Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

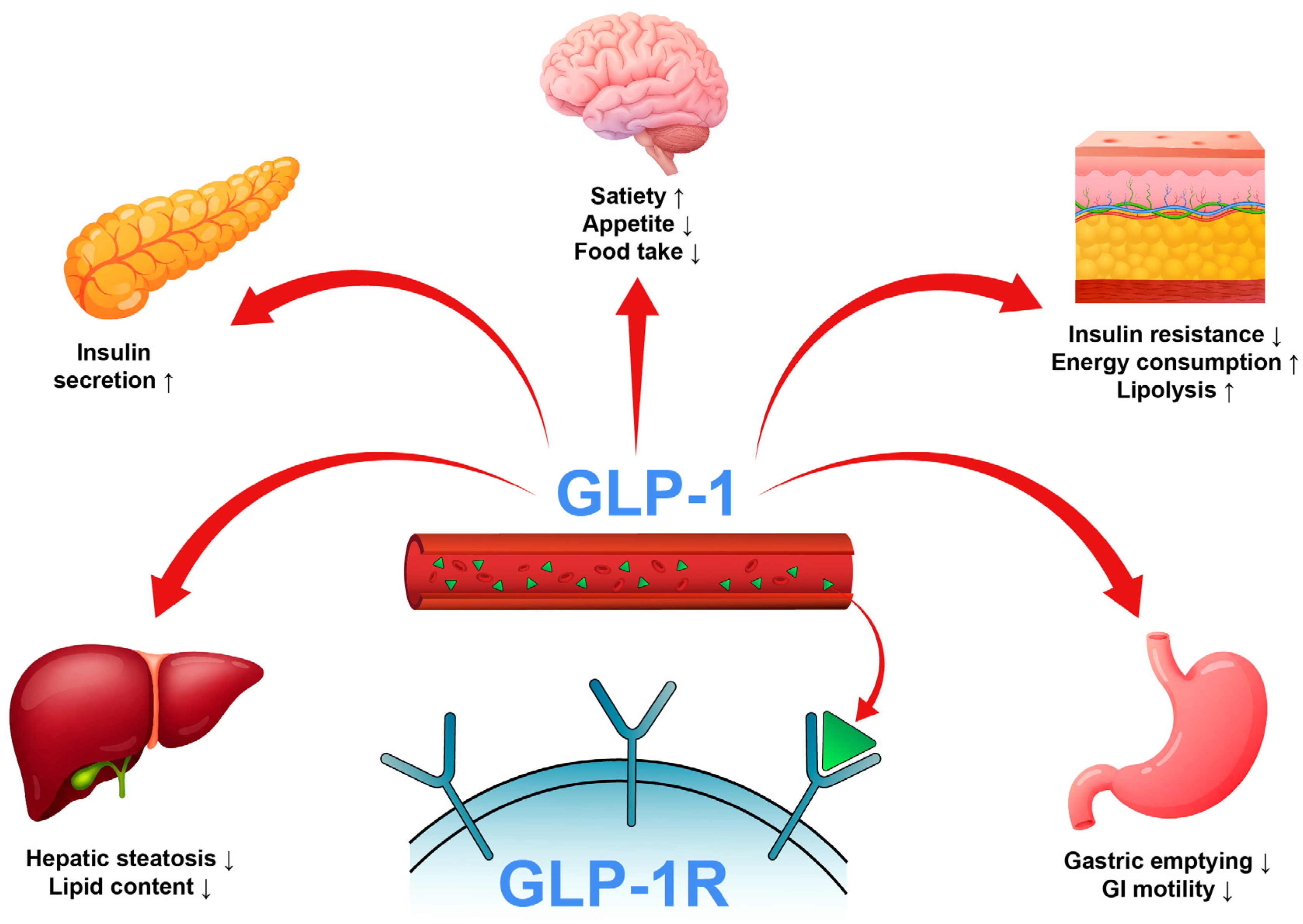

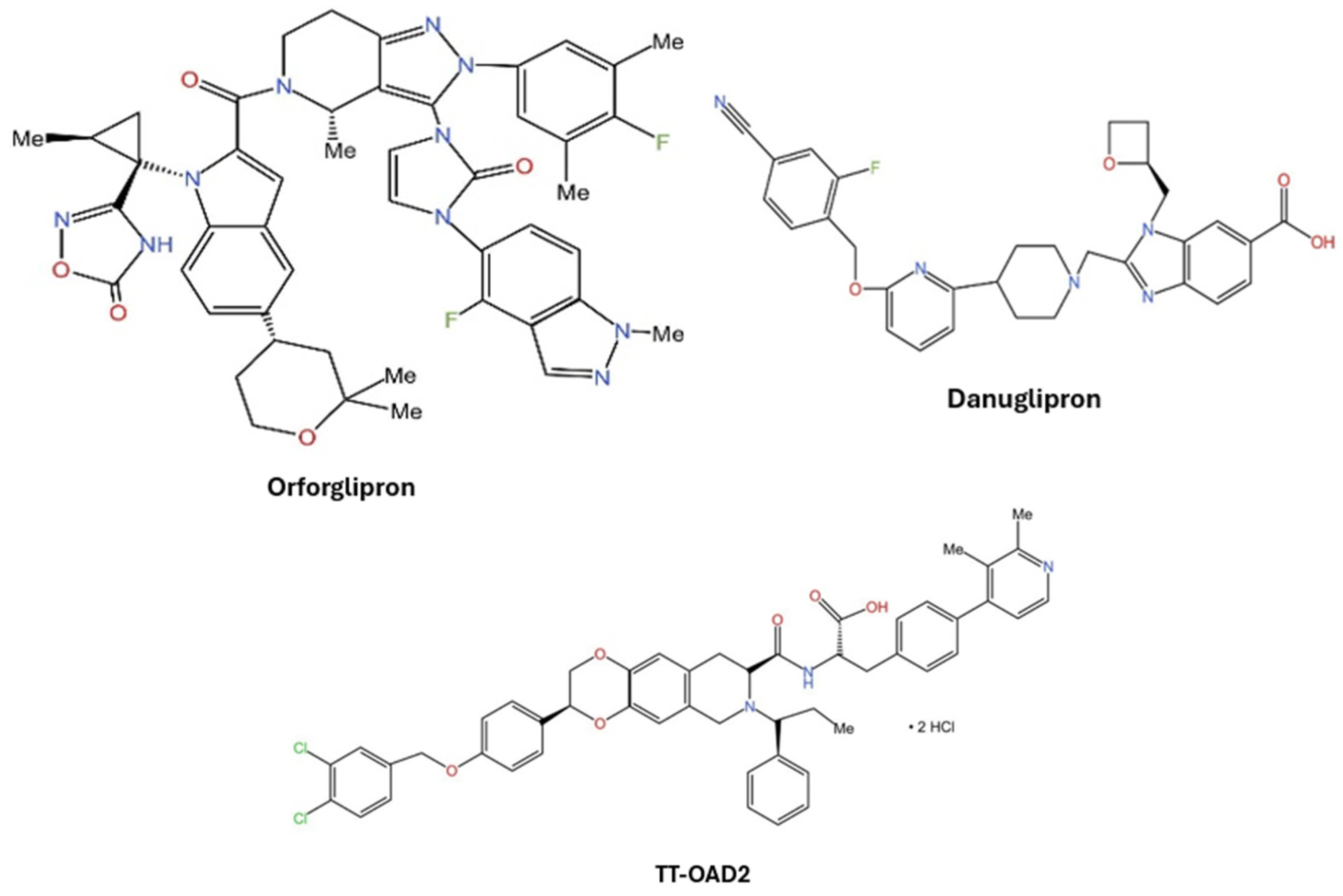

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

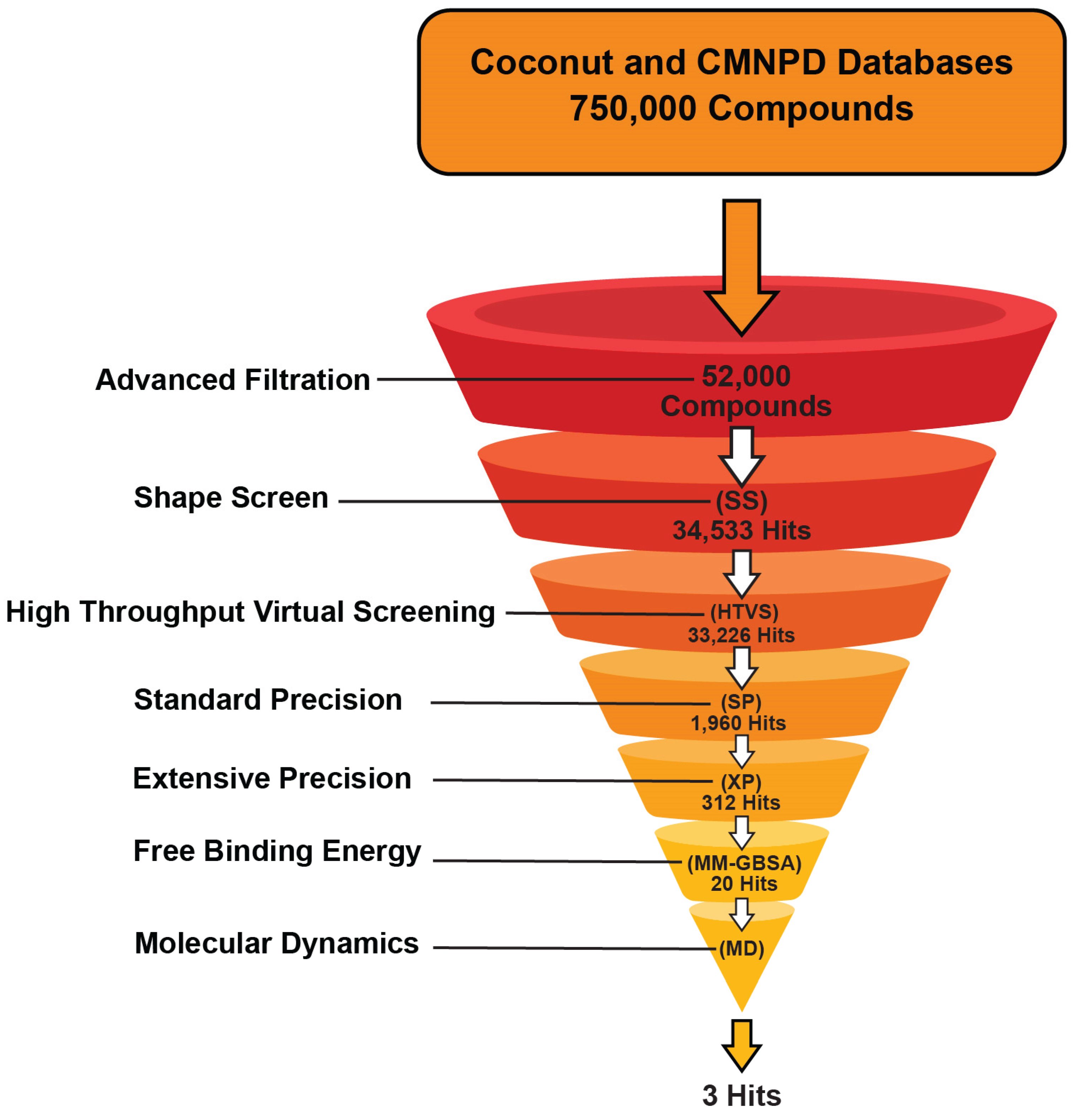

2.1. Database Preparation for Virtual Screening

2.1.1. Physicochemical Parameters and Drug-Likeness

2.1.2. Shape Screening

2.2. Virtual Screening

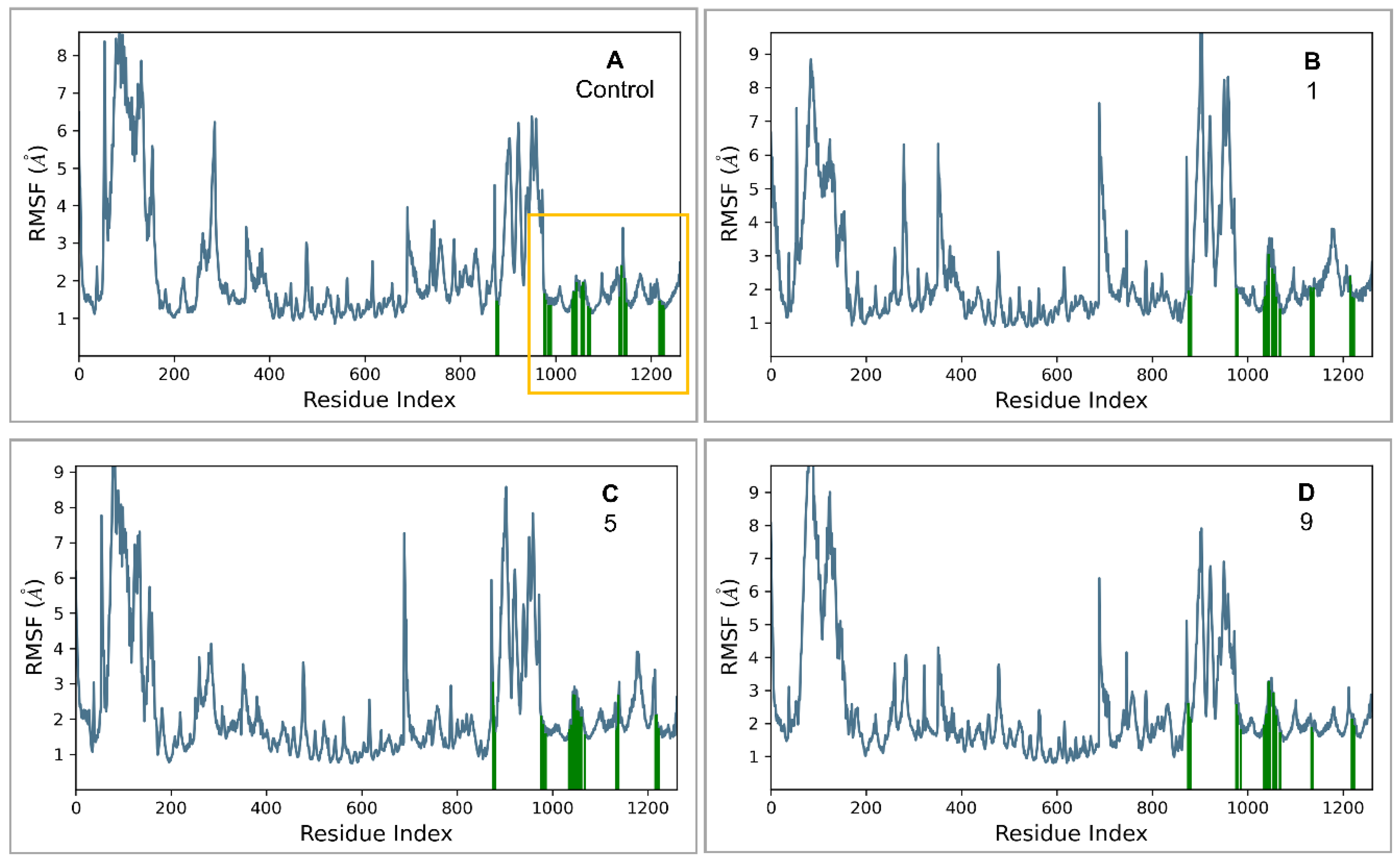

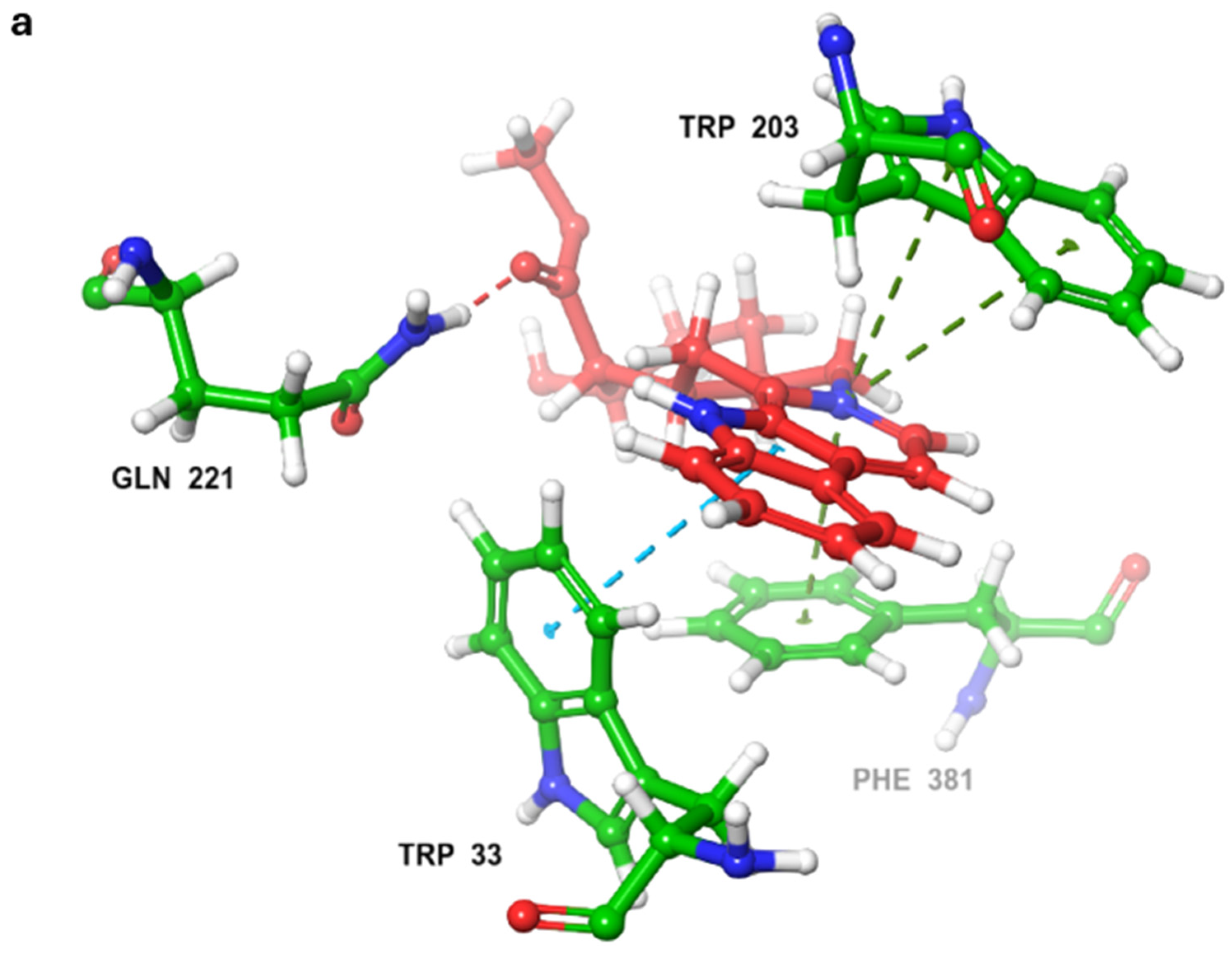

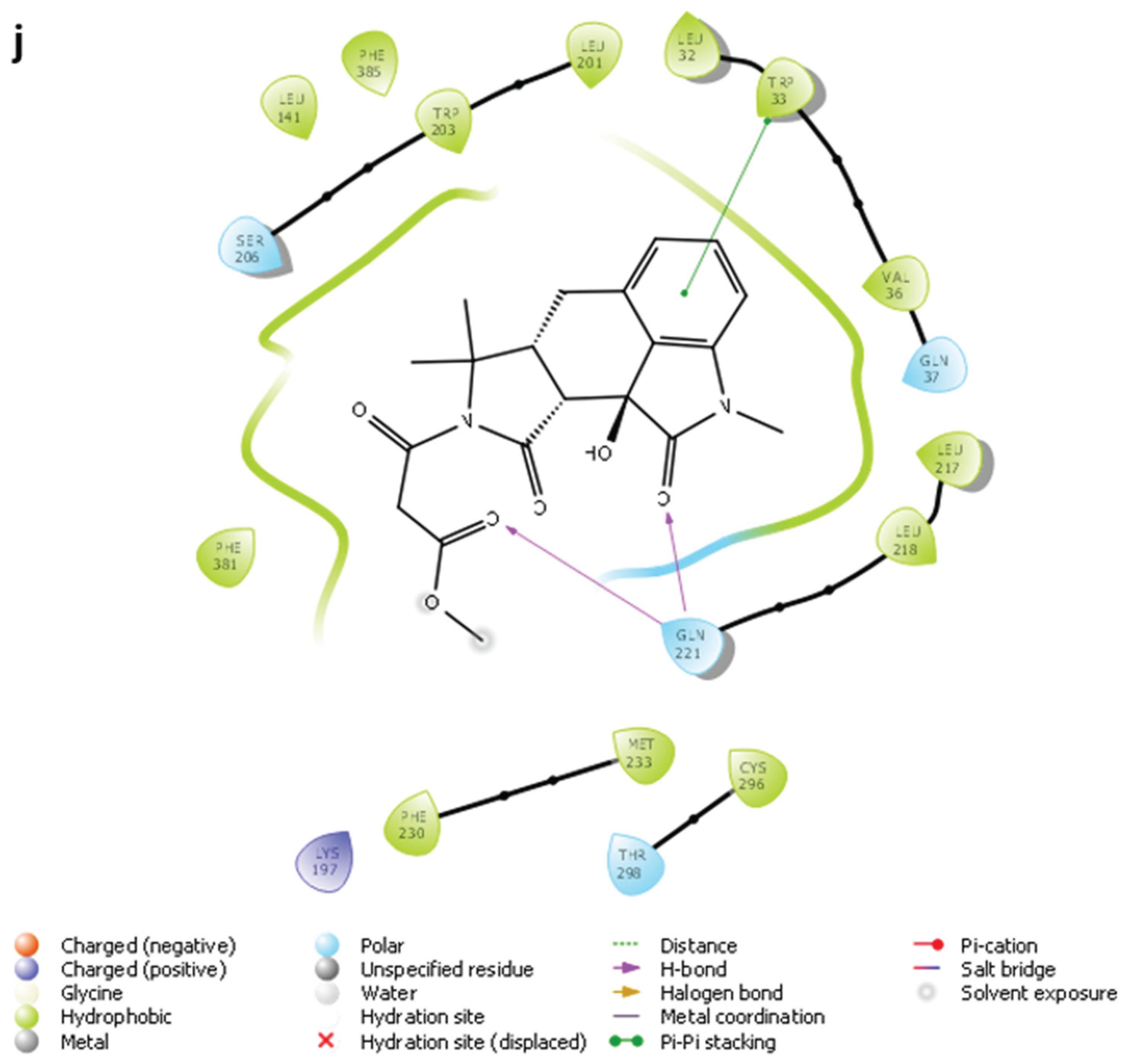

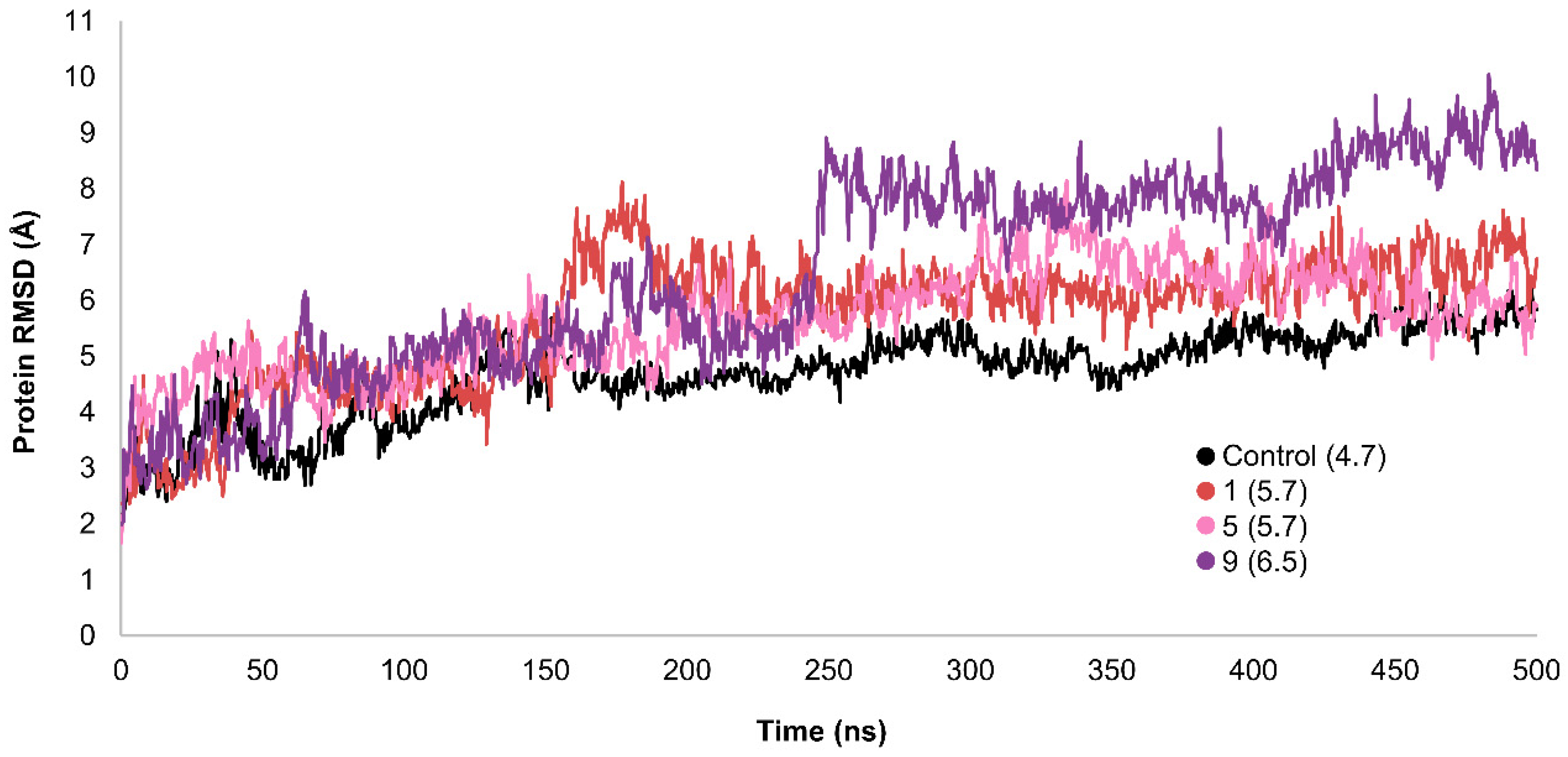

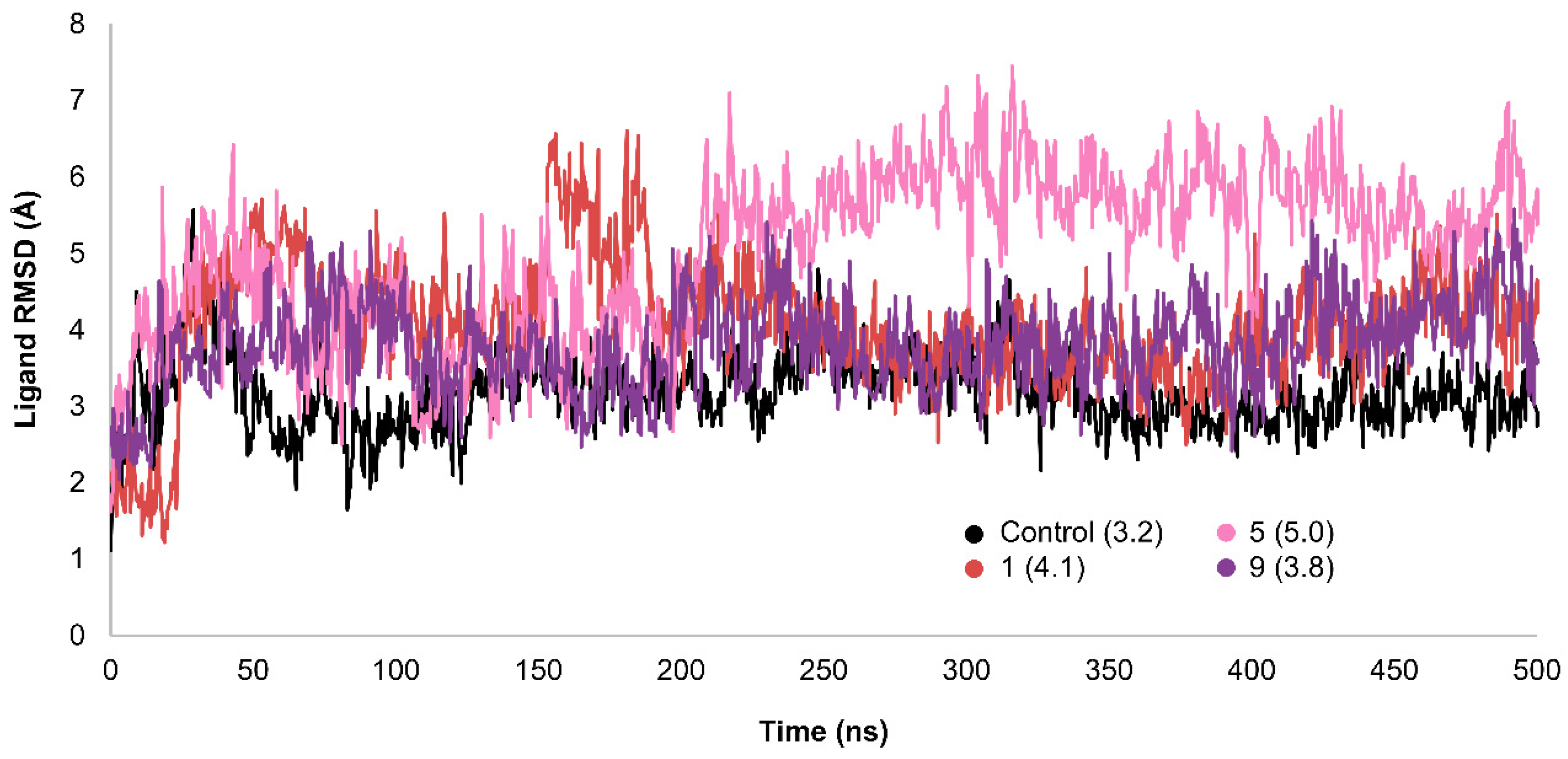

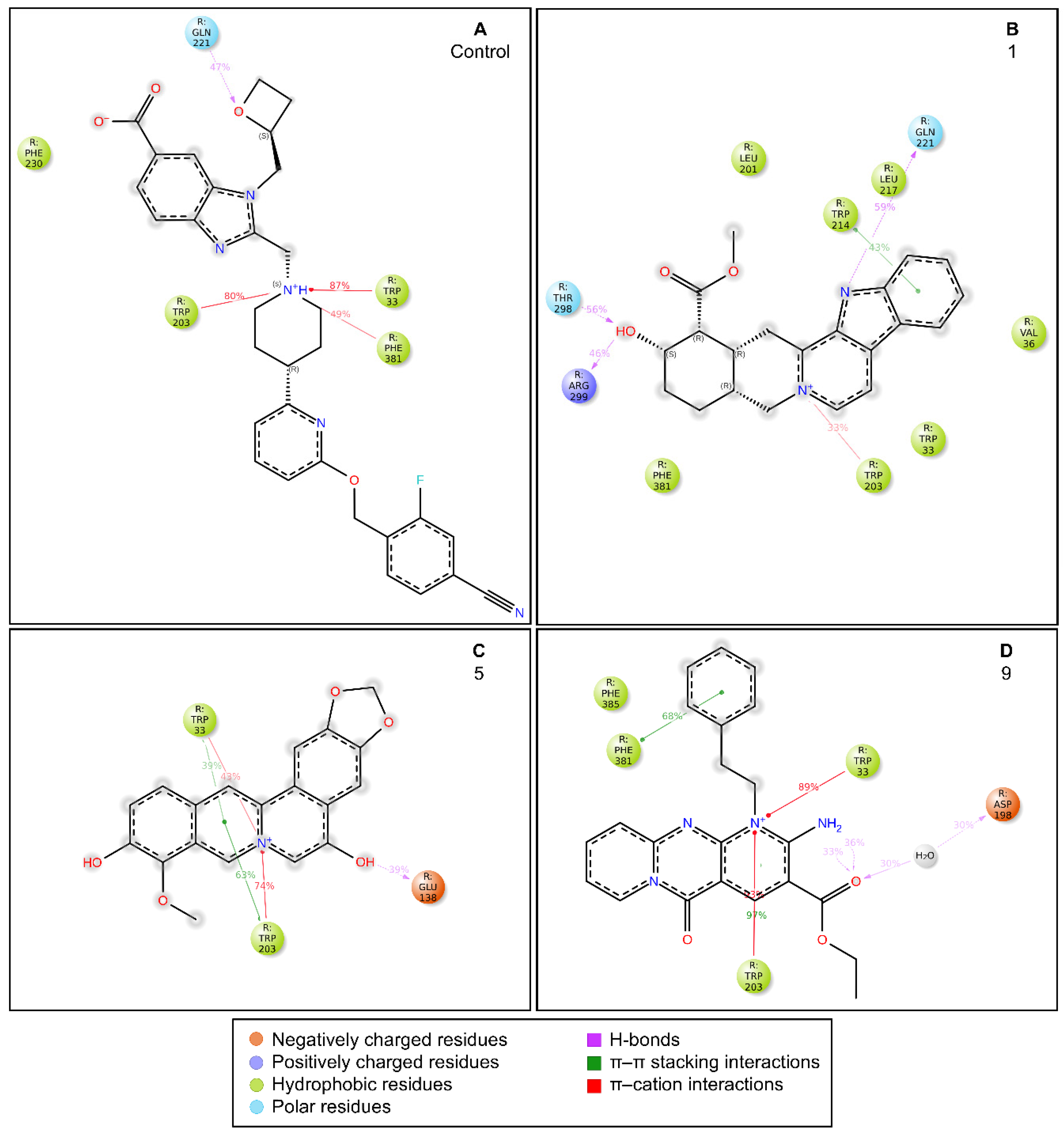

2.3. MD Simulations and Binding Free Energy Calculations for MD Frames

- Control-GLP-1R complex

- Compound 1-GLP-1R complex

- Compound 5-GLP-1R complex

- Compound 9-GLP-1R complex

2.8. ADMET and drug-likeness

| ADMET Parameters | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | |||||||||||

| Water solubility (log mol/L) | -3.506 | -3.489 | -2.791 | -2.998 | -3.011 | -.851 | -3.745 | -3.583 | -3.32 | -3.005 | -2.96 |

