1. Introduction

Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) is a positive single-stranded RNA virus within the genus

Betacoronavirus in the

Coronaviridae family. The genus

Betacoronavirus includes, among other, human coronavirus (HCoV) OC43 and viruses associated with the two recent epidemics, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (MERS), as well as the pandemic SARS-CoV-2 [

1,

2].

BCoV circulates in cattle worldwide causing respiratory and enteric disease, but can also be detected in asymptomatic animals [

3,

4]. The virus is associated with three distinct clinical syndromes including calf diarrhea, winter dysentery (WD) with hemorrhagic diarrhea in adults, and bovine respiratory disease complex (BRDC) or shipping fever of feedlot cattle [

5,

6,

7,

8]. BCoV infection is characterized by high morbidity and mortality rates, resulting in significant losses in the livestock industry [

9,

10]. Although enteric and respiratory BCoV strains exhibit genetic differences at the spike gene level, only a single BCoV serotype has been identified to date, capable of conferring cross-protection among isolates [

11]. Therefore, enteric and respiratory isolates belong to the same quasispecies with variations in clinical signs likely resulting from interactions among the virus, host, and environment [

7,

12].

As members of the

Betacoronavirus genus, BCoV and SARS-CoV-2 share some common pathogenic features, and several studies have proposed the use of BCoV as a virus model to study SARS-CoV-2 [

3]. Sequence homology analysis of the aminoacidic sequence of spike and nucleocapsid proteins of BCoV and SARS-CoV-2 showed only 38.4% and 38.9% identity, respectively [

13,

14]. However, despite the low overall amino acid similarity, comparative analysis of the major antigenic epitopes of these proteins revealed a significantly higher degree of homology [

15].

Recent advancements in the pharmaceutical industry have highlighted the potential of natural compounds as antiviral agents [

16,

17] with nearly 80% of commercially available drugs derived from natural sources [

18]. Fungal secondary metabolites (SMs), in particular, are appreciated for their unique chemical structures and their diverse biological properties, including low molecular weight, structural diversity, and bioactivity [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Moreover, the industrial production of fungi-derived metabolites offers a cost-effective alternative to synthetic drug development [

24]. Recently, several studies have evaluated the antiviral activity of fungal SMs against animal and human viruses [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Among them, alpha-pyrones have been reported to exhibit protease inhibition activity [

29] and have been suggested as potential inhibitors of CoVs [

30].

In the present study, the antiviral activity of the fungal metabolite 6-pentyl-α-pyrone (6 PP) against BCoV was evaluated in vitro. The aim is to promote the research and development of antivirals for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection, using an animal model that allows preclinical studies aimed to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral drugs bypassing the difficulties and the risks deriving from the use of a highly pathogenic and contagious virus for humans in the first phases of screening. In addition, this study presents a novel and alternative strategy for the precise quantification of fluorescence, consistent with RT-qPCR results with several potential research applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production and Isolation of 6PP

6-Pentyl-α-pyrone (6PP) was isolated from

Trichoderma atroviride strain P1 according to the method described by Vinale et al. [

31]. Briefly, five 10mm Ø plugs, obtained from actively growing P1 cultures, were inoculated into 5L conical flasks containing 2.5L of potato dextrose broth (PDB, HI-MEDIA, Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). Two static cultures were incubated for 30 days at 25°C and then filtered under vacuum through Miracloth filter paper (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA).

Culture filtrates (5L) were exhaustively extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc, VWR International, LLC, Milan, Italy), the organic phase was dried with sodium sulfate anhydrous (Na2SO4, VWR International) and evaporated under vacuum at 37°C. Purification of 6PP was achieved by flash column chromatography (silica gel as stationary phase, 100g) with an elution gradient composed of petroleum ether (Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy) and EtOAc (0-100% EtOAc). Characterization of purified 6PP was achieved by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis according to the method reported by Staropoli et al. [

32].

2.2. Cell Culture and Virus

Madin Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco-MEM (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100IU/mL penicillin, 0,1mg/mL streptomycin and 2mM L-glutamine. DMEM was also employed for the antiviral assays.

BCoV strain 438/06, isolated from a 2–3-month-old cattle, was cultured and titrated in MDBK cells. The virus stock with a titer of 10-7 Tissue Culture Infectious Dose – TCID50/50μL was stored at −80 °C and used for the experiments.

2.3. Viral Titration

Ten-fold dilutions (up to 10-8) of each collected supernatant were titrated in quadruplicates in 24-well plates containing MDBK cells. The plates were incubated for 72h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment and then the cells were tested with the Indirect Immunofluorescence (IF) test using a specific bovine serum positive to BCoV and the anti-bovine IgG fluorescein conjugated serum (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO). The titer was expressed as the highest virus dilution showing fluorescent foci.

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of the 6PP was determined using the in vitro Cell Proliferation Kit (Sigma–Aldrich Srl, Milan, Italy), based on 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). The toxicity of the compound was measured on confluent monolayers of MDBK cells in 96-wells microtiter plates. Trypan Blue exclusion test as previously described [

33] was employed to assess cell viability, indicating non cytotoxic 6PP concentration of 0.1μg/mL. Based on these results, two-fold serial dilutions of the 6PP, from 0.25μg/mL to 0.002μg/mL, were performed to encompass the non-cytotoxic concentration within the range of tested values. The diluted compound was added to the 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 24h in a 5% CO2 incubator. After incubation, 10μL of MTT labeling reagent (0.5mg/mL) were added to each well for 4h at 37°C, and subsequently 100μL of solubilization buffer were added to solubilize the formazan crystals. The following day, the optical density (OD) was measured by an automatic spectrophotometer (iMark™ Microplate Absorbance Reader) at a wavelength of 570nm (with reference wavelength=655nm). Each experiment included a blank containing complete medium with untreated cells. 6PP cytotoxicity percentage was calculated according to the following formula: % Cytotoxicity = [(OD of control cells−OD of treated cells) ×100] / OD of control cells.

