Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

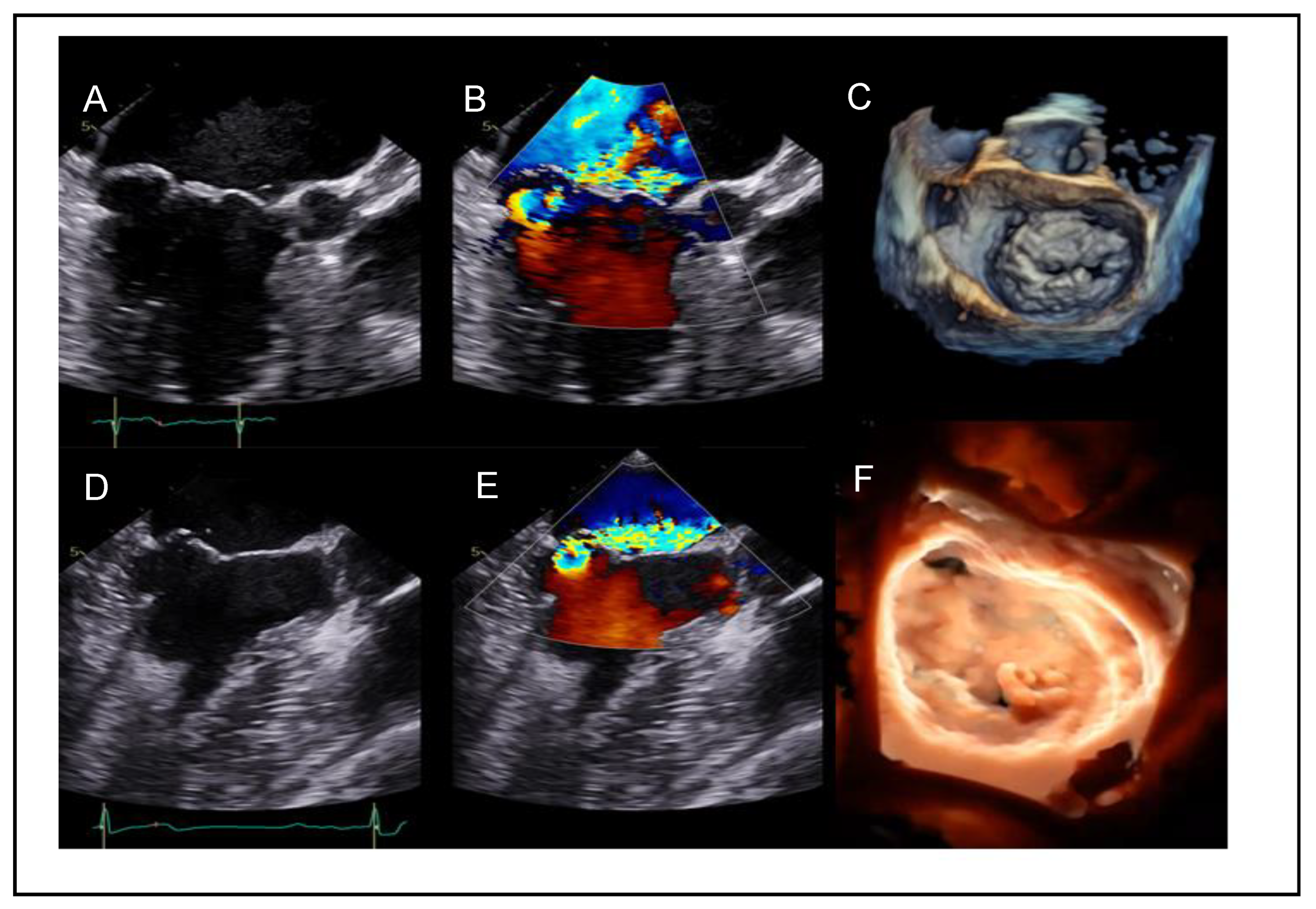

2. Echocardiographic Evaluation of MR

3. Indications for Intervention in Mitral Regurgitation

3.1. Indications for Intervention in Primary MR

3.2. Indications for Intervention in Secondary MR

4. Patient Selection and Screening Criteria

4.1. Selection in Primary Mitral Regurgitation (PMR)

4.2. Selection in Secondary Mitral Regurgitation (SMR)

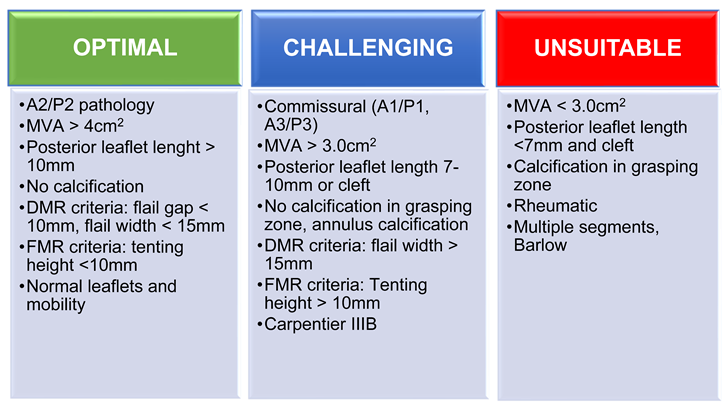

5. Anatomical Considerations for TEER

- Posterior leaflet length: A minimum of 7 mm (ideally >10mm) is typically required for adequate leaflet grasping.

- Flail gap and flail width: Severe primary MR may demonstrate a flail gap >10 mm and width >15 mm, which traditionally limited eligibility, but can be managed in experienced centers.

- Coaptation depth and coaptation length: Excessive coaptation depth (>11 mm) or reduced coaptation length (<2 mm) may pose procedural difficulty in secondary MR.

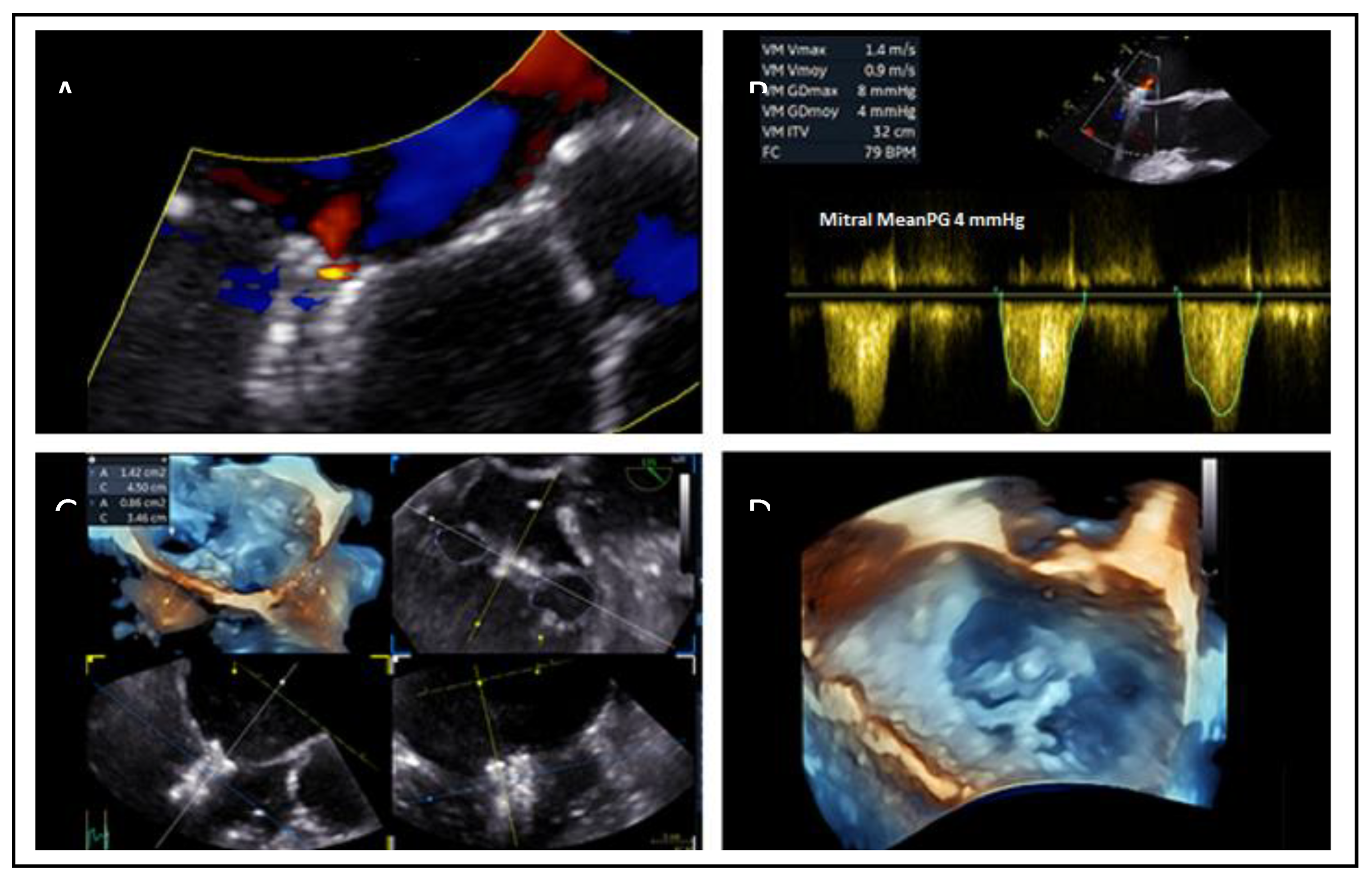

- Mitral valve area (MVA) and pressure gradient (PG): MVA <4.0 cm² may raise concern for post-procedural mitral stenosis, especially in patients requiring multiple devices. Cut-off values of 3.0cm2 for MVA and 4mmHg for mean PG are used to consider a patient ineligible for this method.

