1. Development of Cancer

The cells of the living kingdom provide continuous oxygenation. In humans and vertebrates, this is achieved through respiration and blood flow. Cells die if they are deprived of oxygen. However, it is usually possible to restore the original state if the damage does not affect the whole body, but only part of it is lost due to injury/illness. The hypoxia-induced system controls the regeneration. It switches cell metabolism to the ancient energy system using aerobic glycolysis as described by Wartburg. Normally this system works very well. The oxygen-sensitive Hypoxia-Induced Factor (HIF) system converts the tissues to aerobic glycolysis metabolism, which develops new blood vessels, cleanses dead tissue, and restores the original state. In the case of hypoxia, the HIF system leads to a modulation of about 200 genes. The most important changes are: the induction of neovascularisation, induction of pluripotent cells, increased adhesion molecule expression and reduced sensitivity to apoptotic signals.

Cancer is a disease of tissue growth regulation. The genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation must be altered for a normal cell to become a cancer cell. Typically, changes in several genes are required to turn a normal cell into a cancer cell. Several mutations cause cancer.

Once cancer has started, this ongoing process, called clonal evolution, drives progression to more invasive stages. During tumour formation, the rapidly growing tumour cells lack sufficient blood vessels, and the limited capillary support often leads to hypoxia within the tumour cells. At this point, the failure to hydrolyse HIF-1α triggers malignant cells to become more malignant. A new type of tumour cell has been developed that adapts to the lack of oxygen. HIF-1α enables neovascularisation and tumour growth. By inducing adhesion molecules (which allow the destruction of dead tissue in wound healing), it is possible to develop the metastatic property of tumour cells. HIF-1α will lead to a specific Darwinian selection and will become the conductor of suicide evolution. Tumour progression is also favoured by the induction of pluripotency and reduced sensitivity to apoptosis.

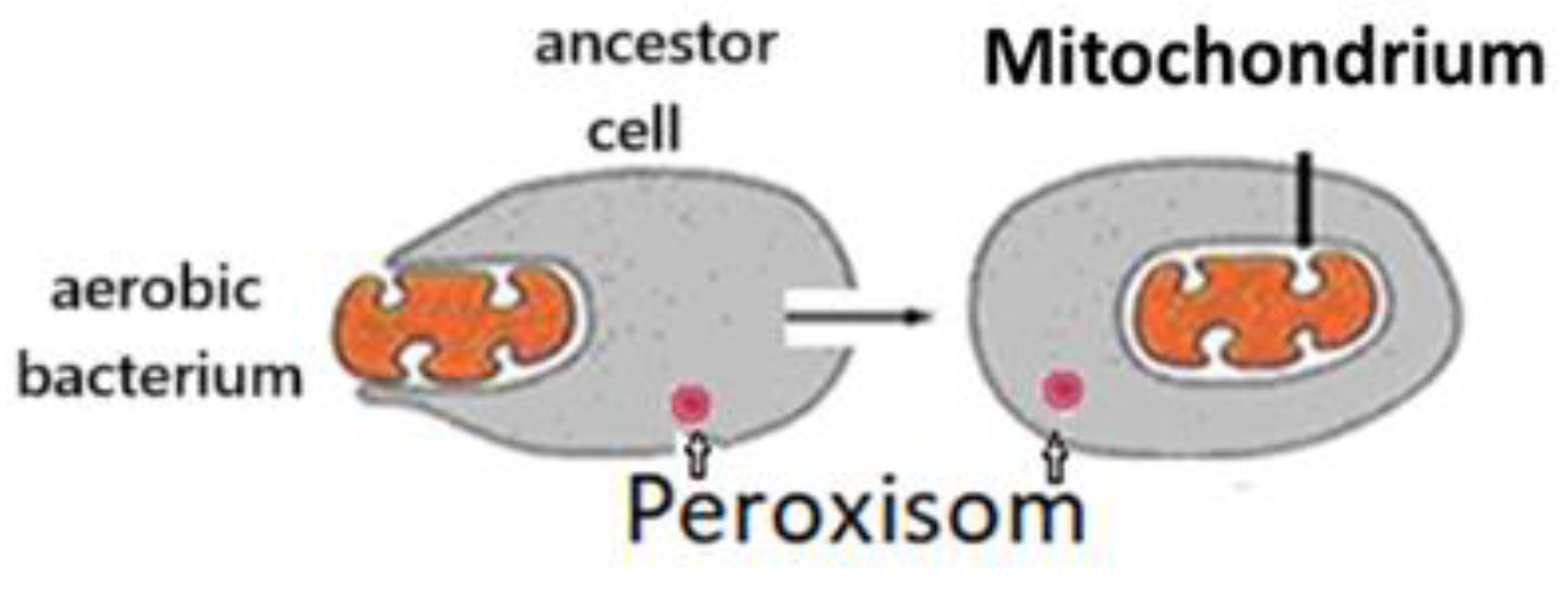

During the evolution of the living world, the development of the structure for energy conversion was one of the most critical determinants. Combining a cell living without O

2 with a cell using O

2 resulted in a qualitative advance. Lynn Margulis (1938-2011) suggested that the ancestor of eukaryotic cells avoided being destroyed by oxygen by entering into a symbiotic relationship with aerobic bacterium. This gave rise to the mitochondria of eukaryotes (

Figure 1) [

1]. Thus, eukaryotes have genetic material from both cells and can live in hypoxic and normoxic environments. All eukaryotic cells have mitochondria. Mitochondrial Pyruvate dehydrogenase results in an increased energy supply and effective protection against Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS).

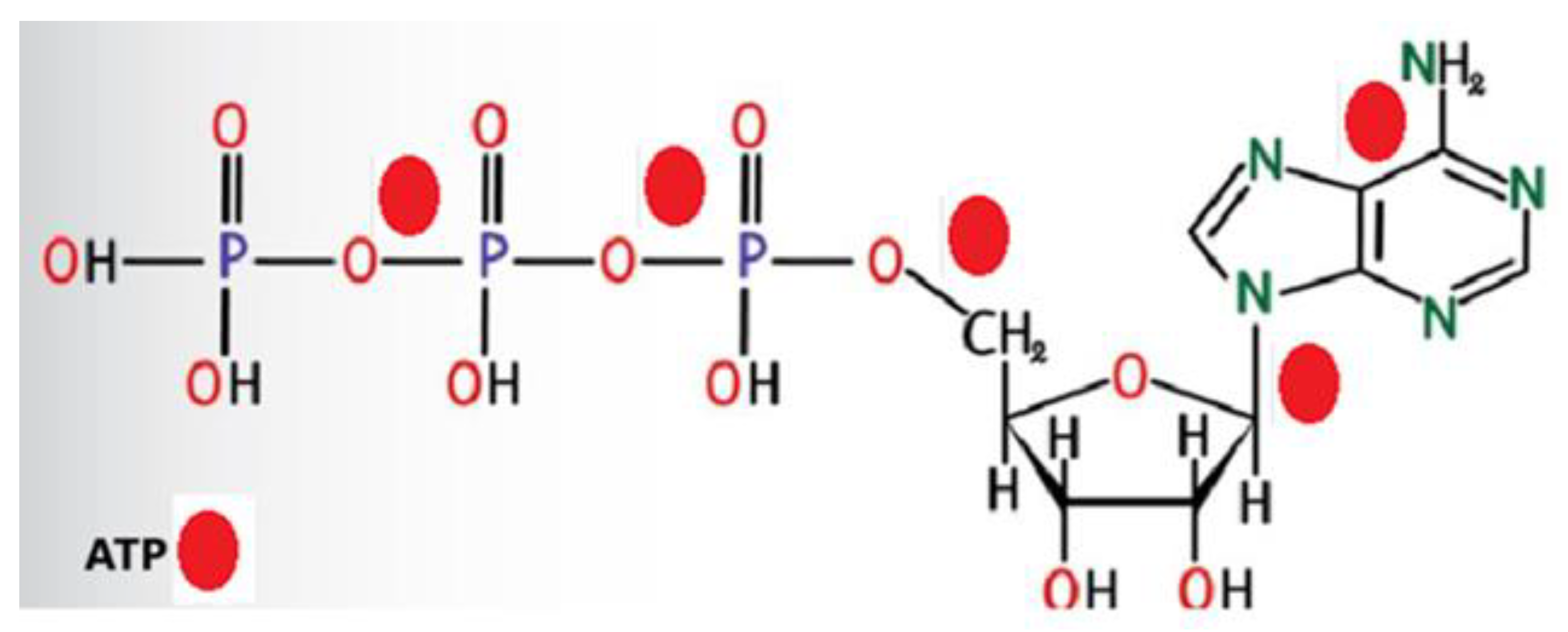

During energy conversion, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is formed from glucose. According to our hypothesis, the energy conversion is mediated by unique structures, the Structure of Energy Transformation for Aerobic Glycolysis (SET-AG) of the ancestor cell and the Structure of Energy Transformation for Oxidative Phosphorylation (SET-OP) of the mitochondrion. SET-AG is located in the peroxisomes. Understanding their function could be an important step towards optimising tumour therapy by glucose deprivation or intravenous vitamin C therapy.

Figure 1.

Symbiosis of ancestor cell with an aerobic cell.

