Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

27 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Euterpe oleracea Martius

2.1. Euterpe oleracea Martius Botanical Description

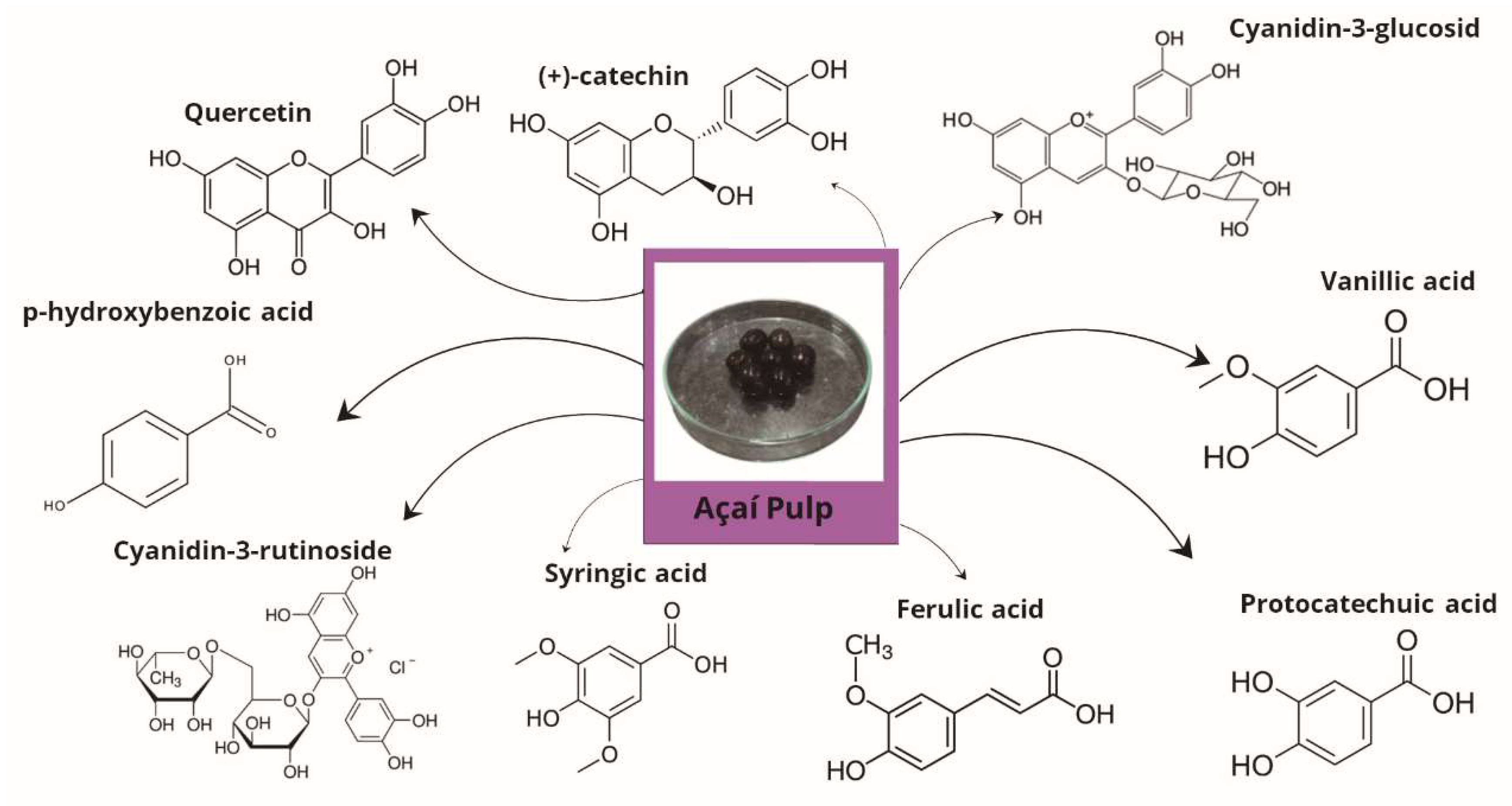

2.2. Açaí Pulp Chemical Composition and Pharmacological Actions

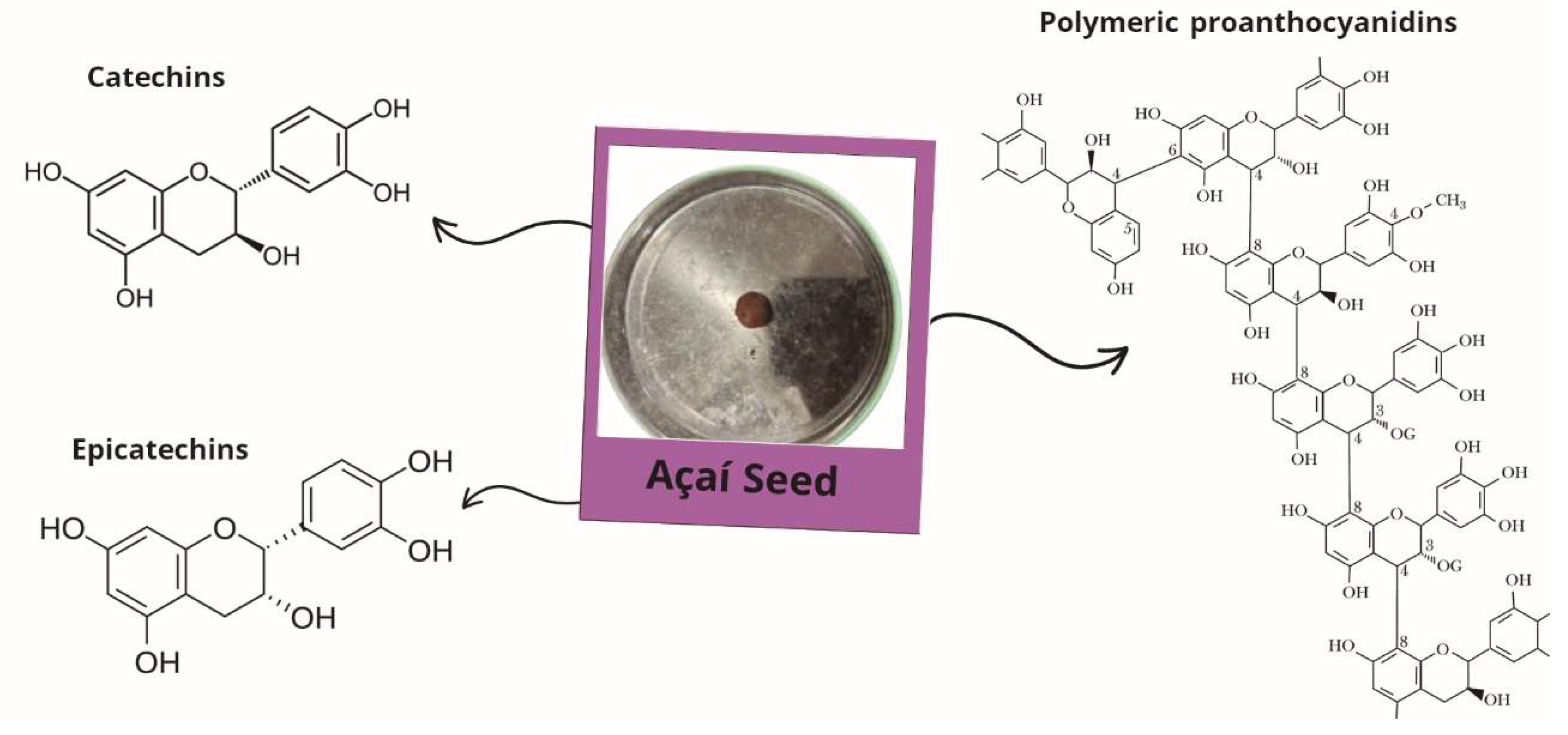

2.3. Açaí Seed Chemical Composition and Pharmacological Actions

2.4. Açaí Pulp And Seed Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Actions in Peripheral Tissues: Perspective For AD Treatment

