Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Gap

1.2. Research Questions

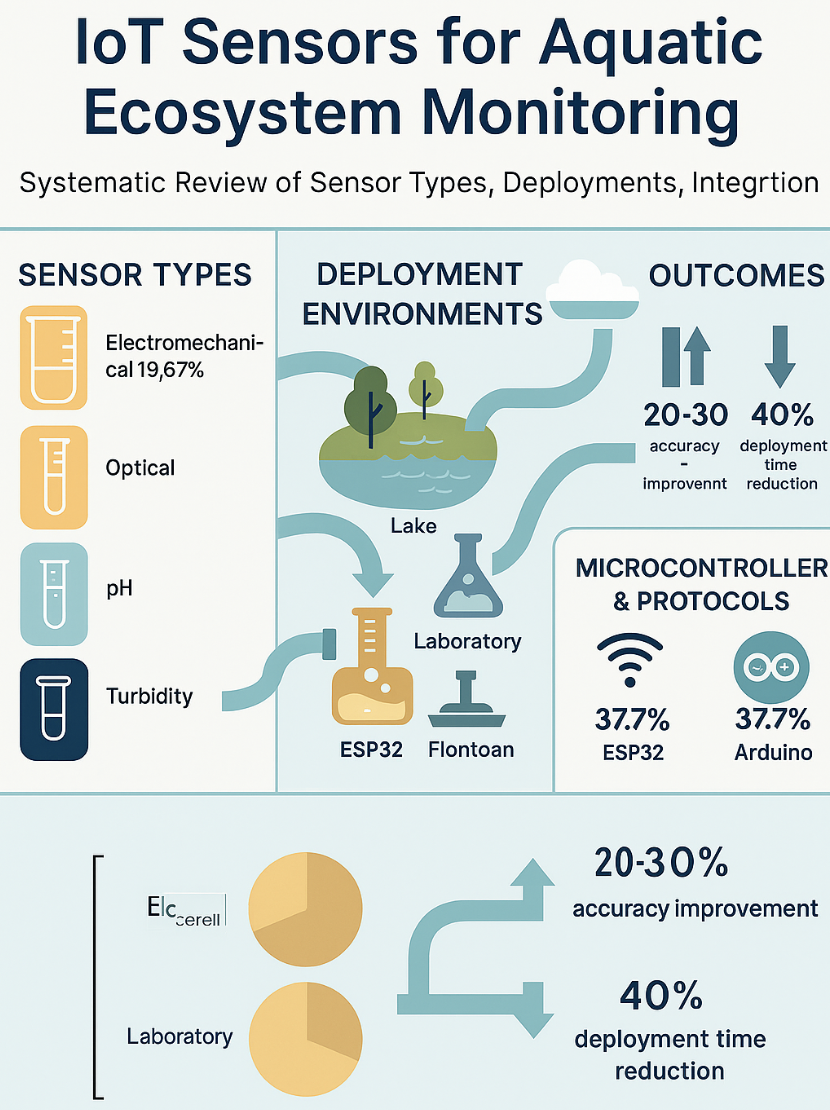

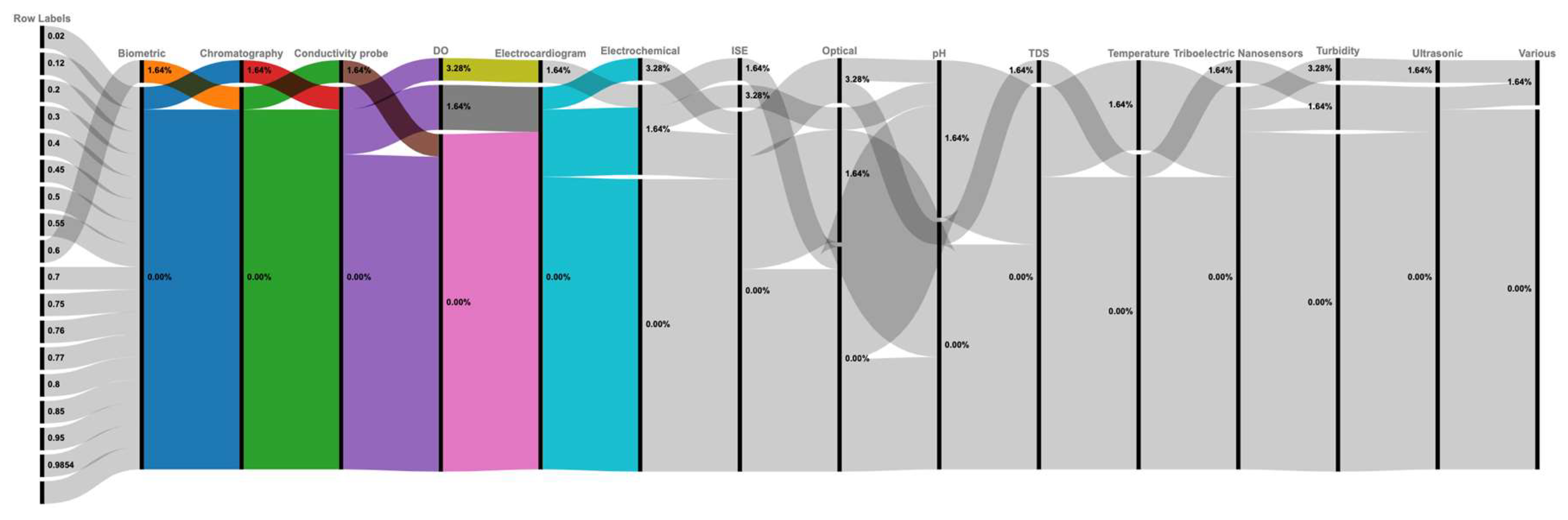

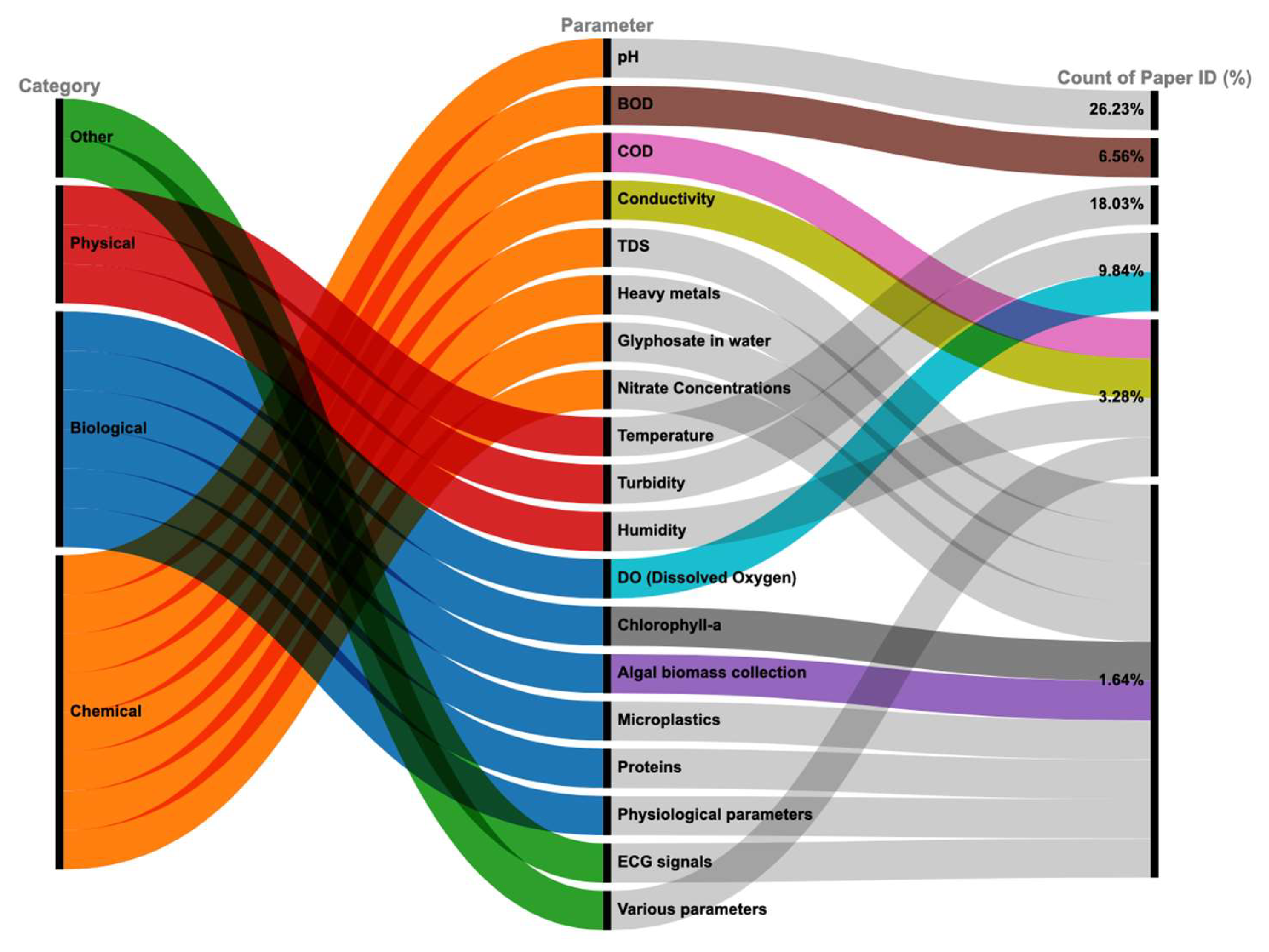

- How do different IoT sensor technologies (e.g., optical, electrochemical, biosensors) compare in their ability to measure critical biological indicators such as dissolved oxygen, pH, and turbidity under diverse aquatic conditions?

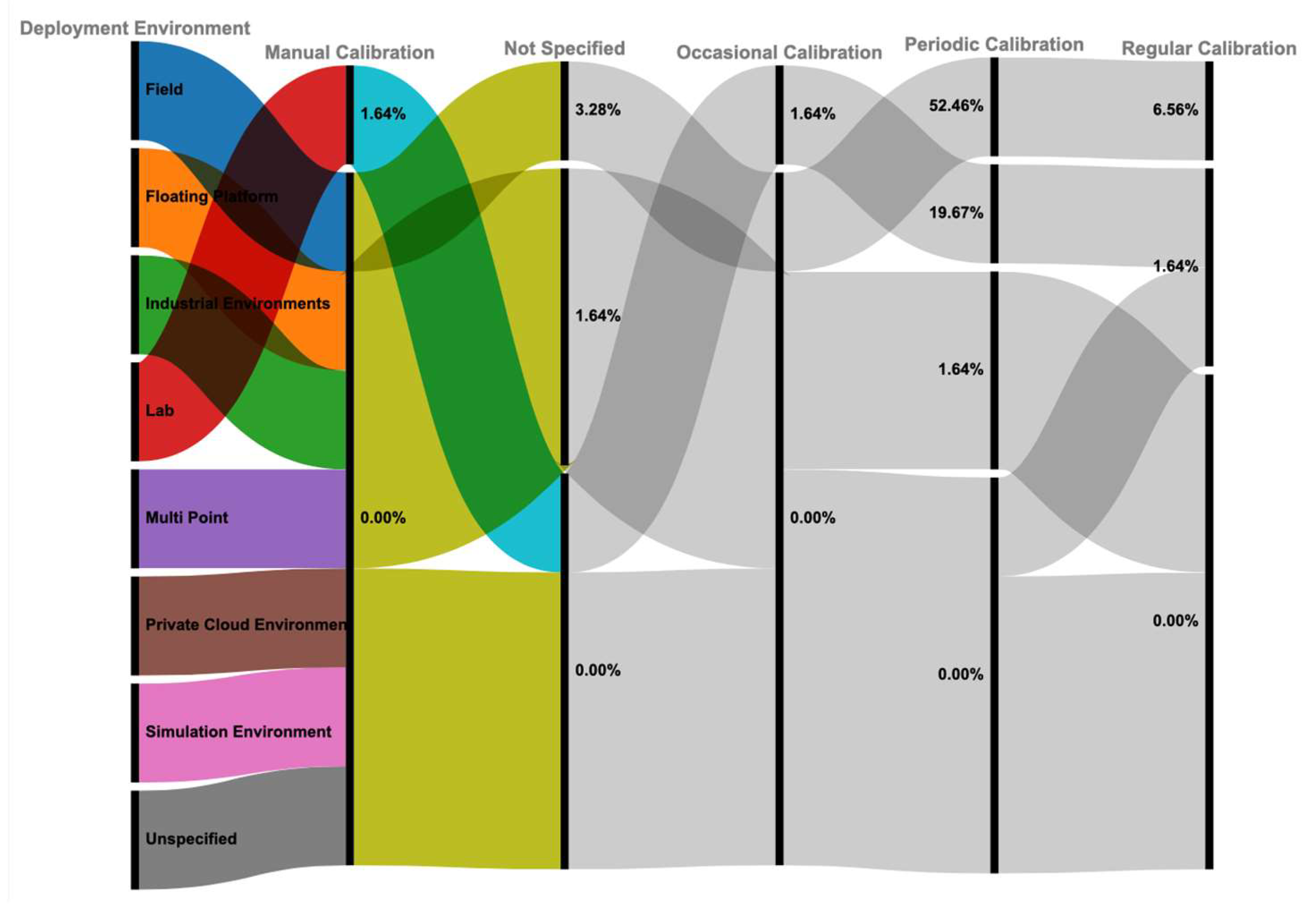

- What are the major technical barriers—including power requirements, data transmission constraints, and maintenance demands—that affect the deployment and operation of IoT sensor networks across various aquatic environments (e.g., rivers, lakes, coastal waters)?

