. Public Health Literacy Defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2009, 36, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomair, N.; Alageel, S.; Davies, N.; Bailey, J. V. Factors Influencing Sexual and Reproductive Health of Muslim Women: A Systematic Review. Reprod Health 2020, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K. S.; Castaño, P. M.; Westhoff, C. L. The Influence of Oral Contraceptive Knowledge on Oral Contraceptive Continuation Among Young Women. Journal of Women’s Health 2014, 23, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilfoyle, K. A.; Vitko, M.; O’Conor, R.; Bailey, S. C. Health Literacy and Women’s Reproductive Health: A Systematic Review. Journal of Women’s Health 2016, 25, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewski, D.; Aronson, B. D.; Kading, M.; Morisky, D. Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Patient Knowledge on Adherence to Oral Contraceptives Using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). Reprod Health 2017, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M. D.; Popper, S. T.; Rodwell, T. C.; Brodine, S. K.; Brouwer, K. C. Healthcare Barriers of Refugees Post-Resettlement. J Community Health 2009, 34, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, D. M.; Harrison, C. L. Refugee Women’s Reproductive Health in Early Resettlement. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 2004, 33, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Helm, M. E.; Teede, H. J.; Cheng, I.; Block, A. A.; Knight, M.; East, C. E.; Wallace, E. M.; Boyle, J. A. Maternal Health and Pregnancy Outcomes Comparing Migrant Women Born in Humanitarian and Nonhumanitarian Source Countries: A Retrospective, Observational Study. Birth 2015, 42, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturrock, S.; Williams, E.; Greenough, A. Antenatal and Perinatal Outcomes of Refugees in High Income Countries. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 2021, 49, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2023.

- Davidson, N.; Hammarberg, K.; Romero, L.; Fisher, J. Access to Preventive Sexual and Reproductive Health Care for Women from Refugee-like Backgrounds: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; Akl, E. A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M. G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S.; Godfrey, C. M.; Macdonald, M. T.; Langlois, E. V.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Moriarty, J.; Clifford, T.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A. C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C. M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M.; Goliaei, Z.; Machta, L.; Chang, J.; Thiel De Bocanegra, H. Reproductive Health Literacy Scale: A Tool to Measure the Effectiveness of Health Literacy Training. Reprod Health 2025, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reproductive Health Indicators: Guidelines for Their Generation, Interpretation and Analysis for Global Monitoring; World Health Organization, 2006. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43185/924156315X_eng.pdf.