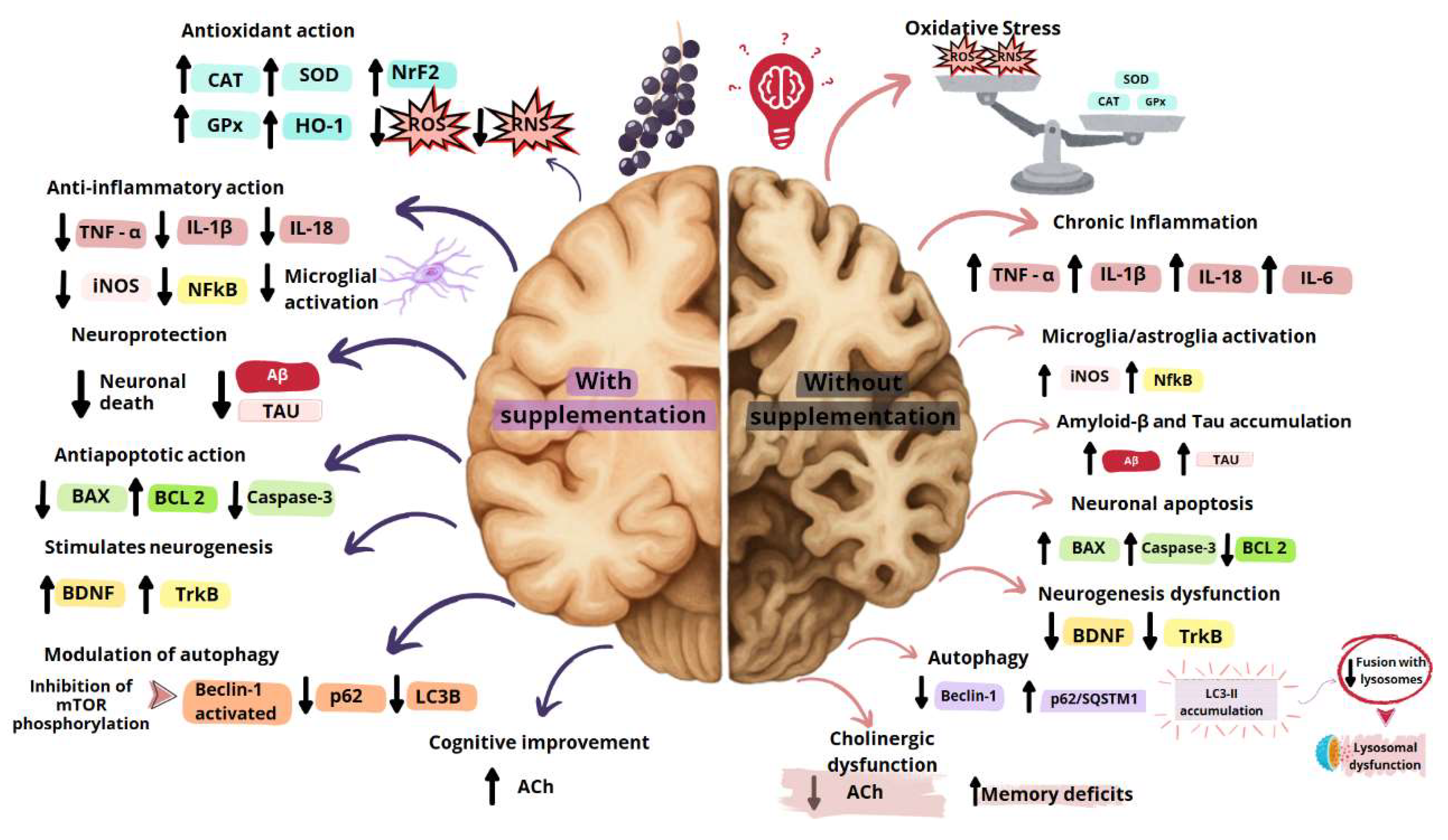

3. Euterpe oleracea Martius Actions on the Central Nervous System

3.1. Euterpe oleracea And Improved Cognition

3.2. Euterpe oleracea Antioxidant And Anti-Inflammatory Actions

3.3. Euterpe oleracea on Neurogenegis

3.4. Euterpe oleracea on Apoptosis

3.5. Euterpe oleracea on Autophagy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AD | Alzheimer disease |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| BAX | BCL-2-associated X protein |

| BCL-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CMA | Chaperone-mediated autophagy |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| L-NAME | Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOX-2 | NADPH-oxidoreductase-2 |

| VATPase | Vesicular or vacuolar ATPase |

References

- Grabska-Kobyłecka, I.; Szpakowski, P.; Król, A.; Książek-Winiarek, D.; Kobyłecki, A.; Głąbiński, A.; Nowak, D. Polyphenols and Their Impact on the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases and Development. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Sánchez, R.A.; Torner, L.; Fenton Navarro, B. Polyphenols and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Potential Effects and Mechanisms of Neuroprotection. Molecules 2023, 28, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, R.; Roy, A. Role of Medicinal Plants against Neurodegenerative Diseases. CPB 2022, 23, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ďuračková, Z. Some Current Insights into Oxidative Stress. Physiol Res 2010, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebatická, J.; Ďuračková, Z. Psychiatric Disorders and Polyphenols: Can They Be Helpful in Therapy? Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2015, 2015, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, S.Z.; Momtaz, S.; Bayrami, Z.; Farzaei, M.H.; Abdollahi, M. Nanoformulations of Herbal Extracts in Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, I.L.; Krucker, T.; Steffensen, S.; Akwa, Y.; Powell, H.C.; Lane, T.; Carr, D.J.; Gold, L.H.; Henriksen, S.J.; Siggins, G.R. Structural and Functional Neuropathology in Transgenic Mice with CNS Expression of IFN-α1Published on the World Wide Web on 17 March 1999.1. Brain Research 1999, 835, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugger, B.N.; Dickson, D.W. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2017, 9, a028035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Oloketuyi, S.F. A Future Perspective on Neurodegenerative Diseases: Nasopharyngeal and Gut Microbiota. J Appl Microbiol 2017, 122, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association 2015 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2015, 11, 332–384. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Liu, C.; Che, C.; Huang, H. Clinical Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioMed Research International 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, S.R.M.; Cunha, E.R.; Marques, I.L.; Paixão, S.A.; Dias, A.D.F.G.; Sousa, P.M.D.; Soares, N.D.K.P.; Sousa, M.O.; Lobato, R.M.; Souza, M.T.P.D. Doença de Alzheimer No Brasil: Uma Análise Epidemiológica Entre 2013 e 2022. RSD 2023, 12, e29412240345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia; 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003324-5.

