Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Goal of the Study

2. Research Method

- The MHD channel has a divergent geometry, with a trapezoidal cross-section (in the plane). Such a simple MHD channel has been realized in the Sakhalin pulsed MHD generator [152,153,154]. The width (along the magnetic field) is constant, and its influence is disregarded here (this is equivalent to assuming infinite width, thus two-dimensional channels).

- The charge carriers are only the free electrons in the plasma (liberated as a result of thermal ionization). This means that while ions also exist (to ensure the overall neutrality of the plasma), their contribution to the electric current is neglected [155,156]. This is a reasonable assumption given the much stronger mobility of the lighter electrons compared to the heavier ions [157,158,159].

- Unidirectional magnetic field (magnetic-field flux density) that points in the positive >-axis. Therefore, the magnetic-field flux density vector () can be expressed as , where () is a unit vector in the direction of the positive -axis. Because the magnetic field is externally applied, this assumption can be justified. In such a case, special electromagnetic designs can be made to approximate this assumption. This treatment of the magnetic field as being fully controllable implies a low magnetic Reynolds number assumption [160,161,162,163], where auxiliary induced magnetic-field flux density due to the moving plasma (the self-excitation phenomenon) is neglected [164,165,166,167]. This “inductionless” assumption [168] of a low magnetic Reynolds number is reasonable for MHD generators [169,170,171].

- Unidirectional plasma velocity that points in the positive -axis. Therefore, the plasma velocity vector () can be expressed as , where () is a unit vector in the direction of the positive -axis. Although this assumption neglects turbulence and no-slip effects in the plasma flow, it can be regarded as an acceptable treatment for deriving system-level laws, where the time-averaged bulk velocity of the plasma should be primarily in the axial direction. This assumption becomes more valid when the divergence angle of the channel decreases, so the channel height approaches uniformity. In addition, turbulence tends to be suppressed as the Mach number increases [172,173]; and our study is for supersonic channels. In addition, adopting a one-dimensional approximation for a channel flow or exterior flow has been implemented in other studies [174,175,176,177].

- No electric field along the lateral direction (along the direction of the magnetic field). This assumption is aligned with the unidirectionality assumption for the magnetic field. Even if the plasma has a three-dimensional flow velocity, the unidirectional magnetic field along the -axis is not able to induce an electric field in the same -direction. Therefore, the electric field along the -axis within the MHD plasma can only be caused by an externally applied electric field; but such a case is not considered in the current study, where there are no electrodes along the -axis to permit this.