Figure 1.

Symbiosis of ancestor cell with an aerobic cell.

Cancer is a group of diseases in which abnormal cell growth, invades and spreads to other parts of the body. There are more than 100 types of cancer, usually named after the organs or tissues in which the tumours form [

2].

Approximately 90-95% of cancers are caused by genetic mutations due to environmental and lifestyle factors. The remaining 5-10% are inherited [

3]. Common environmental factors contributing to cancer include diet and obesity (30-35%), tobacco (25-30%), infections (15-20%), radiation (both ionising and non-ionising, up to 10%), stress, physical inactivity and pollution [

3,

4]. Cancer is a disease of tissue growth regulation. Therefore, the genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation must be altered [

5]. The genes involved are oncogenes (genes that promote cell growth and reproduction) or tumour suppressor genes (genes that inhibit cell division and survival). Malignant transformation can occur through the formation of new oncogenes, the inappropriate overexpression of normal oncogenes, or the underexpression or silencing of tumour suppressor genes. Typically, changes in several genes are required to transform a normal cell into a cancer cell. Thus, a series of mutations causes cancer. In addition, each mutation slightly alters the behaviour of the cell [

6].

Replication of the information contained in the DNA of living cells can lead to mutations. Normal metabolic activity and environmental factors such as radiation can cause DNA damage in cells, resulting in up to 1 million individual molecular lesions per cell per day [

7]. Complex error correction and prevention are built into the cell’s defences against cancer. If a significant error occurs, the damaged cell can self-destruct through programmed cell death (apoptosis). If the error control processes fail, the mutated cell will survive and be passed on to daughter cells.

Some environments make it more likely that errors will occur and cancer will develop. Such environments may include disruptive substances called carcinogens, repeated physical injury, heat, ionising radiation or hypoxia. In this way, the errors that cause cancer are self-reinforcing and cumulative.

1.1. Protective options against malignant tumours

Living organisms are constantly defending themselves against harmful environmental factors. Specialised systems control both invaders and abnormally functioning cells. In animals (and humans), immune cells can usually recognise and destroy abnormal cells. Unfortunately, there are many situations in which malignant cells escape the control of the immune system and begin to multiply uncontrollably, leading to death.

Treatment options for malignant tumours are becoming more widespread. While surgery is the definitive treatment for early-stage tumours, the current therapies against advanced cancers do not yet provide effective, long-lasting control of the lesions and a satisfactory impact on patient survival. Thus, research is also focused on novel treatments that could potentiate the current therapies.

1.2. Controlling apoptosis

Apoptosis is the process of programmed cell death that can occur in multicellular organisms. Between 50 and 70 billion cells die by apoptosis every day in the average human adult. Binding of nuclear receptors by glucocorticoids, heat, nutrient deprivation, radiation, viral infection and hypoxia can trigger the release of intracellular apoptotic signals. Many cellular components, such as poly-ADP-ribose polymerase, can also facilitate the regulation of apoptosis [

8].

1.3. The chain reaction of cancer development

The transformation of a normal cell into cancer is a chain reaction caused by initial mistakes that compound into more serious mistakes, each of which allows the cell to escape more and more of the controls that regulate the growth of healthy tissue. This rebellious scenario, suicidal evolution, is an undesirable survival of the fittest tumour cell in which the driving forces of evolution work against the body’s design and enforcement of order. Once cancer has begun to develop, this ongoing process, known as clonal evolution, can lead to more invasive stages that result in death.

Clonal evolution leads to intra-tumour heterogeneity. The genetic properties and metabolism (oxidative phosphorylation or aerobic glycolysis) of tumour cells are different. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to develop effective treatment strategies.

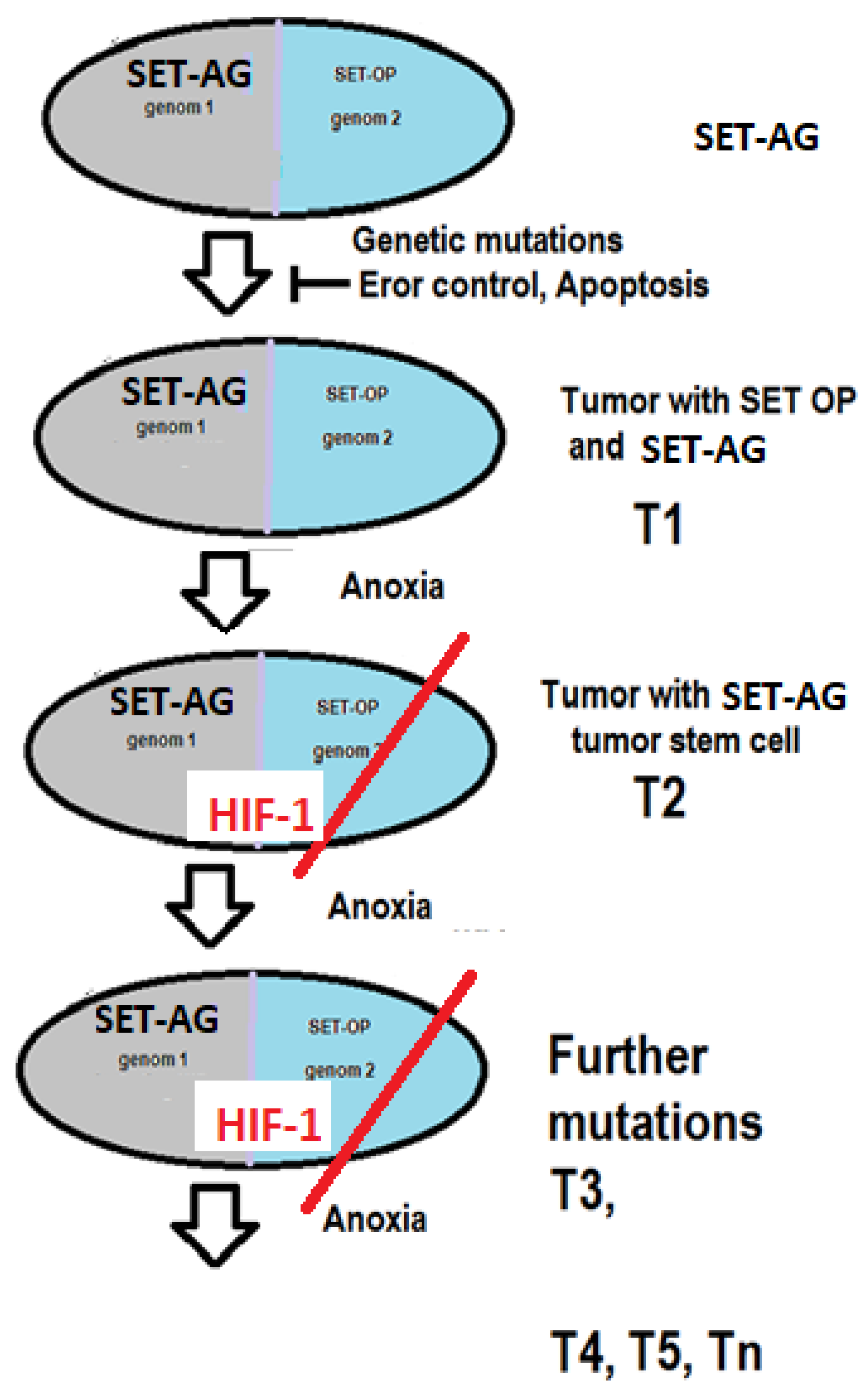

The first step in the development of a malignant tumour is the appearance of a mutant cell. The second problem is that the error control mechanism is altered. The mutant cell is not eliminated. The multiplying mutant cells are the precursor cells of the tumour (T1), using SET OP (

Figure 2). When the distance between the T1 containing growing tumour cells and the supplying blood vessel exceeds 70 nm [

9], the tissue partial pressure of O

2 (pO

2) is not sufficient for SET OP to function properly. At the same time, HIF-1 α will not be hydrolysed, resulting in the further development of the tumour, cells capable of living in an anoxic environment (tumour stem cells) will be created (T2). The system of HIF will lead to the further development of the tumour, creating tumour cells with new behaviours (T3, T4, Tn). There is competition between these cells. The majority of cancers are the most malignant cells.

Malignant tumours regularly send cells into the body through lymph and blood vessels. A cell’s ability to metastasise depends on its surface properties, which are influenced by unique adhesion molecules. As the tumour evolves, it may develop cells capable of forming metastases.

The HIF system initiates the induction of pluripotent cells, the expression of adhesion molecules and the installation of neovascularisation and reduced sensitivity to apoptotic signals. Thus, the HIF system is the conductor of tumour cells on the road to death (

Figure 2).

1.4. Vitamin C and Cancer

There is a large body of literature on the treatment of cancer with sugar withdrawal or vitamin C treatment. Despite several decades of research, their clinical efficacy has not been proven. The importance of this topic is reflected in the large number of clinical trials, both completed and ongoing. According to the literature, sugar deprivation and pharmacological doses of vitamin C kill tumour cells through reactive oxygen species (ROS). Both treatments, in vitro and animal experiments reproducibly destroy many tumour cells and tumours. However, the results of clinical trials are contradictory [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

2. The Supposed Way of Action Regarding Vitamin C Therapy

The earliest experience of using high-dose vitamin C (intravenous [i.v.] and oral) for cancer treatment was published by Cameron, and Campbell, in the 1970s [

17]. Later, Cameron and Pauling detected prolonged survival times in terminal human cancer by supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer [

18,

19]. In contrast, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Creagan, Moertel, and O’Fallon, et al. published the failure of High-dose Ascorbic Acid Therapy (HAAT) to benefit patients with advanced cancer [

20,

21,

22].