- How can sensor networks be optimized for cost-effectiveness without compromising data accuracy and reliability in large-scale or long-term biological monitoring applications?

- Which machine learning approaches are most effective for interpreting complex, multivariate biological datasets collected via IoT sensor platforms?

- How can advances in edge computing and autonomous sensing systems enhance the scalability and real-time responsiveness of biological monitoring, particularly in remote or resource-constrained aquatic ecosystems?

1.3. Hypotheses Development

- H1: Environmental conditions, such as turbidity and temperature fluctuations, significantly affect the accuracy and reliability of IoT-based biological monitoring systems, necessitating the development of adaptive calibration protocols.

- H2: Multi-sensor configurations deliver more robust environmental monitoring outcomes than single-sensor systems, providing a more comprehensive assessment of aquatic ecosystem dynamics.

- H3: IoT-based monitoring systems that focus primarily on physical parameters improve early detection of environmental shifts but may fall short in capturing broader indicators of biological ecosystem health.

- H4: The integration of advanced sensing technologies—such as biosensors, computer vision, and AI-enhanced platforms—substantially improves the accuracy of biological indicator monitoring, enabling more informed ecological assessments.

- H5: The application of machine learning algorithms to IoT sensor data enhances the detection and prediction of biological anomalies, offering new opportunities for proactive and adaptive aquatic ecosystem management.

- H6: Inconsistencies in sensor calibration, the absence of standardized biological monitoring frameworks, and variability in deployment environments contribute to the underrepresentation of biological-focused IoT applications in the aquatic monitoring literature.

1.4. Rationale

1.4. Objectives

- To evaluate and compare the effectiveness of various IoT sensor technologies—including optical, electrochemical, and biosensors—in measuring key biological indicators such as dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity, and algal blooms across diverse aquatic environments, including rivers, lakes, and coastal waters.

- To analyze deployment patterns and operational challenges associated with IoT sensor networks in different ecological contexts by synthesizing data from global case studies and applied research, with the goal of identifying best practices and recurring implementation barriers.

- To assess emerging technological innovations—such as AI-driven analytics, nanosensors, and autonomous deployment platforms—that enhance the precision, scalability, and cost-efficiency of biological monitoring in aquatic systems.

- To develop practical implementation guidelines tailored for resource-constrained settings, offering evidence-based recommendations for researchers, conservation organizations, and small to medium-sized enterprises involved in aquatic ecosystem monitoring.

1.5. Research Contributions

1.6. Research Novelty

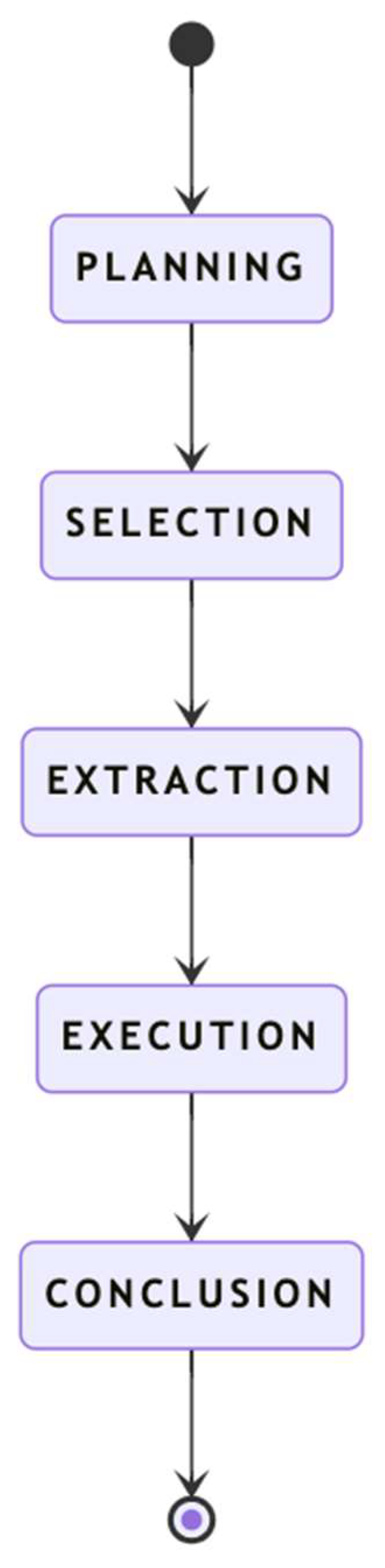

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

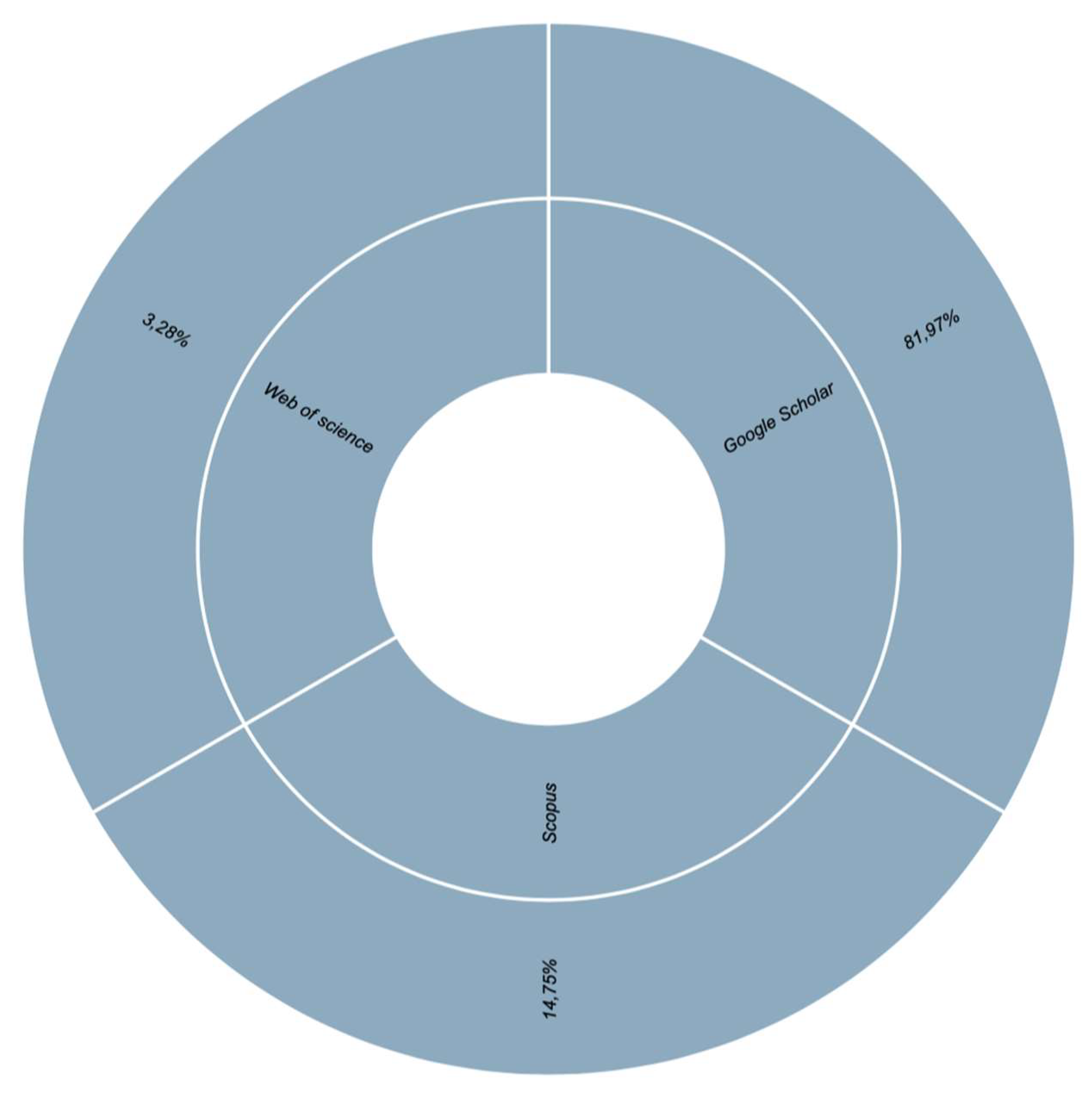

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

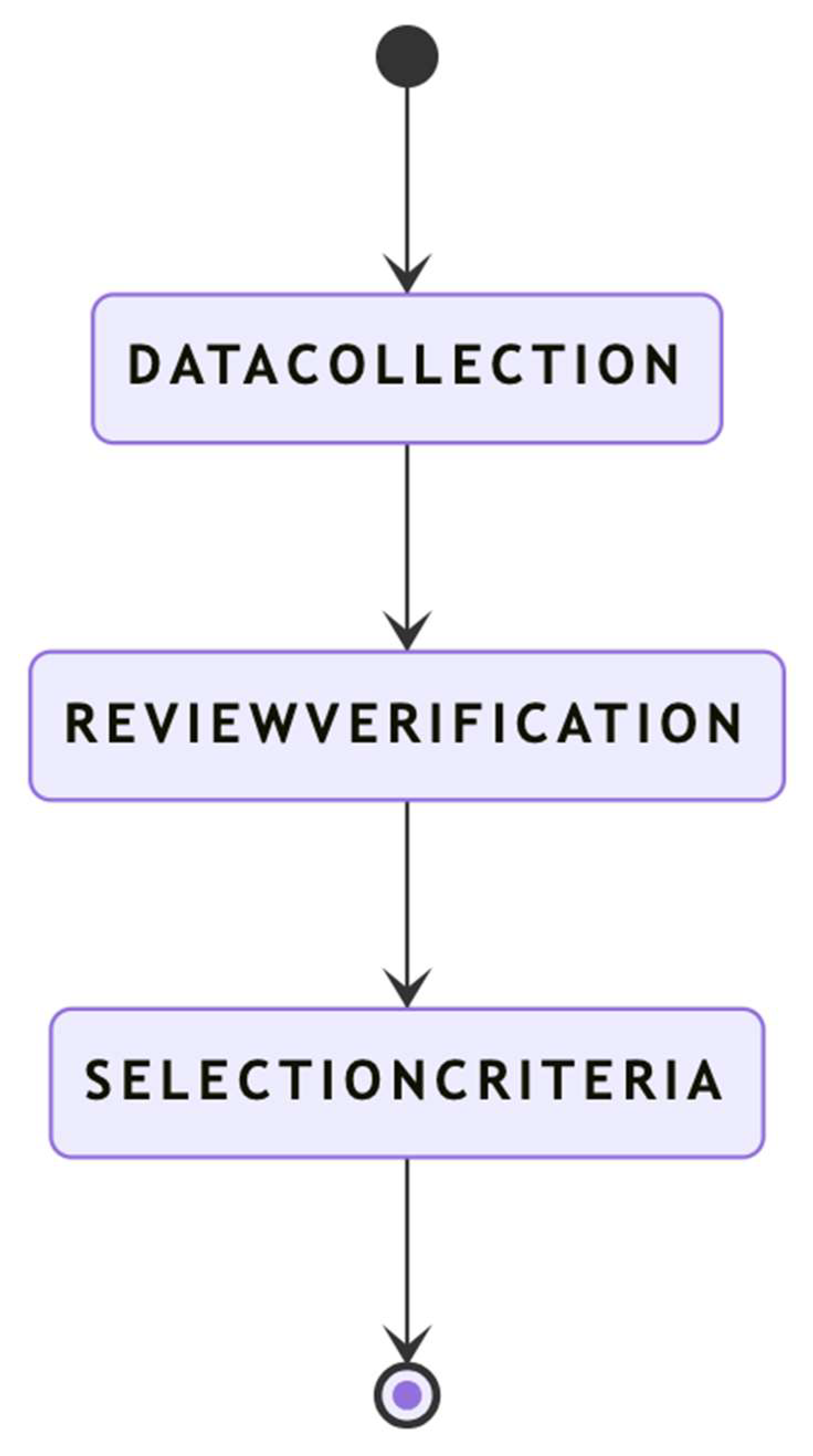

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.6.1. Data Collection Method

