Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Main

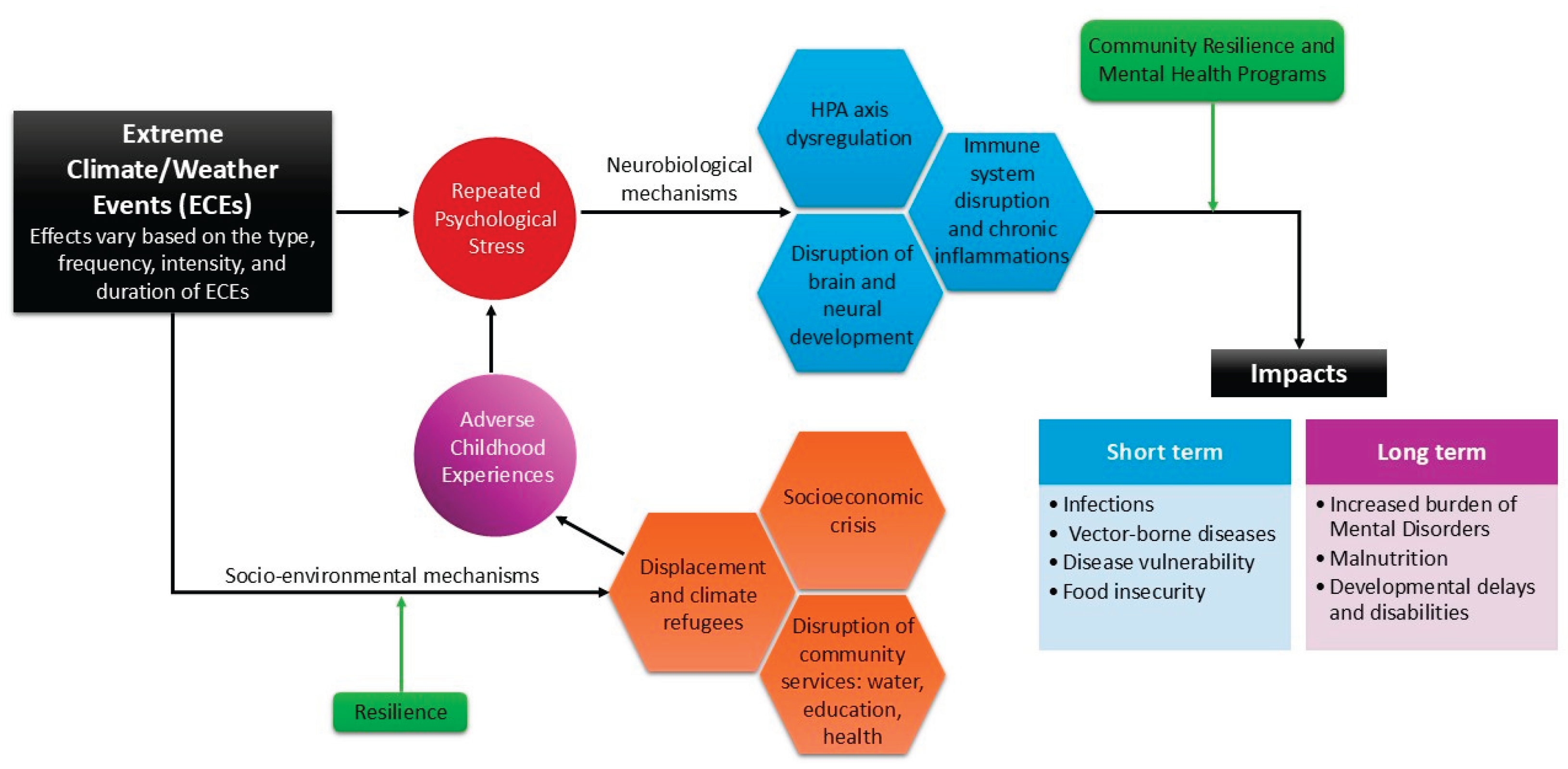

Conceptualising Environmentally Driven Adverse Childhood Experiences (E-ACEs)