The serum level of AA is significantly lower after a high oral AA dose than after a high dose of i.v. AA [

23]. This difference explains the different results observed by Creagan and Cameron, as Creagan/Moertel used oral [

20,

21], while Cameron/Pauling used oral + parenteral AA [

17,

18,

19]. Although Cameron’s treatment was mainly oral therapy, they used i.v. AA as an initiation to the use of oral AA.

Pharmacologic ascorbate sensitizes cancer cells to damage by increasing intracellular L-ascorbate engagement through sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 (SVCT-2) acting as a pro-drug [

24]. HAAT is an aggressive adjunctive cancer treatment, widely used in naturopathic and integrative oncology settings, although it is not accepted as an effective drug for cancer patients by health authorities (FDA, EMA).

Until today, many publications have been available regarding the HAAT of malignant tumours. However, in vitro and animal experiments have proved AA’s pharmacological cytotoxic effect on cancer cells, while human clinical observations and studies show contradicting data. Thus, the Pauling–Moertel debate continues to this day.

2.1. The Biochemical Motor for Energy Transformation

Previously, we described a hypothetical structure, the SET, which might be responsible for the proper energy transformation, leading to the continuous membrane potential, production of H

+, and ATP in living cells [

25]. We suppose that the SET of aerobe glycolysis (SET-AG) is responsible for managing aerobic glycolysis, while the SET of oxidative phosphorylation (SET-OP) for the process of oxidative phosphorylation by Pyruvate dehydrogenase. The multiplex electron transfer chain (METC) is the basic structure of both SETs. The METC consists of 2 electron transfer chains (ETC)s, containing 2 X ten Fe-S clusters and 2 X four L-AA [

25].

2.2. Fe-S clusters, Cysteine

2.2.1. Fe-S clusters

Many Fe-S clusters are known in organometallic chemistry as precursors to synthetic analogues of the biological clusters. In the simplest polymetallic system, the [Fe2S2] cluster comprises two iron ions bridged by two sulfide ions and coordinated by four cysteine ligands (in Fe2S2 ferredoxins).

The most abundant Fe-S clusters are of the rhombic [Fe2-S2] and cubic [Fe4-S4] types, but [Fe3–S4], [Mo-Fe3–S4], [Fe4–S3] and [Fe8-S7] clusters of nitrogenase have also been described.

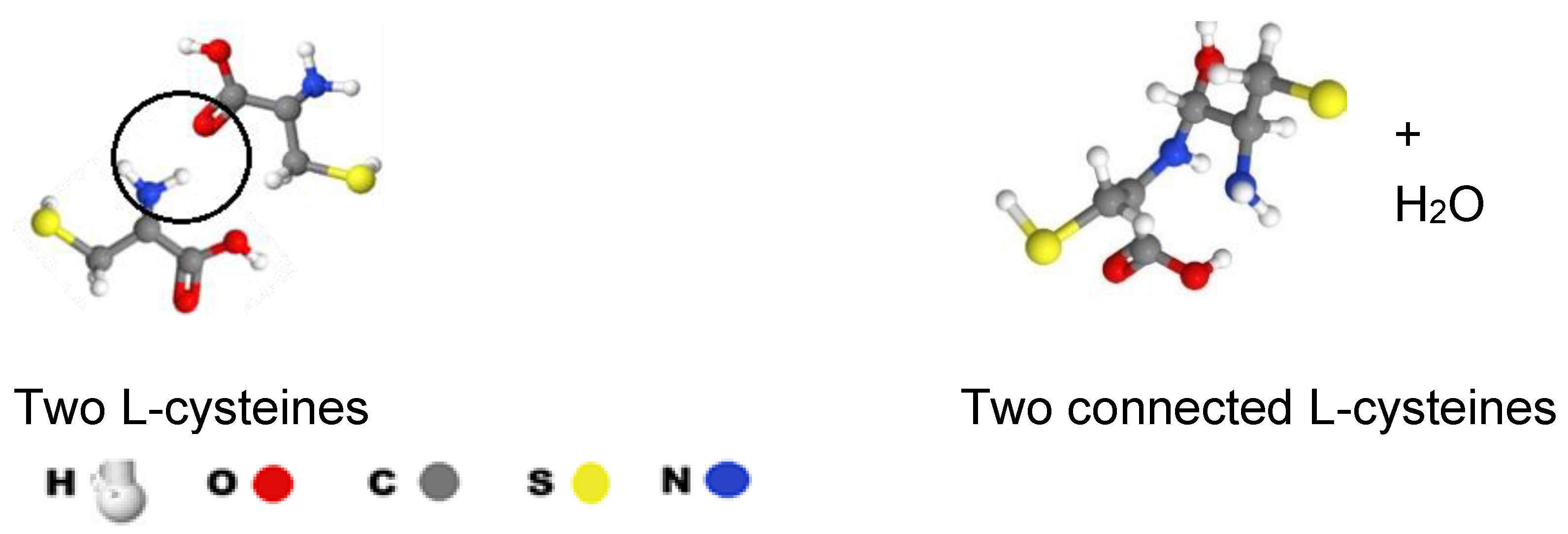

2.2.2. Cystein

Cysteine (Cys) is a semi-essential proteinogenic amino acid with the formula HOOC−CH(−NH

2)−CH

2−SH (

Figure 3). Cys is a deterministic part of all Fe-S clusters, as it provides the continuity of the electron transfer in the METC, (

Figure 3). We suppose the 2 x 10 Fe-S clusters create a continuous electron chain by connecting through their cys parts. Two cys of two Fe-S clusters can create continuity between clusters as presented in

Figure 3. The Nitrogen-Oxygen connection results in N-C bound + H

2O while one C-NH

2 and one C=O will remain.

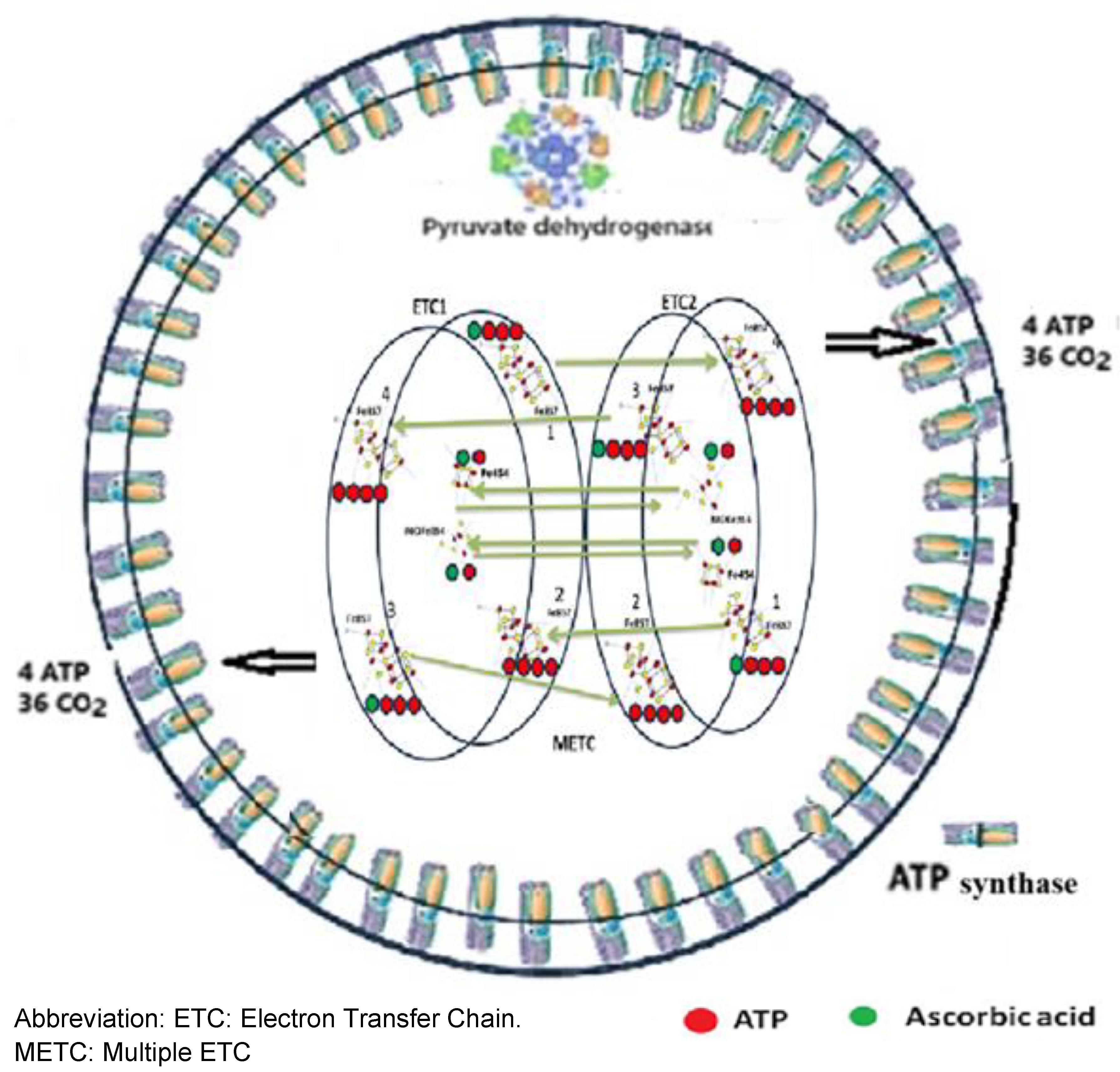

3. The Continuous Electron Transfer

3.1. The Structure of Energy Transformation

The condition for life is a continuous flow of electrons ensured by a complex electron transfer chain.