- Mitral annular and leaflet calcification: These may hinder adequate device deployment and leaflet grasping.

- Mitral annulus dimensions: Small dimensions of annulus (annulus area, anterior-posterior and medial-lateral diameters) should also be considered in the screening process.

6. Implications for Clinical Practice

7. Preprocedural Echocardiographic Assessment

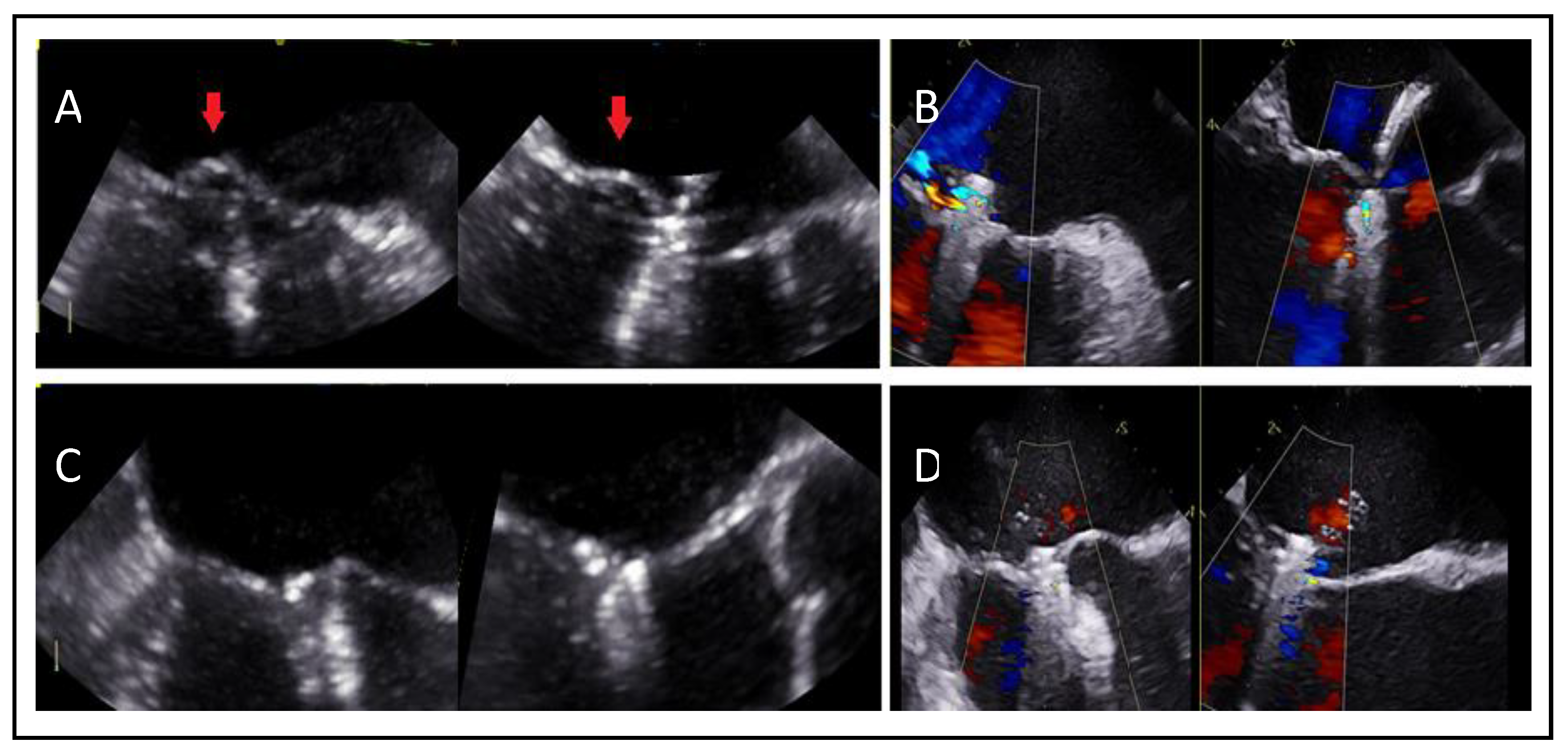