E-ACEs Representing a Distinct and Growing Subclass Within the TRACEs Framework

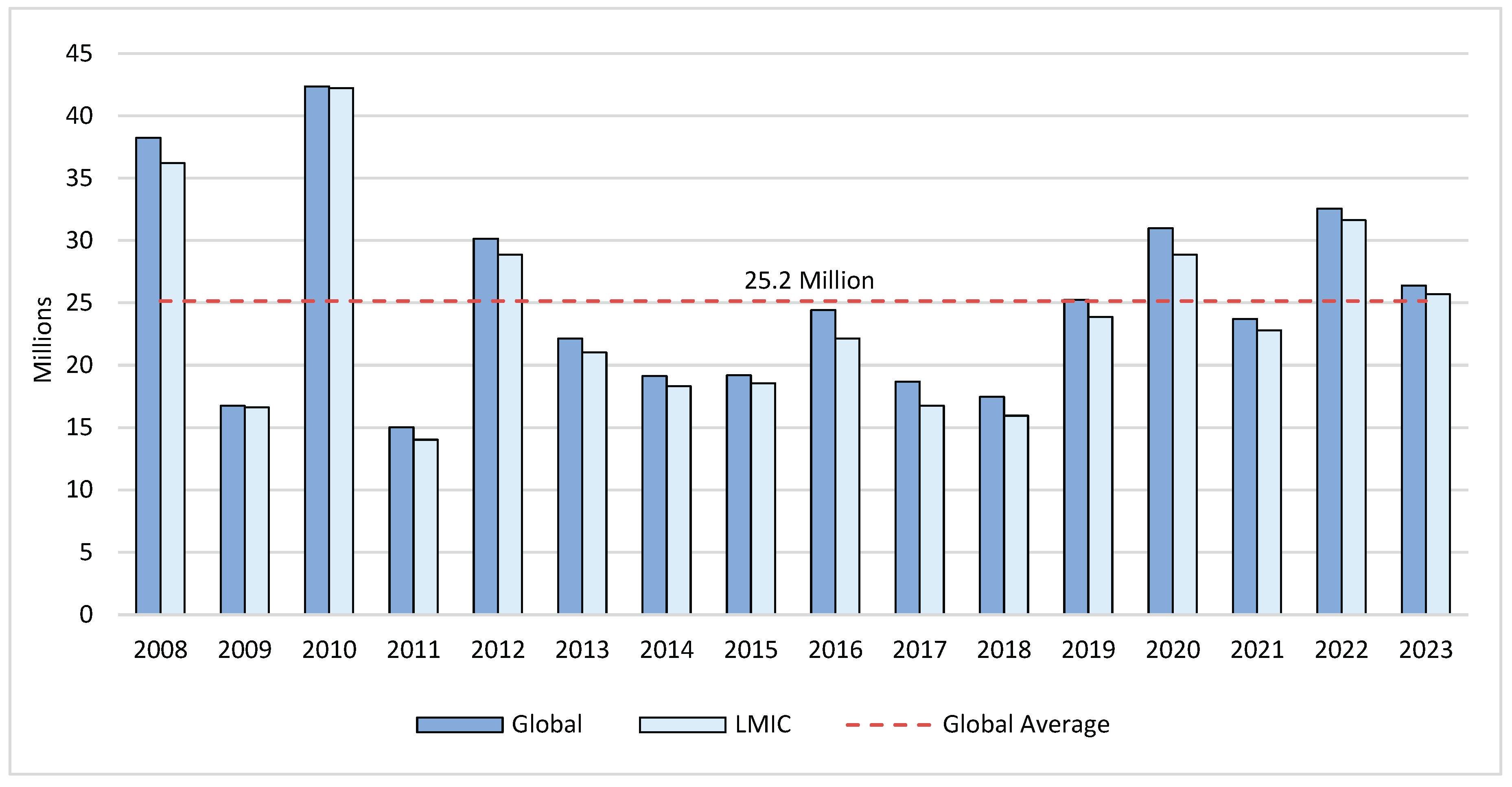

E-ACEs as a Humanitarian Crisis

Resilience Against E-ACEs

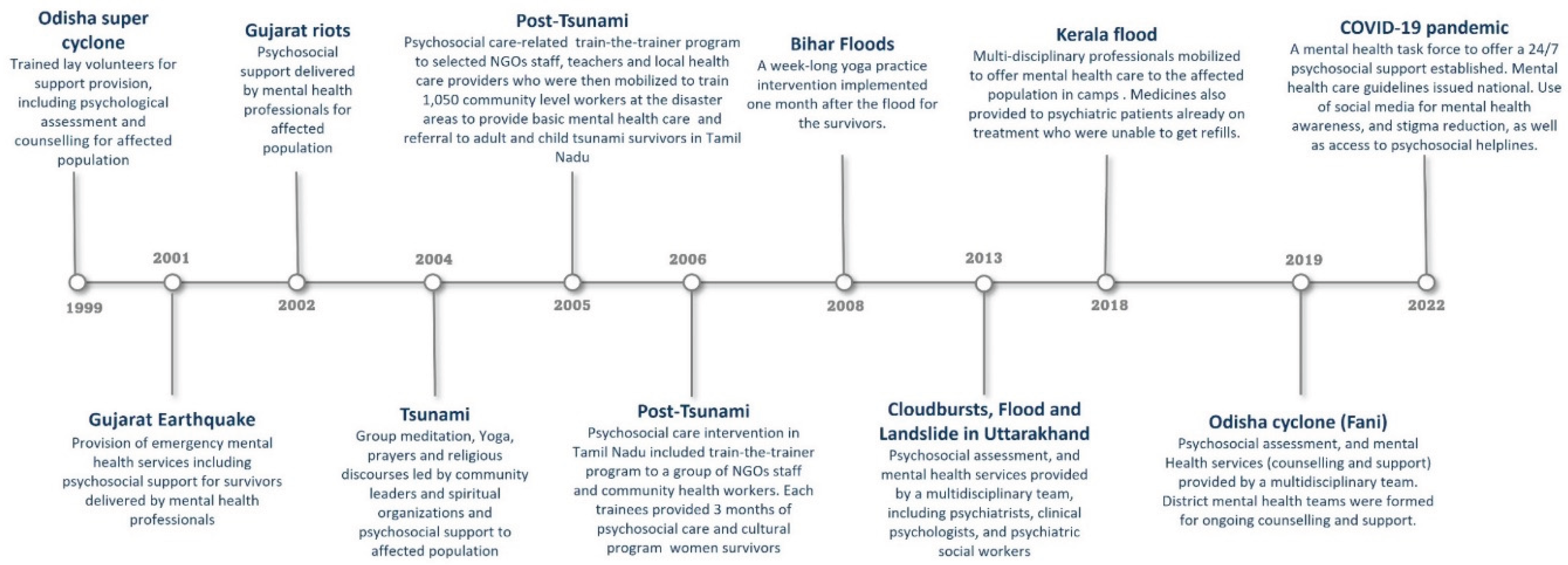

Potential Interventions for E-ACEs

Conclusions

References

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P. Natural Disasters Our World in Data; 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/natural-disasters.

- (IDMC) TIDMC. Annual Report 2022 Geneva, Switzerland: The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC); 2022. Available online: https://api.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/IDMC_Annual_Report_2022.pdf.

