Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

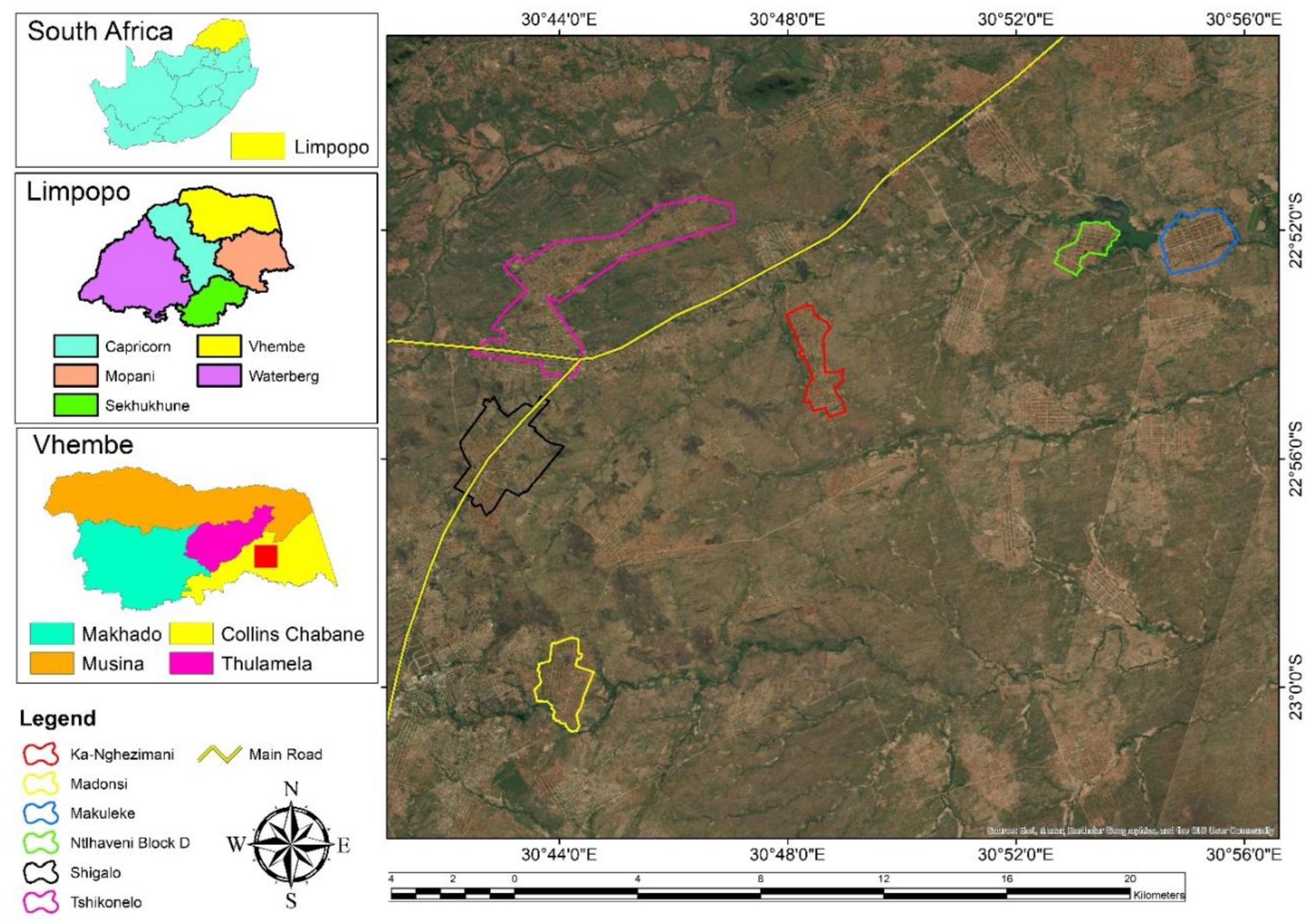

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Paradigm and Theoretical Framework