- Bondi, M.W.; Edmonds, E.C.; Salmon, D.P. Alzheimer’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2017, 23, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria Lopez, J.A.; González, H.M.; Léger, G.C. Alzheimer’s Disease. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier, 2019; Vol. 167, pp. 231–255 ISBN 978-0-12-804766-8.

- Paschalidis, M.; Konstantyner, T.C.R.D.O.; Simon, S.S.; Martins, C.B. Trends in Mortality from Alzheimer’s Disease in Brazil, 2000-2019. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2023, 32, e2022886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathmann, K.L.; Conner, C.S. Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Features, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Drug Intelligence & Clinical Pharmacy 1984, 18, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpato, D.; Holzgrabe, U. Designing Hybrids Targeting the Cholinergic System by Modulating the Muscarinic and Nicotinic Receptors: A Concept to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2018, 23, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; Goate, A.M. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Challenge of the Second Century. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakey-Beitia, J.; González, Y.; Doens, D.; Stephens, D.E.; Santamaría, R.; Murillo, E.; Gutiérrez, M.; Fernández, P.L.; Rao, K.S.; Larionov, O.V.; et al. Assessment of Novel Curcumin Derivatives as Potent Inhibitors of Inflammation and Amyloid-β Aggregation in Alzheimer’s Disease. JAD 2017, 60, S59–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.P.; Aryal, P.; Robinson, S.; Rafiu, R.; Obrenovich, M.; Perry, G. Polyphenols in Alzheimer’s Disease and in the Gut–Brain Axis. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Yu, J.-T.; Tan, L.; Wang, Y.-L.; Sun, L.; Tan, L. Nutrition and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioMed Research International 2013, 2013, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Guo, J.; Ye, X.-Y.; Xie, Y.; Xie, T. Oxidative Stress: The Core Pathogenesis and Mechanism of Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Research Reviews 2022, 77, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, C.A.; Hardy, J.; Schott, J.M. Alzheimer’s Disease. Euro J of Neurology 2018, 25, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Hossen, M.A.; Chowdhury, M.F.I.; Bari, S.; Tamanna, N.; Sultana, S.S.; Haque, S.N.; Al Masud, A.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M. Aducanumab for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Psychogeriatrics 2023, 23, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd Haeberlein, S.; Aisen, P.S.; Barkhof, F.; Chalkias, S.; Chen, T.; Cohen, S.; Dent, G.; Hansson, O.; Harrison, K.; Von Hehn, C.; et al. Two Randomized Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022, 9, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedisano, F.; Maiuolo, J.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Nucera, S.; Scicchitano, M.; Scarano, F.; Bosco, F.; Macrì, R.; et al. The Potential for Natural Antioxidant Supplementation in the Early Stages of Neurodegenerative Disorders. IJMS 2020, 21, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.P.M.; Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; Sousa, M.A.V.; Madeira, S.V.F.; Sousa, P.J.C.; Tano, T.; Schini-Kerth, V.B.; Resende, A.C.; Soares de Moura, R. Endothelium-Dependent Vasodilator Effect of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (Açaí) Extracts in Mesenteric Vascular Bed of the Rat. Vascular Pharmacology 2007, 46, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.R.; Ribeiro, A.E.C.; Oliveira, É.R.; Garcia, M.C.; Soares Júnior, M.S.; Caliari, M. Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Freeze-Dried Açaí Pulp (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.). Food Sci. Technol 2020, 40, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolari, D.D.G. EMPRESA BRASILEIRA DE PESQUISA AGROPECUÁRIA Presidente Alberto Duque Portugal.

- Ulbricht, C.; Brigham, A.; Burke, D.; Costa, D.; Giese, N.; Iovin, R.; Grimes Serrano, J.M.; Tanguay-Colucci, S.; Weissner, W.; Windsor, R. An Evidence-Based Systematic Review of Acai ( Euterpe Oleracea ) by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. Journal of Dietary Supplements 2012, 9, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.K. de L.; Pereira, L.F.R.; Lamarão, C.V.; Lima, E.S.; da Veiga-Junior, V.F. Amazon Acai: Chemistry and Biological Activities: A Review. Food Chemistry 2015, 179, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.D.S.P.; Schwartz, G. Açaí— Euterpe Oleracea. In Exotic Fruits; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 1–5 ISBN 978-0-12-803138-4.

