1. Introduction

Asthma is one of the most prevalent chronic respiratory diseases worldwide and a leading cause of medical consultations among children and adolescents [

1,

2]. It affects over 250 million people globally, with many cases diagnosed during childhood, making it a significant public health issue [

3]. In 2019 alone, asthma affected 262 million individuals and accounted for approximately 461,000 deaths [

4].

The development and progression of asthma are influenced by multiple components of an individual's exposome, particularly the interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental exposures, which can shape disease severity and prognosis [

5]. Asthma is also closely linked to allergic diseases. Viral respiratory infections can exacerbate allergic responses and trigger asthma attacks [

6]. The World Allergy Organization estimates that 40% of the global population suffers from allergic conditions, with comparable prevalence rates in tropical and temperate regions [

7].

In Colombia, asthma symptom prevalence has increased from 10.4% to 12% over the past decade, with notable variability across age groups and geographic regions [

8]. Other studies have reported prevalence rates ranging from 8.8% to 30.8% among children and adolescents [

9].

Given asthma's clinical impact and its close association with environmental and allergic factors, understanding its epidemiological patterns, particularly in pediatric populations is critical. This study aimed to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of children and adolescents hospitalized for asthma exacerbations in a tertiary pediatric hospital in Barranquilla, Colombia, across three periods: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The goal was to identify factors associated with asthma severity and hospitalization, and to support the development of more effective prevention strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted at a tertiary-level pediatric hospital in Barranquilla, Colombia. This coastal city is located in a region with a dry tropical climate, characterized by an average annual temperature of 27°C. The area experiences two main climatic seasons: a dry period from May to December and a rainy season from April to November. Notably, the rainy season is briefly interrupted in June and July by southeastern trade winds, a local climatic event known as the San Juan Summer. The average annual precipitation is approximately 821 mm, with peak humidity levels typically occurring in September and November [

10].

2.2. General Descriptions.

The initial study population consisted of 6,024 children and adolescents aged 3 to 17 years. Inclusion criteria for follow-up of asthma cases included medical records with a documented pulmonary score, a confirmed diagnosis of asthma, a visit to the emergency department, and subsequent hospitalization between 2019 and 2023. Exclusion criteria were a history of liver disease, renal insufficiency, incomplete medical records, or being under 3 years of age.

After applying these criteria, 307 eligible patients were identified and categorized into three independent study groups based on their date of hospital admission. The pre-pandemic group comprised 87 children admitted between January 1, 2019, and January 29, 2020. The pandemic group included 175 children admitted between January 30, 2020, and May 5, 2023. The post-pandemic group included patients admitted from May 6 to December 31, 2023.

Statistical Analysis

Data was compiled in Excel matrices using variables extracted from medical records. Each patient was assigned a double-blind identification code to ensure confidentiality. The analysis included sociodemographic variables (sex and age) and clinical variables such as nutritional status, breastfeeding history, pulmonary score, corticosteroid use, COVID-19 vaccination status, and exposure to environmental pollutants. The pulmonary score was used as the primary response variable and categorized as mild (0–3), moderate (4–6), or severe (7–9), based on established scoring criteria for asthma severity.

Three frequency matrices were created, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative variables. Contingency table analyses were performed using the chi-square test (χ²) for quantitative comparisons and Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

