Submitted:

24 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Neutrophilia in the Bloodstream of Obese Patients

Activation of Neutrophils in the Bloodstream of Obese Patients

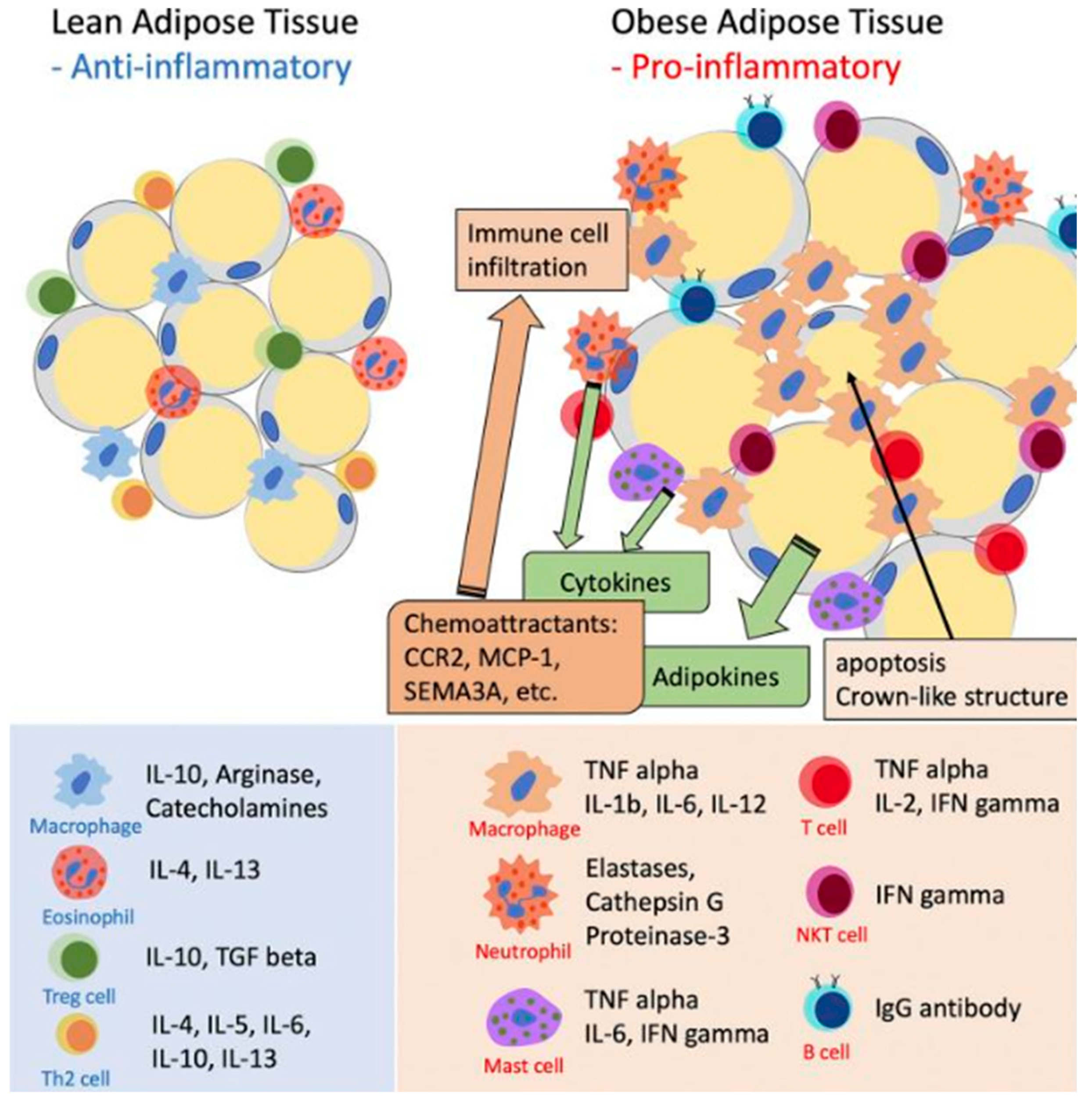

Recruitment of Monocytes and Further Differentiation into M1 Macrophages Causes Adipose Tissue Inflammation