- Anaman, J. A.; Correa-Velez, I.; King, J. A Survey of Cervical Screening among Refugee and Non-refugee African Immigrant Women in Brisbane, Australia. Health Prom J of Aust 2017, 28, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaman, J. A.; Correa-Velez, I.; King, J. Knowledge Adequacy on Cervical Cancer Among African Refugee and Non-Refugee Women in Brisbane, Australia. J Canc Educ 2018, 33, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla, V.; Panagiotopoulou, E.-K.; Deltsidou, A.; Kalogeropoulou, M.; Kostagiolas, P.; Niakas, D.; Labiris, G. Level of Awareness Regarding Cervical Cancer Among Female Syrian Refugees in Greece. J Canc Educ 2022, 37, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haworth, R. J.; Margalit, R.; Ross, C.; Nepal, T.; Soliman, A. S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices for Cervical Cancer Screening Among the Bhutanese Refugee Community in Omaha, Nebraska. J Community Health 2014, 39, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, I. J.; Ho, K.; Jackson, J. C.; Moo-Young, J.; Le, A.; Do, H. H.; Lor, B.; Magarati, M.; Zhang, Y.; Taylor, V. M. Results From a Pilot Video Intervention to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening in Refugee Women. Health Educ Behav 2018, 45, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E. M.; Lee, H. Y.; Pratt, R.; Vang, H.; Desai, J. R.; Dube, A.; Lightfoot, E. Facilitators and Barriers of Cervical Cancer Screening and Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination Among Somali Refugee Women in the United States: A Qualitative Analysis. J Transcult Nurs 2019, 30, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lor, B.; Ornelas, I. J.; Magarati, M.; Do, H. H.; Zhang, Y.; Jackson, J. C.; Taylor, V. M. We Should Know Ourselves: Burmese and Bhutanese Refugee Women’s Perspectives on Cervical Cancer Screening. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 2018, 29, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metusela, C.; Ussher, J.; Perz, J.; Hawkey, A.; Morrow, M.; Narchal, R.; Estoesta, J.; Monteiro, M. “In My Culture, We Don’t Know Anything About That”: Sexual and Reproductive Health of Migrant and Refugee Women. Int.J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaman-Torgbor, J. A.; King, J.; Correa-Velez, I. Barriers and Facilitators of Cervical Cancer Screening Practices among African Immigrant Women Living in Brisbane, Australia. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2017, 31, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbemenu, K.; Volpe, E. M.; Dyer, E. Reproductive Health Decision-making among US -dwelling Somali Bantu Refugee Women: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2018, 27, 3355–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, P. A.; Olson, L. M.; Jackson, B.; Weber, L. S.; Gawron, L.; Sanders, J. N.; Turok, D. K. Family Planning Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Somali and Congolese Refugee Women After Resettlement to the United States. Qual Health Res 2020, 30, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; McCoy, E. E.; Scego, R.; Phillips, W.; Godfrey, E. A Qualitative Exploration of Somali Refugee Women’s Experiences with Family Planning in the U.S. J Immigrant Minority Health 2020, 22, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gele, A. A.; Musse, F. K.; Shrestha, M.; Qureshi, S. Barriers and Facilitators to Contraceptive Use among Somali Immigrant Women in Oslo: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru Alici, N.; Ogüncer, A. Knowledge, Beliefs, and Cultural Practices of Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Afghan Refugee Women in Türkiye. J Transcult Nurs 2024, 35, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngum Chi Watts, M. C.; Liamputtong, P.; Carolan, M. Contraception Knowledge and Attitudes: Truths and Myths among African Australian Teenage Mothers in Greater Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngum Chi Watts, M. C.; McMichael, C.; Liamputtong, P. Factors Influencing Contraception Awareness and Use: The Experiences of Young African Australian Mothers. Journal of Refugee Studies 2015, 28, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, C. P.; Kaflay, D.; Dowshen, N.; Miller, V. A.; Ginsburg, K. R.; Barg, F. K.; Yun, K. Attitudes and Beliefs Pertaining to Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Unmarried, Female Bhutanese Refugee Youth in Philadelphia. Journal of Adolescent Health 2017, 61, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneoka, M.; Spence, W. The Cultural Context of Sexual and Reproductive Health Support: An Exploration of Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy among Female Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Glasgow. IJMHSC 2019, 16, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier-Raman, S.; Hossain, S. Z.; Mpofu, E.; Lee, M.-J.; Liamputtong, P.; Dune, T. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Decision-Making among Australian Migrant and Refugee Youth: A Group Concept Mapping Study. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2024, 26, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.; Mitchell, M.; Stewart, D.; Debattista, J. Sexual Health Knowledge and Behaviour of Young Sudanese Queenslanders: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sex. Health 2017, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier-Raman, S.; Bidewell, J.; Hossain, S. Z.; Mpofu, E.; Lee, M.-J.; Liamputtong, P.; Dune, T. Migrant and Refugee Youth’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: A Gender Comparison of Knowledge, Behaviour, and Experiences. Sexuality & Culture 2025, 29, 734–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inci, M. G.; Kutschke, N.; Nasser, S.; Alavi, S.; Abels, I.; Kurmeyer, C.; Sehouli, J. Unmet Family Planning Needs among Female Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Germany – Is Free Access to Family Planning Services Enough? Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Reprod Health 2020, 17, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feresu, S.; Smith, L. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs about HIV/AIDS of Sudanese and Bantu Somali Immigrant Women Living in Omaha, Nebraska. OJPM 2013, 03, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbemenu, K.; Aidoo-Frimpong, G.; Auerbach, S.; Jafri, A. HIV Attitudes and Beliefs in U.S.-Based African Refugee Women. Ethnicity & Health 2022, 27, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.; Beruf, C.; Fischer, T. Access to Health Care for Pregnant Arabic-Speaking Refugee Women and Mothers in Germany. Qual Health Res 2020, 30, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A. D.; Rangen, C. M.; Avery, M. D. Design and Implementation of a Group Prenatal Care Model for Somali Women at a Low-Resource Health Clinic. Nursing for Women’s Health 2019, 23, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier-Raman, S.; Hossain, S. Z.; Mpofu, E.; Lee, M.-J.; Liamputtong, P.; Dune, T. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Decision-Making among Australian Migrant and Refugee Youth: A Group Concept Mapping Study. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2024, 26, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussaini, N. W. Z.; Elshaikh, U.; Abdulrashid, K.; Elashie, S.; Hamad, N. A.; Al-Jayyousi, G. F. Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy of Higher Education Students: A Scoping Review of Determinants, Screening Tools, and Effective Interventions. Global Health Action 2025, 18, 2480417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Jiang, H.; Shi, H. Development and Validation of the Reproductive Health Literacy Questionnaire for Chinese Unmarried Youth. Reprod Health 2021, 18, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasoumi, R.; Tavousi, M.; Zarei, F. Development and Psychometric Properties of Sexual Health Literacy for Adults (SHELA) Questionnaire. Hayat, Journal of School of Nursing and Midwifery 25, 56–59.