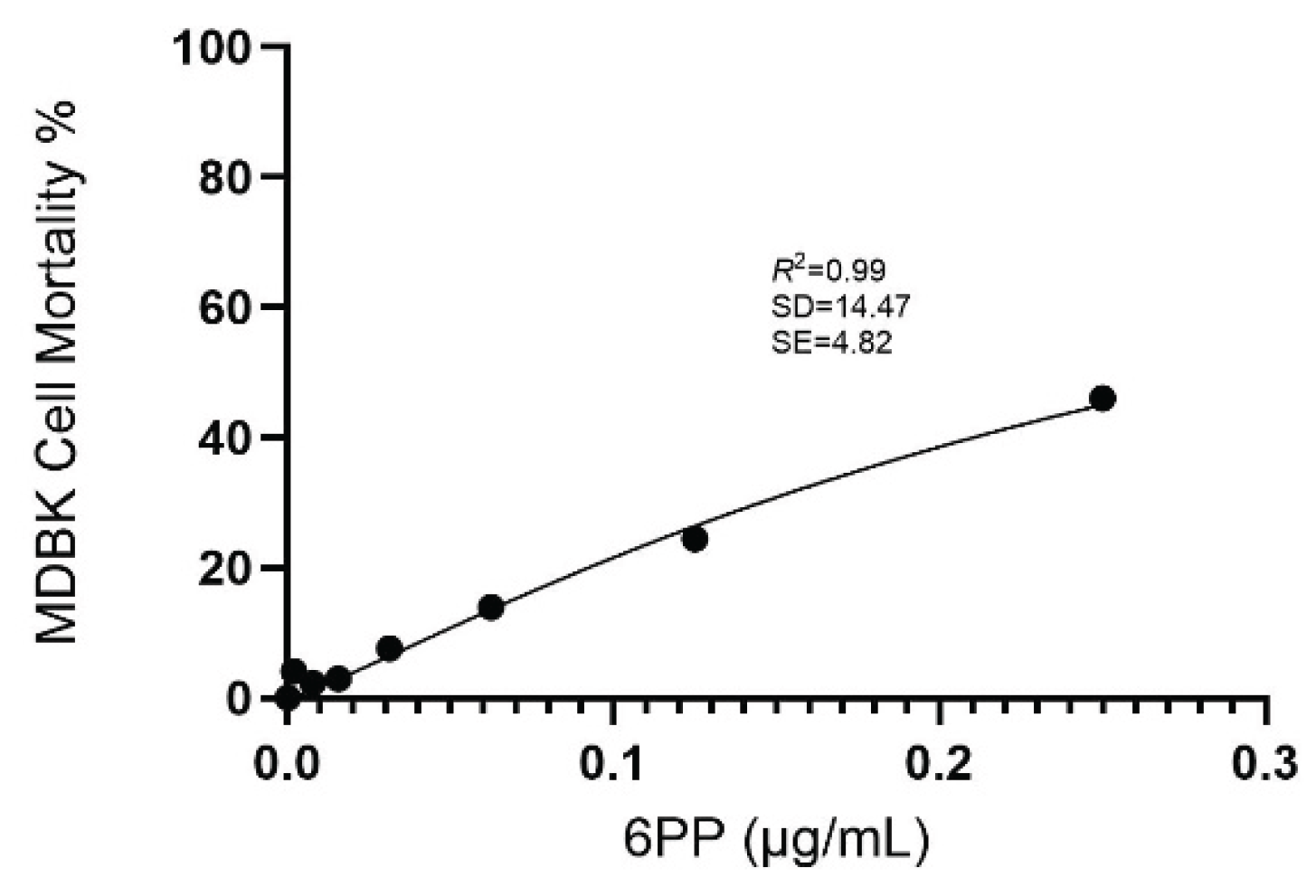

The maximum non-cytotoxic concentration was assessed and regarded as the concentration at which viability of the treated MDBK cells decreased to 20% with respect to the control cells (IC20). The experiments were performed in quadruplicates.

2.5. TBARS Assay

Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) levels were determined on the supernatant of untreated MDBK cells after 24h incubation and on the supernatant of cells treated with 6PP at different concentrations (0.25, 0.125, 0.0625μg/mL), using a modified version of the Buege and Aust method [

34]. Briefly, 100mL of culture medium was mixed with 200mL of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to eliminate any proteins present in the medium. After centrifugation, 200mL of the supernatant was added to 200mL of 0.67% tiobarbituric acid (TBA) solution and incubated at 90°C for 15 minutes. At the end of incubation, 150mL of solution were placed into a 96-well plate and absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 532nm. TBARS concentration was expressed as micromoles/L using 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxy-propane as a standard.

2.6. Virucidal Activity Assay

The potential virucidal activity of 6PP against BCoV was evaluated. The IC20 concentration was mixed with an equivalent volume of 100 TCID50/50μL of BCoV and incubated for different times (10, 30, and 60min) at 4°C, 37°C, and room temperature (RT). In parallel, for each assay, a mixture of TCID50/50μL of BCoV and DMEM (control virus) was prepared. Both the virus-compound and virus-DMEM mixtures were distributed into different wells of cell monolayers cultured in 24-well plates. Ten-fold serial dilutions were performed to assess the viral titers of each mixture. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 1h to allow virus adsorption. Then the inoculum was carefully replaced with DMEM and the plates were incubated for 72h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator.

2.7. Antiviral Activity Assays

Based on the results of the cytotoxicity assay, the antiviral activity against BCoV was evaluated using 6PP at the established IC20 dose. To assess the specific phase of viral replication compromised/inhibited by the 6PP, three distinct experimental protocols (A, B and C) were applied. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.7.1. Protocol A: Cell Protection After Viral Infection

MDBK cells were seeded in 24-well plates and after 24h the cells were infected with 100μL of BCoV containing 100TCID50/50μL. After virus adsorption for 1h at 37°C, the inoculum was removed, and cell monolayers were washed with DMEM. Two distinct experimental conditions were then performed:

1) the IC20 concentration of the 6PP was added to the cell monolayers and plates were incubated for 72h at 37°C.

2) the IC20 concentration of the 6PP was added to the cell monolayers and plates were incubated for 3h at 37°C. Following incubation, the compound was removed, the wells were washed with DMEM and then replaced with 1mL of DMEM, and the plates were further incubated for 72h at 37°C.

In untreated infected cells (control virus), DMEM was used to replace the inoculum.

Three days post-infection, aliquots of the supernatants were collected, and virus titration and RNA quantification were performed.

2.7.2. Protocol B: Cell Protection Before Viral Infection

MDBK cells were seeded in 24-well plates and after 24 h cell monolayers were incubated with the IC20 concentration of 6PP (1mL) for 3h in two distinct experimental conditions: 4°C and 37°C. After the incubation time, 6PP was removed from each well and all the monolayers were infected with 100μL of BCoV containing 100TCID50/50μL for 1h at 37°C. After virus adsorption, the inocula were replaced with DMEM.

