Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

27 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Plant-Based Diets

1.2. Benefits of Plant-Based Diets

1.3. Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Literature Search

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Profiling and Synthesis of Results

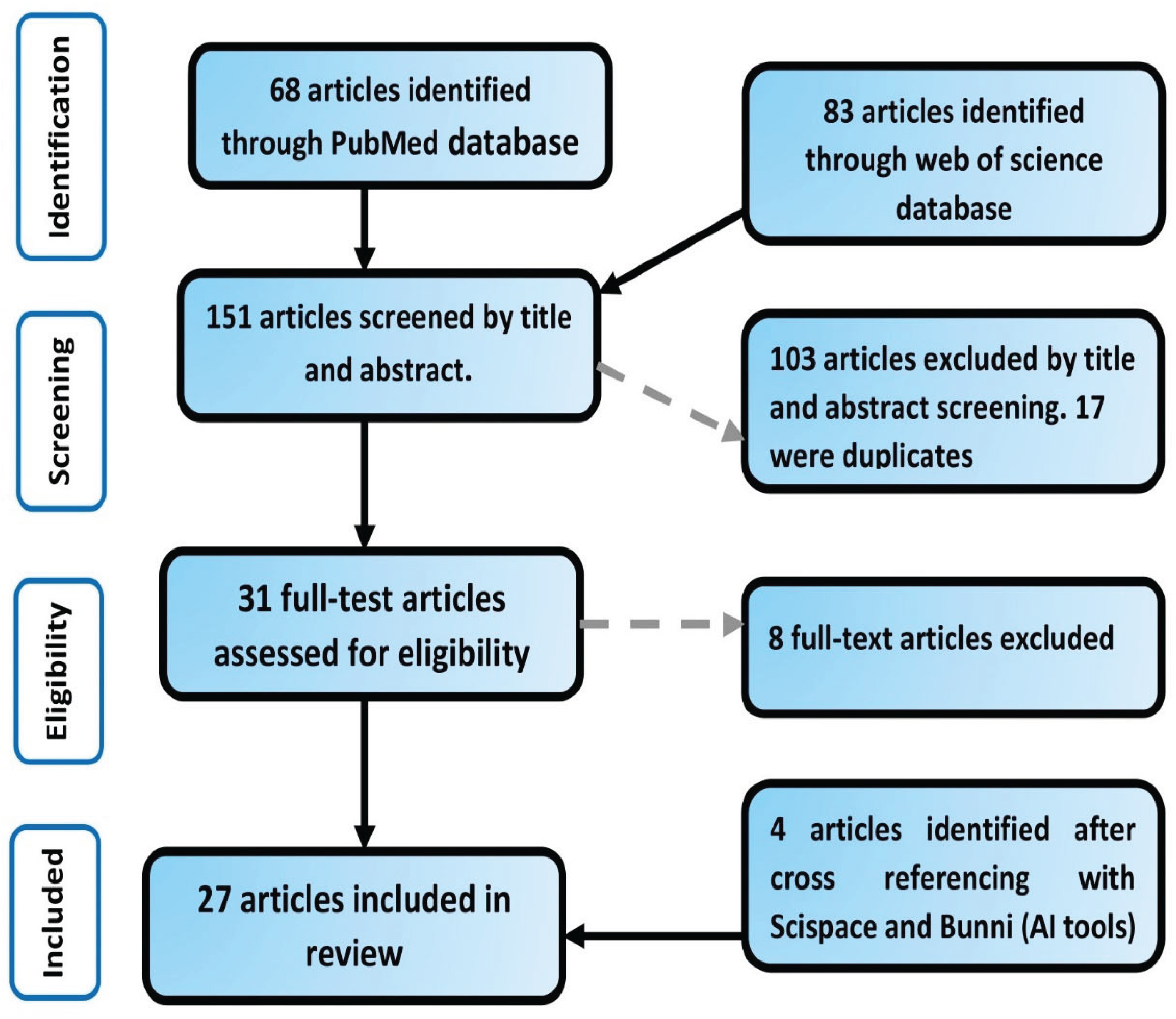

2.5. Article Search and Selection

3. Results

3.1. General Overview of Included Studies

3.2. General Overview of Health Professionals’ Attitudes and Perceptions

3.3. Factors Influencing Health Professionals’ Attitudes and Perceptions Towards Plant-Based Diets

3.3.1. Knowledge

3.3.2. Education and Training

3.3.3. Evidence-Based Guidelines

3.3.4. Multidisciplinary Collaboration

3.3.5. Personal Experience and Interest

3.3.6. Educational Resources

3.3.7. Lack of Time

3.3.8. Safety and Compliance Challenges

3.3.9. Lack of Confidence in Patient Capabilities

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBD | Plant-based diet |

| TDF | Theoretical Domains Framework |

| NIH | National Institute of Health |

| CDC | Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| AICR | American Institute for Cancer Research |

| DASH | Dietary Approaches to stop Hypertension |

| MD | Mediterranean diet |

References

- Regestein Q. R. (2018). The big, bad obesity pandemic. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 25(2), 129–132. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health [NIH] https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/healthstatistics/overweight-obesity, accessed 2/1/24].

- Skinner, A. C., Ravanbakht, S. N., Skelton, J. A., Perrin, E. M., & Armstrong, S. C. [2018]. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity in US Children, 1999-2016. Pediatrics, 141[3], e20173459. [CrossRef]

- Helmchen and Henderson, 2018 Helmchen, L. A., & Henderson, R. M. [2004]. Changes in the distribution of body mass index of white US men, 1890-2000. Annals of human biology, 31[2], 174–181. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2023]. Health, United States, 2021: Data brief [No. 456]. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db456.htm].