7.1. Mitral Valve Anatomy

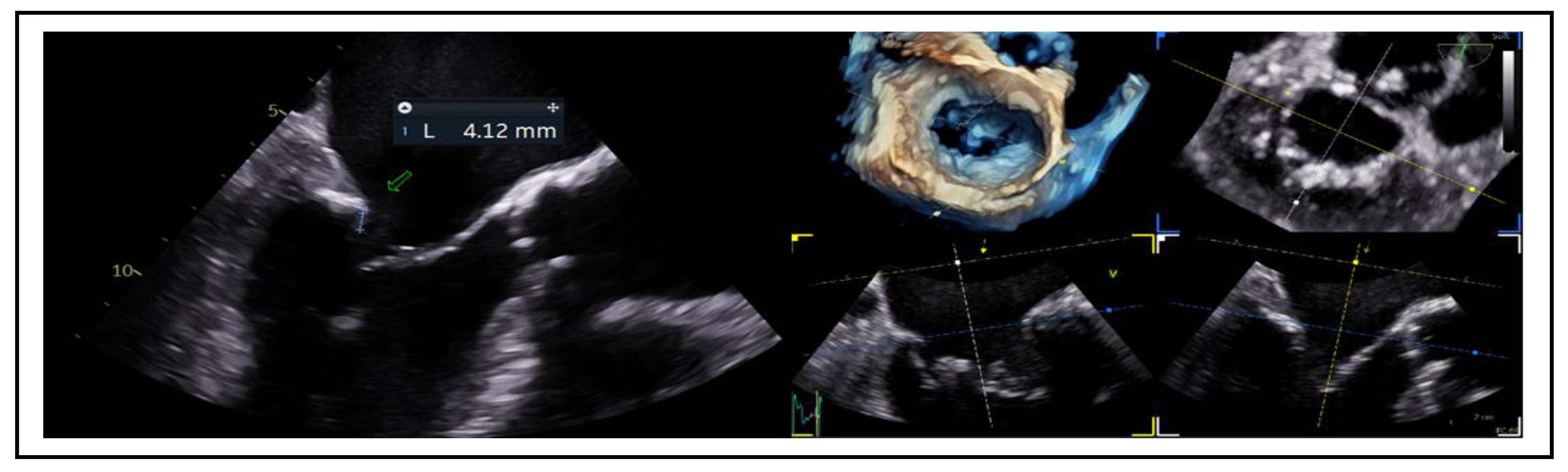

7.2. Posterior Leaflet Length

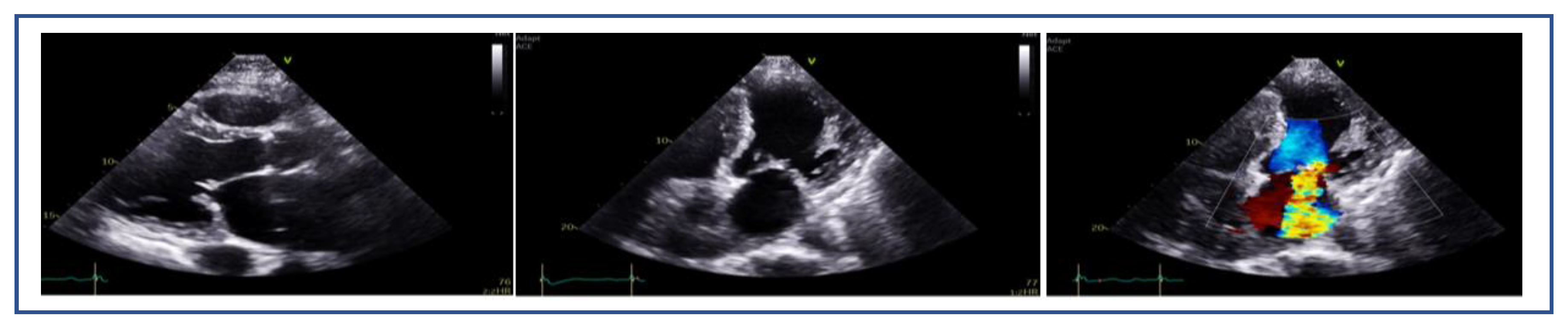

7.3. Mitral Valve Area and Gradient

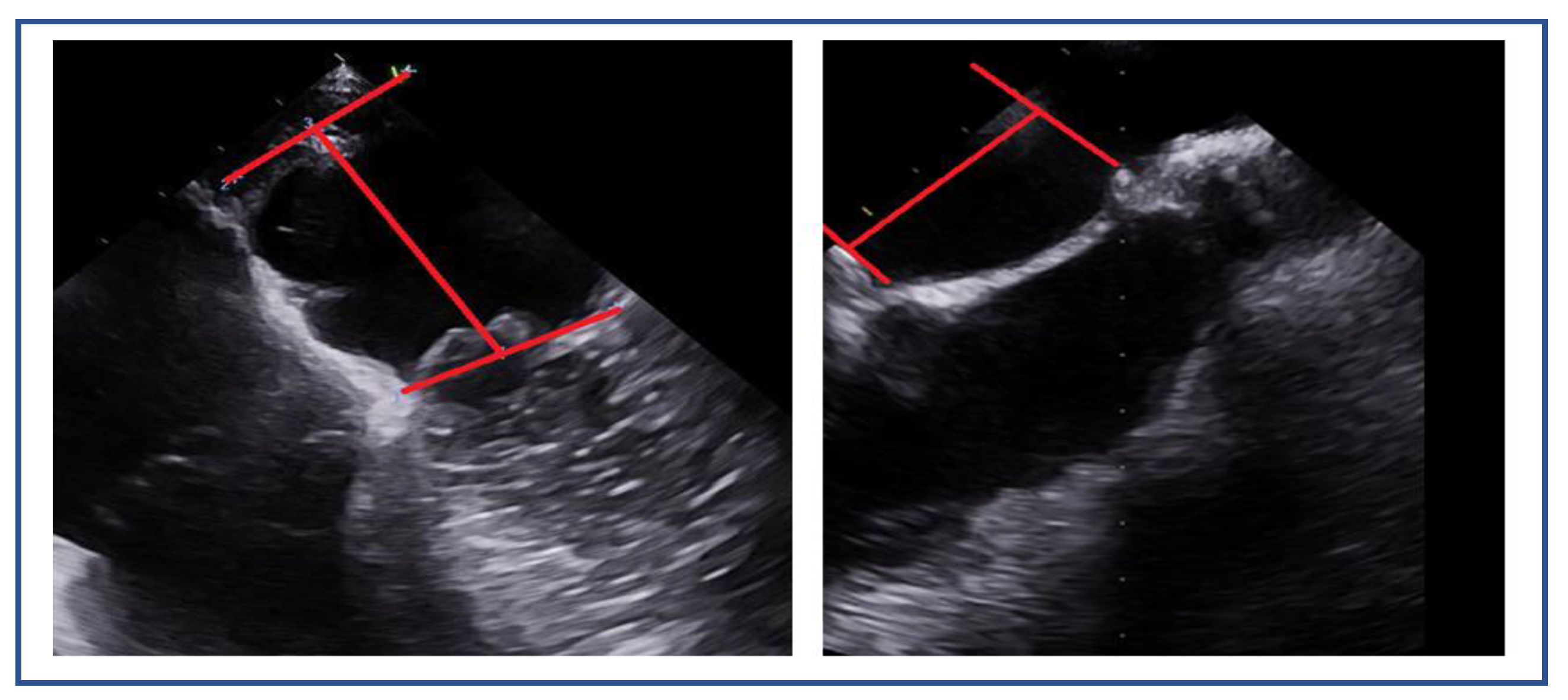

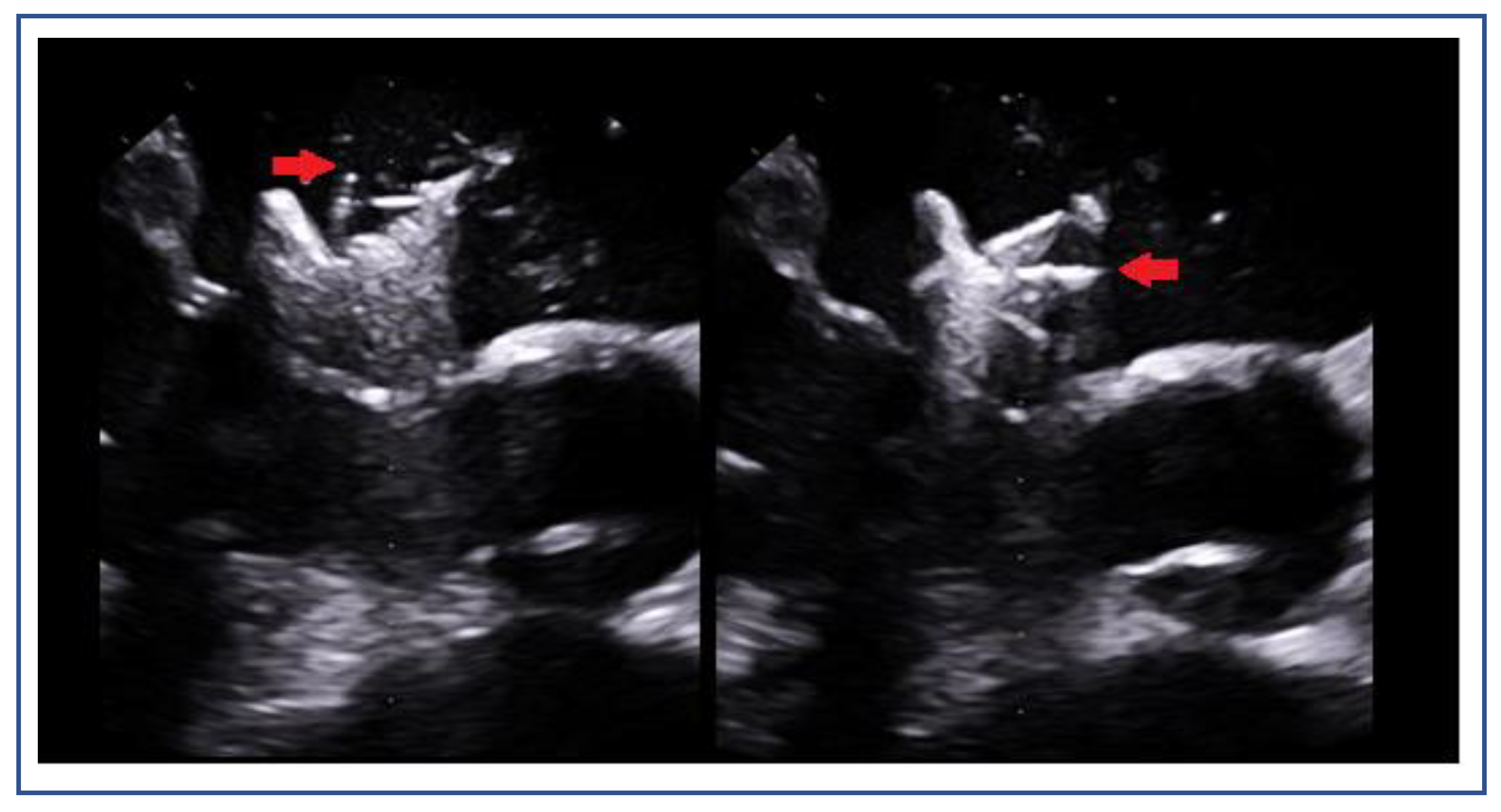

7.4. Flail Gap and Width (PMR)

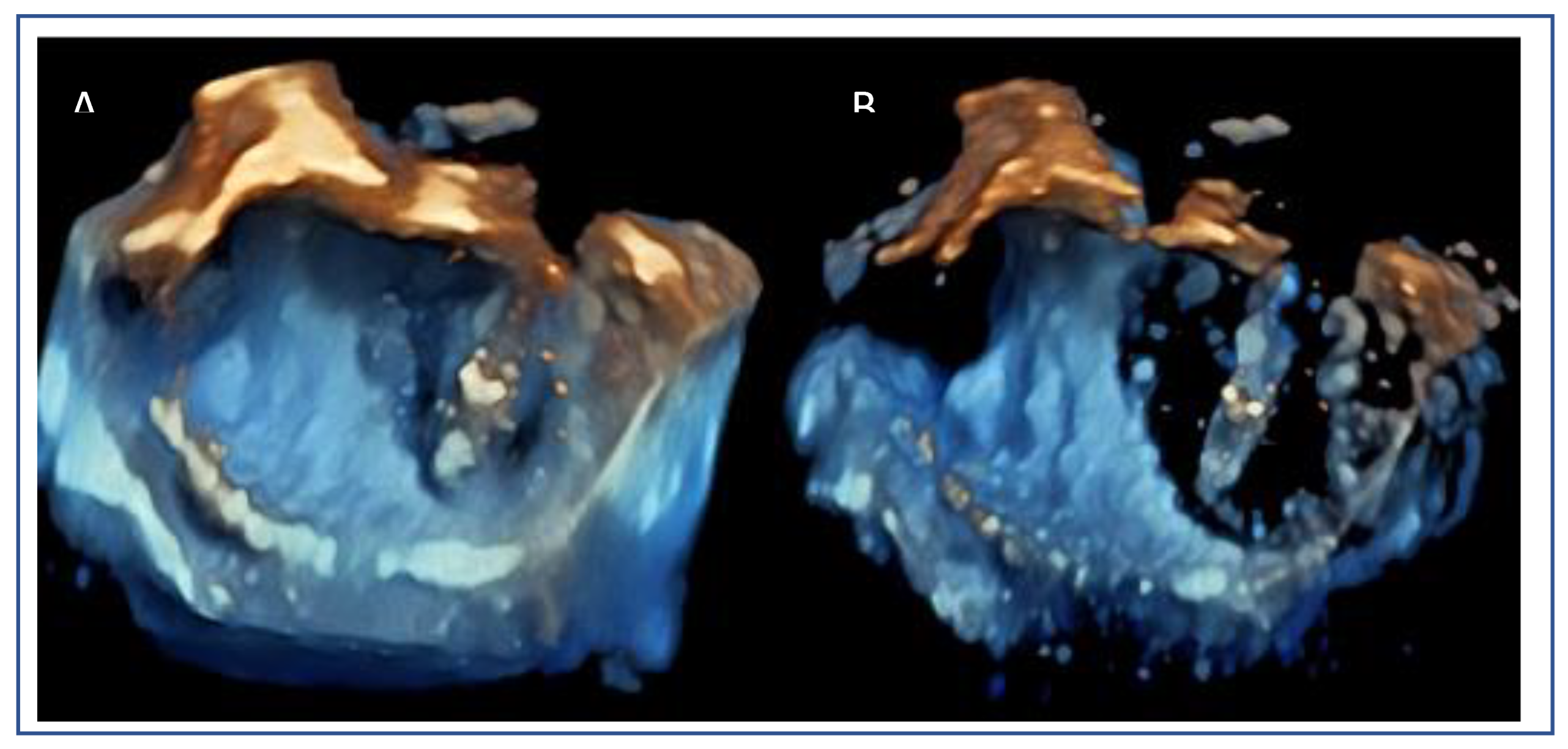

7.5. Tenting Height and Coaptation Length (SMR)

