Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

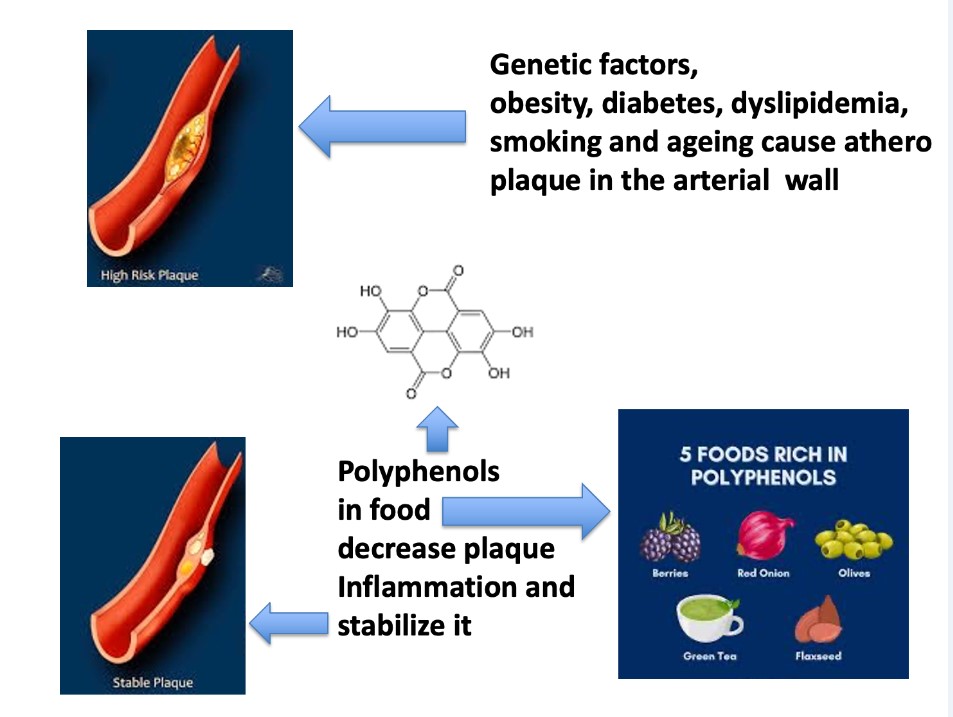

Introduction

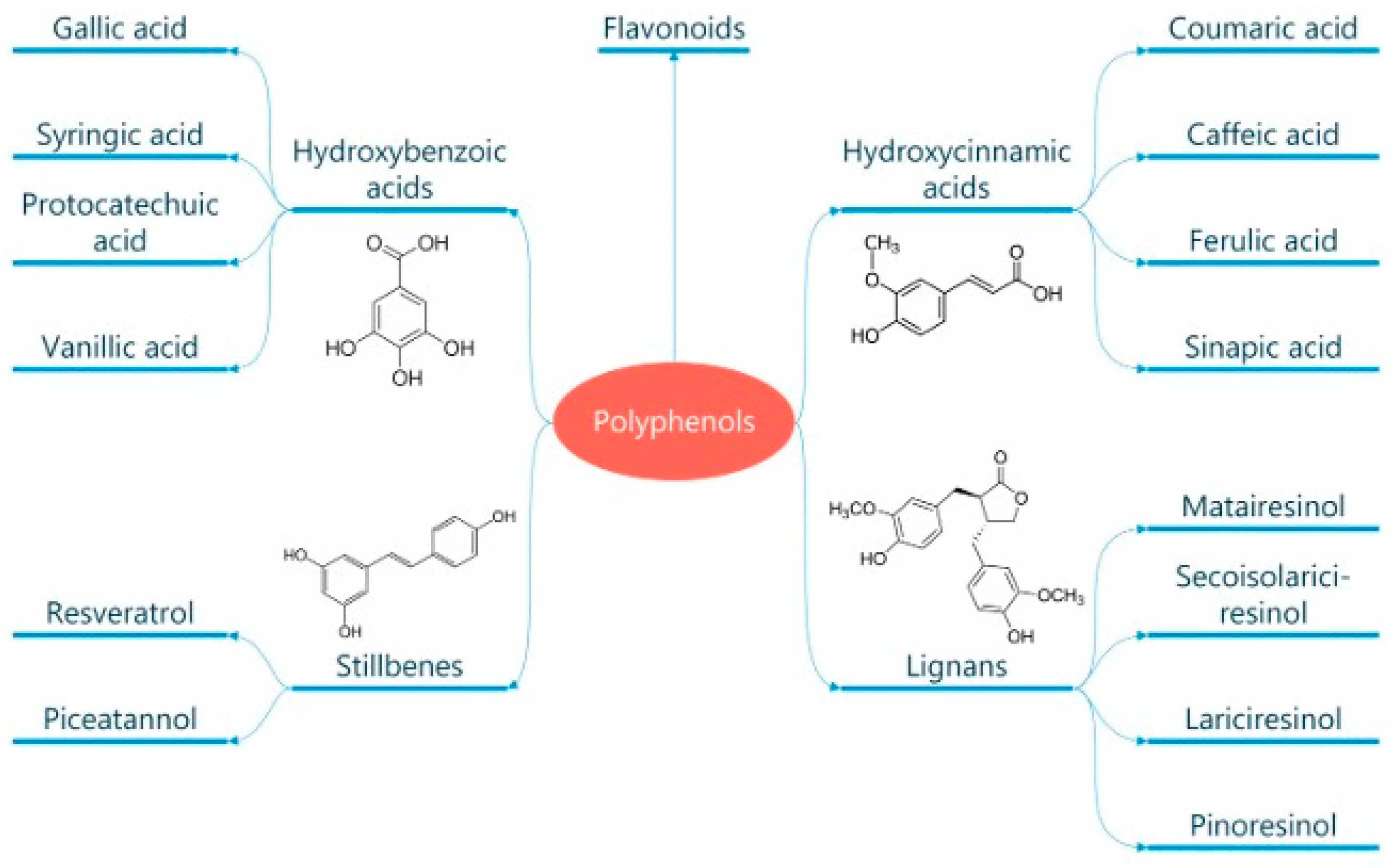

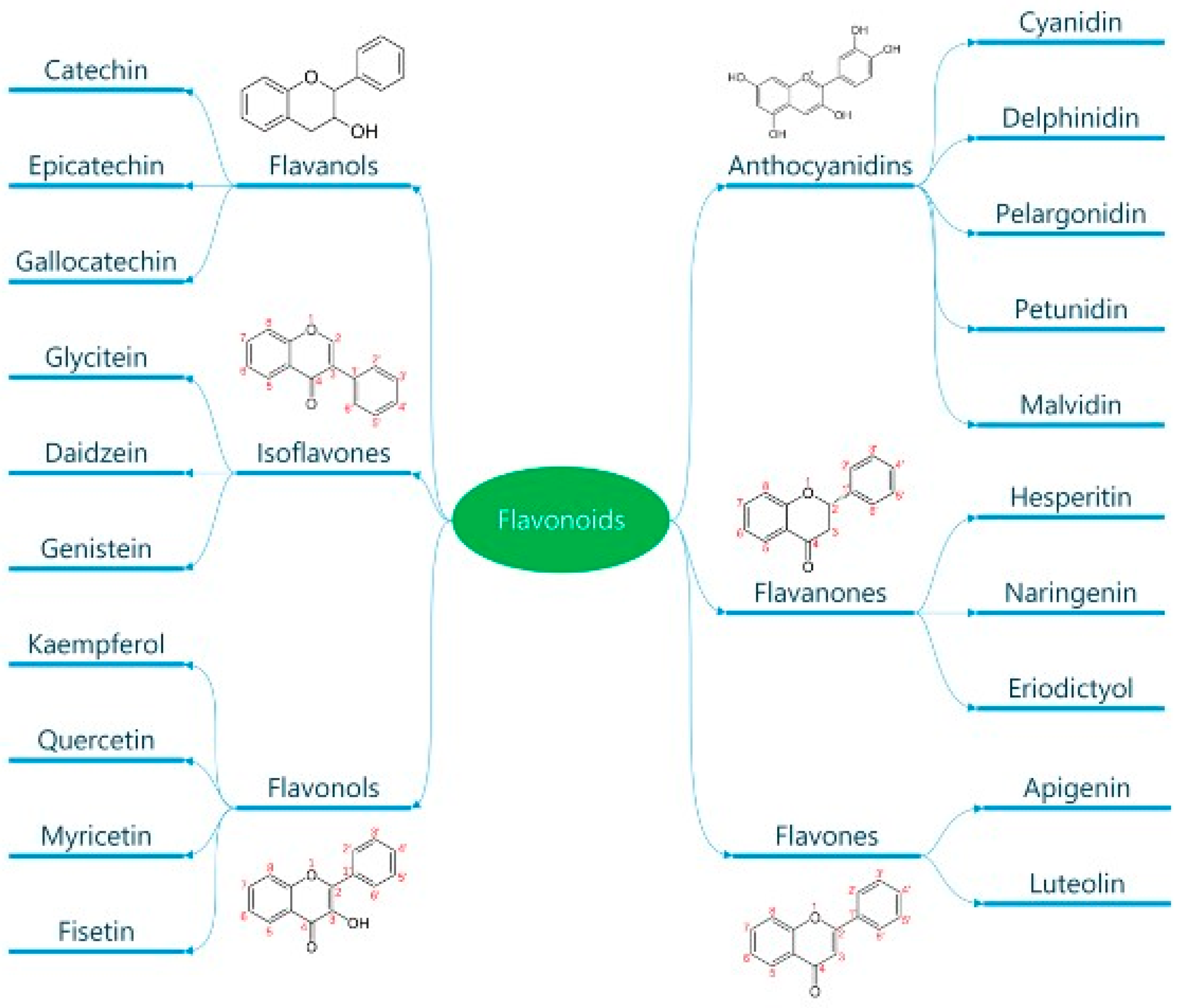

Classification and General Properties of Polyphenols

Absorption of Polyphenols

Antioxidant Properties of Polyphenols

Effects of Polyphenols on the Vascular Endothelium

Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Polyphenols

Anti-Atherogenic Effects of Polyphenols

Focus on the Cardiovascular Effects of Relevant Polyphenols

Flavan-3-Ols

Resveratrol

Curcumin

Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols

Cardiovascular Effects of Wheat Polyphenols

Adverse Efeects of Polyphenols

Conclusions and Future Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Abbreviations

| ANG II | Angiotensin II |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| ECs | Endothelial Cells |

| EGCG | Epigallo-Catechin-Gallate |

| ENOS | Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| EVO | Extra Virgin Olive Oil |

| FGM | Fermented Grape Marc |

| FMD | Flood-Mediated Dilation |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| ICAM | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LOX | Lipoxigenase |

| MAD | Malondialdehyde |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MD | Mediterranean Diet |

| MI | Myocardial Ischemia |

| NF-kB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light Chain Enhancer of Activated B cells |

| NLRs | Nucleotide-Binding Domain and Leucine-Rich Repeat Containing Receptors |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| oxLDL | Oxidized Lipoproteins |

| Phosphodiesterase (PDE) | |

| PG | Prostaglandin |

| PGI2 | Prostacyclin-I 2 |

| PRR | Pattern Recognition Receptors |

| PVAs | Hydroxy-Phenyl-Valeric Acids |

| PVLs | Hydroxy-Phenyl-Gamma-Valerolactones |

| RES | Resveratrol |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| SGLT1 | Sodium-Glucose-Linked Transporter 1 |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| TXA | Thromboxane |

| TMAO | Trimethyl-Amine-Oxide |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| VCM | Vascular Cell Adhesion-1 |

