1. Introduction

The modified Rankin Scale (mRS), a clinician-administered stroke assessment tool, has been central to stroke care since its introduction in 1957 [

1]. Initially developed to categorize functional recovery of patients at hospital discharge, its application has now expanded, leading to certain limitations in its effectiveness. The mRS is currently used in several different settings, such as for acute stroke assessment, follow up assessments and primarily used as an outcome measure in clinical trials. The assessment is typically administered around the 90-day mark after the stroke and can be conducted in person or via phone call. The purpose of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) has shifted from a categorical discharge tool to a long-term functional disability assessment that contributes to the knowledge of treatment success. With this shift, an update to the mRS is needed to maintain effectiveness.

The results and data taken from the mRS have real implications for clinical decision making, and patient care within stroke research care delivery. The administration of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) currently shows a lack of standardized assessment causing issues with inter-rater reliability [

2]. The existing methodology, without a standardized approach for gathering corroborative information, introduces variability in the mRS's application allowing for incongruous cognitive processes influencing scoring outcomes. This impacts inter-rater reliability and potentially affects the scale's overall reliability in clinical outcomes [

3]. This study uses results from a preliminary online questionnaire completed by Canadian clinicians to understand current uses and challenges of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS).

This paper explores the principles required for a new design to improve the process of assigning an mRS grade to patients. By developing parameters and guidelines for a detailed clinical assessment tool (CAT) which will transition into a simple and intuitive user interface following basic design principles, we aim to enhance inter-rater reliability of assigning mRS scores across diverse clinical settings. The development of the design principles for a new mRS tool were informed from our online survey results.

2. Modified Rankin Scale Overview and Related Works

The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) is widely used in stroke care as an assessment for patients after a stroke event. Despite its frequent use, the scales accuracy and reliability have been questioned, with studies showing various levels of inter-rater reliability [

1,

2,

3] and criticism for its broad categories [

1,

2]. Originally developed to categorize a patient's functional recovery at hospital discharge, the mRS is currently primarily used for long-term disability assessments [

1]. The original Rankin Scale from 1957 was a single item with five rankings which represented no disability, slight, moderate, moderately severe, and severe disability. It was modified once in 1988 alongside an Aspirin stroke prevention study. In this addition, a ranking of zero was added to indicate no symptoms, death was added as a sixth grade and the wording for levels one and two were altered [

4,

5]. The mRS has since been criticized for being `broad and poorly defined' leaving room for subjective and personal perceptions. The descriptions of the mRS grades contribute to the inter-observer variation between clinician administrators [

6].