- Garschagen, M.; Doshi, D.; Reith, J.; Hagenlocher, M. Global patterns of disaster and climate risk—an analysis of the consistency of leading index-based assessments and their results. Climatic Change. 2021, 169, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louise, S.; Elizabeth, G. 1328 Climate change, children’s development and the Griffiths III community. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2022, 107 (Suppl 2), A317. [Google Scholar]

- Nashwan, A.J.; Ahmed, S.H.; Shaikh, T.G.; Waseem, S. Impact of natural disasters on health disparities in low- to middle-income countries. Discover Health Systems. 2023, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, A.; McElroy, S.; Levy, M.; Gershunov, A.; Benmarhnia, T. Precipitation variability and risk of infectious disease in children under 5 years for 32 countries: a global analysis using Demographic and Health Survey data. Lancet Planet Health. 2022, 6, e147–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, K.; Jiang, X.; Li, C.; Yue, Q.; et al. Impact of extreme weather on dengue fever infection in four Asian countries: A modelling analysis. Environment International. 2022, 169, 107518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Galea, S.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Ursano, R.J.; Wessely, S. Trends in mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Mol Psychiatry. 2008, 13, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xue, C.; Zhang, L. A meta-analysis of risk factors for depression in adults and children after natural disasters. BMC Public Health. 2014, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, R.; Reyes, R.; Matte, M.; Ntaro, M.; Mulogo, E.; Metlay, J.P.; et al. Severe Flooding and Malaria Transmission in the Western Ugandan Highlands: Implications for Disease Control in an Era of Global Climate Change. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016, 214, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.; Vicarelli, M. El Niño and children: Medium-term effects of early-life weather shocks on cognitive and health outcomes. World Development. 2022, 150, 105690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.S.; Kelley, M.L.; Harrison, K.M.; Thompson, J.E.; Self-Brown, S. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms among children after Hurricane Katrina: A latent profile analysis. Journal of child and family studies. 2015, 24, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N.; Sharma, P.; Murali, N.; Mehrotra, S. Mental health consequences of the trauma of super-cyclone 1999 in Orissa. Indian journal of psychiatry. 2004, 46, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, A.C.; Van Hooff, M. Impact of childhood exposure to a natural disaster on adult mental health: 20-year longitudinal follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009, 195, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, G.Y.; Zacher, M.; Merdjanoff, A.A.; Do, M.P.; Pham, N.K.; Abramson, D.M. The effects of cumulative natural disaster exposure on adolescent psychological distress. J Appl Res Child. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N. Suicidality following a natural disaster. American journal of disaster medicine. 2010, 5, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burke, S.E.L.; Sanson, A.V.; Van Hoorn, J. The Psychological Effects of Climate Change on Children. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, K.; Blashki, G.; Wiseman, J.; Burke, S.; Reifels, L. Climate change and mental health: risks, impacts and priority actions. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2018, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Change, I.P.O.C. Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2013. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/.