- Rogez, H.; Pompeu, D.R.; Akwie, S.N.T.; Larondelle, Y. Sigmoidal Kinetics of Anthocyanin Accumulation during Fruit Ripening: A Comparison between Açai Fruits (Euterpe Oleracea) and Other Anthocyanin-Rich Fruits. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2011, 24, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.K.; Alasalvar, C.; Shahidi, F. Superfruits: Phytochemicals, Antioxidant Efficacies, and Health Effects – A Comprehensive Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 59, 1580–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurindo, L.F.; Barbalho, S.M.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Mondal, A.; Bachtel, G.; Bishayee, A. Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) in Health and Disease: A Critical Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobato, F.H.S.; Ravena-Cañete, V. “O Açaí Nosso de Cada Dia”: Formas de Consumo de Frequentadores de Uma Feira Amazônica (Pará, Brasil). Ciências Sociais Unisinos 2020, 55, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Amorim, D.; Silva Amorim, I.; Campos Chisté, R.; André Narciso Fernandes, F.; Regina Barros Mariutti, L.; Teixeira Godoy, H.; Rosane Barboza Mendonça, C. Non-Thermal Technologies for the Conservation of Açai Pulp and Derived Products: A Comprehensive Review. Food Research International 2023, 174, 113575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheus, M.E.; Fernandes, S.B.D.O.; Silveira, C.S.; Rodrigues, V.P.; Menezes, F.D.S.; Fernandes, P.D. Inhibitory Effects of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. on Nitric Oxide Production and iNOS Expression. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2006, 107, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, S.M.; Fisher, D.R.; Larson, J.; Bielinski, D.F.; Rimando, A.M.; Carey, A.N.; Schauss, A.G.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Anthocyanin-Rich Açai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Fruit Pulp Fractions Attenuate Inflammatory Stress Signaling in Mouse Brain BV-2 Microglial Cells. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, T.A.F.M.; Souza, M.O.D.; Gomes, S.V.; Mendes E Silva, R.; Martins, F.D.S.; Freitas, R.N.D.; Amaral, J.F.D. Açaí ( Euterpe Oleracea Martius) Promotes Jejunal Tissue Regeneration by Enhancing Antioxidant Response in 5-Fluorouracil-Induced Mucositis. Nutrition and Cancer 2021, 73, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, D.; Siracusa, R.; D’Amico, R.; Fusco, R.; Cordaro, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Di Paola, R. Açaí Berry Ameliorates Cognitive Impairment by Inhibiting NLRP3/ASC/CASP Axis in STZ-Induced Diabetic Neuropathy in Mice. Journal of Neurophysiology 2023, 130, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira De Souza, M.; Silva, M.; Silva, M.E.; De Paula Oliveira, R.; Pedrosa, M.L. Diet Supplementation with Acai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Pulp Improves Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and the Serum Lipid Profile in Rats. Nutrition 2010, 26, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.O.; Souza E Silva, L.; De Brito Magalhães, C.L.; De Figueiredo, B.B.; Costa, D.C.; Silva, M.E.; Pedrosa, M.L. The Hypocholesterolemic Activity of Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Is Mediated by the Enhanced Expression of the ATP-Binding Cassette, Subfamily G Transporters 5 and 8 and Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Genes in the Rat. Nutrition Research 2012, 32, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.R.; Abreu, I.C.M.E.D.; Guerra, J.F.D.C.; Lage, N.N.; Lopes, J.M.M.; Silva, M.; Lima, W.G.D.; Silva, M.E.; Pedrosa, M.L. Açai ( Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Upregulates Paraoxonase 1 Gene Expression and Activity with Concomitant Reduction of Hepatic Steatosis in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2016, 2016, 8379105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Kang, J.; Burris, R.; Ferguson, M.E.; Schauss, A.G.; Nagarajan, S.; Wu, X. Açaí Juice Attenuates Atherosclerosis in ApoE Deficient Mice through Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Atherosclerosis 2011, 216, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, A.M.; Cardoso, A.C.; Pereira, B.L.B.; Silva, R.A.C.; Ripa, A.F.G.D.; Pinelli, T.F.B.; Oliveira, B.C.; Rafacho, B.P.M.; Ishikawa, L.L.W.; Azevedo, P.S.; et al. Açai Supplementation (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Attenuates Cardiac Remodeling after Myocardial Infarction in Rats through Different Mechanistic Pathways. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorato, V.N.; Miranda, D.C.D.; Isoldi, M.C.; Drummond, F.R.; Soares, L.L.; Reis, E.C.C.; Pelúzio, M.D.C.G.; Pedrosa, M.L.; Silva, M.E.; Natali, A.J. Effects of Aerobic Exercise Training and Açai Supplementation on Cardiac Structure and Function in Rats Submitted to a High-Fat Diet. Food Research International 2021, 141, 110168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, V.C.B.; Tavares, J.P.T.D.M.; Rosenstock, T.R.; Rodrigues, D.S.; Yudi, M.I.; Soares, J.P.M.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Sutti, R.; Torres, L.M.B.; De Melo, F.H.M.; et al. Increased Acute Blood Flow Induced by the Aqueous Extract of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. Fruit Pulp in Rats in Vivo Is Not Related to the Direct Activation of Endothelial Cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2021, 271, 113885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Souza, M.V.; Dos Santos, R.M.; Cerávolo, I.P.; Cosenza, G.; Ferreira Marçal, P.H.; Figueiredo, F.J.B. Euterpe Oleracea Pulp Extract: Chemical Analyses, Antibiofilm Activity against Staphylococcus Aureus, Cytotoxicity and Interference on the Activity of Antimicrobial Drugs. Microbial Pathogenesis 2018, 114, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, M.F.; Romualdo, G.R.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Barbisan, L.F. Açai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Feeding Attenuates Dimethylhydrazine-Induced Rat Colon Carcinogenesis. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 58, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragoso, M.F.; Romualdo, G.R.; Vanderveer, L.A.; Franco-Barraza, J.; Cukierman, E.; Clapper, M.L.; Carvalho, R.F.; Barbisan, L.F. Lyophilized Açaí Pulp (Euterpe Oleracea Mart) Attenuates Colitis-Associated Colon Carcinogenesis While Its Main Anthocyanin Has the Potential to Affect the Motility of Colon Cancer Cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 121, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.E.M.; Almeida-Souza, F.; Vale, A.A.M.; Victor, E.C.; Rocha, M.C.B.; Silva, G.X.; Teles, A.M.; Nascimento, F.R.F.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Chagas, M.D.S.D.S.; et al. Antitumor Effect of Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Seed Extract in LNCaP Cells and in the Solid Ehrlich Carcinoma Model. Cancers 2023, 15, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, M.F.; Prado, M.G.; Barbosa, L.; Rocha, N.S.; Barbisan, L.F. Inhibition of Mouse Urinary Bladder Carcinogenesis by Açai Fruit (Euterpe Oleraceae Martius) Intake. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2012, 67, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrazas, S.I.B.M.; Galan, B.S.M.; De Carvalho, F.G.; Venancio, V.P.; Antunes, L.M.G.; Papoti, M.; Toro, M.J.U.; Da Costa, I.F.; De Freitas, E.C. Açai Pulp Supplementation as a Nutritional Strategy to Prevent Oxidative Damage, Improve Oxidative Status, and Modulate Blood Lactate of Male Cyclists. Eur J Nutr 2020, 59, 2985–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.O.; Pala, D.; Silva, C.T.; De Souza, M.O.; Do Amaral, J.F.; Vieira, R.A.L.; Folly, G.A.D.F.; Volp, A.C.P.; De Freitas, R.N. Açai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Pulp Dietary Intake Improves Cellular Antioxidant Enzymes and Biomarkers of Serum in Healthy Women. Nutrition 2016, 32, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens-Talcott, S.U.; Rios, J.; Jilma-Stohlawetz, P.; Pacheco-Palencia, L.A.; Meibohm, B.; Talcott, S.T.; Derendorf, H. Pharmacokinetics of Anthocyanins and Antioxidant Effects after the Consumption of Anthocyanin-Rich Açai Juice and Pulp (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) in Human Healthy Volunteers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7796–7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro Volp, A.C. EL CONSUMO DE PULPA ACAI CAMBIA LAS CONCENTRACIONES DE ACTIVADOR DEL. NUTRICION HOSPITALARIA 2015, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranha, L.N.; Silva, M.G.; Uehara, S.K.; Luiz, R.R.; Nogueira Neto, J.F.; Rosa, G.; Moraes De Oliveira, G.M. Effects of a Hypoenergetic Diet Associated with Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Pulp Consumption on Antioxidant Status, Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Overweight, Dyslipidemic Individuals. Clinical Nutrition 2020, 39, 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira De Souza, M.; Barbosa, P.; Pala, D.; Ferreira Amaral, J.; Pinheiro Volp, A.C.; Nascimento De Freitas, R. A Prospective Study in Women: Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Martius) Dietary Intake Affects Serum p-Selectin, Leptin, and Visfatin Levels. Nutr Hosp 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, D.; Barbosa, P.O.; Silva, C.T.; De Souza, M.O.; Freitas, F.R.; Volp, A.C.P.; Maranhão, R.C.; Freitas, R.N.D. Açai ( Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Dietary Intake Affects Plasma Lipids, Apolipoproteins, Cholesteryl Ester Transfer to High-Density Lipoprotein and Redox Metabolism: A Prospective Study in Women. Clinical Nutrition 2018, 37, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udani, J.K.; Singh, B.B.; Singh, V.J.; Barrett, M.L. Effects of Açai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Berry Preparation on Metabolic Parameters in a Healthy Overweight Population: A Pilot Study. Nutr J 2011, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura, R.S.; Ferreira, T.S.; Lopes, A.A.; Pires, K.M.P.; Nesi, R.T.; Resende, A.C.; Souza, P.J.C.; Da Silva, A.J.R.; Borges, R.M.; Porto, L.C.; et al. Effects of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (AÇAÍ) Extract in Acute Lung Inflammation Induced by Cigarette Smoke in the Mouse. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, P.R.B.; da Costa, C.A.; de Bem, G.F.; Cordeiro, V.S.C.; Santos, I.B.; de Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; da Conceição, E.P.S.; Lisboa, P.C.; Ognibene, D.T.; Sousa, P.J.C.; et al. Euterpe Oleracea Mart.-Derived Polyphenols Protect Mice from Diet-Induced Obesity and Fatty Liver by Regulating Hepatic Lipogenesis and Cholesterol Excretion. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, V.; Carvalho, L.C.; de Bem, G.F.; Costa, C.A.; Sousa, P.J.C.; Souza, M.A.V.; Rocha, V.N.; José, J.; de Moura, R.S.; Resende, A.C. Euterpe Oleracea Mart. Extract Prevents Vascular Remodeling and Endothelial Dysfunction in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats.