| Caco2 permeability (log Papp in 10-6 cm/s) | 1.135 | 1.198 | -0.546 | 0.151 | 0.994 | 1.23 | -0.003 | 0.829 | 1.158 | -0.305 | 0.986 |

| Intestinal absorption (human) (% Absorbed) | 97.322 | 96.618 | 3.62 | 48 | 95 | 100 | 54 | 96 | 100 | 48 | 63.055 |

| P-glycoprotein substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Distribution | |||||||||||

| BBB permeability (log BB) | -0.043 | 0.228 | -1.479 | -1.378 | -0.133 | -0.398 | -1.031 | 0.058 | -0.485 | -1.047 | -1.635 |

| CNS permeability (log PS) | -2.209 | -2.002 | -3.698 | -2.508 | -2.361 | -3.778 | -3.464 | -1.894 | -2.565 | -2.895 | -3.746 |

| Metabolism | |||||||||||

| CYP2D6 substrate (Yes/No) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| CYP3A4 substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitior (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitior (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitior (Yes/No) | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitior (Yes/No) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitior (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Excretion | |||||||||||

| Total Clearance (log ml/min/kg) | 1.003 | 1.189 | 1.021 | 0.497 | 1.11 | 0.763 | 0.099 | 1.1 | 0.928 | 0.844 | 0.664 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Toxicity | |||||||||||

| AMES toxicity (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Max. tolerated dose (human) (log mg/kg/day) | -0.349 | -0.779 | 0.31 | 0.742 | -0.154 | 0.528 | 0.595 | 0.122 | -0.647 | 0.62 | 0.664 |

| hERG I inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hepatotoxicity (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Molecule properties | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Control |

| Physicochemical properties | |||||||||||

| Molecular Weight | 351.42 | 349.40 | 397.38 | 404.42 | 336.32 | 417.41 | 354.31 | 344.36 | 389.43 | 333.34 | 543.59 |

| LogP | 1.98 | 2.08 | 0.68 | 2.04 | 2.11 | 3.22 | 1.63 | 2.65 | 2.07 | 1.69 | 1.96 |

| #Acceptors | 3 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| #Donors | 2 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| #Heavy atoms | 26 | 26 | 29 | 30 | 25 | 31 | 26 | 26 | 29 | 24 | 40 |

| #Arom. heavy atoms | 13 | 13 | 9 | 20 | 18 | 22 | 12 | 19 | 20 | 10 | 21 |

| Fraction Csp3 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| #Rotatable bonds | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 10 |

| Molar refractivity | 101.04 | 100.49 | 108.21 | 111.41 | 93.35 | 114.92 | 88.51 | 99.10 | 112.34 | 88.21 | 149.31 |

| TPSA (Ų) | 66.20 | 55.20 | 152.08 | 115.56 | 72.25 | 109.86 | 121.13 | 69.03 | 90.57 | 116.84 | 117.53 |

| Drug-likeness | |||||||||||

| Lipinski alert | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | Yes | yes |

| Ghose | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | Yes | no |

| Veber | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | Yes | Yes |

| Egan | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | Yes | Yes |

| Muegge | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.55 |

| Medicinal chemistry | |||||||||||

| PAINS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brenk | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Synthetic accessibility | 3.99 | 4.36 | 4.61 | 3.70 | 2.68 | 4.06 | 3.88 | 3.00 | 2.94 | 3.18 | 4.75 |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Software