- Panahi, R.; Dehghankar, L.; Amjadian, M. Investigating the Structural Validity and Reliability of the Sexual Health Literacy for Adults (SHELA) Questionnaire among a Sample of Women in Qazvin, Iran. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, K.; Watson, P.; Farahani, H.; Chesli, R. R.; Abiri, F. A. Developing and Validating the Sexual Health Literacy Scale in an Iranian Adult Sample. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2023, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongxay, V.; Thongmixay, S.; Stoltenborg, L.; Inthapanyo, A.; Sychareun, V.; Chaleunvong, K.; Rombout Essink, D. Validation of the Questionnaire on Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy for Adolescents Age 15 to 19 Years in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. [CrossRef]

- Bitterfeld, L.; Ozkaynak, M.; Denton, A. H.; Normeshie, C. A.; Valdez, R. S.; Sharif, N.; Caldwell, P. A.; Hauck, F. R. Interventions to Improve Health Among Refugees in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Community Health 2025, 50, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanu, A.; Birhanu, Z.; Godesso, A. Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy among Young People in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence Synthesis and Implications. Global Health Action 2023, 16, 2279841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, A.; Betancourt, T.; Kergoat, Y.; Servilli, C.; Say, L.; Kobeissi, L. A Systematic Review of Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions for Young People in Humanitarian and Lower-and-Middle-Income Country Settings. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeiro, R. E.; De Siqueira Guida, J. P.; da-Costa-Santos, J.; Costa, M. L. Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) Needs for Forcibly Displaced Adolescent Girls and Young Women (10–24 Years Old) in Humanitarian Settings: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Reprod Health 2023, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandagiri, R. What’s so Troubling about ‘Voluntary’ Family Planning Anyway? A Feminist Perspective. Population Studies 2021, 75, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderowicz, L.; Valley, T. Fertility Has Been Framed: Why Family Planning Is Not a Silver Bullet for Sustainable Development. St Comp Int Dev 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.; George, A. S.; Jacobs, T.; Blanchet, K.; Singh, N. S. A Forgotten Group during Humanitarian Crises: A Systematic Review of Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions for Young People Including Adolescents in Humanitarian Settings. Confl Health 2019, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haj-Mohamad, R.; Nohr, L.; Niemeyer, H.; Böttche, M.; Knaevelsrud, C. Smartphone-Delivered Mental Health Care Interventions for Refugees: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Camb. prisms Glob. ment. health 2023, 10, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C. L.; Surmeli, A.; Hoeflin Hana, C.; Narla, N. P. Perceptions on a Mobile Health Intervention to Improve Maternal Child Health for Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Opportunities and Challenges for End-User Acceptability. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1025675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez Corona, M.; Hazfiarini, A.; Vaughan, C.; Block, K.; Bohren, M. A. Participatory Health Research With Women From Refugee, Asylum-Seeker, and Migrant Backgrounds Living in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2024, 23, 16094069231225371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Author | Year | Country | Population (n) | Design | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agbemenu et al. | 2018 | U.S.A. | Somali Bantu refugee women (30) | Qualitative | Accurate and high levels of knowledge on birth control options did not increase contraceptive uptake. |