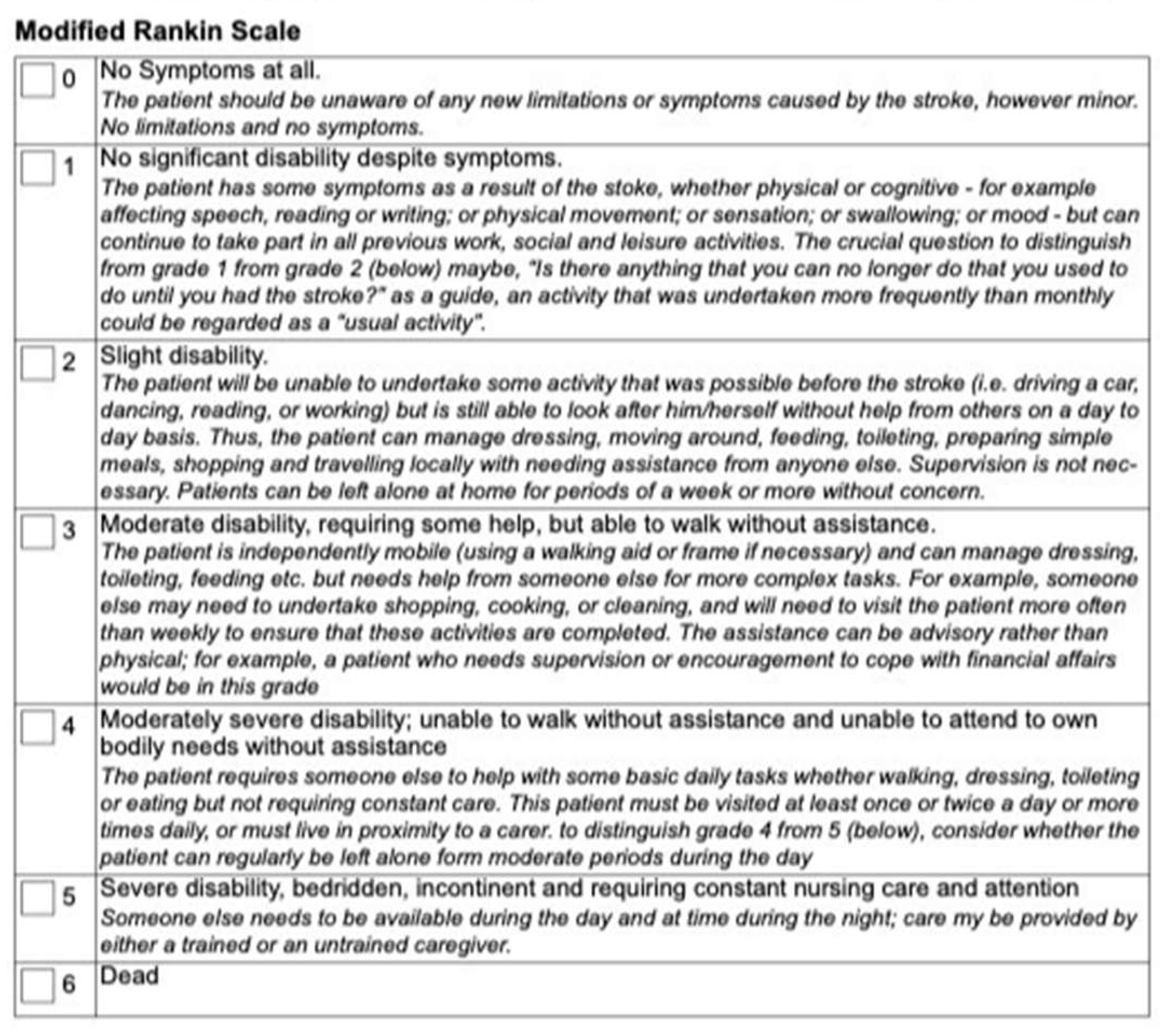

Figure 1 shows an example of the standard mRS grade definitions with some indicators and guidelines for scoring italicized under the score, from a Clinical Trial lead by the University of Calgary [

7].

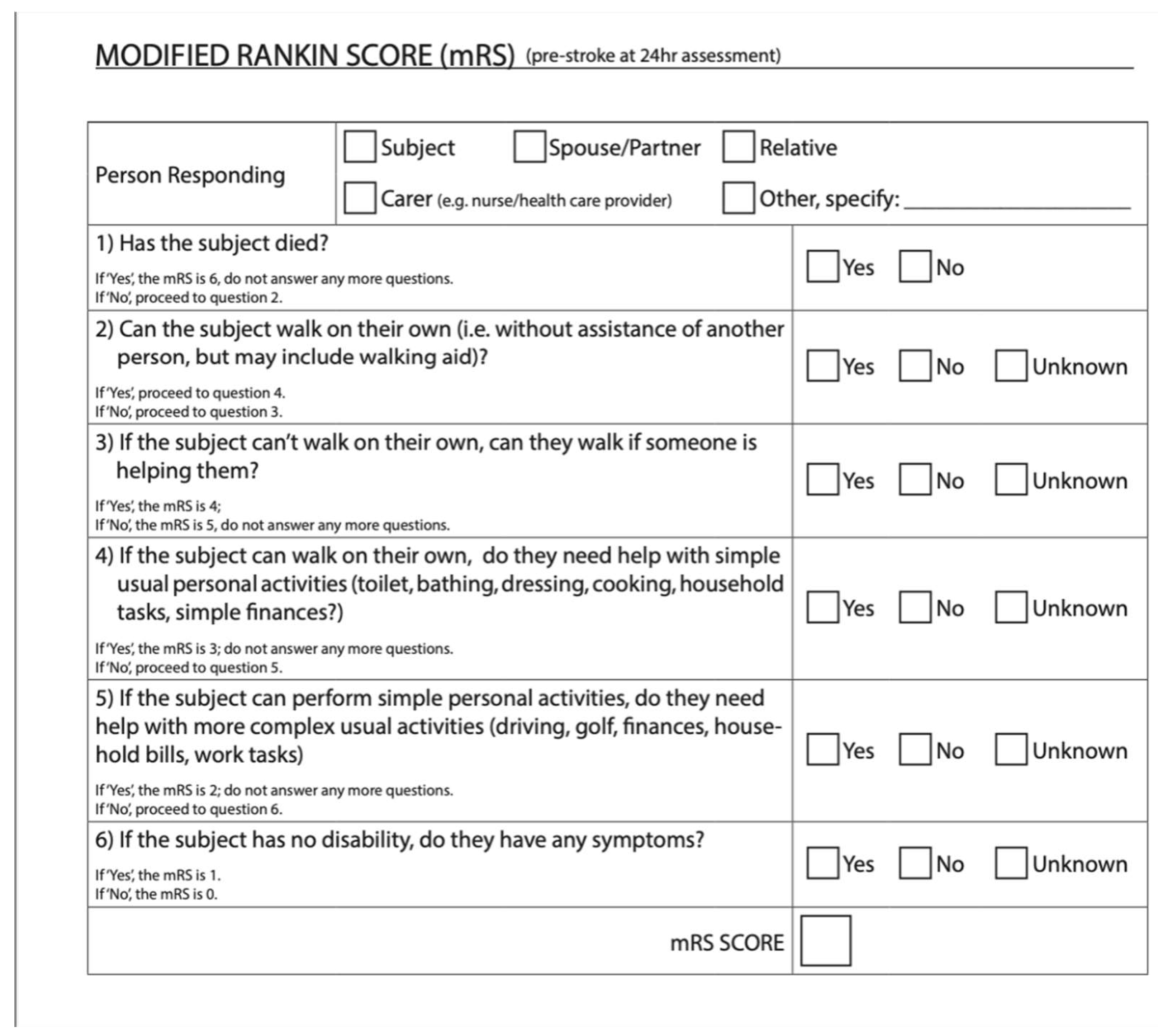

Figure 2 shows a questionnaire version of the mRS from the ESCAPE-NA1 stroke trial [

8]. These are just two examples of a questionnaire and definitions for the mRS used for outcome measures in stroke trials.