Adipose Tissue Inflammation Leads to Systemic Inflammation in Obesity

Contribution of Adipose Tissue Inflammation to Systemic Inflammation

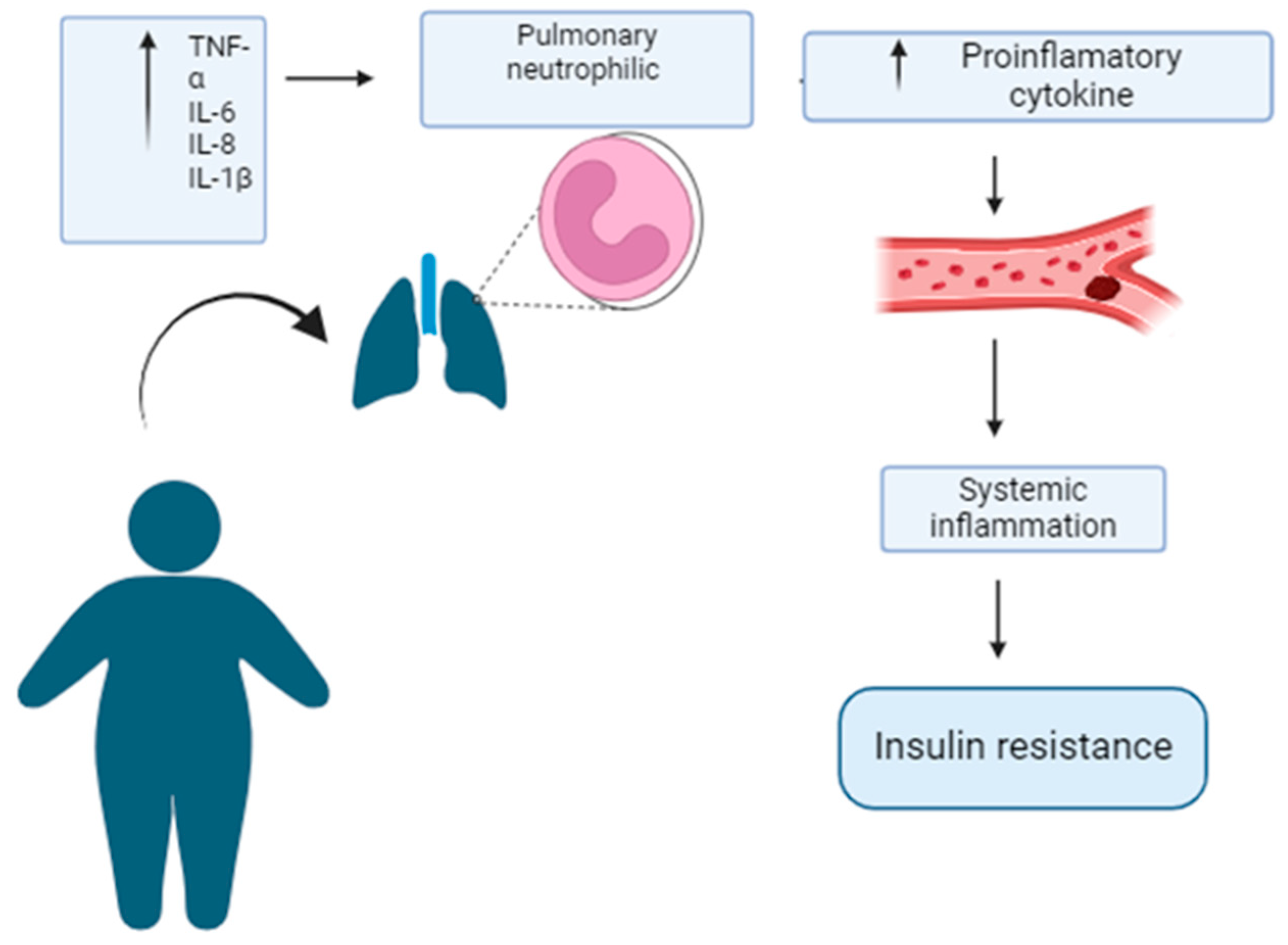

Adipose Tissue Inflammation Causes Pulmonary Neutrophilic Inflammation in Obesity

Mechanical Effects of Obesity on Lung Function

Pulmonary Neutrophilic Inflammation in Obesity-Associated Metabolic Risk

Concluding Remarks and Therapeutic Perspectives

Acknowledgments

References

- Abete, I. et al. Association of lifestyle factors and inflammation with sarcopenic obesity: data from the PREDIMED-Plus trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10, 974-984. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B. A. et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet (London, England) 378, 804-814. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Nedunchezhiyan, U. et al. Obesity, Inflammation, and Immune System in Osteoarthritis. Front Immunol 13, 907750. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Masenga, S. K., Kabwe, L. S., Chakulya, M. & Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, 7898 (2023).

- Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. New England Journal of Medicine 377, 13-27, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Jaitovich, A. & Hall, J. B. The flux of energy in critical illness and the obesity paradox. Physiol Rev 105, 1487-1552. (2025). [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, P. Obesity and lung inflammation. Journal of Applied Physiology 108, 722-728. (2009). [CrossRef]

- Gummlich, L. Obesity-induced neutrophil reprogramming. Nat Rev Cancer 21, 412. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, M. et al. Monocyte infiltration into obese and fibrilized tissues is regulated by PILRalpha. Eur J Immunol 46, 1214-1223. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Shantaram, D. et al. Obesity-associated microbiomes instigate visceral adipose tissue inflammation by recruitment of distinct neutrophils. Nat Commun 15, 5434. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T., Autieri, M. V. & Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 320, C375-C391. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. K., Gutierrez, D. A. & Hasty, A. H. Adipose tissue recruitment of leukocytes. Curr Opin Lipidol 21, 172-177. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Poblete, J. M. S. et al. Macrophage HIF-1alpha mediates obesity-related adipose tissue dysfunction via interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 318, E689-E700. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Peris, A. et al. Obesity and inflammatory response in moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a single center pilot study. Minerva Med 116, 89-93. (2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., You, L., Zhou, X. & Li, Y. Associations between metabolic score for visceral fat and adult lung functions from NHANES 2007-2012. Front Nutr 11, 1436652. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gomez Mejiba, S. E. & Ramirez, D. C. Neutrophilic Inflammation and Diseases: Pathophysiology, Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. (Eliva Press, 2020).

- Gomez-Mejiba, S. E. et al. Inhalation of environmental stressors & chronic inflammation: autoimmunity and neurodegeneration. Mutat Res 674, 62-72. (2009). [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, S. et al. Neutrophils mediate insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet through secreted elastase. Nat Med 18, 1407-1412. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Rosales, C. Neutrophil: A Cell with Many Roles in Inflammation or Several Cell Types? Frontiers in physiology 9, 113. (2018). [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Querol, E. & Rosales, C. Neutrophils Actively Contribute to Obesity-Associated Inflammation and Pathological Complications. Cells 11. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Querol, E. & Rosales, C. Neutrophils Actively Contribute to Obesity-Associated Inflammation and Pathological Complications. Cells 11, 1883 (2022).

- Kordonowy, L. L. et al. Obesity is associated with neutrophil dysfunction and attenuation of murine acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47, 120-127. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Li, N. et al. Correlation of White Blood Cell, Neutrophils, and Hemoglobin with Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 16, 1347-1355. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M. et al. The mechanistic role of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio perturbations in the leading non communicable lifestyle diseases. F1000Research 11, 960. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Baragetti, A. et al. Neutrophil aging exacerbates high fat diet induced metabolic alterations. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 144, 155576. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Suren Garg, S., Kushwaha, K., Dubey, R. & Gupta, J. Association between obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance: Insights into signaling pathways and therapeutic interventions. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 200, 110691. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K. V., Deng, M. & Ting, J. P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nature reviews. Immunology 19, 477-489. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., Dragon, S., Becker, A. & Gounni, A. S. Leptin inhibits neutrophil apoptosis in children via ERK/NF-κB-dependent pathways. PloS one 8, e55249. (2013). [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, H. et al. Circulating mononuclear cells in the obese are in a proinflammatory state. Circulation 110, 1564-1571. (2004). [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Cervera, A., Soehnlein, O. & Kenne, E. Neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 19, 177-191. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J. B. & O' Brien, P. E. Obesity and the White Blood Cell Count: Changes with Sustained Weight Loss. Obesity Surgery 16, 251-257. (2006). [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Ali, V. et al. Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Releases Interleukin-6, However, Not Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, in Vivo1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 82, 4196-4200. (1997). [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A., Conus, S. b., Schmid, I. s. & Simon, H.-U. Apoptotic Pathways Are Inhibited by Leptin Receptor Activation in Neutrophils1. The Journal of Immunology 174, 8090-8096. (2005). [CrossRef]