In untreated infected cells, DMEM was employed to replace the inocula (control virus). After 72h incubation, aliquots of the supernatants were collected, and virus titration and RNA quantification were performed.

2.7.3. Protocol C: Viral Internalization Inhibition Assay

MDBK cells were seeded in 24-well plates and after 24h infected with 100μL of BCoV containing 100TCID50/50μL. Cells were then incubated for 1h at 4°C, allowing virus adsorption but not internalization. After incubation, IC20 concentration of 6PP was added to each well.

In untreated infected cells, DMEM was used to replace the inocula (control virus). After 72h, aliquots of the supernatants were collected, and virus titration and RNA quantification were performed.

2.8. Fluorescence Quantification

The image fluorescence quantification was implemented using Python version 3.9.18, (

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/index.html) with the initiation of several core libraries and their respective dependencies in the Python programming environment. These included Open-Source Computer Vision Library (OpenCV) with capabilities for image processing, Pandas for high-performance data analysis, Numerical Python (NumPy) for array operations, Matplotlib and Seaborn for interactive and statistical data visualizations, as well as Scikit-learn and SciPy for data preprocessing, and evaluation [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Briefly, experimental and control images were grayscale transformed to two-dimensional numpy arrays with the inverse binary thresholding method. Congruence was achieved between the positive and negative fluorescence images using an iterative optimization function that refined image value parameters and facilitated optimum threshold selection. Next, a HSV (Hue, Saturation and Value) color space transformation into a three-channel representation of color attributes across rows, columns, and color components enabled bounded adjustment and parametrization over the blue and green hue channels. Finally, for each identified vectorized fluorescent image, pixel intensity values were aggregated by calculating the mean across all pixels within the image. The complete code implementation and plot visualizations are provided in the Supplementary figure (HTML file and

Figure S1).

2.9. RT-qPCR for BCoV

RNA was extracted from 200μL of each supernatant using the IndiSpin® Pathogen Kit (Indical Bioscience GmbH, Leipzig, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Extracted samples were immediately stored at -80°C until tested using RT-qPCR. The reverse transcription using random hexamers and MuLV reverse transcriptase (GeneAmp® RNA PCR, Applied Biosystems, Applera Italia, Monza, Italy) was performed in a total volume of 10μL for the detection of BCoV according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Then, the RT-qPCR was carried out using primers and TaqMan probe and the same reaction conditions and reaction mix components, as previously reported [

6]. Briefly, 10μL of cDNA were added to 15μL of the reaction master mix (IQ™ Supermix, Bio-Rad Laboratories Srl, Segrate, Italy) containing 0.6μM of each primer and 0.4μM probe. After the activation of iTaq DNA polymerase at 95°C for 10min, the thermal cycling for amplification consisted of 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10s and an annealing extension at 56°C for 30s. RT-qPCR was performed in an i-Cycler iQTM Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories Srl) and the data were analyzed with the proper sequence detector software (version 3.0).

2.10. Data Analysis

The OD absorbance values obtained were converted into percentages, and the cytotoxicity results of 6PP were analyzed using non-linear curve fitting. Moreover, a dose-response curve was elaborated through non-linear regression analysis to evaluate goodness of fit (GraphPad Prism 10.3.1 program Intuitive Software for Science, San Diego, CA, USA). From the fitted dose response curve achieved, IC20 was assessed. The results were validated using Python (version 3.9.18), ensuring both accuracy and reproducibility.

Statistical analysis was performed in the Python programming environment as described previously. Analyses of virucidal activities of active metabolite were performed using repeated-measures ANOVA (rm-ANOVA), considered the most appropriate for data analysis given the repeated measures design, the correlated nature of the data, and the presence of multiple factors of time, temperature and dilution. In addition to the uncorrected P-value (P-unc), the analysis also reported the Greenhouse-Geisser correction (p-corr) to address the potential violation of sphericity assumption potentially inherent in repeated-measures designs thus enhancing robustness of the statistical inferences. Where a statistical significance was found, a pairwise post hoc comparison was performed using the Pingouin (pg) library [

39,

40]. Pingouin is a user-friendly Python library specifically designed for common statistical tests and has a pairwise function call specifically designed for multiple comparisons following a significant rm-ANOVA. The Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons which helps maintain a stringent level of significance and ensure that the observed differences are truly meaningful. The results were presented in result’s table and figures.

In contrast, the computed mean fluorescence, serving as the continuous dependent variable, was subjected to a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to comprehensively determine the significance of the various categorical factors across all experimental conditions. This analysis was conducted within the statsmodels library with its established Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) functionality for robust model estimation.

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of 6PP was determined by measurement of cell viability with the MTT colorimetric method after exposing the cells to various concentrations. Cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring the absorbance signal spectrophotometrically. Based on the adjusted dose-response curve, the IC20 value of 6PP was calculated at 0.1μg/mL (

Figure 1).

3.2. TBARS Assay

Oxidative stress was evaluated by measuring TBARS production. The results indicate that 6PP did not induce oxidative stress in MDBK cells in any of the tested concentrations, and the TBARS level resulted negative respected to the supernatant of the untreated MDBK cells (1.95μM).