2.6.2. Definition of Collected Data Variables

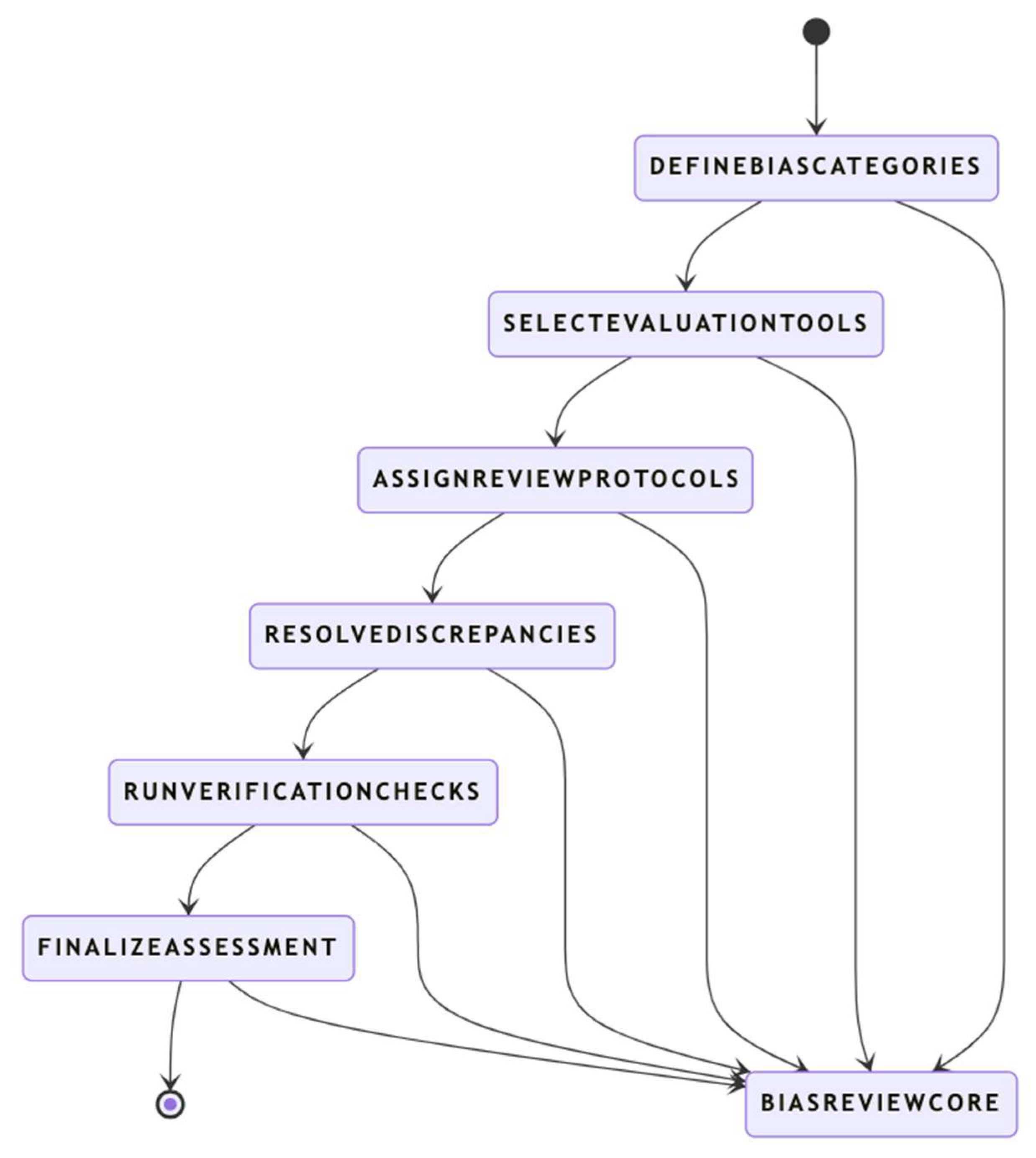

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Effect Measures

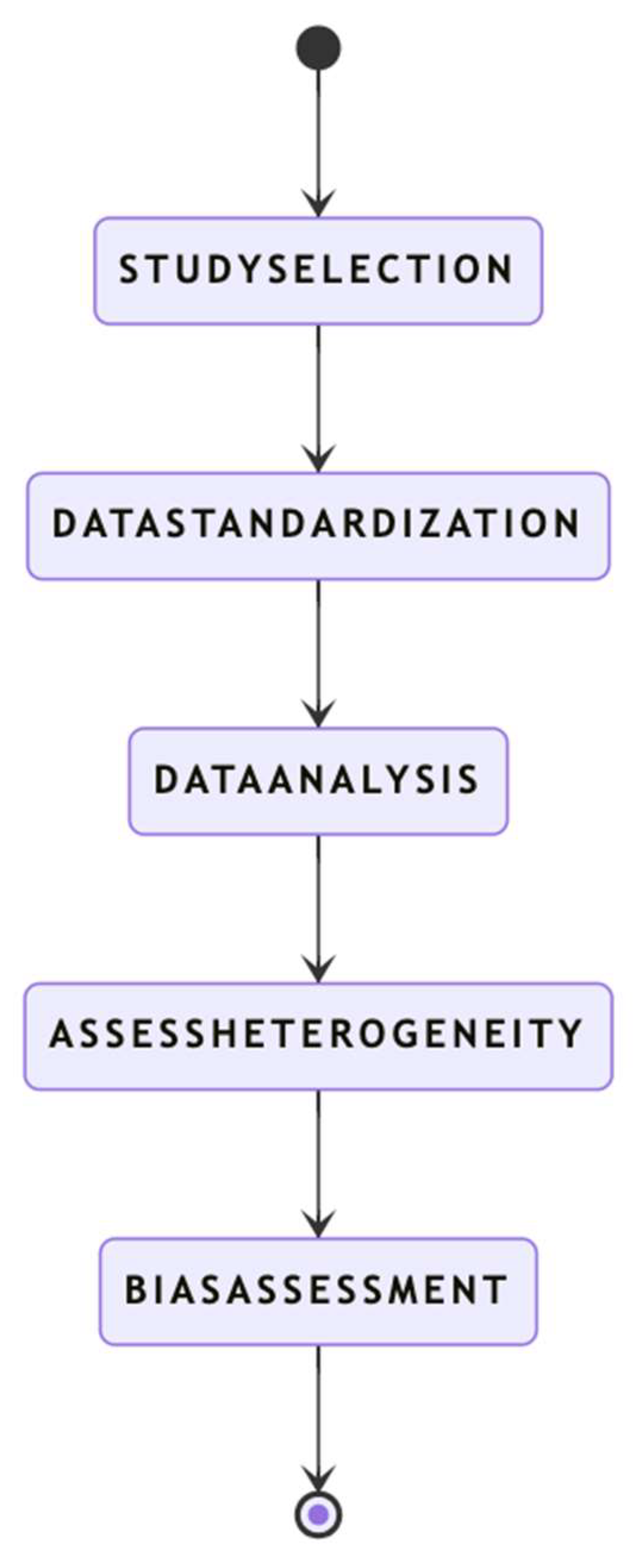

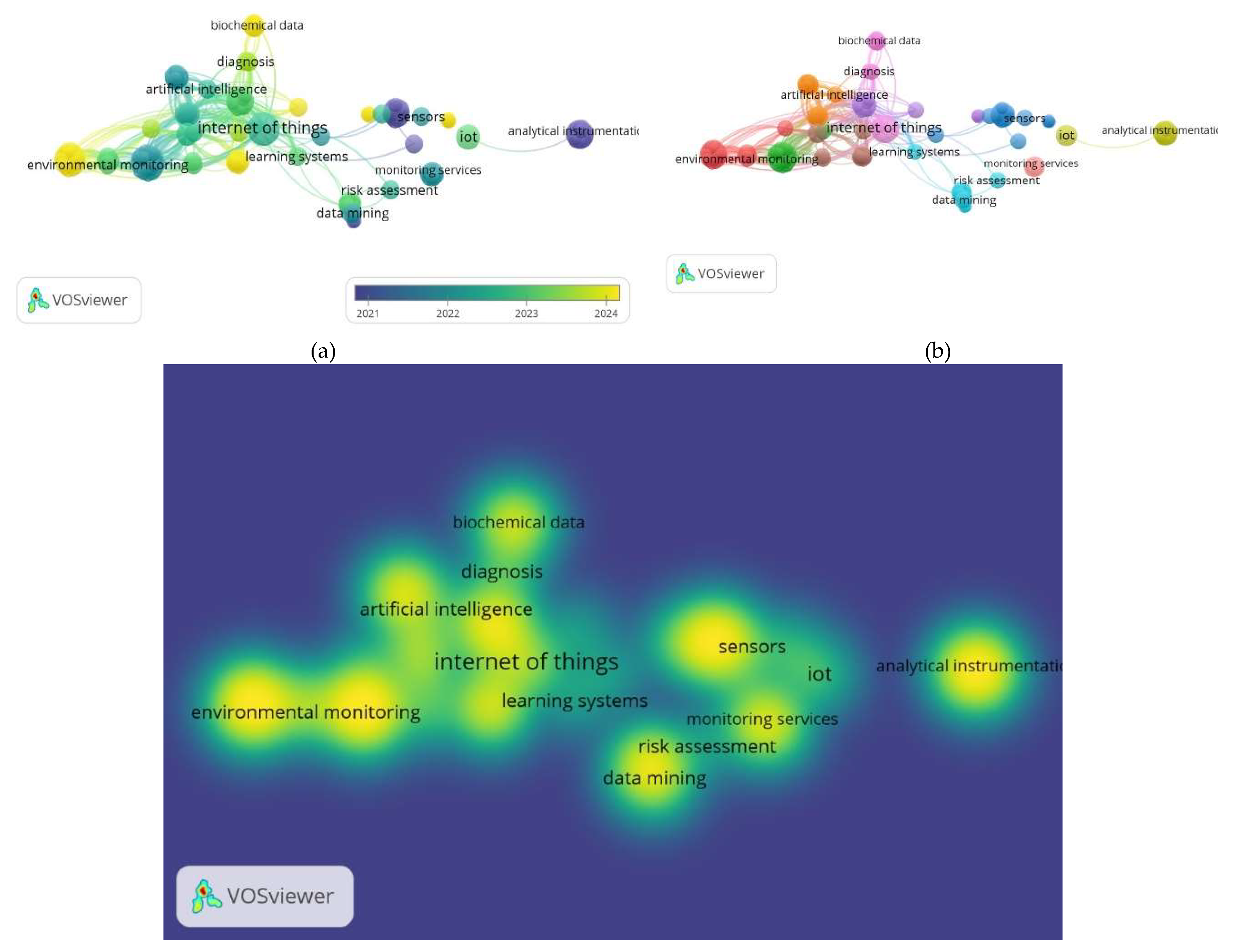

2.9. Synthesis Methods

2.9.1. Eligibility for Synthesis

2.9.2. Data Preparation for Synthesis

2.9.3. Tabulation and Visual Display of Results

2.9.4. Synthesis of Results

2.9.5. Exploring Causes of Heterogeneity

2.9.6. Sensitivity Analyses

2.10. Reporting Bias Assessment

2.11. Certainty Assessment

- QA1: Clarity of research objectives relating to IoT sensor applications.

- QA2: Transparency in data collection, including sensor placement and metrics.

- QA3: Detail in explaining sensor operation and system integration.

- QA4: Appropriateness of the study design for environmental monitoring.

- QA5: Contribution to the broader understanding and advancement of IoT for aquatic monitoring.