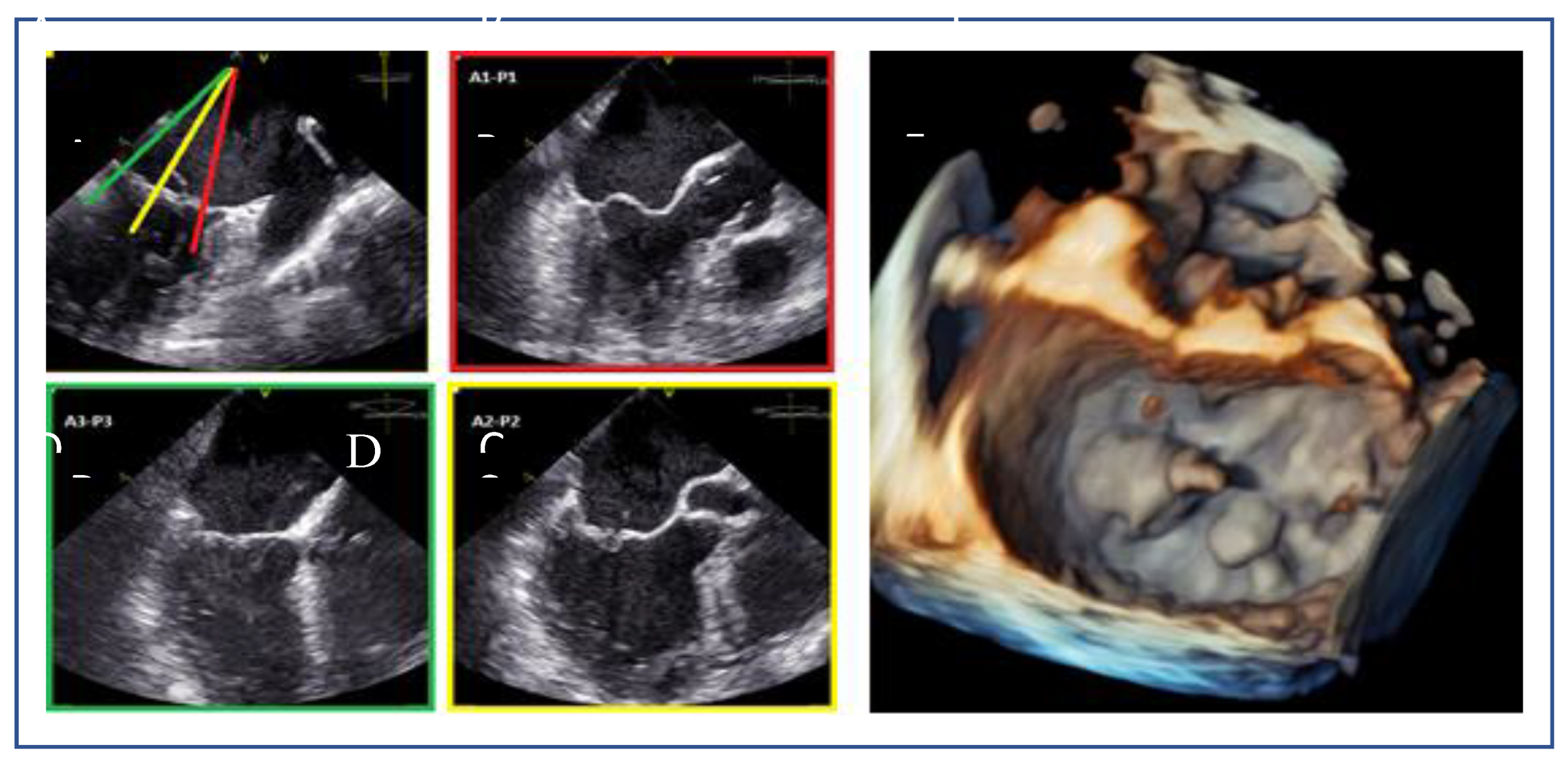

8. Anatomical Challenges

-

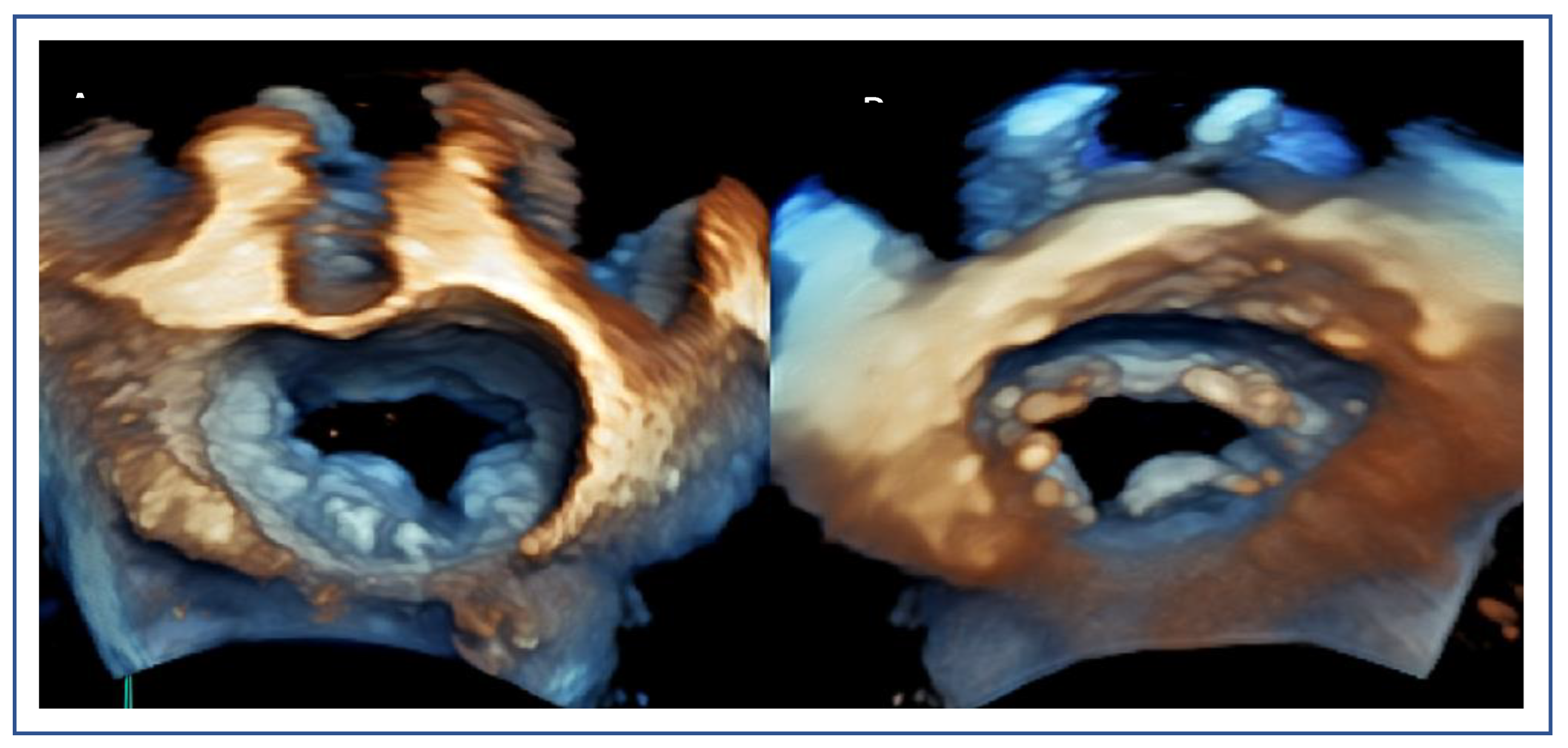

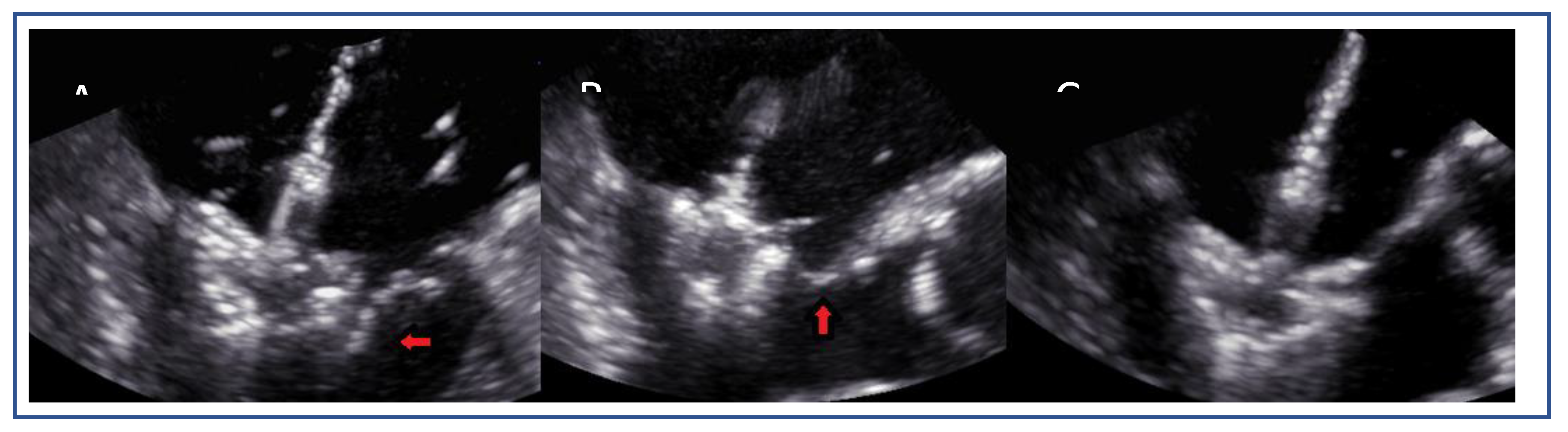

Posterior Leaflet Cleft-like IndentationThe posterior leaflet normally has two indentations that differentiate the scallops. A cleft-like indentation is defined as having a depth of at least 50% of the adjacent scallops [37,38] and 3D