Current modified Rankin Scale Collection Process

There are currently several ways to administer the mRS. Besides the defined grades on the scale (

Figure 1 &

Figure 2), there is no technical standardization. The mRS is mainly used for clinical trials in stroke, typically the administration of the mRS in clinical trials will have specifications for the way it should be administered based on the trial protocols. For example, the 2018

ESCAPE-NA1 trial used a structured questionnaire with a yes/no system beginning with the highest score 6 (see figure 2) [

9]. A second use of the mRS is during a follow up assessment. In this context the mRS is typically applied less rigidly than in clinical trials, here the mRS serves more as a guideline rather than a structured questionnaire. Clinicians may adapt their approach to include more probing questions and corroborative information sources to select the most accurate score to gauge their patient’s recovery and disability. Lastly, the mRS is at times administered in acute stroke assessments. Because of the multiple questionnaires, guidelines, and administrative methods for the mRS, there are no clear standardizations for scoring.

It’s clear there are ongoing challenges in the current administration of the mRS, contributing to the complex and variable decision-making process of clinicians scoring the mRS. During the assessment the decision-making involves three parts, firstly, understanding the range of choice options and courses of action. This involves recognizing the different levels of disability or recovery of the patient according to the clinician administering the mRS and then deciding on the most accurate score based on the patient. Second is forming beliefs about objective states, processes, and events, this includes outcome states and means to achieve them. This adds complexity in the assessment and scoring process from the vague and subjective nature of the current mRS categories leading to differences in interpretation across administrators. Lastly, decision-making considers the broader implications of the mRS score. Clinicians may implicitly weigh the assessment score for its impact on patient care, treatment plans, research, or healthcare system implications [

10]. These challenges highlight the need for a clinical assessment tool (CAT) that will standardize the administration of the mRS, reduce subjectivity, and improve scoring reliability while ensuring consistent application across both clinical and research settings.

Reliability of the Modified Rankin Scale

The lack of standardization in the mRS and its administration allows for interpretation leading to variability. This may be due to the cognitive load and individual decision-making the administrator may assume when scoring the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). For instance, biases towards scoring positively or negatively, routine exposure to stroke disability, or lack of corroborative information can result in discrepancies within scoring. Studies have shown that different medical professionals assign mRS grade differently. For example, one study found that physicians administering patients to rehabilitation wards tended to rate disability higher than neurologists discharging patients from a stroke unit [

2]. Multiple factors influence how a clinician interprets the administration process and scores of the mRS [

6] such as varying personal and professional influences, diverse sources of information, and subjective judgement. This variability has led to support for a more standardized administration process for the mRS. A 2023 study looked at the reliability of the mRS in stroke units and rehabilitation wards looked at the agreement between raters from each department. The study found an overall agreement of 70.5% (Kappa=0.55) [

2]. A 2007 study found improved inter-rater reliability using a structured questionnaire where the kappa value went from 0.56 to 0.78 and showed strong test-retest reliability (k=0.81 to 0.95). The 2007 study shows that structured interviews have been shown to improve inter-rater reliability and should be considered with helping in mitigating the levels of inter-rater variability [

1]. Ideally the kappa value for inter-rater reliability should be as close to 1 as possible. Creating a more standardized clinical assessment tool could mitigate these varied interpretations of the mRS across all settings and address the challenges currently faced by clinicians.

3. Methods: Online Survey

An anonymous online survey was conducted, targeting clinicians who administer modified Rankin Scale (mRS) from across Canada. The survey was conducted using Microsoft forms and had 12 questions with an option for additional feedback at the end. The survey was made up of both open and closed-ended questions, which included multiple choice, and binary questions with spaces to explain answers. To collect demographic information there was a question asking what the participants’ profession was, and how long they have been practicing. We then broke the professions down into specialties to gather more information. For example, if a participant selected physician, the next question would show several options for different types of physicians and an “other” option to select. The remainder of the survey asked participants about current uses, challenges, and opinions of administering the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). To keep all answers anonymous and organized all participants were randomly assigned a number through Microsoft Forms. Recruitment was done via email; there was an email sent out through the Canadian Stroke Consortium briefly explaining the online survey with a link attached. Ethics was obtained from Dalhousie's Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (REB#: 2024-7443). The survey was anonymous, and consent was ensured through a comprehensive document prior to starting the survey. Participants who did not consent were not able to participate in the survey.