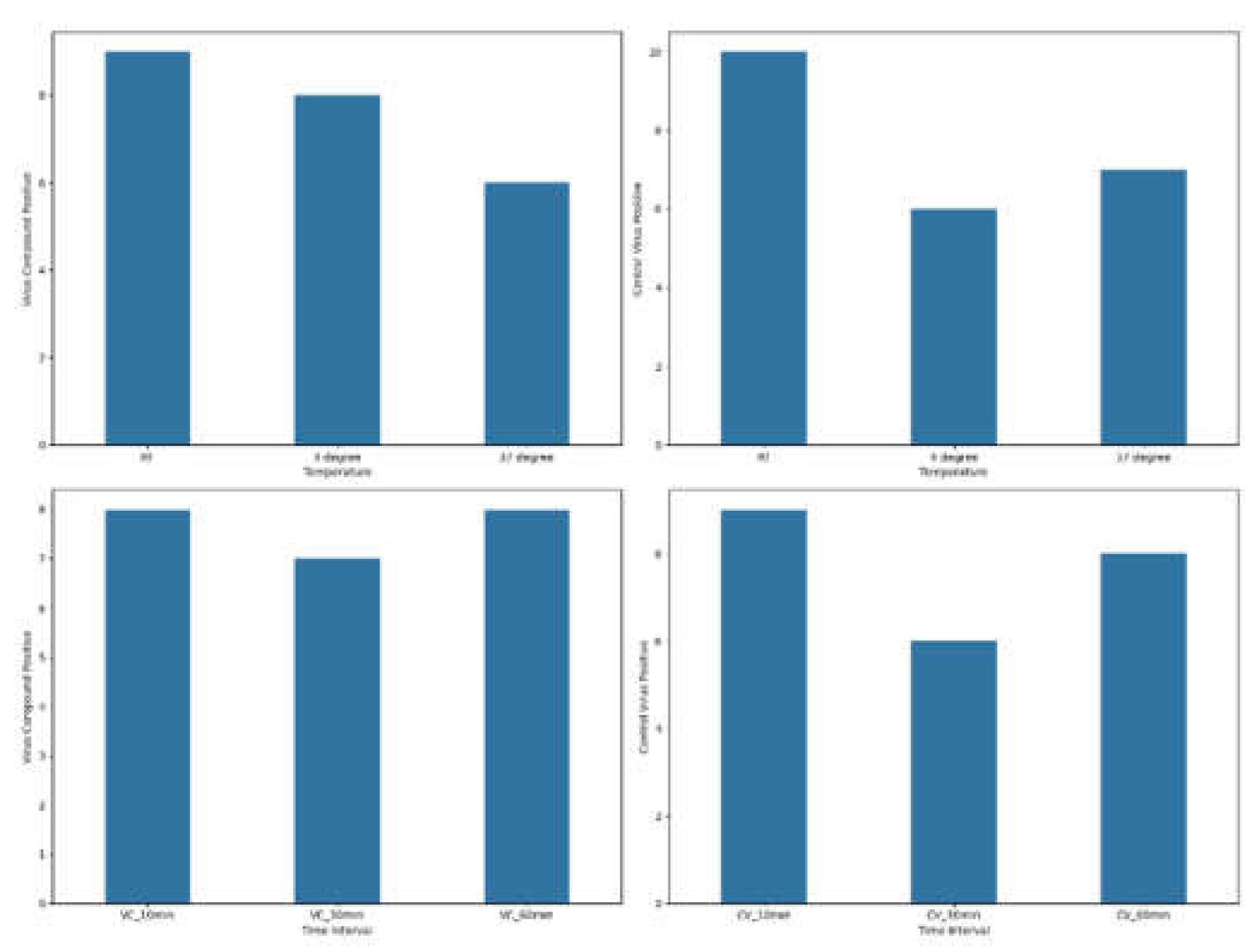

3.3. Virucidal Activity

The results of samples that yielded positive immunofluorescence (positive samples) obtained for both the virus-compound mixture group and the control virus mixture group are shown in

Figure 2, where the frequency of observed positives at various point measurements for temperature and various time intervals for virus-compound and control virus, respectively, is reported. The number of positive samples in the virus-compound mixture group were relatively consistent across temperatures with nine at room temperature (RT), eight at 4°C, and six at 37°C. Similarly, the control virus mixture group exhibited a comparable trend, with 10 positive samples at RT, followed by six at 4°C and seven at 37°C. The virus-compound mixture exhibited a peak in positive results at 10- and 60min post-treatment with eight positives each while the control virus group exhibited similar trends with nine, eight and six positive results recorded at 10, 30, and 60min respectively.