3. Base Scalar Equations for Electric Fields in MHD Plasma

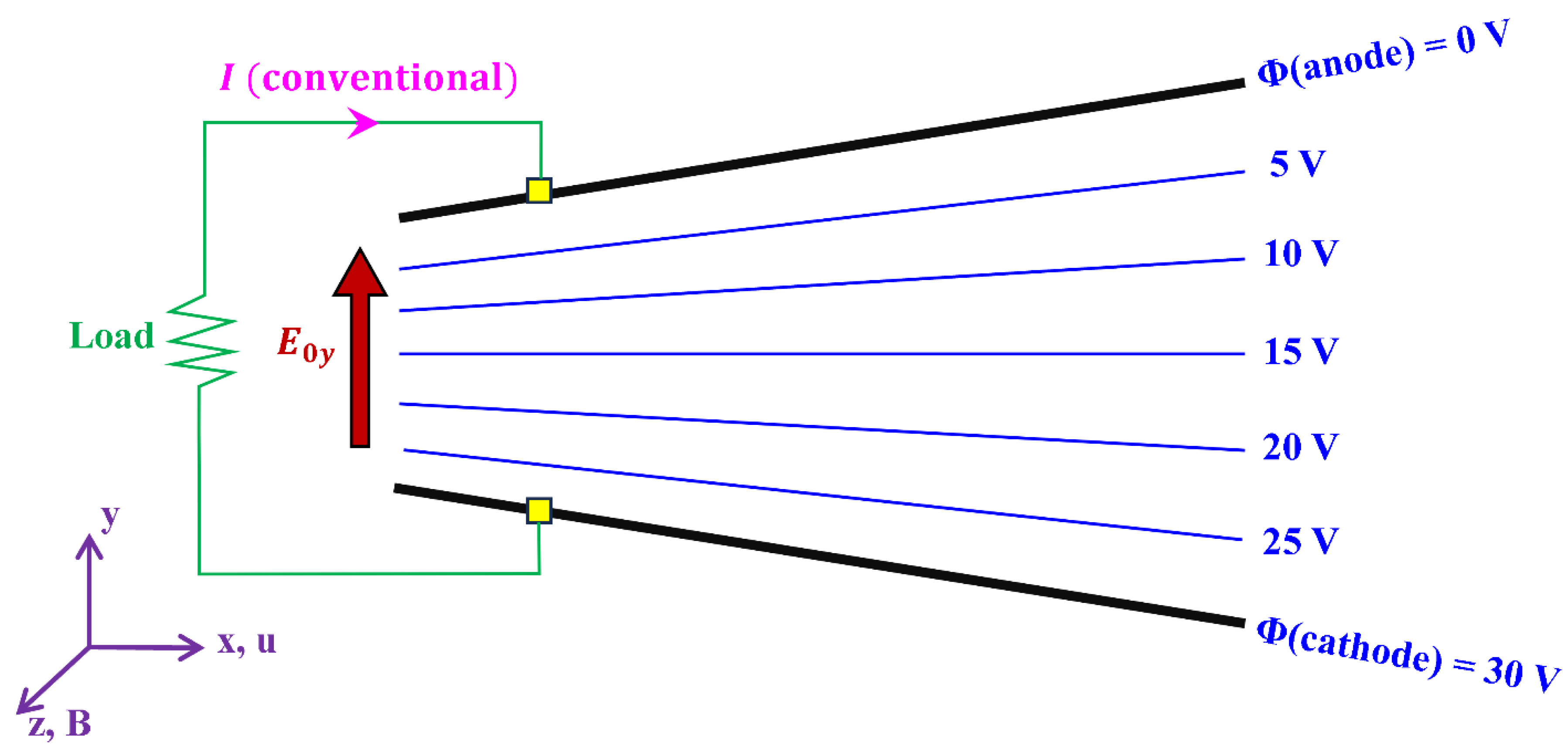

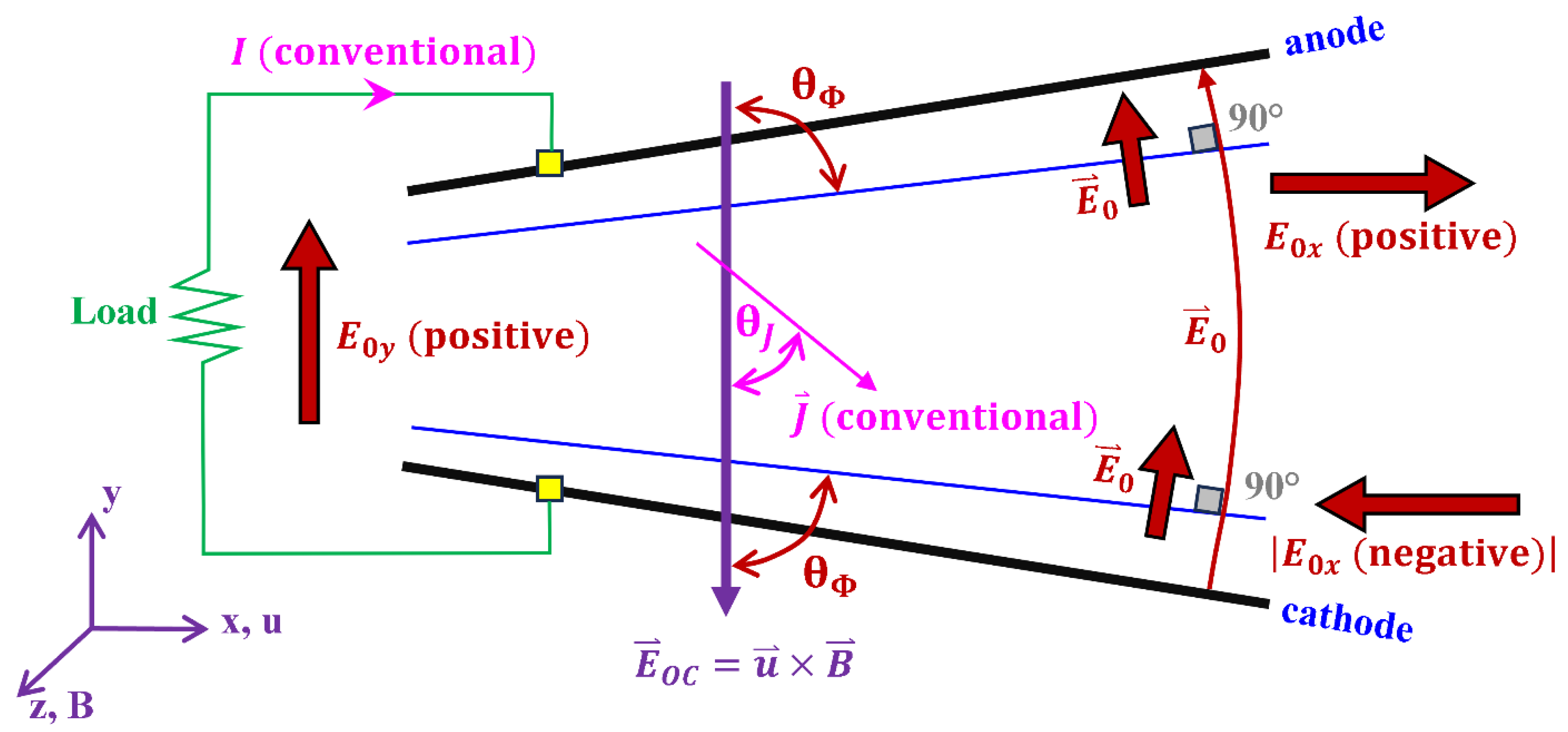

4. Continuous-Electrode Faraday Channel

5. Linear Hall Channel

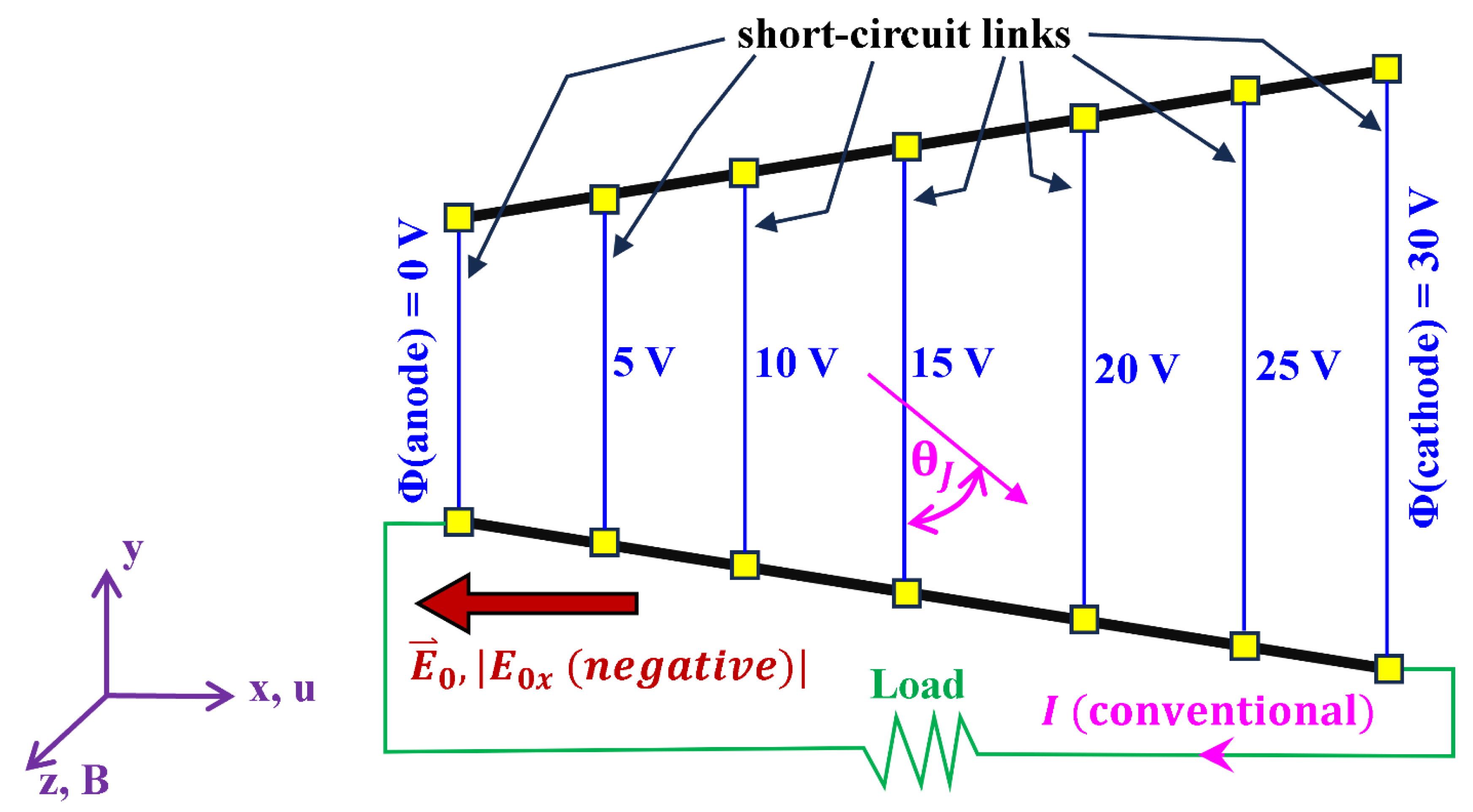

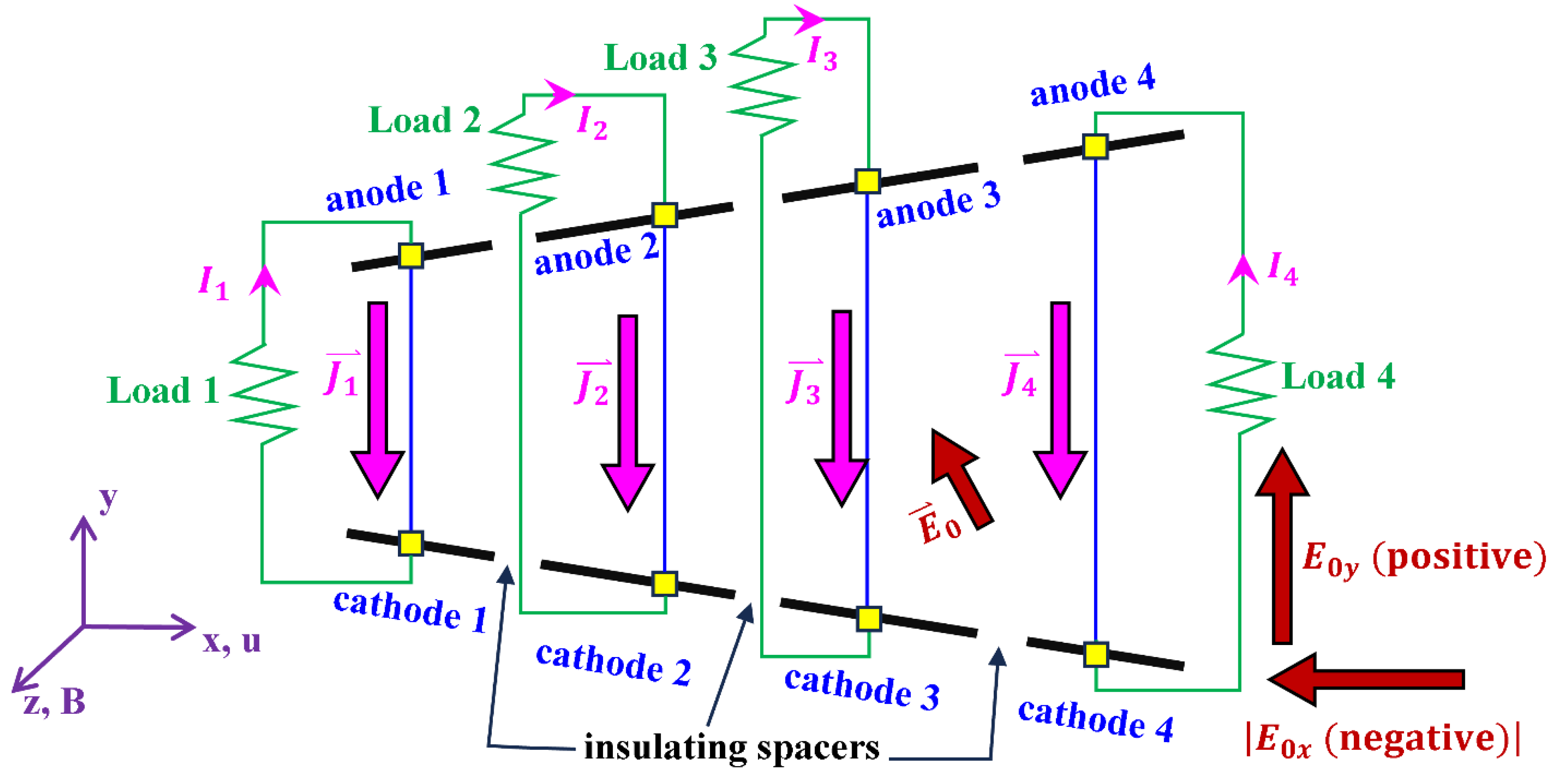

6. Segmented-Electrode Faraday Channel

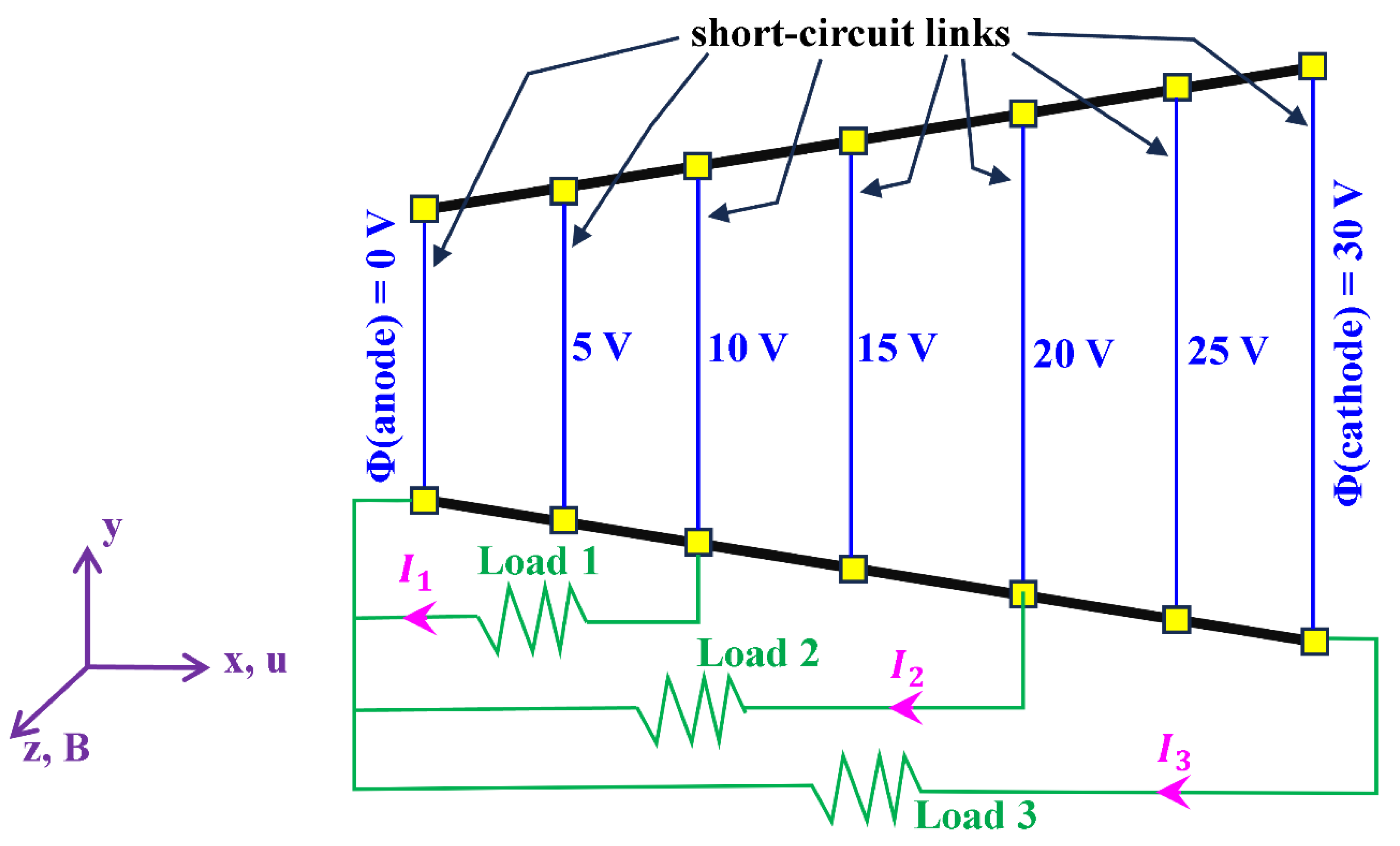

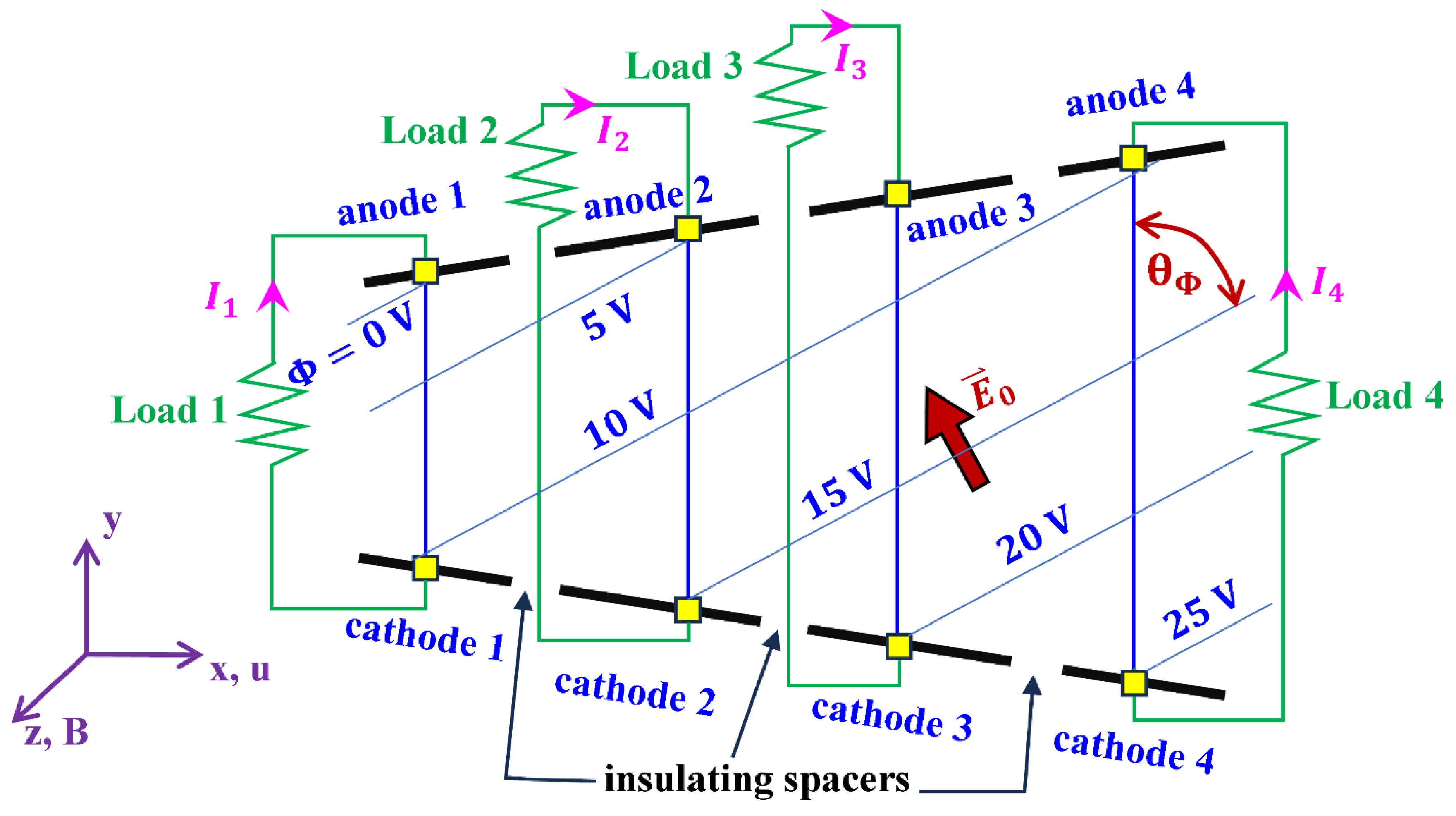

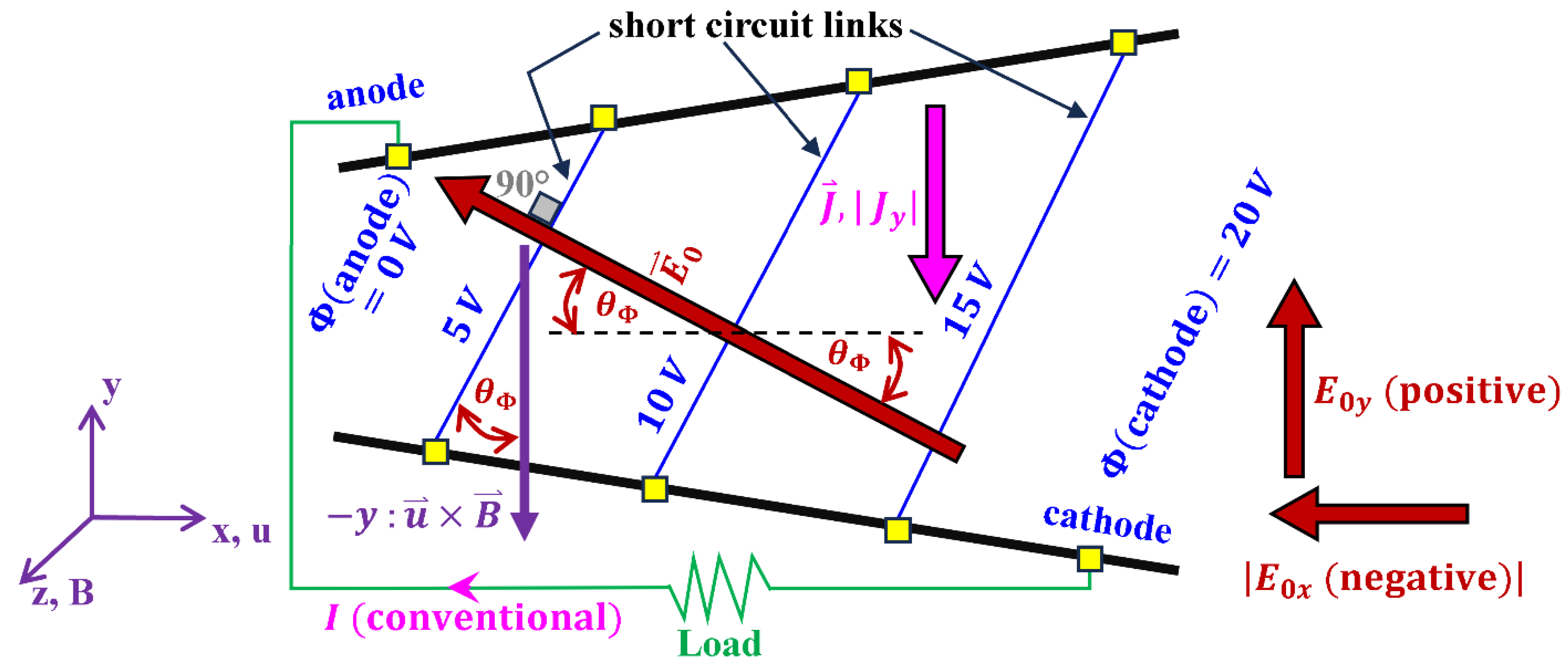

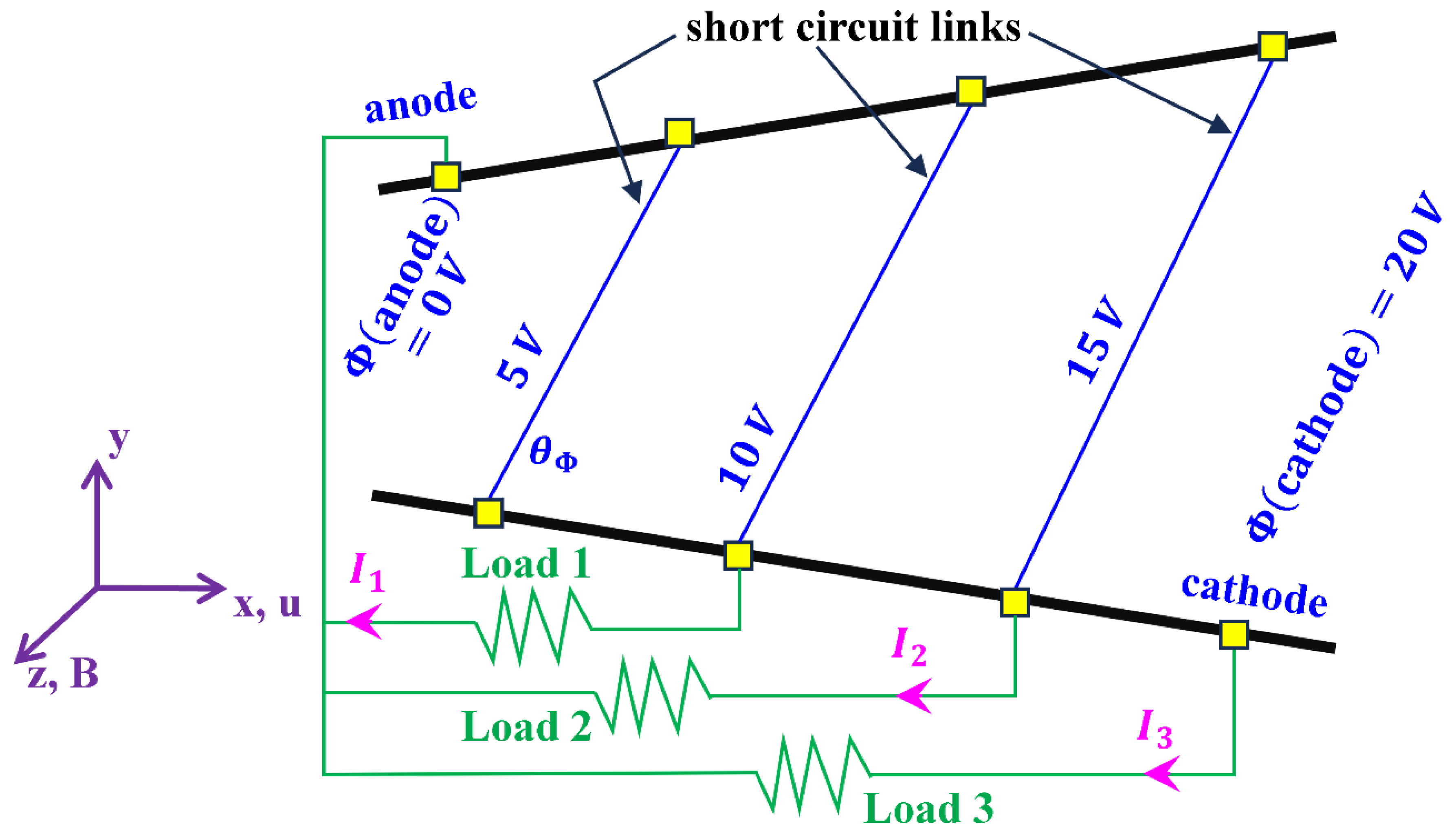

7. Diagonal-Electrode Channel

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1. V. Smil: Energy and Civilization: A History, MIT Press, 2017.

- Marzouk, O.A. Compilation of Smart Cities Attributes and Quantitative Identification of Mismatch in Rankings. Journal of Engineering 2022, 2022, 5981551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Urban air mobility and flying cars: Overview. examples, prospects, drawbacks, and solutions. Open Engineering 2022, 12, 662–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Toward More Sustainable Transportation: Green Vehicle Metrics for 2023 and 2024 Model Years, in: A.K. Nagar, D.S. Jat, D.K. Mishra, A. Joshi (Eds.), Intelligent Sustainable Systems, Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2024: pp. 261–272. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Growth in the Worldwide Stock of E-Mobility Vehicles (by Technology and by Transport Mode) and the Worldwide Stock of Hydrogen Refueling Stations and Electric Charging Points between 2020 and 2022, in: Construction Materials and Their Processing, Trans Tech Publications Ltd, Baech (Bäch), Switzerland, 2023: pp. 89–96. (accessed October 6, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Cars, R.L.E.D.-C. ; SUVs; Vans; Trucks, P.; Wagons, S. and Two Seaters for Smart Cities Based on the Environmental Damage Index (EDX) and Green Score, in: M. Ben Ahmed, A.A. Boudhir, R. El Meouche, İ.R. Karaș (Eds.), Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 7, Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, Switzerland, 2024: pp. 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Aerial e-mobility perspective: Anticipated designs and operational capabilities of eVTOL urban air mobility (UAM) aircraft. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 2025, 9, 413–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Benchmarking the Trends of Urbanization in the Gulf Cooperation Council: Outlook to 2050, in: 1st National Symposium on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Management (NSETEM’2017), WCAS [Waljat College of Applied Sciences], Muscat, Oman, 2017: pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ember, Global Electricity Review 2024, Ember, London, UK, 2024. https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/05/Report-Global-Electricity-Review-2024.pdf (accessed , 2025). 16 March.

- Marzouk, O.A. In the Aftermath of Oil Prices Fall of 2014/2015–Socioeconomic Facts and Changes in the Public Policies in the Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Management and Economics Invention 2017, 3, 1463–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency, I.E. Global electricity generation by source, 2014-2025, (2024). https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-electricity-generation-by-source-2014-2025 (accessed , 2025). 16 March.