4. Results: Online Survey

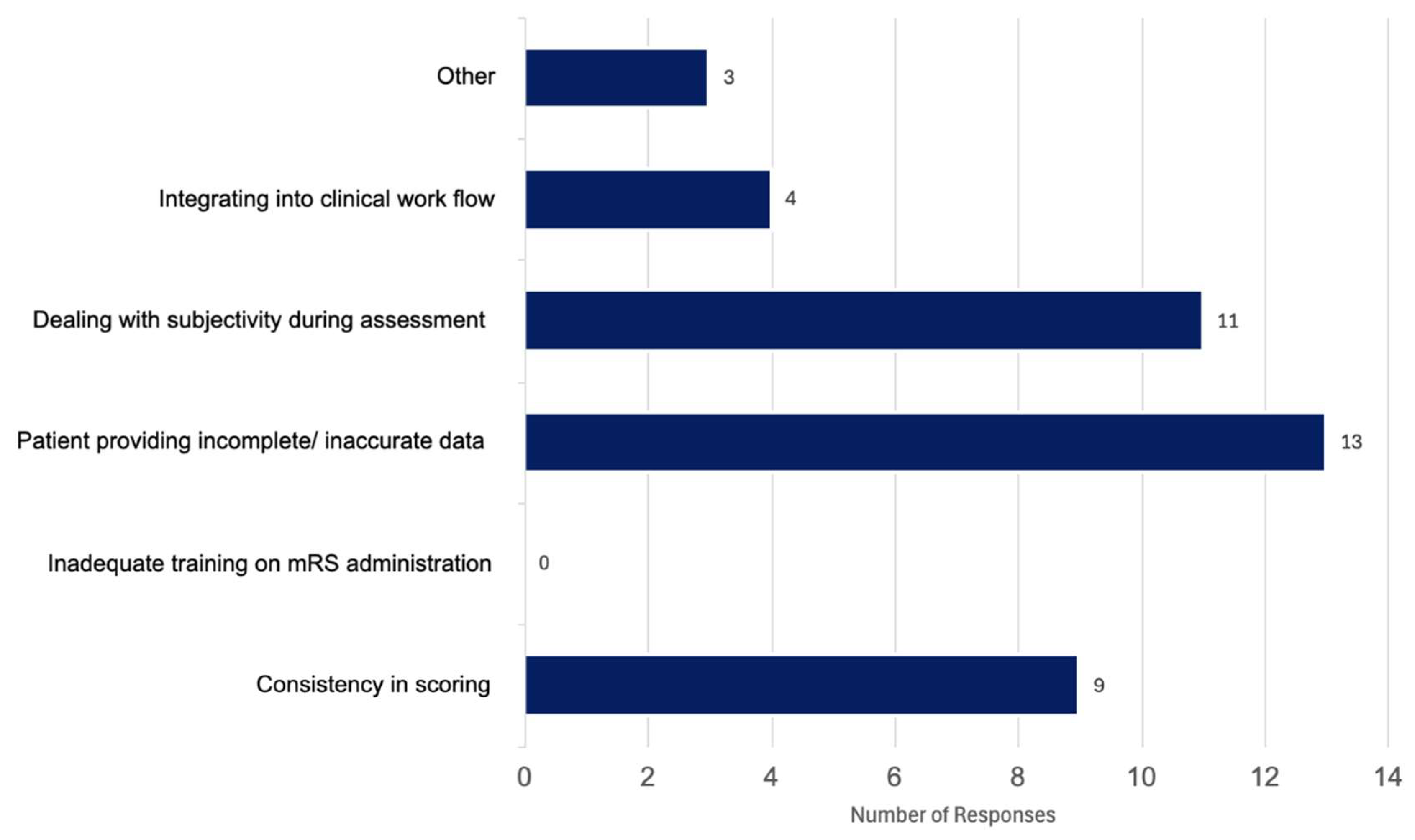

The survey was completed by 20 participants which is significant because there are 25 hospitals in Canada that participate in stroke trials, thus regularly collect 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Of the 20 participants, 12 were neurologists, five were nurses and three were stroke coordinators (not nurses). All participants were familiar with administering the mRS, where 55% used it weekly, 25% said they use it daily and 20% responded with using it either monthly or rarely. When asked about context of use, 50% of participants said they used it for clinical trials, 27.5% for follow up assessments, and 22.5% for acute stroke assessments. When asked about the main challenges faced when administering the mRS, 32.5% selected patients providing incomplete and or inaccurate information, 27.5% said dealing with subjectivity during the assessment was a significant challenge in administering the mRS, 22.5% of participants stated consistency of scoring to be an issue, 10% said integrating the mRS into clinical workflow was a significant challenge. Three participants (7.5%) selected “other”, two responded by indicating there were no challenges, and one participant commented on how the scale is “inadequate” (

Figure. 3). When asked to elaborate on their answers we found that the main comments were about how standardizing the mRS and integrating it into workflows could improve consistency. Two participants mentioned the assessment was straight forward while the rest emphasized the need for a structured tool to ensure accurate scoring, while still mentioning external factors such as caregiver burden, patient safety and cultural background as holding challenges for administration. When asked if participants found the current mRS measure to be effective in capturing patient outcomes we found 40% of participants said yes, 35% said no and 25% selected other. All participants who chose “other” commented on how it can be helpful at times, although noted the crudeness of the scale indicating it does not capture a patient’s full recovery, for example,

“Patient function can vary due to stroke symptoms and comorbidities; factors such as fatigue or depression may lead to lower scores”

“The tool is considered helpful, but is a crude measure that doesn't adequately account for cognitive status”

” The tool is easy to administer, but provides only a broad measure of recovery”

” The tool is generally effective until patients reach a level of independent functioning, at which point important nuances in recovery and disability can be lost”

“ The tool sometimes reflects patient needs, but many important aspects are not captured by the mRS, limiting its ability to fully represent patient outcomes”.