- 0 = not met

- 0.5 = partially met

- 1 = fully met

3. Results

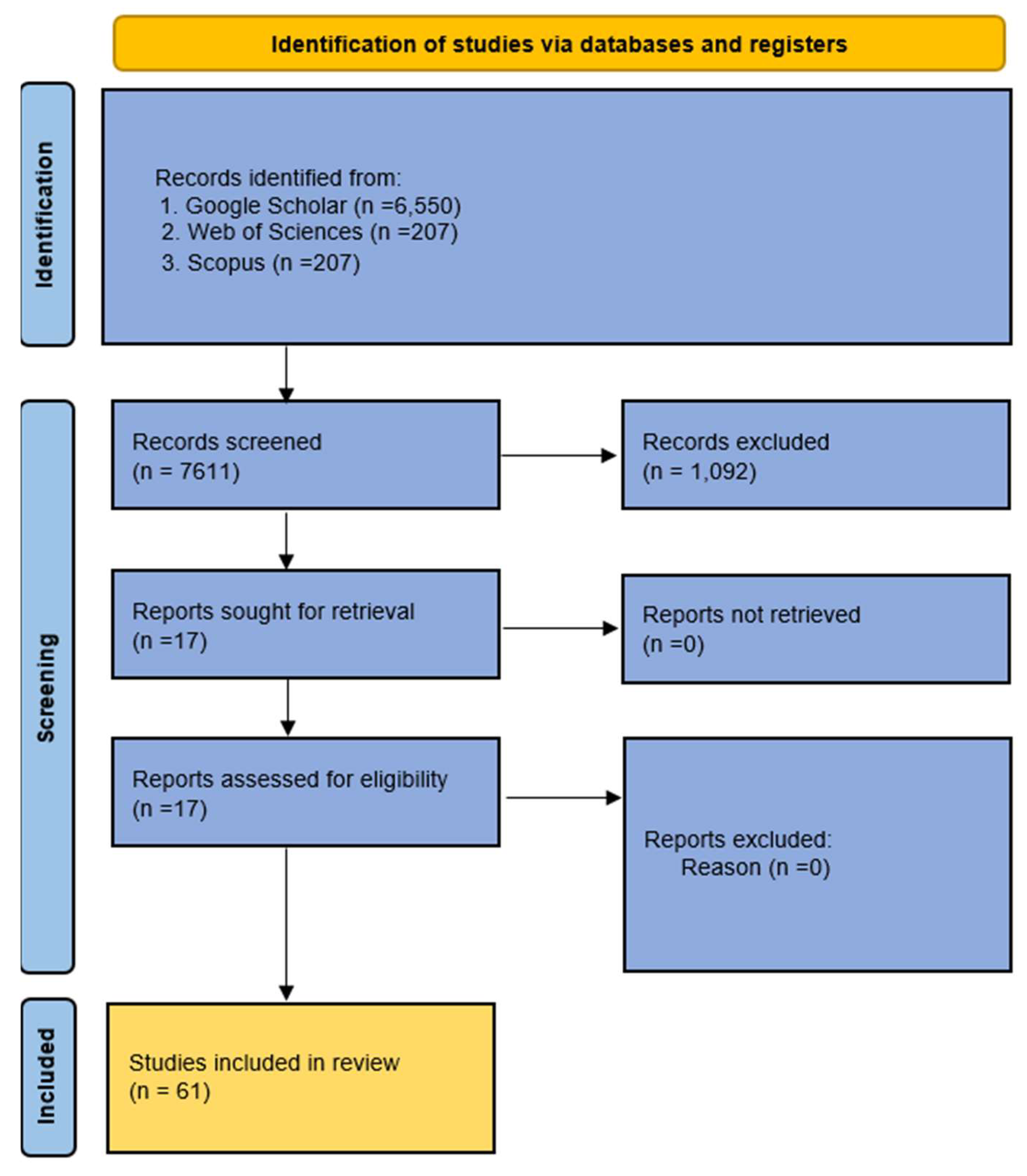

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

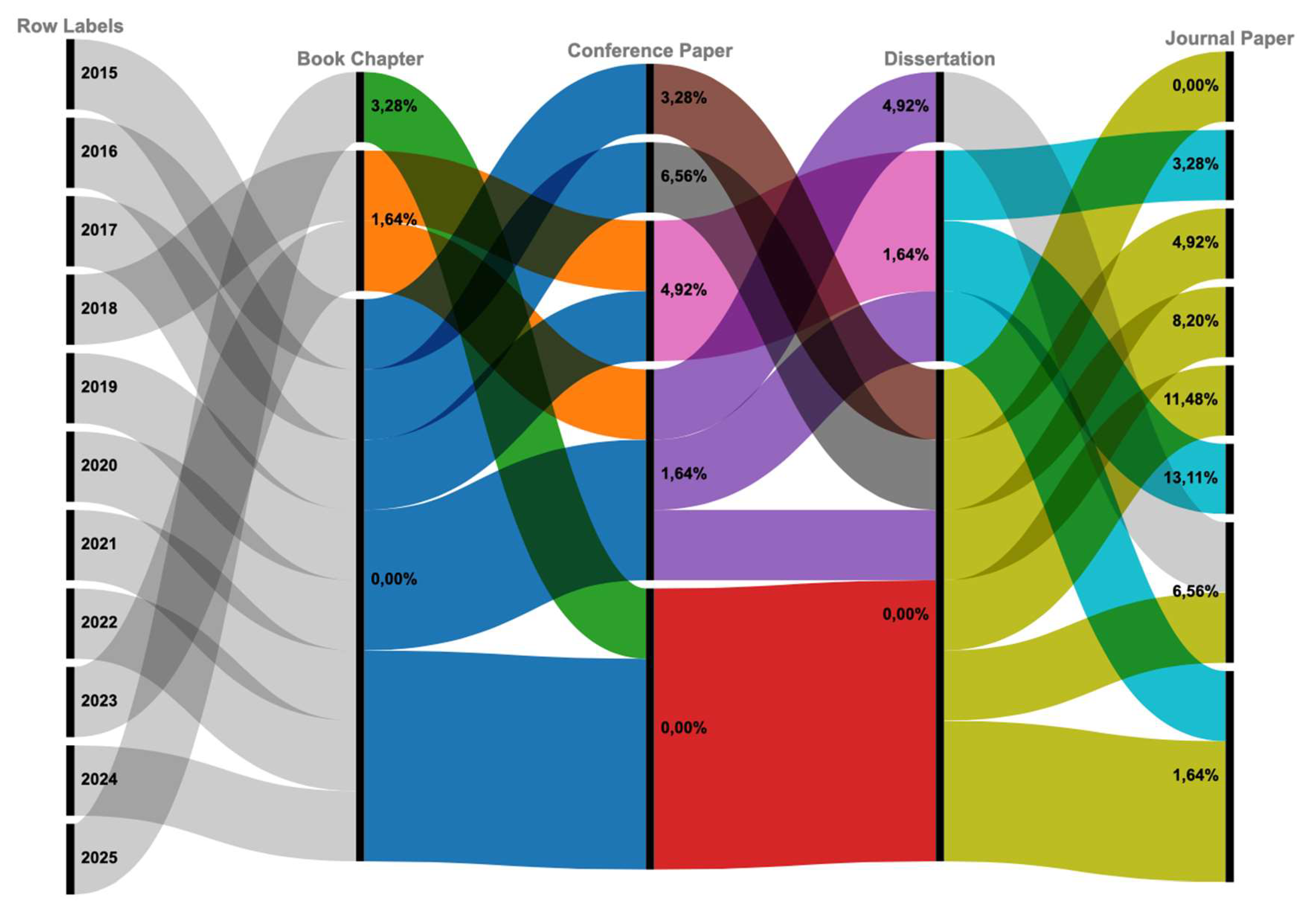

- Journal Articles: 36 studies (59.02%)

- Conference Papers: 15 studies (24.59%)

- Dissertations: 6 studies (9.84%)

- Book Chapters: 4 studies (6.56%)