- Santiago, I.; Moreno-Munoz, A.; Quintero-Jiménez, P.; Garcia-Torres, F.; Gonzalez-Redondo, M.J. Electricity demand during pandemic times: The case of the COVID-19 in Spain. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Adiabatic Flame Temperatures for Oxy-Methane, Oxy-Hydrogen, Air-Methane, and Air-Hydrogen Stoichiometric Combustion using the NASA CEARUN Tool, GRI-Mech 3. 0 Reaction Mechanism, and Cantera Python Package. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research 2023, 13, 11437–11444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Wang, P. Analysis of NO formation in counter-flow premixed hydrogen-air flame. Trans. Can. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2013, 37, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Subcritical and supercritical Rankine steam cycles, under elevated temperatures up to 900°C and absolute pressures up to 400 bara. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2024, 16, 16878132231221065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Huckaby, E.D. A Comparative Study of Eight Finite-Rate Chemistry Kinetics for CO/H2 Combustion. Engineering Applications of Computational Fluid Mechanics 2010, 4, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Condenser Pressure Influence on Ideal Steam Rankine Power Vapor Cycle using the Python Extension Package Cantera for Thermodynamics, Engineering. Technology & Applied Science Research 2024, 14, 14069–14078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Cantera-Based Python Computer Program for Solving Steam Power Cycles with Superheating. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering 2023, 13, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Al Kamzari, A.A.; Al-Hatmi, T.K.; Al Alawi, O.S.; Al-Zadjali, H.A.; Al Haseed, M.A.; Al Daqaq, K.H.; Al-Aliyani, A.R.; Al-Aliyani, A.N.; Al Balushi, A.A.; Al Shamsi, M.H. Energy Analyses for a Steam Power Plant Operating under the Rankine Cycle, in: A.S. Al Kalbani, R. Kanna, L.B. EP Rabai, S. Ahmad, S. Valsala (Eds.), First International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Management (UoB-IEASMA 2021), IEASMA Consultants LLP, Virtual, 2021: pp. 11–22. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Zero Carbon Ready Metrics for a Single-Family Home in the Sultanate of Oman Based on EDGE Certification System for Green Buildings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A.; Emissions, H. Global Climate Change and Environmental Precautions. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy 2006, 1, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Radiant Heat Transfer in Nitrogen-Free Combustion Environments. International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulation 2018, 19, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Chronologically-Ordered Quantitative Global Targets for the Energy-Emissions-Climate Nexus, from 2021 to 2050, in: 2022 International Conference on Environmental Science and Green Energy (ICESGE), IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers], Shenyang, China (and Virtual), 2022: pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Huckaby, E.D. Nongray EWB and WSGG Radiation Modeling in Oxy-Fuel Environments, in: J. Zhu (Ed.), Computational Simulations and Applications, IntechOpen, 2011: pp. 493–512. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Technical review of radiative-property modeling approaches for gray and nongray radiation, and a recommended optimized WSGGM for CO2/H2O-enriched gases. Results in Engineering 2025, 25, 103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Huckaby, E.D. New Weighted Sum of Gray Gases (WSGG) Models for Radiation Calculation in Carbon Capture Simulations: Evaluation and Different Implementation Techniques, in: 7th U.S. National Technical Meeting of the Combustion Institute, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2011: pp. 2483–2496. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Summary of the 2023 (1st edition) Report of TCEP (Tracking Clean Energy Progress) by the International Energy Agency (IEA), and Proposed Process for Computing a Single Aggregate Rating. E3S Web of Conferences 2025, 601, 00048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Assessment of global warming in Al Buraimi, sultanate of Oman based on statistical analysis of NASA POWER data over 39 years, and testing the reliability of NASA POWER against meteorological measurements. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Portrait of the Decarbonization and Renewables Penetration in Oman’s Energy Mix, Motivated by Oman’s National Green Hydrogen Plan. Energies 2024, 17, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Evolution of the (Energy and Atmosphere) credit category in the LEED green buildings rating system for (Building Design and Construction: New Construction), from version 4. 0 to version 4.1. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development 2024, 8, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Tilt sensitivity for a scalable one-hectare photovoltaic power plant composed of parallel racks in Muscat. Cogent Engineering 2022, 9, 2029243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Lookup Tables for Power Generation Performance of Photovoltaic Systems Covering 40 Geographic Locations (Wilayats) in the Sultanate of Oman, with and without Solar Tracking, and General Perspectives about Solar Irradiation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Intensity, E.G.; Simulator, P.V.P.P.U.T.N.E. “Aladdin,”. Energies 2024, 17, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Facilitating Digital Analysis and Exploration in Solar Energy Science and Technology through Free Computer Applications. Engineering Proceedings 2022, 31, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Land-Use competitiveness of photovoltaic and concentrated solar power technologies near the Tropic of Cancer. Solar Energy 2022, 243, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Energy Generation Intensity (EGI) for Parabolic Dish/Engine Concentrated Solar Power in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1008, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [European Wind Energy Association] EWEA, The Economics of Wind Energy, EWEA [European Wind Energy Association], Brussels, Belgium, 2009. https://books.google.com.om/books?id=3Uv5PEJYwvMC.