- da Costa, C.A.; de Oliveira, P.R.B.; de Bem, G.F.; de Cavalho, L.C.R.M.; Ognibene, D.T.; da Silva, A.F.E.; dos Santos Valença, S.; Pires, K.M.P.; da Cunha Sousa, P.J.; de Moura, R.S.; et al. Euterpe Oleracea Mart.-Derived Polyphenols Prevent Endothelial Dysfunction and Vascular Structural Changes in Renovascular Hypertensive Rats: Role of Oxidative Stress. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol 2012, 385, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, C.A.; Ognibene, D.T.; Cordeiro, V.S.C.; De Bem, G.F.; Santos, I.B.; Soares, R.A.; De Melo Cunha, L.L.; Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; De Moura, R.S.; Resende, A.C. Effect of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. Seeds Extract on Chronic Ischemic Renal Injury in Renovascular Hypertensive Rats. Journal of Medicinal Food 2017, 20, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, P.R.B.; da Costa, C.A.; de Bem, G.F.; Marins de Cavalho, L.C.R.; de Souza, M.A.V.; de Lemos Neto, M.; da Cunha Sousa, P.J.; de Moura, R.S.; Resende, A.C. Effects of an Extract Obtained From Fruits of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. in the Components of Metabolic Syndrome Induced in C57BL/6J Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet: Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 2010, 56, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, I.B.; De Bem, G.F.; Da Costa, C.A.; De Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; De Medeiros, A.F.; Silva, D.L.B.; Romão, M.H.; De Andrade Soares, R.; Ognibene, D.T.; De Moura, R.S.; et al. Açaí Seed Extract Prevents the Renin-Angiotensin System Activation, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in White Adipose Tissue of High-Fat Diet–Fed Mice. Nutrition Research 2020, 79, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bem, G.F.; da Costa, C.A.; de Oliveira, P.R.B.; Cordeiro, V.S.C.; Santos, I.B.; de Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; Souza, M.A.V.; Ognibene, D.T.; Daleprane, J.B.; Sousa, P.J.C.; et al. Protective Effect of Euterpe Oleracea Mart (Açaí) Extract on Programmed Changes in the Adult Rat Offspring Caused by Maternal Protein Restriction during Pregnancy. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2014, 66, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.D.S.; Nunes, D.V.Q.; Carvalho, L.C.D.R.M.D.; Santos, I.B.; De Menezes, M.P.; De Bem, G.F.; Costa, C.A.D.; Moura, R.S.D.; Resende, A.C.; Ognibene, D.T. Açaí ( Euterpe Oleracea Mart) Seed Extract Protects against Maternal Vascular Dysfunction, Hypertension, and Fetal Growth Restriction in Experimental Preeclampsia. Hypertension in Pregnancy 2020, 39, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhena, J.C.; Lopes De Melo Cunha, L.; Jorge, T.M.; De Lucena Machado, M.; De Andrade Soares, R.; Santos, I.B.; Freitas De Bem, G.; Fernandes-Santos, C.; Ognibene, D.T.; Soares De Moura, R.; et al. Açaí Reverses Adverse Cardiovascular Remodeling in Renovascular Hypertension: A Comparative Effect With Enalapril. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 2021, 77, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, M.H.; De Bem, G.F.; Santos, I.B.; De Andrade Soares, R.; Ognibene, D.T.; De Moura, R.S.; Da Costa, C.A.; Resende, Â.C. Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Seed Extract Protects against Hepatic Steatosis and Fibrosis in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice: Role of Local Renin-Angiotensin System, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 65, 103726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, T.B.; Santos, I.B.; de Bem, G.F.; Ognibene, D.T.; da Rocha, A.P.M.; de Moura, R.S.; Resende, A. de C.; Daleprane, J.B.; da Costa, C.A. Therapeutic Effects of Açaí Seed Extract on Hepatic Steatosis in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice: A Comparative Effect with Rosuvastatin. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2020, 72, 1921–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes Arnoso, B.J.; Magliaccio, F.M.; De Araújo, C.A.; De Andrade Soares, R.; Santos, I.B.; De Bem, G.F.; Fernandes-Santos, C.; Ognibene, D.T.; De Moura, R.S.; Resende, A.C.; et al. Açaí Seed Extract (ASE) Rich in Proanthocyanidins Improves Cardiovascular Remodeling by Increasing Antioxidant Response in Obese High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2022, 351, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bem, G.F.; Da Costa, C.A.; Da Silva Cristino Cordeiro, V.; Santos, I.B.; De Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; De Andrade Soares, R.; Ribeiro, J.H.; De Souza, M.A.V.; Da Cunha Sousa, P.J.; Ognibene, D.T.; et al. Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (Açaí) Seed Extract Associated with Exercise Training Reduces Hepatic Steatosis in Type 2 Diabetic Male Rats. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2018, 52, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bem, G.F.; Costa, C.A.; Santos, I.B.; Cristino Cordeiro, V.D.S.; De Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; De Souza, M.A.V.; Soares, R.D.A.; Sousa, P.J.D.C.; Ognibene, D.T.; Resende, A.C.; et al. Antidiabetic Effect of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (Açaí) Extract and Exercise Training on High-Fat Diet and Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats: A Positive Interaction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Cristino Cordeiro, V.; de Bem, G.F.; da Costa, C.A.; Santos, I.B.; de Carvalho, L.C.R.M.; Ognibene, D.T.; da Rocha, A.P.M.; de Carvalho, J.J.; de Moura, R.S.; Resende, A.C. Euterpe Oleracea Mart. Seed Extract Protects against Renal Injury in Diabetic and Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats: Role of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Eur J Nutr 2018, 57, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade Soares, R.; de Oliveira, B.C.; de Bem, G.F.; de Menezes, M.P.; Romão, M.H.; Santos, I.B.; da Costa, C.A.; de Carvalho, L.C. dos R.M.; Nascimento, A.L.R.; de Carvalho, J.J.; et al. Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Seed Extract Improves Aerobic Exercise Performance in Rats. Food Research International 2020, 136, 109549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Soares, R.; Cardoso De Oliveira, B.; Dos Santos Ferreira, F.; Pontes De Menezes, M.; Henrique Romão, M.; Freitas De Bem, G.; Nascimento, A.L.R.; José De Carvalho, J.; Aguiar Da Costa, C.; Teixeira Ognibene, D.; et al. Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (Açai) Seed Extract Improves Physical Performance in Old Rats by Restoring Vascular Function and Oxidative Status and Activating Mitochondrial Muscle Biogenesis. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2023, 75, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, R.T.; Neto, M.L.; Monteiro, C.E.S.; Amaral, R.V.; Resende, Â.C.; Souza, P.J.C.; Zapata-Sudo, G.; Moura, R.S. Antinociceptive Effects of Hydroalcoholic Extract from Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (Açaí) in a Rodent Model of Acute and Neuropathic Pain. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.C.; Antunes, L.M.G.; Aissa, A.F.; Darin, J.D.C.; De Rosso, V.V.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Bianchi, M.D.L.P. Evaluation of the Genotoxic and Antigenotoxic Effects after Acute and Subacute Treatments with Açai Pulp (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) on Mice Using the Erythrocytes Micronucleus Test and the Comet Assay. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2010, 695, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Xie, C.; Li, Z.; Nagarajan, S.; Schauss, A.G.; Wu, T.; Wu, X. Flavonoids from Acai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Pulp and Their Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Food Chemistry 2011, 128, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, P.O.; Souza, M.O.; Silva, M.P.S.; Santos, G.T.; Silva, M.E.; Bermano, G.; Freitas, R.N. Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Martius) Supplementation Improves Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Liver Tissue of Dams Fed a High-Fat Diet and Increases Antioxidant Enzymes’ Gene Expression in Offspring. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 139, 111627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.S.; Ager, D.M.; Redman, K.A.; Mitzner, M.A.; Benson, K.F.; Schauss, A.G. Pain Reduction and Improvement in Range of Motion After Daily Consumption of an Açai ( Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Pulp–Fortified Polyphenolic-Rich Fruit and Berry Juice Blend. Journal of Medicinal Food 2011, 14, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.B.; Lichtenthäler, R.; Zimmermann, B.F.; Papagiannopoulos, M.; Fabricius, H.; Marx, F.; Maia, J.G.S.; Almeida, O. Total Oxidant Scavenging Capacity of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (Açaí) Seeds and Identification of Their Polyphenolic Compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4162–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, E.R.; Monteiro, E.B.; de Bem, G.F.; Inada, K.O.P.; Torres, A.G.; Perrone, D.; Soulage, C.O.; Monteiro, M.C.; Resende, A.C.; Moura-Nunes, N.; et al. Up-Regulation of Nrf2-Antioxidant Signaling by Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Extract Prevents Oxidative Stress in Human Endothelial Cells. Journal of Functional Foods 2017, 37, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.B.; Soares, E.D.R.; Trindade, P.L.; De Bem, G.F.; Resende, A.D.C.; Passos, M.M.C.D.F.; Soulage, C.O.; Daleprane, J.B. Uraemic Toxin-induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Human Endothelial Cells: Protective Effect of Polyphenol-rich Extract from Açaí. Experimental Physiology 2020, 105, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bem, G.F.; Okinga, A.; Ognibene, D.T.; da Costa, C.A.; Santos, I.B.; Soares, R.A.; Silva, D.L.B.; da Rocha, A.P.M.; Isnardo Fernandes, J.; Fraga, M.C.; et al. Anxiolytic and Antioxidant Effects of Euterpe Oleracea Mart. (Açaí) Seed Extract in Adult Rat Offspring Submitted to Periodic Maternal Separation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, E.B.; Borges, N.A.; Monteiro, M.; De Castro Resende, Â.; Daleprane, J.B.; Soulage, C.O. Polyphenol-Rich Açaí Seed Extract Exhibits Reno-Protective and Anti-Fibrotic Activities in Renal Tubular Cells and Mice with Kidney Failure. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 20855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira De Souza, M.; Barbosa, P.; Pala, D.; Ferreira Amaral, J.; Pinheiro Volp, A.C.; Nascimento De Freitas, R. A Prospective Study in Women: Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Martius) Dietary Intake Affects Serum p-Selectin, Leptin, and Visfatin Levels. Nutr Hosp 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, G.S.; Teles, A.M.