imaging is the best option to recognize such abnormalities (Figure 9). This feature makes grasping challenging and may lead to residual mitral regurgitation (MR).

-

Leaflet and Annular Calcification

-

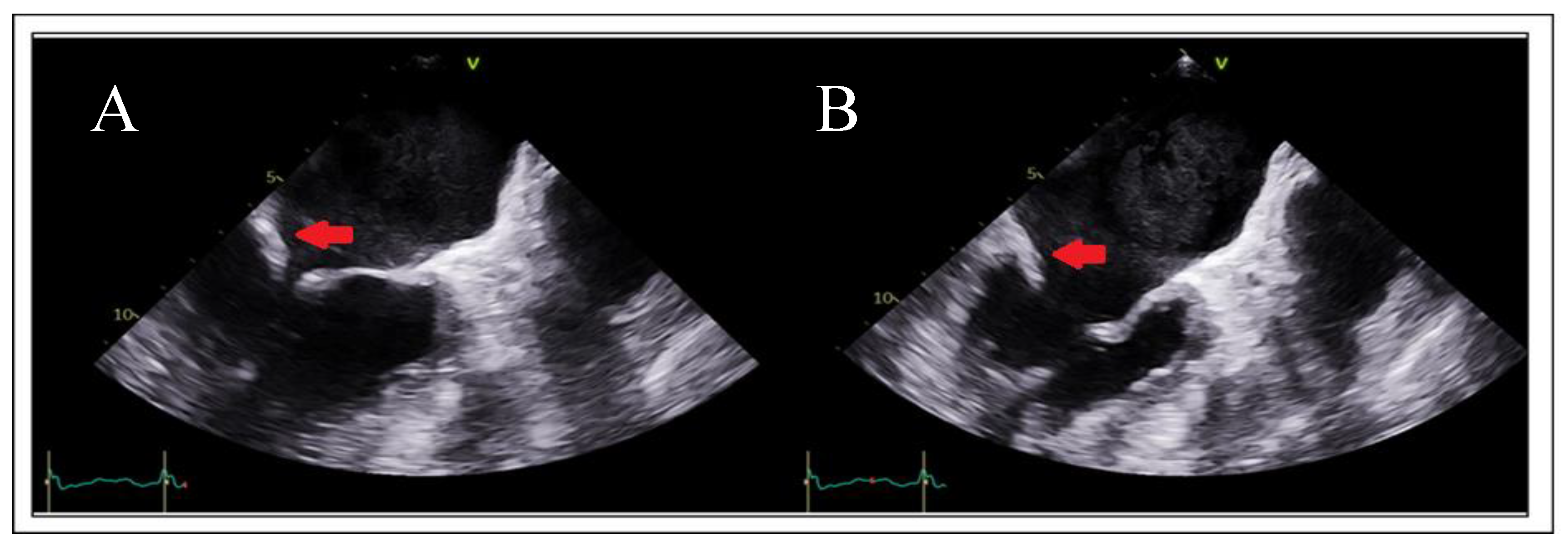

Adequate but Tethered LeafletsPosterior leaflet length may be sufficient, but severe tethering reduces coaptation and grasping success (Figure 11).