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Deneault, A.A.; Racine, N.; Park, J.; Thiemann, R.; Zhu, J.; et al. Adverse childhood experiences: a meta-analysis of prevalence and moderators among half a million adults in 206 studies. World Psychiatry. 2023, 22, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Chapman, D.P.; Williamson, D.F.; Giles, W.H. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001, 286, 3089–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, M.A.; McLaughlin, K.A. Dimensions of early experience and neural development: deprivation and threat. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2014, 18, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S. Improving the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study Scale. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013, 167, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T. Impact of adverse childhood experience on physical and mental health: A life-course epidemiology perspective. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2022, 76, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, J.J.; Davis, J.P.; Lee, D.S.; Pakdaman, S. Expanding adverse child experiences to inequality and racial discrimination. Preventive Medicine. 2022, 157, 107016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Terry, J. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on mental disorders in young adulthood: Latent classes and community violence exposure. Preventive Medicine. 2020, 134, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Wu, D.; He, X.; Ma, Q.; Peng, J.; Mao, G.; et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between bullying and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2023, 23, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Slack, K.S.; Berger, L.M.; Mather, R.S.; Murray, R.K. Childhood Poverty, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and Adult Health Outcomes. Health & Social Work. 2021, 46, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, K.; Cahill, G.; Tieu, T.; Njoroge, W. Reviewing the Literature on the Impact of Gun Violence on Early Childhood Development. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthanna, S.; Sara, H.; Panos, V.; Basel, E.-K.; Nader, A.-D. Children’s prolonged exposure to the toxic stress of war trauma in the Middle East. BMJ. 2020, 371, m3155. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, L.M. Is COVID-19 an adverse childhood experience (ACE): Implications for screening for primary care. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2020, 222, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weems, C.F.; Russell, J.D.; Herringa, R.J.; Carrion, V.G. Translating the neuroscience of adverse childhood experiences to inform policy and foster population-level resilience. Am Psychol. 2021, 76, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auchincloss, A.H.; Ruggiero, D.A.; Donnelly, M.T.; Chernak, E.D.; Kephart, J.L. Adolescent mental distress in the wake of climate disasters. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2024, 39, 102651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.D.; Heyn, S.A.; Peverill, M.; DiMaio, S.; Herringa, R.J. Traumatic and Adverse Childhood Experiences and Developmental Differences in Psychiatric Risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025, 82, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Children displaced by a changing climate: preparing for a future already underway.: UNICEF; 2023. Available online: https://www.unicefusa.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/ClimateDisplacementReport.pdf.

- Seehusen, D.A.; Bowman, M.A.; Britz, J.; Ledford, C.J.W. A Focus on Climate Change and How It Impacts Family Medicine. J Am Board Fam Med. 2024, 37, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Maheen, H.; Bowen, K. Mental health impacts from repeated climate disasters: an Australian longitudinal analysis. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific. 2024, 47, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, A.; Baldwin, J.R. Hidden Wounds? Inflammatory Links Between Childhood Trauma and Psychopathology. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017, 68, 517–544. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, C.A.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Burke Harris, N.; Danese, A.; Samara, M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ. 2020, 371, m3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F.A. The impact of child maltreatment and psychopathology on neuroendocrine functioning. Dev Psychopathol. 2001, 13, 783–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnar, M.R.; Vazquez, D. Stress neurobiology and developmental psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology: Volume Two: Developmental Neuroscience. 2015:533-77.

- Miller, G.E.; Cole, S.W. Clustering of depression and inflammation in adolescents previously exposed to childhood adversity. Biol Psychiatry. 2012, 72, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Maletic, V.; Raison, C.L. Inflammation and Its Discontents: The Role of Cytokines in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2009, 65, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelzaher, H.; Tawfik, S.M.; Nour, A.; Abdelkader, S.; Elbalkiny, S.T.; Abdelkader, M.; et al. Climate change, human health, and the exposome: Utilizing OMIC technologies to navigate an era of uncertainty. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 973000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagaria, A.; Fiori, V.; Vacca, M.; Lombardo, C.; Pariante, C.M.; Ballesio, A. Inflammation as a mediator between adverse childhood experiences and adult depression: A meta-analytic structural equation model. J Affect Disord. 2024, 357, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, N.; He, W.; Zhang, K.; Cui, J.; Chen, J.; Cheng, J.; et al. Association of short-term air pollution with systemic inflammatory biomarkers in routine blood test: A longitudinal study. Environmental Research Letters. 2021, 16(3).