The Fe-S clusters are connected by cys-S bounds, forming one METC, where the energy transformation is completed. We suppose that the METC contains two ETCs. One ETC has four [Fe

8-S

7], four [Fe

2-S

2], one [Fe

4-S

4], and one molybdenum iron sulfide [MoFe

3-S

4] cluster (

Figure 4).

The connection of the two ETCs results in electron transfer mediated by 8 AA. (

Figure 5).

Each ETC produces 32 PO33-s, 64 H+, 24 CO2, and 4 ATP (Table I).

Table I. Results of structures of energy transformations in the electron transfer chain

Table I. Results of structures of energy transformations in the electron transfer chain

| Fe-S clusters |

Results of the structures

|

| |

NH2-UA |

adenine |

Pi |

H+

|

CO2

|

ribose

|

acetic acid |

Pyru-vate |

new ADP |

ATP |

| 4 Fe8-S7

|

4 |

4 |

8 |

16 |

12 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

new 4 |

| 4 Fe2-S2

|

|

|

16 |

32 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

ADP-ATP

20 |

| 1 Fe4-S4

|

|

|

4 |

8 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

| 1 MoFe3-S4

|

|

|

4 |

8 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

| ETC |

4 |

|

32 |

64 |

24 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

24 |

3.2. Oxygen binding points of the multiplex electron transfer chain.

The [Fe

8S

7(C

3H

7NO

2S)

6]

2- clusters obtain six cys parts. It thus offers places for six oxygen-containing molecules. The cluster bounds one UA by the C6-positioned oxygen, two aminated UA by the C2 or C8-positioned oxygen, two H

2PO

4- and one NO molecule by the double-bonded oxygen of the molecules (

Figure 6).

Oxygen-containing molecules will replace the sulphur atoms after the ETC is initiated. The ETC has 48 cys structures. The four Fe8-S7 clusters contain 6x4=24, the four [Fe2-S2], the [MoFe3-S4], and the [Fe4-S4] clusters contain 6x4=24 cys, providing 48 oxygen binding points (Table II).

Four aminated uric acid molecules connected to nicotinamide and Flavine molecules link the four [Fe8S7 (SCH2CH3)6]e2- clusters of nitrogenase (Illustration 7). The four NO, four UA, eight D-glucose four F2S2, the F3S4, the Fe4S4 clusters and the 32 H2PO4- molecules are not presented.

3.3. Continuous electron flow and ATP production, the two steps of ATP production

The energy conversion process runs in the ETC. The first step produces aminated uric acid, PO

33-, H

+, CO

2, and ADP molecules. Finally, ATP synthase produces ATP from ADP + PO

33-[

24].

3.3.1. ATP-uric acid-ATP cycle

The view that UA is the end-product of ATP metabolism is widely accepted. Gounaris et al. Described that the hypoxanthine molecule could evolve as an effective capture of inorganic nitrogen species. These authors have also reported that hypoxanthine, the biochemical precursor of adenine and guanine, trapped nitrite ions and was reductively converted to adenine [

25]

We predict that UA is not an end-product but one element of an ATP – UA – NH2-UA– adenosine – ADP – ATP - UA cycle.