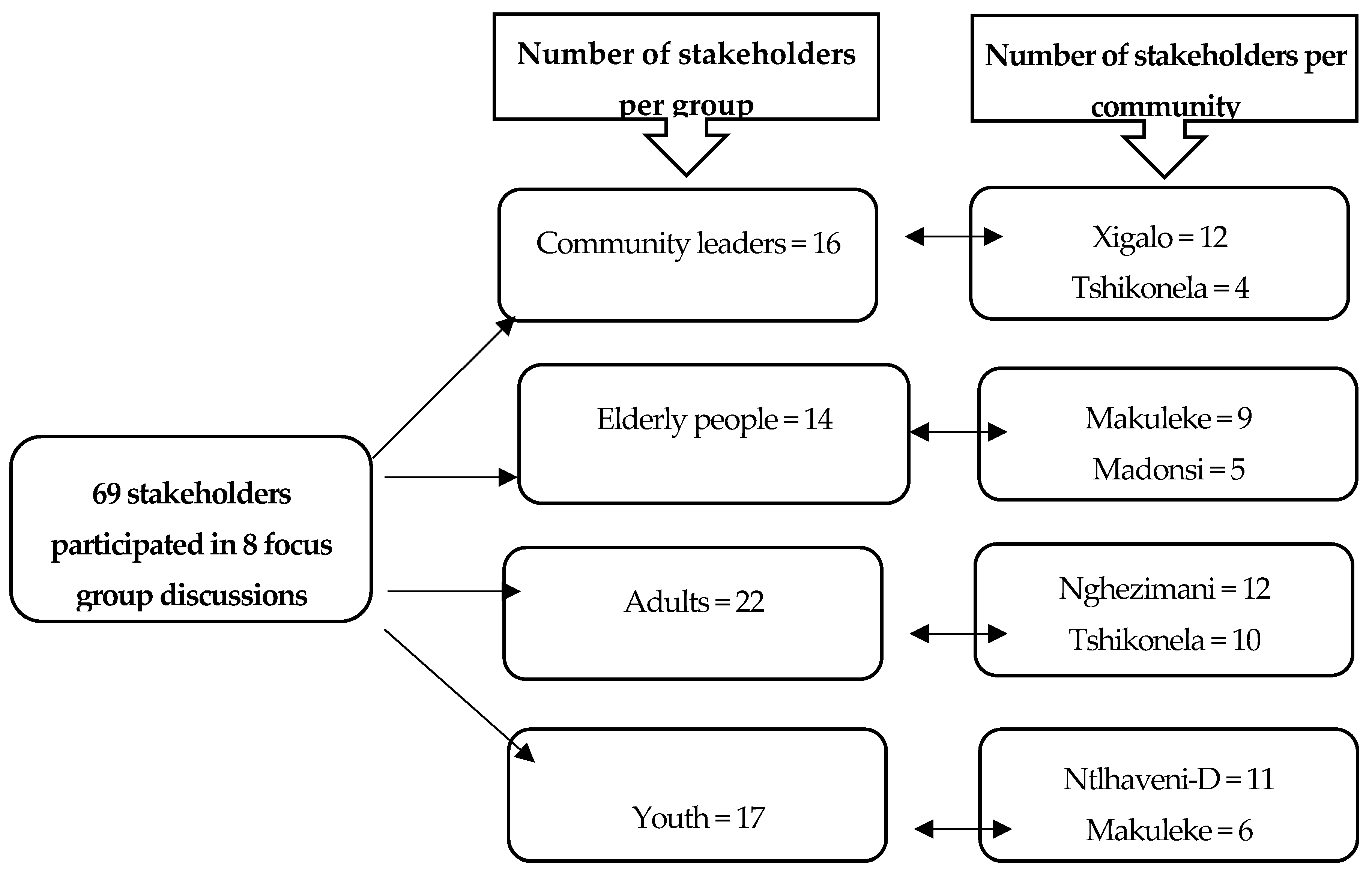

2.3. Population and Sampling

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Trustworthiness

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Stakeholders' Perceptions of the Availability and Accessibility of Water

"Water unavailability is due to illegal connections from the main water pipe to individual households, bypassing the community reservoir. On days when municipal water is available, only those with such connections have access to water, leaving others without. Furthermore, the leaking reservoir exacerbates the situation. On the side where I am residing, it has been nine months without water, and I have to rely on households fortunate enough to have water. Sometimes, I have to wait for them to finish using the tap before I can access the water. I am unsure who is responsible for fixing the reservoir from the Tribal Authority" (TS-A04).