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature Medicine. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellizzi, S.; Popescu, C.; Panu Napodano, C.M.; Fiamma, M.; Cegolon, L. Global health, climate change and migration: The need for recognition of "climate refugees". J Glob Health. 2023, 13, 03011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellermann, N.P. Epigenetic transmission of Holocaust trauma: can nightmares be inherited? Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2013, 50, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Harville, E.W.; Shankar, A.; Dunkel Schetter, C.; Lichtveld, M. Cumulative effects of the Gulf oil spill and other disasters on mental health among reproductive-aged women: The Gulf Resilience on Women’s Health study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2018, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weems, C.F.; Poleacovschi, C.; Ikuma, K. A perspective for identifying intersections among the social, engineering, and geosciences to address water crises. Frontiers in Water. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weems, C.F.; Watts, S.E.; Marsee, M.A.; Taylor, L.K.; Costa, N.M.; Cannon, M.F.; et al. The psychosocial impact of Hurricane Katrina: contextual differences in psychological symptoms, social support, and discrimination. Behav Res Ther. 2007, 45, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.; Poleacovschi, C.; Ikuma, K.; Garcia, I.; Weems, C.; Rehmann, C.; et al. Knowledge–Behavior Gap in Tap Water Consumption in Puerto Rico: Implications for Water Utilities. ASCE OPEN Multidisciplinary Journal of Civil Engineering. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Varghese, B.M.; Hansen, A.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dear, K.; et al. Is there an association between hot weather and poor mental health outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2021, 153:106533.

- Hunt, A.P.; Brearley, M.; Hall, A.; Pope, R. Climate Change Effects on the Predicted Heat Strain and Labour Capacity of Outdoor Workers in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 20(9).

- Vergunst, F.; Berry, H.L. Climate Change and Children's Mental Health: A Developmental Perspective. Clin Psychol Sci. 2022, 10, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. Health and Well-Being of Climate Migrants in Slum Areas of Dhaka. In: Leal Filho W, Wall T, Azul AM, Brandli L, Özuyar PG, editors. Good Health and Well-Being. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 277-93.

- Rana, M.M.P.; Ilina, I.N. Climate change and migration impacts on cities: Lessons from Bangladesh. Environmental Challenges. 2021, 5, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (BBS), B.B.o.S. Census of slum areas and floating population 2014 Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2015 [Available from: https://dataspace.princeton.edu/bitstream/88435/dsp01wm117r42q/1.

- Joshi, R.; Andersen, P.T.; Thapa, S.; Aro, A.R. Sex trafficking, prostitution, and increased HIV risk among women during and after the 2015 Nepal earthquake. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120938287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, S.; Guerra, C.; Toro, E.; Pinto-Cortez, C. Advancing the science of adverse childhood experiences and resilience: A case for global and ecological perspectives. Child Protection and Practice. 2024, 3:100060.

- Bilak, A.; Cardona-Fox, G.; Ginnetti, J.; Rushing, E.J.; Scherer, I.; Swain, M.; et al. Global Report on Internal Displacement Geneva, Switzerland: Internal Displacement Monitorring Center (IDMC); 2016. Available online: https://api.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/2016-global-report-internal-displacement-IDMC.pdf.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. IDMC Data Portal 2024. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/database/displacement-data/.

- (IEP), I.f.E.P. Ecological threat report 2024: Analysing ecological threats, resilience & peace Sydney, Australia: Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP); 2024. Available online: https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ETR-2024-web.pdf.

- Association, A.P. Association, A.P. APA Dictionary of Psychology: Resilience Washington, DC 20002-4242: American Psychological Association; 2025. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience.

- Beese, S.; Drumm, K.; Wells-Yoakum, K.; Postma, J.; Graves, J.M. Flexible Resources Key to Neighborhood Resilience for Children: A Scoping Review. Children (Basel). 2023, 10(11).

- DiClemente, C.M.; Rice, C.M.; Quimby, D.; Richards, M.H.; Grimes, C.T.; Morency, M.M.; et al. Resilience in Urban African American Adolescents: The Protective Enhancing Effects of Neighborhood, Family, and School Cohesion Following Violence Exposure. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2018, 38, 1286–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppelt, B. Transformational resilience: How building human resilience to climate disruption can safeguard society and increase wellbeing: Routledge; 2017.

- Masten, A.S.; Best, K.M.; Garmezy, N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990, 2, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.; Obradović, J. Disaster Preparation and Recovery: Lessons from Research on Resilience in Human Development. Ecology and Society. 2008, 13(1).