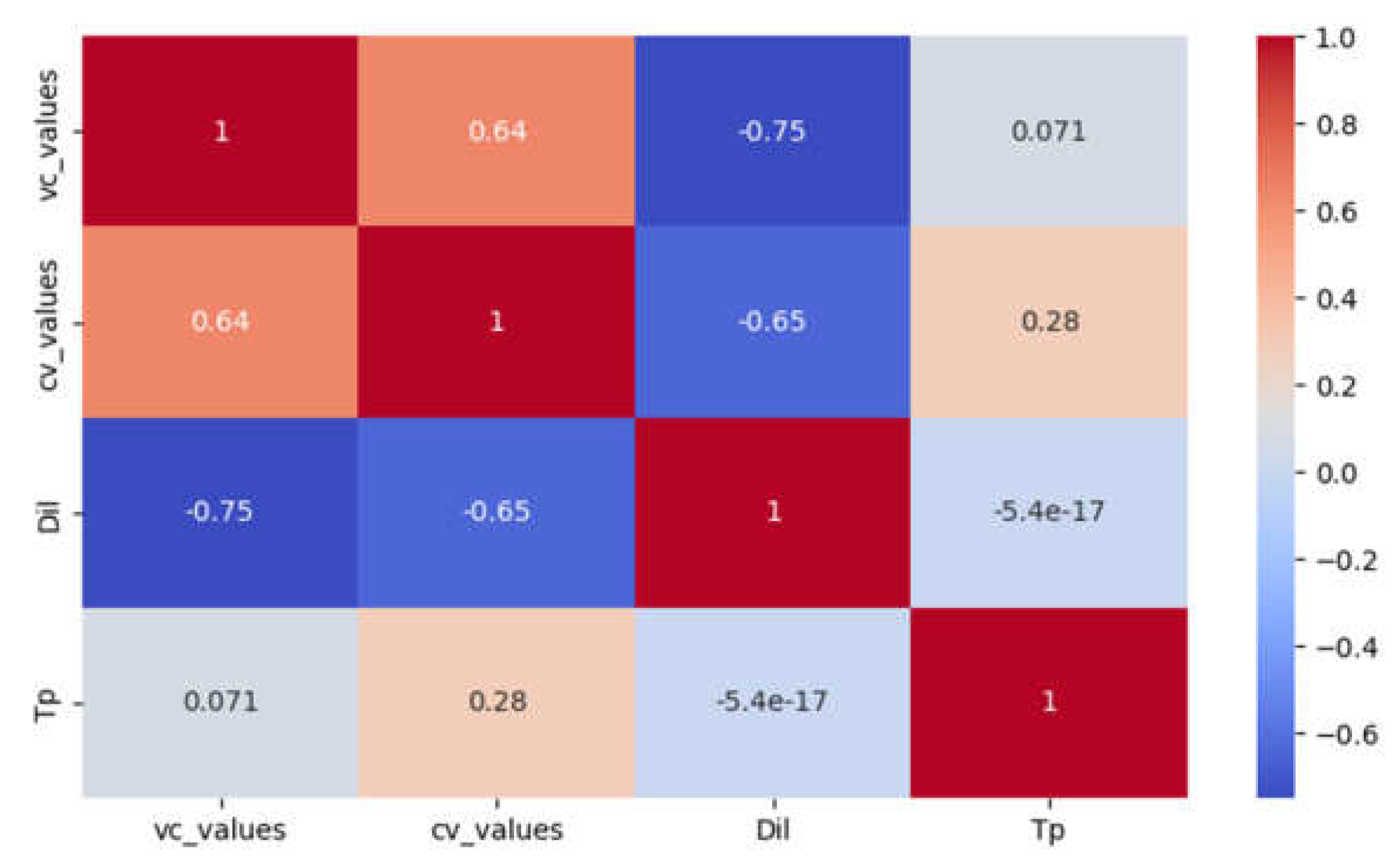

A moderately high negative correlation was found between dilution and the total number of positive samples in the immunofluorescence test for both virus-compound mixture (R = -0.75) and control virus (R = -0.65) (

Figure 3).

The rm-ANOVA analysis revealed no statistically significant differences at any of the tested time intervals between the virus-compound mixture treatment group and the control virus treatment group, across the various dilutions (P = 0. 775) and temperatures (P = 0.192). Similar observation was found for within variables of each treatment group (

Table S1).

Post-hoc analyses were used to identify the significant pairwise differences, both with and without Bonferroni multiple testing correction. Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences using the standard alpha level, but these differences were not sustained under the more conservative Bonferroni correction (

Table S2)

3.4. Antiviral Activity Assays

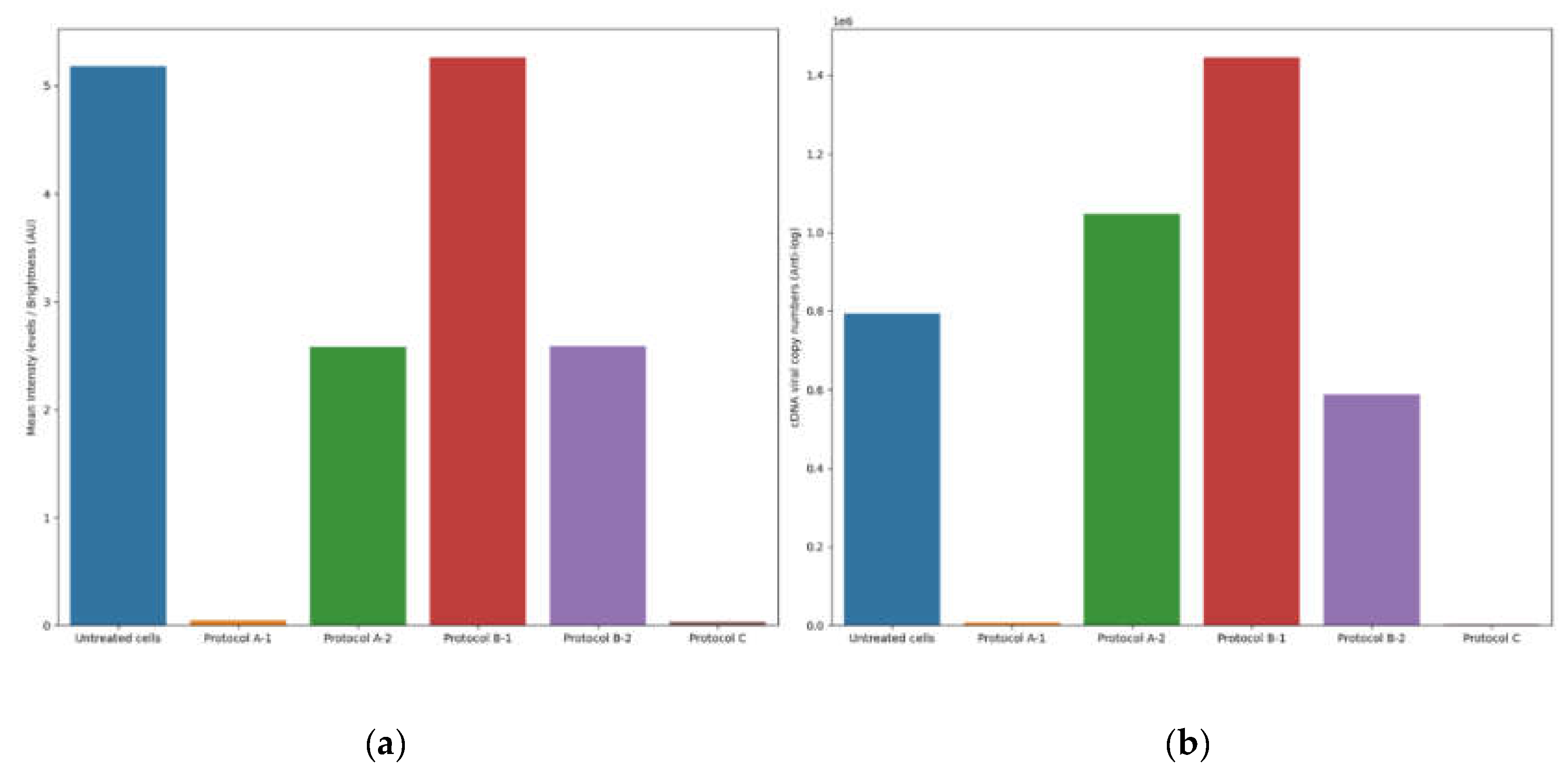

The results of the antiviral activity test were assessed by viral cDNA quantification and IF assays, conducted 72h after completing each antiviral protocol (A, B and C). The supernatants collected from the different antiviral assays were tested with a BCoV-specific RT-qPCR protocol. The cDNA viral load of untreated infected cells was used as a reference and was calculated as the mean of the values obtained from each protocol (mean = 5.9 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers).

The plates were examined using an inverted fluorescence microscope, while the images of the IF assay were acquired and subsequently analyzed using an in-house image analysis code to quantify fluorescence intensity and assess antiviral efficacy. The mean fluorescence of untreated infected cells was used as a reference and was calculated as the mean of the values obtained from the corresponding fluorescence images for each protocol (mean=5.18 brightness intensity levels).