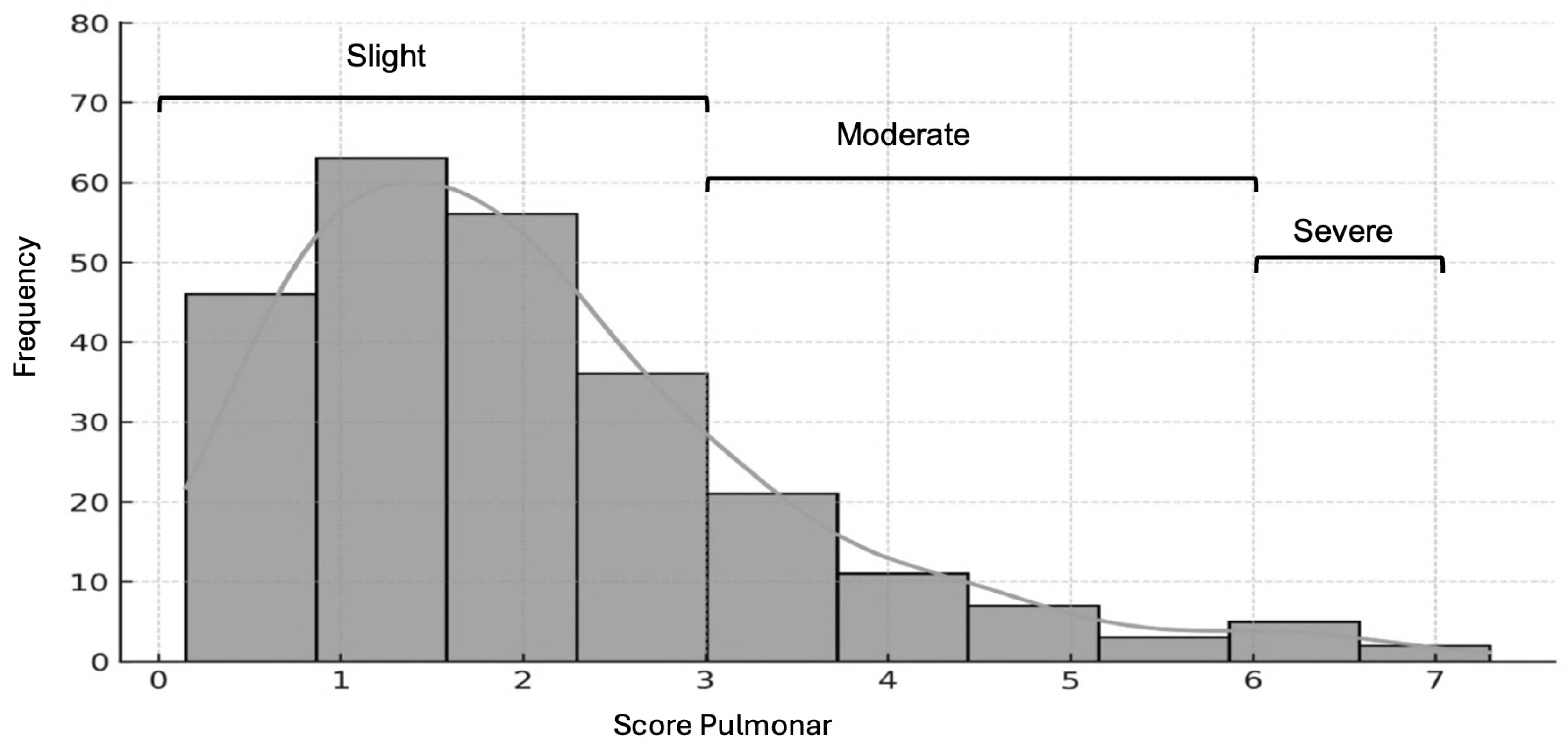

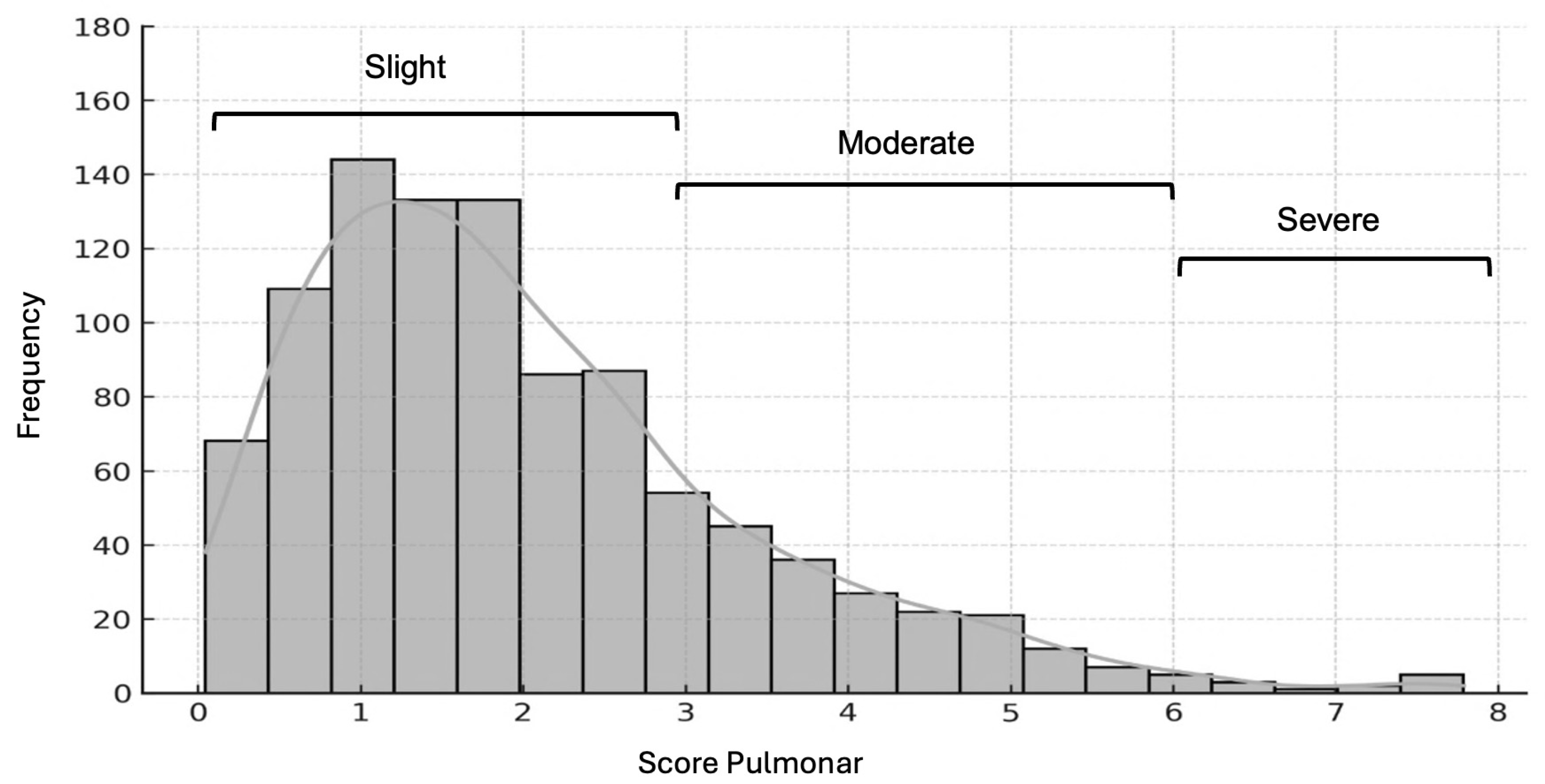

Patients were initially classified into three groups based on hospitalization period: pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic. To address sample size imbalances and facilitate comparison, pulmonary score categories were regrouped into two: mild (0–3) and moderate-to-severe (4–9). Subsequently, patients were reorganized into two main groups: those hospitalized before the pandemic and those hospitalized during the pandemic. The distribution of pulmonary scores for each group is shown in

Figure 1 (pre-pandemic) and

Figure 2 (pandemic).