- Ward, Z. J., Bleich, S. N., Long, M. W., & Gortmaker, S. L. [2021]. Association of body mass index with health care expenditures in the United States by age and sex. PloS one, 16[3], e0247307. [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B., Egger, G., & Raza, F. [1999]. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Preventive medicine, 29[6 Pt 1], 563–570. [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, D. R., Morris, M. A., & Gambone, J. C. (2017). Obesity pandemic: causes, consequences, and solutions-but do we have the will? Fertility and sterility, 107(4), 833–839. [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund. [2018]. Summary of the third expert report: Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer. https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Summary-of-Third-Expert-Report-2018.pdf.

- Romanello, M., Di Napoli, C., Drummond, P., Green, C., Kennard, H., Lampard, P., Scamman, D., Arnell, N., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Ford, L. B., Belesova, K., Bowen, K., Cai, W., Callaghan, M., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Chambers, J., van Daalen, K. R., Dalin, C., Dasandi, N., Dasgupta, S., … Costello, A. [2022]. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet [London, England], 400[10363], 1619–1654. [CrossRef]

- Viroli, G., Kalmpourtzidou, A., & Cena, H. [2023]. Exploring Benefits and Barriers of Plant-Based Diets: Health, Environmental Impact, Food Accessibility and Acceptability. Nutrients, 15[22], 4723. [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T., Waite, R., Hanson, C., Ranganathan, J., Dumas, P., Matthews, E., & Klirs, C. [2019]. Creating a sustainable food future: A menu of solutions to feed nearly 10 billion people by 2050. Final report.

- The Rockefeller Foundation. https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/report/true-cost-of-food-measuring-what-matters-to-transform-the-u-s-food-system/ accessed 3/28/2024].

- Food and Agriculture Organization. [2021]. The state of food and agriculture 2021: A report on the future of food. https://www.fao.org/3/ca6640en/ca6640en.pdf [accessed on 28 March 2024].

- Dinu, M., Abbate, R., Gensini, G. F., Casini, A., & Sofi, F. [2017]. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 57[17], 3640–3649. [CrossRef]

- Toumpanakis, A., Turnbull, T., & Alba-Barba, I. [2018]. Effectiveness of plant-based diets in promoting well-being in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. BMJ open diabetes research & care, 6[1], e000534. [CrossRef]

- Chiavaroli, L., Nishi, S. K., Khan, T. A., Braunstein, C. R., Glenn, A. J., Mejia, S. B., Rahelić, D., Kahleová, H., Salas-Salvadó, J., Jenkins, D. J. A., Kendall, C. W. C., & Sievenpiper, J. L. [2018]. Portfolio Dietary Pattern and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Controlled Trials. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 61[1], 43–53. [CrossRef]

- Qian, F., Liu, G., Hu, F. B., Bhupathiraju, S. N., & Sun, Q. [2019]. Association Between Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine, 179[10], 1335–1344. [CrossRef]

- Rees, K., Takeda, A., Martin, N., Ellis, L., Wijesekara, D., Vepa, A., Das, A., Hartley, L., & Stranges, S. [2019]. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3[3], CD009825. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [n.d.]. FastStats: Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm.

- Springmann, M., Wiebe, K., Mason-D’Croz, D., Sulser, T. B., Rayner, M., & Scarborough, P. [2018]. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. The Lancet. Planetary health, 2[10], e451–e461. [CrossRef]

- Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., Garnett, T., Tilman, D., DeClerck, F., Wood, A., Jonell, M., Clark, M., Gordon, L. J., Fanzo, J., Hawkes, C., Zurayk, R., Rivera, J. A., De Vries, W., Majele Sibanda, L., Afshin, A., … Murray, C. J. L. [2019]. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet [London, England], 393[10170], 447–492. [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A., Finley, J., Hess, J. M., Ingram, J., Miller, G., & Peters, C. [2020]. Toward Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Current developments in nutrition, 4[6], nzaa083. [CrossRef]

- Kraak, V. I., & Consavage Stanley, K. [2023]. An economic lens for sustainable dietary guidelines. The Lancet. Planetary health, 7[5], e350–e351. [CrossRef]

- Consavage Stanley, K., Hedrick, V. E., Serrano, E., Holz, A., & Kraak, V. I. [2023]. US Adults’ Perceptions, Beliefs, and Behaviors towards Plant-Rich Dietary Patterns and Practices: International Food Information Council Food and Health Survey Insights, 2012-2022. Nutrients, 15[23], 4990. [CrossRef]

- Koutras, Y., Chrysostomou, S., Poulimeneas, D., & Yannakoulia, M. [2022]. Examining the associations between a posteriori dietary patterns and obesity indexes: Systematic review of observational studies. Nutrition and health, 28[2], 149–162. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, E. A., Appleby, P. N., Davey, G. K., & Key, T. J. [2003]. Diet and body mass index in 38000 EPIC-Oxford meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 27[6], 728–734. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, S. E., Nguyen, M., & Malik, V. S. [2022]. Association between adherence to plant-based dietary patterns and obesity risk: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme, 47[12], 1115–1133. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Y., Huang, C. C., Hu, F. B., & Chavarro, J. E. [2016]. Vegetarian Diets and Weight Reduction: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of general internal medicine,31[1], 109–116. [CrossRef]

- Klementova, M., Thieme, L., Haluzik, M., Pavlovicova, R., Hill, M., Pelikanova, T., & Kahleova, H. [2019]. A Plant-Based Meal Increases Gastrointestinal Hormones and Satiety More Than an Energy- and Macronutrient-Matched Processed-Meat Meal in T2D, Obese, and Healthy Men: A Three-Group Randomized Crossover Study. Nutrients, 11[1], 157. [CrossRef]

- Melina, V., Craig, W., & Levin, S. [2016]. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116[12], 1970–1980. [CrossRef]

- Craig, W. J., Mangels, A. R., & American Dietetic Association [2009]. Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109[7], 1266–1282. [CrossRef]

- American Institute for Cancer Research. [2023]. What is a plant-based diet? AICR’s take. https://www.aicr.org/resources/blog/what-is-a-plant-based-diet-aicrs-take/.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [2020]. 2020-2025 dietary guidelines for Americans. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov.