References

- Laslett, L.J.; Alagona, P., Jr.; Clark, B.A., 3rd; Drozda, J.P., Jr.; Saldivar, F.; Wilson, S.R.; Poe, C.; Hart, M. The worldwide environment of cardiovascular disease: prevalence, diagnosis, therapy, and policy issues: a report from the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012, 60, S1–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Force, U.S.P.S.T.; Curry, S.J.; Krist, A.H.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kemper, A.R.; et al. Risk Assessment for Cardiovascular Disease With Nontraditional Risk Factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 320, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, J.W.; Ashley, E.A. Cardiovascular disease: The rise of the genetic risk score. PLoS Med 2018, 15, e1002546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Millican, R.; Sherwood, J.; Martin, S.; Jo, H.; Yoon, Y.S.; Brott, B.C.; Jun, H.W. Recent advances in nanomaterials for therapy and diagnosis for atherosclerosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 170, 142–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Kuntic, M.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Helmstadter, J.; Kroller-Schon, S.; Munzel, T.; et al. Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Major Triggers for Cardiovascular Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 7092151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liao, R.; Zhang, S.; Weng, H.; Liu, Y.; Tao, T.; Yu, F.; Li, G.; Wu, J. Promising remedies for cardiovascular disease: Natural polyphenol ellagic acid and its metabolite urolithins. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiati, C.; Stanca, A.; Lepera, M.E. Free Radicals and Obesity-Related Chronic Inflammation Contrasted by Antioxidants: A New Perspective in Coronary Artery Disease. Metabolites 2023, 13, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, A.; Naz, R.; Mubarak, M.S. Plant Polyphenols and Their Potential Benefits on Cardiovascular Health: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelman, L.; Egea Rodrigues, C.; Aleksandrova, K. Effects of Dietary Patterns on Biomarkers of Inflammation and Immune Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv Nutr 2022, 13, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisco, G.; Giagulli, V.A.; De Pergola, G.; Guastamacchia, E.; Jirillo, E.; Triggiani, V. Pancreatic Macrophages and their Diabetogenic Effects: Highlight on Several Metabolic Scenarios and Dietary Approach. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2023, 23, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldati, L.; Di Renzo, L.; Jirillo, E.; Ascierto, P.A.; Marincola, F.M.; De Lorenzo, A. The influence of diet on anti-cancer immune responsiveness. J Transl Med 2018, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Arellano, A.; Ramallal, R.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Corella, D.; Shivappa, N.; Schroder, H.; Hebert, J.R.; Ros, E.; Gomez-Garcia, E.; et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease in the PREDIMED Study. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4124–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlani, Y.; Pothineni, N.V.; Kovelamudi, S.; Mehta, J.L. Metabolic syndrome: pathophysiology, management, and modulation by natural compounds. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2017, 11, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, W.; van Bilsen, J.; Salic, K.; Hoevenaars, F.P.M.; Verschuren, L.; Kleemann, R.; Bouwman, J.; Ronnett, G.V.; van Ommen, B.; Wopereis, S. Current and Future Nutritional Strategies to Modulate Inflammatory Dynamics in Metabolic Disorders. Front Nutr 2019, 6, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quideau, S.; Deffieux, D.; Douat-Casassus, C.; Pouysegu, L. Plant polyphenols: chemical properties, biological activities, and synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2011, 50, 586–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrone, T.; Magrone, M.; Russo, M.A.; Jirillo, E. Recent Advances on the Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Red Grape Polyphenols: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serreli, G.; Boronat, A.; De la Torre, R.; Rodriguez-Morato, J.; Deiana, M. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds: Mechanistic Insights from In Vivo Studies. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Valdivieso, C.; Briones, F.; Orellana-Urzua, S.; Chichiarelli, S.; Saso, L.; Rodrigo, R. Novel Multi-Antioxidant Approach for Ischemic Stroke Therapy Targeting the Role of Oxidative Stress. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Ferri, R.; Lanza, G.; Caraci, F.; Vistorte, A.O.R.; Yelamos Torres, V.; Grosso, G.; Castellano, S. Mediterranean Diet and Sleep Features: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriantsitohaina, R.; Auger, C.; Chataigneau, T.; Etienne-Selloum, N.; Li, H.; Martinez, M.C.; Schini-Kerth, V.B.; Laher, I. Molecular mechanisms of the cardiovascular protective effects of polyphenols. Br J Nutr 2012, 108, 1532–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Williamson, G.; Morand, C.; Scalbert, A.; Remesy, C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 81, 230S–242S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.L.; Zahradka, P.; Taylor, C.G. Efficacy of flavonoids in the management of high blood pressure. Nutr Rev 2015, 73, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crozier, A.; Del Rio, D.; Clifford, M.N. Bioavailability of dietary flavonoids and phenolic compounds. Mol Aspects Med 2010, 31, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovina, A.S.; Kiselev, K.V. Regulation of stilbene biosynthesis in plants. Planta 2017, 246, 597–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyagbemi, A.A.; Omobowale, T.O.; Ola-Davies, O.E.; Asenuga, E.R.; Ajibade, T.O.; Adejumobi, O.A.; Arojojoye, O.A.; Afolabi, J.M.; Ogunpolu, B.S.; Falayi, O.O.; et al. Quercetin attenuates hypertension induced by sodium fluoride via reduction in oxidative stress and modulation of HSP 70/ERK/PPARgamma signaling pathways. Biofactors 2018, 44, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.M.; Hernandez Bautista, R.J.; Sandhu, M.A.; Hussein, O.E. Beneficial Effects of Citrus Flavonoids on Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 5484138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal, R.; Halmosi, R.; Gallyas, F., Jr.; Tschida, M.; Mutirangura, P.; Toth, K.; Alexy, T.; Czopf, L. Resveratrol and beyond: The Effect of Natural Polyphenols on the Cardiovascular System: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T. Bioavailability of Non-Provitamin A Carotenoids. Curr Nutr Food Sci 2008, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.J.; Canada, F.J.; Diaz, J.C.; Kroon, P.A.; McLauchlan, R.; Faulds, C.B.; Plumb, G.W.; Morgan, M.R.; Williamson, G. Dietary flavonoid and isoflavone glycosides are hydrolysed by the lactase site of lactase phlorizin hydrolase. FEBS Lett 2000, 468, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinska, A.; Andlauer, W. Cocoa polyphenols are absorbed in Caco-2 cell model of intestinal epithelium. Food Chem 2012, 135, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry-Vitrac, C.; Desmouliere, A.; Girard, D.; Merillon, J.M.; Krisa, S. Transport, deglycosylation, and metabolism of trans-piceid by small intestinal epithelial cells. Eur J Nutr 2006, 45, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, B.; Schneider, H.P.; Broer, A.; Deitmer, J.W.; Broer, S. Helix 8 and helix 10 are involved in substrate recognition in the rat monocarboxylate transporter MCT1. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 11577–11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konishi, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Shimizu, M. Transepithelial transport of p-coumaric acid and gallic acid in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2003, 67, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selma, M.V.; Espin, J.C.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A. Interaction between phenolics and gut microbiota: role in human health. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 6485–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonarduzzi, G.; Testa, G.; Sottero, B.; Gamba, P.; Poli, G. Design and development of nanovehicle-based delivery systems for preventive or therapeutic supplementation with flavonoids. Curr Med Chem 2010, 17, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.D.; Sang, S.; Yang, C.S. Biotransformation of green tea polyphenols and the biological activities of those metabolites. Mol Pharm 2007, 4, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Blackwood, M.; Francis, D.; Tian, Q.; Schwartz, S.J.; Clinton, S.K. Bioavailability of phytochemical constituents from a novel soy fortified lycopene rich tomato juice developed for targeted cancer prevention trials. Nutr Cancer 2013, 65, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahkonen, M.P.; Heinonen, M. Antioxidant activity of anthocyanins and their aglycons. J Agric Food Chem 2003, 51, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Damage, and Antioxidative Defense Mechanism in Plants under Stressful Conditions. Journal of Botany 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinsky, N.I. Mechanism of action of biological antioxidants. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1992, 200, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, J.D.; Mallet, A.I.; McAnlis, G.T.; Young, I.S.; Halliwell, B.; Sanders, T.A.; Wiseman, H. Consumption of flavonoids in onions and black tea: lack of effect on F2-isoprostanes and autoantibodies to oxidized LDL in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2001, 73, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, S.E.; Kuhnle, G.G.; Vauzour, D.; Vafeiadou, K.; Tzounis, X.; Whiteman, M.; Rice-Evans, C.; Spencer, J.P. The reaction of flavonoid metabolites with peroxynitrite. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 350, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotito, S.B.; Frei, B. The increase in human plasma antioxidant capacity after apple consumption is due to the metabolic effect of fructose on urate, not apple-derived antioxidant flavonoids. Free Radic Biol Med 2004, 37, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cines, D.B.; Pollak, E.S.; Buck, C.A.; Loscalzo, J.; Zimmerman, G.A.; McEver, R.P.; Pober, J.S.; Wick, T.M.; Konkle, B.A.; Schwartz, B.S.; et al. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood 1998, 91, 3527–3561. [Google Scholar]