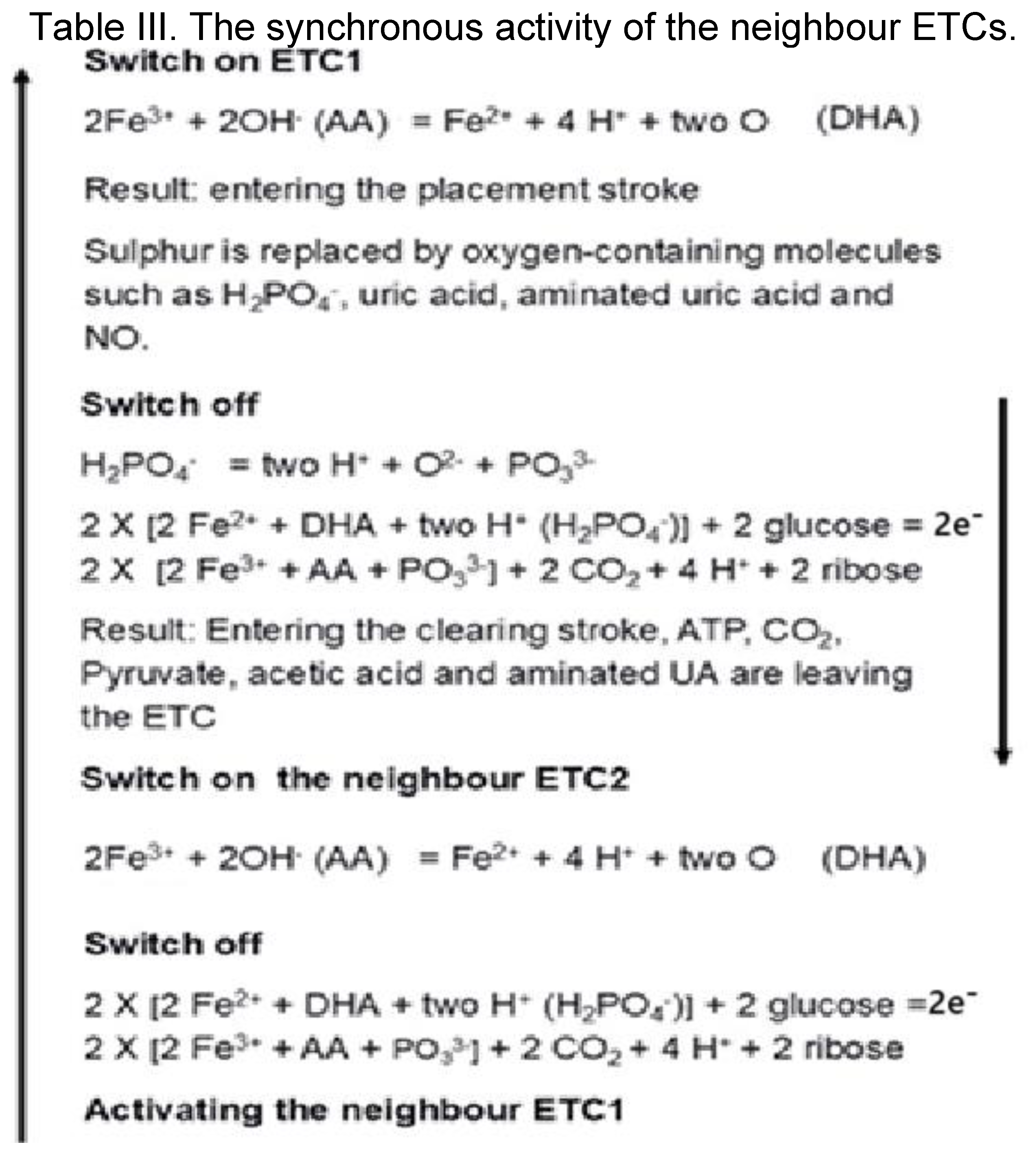

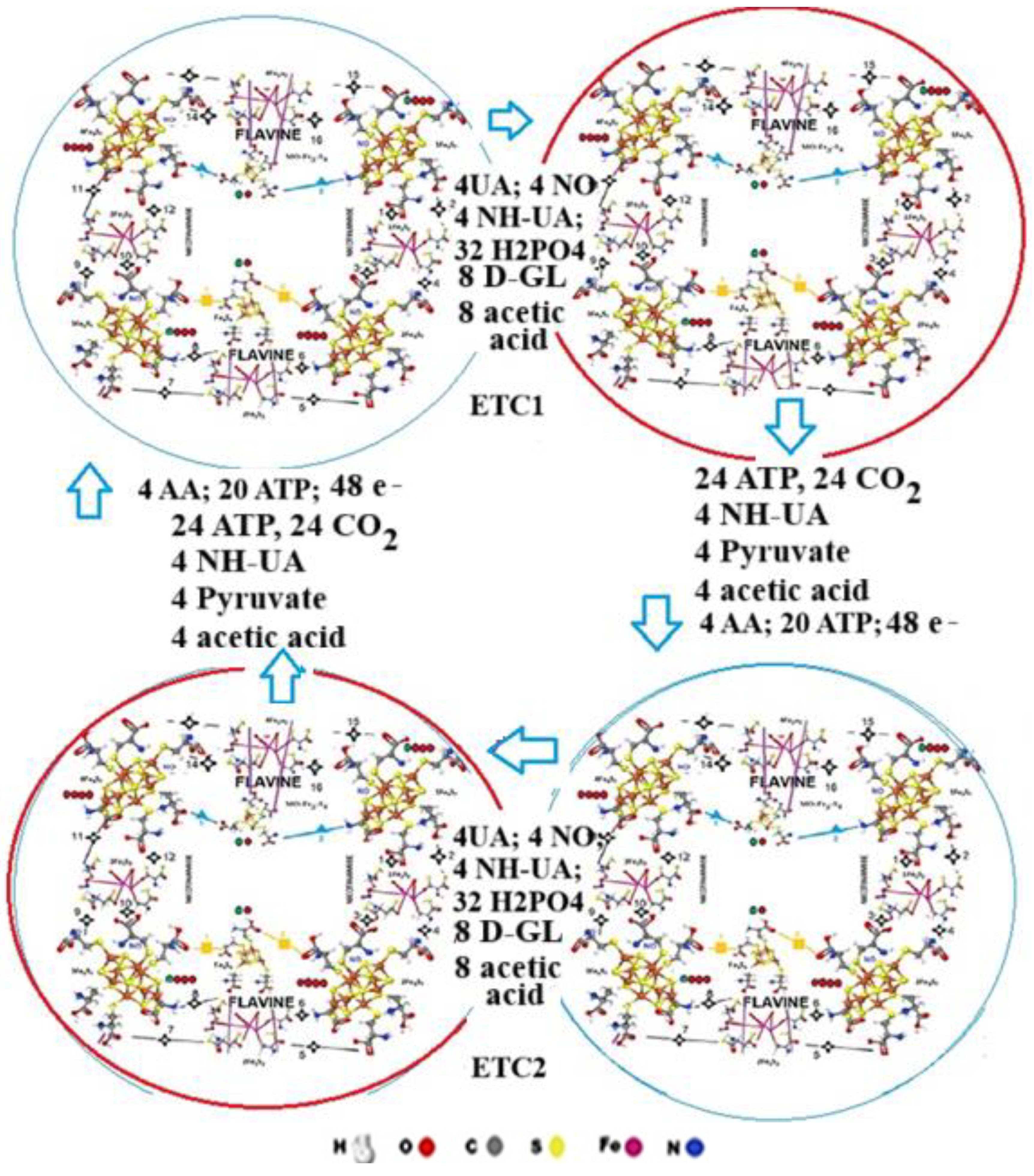

3.4. The synchronised activity of the neighbour ETCs.

The neighbour ETCs (ETC1 - ETC2) work synchronised. They mutually activate each other, resulting in continuous electron transfer (Table III). First, 20 ATP, and 3 AA initiates the ETC1 resulting in 4 UA, 4 aminated UA, 4 NO, 36 H

2PO

4 and 8 Glucose arrival. The electron flow consequences the energy transformation, resulting in 4 ADP, 24 PO

33-, 4 aminated UA, 4 Pyruvate and 4 acetic acid molecules. At the same time, the neighbour ETC2 will be activated, where the same reaction takes place, followed by the activation of ETC1 resulting in continuous electron flow (Table III;

Figure 8).

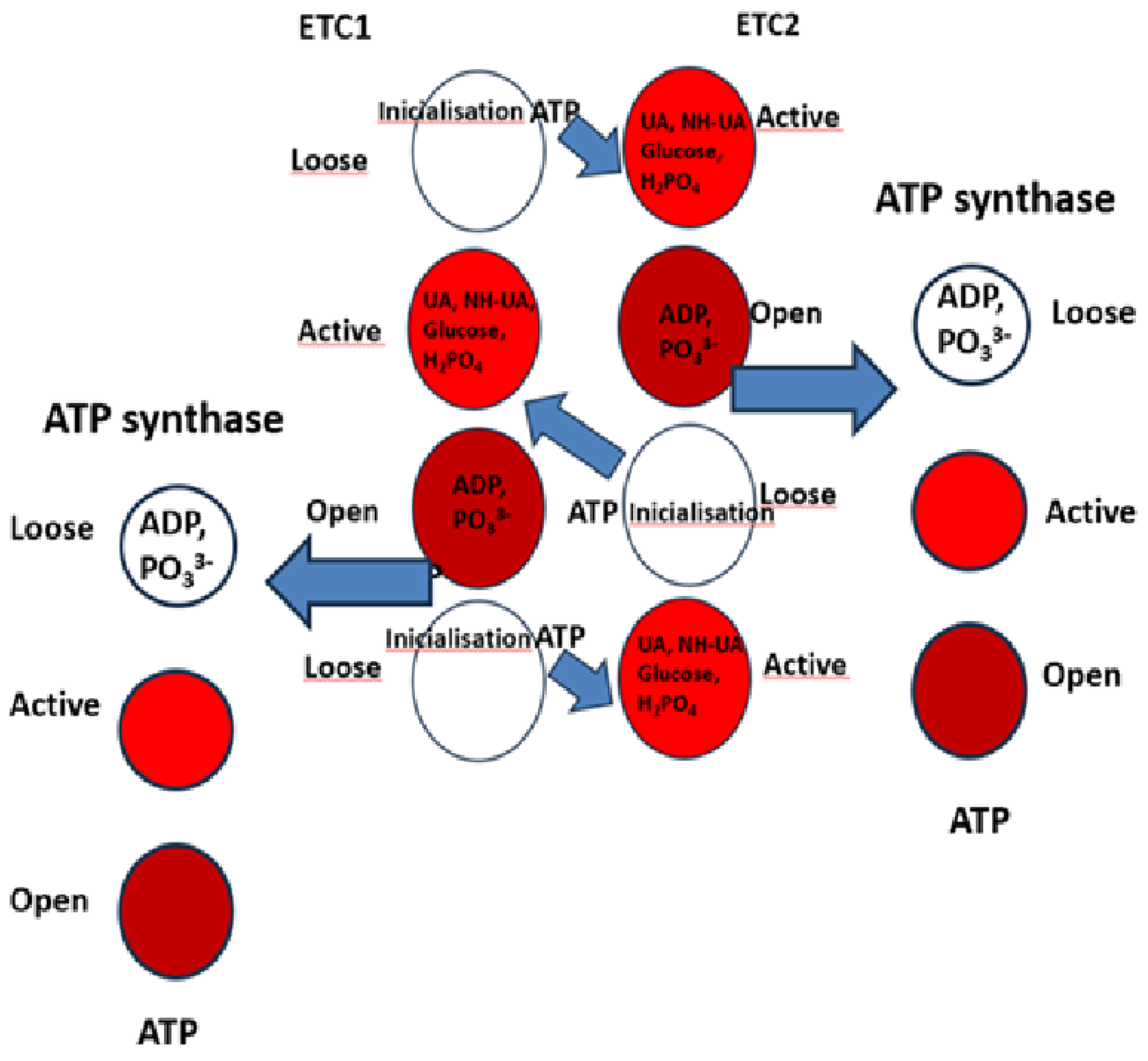

3.5. The three states of the electron transfer chains.

The energy transfer involves the active site of the two ETCs, cycling between three states.

Energy investment and initialisation.

First, AA and ATP molecules initiate the ETC1, wherein the “

loose” state, UA, NH-UA, Glucose, and H

2PO

4, enter the

active site; in

Figure 8 this is shown as an empty ring.

At the same time, the energy of the initiating ATP molecule will help the transformation in the ETC2. The ETC1 then undergoes a change and the transformation of these molecules, with the active site (shown in red) preparing the newly produced ADP molecule.

Finally, the active site cycles back to the

open state (brown), releasing ADP and being ready for the next cycle (

Figure 9). The ADP and phosphate, are forming ATP in the ATP synthase.

3.6. Structure for Energy Transformation of Aerobe Glycolysis

Two ETCs and the ATP synthase enzymes might form the METC, the SET-AG, which produces 2 X [four ATP, 64 H+ and 24 CO2 (Table I). The 48 O2- reacts with 24 carbons, producing 24 CO2. The carbon atom of the CO2 originates from the eight carbon atoms of the eight glucose and eight acetic acid molecules. ATP synthetase and many other specific enzymes are responsible for the proper function of the METC.

ATP and AA are determinants of the continuity of electron transfer. The energy investment results in 4 new ATP + 20 ADP molecules. The ADP molecules will be transformed into ATP in the ATP synthase using the energy obtained from the oxidation of 24 carbon atoms before the transformation ends.

3.7. The Structure of Energy Transformation for Oxidative Phosphorylation

The SET-OP consists of one SET-AG and Pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme, which is responsible for oxidative phosphorylation (

Figure 9).

3.8. The energy source for new ATP production.

The ETC converts 8 D-glucose to 4 new ATP, 4 acetic acid and 4 Pyruvate molecules. Building new ATP requires 5 ATP’s energy (

Figure 10). Twenty ATP are responsible for the 4 new ATP production, resulting in 20 ADP.

In the ETC, 20 ATPs start the reaction, producing 20 ADPs. During the transformation, 2 X 24 (SET-AG) or 2 X 36 (SET-OP) carbon atoms are oxidised, producing energy. This energy, together with the energy of the 20 ATP—ADP conversion, creates four new ATP molecules and regenerates the 20 ADP molecules.