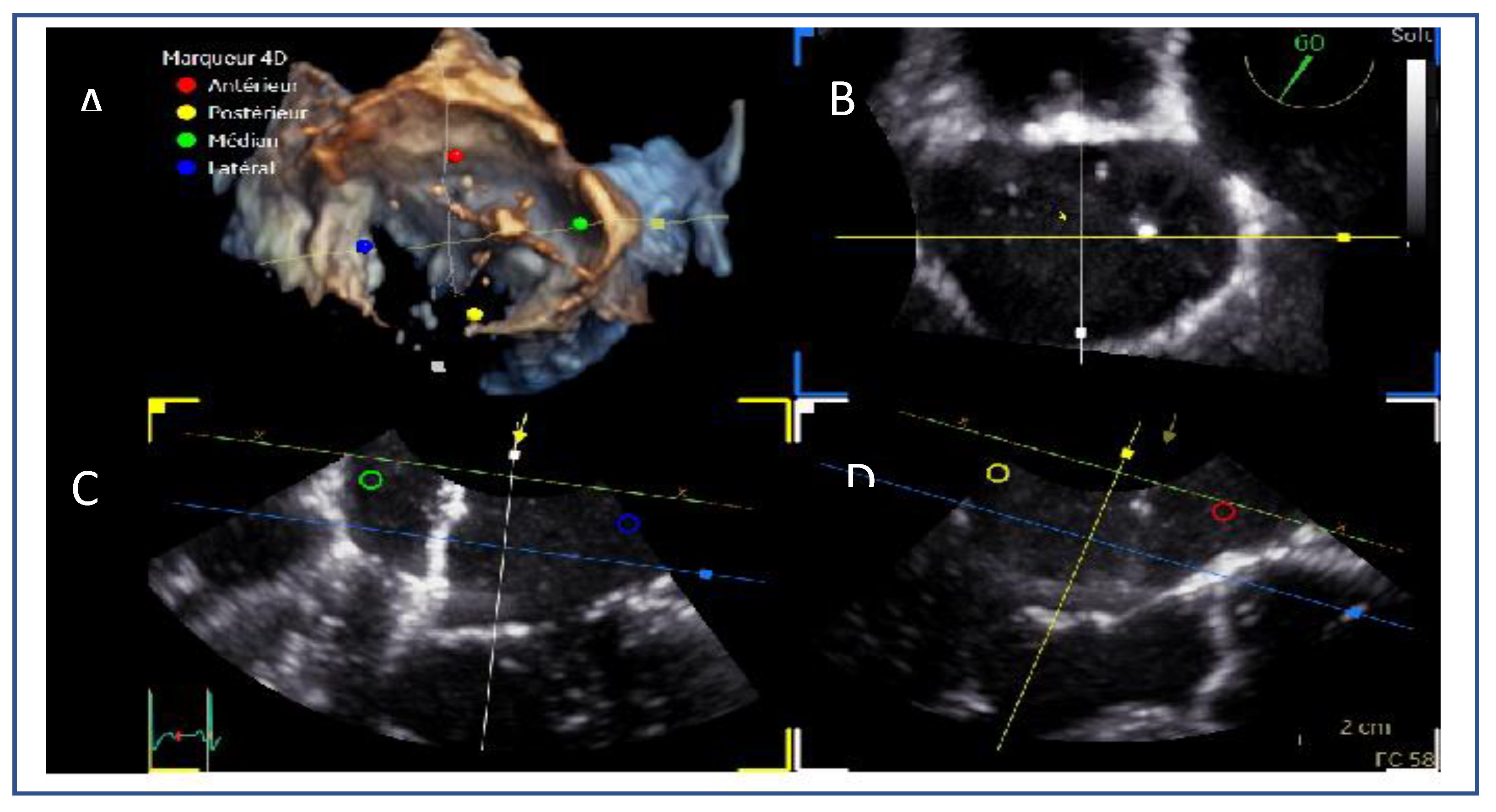

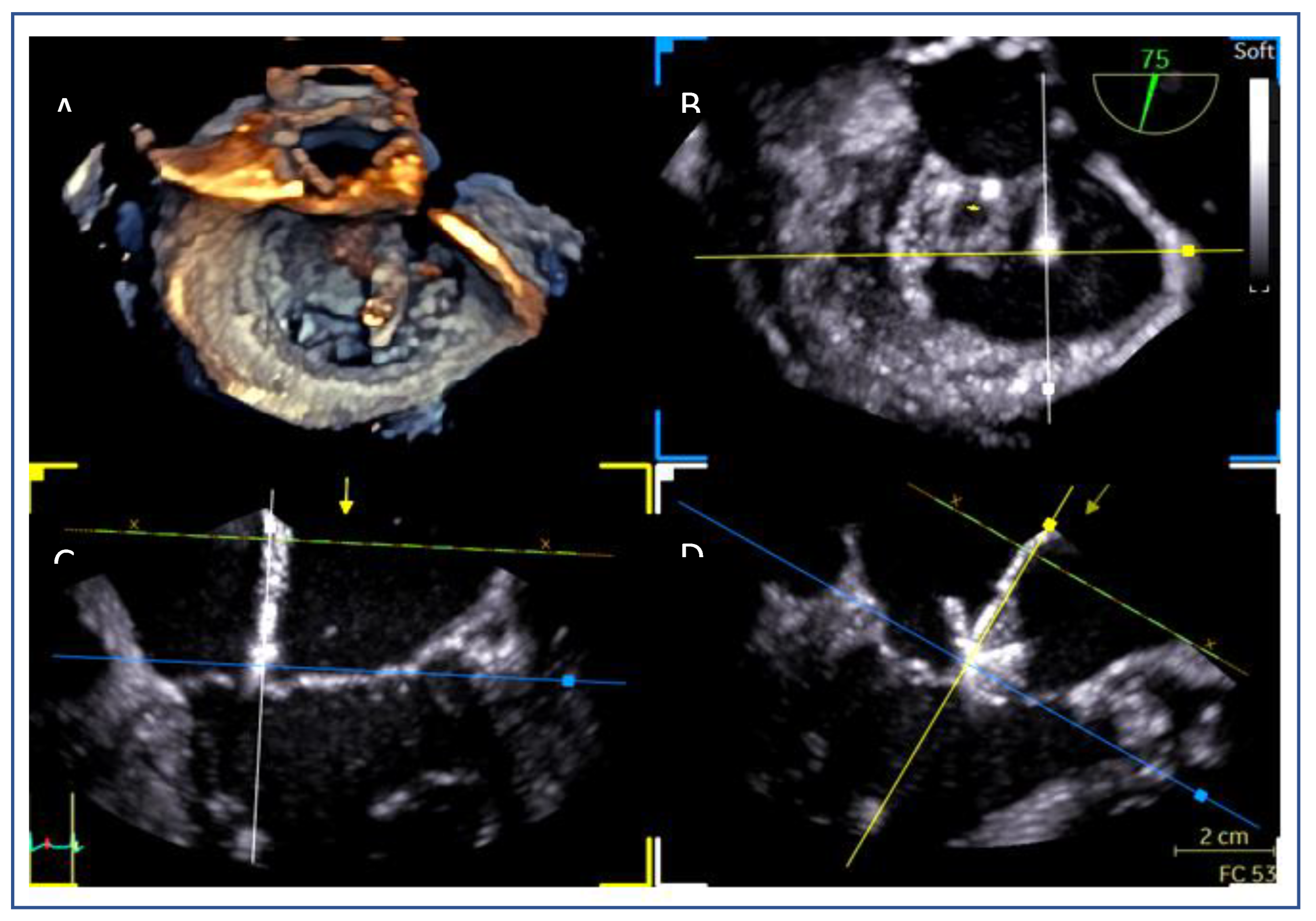

9. Intraprocedural Guidance

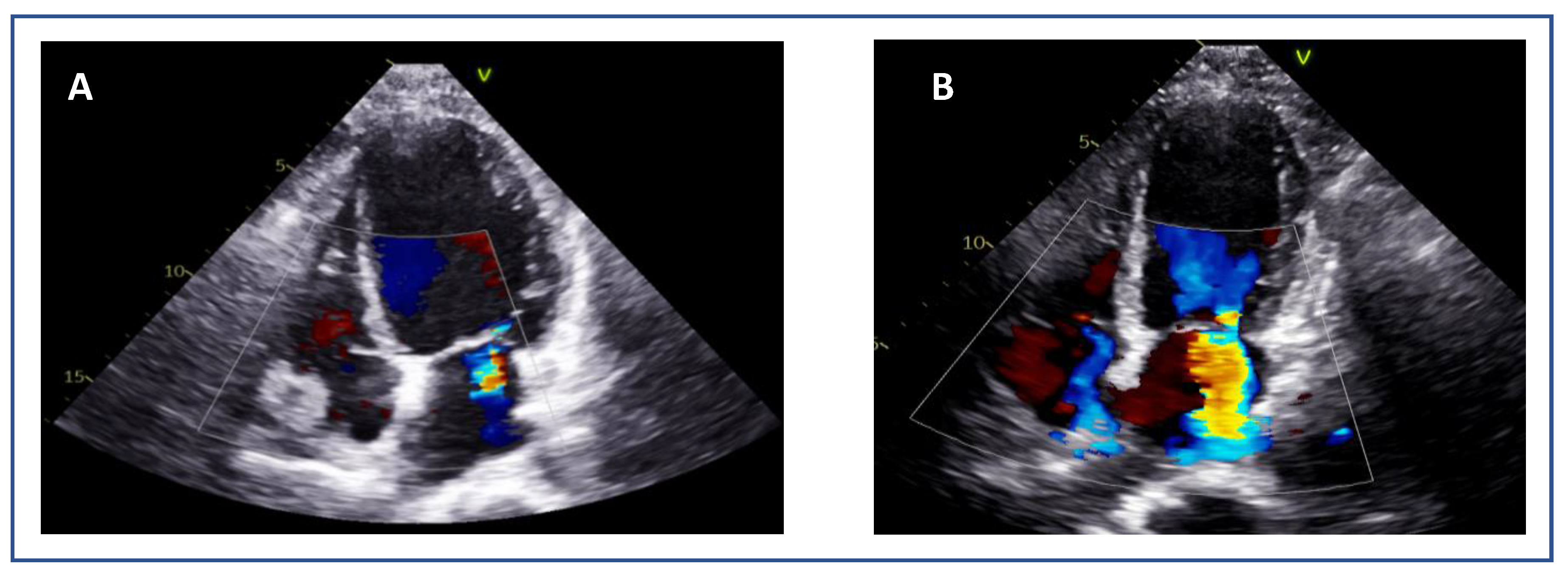

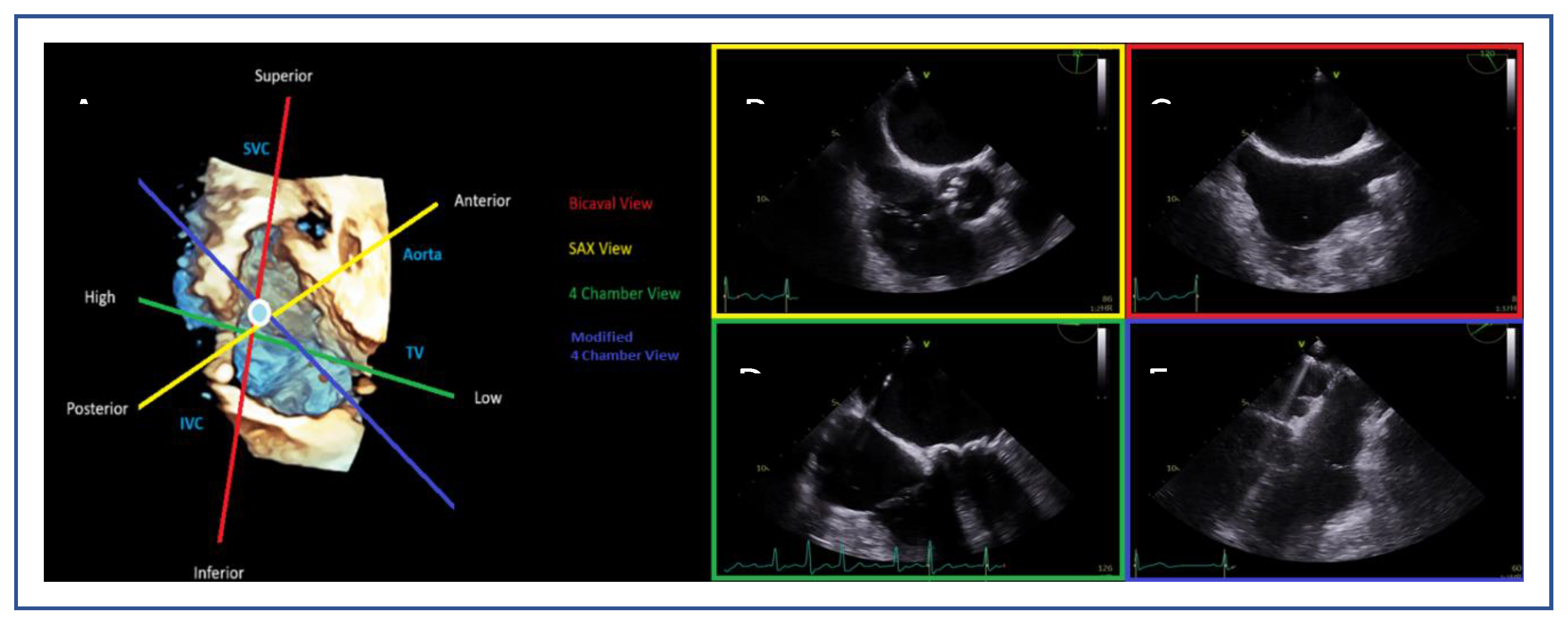

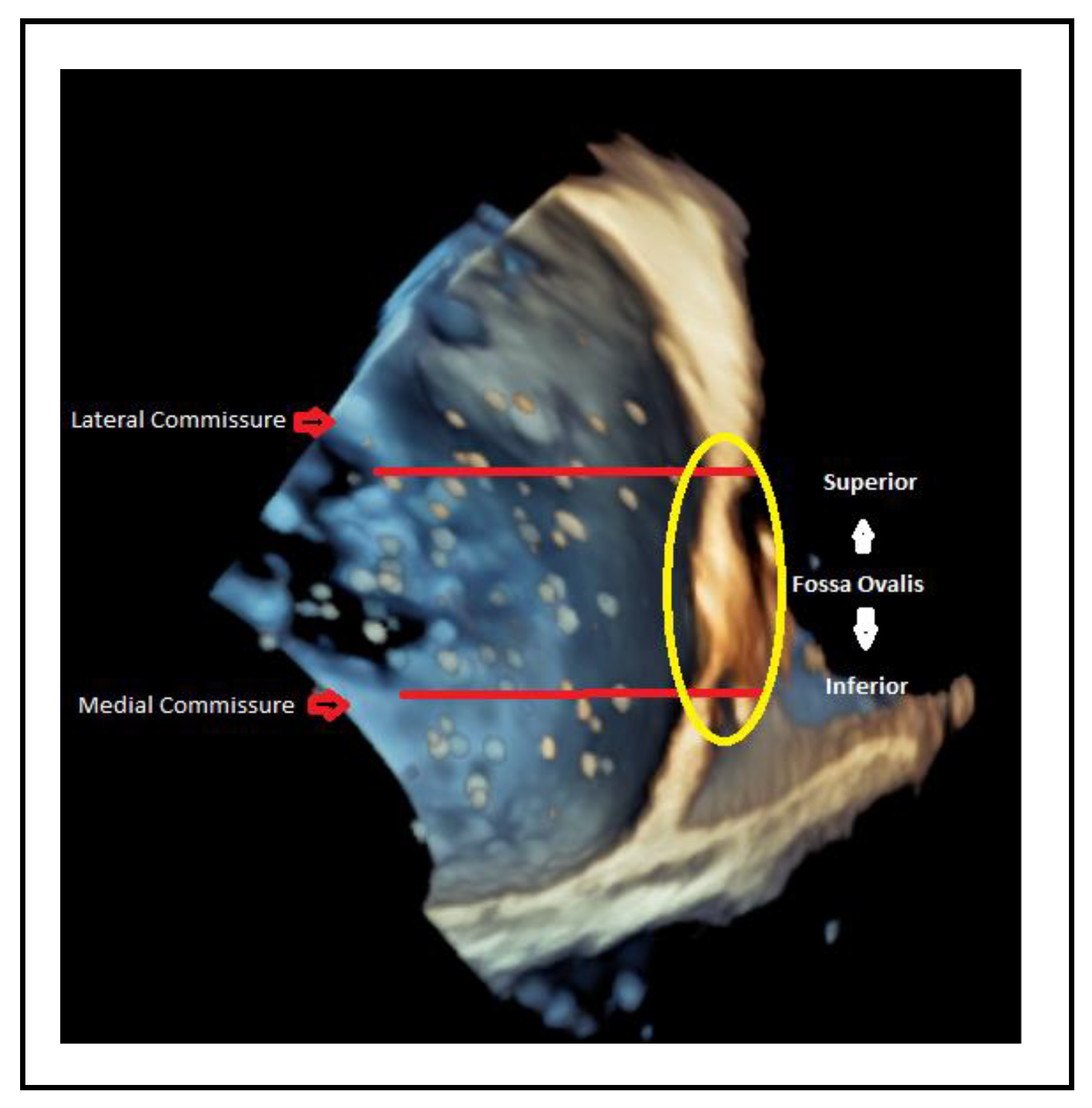

9.1. Transseptal Puncture

- Lateral commissure: A superior and lower puncture height, approximately 3.5 cm, is preferred to facilitate access.[40]

- Medial commissure: A more inferior puncture, closer to the inferior vena cava (IVC), with a higher height of 4.5–5 cm is recommended for better alignment. [41]

- Ventricular functional MR: The puncture height should be set 1 cm lower than the usual height to match the coaptation depth.[40]

9.2. Navigating the Device

9.3. Device Alignment and Implantation

9.4. Leaflet Grasping

9.5. Device Deployment and Release

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFMR | atrial functional MR |

| BTT | bridge-to-transplant |

| CRT | cardiac resynchronization therapy |

| DMR | degenerative mitral regurgitation |

| EROA | effective regurgitant orifice area |

| GDMT | guideline-directed medical therapy |

| HF | heart failure |

| IVC | inferior vena cava |

| LA | left atrium |

| LAVI | left atrial volume index |

| LV | left ventricle |

| LVAD | left ventricular assist device |

| LVEDV | left ventricular end-diastolic volume |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVESD | left ventricular end-systolic diameter |

| MPR | multiplanar reconstruction |

| MR | mitral regurgitation |

| M-TEER | mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair |

| MV | mitral valve |

| MVA | mitral valve area |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association Class |