- Sanches-Silva, A.; Testai, L.; Nabavi, S.F.; Battino, M.; Pandima Devi, K.; Tejada, S.; Sureda, A.; Xu, S.; Yousefi, B.; Majidinia, M.; et al. Therapeutic potential of polyphenols in cardiovascular diseases: Regulation of mTOR signaling pathway. Pharmacol Res 2020, 152, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Andriambeloson, E.; Diebolt, M.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Wine polyphenols stimulate superoxide anion production to promote calcium signaling and endothelial-dependent vasodilatation. Physiol Res 2004, 53, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Ouchi, Y.; Hosoda, K.; Nozawa, M.; Kinoshita, M. Effect of red wine and ethanol on production of nitric oxide in healthy subjects. The American journal of cardiology 2001, 87, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.F.; Chen, S.A.; Wu, S.N. Evidence for the stimulatory effect of resveratrol on Ca(2+)-activated K+ current in vascular endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 2000, 45, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriambeloson, E.; Stoclet, J.C.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Mechanism of endothelial nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation induced by wine polyphenols in rat thoracic aorta. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology 1999, 33, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Andriambeloson, E.; Takeda, K.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Red wine polyphenols increase calcium in bovine aortic endothelial cells: a basis to elucidate signalling pathways leading to nitric oxide production. Br J Pharmacol 2002, 135, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, D.D.; Wang, J.F.; Holt, R.R.; Ensunsa, J.L.; Gonsalves, J.L.; Lazarus, S.A.; Schmitz, H.H.; German, J.B.; Keen, C.L. Chocolate procyanidins decrease the leukotriene-prostacyclin ratio in humans and human aortic endothelial cells. Am J Clin Nutr 2001, 73, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndiaye, M.; Chataigneau, M.; Lobysheva, I.; Chataigneau, T.; Schini-Kerth, V.B. Red wine polyphenol-induced, endothelium-dependent NO-mediated relaxation is due to the redox-sensitive PI3-kinase/Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial NO-synthase in the isolated porcine coronary artery. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2005, 19, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Conklin, B.S.; Lin, P.H.; Lumsden, A.B.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Red wine prevents homocysteine-induced endothelial dysfunction in porcine coronary arteries. J Surg Res 2003, 115, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugnier, C.; Schini, V.B. Characterization of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases from cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol 1990, 39, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrone, T.; Jirillo, E. Potential application of dietary polyphenols from red wine to attaining healthy ageing. Curr Top Med Chem 2011, 11, 1780–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrone, T.; Jirillo, E. Polyphenols from red wine are potent modulators of innate and adaptive immune responsiveness. Proc Nutr Soc 2010, 69, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzulli, G.; Magrone, T.; Kawaguchi, K.; Kumazawa, Y.; Jirillo, E. Fermented grape marc (FGM): immunomodulating properties and its potential exploitation in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Pharm Des 2012, 18, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzulli, G.; Magrone, T.; Vonghia, L.; Kaneko, M.; Takimoto, H.; Kumazawa, Y.; Jirillo, E. Immunomodulating and anti-allergic effects of Negroamaro and Koshu Vitis vinifera fermented grape marc (FGM). Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sahana, G.R.; Nagella, P.; Joseph, B.V.; Alessa, F.M.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q. Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauth, V.; Bruno, F.; Pace, S.; Jordan, P.M.; Temml, V.; Preziosa Romano, M.; Khan, H.; Schuster, D.; Rossi, A.; Filosa, R.; et al. Highly potent and selective 5-lipoxygenase inhibition by new, simple heteroaryl-substituted catechols for treatment of inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol 2023, 208, 115385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, F.; Burns, K.; Tschopp, J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell 2002, 10, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidt, M.M.; Hornung, V. Pore formation by GSDMD is the effector mechanism of pyroptosis. EMBO J 2016, 35, 2167–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zeng, X.; Li, X.; Mehta, J.L.; Wang, X. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. Basic Res Cardiol 2018, 113, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalva, M.; Martinez-Garcia, J.J.; Jaime, L.; Santoyo, S.; Pelegrin, P.; Perez-Jimenez, J. Polyphenols as NLRP3 inflammasome modulators in cardiometabolic diseases: a review of in vivo studies. Food Funct 2023, 14, 9534–9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Gu, X.; Wang, H.; Ding, S. Resveratrol improves cardiac function and left ventricular fibrosis after myocardial infarction in rats by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activity and the TGF-beta1/SMAD2 signaling pathway. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Mou, S.Q.; Li, W.J.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Ding, W.; Bian, Z.Y.; Liao, H.H. Resveratrol Inhibits Ischemia-Induced Myocardial Senescence Signals and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 2647807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Cheng, X.; Tang, L.; Jiang, M. The cardioprotective effect of total flavonoids on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 88, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; RuXian, G. Didymin, a natural flavonoid, relieves the progression of myocardial infarction via inhibiting the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome. Pharm Biol 2022, 60, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiati, C.; Pollice, P.; Favale, S.; Lepera, M.E. The Herbicide Glyphosate and Its Apparently Controversial Effect on Human Health: An Updated Clinical Perspective. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2020, 20, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, P.N. Molecular biology of atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev 2013, 93, 1317–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caiati, C. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Reveals That Lipoprotein Apheresis Improves Myocardial But Not Skeletal Muscle Perfusion. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, 1441–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, K.L.; Ornish, D.; Scherwitz, L.; Brown, S.; Edens, R.P.; Hess, M.J.; Mullani, N.; Bolomey, L.; Dobbs, F.; Armstrong, W.T.; et al. Changes in myocardial perfusion abnormalities by positron emission tomography after long-term, intense risk factor modification. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1995, 274, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiati, C.; Iacovelli, F.; Mancini, G.; Lepera, M.E. Hidden Coronary Atherosclerosis Assessment but Not Coronary Flow Reserve Helps to Explain the Slow Coronary Flow Phenomenon in Patients with Angiographically Normal Coronary Arteries. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, G.K.; Libby, P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol 2006, 6, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.B.; Mengi, S.A.; Xu, Y.J.; Arneja, A.S.; Dhalla, N.S. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: A multifactorial process. Exp Clin Cardiol 2002, 7, 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Harrison, D.G. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res 2000, 87, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.K. Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2009, 102, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furie, B.; Furie, B.C. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. N Engl J Med 2008, 359, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.N.; Chen, Y.L.; Chen, Y.T.; Ding, Y.Z.; Lin, S.J. Red wine inhibits monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression and modestly reduces neointimal hyperplasia after balloon injury in cholesterol-Fed rabbits. Circulation 1999, 100, 2254–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Żuchowski, J.; Stochmal, A.; Olas, B. Quercetin and kaempferol derivatives isolated from aerial parts of Lens culinaris Medik as modulators of blood platelet functions. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 152, 112536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.H.; Keevil, J.G.; Wiebe, D.A.; Aeschlimann, S.; Folts, J.D. Purple grape juice improves endothelial function and reduces the susceptibility of LDL cholesterol to oxidation in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 1999, 100, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhrman, B.; Lavy, A.; Aviram, M. Consumption of red wine with meals reduces the susceptibility of human plasma and low-density lipoprotein to lipid peroxidation. Am J Clin Nutr 1995, 61, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciumarnean, L.; Milaciu, M.V.; Runcan, O.; Vesa, S.C.; Rachisan, A.L.; Negrean, V.; Perne, M.G.; Donca, V.I.; Alexescu, T.G.; Para, I.; et al. The Effects of Flavonoids in Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornish, D.; Brown, S.E.; Scherwitz, L.W.; Billings, J.H.; Armstrong, W.T.; Ports, T.A.; McLanahan, S.M.; Kirkeeide, R.L.; Brand, R.J.; Gould, K.L. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet 1990, 336, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, P.; Santos, C.N. Worldwide (poly)phenol intake: assessment methods and identified gaps. Eur J Nutr 2017, 56, 1393–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.Y.; Sang, L.X.; Jiang, M. Catechins and Their Therapeutic Benefits to Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ramiro, I.; Martin, M.A.; Ramos, S.; Bravo, L.; Goya, L. Comparative effects of dietary flavanols on antioxidant defences and their response to oxidant-induced stress on Caco2 cells. Eur J Nutr 2011, 50, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.G.; Katiyar, S.K.; Agarwal, R.; Mukhtar, H. Enhancement of antioxidant and phase II enzymes by oral feeding of green tea polyphenols in drinking water to SKH-1 hairless mice: possible role in cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Res 1992, 52, 4050–4052. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskovska, T.; Massaro, M.; Carluccio, M.A.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Muguerza, B.; Vanden Berghe, W.; Declerck, K.; Bravo, F.I.; Calabriso, N.; Combet, E.; et al. Systematic bioinformatic analysis of nutrigenomic data of flavanols in cell models of cardiometabolic disease. Food Funct 2020, 11, 5040–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Vitale, M.; Micek, A.; Ray, S.; Martini, D.; Del Rio, D.; Riccardi, G.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Dietary Polyphenol Intake, Blood Pressure, and Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleaga, C.; Ciudad, C.J.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M.; Noe, V. Cocoa flavanol metabolites activate HNF-3beta, Sp1, and NFY-mediated transcription of apolipoprotein AI in human cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2013, 57, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, P.; Bresciani, L.; Brindani, N.; Ludwig, I.A.; Pereira-Caro, G.; Angelino, D.; Llorach, R.; Calani, L.; Brighenti, F.; Clifford, M.N.; et al. Phenyl-gamma-valerolactones and phenylvaleric acids, the main colonic metabolites of flavan-3-ols: synthesis, analysis, bioavailability, and bioactivity. Nat Prod Rep 2019, 36, 714–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.C.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Oh, Y.S.; Han, S.M.; Park, J.H.Y.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, C.Y. 5-(3',4'-Dihydroxyphenyl-gamma-valerolactone), a Major Microbial Metabolite of Proanthocyanidin, Attenuates THP-1 Monocyte-Endothelial Adhesion. International journal of molecular sciences 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, N.; Dua, T.K.; Khanra, R.; Joardar, S.; Nandy, A.; Saha, A.; De Feo, V.; Dewanjee, S. Protocatechuic Acid, a Phenolic from Sansevieria roxburghiana Leaves, Suppresses Diabetic Cardiomyopathy via Stimulating Glucose Metabolism, Ameliorating Oxidative Stress, and Inhibiting Inflammation. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Islam, F.; Or-Rashid, M.H.; Mamun, A.A.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.M.; Meem, A.F.K.; Sutradhar, P.R.; Mitra, S.; Mimi, A.A.; et al. The Gut Microbiota (Microbiome) in Cardiovascular Disease and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 903570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cordero, J.; Mateos, R.; Gonzalez-Ramila, S.; Seguido, M.A.; Sierra-Cinos, J.L.; Sarria, B.; Bravo, L. Dietary Supplements Containing Oat Beta-Glucan and/or Green Coffee (Poly)phenols Showed Limited Effect in Modulating Cardiometabolic Risk Biomarkers in Overweight/Obese Patients without a Lifestyle Intervention. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, D.; Necozione, S.; Lippi, C.; Croce, G.; Valeri, L.; Pasqualetti, P.; Desideri, G.; Blumberg, J.B.; Ferri, C. Cocoa reduces blood pressure and insulin resistance and improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypertensives. Hypertension 2005, 46, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, D.; Desideri, G.; Necozione, S.; Lippi, C.; Casale, R.; Properzi, G.; Blumberg, J.B.; Ferri, C. Blood pressure is reduced and insulin sensitivity increased in glucose-intolerant, hypertensive subjects after 15 days of consuming high-polyphenol dark chocolate. J Nutr 2008, 138, 1671–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiss, C.; Jahn, S.; Taylor, M.; Real, W.M.; Angeli, F.S.; Wong, M.L.; Amabile, N.; Prasad, M.; Rassaf, T.; Ottaviani, J.I.; et al. Improvement of endothelial function with dietary flavanols is associated with mobilization of circulating angiogenic cells in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010, 56, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, A.J.; Sudano, I.; Wolfrum, M.; Thomas, R.; Enseleit, F.; Periat, D.; Kaiser, P.; Hirt, A.; Hermann, M.; Serafini, M.; et al. Cardiovascular effects of flavanol-rich chocolate in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J 2012, 33, 2172–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nantz, M.P.; Rowe, C.A.; Bukowski, J.F.; Percival, S.S. Standardized capsule of Camellia sinensis lowers cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrition 2009, 25, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafeshani, M.; Entezari, M.H.; Karimian, J.; Pourmasoumi, M.; Maracy, M.R.; Amini, M.R.; Hadi, A. A comparative study of the effect of green tea and sour tea on blood pressure and lipid profile in healthy adult men. ARYA Atheroscler 2017, 13, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M.; Miyashita, M.; Suzuki, K.; Bae, S.R.; Kim, H.K.; Wakisaka, T.; Matsui, Y.; Takeshita, M.; Yasunaga, K. Acute ingestion of catechin-rich green tea improves postprandial glucose status and increases serum thioredoxin concentrations in postmenopausal women. Br J Nutr 2014, 112, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diepvens, K.; Kovacs, E.M.; Nijs, I.M.; Vogels, N.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Effect of green tea on resting energy expenditure and substrate oxidation during weight loss in overweight females. Br J Nutr 2005, 94, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.; George, T.W.; Lodge, J.K.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.M.; Spencer, J.P.; Minihane, A.M.; Rimbach, G. Daily consumption of an aqueous green tea extract supplement does not impair liver function or alter cardiovascular disease risk biomarkers in healthy men. J Nutr 2009, 139, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, R.; Kotani, K.; Ayabe, M.; Tsuzaki, K.; Shimada, J.; Sakane, N.; Takase, H.; Ichikawa, H.; Yonei, Y.; Ishii, K. Minor effects of green tea catechin supplementation on cardiovascular risk markers in active older people: a randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013, 13, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Daiber, A.; Forstermann, U.; Li, H. Antioxidant effects of resveratrol in the cardiovascular system. Br J Pharmacol 2017, 174, 1633–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagul, P.K.; Deepthi, N.; Sultana, R.; Banerjee, S.K. Resveratrol ameliorates cardiac oxidative stress in diabetes through deacetylation of NFkB-p65 and histone 3. J Nutr Biochem 2015, 26, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, G.; Xu, H.; Xia, N.; Tobias, S.; Deng, S.; Wojnowski, L.; Forstermann, U.; Li, H. Resveratrol reduces endothelial oxidative stress by modulating the gene expression of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1) and NADPH oxidase subunit (Nox4). J Physiol Pharmacol 2009, 60 Suppl 4, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, N.; Daiber, A.; Habermeier, A.; Closs, E.I.; Thum, T.; Spanier, G.; Lu, Q.; Oelze, M.; Torzewski, M.; Lackner, K.J.; et al. Resveratrol reverses endothelial nitric-oxide synthase uncoupling in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2010, 335, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Guo, T.; Li, G.; Sun, S.; He, S.; Cheng, B.; Shi, B.; Shan, A. Dietary resveratrol improves antioxidant status of sows and piglets and regulates antioxidant gene expression in placenta by Keap1-Nrf2 pathway and Sirt1. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2018, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, F.; Hoberg, J.E.; Ramsey, C.S.; Keller, M.D.; Jones, D.R.; Frye, R.A.; Mayo, M.W. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J 2004, 23, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, F.; Song, G.; Xu, H.; Wan, T.; et al. Resveratrol reduces the proinflammatory effects and lipopolysaccharide- induced expression of HMGB1 and TLR4 in RAW264.7 cells. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 2014, 33, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, W.; Qiu, Q.; Peng, J. Resveratrol prevents TNF-alpha-induced VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 upregulation in endothelial progenitor cells via reduction of NF-kappaB activation. J Int Med Res 2020, 48, 300060520945131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Xiao, D.; Muhammed, A.; Deng, J.; Chen, L.; He, J. Anti-Inflammatory Action and Mechanisms of Resveratrol. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, R.; Deres, L.; Horvath, O.; Eros, K.; Sandor, B.; Urban, P.; Soos, S.; Marton, Z.; Sumegi, B.; Toth, K.; et al. Resveratrol Improves Heart Function by Moderating Inflammatory Processes in Patients with Systolic Heart Failure. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslin, A.J. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008, 115, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondoh, K.; Nishida, E. Regulation of MAP kinases by MAP kinase phosphatases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007, 1773, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Yan, J.; Cheng, M.; Zhao, R.; Chen, L.; Hu, C.; Jia, W. Resveratrol reduces intracellular reactive oxygen species levels by inducing autophagy through the AMPK-mTOR pathway. Front Med 2018, 12, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Ong'achwa, M.J.; Ge, L.; Qian, Y.; Chen, L.; Hu, X.; Li, F.; Wei, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Resveratrol Inhibits the TGF-beta1-Induced Proliferation of Cardiac Fibroblasts and Collagen Secretion by Downregulating miR-17 in Rat. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018, 8730593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsamanesh, N.; Asghari, A.; Sardari, S.; Tasbandi, A.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Xu, S.; Sahebkar, A. Resveratrol and endothelial function: A literature review. Pharmacol Res 2021, 170, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstermann, U.; Xia, N.; Li, H. Roles of Vascular Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2017, 120, 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Feng, J.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J.; Han, D.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Li, X.; Fan, M.; Li, C.; et al. SIRT1 Activation by Resveratrol Alleviates Cardiac Dysfunction via Mitochondrial Regulation in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 4602715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodotou, M.; Fokianos, K.; Mouzouridou, A.; Konstantinou, C.; Aristotelous, A.; Prodromou, D.; Chrysikou, A. The effect of resveratrol on hypertension: A clinical trial. Exp Ther Med 2017, 13, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, P.; He, S.; Huang, D. Effect of resveratrol on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 2015, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.M.; Eckardt, P.; Aleman, J.O.; da Rosa, J.C.; Liang, Y.; Iizumi, T.; Etheve, S.; Blaser, M.J.; J, L.B.; Holt, P.R. The effects of trans-resveratrol on insulin resistance, inflammation, and microbiota in men with the metabolic syndrome: A pilot randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Transl Res 2019, 4, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, R.H.; Howe, P.R.; Buckley, J.D.; Coates, A.M.; Kunz, I.; Berry, N.M. Acute resveratrol supplementation improves flow-mediated dilatation in overweight/obese individuals with mildly elevated blood pressure. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011, 21, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magyar, K.; Halmosi, R.; Palfi, A.; Feher, G.; Czopf, L.; Fulop, A.; Battyany, I.; Sumegi, B.; Toth, K.; Szabados, E. Cardioprotection by resveratrol: A human clinical trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2012, 50, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujitaka, K.; Otani, H.; Jo, F.; Jo, H.; Nomura, E.; Iwasaki, M.; Nishikawa, M.; Iwasaka, T.; Das, D.K. Modified resveratrol Longevinex improves endothelial function in adults with metabolic syndrome receiving standard treatment. Nutr Res 2011, 31, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, B.; Trindade, M.; Aquino, J.C.F.; Cunha, A.R.; Gismondi, R.O.; Neves, M.F.; Oigman, W. Beneficial effects of acute trans-resveratrol supplementation in treated hypertensive patients with endothelial dysfunction. Clin Exp Hypertens 2018, 40, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgary, S.; Karimi, R.; Momtaz, S.; Naseri, R.; Farzaei, M.H. Effect of resveratrol on metabolic syndrome components: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2019, 20, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, A.; Namazi, G.; Farrokhian, A.; Reiner, Z.; Aghadavod, E.; Bahmani, F.; Asemi, Z. The effects of resveratrol on metabolic status in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease. Food Funct 2019, 10, 6042–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendia, L.E.; Guerrero-Romero, F. Effect of resveratrol supplementation on lipid profile in subjects with dyslipidemia: A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition 2019, 58, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Militaru, C.; Donoiu, I.; Craciun, A.; Scorei, I.D.; Bulearca, A.M.; Scorei, R.I. Oral resveratrol and calcium fructoborate supplementation in subjects with stable angina pectoris: effects on lipid profiles, inflammation markers, and quality of life. Nutrition 2013, 29, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin as "Curecumin": from kitchen to clinic. Biochem Pharmacol 2008, 75, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, M.L.; Parihar, P.; Solanki, I.; Parihar, M.S. Flavonoids in modulation of cell survival signalling pathways. Genes Nutr 2014, 9, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukongviriyapan, U.; Pannangpetch, P.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Donpunha, W.; Sompamit, K.; Surawattanawan, P. Curcumin protects against cadmium-induced vascular dysfunction, hypertension and tissue cadmium accumulation in mice. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubsakul, A.; Sangartit, W.; Pakdeechote, P.