- Artemniak-Wojtowicz, D., Kucharska, A. & Pyrżak, B. Obesity and chronic inflammation crosslinking. Central European Journal of Immunology 45, 461-468. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Bahadir, A. et al. Is the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio indicative of inflammatory state in patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome? Anatol J Cardiol 15, 816-822. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Barden, A. et al. Effect of weight loss on neutrophil resolvins in the metabolic syndrome. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 148, 25-29. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Della Vedova, M. C. et al. 410 - Neutrophils in the Obese Lung: A Mechanistic Study in a Mouse Model of Metabolic Syndrome. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 100, S171-S172. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Cottam, D. R., Schaefer, P. A., Fahmy, D., Shaftan, G. W. & Angus, L. D. The effect of obesity on neutrophil Fc receptors and adhesion molecules (CD16, CD11b, CD62L). Obes Surg 12, 230-235. (2002). [CrossRef]

- Elgazar-Carmon, V., Rudich, A., Hadad, N. & Levy, R. Neutrophils transiently infiltrate intra-abdominal fat early in the course of high-fat feeding. J Lipid Res 49, 1894-1903. (2008). [CrossRef]

- Goossens, G. H. The role of adipose tissue dysfunction in the pathogenesis of obesity-related insulin resistance. Physiology & behavior 94, 206-218. (2008). [CrossRef]

- Shi, H. et al. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 116, 3015-3025. (2006). [CrossRef]

- Cinti, S. et al. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. Journal of lipid research 46, 2347-2355. (2005). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Y. et al. Obesity-associated improvements in metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 117, 2621-2637. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Sethi, J. K. & Vidal-Puig, A. J. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. Adipose tissue function and plasticity orchestrate nutritional adaptation. Journal of lipid research 48, 1253-1262. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H. & Moschen, A. R. Role of adiponectin and PBEF/visfatin as regulators of inflammation: involvement in obesity-associated diseases. Clin Sci (Lond) 114, 275-288. (2008). [CrossRef]

- Antuna-Puente, B., Feve, B., Fellahi, S. & Bastard, J. P. [Obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance: which role for adipokines]. Therapie 62, 285-292. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Brock, J. M., Billeter, A., Müller-Stich, B. P. & Herth, F. Obesity and the Lung: What We Know Today. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases 99, 856-866. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ayed, K. et al. Obesity and cancer: focus on leptin. Molecular biology reports 50, 6177-6189. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Münzberg, H., Singh, P., Heymsfield, S. B., Yu, S. & Morrison, C. D. Recent advances in understanding the role of leptin in energy homeostasis. F1000Research 9. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Stern, J. H., Rutkowski, J. M. & Scherer, P. E. Adiponectin, Leptin, and Fatty Acids in the Maintenance of Metabolic Homeostasis through Adipose Tissue Crosstalk. Cell metabolism 23, 770-784. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A., Aronoff, D. M., Phipps, J., Goel, D. & Mancuso, P. Leptin improves pulmonary bacterial clearance and survival in ob/ob mice during pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Exp Immunol 150, 332-339. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Gogiraju, R. et al. Deletion of endothelial leptin receptors in mice promotes diet-induced obesity. Scientific reports 13, 8276. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G., Sanna, V., Fontana, S. & Zappacosta, S. Leptin as a novel therapeutic target for immune intervention. Current drug targets. Inflammation and allergy 1, 13-22. (2002). [CrossRef]

- Bassi, M. et al. Control of respiratory and cardiovascular functions by leptin. Life sciences 125, 25-31. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Fan, X., Yuan, W., Huang, W. & Lin, Z. Recent progress in leptin signaling from a structural perspective and its implications for diseases. Biochimie 212, 60-75. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, A., Sánchez-Jiménez, F., Vilariño-García, T. & Sánchez-Margalet, V. Role of Leptin in Inflammation and Vice Versa. International journal of molecular sciences 21. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V. D. et al. Ghrelin inhibits leptin- and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. The Journal of clinical investigation 114, 57-66. (2004). [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Riejos, P. et al. Role of leptin in the activation of immune cells. Mediators of inflammation 2010, 568343. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Scheller, J., Chalaris, A., Schmidt-Arras, D. & Rose-John, S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1813, 878-888. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. A. & Jones, S. A. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nature immunology 16, 448-457. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T., Narazaki, M. & Kishimoto, T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 6, a016295. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G. S., Shargill, N. S. & Spiegelman, B. M. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science (New York, N.Y.) 259, 87-91. (1993). [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Ali, V., Pinkney, J. H. & Coppack, S. W. Adipose tissue as an endocrine and paracrine organ. International Journal of Obesity 22, 1145-1158. (1998). [CrossRef]

- Uysal, K. T., Wiesbrock, S. M., Marino, M. W. & Hotamisligil, G. S. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Nature 389, 610-614. (1997). [CrossRef]

- Kunz, H. E. et al. Adipose tissue macrophage populations and inflammation are associated with systemic inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 321, E105-E121. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, N. & Patial, S. Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in macrophages. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression 20, 87-103. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. S. et al. Inflammation is necessary for long-term but not short-term high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 60, 2474-2483. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Anforth, H. R. et al. Biological activity and brain actions of recombinant rat interleukin-1alpha and interleukin-1beta. European cytokine network 9, 279-288 (1998).