Correlations between variables and pulmonary score severity were analyzed using the recategorized score. Categorical variables were numerically coded and analyzed using a binary logistic regression model (BLRM) with maximum likelihood estimation. Both the logistic regression model and the log-likelihood ratio test were conducted with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Correlations between variables were performed based on the redistribution of the pulmonary score. Categorical variables were converted into numerical values and analyzed using a binary logistic regression model (BLRM) with maximum likelihood estimation. For both analyses the binary logistic regression model and the Log-Likelihood Ratio test the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Comparative analysis of clinical variables across the three study periods pre-pandemic, COVID-19 emergency, and post-pandemic revealed several statistically significant differences. Notably, hospitalization rates varied significantly between periods (p = 0.008), with an increase during the pandemic. A significant difference was also observed in sex distribution across the periods (p = 0.003), as well as in nutritional status by sex during the pre-pandemic period (p = 0.018).

There were significant changes in the use of corticosteroids, with higher usage observed during the pandemic (p = 0.009). Likewise, COVID-19 vaccination status showed expected variation across periods (p < 0.001), reflecting the timeline of vaccine availability. Additionally, exposure to environmental pollutants differed significantly between groups (p = 0.010), with higher reported exposure pre-pandemic.

No statistically significant differences were found for variables such as age group (infant vs. adolescent), breastfeeding status, or pulmonary score distribution by sex across the study periods. See

Table 1

3.1. Redistribution of Pulmonary Scores in the Recategorization Process

The frequency distribution of pulmonary scores by severity mild (0–3), moderate (4–6), and severe (7–9) revealed that only a small number of patients fell into the severe category (7–9) across all study periods (see

Table 1,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). This pattern underscores the predominance of mild and moderate asthma exacerbations among hospitalized children during the analyzed timeframe. These findings highlight the need to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic and other contributing factors may have influenced hospitalization trends and asthma severity. Such evidence is essential for guiding future research on social and clinical determinants of health in pediatric populations at risk.

3.1.1. Binary Logistic Regression Model Analysis – Pre-Pandemic Group

A binary logistic regression analysis was performed for the infant group in the pre-pandemic period, using the regrouped pulmonary score as the dependent variable (mild [0–3] vs. moderate/severe [4–6]). The independent variables were selected based on those described in Table 1, including sex, age, weight, and breastfeeding history.

As shown in

Table 2, the overall model was not statistically significant, indicating limited predictive value for distinguishing between mild and moderate/severe asthma cases in this group. The model explained approximately 10.9% of the variability in pulmonary score classification (R² = 0.109), and none of the individual variables—including sex, age, weight, and breastfeeding—demonstrated a statistically significant association with asthma severity. These findings suggest that other, unmeasured factors may play a more prominent role in determining exacerbation severity in the pre-pandemic infant population.

3.1.2. Binary Logistic Regression Model Analysis of Infants Evaluated During the COVID-19 Pandemic Period

The binary logistic regression model (R²) accounts for approximately 10.9% of the variability in the classification of mild versus moderate cases. The odds ratio indicates that the model as a whole is not statistically significant. Additionally, variables such as sex, age, weight, and breastfeeding do not show a meaningful impact on the prediction. However, for the group of individuals during the pandemic, the model is statistically significant, with breastfeeding, weight, and hospitalization admission emerging as the variables most strongly associated with the response variable (Pulmonary Score).

3.1.3. Binary Logistic Regression Model Analysis – COVID-19 Pandemic Period

A binary logistic regression analysis was conducted for infants evaluated during the COVID-19 pandemic period, using the dichotomized pulmonary score (mild [0–3] vs. moderate/severe [4–6]) as the dependent variable. The model accounted for approximately 10.9% of the variance in asthma severity classification (R² = 0.109).

Unlike the pre-pandemic group, the model for the pandemic period was statistically significant overall, suggesting a meaningful relationship between selected variables and asthma severity during this timeframe. Among the predictors analyzed, breastfeeding history, weight, and hospitalization status were the variables most strongly associated with the pulmonary score outcome. In contrast, sex and age did not contribute significantly to the model.