3.2. Database Preparation

3.3. Shape Screening

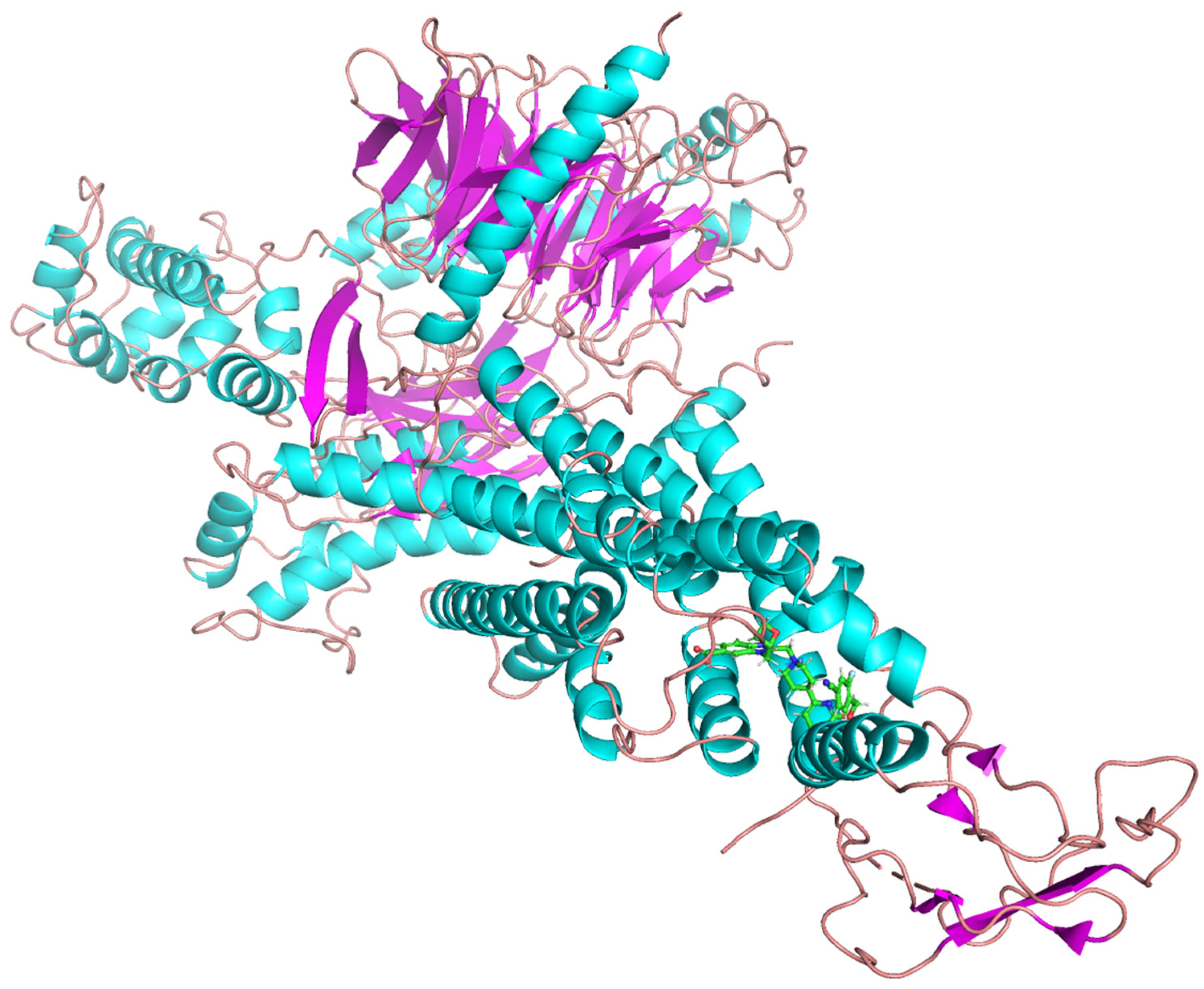

3.4. Crystal Structures

3.5. Protein Preparation

3.6. Ligand Library Preparation

3.7. Validation of Molecular Docking

3.8. Virtual Screening Workflow

3.9. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

3.10. Binding Free Energy Calculations for MD Frames

3.11. ADMET Profiling

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; Pavkov, M.E.; Ramachandaran, A.; Wild, S.H.; James, S.; Herman, W.H.; Zhang, P.; Bommer, C.; Kuo, S.; Boyko, E.J.; Magliano, D.J. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathers, C.D.; Loncar, D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006, 3, e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzani, R.; Landolfo, M.; Di Pentima, C.; Ortensi, B.; Falcioni, P.; Sabbatini, L.; Massacesi, A.; Rampino, I.; Spannella, F.; Giulietti, F. Adipocentric origin of the common cardiometabolic complications of obesity in the young up to the very old: pathophysiology and new therapeutic opportunities. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1365183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.K.; Hackett, T.A.; Galli, A.; Flynn, C.R. GLP-1: Molecular mechanisms and outcomes of a complex signaling system. Neurochem Int 2019, 128, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiola, J.O.; Oluyemi, A.A.; Idowu, O.T.; Oyinloye, O.M.; Ubah, C.S.; Owolabi, O.V.; Somade, O.T.; Onikanni, S.A.; Ajiboye, B.O.; Osunsanmi, F.O.; et al. Potential Role of Phytochemicals as Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor (GLP-1R) Agonists in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, J.; Kleinman, W.A.; Singh, L.; Singh, G.; Raufman, J.P. Isolation and characterization of exendin-4, an exendin-3 analogue, from Heloderma suspectum venom. Further evidence for an exendin receptor on dispersed acini from guinea pig pancreas. J Biol Chem 1992, 267, 7402–7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Bloch, P.; Schäffer, L.; Pettersson, I.; Spetzler, J.; Kofoed, J.; Madsen, K.; Knudsen, L.B.; McGuire, J.; Steensgaard, D.B.; Strauss, H.M.; Gram, D.X.; Knudsen, S.M.; Nielsen, F.S.; Thygesen, P.; Reedtz-Runge, S.; Kruse, T. Discovery of the Once-Weekly Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Analogue Semaglutide. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 7370–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Solem, E.; Rasmussen, M.H.; Christensen, M.; Knop, F.K. Dulaglutide, a long-acting GLP-1 analog fused with an Fc antibody fragment for the potential treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2010, 12, 790–797 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, L.B.; Agerso, H.; Bjenning, C.; Bregenholt, S.; Carr, R.D.; Godtfredsen, C.; Holst, J.J.; Huusfeldt, P.O.; Larsen, M.O.; Larsen, P.J. GLP-1 derivatives as novel compounds for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: selection of NN2211 for clinical development. Drugs of the Future 2001, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yang, S.; Deng, W.; Li, J.; Chen, J. Efficacy and Safety of Liraglutide and Semaglutide on Weight Loss in People with Obesity or Overweight: A Systematic Review. Clin Epidemiol 2022, 14, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi-Sunyer, X.; Astrup, A.; Fujioka, K.; Greenway, F.; Halpern, A.; Krempf, M.; Lau, D.C.; le Roux, C.W.; Violante Ortiz, R.; Jensen, C.B.; Wilding, J.P. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in Weight Management. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogineni, P.; Melson, E.; Papamargaritis, D.; Davies, M. Oral glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and combinations of entero-pancreatic hormones as treatments for adults with type 2 diabetes: where are we now? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2024, 25, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. Advances in oral peptide therapeutics. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2020, 19, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, B.; Feng, D.; Hu, H.; Chu, M.; Qu, Q.; Tarrasch, J.T.; Li, S.; Sun Kobilka, T.; Kobilka, B.K.; Skiniotis, G. Cryo-EM structure of the activated GLP-1 receptor in complex with a G protein. Nature 2017, 546, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Sun, B.; Yoshino, H.; Feng, D.; Suzuki, Y.; Fukazawa, M.; Nagao, S.; Wainscott, D.B.; Showalter, A.D.; Droz, B.A.; Kobilka, T.S.; Coghlan, M.P.; Willard, F.S.; Kawabe, Y.; Kobilka, B.K.; Sloop, K.W. Structural basis for GLP-1 receptor activation by LY3502970, an orally active nonpeptide agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 29959–29967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A.; Edmonds, D.J.; Fortin, J.-P.; Kalgutkar, A.S.; Kuzmiski, J.B.; Loria, P.M.; Saxena, A.R.; Bagley, S.W.; Buckeridge, C.; Curto, J.M.; Derksen, D.R.; Dias, J.M.; Griffor, M.C.; Han, S.; Jackson, V.M.; Landis, M.S.; Lettiere, D.; Limberakis, C.; Liu, Y.; Mathiowetz, A.M.; Patel, J.C.; Piotrowski, D.W.; Price, D.A.; Ruggeri, R.B.; Tess, D.A. A Small-Molecule Oral Agonist of the Human Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 8208–8226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Liang, Y.-L.; Belousoff, M.J.; Deganutti, G.; Fletcher, M.M.; Willard, F.S.; Bell, M.G.; Christe, M.E.; Sloop, K.W.; Inoue, A.; Truong, T.T.; Clydesdale, L.; Furness, S.G.B.; Christopoulos, A.; Wang, M.-W.; Miller, L.J.; Reynolds, C.A.; Danev, R.; Sexton, P.M.; Wootten, D. Activation of the GLP-1 receptor by a non-peptidic agonist. Nature 2020, 577, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, S.; Blevins, T.; Connery, L.; Rosenstock, J.; Raha, S.; Liu, R.; Ma, X.; Mather Kieren, J.; Haupt, A.; Robins, D.; Pratt, E.; Kazda, C.; Konig, M. Daily Oral GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Orforglipron for Adults with Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 389, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, E.; Ma, X.; Liu, R.; Robins, D.; Haupt, A.; Coskun, T.; Sloop, K.W.; Benson, C. Orforglipron (LY3502970), a novel, oral non-peptide glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist: A Phase 1a, blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized, single- and multiple-ascending-dose study in healthy participants. Diabetes Obes Metab 2023, 25, 2634–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, E.; Ma, X.; Liu, R.; Robins, D.; Haupt, A.; Coskun, T.; Sloop, K.W.; Benson, C. Orforglipron (LY3502970), a novel, oral non-peptide glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist: a Phase 1a, blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized, single-and multiple-ascending-dose study in healthy participants. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2023, 25, 2634–2641, (Duplicate of #21; same DOI). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, J.; Dvergsten, C.; Dunn, I.; Valcarce, C. In TTP273, Oral (nonpeptide) GLP-1R agonist: improved glycemic control without nausea and vomiting in phase 2, 2017, AMER DIABETES ASSOC 1701 N BEAUREGARD ST, ALEXANDRIA, VA 22311-1717 USA: pp. A326-A326. (Conference abstract; no DOI).