| 2 | Agbemenu et al. | 2022 | U.S.A. | African refugee women (101) | Quantitative | Study population had overall low levels of knowledge. Accurate knowledge did not override stigma. |

| 3 | Allen et al. | 2018 | U.S.A. | Somali Bantu refugee women with >1 child (31) | Qualitative | Low knowledge about HPV was associated with low HPV vaccination rates. |

| 4 | Anaman et al. | 2017 | Australia | African refugee (144) and non-refugee (110) women | Quantitative | Low health literacy and low levels of knowledge regarding cervical cancer and screening were associated with low Pap smear uptake. |

| 5 | Anaman et al. | 2018 | Australia | African refugee (144) and non-refugee (110) women | Quantitative | Refugees in the study population had significantly lower levels of knowledge about cervical cancer and Pap smear screening. |

| 6 | Anaman-Torgbor et al. | 2017 | Australia | African refugee (10) and non-refugee (9) women | Qualitative | Low knowledge was identified as a barrier to cervical cancer screening participation. |

| 7 | Dalla et al. | 2022 | Greece | Syrian refugee women (176) | Quantitative | Study population had extreme low levels of knowledge regarding cervical cancer, screening methods, and HPV vaccination, assessed using Cervical CAM. |

| 8 | Dean et al. | 2017 | Australia | Sudanese refugee-background youth, age 16-24 (80 female and 149 male) | Quantitative | Low levels of STI and HIV knowledge were associated with higher sexual risk behavior. Knowledge was measured using NSASSSH. |

| 9 | Dhar et al. | 2017 | U.S.A. | Bhutanese refugee female youth (14) | Qualitative | Study population had low levels of knowledge across RH domains |

| 10 | Feresu et al. | 2013 | U.S.A. | Sudanese (86) and Somali Bantu (14) immigrant women from predominantly refugee community | Mixed methods | Knowledge on different aspects of HIV (transmission, protection, testing, etc.) was generally low and associated with low rate of condom usage. |

| 11 | Gele et al. | 2020 | Norway | Somali immigrant women (21) | Qualitative | Low levels of knowledge regarding contraceptives was associated with non-usage. |

| 12 | Haworth et al. | 2014 | U.S.A. | Bhutanese refugee women (69) | Mixed methods | Limited knowledge was identified as a barrier to Pap test utilization. History of Pap smear was associated with increased knowledge. |

| 13 | Henry et al. | 2020 | Germany | Iraqi, Syrian, and Palestinian refugee women (12) | Qualitative | Low health literacy and knowledge regarding maternal care was associated with delays in seeking care. |

| 14 | Inci et al. | 2020 | Germany | Refugee women from various countries (307) | Quantitative | History of sexual education was associated with contraceptive usage, but not associated with preference for more effective contraceptive methods. |

| 15 | Kaneoka et al. | 2020 | Scotland | Asylum seeking and refugee women from various countries (14) | Qualitative | RH literacy was in the study population was low, which was identified as a barrier to RH decision-making. |

| 16 | Kuru Alici and Ogüncer | 2024 | Turkey | Afghan refugee women (20) | Qualitative | Low and inaccurate knowledge was not associated with nonuse of contraceptives. |

| 17 | Lor et al. | 2018 | U.S.A. | Burmese (31) and Bhutanese (27) refugee women | Qualitative | Low cervical cancer knowledge was associated with low rates of screening. Health information was identified as a facilitator of health behavior and independent health decision-making |

| 18 | Madeira et al. | 2019 | U.S.A. | Somali women from a predominantly refugee community (21) | Mixed methods | Participation in group prenatal care was associated with increased knowledge. Increased knowledge was associated with increased engagement in prenatal care. |