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Chagas, M.D.S.D.S.; Behrens, M.D.; Moreira, W.F.D.F.; Abreu-Silva, A.L.; Calabrese, K.D.S.; Nascimento, M.D.D.S.B.; Almeida-Souza, F. Inhibitory Effect of Catechin-Rich Açaí Seed Extract on LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Cells and Carrageenan-Induced Paw Edema. Foods 2021, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.E.D.S.; De Cerqueira Fiorio, B.; Silva, F.G.O.; De Fathima Felipe De Souza, M.; Franco, Á.X.; Lima, M.A.D.S.; Sales, T.M.A.L.; Mendes, T.S.; Havt, A.; Barbosa, A.L.R.; et al. A Polyphenol-Rich Açaí Seed Extract Protects against 5-Fluorouracil-Induced Intestinal Mucositis in Mice through the TLR-4/MyD88/PI3K/mTOR/NF-κBp65 Signaling Pathway. Nutrition Research 2024, 125, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, T.S.; Brasil, A.; Leão, L.K.R.; Braga, D.V.; Santos-Silva, M.; Assad, N.; Luz, W.L.; Batista, E.D.J.O.; Bastos, G.D.N.T.; Oliveira, K.R.M.H.; et al. Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea) Pulp-Enriched Diet Induces Anxiolytic-like Effects and Improves Memory Retention. Food & Nutrition Research 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Monteiro, J.R.; Hamoy, M.; Santana-Coelho, D.; Arrifano, G.P.F.; Paraense, R.S.O.; Costa-Malaquias, A.; Mendonça, J.R.; Da Silva, R.F.; Monteiro, W.S.C.; Rogez, H.; et al. Anticonvulsant Properties of Euterpe Oleracea in Mice. Neurochemistry International 2015, 90, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, C.; Aydin, S.; Donertas, B.; Oner, S.; Kilic, F.S. Effects of Euterpe Oleracea to Enhance Learning and Memory in a Conditioned Nicotinic and Muscarinic Receptor Response Paradigm by Modulation of Cholinergic Mechanisms in Rats. Journal of Medicinal Food 2020, 23, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squire, L.R.; Alvarez, P. Retrograde Amnesia and Memory Consolidation: A Neurobiological Perspective. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 1995, 5, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, B.; Squire, L.R.; Kandel, E.R. Cognitive Neuroscience and the Study of Memory. Neuron 1998, 20, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, A.R.; Eichenbaum, H. Interplay of Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex in Memory. Current Biology 2013, 23, R764–R773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekdash, R.A. The Cholinergic System, the Adrenergic System and the Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. IJMS 2021, 22, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-R.; Huang, J.-B.; Yang, S.-L.; Hong, F.-F. Role of Cholinergic Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, A.N.; Miller, M.G.; Fisher, D.R.; Bielinski, D.F.; Gilman, C.K.; Poulose, S.M.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Dietary Supplementation with the Polyphenol-Rich Açaí Pulps ( Euterpe Oleracea Mart. and Euterpe Precatoria Mart.) Improves Cognition in Aged Rats and Attenuates Inflammatory Signaling in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Nutritional Neuroscience 2017, 20, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Dos Santos, N.; Batista, Â.G.; Padilha Mendonça, M.C.; Figueiredo Angolini, C.F.; Grimaldi, R.; Pastore, G.M.; Sartori, C.R.; Alice Da Cruz-Höfling, M.; Maróstica Júnior, M.R. Açai Pulp Improves Cognition and Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Mice. Nutritional Neuroscience 2024, 27, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, C.; Toro, P.; Schönknecht, P.; Sattler, C.; Schröder, J. Diabetes Mellitus Type II and Cognitive Capacity in Healthy Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Psychiatry Research 2016, 240, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, D.; D’Amico, R.; Fusco, R.; Genovese, T.; Peritore, A.F.; Gugliandolo, E.; Crupi, R.; Interdonato, L.; Di Paola, D.; Di Paola, R.; et al. Açai Berry Mitigates Vascular Dementia-Induced Neuropathological Alterations Modulating Nrf-2/Beclin1 Pathways. Cells 2022, 11, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, S.M.; Bielinski, D.F.; Carey, A.; Schauss, A.G.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Autophagy and Expression of Nrf2 in Hippocampus and Frontal Cortex of Rats Fed with Açaí-Enriched Diets. Nutritional Neuroscience 2017, 20, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Machado, F.; Marinho, J.P.; Abujamra, A.L.; Dani, C.; Quincozes-Santos, A.; Funchal, C. Carbon Tetrachloride Increases the Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Levels in Different Brain Areas of Wistar Rats: The Protective Effect of Acai Frozen Pulp. Neurochem Res 2015, 40, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, P.D.S.; Dani, C.; Bortolini, G.V.; Funchal, C.; Henriques, J.A.P.; Salvador, M. Frozen Fruit Pulp of Euterpe Oleraceae Mart. (Acai) Prevents Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Damage in the Cerebral Cortex, Cerebellum, and Hippocampus of Rats. Journal of Medicinal Food 2009, 12, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, S.M.; Fisher, D.R.; Bielinski, D.F.; Gomes, S.M.; Rimando, A.M.; Schauss, A.G.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Restoration of Stressor-Induced Calcium Dysregulation and Autophagy Inhibition by Polyphenol-Rich Açaí (Euterpe Spp.) Fruit Pulp Extracts in Rodent Brain Cells in Vitro. Nutrition 2014, 30, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Machado, F.; Kuo, J.; Wohlenberg, M.F.; Da Rocha Frusciante, M.; Freitas, M.; Oliveira, A.S.; Andrade, R.B.; Wannmacher, C.M.D.; Dani, C.; Funchal, C. Subchronic Treatment with Acai Frozen Pulp Prevents the Brain Oxidative Damage in Rats with Acute Liver Failure. Metab Brain Dis 2016, 31, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo, A.I.; Innamorato, N.G.; Martín-Moreno, A.M.; De Ceballos, M.L.; Yamamoto, M.; Cuadrado, A. Nrf2 Regulates Microglial Dynamics and Neuroinflammation in Experimental Parkinson’s Disease. Glia 2010, 58, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.R.; Johnson, J.A. The Nrf2–ARE Cytoprotective Pathway in Astrocytes. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2009, 11, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Wang, X. The Neuroprotective and Neurodegeneration Effects of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Alzheimer’s Disease. JAD 2020, 78, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandes, M.S.; D’Avila, J.C.; Trevelin, S.C.; Reis, P.A.; Kinjo, E.R.; Lopes, L.R.; Castro-Faria-Neto, H.C.; Cunha, F.Q.; Britto, L.R.; Bozza, F.A. The Role of Nox2-Derived ROS in the Development of Cognitive Impairment after Sepsis. J Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvanendran, S.; Kumari, Y.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Amelioration of Cognitive Deficit by Embelin in a Scopolamine-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-Like Condition in a Rat Model. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Gage, F.H. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Its Role in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2011, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjell, A.M.; McEvoy, L.; Holland, D.; Dale, A.M.; Walhovd, K.B. What Is Normal in Normal Aging? Effects of Aging, Amyloid and Alzheimer’s Disease on the Cerebral Cortex and the Hippocampus. Progress in Neurobiology 2014, 117, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castrén, E.; Kojima, M. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Mood Disorders and Antidepressant Treatments. Neurobiology of Disease 2017, 97, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanqueiro, S.R.; Ramalho, R.M.; Rodrigues, T.M.; Lopes, L.V.; Sebastião, A.M.; Diógenes, M.J. Inhibition of NMDA Receptors Prevents the Loss of BDNF Function Induced by Amyloid β. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.; Wuu, J.; Mufson, E.J.; Fahnestock, M. Precursor Form of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor and Mature Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor Are Decreased in the Pre-clinical Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Neurochemistry 2005, 93, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlenza, O.V.; Diniz, B.S.; Teixeira, A.L.; Radanovic, M.; Talib, L.L.; Rocha, N.P.; Gattaz, W.F. Lower Cerebrospinal Fluid Concentration of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Predicts Progression from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuromol Med 2015, 17, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.; Atlas, R.; Lange, A.; Ginzburg, I. Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor Induces a Rapid Dephosphorylation of Tau Protein through a PI-3Kinase Signalling Mechanism. Eur J of Neuroscience 2005, 22, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amidfar, M.; De Oliveira, J.; Kucharska, E.; Budni, J.; Kim, Y.-K. The Role of CREB and BDNF in Neurobiology and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Life Sciences 2020, 257, 118020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Bylykbashi, E.; Chatila, Z.K.; Lee, S.W.; Pulli, B.; Clemenson, G.D.; Kim, E.; Rompala, A.; Oram, M.K.; Asselin, C.; et al. Combined Adult Neurogenesis and BDNF Mimic Exercise Effects on Cognition in an Alzheimer’s Mouse Model. Science 2018, 361, eaan8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Pharmaceutical Potential. Transl Neurodegener 2022, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M.; Hof, P.R.; Šimić, G. Ceramides in Alzheimer’s Disease: Key Mediators of Neuronal Apoptosis Induced by Oxidative Stress and A βAccumulation. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2015, 2015, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Mora, P.; Luna, R.; Colín-Barenque, L. Amyloid Beta: Multiple Mechanisms of Toxicity and Only Some Protective Effects? Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2014, 2014, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsen, P.H.; Komatsu, H.; Murray, I.V.J. Oxidative Stress and Cell Membranes in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Physiology 2011, 26, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.H.; Zhao, M.; Anderson, A.J.; Srinivasan, A.; Cotman, C.W. Activated Caspase-3 Expression in Alzheimer’s and Aged Control Brain: Correlation with Alzheimer Pathology. Brain Research 2001, 898, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, C.M.; Akpan, N.; Jean, Y.Y. Regulation of Caspases in the Nervous System. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science; Elsevier, 2011; Vol. 99, pp. 265–305 ISBN 978-0-12-385504-6.