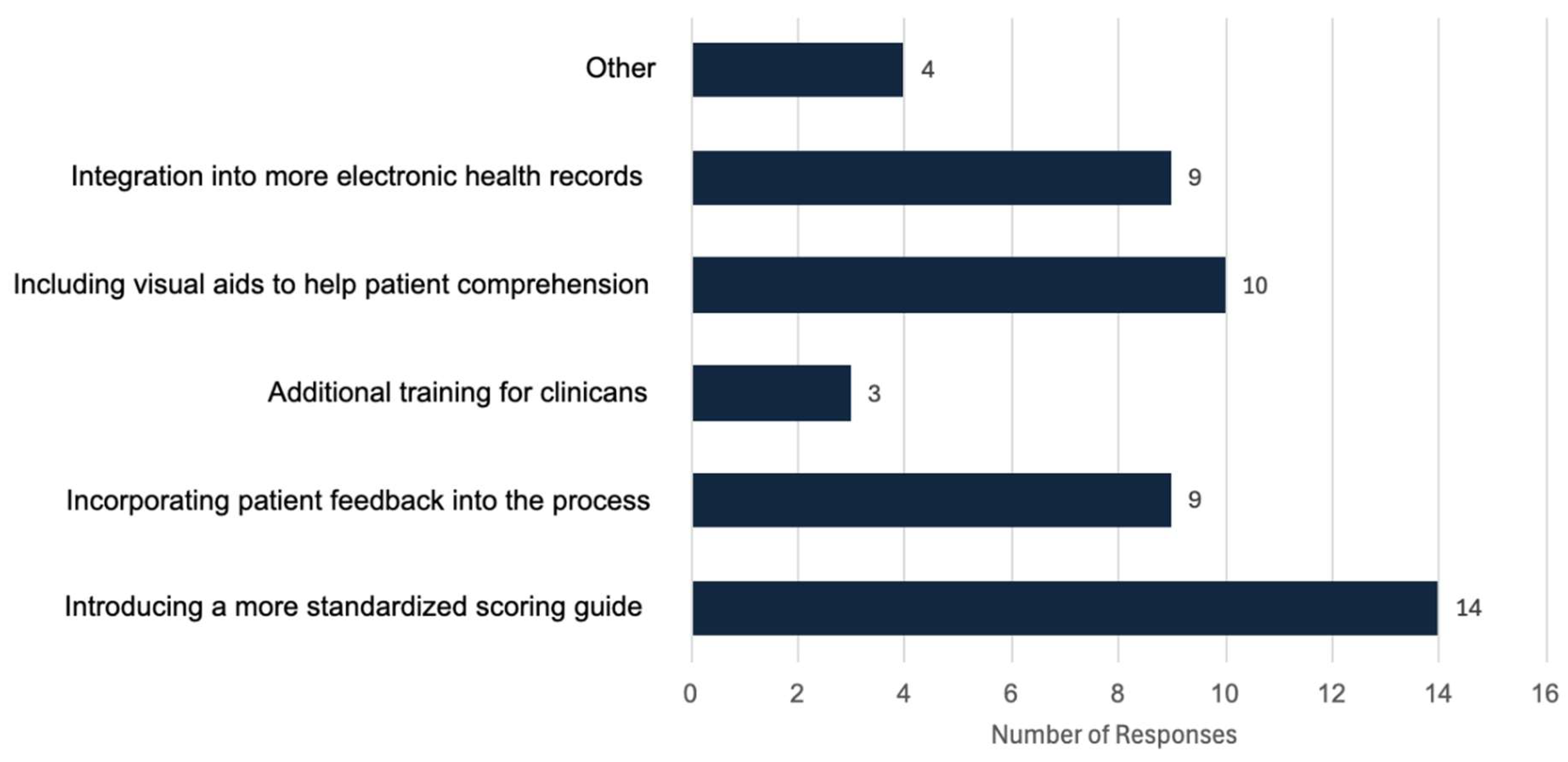

In response to how participants thought the mRS could be improved for both clinicians and patients (

Figure 4.). Here we found 28.6% responded introducing a more standardized scoring guide, 20.41% said including visual aids to help patient comprehension, 18.37% said incorporating patient feedback into the process, 18.37% chose integrating the mRS into more electronic health records would be beneficial, 6.12% said additional training for clinicians and 8.16% chose “other”. Responses under other included,

“Changing to another similar scoring system that reflects more of the issues faced”

“Frequently, patients' caregiver, or family members need to administer it [the mRS] for objectivity, and the current mRS is very limited in capturing all needs, AI may be helpful”

” Redevelopment to capture more nuance or maybe collaborations with other existing tests”.