- Davies, M.; Pieber, T.R.; Hartoft-Nielsen, M.L.; Hansen, O.K.H.; Jabbour, S.; Rosenstock, J. Effect of Oral Semaglutide Compared With Placebo and Subcutaneous Semaglutide on Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2017, 318, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

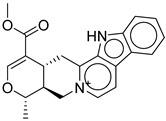

- Xue, H.; Xing, H.J.; Wang, B.; Fu, C.; Zhang, Y.S.; Qiao, X.; Guo, C.; Zhang, X.L.; Hu, B.; Zhao, X.; Deng, L.J.; Zhu, X.C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.F. Cinchonine, a Potential Oral Small-Molecule Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist, Lowers Blood Glucose and Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2023, 17, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, C.F.; Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.; Hücking, K.; Holst, J.J. Degradation of endogenous and exogenous gastric inhibitory polypeptide in healthy and in type 2 diabetic subjects as revealed using a new assay for the intact peptide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000, 85, 3575–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Ravn, L.S.; Steinberg, W.M.; Stockner, M.; Zinman, B.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Buse, J.B. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, J.; Ooi, S.L.; Pak, S.C. What Is the Mechanism Driving the Reduction of Cardiovascular Events from Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists?—A Mini Review. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, J.K.; Yadav, S.; Vats, V. Medicinal plants of India with anti-diabetic potential. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2002, 81, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akawa, A.B.; Oyinloye, B.E.; Ajiboye, B.O. Computer-aided Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Brachystegia eurycoma with Therapeutic Potential against Drug Targets of Type 2 Diabetes mellitus. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem 2022, 13, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, B.O.; Iwaloye, O.; Owolabi, O.V.; Ejeje, J.N.; Okerewa, A.; Johnson, O.O.; Udebor, A.E.; Oyinloye, B.E. Screening of potential antidiabetic phytochemicals from Gongronema latifolium leaf against therapeutic targets of type 2 diabetes mellitus: multi-targets drug design. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.S.; Alturki, M.S.; Tawfeeq, N.; Hussein, D.A.; Pottoo, F.H.; Al Khzem, A.H.; Sarafroz, M.; Abubshait, S. Discovery of Non-Peptide GLP-1 Positive Allosteric Modulators from Natural Products: Virtual Screening, Molecular Dynamics, ADMET Profiling, Repurposing, and Chemical Scaffolds Identification. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagorce, D.; Bouslama, L.; Becot, J.; Miteva, M.A.; Villoutreix, B.O. FAF-Drugs4: free ADME-tox filtering computations for chemical biology and early stages drug discovery. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3658–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickerton, G.R.; Paolini, G.V.; Besnard, J.; Muresan, S.; Hopkins, A.L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nature Chemistry 2012, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorokina, M.; Merseburger, P.; Rajan, K.; Yirik, M.A.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT online: Collection of Open Natural Products database. Journal of Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Chen, T.; Qiang, B.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z. CMNPD: a comprehensive marine natural products database towards facilitating drug discovery from the ocean. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D509–D515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Dixon, S.L.; Lowrie, J.F.; Sherman, W. Analysis and comparison of 2D fingerprints: insights into database screening performance using eight fingerprint methods. J Mol Graph Model 2010, 29, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzyoud, L.; Bryce, R.A.; Al Sorkhy, M.; Atatreh, N.; Ghattas, M.A. Structure-based assessment and druggability classification of protein–protein interaction sites. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 7975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramachaneni, G.K.; Raj, K.K.; Chalasani, L.M.; Annamraju, S.K.; Js, B.; Talluri, V.R. Shape based virtual screening and molecular docking towards designing novel pancreatic lipase inhibitors. Bioinformation 2015, 11, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; Shaw, D.E.; Francis, P.; Shenkin, P.S. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuneki, H.; Maeda, T.; Takatsuki, M.; Sekine, T.; Masui, S.; Onishi, K.; Takeda, R.; Sugiyama, M.; Sakurai, T.; Yanagisawa, M.; Wada, T.; Sasaoka, T. Bromocriptine Improves Glucose Tolerance in Obese Mice via Central Dopamine D2 Receptor-Independent Mechanism. PLoS ONE 2025, 20(3), e0320157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaddonfard, E.; Naderi, S.; Nafisi, S.; Soltanalinejad, F. Effect of Thymoquinone on Acetic Acid-Induced Visceral Nociception in Rats: Role of Central Cannabinoid and A2-Adrenergic Receptors. Vet Res Forum 2024, No. Online First. [CrossRef]