| PCI | percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PMR | primary mitral regurgitation |

| RF | regurgitant fraction |

| RVol | regurgitant volume |

| SMR | secondary mitral regurgitation |

| SPAP | systolic pulmonary artery pressure |

| TAVI | transcatheter aortic valve implantation |

| TEE/TOE | transesophageal echocardiography |

| TR | tricuspid regurgitation |

| VC | vena contracta |

References

- Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. The Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1005-11. [CrossRef]

- Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Bärwolf C, Levang OW, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. European Heart Journal. 2003;24(13):1231-43.

- Zoghbi William A, Levine Robert A, Flachskampf F, Grayburn P, Gillam L, Leipsic J, et al. Atrial Functional Mitral Regurgitation. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2022;15(11):1870-82.

- Prakash R, Horsfall M, Markwick A, Pumar M, Lee L, Sinhal A, et al. Prognostic impact of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation (MR) irrespective of concomitant comorbidities: a retrospective matched cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7):e004984. [CrossRef]

- Enriquez-Sarano M, Akins CW, Vahanian A. Mitral regurgitation. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1382-94.

- Sannino A, Smith RL, 2nd, Schiattarella GG, Trimarco B, Esposito G, Grayburn PA. Survival and Cardiovascular Outcomes of Patients With Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(10):1130-9.

- Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, et al. Recommendations for Noninvasive Evaluation of Native Valvular Regurgitation: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2017;30(4):303-71.