"Municipal water is available once or twice per month, and its availability is not uniform across the entire community. We often alternate with neighbouring communities to secure access" (SH-E02). Other participants in the same group supported this sentiment.

"Our water shortage issues began when we started alternating access to water with neighbouring communities. Back in the days of the old Gazankulu government under Ntsanwisi's leadership, we had daily access to water. However, even when the Nandoni dam is full, water distribution to different communities happens at varying times. Unfortunately, on the days we are supposed to receive water, it is often not accessible" (XG-L02).

"It has been observed that water no longer reaches the community reservoir; instead, it goes directly from the pump to communal taps, leaving some taps still dry. People channelled water to the sides of the residence. To ensure that water is distributed to all taps, the community decided to contribute R2 per household to buy padlocks for water control points in order to prevent unauthorised access and ensure fair water distribution, ultimately helping people to access water without struggling" (MK-Y02).

"People from other areas within the community still find themselves travelling long distances to get water. Availability and access to municipal water are irregular. Nevertheless, a scheduling system has been put in place to ensure the availability of water to neighbouring communities. When water is scheduled to be available in our community, it does not supply all areas" (NG-A01).

"I resorted to buying water from those with boreholes due to the unavailability of water within our proximity" (NG-A06).

"It is not easy to access municipal water in our community due to its unavailability. We rely on purchasing water from households with boreholes" (SH-E01).

"It's been three years since the water pipes were installed, yet there is still a shortage of water in our community. We have had to resort to hiring vehicles to fetch water from neighbouring communities" (XG-L04).

"Due to inconsistent water availability, we began alternating water access with neighbouring communities every two to three days. Since December 2021 and early January 2022, we have faced severe shortages, resorting to hiring vehicles to fetch water for drinking and cooking from communities with access to water while still using dam water for bathing and laundry" (MK-Y01).

"In our community, rainwater serves as our primary water source since municipal water is scarce and often unavailable for up to two weeks at a stretch. When it rains, it's a blessing as we can collect water. However, rainwater quality deteriorates quickly, so we purify it using salt and boiling methods instead of bleach, which we are not accustomed to. Rainwater is one of the water sources that is accessible to us when it is raining. Another source of water is a well" (TS-A01).

"Some households face extreme poverty and struggle to afford water. They resort to using water from the dam, which is contaminated due to waste dumping. Government intervention to assist these disadvantaged families would be greatly appreciated" (MK-E03).

"Every household in our community has a tap within the yard, except for those in newer residential areas. Currently, we have access to water, and if there is ever an issue, it is usually quickly resolved, ensuring water availability the following day" (NT-Y02).

“Concerning water services, we had a long history of struggle. Back in 1998/1999, we relied on water from the dam, and even before that, when we were children, community members used water from the dam and wells. Around the year 2000, communal pipes were installed; although I'm not sure of the water source, whether it was a borehole or not, the water was salty. Eventually, we had access to clean water, but then issues arose again, leading us to use water from the dam. However, since last week, we have not had any issues with water" (MK-Y06).

"Accessing water was challenging in the past, and we used to alternate with our neighbouring community every two days. After we had stopped alternating with them, we only had access to water twice a week. However, there came a time when we faced a prolonged period without water, and we struggled. Recently, our Counsellor worked diligently with one of the community members, resulting in us having access to water every day for the past two weeks" (MK-E02).

"We rely on salty water from the boreholes. Our cooking experiences are often diminished due to the lack of fresh water, resulting in our meals frequently lacking taste. When bathing, we must use foam baths for proper skin care" (NG-A3).

“In my area, there are non-functional water taps. The community decided to come together to repair the abandoned municipal borehole to meet our water needs. Despite our efforts, the borehole does not adequately supply water to the entire community” (NG-A05).