- Nijs, L.; Nicolaou, G. Flourishing in Resonance: Joint Resilience Building Through Music and Motion. Front Psychol. 2021, 12:666702.

- Yule, K.; Houston, J.; Grych, J. Resilience in Children Exposed to Violence: A Meta-analysis of Protective Factors Across Ecological Contexts. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2019, 22, 406–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slemp, C.C.; Sisco, S.; Jean, M.C.; Ahmed, M.S.; Kanarek, N.F.; Erös-Sarnyai, M.; et al. Applying an Innovative Model of Disaster Resilience at the Neighborhood Level:The COPEWELL New York City Experience. Public Health Reports. 2020, 135, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, T.G.; Bricknell, L.K.; Preston, R.G.; Crawford, E.G.C. Climate Change Adaptation Methods for Public Health Prevention in Australia: an Integrative Review. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2024, 11, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Links, J.M.; Schwartz, B.S.; Lin, S.; Kanarek, N.; Mitrani-Reiser, J.; Sell, T.K.; et al. COPEWELL: A Conceptual Framework and System Dynamics Model for Predicting Community Functioning and Resilience After Disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2018, 12, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahdoot, S.; Baum, C.R.; Cataletto, M.B.; Hogan, P.; Wu, C.B.; Bernstein, A.; et al. Climate change and children’s health: building a healthy future for every child. Pediatrics. 2024, 153(3).

- Bhalla, G.; Knowles, M.; Dahlet, G.; Poudel, M. Scoping review on the role of social protection in facilitating climate change adaptation and mitigation for economic inclusion among rural populations. 2024.

- Zenda, M.; Rudolph, M. A Systematic Review of Agroecology Strategies for Adapting to Climate Change Impacts on Smallholder Crop Farmers’ Livelihoods in South Africa. Climate. 2024, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Peter, G.; Von Dahlen, S.; Saxena, S.C. Unmitigated disasters? New evidence on the macroeconomic cost of natural catastrophes. 2012.

- Reduction, U.U.N.O.f.D.R. Disaster displacement: How to reduce risks, address impacts, and strengthen resilience 2024. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/words-into-action/disaster-displacement-how-reduce-risk-address-impacts-and-strengthen-resilience.

- Kar, N. Psychosocial issues following a natural disaster in a developing country: a qualitative longitudinal observational study. International Journal of Disaster Medicine. 2006, 4, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Routray, J.K. Household response to cyclone and induced surge in coastal Bangladesh: coping strategies and explanatory variables. Natural Hazards. 2011, 57, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickrama, T.; Wickrama, K.; Banford, A.; Lambert, J. PTSD symptoms among tsunami exposed mothers in Sri Lanka: the role of disaster exposure, culturally specific coping strategies, and recovery efforts. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2017, 30, 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Senarath, S.K. Well-being of students affected by disaster: A case study of 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Disaster Management. 2021, 3, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.M. Psychosocial care for adult and child survivors of the 2004 tsunami disaster in India. Am J Public Health. 2006, 96, 1397–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.M. Psychosocial care for women survivors of the tsunami disaster in India. American journal of public health. 2009, 99, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, S.; Singh, N.; Joshi, M.; Balkrishna, A. Post traumatic stress symptoms and heart rate variability in Bihar flood survivors following yoga: a randomized controlled study. BMC psychiatry. 2010, 10:1-10.

- Satapathy, S. Mental health impacts of disasters in India: ex-ante and ex-post analysis. Economic and welfare impacts of disasters in East Asia and policy responses ERIA research project report. 2011, 8:425-61.