These results indicate that specific clinical and perinatal factors gained predictive relevance during the pandemic, possibly reflecting shifts in exposure patterns or healthcare access affecting asthma management in infants. see

Table 3

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the clinical and epidemiological characteristics associated with asthma as a leading cause of hospitalization among children and adolescents at a tertiary pediatric center in Barranquilla, Colombia. The findings offer insights into how various clinical, social, and environmental factors influence the development, severity, and management of pediatric asthma.

One of the most notable findings was the variation in asthma-related hospitalization rates across the different study periods. Geographic differences observed during the COVID-19 emergency suggest that the pandemic may have affected both the incidence and the clinical management of asthma exacerbations at the local level [

11]. This may be partially explained by an increase in viral respiratory infections during the pandemic. Previous research has demonstrated that viruses, particularly respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), increase the risk of both asthma development and symptom exacerbation [

12].

Nutritional status emerged as another key factor, particularly with gender-specific differences, as shown in

Table 1. Notably, males exhibited more pronounced variations. Overweight and obesity have been linked to a higher risk of asthma exacerbations [

13] and reduced responsiveness to certain treatments [

14]. Conversely, undernutrition may impair immune and pulmonary function, thereby worsening asthma symptoms [

15]. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating nutritional assessment and intervention into comprehensive pediatric asthma care.

Both ends of the malnutrition spectrum obesity and undernutrition can influence asthma severity and disease control. Obesity may promote systemic inflammation and blunt response to standard therapies [

16], while undernutrition increases vulnerability to infections and complications. These effects are likely amplified in socioeconomically vulnerable settings, such as food-insecure households in Colombia’s Caribbean region [

17].

Another notable observation was the pattern of corticosteroid use, which increased during the pandemic contrasting with findings from our study. This inconsistency may reflect the uncertainty and rapid adaptation of new clinical protocols by healthcare providers [

18], aimed at minimizing complications [

19]. The overlap of asthma and SARS-CoV-2 infection may have prompted more aggressive corticosteroid treatment to control inflammation and prevent adverse outcomes [

20]. Nonetheless, it remains essential to balance benefits and risks of corticosteroid use, especially during viral outbreaks, and to align with international clinical guidelines [

21,

22].

Beyond clinical factors, the broader social and environmental context of Barranquilla—Colombia’s most important Caribbean coastal city may also contribute to asthma outcomes. Rapid industrial expansion has led to increased pollution [

23], which may be driving the growing prevalence and severity of asthma among children [

24].

Epidemiologically, binary logistic regression models have shown that variables such as sex, age, race, household poverty, and family structure when adjusted for residential location—can help explain the rising burden of asthma in younger populations. This highlights the need for localized public health strategies targeting structural determinants of health. One such approach includes implementing systems to monitor severe asthma cases from hospital discharge through home-based care [

25].

Another relevant factor in our findings was vaccination coverage. Children and adolescents with up-to-date vaccination schedules were more frequently represented among asthma cases. Although early concerns were raised about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines in allergic individuals [

26], current evidence supports their safety and tolerability in patients with asthma. Moreover, vaccination may contribute to better asthma control by reducing respiratory infection risks [

27].

Subdividing the pediatric population into pre- and post-pandemic periods allowed for better classification of moderate and severe asthma cases and revealed an increase in hospitalizations. A significant proportion of children were prone to severe asthma, with key variables—including breastfeeding, weight, and previous hospitalization—having a meaningful impact on pulmonary scoring.

Breastfeeding was associated with a lower likelihood of moderate-to-severe asthma (p = 0.022), supporting its protective role against respiratory conditions in early childhood. Similarly, both body weight and hospitalization history were significantly associated with disease severity (p < 0.05), indicating their influence on asthma progression during the pandemic.

These patterns may be explained by lifestyle changes, reduced access to healthcare, and shifts in environmental exposure due to pandemic lockdowns. As such, the findings reinforce the importance of accounting for the broader epidemiological context when designing asthma prevention and treatment strategies. The contrast between the pre-pandemic and COVID-19 emergency periods suggests that the pandemic not only altered risk exposure but may also have contributed to both the escalation and potential mitigation of pediatric asthma.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the multifactorial nature of asthma in children and adolescents, emphasizing the influence of clinical, nutritional, environmental, and socioeconomic variables on disease severity and hospitalization. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a key inflection point, exposing shifts in healthcare access, treatment approaches, and risk exposure that impacted asthma outcomes.