"Our community is facing a severe water shortage from the municipality, and its accessibility is relatively difficult. The boreholes erected by the previous homeland government are no longer functional, and there is no initiative to repair them under the current democratic government" (SH-E03).

"Among all the essential services, water delivery is crucial as it is a basic need, especially for cooking. There are eleven boreholes in our community, but none are operational. The government needs to repair these boreholes to ensure the community has access to water" (TS-A06).

"In our community, we often go for some period without water. And when we do get water, it is usually not clean. I wonder if this indicates a lack of proper purification or perhaps contamination from dirty tanks. I am not sure of the purification process on-site, so I am just speculating" (XG-L07).

“Rumours are circulating about the construction of a reservoir that supposedly will provide water to the communities once completed. However, this is not promising, and our trust has been lost” (XG-L01).

3.2. Stakeholders' Perceptions of Sanitation (Toilet) Facilities

"Residents in newly developed residential areas are given three months to build a toilet, and failure to comply results in fines from the Tribal Authority office. However, due to financial constraints, some prioritise other needs first" (MK-E06).

"I do not even have access to a toilet within my household, and I have resorted to using the bush, which is challenging for young children. I therefore dug a hole for children to help themselves, but the challenge comes when there is no water available for hand washing afterwards" (TS-A07).

"Back then, we used the bush to relieve ourselves, and it was unsanitary, and we did not realise the health risks. We did not have alternatives because the toilets were not available. Nowadays, not having a toilet can result in fines. To avoid penalties, some people quickly construct toilets, even if they are not in good condition, often due to poverty. Surprisingly, in other communities, the government builds toilets for every household through the RDP, which is not the case in our community. We would appreciate it if we could get such a service here as well" (MK-E02).

3.3. Stakeholders' Perceptions of Refuse Removal Facilities

"The government is wasting money because the appointed contractor for waste removal focuses solely on semi-urban areas (townships), neglecting their duties in rural communities. Consequently, within our community, people have designated specific areas for waste disposal, yet there are no waste collection vehicles. Some people dump trash, including used disposable nappies, in the bushes, posing severe hazards, especially during the rainy season when such debris is washed into the river, where livestock graze" (NG-A11).

"Waste dumping is also a problem near the dam, where some people discard their waste. This is particularly concerning as many of us fetch water from the dam for household use. The waste ends up polluting the water when it rains. While municipal vehicles are collecting refuse in other communities, we do not have any coming to collect refuse in our area. Despite promises of municipal waste collection, it never materialised. People continue to dump waste indiscriminately, including disposable nappies" (MK-E09).

"In our community, the level of service delivery regarding refuse removal is lacking, unlike what has been experienced in the township. Refuse removal vehicles only come once a month to collect waste, including disposable nappies, and there are often delays. I am unsure if the refuse collectors will wait for the designated refuse areas to fill up before collection. Along the roads, designated refuse areas were established when people started dumping trash anywhere. However, when the collection is delayed, these areas become full and emit unpleasant odours" (TS-L02).

"During the Gazankulu government era, every family was instructed to dig a dumping hole in their households, and there was a dedicated monitoring unit overseeing compliance. However, this practice was discontinued when the current democratic government promised to collect waste from the designated areas" (SH-E01).

3.4. Stakeholders' Concerns About WASH Service Delivery

"Reflecting on the availability of water for the past two weeks, I feel content, hoping it remains consistent. However, the lack of support for waste management is disappointing. Our area is becoming increasingly dirty, and we urgently need assistance" (MK-E05).

"In terms of water service delivery, we are content because water is available whenever we need it. However, our concern lies with sanitation services of refuse removal, as the unpleasant smell emitted is not suitable for our health" (NT-Y04).

"We are deeply dissatisfied with the services we are getting because they are causing infections. The lack of access to clean, safe water leads to the spread of infectious diseases, and inhaling polluted air due to environmental contamination is not healthy either. The government needs to take action to protect our health as a community for a better quality of life" (XG-L05).

"The government needs to prioritise providing essential services to the people, considering that we are the ones directly affected. Lack of sanitation services, such as toilet facilities and refuse removal, pollute the environment and put our health at risk. We respectfully urge the government to fulfil its duty to the people by ensuring effective service delivery" (NG-A05).