| 19 | Metusela et al. | 2017 | Australia, Canada | Migrant and refugee women from Afghanistan (35), Iraq (27), Somalia (38), South Sudan (11), Sudan (20), India (9), Sri Lanka (12), and South America (17) | Qualitative | Study population had inadequate knowledge across multiple RH domains. Inaccurate knowledge was a barrier to RH behavior. |

| 20 | Napier-Raman et al. | 2023 | Australia | Migrant and refugee youth, age 16-26 (42 female and 13 male) from various countries (68) | Mixed methods | Study participants had lack of RH knowledge and education. Relational factors were more influential in the decision-making process than knowledge. |

| 21 | Napier-Raman et al. | 2025 | Australia | Migrant and refugee youth, age 16-26 (74 female and 32 male) from various countries (107) | Quantitative | Females had greater knowledge and awareness of contraceptive than males, but misconceptions persisted in both genders. Contraceptive utilization was not different between genders. Women had higher rates of sexual coercion, STIs, and unplanned pregnancy. |

| 22 | Ngum Chi Watts et al. | 2014 | Australia | Refugee teenagers and women from Sudan (10), Liberia (3), Ethiopia (1), Burundi (1), and Sierra Leone (1) with h/o teenage pregnancy (16) | Qualitative | Low knowledge surrounding contraceptives was identified as a deterrent to contraceptive uptake. |

| 23 | Ngum Chi Watts et al. | 2015 | Australia | Refugee teenagers and women from Sudan (10), Liberia (3), Ethiopia (1), Burundi (1), and Sierra Leone (1) with h/o teenage pregnancy (16) | Qualitative | Low and inaccurate knowledge was associated with nonuse of contraceptives. |

| 24 | Ornelas et al. | 2017 | U.S.A. | Karen-Burmese (20) and Nepali-Bhutanese (20) refugee women | Quantitative | Increased knowledge after watching cervical cancer educational videos was not consistently associated with increased intention to pursue Pap screening. |

| 25 | Rauf et al. | 2025 | U.S.A. | Afghan refugees (184), specifically Dari (67), Arabic (53), and Pashto (64) speakers | Quantitative | Reproductive health literacy scale made of HLS-EU-Q6, eHEALS, C-CLAT, and SHELA showed good inter-item reliability for this population |

| 26 | Royer et al. | 2019 | U.S.A. | Somali (41) and Congolese (25) refugee women | Qualitative | High levels of knowledge regarding available methods of contraception was not associated with contraceptive usage. |

| 27 | Zhang et al. | 2020 | U.S.A. | Somali refugee women of reproductive age (53) | Qualitative | Inaccurate knowledge was a barrier to contraceptive uptake. |

| Agbemenu et al., 2018 | Agbemenu et al., 2022 | Allen et al., 2018 | Anaman et al., 2017 | Anaman et al., 2018 | Anaman-Torgbor et al., 2017 | Dalla et al., 2022 | Dean et al., 2017 | Dhar et al., 2017 | Feresu et al., 2013 | Gele et al., 2020 | Haworth et al., 2014 | Henry et al., 2020 | Inci et al., 2020 | Kaneoka et al., 2020 | Kuru Alici & Ogüncer, 2024 | Lor et al., 2018 | Madeira et al., 2019 | Metusela et al., 2017 | Napier-Raman et al., 2023 | Napier-Raman et al., 2025 | Ngum Chi Watts et al., 2014 | Ngum Chi Watts et al., 2015 | Ornelas et al., 2017 | Rauf et al., 2025 | Royer et al., 2019 | Zhang et al., 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Abortion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cervical Cancer | X | X | X | X | CAM | X | X | X | X | ReproNet** | ||||||||||||||||||

| Family Planning | X | NSASSSH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | NSASSSH | X | X | ReproNet** | X | ||||||||||||||

| Gender-Based Violence | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HIV | X | X | WHO* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maternal Health and Obstetric Care | X | X | ReproNet** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Menstruation and Gynecological Health | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| STIs | X | X | X | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).