- Wallenius, V. et al. Interleukin-6-deficient mice develop mature-onset obesity. Nature medicine 8, 75-79. (2002). [CrossRef]

- Myers, M. G., Jr. & Olson, D. P. Central nervous system control of metabolism. Nature 491, 357-363. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Grosfeld, A. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 transactivates the human leptin gene promoter. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 42953-42957. (2002). [CrossRef]

- Grunfeld, C. et al. Endotoxin and cytokines induce expression of leptin, the ob gene product, in hamsters. The Journal of clinical investigation 97, 2152-2157. (1996). [CrossRef]

- Gan, L. et al. TNF-α upregulates protein level and cell surface expression of the leptin receptor by stimulating its export via a PKC-dependent mechanism. Endocrinology 153, 5821-5833. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, I. P. et al. Is Obesity Associated with Altered Energy Expenditure? Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) 7, 476-487. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Oliveros, E., Somers, V. K., Sochor, O., Goel, K. & Lopez-Jimenez, F. The concept of normal weight obesity. Progress in cardiovascular diseases 56, 426-433. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Altintas, M. M. et al. Mast cells, macrophages, and crown-like structures distinguish subcutaneous from visceral fat in mice. Journal of lipid research 52, 480-488. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, Y. et al. Comparison of mitochondrial and macrophage content between subcutaneous and visceral fat in db/db mice. Experimental and molecular pathology 83, 73-83. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Hardy, O. T. et al. Body mass index-independent inflammation in omental adipose tissue associated with insulin resistance in morbid obesity. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery 7, 60-67. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Poulain-Godefroy, O., Lecoeur, C., Pattou, F., Frühbeck, G. & Froguel, P. Inflammation is associated with a decrease of lipogenic factors in omental fat in women. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 295, R1-7. (2008). [CrossRef]

- Klöting, N. et al. Insulin-sensitive obesity. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 299, E506-515. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Ortega Martinez de Victoria, E. et al. Macrophage content in subcutaneous adipose tissue: associations with adiposity, age, inflammatory markers, and whole-body insulin action in healthy Pima Indians. Diabetes 58, 385-393. (2009). [CrossRef]

- Longo, M. et al. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. International journal of molecular sciences 20. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Yunna, C., Mengru, H., Lei, W. & Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. European journal of pharmacology 877, 173090. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ros Pérez, M. & Medina-Gómez, G. [Obesity, adipogenesis and insulin resistance]. Endocrinologia y nutricion : organo de la Sociedad Espanola de Endocrinologia y Nutricion 58, 360-369. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Suren Garg, S., Kushwaha, K., Dubey, R. & Gupta, J. Association between obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance: Insights into signaling pathways and therapeutic interventions. Diabetes research and clinical practice 200, 110691. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Fahed, G. et al. Metabolic Syndrome: Updates on Pathophysiology and Management in 2021. International journal of molecular sciences 23. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Meshkani, R. & Adeli, K. Hepatic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Clinical biochemistry 42, 1331-1346. (2009). [CrossRef]

- Iafusco, D. et al. From Metabolic Syndrome to Type 2 Diabetes in Youth. Children (Basel, Switzerland) 10. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Baffi, C. W. et al. Metabolic Syndrome and the Lung. Chest 149, 1525-1534. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Vedova, M. C. D. et al. Diet-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation and Incipient Fibrosis in Mice: a Possible Role of Neutrophilic Inflammation. Inflammation 42, 1886-1900. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zatterale, F. et al. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Physiol 10, 1607. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R. A., Schwartzman, I. N. & Shore, S. A. Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 levels are associated with changes in serum leptin concentrations following ozone-induced airway inflammation. Chest 123, 369 s-370 s (2003).