- Van Opdenbosch, N.; Lamkanfi, M. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Disease. Immunity 2019, 50, 1352–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.G.; Jänicke, R.U. Emerging Roles of Caspase-3 in Apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 1999, 6, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Song, Y.-Q.; Tu, J. Autophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis: Therapeutic Potential and Future Perspectives. Ageing Research Reviews 2021, 72, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare-shahabadi, A.; Masliah, E.; Johnson, G.V.W.; Rezaei, N. Autophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2015, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacurcio, D.J.; Nixon, R.A. Disorders of Lysosomal Acidification—The Emerging Role of v-ATPase in Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease. Ageing Research Reviews 2016, 32, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malampati, S.; Song, J.-X.; Chun-Kit Tong, B.; Nalluri, A.; Yang, C.-B.; Wang, Z.; Gopalkrishnashetty Sreenivasmurthy, S.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, J.; Su, C.; et al. Targeting Aggrephagy for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-T.; Zhou, B.; Lin, M.-Y.; Cai, Q.; Sheng, Z.-H. Axonal Autophagosomes Recruit Dynein for Retrograde Transport through Fusion with Late Endosomes. Journal of Cell Biology 2015, 209, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maday, S.; Wallace, K.E.; Holzbaur, E.L.F. Autophagosomes Initiate Distally and Mature during Transport toward the Cell Soma in Primary Neurons. Journal of Cell Biology 2012, 196, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Bourdenx, M.; Fujimaki, M.; Karabiyik, C.; Krause, G.J.; Lopez, A.; Martín-Segura, A.; Puri, C.; Scrivo, A.; Skidmore, J.; et al. The Different Autophagy Degradation Pathways and Neurodegeneration. Neuron 2022, 110, 935–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwiniuk, A.; Juszczak, G.R.; Stankiewicz, A.M.; Urbańska, K. The Role of Glial Autophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4528–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, C.; Leri, M.; Stefani, M.; Bucciantini, M. Autophagy-Related Proteins: Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers of Aging-Related Diseases. Ageing Research Reviews 2023, 89, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, B.L.; Teubner, B.J.W.; Boada-Romero, E.; Tummers, B.; Guy, C.; Fitzgerald, P.; Mayer, U.; Carding, S.; Zakharenko, S.S.; Wileman, T.; et al. Noncanonical Function of an Autophagy Protein Prevents Spontaneous Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Zhang, M.; Tong, L.; Morse, T.M.; McDougal, R.A.; Ding, H.; Chan, D.; Cai, Y.; Grutzendler, J. PLD3 Affects Axonal Spheroids and Network Defects in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2022, 612, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Yan, L.-J. Rapamycin, Autophagy, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Biochem Pharmacol Res 2013, 1, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spilman, P.; Podlutskaya, N.; Hart, M.J.; Debnath, J.; Gorostiza, O.; Bredesen, D.; Richardson, A.; Strong, R.; Galvan, V. Inhibition of mTOR by Rapamycin Abolishes Cognitive Deficits and Reduces Amyloid-β Levels in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamano, T.; Enomoto, S.; Shirafuji, N.; Ikawa, M.; Yamamura, O.; Yen, S.-H.; Nakamoto, Y. Autophagy and Tau Protein. IJMS 2021, 22, 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Ting, T.; Fan, Y.; Sadleir, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, S.; Levine, B.; Vassar, R.; et al. A Becn1 Mutation Mediates Hyperactive Autophagic Sequestration of Amyloid Oligomers and Improved Cognition in Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS Genet 2017, 13, e1006962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A.; Ojala, J.; Haapasalo, A.; Soininen, H.; Hiltunen, M. Impaired Autophagy and APP Processing in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Potential Role of Beclin 1 Interactome. Progress in Neurobiology 2013, 106–107, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experimental Model | Treatment | Mechanisms and Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male rats submitted to Scopolamine and Mecamylamine | Açaí pulp 100 and 300 mg/kg | Improved cognition and increased hippocampal acetylcholine | [96] |