- Nielsen. [2018]. Plant-based food options are sprouting: Growth for retailers. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2018/plant-based-food-options-are-sprouting-growth-for-retailers/.

- Reinhart, 2019 Reinhart, R. [2019]. Snapshot: Few Americans are vegetarian or vegan. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/238328/snapshot-few-americans-vegetarian-vegan.aspx.

- Lee, V., McKay, T., & Ardern, C. I. [2015]. Awareness and perception of plant-based diets for the treatment and management of type 2 diabetes in a community education clinic: a pilot study. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2015, 236234. [CrossRef]

- Lea, E. J., Crawford, D., & Worsley, A. [2006]. Public views of the benefits and barriers to the consumption of a plant-based diet. European journal of clinical nutrition, 60[7], 828–837. [CrossRef]

- Morton, K. F., Pantalos, D. C., Ziegler, C., & Patel, P. D. [2021]. Whole-Foods, Plant-Based Diet Perceptions of Medical Trainees Compared to Their Patients: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. American journal of lifestyle medicine, 16[3], 318–333. [CrossRef]

- Willet W. C., & Stampfer, M. J. (2013). Current evidence on healthy eating. Annual review of public health, 34, 77–95. [CrossRef]

- Kent, G., Kehoe, L., Flynn, A., & Walton, J. [2022]. Plant-based diets: a review of the definitions and nutritional role in the adult diet. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 81[1], 62–74. [CrossRef]

- Laine, J. E., Huybrechts, I., Gunter, M. J., Ferrari, P., Weiderpass, E., Tsilidis, K., Aune, D., Schulze, M. B., Bergmann, M., Temme, E. H. M., Boer, J. M. A., Agnoli, C., Ericson, U., Stubbendorff, A., Ibsen, D. B., Dahm, C. C., Deschasaux, M., Touvier, M., Kesse-Guyot, E., Sánchez Pérez, M. J., Vineis, P. [2021]. Co-benefits from sustainable dietary shifts for population and environmental health: an assessment from a large European cohort study. The Lancet. Planetary health, 5[11], e786–e796. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F. M., Svetkey, L. P., Vollmer, W. M., Appel, L. J., Bray, G. A., Harsha, D., ... & Cutler, J. A. [2001]. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet. New England journal of medicine, 344[1], 3-10.

- Sofi, F., Cesari, F., Abbate, R., Gensini, G. F., & Casini, A. [2008]. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ [Clinical research ed.], 337, a1344. [CrossRef]

- Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., Garnett, T., Tilman, D., DeClerck, F., Wood, A., Jonell, M., Clark, M., Gordon, L. J., Fanzo, J., Hawkes, C., Zurayk, R., Rivera, J. A., De Vries, W., Majele Sibanda, L., Afshin, A., … Murray, C. J. L. [2019]. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet [London, England], 393[10170], 447–492. [CrossRef]

- Marczak, L., O’Rourke, K., & Shepard, D. [2016]. When and why people die in the United States, 1990-2013. Jama, 315[3], 241-241.

- Hemler, E. C., & Hu, F. B. [2019]. Plant-Based Diets for Personal, Population, and Planetary Health. Advances in nutrition [Bethesda, Md.], 10[Suppl_4], S275–S283. [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M., Godfray, H. C., Rayner, M., & Scarborough, P. [2016]. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113[15], 4146–4151. [CrossRef]

- Michie, S., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Lawton, R., Parker, D., Walker, A., & "Psychological Theory" Group [2005]. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Quality & safety in health care, 14[1], 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. [2012]. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation science : IS, 7, 37. [CrossRef]

- French, S. D., Green, S. E., O’Connor, D. A., McKenzie, J. E., Francis, J. J., Michie, S., Buchbinder, R., Schattner, P., Spike, N., & Grimshaw, J. M. [2012]. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implementation science : IS, 7, 38. [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., Foy, R., Duncan, E. M., Colquhoun, H., Grimshaw, J. M., Lawton, R., & Michie, S. [2017]. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation science: IS, 12[1], 77. [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. [2005]. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology, 8[1], 19-32.

- Stanford, J., Zuck, M., Stefoska-Needham, A., Charlton, K., & Lambert, K. [2022]. Acceptability of Plant-Based Diets for People with Chronic Kidney Disease: Perspectives of Renal Dietitians. Nutrients, 14[1], 216. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. J., Kress, K. S., Armbrecht, E. S., Mukherjea, R., & Mattfeldt-Beman, M. [2014]. Initial investigation of dietitian perception of plant-based protein quality. Food science & nutrition, 2[4], 371–379. [CrossRef]

- Moutou, K. E., England, C., Gutteridge, C., Toumpakari, Z., McArdle, P. D., & Papadaki, A. [2022]. Exploring dietitians’ practice and views of giving advice on dietary patterns to patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A qualitative study. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics: the official journal of the British Dietetic Association, 35[1], 179–190. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, I. W., Mangels, A. R., Goldman, R., & Wood, R. J. [2019]. Dietetics Program Directors in the United States Support Teaching Vegetarian and Vegan Nutrition and Half Connect Vegetarian and Vegan Diets to Environmental Impact. Frontiers in nutrition, 6, 123. [CrossRef]