3.9. Vitamin C and ATP are the activators and initiators of energy transformation.

Korth et al. published that vitamin C molecules are located in the pocket of NADPH, presumably at the adenine binding site of the inner mitochondrial membrane [

27].

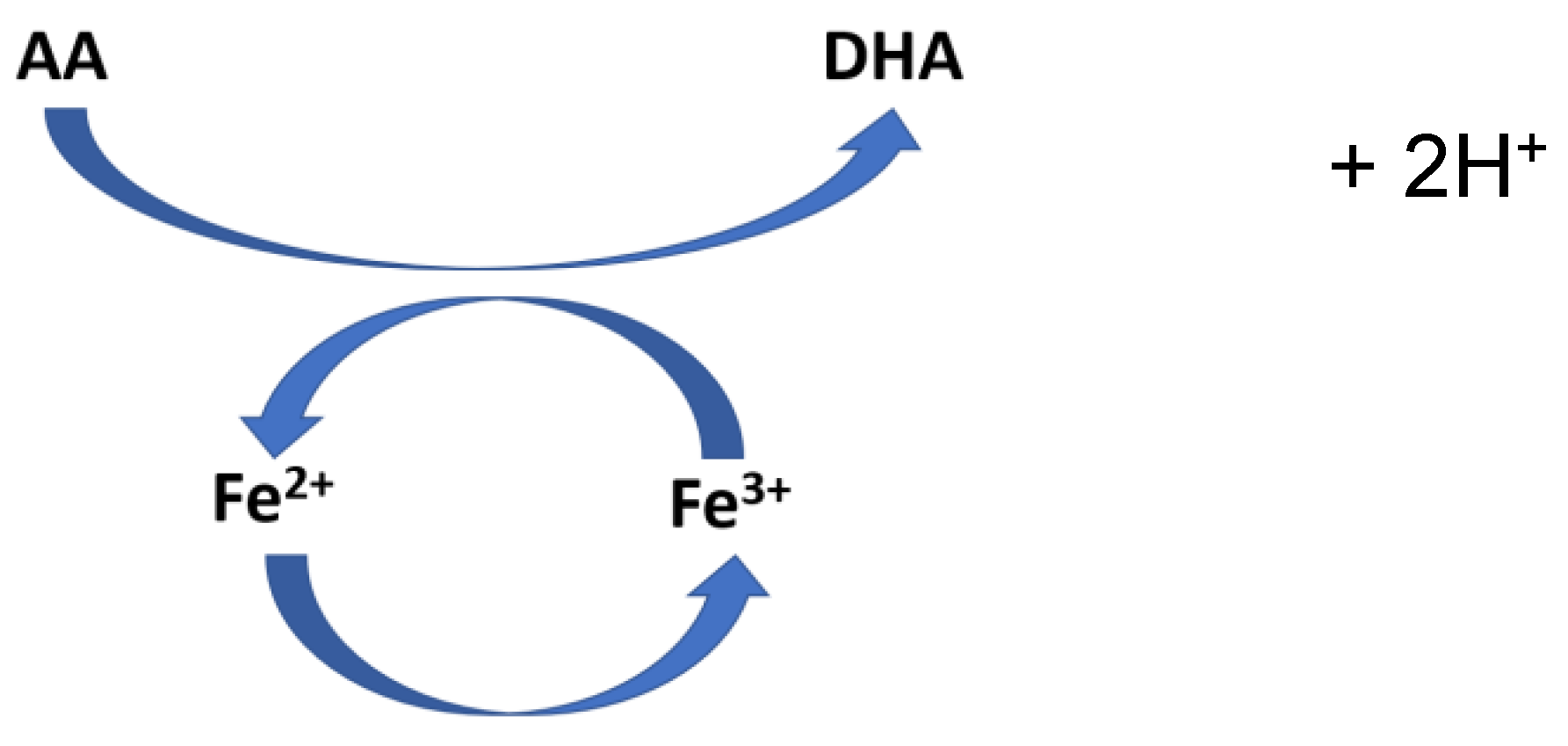

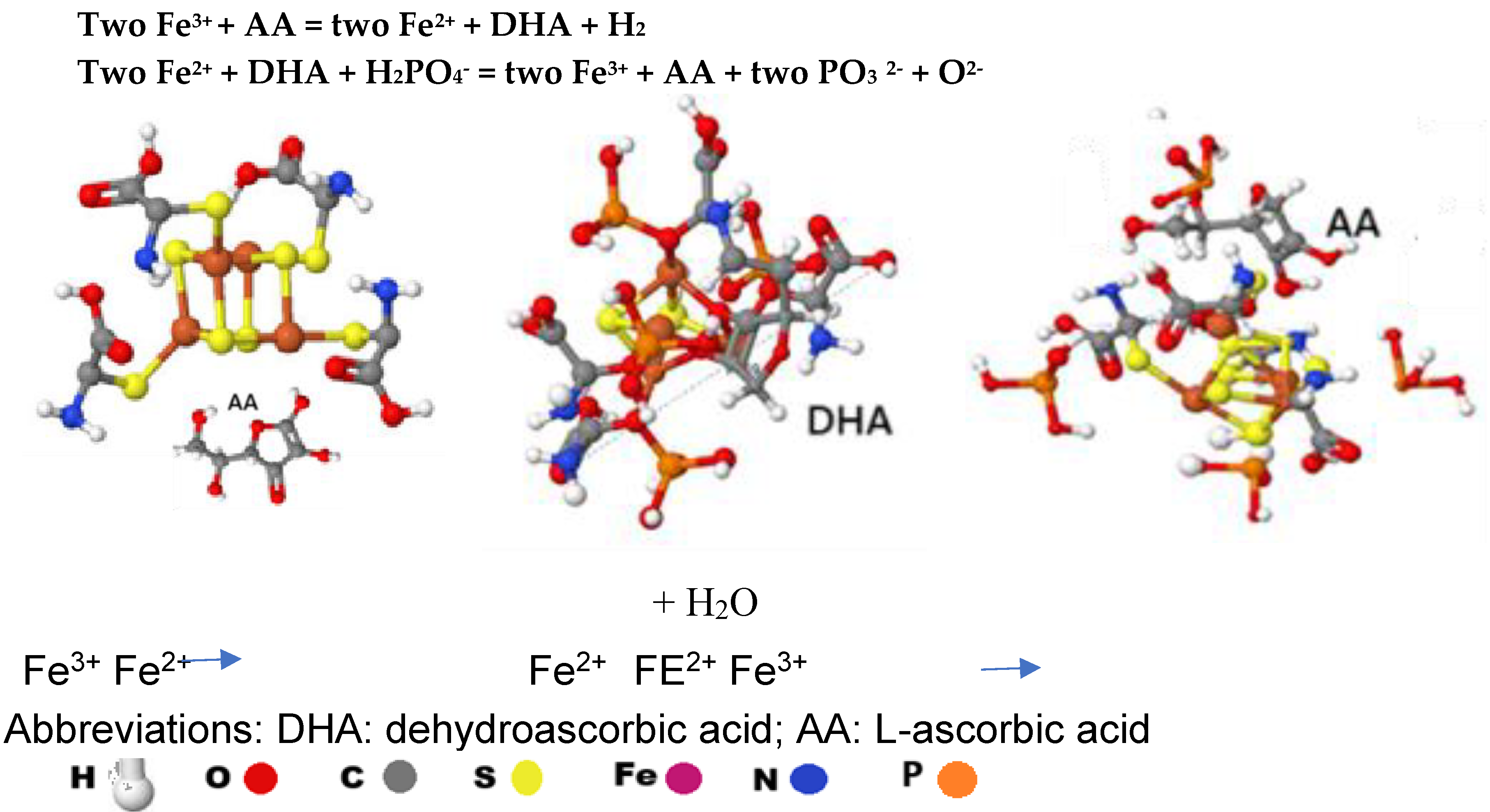

Kinga Linowiecka et al. stated that ascorbic acid (AA) is an oxidative stress sensor and a gene expression regulator. In addition, they pointed out that the change of AA to dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) regulates the modulation of the iron’s electron state in 2-oxoglutarate and Fe

2+ dependent dioxygenases (2-OGDD) (

Figure 11). Two H

+ are liberated during the AA – DHA transformation. AA crucially increases the rate of the reaction of 2-OGGD by targeting its catalytic domain and regenerating iron ions from Fe

3+ to Fe

2+ [

28].

This change might also be valid for the Fe atoms in the Fe-S clusters. The reaction results in a sulphur-oxygen exchange, creating four O2- in the Fe2-S2 cluster.

A similar reaction might occur when the two OHs of the ribose part of the ATP activate the Fe-S clusters.

Partially supported by this observation, we developed our hypothesis regarding the SETs. The four AAs and the 20 ATP in the ETC allow the conversion of Fe3+ to Fe2+, initiating the process leading to the production of ADP, PO33-, aminated uric acid and finally ATP.

Based on the publication by Kinga Linowiecka et al. [

28], we assume that a continuous AA- dehydro-AA - AA conversion could cause a change of Fe ions (Fe

3+ - Fe

2+ - Fe

3+) in the Fe-S clusters of ETCs, resulting in constant energy and ATP production and permanent maintenance of the membrane potential.