5. Designing an mRS Collection Tool: Principles for a Clinical Assessment Tool

Clinical assessment tools (CATs) are designed to support healthcare delivery through standardization and simplification in the evaluation process, focusing on the ease and reliability of the tool. Clinical assessment tools aim to improve the assessment process, creating and maintaining consistency and reducing subjectivity during the administration. The main goal is providing a structured framework to collect, organize and interpret assessment data in an accurate and reliable way across all settings.

Research highlights the importance of standardizing clinical tools to reduce variability and enhance reliability. For example, one review explored the use of Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSSs) a type of clinical assessment tool that focuses on decision making. The review found that CDSSs can improve clinician adherence to guidelines, but their impact on patient outcomes remains inconsistent. While some studies have shown significant benefits, overall effectiveness of CDSSs in clinical practice is difficult to determine due to limited research on patient outcomes [

11]. However, these findings highlight the importance of developing and evaluating structured clinical tools, such as CDSSs and CATs, which have the potential to enhance clinical workflows and decision-making [

11].

These findings support the need for Clinical Assessment Tools (CAT) that can optimize the assessment process in tools such as the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) that requires careful, consistent, and reliable scoring between clinicians and clinical settings. Important aspects of a CAT for the mRS need to account for usability and standardization. A CAT should include features to reduce subjective judgment and cognitive load while administering the mRS. Cognitive load refers to the mental effort required to process excess information that competes for the limited cognitive resources available creating a burden on our working memory which can affect the accuracy of the clinical assessment [

12].

6. Design Principles for a Clinical Assessment Tool for the modified Rankin Scale

To improve the consistency and usability of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), we propose a Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT) designed using principles from Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), cognitive engineering, and established usability heuristics. The CAT should guide users through the mRS assessment using a structured process that will include unambiguous questions, and a comprehensive scoring guide that will lead to the existing mRS grades. Grounded in evidence-based guidelines, the tool should intend to reduce subjective interpretation and increase the inter-rater reliability streamlining decision-making. The design of the CAT is guided by core principles aimed at reducing cognitive load and ensuring a seamless user experience. These principles prioritize usability, efficiency, and accessibility to support clinicians and patients in accurately assessing post-stroke recovery across all settings [

13].

Clarity & Learnability

The Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT) should be easy to understand and require minimal training. A straightforward and intuitive interface will ensure clinicians and patients can quickly and confidently learn how to use the tool. This is important because this CAT is a new variation of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). The tool should ensure fast onboarding and intuitive use, so users become proficient and can easily integrate it into existing clinical flow. Key design elements to enhance learnability include: a simple and intuitive layout, guided by a straightforward step by step process. To support learnability, the tool needs a simple layout, and a clear and concise structure so users can easily scan and understand each page [

14]. Having a clear visual hierarchy is important, breaking down the information into distinct sections such as title, question, options will allow users to instantly separate and understand the relevant information of each section on the page allowing for easier focus [

14]. Each page or section should discuss one area of disability at a time so there is no overlap and reduces confusion when gathering information, such as separating daily tasks and mobility into separate sections. This structure will help reduce ambiguity between the lower mRS grades by incorporating more domain-specific questions. To support user's understanding and reduce cognitive load, design decisions should prioritize a simple layout, plain language, and include both visual and text cues to help guide users through each step without making the user feel overwhelmed.

Efficiency & Minimal Cognitive Load

The Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT) should be designed to be time-efficient, minimizing unnecessary steps and optimizing the process for fast completion while maintaining accurate data collection. Each interaction should have a purpose, to help in minimizing unnecessary steps and distractions minimizing the amount of information users' need to process. Making the CAT read from upper left to bottom right to align with how majority of users read on and offline is an important step for minimal cognitive load, and easy scanning [

14]. Using simple visualizations that are easily interpreted by the user, for example basic icon style images of people representing textual cues will help enhance decision-making by providing clear, quick visual cues to help the users select the appropriate option. Reducing cognitive load through having the questions independent of each other either on different pages or separated visually will reduce the mental effort required for the user to understand and process the information. Making sure the questions and options in the CAT are binary and close ended is important to allow for users to select options with minimum cognitive effort. Similarly, structuring the CAT questions in ascending order from least to most severe disability will support more deliberate decisions making to choose the most appropriate response, this will allow users to move on faster to the next question. Cognitive effort should be reduced by structuring information in a logical flow, presenting only essential content at each step and maintaining a consistent interaction model where users perform similar actions on all screens to reduce decision fatigue and ensure less cognitive pressure. To further reduce cognitive load during an mRS scoring, having a CAT with automated scoring is crucial to reduce any human error and lessen any scoring biases.