- Mayr, H. L., Kostjasyn, S. P., Campbell, K. L., Palmer, M., & Hickman, I. J. [2020]. Investigating Whether the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern Is Integrated in Routine Dietetic Practice for Management of Chronic Conditions: A National Survey of Dietitians. Nutrients, 12[11], 3395. [CrossRef]

- Asher, K. E., Doucet, S., & Luke, A. [2021]. Registered dietitians’ perceptions and use of the plant-based recommendations in the 2019 Canada’s Food Guide. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics: the official journal of the British Dietetic Association, 34[4], 715–723. [CrossRef]

- Saintila, J., Calizaya-Milla, Y. E., & Javier-Aliaga, D. J. [2021]. Knowledge of Vegetarian and Nonvegetarian Peruvian Dietitians about Vegetarianism at Different Stages of Life. Nutrition and metabolic insights, 14, 1178638821997123. [CrossRef]

- Janse Van Rensburg, L. M., & Wiles, N. L. [2021]. The opinion of KwaZulu-Natal dietitians regarding the use of a whole-foods plant-based diet in the management of non-communicable diseases. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 34[2], 60-64.

- Duncan, K.H., & Bergman, E. [1999]. Knowledge and attitudes of registered dietitians concerning vegetarian diets. Nutrition Research, 19, 1741-1748.

- Hamiel, U., Landau, N., Eshel Fuhrer, A., Shalem, T., & Goldman, M. [2020]. The Knowledge and Attitudes of Pediatricians in Israel Towards Vegetarianism. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 71[1], 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Meulenbroeks, D., Versmissen, I., Prins, N., Jonkers, D., Gubbels, J., & Scheepers, H. [2021]. Care by Midwives, Obstetricians, and Dietitians for Pregnant Women Following a Strict Plant-Based Diet: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 13[7], 2394. [CrossRef]

- Albertelli, T., Carretier, E., Loisel, A., Moro, M. R., & Blanchet, C. [2024]. Vegetarianism and eating disorders: The subjective experience of healthcare professionals. Appetite, 193, 107136. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, P., Smith, M., Wright, N., Bush, S., & Pullon, S. [2019]. If You Don’t Eat Meat… You’ll Die. A Mixed-Method Survey of Health-Professionals’ Beliefs. Nutrients, 11[12], 3028. [CrossRef]

- Estell, M., Hughes, J., & Grafenauer, S. [2021]. Plant protein and plant-based meat alternatives: Consumer and nutrition professional attitudes and perceptions. Sustainability, 13[3], 1478.

- Betz, M. V., Nemec, K. B., & Zisman, A. L. [2022]. Plant-based Diets in Kidney Disease: Nephrology Professionals’ Perspective. Journal of renal nutrition : the official journal of the Council on Renal Nutrition of the National Kidney Foundation, 32[5], 552–559. [CrossRef]

- Mayr, H. L., Kelly, J. T., Macdonald, G. A., Russell, A. W., & Hickman, I. J. [2022]. Clinician Perspectives of Barriers and Enablers to Implementing the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern in Routine Care for Coronary Heart Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Interview Study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 122[7], 1263–1282. [CrossRef]

- Fresán, U., Vidal-Carou, M. C., Ramos-Truchero, G., de Pipaon, M. S., Moreno, L. A., & Salas-Salvadó, J. [2023]. Knowledge, attitude, and patient advice on sustainable diets among Spanish health professionals. Frontiers in nutrition, 10, 1182226. [CrossRef]

- Bettinelli, M. E., Bezze, E., Morasca, L., Plevani, L., Sorrentino, G., Morniroli, D., Giannì, M. L., & Mosca, F. [2019]. Knowledge of Health Professionals Regarding Vegetarian Diets from Pregnancy to Adolescence: An Observational Study. Nutrients, 11[5], 1149. [CrossRef]

- Olfert, M. D., Wattick, R. A., & Hagedorn, R. L. [2020]. Experiential Application of a Culinary Medicine Cultural Immersion Program for Health Professionals. Journal of medical education and curricular development, 7, 2382120520927396. [CrossRef]

- Mayr, H. L., Kelly, J. T., Macdonald, G. A., & Hickman, I. J. [2022]. ‘Focus on diet quality’: a qualitative study of clinicians’ perspectives of use of the Mediterranean dietary pattern for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The British journal of nutrition, 128[7], 1220–1230. [CrossRef]

- Harkin, N., Johnston, E., Mathews, T., Guo, Y., Schwartzbard, A., Berger, J., & Gianos, E. [2018]. Physicians’ Dietary Knowledge, Attitudes, and Counseling Practices: The Experience of a Single Health Care Center at Changing the Landscape for Dietary Education. American journal of lifestyle medicine, 13[3], 292–300. [CrossRef]

- Krause, A. J., & Williams, K. A., Sr [2017]. Understanding and Adopting Plant-Based Nutrition: A Survey of Medical Providers. American journal of lifestyle medicine, 13[3], 312–318. [CrossRef]

- Sentenach-Carbo, A., Batlle, C., Franquesa, M., García-Fernandez, E., Rico, L., Shamirian-Pulido, L., Pérez, M., Deu-Valenzuela, E., Ardite, E., Funtikova, A. N., Estruch, R., & Bach-Faig, A. [2019]. Adherence Of Spanish Primary Physicians And Clinical Practise To The Mediterranean Diet. European journal of clinical nutrition, 72[Suppl 1], 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M., Singh Ospina, N., Kazory, A., Joseph, I., Zaidi, Z., Ataya, A., Agito, M., Bubb, M., Hahn, P., & Sattari, M. [2019]. The Mismatch of Nutrition and Lifestyle Beliefs and Actions Among Physicians: A Wake-Up Call. American journal of lifestyle medicine, 14[3], 304–315. [CrossRef]