- Romeo, I.; Vallarino, G.; Turrini, F.; Roggeri, A.; Olivero, G.; Boggia, R.; Alcaro, S.; Costa, G.; Pittaluga, A. Presynaptic Release-Regulating Alpha2 Autoreceptors: Potential Molecular Target for Ellagic Acid Nutraceutical Properties. Antioxidants 2021, 10(11), 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A. C.; Steyn, L. V.; Kitzmann, J. P.; Anderson, M. J.; Mueller, K. R.; Hart, N. J.; Lynch, R. M.; Papas, K. K.; Limesand, S. W. Function and Expression of Sulfonylurea, Adrenergic, and Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptors in Isolated Porcine Islets. Xenotransplantation 2014, 21(4), 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, H.; Cui, S.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Gong, Y.; Qiu, S.; Jiao, Q.; Qin, C.; Shan, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Yin, Q.; Xu, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Li, H. Discovery and Rational Design of Natural-Product-Derived 2-Phenyl-3,4-Dihydro-2H-Benzo[f]Chromen-3-Amine Analogs as Novel and Potent Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DPP-4) Inhibitors for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59(14), 6772–6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menteşe, E.; Baltaş, N.; Bekircan, O. Synthesis and Kinetics Studies of N′-(2-(3,5-disubstituted-4H-1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)Acetyl)-6/7/8-substituted-2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-carbohydrazide Derivatives as Potent Antidiabetic Agents. Archiv der Pharmazie 2019, 352 (12). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Luo, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, M. Anti-Diabetic Compounds from the Seeds of Psoralea Corylifolia. Fitoterapia 2019, 139, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, S. H.; Ha, M. T.; Min, B. S.; Jung, H. A.; Choi, J. S. Moracin Derivatives from Morus Radix as Dual BACE1 and Cholinesterase Inhibitors with Antioxidant and Anti-Glycation Capacities. Life Sciences 2018, 210, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabet, H. K.; Abusaif, M. S.; Imran, M.; Helal, M. H.; Alaqel, S. I.; Alshehri, A.; Mohd, A. A.; Ammar, Y. A.; Ragab, A. Discovery of Novel 6-(Piperidin-1-Ylsulfonyl)-2H-Chromenes Targeting α-Glucosidase, α-Amylase, and PPAR-γ: Design, Synthesis, Virtual Screening, and Anti-Diabetic Activity for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2024, 111, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Ghazvini, S. M. B.; Safari, P.; Mobinikhaledi, A.; Moghanian, H.; Rasouli, H. Synthesis, Characterization, Anti-Diabetic Potential and DFT Studies of 7-Hydroxy-4-Methyl-2-Oxo-2H-Chromene-8-Carbaldehyde Oxime. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2018, 205, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, K.; Aggarwal, G.; Sharma, U. α-Glucosidase Inhibiting Chromene Derivatives from Ageratum Conyzoides L. Essential Oil Extracted via NADES-Assisted Hydrodistillation. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2025, 22 (1). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. The Role of Natural Products in Drug Discovery: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, *13*, 830103. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. B.; Jones, C. D. Fungal Secondary Metabolites: Biosynthesis and Applications. Front. Fungal Biol. 2023, *4*, 1088966. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. F.; Green, G. H. Phytochemical Analysis of Medicinal Plants: Recent Advances. Phytochemistry 2024, *215*, 114206. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Taylor, R. Natural Compounds as Potential Therapeutic Agents: A Pharmacological Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, *88*, 1234–1242. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Park, J. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Plant-Derived Compounds. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, *2021*, 2691525. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Rodriguez, M. Advances in the Pharmacology of Natural Bioactive Molecules. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, *98*, 456–465. [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.; Robinson, K. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2005, *73* (5), 327–335. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.; Clark, S. Recent Advances in the Isolation and Characterization of Natural Products. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, *38* (15), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; White, L. Bioactive Compounds from Traditional Medicinal Plants: Pharmacological Evaluation. Fitoterapia 2019, *137*, 104373. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Li, J. Advances in Natural Product Drug Discovery: Mechanisms and Applications. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, *83* (6), 1895–1908. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Patel, R.; Sharma, M. Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, *245*, 114892. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. D.; Smith, E. F. Antimicrobial Properties of Plant-Derived Alkaloids. Phytochemistry 2014, *97*, 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. L.; Garcia, M. P. Recent Advances in Cancer Chemoprevention Using Natural Compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2023, *88-89*, 117306. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, S. Y. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Terpenoids: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, *239*, 111920. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. B.; Miller, T. K. Bioactive Compounds from Marine Organisms: A Review of Their Pharmacological Properties. Mar. Drugs 2014, *12* (12), 5986–6003. [CrossRef]

- Rants'o, T.A.; Johan van der Westhuizen, C.; van Zyl, R.L. Optimization of covalent docking for organophosphates interaction with Anopheles acetylcholinesterase. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2022, 110, 108054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, M.; Gabriels, G.; Rants’o, T.A. In silico analysis of the melamine structural analogues interaction with calcium-sensing receptor: A potential for nephrotoxicity. Computational Toxicology 2024, 32, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P.; Roggo, S.; Schuffenhauer, A. Natural Product-likeness Score and Its Application for Prioritization of Compound Libraries. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2008, 48, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Zhang, K.Y.J. Advances in the Development of Shape Similarity Methods and Their Application in Drug Discovery. Front Chem 2018, 6, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Bittrich, S.; Chen, L.; Crichlow, G.V.; Christie, C.H.; Dalenberg, K.; Di Costanzo, L.; Duarte, J.M.; Dutta, S.; Feng, Z.; Ganesan, S.; Goodsell, D.S.; Ghosh, S.; Green, R.K.; Guranović, V.; Guzenko, D.; Hudson, B.P.; Lawson, C.L.; Liang, Y.; Lowe, R.; Namkoong, H.; Peisach, E.; Persikova, I.; Randle, C.; Rose, A.; Rose, Y.; Sali, A.; Segura, J.; Sekharan, M.; Shao, C.; Tao, Y.P.; Voigt, M.; Westbrook, J.D.; Young, J.Y.; Zardecki, C.; Zhuravleva, M. RCSB Protein Data Bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D437–d451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, E.; Damm, W.; Maple, J.; Wu, C.; Reboul, M.; Xiang, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Lupyan, D.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Knight, J.L.; Kaus, J.W.; Cerutti, D.S.; Krilov, G.; Jorgensen, W.L.; Abel, R.; Friesner, R.A. OPLS3: A Force Field Providing Broad Coverage of Drug-like Small Molecules and Proteins. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2016, 12, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, T.; Ohue, M.; Akiyama, Y. Multiple grid arrangement improves ligand docking with unknown binding sites: Application to the inverse docking problem. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2018, 73, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rants'o, T.A.; van Greunen, D.G.; van der Westhuizen, C.J.; Riley, D.L.; Panayides, J.L.; Koekemoer, L.L.; van Zyl, R.L. The in silico and in vitro analysis of donepezil derivatives for Anopheles acetylcholinesterase inhibition. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0277363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaundoo, R.; Bohmann, J.; Gutierrez, G.E.; Klimas, N.; Broderick, G.; Craddock, T.J.A. Using a Consensus Docking Approach to Predict Adverse Drug Reactions in Combination Drug Therapies for Gulf War Illness. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, M.S.; Gomaa, M.S.; Tawfeeq, N.; Al Khzem, A.H.; Shaik, M.B.; Alshaikh Jafar, M.; Alsamen, M.; Al Nahab, H.; Al-Eid, M.; Almutawah, A.; et al. A Multifaceted Computational Approach to Identify PAD4 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Metabolites 2025, 15, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, D. In Silico Investigation of the Human GTP Cyclohydrolase 1 Enzyme Reveals the Potential of Drug Repurposing Approaches towards the Discovery of Effective BH4 Therapeutics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(2), 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturki, M.S. Exploring Marine-Derived Compounds: In Silico Discovery of Selective Ketohexokinase (KHK) Inhibitors for Metabolic Disease Therapy. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, K.J.; Chow, E.; Xu, H.; Dror, R.O.; Eastwood, M.P.; Gregersen, B.A.; Klepeis, J.L.; Kolossvary, I.; Moraes, M.A.; Sacerdoti, F.D. In Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters, 2006, pp. 84-es. (Conference proceedings; no DOI).

- Al Khzem, A.H.; Shoaib, T.H.; Mukhtar, R.M.; Alturki, M.S.; Gomaa, M.S.; Hussein, D.; Tawfeeq, N.; Bano, M.; Sarafroz, M.; Alzahrani, R.; et al. Repurposing FDA-Approved Agents to Develop a Prototype Helicobacter pylori Shikimate Kinase (HPSK) Inhibitor: A Computational Approach Using Virtual Screening, MM-GBSA Calculations, MD Simulations, and DFT Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Wang, M.-W. Structural pharmacology and mechanisms of GLP-1R signaling. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2025, 46, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Postma, J.P.M.; van Gunsteren, W.F.; Hermans, J. Interaction Models for Water in Relation to Protein Hydration. In Intermolecular Forces: Proceedings of the Fourteenth Jerusalem Symposium on Quantum Chemistry and Biochemistry Held in Jerusalem, Israel, April 13–16, 1981; Pullman, B., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1981; pp. 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Maxwell, D.S.; Tirado-Rives, J. Development and Testing of the OPLS All-Atom Force Field on Conformational Energetics and Properties of Organic Liquids. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1996, 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeguchi, M. Partial rigid-body dynamics in NPT, NPAT and NPγT ensembles for proteins and membranes. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2004, 25, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, R.A.; Predescu, C.; Ierardi, D.J.; Mackenzie, K.M.; Eastwood, M.P.; Dror, R.O.; Shaw, D.E. Accurate and efficient integration for molecular dynamics simulations at constant temperature and pressure. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2013, 139, 164106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, L.; Manione, R.; Renditore, P. A Formal Description Language for the Modelling and Simulation of Timed Interaction Diagrams. In Formal Description Techniques IX: Theory, application and tools; Gotzhein, R., Bredereke, J., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1996; pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, M.S.; Tawfeeq, N.; Alissa, A.; Ahbail, Z.; S. Gomaa, M.; Al Khzem, A.H.; Rants'o, T.A.; Akbar, M.J.; Alharbi, W.S.; Alshehri, B.Y.; Alotaibi, A.N.; Almughem, F.A.; Alshehri, A.A. Targeting KRAS G12C and G12S mutations in lung cancer: In silico drug repurposing and antiproliferative assessment on A549 cells. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2025, 52, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollman, P.A.; Massova, I.; Reyes, C.; Kuhn, B.; Huo, S.; Chong, L.; Lee, M.; Lee, T.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; Donini, O.; Cieplak, P.; Srinivasan, J.; Case, D.A.; Cheatham, T.E. Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Accounts of Chemical Research 2000, 33, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, D.E.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hit No.* | Structure | ID | XP Score | MM-BBSA dG Bind | Shape Similarity* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