Findings underscore the protective role of breastfeeding, the significance of nutritional status, and the implications of prior hospitalization in determining asthma severity. While corticosteroids remain central to asthma management, their use must be carefully weighed, especially during viral outbreaks such as COVID-19. Additionally, the observed association between up-to-date vaccination schedules and asthma cases supports the safety and potential benefit of immunization in respiratory disease control.

Environmental and structural factors, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions like Barranquilla, must be integrated into public health strategies. Interventions should prioritize targeted, community-based approaches that address food insecurity, pollution, and healthcare inequities. Continued monitoring and research are essential to inform policies and ensure effective, context-specific asthma management for pediatric populations in similar settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.C. and S.F.M; methodology, M.A.R; software, J.L.C.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, M.A.R. and M.A.M.; resources, K.F.V; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.C. and M.A.C; writing—review and editing, J.L.C and D.P.G.; visualization, S.F.M.; supervision, M.A.C.; project administration; J.L.C and K.F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with institutional regulations and in compliance with article 11 of Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Political Constitution of Colombia, the physical integrity of the population studied was not put at risk. The confidentiality and privacy of the patients was fully guaranteed. Additionally, the study was approved by the university ethics committee under protocol number PRO-CEI-USB-CE-0514-00-00 (Universidad Simón Bolívar).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to in case of need.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Universidad Simón Bolívar for providing us with access to the Scopus and Web of Science databases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| °C |

Celsius |

| R2

|

Coefficient of determination |

| °C |

Celsius |

| COVID- 19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| MDLB |

Binary Logistic Regression Model |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome due

to Coronavirus 2 |

| VSR |

Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

References

- Aydin, M. Maintenance of Medical Care of Children and Adolescents with Asthma during the SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Pandemic: An Opinion. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604849. [CrossRef]

- Altman, M. C.; Kattan, M.; O'Connor, G. T.; Murphy, R. C.; Whalen, E.; LeBeau, P.; et al. Associations between Outdoor Air Pollutants and Non-Viral Asthma Exacerbations and Airway Inflammatory Responses in Children and Adolescents Living in Urban Areas in the USA: A Retrospective Secondary Analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7(1), e33–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, A. M.; Brand, P.; Cavada, G.; Koppmann, A.; Rivas, M.; Mackenney, J.; et al. Hospitalizations for Asthma Exacerbation in Chilean Children: A Multicenter Observational Study. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.) 2018, 46(6), 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global Burden of 369 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396 (10258), 1204–1222. [CrossRef]