- Lessem, A., Gould, S. M., Evans, J., & Dunemn, K. [2020]. A whole-food plant-based experiential education program for health care providers results in personal and professional changes. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 32[12], 788–794. [CrossRef]

- Boocock, R. C., Lake, A. A., Haste, A., & Moore, H. J. [2021]. Clinicians’ perceived barriers and enablers to the dietary management of adults with type 2 diabetes in primary care: A systematic review. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics : the official journal of the British Dietetic Association, 34[6], 1042–1052. [CrossRef]

- Catapan, S. C., Nair, U., Gray, L., Cristina Marino Calvo, M., Bird, D., Janda, M., Fatehi, F., Menon, A., & Russell, A. [2021]. Same goals, different challenges: A systematic review of perspectives of people with diabetes and healthcare professionals on Type 2 diabetes care. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association, 38[9], e14625. [CrossRef]

- Williams, B., Perillo, S., & Brown, T. [2015]. What are the factors of organizational culture in health care settings that act as barriers to the implementation of evidence-based practice? A scoping review. Nurse education today, 35[2], e34–e41. [CrossRef]

- Gray, M., Joy, E., Plath, D., & Webb, S. A. [2013]. Implementing Evidence-Based Practice: A Review of the Empirical Research Literature. Research on Socia.

- Gianfrancesco, C., & Johnson, M. [2020]. Exploring the provision of diabetes nutrition education by practice nurses in primary care settings. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics : the official journal of the British Dietetic Association, 33[2], 263–273. [CrossRef]

- Smeets, R. G. M., Kroese, M. E. A. L., Ruwaard, D., Hameleers, N., & Elissen, A. M. J. [2020]. Person-centred and efficient care delivery for high-need, high-cost patients: primary care professionals’ experiences. BMC family practice, 21[1], 106. [CrossRef]

- Frank, E., Wright, E. H., Serdula, M. K., Elon, L. K., & Baldwin, G. [2002]. Personal and professional nutrition-related practices of US female physicians. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 75[2], 326–332. [CrossRef]

- Landry, M. J., Ward, C. P., Koh, L. M., & Gardner, C. D. [2024]. The knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions towards a plant-based dietary pattern: a survey of obstetrician-gynecologists. Frontiers in nutrition, 11, 1381132. [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M., Pagliai, G., Casini, A., & Sofi, F. [2018]. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. European journal of clinical nutrition, 72[1], 30–43. [CrossRef]

- Soguel, L., Vaucher, C., Bengough, T., Burnand, B., & Desroches, S. [2019]. Knowledge Translation and Evidence-Based Practice: A Qualitative Study on Clinical Dietitians’ Perceptions and Practices in Switzerland. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119[11], 1882–1889. [CrossRef]

- Byham-Gray, L. D., Gilbride, J. A., Dixon, L. B., & Stage, F. K. [2005]. Evidence-based practice: what are dietitians’ perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge? Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105[10], 1574–1581. [CrossRef]

- Lea, E., & Worsley, A. [2003]. Benefits and barriers to the consumption of a vegetarian diet in Australia. Public health nutrition, 6[5], 505–511. [CrossRef]

- Lea, E., & Worsley, A. [2003]. The factors associated with the belief that vegetarian diets provide health benefits. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 12[3], 296–303.

- Fehér, A., Gazdecki, M., Véha, M., Szakály, M., & Szakály, Z. [2020]. A Comprehensive Review of the Benefits of and the Barriers to the Switch to a Plant-Based Diet. Sustainability, 12[10], 4136. [CrossRef]

- Graça, J., Oliveira, A., & Calheiros, M. M. [2015]. Meat, beyond the plate. Data-driven hypotheses for understanding consumer willingness to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite, 90, 80–90. [CrossRef]

- Mullee, A., Vermeire, L., Vanaelst, B., Mullie, P., Deriemaeker, P., Leenaert, T., De Henauw, S., Dunne, A., Gunter, M. J., Clarys, P., & Huybrechts, I. [2017]. Vegetarianism and meat consumption: A comparison of attitudes and beliefs between vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous subjects in Belgium. Appetite, 114, 299–305. [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M., Clark, M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Wiebe, K., Bodirsky, B. L., Lassaletta, L., de Vries, W., Vermeulen, S. J., Herrero, M., Carlson, K. M., Jonell, M., Troell, M., DeClerck, F., Gordon, L. J., Zurayk, R., Scarborough, P., Rayner, M., Loken, B., Fanzo, J., Godfray, H. C. J., … Willett, W. [2018]. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature, 562[7728], 519–525. [CrossRef]

- Fresán, U., & Sabaté, J. [2019]. Vegetarian Diets: Planetary Health and Its Alignment with Human Health. Advances in nutrition [Bethesda, Md.], 10[Suppl_4], S380–S388. [CrossRef]

- Hallström, E., Carlsson-Kanyama, A., & Börjesson, P. [2015]. Environmental impact of dietary change: a systematic review. Journal of cleaner production, 91, 1-11.

- Vanham, D., Hoekstra, A. Y., & Bidoglio, G. [2013]. Potential water saving through changes in European diets. Environment international, 61, 45–56. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L. A., Meyer, R., Donovan, S. M., Goulet, O., Haines, J., Kok, F. J., & Van’t Veer, P. [2022]. Perspective: Striking a Balance between Planetary and Human Health-Is There a Path Forward?. Advances in nutrition [Bethesda, Md.], 13[2], 355–375. [CrossRef]

- Folkvord, F.; Anschütz, D.; Geurts, M. Watching TV Cooking Programs: Effects on Actual Food Intake among Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 3–9; Erratum in J. Nutr. Educ. Behav.