"We are not pleased with the service we are provided. It feels like this government is taking advantage of us, only showing interest during elections to secure our votes and positions in office. Once elections are over, they forget about us and focus on their own life" (XG-L11).

"The pace at which our government renders services is slow and is hindered by political conflicts. It is so irritating that during election periods, promises of improved service delivery are made, and some individuals even resort to bribery to secure votes. However, when the time comes for actual service delivery, progress is slow, and essential needs remain unmet" (NG-A01).

3.5. Proposed Acceptable, Appropriate and Feasible Intervention Strategies to Improve WASH Service Delivery

3.5.1. Acceptable WASH Intervention Strategies

"Coming up with intervention strategies is the responsibility of the municipality. As community members from the Tribal Authority office, our role is to communicate our concerns to the municipality. Despite submitting recommendations, we are still waiting for service delivery regarding water sources, distribution, and supply. In the meantime, we can only implement temporary intervention strategies. For instance, acquiring water tanks could help alleviate the situation, especially for boreholes lacking pumps. If we could obtain these pumps and connect them to the boreholes, we would have a more reliable water supply" (TS-L01).

"I believe that maintaining the old pipes could alleviate the water shortage crisis. Additionally, installing pressure pumps on the tanks could ensure that water reaches all parts of the community. It seems the government has overlooked the fact that the population is growing; the current pipes only serve the previous population size. Surveys should inform them of population growth and household expansion" (XG-L01).

"For the government to address the water problem, it is necessary to repair the reservoir, which has been leaking for quite some time, resulting in water loss. Additionally, addressing blockages in the main pipes is crucial to ensure equitable water distribution to all communal taps. Proper maintenance of pipes and taps is essential for everyone's access to water" (TS-A09).

"The government ought to halt the tender process and instead provide services through relevant departments. This action would be necessary due to the corruption in the tender system, leading to instances where poor-quality materials are used. For example, the Department of Public Works could be responsible for rendering most services" (NG-A02).

"It would be beneficial to fix the boreholes in all sections and educate the community about conserving our resources to alleviate water struggles" (TS-L04).

"When skip bins are provided, it is necessary to inform the community members and educate them on proper refuse disposal practices. Additionally, people should refrain from littering along the way. Some individuals do not put much effort into cleaning their yards, resulting in mixed-up dirt. Therefore, receiving workshops on environmental care and personal hygiene is crucial" (MK-Y06).

3.5.2. Appropriate WASH Intervention Strategies

“A temporary solution for ensuring water availability is to repair the boreholes and install pumps. Additionally, the municipality should provide water tanks for emergencies” (TS-L02). However, the installation of water tanks was objected to, “It would not be appropriate for the municipality to provide water tanks because there are already standpipes within our yards. According to government rules and procedures, water tank services are only offered to areas without standpipes” (TS-L03).

"Regarding sanitation services, it would be better if the government could provide temporary mobile toilets for those without toilet facilities. This measure would contribute to maintaining a clean environment, ultimately promoting better health outcomes for us" (NG-A02).

"Some households are unable to build latrines due to poverty, and the government must assist in such cases. The government should offer support through the RDP, although the selection criteria are not clear at times. In other communities, there is no selection process, and toilets are built for everyone, regardless of whether they have existing toilet facilities. Access to such services would be beneficial for us, too" (MK-Y02).

3.5.3. Feasibility of Proposed WASH Intervention Strategies

3.5.4. Government's Commitment and Accountability

“I believe that all the intervention strategies we discussed could potentially work. However, given the current state of service delivery, I am uncertain. While anything is possible, there seems to be a lack of willingness from the municipality to provide services to the people. If you watch television or listen to the radio, you will see that poor service delivery is a problem across South Africa. Our government leaders seem to prioritise their interests. In this situation, we may or may not agree because many of the things we had been promised did not materialise" (XG-L02).

"The government is not failing; it is actively choosing not to act. If they were interested, they could have provided the services they did in other communities. There are refuse removal vehicles available through the municipality, so why are they not being deployed to collect refuse in our community?" (MK-E05).