- Herbert, G.M.J.; Iniyan, S.; Sreevalsan, E.; Rajapandian, S. A review of wind energy technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2007, 11, 1117–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Al Badi, O.R.H.; Al Rashdi, M.H.S.; Al Balushi, H.M.E. Proposed 2MW Wind Turbine for Use in the Governorate of Dhofar at the Sultanate of Oman. Science Journal of Energy Engineering 2019, 7, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Jatropha Curcas as Marginal Land Development Crop in the Sultanate of Oman for Producing Biodiesel, Biogas, Biobriquettes, Animal Feed, and Organic Fertilizer. Reviews in Agricultural Science 2020, 8, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.; Longden, T.; Boulaire, F.; Gono, M.; Wilson, C. The application of green finance to the production of blue and green hydrogen: A comparative study. Renewable Energy 2023, 219, 119236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Performance analysis of shell-and-tube dehydrogenation module. International Journal of Energy Research 2017, 41, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. 2030 Ambitions for Hydrogen, Clean Hydrogen, and Green Hydrogen. Engineering Proceedings 2023, 56, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Levelized cost of green hydrogen (LCOH) in the Sultanate of Oman using H2A-Lite with polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolyzers powered by solar photovoltaic (PV) electricity. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 469, 00101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Expectations for the Role of Hydrogen and Its Derivatives in Different Sectors through Analysis of the Four Energy Scenarios: IEA-STEPS, IEA-NZE, IRENA-PES, and IRENA-1. 5°C. Energies 2024, 17, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Combined Oxy-fuel Magnetohydrodynamic Power Cycle, in: Conference on Energy Challenges in Oman (ECO’2015), DU [Dhofar University], Salalah, Dhofar, Oman, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, L.; Zhu, G.; Li, L. Performance investigation of plasma magnetohydrodynamic power generator. Appl. Math. Mech.-Engl. Ed. 2018, 39, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Hydrogen Utilization as a Plasma Source for Magnetohydrodynamic Direct Power Extraction (MHD-DPE). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 167088–167107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Okuno, Y.; Yamasaki, H.; Kabashima, S. Numerical simulation of plasma and fluid flow in a shock-tube-driven disk MHD generator. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2000, 28, 1706–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. One-way and two-way couplings of CFD and structural models and application to the wake-body interaction. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2011, 35, 1036–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayukawa, N. Open-cycle magnetohydrodynamic electrical power generation: a review and future perspectives. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2004, 30, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Dataset of total emissivity for CO2, H2O, and H2O-CO2 mixtures; over a temperature range of 300-2900 K and a pressure-pathlength range of 0. 01-50 atm.m. Data in Brief 2025, 59, 111428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foest, R.; Schmidt, M.; Becker, K. ; Microplasmas, an emerging field of low-temperature plasma science and technology. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2006, 248, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Temperature-Dependent Functions of the Electron–Neutral Momentum Transfer Collision Cross Sections of Selected Combustion Plasma Species. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 11282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, Y.; Kabashima, S.; Yamasaki, H.; Harada, N.; Shioda, S. Comparative studies of the performance of closed cycle disk MHD generators using argon, helium and an argon-helium mixture. Energy Conversion and Management 1985, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veefkind, A. Experiments on plasma-physical aspects of closed cycle MHD power generation. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2004, 32, 2197–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [Royal Society of Chemistry] RSC, Caesium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table, (2025). https://periodic-table.rsc.org/element/55/caesium (accessed , 2025). 16 March.

- Smith, J.F. The Cs-Nb (cesium-niobium) system and the Cs-V (cesium-vanadium) system. Bulletin of Alloy Phase Diagrams 1988, 9, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.C.; Jayaraman, A.; Newton, R.C. Fusion Curve and Polymorphic Transitions of Cesium at High Pressures. Phys. Rev. 1962, 126, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [National Center for Biotechnology Information] NCBI, PubChem │ Compound Summary for CID 5354618, Cesium, (2025). https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5354618 (accessed , 2025). 16 March.

- Boulos, M.I.; Fauchais, P.L.; Pfender, E. Thermodynamic Properties of Non-equilibrium Plasmas, in: M.I. Boulos, P.L. Fauchais, E. Pfender (Eds.), Handbook of Thermal Plasmas, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2023: pp. 385–426. [CrossRef]

- Meher, K.C.; Tiwari, N.; Ghorui, S. Thermodynamic and Transport Properties of Nitrogen Plasma Under Thermal Equilibrium and Non-equilibrium Conditions. Plasma Chem Plasma Process 2015, 35, 605–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, X.-N.; Chen, J.; Li, H.-P.; K. (Ken) Ostrikov, Non-equilibrium synergistic effects in atmospheric pressure plasmas. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starikovskaia, S.; Lacoste, D.A.; Colonna, G. Non-equilibrium plasma for ignition and combustion enhancement. Eur. Phys. J. D 2021, 75, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, J.W.M.A. Loss Mechanisms in an MHD Generator, Degree of Doctor in Technical Sciences, Technische Hogeschool Eindhoven, 1973. https://inis.iaea.org/records/kmqbd-fks05 (accessed , 2025). 17 March.

- Rosenbaum, M. MHD Project at Observatorio Nacional De Fisica Cosmica De San Miguel, in: Closed-Cycle MHD Specialists Meeting, NASA [United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration], Cleveland, Ohio, USA, 1975: pp. 1–5. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19760066328/downloads/19760066328.pdf (accessed , 2025). 17 March.

- Kobayashi, H.; Okuno, Y.; Kabashima, S. Three-dimensional simulation of nonequilibrium seeded plasma in closed cycle disk MHD generator. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 1997, 25, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suekane, T.; Maeda, T.; Okuno, Y.; Kabashima, S.; Suekane, T.; Maeda, T.; Okuno, Y.; Kabashima, S. Numerical simulation on MHD flow in disk closed cycle MHD generator, in: 28th Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 1997: p. AIAA-97-2396. [CrossRef]

- Okuno, Y.; Yamasaki, H.; Kabashima, S.; Shioda, S. Unsteady discharge and fluid flow in a closed-cycle disk MHD generator. Journal of Propulsion and Power 1988, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Fujino, T. Relation between total pressure loss in supersonic nozzle and isentropic efficiency of nonequilibrium disk-shaped MHD generator. Electrical Engineering in Japan 2021, 214, e23342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AG, L.U.I.O. ; ChemEurope │ MHD generator2025). https://www.chemeurope.com/en/encyclopedia/MHD_generator.html (accessed , 2025). 17 March.

- Harada, N.; Kien, L.C.; Hishikawa, M. Basic Studies on Closed Cycle MHD Power Generation System for Space Application, in: 35th AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Portland, Oregon, USA, 2004: p. AIAA-. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhu, A. Thermodynamic analysis of nuclear closed cycle MHD space power system, Progress in Nuclear Energy 2023, 162, 104755. [CrossRef]

- Huleihil, M. Power efficiency characteristics of MHD thermodynamic gas cycle. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2019, 11, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, N. Characteristics of a disk MHD generator with inlet swirl. Energy Conversion and Management 1999, 40, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Okamura, T.; Shioda, S. Measurements of properties concerning isentropic efficiency in a nonequilibrium MHD disk generator. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 1996, 24, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratory, A.A. ; Equations; tables, and charts for compressible flow, NACA [United States National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics], Moffett Field, California, USA, 1953. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19930091059/downloads/19930091059.pdf (accessed , 2025). 17 February.