- Faggioni, R. et al. IL-1 beta mediates leptin induction during inflammation. The American journal of physiology 274, R204-208. (1998). [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A. E. & Peters, U. The effect of obesity on lung function. Expert review of respiratory medicine 12, 755-767. (2018). [CrossRef]

- Naik, D., Joshi, A., Paul, T. V. & Thomas, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the metabolic syndrome: Consequences of a dual threat. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism 18, 608-616. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Garcia, U. et al. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. International journal of molecular sciences 21. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. M. H., Selemidis, S., Bozinovski, S. & Vlahos, R. Pathobiological mechanisms underlying metabolic syndrome (MetS) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): clinical significance and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacology & therapeutics 198, 160-188. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wernstedt Asterholm, I. et al. Adipocyte Inflammation Is Essential for Healthy Adipose Tissue Expansion and Remodeling. Cell metabolism 20, 103-118. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Rada, C. et al. Análisis de la relación entre diabetes mellitus tipo 2 y la obesidad con los factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Journal of Negative and No Positive Results 6, 411-433 (2021).

- Sagun, G. et al. The relation between insulin resistance and lung function: a cross sectional study. BMC pulmonary medicine 15, 139. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Littleton, S. W. Impact of obesity on respiratory function. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.) 17, 43-49. (2012). [CrossRef]

- Jasper, A. E., McIver, W. J., Sapey, E. & Walton, G. M. Understanding the role of neutrophils in chronic inflammatory airway disease. F1000Research 8. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L., Kacmarek, R. & Berra, L. Ventilatory Mechanics in the Patient with Obesity. Anesthesiology 132, 1246-1256. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. S., Buras, E. D. & Balasubramanyam, A. The role of the immune system in obesity and insulin resistance. Journal of obesity 2013, 616193. (2013). [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, F. et al. Pulmonary Hypertension and Obesity: Focus on Adiponectin. International journal of molecular sciences 20. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. R. & Shashaty, M. G. S. Impact of Obesity in Critical Illness. Chest 160, 2135-2145. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Umbrello, M., Fumagalli, J., Pesenti, A. & Chiumello, D. Pathophysiology and Management of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Obese Patients. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine 40, 40-56. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, D. C. & Gomez Mejiba, S. E. Pulmonary Neutrophilic Inflammation and Noncommunicable Diseases: Pathophysiology, Redox Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutics. Antioxid Redox Signal 33, 211-227. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Golforoush, P., Yellon, D. M. & Davidson, S. M. Mouse models of atherosclerosis and their suitability for the study of myocardial infarction. Basic research in cardiology 115, 73. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J. & Smith, T. Malnutrition: causes and consequences. Clinical medicine (London, England) 10, 624-627. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Baker, R. G., Hayden, M. S. & Ghosh, S. NF-κB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell metabolism 13, 11-22. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Klein, S., Gastaldelli, A., Yki-Järvinen, H. & Scherer, P. E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell metabolism 34, 11-20. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E. D. & Spiegelman, B. M. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell 156, 20-44. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Tilton, S. C. et al. Diet-induced obesity reprograms the inflammatory response of the murine lung to inhaled endotoxin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 267, 137-148. (2013). [CrossRef]

- Ubags, N. D. et al. A Comparative Study of Lung Host Defense in Murine Obesity Models. Insights into Neutrophil Function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 55, 188-200. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. M. & An, J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. International anesthesiology clinics 45, 27-37. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G. S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444, 860-867. (2006). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. & Nakayama, T. Inflammation, a link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Mediators of inflammation 2010, 535918. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Ruck, L., Wiegand, S. & Kühnen, P. Relevance and consequence of chronic inflammation for obesity development. Molecular and cellular pediatrics 10, 16. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Püschel, G. P., Klauder, J. & Henkel, J. Macrophages, Low-Grade Inflammation, Insulin Resistance and Hyperinsulinemia: A Mutual Ambiguous Relationship in the Development of Metabolic Diseases. Journal of clinical medicine 11. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Bonamichi, B. & Lee, J. Unusual Suspects in the Development of Obesity-Induced Inflammation and Insulin Resistance: NK cells, iNKT cells, and ILCs. Diabetes Metab J 41, 229-250. (2017). [CrossRef]

- Chmelar, J., Chung, K. J. & Chavakis, T. The role of innate immune cells in obese adipose tissue inflammation and development of insulin resistance. Thromb Hemost 109, 399-406. (2013). [CrossRef]

- de Luca, C. & Olefsky, J. M. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett 582, 97-105. (2008). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).