- Pierce, B., Bowden, B., McCullagh, M., Diehl, A., Chissell, Z., Rodriguez, R., Berman, B. M., & D Adamo, C. R. [2017]. A Summer Health Program for African American High School Students in Baltimore, Maryland: Community Partnership for Integrative Health. Explore [New York, N.Y.], 13[3], 186–197. [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M. C., Bouwman, E. P., Reinders, M. J., & Dagevos, H. [2021]. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite, 159, 105058. [CrossRef]

- Orsini, F., Gasperi, D., Marchetti, L., Piovene, C., Draghetti, S., Ramazzotti, S., ... & Gianquinto, G. [2014]. Exploring the production capacity of rooftop gardens [RTGs] in urban agriculture: the potential impact on food and nutrition security, biodiversity and other ecosystem services in the city of Bologna. Food Security, 6, 781-792.

- Davies A. R. [2020]. Toward a Sustainable Food System for the European Union: Insights from the Social Sciences. One earth [Cambridge, Mass.], 3[1], 27–31. [CrossRef]

| Dietary pattern | Foods |

|---|---|

| Lacto-vegetarian diet | Includes dairy |

| Ovo-vegetarian diet | Includes eggs |

| Lacto-ovo vegetarian diet | Includes dairy and eggs |

| Pesco-vegetarian diet | Includes fish and seafood |

| Vegan diet | Excludes all meat and all animal products |

| Mediterranean diet | Based on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes and moderate consumption of dairy and fish, and low consumption of meat and sweets |

| DASH diet | Based on vegetables, fruits, and whole grains; includes fat-free low-fat dairy products, fish, poultry, beans and nuts. |

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Population and sample | Objective | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanford et al., 2022 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 35 renal dietitians completed online surveys, and 11 participated in in-depth interviews | Explore perspectives of renal dietitians regarding PBDs for chronic kidney disease [CKD] management, and evaluate their acceptability of a hypothetical plant-based dietary prescription | Exploratory Mixed methods: Short online questionnaire and in-depth semi-structured interview | Renal Dietitians perceived PBDs as beneficial to patients with CKD |

| Betz et al., 2022 | USA | Cross-sectional | 382 dietitians [154 physicians, 62 nurse practitioners, 32 fellows, 13 physician assistants, 14 other professionals | Understand perspectives of nephrology professionals towards use of PBDs for treatment of CKD | Online questionnaire based on previous survey | Nephrology professionals believed PBDs were beneficial in management of CKD, but dietitians were more likely to be aware of the benefits of PBDs than other professionals |

| Fuller & Hill, 2022 | UK | Cross-sectional | 116 specialist eating disorder professionals, 90 General mental health and 186 other professionals | Investigate attitudes of healthcare professionals towards veganism | Self-reported questionnaire based on General eating habits and ATvegan questionnaires | All had positive views of veganism, but general mental health professionals had more positive attitudes than eating disorder specialists and other professionals |

| Bettinelli et al., 2019 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 140 nurses,135 pediatric nurses, 60 midwives, 43 health care support workers, 40 staff nurses | Assess knowledge of healthcare professionals regarding adoption of vegetarian diets from pregnancy through adolescence | Online questionnaire developed for the study and pre-tested | Clinicians had positive view of the Mediterranean diet (MD), though it was not routinely recommended due to limited knowledge, practice skills and training. |

| Hughes et al., 2014 | USA | cross-sectional | 136 dietitians of which 124 were registered dietitians | Assess dietitians’ perceptions of plant-based protein quality | Online questionnaire developed for the study and pre-tested | Dietitians had a positive attitude towards PBDs but knowledge about plant-based protein quality was limited |

| Moutou et al., 2021 | UK | Cross-sectional | N=12 registered dietitians | Explore dietitians’ views about advising on 5 dietary patterns (including MD and DASH diets) deemed effective for management of type 2 diabetes | Semi-structured interviews with short demographic questionnaires developed for the study. | Study participants considered the MD effective, but most had mixed responses about the DASH diet. |

| Mayr et al., 2022 | Australia | Cross-sectional | N=57 clinicians (21 nurses, 19 doctors, 13 dietitians and 4 physiotherapists) | Explore multidisciplinary health care professionals’ perspectives on recommending MD to patients with coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes | Qualitative study with individual semi-structured interviews via telephone or face-to- face | The MD was not routinely recommended, clinicians had limited knowledge and practice skills regarding MD, barriers to recommending the MD were lack of education and training, and personal experience/interest |

| Meulenbroeks et al., 2021 | Netherlands | Cross-sectional | N=411 (121 midwives, 179 obstetricians, and 111 dietitians) | Evaluate self-reported knowledge and advice given by Dutch obstetric caregivers and dietitians to pregnant women following PBDs | Online questionnaire developed based on focus group interviews | Both obstetricians and midwives reported limited knowledge about strict PBDs. Only 38.7% of dietitians felt they had enough knowledge to advise pregnant women on strict PBDs. They believed that women following a strict PBD during pregnancy were at a higher risk of nutrient deficiencies. |

| Mayr et al., 2022 | Australia | Cross-sectional | N=14 (7 doctors, 3 nurses, 3 dietitians and 1 exercise physiologist) | Assess multidisciplinary clinicians’ perspectives on whether the Mediterranean diet (MD) is recommended in routine management of non-alcoholic liver disease | Semi-structured individual phone and face-to-face interviews | The MD was seen as an evidence-based approach for enhancing diet quality, promoting weight loss, and reducing the risk of chronic co-morbidities. However, some doctors and nurses had limited knowledge of the specific literature supporting the benefits of following a MD. |