Consistency & Error Prevention

Ensuring the Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT) has a predictable and structured interface will enhance usability and reduce the likelihood of errors. Having clear navigation and ensuring interactions are consistent will help to create an intuitive user experience

. Having built-in error preventions, such as having clear choice indicators so that users are only able to choose one option per question. The user's choice should be clearly highlighted so that they know exactly which option they have selected, further there should be error prevention in place for choice selection, so users know they are only allowed to select one option. For example, if a user tries to select a second option after their first is bolded and selected the second option could immediately feedback by briefly shaking or display an animation to indicate only one selection is allowed. Error prevention should be used by having a confirmation dialogue box pop up before submitting will give users a chance to review their answers and make sure they are confident about their responses, which will help build confidence and reduce mistakes [

14].

Accessibility & Inclusivity

The Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT) should be accessible to a wide range of users, including those with visual, motor, or cognitive impairments. The tool should be easy for all clinicians to use and ideally support collaborative use for both clinicians and patients. Design decisions should prioritize readability

, by using clear direct language, large legible fonts and a layout that guides users through the interface with minimal cognitive effort. Having clear simple visuals that match the text cues will help with comprehension and support more accessible decision-making during choice selection. Having an intuitive uncluttered interface will help further accommodate user’s needs. Any use of colour should prioritize contrast for easy detection to all users, avoiding combinations that are indistinguishable to colour blind users [

14]. Simplified interactions and error-prevention strategies will ensure that users of all abilities can complete the assessment with ease. Furthermore, including a more holistic approach to what encompasses an mRS score is at the forefront of accessibility and inclusion, for example adding in categories such as cognition or communication in the CAT would help capture a more realistic understanding of recovery after stroke. These domains are underrepresented in the current mRS scoring but impact a patient's function and recovery making their inclusion in the assessment critical for equity and accuracy. This would in turn allow for a more meaningful and accurate mRS score.

User Satisfaction & Engagement

Making sure the Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT) creates a positive user experience will increase usability. The CAT should be designed to feel intuitive to use making the user feel in control during the process. Making the CAT familiar will help with ease of use, following an intuitive route will lessen the need for attention and short-term memory use creating a more pleasant and comfortable user experience [

14]. Ensuring the CAT is responsive is key for user satisfaction, making sure to have ways to keep the user informed such as adding in page numbers, and progress indicator are a good way to show active responsiveness to the user [

14]. Having a progress indicator to help reduce uncertainty and show users their progress in the tool is important while having an intuitive flow that makes users feel in control will increase user satisfaction and autonomy while using the tool. Having an immediate scoring and an explanation of results will reinforce trust in the system while ensuring users understand their outcomes. Having a thank you message with a simple intuitive layout will also help contribute to a more satisfying user experience.

7. Impact

Through creating a clinical assessment tool (CAT) for the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) grounded in human computer interaction principles (HCI) and cognitive engineering principles we aim to reduce variability in the administration and scoring. By reducing cognitive load and mitigating cognitive biases during administration the tool will help increase inter-rater reliability. Through focusing on usability, simplicity, and standardization the assessment tool will help guide clinicians through a structured and intuitive process for administering the mRS. A standardized clinical assessment tool for the mRS could significantly enhance the efficiency and accuracy of clinical workflow in several ways. First, it would create a standardized administration and scoring process across all clinical and research settings, reducing inconsistencies throughout administration. This would lead to more consistent patient care and improved reliability of the mRS as an outcome measure which can help lead to a more uniform patient care process. Additionally, it could influence treatment approaches as reflected in clinical trials using mRS as an outcome measure. Second, a standardized clinical assessment tool would help streamline the assessment process by providing structured and standardized protocol, reducing administrative burdens associated with administering the mRS. Through using principles focusing on reducing cognitive load and HCI for the design of a standardized clinical assessment tool for the mRS, we can enhance the way the mRS is used across all settings, creating a new standard for reliability and effectiveness in patient assessments.

8. Discussion

In this paper we outline the potential advancement of modified Rankin Scale (mRS) administration using a Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT) that supports administrators' decision-making processes with minimal cognitive burden. The CATs user-centric design, focusing on learnability, efficiency, reliability, and satisfaction, serves as the cornerstone for improved inter-rater reliability. The design choices, including clear navigation, and immediate feedback mechanisms underscore the potential of the CAT to become an indispensable tool in stroke assessment.

While this paper lays a foundation for design principles of a CAT, ongoing research and development are crucial. Subsequent phases will include user testing with real-world clinical teams, further refinement of the system based on user feedback, and the examination of its impact on clinical outcomes. As mRS scoring becomes more standardized, the stroke care community can expect more consistent and accurate assessments, ultimately leading to improved patient care and more reliable clinical research data. This tool also introduces the potential for exploration of a patient-completed mRS. Creating a CAT using these design principles allows for a more intuitive and straightforward way to administer the mRS. If we can use these design principles to support clinicians, why not take it a step further and explore a firsthand approach that allows stroke survivors to assess their own disability as part of the recovery process. This would lead to not only more data, but more first-hand data collected by stroke survivors or caregivers who are experiencing recovery firsthand.

Future Direction

Next steps and future directions are to take the design principles and create an actual user interface for the Clinical Assessment Tool (CAT). The user-interface of this tool will complement existing electronic health records and tools while providing interactive guidance throughout the assessment, helping gather information and decision-making. This process of validation and standardization, informed by multi-center trial outcomes, aims to elevate the CAT to become a benchmark tool across healthcare settings.