3.4.1. Protocol A: Cell Protection After Viral Infection

1) Treatment of cell monolayer with 6PP for 72h: comparing the log10 viral cDNA copies/mL of 6PP-treated infected cells (mean=3.85 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers) with untreated infected cells (mean = 5.9 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers), a significant decrease of 2.02 log10 (P=0.0175) was detected in treated cells. Similarly, a statistically significant difference in mean fluorescence was observed between infected cells treated with 6PP for 72h (mean = 0.04 brightness intensity levels) and untreated infected cells (mean = 5.18 brightness intensity levels) (P = 0.0169).

2) Treatment of cell monolayer with 6PP for 3h: comparing the log10 viral cDNA copies/mL of 6PP-treated infected cells (mean=6.02 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers) with untreated infected cells (mean = 5.9 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers), a difference of 0.12 log10 was observed without any statistical significance (P=0.4465). Similarly, the mean fluorescence of the cell monolayer treated with 6PP for 3h (mean = 2.58 brightness intensity levels) and untreated infected cells (mean = 5.18 brightness intensity levels) was not significantly different (P = 0.127).

3.4.2. Protocol B: Cell Protection Before Viral Infection

1) Treatment with 6PP at 4oC: the log10 viral cDNA copies/mL of 6PP-treated infected cells (mean=6.16 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers) compared with the untreated infected cells (mean = 5.9 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers) revealed a 0.26 log10 difference, although without any statistical significance (P=0.0924). This is consistent with the fluoroscopy quantification method which did not reveal any statistical significance (P = 0.964) between the infected cells treated with 6PP at 4oC versus untreated infected cells, with computed mean pixels of 5.26 and 5.18 brightness intensity levels respectively.

2) Treatment with 6PP at 37oC: when comparing the log10 viral cDNA copies/mL of 6PP-treated infected cells (mean=5.77 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers) with untreated infected cells (mean = 5.9 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers), no statistically significant difference was observed (P=0.4223). Consistent with these results, the fluorescence quantification technique did not detect any significant difference (P = 0.147) in the mean fluorescence between infected cells treated with 6PP at 370C (mean = 2.59 brightness intensity levels) and untreated infected cells (mean = 5.18 brightness intensity levels).

3.4.3. Protocol C: Viral Internalization Inhibition Assay

Comparing the log10 viral cDNA copies/mL of 6PP-treated infected cells (mean=3.26 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers) to that of untreated infected cells (mean = 5.9 log10 cDNA viral copy numbers), a significant reduction of 2.64 log10 in viral load of treated cells was observed (P=0.0003). In comparison, our quantification method detected a statistically significant difference in mean fluorescence between infected cells treated with 6PP (mean = 0.032 brightness intensity levels) compared with untreated (mean = 5.18 brightness intensity levels) infected cells (P = 0.0168).

The comparison between the results obtained using the fluorescence quantification approach and the RT-qPCR is reported in

Figure 4. To precisely illustrate the magnitude of the differences of the distinct outcomes observed between the various protocols, we present the actual cDNA copy numbers directly, rather than scaled logarithmic transformations that could obscure subtle but important differences. In this study, mean intensity levels were reported as arbitrary intensity units (AU) due to the absence of pre-calibration standardization necessary to map pixel intensities to absolute radiometric values. Future investigations with the availability of camera calibration data (e.g. exposure time and quantum efficiency), would enable results to be expressed in standardized units such as photons/seconds or μW/cm².

4. Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 is a highly infectious pathogen, therefore its use in experimental research is challenging and requires specialized personnel and laboratories. Several studies have proposed BCoV as an important reference virus for HCoV research due to the common features among β-coronaviruses and their high homology in the major antigenic epitopes of the spike and the nucleocapsid protein [

3,

15]. Consequently, in order to identify new effective molecules against SARS-CoV-2 while circumventing the use of a high-risk human pathogen, the aim of the present study was to use BCoV as a surrogate model for preliminary antiviral efficacy evaluation test of the 6PP.

The present study highlights the potential antiviral activity of 6PP, a fungal bioactive compound identified as a protease inhibitor, against BCoV in vitro. Beyond this crucial finding, in order to better determine the efficacy of 6PP in cell cultures infected with BCoV, a novel methodology for fluorescence quantification that shows remarkable concordance with consolidated RT-qPCR results was introduced. These results are highly significant and represent a direct and crucial translational pathway for rapid and reliable assessment of the antiviral efficacy of natural drugs in vitro, with immediate implications for the ongoing fight against SARS-CoV-2.

Our studies involved the use of the non-cytotoxic dose of 6PP (0.1μg/mL)

in vitro on MDBK cells to evaluate its effects on different phases of BCoV infection. Several experimental conditions were employed to examine cell monolayer protection both pre- and post- infection, as well as the potential inhibition of viral internalization. A statistically significant reduction in BCoV load was observed when the cell monolayer was treated with the 6PP for 72h post infection. These results indicate that the 6PP can interfere with the BCoV replication cycle, exhibiting antiviral potential. Moreover, the treatment with the 6PP following inhibition of virus internalization also resulted in a significant decrease in viral load, implying that 6PP may limit the mechanisms of viral entry. Our results are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the antiviral efficacy of 6PP on CCoV [

25] and suggest that 6PP exhibit antiviral activity both in the early and in the late stages of BCoV infection. Furthermore, another important finding was the reduction of TBARS production, at all tested 6PP concentrations. This antioxidant effect may be due to the activation of antioxidant defenses, as reported by other authors in different cellular systems [

41,

42].

Importantly, this study introduces a novel methodology for precise fluorescence quantification, which also demonstrates remarkable concordance with results obtained via the established RT-qPCR technique. Critically, in stark contrast to the significant economic limitations inherent in conventional RT-qPCR assays, our alternative strategy offers a significantly cheaper, faster and broadly applicable solution, with greater resilience to variations in controlled environmental conditions. We posit that this adaptable method holds considerable potential for integration with other quantification approaches, as previously described [

43]. While acknowledging potential limitations related to optimal parameterization and threshold selection, as well as the known influence of the acquired image field on the quantification accuracy, we suppose that further optimization through Bayesian modelling and the adoption of appropriate image-capturing instrumentation can effectively mitigate these sources of error. Indeed, a future implementation focused on rigorous parameter refinement promises to fully unleash the potential of this versatile and cost-effective fluorescence quantification method.