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

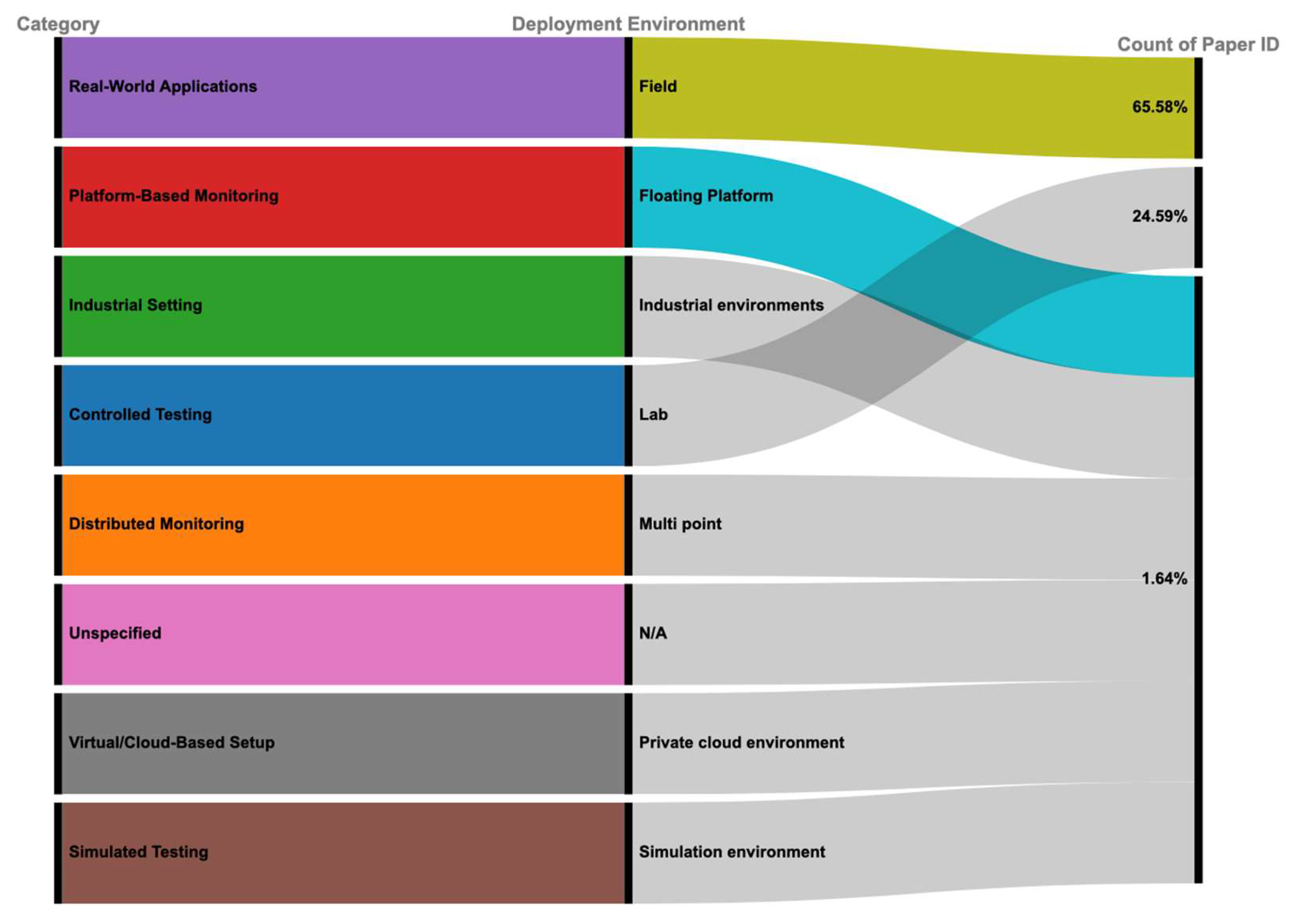

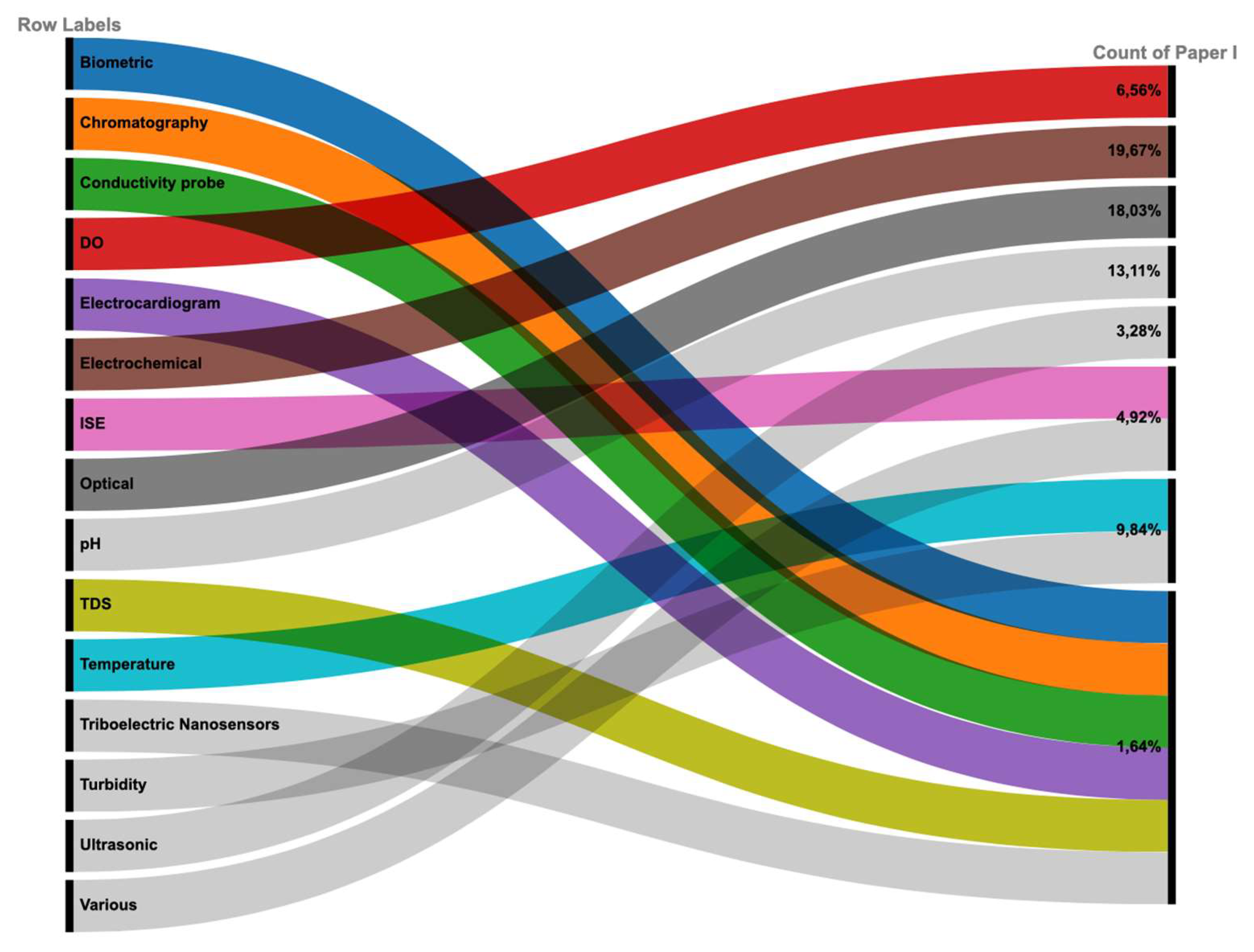

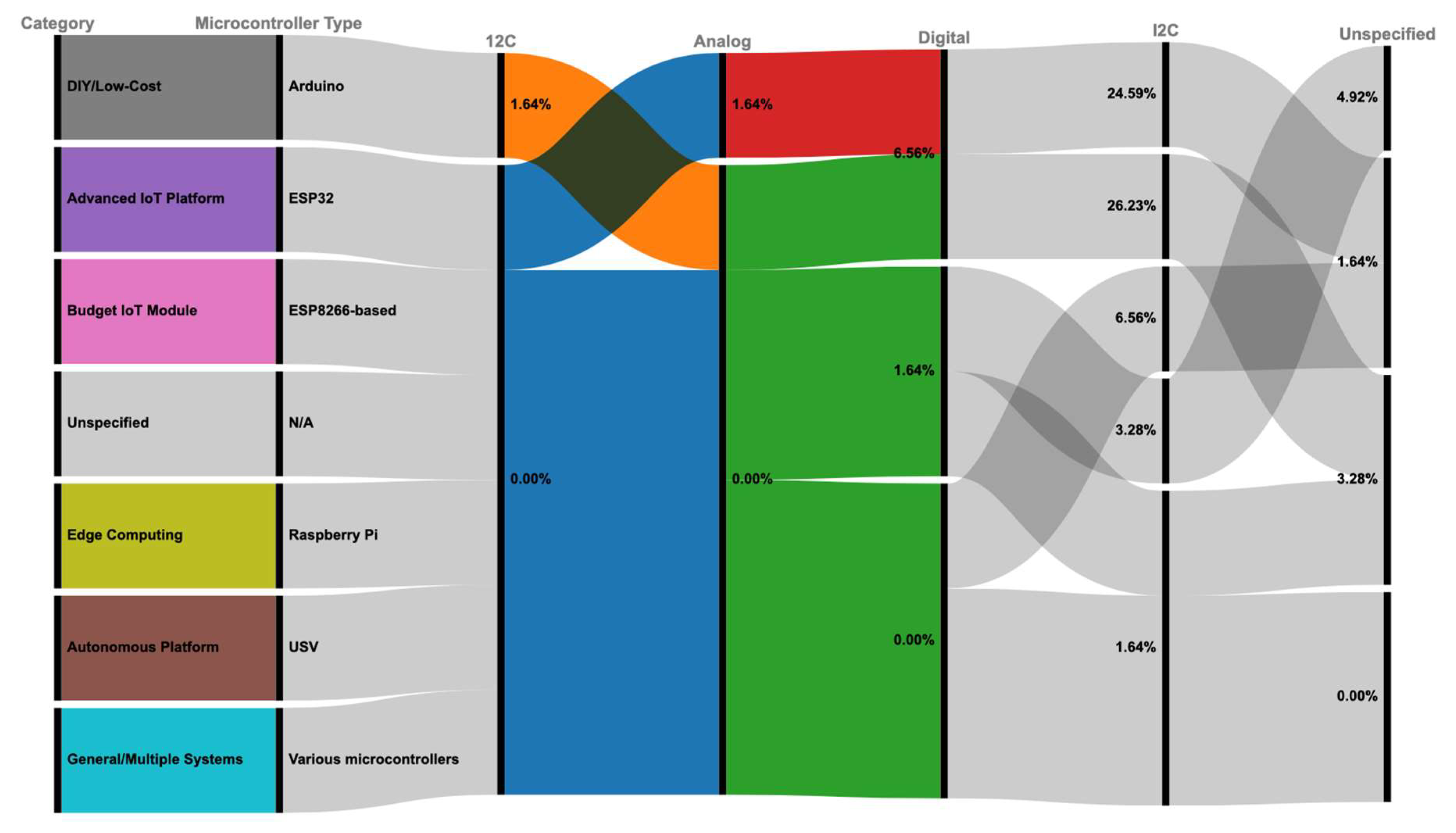

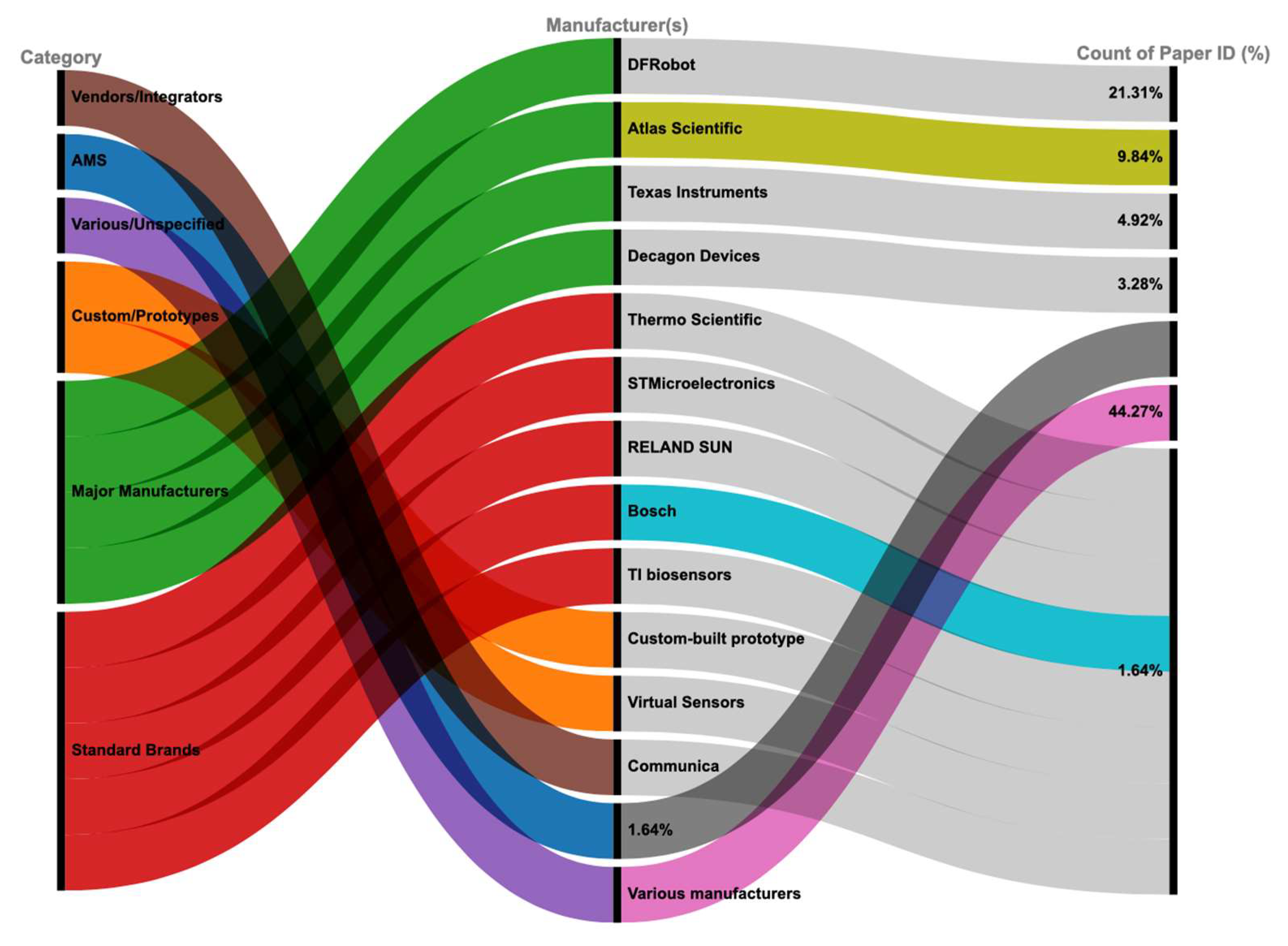

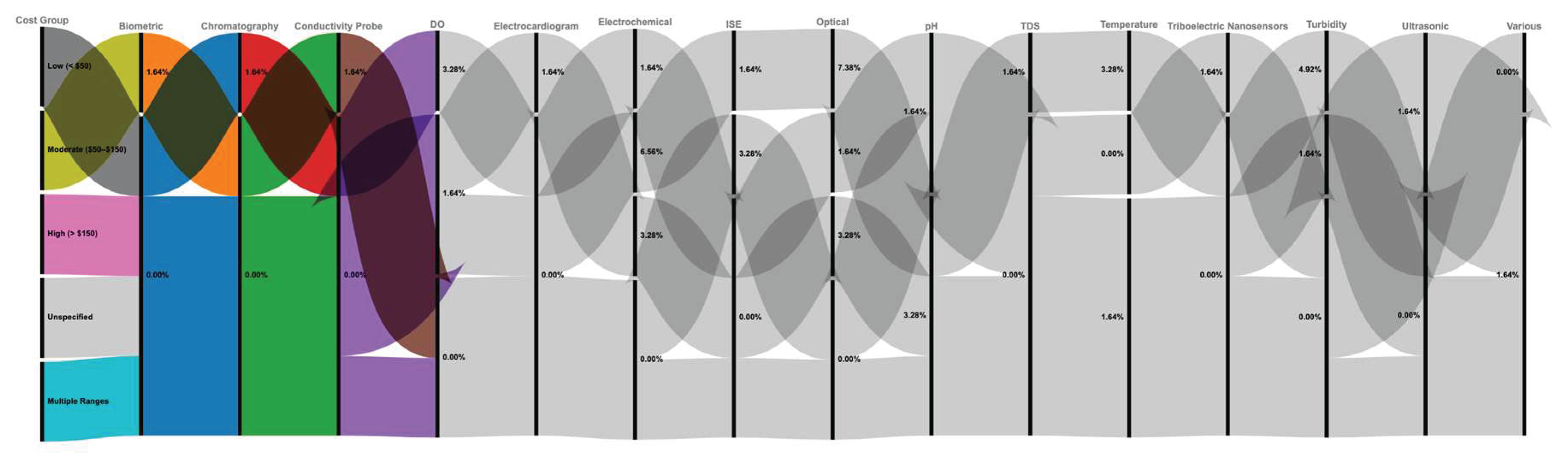

3.5. Results of Synthesis

3.5.1. Characteristics and Risk of Bias Among Contributing Studies

3.5.2. Results of Statistical Syntheses

3.5.3. Investigation of Heterogeneity

3.5.4. Sensitivity Analyses Results

3.6. Reporting Biases

3.7. Certainty of Evidence

- Ecosystem type (e.g., rivers, lakes, coastal zones)

- Geographic region (based on country of origin)

- Sensor integration strategies (e.g., cloud-based analytics, real-time transmission)