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Apaijit, K.; Kukongviriyapan, U. Curcumin Mitigates Hypertension, Endothelial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Rats with Chronic Exposure to Lead and Cadmium. Tohoku J Exp Med 2021, 253, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, T.; Xie, J.; Wang, S.; He, Y.; Zhu, F. Curcumin modulates covalent histone modification and TIMP1 gene activation to protect against vascular injury in a hypertension rat model. Exp Ther Med 2017, 14, 5896–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Ren, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.E.; Yang, J.; Zeng, C. Curcumin Exerts its Anti-hypertensive Effect by Down-regulating the AT1 Receptor in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 25579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birudaraju, D.; Cherukuri, L.; Kinninger, A.; Chaganti, B.T.; Shaikh, K.; Hamal, S.; Flores, F.; Roy, S.K.; Budoff, M.J. A combined effect of Cavacurcumin, Eicosapentaenoic acid (Omega-3s), Astaxanthin and Gamma -linoleic acid (Omega-6) (CEAG) in healthy volunteers- a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020, 35, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehdehi, P.; Zanjaninejad, B.; Aflaki, E.; Nazarinia, M.; Azad, F.; Malekmakan, L.; Dehghanzadeh, G.R. Oral supplementation of turmeric decreases proteinuria, hematuria, and systolic blood pressure in patients suffering from relapsing or refractory lupus nephritis: a randomized and placebo-controlled study. J Ren Nutr 2012, 22, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.S.; Fleenor, B.S. The emerging role of curcumin for improving vascular dysfunction: A review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2018, 58, 2790–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Parker, J.R.; Strahler, T.R.; Bassett, C.J.; Bispham, N.Z.; Chonchol, M.B.; Seals, D.R. Curcumin supplementation improves vascular endothelial function in healthy middle-aged and older adults by increasing nitric oxide bioavailability and reducing oxidative stress. Aging (Albany NY) 2017, 9, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Si, H. Synergistic anti-inflammatory effects and mechanisms of the combination of resveratrol and curcumin in human vascular endothelial cells and rodent aorta. J Nutr Biochem 2022, 108, 109083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenco-Lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive Compounds and Quality of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicerale, S.; Conlan, X.A.; Sinclair, A.J.; Keast, R.S. Chemistry and health of olive oil phenolics. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2009, 49, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finicelli, M.; Squillaro, T.; Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G. Polyphenols, the Healthy Brand of Olive Oil: Insights and Perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Correa, J.A.; Navas, M.D.; Munoz-Marin, J.; Trujillo, M.; Fernandez-Bolanos, J.; de la Cruz, J.P. Effects of hydroxytyrosol and hydroxytyrosol acetate administration to rats on platelet function compared to acetylsalicylic acid. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 7872–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz-Marin, J.; De la Cruz, J.P.; Reyes, J.J.; Lopez-Villodres, J.A.; Guerrero, A.; Lopez-Leiva, I.; Espartero, J.L.; Labajos, M.T.; Gonzalez-Correa, J.A. Hydroxytyrosyl alkyl ether derivatives inhibit platelet activation after oral administration to rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2013, 58, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Di Micoli, A.; Veronesi, M.; Grandi, E.; Borghi, C. Hydroxytyrosol-Rich Olive Extract for Plasma Cholesterol Control. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Addato, S.; Scandiani, L.; Mombelli, G.; Focanti, F.; Pelacchi, F.; Salvatori, E.; Di Loreto, G.; Comandini, A.; Maffioli, P.; Derosa, G. Effect of a food supplement containing berberine, monacolin K, hydroxytyrosol and coenzyme Q(10) on lipid levels: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017, 11, 1585–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros-Fernandez, R.; Lopez-Plaza, B.; Bermejo, L.M.; Palma Milla, S.; Zangara, A.; Candela, C.G. Oral Supplement Containing Hydroxytyrosol and Punicalagin Improves Dyslipidemia in an Adult Population without Co-Adjuvant Treatment: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled and Crossover Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colica, C.; Di Renzo, L.; Trombetta, D.; Smeriglio, A.; Bernardini, S.; Cioccoloni, G.; Costa de Miranda, R.; Gualtieri, P.; Sinibaldi Salimei, P.; De Lorenzo, A. Antioxidant Effects of a Hydroxytyrosol-Based Pharmaceutical Formulation on Body Composition, Metabolic State, and Gene Expression: A Randomized Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 2473495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Huertas, E.; Fonolla, J. Hydroxytyrosol supplementation increases vitamin C levels in vivo. A human volunteer trial. Redox Biol 2017, 11, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, A.; Alvarez-Soria, M.J.; Aranda-Villalobos, P.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.M.; Martinez-Lara, E.; Siles, E. Hydroxytyrosol, a Promising Supplement in the Management of Human Stroke: An Exploratory Study. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Baenziger, P.S.; Frels, K. Emerging Trends in Wheat (Triticum spp.) Breeding: Implications for the Future. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2024, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laddomada, B.; Caretto, S.; Mita, G. Wheat Bran Phenolic Acids: Bioavailability and Stability in Whole Wheat-Based Foods. Molecules 2015, 20, 15666–15685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sun, X.Y.; Mariga, A.M.; Yang, Q.; Fang, Y.; Hu, Q.H.; Pei, F. Effects of ferulic acid on the polymerization behavior of gluten protein and its components. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabriso, N.; Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Pasqualone, A.; Laddomada, B.; Carluccio, M.A. Phenolic extracts from whole wheat biofortified bread dampen overwhelming inflammatory response in human endothelial cells and monocytes: major role of VCAM-1 and CXCL-10. Eur J Nutr 2020, 59, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costabile, G.; Vitale, M.; Della Pepa, G.; Cipriano, P.; Vetrani, C.; Testa, R.; Mena, P.; Bresciani, L.; Tassotti, M.; Calani, L.; et al. A wheat aleurone-rich diet improves oxidative stress but does not influence glucose metabolism in overweight/obese individuals: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2022, 32, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-Lopez, N.J.; Astiazaran-Garcia, H.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Loarca-Pina, G.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M.; Dominguez Avila, J.A.; Robles-Sanchez, M. Ferulic Acid on Glucose Dysregulation, Dyslipidemia, and Inflammation in Diet-Induced Obese Rats: An Integrated Study. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.L.; Zhao, C.H.; Yao, X.L.; Zhang, H. Quercetin attenuates high fructose feeding-induced atherosclerosis by suppressing inflammation and apoptosis via ROS-regulated PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 85, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Jia, Q.; Shen, D.; Yan, L.; Chen, C.; Xing, S. Quercetin has a protective effect on atherosclerosis via enhancement of autophagy in ApoE(-/-) mice. Exp Ther Med 2019, 18, 2451–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Izawa-Ishizawa, Y.; Goda, M.; Hosooka, M.; Kagimoto, Y.; Saito, N.; Matsuoka, R.; Zamami, Y.; Chuma, M.; Yagi, K.; et al. Preventive Effects of Quercetin against the Onset of Atherosclerosis-Related Acute Aortic Syndromes in Mice. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenczyova, K.; Kalocayova, B.; Bartekova, M. Potential Implications of Quercetin and its Derivatives in Cardioprotection. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.A.; Patel, K.R.; Viskaduraki, M.; Crowell, J.A.; Perloff, M.; Booth, T.D.; Vasilinin, G.; Sen, A.; Schinas, A.M.; Piccirilli, G.; et al. Repeat dose study of the cancer chemopreventive agent resveratrol in healthy volunteers: safety, pharmacokinetics, and effect on the insulin-like growth factor axis. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 9003–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Porte, C.; Voduc, N.; Zhang, G.; Seguin, I.; Tardiff, D.; Singhal, N.; Cameron, D.W. Steady-State pharmacokinetics and tolerability of trans-resveratrol 2000 mg twice daily with food, quercetin and alcohol (ethanol) in healthy human subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet 2010, 49, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, J.A.; Korytko, P.J.; Morrissey, R.L.; Booth, T.D.; Levine, B.S. Resveratrol-associated renal toxicity. Toxicol Sci 2004, 82, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Webster, D.; Cao, J.; Shao, A. The safety of green tea and green tea extract consumption in adults - Results of a systematic review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2018, 95, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Correa, M.; Shoskes, D.A.; Sanchez, P.; Zhao, R.; Hylind, L.M.; Wexner, S.D.; Giardiello, F.M. Combination treatment with curcumin and quercetin of adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006, 4, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, R.; Egli, I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 91, 1461S–1467S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1.1 Scavenging activity depends on the donation of an electron or H atom from a hydroxyl group to afree radical [42] |