| Hawkins et al., 2019 | USA | cross- sectional |

N= 205 nutrition and dietetics program directors | Investigate curricular practices in accredited dietetics programs and assess prevalence and perceived importance of vegetarian and vegan nutrition instruction | Online questionnaire developed for the study and pre-tested | Over 90% of program directors agreed that vegetarian nutrition should be taught, while 87% agreed that vegan nutrition should be taught. Program directors in northeastern programs had higher percentages of agreement than those in southern programs. 51% and 49% of the programs teach vegetarian and vegan nutrition, respectively. |

| Albertelli et al., 2024 | France | Cross- sectional |

N= 18 (14 dietitians, 3 physicians specialized in nutrition, and 1 psychiatrist) | Investigate healthcare professionals’ subjective experience of vegetarianism in patients with eating disorders (ED) | Qualitative study with remotely administered semi- structured interviews via videoconferences and telephone. | Health professionals regarded vegetarianism as a restrictive approach and often linked it to eating disorders in patients. They were strongly opposed to veganism, citing risk of severe nutritional deficiencies. |

| Mayr et al., 2020 | Australia | Cross- sectional |

N=182 dietitians who had practiced with at least one of the relevant chronic disease patient groups. | Evaluate the extent the MD is routinely recommended by dietitians to patients with chronic diseases. | Online questionnaire based on TDF | 62%, 46%, and 39% of dietitians strongly agreed that there was enough evidence to support recommending MD to patients with CVD, type 2 diabetes, and non-alcoholic liver disease respectively. 48% strongly agreed that they were knowledgeable about the principles of MD, and 46% were confident in counseling patients about MD. |

| McHugh et al., 2019 | New Zealand | Cross- sectional |

N=41 (20 doctors, 13 nurses, 7 pharmacists, and 1 osteopath) | Investigate whether health professionals have sufficient nutrition education for their roles in health education and promotion, and whether their nutrition beliefs were consistent with current literature | Mixed methods including online de novo questionnaire and one focus group | PBDs were generally viewed as beneficial to health but deemed complicated. 43% of participants reported dissatisfaction with the amount of nutritional training received. |

| Olfert et al., 2020 | USA | descriptive case study | N= 29 health professionals, 15 currently practicing in cohort 1 and 14 aspiring health professionals in cohort 2 from various disciplines | Determine effectiveness of culinary medicine and MD to enhance nutritional knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy of current and aspiring (student) health professionals | Online questionnaire developed but influenced by evidence-based sources | At baseline, cohort 2 had higher attitude and knowledge scores. There was no significant difference in mean self-efficacy scores or mean MD adherence scores. |

| Hamiel et al., 2020 | Israel | Cross- sectional |

N=270 pediatricians, 14.1% were following a vegetarian diet | Assess knowledge and attitudes of pediatricians towards vegetarian diets | Online questionnaire based on Previously validated questionnaire | Pediatricians had knowledge gaps regarding vegetarian nutrition, and most did not have a positive attitude towards vegetarian diets. Knowledge was positively correlated with attitude |

| Lessem et al., 2020 | USA | Experiential education program | N=30 (13 nurse practitioners, 14 registered nurses, and 3 physicians) | Increase knowledge and acceptance of whole-food plant-based [WFPB] diet, and likelihood of counseling patients about the diet among health care workers | Online questionnaires based on previously validated research | Pre intervention average knowledge scores were 65.4%. Average self-efficacy scores for knowledge and counseling were 2.64 and 2.38 at baseline on a scale of 1 to 4. |

| Sentenach et al., 2019 | Spain | Cross- sectional |

N=422 physicians (PREDIMED screener) and N= 212 physicians (knowledge/opinion survey) | Evaluate physicians’ knowledge/awareness of and adherence to a MD | Online questionnaire based on PREDIMED MD screener previously used in the PREDIMED study | Most physicians did not adhere to MD but 70% considered themselves knowledgeable about the benefits of the MD, and 60% were willing to recommend it to patients |

| Estell & Hughes, 2021 | Australia | cross- sectional |

N=660 [228 nutrition professionals | Explore consumer and nutrition professional perceptions and attitudes to plant protein including plant-based meat alternatives | Online questionnaire based on previous research | Over 80% of nutrition professionals agreed that following a PBD promoted good nutrition, and over 70% disagreed that it was hard to meet protein requirements while following a PBD. |

| Asher et al., 2021 | Canada | cross- sectional |

N=403 dietitians | Assess Canadian registered Dietitians’ attitudes and behaviors towards the new food guidelines’ increased plant-based recommendations | Online questionnaire developed for the study and pre-tested | Over 80% of dietitians considered the food guide’s recommendation to choose plant-based protein foods as evidence-based. Most had a positive view of the new guidelines, and 58.7% were more likely to encourage their clients to select plant-based protein options. |

| Aggarwal et al., 2019 | USA | cross- sectional |

N=303 physicians from departments of cardiology and general medicine | Assess nutrition and exercise knowledge and personal health behaviors of physicians | Online questionnaire based on validated surveys | Less than 25% of the physicians in the study followed the facets of MD |

| Saintila et al., 2021 | Peru | cross- sectional |

N=179 registered dietitians [72 vegetarians and 107 non-vegetarians] | Compare level of knowledge of vegetarian and non-vegetarian Peruvian dietitians regarding vegetarianism | Online questionnaire based on the recommendations of the current dietary guidelines | Vegetarian dietitians were more knowledgeable about the risks and benefits associated with vegetarian diets |

| Janse et al., 2021 | South Africa | cross- sectional |

N=101 dietitians [45 government employed and 48 in private practice] | Assess whether dietitians in South Africa would use a whole foods plant-based diet (WFPBD) to address chronic diseases | Online questionnaire based on validated surveys | A significant number of dietitians reported inadequate university training surrounding PBDs, albeit a significant number of them were confident about prescribing PBDs to clients. |