"The feasibility of these strategies depends on whether the municipality acknowledges our concerns. Remember, we elected these municipal officials, and if they want our votes again, they must heed our concerns and deliver on their promises" (TS-A01).

3.5.5. Availability of Resources

MK-E01: "I would not definitely say "Yes" it would be feasible or "No" it would not be feasible because it depends on the budget at the time. There is a possibility they might provide the services years later when we urgently require such services. Budget allocation plays a crucial role in prioritising tasks based on available funds."

"Service delivery would be possible only when the government demonstrates a sincere commitment to it. During the budgeting process outlined in the Integrated Development Plan (IDP), funds are allocated annually for water, roads, and other essential services. However, at the end of every financial year, nothing has been done. This leaves us questioning the whereabouts of the allocated funds and what has been accomplished with them" (NG-A04).

"There are enough refuse removal vehicles from the municipality. If only they could schedule a day in a week to visit our community for refuse collection, it would be immensely beneficial" (NG-A03).

3.5.6. Stakeholders’ Engagement and Collaboration

"I believe all the proposed intervention strategies could be feasible. As a community, we need to prioritise our concerns and submit them to the municipality. Each year, during the IDP meetings, the municipality offers a platform to discuss our concerns and provide necessary services. As we are living in a democratic South Africa, we can engage with various stakeholders and voice our concerns. However, it is imperative that our concerns are conveyed to the municipal office for action rather than just discussing them without any follow-up" (TS-A05).

"It would be essential for us to be educated so we gain the knowledge and skills necessary to care for the environment in which we reside effectively"(MK-Y04).

"Creating a community project for refuse removal would be beneficial, especially if we receive support from the municipality for waste collection" (MK-Y05).

"To achieve these intervention strategies, we should form a community group to monitor refuse disposal. This group will coordinate with the municipality to ensure the provision of skip bins. They would also report when the dumping site is full, prompting for collection" (NT-Y11).

"There was an Organisation called Adopt River, which was comprised of women. They used to collect refuse in our community. Unfortunately, the Organisation disbanded due to the government's failure to provide payment. If we could establish a similar Organisation, with the government supporting us, it would be immensely beneficial” (MK-E06).

4. Discussion

4.1. Availability and Accessibility of Water

4.2. Availability and Accessibility of Sanitation (Toilet) Facilities

4.3. Availability and Accessibility of Refuse Removal Facilities

4.4. Stakeholders' Concerns About WASH Service Delivery

4.5. Potential Proposed Intervention Strategies

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCLM | Collins Chabane Local Municipality |

| FDGs | Focus Group Discussions |

| IDP | Integrated Development Plan |

| NGOs | Non-governmental Organizations |

| PI | Principal Investigator |

| RDP | Reconstruction and Development Programme |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| VDM | Vhembe District Municipality |

| VIP | Ventilated Improved Pit |

| WASH | Water, Sanitation and Hygiene |

References

- WHO, UNICEF. 2021. Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: five years into the SDGs. Geneva, Switzerland. World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Abrams, A.L.; Carden, K.; Teta, C.; Wagsaether, K. Water, sanitation, and hygiene vulnerability among rural areas and small towns in South Africa: Exploring the role of climate change, marginalization, and inequality. Water 2021, 13(20), 2810. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special edition towards a rescue plan for people and planet. Rome, Italy, 2023, United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/.

- The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. In Blair’s Britain, 1997-2007 (May). [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2022: Provinces at a Glance. Pretoria, South Africa, 2023a, Statistics South Africa.

- https://census.statssa.gov.za/assets/documents/2022/Provinces_at_a_Glance.pdf.

- Cole, M.J.; Bailey, R.M.; Cullis, J.D.S.; New, M.G. Spatial inequality in water access and water use in South Africa. Water Policy 2018, 20(1), 37–52. [CrossRef]

- Odiyo, J.O.; Makungo, R. Water quality problems and management in rural areas of Limpopo Province, South Africa. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 164, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Makaya, E.; Rohse, M.; Day, R.; Vogel, C.; Mehta, L.; McEwen, L.; Rangecroft, S.; Van Loon, A.F. Water governance challenges in rural South Africa: exploring institutional coordination in drought management. Water Policy 2020, 22(4), 519–540. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Minimum quality standards and indicators for community engagement. New York, USA, 2020, United Nations Children’s Fund. https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/8401/file/19218_minimumquality-report_v07_rc_002.pdf.pdf.

- Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2021: Statistical release P0318. Pretoria, South Africa. 2022, Statistics South Africa. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11469378.

- Rankoana, S.; Mothiba, T. Water scarcity and women’s health: A case of Sagole community in Mutale Local Municipality, Vhembe District of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Dance 2015, 4, 738–744.

- Statistics South Africa. Limpopo community survey 2016. Statistical release 03-01-05. Pretoria, South Africa, 2018, Statistics South Africa.

- UNICEF. Action against hunger: WASH nutrition. A practical guidebook on increasing nutritional impact through integration of WASH and nutrition programmes. New York, USA, 2017. United Nations Children’s Fund. https://www.fsnnetwork.org/sites/default/files/acf_wash-nutrition-guidebook_2017-january.pdf.

- UNICEF; WHO. Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2022: special focus on gender. New York, USA, 2023, United Nations Children’s Fund.

- Devgade, P.; Patil, M. Water, sanitation, and hygiene assessment at household level in the community: A narrative review. J. Datta Meghe Inst. Med. Sci. Univ. 2023, 18, 173–177. [CrossRef]

- Department of Water and Sanitation. Annual report: 2022/2023 financial year, vote 41. Pretoria, South Africa, 2023.

- Statistics South Africa. General household survey 2022: statistical release P0318. Pretoria, South Africa, 2023b, Statistics South Africa.

- Mardis, M.A.; Hoffman, E.S.; Rich, P.J. Trends and Issues in Qualitative Research Methods. In: J.M. Spector et al. (eds.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. Springer 2014. [CrossRef]

- Schwandt, T.A. Three epistemological stances for qualitative inquiry: Interpretivism, hermeneutics, and social constructionism. 2000. In: Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds). Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd edition. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, California, USA; pp 189–213.

- Crotty, M. The Foundation of Social Research: meaning and perspective in the research process. 1st Edition. SAGE Publications: London, New Delhi, 1998.

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications: Beverly Hills, Califonia, USA, 1985.

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000, 30(3), 124–130. [CrossRef]

- Malima, T.P.; Kilonzo, B.; Zuwarimwe, J. Challenges and coping strategies of potable water supply systems in rural communities of Vhembe District Municipality, South Africa. J. Water Land Dev. 2022, 53, 148–157. [CrossRef]

- Matlakala, M.E.; Von Kallon, D.V.; Ncube, E.J. Designing an Alternate Water Security Strategy for Rural Communities in South Africa - Case Study of Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces. Procedia CIRP 2023, 119, 487–494. [CrossRef]

- Murei, A.; Mogane, B.; Mothiba, D.P.; Mochware, O.T.W.; Sekgobela, J.M.; Mudau, M.; Musumuvhi, N.; Khabo-Mmekoa, C.M.; Moropeng, R.C.; Momba, M.N.B. Barriers to Water and Sanitation Safety Plans in Rural Areas of South Africa—A Case Study in the Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Water 2022, 14(8), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- CCLM IDP. Collins Chabane Local Municipality: final integrated development plan 2022-26. Limpopo, South Africa, 2022; Collins Chabane Local Municipality.

- Osarfo, J.; Ampofo, G.D.; Arhin, Y.A.; Ekpor, E.E.; Azagba, C.K.; Tagbor, H.K. An assessment of the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) situation in rural Volta Region, Ghana. PLOS Water 2023, 2(5), e0000134. [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, J.M.M.; Schenck, C.J.; Volschenk, L.; Blaauw, P.F.; Grobler, L. Household Waste Management Practices and Challenges in a Rural Remote Town in the Hantam Municipality in the Northern Cape, South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5903. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, Z.; Reisner, A.; Liu, Y. Compliance with household solid waste management in rural villages in developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 293–298. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).