- Bhadra, S. Psychosocial support for the children affected by communal violence in Gujarat, India. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies. 2012, 9, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttichira, P.; Kallivayalil, R.A.; James, A.; Thomas, C.; Rahiman, A. Immediate Mental Health Response to Kerala Floods 2018 Victims. World Social Psychiatry. 2020, 2, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kola, L.; Kohrt, B.A.; Hanlon, C.; Naslund, J.A.; Sikander, S.; Balaji, M.; et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: reimagining global mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021, 8, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channaveerachari, N.K.; Raj, A.; Joshi, S.; Paramita, P.; Somanathan, R.; Chandran, D.; et al. Psychiatric and medical disorders in the after math of the uttarakhand disaster: Assessment, approach, and future challenges. Indian journal of psychological medicine. 2015, 37, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Health Impacts | Climate/weather event | Effect size |

Target population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health impacts | |||

| Infectious diseases | Precipitation variability | OR=1.81 (95% CI: 1.20–2.71) [6] | Children<5 years across 32 LMICs |

| Dengue | Extremely high temperatures | RR=1.07 (95% CI: 1.02–1.13) within 1-3 weeks following extreme temperature rises [7] | General population in Singapore, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Thailand |

| Malaria | Severe Flooding | Increased risk by approx. 30% of having positive malaria diagnostic among flood exposed compared to those living away from the river [10] | General population in the Western Ugandan highlands |

| Malnutrition | Extreme precipitation levels | 8.3% points higher likelihood of being stunted among ECEs exposed [11] | Children aged 2–6 years in Rural Mexico |

| Mental health impacts | |||

| PTS symptoms/PTSD | Hurricane | OR=3.45 (95% CI: 1.49–8.03) [12] | Children aged 8–15 years in Louisiana, USA |

| Cyclone | Prevalence=44.3% in ECEs exposed [13] | General population in Orissa, India | |

| Bushfire | Lifetime RR=1.8 (95% CI: 1.11-2.93) [14] | General population in Australia | |

| Psychological distress | Multiple Hurricanes | OR=1.41 (95% CI: 1.05–1.88) [15] | Children aged 10–17 years in Louisiana, Mississippi, and New Orleans, USA |

| Storms, snowstorms, floods, droughts, wildfire | High disaster exposure was linked to 25% and 20% higher odds of major depression over 2- and 5-year periods, respectively [35] | 12-19 years in the USA | |

| Depression | Tsunami and earthquake | Prevalence=7.5% to 44.8% among ECEs exposed [9] | Children aged 7–18 years in Armenia, China, Turkey, and Thailand |

| Cyclone | Prevalence=52.7% among ECEs exposed [13] | General population in Orissa, India | |

| Flood, bushfire, cyclone | Multiple disaster exposure was linked to a −1.8-point decline in MHI-5 scores (95% CI: −3.4 to −0.3) from baseline [39] | General population in Australia | |

| Anxiety | Bushfire | Lifetime RR=1.37 (95% CI: 1.05–1.78) [14] | General population in Australia |

| Cyclone | Prevalence=57.5% of ECEs exposed [13] | General population in Orissa, India | |

| Suicidality | Hurricane | Suicidal ideation increased from 2.8% to 6.8% post-ECEs [8] | General population in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, USA) |

| Cyclone | Prevalence=12.6% suicidal attempts, 18.3% with suicidal plans and 38% with suicidal ideas among ECEs exposed [16] | General population (Orissa, India) | |

| Cognitive- developmental impacts | |||

| Developmental delays | Extreme precipitation | Cognitive test scores in language, memory and visual-spatial thinking 0.19, 0.17 and 0.15 SDs lower than children unexposed to ECEs [11] | Children aged 2–6 years in Rural Mexico |

| Socio-structural level |

|---|

Building resilient environments, and resilient economies

|

Develop trauma-informed climate policies

|

Develop targeted policies for displaced children

|

Improve data systems and expand research in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)

|

| Community level |

Implement community-based resilience programs

|

Leverage local knowledge and resources

|

Scale-up digital mental health solutions

|

| Individual level |

Enhance early intervention strategies for at-risk children

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).