| Duncan & Bergman, 1999 | USA | cross- sectional |

N=183 registered dietitians from Vermont, Nebraska, and Washington | Investigate what registered dietitians know about safety, adequacy, and health benefits of vegetarian diets | paper questionnaire sent by mail | Average knowledge and attitude scores were greater for registered dietitians who were currently or had previously followed a vegetarian diet. Overall knowledge scores varied between states. |

| Fresan et al., 2023 | Spain | cross- sectional |

N=2545 health professionals (550 dietitian-nutritionists, 1139 nurses, 427 physicians and 346 pharmacists, and 83 others) | Assess knowledge and attitudes regarding sustainable diets among health professionals in Spain | Online questionnaire developed for the study | 21.5% of respondents had not previously heard about sustainable diets, and 32.4% acknowledged their limited knowledge about the subject. Most when presented with information about sustainable diets considered it important to promote them. |

| Krause et al., 2019 | USA | cross- sectional |

N=64 (12 residents,6 fellows, 46 physician attendings) | Assess medical providers’ knowledge of plant-based nutrition and their willingness to recommend it to patients | Online questionnaire developed for the study | 33% of respondents were willing to recommend PBDs, while majority (51%) responded with maybe. Only 28% were willing to adopt a PBDs, 25% were willing to try it for 6 months or more. |

| Lee et al., 2015 | Canada | cross- sectional |

n= 98 patients n=25 healthcare providers | Assess awareness, barriers, and promoters of plant-based diet use for management of type 2 diabetes for the development of an educational program | 2 sets of questionnaires for patients and health care providers were developed for the study. | 72% of health care providers reported knowledge of PBDs for management of type 2 while majority of patients (89%) had not heard of using PBDs to treat/manage type 2 diabetes. Less than 50% of respondents were aware of the benefits of PBDs regarding other chronic conditions. |

| Harkin et al., 2018 | USA | cross- sectional |

N=236 (140 physicians and 96 cardiologists) | Assess basic nutritional knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians | Online questionnaire based on validated surveys | Nutrition knowledge was average, with only 13.5% feeling sufficiently trained to discuss nutrition with their patients. Physicians most commonly recommended the Mediterranean diet (55.1%), followed by the DASH diet (38.2%), to their patients. |

| Theme | TDF Domains | Enablers | Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | -Knowledge -Skills |

- Personal experience with PBDs -Knowledge of diet-disease relationship -Adequate knowledge of PBDs and their benefits -Knowledge of scientific rationale for PBDs |

-Limited knowledge of basic principles of PBDs to discuss with patients -Lack of knowledge about benefits of PBDs - Limited knowledge and practice skills -Limited knowledge exchange within and across multidisciplinary teams. |

| Education and training | -Skills -Social/professional role and identity -Environmental context and resources |

-Education about PBDs at university level and continuous professional evidence-based training, conferences, etc -Patient knowledge about PBDs -Online nutrition education |

-Lack of education or training at degree and professional levels -Misinformation from other health professionals and non-peer-reviewed sources such as internet, media -Low self-efficacy to discuss PBDs with patients due to inadequate training |

| Evidence-based guidelines | -Skills -Social/professional role and identity -Beliefs about consequences |

-Awareness of peer-reviewed evidence -Awareness of current dietary guidelines in support of PBDs -Access to position papers in support of PBDs from respectable scientific bodies |

-Perceived lack of evidence-based properly tested practice guidelines -Lack of access to evidence summaries -Disagreement with available evidence |

| Multi-disciplinary collaboration | - Social/professional role and identity - Environmental context andresources -Social influences |

-Consistent messaging from various health professionals | -Misinformation from other health professionals - Limited knowledge exchange within and across multidisciplinary teams. |

| Personal experience and interest | -Skills -Beliefs about capabilities - Environmental context and resources |

-Health professionals trying out PBDs even if for a limited time, and counseling patients based on evidence and experience |

-Lack of health professional/patient personal experience with PBDs - Lack of interest to try PBDs even for a short time. -Providing counseling based on personal biases rather than evidence |

| Educational resources for both patients and health professionals | -Knowledge - Environmental context and resources |

-Availability of educational materials such as meal plans, menu plans, food checklists, recipes, and mobile apps to teach and share with patients - Access to evidence summaries - Access to visually appealing content for patients |

-Absence of patient education tools and resources/materials -Low confidence to discuss PBDs with patients -Limited/non-existent practical- based professional development -Access to clinical guidelines related to PBDs. |

| Lack of time | -Goals -Environmental context and resources |

-Access to resources and tools to share with clients to use at home |

-Limited time allocated to patients’ consultations -Limited time to keep up with peer-reviewed literature -Belief that patients prioritize convenience foods over food preparation due to limited time |

| Safety and compliance challenges | - Beliefs about consequences -Emotion |

- Individual patient counselling -Access to evidence-based clinical guidelines -Having knowledge of PBD benefits |

-Fear of inducing comorbidities like hyperkalemia and or hyperglycemia among patients with chronic kidney disease [CKD] -Fear around potassium control among patients with CKD -Deficiency concerns |

| Lack of confidence in patient capabilities | - Beliefs about consequences -Optimism |

-Educating patients about PBD health benefits and key concepts -Individual patient counselling -Inclusion of evidence-based or endorsed patient resources and tools. -Goal setting around changing patient dietary patterns |

-Diet presumed unrealistic for patients of low socioeconomic background - PBDs perceived to be incompatible with patient food culture and eating patterns -Patients deemed to have low health literacy/knowledge deficit of diet-disease relationship -Assume patients are unwilling to try PBDs because they are hard/complicated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).