| Male old rats and BV-2 cells | Açaí pulp 2% | Improved cognition, reduced microglial activation and NO levels | [102] |

| Male obesy mice | Açaí pulp 2% | Improved cognition, increased insulin sensitivity, adiponectin levels and antioxidant activity | [103] |

| Male mice with vascular dementia | Açaí pulp 500 mg/kg | Improved cognition, reduced apoptosis, restored autophagy and increased antioxidant activity in the hippocampus | [105] |

| BV-2 cells submitted to LPS | Açaí pulp 50, 125, 250, 500 and 1000 µg/mL | Reduced NO, iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α and NFkB | [40] |

| Male old rats | Açaí pulp 2% | Reduced NFkB and NOX-2 in the hippocampus. Increased NRF2 in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Elevated Beclin 1 expression in the prefrontal cortex | [106] |

| Male rats submitted to CCl4 | Açaí pulp 7 μL/g | Reduced TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-18 and oxidative stress in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and hippocampus | [107] |

| Cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and hippocampus homogenates from rats submitted to H2O2 | Açaí pulp 40% wt/vol | Reduced lipid peroxidation and protein carbonilation, increased SOD and CAT activity | [108] |

| Adult male offspring subjected to chronic maternal separation | Açaí seed extract 200 mg/kg | Reduced lipid peroxidation and protein carbonilation, increased SOD, GPx and CAT activity in the brainstem. Normalized NO levels and increased TRKB expression in the hippocampus | [89] |

| HT22 hippocampal cells | Açaí pulp 0.25 to 1 mg/mL | Restored autophagy | [109] |

| Abbreviations: BV-2 cells, microglial cells derived from C57/BL6 murine; NO, nitric oxide; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; NFkB, nuclear factor kappa B; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; NOX-2, NADPH-oxidoreductase-2; IL-1, interleukin 1 beta β; IL-18, interleukin 18; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; TRKB, tropomyosin receptor kinase B; HT22 cells, cell line derived from primary mouse hippocampal neurons; Beclin 1, protein that in humans is encoded by the BECN1 gene. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).