| 1.2 A catechol group in the structure of polyphenols is associated with antioxidant activity[39] |

| 1.3 The phenolic core of quercetin and catechin scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS), acting as a buffer or collecting electrons[40] |

| 1.4 Polyphenols inhibit enzymes, such as xanthine oxidase and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphatase, thus, reducing the generation of ROS [41] |

| 1.5 Quercetin exhibits the best capacity to chelate metal ions[117] |

| 2.1 Polyphenol-induced nitric oxide (NO) generation from endothelial cells and monocytes contributes to artery vasodilation[16,46,47] |

| 2.2 In rats, ingestion of red wine polyphenols generates hypotension through activation of inducible NO synthase, cyclooxygenase-2, and calcium ion-dependent pathway in the arteries[49,50] |

| 2.3 Red wine polyphenols trigger endothelial NO production via the PI3/Akt pathway, the increase in intracellular protein-Ca2+, and tyrosine phosphorylation[51,52] |

| 2.4 Cocoa extracts rich in procyanidins cause vasodilation via increased release of prostacyclin I2[53] |

| 2.5 Polyphenols increase endothelial NO by decreasing phosphodiesterase (PDE)-2, and PDE-4[54] |

| 3.1 Red wine polyphenols reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, inhibiting the NF-kB pathway, and/or activating T regulatory cells, with release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin (IL)-10[16,57] |

| 3.2 Fermented grape marc reduces the respiratory burst of human neutrophils, and basophils[58] |

| 3.3 Quercetin decreases the release of IL-1 beta, and IL-8, abrogating the generation of cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase[59,60] |

| 3.4 Polyphenols dampen the activity of the inflammasome NLRP3, with downregulation of caspase1, IL-1 beta, and IL18[63,64,65,66] |

| 3.5 Reduction of NLRP3 is associated with improvement of clinical markers, as seen in aged male subject at high cardiovascular risk following acute administration of red wine[64,68] |

| 4.1 In cholesterol-fed rabbits and in hamsters administration of red wine polyphenols decreases neo-intimal growth, lipid accumulation, and entry of monocytes in the iliac arteries[80,81] |

| 4.2 In patients with coronary artery disease, supplementation of purple grape juice reduces levels of oxidized lipoproteins through generation of nitric oxide[82,83,84] |

| 5.1 Flavan-3-Ols |

| 5.1a-Flavan-3-ols metabolites, hydroxy-phenyl-gamma-valerolactones, hydroxy-phenyl valeric acid, and protocatechuic acid exhibit hypotensive activity in rats and decrease diabetic cardiomyopathy, with reduction of inflammatory biomarkers[93,94,95] |

| 5.1b- Cocoa flavan-3-ols supplementation reduces trimethylamine-N oxide in healthy individuals, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in hypertensive individuals, and in patients with coronary artery disease, while increasing flood-mediated dilation (FMD)[98,99,101] |

| 5.1c- Administration of green tea catechins to healthy volunteers decreased SBP, and DBP, and improvedpostprandial glucose status, while lowering serum thioredoxin levels[102,103,104] |

| 5.1d- No effects of green tea catechin supplementation were observed in healthy male volunteers, activeolder people, and overweight women[105,106,107] |

| 5.2 Resveratrol (RES) |

| 5.2a- In rodents, RES mitigates cardiac, endothelial hypertrophy, and cardiac fibrosis, dampening MAPK activity and transforming-growth factor-beta/Smad 2/3 signaling pathway[119,120,121] |

| 5.2b- RES inhibits endothelin-1, with production of nitric oxide, and prevention of atherosclerosis [123] |

| 5.2c- In diabetic mice, RES attenuated high-glucose oxidative stress, and cardiomyocyte apoptosis through enhancement of Nrf-1, and Nrf-2 transcription factors[124] |

| 5.2d- In patients with hypertension, RES administration reduced hypertension[125,126], while in other two studies such an effect was not confirmed[117,127,142] |

| 5.2e- In hypertensive patients, stable coronary artery disease patients, and patients with metabolic syndrome, long term RES administration improved the FMD of the brachial artery[128,129,130,131] |

| 5.2f- RES administration can modify the lipid profile, diabetes, and inflammation in patients with atherosclerosis[132,133,134] |

| 5.2g- In patients with heart failure, RES administration improved both systolic and diastolic function,reducing the serum levels of the N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide[117,129,135] |

| 5.3 Curcumin |

| 5.3a- In hypertensive rat models, curcumin administration normalized vascular function, attenuating coronary artery damage[139,140,141,142] |

| 5.3b- In hypertensive patients, refractory or relapsing lupus nephritis patients and obese subjects curcumin reduced blood pressure, with an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines[143,144,145] |

| 5.3c- In another study, curcumin did not modify blood pressure in healthy middle-aged and older adults[146] |

| 5.4 Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) |

| 5.4a- Hydroxytyrosol (HT) inhibited platelet aggregation in rats, decreasing thromboxane B2, and prostacyclin, while increasing nitric oxide [151,152] |

| 5.4b- In hypercholesterolemic individuals, HT administration normalized the lipid profile, with reduction of SBP, and DBP study, HT [153,154,155]. In another administration did not modify lipid profile and cardiovascular biomarkers[157] |

| 5.4c- In patients with stroke, administration of HT 24 h after stroke decreased glycated hemoglobin and DPB[158] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).