5. Conclusion

Appendix A

| Ref | Year of Publication | Sensor Type (ISE, Optical, DO, pH, etc.) | Target Parameter Measured | Interface Type (Analog, Digital, I2C, Modbus) | Microcontroller Compatibility | Deployment Environment (Lab, Field, Submersible, etc.) | Known Challenges (Fouling, Drift, Interference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Perumal et al., 2015) | 2015 | Ultrasonic | DO | Arduino | Field | N/A | |

| (Koo et al., 2015) | 2015 | pH | pH | N/A | Various microcontrollers | Field | N/A |

| (Sheng et al., 2015) | 2015 | Various | Temperature | Digital | N/A | Industrial environments | Energy constraints |

| (Popović et al., 2016) | 2016 | Various | Humidity | Digital | Various microcontrollers | Private cloud environment | Accuracy |

| (Habibzadeh et al., 2017) | 2017 | Temperature | Temperature | Digital | ESP32 | Field | High Power Ussage |

| (Bragg, 2017) | 2017 | Temperature | Temperature | Digital | ESP32 | Field | High Power Ussage |

| (Wu et al., 2017) | 2017 | Various | COD | N/A | ESP32 | N/A | N/A |

| (Yadav et al., 2017) | 2017 | pH | pH | N/A | ESP32 | Lab | Drift |

| (Saha et al., 2017) | 2017 | Electrocardiogram | ECG signals | Analog | Various microcontrollers | Lab | Reliability |

| (Singh & Jasuja, 2017) | 2018 | Biometric | Physiological parameters | Digital | Arduino | Field | Accuracy |

| (Bárta et al., 2018) | 2018 | Electrochemical | pH | Digital | Arduino | Field | Humic buildup |

| (Pearce, 2018) | 2018 | pH | COD | Digital | Arduino | Field | Drift |

| (Pattanayak et al., 2020) | 2018 | pH | Temperature | Digital | Arduino | Lab | Fouling |

| (Kumar & Aravindh, 2020) | 2018 | Temperature | Temperature | Digital | ESP32 | Simulation environment | N/A |

| (Cennamo et al., 2020) | 2018 | Electrochemical | Turbidity | DIgital | Arduino | Field | Environmental Intereferences |

| (Memon et al., 2020) | 2018 | Optical | Microplastics | DIgital | Raspberry Pi | Field | Sensor Drift |

| (Gambín et al., 2021) | 2019 | Turbidity | Algal biomass collection | Digital | ESP32 | Field | Limiations |

| (Trevathan et al., 2021) | 2020 | Conductivity probe | Heavy metals | Analog | ESP32 | Field | Interference |

| (Hong et al., 2021) | 2020 | Chromatography | Nitrate Concentrations | Digital | ESP32 | Field | High Power Ussage |

| (Wang et al., 2021) | 2020 | Electrochemical | Chlorophyll-a | Digital | ESP32 | Field | Humic buildup |

| (Chen et al., 2022) | 2020 | Electrochemical | pH | Digital | Arduino | Field | Reliability |

| (Okpara et al., 2022) | 2020 | Temperature | pH | Digital | Arduino | Field | Fouling |

| (Mezni et al., 2022) | 2020 | Optical | Proteins | Digital | Arduino | Lab | Humic buildup |

| (Tsai et al., 2022) | 2020 | pH | pH | Digital | Arduino | Lab | High Power Ussage |

| (Singh et al., 2022) | 2021 | Electrochemical | pH | Digital | USV | Field | Environmental Interferences |

| (Anani et al., 2022) | 2021 | pH | pH | Digital | ESP32 | Lab | Drift |

| (Swartz et al., 2023) | 2021 | Turbidity | Turbidity | Digital | ESP32 | Field | Reliability |

| (Islam et al., 2023) | 2021 | pH | pH | Analog | Arduino | Field | Accuracy |

| (Zukeram et al., 2023) | 2021 | Electrochemical | pH | DIgital | Arduino | Field | manual data collection |

| (Ighalo et al., 2021) | 2022 | Turbidity | TDS | Analog | ESP8266-based | Field | Sensor limitation |

| (Dhinakaran et al., 2023) | 2022 | Optical | pH | Digital | Arduino | Field | Power limitations |

| (Abuzeid et al., 2023) | 2022 | ISE | Temperature | Analog | Arduino | Lab | Power limitations |

| (Sugiharto et al., 2024) | 2022 | pH | pH | Analog | ESP32 | Field | Low bandwidth |

| (Monea, 2024) | 2022 | Temperature | Temperature | Analog | Arduino | Field | Accuracy |

| (Kim et al., 2024) | 2022 | ISE | DO | Digital | ESP32 | Lab | Drift |

| (Aira et al., 2022) | 2022 | DO | DO | 12C | ESP32 | Lab | Fouling |

| (Olanubi et al., 2024) | 2023 | Electrochemical | Temperature | Digital | Arduino | Multi point | Sensor Drift |

| (Izah, 2025) | 2023 | Electrochemical | Conductivity | Digital | Arduino | Field | Environmnetal Interferences |

| (Das et al., 2025) | 2023 | Electrochemical | DO | Digital | ESP32 | Field | Sensor Drift |

| (Arepalli & Naik, 2025) | 2023 | Optical | BOD | N/A | N/A | Field | Interference |

| (Anupama et al., 2020) | 2023 | Optical | pH | Digital | ESP32 | Field | Sensor Drift |

| (Krishnan & Giwa, 2025) | 2023 | DO | DO | DIgital | Raspberry Pi | Field | Humic buildup |

| (Dubey et al., 2025) | 2023 | DO | Conductivity | I2C | Arduino | Field | Fouling |

| (Vasudevan & Baskaran, 2021) | 2023 | Optical | Turbidity | Digital | Arduino | Field | Interference |

| (Zulkarnain & Pramudita, 2022) | 2023 | Ultrasonic | Humidity | Analog | ESP32 | Field | Instability |

| (Lal et al., 2024) | 2023 | electrochemical | pH | Digital | Raspberry Pi | Lab | Fouling |

| (Gallemit, 2023) | 2023 | Optical | Temperature | Analog | Arduino | Field | Sensor Drift |

| (Chen et al., 2023) | 2024 | TDS | N/A | DIgital | ESP8266-based | Floating Platform | Sensor Drift |

| (Kumar et al., 2024) | 2024 | Optical | DO | Digital | ESP32 | Field | Environmental Intereferences |

| (Hemdan et al., 2023) | 2024 | ISE | pH | Digital | ESP32 | Lab | Interference |

| (Singh et al., 2016) | 2024 | DO | BOD | N/A | N/A | Field | Interference |

| (Chaczko et al., 2018) | 2024 | Optical | BOD | I2C | Raspberry Pi | Field | Humic buildup |

| (Sugiharto et al., 2023) | 2024 | Optical | Glyphosate in water | Digital | ESP32 | Lab | Sensor alignment |

| (Pandey et al., 2024) | 2024 | Optical | pH | Analog | ESP32 | Lab | Instability |

| (Hong et al., 2021) | 2024 | Electrochemical | Temperature | Digital | ESP32 | Field | integration complexities |

| (Perumal et al., 2015) | 2025 | Temperature | Temperature | N/A | Various microcontrollers | Field | Privacy |

| (Koo et al., 2015) | 2025 | Electrochemical | BOD | Digital | Various microcontrollers | Field | Drift |

| (Sheng et al., 2015) | 2025 | Turbidity | Turbidity | N/A | Various microcontrollers | Field | Drift |

| (Popović et al., 2016) | 2025 | Turbidity | Turbidity | Digital | Raspberry Pi | Field | Limitation |

| (Habibzadeh et al., 2017) | 2025 | Triboelectric Nanosensors | Various parameters | Digital | ESP32 | Lab | Humic buildup |

| (Bragg, 2017) | 2025 | Turbidity | Turbidity | Digital | Arduino | Lab | Noise |

References

- Manoj M., Dhilip Kumar, V., Arif, M., Bulai, E. R., Bulai, P., & Geman, O. (2022). State of the art techniques for water quality monitoring systems for fish ponds using iot and underwater sensors: A review. Sensors, 22(6), 2088. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/22/6/2088. [CrossRef]

- Ya’acob, N., Dzulkefli, N. N. S. N., Yusof, A. L., Kassim, M., Naim, N. F., & Aris, S. S. M. (2021, August). Water quality monitoring system for fisheries using internet of things (iot). In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1176, No. 1, p. 012016). IOP Publishing. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/1176/1/012016/meta.

- Lee, K. H., Noh, J., & Khim, J. S. (2020). The Blue Economy and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: Challenges and opportunities. Environment international, 137, 105528. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412019338255.

- Nellemann, C., & Corcoran, E. (Eds.). (2010). Dead planet, living planet: Biodiversity and ecosystem restoration for sustainable development: A rapid response assessment. UNEP/Earthprint. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=irLBX3nBEQC&oi=fnd&pg=PA97&dq=State+of+the+world%27s+aquatic+ecosystems:+Urgent+interventions+for+sustainability&ots=Vdh99AHzi&sig=LnvAIZGIZypaT_8Ra38K09S9dwA.

- Jan, F., Min-Allah, N., & Düştegör, D. (2021). Iot based smart water quality monitoring: Recent techniques, trends and challenges for domestic applications. Water, 13(13), 1729. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/13/13/1729. [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, C. Z., Garfan, S., Talal, M., Alamoodi, A. H., Alamleh, A., Ahmaro, I. Y.,... & Chiang, H. H. (2022). IoT-based water monitoring systems: a systematic review. Water, 14(22), 3621. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/14/22/3621.

- Huang, Y. P., & Khabusi, S. P. (2025). Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) Advances in Aquaculture: A Review. Processes, 13(1), 73. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9717/13/1/73.

- Kaur, R., Mandal, A., & Pandey, A. (2022). Novel approaches in detection and monitoring of aquatic pollution: a review. Journal of Experimental Zoology India, 25(1). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abhed-Pandey/publication/358233738_NOVEL_APPROACHES_IN_DETECTION_AND_MONITORING_OF_AQUATIC_POLLUTION_A_REVIEW/links/6444c4b78ac1946c7a450b86/NOVEL-APPROACHES-IN-DETECTION-AND-MONITORING-OF-AQUATIC-POLLUTION-A-REVIEW.pdf.

- Gholizadeh, M. H., Melesse, A. M., & Reddi, L. (2016). A comprehensive review on water quality parameters estimation using remote sensing techniques. Sensors, 16(8), 1298. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/16/8/1298.

- Dhinakaran, D., Gopalakrishnan, S., Manigandan, M. D., & Anish, T. P. (2023). IoT-Based Environmental Control System for Fish Farms with Sensor Integration and Machine Learning Decision Support. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.04258. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.04258.

- Zainurin, S. N., Wan Ismail, W. Z., Mahamud, S. N. I., Ismail, I., Jamaludin, J., Ariffin, K. N. Z., & Wan Ahmad Kamil, W. M. (2022). Advancements in monitoring water quality based on various sensing methods: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14080. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/21/14080. [CrossRef]

- Essamlali, I., Nhaila, H., & El Khaili, M. (2024). Advances in machine learning and IoT for water quality monitoring: A comprehensive review. Heliyon. https://www.cell.com/heliyon/fulltext/S2405-8440(24)03951-3.

- Singh, M., & Ahmed, S. (2021). IoT based smart water management systems: A systematic review. Materials Today: Proceedings, 46, 5211-5218. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214785320364701.

- Sohrabi, H., Hemmati, A., Majidi, M. R., Eyvazi, S., Jahanban-Esfahlan, A., Baradaran, B.,... & de la Guardia, M. (2021). Recent advances on portable sensing and biosensing assays applied for detection of main chemical and biological pollutant agents in water samples: A critical review. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 143, 116344. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165993621001679.

- Carriazo-Regino, Y., Baena-Navarro, R., Torres-Hoyos, F., Vergara-Villadiego, J., & Roa-Prada, S. (2022). IoT-based drinking water quality measurement: systematic. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 28(1), 405-418. https://www.academia.edu/download/97367402/16718.pdf.

- Ubina, N. A., & Cheng, S. C. (2022). A review of unmanned system technologies with its application to aquaculture farm monitoring and management. Drones, 6(1), 12. https://www.mdpi.com/2504-446X/6/1/12.

- Mandal, A., & Ghosh, A. R. (2024). Role of artificial intelligence (AI) in fish growth and health status monitoring: a review on sustainable aquaculture. Aquaculture International, 32(3), 2791-2820. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10499-023-01297-z. [CrossRef]

- Gladju, J., Kamalam, B. S., & Kanagaraj, A. (2022). Applications of data mining and machine learning framework in aquaculture and fisheries: A review. Smart Agricultural Technology, 2, 100061. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772375522000260.

- Prapti, D. R., Mohamed Shariff, A. R., Che Man, H., Ramli, N. M., Perumal, T., & Shariff, M. (2022). Internet of Things (IoT)-based aquaculture: An overview of IoT application on water quality monitoring. Reviews in Aquaculture, 14(2), 979-992. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/raq.12637.

- Mustapha, U. F., Alhassan, A. W., Jiang, D. N., & Li, G. L. (2021). Sustainable aquaculture development: a review on the roles of cloud computing, internet of things and artificial intelligence (CIA). Reviews in Aquaculture, 13(4), 2076-2091. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jwas.13107.