- Williams, D.M.; Kamenetskiy, D.S.; Spalart, P.R. On stagnation pressure increases in calorically perfect, ideal gases. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2016, 58, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedkiw, R.P.; Merriman, B.; Osher, S. High Accuracy Numerical Methods for Thermally Perfect Gas Flows with Chemistry. Journal of Computational Physics 1997, 132, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Thermo Physical Chemical Properties of Fluids Using the Free NIST Chemistry WebBook Database. Fluid Mechanics Research International Journal 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Assessment of Three Databases for the NASA Seven-Coefficient Polynomial Fits for Calculating Thermodynamic Properties of Individual Species. International Journal of Aeronautical Science & Aerospace Research 2018, 5, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Direct Numerical Simulations of the Flow Past a Cylinder Moving With Sinusoidal and Nonsinusoidal Profiles. Journal of Fluids Engineering 2009, 131, 121201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laney, C.B.; Gasdynamics, C.; st ed.; Press, C.U. ; USA, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Okuno, Y.; Yamasaki, H. Achievement of the Highest Performance of Disk MHD Generator: Isentropic Efficiency of 60% and Enthalpy Extraction Ratio of 30%, in: 34th AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Orlando, Florida, USA, 2003: p. AIAA 2003–4170. [CrossRef]

- Seikel, G.R.; Plants, C.-F.O.-C.M.H.; Cooper, B.R.; Ellingson, W.A. The Science and Technology of Coal and Coal Utilization, Springer US, Boston, MA, 1984: pp. 307–337. [CrossRef]

- Hains, F.D.; Yoler, Y.A. Axisymmetric Magnetohydrodynamic Channel Flow. Journal of the Aerospace Sciences 1962, 29, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. The Sod gasdynamics problem as a tool for benchmarking face flux construction in the finite volume method. Scientific African 2020, 10, e00573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. A Flight-Mechanics Solver for Aircraft Inverse Simulations and Application to 3D Mirage-III Maneuver. Global Journal of Control Engineering and Technology 2015, 1, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Amano, R. Simulation of Supersonic MHD Channel Flows, in: 45th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007: p. AIAA 2007–403. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. A two-step computational aeroacoustics method applied to high-speed flows. Noise Control Engineering Journal 2008, 56, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, S.; Hoffmann, K.A.; Augustinus, J. Numerical Solution of the Ideal Magnetohydrodynamic Equations for a Supersonic Channel Flow. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 1998, 12, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, R.S.; Xu, Z.; Lee, C.-H. Numerical Simulation of Supersonic MHD Channel Flows, in: American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2009: pp. 669–676. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Directivity and Noise Propagation for Supersonic Free Jets, in: 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008: p. AIAA 2008–23. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Noise emissions from excited jets, in: 22nd National Conference on Noise Control Engineering (NOISE-CON 2007), INCE [Institute of Noise Control Engineering], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007: pp. 1034–1045. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Investigation of Strouhal number effect on acoustic fields, in: 22nd National Conference on Noise Control Engineering (NOISE-CON 2007), INCE [Institute of Noise Control Engineering], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007: pp. 1056–1067. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Accurate Prediction of Noise Generation and Propagation, in: 18th Engineering Mechanics Division Conference of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE-EMD), Zenodo, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, 2007: pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Changes in fluctuation waves in coherent airflow structures with input perturbation. WSEAS Transactions on Signal Processing 2008, 4, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Characteristics of the Flow-Induced Vibration and Forces With 1- and 2-DOF Vibrations and Limiting Solid-to-Fluid Density Ratios. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics 2010, 132, 041013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. A Study of the Forces on an Oscillating Cylinder, in: ASME 2007 26th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering (OMAE 2007), ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers], San Diego, California, USA, 2009: pp. 741–752. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. ; Simulation; Analysis, and Explanation of the Lift Suppression and Break of 2:1 Force Coupling Due to in-Line Structural Vibration, in: 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Schaumburg, Illinois, USA, 2008: p. AIAA 2008–2309. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Detailed Characteristics of the Resonating and Non-Resonating Flows Past a Moving Cylinder, in: 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Schaumburg, Illinois, USA, 2008: p. AIAA 2008–2311. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. ; Simulation; Modeling, and Characterization of the Wakes of Fixed and Moving Cylinders, PhD in Engineering Mechanics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech), 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/26316 (accessed , 2024). 26 November.

- Marzouk, O.; Nayfeh, A. Physical Interpretation of the Nonlinear Phenomena in Excited Wakes, in: 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008: p. AIAA 2008–1304. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Fluid Forces and Structure-Induced Damping of Obliquely-Oscillating Offshore Structures, in: The Eighteenth (2008) International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference (ISOPE-2008), ISOPE [International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers], Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2008: pp. 460–468. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.; Nayfeh, A. Differential/Algebraic Wake Model Based on the Total Fluid Force and Its Direction, and the Effect of Oblique Immersed-Body Motion on `Type-1’ and `Type-2’ Lock-in, in: 47th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting Including The New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Orlando, Florida, USA, 2009: p. AIAA 2009–1112. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Hydrodynamic Forces on a Moving Cylinder with Time-Dependent Frequency Variations, in: 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008: p. AIAA 2008–680. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Reduction of the loads on a cylinder undergoing harmonic in-line motion. Physics of Fluids 2009, 21, 083103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Loads on a Harmonically Oscillating Cylinder, in: ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC-CIE 2007), ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers], Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2009: pp. 1755–1774. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Airfoil Design Using Genetic Algorithms, in: The 2007 International Conference on Scientific Computing (CSC’07), The 2007 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (WORLDCOMP’07), CSREA Press, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2007: pp. 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Bobashev, S.; Erofeev, A.; Lapushkina, T.; Zhukov, B.; Poniaev, S.; Vasilieva, R.; Wie, D.V. Air Plasma Produced by Gas Discharge in Supersonic MHD Channel, in: 44th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2006: p. AIAA 2006–1373. [CrossRef]

- Bobashev, S.V.; Vasil’eva, R.V.; Erofeev, A.V.; Lapushkina, T.A.; Poniaev, S.A.; Van Wie, D.M. Local effect of electric and magnetic fields on the position of an attached shock in a supersonic diffuser. Tech. Phys. 2003, 48, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, P.A.; Elliott, S.; Gordeyev, S.; Kemnetz, M.R.; Leonov, S.B. Flow Structure behind Spanwise Pin Array in Supersonic Flow. Aerospace 2024, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchford, R.; Thompson, B.; Lineberry, J. Pulse detonation MHD experiments, in: 29th AIAA, Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA, 1998: p. AIAA-98-2918. [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Vasilyak, L.; Carraro, M.; Zaidi, S.; Shneider, M.; Macheret, S.; Miles, R. Observation of MHD Effects with Non-Equlibrium Ionization in Cold Supersonic Air Flows, in: 42nd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2004: p. AIAA 2004–1025. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.L.; Sarma, P.R.L. Current distribution at the end regions of a magnetohydrodynamic channel. Journal of Energy 1979, 3, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheret, S.; Schneider, M.; Murray, R.; Zaidi, S.; Vasilyak, L.; Miles, R. RDHWT/MARIAH II MHD Modeling and Experiments Review, in: 24th AIAA Aerodynamic Measurement Technology and Ground Testing Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Portland, Oregon, USA, 2004: p. AIAA 2004–2485. [CrossRef]

- Brogan, T. The Mark V 32 MW Self Excited MHD Generator, in: 43rd AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 2012: p. AIAA 2012–3175. [CrossRef]

- TEMPELMEYER, K.E.; RITTENHOUSE, L.E.; WILSON, D.R. Experiments on a Faraday-type MHD accelerator with series-connected electrodes. AIAA Journal 1965, 3, 2160–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchford, R.J. Performance Theory of Diagonal Conducting Wall Magnetohydrodynamic Accelerators. Journal of Propulsion and Power 2004, 20, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchford, R. Performance Theory of Diagonal Conducting Wall MHD Accelerators, in: 34th AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Orlando, Florida, USA, 2003: p. AIAA 2003–4284. [CrossRef]

- Veefkind, A.; Blom, J.H.; Rietjens, L.H.T. Theoretical and experimental investigation of a non-equilibrium plasma in a MHD channel, Technische Hogeschool Eindhoven, Eindhoven, Netherlands, 1968. https://research.tue.nl/en/publications/theoretical-and-experimental-investigation-of-a-non-equilibrium-p (accessed , 2025). 23 March.

- Anwari, M.; Sakamoto, N.; Hardianto, T.; Kondo, J.; Harada, N. Numerical analysis of magnetohydrodynamic accelerator performance with diagonal electrode connection. Energy Conversion and Management 2006, 47, 1857–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Bhadoria, B.S.; Verma, S.S. Performance of a MHD retrofit channel with diagonal electrode geometry. Energy Conversion and Management 1996, 37, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardianto, T.; Sakamoto, N.; Harada, N. Study of a Diagonal Channel MHD Power Generation, in: 45th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007: p. AIAA 2007–398. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Detailed and simplified plasma models in combined-cycle magnetohydrodynamic power systems. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2023, 10, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Multi-Physics Mathematical Model of Weakly-Ionized Plasma Flows. American Journal of Modern Physics 2018, 7, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Estimated electric conductivities of thermal plasma for air-fuel combustion and oxy-fuel combustion with potassium or cesium seeding. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk, O.A. Power Density and Thermochemical Properties of Hydrogen Magnetohydrodynamic (H2MHD) Generators at Different Pressures, Seed Types, Seed Levels, and Oxidizers. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Coupled differential-algebraic equations framework for modeling six-degree-of-freedom flight dynamics of asymmetric fixed-wing aircraft. International Journal of Applied and Advanced Sciences 2025, 12, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. New Wake Models With Capability of Capturing Nonlinear Physics, in: ASME 2008 27th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering (OMAE 2008), ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers], Estoril, Portugal, 2009: pp. 901–912. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. A Nonlinear ODE System for the Unsteady Hydrodynamic Force - A New Approach, World Academy of Science. Engineering and Technology 2009, 39, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Mitigation of Ship Motion Using Passive and Active Anti-Roll Tanks, in: ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC-CIE 2007), ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers], Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2009: pp. 215–229. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Control of ship roll using passive and active anti-roll tanks. Ocean Engineering 2009, 36, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. A Parametric Study and Optimization of Ship-Stabilization Systems, in: 1st WSEAS International Conference on Maritime and Naval Science and Engineering (MN’08), WSEAS [World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society], Malta, 2008: pp. 169–174. https://www.worldses.org/books/2008/malta/finite_differences_finite_elements_finite_volumes_and_boundary_elements.pdf (accessed , 2024). 21 September.