5. Conclusions

This paper has provided an in-depth analysis of the current application of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) in clinical settings and the identified need for standardization in its administration. We have explored the historical context, a brief evolution of the mRS, and the challenges faced due to its interpretative nature leading to inter-rater variability. It is evident that the integration of a Clinical assessment tool (CAT) informed by Human Computer Interaction (HCI) principles would be beneficial to enhancing the reliability and accuracy of mRS assessments. The implementation of a CAT aligns with the cognitive workflow of clinicians, offering an intuitive user experience. This would address the cognitive load concerns and individual decision-making processes that contribute to variability in mRS scoring. A well-designed CAT informed by HCI could significantly reduce variability in mRS interpretation, leading to improved patient outcomes and more accurate data for stroke research and quality of assessments.

Author Contributions

Laura London (LL) completed the study design, data collection, and initial writing for the manuscript. Noreen Kamal (NK) completed supervision, funding acquisition and manuscript review.

Funding

Funding for this work is provided by an NSERC Alliance grant, (Title: Designing and Deploying a National Registry to Reduce Disparity in Access to Stroke Treatment and Optimise Time to Treatment, PI: Noreen Kamal).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The online survey for this study was conducted in accordance with the Tri-Council Policy StatementEthical Conduct for Research Involving Humans and approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board of Dalhousie University (REB#2024-7443, December 12 2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| mRS |

Modified Rankin Scale |

| CAT |

Clinical Assessment Tool |

References

- Banks, J. L., & Marotta, C. A. (2007). Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke, 38(3), 1091–1096. [CrossRef]

- Pożarowszczyk N, Kurkowska-Jastrzębska I, Sarzyńska-Długosz I, Nowak M and Karliński M (2023) Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale in clinical practice of stroke units and rehabilitation wards. Front. Neurol. 14:1064642. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Collier, J. M., Quah, D. M., Purvis, T., & Bernhardt, J. (2010). The Modified Rankin Scale in Acute Stroke Has Good Inter-Rater-Reliability but Questionable Validity. Cerebrovascular Diseases (Basel, Switzerland), 29(2), 188–193. [CrossRef]

- Zeltzer, L. (2008, April 19). Modified Rankin scale (MRS). Stroke Engine. https://strokengine.ca/en/assessments/modified-rankin-scale-mrs/#Purpose.

- Quinn, T., Dawson, J., & Walters, M. (2008). Dr John Rankin; His Life, Legacy and the 50th Anniversary of the Rankin Stroke Scale. Scottish Medical Journal, 53(1), 44–47. [CrossRef]

- Rethnam, V., Bernhardt, J., Johns, H., Hayward, K. S., Collier, J. M., Ellery, F., Gao, L., Moodie, M., Dewey, H., Donnan, G. A., & Churilov, L. (2021). Look closer: The multidimensional patterns of post-stroke burden behind the modified Rankin Scale. International journal of stroke: official journal of the International Stroke Society, 16(4), 420–428. [CrossRef]

- Cumming School of Medicine. (n.d.). ESCAPE Stroke. University of Calgary. https://cumming.ucalgary.ca/escape-stroke.

- Goyal, M., Demchuk, A. M., Menon, B. K., Eesa, M., Rempel, J. L., Thornton, J., Roy, D., Jovin, T. G., Willinsky, R. A., Sapkota, B. L., Dowlatshahi, D., Frei, D. F., Kamal, N. R., Montanera, W. J., Poppe, A. Y., Ryckborst, K. J., Silver, F. L., Shuaib, A., Tampieri, D., … Hill, M. D. (2015). Randomized Assessment of Rapid Endovascular Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(11), 1019–1030. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M. D., Goyal, M., Menon, B. K., Nogueira, R. G., McTaggart, R. A., Demchuk, A. M.,. .Graziewicz, M. (2020). Efficacy and safety of nerinetide for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke (ESCAPE-NA1): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 395(10227), 878-887. [CrossRef]

- Patel, V. L., Kaufman, D. R., & Kannampallil, T. G. (2013). Diagnostic Reasoning and Decision Making in the Context of Health Information Technology. Review of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 8(1), 149–190. [CrossRef]

- JOHNSTON, M. E., LANGTON, K. B., HAYNES, R. B., & MATHIEU, A. (1994). Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on clinician performance and patient outcome : a critical appraisal of research. Annals of Internal Medicine, 120(2), 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.L., Kaufman, D.R., Kannampallil, T. (2021). Human-Computer Interaction, Usability, and Workflow. In: Shortliffe, E.H., Cimino, J.J. (eds) Biomedical Informatics. Springer, Cham. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.dal.ca/10.1007/978-3-030-58721-5_5.

- Lidwell, William., Holden, Kritina., & Butler, Jill. (2010). Universal principles of design: 125 ways to enhance usability, influence perception, increase appeal, make better design decisions, and teach through design (Revised and updated.). Rockport Publishers.

- Johnson, J. (2014). Designing with the mind in mind : simple guide to understanding user interface design guidelines. Morgan Kaufmann.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).