Other natural compounds including flavonoids, plant extracts and essential oils have demonstrated potential antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, although their efficacy is still under evaluation [

44,

45]. Similarly, scientific research is focusing on the study of antiviral agents targeting specific viral genes and proteins in SARS-CoV-2, but such targets may not be feasible because their efficacy could be compromised by the rapid genetic mutations that CoVs undergo[

46,

47]. Future prospects to overcome this problem and to optimize the use of antivirals should combine high-throughput screening, computational modeling and structural biology, as well as the collaboration of different scientific sectors.

In conclusion, although further research is needed to better clarify the interaction between 6PP and BCoV proteins and the underlying mechanisms of its antiviral activity, our data demonstrated that prolonged 6PP treatment (72h) significantly reduces the BCoV viral load in cell monolayers. Moreover, antiviral activity was also observed when 6PP was administered following inhibition of viral internalization. The efficacy of the 6PP in two different phases of BCoV infection may imply its ability to be a broad-spectrum antiviral, supporting its possible use in future translation research to evaluate the potential application of 6PP as an antiviral agent against SARS-CoV-2.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Multi-stage Fluorescent Image Transformation Protocol all experimental and control samples at different conditions; Figure S2: Computed fluorescence obtained by vectorization and aggregation of mean pixel intensity across all images; Table S1: Result of repeated-measures ANOVA on variables within and between treatment groups for immunofluorescence-positive samples; Table S2: Posthoc pairwise comparison; Table S3: Two-way ANOVA between the mean fluorescence in the control and the different experimental conditions .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and F.F.; writing—original draft preparation, VI.V.; writing—review and editing, A.P.; methodology, VI.V., MS.L., L.DS., MM.S., A.S. and C.C.; software, EA.O.; validation, P.C.; formal analysis, EA.O.; investigation, VI.V., MS.L., E.C, F.V and A.A.; resources, A.P.; data curation, VI.V. and EA.O; visualization, A.B. and M.T.; supervision, P.C.; project administration, P.C.; funding acquisition, A.P. and F.F.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union-Next Generation EU, Project PRIN Prot. 2022WTWB9R "Antiviral activity of drugs and natural compounds evaluated in vitro and in vivo against bovine coronavirus: a translational study to SARS-CoV-2"

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saif LJ, Jung K. Comparative Pathogenesis of Bovine and Porcine Respiratory Coronaviruses in the Animal Host Species and SARS-CoV-2 in Humans. McAdam AJ, editor. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 Jul 23;58(8):e01355-20. [CrossRef]

- Faustino R, Faria M, Teixeira M, Palavra F, Sargento P, Do Céu Costa M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of coronavirus: One health approach for a global strategy. One Health. 2022 Jun;14:100383. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Q, Li B, Sun D. Advances in Bovine Coronavirus Epidemiology. Viruses. 2022 May 21;14(5):1109.

- Hodnik JJ, Ježek J, Starič J. Coronaviruses in cattle. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2020 Nov;52(6):2809–16. [CrossRef]

- Padalino B, Cirone F, Zappaterra M, Tullio D, Ficco G, Giustino A, et al. Factors Affecting the Development of Bovine Respiratory Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in Beef Steers Shipped From France to Italy. Front Vet Sci. 2021 Jun 28;8:627894.

- Pratelli A, Lucente MS, Cordisco M, Ciccarelli S, Di Fonte R, Sposato A, et al. Natural Bovine Coronavirus Infection in a Calf Persistently Infected with Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus: Viral Shedding, Immunological Features and S Gene Variations. Animals. 2021 Nov 23;11(12):3350. [CrossRef]

- Vlasova AN, Saif LJ. Bovine Coronavirus and the Associated Diseases. Front Vet Sci. 2021 Mar 31;8:643220.

- Boileau MJ, Kapil S. Bovine Coronavirus Associated Syndromes. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2010 Mar;26(1):123–46. [CrossRef]

- Clark MA. Bovine coronavirus. Br Vet J. 1993 Jan;149(1):51–70.

- Saif LJ. Bovine Respiratory Coronavirus. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2010 Jul;26(2):349–64.

- Reynolds DJ, Debney TG, Hall GA, Thomas LH, Parsons KR. Studies on the relationship between coronaviruses from the intestinal and respiratory tracts of calves. Arch Virol. 1985 Mar;85(1–2):71–83. [CrossRef]

- Domingo E, Martínez-Salas E, Sobrino F, De La Torre JC, Portela A, Ortín J, et al. The quasispecies (extremely heterogeneous) nature of viral RNA genome populations: biological relevance — a review. Gene. 1985 Jan;40(1):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Tilocca B, Soggiu A, Musella V, Britti D, Sanguinetti M, Urbani A, et al. Molecular basis of COVID-19 relationships in different species: a one health perspective. Microbes Infect. 2020 May;22(4–5):218–20. [CrossRef]

- Tilocca B, Soggiu A, Sanguinetti M, Musella V, Britti D, Bonizzi L, et al. Comparative computational analysis of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein epitopes in taxonomically related coronaviruses. Microbes Infect. 2020 May;22(4–5):188–94.

- Domańska-Blicharz K, Woźniakowski G, Konopka B, Niemczuk K, Welz M, Rola J, et al. Animal coronaviruses in the light of COVID-19. J Vet Res. 2020 Aug 2;64(3):333–45. [CrossRef]

- Van De Sand L, Bormann M, Schmitz Y, Heilingloh CS, Witzke O, Krawczyk A. Antiviral Active Compounds Derived from Natural Sources against Herpes Simplex Viruses. Viruses. 2021 Jul 16;13(7):1386.

- Tian WJ, Wang XJ. Broad-Spectrum Antivirals Derived from Natural Products. Viruses. 2023 Apr 30;15(5):1100. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal V, Bala E, Kumar P, Raizada P, Singh P, Verma PK. Natural Products as Potential Therapeutic Agents for SARS-CoV-2: AMedicinal Chemistry Perspective. Curr Top Med Chem. 2023 Aug 7;23(17):1664–98.

- Roy BG. Potential of small-molecule fungal metabolites in antiviral chemotherapy. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2017 Aug;25(2):20–52.