- Marzouk, O.A. Evolutionary Computing Applied to Design Optimization, in: ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (IDETC-CIE 2007), (), ASME [American Society of Mechanical Engineers], Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2009: pp. 995–1003. 4–7 September. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Status of ABET Accreditation in the Arab World. Global Journal of Educational Studies 2019, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Accrediting Artificial Intelligence Programs from the Omani and the International ABET Perspectives, in: K. Arai (Ed.), Intelligent Computing, Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, 2021: pp. 462–474. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Benchmarks for the Omani higher education students-faculty ratio (SFR) based on World Bank data, QS rankings, and THE rankings. Cogent Education 2024, 11, 2317117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. English Programs for non-English Speaking College Students, in: 1st Knowledge Globalization Conference 2008 (KGLOBAL 2008), Sawyer Business School, Suffolk University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 2008: pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. University Role in Promoting Leadership and Commitment to the Community, in: Inaugural International Forum on World Universities, Davos, Switzerland (and Virtual), 2008. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Globalization and diversity requirement in higher education, in: The 11th World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics (WMSCI 2007) - The 13th International Conference on Information Systems Analysis and Synthesis (ISAS 2007), IIIS [International Institute of Informatics and Systemics], Orlando, Florida, USA, 2007: pp. 101–106. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Retention, B. ; Progression, and Graduation Rates in Undergraduate Higher Education Across Different Time Windows. Cogent Education 2025, 12, 2498170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Utilizing Co-Curricular Programs to Develop Student Civic Engagement and Leadership. The Journal of the World Universities Forum 2008, 1, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Jul, W.A.M.H.R.; Al Jabri, A.M.K.; Al-ghaithi, H.A.M.A. Construction of a Small-Scale Vacuum Generation System and Using It as an Educational Device to Demonstrate Features of the Vacuum. International Journal of Contemporary Education 2018, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Reduced-Order Modeling (ROM) of a Segmented Plug-Flow Reactor (PFR) for Hydrogen Separation in Integrated Gasification Combined Cycles (IGCC). Processes 2025, 13, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Huckaby, E.D. Simulation of a Swirling Gas-Particle Flow Using Different k-epsilon Models and Particle-Parcel Relationships. Engineering Letters 2010, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Nayfeh, A.H. Characterization of the flow over a cylinder moving harmonically in the cross-flow direction. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 2010, 45, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Huckaby, E.D. Effects of Turbulence Modeling and Parcel Approach on Dispersed Two-Phase Swirling Flow, in: World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2009 (WCECS 2009), IAENG [International Association of Engineers], San Francisco, California, USA, 2009: pp. 1–11. https://www.iaeng.org/publication/WCECS2009/WCECS2009_pp972-982.pdf (accessed , 2024). 21 September.

- Marzouk, O.A.; Huckaby, E.D. Modeling Confined Jets with Particles and Swril, in: S.-I. Ao, B. Rieger, M.A. Amouzegar (Eds.), Machine Learning and Systems Engineering, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2010: pp. 243–256. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Huckaby, E.D. Assessment of syngas kinetic models for the prediction of a turbulent nonpremixed flame, in: Fall Meeting of the Eastern States Section of the Combustion Institute 2009, College Park, Maryland, USA, 2009: pp. 726–751. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Validating a Model for Bluff-Body Burners Using the HM1 Turbulent Nonpremixed Flame. Journal of Advanced Thermal Science Research 2016, 3, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, V.P. ; Preliminary analysis of the “Sakhalin” world largest pulsed MHD generator, in: 4th Workshop on Magnetoplasma Aerodynamics for Aerospace Applications, Moscow, Russia, 2002: pp. 322–331.

- Velikhov, E.P.; Pismenny, V.D.; Matveenko, O.G.; Panchenko, V.P.; Yakushev, A.A.; Pisakin, A.V.; Blokh, A.G.; Tkachenko, B.G.; Sergienko, N.M.; Zhukov, B.B.; Zhegrov, E.F.; Babakov, Y.P.; Polyakov, V.A.; Glukhikh, V.A.; Manukyan, G.S.; Krylov, V.A.; Vesnin, V.A.; Parkhomenko, V.A.; Sukharev, E.M.; Malashko, Y.I.; MHD power system, P. “Sakhalin” - The world largest solid propellant fueled MHD generator of 500MWe electric power output, in: 13th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation and High Temperature Technologies, Beijing, China, 1999: pp. 387–398.

- Panchenko, V.P.; Analysis of the, P. “Sakhalin” World Largest Pulsed MHD Generator, in: 33rd Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Maui, Hawaii, USA, 2002: p. AIAA-. [CrossRef]

- Khrapak, S.A.; Khrapak, A.G. On the conductivity of moderately non-ideal completely ionized plasma. Results in Physics 2020, 17, 103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, T.E.; Goree, J.A. Analytic expression for the electric potential in the plasma sheath. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 1989, 17, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, G.G.; Tsygankov, S.F. Reflection of radio waves from a meteor trail containing two kinds of ions. Radiophys Quantum Electron 1981, 24, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucquin-Desreux, B. Diffusion of electrons by multicharged ions. Math. Models Methods Appl. Sci. 2000, 10, 409–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, R. A theory about induced electric current and heating in plasma. Natural Science 2011, 3, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaepen, B.; Moreau, R. Magnetohydrodynamic Turbulence at Low Magnetic Reynolds Number. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2008, 40, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Choi, H. Magnetohydrodynamic turbulent flow in a channel at low magnetic Reynolds number. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2001, 439, 367–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.A. An Introduction to Magnetohydrodynamics, Cambridge University Press, USA, 2001.

- Rosa, R.J.; Krueger, C.H.; Shioda, S. Plasmas in MHD power generation. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 1991, 19, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Hoffmann, K.; Dietiker, J.-F. Validity of Low Magnetic Reynolds Number Formulation of Magnetofluiddynamics, in: 38th Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Miami, Florida, USA, 2007: p. AIAA 2007–4374. [CrossRef]

- van Oeveren, S.B.; Gildfind, D.; Wheatley, V.; Gollan, R.; Jacobs, P. Numerical Study of Magnetic Field Deformation for a Blunt Body with an Applied Magnetic Field During Atmospheric Entry, in: AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Orlando, Florida, USA, 2024: p. AIAA 2024–1646. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, C.D.; Demetriades, S.T. Initial tests of a lightweight, self-excited MHD power generator. Journal of Propulsion and Power 1986, 2, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirino, T.S.; Verissimo, G.L.; Colaço, M.J. Numerical Analysis of a MHD Generator with Helical Geometry. CTS 2022, 14, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolentsev, S.; Cuevas, S.; Beltrán, A. Induced electric current-based formulation in computations of low magnetic Reynolds number magnetohydrodynamic flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2010, 229, 1558–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikhov, E.P.; Golubev, V.S.; Dykhne, A.M. Physical Phenomena in a Low-Temperature Non-Equilibrium Plasma and in MHD Generators with Generators with Non-Equilibrium Conductivity, IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency], Vienna, Austria, 1976. https://inis.iaea.org/records/e28xk-19082/files/53066451.pdf (accessed , 2025). 20 March.

- Aithal, S.M. Characteristics of optimum power extraction in a MHD generator with subsonic and supersonic inlets. Energy Conversion and Management 2009, 50, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Okuno, Y. Improvement of Plasma-flow Behavior and Performance of a Disk MHD Generator under High Magnetic Flux Densities. IEEJ Transactions on Power and Energy 2008, 128, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Oyama, A.; Yakeno, A.; Hamada, S. Mach Number Effect on the Drag Reducing Performance of the Riblet in the Transition and Turbulent Flow, in: AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Orlando, Florida, USA, 2024: p. AIAA 2024–0890. [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, N.J.; Wernet, M.P.; Locke, R.J.; Eck, D.G. Mach Number and Heating Effects on Turbulent Supersonic Jets. AIAA Journal 2024, 62, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyahia, S. A time-averaged model for gas–solids flow in a one-dimensional vertical channel. Chemical Engineering Science 2008, 63, 2536–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, A.; Kavvas, M.L. Time–space fractional governing equations of one-dimensional unsteady open channel flow process: Numerical solution and exploration. Hydrological Processes 2017, 31, 2961–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Wind Speed Weibull Model Identification in Oman, and Computed Normalized Annual Energy Production (NAEP) From Wind Turbines Based on Data From Weather Stations. Engineering Reports 2025, 7, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsiorowski, D.; Napiórkowski, J.J.; Szymkiewicz, R. One-Dimensional Modeling of Flows in Open Channels, in: P. Rowiński, A. Radecki-Pawlik (Eds.), Rivers – Physical, Fluvial and Environmental Processes, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015: pp. 137–167. [CrossRef]

- Núñez, M. Generalized Ohm’s law and geometric optics: Applications to magnetosonic waves. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 2019, 110, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.W.; Sherman, A.; Magnetohydrodynamics, E.; Publications, C.D. ; Mineola; York, N.; USA, 2006. https://books.google.com.om/books?id=yJaRDQAAQBAJ (accessed , 2025). 19 March.

- Sakamoto, N.; Harada, N. Three-dimensional Computational Study on a Magnetohydrodynamic Accelerator in Hall Current Neutralized Condition. IEEJ Transactions on Fundamentals and Materials 2008, 128, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshak, A.H.; van Vliet, K.M. Electrical current in solids with position-dependent band structure, Solid-State Electronics 1978, 21, 417–427. [CrossRef]

- Nakachai, R.; Poonsawat, S.; Sutthinet, C.; Ruangphanit, A.; Poyai, A.; Phetchakul, T. Horizontal Magnetic Field MAGFET by Conventional MOSFET Structure, in: 2018 International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON), 2018: pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, D.; Aimi, M.; Saito, H.; Hirose, K. Time-Domain Component Analysis of Heavy-Ion-Induced Transient Currents in Fully-Depleted SOI MOSFETs. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2006, 53, 3372–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menart, J.; Shang, J.; Hayes, J. Development of a Langmuir probe for plasma diagnostic work in high speed flow, in: 32nd AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Anaheim, California, USA, 2001: p. AIAA 2001–2804. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Tashiro, S.; Nomura, K.; Wu, D.; Tanaka, M. Elucidation of arc coupling mechanism in plasma-MIG hybrid welding process through spectroscopic measurement of 3D distributions of plasma temperature and iron vapor concentration. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2022, 77, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezmes, A.O.; Breitkopf, C. Simulation of inductively coupled plasma with applied bias voltage using COMSOL. Vacuum 2014, 109, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [United States National Institute of Standards and Technology] NIST, CODATA [Committee on Data for Science and Technology] Value: elementary charge, (2025). https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?e (accessed , 2025). 20 March.