Figure 12 illustrates the Fe

3+ - FE

2+ change in a Fe4-S4 cluster.

Table IV Activation molecules of the Fe-S clusters

Table IV Activation molecules of the Fe-S clusters

| Fe-S Cluster |

ATP |

AA |

| [Fe8-S7] 1 |

3 |

1 |

| [Fe8-S7] 2 |

4 |

|

| [Fe8-S7] 3 |

3 |

1 |

| [Fe8-S7] 4 |

4 |

|

| [Fe2-S2] 1 |

1 |

|

| [Fe2-S2] 2 |

1 |

|

| [Fe2-S2] 3 |

1 |

|

| [Fe2-S2] 4 |

1 |

|

| [MoFe3-S4] |

1 |

1 |

| [Fe4-S4] |

1 |

1 |

| all |

20 |

4 |

Twenty ATP molecules activate the ETC, while four AAs initiate the reaction. Two OH of the ribose on the ATP bound to two Fe atoms of the Fe-S clusters, while the NH2 part of the ATP’s adenine will be bound to the C=O part of the connecting point. In that way, the 20 ATP molecules will bind 20 C=O of the connected cys. The C-NH parts of the connecting points bound 4 L-AA, 8 D-glucose and 8 acetic acid molecules.

3.10. The Proposed Way of Action by Parenteral AA on Sensitive Cancer Cells

Vitamin C enters the cell through SVCT-2 [

29] and changes the intracellular glucose/AA ratio. If the ratio of glucose to vitamin C changes and the ratio of glucose in the cell decreases, this can lead to cell death. O

2- is produced by sulphur-iron clusters at the start of the energy conversion process. If glucose is not available during the conversion, free radicals, which should produce CO

2 (glucose + 2 O

2- = ribose + CO

2), multiply in the cell. The catalase system neutralizes them. When the catalase system is exhausted, the free radicals kill the cell [

30]. Accordingly, several reports recommend the use of molecules that inhibit sugar transporters on the cell membrane [

31]. In addition, the effect of intravenous (IV) vitamin C gives better results with a ketogenic diet [

32].

The in vitro cytotoxic effect of ascorbic acid’s pharmacological concentration on cancer cells is mediated through a chemical reaction that generates H

2O

2 [

33]. In addition, ascorbic acid induces reactive oxygen species and impaired mitochondrial membrane potential [

34].

Our novel hypothesis regarding ATP synthesis via the Structure for Energy Transformation (SET) integrates known biochemical components. It remains a theoretical model that has not yet been empirically validated. The following limitations should be considered:

The SET hypothesis has not been tested through direct biochemical assays or in vivo experiments.

The role of Fe-S clusters, uric acid, and vitamin C in ATP synthesis within this framework is speculative and requires further experimental confirmation.

Although the hypothesis suggests a potential link between vitamin C metabolism and cancer treatment, no clinical studies have directly tested this mechanism.

Future research should aim to experimentally validate the SET model and assess its physiological relevance before clinical applications are considered.

3.11. Increasing the efficacy of high ascorbic acid cancer treatment

Caspase inhibitors, sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters (SVCT), glucose transporters (GLUT), ribose, and 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) might increase the efficacy of HAAT.

3.12. Caspase inhibitors

Caspases are an evolutionary conserved family of cysteine-dependent proteases that are actively involved in the execution of apoptosis. To date, fourteen mammalian caspases have been identified.

Multiple caspase inhibitors have been designed and synthesized as a potential therapeutic tool for the treatment of cell death-related pathologies. Their effect is based on the fact, that caspase helps the survival of sugar-deficient tumour cells [

30].

3.12.1. Sodium-Dependent Vitamin C Transporter

Lv, H et al. demonstrated that L-ascorbate has a selective killing effect influenced by SVCT-2 in human hepatocellular cancer cells [

29]. Furthermore, SVCT-2 expression was absent or weak in healthy tissues but strongly detected in tumour samples obtained from breast cancer patients, indicating that tumour cells contain elevated levels of AA [

35].

3.13. Glucose Transporters

Numerous observations suggest that starvation, ketogenic diet, and glucose transporter inhibition have antitumor activity, but clinical studies to support this are lacking.

The glucose entrance inside the cell occurs by facilitated diffusion and mainly depends on GLUTs. There are three different classes of GLUTs with tissue-specific distribution and distinct affinity for glucose and other carbohydrates. Class 1 comprises four members, GLUT1–LUT4, whose preferential substrate is glucose, and ribose, while the other two classes, class 2 (GLUT5) and 3 (GLUT6, 8, 10), are more selective for other sugars [

36].

GLUTs are expressed 10–12-fold higher in cancer cells than in healthy tissues, especially in highly proliferative and malignant tumours, contributing to the high glycolytic flux observed in this kind of tissue [

33]. GLUT1 and GLUT3, whose expression is regulated by HIF-1α, can be considered the main over-expressed isoforms in a wide range of human cancers [

37]. Moreover, they are correlated with poor prognosis and the radio-resistance of several types of human tumours. Hence, the activation of their expression can be considered a typical feature of the malignant phenotype. GLUT has a fundamental role in tumour cells of aerobic glycolysis. Thus, GLUT inhibition may represent an appealing way of attacking cancer by blocking its direct nutrient uptake, thus reducing the glycolytic flux and causing cell death by starvation and H

2O

2.

Antibodies [

36], antisense nucleic acids [

31,

38,

39], and synthetic small organic molecules showing GLUT-inhibitory properties, either alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs, have been reported [

40].

3.14. Treatment of Tumors by Influencing Glucose Metabolism

In most cancer cells, especially the most aggressive phenotypes, there is a substantial uncoupling of glycolysis from oxidative phosphorylation with the consequent production of high lactate levels (Warburg effect). This metabolic modification gives the tumour an evolutionary advantage, adapting to the local, more-or-less transient hypoxic conditions occurring during the disease’s progress. Furthermore, the remarkably higher glucose uptake also shows this metabolic preference by cancer cells through transmembrane glucose transporters, compensating for the higher energy demand of rapidly growing cells. Due to this feature, any enzyme or transporter promoting the glycolytic flux may be considered a potential target to block tumour progression [ 32, 33, 41].

Recently, human cancer cells were shown to be more susceptible to glucose deprivation-induced cytotoxicity and oxidative stress relative to non-transformed human cell types. These results indicated that some biochemical processes provided a mechanistic link between glucose metabolism and the expression of phenotypic characteristics associated with malignancy [

42].

The most direct way to target exaggerated aerobic glycolysis in tumours is to reduce glucose availability to cancer cells. It can be achieved through either dietary or pharmacological interventions. The pharmacologic influence might be realized either by controlling glucose uptake of the tumour cell by inhibiting glucose transporters or by inhibiting glycolytic enzymes [ 33, 41].

3.14.1. Short-Term Fasting

Short-term fasting (STF) 48 to 72 hours before chemotherapy appears to be more effective than intermittent fasting. Preliminary data show that STF is safe but challenging in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy.

Clinical trials should explore whether STF can reduce toxicity and increase the efficacy of chemotherapy regimens in daily practice [ 41].

3.14.2. Ketogenic Diet

The ketogenic diet consists of high fat, moderate to low protein, and extremely low carbohydrates. The goal is to develop ketosis in the body. It occurs when the body is forced to use fat for energy without glucose [

41].

3.14.3. Clinical Trials of Fasting

There is currently no concrete evidence that any of these fasting diets will benefit cancer patients. Clinical trials with more patients are still needed before fasting can be used in standard practice [

32,

33,

37,

41,

43].

3.15. Ribose - on melanoma cell line

The killing effect of potassium ascorbate with ribose (PAR) treatment on the human melanoma cell line, A375, in 2D and 3D models was published by Cavicchio et al. [

44]. In the 2D model, in line with the current literature, the pharmacological treatment with PAR decreased cell proliferation and viability. In addition, an increase in Connexin 43 mRNA and protein was observed. This novel finding was confirmed in PAR-treated melanoma cells cultured in 3D, where an increase in functional gap junctions and higher spheroid compactness was observed. Moreover, in the 3D model, a remarkable decrease in the size and volume of spheroids was observed, further supporting the treatment efficacy observed in the 2D model. In conclusion, these results suggest that PAR could be used as a safe adjuvant approach in support of conventional therapies for the treatment of melanoma.

3.15.1. Deoxy-D-Glucose

Increased pro-oxidant production and profound perturbations in thiol metabolism have been observed during glucose deprivation, suggesting that metabolic oxidative stress is induced [

43]. In addition, co-treatment with a thiol antioxidant could suppress glucose-deprivation-induced cytotoxicity [

45]. Lin et al. stated that 2DG is a potent inhibitor of glucose metabolism by mimicking glucose deprivation in vivo. When HeLa cells were exposed to 2DG (4-10 mM) for 4-72 h, cell survival decreased (20-90%) in a dose - and time-dependent fashion. When HeLa cells were treated with 6 mM 2DG for 16 h before ionizing radiation exposure, radio-sensitization was observed with a sensitiser enhancement ratio of 1.4 at 10% survival. Treatment with 2DG was also found to cause decreases in intracellular total glutathione content (50%) [

43].