- Salvatore MM, DellaGreca M, Andolfi A, Nicoletti R. New Insights into Chemical and Biological Properties of Funicone-like Compounds. Toxins. 2022 Jul 8;14(7):466. [CrossRef]

- Raihan T, Rabbee MF, Roy P, Choudhury S, Baek KH, Azad AK. Microbial Metabolites: The Emerging Hotspot of Antiviral Compounds as Potential Candidates to Avert Viral Pandemic Alike COVID-19. Front Mol Biosci. 2021 Sep 7;8:732256. [CrossRef]

- Conrado R, Gomes TC, Roque GSC, De Souza AO. Overview of Bioactive Fungal Secondary Metabolites: Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Compounds. Antibiotics. 2022 Nov 11;11(11):1604.

- Deshmukh SK, Agrawal S, Gupta MK, Patidar RK, Ranjan N. Recent Advances in the Discovery of Antiviral Metabolites from Fungi. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2022 Mar;23(4):495–537. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi JA, Barbosa BVR, Lima MTNS, Cardoso PG, Contigli C, Pimenta LPS. Antiviral fungal metabolites and some insights into their contribution to the current COVID-19 pandemic. Bioorg Med Chem. 2021 Sep;46:116366. [CrossRef]

- Cerracchio C, Del Sorbo L, Serra F, Staropoli A, Amoroso MG, Vinale F, et al. Fungal metabolite 6-pentyl-α-pyrone reduces canine coronavirus infection. Heliyon. 2024 Mar;10(6):e28351. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima S, Watashi K, Kamisuki S, Tsukuda S, Takemoto K, Matsuda M, et al. Specific inhibition of hepatitis C virus entry into host hepatocytes by fungi-derived sulochrin and its derivatives. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013 Nov;440(4):515–20. [CrossRef]

- Nzimande B, Makhwitine JP, Mkhwanazi NP, Ndlovu SI. Developments in Exploring Fungal Secondary Metabolites as Antiviral Compounds and Advances in HIV-1 Inhibitor Screening Assays. Viruses. 2023 Apr 23;15(5):1039.

- Guo YW, Liu XJ, Yuan J, Li HJ, Mahmud T, Hong MJ, et al. l-Tryptophan Induces a Marine-Derived Fusarium sp. to Produce Indole Alkaloids with Activity against the Zika Virus. J Nat Prod. 2020 Nov 25;83(11):3372–80.

- Thaisrivongs S, Romero DL, Tommasi RA, Janakiraman MN, Strohbach JW, Turner SR, et al. Structure-Based Design of HIV Protease Inhibitors: 5,6-Dihydro-4-hydroxy-2-pyrones as Effective, Nonpeptidic Inhibitors. J Med Chem. 1996 Jan 1;39(23):4630–42. [CrossRef]

- Suwannarach N, Kumla J, Sujarit K, Pattananandecha T, Saenjum C, Lumyong S. Natural Bioactive Compounds from Fungi as Potential Candidates for Protease Inhibitors and Immunomodulators to Apply for Coronaviruses. Molecules. 2020 Apr 14;25(8):1800.

- Vinale F, Sivasithamparam K, Ghisalberti EL, Marra R, Barbetti MJ, Li H, et al. A novel role for Trichoderma secondary metabolites in the interactions with plants. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2008 Jan;72(1–3):80–6. [CrossRef]

- Staropoli A, Iacomino G, De Cicco P, Woo SL, Di Costanzo L, Vinale F. Induced secondary metabolites of the beneficial fungus Trichoderma harzianum M10 through OSMAC approach. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2023 Mar 28;10(1):28.

- Fiorito F, Marfè G, De Blasio E, Granato GE, Tafani M, De Martino L, et al. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin regulates Bovine Herpesvirus type 1 induced apoptosis by modulating Bcl-2 family members. Apoptosis. 2008 Oct;13(10):1243–52. [CrossRef]

- Buege JA, Aust SD. [30] Microsomal lipid peroxidation. In: Methods in Enzymology [Internet]. Elsevier; 1978 [cited 2025 May 15]. p. 302–10. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0076687978520326.

- Harris CR, Millman KJ, Van Der Walt SJ, Gommers R, Virtanen P, Cournapeau D, et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature. 2020 Sep 17;585(7825):357–62.

- Jones E, Oliphant T, Peterson P. SciPy: Open Source Scientific Tools for Python. 2001 Jan;

- Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res. 2012 Jan;12.

- van Rossum G. Python reference manual. CWI; 1995.

- Seabold S, Perktold J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. In Austin, Texas; 2010 [cited 2025 Apr 28]. p. 92–6. Available from: https://doi.curvenote.com/10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-011.

- Vallat R. Pingouin: statistics in Python. J Open Source Softw. 2018 Nov 19;3(31):1026. [CrossRef]

- Hao J, Wuyun D, Xi X, Dong B, Wang D, Quan W, et al. Application of 6-Pentyl-α-Pyrone in the Nutrient Solution Used in Tomato Soilless Cultivation to Inhibit Fusarium oxysporum HF-26 Growth and Development. Agronomy. 2023 Apr 25;13(5):1210. [CrossRef]

- Lim JS, Hong JH, Lee DY, Li X, Lee DE, Choi JU, et al. 6-Pentyl-α-Pyrone from Trichoderma gamsii Exert Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Mouse Macrophages. Antioxidants. 2023 Nov 22;12(12):2028. [CrossRef]

- Minesso S, Odigie AE, Franceschi V, Cotti C, Cavirani S, Tempesta M, et al. A Simple and Versatile Method for Ex Vivo Monitoring of Goat Vaginal Mucosa Transduction by Viral Vector Vaccines. Vaccines. 2024 Jul 29;12(8):851.

- De Jesús-González LA, León-Juárez M, Lira-Hernández FI, Rivas-Santiago B, Velázquez-Cervantes MA, Méndez-Delgado IM, et al. Advances and Challenges in Antiviral Development for Respiratory Viruses. Pathogens. 2024 Dec 31;14(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Wen CC, Kuo YH, Jan JT, Liang PH, Wang SY, Liu HG, et al. Specific Plant Terpenoids and Lignoids Possess Potent Antiviral Activities against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J Med Chem. 2007 Aug 1;50(17):4087–95.

- Wani AR, Yadav K, Khursheed A, Rather MA. An updated and comprehensive review of the antiviral potential of essential oils and their chemical constituents with special focus on their mechanism of action against various influenza and coronaviruses. Microb Pathog. 2021 Mar;152:104620. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Wu J, Nie J, Zhang L, Hao H, Liu S, et al. The Impact of Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike on Viral Infectivity and Antigenicity. Cell. 2020 Sep;182(5):1284-1294.e9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).