- Instruments, N.; Constant, E.C. 2023). https://www.ni.com/docs/en-US/bundle/labview-nxg-nodes-api-ref/page/elementary-charge.html (accessed , 2025). 20 March.

- Jeckelmann, B.; Piquemal, F. The Elementary Charge for the Definition and Realization of the Ampere. Annalen Der Physik 2019, 531, 1800389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.H.; Rice, T.M.; Brinkman, W.F. Hall voltage and current distributions in an ideal two-dimensional system. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 28, 3648–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasawa, T. Hall current effect on tearing mode instability. Geophysical Research Letters 1983, 10, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Maqbool, K.; Hayat, T. Influence of Hall current on the flows of a generalized Oldroyd-B fluid in a porous space. Acta Mechanica 2006, 184, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchford, R.J.; Cole, J.W.; Lineberry, J.T.; Chapman, J.N.; Schmidt, H.J.; Lineberry, C.W. Magnetohydrodynamic Augmented Propulsion Experiment: I. Performance Analysis and Design, NASA [United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration], MSFC [Marshall Space Flight Center], Alabama, USA, 2003. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20030025730/downloads/20030025730.pdf (accessed , 2025). 19 March.

- Bogdanoff, D.; Mehta, U. Experimental Demonstration of MHD Acceleration, in: 34th AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Orlando, Florida, USA, 2003: p. AIAA 2003–4285. [CrossRef]

- Brogan, T. The 20MW LORHO MHD accelerator for wind tunnel drive - Design, construction and critique, in: 30th Plasmadynamic and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Norfolk, Virginia, USA, 1999: p. AIAA-99-3720. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, S.W. ; Direct energy conversion; ed; Allyn; Bacon; Boston; Massachusetts; USA, 1982.

- Israelevich, P.L.; Gombosi, T.I.; Ershkovich, A.I.; DeZeeuw, D.L.; Neubauer, F.M.; Powell, K.G. The induced magnetosphere of comet Halley: 4. Comparison of in situ observations and numerical simulations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 1999, 104, 28309–28319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Flow control using bifrequency motion. Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics 2011, 25, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Contrasting the Cartesian and polar forms of the shedding-induced force vector in response to 12 subharmonic and superharmonic mechanical excitations. Fluid Dynamics Research 2010, 42, 035507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickler, D.B.; DeSaro, R. Slag Interaction Phenomena on MHD Generator Electrodes. Journal of Energy 1977, 1, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Umoto, J. Influences of coal slag on electrical characteristics of a Faraday MHD generator. Energy Conversion and Management 1989, 29, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agee, F.J.; Lehr, F.M.; Vigil, M.; Kaye, R.; Gaudet, J.; Shiffler, D. ; Explosively-driven magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) generator studies, in: Digest of Technical Papers. Tenth IEEE International Pulsed Power Conference, 1995: pp. 1068–1073 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A. Thermoelectric generators versus photovoltaic solar panels: Power and cost analysis. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 2024, 8, 406–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T. ; Fujino,Takayasu; Ishikawa, Comparison of Generator Performance of Small-Scale MHD Generators with Different Electrode Dispositions and Load Connection Systems. Journal of International Council on Electrical Engineering 2014, 4, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerle, H.K. Magnetohydrodynamic Electrical Power Generation, Wiley, Chichester, England, UK, 1995.

- Murakami, T.; Okuno, Y. Experiment and simulation of MHD power generation using convexly divergent channel, in: 42nd AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Swallom, D.W.; Goldfarb, V.M.; Gibbs, J.S.; Sadovnik, I.; Zeigarnik, V.A.; Kuzmin, R.K.; Aitov, N.L.; Okunev, V.I.; Novikov, V.A.; Rickman, V.J.; Blokh, A.G.; Pisakin, A.V.; Egorushkin, P.N.; Tkachenko, B.G.; Babakov, J.P.; Olson, A.M.; Anderson, R.E.; Fedun, M.A.; Hill, G.R. Results from the Pamir-3U pulsed portable MHD power system program, in: 12th International Conference on MHD Electrical Power Generation, Yokohama, Japan, 1996: pp. 186–195.

- Sugita, H.; Matsuo, T.; Inui, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Two-dimensional analysis of gas-particle two phase flow in pulsed MHD channel, in: 30th Plasmadynamic and Lasers Conference, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Norfolk, Virginia, USA, 1999: p. AIAA-99-3483. [CrossRef]

- Koshiba, Y.; Yuhara, M.; Ishikawa, M. Two-Dimensional Analysis of Effects of Induced Magnetic Field on Generator Performance of a Large-Scale Pulsed MHD Generator, in: 35th AIAA Plasmadynamics and Lasers Conference, AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics], Portland, Oregon, USA, 2004: p. AIAA-. [CrossRef]

- Chejarla, V.S.; Ahmed, S.; Belz, J.; Scheunert, J.; Beyer, A.; Volz, K. Measuring Spatially-Resolved Potential Drops at Semiconductor Hetero-Interfaces Using 4D-STEM. Small Methods 2023, 7, 2300453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordes, C.; Brito, D.; Garambois, S.; Holzhauer, J.; Jouniaux, L.; Dietrich, M. Laboratory Measurements of Coseismic Fields, in: Seismoelectric Exploration. American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2020: pp. 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Umoh, I.J.; Kazmierski, T.J.; Al-Hashimi, B.M. A Dual-Gate Graphene FET Model for Circuit Simulation—SPICE Implementation. IEEE Transactions on Nanotechnology 2013, 12, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, L.S. Conductivity of Seeded Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas. Journal of Applied Physics 1961, 32, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freck, D.V. On the electrical conductivity of seeded air combustion products. Br. J. Appl. Phys. 1964, 15, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, V.H. M.S. Jones Jr..; Demetriades, A. MHD power generation studies in rectangular channels, in: Proceedings of the 2nd Symposium on the Engineering Aspects of Magnetohydrodynamics (EAMHD-2), Columbia University Press, New York and London, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 1961: pp. 180–210.

- Klepeis, J.E.; Hruby, V. Development program for MHD power generation. Volume II. Disk generator performance. Final report, --31 December 1976, Avco-Everett Research Lab. Inc. Everett, MA (USA), USA, 1977. 1 July. [CrossRef]

- Medin, S.A. MAGNETOHYDRODYNAMIC ELECTRICAL POWER GENERATORS, in: Thermopedia, Begel House Inc. 2011. [CrossRef]

- ERASLAN, A.H. Temperature distributions in MHD channels with Hall effect. AIAA Journal 1969, 7, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WU, Y.C.L.; DICKS, J.B.; DENZEL, D.L.; WITKOWSKI, S.; SHANKLIN, R.V.; ZITZOW, U.; CHANG, P.; JETT, E.S. MHD generator in two-terminal operation. AIAA Journal 1968, 6, 1651–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, G.; Kazimierczuk, M.K.; Massarini, A.; Reggiani, U.; Sancineto, G. Model of laminated iron-core inductors for high frequencies. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2004, 40, 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdaleno-Adame, S.; Kefalas, T.D.; Garcia-Martinez, S.; Perez-Rojas, C. Electromagnetic finite element analysis of electrical steels combinations in lamination core steps of single-phase distribution transformers, in: 2017 IEEE International Autumn Meeting on Power, Electronics and Computing (ROPEC), 2017: pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Moses, A.J.; Pegler, S.M. The effects of flexible bonding of laminations in a transformer core. Journal of Sound and Vibration 1973, 29, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kien, L.C. Numerical calculations and analyses in diagonal type MHD generator. Vietnam Journal of Science and Technology 2014, 52, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, F.; Tanaka, M.; Murakami, T.; Okuno, Y. Experiments on High-Temperature Inert Gas Plasma MHD Electrical Power Generation with Hall and Diagonal Connections. Electrical Engineering in Japan 2015, 193, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardianto, T.; Sakamoto, N.; Harada, N. Three Dimensional Flow Analyses in a Diagonal Type MHD Generator. AJAS 2006, 3, 1973–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hall Parameter | Power Penalty Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous-electrode Faraday | Linear Hall | ||

| 0 | 100% | 0% | 0 |

| 0.25 | 94.1176% | 5.8824 | 0.0625 |

| 0.5 | 80% | 20% | 0.25 |

| 0.75 | 64% | 36% | 0.5625 |

| 1 | 50% | 50% | 1 |

| 1.25 | 39.0244% | 60.9756% | 1.5625 |

| 1.5 | 30.7692% | 69.2308% | 2.25 |

| 1.75 | 24.6154% | 75.3846% | 3.0625 |

| 2 | 20% | 80% | 4 |

| 2.5 | 13.793% | 86.2069% | 6.25 |

| 3 | 10% | 90% | 9 |

| 4 | 5.8824% | 94.1176% | 16 |

| 5 | 3.8462% | 96.1538% | 25 |

| 6 | 2.7027% | 97.2973% | 36 |

| 7 | 2% | 98% | 49 |

| 8 | 1.5385% | 98.4615% | 64 |

| 9 | 1.2195% | 98.7805% | 81 |

| 10 | 0.9901% | 99.0099% | 100 |

| Quantity | Continuous-electrode Faraday | Linear Hall |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | ||

| 0 | ||

| P | ||

| Number of loads | 1 | 1 or more |

| Quantity | Segmented-electrode Faraday | Diagonal-electrode |

|---|---|---|

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| P | Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | |

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| Same as segmented-electrode Faraday | ||

| Number of loads | multiple | 1 or more |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).