- Perumal, T., Sulaiman, M. N., & Leong, C. Y. (2015, October). Internet of Things (IoT) enabled water monitoring system. In 2015 IEEE 4th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE) (pp. 86-87). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Koo, D., Piratla, K., & Matthews, C. J. (2015). Towards sustainable water supply: schematic development of big data collection using internet of things (IoT). Procedia engineering, 118, 489-497. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z., Mahapatra, C., Zhu, C., & Leung, V. C. (2015). Recent advances in industrial wireless sensor networks toward efficient management in IoT. IEEE access, 3, 622-637. [CrossRef]

- Popović, T., Radonjić, M., Zečević, Ž., & Krstajić, B. (2016). An IoT cloud solution based on open source tools. In XXI International Scientific-Professional Conference Information Technology. https://shorturl.at/1373w.

- Habibzadeh, H., Qin, Z., Soyata, T., & Kantarci, B. (2017). Large-scale distributed dedicated-and non-dedicated smart city sensing systems. IEEE Sensors Journal, 17(23), 7649-7658. [CrossRef]

- Bragg, G. M. (2017). Standards-based Internet of Things sub-GHz environmental sensor networks (Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton). http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/415864.

- Wu, F., Rudiger, C., & Yuce, M. R. (2017, November). Design and field test of an autonomous IoT WSN platform for environmental monitoring. In 2017 27th International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J., Bhatia, A., Sangeeta, E. J., & Goyal, N. (2017). Internet of Things (IOT): Confronts and Applications. International journal for Research in Applied Science &Engineering Technology, 5(8), 1-6. https://shorturl.at/kHXpY.

- Saha, H. N., Auddy, S., Pal, S., Kumar, S., Jasu, S., Singh, R.,... & Maity, A. (2017, August). Internet of Things (IoT) on bio-technology. In 2017 8th Annual Industrial Automation and Electromechanical Engineering Conference (IEMECON) (pp. 364-369). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P., & Jasuja, A. (2017, May). IoT based low-cost distant patient ECG monitoring system. In 2017 international conference on computing, communication and automation (ICCCA) (pp. 1330-1334). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Bárta, A., Souček, P., Bozhynov, V., Urbanová, P., & Bekkozhayeova, D. (2018). Trends in online biomonitoring. In Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering: 6th International Work-Conference, IWBBIO 2018, Granada, Spain, April 25–27, 2018, Proceedings, Part I 6 (pp. 3-14). Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-78723-7_1.

- Pearce, R. H. (2018). Do-it-yourself”: evaluating the potential of Arduino technology in monitoring water quality. Unpublished Bachelor’s dissertation. doi, 10. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Reagan-Pearce-2/publication/366299404_’Do-it-yourself’_evaluating_the_potential_of_Arduino_technology_in_monitoring_water_quality/links/639b3597095a6a777430641c/Do-it-yourself-evaluating-the-potential-of-Arduino-technology-in-monitoring-water-quality.pdf.

- Pattanayak, A. S., Pattnaik, B. S., Udgata, S. K., & Panda, A. K. (2020). Development of chemical oxygen on demand (COD) soft sensor using edge intelligence. IEEE Sensors Journal, 20(24), 14892-14902. https://shorturl.at/CDARm. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. A., & Aravindh, G. (2020, December). An efficient aquaculture monitoring automatic system for real time applications. In 2020 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS) (pp. 150-153). IEEE.https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85100826603&origin=resultslist&sort=plf-f&src=s&sot=b&sdt=b&cluster=scopubyr%2C%222018%22%2Ct%2C%222019%22%2Ct%2C%222020%22%2Ct&s=%28TITLE-ABS-KEY%28water+AND+quality%29+AND+TITLE-ABS-KEY%28biological%29+AND+TITLE-ABS-KEY%28IOT%29%29&sessionSearchId=208eb5eb8e2060fb88fb6c62fca4a168&relpos=1.

- Cennamo, N., Arcadio, F., Capasso, F., Perri, C., D’Agostino, G., Porto, G.,... & Zeni, L. (2020). Toward smart selective sensors exploiting a novel approach to connect optical fiber biosensors in internet. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 69(10), 8009-8019. https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85100826603&origin=resultslist&sort=plf-f&src=s&sot=b&sdt=b&cluster=scopubyr%2C%222018%22%2Ct%2C%222019%22%2Ct%2C%222020%22%2Ct&s=%28TITLE-ABS-KEY%28water+AND+quality%29+AND+TITLE-ABS-KEY%28biological%29+AND+TITLE-ABS-KEY%28IOT%29%29&sessionSearchId=208eb5eb8e2060fb88fb6c62fca4a168&relpos=1.

- Memon, A. R., Memon, S. K., Memon, A. A., & Memon, T. D. (2020, January). IoT based water quality monitoring system for safe drinking water in Pakistan. In 2020 3rd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET) (pp. 1-7). https://shorturl.at/MsfG5.

- Chabalala, K., Boyana, S., Kolisi, L., Thango, B., & Lerato, M. (2024). Digital technolo-gies and channels for competitive advantage in SMEs: A systematic review. Available at SSRN 4977280.

- Gambín, Á. F., Angelats, E., González, J. S., Miozzo, M., & Dini, P. (2021). Sustainable marine ecosystems: Deep learning for water quality assessment and forecasting. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9525388/.

- Trevathan, J., Schmidtke, S., Read, W., Sharp, T., & Sattar, A. (2021). An IoT general-purpose sensor board for enabling remote aquatic environmental monitoring. Internet of Things, 16, 100429. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542660521000731. [CrossRef]

- Hong, W. J., Shamsuddin, N., Abas, E., Apong, R. A., Masri, Z., Suhaimi, H.,... & Noh, M. N. A. (2021). Water quality monitoring with arduino based sensors. Environments, 8(1), 6. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3298/8/1/6.

- Wang, Y., Ho, I. W. H., Chen, Y., Wang, Y., & Lin, Y. (2021). Real-time water quality monitoring and estimation in AIoT for freshwater biodiversity conservation. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 9(16). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9425517/. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. H., Wu, Y. C., Zhang, J. X., & Chen, Y. H. (2022). IoT-based fish farm water quality monitoring system. Sensors, 22(17), 6700. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/22/17/6700.

- Okpara, E. C., Sehularo, B. E., & Wojuola, O. B. (2022). On-line water quality inspection system: the role of the wireless sensory network. Environmental Research Communications, 4(10), 102001.https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2515-7620/ac9aa5/meta.

- Mezni, H., Driss, M., Boulila, W., Atitallah, S. B., Sellami, M., & Alharbi, N. (2022). Smartwater: A service-oriented and sensor cloud-based framework for smart monitoring of water environments. Remote Sensing, 14(4), 922. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/14/4/922.

- Tsai, K. L., Chen, L. W., Yang, L. J., Shiu, H. J., & Chen, H. W. (2022). IoT based smart aquaculture system with automatic aerating and water quality monitoring. Journal of Internet Technology, 23(1), 177-184. https://jit.ndhu.edu.tw/article/view/2655/0.

- Singh, M., Sahoo, K. S., & Nayyar, A. (2022). Sustainable iot solution for freshwater aquaculture management. IEEE Sensors Journal, 22(16), 16563-16572. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9827934/.

- Anani, O. A., Adetunji, C. O., Olugbemi, O. T., Hefft, D. I., Wilson, N., & Olayinka, A. S. (2022). IoT-based monitoring system for freshwater fish farming: Analysis and design. In AI, Edge and IoT-based Smart Agriculture (pp. 505-515). Academic Press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128236949000268.

- Dladla, V. M. N., & Thango, B. A. (2025). Fault Classification in Power Transformers via Dissolved Gas Analysis and Machine Learning Algorithms: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2395. [CrossRef]

- Swartz, C. D., Wolfaardt, G. M., Lourens, C., Archer, E., Truter, C., Bröcker, L., & Klopper, K. (2023). REAL-TIME SENSING AS ALERT SYSTEM FOR SUBSTANCES OF CONCERN. https://www.wrc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/3103%20final.pdf.

- Islam, M. M., Kashem, M. A., Alyami, S. A., & Moni, M. A. (2023). Monitoring water quality metrics of ponds with IoT sensors and machine learning to predict fish species survival. Microprocessors and microsystems, 102, 104930. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0141933123001746.

- Zukeram, E. S. J., Provensi, L. L., Oliveira, M. V. D., Ruiz, L. B., Lima, O. C. D. M., & Andrade, C. M. G. (2023). In situ IoT development and application for continuous water monitoring in a lentic ecosystem in South Brazil. Water, 15(13), 2310. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/15/13/2310. [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J. O., Adeniyi, A. G., & Marques, G. (2021). Internet of things for water quality monitoring and assessment: a comprehensive review. Artificial intelligence for sustainable development: theory, practice and future applications, 245-259. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/23/2/960.

- Dhinakaran, D., Gopalakrishnan, S., Manigandan, M. D., & Anish, T. P. (2023). IoT-Based Environmental Control System for Fish Farms with Sensor Integration and Machine Learning Decision Support. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.04258. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.04258.

- Abuzeid, H. R., Abdelaal, A. F., Elsharkawy, S., & Ali, G. A. (2023). Basic principles and applications of biological sensors technology. In Handbook of Nanosensors: Materials and Technological Applications (pp. 1-45). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://shorturl.at/dDklV.

- Sugiharto, W. H., Susanto, H., & Prasetijo, A. B. (2024). Selecting IoT-Enabled Water Quality Index Parameters for Smart Environmental Management. Instrumentation, Mesures, Métrologies, 23(4). https://shorturl.at/RqBJs.

- MONEA, E. V. B. Monitoring of surface water quality in the Mureș River Basin. https://cdn.uav.ro/documente/Universitate/Academic/Doctorat/Sustinere/2024/Monea-Blidar/Rezumat-eng-Monea-Elena-Violeta.pdf.

- Kim, E., Nam, S. H., Hwang, T. M., Lee, J., Park, J. B., Shim, I. T.,... & Koo, J. W. (2024). IoT-Based Tryptophan-like Fluorescence Portable Device to Monitor the Indicators for Microbial Quality by E. coli and Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD5). Water, 16(23), 3491. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/16/23/3491. [CrossRef]

- Aira, J., Olivares, T., & Delicado, F. M. (2022). SpectroGLY: A low-cost IoT-based ecosystem for the detection of glyphosate residues in waters. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 71, 1-10. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2401.16009.

- Olanubi, O. O., Akano, T. T., & Asaolu, O. S. (2024). Design and development of an IoT-based intelligent water quality management system for aquaculture. Journal of Electrical Systems and Information Technology, 11(1), 15. https://nesciences.com/article/1491795/72091/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Kgakatsi, M., Galeboe, O. P., Molelekwa, K. K., & Thango, B. A. (2024). The Impact of Big Data on SME Performance: A Systematic Review. Businesses, 4(4), 632-695. [CrossRef]

- Khanyi, M. B., Xaba, S. N., Mlotshwa, N. A., Thango, B., & Matshaka, L. (2024). A Roadmap to Systematic Review: Evaluating the Role of Data Networks and Application Programming Interfaces in Enhancing Operational Efficiency in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability, 16(23), 10192. [CrossRef]

- Chibueze Izah, S. (2025). Smart Technologies in Environmental Monitoring: Enhancing Real-Time Data for Health Management. In Innovative Approaches in Environmental Health Management: Processes, Technologies, and Strategies for a Sustainable Future (pp. 199-224). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-81966-7_8.

- Das, S., Khondakar, K. R., Mazumdar, H., Kaushik, A., & Mishra, Y. K. (2025). AI and IoT: Supported Sixth Generation Sensing for Water Quality Assessment to Empower Sustainable Ecosystems. ACS ES&T Water. [CrossRef]

- Arepalli, P. G., & Naik, K. J. (2025). Water quality classification framework for IoT-enabled aquaculture ponds using deep learning based flexible temporal network model. Earth Science Informatics, 18(2), 351. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12145-025-01857-2. [CrossRef]

- Anupama, K., Rao, Y. C., & Gurrala, V. K. (2020). A machine learning approach to monitor water quality in aquaculture. International Journal of Performability Engineering, 16(12), 1845. https://shorturl.at/hSxc4.

- Krishnan, S., & Giwa, A. (2025). Advances in real-time water quality monitoring using triboelectric nanosensors. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. https://shorturl.at/gcwJo.

- Dubey, S., Dubey, S., & Raghuwanshi, K. (2025). Unlocking IoT and Machine Learning’s Potential for Water Quality Assessment: An Extensive Analysis and Future Directions. Water Conservation Science and Engineering, 10(1), 18. https://shorturl.at/fSexN.