Simultaneous treatment with the thiol antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC; 30 mM) protected HeLa cells against the cytotoxicity and radio-sensitizing effects of 2DG without altering radiosensitivity in the absence of 2DG. Furthermore, treatment with NAC partially reversed the 2DG-induced decreases in total glutathione content and augmented intracellular cysteine content.

These results support the hypothesis that exposure to 2DG causes cytotoxicity and radio-sensitization via a mechanism involving perturbations in thiol metabolism.

Lee et al. observed that glucose deprivation induces cell death in multidrug-resistant human breast carcinoma cells (MCF-7/ADR). Their results suggest that glucose deprivation-induced cytotoxicity and alterations in MAPK signal transduction are mediated by oxidative stress in MCF-7/ADR. These results also support the speculation that a common mechanism of glucose deprivation-induced cytotoxicity in mammalian cells may involve metabolic oxidative stress. [

43].

3.15.2. Flavonoids

Some natural products belonging to the family of flavonoids, which are polyphenolic compounds widely found in plants, exert inhibitory effects on glucose transporters. For example, naringenin, a flavanone found mainly in grapefruit and shown to bind selectively to the estrogen receptor beta [

46], has been reported to inhibit insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in breast cancer cells by interfering with insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane. A concentration of 100 μM naringenin inhibited glucose uptake by about 50% and cell proliferation by about 20% [

47]. Other flavonoids such as myricetin, fisetin, quercetin and its glycoside analogue isoquercitrin have been shown to inhibit GLUT2, an isoform primarily found in the intestine, with potential antidiabetic/antiobesity effects [

48]; however, no data are currently available on their effects on GLUT1 and GLUT3, which are the most exciting isoforms as anti-cancer targets.

3.16. Complex treatment of malignant tumours

Several mutations cause cancer. Normally, the immune system eliminates infected and cancerous cells. However, during this process, malignant cells stimulate the immune system. Tumour-derived peptides or proteins, together with costimulatory molecules and cytokines, are critical factors in the process of immune defence [

49,

50].

When immune defence is triggered, dendritic cells (DCs) take up and process tumour-derived peptides or proteins. After maturation, they present the peptide antigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and activate T cells specific for these antigenic epitopes. As a result of these processes, the T cells expand into short-lived effector and long-lived memory populations. Essentially, these T cells are ready to respond rapidly to subsequent antigenic encounters [

49,

51,

52],

Figure 13).

We investigated the dendritic cell-based active immunotherapies in patients with colorectal cancer patients using adoptively transferred DC-based immunotherapies. Our results indicate that vaccination by autologous DCs loaded with autologous oncolysates containing various tumour antigens represents a well-tolerated therapeutic modality in patients with colorectal cancer without any detectable adverse effects [

52].

Tumour destruction is only possible if the number of newly formed tumour cells grows more slowly than the number of destroyed cells. As this is a cell-to-cell reaction, the ratio of cancer cells to immune cells is crucial.

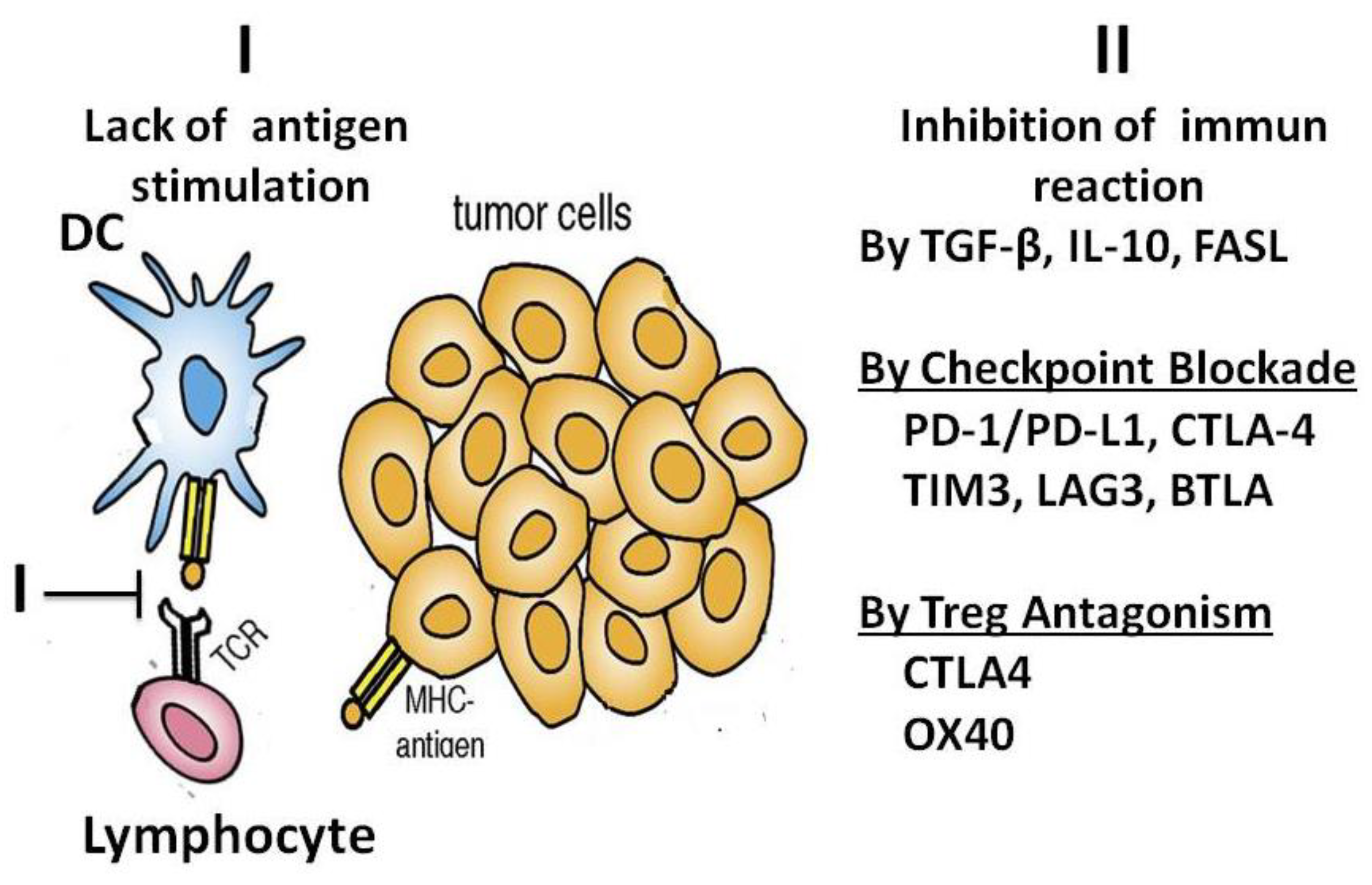

If cell-mediated immune stimulation fails, malignancy develops. Inhibition of the immune defence is another way in which cancer develops (

Figure 14).

Immune protection against cancer can be impaired for several reasons, such as

I: Failure of antigen processing;

II: Inhibition of immunity by TGF-β, IL-10 and fatty acid synthase ligand (FasL);

Checkpoint blockade by programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L-1), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), mucin domain containing-3 (TIM-3) protein, lymphocyte activation gene 3, as well as B- and T-lymphocyte-attenuator protein; Tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) secreting immunosuppressive factors and cytokines to block the activity of natural killer (NK) cells and CTLs.

Regulatory T cell (Treg) antagonism via CTLA-4 and OX40 (a secondary costimulatory immune checkpoint molecule). Tumour cells and host stromal cells (including fibroblasts and lymphatic endothelium) can also express TGF-β, checkpoint ligands and FasL to directly induce T-cell apoptosis).

Immunotherapy has excellent potential to treat cancer and prevent future recurrence by activating the immune system to recognise and kill cancer cells. Various strategies are being developed in the laboratory and the clinic, including therapeutic non-cellular (vector- or subunit-based) cancer vaccines and dendritic cell vaccines [

51,

52]. There is also evidence that many other factors, including age, sex, metabolic state, immune history and even gut microbiota, can influence the immune system [

53].

Engineered T cells [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64] and immune checkpoint blockade therapies have led to exciting recent clinical advances in cancer immunotherapy [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68].

Despite their promise, much more research is needed to understand how and why certain cancer patients fail to respond to immunotherapy and to predict which therapeutic strategies are best for a cancer patient. Many successful tumour therapies are based on this knowledge, but we are far from the final solution.

We believe the way to success is to treat patients as a whole. The aim is to reduce the tumour mass, stimulate the immune system and reverse the inhibition of the immune defence. In addition, the ratio of tumour cells to protective immune cells can influence the success of immunotherapy. It is therefore important to reduce the tumour mass. In addition to surgery, this can be achieved with X-rays and pharmacological vitamin C treatment.

Pharmacological vitamin C treatment kills tumour cells using Warburg’s aerobic glycolysis, mitotic cells are the primer targets, while cells with oxidative phosphorylation survive.

Inhibition of checkpoint blockade, complemented by dendritic cell immune stimulation and pharmacological vitamin C treatment, could be synergistic.