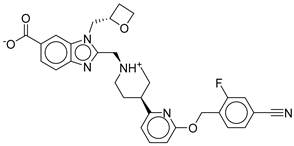

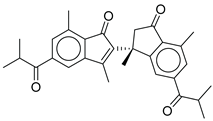

|

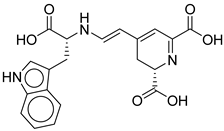

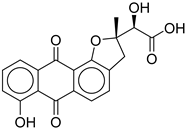

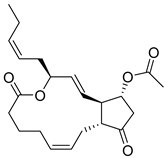

1 |

|

CNP0593098.1 |

-13.835 |

-84.69 |

0.346 |

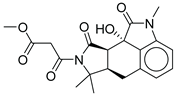

|

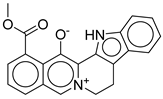

2 |

|

CNP0542406.3 |

-13.657 |

-83.94 |

0.315 |

|

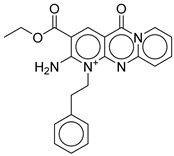

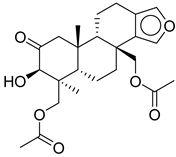

3 |

|

CNP0510864.0 |

-13.513 |

-82.51 |

0.305 |

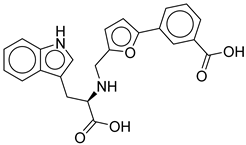

|

4 |

|

CNP0294111.0 |

-13.506 |

-84.61 |

0.344 |

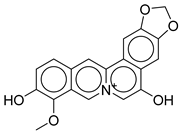

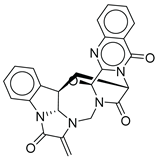

| 5 |  |

CNP0513629.0 |

-13.114 |

-76.49 |

0.308 |

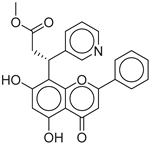

|

6 |

|

CNP0402650.0 |

-13.003 |

-86.43 |

0.325 |

|

7 |

|

CNP0449126.4 |

-12.954 |

-66.07 |

0.320 |

|

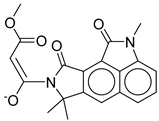

8 |

|

CNP0576495.0 |

-12.770 |

-76.87 |

0.312 |

|

9 |

|

CNP0510059.0 |

-12.563 |

-84.80 |

0.339 |

|

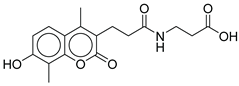

10 |

|

CNP0311770.0 | -12.532 | -85.80 | 0.310 |

|

Control |

|

-12.040 |

-116.06 |

1.000 |

| Hit No.* | Structure | ID | XP Score | MM-BBSA dG Bind | Shape Similarity* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

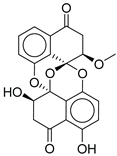

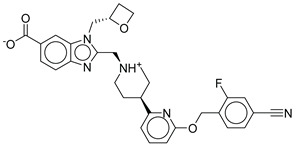

| 11 |  |

CMNPD27661 |

-12.806 |

-71.68 |

0.303 |

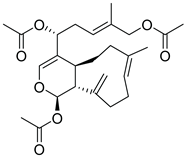

| 12 |  |

CMNPD2041 | -11.609 | -96.80 | 0.327 |

| 13 |  |

CMNPD24592 | -11.575 | -74.09 | 0.315 |

| 14 |  |

CMNPD4014 | -11.495 | -95.02 | 0.302 |

| 15 |  |

CMNPD9270 | -11.427 | -97.33 | 0.375 |

| 16 |  |

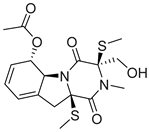

CMNPD26002 |

-11.116 |

-100.43 |

0.320 |

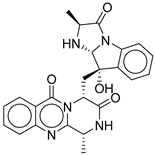

| 17 |  |

CMNPD5314 | -10.805 | -75.01 | 0.343 |

| 18 |  |

CMNPD22795 | -10.798 | -88.67 | 0.363 |

| 19 |  |

CMNPD27343 | -10.372 | -61.54 | 0.311 |

| 20 |  |

CMNPD24593 | -10.190 | -52.04 | 0.352 |

| Control |  |

-12.040 | -116.06 | 1.000 |

| COCONUT ID | Compound Name / Description | Anti-Diabetic/GLP-1 Literature Evidence (2015-2025)[41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

|---|---|---|

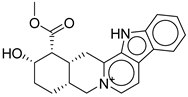

| CNP0593098.1 | 3,4,5,6-Tetradehydroyohimbine | Yohimbine (parent compound) has demonstrated antidiabetic effects in STZ-induced diabetic rats. It acts as an alpha-2 adrenoceptor antagonist, improving glucose tolerance, lowering blood glucose, and improving lipid profiles. The mechanism is thought to involve increased insulin secretion by blocking inhibitory catecholaminergic tone in pancreatic islets. No direct evidence for GLP-1 agonism or for the specific dehydro-derivative. |

| CNP0542406.3 | (15S)-19-(methoxycarbonyl)-16-methyl-17-oxa-3,13λ⁵-diazapentacyclo[11.8.0.0²,¹⁰.0⁴,⁹.0¹⁵,²⁰]henicosa-1(13),2(10),4,6,8,11,18-heptaen-13-ylium | No direct literature for this structure |

| CNP0510864.0 | 4-[2-[[1-carboxy-2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]ethenyl]-2,3-dihydropyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid | No direct literature for this structure |

| CNP0294111.0 | 3-[5-[[[1-carboxy-2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]amino]methyl]furan-2-yl]benzoic acid | No direct studies. |

| CNP0513629.0 | 16-methoxy-5,7-dioxa-13-azoniapentacyclo[11.8.0.0²,¹⁰.0⁴,⁸.0¹⁵,²⁰]henicosa-1,3,8,10,12,14,16,18,20-nonaene-11,17-diol | No direct anti-diabetic or GLP-1related studies for this structure. |

| CNP0402650.0 | methyl 3-(5,7-dihydroxy-4-oxo-2-phenyl-4H-chromen-8-yl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)propanoate | Chromen derivatives and flavonoids are widely studied for anti-diabetic effects, often through antioxidant and insulin-sensitizing mechanisms, but no direct evidence |

| CNP0449126.4 | (2S)-2-hydroxy-2-[(2S)-7-hydroxy-2-methyl-6,11-dioxo-3H-naphtho[2,3-g]benzofuran-2-yl]acetic acid | Benzofuran derivatives have shown anti-diabetic effects but no direct study for this compound. |

| CNP0576495.0 | 19-methoxycarbonyl-3-aza-13-azoniapentacyclo[11.8.0.0²,¹⁰.0⁴,⁹.0¹⁵,²⁰]henicosa-1(13),2(10),4,6,8,14,16,18,20-nonaen-21-olate | No direct literature for anti-diabetic or GLP-1 effects. |

| CNP0510059.0 | ethyl 6-amino-2-oxo-7-(2-phenylethyl)-1,9-diaza-7-azoniatricyclo[8.4.0.0³,⁸]tetradeca-3(8),4,6,9,11,13-hexaene-5-carboxylate | No direct literature for anti-diabetic or GLP-1 effects. |

| CNP0311770.0 | STL522422; 3-[3-(7-hydroxy-4,8-dimethyl-2-oxo-chromen-3-yl)propanoylamino]propanoic acid | Chromen (coumarin) derivatives show anti-diabetic effects (antioxidant, insulin-sensitizing) |

| CMNPD ID | Compound Name | Structural Class / Source | Direct Anti-Diabetic/GLP-1 Evidence [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66] | Mechanistic/Structural Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMNPD27661 | preussomerin M | Polyketide (fungal) | No direct anti-diabetic or GLP-1 literature was found for this compound. | Polyketide-type marine metabolites are being explored as anti-diabetic |

| CMNPD2041 | waixenicin A | Diterpene (soft coral) | No direct anti-diabetic or GLP-1 literature found for this compound. | Marine diterpenes show anti-inflammatory and metabolic regulatory effects. |

| CMNPD24592 | speradine D | Alkaloid (marine fungus) | No direct studies for this structure; marine alkaloids are reported to enhance glucose uptake, insulin sensitivity, and AMPK activity. | Alkaloids from marine sources are highlighted as promising anti-diabetic agents via AMPK/GLUT4 pathways. |

| CMNPD4014 | PGE3-1,15-lactone-11-acetate | Prostaglandin derivative | No direct anti-diabetic or GLP-1 evidence; some marine prostaglandins have anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects. | Prostaglandin derivatives may indirectly affect glucose metabolism via inflammation modulation. |

| CMNPD9270 | speradine E | Benzofuran derivative | No direct studies; marine benzofurans are under investigation for antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory effects relevant to diabetes. | Benzofuran derivatives can inhibit α-glucosidase and reduce oxidative stress in β-cells. |

| CMNPD26002 | 6-acetylbisdethiobis(methylthio)gliotoxin | Epipolythiodioxopiperazine | No direct anti-diabetic/GLP-1 studies | N/A |

| CMNPD5314 | fumiquinazoline B | Quinazoline alkaloid | No direct studies for this compound; marine quinazoline alkaloids show anti-diabetic potential via enzyme inhibition and AMPK action. | Quinazoline alkaloids are highlighted for PTP1B inhibition, and AMPK activation. |

| CMNPD22795 | anthogorgiene I | Polycyclic aromatic (coral) | No direct anti-diabetic/GLP-1 evidence; marine polycyclic aromatics may have metabolic effects, but data are limited. | Structural novelty; potential for redox and enzyme modulation. |

| CMNPD27343 | versiquinazoline B | Quinazoline alkaloid | No direct anti-diabetic/GLP-1 studies | N/A |

| CMNPD24593 | speradine E | Alkaloid (marine fungus) | No direct studies | Alkaloids from marine origin reported with anti-diabetic activities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).