- Farzan, N.; Vijverberg, S. J.; Andiappan, A. K.; Arianto, L.; Berce, V.; Blanca-López, N.; et al. Rationale and Design of the Multiethnic Pharmacogenomics in Childhood Asthma Consortium. Pharmacogenomics 2017, 18(10), 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhou, K.; Yan, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Differences in the Prevalence of Allergy and Asthma among US Children and Adolescents during and before the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Public Health 2024, 24(1), 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, K. C.; Brehler, R.; Endler, C.; Höflich, C.; Kespohl, S.; Plaza, M.; et al. Impact of Climate Change on Allergic Diseases in Germany. J. Health Monit. 2023, 8 (Suppl 4), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, E.; Rojas, M. X.; Ardila, M. C.; Rondón, M. A.; Peñaranda, A.; Barragán, A. M.; et al. Factors Associated with Asthma Symptoms in Colombian Subpopulations Aged 1 to 17 and 18 to 59: Secondary Analysis of the Study “Prevalence of Asthma and Other Allergic Diseases in Colombia 2009–2010”. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.) 2025, 53(1), 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-López, S.; Pérez-Herrera, L. C.; Peñaranda, D.; Hernández, D. C.; García, E.; Peñaranda, A. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Allergic Diseases in School Children and Adolescents Aged 6–7 and 13–14 Years from Two Rural Areas in Colombia. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.) 2021, 49(3), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Carrascal, J.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Acosta-Hoyos, A. J.; Quintana-Sosa, M. uto Repair Workers Exposed to PM2.5 Particulate Matter in Barranquilla, Colombia: Telomere Length and Hematological Parameters. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2023, 887, 503597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhi, Y.; Ying, S. COVID-19 and Asthma: Reflection during the Pandemic. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 59, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jartti, T.; Bønnelykke, K.; Elenius, V.; et al. Role of Viruses in Asthma. Semin. Immunopathol. 2020, 42, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitra, S.; Carsin, A.; Abramson, M. J.; et al. Long-Term Effect of Asthma on the Development of Obesity among Adults: An International Cohort Study. Thorax 2023, 78, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Ricketts, H. C.; Steffensen, F.; Goodfellow, A.; Cowan, D. C. Obesity Affects Type 2 Biomarker Levels in Asthma. J. Asthma 2022, 60(2), 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassilopoulou, E.; Venter, C.; Roth-Walter, F. Malnutrition and Allergies: Tipping the Immune Balance towards Health. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13(16), 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, N. B.; Baur, L. A.; Felix, J. F.; et al. Child and Adolescent Obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertuz-Guzmán, D. L.; Chams-Chams, L. M.; Valencia-Jiménez, N. N.; Arrieta-Díaz, J.; Luna-Carrascal, J. Comprendiendo la Inseguridad Alimentaria en Familias Rurales: Un Estudio de Caso en Pueblo Nuevo (Córdoba, Colombia). Aten. Primaria 2025, 57(4), 103109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalpakam, A.; Secord, E.; Pansare, M. The Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Pediatric Asthma in the United States. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2021, 68(5), 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Z. I.; Oliveira, C. R.; Abzug, M. J.; Anosike, B. I.; Ardura, M. I.; Bio, L. L.; et al. Guidance for Prevention and Management of COVID-19 in Children and Adolescents: A Consensus Statement from the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society Pediatric COVID-19 Therapies Taskforce. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 13(3), 159-185. [CrossRef]

- Manti, S.; Leotta, M.; D’Amico, F.; Foti Randazzese, S.; Parisi, G. F.; Leonardi, S. Severe Asthma and Active SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Insights into Biologics. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleecker, E. R.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Bjermer, L.; Caminati, M.; Canonica, G. W.; Kaplan, A.; et al. Systemic Corticosteroids in Asthma: A Call to Action from World Allergy Organization and Respiratory Effectiveness Group. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15(12), 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboltz, A.; Kumar, S.; Duncan, G. A. Inhaled Drug Delivery for the Targeted Treatment of Asthma. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 198, 114858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Carrascal, J.; Quintana-Sosa, M.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Genotoxicity Biomarkers in Car Repair Workers from Barranquilla, a Colombian Caribbean City. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2021, 85(7), 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Plata, L.; Agudelo-Castañeda, D.; Castillo, M.; Teixeira, E. C. PM10 Source Identification: A Case of a Coastal City in Colombia. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2022, 22(10), 210293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Bajwa, S.; Brahmbhatt, D.; Lovinsky-Desir, S.; Sheffield, P. E.; Stingone, J. A.; et al. Multi-Level Socioenvironmental Contributors to Childhood Asthma in New York City: A Cluster Analysis. J. Urban Health 2021, 98, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrenger, J.; Martin, D. D.; Jenetzky, E. Infants’ Immunisations, Their Timing and the Risk of Allergic Diseases (INITIAL): An Observational Prospective Cohort Study Protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. P.; Sun, Y. L.; Wang, Y. F.; Yazici, D.; Azkur, D.; Ogulur, I.; et al. Recent Developments in the Immunopathology of COVID-19. Allergy 2023, 78(2), 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).