- Molete, O. B., Mokhele, S. E., Ntombela, S. D., & Thango, B. A. (2025). The Impact of IT Strategic Planning Process on SME Performance: A Systematic Review. Businesses, 5(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Msane, M. R., Thango, B. A., & Ogudo, K. A. (2024). Condition Monitoring of Electrical Transformers Using the Internet of Things: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 14(21), 9690. [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S. K., & Baskaran, B. (2021). An improved real-time water quality monitoring embedded system with IoT on unmanned surface vehicle. Ecological Informatics, 65, 101421. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1574954121002120.

- Zulkarnain, G. G., & Pramudita, B. A. (2022, December). Water Pollution Monitoring Systems Several Point Locations Using the Internet of Things. In 2022 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on Wireless and Mobile (APWiMob) (pp. 1-7). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10014098.

- Lal, K., Menon, S., Noble, F., & Arif, K. M. (2024). Low-cost IoT based system for lake water quality monitoring. Plos one, 19(3), e0299089. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0299089.

- Gallemit, A. B. (2023). Water monitoring and analysis system: validating an IoT-enabled prototype towards sustainable aquaculture. Validating an IoT-Enabled Prototype towards Sustainable Aquaculture. https://www.ijams-bbp.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/1-IJAMS-JUNE-2023-496-517.pdf.

- Chen, S. L., Chou, H. S., Huang, C. H., Chen, C. Y., Li, L. Y., Huang, C. H.,... & Huang, J. S. (2023). An intelligent water monitoring IoT system for ecological environment and smart cities. Sensors, 23(20), 8540. https://shorturl.at/e1Qsq.

- Kumar, J., Gupta, R., Sharma, S., Chakrabarti, T., Chakrabarti, P., & Margala, M. (2024). IoT-Enabled Advanced Water Quality Monitoring System for Pond Management and Environmental Conservation. IEEE Access. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10506512.

- Hemdan, E. E. D., Essa, Y. M., Shouman, M., El-Sayed, A., & Moustafa, A. N. (2023). An efficient IoT based smart water quality monitoring system. Multimedia tools and applications, 82(19), 28827-28851. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11042-023-14504-z. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Kumar, A., Prasad, A., & Bharadwaj, N. (2016). IoT based water quality monitoring system. Proceedings of the IRFIC. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s43067-024-00139-z?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Chaczko, Z., Kale, A., Santana-Rodríguez, J. J., & Suárez-Araujo, C. P. (2018, June). Towards an iot based system for detection and monitoring of microplastics in aquatic environments. In 2018 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems (INES) (pp. 000057-000062). IEEE. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0141933123001746?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Thobejane, L. T., & Thango, B. A. (2024). Partial Discharge Source Classification in Power Transformers: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 14(14), 6097. [CrossRef]

- Sugiharto, W. H., Susanto, H., & Prasetijo, A. B. (2023). Real-time water quality assessment via IoT: monitoring pH, TDS, temperature, and turbidity. Ingénierie des Systèmes d’Information, 28(4), 823-831. https://shorturl.at/IjXM8.

- Pandey, V., Mishra, A., Bahuguna, R., Pandey, S., Yamsani, N., & Ahmed, M. M. (2024, May). A Paradigm Shifts in Enhancing Environmental Sustainability: AI and IoT for Smart Water Quality Applications. In 2023 International Conference on Smart Devices (ICSD) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10751381.

- Ngcobo, K., Bhengu, S., Mudau, A., Thango, B., & Lerato, M. (2024). Enterprise data management: Types, sources, and real-time applications to enhance business performance-a systematic review. Systematic Review September.

- Pingilili, A., Letsie, N., Nzimande, G., Thango, B., & Matshaka, L. (2025). Guiding IT Growth and Sustaining Performance in SMEs Through Enterprise Architecture and Information Management: A Systematic Review. Businesses, 5(2), 17. [CrossRef]

- Hong, W. J., Shamsuddin, N., Abas, E., Apong, R. A., Masri, Z., Suhaimi, H.,... & Noh, M. N. A. (2021). Water quality monitoring with arduino based sensors. Environments, 8(1), 6. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3298/8/1/6\.

- Thango, B. A., & Obokoh, L. (2024). Techno-Economic Analysis of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for Power Interruptions: A Systematic Review. Eng, 5(3), 2108-2156. [CrossRef]

- Rostam, N. A. P., Malim, N. H. A. H., Abdullah, R., Ahmad, A. L., Ooi, B. S., & Chan, D. J. C. (2021). A complete proposed framework for coastal water quality monitoring system with algae predictive model. IEEE access, 9, 108249-108265. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9504580/. [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Contributions | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zainurin et al., 2022 | Provides a comprehensive comparison of physical, chemical, and biological sensing technologies, highlighting advances in biosensors and their practical field applications | Strong practical focus; addresses underwater deployment challenges | Primarily analyses chemical parameters; limited biological health tracking |

| Essamlali et al., 2024 | Highlights the synergy between IoT and machine learning for real-time, predictive water quality monitoring with emphasis on automated anomaly detection | Comprehensive coverage of IoT architectures; identifies trends in sensor integration | Broad scope with minimal focus on biological indicators |

| Singh & Ahmed, 2021 | Maps the evolution of smart water management frameworks, showcasing integration of cloud platforms and data analytics in IoT-based monitoring. | Covers diverse sensor types; recent technological trends included | Biological sensing discussed briefly without detailed analysis |

| Sohrabi et al., 2021 | Reviews recent innovations in portable biosensors, focusing on miniaturization and multi-analyte detection for on-site water analysis | Highlights innovative technologies (biosensors, nanotechnology) | Emphasizes pollutant detection over ecological biological indicators |

| Carriazo-Regino,2022 | Emphasizes real-time IoT monitoring of potable water with analysis of sensor accuracy, latency, and communication protocols. | Thorough technical review; focuses on real-time monitoring systems | Drinking water focus limits application to natural aquatic ecosystems |

| Ubina & Cheng, 2022 | Discusses unmanned vehicles for aquaculture data collection, offering insights into mobility, energy efficiency, and deployment scalability | Updates practical deployments; highlights sensor limitations and field conditions | Emphasis remains mainly on physicochemical parameters; limited biological monitoring |

| Mandal & Ghosh, 2024 | Analyses AI-driven techniques for monitoring fish growth and health, highlighting applications of computer vision and machine learning in sustainable aquaculture | Strong focus on predictive analytics; AI/ML integration for better farm management | Mainly addresses aquaculture productivity, not natural ecosystem biodiversity |

| Gladju Kamalam & Kanagaraj, 2022 | Outlines how machine learning and data mining frameworks optimize yield prediction and disease management in aquaculture and fisheries | Reinforces real-time control advantages; discusses system optimization techniques | Narrowly focused on commercial aquaculture; biological ecosystem factors largely omitted |

| Prapti et al., 2022 | Reviews IoT integration for aquaculture water monitoring, exploring sensor deployment models, data transmission, and practical case studies | Details specific case studies and sensor performance evaluations | Limited generalization to wild or unmanaged aquatic ecosystems |

| Mustapha, 2021 | Summarizes various AI methods used in aquaculture, identifying trends and research gaps in automation and system optimization. | Bridges AI and IoT for smarter aquaculture systems; explores intelligent environmental sensing | Targets productivity and operational efficiency; less focus on biological diversity indicators |

| Proposed Review | Synthesizes 61 studies (2015–2025) on IoT sensors for biological indicators. | Covers sensor types, costs, AI integration, and equity gaps. | Focuses on peer-reviewed studies; excludes gray literature. |

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Topic | Studies focusing on the application of IoT sensors for monitoring biological indicators in aquatic ecosystems | Studies not addressing biological monitoring or those focused only on physical/chemical parameters |

| Research Framework | Studies that include a clear methodology for applying IoT sensors to biological monitoring | Studies lacking methodological relevance to IoT-based biological monitoring |

| Language | English-language publications only | Non-English language publications |

| Publication Period | Studies published between 2015 and 2025 | Studies published outside of this date range |

| No. | Online Repository | Number of results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Google Scholar | 6550 |

| 2 | Web of Science | 207 |

| 3 | Scopus | 854 |

| Total | 7611 |

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Study characteristics | Geographic location, type of water body, scope of environmental concern, and research setting urban, rural, industrial. |

| Participant characteristics | Details about IoT technologies used, including sensor types, network protocols, power supply, and deployment models. |

| Intervention characteristics | Information on biological parameters monitored, such as microbial counts, algal concentrations, aquatic biodiversity indices, and oxygen levels. |

| Economic factors | Cost of system implementation, maintenance expenses, data storage infrastructure, and analysis of cost-effectiveness or return on environmental outcomes. |

| External influences | Local environmental policies, pollution control regulations, climate conditions, and external stressors impacting water quality and system performance. |

| Ref. | QA1 | QA2 | QA3 | QA4 | QA5 | Total | % grading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Anani et al., 2022), (Koo et al., 2015), (Vasudevan & Baskaran, 2021), (Habibzadeh et al., 2017), (Trevathan et al., 2021) | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 50 |

| (Bárta et al., 2018), (Wang et al., 2021), (Saha et al., 2017), (Chaczko et al., 2018) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 3 | 60 |

| (Sheng et al., 2015), (Pattanayak et al., 2020), (Izah, 2025), (Hong et al., 2021), (Zulkarnain & Pramudita, 2022), (Wu et al., 2017), (Memon et al., 2020), (Yadav et al., 2017), (Mezni et al., 2022), (Swartz et al., 2023) | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 70 |

| (Das et al., 2025), (Popović et al., 2016), (Okpara et al., 2022), (Zukeram et al., 2023), (Lal et al., 2024), (Sugiharto et al., 2023), (Pearce, 2018), (Chen et al., 2022), (Dhinakaran et al., 2023), (Dubey et al., 2025), (Bragg, 2017), (Gambín et al., 2021), (Abuzeid et al., 2023), (Krishnan & Giwa, 2025), (Singh & Jasuja, 2017), (Perumal et al., 2015), (Anupama et al., 2020), (Tsai et al., 2022) | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 80 |

| (Monea, 2024), (Singh et al., 2016) , (Kumar & Aravindh, 2020), (Cennamo et al., 2020), (Hong et al., 2021), (Hemdan et al., 2023), (Pandey et al., 2024), (Kumar et al., 2024), (Islam et al., 2023), (Kim et al., 2024) , (Singh et al., 2022), (Olanubi et al., 2024), (Arepalli & Naik, 2025), (Chen et al., 2023), (Aira et al., 2022), (Zulkarnain & Pramudita, 2022) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 90 |

| (Sugiharto et al., 2024), (Ighalo et al., 2021), (Gallemit, 2023), (Sugiharto et al., 2023), Lal et al., 2024) , (Chaczko et al., 2018), (Vasudevan & Baskaran, 2021), (Singh et al., 2016), (Koo et al., 2015), (Memon et al., 2020), (Swartz et al., 2023), (Habibzadeh et al., 2017), (Wu et al., 2017), (Zukeram et al., 2023) (Cennamo et al., 2020), (Bárta et al., 2018), (Hong et al., 2021), (Krishnan & Giwa, 2025), (Mezni et al., 2022), (Pearce, 2018), (Gambín et al., 2021), (Chen et al., 2022), (Zulkarnain & Pramudita, 2022), (Perumal et al., 2015), (Das et al., 2025), (Olanubi et al., 2024), (Tsai et al., 2022), (Sheng et al., 2015), (Bragg, 2017), (Popović et al., 2016), (Singh & Jasuja, 2017), (Hong et al., 2021), (Anupama et al., 2020), (Saha et al., 2017), (Pattanayak et al., 2020), (Monea, 2024), (Kim et al., 2024) |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 100 |

| Outcome | Certainty of Evidence | Effect Estimate | Interpretation |

| Cost-effectiveness of IoT sensors | Low | 25% cost savings with moderate-accuracy sensors | High-accuracy increases cost; moderate sensors save costs |

| Accuracy of biological indicator detection | Moderate | 20–30% improvement over manual methods | Enhances monitoring precision |

| Sensor reliability in aquatic environments | Low | 15% performance drop in turbid/saline waters | Environmental interference requires robust sensor design |

| Data transmission efficiency | Moderate | 85–90% success over 1–5 km | Reliable for mid-range aquatic deployments |

| Range of biological indicators monitored | High | 5+ indicators monitored | Supports comprehensive ecosystem health assessments |

| Ease of deployment & maintenance | Moderate | 40% deployment time reduction; maintenance every 2–3 months | Improved usability in fieldwork |

| Integration with analytics platforms | Moderate | 70% of studies use cloud/edge analytics | Enables real-time data analysis and management |

| Applicability across aquatic ecosystems | High | Deployed in 6+ countries across lakes, rivers, coasts | Demonstrates scalability and relevance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).