- Grayburn PA. How to measure severity of mitral regurgitation: valvular heart disease. Heart. 2008;94(3):376-83.

- Lancellotti P, Pibarot P, Chambers J, La Canna G, Pepi M, Dulgheru R, et al. Multi-modality imaging assessment of native valvular regurgitation: an EACVI and ESC council of valvular heart disease position paper. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(5):e171-e232. [CrossRef]

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European Heart Journal. 2021;43(7):561-632. [CrossRef]

- Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, 3rd, Gentile F, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):e25-e197.

- Enriquez-Sarano M, Avierinos JF, Messika-Zeitoun D, Detaint D, Capps M, Nkomo V, et al. Quantitative determinants of the outcome of asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(9):875-83. [CrossRef]

- Bartko PE, Arfsten H, Heitzinger G, Pavo N, Toma A, Strunk G, et al. A Unifying Concept for the Quantitative Assessment of Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(20):2506-17.

- Bertrand PB, Schwammenthal E, Levine RA, Vandervoort PM. Exercise Dynamics in Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Implications. Circulation. 2017;135(3):297-314.

- Onishi H, Izumo M, Naganuma T, Nakamura S, Akashi YJ. Dynamic Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: Current Evidence and Challenges for the Future. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:883450. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein D, Moskowitz Aj Fau - Gelijns AC, Gelijns Ac Fau - Ailawadi G, Ailawadi G Fau - Parides MK, Parides Mk Fau - Perrault LP, Perrault Lp Fau - Hung JW, et al. Two-Year Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Severe Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation. (1533-4406 (Electronic)).

- Baldus S, Doenst T, Pfister R, Gummert J, Kessler M, Boekstegers P, et al. Transcatheter Repair versus Mitral-Valve Surgery for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2024;391(19):1787-98. [CrossRef]

- Mack MJ, Abraham WT, Lindenfeld J, Bolling SF, Feldman TE, Grayburn PA, et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip in Patients with Heart Failure and Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: Design and rationale of the COAPT trial. American Heart Journal. 2018;205:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski P, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS, Butler J, Shahzeb Khan M, Diek M, et al. Hospitalization of Symptomatic Patients With Heart Failure and Moderate to Severe Functional Mitral Regurgitation Treated With MitraClip: Insights From RESHAPE-HF2. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84(24):2347-63.

- Obadia J-F, Messika-Zeitoun D, Leurent G, Iung B, Bonnet G, Piriou N, et al. Percutaneous Repair or Medical Treatment for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(24):2297-306. [CrossRef]

- Feldman T, Foster E, Glower DD, Kar S, Rinaldi MJ, Fail PS, et al. Percutaneous repair or surgery for mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1395-406.

- Grayburn PA, Sannino A, Packer M. Proportionate and Disproportionate Functional Mitral Regurgitation: A New Conceptual Framework That Reconciles the Results of the MITRA-FR and COAPT Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(2):353-62.

- Namazi F, van der Bijl P, Fortuni F, Mertens BJA, Kamperidis V, van Wijngaarden SE, et al. Regurgitant Volume/Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Volume Ratio: Prognostic Value in Patients With Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(4):730-9.

- Berrill M, Beeton I, Fluck D, John I, Lazariashvili O, Stewart J, et al. Disproportionate Mitral Regurgitation Determines Survival in Acute Heart Failure. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:742224. [CrossRef]

- Anker SD, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS, Butler J, Khan MS, Diek M, et al. Percutaneous repair of moderate-to-severe or severe functional mitral regurgitation in patients with symptomatic heart failure: Baseline characteristics of patients in the RESHAPE-HF2 trial and comparison to COAPT and MITRA-FR trials. (1879-0844 (Electronic)).

- Anker SD, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS, Butler J, Khan MS, Diek M, et al. Transcatheter Valve Repair in Heart Failure with Moderate to Severe Mitral Regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(19):1799-809. [CrossRef]

- Asgar AW, Tang GHL, Rogers JH, Rottbauer W, Morse MA, Denti P, et al. Evaluating Mitral TEER in the Management of Moderate Secondary Mitral Regurgitation Among Heart Failure Patients. (2213-1787 (Electronic)).

- Giannini C, Petronio As Fau - De Carlo M, De Carlo M Fau - Guarracino F, Guarracino F Fau - Conte L, Conte L Fau - Fiorelli F, Fiorelli F Fau - Pieroni A, et al. Integrated reverse left and right ventricular remodelling after MitraClip implantation in functional mitral regurgitation: an echocardiographic study. (2047-2412 (Electronic)).

- Scandura S, Ussia Gp Fau - Capranzano P, Capranzano P Fau - Caggegi A, Caggegi A Fau - Sarkar K, Sarkar K Fau - Cammalleri V, Cammalleri V Fau - Mangiafico S, et al. Left cardiac chambers reverse remodeling after percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system. (1097-6795 (Electronic)).

- Papadopoulos K, Ikonomidis I, Chrissoheris M, Chalapas A, Kourkoveli P, Parissis J, et al. MitraClip and left ventricular reverse remodelling: a strain imaging study. (2055-5822 (Electronic)).

- Citro R, Baldi C, Lancellotti P, Silverio A, Provenza G, Bellino M, et al. Global longitudinal strain predicts outcome after MitraClip implantation for secondary mitral regurgitation. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 2017;18(9). [CrossRef]

- Godino C, Munafò A, Scotti A, Estévez-Loureiro R, Portolés Hernández A, Arzamendi D, et al. MitraClip in secondary mitral regurgitation as a bridge to heart transplantation: 1-year outcomes from the International MitraBridge Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(12):1353-62. [CrossRef]

- Jung RG, Simard T, Kovach C, Flint K, Don C, Di Santo P, et al. Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair in Cardiogenic Shock and Mitral Regurgitation: A Patient-Level, Multicenter Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(1):1-11.

- Gavazzoni M, Taramasso M, Zuber M, Russo G, Pozzoli A, Miura M, et al. Conceiving MitraClip as a tool: percutaneous edge-to-edge repair in complex mitral valve anatomies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(10):1059-67. [CrossRef]

- Boekstegers P, Hausleiter J, Baldus S, von Bardeleben RS, Beucher H, Butter C, et al. Percutaneous interventional mitral regurgitation treatment using the Mitra-Clip system. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103(2):85-96. [CrossRef]

- Adamo M, Chiari E, Curello S, Maiandi C, Chizzola G, Fiorina C, et al. Mitraclip therapy in patients with functional mitral regurgitation and missing leaflet coaptation: is it still an exclusion criterion? Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(10):1278-86.

- Ring L, Rana BS, Ho SY, Wells FC. The prevalence and impact of deep clefts in the mitral leaflets in mitral valve prolapse. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(6):595-602. [CrossRef]

- La Canna G, Arendar I, Maisano F, Monaco F, Collu E, Benussi S, et al. Real-time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography for assessment of mitral valve functional anatomy in patients with prolapse-related regurgitation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(9):1365-74. [CrossRef]

- Praz F, Braun D, Unterhuber M, Spirito A, Orban M, Brugger N, et al. Edge-to-Edge Mitral Valve Repair With Extended Clip Arms: Early Experience From a Multicenter Observational Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(14):1356-65.

- Radinovic A, Mazzone P, Landoni G, Agricola E, Regazzoli D, Della-Bella P. Different transseptal puncture for different procedures: Optimization of left atrial catheterization guided by transesophageal echocardiography. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016;19(4):589-93. [CrossRef]

- Harb SC, Cohen JA, Krishnaswamy A, Kapadia SR, Miyasaka RL. Targeting the Future: Three-Dimensional Imaging for Precise Guidance of the Transseptal Puncture. Struct Heart. 2025;9(1):100340. [CrossRef]

- Hausleiter J, Stocker TJ, Adamo M, Karam N, Swaans MJ, Praz F. Mitral valve transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. EuroIntervention. 2023;18(12):957-76. [CrossRef]

- Stone GW, Adams DH, Abraham WT, Kappetein AP, Généreux P, Vranckx P, et al. Clinical Trial Design Principles and Endpoint Definitions for Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair and Replacement: Part 2: Endpoint Definitions: A Consensus Document From the Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(3):308-21.

- El Shaer A, Chavez Ponce AA, Ali MT, Oguz D, Pislaru SV, Nkomo VT, et al. Pulmonary Vein Flow Morphology After Transcatheter Mitral Valve Edge-to-Edge Repair as Predictor of Survival. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;37(5):530-7.

- Sato H, Cavalcante JL, Enriquez-Sarano M, Bae R, Fukui M, Bapat VN, et al. Significance of Spontaneous Echocardiographic Contrast in Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair for Mitral Regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2023;36(1):87-95. [CrossRef]

- Maisano F, Franzen O, Baldus S, Schäfer U, Hausleiter J, Butter C, et al. Percutaneous mitral valve interventions in the real world: early and 1-year results from the ACCESS-EU, a prospective, multicenter, nonrandomized post-approval study of the MitraClip therapy in Europe. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(12):1052-61.

| COAPT-eligible characteristics | COAPT-ineligible characteristics |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).